ABSTRACT

To overcome the challenges associated with navigating the talent development pathway to professional rugby, players must possess certain psychological skills and characteristics (PSCs), e.g., motivation, confidence, and coping skills. It is essential to understand the PSCs that assist players in successfully transitioning through a talent development pathway and at the professional level, as that knowledge could be applied to enhancing psychological support. The goal of this narrative review was to synthesise research examining the PSCs that contribute to rugby players overcoming challenges to optimise their performance. To ensure objectivity within this review, a systematic approach was taken to the literature search and selection process of papers. Four databases were searched, and the key search terms used were “rugby” “psych*” “mental” and various combinations of these terms. From this process, ten relevant papers were identified. The review revealed that players need to possess a range of PSCs, notably motivation, commitment, coping skills, confidence, focus and self-regulation to navigate the talent development pathway in rugby successfully. It is suggested that players should be taught a wide range of psychological skills so they can develop the skills and characteristics to enable them to deal with the challenges they face and to optimise their performance. Future research should examine whether a training programme based on the PSCs identified would have positive effects on players navigating the talent development pathway to professional rugby.

Rugby Union (hereafter referred to as rugby) is a physically demanding contact sport. It is one of the world's most popular sports with 9.2 million men, women and children registered as players worldwide as well as a fanbase of 344 million (World Rugby, Citation2019). Furthermore, the Rugby World Cup is now the world's third-largest sporting event after the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup (Corrado et al., Citation2014). Rugby is a game characterised by players engaging in frequent bouts of high-intensity activity (e.g., sprinting and tackling), separated by short bouts of low-intensity activity (e.g., jogging) (Corrado et al., Citation2014). In a rugby match, there are 15 players on the field from each team, and each team has eight substitutes. A match at senior level is usually 80 min in duration (Quarrie et al., Citation2001) which is split into two halves with no time outs and a short half-time period of fifteen minutes (Hodge et al., Citation2014). There is a range of different playing positions, each with its own set of demands. Overall, numbers one to eight are forwards, and nine to fifteen are backs. Due to different positional demands, there are significant differences between the physical profiles of forwards and backs. The primary role of forwards is to gain and retain possession, whereas backs are the main points scorers (Casserly et al., Citation2019). Positional demands require forwards to have a greater body mass and for backs to have greater levels of aerobic fitness (Casserly et al., Citation2019)

Competitive rugby is played at all ages and levels, including school, community, club professional and international (Ranson et al., Citation2018). According to World Rugby annual review reports, in the last 10 years rugby participation numbers have increased by almost six million world-wide (World Rugby, Citation2021). Due to the rise in popularity, there is also an increase in competitiveness, particularly at the professional level. This competitiveness exists not just between teams to win but also between players as they compete to be selected for teams, talent development programmes and for professional contracts. Therefore, to be competitive, professional rugby teams and organisations worldwide must identify talented players. However, to ensure that these players fulfil their potential, they must also provide development programmes that will ensure these players reach that potential (Mann et al., Citation2017).

Talent development programmes for rugby union players can vary between countries. For example, in England, which has the highest participation than any other nation, there is a youth system referred to as an age grade structure in which players participate according to annual age categories (e.g., under 13 [U13] or under 18 [U18] years of age) The Rugby Football Union (RFU) governs this stage in terms of participation and talent identification and development (TID) (Roberts & Fairclough, Citation2012). TID programmes are delivered through fourteen Regional Academies that are typically aligned to professional rugby union clubs. From about 15 years of age players are identified from community or school rugby and invited to train within one of these Regional Academies (Read et al., Citation2018). At 18 years of age, a player then potentially signs a professional contract with the club and remains within the academy programme until their early twenties (Till et al., Citation2020). In contrast, in Ireland, the development of players is facilitated by the Irish Rugby Football Union (IRFU) through their Long-Term Player Development Programme (Wood et al., Citation2018). There are provincial academies aligned to the four professional teams (Baker et al., Citation2013). To progress to the academy players are initially selected to regional development squads. From there they progress to age-grade squads (e.g., U18 Clubs, U18 Schools, U19s, U20s). At around 18 years of age a player can be chosen for a sub academy programme which is a year player complete before being selected to an academy. Players typically remain in the academy programme for three years, subject to review, after which, if selected, they sign a professional contract with the senior team. Players engaged in these talent development programmes can face numerous challenges. To deal with these challenges, players must possess appropriate psychological skills and characteristics (PSCs). Therefore, developing players must be provided with effective psychological training and support within their talent development pathway.

Challenges of rugby union pathway

Since becoming professional the nature of the demands and challenges facing rugby players at each stage of the talent development pathway, from age grade to professional, have changed (Nicholls et al., Citation2006).

Physical challenges

From a playing perspective, the game has become more physically demanding, and as a result, the expectations of players’ physical abilities increased. At professional level, from 1995 to 2020, the percentage of time the ball is in play during a match increased almost 50% from 27 min to 39 min which would suggest that players need to be fitter and remain focused for longer (World Rugby, Citation2020). Also at professional level, player mass has increased significantly from 1991 to 2019, the median mass of forwards in 2019 was 113 kg as compared to 103 kg in 1991, in backs the increase was from 83 kg in 1991–92 kg in 2019 (Tucker et al., Citation2021). Body size has become vastly important for success in rugby with Sedeaud et al. (Citation2012) revealing that body size discriminated between successful and unsuccessful teams in the 1987 and 2007 Rugby World Cups.

