ABSTRACT

This paper is a comprehensive update of the International Society of Sport Psychology (ISSP) Position Stand on career development and transitions of athletes issued a decade ago (Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler, & Côté, Citation2009, ISSP Position Stand: Career development and transitions of athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7, 395–412.). A need for updating the 2009 Position Stand has grown out of the increasing inconsistency between its popularity and high citation, on the one hand, and its dated content that inadequately reflects the current status of athlete career research and assistance, on the other. During the last decade, sport psychology career scholars worked on structuring the athlete career knowledge and consolidating it into the athlete career (sport psychology) discourse (ACD). The aims of this paper are to: (1) update the decade-long evolution and describe the current structure of the ACD, (2) introduce recent trends in career development and transition research, (3) discuss emerging trends in career assistance, and (4) summarise in a set of postulates the current status and future challenges of the ACD.

Athletes’ career development and transitions: the ISSP Position Stand Revisited

The ISSP Position Stand on career development and transitions of athletes (Stambulova, Alfermann, Statler, & Côté, Citation2009) has played an important role in disseminating athlete career knowledge worldwide and promoting a cultural mindset among career researchers and practitioners. Since the time that original Position Stand was issued, a decade of exponential conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and applied developments in the athlete career knowledge has passed. Increased international communication (e.g., publications, joint research projects) has led to the formation of the athlete career sport psychology discourse (further – the ACD) as a historically constructed and shared body of athlete career knowledge (e.g., basic assumptions, definitions, values) providing career researchers and practitioners with common grounds to understand each other, communicate, and cooperate on different levels (Stambulova & Ryba, Citation2014). There are also a number of national and continental discourses (e.g., dual career discourse in Europe) rallying stakeholders based on shared sociocultural contexts and challenges (Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2019). Keeping these multiple changes in mind, the ISSP has initiated a comprehensive update of the Position Stand on career development and transitions in order to: (1) update the decade-long evolution and describe the current structure of the ACD, (2) introduce recent trends in career development and transition research, (3) discuss emerging trends in career assistance, and (4) summarise in a set of postulates the current status and future challenges of the ACD.

Brief update on the evolution of the ACD

Career research in sport psychology has evolved during the last five decades. Three stages can be identified in its history (see ), reflecting how our understanding of athletes’ careers, transitions, and related applied work has been changing over time (see also Wylleman & Rosier, Citation2016). In the left column of , time periods and major characteristics of the three stages that reflect the evolution of athlete career knowledge can be found. Briefly, the topic evolved from a narrow focus on athletic retirement, reliance on non-sport frameworks, and the establishment of pioneer career assistance programmes or CAPs (the ACD initiation stage) to studying a whole career from beginning to end, within-career transitions, and development of sport-specific frameworks to use both in research and assistance (the ACD development stage), and further – to career research and practice that are guided by a holistic view of athletes’ development (i.e., both sport and non-sport) within relevant environments and cultural contexts (the ACD establishment stage). From the middle column of , the readers can learn about major events that influenced the development of the ACD (e.g., CAPs, books) and how research foci expanded during the years. In the right column of , there is a brief summary of major conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and applied contributions relevant to each stage. We find it useful to briefly trace the ACD evolution before shifting our focus to major developments at the ACD establishment stage during the recent decade.

Table 1. Brief Overview of the Evolution of Athlete Career Discourse in Sport Psychology.

Current structure of the ACD

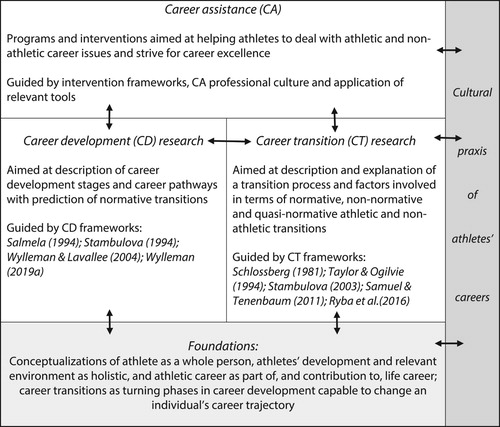

The authors of the 2009 Position Stand considered athlete career research and assistance from international (i.e., as worldwide) and cultural mindset (i.e., as diverse and context-dependent) perspectives. These lines of scholarship were further developed in the book “Athletes’ Careers across Cultures” (Stambulova & Ryba, Citation2013) and the subsequent critical review paper (Stambulova & Ryba, Citation2014) that introduced a new paradigm termed cultural praxis of athletes’ careers. The book played an important role in the international dissemination of athlete career knowledge and has inspired context-driven research and practice in different parts of the world (e.g., Brandăo & Vieira, Citation2013; Huang, Chen, & Qiao, Citation2013; Toyoda, Citation2013). Other major events during the last decade, for example, symposia at all major international congresses, a special issue in Psychology of Sport and Exercise on “Dual career development and transitions” (Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2015a), several recent review papers (e.g., Guidotti, Cortis, & Capranica, Citation2015; Li & Sum, Citation2017; Park, Lavallee, & Tod, Citation2013; Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2019) and international projects (e.g., “Gold in Education and Elite Sport”, GEES, Citation2016), led to consolidation of the body of knowledge that we currently call the ACD (see ).

Figure 1. Current Structure of the ACD (modified from Stambulova, Citation2016, Citation2020).

shows the ACD as constructed of: assumptions that are no longer questioned among career researchers and practitioners (i.e., foundations), two interrelated research areas – career development and career transitions – with an applied – career assistance – part of the ACD built upon, and cultural praxis of athletes’ careers paradigm linking all parts of this construction together (Stambulova, Citation2016; Citation2020).

Foundational definitions and the update of career transitions taxonomy

Major conceptualizations currently established within the ACD include:

Athlete as a whole person (Wylleman, Reints, & De Knop, Citation2013) that is a person who does sport together with other life matters (e.g., studies, work, family);

Athletes’ development as holistic (Wylleman, Citation2019a; Wylleman et al., Citation2013) that means multidimensional with athletic development complemented by psychological, psychosocial, academic-vocational, financial, and legal layers influencing each other in multiple ways, where changes in one layer inevitably lead to changes in the other layers;

Athletes’ environment as holistic (Henriksen et al., Citation2010, Citation2011) that is constituted of interacting micro- and macro- levels as well as athletic and non-athletic domains;

Athletic career as part of, and contribution to, the life career (Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2014) expands the meaning of athletes’ experiences from doing sport for the sake of sport to doing sport for the sake of sport and life; this conceptualisation adds a new facet to two existing definitions of athletic career as a cycle with stages and transitions (Wylleman, Theeboom, & Lavallee, Citation2004) and as an area of self-actualisation with athletes’ multiyear striving for an individual peak in athletic performance (Alfermann & Stambulova, Citation2007);

Career transitions as turning phases in career development involving appraisals of, and coping with, transition demands leading to successful or less successful outcomes and relevant changes in an individual’s career trajectory (Alfermann & Stambulova, Citation2007; Samuel & Tenenbaum, Citation2011; Schlossberg, Citation1981; Stambulova & Samuel, Citationin press).

Career transitions are currently classified based on two criteria: a life domain, where the transition is initiated, and transition predictability. The taxonomy based on the life domain consists of athletic (e.g., the junior-to-senior), non-athletic (e.g., education or family-related), and dual career transitions (i.e., simultaneous transition in sport and education or work; Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2015b). The taxonomy based on the predictability for a long time included two categories: normative (i.e., relatively predictable and derived from the logic of athletes’ development, e.g., athletic retirement) and non-normative (i.e., less or hardly predictable, e.g., injury). Recently, it was recognised that this dualistic (i.e., normative vs. non-normative) taxonomy inadequately reflects all various transitions athletes may have, and a new category of quasi-normative transitions was introduced as transitions predictable for a particular category of athletes (e.g., cultural transitions) with a possibility to prepare for in advance (Schinke, Stambulova, Trepanier, & Oghene, Citation2015; Stambulova, Citation2016; Citation2020).

