ABSTRACT

Why does group loyalty sometimes take the form of cooperation or peaceful competition with rival groups and, at other times, violent outgroup hostility? We approached this question using online surveys and an experimental manipulation with British soccer fans. Identity fusion (a visceral sense of “oneness” with the group) is known to motivate strong forms of pro-group action, both peaceful and violent. We identified three crucial factors that influence fused supporters’ intergroup behaviours: age, gender, and exposure to out-group threat. Intergroup behaviours included ingroup altruism (e.g., giving one’s time, or emotional/financial support), barrier-crossing altruism (altruistic acts toward rival fan groups), and outgroup hostility (e.g., insulting, spitting at, or physically attacking). Overall, fused fans were more hostile towards outgroups than were weakly fused fans, but they prioritised ingroup altruism over outgroup hostility, and were most likely to report high levels of barrier-crossing altruism. Older fused fans desired future outgroup hostility only under high threat conditions. A clearer understanding of the factors that modulate these different behaviours is a crucial first step in devising more effective ways of reducing intergroup hostility and, crucially, of channelling extreme forms of group alignment into peaceful forms of prosocial action.

In 2020, Simon Dobbins, a Cambridge United fan from the UK, died from the brain injuries he sustained five years previously from an attack by a group of rival Sunderland fans that left him unable to walk or talk unaided. In the same year, Fans Supporting Foodbanks, a network of fans from across the Liverpool area’s clubs and beyond, launched a mobile community pantry service to tackle food poverty. What motivates some individuals to fight or even kill in the name of their group, while others provide time and resources to care for group members, and at times, people outside their immediate group (including members of rival groups), in peaceful ways?

Though there are many impediments to directly studying the psychological causes of violent conflict, including risks to the physical safety of researchers and the many ethical challenges of manipulating potential predictor variables (Wilson & Whitehouse, Citation2016), there are unique contexts in which studies are possible. Although the specific group norms that influence pro-group behaviours vary widely between groups, the sphere of extreme soccer fandom provides a relatively safe, accessible, and worldwide population for investigating some of these issues. Previous studies suggest that the group alignment dynamics found among soccer fans are no different from those found among many other groups, from hard-line religious fundamentalists (Kavanagh et al., Citation2020) to postpartum mothers (Tasuji et al., Citation2020). For this reason, soccer fandom provides a valuable participant pool of highly fused groups, embroiled in long-term and often violent rivalries with other such groups, for testing theories about the psychological drivers of intergroup conflict.

Traditionally, the psychological literature on intergroup conflict has been strongly influenced by social identity theory (SIT), which emphasises the link between ingroup favouritism and outgroup derogation (Tajfel et al., Citation1979). Moderating factors that influence variations in outgroup hostility, such as shared goals, perceptions of the outgroup’s homogeneity or motivation and social complexity, have since been incorporated into SIT showing that ingroup favouritism does not necessarily lead to outgroup derogation (Brewer, Citation2001; Citation2007). Socio-economic status is a particularly important moderating factor in the source of inter-group conflicts, relating to economic resources, values, power, or a combination of these (Katz, Citation1965). However, certain extreme forms of pro-group action, such as violent self-sacrifice, may not be explained by identification alone (Whitehouse, Citation2018), and accounting for the more “virulent” forms of outgroup hostility also remains a challenge (Böhm et al., Citation2020). This paper seeks to help us understand this more pernicious hostility in relation to the key moderators of age and gender.

A relatively new approach comes from identity fusion theory, according to which there is indeed a common underlying driver in many kinds of intergroup conflict (Swann et al., Citation2009; Swann et al., Citation2012), which is fuelled by ingroup causes, specifically the fusion of personal and group identities (Bortolini et al., Citation2018; Swann et al., Citation2010a). Whereas SIT emphasises a hydraulic relationship between personal and group identities (making the one salient makes the other less so), identity fusion entails a synergistic interplay between personal and group identities (Swann & Buhrmester, Citation2015). For a highly fused individual, the fusion target (be it a group, another individual, a value etc.) taps into the agentic self, motivating exceptionally potent forms of pro-group action and self-sacrifice (Gómez et al., Citation2020; Swann et al., Citation2012). At the same time, with identity fusion, group members are perceived as personal and unique, as opposed to depersonalised or prototypical as is the case with identification.