Physical attributes such as body size have also become linked to progression within rugby. Jones et al. (Citation2018) compared the height, body mass, strength, and speed of school U18 and academy players. Their results revealed that academy players were taller, heavier, stronger, and faster than their school counterparts. These findings taken together would suggest that young players aspiring to reach professional level are faced with the challenge of becoming bigger, stronger and faster (Till et al., Citation2016). It could be argued that because players are now stronger and faster that there are more injuries as players are being tackled at a faster rate by a stronger force. For example, the match injury incidence rate for players in an English rugby U18 academy across three seasons was 47/1000 h (Palmer-Green et al., Citation2015) while the rate for U18 elite schoolboy players was 77/1000. While a study of Welsh professional players over four seasons revealed a match injury incidence rate of 99.1/1000 h (Bitchell et al., Citation2020). These challenges can lead to the “dark side” of rugby (McKenna & Thomas, Citation2007) in which age grade and academy players are under considerable pressure to cut corners to achieve the expected physical attributes to be successful. Evidence for the effect of these challenges on players were revealed by Didymus and Backhouse (Citation2020) as they reported that rugby players that compete at national one level or above in the UK, dope to cope with stressors such as injury, pressure to perform, selection and weight and size expectations.

Psychological challenges and stressors

Players from age grade to professional also experience a range of psychological challenges and stressors. Players at each level, must try to meet various in game demands such as fulfilling the requirements of their positional role, executing the team game plan and switching between attack and defence (Hodge et al., Citation2008). To achieve this effectively players need to possess the necessary psychological skills (Hodge et al., Citation2008). Outside of games, players must also meet an evolving array of demands to be successful in a talent development or professional environment.

Players between 15 and 18 years of age train and compete within multiple rugby programmes (e.g., school, club, regional academy) and multiple sports. Challenges associated with this stage include meeting the demands of multiple training and competitive environments as well as multiple coaching systems (Till et al., Citation2020). Also at this time, players face the challenge of balancing school and rugby commitments (Till et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, age grade and academy level players have to deal with the transitions such as from junior to senior or academy to the first-team (Finn & McKenna, Citation2010). Previous research has highlighted various challenges facing academy players such as coping with the academy to first-team transitions (Finn & McKenna, Citation2010) and why players with high potential often do not make it to professional level (Taylor & Collins, Citation2019). Finn and McKenna (Citation2010) revealed a comprehensive list of challenges faced by players during the academy to the first-team transition. They identified the following playing-related challenges: (i) increases in the physical challenges of a first team training and playing schedule; (ii) a need for players to continually train and work hard to prove their value to the team; (iii) the strain of developing new relationships with new coaches; (iv) the pressure of performing at the highest domestic levels of their sports and the challenges of earning respect from their more established yet still unfamiliar peers. Further lifestyle challenges include (v) social strains of significant others to engage in distracting social activities; (vi) pressure from agents; (vii) financial pressure and unhelpful behaviours such as high levels of alcohol consumption and poor diets (Finn & McKenna, Citation2010). At professional level players need to deal with further challenges such as being seen as a commodity and securing contracts.

Research examining the stressors experienced by rugby players has mainly focused on professional-level. Nicholls et al. (Citation2006) reported on the stressors professional rugby players experienced during matches and training. The most cited stressors during this time were injury, mental error, and physical error. Furthermore, professional players identified the number of matches played and the recovery period, diet, sleep, and travel as factors that they believed contributed to their experience of stress and negative affective states when overtraining during the preseason. Acknowledging the limitation of just examining competitive stressors Nicholls et al. (Citation2009) explored the lifestyle stressors of professional rugby players. This study indicated that players rated diet, climate, sleep, and health as worse than normal on training days. In contrast, home-life, friends, and recreation were rated as significantly better than normal on rest days, highlighting the challenge of balancing rugby and life stressors. Similarly, research examining the stressors experienced by U18 players revealed that the most frequently-cited stressors were making a physical error, receiving coach/parental criticism, making a mental error, injury, and observing an opponent play well (Nicholls et al., Citation2006).

provides a list of previous research examining challenges and stressors experienced by rugby players according to playing level.

Table 1. Articles examining challenges and stressors experienced by rugby players according to playing level.

The purpose of this narrative review is to overview the research examining PSCs that contribute to rugby players overcoming challenges to reach their optimal performance. The aims of this review are to (i) provide an overview of the research on PSCs that contribute to the development and performance of rugby players at age grade, academy, and professional level (ii) provide a rugby and pathway stage specific list of PSCs that could inform the psychological training and support provided to rugby players at the different stages of their development pathway and (iii) highlight any limitations in the existing literature.

PSCs and talent development

A common reason given for athletes with high potential not being successful is, despite having many of the prerequisite physical skills for elite sport, they do not have sufficient psychological resources (Holt & Mitchell, Citation2006; Taylor & Collins, Citation2019). The argument that potentially crucial PSCs are often overlooked within talent development environments has existed within the research for several years (Abbott & Collins, Citation2004; Gledhill & Harwood, Citation2015). Even recently, it has been suggested that the provision of sport psychology consultancy services in rugby is not commonplace (Mellalieu, Citation2017). Therefore, suggesting that even though it is a challenging time for players, there is a lack of focus on PSCs throughout talent development pathways in rugby.