Career development and career transition research

As identified in , athlete career research consists of two interrelated areas: career development and career transition research. These two areas and relevant frameworks complement each other in a way that the former describes athletes’ career pathways and predicts normative transitions that athletes might have (e.g., between adjacent career stages), whereas the latter describes and explains the transition processes and outcomes as imbedded into a career context and influenced by personal and environmental factors.

Career development frameworks consider athletic career as “a miniature lifespan course” composed of stages and transitions (Salmela, Citation1994; Stambulova, Citation1994; Wylleman et al., Citation2013; Wylleman & Lavallee, Citation2004). The early stage-like frameworks were focused only on athletic career and related stages, yet the developmental model of transitions faced by athletes (Wylleman & Lavallee, Citation2004) marked a shift to the holistic developmental perspective outlining stages in athletic and non-athletic developments. This model was acknowledged in the 2009 ISSP Position Stand, but since that time, it was updated twice and renamed into a holistic athletic career model (Wylleman, Citation2019a; Wylleman & Rosier, Citation2016) with six interrelated layers: athletic, psychological, psychosocial, academic-vocational, financial, and legal. The holistic athletic career model serves as a cornerstone for career studies guiding researchers to take the holistic developmental perspective. This stage-like model and others make an impression that athletes’ careers are linear, but research does not confirm this assumption. Therefore, stage-like models should be taken with caution, keeping in mind that careers are more diverse and less linear than these models suggest. One way to escape from the linear type of thinking is to use a multiple-metaphor career framework (Inkson, Citation2006) to describe careers using any of nine complementing metaphors, namely inheritance, cycle, journey, action, fit, relationship, role, resource, and story (see more in Stambulova, Citation2010). Another way is to examine individual career and/or transition pathways by facilitating athletes’ explorations of identity and career construction through narratives (e.g., Bonhomme, Seanor, Schinke, & Stambulova, Citation2018; Carless & Douglas, Citation2012; Ronkainen & Ryba, Citation2019).

Career transition frameworks (Schlossberg, Citation1981; Stambulova, Citation2003; Taylor & Ogilvie, Citation1994) focus on the transition processes, and how various factors (e.g., demands, resources, barriers, coping strategies) interplay to constitute the different transition pathways and outcomes (e.g., successful transition, crisis-transition, unsuccessful transition). Since the 2009 Position Stand was issued, three new frameworks have been created, namely, the scheme of change for sport psychology practice (SCSPP, Samuel & Tenenbaum, Citation2011), the integrated career change and transition framework (ICCT, Samuel, Stambulova, & Ashkenasi, Citation2019; Stambulova & Samuel, Citationin press), and the cultural transition model (Ryba, Stambulova, & Ronkainen, Citation2016; Citationin press). The SCSPP framework focuses on career change events of a transitional nature (e.g., selection to, or deselection from, a team) and considers the transition process through the cognitive–behavioral lens with pathways reflecting a sequence of the change event appraisals, decisions, and related coping behaviours. The ICCT framework enriched the SCSPP by adding components (demands, resources, barriers) of the athletic career transition model (Stambulova, Citation2003) that led to a more comprehensive description of the transition process with a number of transition pathways. The cultural transition model (Ryba, Stambulova et al., Citation2016) outlines the three-phase structure of the transition and underlying mechanisms of cultural adaptation (more about this model is forthcoming).

Career assistance

In , both areas of career research are shown to be the basis for career assistance, which is a professional discourse in applied sport psychology aimed at helping athletes with career issues in and outside of sport (Stambulova, Citation2010). Career assistance covers various intervention types and services provided by sport psychology practitioners (SPPs) or included into Career Assistance Programs (CAPs). As mentioned in , over 60 CAPs have been launched in different countries (Stambulova & Ryba, Citation2013, Citation2014). Recently, Torregrossa, Regüela, and Mateos (Citationin press) provided a taxonomy of CAPs consisting of holistic CAPs for elite athletes focusing on sport, education, work, and personal growth, sport specific CAPs for professional athletes helping with business, legal, financial and mental health issues, and dual career CAPs for student-athletes facilitating their sport-study combination.

To integrate and structure the existing knowledge on applied work with athletes in career transitions, Stambulova (Citation2012) proposed the assistance in career transitions framework as a set of guidelines on how to plan a career transition intervention. By adopting this framework, SPPs are encouraged to collect holistic information about a client (i.e., as a person and an athlete, other-than-athlete roles and key relationships, as well as near past, present and perceived future). An additional recommendation is to take into account the client’s athletic and non-athletic contexts when formulating the intervention goals. The framework also contains a taxonomy of career interventions, such as career planning, lifestyle management, life skills training, identity development, cultural adaptation, crisis-coping educational, and clinical interventions – all situated within a continuum between preventive/educational and crisis/ coping perspectives (see also Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2014).

Cultural praxis of athletes’ careers

depicts the key conceptual and applied frameworks that contributed to the development of a new paradigm termed cultural praxis of athletes’ careers (Stambulova & Ryba, Citation2013, Citation2014). Embracing the whole person and the whole environment perspectives of the ACD, Stambulova and Ryba embedded their theorising in the cultural praxis heuristic (Ryba, Citation2017; Ryba & Wright, Citation2005; Ryba, Schinke, & Tenenbaum, Citation2010) to contextualise athlete subjectivity in lived culture and to mend the gap between theory and applied work. The cultural praxis of athletes’ careers navigates career researchers and practitioners to: (a) reflexive positioning of career projects in particular sociocultural contexts, (b) taking the holistic perspectives on athlete career and environment, (c) exploring diversity of career pathways and their construction within and across international borders, (d) engaging culturally sensitive methodologies, and (e) developing transnational networks and collaborative projects by career researchers and practitioners.

Emerged trends in athlete career research

Below we overview major recent trends in career development and transition research. These trends are informed by the ACD foundations, frameworks, and basic tenets of the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers.

Dual career research

The term “dual career” (DC), defined as “a career with foci on sport and studies or work” (Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2015b, p.1), was established during the last decade and relevant research has been growing worldwide. Researchers prioritise exploring DC in sport and studies pathway(s) emphasising DC athletes’ challenges (e.g., investing into sport and studies while trying to maintain social and private life), and short- and long-term benefits (e.g., broader identity and social network, developing employability competencies) and potential costs (e.g., a risk for burnout). Although many DC studies have recently been conducted in North America (Blodgett & Schinke, Citation2015; Yukhymenko-Lescroart, Citation2018), Australia and New Zealand (Cosh & Tully, Citation2015; Ryan, Thorpe, & Pope, Citation2017), Asia and Africa (Sum et al., Citation2017; Tshube & Feltz, Citation2015; Zhang, Chin, & Reekie, Citation2019), European DC research supported by the European DC Guidelines (European Commission, Citation2012) has been dominating and flourishing.

