ABSTRACT

Background/purpose

The treatment landscape of relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (RRMM) is rapidly evolving in Taiwan. The present study aimed to assess the treatment patterns among RRMM patients in Taiwan.

Methods

This retrospective, chart review-based, non-interventional study collected data on RRMM patients (≥20 years old) receiving pomalidomide-based treatment between January 2017 and December 2020 across five sites in Taiwan.

Results

Median age of the study population was 65.6 years. Approximately 75% patients received a doublet regimen and 25% were on a triplet regimen. Disease progression was the most common cause for switching to pomalidomide-based treatments in doublet (71.2%) and triplet (58.3%) groups. Patients in doublet and triplet groups (>80%) received 4 mg pomalidomide as a starting dose. Overall response rate (ORR: 31.5% and 45.8%) and median progression-free survival (PFS: 4.7 and 6.8 months) were reported in the doublet and triplet regimen. Doublet regimen was discontinued mainly due to disease progression or death (78.1%); however, triplet regimen patients mainly terminated their treatment due to reimbursement limitations (29.2%). Healthcare resource utilization (HRU) was comparable between doublet and triplet groups.

Conclusion

In Taiwan, half of RRMM patients received pomalidomide-based triplet regimens. Triplet regimens showed a trend towards better outcomes with longer PFS and higher response rates compared to doublets. Notably, the duration of triplet use is influenced by reimbursement limitations. This study provides insight into RRMM treatment patterns in Taiwan and the findings suggest that triplet regimens may be a better alternative than doublet regimens.

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is an incurable clonal plasma cell neoplasm with substantial morbidity and mortality [Citation1,Citation2]. It is the second most prevalent hematologic malignancy [Citation3,Citation4] with estimated new cases of 176,404 across the globe in 2020, and an age-standardized incidence rate of 1.8 per 100,000 population [Citation5]. While the incidence of MM is on the rise worldwide, the most significant growth rate was observed in East Asia (China, North Korea, and Taiwan) from 1990 to 2016, with a 262% surge [Citation1]. Epidemiological studies on MM in Taiwan reported an increase in the age-adjusted incidence by 13% from 2007 to 2012, followed by a 60% increase in prevalent MM cases between 2007 and 2015 [Citation2,Citation6].

National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) is the single payer responsible for drug reimbursement eligibility and policy formulation in Taiwan [Citation7]. The NHIA set upper limit restrictions on the number of cycles for different regimens [Citation8]. Treatment landscape of MM in Taiwan has evolved recently with the increased use of bortezomib and lenalidomide-based regimens for the first-line (1L) treatment; however, the relapse rate remains high [Citation9]. Notably, bortezomib-based treatments are reimbursed for a maximum of 16 cycles (∼2 years), while lenalidomide-based regimens is reimbursed up to 24 cycles (∼2 years) [Citation8]. Clinical benefit from the reimbursement of novel agents like thalidomide, bortezomib, and lenalidomide for the 1L treatment of MM in Taiwan coincided with the decrease in overall case fatality of relapsed/refractory MM (RRMM) between 2007 and 2015 (from 25.5% to 18.3%) [Citation2,Citation9]. Moreover, autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (auto-HSCT) is reimbursed in Taiwan for eligible MM patients [Citation9]. For MM patients who relapse or are refractory to bortezomib or lenalidomide-based induction therapies, daratumumab-based regimen (daratumumab + lenalidomide/bortezomib + dexamethasone [DRd, DVd]) is approved as the second-line (2L) treatment option in Taiwan. Additionally, ixazomib + lenalidomide + dexamethasone (NRd) is covered as 2L for high-risk patients with specific genetic abnormalities such as patients with del (17p), t (4; 14), t (14; 16), 1q21 amplification [Citation7]. NHIA imposes upper limit restrictions, reimbursing up to 22 injections (∼1 year) for DRd, DVd and 12 cycles (∼1 year) for NRd [Citation8]. However, treatment options become limited upon inadequate response or further relapses following 2L treatment [Citation10].