Players must possess a range of psychological characteristics to manage the challenges and stressors they may face. Furthermore, although players should be provided support and training for the challenges they face as they negotiate the talent development pathway, they must also be prepared for the challenges they will face in the transition to professional level. To develop these characteristics, they should be taught and assisted in developing a range of psychological skills. Dohme et al. (Citation2019) highlighted a range of PSCs that are facilitative of youth development across a range of sports. Furthermore, the Psychological Characteristics of Developing Excellence (Macnamara et al., Citation2010a, Citation2010b) are a range of PSCs that have been suggested as relevant for young athletes negotiating development pathways (Collins et al., Citation2019). However, Collins et al. (Citation2019) indicated that this is a broad range of PSCs and a list of PSCs for specific contexts may be needed. Conversely, Taylor and Collins (Citation2019) reported that a full set of psychological skills should be taught as part of a curriculum in a development setting such as an academy. To effectively teach a curriculum of psychological skills, it must be structured in line with the demands and characteristics of the targeted sport (Holland et al., Citation2010). Hence, to provide effective support to players during their talent development pathway, we must identify the relevant PSCs that players need to possess to progress successfully in their specific sport.

Research on talent development in rugby is limited (Dohme et al., Citation2019; Drew et al., Citation2019). For example, from the studies identified in a recent review of qualitative research in junior to senior transitions, soccer was the type of sport most researched at 37% in comparison to the next highest, which was track and field at 11%. Rugby, on the other hand, was only examined as part of one multi-sport study (Drew et al., Citation2019). Research on PSCs needed for talent development in rugby is even more limited. In their recent review of the PSCS facilitative of youth athletes’ development, Dohme et al. (Citation2019) identified 25 papers which comprised of a total population of 4,021 athletes. Of these athletes, 80.58% played soccer and only 1.34% played rugby. Although the research on rugby is limited, there seems to be a focus on PSCs such as commitment, coping skills and self-regulation (Taylor & Collins, Citation2019; Hill et al., Citation2015). Therefore, as PSCs needed for development should be context and sport-specific (Larsen et al., Citation2012), more research is needed within rugby.

Method

This paper is a narrative review of the contribution of PSCs in dealing with the challenges and stressors faced by rugby players. To avoid confusion and ambiguity, this review will use the following terms when discussing the psychological aspect of talent development: psychological characteristics and psychological skills. The term psychological characteristics will refer to “qualities of the mind” (Dohme et al., Citation2016, p. 19) which are innate predispositions or traits. Psychological characteristics are relatively stable but can be enhanced or strengthened through systematic development (Dohme et al., Citation2016). The term psychological skills, however, will refer to “skills of the mind” (Dohme et al., Citation2016, p. 20), which is an individual's ability to use learned strategies to achieve a specific result. Therefore, psychological skills can enhance or develop psychological characteristics (Dohme et al., Citation2016).

A narrative review was considered to be a more appropriate method than a systematic review given the small number of studies in the area (Steidl-Müller et al., Citation2019). However, as narrative reviews can be thought of as less objective than systematic reviews (Hudson et al., Citation2016), the search strategy and selection process will be outlined.

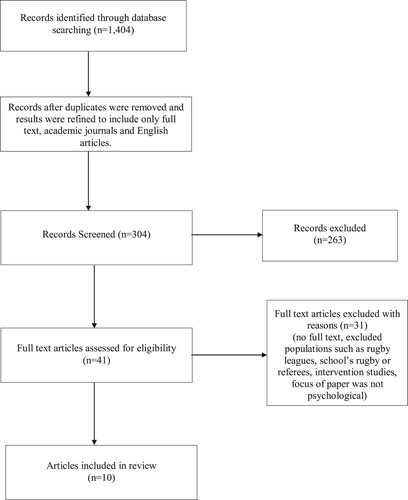

Four databases were searched, including SportDiscus, PsycArticles, PsychINFO and Scopus. The key search terms used were “rugby” “psych*” “mental” and various combinations of these terms. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) electronically-accessible English language publication, (2) Full-text academic journal, (3) original research rather than reviews (4) publications focusing on rugby union rather than rugby league, (5) publications that focused on talented populations such as youth or underage teams of professional teams, academies and professional teams.

A flow diagram describing the detailed search strategy, exclusion criteria and article selection process is shown in .

Psychological skills and characteristics that contribute to success in a rugby

The PSCs identified in this review were classified as either psychological characteristics or psychological skills using the definitions outlined in the framework established by Dohme et al. (Citation2016). Using the framework, psychological skills were defined as an athlete’s “ability to use learned strategies to accomplish specific results” (Dohme et al., Citation2016, p. 157). Psychological characteristics were defined as “trait-like dispositions that can, despite being fairly stable and enduring across different situations, be enhanced or strengthened through systematic development and training” (Dohme et al., Citation2016, p. 157).

