ABSTRACT

Objectives

Our aim was to better understand and raise awareness of the diagnosis journey and quantify any barriers for timely diagnosis of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), to support patients’ struggle with diagnosis and reduce time to diagnosis.

Methods

Patients diagnosed with, or caregivers for those diagnosed with primary or secondary HLH and physicians involved in the treatment of HLH were recruited. Quantitative interviews were undertaken with patients/caregivers to quantify key elements of the diagnosis journey, followed by qualitative interviews with participants. Interviews took place between March–May 2021.

Results

Thirty-three patients/caregivers and nine physicians took part in this mixed methods study. Lack of physician awareness of HLH was a common frustration for patients/caregivers, causing delayed diagnosis. All physicians indicated bone-marrow testing is a key step in the diagnosis process, and some patients/caregivers had frustrations around testing. Emergency care doctors, although not usually involved in the diagnosis process, were among the most-seen specialists by patients/caregivers. Patients/caregivers suggested potential improvements in available information, such as providing information on treatment options and condition management.

Discussion

Patients/caregivers and physicians agreed on the need to raise overall awareness of HLH signs/symptoms among priority groups of physicians to recognise how signs/symptoms can progress and develop. Improvements in the testing process and communication would directly impact the speed of diagnosis and support patients/caregivers during the diagnostic journey, respectively.

Conclusion

Raising awareness of key issues, such as signs/symptoms, tests and diagnostic procedures, and improved communication and support for patients/caregivers, are key to speeding up HLH diagnosis and improving outcomes.

1. Introduction

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare and life-threatening hyperinflammatory syndrome, which results in elevated cytokines, thus also marking HLH as a cytokine storm syndrome [Citation1–3]. It can be categorised into primary HLH (pHLH) or secondary HLH (sHLH), where pHLH is an inherited or genetic form of the disease, and sHLH is triggered by an underlying condition [Citation1,Citation4], including: viral, fungal or bacterial infections; malignant or non-malignant disorders; metabolic disorders; and rheumatologic diseases such as systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA) and adult-onset Still’s disease (called rheumatic HLH or macrophage activation syndrome [MAS]); or induced by some treatments [Citation4–8].

Conventional therapy for treatment of HLH is the HLH-94 and HLH-2004 protocols [Citation9,Citation10]; sHLH treatment can be affected by treatment of the identified underlying condition [Citation11]. Diagnosis of HLH is based on the HLH-2004 criteria (Supplementary Table 1), which state that HLH can be established by a molecular diagnosis or if five of eight specific diagnostic criteria are met [Citation9,Citation12,Citation13]. Genetic testing is useful to confirm a clinical diagnosis [Citation2], with the diagnosis being supported by a positive family history of the disease [Citation14]. As well as HLH-2004, alternative diagnosis criteria are available including the HScore [Citation15] and the European League Against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology approved criteria for MAS [Citation16].

The non-specific nature of symptoms presented by HLH can delay diagnosis and lead to misdiagnosis [Citation4,Citation12]. There is a need to better understand the HLH patient journey to diagnosis and raise awareness of HLH among non-specialists, to help support patients and reduce the time to diagnosis. The aim of this mixed methods study was to describe both the patient’s and caregiver’s journeys using quantitative and qualitative interviews, and explore and build awareness of the key barriers in the diagnosis journey from the perspective of patients with HLH/caregivers of patients with HLH and physicians involved in treating patients with HLH, to overcome the challenges currently faced in achieving a timely diagnosis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Objectives

The objectives of this mixed methods study were to explore and identify factors important in reaching a timely diagnosis of HLH and to build awareness of the HLH diagnosis journey with the aim to reduce the overall time to diagnosis.

2.2. Study population

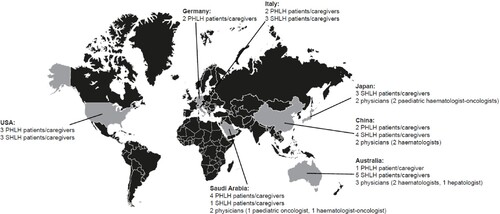

Physicians from Australia, China, Japan and Saudi Arabia were recruited to participate in the study. Physicians from Japan and Saudi Arabia were recruited based on their extensive history of working with HLH. All physicians were recruited as per the following eligibility criteria: eligible physicians had to have personally consulted with and/or treated at least one HLH patient in the past 12 months; have full responsibility for any treatment decisions for HLH patients; and spend at least 70% of their time in direct patient care.

Patients and caregivers were recruited from Australia, China, Japan, Saudi Arabia, Germany, Italy and the U.S.A. Patient associations were involved in the recruitment of patients/caregivers in Australia, the U.S.A., Italy and Germany. In Germany a subsequently recruited patient/caregiver assisted in the recruitment of another patient/caregiver. Patients/caregivers from China, Japan and Saudi Arabia were recruited via physicians. Eligible patients/caregivers of patients with HLH, formally diagnosed with HLH in the past 3 years, required a good recall of their diagnosis journey (recall of tests relied on awareness of test names). Patients were all over 16 years old. Caregivers had to be currently/previously caring for a patient.