Two major state-of-the art reviews of the European DC research (Guidotti et al., Citation2015; Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2019) embraced in total 90+ publications in English language for the 2007–2018 period. In short, DC pathways of European athletes are diverse because DC contexts are organised differently in different countries, encouraging researchers to be context-sensitive (Aquilina & Henry, Citation2010). Researchers focus on several DC transitions (e.g., to an elite sport school, to a university, to the post-sport and/or post-academic life) with relevant demands, resources, barriers, and coping strategies addressed from the holistic developmental perspective (e.g., Brown et al., Citation2015; Debois, Ledon, & Wylleman, Citation2015; Stambulova, Engström, Franck, Linnér, & Lindahl, Citation2015; Torregrosa, Ramis, Pallarés, Azócar, & Selva, Citation2015). DC athletes usually recognise that it is impossible to invest fully and continuously in both sport and education. With the competing demands, they have to plan shifts in prioritising and search for an optimal balance between the two and also their social and private life (Brown et al., Citation2015). Usually after school graduation, athletes select one of the three pathways termed “linear” (focus on sport), “convergent” (prioritising sport but maintain studies) and “parallel” (sport and studies are equally important) (Torregrossa et al., Citationin press). These different pathways are specified in the research on student-athletes’ motivation, identity, health, lifestyle, and wellbeing (e.g., Ryba, Aunola, et al., Citation2016) attracting attention to various types of DC athletes in terms of their motivational patterns (Aunola, Selänne, Selänne, & Ryba, Citation2018), self-identity structure (Lupo et al., Citation2017), burnout symptoms (Sorkkila, Ryba, Selänne, & Aunola, Citation2018), and career construction styles (Ryba, Stambulova, Selänne, Aunola, & Nurmi, Citation2017). Discussing factors of DC success, researchers emphasise athletes’ DC competencies acting as their personal resources and DC support as available external resources. The DC competencies studied within the ERASMUS + Sport project “Gold in Education and Elite Sport” (GEES, Citation2016) were integrated into four clusters, such as DC management, career planning, mental toughness, social intelligence and adaptability (De Brandt et al., Citation2018), and helping athletes to develop DC competencies was shown to be a major target for the DC support. In other words, athletes are seen as active agents in constructing their careers, and DC support services as facilitating this process (Knight, Harwood, & Sellars, Citation2018; López de Subijana, Barriopedro, & Conde, Citation2015).

Ecological career/talent development research

Career and talent development research overlaps in investigating the development of young athletes who aspire for successful junior-to-senior transition and continuation in elite and professional sports. From an ecological perspective, career/talent development can be seen as the progressive mutual accommodation that takes place between an aspiring athlete and a whole environment. The authors of the holistic ecological approach (HEA) in talent development (Henriksen et al., Citation2010; Henriksen & Stambulova, Citation2017) propose a shift in research attention from the individual athletes to the athletic talent development environments (ATDEs) and suggests analysing the ATDEs using two complimentary working models.

First, in the athletic talent development environment (ATDE) working model the components and structure of the environment are described situating athletes at the centre of the model, and other ATDE’s components structured into two levels (micro- and macro-) and two domains (athletic and non-athletic). The micro-level refers to the environment where prospect athletes spend a major part of their daily life. The macro-level refers to social settings, which affect but do not contain the athletes. The athletic domain covers the part of the athletes’ environment that is directly related to sport, whereas the non-athletic domain presents all the other spheres of athletes’ lives. The outer layer of the model represents the past, present and future of the ATDE, emphasising that athletes’ development is aligned with the development of environment. Second, the environment success factors (ESF) working model takes as a starting point the environment preconditions (e.g., human, material, and financial), and illustrates how the daily processes (e.g., training, camps, competitions) have three outcomes: athletes’ individual development and achievements, team/group achievements, and organisational development and culture. Organisational culture is central to the ESF model and consists of cultural artefacts, espoused values, and basic assumptions, which are underlying reasons for actions that are no longer questioned (Schein, Citation1990). The model illustrates that the ATDE’s success is a result of the interplay between all the ESF’s components (i.e., preconditions, processes, and culture).

During the last decade, researchers used the HEA models to conduct contemporary and in-depth case studies of successful ATDEs selected based of their ability to help young talented athletes with the junior-to-senior transition. These studies included different sports (e.g., sailing, track and field, swimming, cycling, karate, soccer, handball and trampoline) and countries (e.g., Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Netherlands, Canada) (e.g., Henriksen et al., Citation2010, Citation2011; Larsen, Alfermann, Henriksen, & Christensen, Citation2013; Seanor, Schinke, Stambulova, Ross, & Kpazai, Citation2017). The findings from the studies of these successful ATDEs have been contrasted with a study of a less successful golf environment that, despite resources, never succeeded in their goal of developing elite level athletes (Henriksen, Larsen, & Christensen, Citation2014). Cross-case analyses within the HEA revealed the ATDEs are the most successful in supporting athletes when: the efforts of different parts of the environment (e.g., school, club coaches, national team coaches) are integrated rather than fragmented; they focus on the athletes’ long-term development rather than early success; they include a strong network of stakeholders (e.g., parents) supporting the athletes’ sporting goals; they provide opportunities to train with role models who are willing to pass on their knowledge; and they are based around a supportive training community and characterised by a coherent organisational culture (Henriksen & Stambulova, Citation2017). All these characteristics ensure that the ATDEs nourish athletes’ development and mental health (Henriksen et al., Citation2019). The HEA driven research has recently been expanded by studying dual career development environments within the European project “Ecology of Dual Career” (ECO-DC, Citation2018; Henriksen, Storm, Kuettel, Linnér, & Stambulova, Citation2020).

Transnational athlete careers and cultural transition research

This line of career research was summarised in the recent ISSP Position Stand on transnationalism, mobility, and acculturation in and through sport (Ryba, Schinke, Stambulova, & Elbe, Citation2018). The authors considered transnational athletic careers as associated with highly skilled athletic migrants and produced in migratory practices and processes that cross the borders of one or more nation-states. For example, studies with migrant athletes in the Nordic region (Ryba, Ronkainen, & Selänne, Citation2015; Ryba, Stambulova, Ronkainen, Bundgaard, & Selänne, Citation2015) revealed that the athletes’ career trajectories, lived experience, and psychosocial functioning were closely linked to career discourse practices, professional opportunities, and social policy about migrants at their countries of origin and temporal settlement. Similarly research conducted in the multiple sites further indicated that the participants’ main motivation for migration was to advance their athletic careers, yet many also considered education and lifestyle opportunities in the receiving societies important (e.g., Ely & Ronkainen, Citation2019; Schinke et al., Citation2016).

With transnational migration being fairly common in elite development pathway, the need to understand the cultural transition influences on careers has become relevant for the ACD. Researchers started to identify specific stressors and challenges of migrant athletes, such as cultural, linguistic, and structural barriers of acculturation (for reviews see Oghene, Schinke, Middleton, & Ryba, Citation2017; Schinke, Blodgett, Ryba, Kao, & Middleton, Citation2019). The sport-related challenges of ‘fitting in’ the training routines and playing style of the new team were shown to be central to migrant athletes’ experience (e.g., Meisterjahn & Wrisberg, Citation2013; Richardson, Littlewood, Nesti, & Benstead, Citation2012; Ryba et al., Citation2016; Schinke et al., Citation2016). In addition to sport-related issues, scholars described broader challenges, for example, learning new language and cultural norms, or adjusting to a different diet (Agergaard & Ryba, Citation2014; Kontos & Arguello, Citation2010; Ryba, Stambulova, et al., Citation2015). The experience of loneliness was also a common finding, as well as the important role of family, friends, and mentors (Light, Evans, & Lavallee, Citation2017; Richardson et al., Citation2012; Ronkainen, Khomutova, & Ryba, Citation2019; Ryba, Haapanen, Mosek, & Ng, Citation2012). The acculturative sporting environments were suggested to mediate migrants’ adaptation pathways. Some athletes narrated their country of settlement in a positive tone, whereas others reflected on the complexity of their acculturation experiences, inequality of opportunities and the difficulty of developing a sense of belonging which could not be established by being an official member of the team alone (Blodgett & Schinke, Citation2015; Ronkainen, Ryba, & Tod, Citation2019; Ryba et al., Citation2016; Schinke, Bonhomme, McGannon, & Cummings, Citation2012). The scholars adopting a transnational approach have argued that transnational athletes’ migration experiences may differ from those of settled immigrants: that is, all migrants participate in cross-border activities, yet a settlement intent is likely to mould psychological openness to further mobilities if the opportunity (or need) arises.