Ten studies examining the PSCs of talented rugby players were identified for this review (). Four of these studies were exploratory studies that aimed to identify the PSCs of rugby players of different levels. The other six studies focused on how one or more PSCs impact a particular aspect of development or performance in rugby, e.g., injury rehabilitation or burnout. The research has suggested that a lack of a range of PSCs can negatively impact on talent development such as lack of commitment and lack of developmental awareness (Hill et al., Citation2015). Taylor and Collins (Citation2019) further emphasised this idea as they stated that a lack of sufficient psychological resources could have an impact on talent development in rugby including lack of motivation, commitment, confidence, focus and self-regulation. This argument is supported by previous research which has repeatedly reported these characteristics as being crucial for facilitating talent development in rugby (e.g., Hill et al., Citation2015; Holland et al., Citation2010; Woodcock et al., Citation2011).

Table 2. Articles identified examining psychological skills and characteristics in rugby union.

Holland et al. (Citation2010) conducted focus groups with 43 male rugby players to reveal the psychological characteristics they perceived to facilitate their development, included in their results are attentional focus, self-aware learner and confidence which are closely linked to the psychological resources outlined by Taylor and Collins (Citation2019). However, they also reported further characteristics which included enjoyment, responsibility, adaptability, squad spirit, determination, optimal performance state, game sense, and mental toughness. These characteristics were further confirmed when the perceptions of the parents, coaches and sport administration staff of the players that participated in the study were examined by Holland et al. (Citation2010). They revealed the same psychological characteristics as identified by the players as being essential for their development (Woodcock et al., Citation2011). Commitment, attentional focus and attention to detail were also identified as crucial for success in rugby (Corrado et al., Citation2014; Hill et al., Citation2015).

Characteristics related to motivation, focus and confidence are commonly discussed within the talent development literature. However, other characteristics that may have a significant impact on the development and performance of rugby players have also been identified, such as squad spirit (Holland et al., Citation2010). It has also been suggested that transitioning to higher levels in sport is facilitated by passion (Hill et al., Citation2015; Sheard & Golby, Citation2009) as it assists players in preserving in the less enjoyable activities of their development.

So far, the psychological characteristics discussed were revealed in exploratory studies. However, some studies have attempted to examine how psychological characteristics help players deal with specific challenges. Researchers have examined how basic psychological needs fulfilment can identify burnout in elite rugby (Hodge et al., Citation2008) and assist players when rehabilitating from injury (Carson & Polman, Citation2017). Perceived basic needs fulfilment in particular autonomy and competence are predictors of burnout in junior elite rugby players. Furthermore, it has been suggested that by developing autonomy, competence and relatedness while players are rehabilitating it can facilitate the effective return to competition (Carson & Polman, Citation2017). It is imperative that players have the psychological characteristics or are taught the psychological skills to develop the characteristics to deal with these challenges as they are common challenges within rugby. Not being able to deal with these challenges would impede players development and performance in rugby.

Characteristics that can have a negative impact on the development of players have also been identified in the literature. Hill et al. (Citation2015) revealed a range of characteristics that can negatively impact effective talent development in rugby including complacency, disorganisation, failure to overcome challenges, lack of awareness, lack of commitment and loss of focus. Furthermore, it has been highlighted that those players with perfectionistic cognitions can suffer from burnout (Hill & Appleton, Citation2011).

Although a wide range of psychological characteristics were identified in this review, less attention has been given to psychological skills, except for those that are related to self-regulated learning processes such as goal setting, planning & self-organisation and realistic performance evaluation (Hill et al., Citation2015) as well as key psychological skills for young rugby players, including personal performance strategies (e.g., relaxation, routines, self-talk, visualisation), reflection on action and taking advantage of a supportive climate (Holland et al., Citation2010; Woodcock et al., Citation2011). Coping skills were also identified as being important for development in rugby in two studies (Hill et al., Citation2015; Taylor & Collins, Citation2019). As most of the PSCs identified in this review come from exploratory studies, the lack of psychological skills identified may suggest that players were either not being taught, or they were not employing psychological skills.

Practical implications

Rugby specific list of PSCs

One of the aims of this review was to provide a rugby specific list of PSCs that can be taught to players and developed throughout their talent development pathway (). As well as categorising PSCs into psychological characteristics and psychological skills, PSCs in which various terms were synonyms or closely related were grouped together (Dohme et al., Citation2016) e.g., terms confidence and self-belief are grouped together as confidence. The PSCs highlighted in this review would help players deal with the range of challenges and stressors they face. Learning a range of psychological skills can help players develop the psychological characteristics needed to negotiate these challenges and stressors. By implementing these skills and possessing the necessary characteristics, players can deal with the various challenges they face. PSCs do not have one isolated function; rather, they can be applied to various situations and challenges. For example, motivation is crucial for any athlete that wishes to seek excellence in their sport (Gagné, Citation2010). It can assist the player in dealing with playing challenges such as executing the team game plan, completing college work and proving value to the team. Motivation can be defined as “the investigation of the energization and direction of behaviour” (Roberts & Treasure, Citation2012, p. 6). Intrinsic motivation is particularly important as individuals take part in an activity out of interest for the activity itself rather than external reward. To increase intrinsic motivation, three basic psychological needs must be met: competence, autonomy and relatedness (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008). Whereby, autonomy refers to the experience of volition and having control; competence refers to a sense of effectiveness in an environment; and relatedness refers to a sense of belonging and connection with others in a given social context (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Therefore, motivation can be increased through the implementation of psychological skills such as planning, goal-setting, communication, process orientation.

Table 3. Rugby specific list of psychological characteristics and skills of rugby.