2.3. Interviews

Interviews were undertaken using quantitative and qualitative methodology. Insights from the initial quantitative survey results were used during the qualitative discussions with the patients/caregivers, using a sequential explanatory mixed methods approach [Citation17].

Quantitative, 15-minute, pre-interviews were undertaken with patients/caregivers to quantify key elements of the diagnosis journey using computer-assisted web interviewing and covered questions including: ‘What were the very first symptoms that caused you to seek medical help?’; ‘About the time of the first symptoms, what types of tests did you undergo?’; and ‘What, if anything, caused a delay in receiving the correct diagnosis?’ (Supplementary methods 1).

Individual qualitative interviews using video or telephone with screen sharing with participants lasted 60 minutes and the results were content analysed. The data analysed were the responses to the questions. Data were analysed in depth, by question, by two co-authors working together, and key themes were identified. The questions covered in the qualitative interviews included: the types of symptoms and testing performed; the number of misdiagnoses; and journey to the final diagnosis including any challenges (Supplementary methods 2).

The interviews of physicians were conducted from 2–18 March 2021, and those of patients/caregivers from 22 March–26 May 2021.

3. Results

3.1. Sample

Nine physicians from Australia, China, Japan and Saudi Arabia participated in the study. There was a total of 33 patients/caregivers; 14 had experience of pHLH and 19 had experience of sHLH (; Supplementary Table 2).

3.2. Signs/symptoms

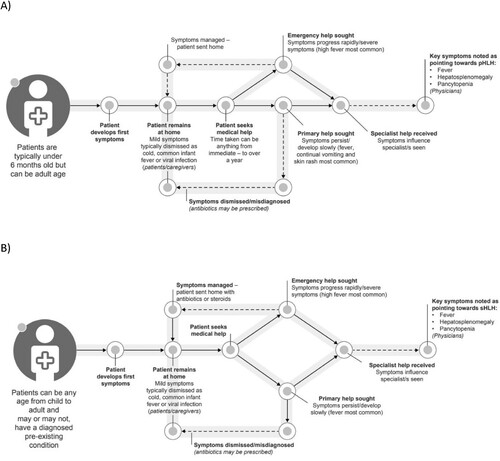

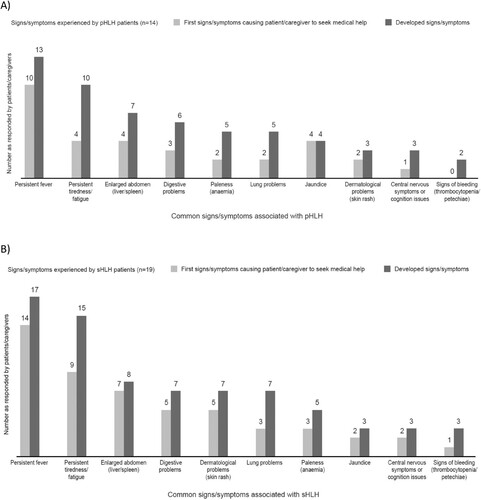

The sign/symptom journey experienced by patients with pHLH and sHLH is outlined in (A and B), respectively. The age of pHLH patients (n = 14; including those looked after by the caregivers participating in the study) at first symptom was ≤6 months (n = 7), 7 months–1 year (n = 1), 1–5 years (n = 1), 6–10 years (n = 1), 11–20 years (n = 3) and ≥21 years (n = 1). For sHLH patients (n = 19; including those looked after by the caregivers participating in the study), age at first symptoms was 1–10 years (n = 1), 11–20 years (n = 4), 21–30 years (n = 5), 31–50 years (n = 3), 51–60 years (n = 4) and ≥61 years (n = 2).

Figure 2. Patient sign/symptom journey for (A) pHLH patients and (B) sHLH patients. pHLH: primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

HLH patients experienced a range of common signs/symptoms; the most reported were persistent fever, persistent tiredness/fatigue and an enlarged abdomen (liver/spleen) (). Other common signs/symptoms and a range of less common signs/symptoms noted are outlined in Supplementary Table 3. Patients/caregivers noted that signs/symptoms for both pHLH and sHLH can be immediate, intermittent, or progressive, whereas physicians were more likely to consider signs/symptoms to be both persistent and progressive.

Figure 3. Signs/symptoms experienced – responses provided by patients/caregivers for (A) pHLH patients and (B) sHLH patients. pHLH: primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

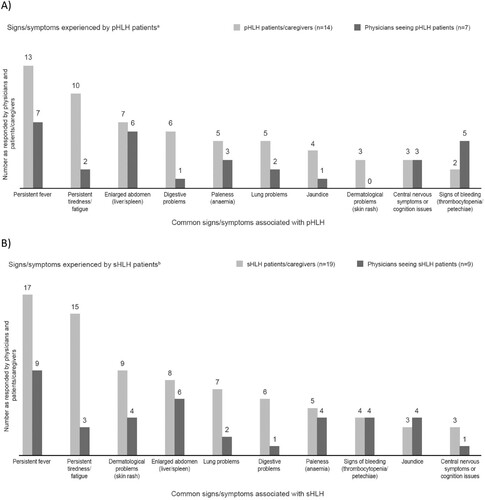

Physicians noted fever and hepatosplenomegaly as key signs/symptoms pointing towards a pHLH diagnosis, and an unexplained fever/fever worsening despite treatment as a key sign/symptom for a sHLH diagnosis. Patients/caregivers and physicians considered close attention to fevers (repeated/persistent) as important in receiving correct/timely diagnosis.