In the cultural transition model, Ryba, Stambulova, et al. (Citation2016, Citationin press) theorised cultural transition as a social psychological process consisting of three phases: pre-transition, acute cultural adaptation, and sociocultural adaptation. The pre-transition refers to activation of psychological mobility which typically involves various ways of planning for future relocation and psychological disengagement from the athletes’ current origin. The acute cultural adaptation refers to the time shortly after the relocation when athletes learn to fit into the team and gradually develop cultural capital valued in the broader society. The socio-cultural adaptation occurs when athletes establish a longer-term settlement. Each transitional phase presents developmental tasks or challenges that shape the acculturation pathways. It was also theorised that social repositioning, negotiation of cultural practices and meaning reconstruction are the cultural transition underlying mechanisms, manifested within a range of culturally patterned behaviours and discursive practices. Although the cultural transition is seen as open-ended, it is believed to have a symbolic exit characterised by migrants’ optimal functioning in novel environments at the destination (Ryba et al., Citation2018).

New developments in athletic retirement and the junior-to-senior transition research

Research on athletic retirement and the junior-to-senior transition (JST) was carefully addressed in Stambulova et al. (Citation2009), so we focus on updating this knowledge with new perspectives in studying these normative transitions during the last decade.

Athletic retirement

Park et al. (Citation2013) summarised findings of athletic retirement research based on 126 studies published in English between 1968 and the end of 2010. In their summary the authors revealed that quality of the post-sport career adaptation is influenced by an interplay of various athletes’ personal and developmental factors (e.g., athletic identity, educational and financial status) and facilitated by pre-retirement planning, searching for a new career/interest, psychosocial and professional support. A major new development in athletic retirement research is to consider a temporal (i.e., phase-like) structure of this transition that might last from several months to several years. One of the first attempts was made by Reints (Citation2011) in a study of retired Flemish elite athletes, in which four phases were identified and described in terms of athletes’ adjustment on athletic, psychological, psychosocial, vocational, financial, and physical levels of their development. The phases were: planning for athletic retirement, career termination, start of the post-athletic career, and reintegration into society. Quality of adjustment varied among athletes, but the tendency was that “the quality of the post-athletic career rises as time goes by” (p. 96) with the highest perceived adjustment quality at the fourth phase. Park, Tod, and Lavallee (Citation2012) applied the transtheoretical model (Prochaska & DiClemente, Citation2005) to analyse Korean elite tennis players’ decision making throughout the pre-contemplation, contemplation, preparation, preparation moratorium, and action phases of the retirement transition. Across the five phases, athletes’ decisions to retire were initiated, weighted against an alternative to continue in sport, formulated, and reformulated over time as a function of changes in their athletic identity, perceived readiness for retirement, and coping strategies implemented. Recently, Chroni, Pettersen, and Dieffenbach (Citation2019) used narrative interviews data to create the empirical model “Athlete-to-coach transition in Norwegian winter sports” and describe three transition phases – the career shift, re-identification, and professional development – with demands, barriers, and resources relevant to each phase.

Phase-like structure of athletic retirement covering pre- and post-termination phases might be useful for providing more nuanced support to retiring/retired athletes. In the recent ERASMUS + Sport Project “Be a Winner In elite Sport and Employment before and after athletic Retirement” (B-WISER, Citation2018), athletes’ employability challenges, barriers, and competencies were considered in relation to the three phases: still active in sport, just retired, and in the first employment after athletic career termination. Transferable competencies developed in sport (e.g., life management, social and communication, emotional awareness, career planning) were revealed as athletes’ major resources for successful post-sport career employment and adaptation (B-WISER, Citation2018; Wylleman & De Brandt, Citation2019).

The junior-to-senior transition

During the last decade the JST was investigated from the holistic developmental (see Wylleman & Rosier, Citation2016 for an overview) and ecological perspectives (see Henriksen & Stambulova, Citation2017 for an overview). In the former, the JST demands (e.g., increased intensity of training and higher level of competitions) and coping (e.g., developing own competencies and using available support) were considered as interrelated with the changes in athletes’ psychological, psychosocial, academic-vocational and financial developments (e.g., identity formation, new social network, beginning of high education, increased expenses). In the latter, the focus was on the ATDEs that facilitate (or debilitate) the JST. Recently, in a study of Swedish athletes, Franck (Citation2018) created an integrated framework that combined the holistic athletic career model (Wylleman et al., Citation2013), the athletic career transition model (Stambulova, Citation2003) and the ecological perspective (Henriksen et al., Citation2010). Franck’s project demonstrated a dynamic nature of the JST process with more (or less) adaptive personal profiles and various (non-linear) patterns during the two-and-a-half-year longitude.

A series of studies in Swedish ice-hockey focused on the JST temporal structure. In the first study (Stambulova, Pehrson, & Olsson, Citation2017), interviews with the players situated at the different periods of their JST were used to create the empirical model “Phases in the JST of Swedish ice hockey players” describing the JST as having four phases – preparation, orientation, adaptation, and stabilization – with specific demands, resources, barriers, coping strategies and outcomes at each phase. In the second study (Pehrson, Stambulova, & Olsson, Citation2017) the empirical model was validated by means of collecting critical reflections of professional players and coaches. The validated version is seen as a contextualised framework useful for further research and applied work in Swedish ice hockey, but it can also serve as an example for developing frameworks specific for other sporting and sociocultural contexts.

New transitions in focus

During the last decade three new transitions attracted attention of career researchers, including the Olympic Games transition, the transition to residential high-performance centre, and the injury transition. The first two are quasi-normative transitions relevant only to elite athletes, and the third one is a (rather common) non-normative transition.

The Olympic Games transition

Participation in Olympic Games is a turning point in athletes’ athletic and even life careers (e.g., Samuel, Tenenbaum, & Bar-Mecher, Citation2016). But career researchers just recently began to consider Olympic Games from the holistic developmental perspective as a transition having several phases (Schinke et al., Citation2015; Stambulova, Stambulov, & Johnson, Citation2012; Wylleman, Reints, & Van Aken, Citation2012). Wylleman and colleagues used interviews and athletes’ self-reports to describe changes in athletic, psychological, psychosocial and academic/vocational development experienced by four Belgian Olympians prior to the Olympic Games-2008, during the Games, and after the Games phases. In regard of each phase the participants reported changes covering all four developmental layers that allowed the authors to promote the holistic developmental perspective as important in studying Olympic athletes. Stambulova and colleagues identified five phases within the athletes’ Olympic cycle based on the applied experiences of working with Russian athletes in complex coordination sports – basic preparation, selection for the Olympic team, the Olympic season, the Games, and post the Games – and described typical psychological issues experienced by athletes at each phase. Schinke and colleagues used applied experiences of working with the Canadian Olympic boxing team to identify athletes’ major challenges and support needs in the six “meta-transitions” within the Olympic cycle (see more further in the paper).

The transition to residential high-performance center

Among the ways to facilitate elite athletes’ preparation for Olympic Games and other top-level competitions many countries have developed residential high-performance centres providing athletes with quality conditions for training, living, and (possibly) for combining sport with studies or work. These “resource environments” with a number of support programmes are also very demanding for athletes and require time and efforts to adjust. A pioneering project on the transition to the Colorado Springs Olympic Training Center (CSOTC) was focused on how internal and external resources contributed to six resident-athletes’ successful transition defined as “an adaptation to the CSOTC environment both initially (first weeks) and over time (months and years), leading to successful performance internationally” (Poczwardowski, Diehl, O’Neil, Cote, & Haberl, Citation2014, p. 36). Combining qualitative (in-depth interviews) and quantitative (psychological profiling) data, the authors concluded that optimism, sport-life balance, and transition/performance support were key factors for the successful adaptation at the CSOTC. Recently, Diehl, Poczwardowski, Stambulova, O’Neil, and Haberl (Citation2019) undertook re-analysis of the qualitative data collected in the aforementioned study and created the empirical model of the transition to the CSOTC. The model presents the successful transition process as involving the dynamic interactions between the resident-athletes and the CSOTC staff during the four phases – preparation, assimilation, adaptation, and thriving – with related challenges, barriers, resources, strategies, and outcomes. The authors concluded that further development of this research line (including less successful cases) might help to improve psychological support services at such centres.