Fusion and pro-group action

Much of the literature has focused on the close relationship between identity fusion and willingness to fight and even die for the group (Bortolini et al., Citation2018; Swann et al., Citation2010b). Using a variety of trolley dilemmas, participants from dozens of countries were asked to what lengths they would go to defend their group, including how willing they would be to jump in front of a train to save other group members, (Swann et al., Citation2014a; Whitehouse et al., Citation2017). In addition to self-reported results, there is increasing evidence of actual rather than aspirational extreme behavioural outcomes. This includes studies working with samples that are harder to reach than ordinary citizens, who are unlikely to be faced with decisions of life and death with regards to sacrifice for their country (Swann et al., Citation2014b), including fighting on the frontlines of civil war or for ISIS (Gómez et al., Citation2017; Whitehouse et al., Citation2014).

Identity fusion has also been studied using soccer fans, including members of Brazilian torcidas organizadas (“hooligan” fan groups) and has been shown to contribute more to violence against rivals than other factors more commonly blamed, such as social maladjustment (Newson et al., Citation2018). In Poland, fans who are highly fused are more willing to undertake collective action to preserve fans’ rights (Besta & Kossakowski, Citation2018). Similarly, research among British fans has demonstrated that identity fusion motivates both lifelong loyalty to a soccer club (Newson et al., Citation2016) and a willingness to sacrifice oneself for other fans (Newson et al., Citation2021).

Much of the fusion literature has been focussed on seemingly intractable conflicts, i.e., those that are perceived to be unsolvable concerning resources or values that appear to be indispensable to a group’s very existence (Bar-Tal, Citation2011). In contrast, intractable conflicts concern low-importance goals that may be partially compatible between parties. In soccer, while disorder may be categorised as a series of tractable conflicts, due to fans fusing with their club and their fan groups, the cumulative effect of rivalries may lead to intractable conflicts, either with traditional rivals or, in some cases, the police.

Fusion and peaceful outcomes

Although identity fusion can fuel violent intergroup conflict, there is also evidence that it can motivate strong forms of peaceful pro group action, such as charitable acts, ranging from monetary gifts to prayers and donations of blood in response to a terrorist atrocity (Buhrmester et al., Citation2015; Buhrmester et al., Citation2018a). Moreover, fusion’s capacity to motivate peaceful forms of prosocial action does not always arise from situations of intergroup conflict but can be rooted in other kinds of shared suffering, even of a vicarious or indirect kind, such as anguish over destruction of wildlife (Buhrmester et al., Citation2018b).

There is also compelling evidence that identity fusion within established groups, such as religious organisations, may be harnessed to support peaceful forms of cooperation to address environmental challenges, as in the need to act on climate change (Whitehouse et al., Citation2013) or to bridge the divisions between groups with histories of conflict (XXX, In Press). This suggests that even in highly fused groups that have traditionally conflicted with rivals, there is the potential to re-channel members’ fusion into more peaceful forms of prosocial action.

In contrast to low identifiers, the “fair weather fans” who bask in their team’s reflected glory, high identifiers are more inclined to stick with their group (Campbell Jr et al., Citation2004; Snyder et al., Citation1986; Wann & Branscombe, Citation1990). However, when these highly identified individuals experience vicarious defeat they may ignore or deny personal effects, instead focussing on group despair. Fused individuals, due to the merging of personal and group identities, internalise both group victory and defeat (Buhrmester et al., Citation2012). Indeed, in soccer, fans of the least successful clubs are consistently more fused and more willing to sacrifice themselves to aid other fans of their club (Newson et al., Citation2021). This resilience, or capitalisation of defeat, among the fused can lead to extraordinarily motivated groups.

Theory suggests that groups organised around charismatic leaders have an increased chance in coordinating in response to group challenges (Grabo & van Vugt, Citation2016). Although the role of leadership in soccer subcultures has been manipulated by the media to create moral panics (Giulianotti & Armstrong, Citation1998), status and hierarchy are central to group dynamics and processes. This may take the form of explicit leadership, as is the case with many Ultras organisations, or implicit leadership regarding more spontaneous violence in other scenes, such as British or Dutch “hooligan” cultures (Marchi et al., Citation2014) where long-standing group membership denotes seniority (Spaaij, Citation2007). In some contexts, such as Western Sydney, soccer cultural spaces offer young people a potentially rare shot at leadership in public life (Knijnik, Citation2018); in other places, such as Egypt, leading Ultras groups is a privilege associated with the educated, middle classes (Jerzak, Citation2013); elsewhere, soccer gang leadership is an extension of complex familial and regional gang ties, as in Romania (Guțu, Citation2018). In the UK, limited capacity for stable leadership, due to leaders’ failure to prioritise the group’s best interests (potentially representing a lack of fusion with the group), has been central to right-wing aligned soccer subcultures not sustaining their recent momentum. This includes the “counter-jihad” movements, the Football Lads Alliance and Democratic Football Lad’s Alliance (Allen, Citation2019).