Physicians may not consider persistent tiredness/fatigue, jaundice, digestive problems and lung problems as signs/symptoms of pHLH. Similarly, for sHLH, persistent tiredness/fatigue, lung problems and digestive problems were among the most common signs/symptoms least well known by physicians (). For both pHLH and sHLH patients/caregivers, the lack of awareness of HLH (pHLH, 9/14; sHLH, 10/19), lack of specialist knowledge on the signs/symptoms of HLH (pHLH, 8/14; sHLH, 8/19), and lack of awareness of HLH by doctors (pHLH, 7/14; sHLH, 7/19) were identified as the most common causes of frustration in the diagnosis journey and caused delays in getting a diagnosis. Physicians typically agreed with patients/caregivers that lack of awareness and knowledge of HLH caused delays in getting the patient to the correct specialist(s) to assist with diagnosis. Physicians perceived that awareness of HLH is high among haematologists and lower in other specialities and primary care.

Figure 4. Signs/symptoms experienced – responses provided by patients/caregivers and physicians for (A) pHLH patientsa and (B) sHLH patientsb. aAll physicians note fever as the most common symptom overall. Other mentions x1: hepatosplenomegaly; cytopenia; pancytopenia; and lymphadenopathy. bNearly all physicians note fever as the most common symptom overall. Other mentions include: cytopenia; pancytopenia; lymphadenopathy; joint pain; arthritis; abdominal pain; and low blood cell count. pHLH: primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

To ensure referrals are made to appropriate specialists, both patients/caregivers and physicians agreed it is important to raise the overall awareness of HLH signs/symptoms among general practitioners (GPs), primary care physicians (PCPs), paediatricians and emergency care doctors, as well as raising awareness with any specialist likely to be part of the diagnosis process.

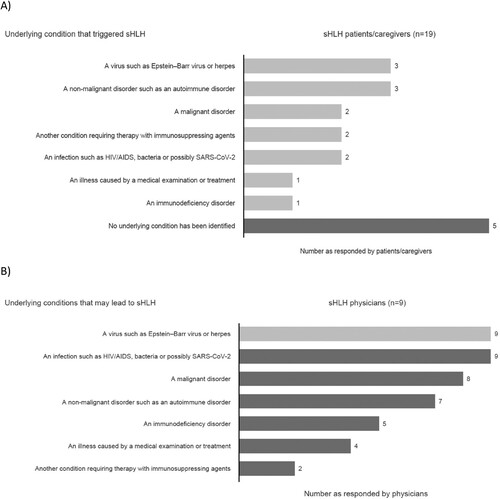

Most sHLH patients/caregivers responded that the associated underlying condition is known, but for some patients the cause is never identified ().

3.3. Diagnosis journey

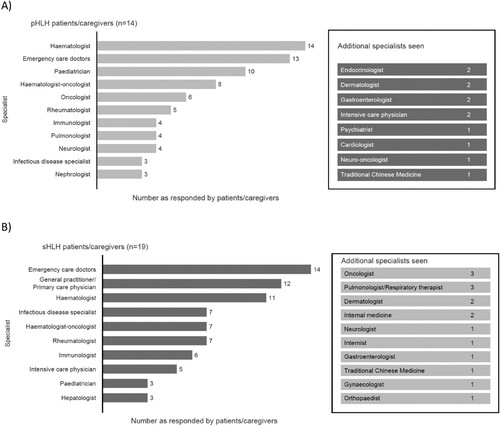

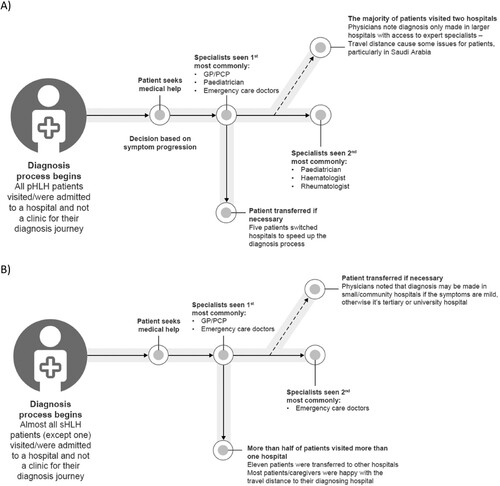

pHLH and sHLH patients/caregivers reported seeing up to eleven and nine different specialties, respectively, including a haematologist, prior to receiving a diagnosis. Specialists seen included emergency care doctors (n = 13/14) and paediatricians (n = 10/14) for pHLH patients, and emergency care doctors (n = 14/19) and a GP/PCP (n = 12/19) for sHLH patients (). The physicians seen first and second by patients with pHLH and sHLH are outlined in (A and B), respectively. Most HLH patients/caregivers reported seeking help from a haematology specialist at the fourth or later visit. Whilst other specialists were seen first before reaching a haematologist, including GPs and emergency care doctors (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 6. Types of specialists seen before a diagnosis was made – responses from patients/caregivers for (A) pHLH patients/caregivers and (B) sHLH patients/caregivers. pHLH: primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Figure 7. Physicians seen on the patient journey for (A) pHLH patients and (B) sHLH patients. GP: general practitioner; PCP: primary care physician; pHLH: primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

