ABSTRACT

There have been growing discussions across international societies since 2017 focused on athlete wellness and athlete care. The human condition of high-performance athletes requires life balance, holistic personhood, and a functional athletic career with the support of integrative resources from sport organisations. During two successive International Society of Sport Psychology Think Tanks on Athlete Mental Health in 2018 and 2019, an international group of practitioners from Olympic and professional sport organisations discussed topics spanning what athlete mental health should look like, while problematising an overly narrow focus on athlete mental ill-health (i.e., an unbalanced approach to the topic), how it is being diagnosed, and how it is understood through research. Discussions have advanced into structural suggestions regarding standards of care for athletes in their daily training environments and at major international tournament events. Within this consensus statement, the authors focus our discussions onto athlete acute care. Emphasis is placed on how an integrated support team can work efficiently with high-performance athletes when acute care is required in two general contexts: (1) within the training environment, and (2) onsite at major events. A model is proposed to spur discussions and better standards to guide the athlete acute care process. Recommendations are provided for sport psychology practitioners, researchers, and high-performance sport organizations.

During Autumn 2017, a sub-group of the International Society of Sport Psychology’s (ISSP) recently appointed Managing Council launched a think tank programme focusing on pressing issues and emerging topics. The concept of an ISSP International Think Tank about athlete mental health followed earlier position stands on the topic, developed by the International Society of Sport Psychology (Schinke et al., Citation2017) and furthered by the European Federation of Sport Psychologists (Moesch et al., Citation2018) and the International Olympic Committee (Reardon et al., Citation2019). The series began in 2018 with practitioners nominated by key continental sport psychology societies, including the Asian South Pacific Association of Sport Psychology, the Association for Applied Sport Psychology, the European Federation of Sport Psychology, and the International Society of Sport Psychology. The participants met in Odense, Denmark, hosted locally by Team Denmark and the University of Southern Denmark for two days. The reasoning behind the meeting was that, in the field of sport psychology, there had yet to be an opportunity for identified experts to converge in one location and share their experiences and views about athlete mental health in high-performance sport. Furthermore, the group identified a need within the international sport community, especially within high-performance sport organisations, for improved mental health literacy practices (see Stirling & Kerr, Citation2009, Citation2013). The primary (i.e., daily) points of contact for high-performance athletes have often been personal coaches and teammates, both of whom have been found to lack in mental health literacy (Bissett et al., Citation2020). The consequence of the aforementioned gap has and, in many instances, still contributes to social (i.e., lack of social and emotional support in time of need) and structural (i.e., lack of access forethought, leading to efficient access to care resources) stigma surrounding athlete mental ill-health (Rice et al., Citation2016). These limitations further delay response rates to treatment when athletes need acute care and follow-up support (Reardon et al., Citation2019).

The Think Tank members produced a consensus statement (see Henriksen et al., Citation2020), in which they offered six recommendations for how to reinforce and augment athlete mental health. The group agreed that (1) mental health is a core component of a culture of excellence; (2) mental health within sport contexts needs to be clearly defined; (3) the assessment of athletes’ mental health needs to expand in terms of methodological approaches and lines of inquiry; (4) mental health is an essential resource for athletes during and post-athletic career; (5) environments can nourish and malnourish athletes’ mental health; and, central to the current contribution and most pertinent to this statement, (6) athletes’ mental health is everybody’s business, but should be overseen by one or a few key, well-informed organisational resources, termed mental health officers (i.e., termed MHOs). The necessity for an MHO was further clarified in the subsequent 2019 ISSP Athlete Think Tank, where the topic was situated in relation to the Olympic quadrennium (Henriksen et al., Citation2020). Building upon athlete mental health being everybody’s business, the authors identified current limitations in mental health literacy, starting within training environments and continuing into the competition environment (i.e., Games phase). The implementation of athlete support could then be offered through interdisciplinary mental health care teams (see Van Slingerland et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, the aforementioned think tank also clarified that athlete mental health needs could vary in terms of stressors and treatment, contingent on whether a performer was struggling within a training or Olympic environment.