Similarly, a confident player can more effectively deal with challenges such as impressing in their first game, performing under pressure, and recovering after a mistake. Confidence can be developed using self-talk, visualisation, reflection, and routines. Furthermore, players must learn to cope with many challenges to their goals of reaching the highest level of their sport including; pressure to perform, expectations from both themselves and family (Beckford et al., Citation2016), the physical challenge of first-team training, having to work hard to prove themselves and forming new relationships with new teammates and coaches (Finn & McKenna, Citation2010). Psychological skills such as concentration, goal setting, peaking under pressure and freedom from worry can help players to better cope with these challenges.

Additionally, the ability to be flexible and adaptable was deemed to be a key feature of resilience for high performing athletes. Resilience can be defined as “the role of mental processes and behaviour in promoting personal assets and protecting an individual from the potential negative effect of stressors” (Fletcher & Sarkar, Citation2012, p. 675). Although differences exist between the two concepts (Gucciardi et al., Citation2008; Sheard, Citation2012), similarities exist between resilience and mental toughness, such as both deal with effectively overcoming and dealing with pressure, challenges and stressors (Cowden et al., Citation2016). Mental toughness is “a personal capacity to produce consistently high levels of subjective or objective performance despite everyday challenges and stressors as well as significant adversities” (Gucciardi et al., Citation2015, p. 28). Resilience and mental toughness are associated with concepts. Therefore, psychological skills such as being able to compartmentalise, organise, plan and cope could help players become more resilient and mentally tough.

Stage related challenges and PSCs

PSCs that are important for success in a talent development environment are sport and context-specific. This research identified a list of PSCs specific to rugby. As players encounter many challenges throughout their time in a rugby talent development environment, a curriculum of PSCs should be deliberately taught to players at the various stages of the talent development pathway to deal with the challenges and reach their potential. PSCs should be developed early so players can implement them as they need them in the future.

illustrates the challenges of rugby pathway stages, i.e., age grade and regional academies, etc., professional academy and professional level, the table outlines the psychological characteristics needed at each stage and the psychological skills that can develop these characteristics. All PSCs needed for development in rugby cannot be taught at any one stage and therefore should be taught over time and across the stages. The information outlined in this table will help sport psychologists and coaches to prioritise which PSCs should be taught and enhanced at each stage. Although new PSCs are taught in later stages, those PSCs taught in earlier stages should be continued to be developed to ensure that the player continues to possess the necessary PSCs for any challenges they may encounter.

Table 4. Psychological skills and characteristics needed for the 15–18 years to professional stages of the rugby development pathway.

Limitations of the current literature and future research

Overall, the literature examining the PSCs important for development and performance in rugby is limited (e.g., Dohme et al., Citation2019; Drew et al., Citation2019). There is a lack of studies that have examined the PSCs of players over time. Furthermore, there is a lack of focus on the PSCs of professional rugby players with the focus on youth teams to academy level within the research. To provide effective psychological support along the talent development pathway, it is crucial to understand these aspects of the professional level to prepare players with the skills to be successful at that level. Therefore, future research should explore professional samples. Of the four exploratory studies identified in this review, only one focused on the players’ perceptions of their PSCs (Holland et al., Citation2010). Therefore, although it is suggested that a curriculum of psychological skills should be taught to rugby players across the talent development pathway (Taylor & Collins, Citation2019), more player-focused research is needed to identify the PSCs important across the participation levels.

With 10 papers included and identified in this review, it would suggest that there is still an absence of evidence in this area. Therefore, an opportunity exists for future research to strengthen the evidence for psychological training and support in rugby. Although the impact of psychological training and support can be examined for many potential challenges and stressors, maybe the most relevant one currently is the psychological impact of Covid-19 restrictions on players. Research needs to examine the psychological impact on players of new challenges such as health concerns, social distancing, limited training and game time and lack of crowd attendance at games. Also, research needs to be conducted to examine potential ways to assist players in dealing with these challenges.

Furthermore, research examining psychological support in rugby has several limitations that need to be addressed. Firstly, even though our aim was to highlight PSCs that have been specifically identified with rugby populations (Larsen et al., Citation2012); some studies examined a variety of sports (e.g., Finn & McKenna, Citation2010; Taylor & Collins, Citation2019). This focus on multiple sports highlights that rugby specific research is limited, and future research should take this into consideration. Furthermore, previous research has been characterised by a preponderance of studies examining the retrospective perceptions of coaches (e.g., Hill et al., Citation2015; Taylor & Collins, Citation2019; Woodcock et al., Citation2011). The use of retrospective methods is a potential limitation as what individuals recall may be inaccurate. Retrospective interviews are dependent on the memories of participants and can, therefore, lack objectivity (Taylor et al., Citation2017). Therefore, research must gather information from prospective methods such as measuring athletes’ psychological characteristics over a period of time.

Longitudinal studies would be very advantageous here and would provide a complete view of the challenges that players face and the PSCs that contribute to success across the talent development pathway (Abbott & Collins, Citation2004; Collins et al., Citation2016; Vaeyens et al., Citation2009; Vaeyens et al., Citation2008) and to the professional level. A further pressing issue that needs to be addressed is how PSCs can help players negotiate through the academy and transition to professional level as these are critical stages in development (Mills et al., Citation2012). Even though previous research, (e.g., Finn & McKenna, Citation2010) has highlighted this period as a potentially difficult one, it has received very little attention in the literature. The research identified in this review that studied the academy period was not solely focused on rugby and examined the perceptions of coaches rather than players.