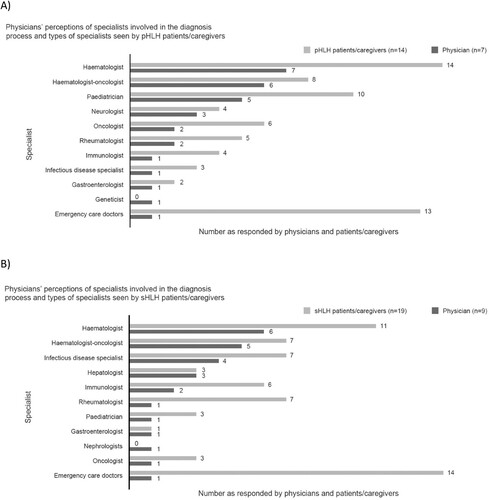

Physicians’ responses regarding the specialists involved in the HLH diagnosis process indicated that haematologists are the most likely to be involved. Haematologist-oncologists and paediatricians are more likely to be involved in the diagnosis of pHLH; and haematologist-oncologists and infectious disease specialists are more likely to be involved in diagnosing sHLH. Whilst not usually involved in the diagnosis process, emergency care doctors were amongst the most-seen specialists by patients/caregivers for both pHLH and sHLH ().

Figure 8. Physicians’ perceptions of specialists involved in the diagnosis process and types of specialists seen by patients/caregivers (A) physicians and pHLH patients/caregivers and (B) physicians and sHLH patients/caregivers. pHLH: primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

pHLH (14) and sHLH patients/caregivers (19) reported haematologists (n = 8) and haematologist-oncologists (n = 6) were the most likely to make a HLH diagnosis. The majority of pHLH patients (86%; 12/14) were diagnosed by a team of physicians rather than one physician alone, compared with 42% (8/19) of sHLH patients.

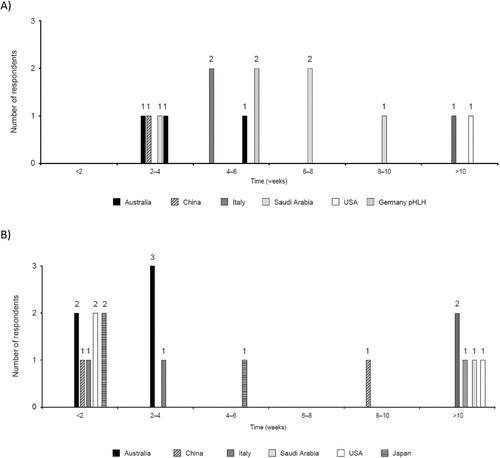

Following first signs/symptoms, most patients/caregivers noted time to diagnosis for pHLH ranging from 4–6 weeks and <2 weeks for sHLH, but diagnosis could also take longer (). Physicians reported time to diagnosis ranging from 2–3 days to up to 3 months for pHLH and ≤1 to 3 weeks for sHLH. A total of 57% and 63% of patients were misdiagnosed before receiving the correct diagnosis for pHLH and sHLH, respectively (further details of misdiagnosis are in the Supplementary results).

Quote: “Difficulty is if the patient visits other specialists, who may treat it as refractory infection or severe infection, so the treatment will be delayed” Haematologist, China.

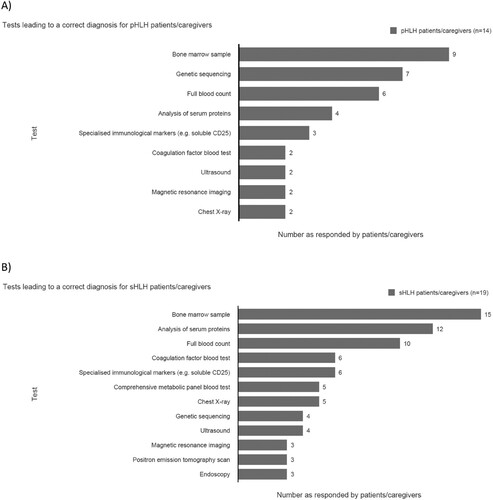

3.4. Testing

Patients/caregivers perceived a bone marrow sample, analysis of serum proteins (especially ferritin) and full blood count (FBC) as the key diagnostic tests for sHLH, with both a bone marrow test, genetic sequencing and FBC most often leading to the correct diagnosis for pHLH (). In some cases (n = 6/14) patients/caregivers with experience of pHLH noted combinations of tests were required to achieve final diagnosis, all sHLH patients/caregivers agreed this was the case.