The oversight of athlete acute care is an essential process in high-performance sport organisations. Acute care refers to the immediate support provided by one or a few designated service providers in response to an athlete’s mental health crisis, standing in contrast to longer-term support that fortifies the athlete’s resilience or coping skills. Access to resources varies dependent on the time of season and specific year in relation to a major event (McCann et al., Citation2020, apr. 1). When major events draw nearer, access to psychological and broader mental health resources tend to increase to help buffer the athlete against increased performance demands and expectations. When major events are completed and new training cycles begin, the disbursement of funds is often allocated to essential services most pertinent at the time, such as athlete relocation in and out of the organisation, equipment, new technology, and the launch into international travel and tournament entry fees. Examining proposition six, the discussants began to consider the role of organisational resources when acute care is needed. Staff in high-performance organisations understand each athlete’s human condition is compromised in times of acute stress, which compound life stressors with pre-existing athletic and personal conditions (see also Henriksen et al., Citation2020; Reardon et al., Citation2019). When athletes are overloaded with demands they can reach a point where they require critical care (Stambulova et al., Citation2020). Proposition six was developed for when a treatment process is required.

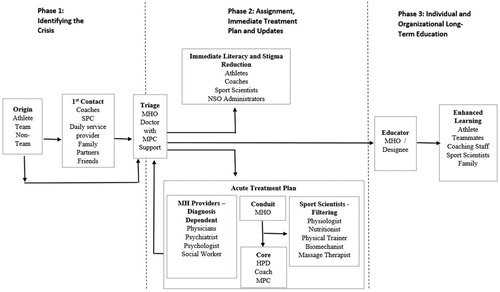

What follows is the result of email and video-conferencing exchanges and the consensual formulation of a conceptual diagram, developed to spur how a high standard of care toward an athlete in crisis might be implemented systematically and efficiently, integrating the entire support team’s resources. The conceptual diagram was developed with the specific intention of demonstrating how to provide acute care to individual athletes and emphasising singular athlete cases. We recognise providing efficient care to organisational staff members (e.g., coaches) in crisis, or teams facing a collective crisis (e.g., a sexual abuse allegation) is also necessary, but beyond the scope of the developed diagram. Our objectives with the acute athlete care model are to streamline and optimise how an athlete moves through the acute stage, the alignment of longer-term support resources, and the intended outcome of a more resilient individual and organisation. We also recognise that the model and description that follow are developed in relation to organisations with vast resources. Smaller organisations would potentially necessitate providers adopting multiple roles, again, to streamline treatment plans. The forthcoming model is sequenced chronologically into (1) interventions occurring in training environments, and (2) acute care transpiring at, and in the aftermath of, major sporting events.

The authorship team

The contributors were approached by the first author. Each author is an active mental performance consultant (termed an MPC), who works weekly with Olympic athletes as part of national sport organisations or as multisport appointments employed by a national Olympic committee. The authors include mental performance consultants from clinical psychology and sport science. The authors have infused a multinational series of perspectives, synthesised into a shared vision of acute athlete care, found in . The contributors are from Canada, China, Denmark, the Netherlands, Greece, and the United States. They have each worked with Olympic and Paralympic athletes in their respective countries for a minimum of two decades.

Figure 1. Mental health services organisation plan. SPC = sport psychology consultant; MHO = mental health officer; MPC = mental performance consultant; HPD = high-performance director; NSO = national sport organisation.

The authors followed a systematic process in the conceptualisation of . First, the lead author worked closely with a PhD candidate and identified prospective resources, based on the first author’s experiences as an integrated support team lead and mental performance consultant. The components were then diagrammatically developed into three phases. Phase one targets the people and steps associated with identifying concerns and crises. Phase two applies to the mental health officer’s (termed MHOs) assignment to a best fit service professional, delivery of immediate care services to the athlete, and organisational updates and actions. Phase three highlights augmentations in the athlete’s and the organisation’s long-term development. Once the three phases were identified, stakeholders within and beyond the integrated support team (termed ISTs) were placed inside the schematic. The contributing authors then engaged in discussion over email about the sequence of phases, key stakeholders, and their placement. Next, the authors were tasked with considering the ISSP Executive Report (McCann et al., Citation2020, apr. 1) in lieu of their own national experiences. The report and experiences mentioned above were weighed in relation to how acute athlete care and organisational processes surrounding said care would apply in the contexts of (1) daily training environments, and (2) major tournament events. Next, the initial draft was developed and distributed to the authors. The group was asked to consider the model in terms of two athlete environments (i.e., training environment, onsite at major tournaments), refining the temporal process and the role of identified stakeholders during the three phases of treatment until the model was believed to align with their respective nations’ services or the aspiration of their nations’ services.

