Abstract

Previous research indicates that programmes employing Hellison’s Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility (TPSR) model in physical activity have had a positive impact on youth development by increasing participants’ positive values, autonomy, life skills, and prosocial behaviour. Despite encouraging results of the effects of TPSR-based programmes, there remains lack of research on the effective content of these programmes, and their implementation and evaluation. The current protocol article describes the development of a TPSR-based instructor training programme and a plan for an intervention study in which novice instructors learn to understand and apply the TPSR model in practice. The participants of the TPSR-based training intervention study are novice instructors who are matched and randomly allocated to a 20-hour TPSR-based training intervention and a six-hour control instructor training without the TPSR content. The proposed study examines whether the intervention is effective in teaching novice physical activity instructors to understand and apply the TPSR model, whether the instructors’ personal and social responsibility develops, and whether the training intervention is feasible.

Introduction

Programmes aimed at promoting positive values, life skills, and prosocial behaviour among young people through physical activity (Coakley, Citation2011; Gould & Carson, Citation2008; Hardcastle, Tye, Glassey, & Hagger, Citation2015; Holt et al., Citation2017; Lintunen & Gould, Citation2014) are increasing in numbers. However, not every programme has been successful in promoting these adaptive outcomes. Supporting young people’s holistic development requires a high-quality programme with clearly defined objectives, an effective content, and methods of delivery. Alongside these qualities, it is important that the programme is based on social psychological theory that provides an explanation of the mechanism by which manipulable psychological factors impact positive values and behaviours, and outlines how the values and behaviours can be promoted in the social environment of young physical activity participants. The theoretical basis provides a framework to develop a programme and to identify reasons why the intervention would be effective in changing behaviour.

Moreover, instructors of the programmes are of uttermost importance for programmes to successfully promote positive youth development. For instance, how instructors motivate young people, and how instructors evaluate and recognise effort and achievement, play a significant role (Gould & Carson, Citation2008). Furthermore, coaches who through their behaviours and communications create task-involving environments can provide direct psychological and behavioural benefits to their athletes (Atkins, Johnson, Force, & Petrie, Citation2015). Features of task-oriented motivational climate, such as focusing on self-referenced goals and mastery, may facilitate positive youth development climate (Holt et al., Citation2017). Despite that, physical activity programmes for children are often led by instructors without any formal training. These novice instructors usually rely on ad hoc methods of instruction that are based on anecdotal experience and not informed by theory or evidence (Flett, Gould, Griffes, & Lauer, Citation2012). In addition, untrained instructors do not have sufficient experience in providing instruction that can promote the kinds of values and life skills that may enrich learners’ experiences of activities and their future social development. Therefore, the novice instructors are optimal targets for the introduction of the Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility model (TPSR; Hellison, Citation1985, Citation2011). The TPSR model is recognised internationally as a method to foster autonomous, self-directed activity and empower participants to engage in decision making and to take responsibility for their own actions and their relations with others within physical activity context. The ultimate goal of the TPSR method is to have the participants adopt and transfer these skills to their everyday life.

Theoretical rationale for the TPSR model

The TPSR model (Hellison, Citation1985, Citation2011) was originally developed to use physical activity to promote valuable transferrable life skills for young people at risk of being socially excluded. The goal was to provide underserved youth with opportunities to apply the skills that they already possessed to contribute to the society, and to learn new skills to become more responsible citizens. Therefore, TPSR-based programmes focused on providing these opportunities through four themes: integrating responsibility into physical activity, empowering participants to take responsibility, building strong instructor–participant relationships, and promoting transfer of responsibility (Hellison, Citation2011). TPSR-based programmes provide participants with guidelines for, and practice in, taking responsibility for their personal well-being and contributing to the well-being of others. The goals and means of TPSR are in line with social psychology theories, particularly self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000) and self-efficacy theory (Bandura, Citation1994, Citation1997), with theories from sport pedagogy, such as the teaching styles spectrum (Mosston & Ashworth, Citation2008), and with aspects of positive psychology (Maslow, Citation1954; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2000).

The core elements of the TPSR model are reflected in four responsibilities, two related to personal well-being (effort and self-direction) and two related to social well-being (respect for others’ rights and feelings and caring about others) (Hellison, Citation2011). The responsibilities are divided into five levels: (1) respect of the rights and feelings of others, (2) effort and cooperation, (3) self-direction, (4) helping others and leadership, and (5) transfer of responsibility outside the physical activity setting. Levels one and two are essential for the development of responsibility and establishment of a positive learning environment. Levels three and four enhance the learning environment by encouraging independent work, helping roles, and leadership roles. Level five is the end goal, in which the aim is to foster the ability to apply the learned skills outside the learning environment and serve as a responsible role model to others. The latter goal is consistent with an important goal in education and physical literacy: developing transferable skills and motives. This means that the content of the TPSR-based programme is congruent with the goals of teachers, coaches, and instructors in multiple educational contexts (Hagger & Chatzisarantis, Citation2016; Maehr, Citation1976).

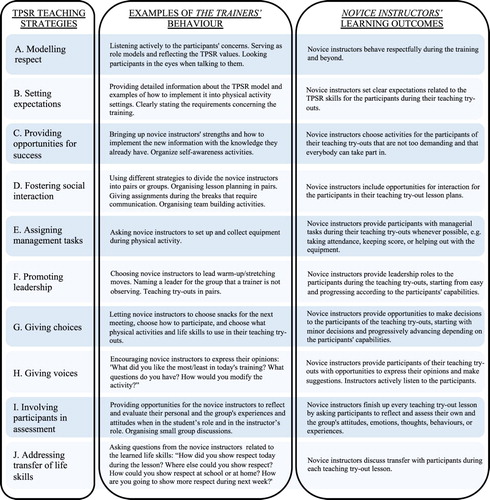

A major challenge with theory and evidence-based programmes is how to apply them in practice. The TPSR model is well placed for translation to practice as it was developed as part of a field work. Hellison (Citation2011) created a lesson format and chose specific teaching strategies (see ) to make it easier for practitioners to implement the essential parts of the model and to assure opportunities for participants to practise and learn personal and social responsibility during each lesson. The lesson format comprises of five components: relational time, awareness talk, physical activity, a group meeting, and reflection time. Relational time refers to unofficial chats between the instructor and the participants aiming at building positive relationships and getting to know each participant individually. Awareness talk marks the official commencement of the physical activity lesson. Awareness talk involves the instructor informing the participants of the plan and purpose of the lesson. After establishing clear expectations for the lesson, participants are given instruction in physical activity, which takes up majority of the lesson. The responsibility-based teaching strategies and life skills are embedded in the physical activity instruction. Life skills here refer to internal personal assets, characteristics, and skills that can be practiced at physical activity setting and transferred to other settings (Gould & Carson, Citation2008). A few minutes before the end of the lesson, a group meeting is arranged. During the meeting participants can express their opinions, make suggestions, ask questions, and evaluate the group’s behaviour. Following the group meeting, participants are asked to engage in brief period of reflection time, during which the participants are given an opportunity to evaluate their own attitude, behaviour or development, and reflect and discuss how to transfer the practiced skills to other settings.