Figure 10. Tests leading to a correct diagnosisa for: (A) pHLH patients/caregiversb and (B) sHLH patients/caregivers.c. aNote for patients/caregivers – recall of tests relies on awareness of test names (promoted by a list during the interview) and therefore not all tests may be recognised, especially where communication from physicians is noted to be lacking. bAdditional tests leading to correct diagnosis (one mention): comprehensive metabolic panel blood test (Italy); positron emission tomography scan (Australia); triglycerides (Australia); NK cell activity test (China); lymph node (biopsy; Saudi Arabia). cAdditional tests mentioned by two or less patients/caregivers: NK cell activity test (U.S.A. one; Australia one); computerized tomography scan (U.S.A.); lumbar puncture (Australia). NK, natural killer; pHLH, primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH, secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

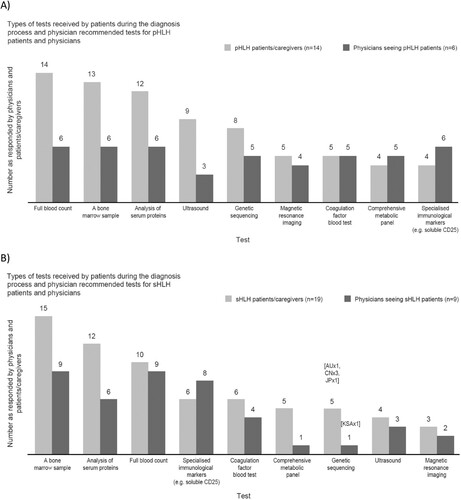

Physicians agreed a bone marrow sample is key to diagnosing sHLH (n = 9/9) and pHLH (n = 6/6); supported by a FBC, serum proteins analysis (such as ferritin, lipid profile, hepatic and renal function, and coagulation function) and immunological markers [CD25] for sHLH. For pHLH, genetic tests were also noted to be key tests for diagnosis. Genetic tests are less commonly undertaken than bone marrow sample tests by physicians for pHLH diagnosis. For sHLH, five patients noted undergoing a genetic test and one physician recommended a genetic test ().

Quote: “There are two parts of testing. Part 1 is to test for blood routine, hepatic and renal function, coagulation factor, complete blood cell count, for the diagnosis of haemophagocytic syndrome. Part 2 is to test for the disease cause systemically, including bone marrow test, CT, PET-CT, immunological markers, immunological function, blood test for patients with infection, and tumour-related tests, as well as the endocrine tests (e.g. hyperthyroid test). All of these tests should be conducted at the same time.” Haematologist, China (sHLH physician).

Quote: “I went to the GP and he recommended a blood test and also checked ferritin levels and some infection markers and other things. After looking at the results, my GP said, your ferritin levels are more than 400, so you definitely need to go to the emergency department.” pHLH patient, Australia.

Figure 11. Types of tests received by patients during the diagnosis process and physician recommended tests – responses from patients/caregivers and physicians for (A) pHLH patients and (B) sHLH patients. AU: Australia; CN: China; JP: Japan; KSA: Saudi Arabia; pHLH: primary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

There was frustration among a small number of HLH patients/caregivers at not being able to have certain tests, the time it took to do the tests and the number of tests that needed to be repeated. Patients/caregivers and physicians noted there was no defined order for carrying out tests to diagnose HLH, with pHLH physicians indicating that all relevant tests build a diagnosis. However, there may be some commonalities as to when tests are performed. Responses from patients/caregivers and physicians noted FBC and analysis of serum proteins are typically performed first and repeated throughout the diagnosis journey, with imaging and immunological markers performed before or after bone marrow biopsy depending on patient symptoms. A bone marrow biopsy is performed early on in the journey, and there is an indication this may help speed up the diagnosis process. For pHLH, genetic sequencing is important to confirm a diagnosis, however, performance of this test may be affected by issues of availability in certain hospitals, relevance to pHLH only, cost and time to results.

Quote: “ … If there was more awareness that if someone has a fever and there is no apparent cause and there are sepsis symptoms it could be HLH.” sHLH patient – Australia.

Quote: “There is no one test that is a marker for HLH, it is a combination of tests. That’s the frustrating part, there is no one single test that you can do.” Haematologist, Australia (pHLH physician).

Both groups of HLH patients/caregivers and physicians noted improvements are required in the testing and diagnosis process, with suggestions to avoid invasive testing (bone marrow sample test). There is also a need to provide education to ensure ferritin levels are checked multiple times if needed, and that testing should continue if not all five diagnostic criteria are met first time.

3.5. Communication and support

HLH patients/caregivers were generally satisfied with the information they received; however, improvements were suggested. Information concerning the disease, treatment options, condition management and, for pHLH only, the risks to other family members could be provided. At the time of diagnosis, some patients/caregivers were able to find support through other means. Patients/caregivers and physicians agreed patient associations can provide valuable support. Approximately half of pHLH (43%, n = 6) and a third of sHLH patients/caregivers (32%, n = 6) reported that they searched online for information in response to initial signs/symptoms. Patients/caregivers and most physicians noted ideas for education/training in the signs/symptoms of HLH including: a one-page summary of the condition provided to GPs, sharing of case studies across specialities and rare disease seminars. In-person meetings for physicians were suggested as a method of dissemination.