Although this review has identified a wide range of psychological characteristics that are important for development and performance in rugby, more attention needs to be given to the psychological skills that can enhance or develop these characteristics (Dohme et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, future research should examine whether an educational and training programme based on the PSCs identified in this review would have positive effects on players navigating the talent development pathway to professional rugby.

The current review also has several limitations that we must consider. Conducting a narrative review instead of a systematic review could be considered as a limitation as narrative reviews are viewed as less objective than a systematic review. As mentioned in the method section to ensure objectivity the search and inclusion/exclusion strategies were outlined. Although systematic reviews are currently viewed as superior to narrative reviews, Greenhalgh et al. (Citation2018) have suggested that systematic reviews are not superior but rather systematic and narrative reviews have different purposes and should be seen as complementary. The number of papers also reviewed may be viewed as a limitation. However, this highlights the lack of research in this area. The focus on one sport could also be considered a limitation in terms of its generalisability to other sports. However, multisport reviews have been previously conducted and the aim of the review was to examine the PSCs needed for development specifically in rugby as it is a sport that has been less researched but one in which players encounter many challenges. Furthermore, the reason for conducting the review on one sport is based on the notion that PSCs needed for development are context and sport specific (Larsen et al., Citation2012).

Conclusion

A wide range of PSCs that contribute to the development and performance of rugby players at age grade, academy, and professional level were identified in this review. Furthermore, this review provided a rugby and pathway stage specific list of PSCs that could inform the psychological training and support provided to rugby players at the different stages of their development pathway. As players progress through their talent development pathway they encounter many challenges. A curriculum of PSCs should be deliberately taught to players at the various stages of the talent development pathway to deal with these challenges and assist players in reaching their potential. A rugby specific list of PSCs were identified in this review which can inform the psychological skills training and support of players. Furthermore, the challenges of rugby pathway stages, the psychological characteristics needed at each stage and the psychological skills that can develop these characteristics were identified. Players need to possess a range of PSCs including motivation, commitment, coping skills, confidence, focus and self-regulation to navigate their talent development pathway in rugby successfully. Therefore, rugby players need to be exposed to and taught a wide range of psychological skills so they can develop the skills and characteristics to be able to deal with the challenges they face and reach their potential.

Overall, the existing literature examining the PSCs important for development and performance in rugby is limited. Therefore, an opportunity exists for future research to strengthen the evidence for psychological training and support in rugby. Specifically, there is a lack of studies that have examined the PSCs of players over time. Also, there is a lack of focus on the PSCs of professional rugby players with the focus on youth teams to academy level within the research. Therefore, future research should explore professional samples. Previous research has focused on the perceptions of coaches. Therefore, more player-focused research is needed to identify the PSCs important across the participation levels.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

References

- Abbott, A., & Collins, D. (2004). Eliminating the dichotomy between theory and practice in talent identification and development: Considering the role of psychology. Journal of Sports Sciences, 22(5), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410410001675324

- Baker, J., Devitt, B., Green, J., & McCarthy, C. (2013). Concussion among under 20 rugby union players in Ireland: Incidence, attitudes and knowledge. Irish Journal of Medical Science, 182(1), 121–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-012-0846-1

- Beckford, T. S., Poudevigne, M., Irving, R. R., & Golden, K. D. (2016). Mental toughness and coping skills in Male sprinters. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 11(3), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.14198/jhse.2016.113.01

- Bitchell, C. L., Mathema, P., & Moore, I. S. (2020). Four-year match injury surveillance in male Welsh professional rugby union teams. Physical Therapy in Sport, 42, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2019.12.001

- Carson, F., & Polman, R. C. J. (2017). Self-determined motivation in rehabilitating professional rugby union players. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-016-0065-6

- Casserly, N., Neville, R., Ditroilo, M., & Grainger, A. (2019). Longitudinal changes in the physical development of Elite Adolescent rugby union players: Effect of playing position and body mass change. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 15(4), 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2019-0154.

- Collins, D., MacNamara, Á, & Cruickshank, A. (2019). Research and practice in talent identification and development—some Thoughts on the state of play. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(3), 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1475430

- Collins, D., Macnamara, A., & McCarthy, N. (2016). Super champions, champions, and almosts: Important differences and commonalities on the rocky road [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(2009), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02009.

- Corrado, D., Murgia, M., & Freda, A. (2014). Attentional focus and mental skills in senior and junior professional rugby union players. Sport Sciences for Health, 10(2), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-014-0177-x

- Cowden, R. G., Meyer-Weitz, A., & Oppong Asante, K. (2016). Mental toughness in competitive tennis: Relationships with Resilience and stress. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 320. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00320

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 49(3), 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012801. Social Psychology and Self-Determination Theory: A Canadian Contribution/Psychologie sociale et Théorie de l’autodétermination: Une contribution canadienne.

- Didymus, F. F., & Backhouse, S. H. (2020). Coping by doping?A qualitative inquiry into permitted and prohibited substance use in competitive rugby. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 49, 101680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101680.

- Dohme, L., Backhouse, S., Piggott, D., & Morgan, G. (2016). Categorizing and defining popular psychological terms used within the youth athlete talent development literature: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 134–163. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2016.1185451.