Clearly, styles of leadership across the terraces vary, with associated cultural differences in fan dynamics. For instance, a tendency for younger or older leaders may relate to different attitudes toward threat. However, some similarities exist. In all cases, soccer leaders have some degree of responsibility for the fan group’s wellbeing, i.e., to propagate the group’s best interests. A seemingly universal in sports fans’ communities is that the chances for women taking leadership roles is low; even the opportunity to attend regular decision-making meetings is limited (Knijnik, Citation2018; Pitti, Citation2019). Women’s involvement in high-prestige activities that may result in leadership may not be banned, but activities perceived to defend the group’s honour such as fighting rivals – be they fans or police – are less socially acceptable for women and may be actively discouraged by men in the group, unless there is at least a partial denial of the women’s femininity (Pitti, Citation2019).

Moderators of identity fusion’s peace-violence spectrum

First, since outgroup threat is thought to be one of the most potent moderators of the relationship between identity fusion and intergroup hostility (Fredman et al., Citation2017; Vázquez et al., Citation2020; Whitehouse, Citation2018), this was a focus variable. Additionally, because men are consistently found to be more associated with violence (Möller-Leimkühler, Citation2018), we also included gender as a moderating variable. Finally, given previous research suggesting that life stages might also impact identity fusion’s effects on violent self-sacrifice (Reese & Whitehouse, Citation2021; Whitehouse et al., Citation2014) and findings that older fans are less aggressive, we also wanted to explore the moderating role of age (Toder-Alon et al., Citation2019).

We also included social dominance orientation (SDO) (Levin et al., Citation2003; Pratto et al., Citation1994) and identification (Brewer, Citation2001; Postmes et al., Citation2013) as potential moderators. Previous research has shown that people with high SDO tend to demonstrate a preference for high status groups (often their own) that forcibly oppress lower status groups (Ho et al., Citation2015), believe the world is competitive rather than cooperative and desire dominance and power over other groups (Duckitt & Sibley, Citation2010), and exhibit higher levels of prejudice against outgroups that threaten their distinct goals (Maunder et al., Citation2019). This research suggests that SDO is an important moderator variable in intergroup relations and will be specifically examined in conjunction with identity fusion in the current study.

Identification has been vigorously investigated as the traditional model from social identity theory, with which to explain pro-group behaviours (Gómez et al., Citation2011; Swann et al., Citation2009; Swann et al., Citation2012). Researchers have specifically examined identity fusion and identification among soccer fans and found fusion to be a stronger predictor of extreme, hostile outcomes than identification (Bortolini et al., Citation2018; White et al., Citation2021). Here we go further, and investigate socially positive behaviours towards soccer fans from rival clubs – could it be that identification better explains personally costly behaviour towards outgroups than identity fusion or will fusion trump identification here too?

Present studies

In addition to confirming the relationship between identity fusion and prosocial behaviours, we also advance previous research by: (1) measuring reports of actual and desired group behaviours; (2) measuring fusion to one’s soccer club, fellow fans, or religion, thus moving beyond the confines of national identities; and (3) sampling across groups that condone violence, who may be more likely to encounter situations that feel “life and death” than general populations. Specifically, we examine groups with recent histories of intergroup hostility (i.e., soccer fans), and rigorously test whether potential moderating variables and covariates account for the relationship between identity fusion and pro-group action. We propose that fused individuals will behave in ways they perceive will best benefit the group, which will account for the substantial variability we find among fused groups. We investigate the role of three such factors that we believed would influence the relationship between fusion and self-sacrificial behaviours: threat, gender, and age.

Statistical analyses

Data were analysed using JASP. Two-tailed significance is reported in all cases. Adequate sample sizes were determined using a priori power analyses in G*power for anticipated small to medium effects (Faul et al., Citation2009). Data not meeting assumption criteria for analyses (e.g., non-normal distributions) were explicitly identified and further analyses were run where necessary. We found some correlations between our key variables, importantly however, multicollinearity did not appear to be a problem (see Tables SM1 and SM8). We excluded participants reporting a gender other than male or female for analyses including gender, due to the extremely small numbers of participants (n < 3 in each study).