Figure 1. Examples of the TPSR teaching strategies to be used in the experimental training programme and expected learning outcomes.

TPSR-based programmes have been studied and applied in many countries (e.g. USA, Canada, New Zealand, South Korea, and Spain), and in multiple contexts, such as physical education (Beaudoin, Citation2012; Gordon, Citation2012; Hassandra & Goudas, Citation2010; Jung & Wright, Citation2012; Kuusela, Citation2005; Rantala & Heikinaro-Johansson, Citation2007), after-school programmes (Cryan & Martinek, Citation2017; Gordon, Jacobs, & Wright, Citation2016), community-based projects (Buchanan, Citation2001; Walsh, Ozaeta, & Wright, Citation2010; Wright, Citation2012; Wright, Whitley, & Sabolboro, Citation2012), and sports (Wright, Jacobs, Ressler, & Jung, Citation2016). Results are indicating that TPSR-based programmes have positive outcomes for youth. An initial review of 26 studies testing the efficacy of the TPSR model on positive youth development found that 19 of the studies resulted in improved respect, effort, autonomy, and capacity for leadership among athletes and school physical education students (Hellison & Walsh, Citation2002). A more recent systematic review of 22 studies on TPSR-based programmes in physical education setting concluded that successful implementation of TPSR contribute to a range of positive behavioural, social, emotional, psychological, and educational outcomes (Pozo, Grao-Cruces, & Pérez-Ordás, Citation2018). For example, the studies indicate increases in effort, empathy, self-regulated learning, leadership skills, self-efficacy for self-regulation, team work, and personal and social responsibility, as well as reductions in behavioural problems, such as violence against peers and absences from school. The ultimate practical success of TPSR-based programmes is typified by participants that ultimately become co-leaders or leaders for the programmes (Beale, Citation2016; Jacobs, Castaneda, & Castaneda, Citation2016; Martinek & Ruiz, Citation2005).

Although the results of these TPSR-based programmes have been positive, the majority of the studies have been descriptive case studies (for reviews see Hellison & Walsh, Citation2002 and Pozo et al., Citation2018). To date, there remains a lack of well-designed and reported randomised controlled intervention studies.

The training of TPSR instructors

The TPSR model attracts many teachers and coaches with its empowerment-based philosophy and widespread practical implications. However, in many cases, teachers attempt to adopt and apply the strategies of the model with insufficient or no formal training. Although there is no single correct way to implement the TPSR model, a lack of formal training and a lack of consistency in training may introduce considerable variability in the extent to which the programmes are implemented and the fidelity of the interventions (Quested, Ntoumanis, Thøgersen-Ntoumani, Hagger, & Hancox, Citation2017).

Formal TPSR instructor training programmes do not mean rigid and inflexible use of the TPSR model but, rather, systematic application of the basic tenets of the TPSR model and adaption of well-established strategies to the group at hand. TPSR-based instructor training typically consists of an intensive training period or personal meetings with facilitators, followed by an ongoing professional development lasting from a few weeks to a full school year (Beaudoin, Citation2012; Escartí, Llopis-Goig, & Wright, Citation2018; Hemphill, Templin, & Wright, Citation2015). TPSR instructor training programmes often target physical education teachers and focus on their professional development (Beaudoin, Citation2012; Coulson, Irwin, & Wright, Citation2012; Escartí et al., Citation2012; Lee & Choi, Citation2015; Romar, Haag, & Dyson, Citation2015; Hemphill, Templin, & Wright, Citation2015). However, also coaches and high school or college students have been trained to implement TPSR-based programmes (Cutforth & Puckett, Citation1999; Forsberg & Kell, Citation2014; Martinek, McLaughlin, & Schilling, Citation1999; Walsh, Citation2012; Wright et al., Citation2016). Unfortunately, formal research examining the content, structure, implementation strategies, and evaluation of TPSR-based instructor training programmes is limited. There is therefore a need to develop and test formal protocols for TPSR-based instructor training programmes. Developing empirically-verified training programmes would allow replication of the effective training strategies and practices used in TPSR-based interventions and help to interpret the study results and causal mechanisms.

Research on implementation fidelity of TPSR-based programmes is scarce, but results from the few existing studies have revealed challenges with teachers’ compliance with the essential components of the TPSR model in the delivery of the programmes (Escartí et al., Citation2018; Lee & Choi, Citation2015; Pascual et al., Citation2011). In fact, teachers’ compliance to the content is an issue that has been noted for many interventions in physical activity contexts (Quested et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, Martinek and Hellison (Citation2016) pointed out that focusing on personal strengths and available resources and enhancing interpersonal processes between students and instructors is essential for increasing the prospects of successful implementation of a TPSR programme.

Aims

The overall aim of this protocol article is to describe the development of a TPSR-based training programme for novice physical activity instructors and to outline plans for its implementation and subsequent evaluation. The specific aims of this article are:

To develop a theory- and evidence-informed training programme for novice physical activity instructors using Hellison’s (Citation1985, Citation2011) TPSR model. Specifically, the objective is to describe the structure, content, training strategies, delivery, and target learning outcomes of the programme.

To describe the protocol for a randomised controlled study of a TPSR-based instructor training intervention. The aim of the intervention is to teach novice instructors to understand and apply the TPSR model to later promote personal and social responsibility and positive youth development in physical activity and sport context.

Method

The following section presents the protocol for the intervention study. The study protocol provides a full description of the development, components, and design of the intervention. It also enables faithful implementation and evaluation of the intervention and allows utilisation of the intervention or components of it outside the current study (Craig et al., Citation2008; Quested et al., Citation2017).

Participants and setting

The training programme is organised and implemented by the first and last author. Participants of the training intervention are final year high school or vocational school students or recent graduates. The novice instructors’ training programme is organised in a university and in different sport facilities in Central Finland. The after-school physical activity programmes are organised in urban schools in Central Finland.