Acute care in the training environment

High-performance athletes spend much of their time developing and refining their technical, tactical, and psychological skills in training environments. Training environments provide athletes with a staff of consistent, accessible human resources. Hence, acute athlete care within the daily training environment includes resources that become known to the high-performance athletes as they become established members.

Context demands and expectations. The contextual factors associated with daily training vary dependent on where athletes reside in their yearly training plans and quadrennial cycles. When athletes enter into high-performance sport organisations in the first year of an Olympic cycle, an emphasis is placed on settlement into an unfamiliar training environment, acclimation to training load, potential settlement in a new city and region, potential financial strain associated with the heightened commitment level to the sport organisation and full-time training, elevated performance demands, leaving family and partners behind, and the forging of new relationships inside and beyond training environments. Though organisations often provide transitional support, the stressors and demands experienced during transitions present a challenging period for athletes. Once athletes are familiarised with their system and established within the organisation, demands evolve to performance expectations at international tournaments and continuously solidifying one’s spot in the sport organisation, while simultaneously developing one’s technical, tactical, and psychological skills to a level commensurate with increasing competition demands. Athletes then progress to qualification event preparation, where all of the identified contextual requirements are tested at events that permit progress onward to the major event or alter the athlete’s career trajectory, involving a commitment to retain one’s position or a career transition into lower-level competitive sport or retirement and a transition to the next career within our outside of sport (Schinke et al., Citation2015).

Phase one: Identifying the crisis. Athletes enter into crisis for various reasons, which span pre-existing mental health conditions, poor life habits, personal relationships, training demands, abuse by coaches or organisational staff, and in relation to the above, unhealthy coping responses (e.g., substance misuse, rumination, further types of self-harm). The entry into the acute care process focuses on immediate crisis identification. Crisis identification can originate with the athlete, who then seeks assistance from a coaching staff member, the mental performance consultant, a teammate, or a supportive person outside of the training environment (e.g., family members, partners). The crisis may also be identified by someone other than the athlete, such as a consultant conducting a regular mental health screening or during regular interaction with athletes, a member of the team’s staff, a teammate, or a non-team contact (e.g., a family member, close friend). Following identification, the athlete in crisis is then to be brought into contact with the MHO for triage.

The MHO is the organisation’s triaging designee based on a combination of mental health literacy and the organisation’s diverse athlete needs, derived from their athlete demographics and existing needs patterns. For example, within a sport environment where athletes engaging in substance abuse is the prevailing concern the team physician may be best armed to serve as MHO and provide acute interventions or access to treatment facilities. Alternatively, in an environment where athletes often experience heightened anxiety, a clinical psychologist may be the most likely MHO to identify symptoms of extreme anxiety or provide appropriate counselling. Within some national contexts, the MHO is one person, and in other contexts, a small mental health care team is developed. The assignment of responsibilities must be clear for athletes and staff. Though the MHO may be the designee within a sport context, all skilled health professionals remain important to the acute care model given the athlete’s connectivity with several concurrent, integrated resources. A physician as MHO managing athletes’ substance abuse issues may rely upon a mental performance consultant to help educate athletes on alternative mental skills to cope with their stressors in relation to the training environment. Working within their scope of practice, all service providers contribute in an interdisciplinary way to acute athlete care and developing the strength of the organisation, guided by the MHO. The MHO serves as the communication conduit, linking the coaching staff and management with the acute service provider and the athlete under care in phase two.

Phase one example. Having transitioned into a new training environment in preparation for the upcoming Olympics in four years, an athlete struggled with leaving family and the increased pressure during training sessions. While getting taped for practice by the team’s physiotherapist, the athlete mentioned experiencing consistently decreased mood that impacted the ability to train, furthering to a belief that the sport career was over in an athlete with a singular identity, leading to thoughts of suicide. Recognising that the athlete was entering a crisis, the physiotherapist facilitated a meeting between the athlete and the team’s MPC, who in this case was the designated MHO, who had a readily available list of crisis resources.