Injury as a transition

Research on athletes’ injury prevention and rehabilitation is an established discourse in sport psychology (for an overview see Ivarsson & Johnson, Citation2020) but it has only emerging connections with the ACD. Samuel et al. (Citation2015) considered an injury as a career change event in the mixed-methods study of six Israeli elite athletes. The authors identified three phases in the change process, emphasising athletes’ pre-injury career motivation (phase one), emotional disturbance and decision making (phase two), and implementation of decision to change (phase three) followed by recommendations for practitioners working with injured athletes. Ivarsson, Stambulova, and Johnson (Citation2016) explored career and injury narratives of an elite handball player and contributed to career development research by showing that an injury can (in the long-term) be positive (e.g., increased physical strength due to rehabilitation programme) or negative (e.g., causing premature termination) career event. This project also contributed to career transition research presenting the four-phase empirical framework of the injury as a transition process beginning with pre-injury phase (with a focus on factors contributing into the injury), and followed by injury and first reaction, diagnosis and treatment, and rehabilitation and consequences phases with specific demands, barriers, resources, coping strategies and outcomes at each of the last three phases. Such studies inform athlete psychological support by illuminating the injury-risk factors and, once injury occurred, help to anticipate the demands of each transition phase.

Emerging trends in career assistance

In this (applied) section we shift focus to emerging trends in career assistance and consider how these trends are informed by recently developed lines in career research.

Towards athlete career excellence

The analysis of the emerged trends in athlete career research showed enriching overlaps between the ACD and other sport psychology discourses, including cultural sport psychology, talent development, performance enhancement, and psychology of athletic injury. A new link is currently forming with the emerging mental health discourse, which can be important for defining an agenda for future career research and assistance. For example, the ISSP Position Stand on athletes’ mental health, performance, and development (Schinke, Stambulova, Si, & Moore, Citation2017) and the consensus statement on improving the mental health of high-performance athletes (Henriksen et al., Citation2019) emphasise mental health as a resource throughout athlete career development but also direct us to consider it among the career development outcomes. Re-conceptualizing mental health from being seen as only a resource to being also an outcome of career development leads us to considering health dimension as an essential part of athlete career excellence. Recently, the concept of athlete career excellence was introduced (Stambulova, Citation2020) to complement the established concepts of performance and personal excellence (Miller & Kerr, Citation2002), and it is defined as an athlete’s ability to sustain a healthy, successful, and long-lasting career in sport and life. In this definition, healthy means high resourcefulness and adaptability (i.e., coping with career demands while adding to the individual resources), successful means athletes’ striving for achieving meaningful goals in sport and life while satisfying basic psychological needs and maintaining health and wellbeing, and long-lasting means sustainability and longevity in sport and life. Career excellence is not a destination to reach, but more a journey to, or process of, striving for it, in which athletes might need support. Helping athletes to strive for career excellence can be seen as a target for career assistance. Contributions of some emerging and evidence-based trends in career assistance into this target are presented next.

Dual career support and relevant competencies

Providing support to student-athletes is an emerging trend in Europe stimulated by the European DC Guidelines and supported by national DC research and European DC projects (e.g., GEES, Citation2016). Previous and more established experiences of supporting American DC athletes (e.g., the NCCA Student-Athlete Program known also as the CHAMPS/Life Skills Program since 1994; Petitpas, Van Raalte, & Brewer, Citation2013) were helpful for European countries only to a certain degree; in contrast to the American DC context with sport as school-based, educational and sport settings in Europe are separated requiring a search for new solutions. In the American context, DC support providers are employees of the universities with determined status and tasks, whereas in Europe a DC support provider has been defined as “a professional consultant related to an educational institution and/or an elite sport organisation – or certified by one of those – that provide support to elite athletes in view of optimising their DC” (Wylleman, De Brandt, & Defruyt, Citation2017, p. 108). Empowering DC athletes by helping them to develop DC competencies (e.g., career planning, DC management, emotional awareness), and thus become more resourceful and autonomous (as time goes by) is formulated as a major task of DC support providers (Wylleman et al., Citation2017). Education and training of DC support providers grounded in the clusters of their professional competencies (advocacy and cooperation, reflection and self-management, awareness of DC athletes’ environment, organisation, empowerment and relationship competencies) identified within the GEES project (Defruyt et al., Citation2019) are on the current agenda of DC stakeholders in Europe (Defruyt, Citation2019; Torregrossa et al., Citationin press).

Supporting athletes in cultural transitions

Research indicates that cognitively and emotionally, the acculturation process begins before athletes’ geographical relocation (i.e., in the pre-transition), therefore, efficient preparation by means of networking, information gathering, and emotional support are key to minimising possible culture shock upon arrival. In the acute cultural adaptation phase, athletes are likely to be overwhelmed by changes and often look back at the past/home and compare with the present/new environment. SPPs are encouraged to facilitate newcomers’ orientation in the resources at the destination, their positioning in the receiving sporting site, and the reflections and meaning negotiation with the focus on sport performance and well-being. In the sociocultural adaptation phase athletes look more at the present as they search for relatedness and social support within the broader networks (other than sport), and SPPs should augment integration by bridging their past, present, and future in identity work (see more in Ryba et al., Citation2018; Ryba, Stambulova, & Ronkainen, Citationin press; Schinke et al., Citation2019).

Principles of career assistance (e.g., the holistic developmental and ecological approaches, the individual and empowerment approaches; see more Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2014) complemented by postulates of context-driven practice (e.g., situating the clients within their contexts, consultants’ immersing in the clients’ contexts, the client’s and the consultant’s reflections; see more in Stambulova & Schinke, Citation2017) might help SPPs to navigate how they can facilitate athletes’ meaningful transition experiences to achieve optimal functioning in the novel environment (Ryba et al., Citation2018). To increase athletes’ resourcefulness and adaptability, an overarching shared acculturation approach is recommended with a set of strategies fostering a mutual interest and multicultural practices (e.g., sharing customs, meals, language learning, work ethics) of both newcomers and the hosts (Schinke & McGannon, Citation2014).

Working with athletes’ environment based on the holistic ecological approach (HEA)

The HEA would lead us to consider the athletic career as a journey through various environments. In European soccer, for example, a successful player will often encounter environments such as the local club, a talent academy, a professional club’s second team (e.g., under the age of 23) and the first team. All these environments vary in structure, resources, processes and culture. For example, a talent academy is likely to benefit from a close collaboration with parents and an organisational culture that values long-term development focus, sharing knowledge, and room for unstructured play, whereas some elite sport teams may benefit from a close collaboration with the federation and an organisational culture characterised by a here-and-now performance focus and a clear hierarchy (Henriksen, Storm, & Larsen, Citation2018). Therefore, in preparing athletes for the key transitions, the SPPs are encouraged to adopt the HEA and supplement their focus on athletes’ individual development with helping them to understand the inner workings of the environments they transition from and to. By investigating the structure and culture of both sending and receiving environments, SPPs can also assist these environments to smooth the athlete’s transition.