Generalised linear models (GLM) were conducted to explore the effect of fusion to one’s ingroup on the various outcome variables (e.g., self-reported past violence, past and future desired outgroup hostility, and altruistic behaviours). All continuous variables were mean-centred prior to being entered into a model. Across studies, we examined potential moderators, i.e., age and gender, by adding the interaction terms between identity fusion and each moderator to the model.

In Study 1 we manipulated threat (randomly assigned low vs. high threat conditions), and this moderator’s interaction term with identity fusion was also added to relevant models. Given that no specific hypotheses were made about interaction effects, where non-significant interactions emerged, these interactions were removed from the final model for clarity. The results were unchanged when the non-significant interactions were retained. We also examined whether identification with the ingroup and SDO were better predictors of the outcome variables than identity fusion (and whether identity fusion remained a significant predictor while controlling for identification and SDO) by adding these variables to alternative regression models.

Study 1

We recruited 500 participants via Prolific, an online participant recruitment service. Filters enabled us to select participants who watched soccer, lived in the UK, and were over 18. Data for both studies are available at: https://osf.io/ndyq7/?view_only=664a0a6684514afab0bcfdd027252bde. Ethical approval was granted by the School of Anthropology and Museum Ethnography Research Ethics Committee (SAME REC) at the University of Oxford (SAME_C1A_20_005).

Sample

Two manipulation checks were included, both of which were failed by three participants who were excluded, leaving n = 497 (M age = 38.55, SD = 12.24). Just over half the participants were men (55.24% men; 44.35% women). Participants who chose not to report their gender were excluded from gender analyses (n = 2). Most participants reported being White British or White Other (87%), then Asian/Asian British (7%), Black/Black British (3%), and mixed (2%). The remaining participants chose not to report their ethnicity. Participants had varied educational backgrounds including, school level (8%), college (30%), university (45%), and post-graduate (17%).

Measures

First, we asked participants what league their club was in and how often they had watched soccer and attended stadia over the last 12 months (less than once a year, once or twice a year, monthly, weekly, daily). We also recorded demographics. Next, we tested identity fusion using the 7-item verbal scale (Gómez et al., Citation2011) with “fellow fans” as the target, including items such as “[My group] is me” and “I am strong because of [my group]”) on a 7-point Likert-type scale. Identification was captured with a single-item measure on a 7-point Likert-type scale (Postmes et al., Citation2013). A single-item measure was considered appropriate considering the need for brevity in the face of an unambiguous construct (Allen et al., Citation2022) and the previously well-documented statistical and theoretical relationships between fusion and identification (Bortolini et al., Citation2018; Swann et al., Citation2009; White et al., Citation2021). SDO was measured with the short SDO scale (Pratto et al., Citation2014) (10-point Likert type scale), including items such as “We should not push for equality for all groups” and “Superior groups should dominate inferior groups”, with higher scores indicating more social dominance. Means for fusion (α = .94) and SDO (α = .72) were used in analyses.

Next, we asked about participants’ altruistic behaviours toward their club or fellow fans over the last 12 months, including hugging them, stopping to help them, emotionally supporting them, giving charitably (e.g., crowdfunding / foodbanks), standing up for them, and spending money on them (α = .80). We then asked about their hostile behaviour toward a rival club or rival fans over the last 12 months, including swearing at them, insulting them, shouting at them, spitting at them, throwing drinks or objects at them, and punching, kicking or otherwise assaulting them (α = .71). Participants could respond never (0), sometimes (1), or often (2). Altruism and hostility variables were created by summing the scores of the past altruism and past hostility items respectively (max = 12).

Experimental Manipulation. Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions and instructed to read a brief vignette taken from the British press, watch a 40–50 second video clip taken from social media, and imagine themselves in the scenario they just watched. In the low threat condition (0), the text was about fans’ spending habits in recent years and the video showed two fan groups walking toward a stadium. In the high threat condition (1), the text was about recent increases in fan violence and the video showed two fan groups engaging in a bloody, organised fight. In a pre-test survey (n = 100), participants reported feeling significantly more threatened, anxious, uneasy, and scared following the high threat condition, compared to the low threat condition (t(98)’s > 9.5, ps < .001). Participants were significantly happier after the low threat condition, compared to the high threat condition (t(98) = −16.54, p < .001).