Design

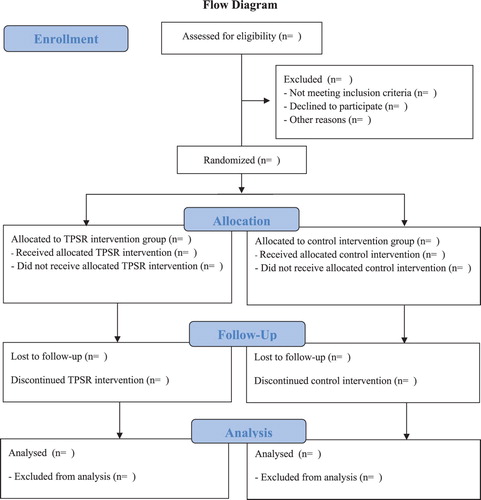

This is a protocol for a covariate adaptive randomised controlled intervention study. The TPSR-based training intervention study is performed with novice experimental and novice control group instructors. According to covariate adaptive randomisation (Lin, Zhu, & Su, Citation2015; Treasure & MacRae, Citation1998), applicants are matched and paired based on age, sex, physical activity experience (i.e. years of participation in organised physical activity), instructing experience (i.e. years of instructing experience), instructor training (i.e. number and level of instructor training), and social confidence. Each participant in the pair is then randomly allocated across the experimental (TPSR) and control groups. Eight pairs are selected to participate. The remaining participants are placed on a waiting list and invited to participate in case of a drop-out before the start of the training. Matching is performed by the first and last author, but they are blind to the groups to which the participants are randomised. A statistician, not involved in the study, generates the allocation sequence, assigns the participants to the groups, and keeps the allocation information in a safe and separate place not accessible to the researchers to ensure the concealment of allocation (Viera & Bangdiwala, Citation2007). The intended participants’ flow is displayed in .

The current research questions and intervention evaluation are well suited to the mixed-method approach. The programme development and evaluation require qualitative data to describe the implementation processes and feasibility of the training programme. In addition, the quantitative outcome measures are used to evaluate the feasibility of the measurement package, training intervention, and design. As we aim to develop the programme and to assess feasibility, we examine whether this study can be performed and whether the components of the study can all work together (see Eldridge et al., Citation2016). Quantitative and qualitative data is needed to track and report differences in the primary, secondary, and additional outcomes between the experimental and control groups. The planned intervention can also be defined as a real-world and practice-oriented case and action research study (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2007; Rovio, Eskola, Gould, & Lintunen, Citation2009), in which processes of learning responsibility and learning to teach responsibility can be analysed from the longitudinal qualitative data with different novice instructors considered as cases. The design of the study enables getting feedback and optimising the intervention prior to proceeding to a full-scale future trial. In addition, this design allows future replication of the effective training strategies and practices used in the intervention.

Recruitment

Novice instructors are recruited through local high schools and vocational schools (e.g. online message boards and emails). All applicants are required to make a short introduction video of themselves, in which they are asked to share their current occupation, physical activity background, favourite physical activities, instructing experience and training, reasons for applying, and interests and concerns regarding the study. The instructors must be adults (18 years or older) who have some experience in organised physical activity, for example, as a participant. However, they should not have extensive coaching, teaching, or instructing experience (full time position for over 6 months or part-time position for over 1 year) or training (high level coaching or teaching certificate, or multiple trainings). It is also important to consider that the selected instructors are suited for working with young people and are interested in helping youth with physical activity and beyond. Success of recruitment is evaluated by recording the number of applicants to estimate whether we can attract enough eligible participants.

The development of the training programmes

When developing a TPSR-based training programme, there is considerable risk of compromising the quality of the programme in the absence of sufficient expertise and a network of people to create it. The development process is made especially challenging by the absence of available TPSR-based training intervention protocols and manuals. Therefore, the development of the TPSR-based instructor training programme was informed by theory, evidence synthesis, and advice from experts. The planning of the training programme required the research team to gain an in-depth understanding of the TPSR model. To achieve this, the first and last author participated in workshops on TPSR model. The first author also received individual one-on-one training by the second author, an expert on the model and colleague of Hellison, the creator of the TPSR model. The individual training consisted of implementing the TPSR in a soccer programme and learning to use the Tool for Assessing Responsibility-based Education (TARE; Wright & Craig, Citation2011) and TARE 2.0 (Escartí, Wright, Pascual, & Gutiérrez, Citation2015), which are described in the measures section. The first author performed parallel TARE observations with the second author in live field practice setting and achieved 80% agreement in their observations.

The design and programme components and materials were pilot-tested by organising TPSR-based training for ten novice physical activity instructors and control training for eight novice physical activity instructors. Minor changes were made to the recruitment process (e.g. switching an email application to video application) and the final programme such as inviting youth groups instead of using only peers as participants on the teaching try-outs and switching up some team building activities to better highlight the determined topics.

The TPSR-based training programme

The TPSR-based instructor training is an intensive 20-hour programme consisting of seven meetings organised over four weeks. The training is organised in the early autumn before the school year starts. The theoretical and practical framework of the training programme is Hellison’s (Citation1985, Citation2011) TPSR model. The training programme includes instruction in theoretical knowledge, model lessons, observation, and teaching try-outs (i.e. practical application of the responsibility-based teaching strategies, responsibility levels, lesson format, and life skills). Throughout the programme the TPSR themes and values are emphasised. In addition, the programme contains information and examples of physical activity content and introduction of some general pedagogical and psychological principles related to leading a group.

The first two meetings are organised in a university classroom. The first meeting focuses on introducing the study and setting clear expectations for the novice instructors concerning their participation. The second meeting is dedicated to the theoretical and conceptual basis, central values, ideas, and implementation strategies of the TPSR model. Several different activities are also organised during both meetings to help the novice instructors to get to know each other, to become aware of their own emotions and thoughts, and to create a positive, open, and safe learning environment in the group.

The next three meetings are organised in a university gymnasium. The third meeting consists of two model lessons, in which the trainers provide instruction on physical activity to the novice instructors. The TPSR model is embedded in the physical activity lessons including the themes, values, lesson format, empowerment-based teaching strategies, life skills, and responsibility levels. After each model lesson, time is dedicated to discussion and questions regarding the lesson and the TPSR model. After the novice instructors have gained an experience of being a participant in a TPSR-based lesson and have an understanding of how to embed the model into physical activity instruction, they plan a TPSR-based physical activity lesson in pairs. The plan includes the physical activity and responsibility goals of the lesson, the physical activity content, and the content of the awareness talk, group discussion, and reflection time. The trainers are especially encouraged to use the lesson format and teaching strategies to emphasise life skills including the transfer of life skills. The novice instructors are also encouraged to plan how to share the responsibility between the two instructors during the teaching try-out.

In the fourth meeting, the novice instructors act out their plan and complete their first teaching try-out by leading a TPSR-based physical activity lesson to their peers. After each teaching try-out, the instructors receive feedback from the trainers and from their peers. After the fourth meeting, the instructors develop a further lesson plan with the same partner and in the fifth meeting complete their second teaching try-out by leading a group of young voluntary athletes. In all the meetings, the novice instructors are encouraged to ask questions and share their ideas. In addition, team building and self-expression activities are organised to help the novice instructors to get to know each other better, express themselves in a positive manner, and improve their teamwork skills. After each teaching try-out, the novice instructors are asked to reflect on their own instructing behaviour by using the TARE post-teaching reflection sheet (Hellison & Wright, Citation2011).