Phase two: Assignment, immediate treatment plan and updates. The MHO is tasked with gathering information in a tight time frame from the athlete and collateral contacts, such as personal coaches, teammates, and family members. The objective is to contextualise the information and assign a best suited acute care professional. The acute care service provider(s) in a training environment, tasked with the acute treatment plan, require specific credentials (i.e., scope of practice) to assist the athlete. The service providers within proximity to the training environment ideally include one or more physicians, dependent on the athlete’s needs, a psychiatrist who is either sport specialised or general, dependent on the country where the athlete is being treated, a clinical psychologist when psychology is required without immediate medication, or a social worker, when the acute crisis pertains to familial abuse or domestic violence. The designated provider is then tasked with athlete treatment and acute care, while reporting back to the MHO. As enabled by their professional code of conduct, the flow of information from the MHO to the acute service provider and then back to the MHO permits an integrative and iterative athlete care model that can carry forward from an immediate crisis to long-term athlete and organisational strengthening.

Once acute treatment has begun, the MHO becomes the immediate conduit to the national sport organisation’s staff with stake in the athlete’s psychological needs, particularly the high-performance director (termed HPD), head coach, and MPC, denoted as the core staff consistently focused on athlete oversight in the training environment. The core staff are then tasked with determining the flow of information to the team’s sport scientists, followed by a specific flow of information to each provider relevant to the execution of services. During acute treatment, service providers may recommend or require the athlete to be removed from the training environment to address the crisis at hand (e.g., drug induced psychosis, suicidal ideation). Other crises (e.g., domestic violence, a family death) may not require athletes to take time away from the training environment. One should consider whether removing the athlete from the training environment is necessary, as taking away a significant part of the athlete’s daily structure may further impact their ability to cope with the crisis. Simultaneous with acute treatment for the athlete in crisis, the MHO must facilitate mental health literacy within the training environment to properly support athlete mental health and reduce stigma (Bapat et al., Citation2009).

Within the current model, mental health literacy is differentiated sequentially as “immediate literacy and stigma reduction” during acute care (phase two) and “enhanced learning” as part of long-term education and literacy (phase three). Within the immediate literacy and stigma reduction phase, the MHO will collate the flow of information provided by service providers in collaboration with the MPC (should these two entities be distinct) to develop a mental health literacy information session pertinent to the crisis at hand. The mental health literacy information session would be developed drawing upon what is known to the context in terms of the particular and parallel examples of crisis, how and why these transpire, and what can be learned to augment the athletes’ daily functioning. Staff and athletes will be provided with relevant information to ensure the athlete in crisis is effectively supported. Discussions can pertain to life balance, communication, the psychological challenges associated with the athlete-human condition, self-care, and the effective use of support resources to buffer the athlete from these demands. Due to the different roles athletes and staff members play in supporting an athlete in crisis, information would be shared with the athletes as one group and the team’s staff and leadership separately, as the lived experience would be managed differently dependent on one’s vantage and role in the organisation. Athletes can learn more about the particular crisis their teammate is experiencing, granting empathy and a sense of understanding, while team staff members may be informed of ways to create a more supportive environment, drawing upon their professional interactions. Despite differing mental health literacy information sessions, all discussions should be framed to normalise mental health crises, reinforcing to athletes, staff, and administration that a breadth of life challenges can overwhelm athletes, but that they will be supported by teammates, staff and the organisation via openness, transparency, a caring, structure, and consistency. The inverse response would be dysfunction, whereby crises are not discussed, causing and exemplifying alienation, leading to athletes being stigmatised when they are most compromised (Coyle et al., Citation2017).

Phase two example. Following their initial meeting, the team’s MHO contacted the teammates and family of the athlete in crisis to discuss any recent indications of mental ill-health. Having determined that it was not the first time the athlete had indicated suicidal ideation the MHO recognised that aiding the athlete was beyond their scope of practice and accessed a clinical psychologist that had worked with the team previously to provide acute athlete care. Serving as the team’s MPC, the MHO worked with the high-performance director and coach to discuss improvements to the team’s transition processes for athletes. Concurrently, the MHO prepared separate information sessions for athletes and team staff to discuss how transitions and increased pressure can impact athletes’ mental health, including leading to depression and suicidal ideations. The prepared sessions focused on education, identifying symptoms, how to interact with and support athletes, and normalising mental ill-health in athletes.