- Dohme, L.-C., Piggott, D., Backhouse, S., & Morgan, G. (2019). Psychological skills and characteristics Facilitative of youth athletes’ development: A systematic review. The Sport Psychologist, 33(4), 261–275. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2018-0014

- Drew, K., Morris, R., Tod, D., & Eubank, M. (2019). A meta-study of qualitative research on the junior-to-senior transition in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, 101556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101556.

- Finn, J., & McKenna, J. (2010). Coping with academy-to-first-team transitions in elite English male team sports: The coaches’ perspective. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 5(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1260/1747-9541.5.2.257

- Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2012). A grounded theory of psychological resilience in Olympic champions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(5), 669–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.04.007

- Gagné, F. (2010). Motivation within the DMGT 2.0 framework. High Ability Studies, 21(2), 81–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2010.525341

- Gledhill, A., & Harwood, C. (2015). A holistic perspective on career development in UK female soccer players: A negative case analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 21, 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.04.003

- Gouttebarge, V, Hopley, P, Kerkhoffs, G., Verhagen, E, Viljoen, W., Wylleman, P., & Lambert, M. (2018). A 12-month prospective cohort study of symptoms of common mental disorders among professional rugby players. European Journal of Sport Science, 18(7), 1004–1012.

- Greenhalgh, T., Thorne, S., & Malterud, K. (2018). Time to challenge the spurious hierarchy of systematic over narrative reviews?. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 48(6), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.12931.

- Gucciardi, D. F., Gordon, S., & Dimmock, J. A. (2008). Towards an understanding of mental toughness in Australian football. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(3), 261–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200801998556

- Gucciardi, D. F., Hanton, S., Gordon, S., Mallett, C. J., & Temby, P. (2015). The concept of mental toughness: Tests of dimensionality, nomological network, and traitness. Journal of Personality, 83(1), 26–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12079

- Hill, A., & Appleton, P. (2011). The predictive ability of the frequency of perfectionistic cognitions, self-oriented perfectionism, and socially prescribed perfectionism in relation to symptoms of burnout in youth rugby players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 29(7), 695–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2010.551216

- Hill, A., Macnamara, A., & Collins, D. (2015). Psychobehaviorally based features of effective talent development in rugby union: A Coach’s perspective. The Sport Psychologist, 29(3), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2014-0103

- Hodge, K., Henry, G., & Smith, W. (2014). A case study of excellence in elite sport: Motivational climate in a world champion team. The Sport Psychologist, 28(1), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2013-0037

- Hodge, K., Lonsdale, C., & Ng, J. Y. Y. (2008a). Burnout in elite rugby: Relationships with basic psychological needs fulfilment. Journal of Sports Sciences, 26(8), 835–844. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410701784525

- Hodge, K., Lonsdale, C. S., & McKenzie, A. (2008b). Thinking rugby: Using sport psychology to improve rugby performance. In J. Dosil (Ed.), (pp. 183–209). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470713174.ch9

- Holland, M. J. G., Woodcock, C., Cumming, J., & Duda, J. L. (2010). Mental qualities and employed mental techniques of young elite team sport athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 4(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.4.1.19

- Holt, N. L., & Mitchell, T. (2006). Talent development in English professional soccer. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 37(2/3), 77–98.

- Hudson, J., Males, J. R., & Kerr, J. H. (2016). Reversal theory-based sport and exercise research: A systematic/narrative review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 27, 168–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.08.008

- Jones, B., Weaving, D., Tee, J., Darrall-Jones, J., Weakley, J., Phibbs, P., Read, D., Roe, G., Hendricks, S., & Till, K. (2018). Bigger, stronger, faster, fitter: The differences in physical qualities of school and academy rugby union players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(21), 2399–2404. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1458589.

- Larsen, C., Alfermann, D., & Christensen, M. (2012). Psychosocial skills in a youth soccer academy: A holistic ecological perspective. Sport Science Review, 21(3/4), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10237-012-0010-x

- Macnamara, A., Button, A., & Collins, D. (2010a). The role of psychological characteristics in facilitating the pathway to elite performance part 1: Identifying mental skills and behaviors. The Sport Psychologist, 24(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.24.1.52

- Macnamara, A., Button, A., & Collins, D. (2010b). The role of psychological characteristics in facilitating the pathway to elite performance part 2: Examining environmental and stage-related differences in skills and behaviors. The Sport Psychologist, 24(1), 74–96. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.24.1.74

- Mann, D. L., Dehghansai, N., & Baker, J. (2017). Searching for the elusive gift: Advances in talent identification in sport. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 128–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.016

- McKenna, J., & Thomas, H. (2007). Enduring injustice: A case study of retirement from professional rugby union. Sport, Education and Society, 12(1), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573320601081500

- Mellalieu, S. D. (2017). Sport psychology consulting in professional rugby union in the United Kingdom. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 8(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2017.1299061

- Mills, A., Butt, J., Maynard, I., & Harwood, C. (2012). Identifying factors perceived to influence the development of elite youth football academy players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1593–1604. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.710753

- Nicholls, A. R., Backhouse, S. H., Polman, R. C. J., & McKenna, J. (2009). Stressors and affective states among professional rugby union players. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 19(1), 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2007.00757.x

- Nicholls, A. R., Holt, N. L., Polman, R. C. J., & Bloomfield, J. (2006). Stressors, coping, and coping effectiveness among professional Rugby union players. The Sport Psychologist, 20(3), 314–329. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.20.3.314

- Nicholls, A. R., Mckenna, J., Polman, R. C. J., & Backhouse, S. H. (2011). Overtraining During Preseason: Stress and Negative Affective States Among Professional Rugby Union Players. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 5(3), 211–222.