The last two meetings are organised in pairs in different sport facilities. Prior to the sixth meeting, the novice instructors contact a sport coach and ask for a permission to come to observe one of their practices. In the sixth meeting, the novice instructors are using an observation sheet to evaluate the coaches’ behaviour and use of the TPSR teaching strategies in a real-life setting. The trainers are using the TARE (Wright & Craig, Citation2011) to observe the coaches. After the observation, the novice instructors share their observations and evaluations with the coaches and discuss about them more in detail with the trainers and their partner. Prior to the seventh meeting, the novice instructors contact another sport coach and ask for a permission to come to lead one practice. The pairs plan the lessons and in the final meeting complete their third teaching try-out by leading a sport practice for a sport team in a real-life setting and receiving feedback from the trainers and their co-instructor. After the meeting, the novice instructors evaluate their own instructing behaviour by using the TARE post-teaching reflection sheet (Hellison & Wright, Citation2011). All the meetings are video recorded except the sixth meetings when sport coaches are observed. For more detailed content of each meeting, see Table 1 in the supplement.

The control training programme

The objective of the control training programme is to serve as a comparison for the TPSR-based instructor training programme. The training programme of the control group enables novice instructors to learn how to create an active, positive, and functional physical activity environment. The control training is an intensive six-hour programme consisting of two meetings organised one day apart. The control training programme does not include any of the elements of the TPSR model. The control training includes only one teaching try-out for voluntary young athletes but no model lessons or observation of practices.

The first meeting is organised in a classroom at the university and focuses on introducing the study and setting clear expectations for the novice instructors concerning their participation. A few different activities are also organised during the meeting to help the novice instructors to get to know each other, to become aware of their own emotions and thoughts and to create a positive, open, and safe learning environment in the group. During the first meeting, the novice instructors in pairs also start planning a physical activity lesson for a group of young voluntary athletes focusing on organising a fun physical activity lesson.

The second meeting is organised in a gym at a university and consists of novice instructors in pairs completing their teaching try-outs by leading physical activity lesson to a group of young voluntary athletes. Each instructor pair receives feedback for their performance and cooperation from the trainers and their peers after the lesson. In addition, a team building and a self-expression activity are organised during the meeting to help the novice instructors to get to know each other better, express themselves in a positive manner, and improve their teamwork skills. Both of the meetings are video recorded. For more detailed content of both meetings, see Table 2 in the supplement.

Measures

Data is collected at the beginning, during, and at the end of the training, as well as four months, six months, and three years after the training intervention ().

Figure 3. Measures of the TPSR-based novice physical activity instructor training intervention.

1. A researcher's log; 2. The tool for assessing responsibility-based education (TARE); 3. TARE 2.0; 4. The TPSR implementation checklist; 5. The TARE post-teaching reflection sheet; 6. A TPSR knowledge test; 7. An observation sheet; 8. The self-efficacy for personal-social skills questionnaire; 9. The personal and social responsibility questionnaire (PSRQ); 10. The perceived autonomy support questionnaire; 11. The perceived (instructor) competence subscale; 12. The acceptance subscale (relatedness); 13. A training intervention feedback; 14. The lesson plans; 15. The Short Schwartz's Value Survey (SSVS); 16. The children's version of the Perceptions of Success Questionnaire (POSQ-CH); 17. Regularity of physical activity; 18. A focus group interview; 19. Personal interviews.

Primary outcome measures

Teaching personal and social responsibility

The Tool for Assessing Responsibility-based Education (TARE; Wright & Craig, Citation2011) is used to quantitatively assess the novice instructors’ implementation of the TPSR model during the teaching try-outs. The TARE is comprised of three main parts: (1) ten observable teaching strategies (see ), (2) four personal-social responsibility themes (i.e. integration, empowerment, instructor-participant relationship, transfer), and (3) participants’ responsibility in the categories of self-control, participation, effort, self-direction, and caring. Part one uses time-sampling methodology in five-minute intervals to document instructors’ use of ten discrete responsibility-based teaching strategies on a binary scale (1 = observed and 0 = not observed). Part two uses ratings based on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never and 4 = extensively) and part three ratings based on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = very weak and 4 = very strong).

The TARE 2.0 (Escartí et al., Citation2015) is used to quantitatively evaluate the novice instructors’ implementation of the TPSR model from the video recordings. The TARE 2.0 comprises of two parts. Part one consists of the ten observable teaching strategies (see ) rated on a 5-point scale (0 = absent and 4 = very strong). Three-minute intervals are used. The second part consists of observing nine student interactions (i.e. participation, engagement, showing respect, cooperating with peers, encouraging others, helping others, leading, expressing voice, asking for help) using the same interval sampling method (i.e. three-minute intervals and five-point scale) as in part one with the instructors.

The TPSR implementation checklist (Wright & Walsh, Citation2018) is used during the teaching try-outs to quantitatively assess the implementation of the TPSR model by recording, which of the five responsibility levels (i.e. respect, self-motivation, self-direction, caring, transfer), the ten teaching strategies (see ), the five parts of the lesson format (i.e. relational time, awareness talk, physical activity with responsibility, group meeting, reflection time), and the nine students behaviours (i.e. participating, engaging, showing respect, cooperating, encouraging others, helping others, leading, expressing voice, asking for help) are observed. The appropriate items on a checklist are marked to indicate that those items were observed during the lesson.

The TARE post-teaching reflection sheet (Hellison & Wright, Citation2011) is a self-report compliment to the TARE (Wright & Craig, Citation2011), which is used to assess the implementation of the TPSR model. The novice instructors evaluate their behaviour and the behaviour of the physical activity participants after each teaching try-out. The reflection sheet consists of five parts: (1) brief overview of the lesson; (2) ten responsibility-based teaching strategies (see ); (3) four personal-social responsibility themes (i.e. integration, empowerment, instructor-participant relationship, transfer); (4) participants’ responsibility in the categories of self-control, participation, effort, self-direction, and caring; and (5) additional comments or plans. Novice instructors use parts two and three of this sheet to quantitatively assess their own implementation of the responsibility-based teaching strategies and TPSR themes. Ratings are based on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never and 4 = extensively). Part four of the TARE post-teaching reflection sheet, novice instructors use to quantitatively assess behaviour of the physical activity participants. Ratings are based on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = very weak and 4 = very strong). Parts one and five are used by novice instructors to qualitatively assess the lesson by writing a brief overview of the lesson and additional comments or plans.

A TPSR knowledge test is used to qualitatively assess the novice instructors’ understanding of the TPSR model at the end of and four months after the training intervention. The TPSR knowledge test consists of eight open ended questions (e.g. “Explain in your own words, what the TPSR model is.” and “How can an instructor foster social interaction?”) and three listing questions (e.g. “List the five responsibility levels.”).