Another implication of the HEA is optimising athletic environments by improving their structure and culture (Larsen et al., Citation2013). In terms of the structure, research has shown that environments are most successful in supporting athletes when the efforts of different parts of the environment (e.g., school, club coaches, parents) are integrated, and when there is a recognition of the need for coherent messages and optimal support from different stakeholders (Harwood & Knight, Citation2015; Henriksen & Stambulova, Citation2017; Knight, Citation2016; Martindale & Mortimer, Citation2011). The structural interventions at the micro-level might facilitate, for example, communication between club, coaches, and parents, or working relationship between youth and senior departments within the club. It is also possible to optimise inter-level collaboration, for example, within an “organizational triangle” involving a local club, the municipality and the national sport federation to improve functioning of the local club (Mathorne, Henriksen, & Stambulova, Citation2019). Helping environments to build and maintain coherent organisational cultures facilitates athletes’ transition into and their functioning in the environments (e.g., Wagstaff & Burton-Wylie, Citation2018). Henriksen (Citation2015) shared how, adopting the HEA, it was possible for a SPP to optimise a national team culture, which improved the thriving and performance of athletes and coaches. Management-led culture change in Olympic and professional sport teams has similarly been associated with successful outcomes (Cruickshank, Collins, & Minten, Citation2015).

Career-long psychological support services and athlete career excellence

Athletes’ careers evolve through a number of stages and transitions in different life domains including them moving between related environments (e.g., in sport, studies, work, family) and being part of related cultures. Athletes strive for performance excellence and try to maintain an optimal balance between sport and other spheres of life, and the complexity of this process leads us to promote the idea of career-long psychological support services helping athletes to strive for their career excellence. Challenges faced by athletes in youth sport, elite sport, professional sport, and upon retirement combined with challenges in their psychological, psychosocial, academic/vocational, financial and legal developments through childhood, youth, and various periods of adulthood, reflect the dynamics of athletes’ needs in terms of content and delivery of psychological support services. Henriksen, Storm, Stambulova, Ryrdol, and Larsen (Citation2018) interviewed 12 expert SPPs about their successful and less successful interventions with competitive youth and senior elite athletes and found some shared and also specific features in terms of the content and delivery of the interventions. The shared features of successful interventions included: a thorough assessment of athletes’ needs, a whole person approach, following the athletes over time and across contexts, involving significant others, and monitoring effectiveness of the intervention. The specific features revealed an evolvement of the services from using adapted curriculum on mental and life skills and focusing on developmental outcomes before performance in working with youth athletes to implementing a tailored approach in addressing both development and performance as well as existential and motivational issues in senior elite athletes.

Career development and performance are related to each other, and big competitions, especially Olympic Games, are major highlights of an elite career. Conceptualization of Olympic Games as career transitions opened an opportunity to work with athletes during the Olympic cycle using career development and transition frameworks. For example, Schinke et al. (Citation2015) identified six “meta-transitions” within the Olympic cycle of Canadian male boxers involved in the “Own the Podium” (OTP) support programme: entering the OTP, entering major international tournaments, Olympic qualification, focused preparation, participation in the Games, and post-Games. For each of these meta-transitions, athletes’ demands were proactively articulated (e.g., orientation in the OTP resources, preparing for Olympic qualification, orientation in the Olympic context, performing the personal best, planning for the future) and related psychological services planned and implemented by the first author (Schinke et al., Citation2015). Wylleman and Rosier (Citation2016) shared experiences of applying the holistic athletic career model in addressing Olympic athletes’ needs in athletic, psychological, psychosocial and academic/vocational development at different phases of the Olympic cycle. Further, Wylleman (Citation2019b) pointed out that a holistic perspective should be adopted by all the members of integrated expert support teams for Olympic athletes facilitating their interdisciplinary and intradisciplinary collaboration. For interdisciplinary collaboration, SPPs should have basic competencies in other domains of expertise (e.g., sport medicine, nutrition) to be able to cooperate with these experts on athletes’ issues. Intradisciplinary collaboration refers to a competency-based complementarity among psychology experts (e.g., sport educational, health, clinical) to best meet clients’ needs. The authors of the consensus statement on improving athletes’ mental health (Henriksen et al., Citation2019) emphasised that mental health is everybody’s business but should be somebody’s main responsibility and suggested a mental health officer (trained in clinical psychology) as the new addition to athletes’ support staff with a set of monitoring, educational, consulting, networking, and referring functions (e.g., see the Australian Soccer League information at: https://www.afl.com.au/news/2019-08-05/afl-makes-two-new-specialist-appointments-in-mental-health-space).

Developing the career long psychological support services is a solution in helping athletes to strive for their career excellence. Although we can expect that there will be shared features in content and organisation of such services in different sports and sociocultural contexts, a contextualised approach (i.e., grounded in analysis of career development in a specific athletic population) might be more nuanced and beneficial (see Ryba, Stambulova, Si, & Schinke, Citation2013). For example, based on a recent study of career development of Swedish handball players (Ekengren, Stambulova, Johnson, & Carlsson, Citation2018) and the first author’s over a decade applied work in Swedish handball, the authors created an applied framework termed “Career-long psychological support services in Swedish handball”. This framework is aimed at navigating stakeholders about: where (contexts), when (career stages and age markers related to Swedish handball players), what (players’ athletic and non-athletic needs throughout the career stages), who (SPPs, significant others), how (individual and group forms of psychological services), and why (professional philosophy) of the psychological support (Ekengren, Stambulova, & Johnson, Citation2019). This pioneer attempt might serve as an example guiding SPPs to create analogous frameworks in relation to other contexts. At the same time, implementation of such a framework might face several challenges, for example, how to achieve a proper continuity in the psychological services when players move from one environment to the next, how different stakeholders involved should collaborate to integrate their efforts in transforming the career-long psychological support services from an idea to reality. In facilitating athletes’ striving for career excellence, SPPs are encouraged to help them step-by-step in their careers to: better understand themselves and the sport/life contexts involved, make optimal choices, develop resources (e.g., performance and life skills), reduce unnecessary stress, and develop a proactive mindset to bridge their past, present and future in sport and beyond.

Postulates

Below, we summarise major new developments and future challenges within the athlete career (sport psychology) discourse (ACD) in the form of ten postulates.

The intensified interactions between various stakeholders worldwide (e.g., researchers, practitioners, policy makers) have led to the construction of the ACD. Its current structure consists of foundations (e.g., athlete as a whole person, athletes’ development and environment as holistic), career development and career transition research areas, and career assistance – all permeated by the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers paradigm. Career researchers and practitioners are recommended to position their projects (or client’s issues) within the ACD and, thus, to benefit from considering their topics in multiple associations with the various parts of the ACD.

At the heart of the latest developments in the ACD is the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers that directs attention to the diversity of athletes, career pathways, transitions, and athletic and non-athletic contexts of career development. Recent career projects are holistic and context-sensitive, challenge a view of athletes’ development as linear, and more often (than before) focus on marginalised athletic populations. Specifically, the developments in the ACD include: (a) an update of the transition taxonomy (e.g., quasi-normative transitions); (b) the development of HEA; (c) an update of the holistic athletic career model and development of new transition frameworks (e.g., SCSPP, the cultural transition model, and ICCT); (d) emergent research on career change events, athletes’ transnational careers, and several new transitions (e.g., cultural transitions); and (e) the development of contextualised and phase-like empirical frameworks of key transitions. The ISSP encourages researchers and practitioners to critically reflect on these innovations to adopt them in their work, and highlights that special efforts are required to transform this new knowledge into a form that allows athletes, coaches, parents, and other stakeholders to understand and benefit from it.

Many athletes worldwide are engaged in dual careers in sport and education or work. Research on student-athletes revealed multiple demands they have to meet to successfully initiate and maintain a DC. Inability to cope with these demands leads to elevated stress, compromised mental health, burnout, and dropout. Key factors in successful coping are the athletes’ personal resources (e.g., DC competencies) and the conditions/support provided by the DCDEs. Therefore, athletes are recommended to utilise available support to develop DC competencies and to search for an optimal balance between sport, studies/work, and private life. The ISSP pays attention to the specific set of competencies (e.g., empowerment, cooperation, relationship) that DC support providers should have to be able to deliver high quality services and help athletes to experience DC benefits.