Future behaviours. Finally, we asked participants about the same altruistic and hostile behaviours as before, framed as “How often will you wish you could do the following … ” over the next 12 months in normal times (as the research was conducted March-April 2020, at the start of the pandemic). The past outgroup hostility score (α = .72) was subtracted from the past ingroup altruism score (α = .84) to create a composite intergroup difference score (high scores indicate a bias toward ingroup altruism; low scores indicate a bias toward outgroup hostility). Max score = 12.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables can be found in SM1.

Outgroup Hostility. First, we included fusion, age, and gender as well as the two-way fusion interactions in a linear regression predicting past outgroup hostility. This revealed that men (β = -.23, p < .001) and highly fused people (β = .50, p < .001) were more violent. There were no interaction effects (Table SM2) so we then ran a final model with just the main effects, revealing that men were significantly more likely to have been hostile toward rivals in the past, compared to females, and that highly fused people were especially hostile, R2 = .17, F(3, 490) = 33.14, p < .001 (). When SDO and identification were added to the model, neither variable was a stronger predictor of past outgroup hostility than fusion, nor were there any significant interactions between these variables and the demographic variables or fusion (see Table SM3).

Table 1. Linear regressions of fans’ self-reported behaviour (main effects only).

Ingroup Altruism. Next, we investigated whether fusion would predict ingroup altruism. As we found no interactions between fusion and gender or age (p’s > .836, see Table SM4), we re-ran the model with MEs only (). Here, both fusion gender were significant, such that highly fused people and women were especially altruistic toward fans of their own club, R2 = .27, F(3, 490) = 60.10, p < .001. Again, we re-ran the model including identification and SDO and found that fusion continued to predict altruism (Table SM5), whereas neither identification nor SDO predicted altruism (ps > .347).

Biases toward Altruism over Hostility. To see whether fused people favoured ingroup altruism or outgroup hostility, we created a composite intergroup difference variable, i.e., we subtracted total outgroup hostility scores from total ingroup altruism scores. High intergroup difference scores reflect a bias toward ingroup altruism, whereas low scores reflect a bias toward outgroup hostility relative to ingroup altruism. There were no gender or age interactions (p’s > .297, Table SM6) so we pursued a model with main effects only. Highly fused people and women were especially likely to have engaged in ingroup altruism in relation to their engagement in outgroup hostility over the last 12 months, R2 = .16, F(3, 490) = 31.09, p < .001 (). In a further model, we also found that people with high SDO scores (β = -.12, p = .003) were more likely to report having engaged in more outgroup hostility relative to ingroup altruism (Table SM7). Fusion and gender retained similar effects in this model and identification was non-significant (p = .433).

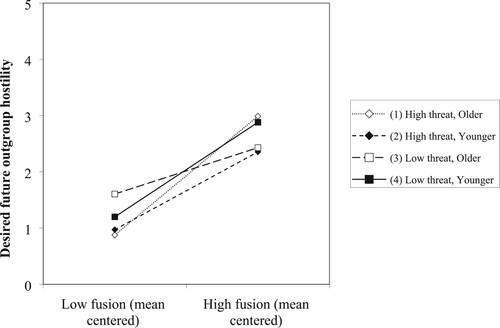

Manipulating Threat. Fusion and threat (low vs. high) were entered into a model with age and gender, as well as all 2- and 3-way fusion interactions in a linear regression predicting desired future outgroup hostility. Highly fused people and men were most likely to desire more hostility toward an outgroup in the future (). There was also a two-way fusion x age interaction, but this was qualified by the threat x fusion x age interaction, R2 = .15, F(11, 481) = 7.44, p < .001. The three-way interaction suggests that while young, fused people were more likely to desire harming their rivals, regardless of threat, older fused people only desired outgroup hostility under high threat conditions (). Fusion appeared to play a special role here, as replacing it with identification or SDO resulted in weak or non-significant interaction effects (p’s > .042). Men tended to desire more outgroup hostility than women, despite being equally fused (p = .103). Nonetheless, it is important to note that the overwhelming majority of participants in both low and high threat conditions wanted to significantly decrease their hostility toward rivals, when comparing participants’ past and desired outgroup hostility, t’s > 15.74 p’s < .001, Cohen’s ds > 1.04.

Table 2. Linear regression with desired outgroup hostility (DV) and age, gender, fusion and threat (IVs).