The self-efficacy for personal-social skills questionnaire (Martin, McCaughtry, Hodges-Kulinna, & Cothran, Citation2008) is an eight-item questionnaire to quantitatively assess the novice instructors’ self-efficacy beliefs regarding their ability to teach personal and social skills (“For each item, please rate how confident you are that you can teach that objective through physical activity programme.” is followed by items, such as “self-control”, “respect for others” and “cooperation”). Ratings are based on an 11-point Likert scale (0 = not confident at all and 10 = extremely confident).

An observation sheet is used by the novice instructors when observing sport coaches and the peers’ teaching try-outs during the training intervention. The observation sheet qualitatively assesses novice instructors’ ability to recognise the components of the TPSR model and other pedagogical and psychological markers. The sheet consists of 10 open ended questions (e.g. “Which life skills were evident and how?”, “What did you notice regarding organisation of the lesson?”)

A semi-structured focus group interview is organised to the trained novice instructors of the intervention group to qualitatively assess the novice instructors’ ability to understand and apply the TPSR model.

Semi-structured personal interviews are used to qualitatively assess the novice instructors’ TPSR knowledge and application of it.

A researcher’s log is used to qualitatively assess the novice instructors’ and the physical activity participants’ behaviour during the teaching try-outs. Researcher’s log comprises of field observations and conversations, which are confirmed afterwards from the video recordings of the training intervention.

Secondary outcome measures

Personal and social responsibility

The personal and social responsibility questionnaire (PSRQ; Li, Wright, Rukavina, & Pickering, Citation2008) is a 14-item questionnaire to quantitatively assess novice instructors’ perceived personal and social responsibility. Ratings are based on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 6 = strongly agree).

Semi-structured personal interviews are organised to qualitatively assess trained novice instructors’ perceptions of their personal and social responsibility and changes in it.

A researcher’s log is used to qualitatively assess the trainers’ perceptions of the novice instructors’ ability to take personal and social responsibility throughout the training intervention.

Basic psychological need satisfaction

The perceived competence subscale of the Intrinsic Motivation Inventory (McAuley, Dunkan, & Tammen, Citation1989) is used to quantitatively assess the novice instructors’ perceived competence to instruct physical activity. Minor adjustments in wording are made to enhance the items’ relevance to instructor competence (e.g. “I think I am quite good at instructing physical activity”). The five-item subscale is used with ratings ranging on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree). The Finnish version (Ervola & Ridanpää, Citation2009) is used.

The acceptance subscale of the need for relatedness scale (Richer & Vallerand, Citation1998) is a five-item scale used to quantitatively assess the novice instructors’ perceptions of relatedness in the training intervention. Minor adjustments in wording are made to enhance the items’ relevance to the training intervention (“In this training programme, I felt … ” followed by items, such as “supported”, “valued”, and “safe”). Ratings are based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). The Finnish version (Ervola & Ridanpää, Citation2009) is used.

The perceived autonomy support questionnaire (Quested & Duda, Citation2011) is a 7-item scale used to quantitatively assess the degree to which the novice instructors perceive trainers as supporting their autonomy. Minor adjustments in wording are made to enhance the items’ relevance to the training intervention (e.g. “Trainers provided me with choices and options.”). Ratings are based on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree). The Finnish version (Ervola & Ridanpää, Citation2009) is used.

A researcher’s log is used to qualitatively assess the trainers’ ability to support the basic psychological needs of novice instructors’ during the training intervention.

Additional outcome measures

The feasibility of the training intervention

An open-ended question (“What do you expect from the training programme?”) is used to qualitatively assess the novice instructors’ expectations prior to the training programme.

A training intervention feedback is used to qualitatively and quantitatively assess novice instructors’ perceptions of the feasibility of the training intervention. The feedback form consists of five open ended questions (e.g. “What did you dislike about the training intervention?”, “How could the training intervention be improved?”) and 14 statements (e.g. “I was satisfied with the training intervention.”, “I understand the TPSR model well.”, “The training intervention included appropriate amount of theory.”) rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree).

Novice instructors’ and trainers’ lesson plans are used to qualitatively assess the implementation of the teaching try-outs and model lessons. The lesson plan template includes background information (i.e. date and place of instruction, number of students, name of the instructors, and topic and life skills of the lesson) and the plan for the lesson (i.e. physical activity and life skill goals, lesson content divided into awareness talk, physical activity time, and group meeting/reflection time, as well as time spent on each activity, and other comments).

A semi-structured focus group interview is organised for the novice instructors of the intervention group and used to qualitatively assess their experiences and perceptions of the feasibility of the training intervention.

A researcher’s log is used to qualitatively assess the trainers’ perceptions of the feasibility of the training intervention. The log comprises of field observations and conversations, which are confirmed afterwards from the video recordings of the training intervention. Adverse events are monitored by the trainers and addressed in the researcher’s log. The trainers’ also keep track of attendance, components delivered, time used, and the quality of delivery.

Explanatory measures

Instructors’ values

The Short Schwartz’s Value Survey (Schwartz, Citation1992, Citation1996) is used to quantitatively assess novice instructions perceptions of specific values. The survey consist of 10 items (“Please rate the importance of the following values as a life-guiding principle for you” followed by items, such as “achievement (success, capability, ambition, influence on people and events)” and “self-direction (creativity, freedom, curiosity, independence, choosing one’s own goals)”), rated on 9-point Likert scale (0 = opposed to my principles and 8 = of supreme importance). The validity and reliability of the Finnish version have been reported in Lindeman and Verkasalo (Citation2010).

Instructors’ goal orientation

The children’s version of the Perceptions of Success Questionnaire (POSQ-CH; Roberts, Treasure, & Balague, Citation1998) is used to quantitatively assess novice instructors’ goal orientation. The questionnaire consists of 12 items (“In physical activity, I feel most successful when … ” followed by phrases, such as “I try hard” and “I do better than others”.). Ratings are based on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). The validity and reliability of the Finnish version have been reported in Liukkonen and Leskinen (Citation1999).

Physical activity

Novice instructors’ regularity of physical activity (Vuori, Kannas, & Tynjälä, Citation2004) is quantitative assessed with the following two items: (1) “Over the past 7 days, on how many days were you physically active for a total of at least 60 min per day?” and (2) “How many hours a week do you usually exercise in your free time so much that you get out of breath or sweat?”. Response for the first item is number of days and response options to the second item are: “none”, “about half an hour”, “about 1 h”, “about 2–3 h”, “about 4–6 h”, or “about 7 h or more”.

Demographics

The novice instructors report their age, gender, education, occupation, physical activity background, favourite sports, instructing experience, and instructing training in the video application during the recruitment phase.