Quote: “Patient associations are in the best position to provide support as doctors in hospitals are not in a position to offer much needed information and psychological support. However, they are not visible enough.” sHLH caregiver, Italy.

4. Discussion

This mixed methods study explored the HLH diagnosis journey from the perspective of patients diagnosed with or those caring for someone diagnosed with HLH and physicians involved in the treatment of HLH via a quantitative survey and in-depth discussions to better understand the delays in diagnosis and identifying key factors involved in building an awareness of the journey itself.

This study highlights how raising awareness of signs/symptoms among key groups such as emergency care doctors, GPs, paediatricians and specialists, and the need for patient support in HLH are important factors in enhancing the diagnosis process. Both pHLH and sHLH patients/caregivers found the lack of specialist knowledge around HLH frustrating, leading to delays in diagnosis. A similar conclusion has been made by patients and caregivers with experience of pHLH in a previous publication, with delays in diagnosis and referral caused by a lack of awareness of pHLH by healthcare professionals [Citation18]. Although raising the general awareness of HLH is important, targeting the right audience is key to a timely referral and diagnosis. As shown in this study, delays in diagnosis can be lengthy, resulting in the patient having to wait months for the appropriate treatment and support for a life-threatening condition.

During the diagnosis process, patients/caregivers noted emergency care doctors were one of the specialists seen most often as the first point of contact. This is expected given the signs/symptoms patients can present with. Haematologists and haematologist-oncologists were noted as those who made the diagnosis of HLH most often. Physicians agreed that awareness is higher amongst haematologists. GPs/PCPs and emergency care doctors were identified by patients/caregivers and physicians as a priority target to increase awareness of HLH. The potential role of emergency clinicians to accelerate testing, referrals and treatment in the HLH diagnosis process has been highlighted in a recent study [Citation19]. Although this group is a priority, an increased awareness of HLH in other specialities and the general public would also be beneficial, with the ultimate goal to reduce time to referral and diagnosis.

The key issue of HLH sign/symptom recognition was raised by the survey respondents. HLH presents with non-specific symptoms that can delay diagnosis [Citation4]. Our study found that GPs/PCPs, paediatricians and emergency care doctors lacked awareness of the range of possible signs/symptoms HLH can present. However, given the rarity of the disease [Citation2], when presented with non-specific signs/symptoms physicians may be more likely to diagnose the most probable cause based on previous experience and probability. To assist in the recognition of HLH, a checklist of the most common signs/symptoms could be used, along with any family history details in the case of suspected pHLH. Morrisette, et al., generated a proposed workflow guide to assist emergency care workers to detect possible presentations of HLH, in combination with other tools [Citation19]. However, a specified list of symptoms may hinder diagnosis of HLH if these criteria are not met [Citation20], and the list may not be sufficient to conclusively reach a diagnosis.

This study also indicated it is key to recognise that the range of possible HLH signs/symptoms can develop at different times, thus identifying these symptom patterns could assist with diagnosing HLH. The North American Consortium of Histiocytosis have recommended that in addition to identifying patterns of HLH, those diseases that mimic HLH also need to be excluded [Citation12]. Raising awareness of HLH signs/symptoms in the public and also among primary care providers and specialists may trigger both those affected to seek help earlier and raise the suspicion of HLH with physicians. Moreover, educating primary care providers on non-invasive tests (such as blood analysis and imaging) may encourage them to explore a diagnosis of HLH when presented with excessive or pathological immune activation, characterised by fever and extreme hyperferritinaemia. This would expediate referral to specialist care.

Regarding sHLH, the results highlighted that for some patients the underlying associated condition goes undiagnosed. A study analysing a registry of adult HLH patients found that for 10.9% of patients the underlying condition was not identified [Citation21]. sHLH may occur as a result of an underlying condition or triggered by an infection, and thus the therapeutic strategy is likely aimed at treating the underlying condition; therefore, a conclusive diagnosis of sHLH could be misleading. Identifying the underlying condition is seen as a key challenge in treatment. Recommendations indicate that investigations into the underlying condition should continue even if treatment has been initiated [Citation13]. Alternative terminology to pHLH and sHLH utilised in this paper has been proposed, in which patients are grouped whether they have the HLH disease (immune dysregulation as the main problem) or a mimic version (patients who have a disorder which leads to the distinctive clinical pattern of HLH, but are unlikely to benefit from immune suppression) and by their aetiologic association [Citation12]. It has been noted that sHLH as a term may imply that all patients require similar treatment, whilst further classification may be warranted to ensure appropriate treatment is provided [Citation12].