Discussion

We found that highly fused fans were significantly more likely than weakly fused fans to report having engaged in hostile behaviour towards rival fans in the past. In support of previous research, identity fusion explained outgroup hostility better than identification (Bortolini et al., Citation2018; Swann et al., Citation2009; White et al., Citation2021). A novel variable in our analysis was SDO. Despite the association between SDO and forcible oppression, a preference for dominance over power, and prejudice (Duckitt & Sibley, Citation2010; Ho et al., Citation2015; Maunder et al., Citation2019), we found that SDO had little impact on outgroup hostility when considering identity fusion. This may be because SDO is exclusively focussed on a group-level, rather than integrating the personal self like identity fusion.

Consistent with the literature, highly fused people tended to report more ingroup altruism than weakly fused people (Buhrmester et al., Citation2015; Buhrmester et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b). In contrast, people with high SDO scores reported less ingroup altruism. This supports the idea that SDO is sensitive to the status of an outgroup and thus a better predictor of outgroup (rather than ingroup) variables (Duckitt, Citation2006).

Men tended to report more past violence than women, but this was not associated with fusion. The higher rates of violence found among men compared to women have well-documented ultimate explanations (e.g., the evolution of coalitional psychology and tribal warfare, and the costs of the former on women’s reproductive histories), as well as proximate explanations (e.g., higher testosterone rates and more aggressive socialisation) (see, e.g., Pinker, Citation2011).

Overall, fused people were more likely to report ingroup altruism than outgroup hostility; similarly, women were more likely to report ingroup altruism than outgroup hostility compared to men, but again there were no fusion x gender interactions. We also found a three-way fusion x age x threat interaction, which suggested that older, highly fused people increased their endorsement of outgroup hostility when under high perceived threat conditions, in contrast to younger fused people who were less affected by the threat manipulation. In Study 2 we sought replication evidence for the outgroup hostility scale and its associations with fusion, identification, and SDO. In a novel take, we also extended the dependent variables to investigate barrier-crossing altruism, i.e., altruism toward rivals.

Study 2

We recruited 496 participants from Prolific with the same filters in place as Study 2. We did not allow participants to take part in both Studies 1 and 2, i.e., those with Prolific user Ids appearing in Study 1 were excluded from taking Study 2.

Sample

Two manipulation checks were included, both of which were failed by two participants who were consequently excluded. A further 64 were excluded due to missing data (i.e., they only completed basic demographic data), leaving 432 responses (M age = 38.36, SD = 13.57). The majority were were men (71% men; 29% women). Participants who chose not to report their gender were excluded from gender analyses (n = 2).

Measures

Fusion to fellow fans (α = .95), identification, and SDO (α = .75) were measured as per Study 1. We also asked participants demographic questions, and questions about their fan-based behaviours over the last 12 months. First, we sought to replicate Study 1 and asked about outgroup hostility (rude gestures, spitting at, throwing things at, damaging property, and physically harming: α = .43) and ingroup altruism (smiling, helping, charitable giving, standing up for, spending money on: α = .77). Next, we investigated barrier-crossing altruism, by using the same ingroup altruism measures with rivals as the target (α = .77).

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables can be found in SM8. We found replication evidence for the association between fusion and ingroup altruism / outgroup hostility from Study 1 in a new sample of British fans (see Tables SM9-10), i.e., fusion was the strongest predictor of ingroup altruism and outgroup hostility. Next, we investigated how altruistic participants felt toward other fans who would typically be considered rivals to their club, i.e., barrier-crossing altruism. There were no interaction effects between fusion and gender or age (p’s > .56) so interaction terms were excluded from the final model. Fused people (β = .19, p < .001) and women (β = .10, p = .035) tended to report being more barrier-crossing altruism (altruism to rival fans), R2 = .06, F(3, 447) = 9.52, p < .001. There was a trend for younger people to report more barrier-crossing altruism, but this was not significant (β = -.09, p = .056) Even when including SDO and identification in the model, fusion continued to positively predict barrier-crossing altruism (β = .14, p = .034), along with being female (β = .10, p = .038) and young (β = -.10, p = .031), though not as powerfully as SDO negatively predicted barrier-crossing altruism (β = -.13, p = .006), R2 = .07, F(5, 437) = 6.51, p < .001. There was no effect of identification in this last model (p = .197).