Pomalidomide and dexamethasone therapy has been emerged as an effective treatment option for patients with RRMM who had received at least two previous treatments, including bortezomib and lenalidomide, especially those resistant to lenalidomide [Citation10,Citation11]. Taiwan NHIA covers carfilzomib + dexamethasone (Kd) and pomalidomide + dexamethasone (Pd) regimens as third-line (3L) therapy for MM. However, there are restrictions: Kd is reimbursed for a maximum of 10 cycles, and Pd for up to 6 cycles [Citation8]. Daratumumab and isatuxumab are the two recently approved CD38-targeted monoclonal antibodies for treating RRMM [Citation12]. A recent real-world study from Taiwan reported good efficacy with the newly introduced combination of daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone in RRMM patients [Citation13]. Combination of isatuximab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone also reported progression-free survival (PFS) benefit over pomalidomide and dexamethasone in RRMM patients [Citation14,Citation15]. Isatuximab has also been announced eligible for reimbursement in Taiwan under the latest NHIA regulations.

Isatuximab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone, has gained recommendation as 3L or beyond for RRMM patients in Taiwan. The approval by Taiwan Food and Drug Administration (TFDA) was based on results from a multinational clinical study comparing this combination to pomalidomide and dexamethasone alone (ICARIA-MM) [Citation16,Citation17]. Owing to the rapidly changing treatment landscape of RRMM in Taiwan, understanding real-world treatment patterns becomes crucial for supporting, improving, and potentially accelerating the delivery of safe and cost-effective therapeutic interventions [Citation18,Citation19]. The present study aimed to understand the treatment patterns among RRMM patients in Taiwan.

Methods

Study design and data source

This retrospective, non-interventional, chart review-based, observational study collected the data on characteristics and treatment profiles of RRMM patients across five sites in Taiwan located in northern, central, and southern areas (Chang Gung Memorial Hospital-Kaohsiung [CGMHKH], China Medical University Hospital [CMUH], National Cheng Kung University Hospital [NCKUH], National Taiwan University Hospital [NTUH], Taichung Veterans General Hospital [TCVGH]). These hospitals are major healthcare centers where MM patients predominantly receive treatment in Taiwan. This diverse geographic distribution ensures representation of MM patients from varied backgrounds, enhancing the generalizability of our findings to the broader population in Taiwan. The entire study period started from new diagnosis (or 01 January 2001) to 30 April 2021 and the data was collected during routine visits from the electronic case report form (eCRF). Investigators or study coordinators completed the eCRF for each enrolled patient. The date of initial prescription with pomalidomide-based treatment is defined as index date. The full observation period started two years prior to the index date to one year after the index date. (Supplementary figure 1)

Study sample

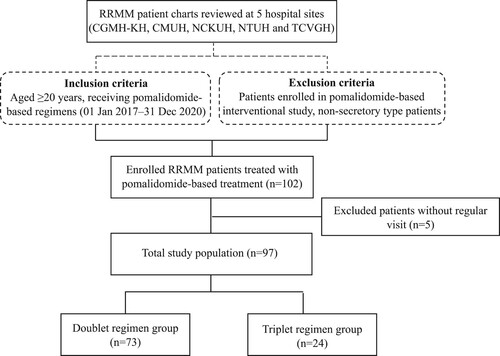

A total of 102 RRMM patients were enrolled in the study, with 10–28 patients per each study site. () Adult patients with RRMM diagnosis aged ≥20 years and receiving pomalidomide-based treatment from 01 January 2017 to 31 December 2020 were included. Patients who had enrolled in any pomalidomide-based interventional study or had non-secretory type myeloma were excluded.

Figure 1. Study design flowchart. Notes: CGMH-KH, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital – Kaohsiung; CMUH, China Medical University Hospital; NCKUH, National Cheng Kung University Hospital; NTUH, National Taiwan University Hospital; RRMM, relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma; TCVGH, Taichung Veterans General Hospital.

Study variables

Study variables included demographic (gender, age at pomalidomide treatment, time to pomalidomide treatment, International Staging System (ISS) at diagnosis, disease subtypes, auto-HSCT status, refractoriness to prior therapies such as bortezomib/lenalidomide, and comorbidities) and clinical (treatment line of pomalidomide, Eastern cooperative oncology group [ECOG] at treatment and reason for switching to pomalidomide-based treatment) characteristics. The treatment pattern and outcome of pomalidomide-based treatment assessed included treatment regimens (doublet/triplet), best response, reasons for discontinuation, duration of treatment, duration of response (DoR), PFS, and factors associated with disease progression following pomalidomide-based treatment. Healthcare resource utilization (HRU) related to pomalidomide-based treatment such as outpatient visits, inpatient hospitalization, length of stay, and emergency department (ED) visits, was also assessed.