During their diagnosis journey, there was frustration from a small number of patients/caregivers around testing. Reviews on the diagnostic aspects of MAS, considered as sHLH and particularly linked to sJIA, noted several diagnostic challenges as a result of implementing the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria. A delay in diagnosis is likely to impact the early use of targeted therapy, which is critical to manage the condition [Citation22,Citation23]. A set of criteria (three major and two minor, validated in a retrospective study) based on the HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria have been combined into a minimal set of parameters to aid the timely diagnosis of HLH [Citation24]. A study reporting the impact of a quality improvement programme, which included targeted education, and updating the test catalogue to remove mistaken tests, resulted in reduced errors and delays in testing for patients assessed for HLH, where errors in testing had previously impacted patients [Citation25]. Physicians in this study stated that a bone marrow biopsy was a key test in the diagnosis of sHLH and to confirm pHLH. Previous research has indicated that a diagnosis of HLH can be made (≥5 HLH-2004 diagnostic criteria met) without confirmation via bone marrow biopsy; however, it can be useful in diagnosing HLH when less than five criteria are met [Citation26]. The results of a bone marrow biopsy should be considered in the context of other clinical criteria [Citation26,Citation27]; haemophagocytosis in bone marrow alone shows a lack of specificity for a diagnosis of HLH [Citation27]. It should also be noted that bone marrow biopsies taken early in the course of sHLH can be non-specific [Citation4], and haemophagocytosis may not be present during initial bone marrow examination [Citation2,Citation28], or in all those diagnosed with HLH [Citation21]. A negative bone marrow biopsy does not always preclude diagnosis [Citation2]. The biopsy procedure can be painful and unpleasant [Citation29], with both general and local anaesthesia used in paediatric cases [Citation30]. However, as noted in this study, a bone marrow biopsy may speed up the diagnosis process.

This mixed methods study’s survey results indicate that communication and support are in short supply, with clear and simple explanations hard to come by. Patients/caregivers would benefit from additional insight into HLH including causes, condition management, the tests required and treatment available. A survey of patients and caregivers with experience of pHLH reported that the availability of information about pHLH was lacking during their diagnosis journey, however, some support was provided by patient advocacy forums [Citation18]. Similarly in this study, patients/caregivers and physicians agreed that patient associations can be a great help. However, considering the rare and acute nature of the condition, patient support may be challenging when compared with a chronic and prevalent condition.

A limitation of our study is the small number of patients/caregivers and physicians involved. As HLH is a rare disease, a sample of this size may be representative of the patient/caregiver and physician community in the countries presented. However, selection bias cannot be ruled out and is potentially a limitation of the study, as some patients/caregivers who took part in the survey were identified via patient associations and thus may represent patient/caregiver groups more likely to be involved in such activities. In addition, the transferability of our findings, including the opinion of physicians, to the global HLH clinical community is unclear due to the lack of European and US physicians. A further limitation is that the physicians seen by sHLH patients during their diagnosis journey may not be representative of all physicians who may be seen in relation to sHLH; in our study the underlying condition was not identified in five patients.

5. Conclusions

Analysis of the diagnosis journey from a patients’/caregivers’ and physicians’ perspective has shown that raising awareness of key issues such as signs/symptoms, tests and diagnostic procedures, and available support in HLH are key to speeding up the diagnostic process and improving outcomes. GPs/PCPs, paediatricians and emergency care doctors are noted priority target groups to increase awareness of HLH, with many patients meeting these physicians early on in the diagnosis process; diagnosis can involve a team of physicians. Recognising that a range of different signs/symptoms can develop immediately, intermittently or progressively is important. Testing is a key area of frustration for patients and caregivers and one where improvements would have a direct impact on the speed of diagnosis. Finally, improved communication and support could help patients and caregivers at all stages of the diagnosis journey.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research was carried out by Phoenix Marketing International, a market research company, in accordance with applicable market research codes of conduct and/or guidelines, including the European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association, and current national and international codes of practice and guidelines. Informed consent was obtained from all participants and all data obtained were anonymised. As the study was market research, no ethics approval was required in the countries where the research was performed.

HLH diagnosis manuscript_updated_suppl_21 March_clean_anon.docx

Download MS Word (373.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient associations AILE Onlus (IT), Histiozytose Hilfe (DE) and Histiocytosis Association (US) who assisted in finding respondents, the qualitative research partners: PRO research, Tribe research, Insights & Outlooks, Advanced Healthcare research, Joytec research, Healthcare Insights, and Just Worldwide (JWW), and the quantitative partner, Research Results. The authors would also like to thank Professor Ashish Kumar (Director, The Cincinnati Children's Histiocytosis Center) for his valuable insights and guidance. Medical writing support was provided by Hayley Owen, PhD (Bioscript, Macclesfield, UK) and funded by Sobi.

Disclosure statement

Tracy Machado and Judith Lawrence were contracted to conduct the research on behalf of Sobi. Daniel Eriksson and Jason Donohue are employees of Sobi and shareholders of Sobi stock.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. The data sharing policy of Sobi is available at the following site: https://www.sobi.com/en/policies. As noted on that site, requests for access to the study data can be submitted to [email protected].