Phase three: Individual and organisational long-term education. Successfully managing mental health crises can present long-term opportunities for athletes and organisations to grow, providing the availability of support providers and approaches are managed systematically and efficiently. Inversely, when any structures or processes available to athletes are unclear or inefficient, they leave the athletes and first responders with less clear response pathways. The consequence could result in structural stigmatisation, meaning an impression from the athletes’ vantages that acute athlete care is not an organisational priority, culminating in feelings and beliefs of abandonment and devaluation. The journey through phases one and two should address each athlete’s immediate circumstances, whilst considering the organisation’s role in the case. Once the immediacy of the situation has passed, the athlete, teammates, and organisation can reflect on their understanding and executional functioning of the managed crisis. When the acute response to athlete treatment is successful, the athlete is no longer in crisis, teammates have become aware of, or reacquainted with, the high level of care from their staff, and the organisation has grown from the experience whilst testing their acute care processes. If the athlete was removed from the training environment during treatment, the athlete is reintegrated into the daily training environment and the training environment resumes the responsibility of broader athlete career development. The athlete’s return to play marks a transition into the final phase of athlete and organisational care, termed long-term education.

Long-term education is a dynamic process, where educational content intended for athletes, staff, and organisations is built to strengthen the system. While mental health literacy is the obvious focus of the educational processes, we wish to stress that positive sport environment literacy should also be part of the feedback loop. The long-term literacy phase of the model will integrate knowledge garnered from the resolved crisis with general literacy education to increase the competency of athletes, staff, and organisations. Content may focus on the normalcy of crises as part of being an elite performer, daily hazards, symptoms, and early warning signs, but also on characteristics of environments the support or jeopardise athlete mental health. This could include explaining why mental health does not necessarily exclude possible mental ill-health challenges in athletes who function well on a daily basis. When the immediate crisis has resulted from the accumulation of poor self-care, an overloaded daily schedule, and impeded communication processes between athletes and staff (i.e., there is often more than one reason why an athlete enters into the acute care process), regular presentations can be developed to discuss the catalysts and how these could be navigated effectively. The MHO would be best acquainted with the specific information of the acute case and the educational topics ought then to be discussed with the MPC and they, if two different people, can collaboratively identify the educational stakeholder to develop and deliver educational content to the aforementioned groups. The content will vary in how it might be used by athletes as compared to coaches or sport science staff. The delivery of the content might also be provided by a different presenter by audience, dependent on the nature of the topic. The MPC might be closest to the athletes, due to regular exchanges related to daily mental performance, whereas the integrated support team lead, who might not be the MPC, would have a more regular connection with the sport scientists as the person they report to. The topic matter should be presented by the best versed staff member. The first step in long-term education is the determination by the MHO and MPC of who the educator will be and the subsequent oversight of content development.

General presentations pertaining to athlete mental health literacy, accompanied by follow-up presentations and group discussions focused on pressing topics chosen in relation to the yearly training plan should be scheduled as progressive steps toward organisational education. The feedback from athletes and daily operations staff (e.g., strength and conditioning coaches, athletic therapists, nutritionists) beyond inside knowledge from coaches and MPCs will generate proactive initiatives that are responsive to athletes’ needs and status during each season and during specific times in a multi-season cycle. Foreseeable yearly content can be mapped out in advance, while it is also the MHO’s and MPC’s responsibility to act efficiently to emerging topics through regularly scheduled discussions.

The discussions regarding education to this point have focused on standards of care within an organisation, defined as athletes, staff, and administrators. Family members ought also to be integrated within the educational process. They are identified for the first time in this model in phase three, only because it represents long-term education, and not because it reflects the culmination of an acute care process. Hence, family and close friends are an essential outreach by each National Sport Organization (NSO) throughout an athlete’s career. Depending on the athletes’ age and status, they may include members of the family of origin, partners, and close friends. When personal support systems are well versed in high-performance athletes’ demands, they can provide parallel, congruent support throughout athletes’ careers. Reciprocally, when personal support resources become part of the organisational system, they also become an integral source of information regarding each athlete’s past and current status. Examples of familial and personal support resource training might include how to support the athlete during acclimation to the sport organisation, and how to support the athlete in life balance before, during, and post-career.