Ethical considerations

The present study was conducted according to Taiwan and international standards of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and performed in accordance with ethical principles specified in the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) GCPs, Good Pharmacoepidemiology Practice (GPP) and the applicable legislation on non-interventional studies. This non-interventional study received institutional review board (IRB) approval from all study sites (CGMHKH: 202100749B0; CMUH: CMUH110-REC3-124; NCKUH: B-ER-110-200; NTUH: 202105113RSA; TCVGH: SE21212A). The collection and abstraction of all data were conducted in accordance with both General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), IRB, and institutional policies and procedures.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analysis

Descriptive statistics were reported for demographic characteristics, clinical outcomes, treatment patterns, and HRU. Mean with standard deviation (SD) and median with interquartile range (IQR) were reported for continuous variables, while frequencies and percentages were reported for categorical variables.

Inferential analysis

Independent-sample T-test, Chi-Square test, log rank test or Fisher’s exact test were conducted to compare the baseline demographic characteristics, clinical outcomes, treatment patterns, and HRU between the groups of treatment regimens (doublet vs triplet).

For PFS analysis, a Kaplan-Meier (KM) model was used to deal with loss to follow-up/treatment discontinuation/reimbursement limitation by censoring at the end of follow-up. Estimates for progression (or death) events were presented with the KM curve. Log-rank test was used to compare the median length of PFS between the groups of treatment regimens (double vs triplet).

To assess risk factors of disease progression, cox proportion models were used to determine the factors associated with disease progression. Univariate and multivariate models were controlled for age (>65 vs ≤65), treatment regimen (doublet vs triplet), sex (female vs male), auto-HSCT at new diagnosis (yes vs no), comorbidity (yes vs no), performance status (ECOG 2–3 vs 0-1), prior lenalidomide refractoriness (yes vs no). Hazard ratios (HR) for each covariate and corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) and p-values were reported. All p-values <0.05 on two-tailed testing were considered significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The final patient cohort of the study included 97 RRMM patients, among which 75.2% received the doublet regimen, and 24.7% received the triplet regimen. The median age of the patients was 65.6 years (IQR = 59.1–72.8), and around 51.5% of patients were male. While 49.5% of the patients received auto-HSCT at front-line treatment, 12.4% of the patients received auto-HSCT following relapse as a salvage treatment. Prior to receiving pomalidomide-based treatment, 54.6% of the patients on bortezomib (4.1%), lenalidomide (9.3%), or both (41.2%), experienced refractory disease. Furthermore, 56.7% of patients experienced any comorbidity. Patients receiving doublet (71.2%) and triplet (58.3%) regimen reported disease progression as the most common cause for switching to pomalidomide-based treatments. ()

Table 1. Patient profiles.

Treatment pattern

About 80.0% and 83.3% of patients in doublet and triplet received 4 mg pomalidomide as a starting dose. Patients from doublet and triplet groups had received 5.8 treatment cycles on average. In the triplet regimen, 58.3% received pomalidomide with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone, while 20.8% received carfilzomib with pomalidomide and dexamethasone (Supplemental table 1).

Treatment response

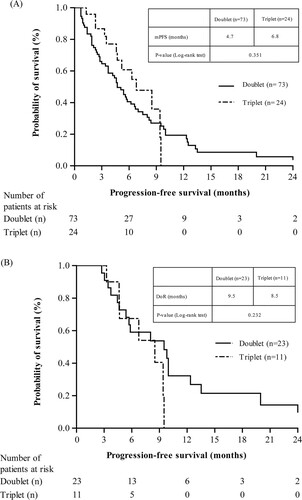

Overall response rate (ORR) was reported in 31.5% and 45.8% of patients in the doublet regimen and triplet regimen, respectively. While complete response (CR) and very good partial response (VGPR) rates were reported in the triplet regimen (4.2% and 8.3%, respectively), only CR rates were reported in doublet regimens (1.4%). In addition, 33.3% of the triplet regimen patients and 30.1% of patients in doublet regimen demonstrated partial response (PR). Moreover, stable disease and progression disease (PD) rates were reported in the doublet (21.9% and 15.1%, respectively) and triplet (16.7% and 8.3%, respectively) regimen patients. Among the patients in the doublet regimen, 78.1% discontinued treatment due to disease progression or death with a significant difference observed between both regimens (p = 0.003), while patients in the triplet regimen (29.2%) terminated their treatment due to reimbursement limitations that were significantly higher than the doublet regimens (4.1%; p = 0.002). The median duration of pomalidomide treatment in doublet and triplet group was observed to be 4.0 and 5.3 months, respectively (). The median PFS was higher in triplet (6.8 months) than doublet regimen (4.7 months) although no significant differences were observed (p = 0.351; A). The DoR was found to be 9.5 months in doublet regimen patients and 8.5 months in triplet regimen patients (B).