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tracy Machado

Tracy Machado has researched interests in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and qualitative research. E-mail: [email protected]

Judith Lawrence

Judith Lawrence has researched interests in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and qualitative research. E-mail: [email protected]

Daniel Eriksson

Daniel Eriksson has researched interests in haematology and qualitative research. E-mail: [email protected]

Jason Donohue

Jason Donohue has researched interests in patient-centred care and qualitative research. E-mail: [email protected]

References

- Allen CE, McClain KL. Pathophysiology and epidemiology of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:177–182. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.177

- Jordan MB, Allen CE, Weitzman S, et al. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2011 Oct 13;118(15):4041–4052. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-03-278127

- Soy M, Atagunduz P, Atagunduz I, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a review inspired by the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatol Int. 2021 Jan;41(1):7–18. doi:10.1007/s00296-020-04636-y

- George MR. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: review of etiologies and management. J Blood Med. 2014;5:69–86. doi:10.2147/JBM.S46255

- Jumic S, Nand S. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: associated diagnoses and outcomes, a ten-year experience at a single institution. J Hematol. 2019 Dec;8(4):149–154. doi:10.14740/jh592

- Kalmuk J, Puchalla J, Feng G, et al. Pembrolizumab-induced Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis: an immunotherapeutic challenge. Cancers Head Neck. 2020;5:3. doi:10.1186/s41199-020-0050-3

- Grom AA, Horne A, De Benedetti F. Macrophage activation syndrome in the era of biologic therapy. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016 May;12(5):259–268. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2015.179

- Crayne CB, Albeituni S, Nichols KE, et al. The immunology of macrophage activation syndrome. Front Immunol. 2019;10:119. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00119

- Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007 Feb;48(2):124–131. doi:10.1002/pbc.21039

- Henter JI, Samuelsson-Horne A, Arico M, et al. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with HLH-94 immunochemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2002 Oct 1;100(7):2367–2373. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-01-0172

- Ehl S, Astigarraga I, von Bahr Greenwood T, et al. Recommendations for the use of Etoposide-based therapy and bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of HLH: consensus statements by the HLH steering committee of the histiocyte society. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2018 Sep - Oct;6(5):1508–1517. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2018.05.031

- Jordan MB, Allen CE, Greenberg J, et al. Challenges in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Recommendations from the North American Consortium for Histiocytosis (NACHO). Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2019 Nov;66(11):e27929. doi:10.1002/pbc.27929

- La Rosée P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood. 2019 Jun 6;133(23):2465–2477. doi:10.1182/blood.2018894618

- Bergsten E, Horne A, Arico M, et al. Confirmed efficacy of etoposide and dexamethasone in HLH treatment: long-term results of the cooperative HLH-2004 study. Blood. 2017 Dec 21;130(25):2728–2738. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-06-788349

- Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Sep;66(9):2613–2620. doi:10.1002/art.38690

- Ravelli A, Minoia F, Davi S, et al. Classification criteria for macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: a European League against Rheumatism/American College of Rheumatology/Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation Collaborative Initiative. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016 Mar;68(3):566–576. doi:10.1002/art.39332

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark VL, et al. Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. National Institutes of Health, 2011.

- Nixon A, Roddick E, Moore K, et al. A qualitative investigation into the impact of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis on children and their caregivers. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021 May 6;16(1):205. doi:10.1186/s13023-021-01832-2

- Morrissette K, Bridwell R, Lentz S, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the emergency department: recognizing and evaluating a hidden threat. J Emerg Med. 2021 Jun;60(6):743–751. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2021.02.006

- Ely JW, Graber ML, Croskerry P. Checklists to reduce diagnostic errors. Acad Med. 2011 Mar;86(3):307–313. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820824cd

- Birndt S, Schenk T, Heinevetter B, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: collaborative analysis of 137 cases of a nationwide German registry. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2020 Apr;146(4):1065–1077. doi:10.1007/s00432-020-03139-4

- Boom V, Anton J, Lahdenne P, et al. Evidence-based diagnosis and treatment of macrophage activation syndrome in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2015;13(1):55. doi:10.1186/s12969-015-0055-3

- Abdirakhmanova ASV, Mukusheva Z, Assylbekova M, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review of the diagnostic aspects. Front Med. 2021;8:681875. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.681875

- Smits BM, van Montfrans J, Merrill SA, et al. A minimal parameter set facilitating early decision-making in the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Clin Immunol. 2021 Aug;41(6):1219–1228. doi:10.1007/s10875-021-01005-7

- Merrill SA, Naik R, Streiff MB, et al. A prospective quality improvement initiative in adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis to improve testing and a framework to facilitate trigger identification and mitigate hemorrhage from retrospective analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Aug;97(31):e11579. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011579

- Gars E, Purington N, Scott G, et al. Bone marrow histomorphological criteria can accurately diagnose hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica. 2018 Oct;103(10):1635–1641. doi:10.3324/haematol.2017.186627

- Ho C, Yao X, Tian L, et al. Marrow assessment for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis demonstrates poor correlation with disease probability. Am J Clin Pathol. 2014 Jan;141(1):62–71. doi:10.1309/AJCPMD5TJEFOOVBW

- Schram AM, Berliner N. How I treat hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the adult patient. Blood. 2015 May 7;125(19):2908–2914. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-01-551622

- Vanhelleputte P, Nijs K, Delforge M, et al. Pain during bone marrow aspiration: prevalence and prevention. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003 Sep;26(3):860–866. doi:10.1016/S0885-3924(03)00312-9

- Zarnegar-Lumley S, Lange KR, Mathias MD, et al. Local anesthesia with general anesthesia for pediatric bone marrow procedures. Pediatrics. 2019;144(2):e20183829. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3829