Data analyses

Descriptive statistics about the quantitative measures of primary, secondary, and additional outcomes are reported. Inter-rater reliability scores are calculated for the TARE (Wright & Craig, Citation2011) and the TARE 2.0 (Escartí et al., Citation2015) and percent agreement between independent observations are reported. Differences in the primary, secondary, and additional outcomes between the experimental and control groups are analysed using non parametric tests. Explanatory measures are used to explain possible differences in group comparison.

Video recorded discussions from the training, and focus group and personal interviews are transcribed verbatim. Both theory and data driven (abductive) content analytical procedures (Magnani, Citation2001) are used with all the qualitative data. The qualitative analysis software ATLAS.ti 7 (Friese, Citation2012) is used to extract themes that describe the instructors’ responsibility related teaching and personal behaviours, events that occur during the intervention, and the feasibility of the training programme. In the second phase, all the findings are organised on a time-line in chronological order. Any excerpts requiring clarification for meaning and context are further clarified through concept mapping (Atkinson & Delamont, Citation2005; Rovio, Arvinen-Barrow, Weigand, Eskola, & Lintunen, Citation2010).

A number of procedures are used to enhance trustworthiness (Patton, Citation2015). Data triangulation is achieved through the varied data sources and methodological triangulation through integration of quantitative and qualitative methods. The two researchers involved in programme delivery, engage in critical self-reflection to ensure their connection to the programme does not bias their interpretations. After all data is collected, another researcher, who is not involved in the study, conducts an audit trail to ensure that the data is complete, comprehensive, and free from bias. Finally, interpretive member checks are organised with some of the trained instructors. The trustworthiness of the findings is also enhanced by researchers’ reflexivity, immersion in the project, extensive interactions with the trained instructors, and search for disconfirming evidence.

Ethics statement

This study was carried out in accordance with “Responsible conduct of research and procedures for handling allegations of misconduct in Finland” – guidelines by the Finnish Advisory Board of Research Integrity. All the subjects gave written informed consent. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Jyväskylä (No. 29062015).

Discussion

This protocol article describes the development of the TPSR-based training programme for novice physical activity instructors and outlines plans for its implementation and subsequent evaluation. We have created and described here a detailed plan to facilitate novice physical activity instructors’ understanding and teaching of personal and social responsibility.

This study addresses four central gaps in the evidence base of TPSR-based programmes and instructor training. First, there are no published protocols on TPSR-based programmes or instructor trainings. Therefore, this protocol article, which demonstrates the guidelines for conducting the study, illustrates what will be done in the study, and presents how the study will be evaluated, is first in the field. The protocol allows future replication of the effective training strategies and practices used in the intervention, helps to interpret our study results and causal mechanisms, enhances transparency of our research, reduces our publication bias, prevents selective reporting of our research, and finally helps to determine whether comprehensive and multilevel evaluation and later scaling-up of our study is justified (Chan, Citation2005).

Second, there are no randomised controlled intervention studies of TPSR-based instructor trainings programmes. In fact, majority of the previous studies on TPSR have been qualitative case studies (for reviews see Hellison & Walsh, Citation2002; Pozo et al., Citation2018). Therefore, we conduct a unique covariate adaptive randomised controlled pilot study to test the feasibility of the intervention, training programme, and measures. The current study uses carefully selected quantitative and qualitative data collection methods ensuring the collection of versatile and comprehensive data that also reflects instructors’ point of view and allow for methodological triangulation between quantitative and qualitative information sources. Careful selection and testing of measures is central to explore the mechanisms behind possible changes or differences in the future trial phase. The random selection of participants helps us to reduce bias, whereas having a control group allows us to test the impact of the TPSR. This design allows future replication of the effective training strategies and practices used in the intervention.

Third, to our knowledge, there are no published TPSR-based training interventions for novice instructors. Usually, the instructors are experienced educators (e.g. Hemphill, Citation2015), students studying under expert supervision (e.g. Walsh, Citation2012), or long-term participants of TPSR-based programmes (e.g. Martinek & Ruiz, Citation2005) and therefore, formal instructor training is not required. Furthermore, the TPSR-based programmes are often organised with a specific curriculum or for challenging groups of children, requiring the programme leaders to possess extensive pedagogical and psychological knowledge (Hellison, Citation2011), which novice instructors do not have and cannot learn during a short training programme. However, TPSR-based programmes can be utilised in different contexts and with different target groups. In the current study, novice instructors apply the model in after-school physical activity programmes that do not have any curricular demands and are not organised for troubled students. Therefore, the programme leaders can be, and often in Finland are, novice instructors. These instructors do not generally receive any training or have any method to rely on when they go to lead the programmes. Furthermore, novice instructors rarely hold any strong values and beliefs regarding teaching and are eager to learn any new method to help them to lead a group. Therefore, formally training them to understand and apply the TPSR model is a great way to give them a framework and an opportunity to teach life skills for the students in the after-school programmes and to create a safe learning environment, which is essential for physical activity motivation.

Finally, the research on the TPSR model in Finland is scarce. Prior to this study, the TPSR model has been used only a few times in physical education context (Kuusela, Citation2005; Rantala & Heikinaro-Johansson, Citation2007; Romar, Haag, & Dyson, Citation2015). Therefore, organising a training programme for novice physical activity instructors, who later apply it to after-school physical activity programmes, expands the understanding and use of the model in the Finnish context. The core values of the model fit well in the Finnish culture and educational system, which makes it easier for the novice instructors to adopt the model. Lastly, the components of the model are adapted to Finnish language, which is going to help with the dissemination of the model in the future.

Some limitations apply for the present implementation and evaluation of the TPSR-based training intervention. First, only a small group of novice instructors can be trained at once. Larger number of participants would require longer training period and more resources. The low number of participants does not, therefore, allow us to examine programme effectiveness. However, by developing the training programme for novice instructors and by assessing the feasibility of the programme and the measures, we provide a solid base for future effectiveness studies using larger samples. A challenge for future application of this TPSR-based instructor training is that it is time-consuming. It is important that the novice instructors gain experience in and receive feedback on using the model instead of just attaining the knowledge. Moreover, they also need time for reflection between meetings and at the same time it is important to keep them focused on the training.

This study will enrich the research literature by providing theory and practice informed plans to study learning processes of novice instructors’ responsibility related behaviour and teaching. In addition, piloting and feasibility evaluation will provide a basis for further development of an intervention study so that the trial is refined and feasible for later full evaluation in a large-scale randomised controlled trial.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (118.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to show their gratitude to Dr. Don Hellison for encouragement and feedback in the early stage of the study.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1661268 description of location.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atkins, M. R., Johnson, D. M., Force, E. C., & Petrie, T. A. (2015). Peers, parents, and coaches, oh my! The relation of the motivational climate to boys’ intention to continue in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 170–180.