Figure 2. Treatment response (A) Progression free survival (B) Duration of response (Patients ≥ PR). Notes: DoR, duration of response; mPFS, median progression free survival; PR, partial response.

Table 2. Pomalidomide-based treatment response comparison.

Factors associated with disease progression

The assessment of risk factors associated with disease progression on pomalidomide-based treatment was carried out using univariate and multivariate analysis for age, treatment regimens, sex, auto-HSCT at new diagnosis, comorbidity, performance status, and prior lenalidomide refractoriness. In univariate analysis, the auto-HSCT at the new disease diagnosis (yes vs no) was the only risk factor associated with disease progression (HR: 0.6, 95% CI: [0.39–1.00], p = 0.050). However, no significant association was reported for any of the factors with disease progression after pomalidomide-based treatment in multivariate analysis ().

Table 3. Factors associated with disease-progression on pomalidomide-based treatment.

Healthcare utilization analysis

The HRU analysis reported comparable utilization across doublet and triplet regimens. Patients in the doublet and triplet regimen were hospitalized for a mean ± SD 22.0 ± 19.0 days and 18.0 ± 22.3 days, respectively. The number of outpatient visit in the doublet and triplet regimen was 10.7 ± 10.4 and 12.4 ± 6.7, respectively. The number of hospitalization (1.6 ± 1.1 and 1.4 ± 0.7, respectively) and ED visits (2.1 ± 1.8 and 2.0 ± 0.9, respectively) were also reported in doublet and triplet regimens ().

Table 4. Healthcare utilization during pomalidomide-based treatment.

Discussion

This retrospective, non-interventional, observational study evaluated the characteristics and treatment patterns of patients with RRMM from a large real-world cohort of five sites in Taiwan. Study findings revealed that most of the patients diagnosed with RRMM in Taiwan were ≥65 years old and were on bortezomib and lenalidomide treatment. Pomalidomide-based triplet regimens reported better response rates than doublet regimens. However, no significant difference in HRU between the doublet and triplet groups was reported. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first real-world evidence comparing two different pomalidomide-based regimens (doublet vs triplet) in Taiwan.

Characteristics of the study patients were representative of the overall MM demographics in Taiwan, with more prevalence in elderly male patients [Citation6,Citation20–22]. More than 50% of the patients in this study were on bortezomib and/or lenalidomide treatment prior to receiving pomalidomide-based treatment. This observation was agreeing to the recent report on the treatment pattern of MM in Taiwan where 50% of 1L treatment included bortezomib, and up to 31.5% of patients received lenalidomide for 2L/3L treatments [Citation9]. Cardiovascular disease and HBV/HCV infection were reported as the comorbidities in both pomalidomide-based groups (doublet and triplet), which is in line with the frequency of these conditions in elderly patients with MM [Citation23]. Common presentation of these comorbidities in both the treatment regimens highlights that the pomalidomide-based treatment used in this study may not interfere with drugs implemented in medications for the diseases. Moreover, this finding points out to the fact that treatment selection was based on potential toxicities that could be avoided for the particular comorbidity.

A doublet regimen of pomalidomide and dexamethasone is an established standard of care for patients with MM who are refractory to both bortezomib and lenalidomide. Although, the efficacy of pomalidomide as a single agent in RRMM is limited, its synergistic effects with dexamethasone are significant [Citation24]. Recent real-world studies have corroborated the safety and efficacy of this combination in Chinese and Taiwanese populations [Citation10,Citation11]. Furthermore, regulatory approvals for various pomalidomide-based triplet regimens, including daratumumab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone and isatuximab plus pomalidomide and dexamethasone, have been backed by real-world evidence [Citation13,Citation14]. However, there is a lack of studies on the comparison of doublet and triplet pomalidomide-based regimens in the real-world setting of Taiwan. In the present study, patients in the triplet regimen reported higher ORR, PR and longer PFS compared to patients who received the doublet regimen. Our findings are agreeing to the previously reported deeper response of triplet pomalidomide-based combination therapy than the doublet regimen in patients with RRMM [Citation14,Citation25].