From the ecological perspective, an athlete’s career is a journey through sport and non-sport environments that differ in purpose, structure, and culture. These environments can act as resources or barriers for athletes’ career development. The HEA research revealed that environments successfully supporting athletes’ careers are characterised by integrated efforts from different parts of the environment and strong and coherent organisational cultures. The ISSP encourages researchers to study environments across athletes’ lifespan by examining more and less well functioning talent and DC development environments, elite performance environments, and athletes’ working environments to inform SPPs’ services aimed at optimising environments and facilitating athletes’ transitions.

The cross-border short-term mobility and long-term migration of transnational and immigrant athletes inevitably involve cultural transitions and related acculturation processes. Research on athletes’ transnational careers indicates: (a) diverse migration motives and trajectories, (b) sociocultural and power differences experienced by migrants, (c) that individual agency is enabled and constrained by structural and discursive conditions in which career and life choices are made, and (d) a key role of the cultural transition processes for understanding athletes’ functioning and wellbeing in transnational contexts. SPPs are recommended to give thoughtful attention to differential distribution of power in migrant groups and carefully monitor their transitional processes to augment newcomers’ integration in receiving communities.

Research on athletes’ major normative transitions – JST and athletic retirement – recently took a new turn to explore their temporal (phase-like) structures. Because these transitions last from several months to years, the demands vary across the phases, thus, requiring different coping resources and strategies at each phase. The contextualised JST and athletic retirement frameworks provide SPPs, athletes, and coaches with nuanced information about the transitional processes, and the ISSP endorses this line of research to facilitate athletes’ support in these decisive transitions.

Contemporary athletes lead intense lives and when experiencing several overlapping transitions, they have to prioritise among the demands to distribute resources accordingly. Inspired by the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers, researchers initiated the new lines of transition research, including DC transitions, cultural transitions, Olympic Games transitions, transitions to the residential high-performance centers, and injury transitions – all aimed to improve assistance to athletes in these transitions. The ISSP supports the growing diversity of the transition research but pinpoints that the gap between research and practice still exists and more efforts are required to bridge it.

The career research innovations are echoed in career assistance defined as helping athletes with various career issues in and outside of sport. During the last decade, career assistance was enriched by: (a) taxonomies of career assistance interventions and CAPs; (b) increasing amount of different types of CAPs; (c) new applied frameworks, strategies, and instruments (e.g., tools for monitoring competencies of DC athletes and DC support providers); and (c) new directions in career assistance (e.g., working with athletes’ environment). The most recent development in career assistance is a re-conceptualisation of mental health from seeing it only as a resource to being both a resource and an outcome of the athlete career development. This shift contributed to introducing the concept of athlete career excellence defined as an athlete’s ability to sustain healthy, successful and long-lasting career in sport and life. The ISSP advocates for inter- and intra-disciplinary collaborations in support teams (e.g., of the mental health officer, SPP, DC support provider and other experts) to facilitate athletes’ striving for career excellence.

The deeper we move to understanding the complexity of athletes’ career development and transitions, the more gaps are getting visible. Many athletic populations and context are still unexplored. Many athletes experience mental health issues indicating ineffective coping with performance, career, and personal demands, but researchers favour studying successful athletes and environments leaving crisis-transitions and less successful environments at the margins of their interests. The ISSP sets the following challenges for the ACD: (a) to develop the newly identified lines of career research and assistance within the cultural praxis of athletes’ careers, (b) to study and support marginalised athletic populations (e.g., disabled and cultural minority athletes), (c) to pay attention to crisis-transitions, risk and protective factors in terms of athletes’ mental health, injuries, burnouts, and dropouts, (d) to move beyond athletic career and study athletes’ employability competencies, DCs in sport and work, the athlete-to-coach transition, athletes’ working environments, and coaching careers, (e) to create international networks of SPPs to collaborate on assisting athletes in cultural transitions, (f) to focus on successful and less successful athletes’ environments and the continuity in support when athletes move from one environment to the next, and (g) to develop applied frameworks and strategies facilitating athletes’ striving for career excellence. To meet these challenges the ISSP supports methodological diversity in career research and multiple approaches in career assistance.

The ISSP, through this and its other recent Position Stands (2013; 2015; 2017; 2018; see https://www.issponline.org/index.php/publications/position-stands), encourages further interactions between different sport psychology discourses (e.g., ACD, talent development, cultural sport psychology, performance enhancement, mental health, injury) to deepen our understanding of the complexity and interrelatedness between performance, career, and personal development of diverse athletic populations within the dynamic and multicultural world of sport. Having athlete career excellence on the sport psychology agenda requires integration of competencies and efforts.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the ISSP Managing Council members and the two external reviewers for their constructive feedback to the earlier draft that helped to improve the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Agergaard, S., & Ryba, T. V. (2014). Migration and career transitions in professional sports: Transnational athletic careers in a psychological and sociological perspective. Sociology of Sport Journal, 31(2), 228–247. doi: https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2013-0031

- Alfermann, D., & Stambulova, N. (2007). Career transitions and career termination. In G. Tenenbaum, & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 712–736). New York: Wiley.

- Aquilina, D., & Henry, I. (2010). Elite athletes and university education in Europe: A review of policy and practice in higher education in the European Union member states. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 2(1), 25–47.

- Aunola, K., Selänne, A., Selänne, H., & Ryba, T. V. (2018). The role of adolescent athletes’ task value patterns in their educational and athletic career aspirations. Learning and Individual Differences, 63, 34–43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.03.004

- Blodgett, A. T., & Schinke, R. J. (2015). “When you’re coming from the reserve you’re not supposed to make it”: Stories of Aboriginal athletes pursuing sport and academic careers in mainstream” cultural contexts. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 115–124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016./j.psychsport.2015.03.001

- Bonhomme, J., Seanor, M., Schinke, R. J., & Stambulova, N. (2018). The career trajectories of two world champion boxers: Interpretive thematic analysis of media stories. Sport in Society. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1463727

- Brandăo, M. R., & Vieira, L. F. (2013). Athletes’ careers in Brazil: Research and applications in the land of ginga. In N. Stambulova, & T. V. Ryba (Eds.), Athletes’ careers across cultures (pp. 43–52). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Brown, D. J., Fletcher, D., Henry, I., Borrie, A., Emmett, J., Buzza, A., & Wombwell, S. (2015). A British university case study of the transitional experiences of student-athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 78–90. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.002

- B-WISER. (2018). Erasmus+ Sport project: “Be a Winner In elite Sport and Employment before and after athletic Retirement”. Retrieved from http://www.vub.ac.be/topsport/b-wiser

- Carless, D., & Douglas, K. (2012). Stories of success: Cultural narratives and personal stories of elite and professional athletes. Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise, 1, 51–66.

- Chroni, S., Pettersen, S., & Dieffenbach, K. (2019). Going from athlete-to-coach in Norwegian winter sports: Understanding the transition journey. Sport in Society. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1631572

- Cosh, S., & Tully, P. J. (2015). Stressors, coping, and support mechanisms for student athletes combining elite sport and tertiary education: Implications for practice. The Sport Psychologist, 29(2), 120–133. doi: https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2014-0102

- Côté, J., Baker, J., & Abernethy, B. (2007). Practice and play in the development of sport expertise. In G. C. Tenenbaum & R. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (3rd ed., pp. 184–202). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Cruickshank, A., Collins, D., & Minten, S. (2015). Driving and sustaining culture change in professional sport performance teams: A grounded theory. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 20, 40–50.

- Danish, S. J., Petitpas, A. J., & Hale, B. D. (1993). Life development intervention for athletes: Life skills through sports. The Counseling Psychologist, 21, 352–385.