Phase three example. Following resolution of the athlete’s crisis, the MHO prepared the knowledge garnered through the acute care process for dissemination to athletes, coaches, organisational members, and the athlete’s personal contacts (e.g., family members, partners). The MHO then decided who the optimal educator was in the long-term education process and scheduled sessions. The sessions reacquainted attendees with the crisis managed, discussed specific antecedents of the team’s environment that can lead to depression and suicidal ideations, described how the acute care process unfolded to manage the crisis, and normalised the experiences of mental ill-health and crises in athletes as part of an athletic career. Building from the information gained during the acute care process, discussions within the long-term education sessions shifted to developing changes to prevent future instances of crises, including environmental improvements the team can make to alleviate or prevent mental ill-health issues in the future. In this case, the team introduced a peer-mentoring process to aid athletes transitioning into the training environment, low-pressure training sessions during periods of transition, and familial education on the strains of a high-performance athletic career.

Acute care at major tournaments

The context of major tournaments presents a second environment where athletes can experience acute crises. The athletes might arrive at a major event in a compromised state, or the crisis could emerge as a result of individual responses to onsite catalysts or emerging personal crises unrelated to the sport environment. Several of the acute providers named in the training environment plan might be available onsite, depending on the type of major tournament. World championships are often single sport events that typically integrate support from a limited, sport specific onsite staff. Within multisport events, athletes’ services are more diverse, comprised of sport specific staff and national games committee staff, available to complement the aforementioned. The available resources vary further depending on the country and the sport. The acute process would typically necessitate onsite support, followed by the preparation of further acute resources, available once the athlete transits home to the training environment. Hence, the onsite model would be a hybrid version of the previously discussed training environment application. Within this section, we consider how providers and the sequential processes from fit, starting inside a competition environment and resolving post-return.

Phase one: Identifying the crisis. Participating in a major competition can be an experience of intense stress. Pressure can come from high expectations, performance pressure, a sudden severe injury before or during competition, media scrutiny, increased social media engagement, conflicts within the team, lack of ability to sleep, and layered (i.e., multiple competing) complexities. The issues listed above may exacerbate existing athlete mental health challenges and existing diagnoses or be the catalyst of new acute concerns. Identifying athletes in need of assistance and coordinating support can be challenging. The level of support will vary, as credentials may be scarce, coaches and support staff may themselves be under pressure, and the available support may be more focused on performance than mental health. Further, athletes may be reluctant to show weakness and ask for help, because they fear to lose their spot on the team during a crucial career moment or because they might suppress mental ill-health in pursuit of confidence and performance results. These challenges underscore the importance of a clear support structure and protocol for coordination and provision of mental health care.

As outlined in the model, the identification can originate with the athlete, a teammate, a coach, a member of staff or even a family member or a friend. Once the concern is identified, the first point of contact will often be someone in the sport organisation’s support staff, very often the MPC. During a tournament, a quick response is even more essential than usual, and it is of utmost importance that a clear support structure and readily available lines of communication allow for an immediate contact with the MHO or an onsite designee for triage, should the MHO not be in attendance, such as in the case of a primary care physician.

Phase two: Assignment, immediate treatment plan and updates. In the calm and comfort of their home training environment, most coaches and staff in high performance sport will agree that athletes’ mental health is always more important than their performances. At an important tournament with added performance pressure, however, motives may conflict and cloud judgements. There might be the struggle between meeting performance objectives during a summit event and foregoing a potentially contributive performance result to tend to immediate care needs. In some cases, an athlete must leave the stressful sport environment and go home for acute treatment, to physically remove the athlete from a performance environment to reduce anxiety and tend to care as the exclusive focus. With other cases, an athlete can receive help onsite or online, where athletes can be presented with a solid treatment plan that begins onsite in the midst of performance and with a clear course of action upon return to the training environment. Athletes, coaches, and performance staff are not impartial in such questions. Ideally, therefore, a qualified service provider with whom the athletes have established rapport and trust should be designated MHO, be present at the tournament, and take the lead in making care decisions and liaising on the treatment plan. The MHO serves as the communication conduit, setting up links between the athlete and service providers to make sure all staff have some degree of understanding for the acute care process and how to support the athlete(s) in question. Discussions among athletes and staff should normalise crises, given the need for athletes under pressure to be supported by teammates and staff with openness and compassion via established foundations in mental health literacy to reduce stigma (Bapat et al., Citation2009).