Disease progression was reported as the most common reason for discontinuation of pomalidomide and dexamethasone treatment [Citation10]. In the present study, 78.1% discontinued the treatment due to disease progression or death in the doublet regimen. Treatment toxicity which is more frequently experienced in the elderly could be a contributing factor to the observed discontinuation [Citation26]. However, the reimbursement limitation was reported as the leading cause of treatment discontinuation in triplet regimens which is not unprecedented due to its cost ineffectiveness compared to doublet regimens [Citation27]. However, no association was reported between disease progression and patient factors like age, sex, ECOG status, and prior lenalidomide refractoriness. In contrast, another multicenter, retrospective study conducted among Taiwanese RRMM patients reported primary lenalidomide refractoriness as a substantial factor associated with less disease progression following pomalidomide and dexamethasone treatment, while auto-HSCT did not show any significant association [Citation10]. Moreover, this is the first real-world study which compared the HRU related to pomalidomide-based treatments. Study findings reported comparable utilization of healthcare across doublet and triplet regimen in Taiwan.

Overall, findings suggest that RRMM patients treated with triplet regimens reported better response rates than doublet regimens. However, the reimbursement criteria limitation in Taiwan prevents the widespread use of the triplet regimen. Hence, relaxing the reimbursement criteria in Taiwan would be beneficial in improving clinical outcomes. Furthermore, the choice of treatment should depend on individual patient factors such as age, organ function, performance status, comorbidities, and the presence of high-risk features such as renal failure and high-risk cytogenetics. Additionally, it is imperative to consider the patient's treatment history, potential side effects, and prior therapies to avoid irreversible and persistent toxicities. Future research to determine biomarkers and pathways that can be targets of different regimens and the possibility of administering more than three drugs without prohibitive toxicity, potentially permitting a lasting remission would be essential.

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the patient selection process for the study was not comprehensive enough to accurately represent the entire RRMM population in Taiwan, thereby increasing the possibility of bias. Secondly, the lack of a control group hinders the proper comparisons and may not provide a thorough representation of the effectiveness of different drugs and treatment regimens. Thirdly, the study lacks detailed adverse events (AEs) information, as it only collected data on reasons for medication discontinuation due to AEs without specifying the type of AEs experienced by patients. In addition, the limited range of factors collected in this study may have overlooked important confounders, potentially affecting our ability to draw conclusive associations and identify significant risk factors linked to disease progression. Finally, this study lacks detailed daily treatment schedules for pomalidomide-based treatment regimens, hindering comprehensive assessment of treatment impact. Although starting doses and number of treatment cycles were provided, the absence of daily schedules limits our analysis. Furthermore, while dosing appears similar between the two groups, slight differences may exist due to the lack of detailed schedules.

Conclusion

In Taiwan, around half of the RRMM patients received a pomalidomide-based regimen at the third line of treatment. Triplet pomalidomide combinations showed a tendency to yield higher ORRs and longer PFS compared to doublet pomalidomide combinations, with comparable HRU. However, the duration of triplet pomalidomide combinations was influenced by reimbursement capping.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the collaborative support of Oracle Life Sciences (formerly known as Cerner Enviza) for overseeing the project, Sulekha Shafeeq (PharmD) and Shalini Vasantha (Ph.D) for the development and editorial support of the manuscript, that was funded by Sanofi Taiwan Co. Ltd.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cowan A, Allen C, Barac A, et al. Global burden of multiple myeloma: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(9):1221–1227. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2128

- Tang CH, Hou HA, Huang KC, et al. Treatment evolution and improved survival in multiple myeloma in Taiwan. Ann Hematol. 2020;99(2):321–330. doi:10.1007/s00277-019-03858-w

- Kazandjian D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: a unique malignancy. Semin Oncol. 2016;43(6):676–681. doi:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.11.004

- Wang J, Lv C, Zhou M, et al. Second primary malignancy risk in multiple myeloma from 1975 to 2018. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14(19):4919. doi:10.3390/cancers14194919

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Globocan 2020. Multiple myeloma [Internet]. [cited 2023 Mar 8]. Available from: https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/35-Multiple-myeloma-fact-sheet.pdf.