- Debois, N., Ledon, A., & Wylleman, P. (2015). A lifespan perspective on the dual career of elite male athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 15–26. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.011

- De Brandt, K., Wylleman, P., Torregrossa, M., Schipper-Van Veldhoven, N., Minelli, D., Defruyt, S., & De Knop, P. (2018). Exploring the factor structure of the Dual Career Competency Questionnaire for Athletes in European pupil- and student-athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2018.1511619

- Defruyt, S. (2019). Dual career support providers. Competencies, support strategies and education (Doctoral thesis). Vrije University Brussels, Belgium.

- Defruyt, S., Wylleman, P., Torregrossa, M., Schipper-van Veldhoven, N., Debois, N., Cecić-Erpič, S., & De Brandt, K. (2019). The development and initial validation of the dual career competency questionnaire for support providers (DCCQ-SP). International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1581827

- Diehl, R., Poczwardowski, A., Stambulova, N., O’Neil, A., & Haberl, P. (2019). Transitioning to and thriving at the Olympic Training Center, Colorado Springs: Phases of an adaptive transition. Sport in Society. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2019.1600299

- ECO-DC. (2018). Erasmus+ Sport project: “Ecology of Dual Career: Exploring Dual Career Development Environments across Europe.” Retrieved from https://dualcareers.eu/

- Ekengren, J., Stambulova, N., & Johnson, U. (2019). Development and validation of career-long psychological support services in Swedish handball. In B. Strauss et al. (Ed.), Abstract book of the 15th European congress of sport and exercise psychology (pp. 59). Muenster: WWU Muenster.

- Ekengren, J., Stambulova, N., Johnson, U., & Carlsson, I.-M. (2018). Exploring career experiences of Swedish professional handball players: Consolidating first-hand information into an empirical career model. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2018.1486872

- Ely, G., & Ronkainen, N. (2019). “It’s not just about football all the time either”: Transnational athletes’ stories about the choice to migrate. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1637364

- Etzel, E. F. (Ed.). (2009). Counseling and psychological service for college student-athletes. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- European Commission. (2012). EU guidelines on dual careers of athletes: Recommended policy actions in support of dual careers in high-performance sport. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/sport/library/documents/dual-career-guidelines-final_en.pdf

- Franck, A. (2018). The junior-to-senior transition in Swedish athletes: A longitudinal study (Doctoral thesis). School of Health and Welfare, Halmstad University.

- GEES. (2016). Erasmus+ Sport project “Gold in Education and Elite Sport”. Retrieved from http://gees.online/?page_id=304&lang=en

- Guidotti, F., Cortis, C., & Capranica, L. (2015). Dual career of European student-athletes: A systematic literature review. Kinesiologia Slovenica, 21(3), 5–20.

- Harwood, C. G., & Knight, C. J. (2015). Parenting in youth sport: A position paper on parenting expertise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 24–35.

- Henriksen, K. (2015). Developing a high-performance culture: A sport psychology intervention from an ecological perspective in elite Orienteering. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 6, 141–153.

- Henriksen, K., Larsen, C. H., & Christensen, M. K. (2014). Looking at success from its opposite pole: The case of a talent development golf environment in Denmark. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(2), 134–149. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.853473

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R. J., Moesch, K., McCann, S., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., & Terry, P. (2019). Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473

- Henriksen, K., & Stambulova, N. (2017). Creating optimal environments for talent development: A holistic ecological approach. In J. Baker, S. Cobley, J. Schorer, & N. Wattie (Eds.), Routledge handbook of talent identification and development in sport (pp. 271–284). London: Routledge.

- Henriksen, K., Stambulova, N., & Roessler, K. K. (2010). Holistic approach to athletic talent development environments: A successful sailing milieu. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 11, 212–222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.10.005

- Henriksen, K., Stambulova, N., & Roessler, K. K. (2011). Riding the wave of an expert: A successful talent development environment in kayaking. The Sport Psychologist, 25(3), 341–362.

- Henriksen, K., Storm, L. K., Kuettel, A., Linnér, L., & Stambulova, N. (2020). A holistic ecological approach to sport and study: The case of an athlete friendly university in Denmark. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101637

- Henriksen, K., Storm, L. K., & Larsen, C. H. (2018). Organizational culture and influence on developing athletes. In C. Knight, C. Harwood, & D. Gould (Eds.), Sport psychology for young athletes (pp. 216–228). London: Routledge.

- Henriksen, K., Storm, L. K., Stambulova, N., Ryrdol, N., & Larsen, C. H. (2018). Successful and less successful interventions with youth and senior athletes: Insights from expert sport psychology practitioners. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology. doi: https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2017-0005

- Huang, Z., Chen, M., & Qiao, N. (2013). Athletes’ careers in China: Advances in athletic retiremnt resercah nad assistance. In N. Stambulova, & T. V. Ryba (Eds.), Athletes’ careers across cultures (pp. 65–76). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Inkson, K. (2006). Understanding careers: The metaphors of working lives. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Ivarsson, A., & Johnson, U. (2020). Psychological bases of sport injuries (4th Ed.). Morgantown, VW: Fitness Information Technology.

- Ivarsson, A., Stambulova, N., & Johnson, U. (2016). Injury as a career transition: Experiences of a Swedish elite handball player. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(4), 365–381. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2016.1242149

- Knight, C. (2016). Parenting in sport (editorial). Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 5, 84–88.

- Knight, K. J., Harwood, C. G., & Sellars, P. A. (2018). Supporting adolescent athletes’ dual careers: The role of an athlete’s social support network. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 38, 137–147. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.06.007

- Kontos, A., & Arguello, E. (2010). Sport psychology with Latin American athletes. In R. J. Schinke (Ed.), Contemporary sport psychology (pp. 181–196). New York, NY: Nova Science.

- Larsen, C. H., Alfermann, D., Henriksen, K., & Christensen, M. K. (2013). Successful talent development in soccer: The characteristics of the environment. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2, 190–206.

- Lavallee, D., & Wylleman, P. (Eds.). (2000). Career transitions in sport: International perspectives. Morgantown, WV: Fitness Information Technology.

- Li, M., & Sum, R. K. W. (2017). A meta-synthesis of elite athletes’ experiences in dual career development. Asia Pasic Journal of Sport and Social Science, 6(2), 99–117.

- Light, R. L., Evans, J. R., & Lavallee, D. (2017). The cultural transition of Indigenous Australian athletes into professional sport. Sport, Education and Society, 24, 415–426.

- López de Subijana, C., Barriopedro, M., & Conde, E. (2015). Supporting dual career in Spain: Elite athletes’ barriers to study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 57–64. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.012

- Lupo, C., Mosso, C. O., Guidotti, F., Cugliari, G., Pizzigalli, L., & Rainoldi, A. (2017). The adapted Italian version of the baller identity measurement scale to evaluate the student-Athletes’ identity in relation to gender, age, type of sport, and competition level. Plos One. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169278

- Martindale, R. J. J., & Mortimer, P. (2011). Talent development environments: Key considerations for effective practice. In D. Collins, A. Button, & H. Richards (Eds.), Performance psychology: A practitioner's guide (pp. 65–84). London: Elsevier.

- Mathorne, O., Henriksen, K., & Stambulova, N. (2019). An “organizational triangle” to coordinate talent development: A case study in Danish swimming. Case Studies in Sport and Exercise Psychology, 4, 11–20.

- Meisterjahn, R. J., & Wrisberg, C. A. (2013). “Everything was different”: An existential phenomenological investigation of US professional basketball players’ experiences overseas. Athletic Insight, 15, 251–270.

- Miller, P., & Kerr, G. (2002). Conceptualizing excellence: Past, present and future. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14, 140–153.

- Oghene, O. P., Schinke, R. J., Middleton, T. R. F., & Ryba, T. V. (2017). A critical examination of elite athlete acculturation scholarship from the lens of cultural sport psychology. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 48(6), 569–590.

- Park, S., Lavallee, D., & Tod, D. (2013). Athletes’ career transition out of sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6, 22–53. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.687053