Phase three: Individual and organisational long-term education. The onset of phase three will not be at the tournament but rather upon return and successful reintegration of the athlete in the sport environment. For this reason, phase three will not differ from the one described above (previous section – phase three) related to acute care in the training environment. The focus remains on normalising and reducing stigma through providing education to improve mental health literacy among athletes and staff. However, returning from the major event environment allows organisations the unique opportunity to reflectively evaluate the onsite support setup and implementation, followed by implementing any relevant adjustments. Further, it is worth mentioning that after major tournaments, most notably the Olympic and Paralympic Games, athletes may be at increased risk of mental health issues due to isolation and a lack of purpose, meaning, and direction. Scholars have recognised the immediate post-Olympics / major event as a meta-transition (see Schinke et al., Citation2015). The increased vulnerability may unfortunately coincide with support staff being exhausted and less attentive to athletes’ needs (Henriksen et al., Citation2020). Importance must be placed on the post-tournament protocols and ongoing support until athletes have transitioned back to daily training or have shifted from a sport cycle meta-transition to a more elaborate post-athlete career.

Practice to research

The current model has been conceptualised based on processes the practitioners and their organisations utilise in their respective environments and protocols. However, the systematic implementation of a comprehensive acute mental health care plan for high-performance athletes is a relatively recent approach to acute care. Currently, there is a lack of feedback loops that are brought forth through systematic research. It is at each organisation’s discretion whether to utilise qualitative (for in-depth, rich descriptions), quantitative (to rate finite aspects of the model, leading to revision), or hybrid mixed methods approaches. However, we propose that a vast array of systematic research approaches must be gathered by a lead researcher tasked within or assigned to the organisation. The intention is to iteratively refine each national and organisation specific model of acute athlete care, integrating feedback from athletes and the various participants identified in the model.

Summary points

We conclude this consensus statement with six summary points. The summary points centralise practical applications, but also extend to evidence based practices, and so, bridging practitioners and researchers.

Point one: there are three phases of care

There are three phases to the acute care process. The sequential phases are: (1) crisis identification, (2) developing an immediate treatment plan and relative mental health literacy update, and (3) the individual and organisational long-term educational plan. These three phases provide a standard of care with immediacy and longevity.

Point two: triage to acute treatment must be efficient

The purpose of an acute athlete care model is to provide each sport organisation with clear pathways to an efficient resolution from the immediacy of crisis to athletes’ and organisational growth. An effective and expedited triaging process is necessary and necessitates either a direct report from the athlete or indirect report from the first contact to the mental health officer. The MHO requires considerable mental health literacy to provide efficient assignment to a suitable service provider.

Point three: athletes in crisis benefit from a core mental health care team

Within the organisation’s integrated support team, a core sub-group should be in place to develop education and literacy programmes, whilst concurrently supporting the athletes, with guidance from the MHO. The core sub-group should, at very least, tie in the head coach and MPC, as these designees have an existing history supporting the athlete with the psychological requirements of their sport and their careers.

Point four: mental health literacy is an acute and sustained project

Mental health literacy ought to be considered in two steps. Acute literacy pertains to what is learned by the organisation’s stakeholders, including its leadership, staff, and athletes, in the short-term. The acute literacy process reduces social stigmatisation among athletes and staff, culminating in a more comfortable and accepting return of the athlete to the environment. Longer-term literacy pertains to organisational enhancements, informed by the recent crisis, improving upon the organisation’s and athletes’ long-term functioning. Longer-term literacy should extend to at least one immediate point person from the athlete’s personal support system (i.e., a family member or partner).

Point five: A mental health officer or designee is necessary

A MHO is required as part of the daily operational plan of a high-performance sport organisation. The MHO is tasked with the process of triaging and oversight of acute information translation within the organisation. During major sport events, the MHO might not be in attendance, dependent on if the MHO’s role is redundant within a broader multisport sport environment, such as an Olympics. The sport organisation, in collaboration with the MHO, should then assign an onsite MHO designee. The onsite MHO will adopt the role typically expected of an MHO, whilst liaising with the MHO located in the training environment. MHOs require athlete, coach, and support staff mental health literacy. However, the form of literacy is broad based to manage crises in training environments, whereas an onsite designee would be literate in athlete mental health and competent in managing crises in major tournament events, as a contextual expert.