- Atkinson, P., & Delamont, S. (2005). Qualitative research traditions. In C. Calhoun, C. Rojek, & B. Turner (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of sociology (pp. 40–60). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bandura, A. (1994). Self-efficacy. In V. S. Ramachaudran (Ed.), Encyclopedia of human behavior (Vol. 4, pp. 71–81). New York: Academic Press. (Reprinted in H. Friedman [Ed.], Encyclopedia of Mental Health. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998.)

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-Efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W. H. Freeman.

- Beale, A. (2016). Making a difference: TPSR, a new wave of youth development changing lives one stroke at a time. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 87(5), 31–34. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2016.1157392

- Beaudoin, S. (2012). Using responsibility-based strategies to empower in-service physical education and health teachers to learn and implement TPSR. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14(2), 161–177.

- Buchanan, A. M. (2001). Contextual challenges to teaching responsibility in a sports camp. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 20(2), 155–171.

- Chan, A.-W. (2005). Bias, spin, and misreporting: Time for full access to trial protocols and results. PLoS Medicine, 5(11), e230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050230

- Coakley, J. (2011). Youth sports: What counts as ‘positive development? Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 35(3), 306–324. doi: 10.1177/0193723511417311

- Coulson, C., Irwin, C., & Wright, P. M. (2012). Applying Hellison’s responsibility model in a youth residential treatment facility: A practical inquiry project. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14, 38–54.

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Ritchie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. BMJ, 337, a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Creswell, J., & Plano Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Cryan, M., & Martinek, T. (2017). Youth sport development through soccer: An evaluation of an after-school program using the TPSR model. The Physical Educator, 74(1), 127–149. doi: 10.18666/TPE-2017-V74-I1-6901

- Cutforth, N. J., & Puckett, K. (1999). An investigation into the organization, challenges, and impact of an urban apprentice teacher program. The Urban Review, 31, 153–172.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227–268. doi: 10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., & Bond, C. M. (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: Development of a conceptual framework. PLoS ONE, 11(3), e0150205. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

- Ervola, E., & Ridanpää, J. (2009). Hyvinvoiva tanssija: Psykologisten perustarpeiden, motivaation ja hyvinvoinnin yhteydet huipputanssijoilla (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä.

- Escartí, A., Llopis-Goig, R., & Wright, P. (2018). Assessing the implementation fidelity of a school-based teaching personal and social responsibility program in physical education and other subject areas. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2016-0200

- Escartí, A., Pascual, C., Gutiérrez, M., Marín, D., Martínez, M., & Tarín, S. (2012). Applying the teaching personal and social responsibility model (TPSR) in Spanish schools’ context: Lesson learned. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14(2), 178–196.

- Escartí, A., Wright, P. M., Pascual, C., & Gutiérrez, M. (2015). Tool for assessing responsibility-based education (TARE) 2.0: Instrument revisions, inter-rater reliability, and correlations between observed teaching strategies and student behaviors. Universal Journal of Psychology, 3(2), 55–63. doi: 10.13189/ujp.2015.030205

- Flett, M., Gould, D., Griffes, K., & Lauer, L. (2012). The views of more versus less experienced coaches in underserved communities. International Journal of Coaching Science, 6(1), 3–26.

- Forsberg, N., & Kell, S. (2014). The role of mentoring in physical education teacher education: A theoretical and practical perspective. Physical & Health Education Journal, 80(2). 6–11.

- Friese, S. (2012). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti. London: Sage.

- Gordon, B. (2012). Teaching personal and social responsibility through secondary school physical education: The New Zealand experience. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14(1), 25–37.

- Gordon, B., Jacobs, J. M., & Wright, P. M. (2016). Social and emotional learning through a teaching personal and social responsibility-based after school program for disengaged middle school boys. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 35(4), 358–369. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2016-0106

- Gould, D., & Carson, S. (2008). Life skills development through sport: Current status and future directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 58–78. doi: 10.1080/17509840701834573

- Hagger, M. S., & Chatzisarantis, N. L. D. (2016). The trans-contextual model of autonomous motivation in education: Conceptual and empirical issues and meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 360–407. doi: 10.3102/0034654315585005

- Hardcastle, S. J., Tye, M., Glassey, R., & Hagger, M. S. (2015). Exploring the perceived effectiveness of a life skills development program for high-performance athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16(3), 139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.10.005

- Hassandra, M., & Goudas, M. (2010). An evaluation of a physical education program for the development of students’ personal and social responsibility. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 7, 275–297.

- Hellison, D. (1985). Goals and strategies for teaching physical education. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Hellison, D. (2011). Teaching personal and social responsibility through physical activity (3rd ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Hellison, D., & Walsh, D. (2002). Responsibility-based youth program evaluation: Investigating the investigations. Quest, 54, 292–307.

- Hellison, D., & Wright, P. M. (2011). Assessment and evaluation strategies. In D. Hellison (Ed.), Teaching personal and social responsibility through physical activity (pp. 427–475). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Hemphill, M. A. (2015). Inhibitors to responsibility-based professional development with in-service teachers. The Physical Educator, 72, 288–306. doi: 10.18666/TPE-2015-V72-I5-5756

- Hemphill, M. A., Templin, T. J., & Wright, P. M. (2015). Implementation and outcomes of a responsibility-based continuing professional development protocol in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(3), 398–419. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2012.761966

- Holt, N. L., Neely, K. C., Slater, L. G., Camiré, M., Côté, J., Fraser-Thomas, J., & Tamminen, K. A. (2017). A grounded theory of positive youth development through sport based on results from a qualitative meta-study. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10, 1–49. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2016.118 0704

- Jacobs, J. M., Castaneda, A., & Castaneda, R. (2016). Sport-based youth and community development: Beyond the ball in Chicago. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 87(5), 18–22. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2016.1157386

- Jung, J., & Wright, P. M. (2012). Application of Hellison’s responsibility model in South Korea: A multiple case study of ‘at-risk’ middle school students in physical education. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14, 140–160.

- Kuusela, M. (2005). Sosioemotionaalisten taitojen harjaannuttaminen, oppiminen ja käyttäytyminen perusopetuksen kahdeksannen luokan tyttöjen liikunnantunneilla (Doctoral thesis, University of Jyväskylä). LIKES. Liikunnan ja kansanterveyden julkaisuja (165): Jyväskylä.

- Lee, O., & Choi, E. (2015). The influence of professional development on teachers’ implementation of the teaching personal and social responsibility model. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 34, 603–625. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2013-0223

- Li, W., Wright, P. M., Rukavina, P. B., & Pickering, M. (2008). Measuring students’ perceptions of personal and social responsibility and the relationship to intrinsic motivation in urban physical education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 27, 167–178.