- Tang CH, Liu HY, Hou HA, et al. Epidemiology of multiple myeloma in Taiwan, a population based study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;55:136–141. doi:10.1016/j.canep.2018.06.003

- Ministry of Health and Welfare Central Health Insurance Administration. Drug payment regulations [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 28]. Available from: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n = E70D4F1BD029DC37&topn = 3FC7D09599D25979.

- National Health Insurance Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare. The latest version of drug payment regulations (take away the entire copy) - updated on 113.03.25 [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.nhi.gov.tw/ch/cp-13108-67ddf-2508-1.html.

- Liu Y, Tang CH, Qiu H, et al. Treatment pathways and disease journeys differ before and after introduction of novel agents in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):1112. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-80607-4

- Hung YC, Gau JP, Huang SY, et al. Pomalidomide and dexamethasone are effective in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma in a real-life setting: a multicenter retrospective study in Taiwan. Front Oncol. 2021;11:695410. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.695410

- Fu WJ, Wang YF, Zhao HG, et al. Efficacy and safety of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in Chinese patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: a multicenter, prospective, single-arm, phase 2 trial. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):722. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09802-y

- Taiwan Food and Drug Administration [Internet]. [cited 2023 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov.tw/TC/index.aspx.

- Chiu LJ, Kuo CY, Ma MC, et al. Real-world evidence of daratumumab-lenalidomide-dexamethasone in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients: a single-center experience in Taiwan focusing on efficacy. J Cancer Res Pract. 2023;10(1):19–23. doi:10.4103/ejcrp.eJCRP-D-22-00032

- Sunami K, Ikeda T, Huang SY, et al. Isatuximab-pomalidomide-dexamethasone versus pomalidomide-dexamethasone in East Asian patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: ICARIA-MM subgroup analysis. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2022;22(8):e751–e761. doi:10.1016/j.clml.2022.04.005

- Richardson PG, Perrot A, San-Miguel J, et al. Isatuximab plus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone versus pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma (ICARIA-MM): follow-up analysis of a randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(3):416–427. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00019-5

- Taiwan Food and Drug Administration. Assessment Report [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 19]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov.tw/tc/includes/GetFile.ashx?id = f637962576674226128&type = 2&cid = 41446.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. NCT02990338: Multinational clinical study comparing isatuximab, pomalidomide, and dexamethasone to pomalidomide and dexamethasone in refractory or relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma patients (ICARIA-MM) [Internet]. [cited 2023 Apr 19]. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02990338.

- Katkade VB, Sanders KN, Zou KH. Real world data: an opportunity to supplement existing evidence for the use of long-established medicines in health care decision making. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2018;11:295–304. doi:10.2147/JMDH.S160029

- Di Maio M, Perrone F, Conte P. Real-world evidence in oncology: opportunities and limitations. Oncologist. 2020;25(5):e746–e752. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0647

- Liu WN, Chang CF, Chung CH, et al. Clinical outcomes of bortezomib-based therapy in Taiwanese patients with multiple myeloma: a nationwide population-based study and a single-institute analysis. PLoS One. 2019;14(9):e0222522.

- Liu Y, Hou HA, Qiu H, et al. Is the risk of second primary malignancy increased in multiple myeloma in the novel therapy era? A population-based, retrospective cohort study in Taiwan. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14393. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-71243-z

- Chen JH, Chung CH, Wang YC, et al. Prevalence and mortality-related factors of multiple myeloma in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167227.

- Kaweme NM, Changwe GJ, Zhou F. Approaches and challenges in the management of multiple myeloma in the very old: future treatment prospects. Front Med. 2021;8:612696. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.612696

- Fotiou D, Gavriatopoulou M, Terpos E, et al. Pomalidomide- and dexamethasone-based regimens in the treatment of refractory/relapsed multiple myeloma. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022;13:20406207221090090. doi:10.1177/20406207221090089

- Szabo AG, Thorsen J, Iversen KF, et al. The real-world use and efficacy of pomalidomide for relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma in the era of CD38 antibodies. eJHaem [Internet]. 2023 Nov 24;4(4):1006–1012. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002jha2.774

- Baldoni AdO, Chequer FMD, Ferraz ERA, et al. Elderly and drugs: risks and necessity of rational use. Brazilian J Pharm Sci. 2010;46(4):617–632. doi:10.1590/S1984-82502010000400003

- Offidani M, Corvatta L, Gentili S. Triplet vs. doublet drug regimens for managing multiple myeloma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(2):137–149. doi:10.1080/14656566.2017.1418856