Point six: acute care models must be refined through iteration

Henriksen et al. (Citation2020) proposed that researchers seeking to understand athlete mental health must expand on the use of appropriate and strongly validated instruments and create novel approaches to understand the topic. The current model has been conceptualised to spur systematic and efficient athlete acute care processes. Research is needed in order to refine acute care models. We propose that there will not be a perfect, universal model of care. Rather, each nation and organisation should continue to refine its own model, with evidence-based approaches. Some nations have already produced idiosyncratic plans and the authors of this consensus statement encourage other nations to develop similar action plans, employing as a foundation. The approaches to research can span all forms of methodologies and ontologies but should be iterative and inclusive of the organisation’s key members who are involved with, and touched by, acute athletes’ crises.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bapat, S., Jorm, A., & Lawrence, K. (2009). Evaluation of a mental health literacy training program for junior sporting clubs. Australasian Psychiatry, 17(6), 475–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/10398560902964586

- Bissett, J. E., Kroshus, E., & Hebard, S. (2020). Determining the role of sport coaches in promoting athlete mental health: A narrative review and delphi approach. BMJ Open Sport and Exercise Medicine, 6, e000676. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000676

- Coyle, M., Gorczynski, P., & Gibson, K. (2017). “You have to be crazy to jump off a board any way”: Elite divers’ conceptualizations and perceptions of mental health. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 29, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.005

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R. J., McCann, S., Durand-Bush, N., Moesch, K., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., Cogan, K., Donaldson, A., Poczwardowski, A., Noce, F., & Hunziker, J. (2020a). Athlete mental health in the olympic/Paralympic quadrennium: A multi-societal consensus statement. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(3), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1746379

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R. J., Moesch, K., McCann, S., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., & Terry, P. (2020b). Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(5), 553–560. doi: 10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473

- McCann, S., Henriksen, K., Larsen, C. H., Cogan, K., Donaldson, A., Durand-Bush, N., Hunziker, J., Moesch, K., Noce, F., Parham, W. D., & Poczwardowski, A. (2020, Apr. 1). Executive Summary Report: Mental health and games: Developing support strategies for the unique world of Olympic and Paralympic athletes.

- Moesch, K., Kenttä, G., Kleinert, J., Quignon-Fleuret, C., Cecil, S., & Bertollo, M. (2018). FEPSAC position statement: Mental health disorders in elite athletes and models of service provision. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 38(1), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.05.013

- Reardon, C. L., Hainline, B., Aron, C. M., Baron, D., Baum, A. L., Bindra, A., Budgett, R., Campriani, N., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Currie, A., Derevensky, J. L., Glick, I. D., Gorczynski, P., Gouttebarge, V., Grandner, M. A., Han, D. H., McDuff, D., Mountjoy, M., Polat, A., … Engebretsen, L. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 667–699. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715

- Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., De Silva, S., Mawren, D., McGorry, P. D., & Parker, A. G. (2016). The mental health of elite athletes: A narrative systematic review. Sports Medicine, 46(9), 1333–1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2

- Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2018). International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(6), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

- Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Trepanier, D., & Oghene, P. (2015). Psychological support for the Canadian Olympic boxing team in meta-transitions through the national team program. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 74–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2014.959982

- Stambulova, N. B., Schinke, R. J., Lavallee, D., & Wylleman, P. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and olympic/paralympic athletes’ developmental challenges and possibilities in times of a global crisis-transition. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. Advanced Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1810865.

- Stirling, A. E., & Kerr, G. A. (2009). Abused athletes’ perceptions of the coach-athlete relationship. Sport in Society, 12(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430802591019

- Stirling, A. E., & Kerr, G. A. (2013). The perceived effects of elite athletes’ experiences of emotional abuse in the coach-athlete relationship. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.752173

- Van Slingerland, K. J., Durand-Bush, N., Bradley, L., Goldfield, G., Archambault, R., Smith, D., Edwards, C., Delenardo, S., Taylor, S., Werthner, P., & Kenttä, G. (2019). Canadian centre for mental health and sport (CCMHS) position statement: Principles of mental health in competitive and high-performance sport. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 29(3), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000665