- Nicholls, A. R., & Polman, R. C. J. (2007). Stressors, Coping, and Coping Effectiveness Among Players from the England Under-18 Rugby Union Team. Journal of Sport Behavior, 30(2), 199–218.

- Palmer-Green, D. S., Stokes, K. A., Fuller, C. W., England, M., Kemp, S. P., & Trewartha, G. (2015). Training activities and injuries in English youth academy and schools rugby union. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 43(2), 475–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546514560337

- Quarrie, K. L., Alsop, J. C., Waller, A. E., Bird, Y. N., Marshall, S. W., & Chalmers, D. J. (2001). The New Zealand rugby injury and performance project. VI. A prospective cohort study of risk factors for injury in rugby union football. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 35(3), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.35.3.157

- Ranson, C., George, J., Rafferty, J., Miles, J., & Moore, I. (2018). Playing surface and UK professional rugby union injury risk. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(21), 2393–2398. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1458588

- Read, D. B., Jones, B., Phibbs, P. J., Roe, G. A. B., Darrall-Jones, J., Weakley, J. J. S., & Till, K. (2018). The physical characteristics of match-play in English schoolboy and academy rugby union. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(6), 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2017.1329546

- Roberts, G. C., & Treasure, D. (2012). Advances in motivation in sport and exercise. Human Kinetics.

- Roberts, S. J., & Fairclough, S. J. (2012). The influence of relative age effects in representative youth rugby union in the north west of england. Asian Journal of Exercise & Sports Science, 9(2), 86–98.

- Sedeaud, A., Marc, A., Schipman, J., Tafflet, M., Hager, J.-P., & Toussaint, J.-F. (2012). How they won Rugby world cup through height, mass and collective experience. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(8), 580–584. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090506

- Sheard, M. (2012). Mental toughness: The mindset behind sporting achievement. Routledge.

- Sheard, M., & Golby, J. (2009). Investigating the ‘rigid persistence paradox’ in professional rugby union football. International Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671895

- Steidl-Müller, L., Hildebrandt, C., Raschner, C., & Müller, E. (2019). Challenges of talent development in alpine ski racing: A narrative review. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(6), 601–612. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2018.1513355

- Taylor, J., & Collins, D. (2019). Shoulda, coulda, didnae—why don't high-potential players make it? The Sport Psychologist, 33(2), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2017-0153

- Taylor, R. D., Collins, D., & Carson, H. J. (2017). Sibling interaction as a facilitator for talent development in sport. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 12(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954117694926

- Till, K., Cobley, S., Morley, D., O’hara, J., Chapman, C., & Cooke, C. (2016). The influence of age, playing position, anthropometry and fitness on career attainment outcomes in rugby league. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(13), 1240–1245. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2015.1105380

- Till, K., Weakley, J., Read, D. B., Phibbs, P., Darrall-Jones, J., Roe, G., Chantler, S., Mellalieu, S., Hislop, M., Stokes, K., Rock, A., & Jones, B. (2020). Applied sport science for male age-grade rugby union in england. SportS Medicine - Open, 6(1), 14–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-020-0236-6

- Tucker, R., Lancaster, S., Davies, P., Street, G., Starling, L., de Coning, C., & Brown, J. (2021). Trends in player body mass at men’s and women’s Rugby world cups: A plateau in body mass and differences in emerging rugby nations. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 7(1), e000885. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2020-000885.

- Vaeyens, R., Gullich, A., Warr, C. R., & Philippaerts, R. (2009). Talent identification and promotion programmes of Olympic athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 27(13), 1367–1380. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410903110974

- Vaeyens, R., Lenoir, M., Williams, A. M., & Philippaerts, R. M. (2008). Talent identification and development programmes in sport: Current models and future directions. Sports Medicine, 38(9), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200838090-00001

- Wilson, K., Hardy, L., & Harwood, C. (2006). Investigating the Relationship Between Achievement Goals and Process Goals in Rugby Union Players. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 18(4), 297–311.

- Wood, D. J., Coughlan, G. F., & Delahunt, E. (2018). Fitness profiles of elite adolescent Irish rugby union players. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 32(1), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0000000000001694

- Woodcock, C., Holland, M. J. G., Duda, J. L., & Cumming, J. (2011). Psychological qualities of elite adolescent Rugby players: Parents, coaches, and Sport administration staff perceptions and Supporting roles. The Sport Psychologist, 25(4), 411–443. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.25.4.411

- World Rugby. (2019). Long-term player development. World Rugby. Retrieved May 5. https://rugbyready.worldrugby.org/?section=56

- World Rugby. (2020). An open game: The story of how Rugby union turned professional. World Rugby. Retrieved October 21. https://www.rugbyworldcup.com/2019/news/582543

- World Rugby. (2021). World review a year in review. World Rugby. Retrieved May 1. https://www.world.rugby/organisation/about-us/annual-reports