- Lin, Y., Zhu, M., & Su, Z. (2015). The pursuit of balance: An overview of covariate-adaptive randomization techniques in clinical trials. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 45, 21–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2015.07.011

- Lindeman, M., & Verkasalo, M. (2010). Measuring values with the short Schwartz’s value survey. Journal of Personality Assessment, 85(2), 170–178. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8502_09

- Lintunen, T., & Gould, D. (2014). Developing social and emotional skills. In A. G. Papaioannou, & D. Hackfort (Eds.), Routledge companion to sport and exercise psychology (pp. 621–633). London: Routledge.

- Liukkonen, J., & Leskinen, E. (1999). The reliability and validity of scores from the children’s version of the perceptions of success questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 59(4), 651–664.

- Maehr, M. L. (1976). Continuing motivation: An analysis of a seldom considered educational outcome. Review of Educational Research, 46(2), 443–462. doi: 10.3102/00346543046003443

- Magnani, L. (2001). Abduction, reason, and science: Processes of discovery and explanation. New York: Kluwer/Plenum.

- Martin, J. J., McCaughtry, N., Hodges-Kulinna, P., & Cothran, D. (2008). The influences of professional development on teachers’ self-efficacy toward educational change. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 13(2), 171–190. doi: 10.1080/17408980701345683

- Martinek, T., & Hellison, D. (2016). Teaching personal and social responsibility: Past, present and future. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 87(5), 9–13. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2016.1157382

- Martinek, T., McLaughlin, D., & Schilling, T. (1999). Project effort: Teaching responsibility beyond the gym. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 70(6), 59–65. doi: 10.1080/07303084.1999.10605954

- Martinek, T., & Ruiz, L. M. (2005). Promoting positive youth development through a values-based sport program. International Journal of Sport Science, 1(1), 1–13.

- Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. Oxford, England: Harpers.

- McAuley, E., Dunkan, T., & Tammen, V. V. (1989). Psychometric properties of the intrinsic motivation inventory in a competitive sport setting: A confirmatory factor analysis. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 60, 48–58. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1989.10607413

- Mosston, M., & Ashworth, S. (2008). Teaching physical education (6th ed.). New York, NY: Benjamin Cummings.

- Pascual, C. B., Escartí, A., Llopis, R., Guiterrez, M., Marin, D., & Wright, P. M. (2011). Implementation fidelity of a program designed to promote personal and social responsibility through physical education: A comparative case study. Research Quarterly in Exercise and Sport, 82(3), 499–511. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2011.10599783

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pozo, P., Grao-Cruces, A., & Pérez-Ordás, R. (2018). Teaching personal and social responsibility model-based programmes in physical education: A systematic review. European Physical Education Review, 24(1), 56–75. doi: 10.1177/1356336X16664749

- Quested, E., & Duda, J. (2011). Perceived autonomy support, motivation regulations and the self-evaluative tendencies of student dancers. Journal of Dance Medicine and Science, 15(1), 3–14.

- Quested, E., Ntoumanis, N., Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C., Hagger, M. S., & Hancox, J. (2017). Evaluating quality of implementation in physical activity interventions based on theories of motivation: Current challenges and future directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 10, 252–269. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2016.1217342

- Rantala, T., & Heikinaro-Johansson, P. (2007). Hellisonin vastuuntuntoisuuden malliosana seitsemännen luokan poikien liikuntatunteja. Liikunta & Tiede, Tutkimusartikkelit, 44(1), 36–44.

- Richer, S. F., & Vallerand, R. J. (1998). Construction et validation de l’échelle du sentiment d’appartenance sociale (ÉSAS) [Construction and validation of the perceived relatedness scale]. European Review of Applied Psychology, 48(2), 129–137.

- Roberts, G. C., Treasure, D. C., & Balague, G. (1998). Achievement goals in sport: The development and validation of the perceptions of success questionnaire. Journal of Sport Sciences, 16, 337–347.

- Romar, J. E., Haag, E., & Dyson, B. (2015). Teachers’ experiences of the TPSR (teaching personal and social responsibility) model in physical education. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 17(3), 202–219.

- Rovio, E., Arvinen-Barrow, M., Weigand, D. A., Eskola, J., & Lintunen, T. (2010). Team building in sport: A narrative review of the program effectiveness, current methods, and theoretical underpinnings. Athletic Insight: The Online Journal of Sport Psychology, 2(2), 147–164.

- Rovio, E., Eskola, J., Gould, D., & Lintunen, T. (2009). Linking theory to practice – Lessons learned in setting specific goals in a junior ice hockey team. Athletic Insight, 11(2), 21–38.

- Schwartz, S. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

- Schwartz, S. (1996). Value priorities and behaviour: Applying a theory of integrated value systems. In C. Seligman, J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), The psychology of values (pp. 1–24). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Treasure, T., & MacRae, K. D. (1998). Minimisation: The platinum standard for trials? Randomisation doesn’t guarantee similarity of groups; minimisation does. BMJ, 317(7155), 362–363. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7155.362

- Viera, A. J., & Bangdiwala, S. I. (2007). Eliminating bias in randomized controlled trials: Importance of allocation concealment and masking. Family Medicine, 39(2), 132–137.

- Vuori, M., Kannas, L., & Tynjälä, J. (2004). Nuorten liikuntaharrastuneisuuden muutoksia 1986–2002. In L. Kannas (Ed.), Koululaisten terveys ja terveyskäyttäytyminen muutoksessa. WHO-koululaistutkimus 20 vuotta (pp. 113–139). Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto.

- Walsh, D. (2012). A TPSR-based kinesiology career club for youth in underserved communities. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14, 55–77.

- Walsh, D., Ozaeta, J., & Wright, P. M. (2010). Transference of responsibility model goals to the school environment: Exploring the impact of a coaching club program. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 15(1), 15–28. doi: 10.1080/17408980802401252

- Wright, P. M. (2012). Offering a TPSR physical activity club to adolescent boys labeled “at risk” in partnership with a community-based youth serving program. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14, 94–114.

- Wright, P. M., & Craig, M. W. (2011). Tool for assessing responsibility-based education (TARE): Instrument development and reliability testing. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 15, 1–16.

- Wright, P. M., Jacobs, J. M., Ressler, J. D., & Jung, J. (2016). Teaching for transformative educational experience in a sport for development program. Sport, Education and Society, 21(4), 531–548. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2016.1142433

- Wright, P. M., & Walsh, D. (2018). Teaching personal and social responsibility. In W. Li, M. Wang, P. Ward, & S. Sutherland (Eds.), Curricular/instructional models for secondary physical education: Theory and practice (pp. 140–208). Beijing, China: Higher Education Publisher.

- Wright, M., Whitley, M., & Sabolboro, G. (2012). Conducting a TPSR program for an underserved girls’ summer camp. Agora for Physical Education and Sport, 14, 5–24.