Discussion

Study 2 found replication evidence to support Study 1’s finding that fusion was a stronger predictor of both ingroup altruism and outgroup hostility than SDO or identification. However, the outgroup hostility scale was associated with low internal reliability (α < .5), which is concerning and should be addressed with further research. Nonetheless, the ingroup altruism and barrier-crossing altruism scales were demonstrated good internal reliability (α > .7)

Though consistently predicting altruism, identity fusion’s association with self-sacrificial, pro-group behaviour was nuanced and complex. Previous research has found that the prosocial tendencies associated with fusion can be extended beyond the immediate ingroup to a general group or even an outgroup via synchrony (Reddish et al., Citation2016). Here, we found similar results, without the use of a prime. This may be because soccer fans hold in their mind superordinate identities (Murrell & Gaertner, Citation1992), i.e., nested identities comprising their immediate friends they watch soccer with, fans in their fan group, fans of their team, fans of their national team, and all fans everywhere. Though not connected to research on identity fusion, laboratory and field studies suggest that altruism toward outgroups even resumes after previous direct conflict, such as the Bosnian war, given sufficient time (Whitt et al., Citation2021; Whitt & Wilson, Citation2007). We term this form of altruism, “barrier crossing altruism” (Buhrmester et al., Citationin press).

While fused individuals seemed to reach across identities to “bring others into the fold”, people with a high social dominance scores were particularly unlikely to report barrier-crossing altruism. This should be considered when groups of rival fans congregate, particularly at international tournament where multiple identities may be perceived to dominate over rivals (i.e., team and nation), with emphasis around encouraging fused people’s inclusive outlook and interventions aimed at reducing dominance orientation, e.g., via exposure or a focus on individual values (Danso et al., Citation2007; Shook et al., Citation2016).

Women and younger people were more likely to report barrier-crossing altruism than men or older people, which is an important finding for the sports marketing and management literatures. With regards to gender, this supports previous research demonstrating that women tend to behave more altruistically than men when it comes to financial or time-based effort (Simmons & Emanuele, Citation2007) and that women’s intergroup discrimination is not enhanced by outgroup threat (Yuki & Yokota, Citation2009). However, that younger soccer fans tended to be more altruistic than older fans is perhaps culturally specific to soccer (and maybe British soccer), as much research shows that older people tend to behave more altruistically than the young (Sparrow et al., Citation2021).

General discussion

Given the evidence from previous research that identity fusion can motivate either violent or peaceful forms of prosocial action, we set out to explore factors that could direct behaviour one way or the other. This research combined online surveys with fans and experimental manipulation, to investigate the causes of “hooliganism” and intergroup violence. We found a complex interaction between fusion, threat, and age, and consistently found men to report more violence than women. While young, fused people were more likely to desire outgroup hostility, regardless of threat, older fused people only desired outgroup hostility under high threat conditions.

Neither SDO nor identification explained outgroup hostility or ingroup altruism as well as identity fusion. Fusion has consistently out-predicted identification when it comes to extreme behaviours, both those that are societally positive (Buhrmester et al., Citation2015; Buhrmester et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b) and the more hostile or out-right violent kind now well-reported in soccer fandom (Bortolini et al., Citation2018; Newson et al., Citation2018; White et al., Citation2021). Critical here, is that fusion predicts behaviours that best benefit the group. Critically to this research, a sense that pivotal group members or leaders represent the identity of the group is often representative of high levels of perceived fusion between leader and group (Van Dick et al., Citation2019). For instance, evaluations of leaders’ charisma increase post-mortem, especially when the leader was perceived to be fused to the group (Van Dick et al., Citation2019). It may be that SDO is further influenced by leadership styles that encourage dominant social norms. In British soccer at least, the leadership style is not strictly hierarchical beyond seniority based on duration of group membership (Marchi et al., Citation2014), meaning that group norms are less about dominating other groups than they are about protecting one’s own group under conditions of threat.

The counteraction of global problems of inter-group violence, not just in sport, through effective public policy and policing could potentially be achieved by targeting strategies toward discrete age groups who are likely to respond differently to threatening stimuli. For instance, reducing threat among older community leaders could be effective, as highly fused older people were particularly unlikely to desire outgroup hostility unless they were under conditions of threat, when their anticipated behaviour became exceptionally combative.

To thoroughly explore the relation between identity fusion and group norms, on the one hand, and outgroup violence on the other, future studies should investigate more naturalistic and varied threat measures. It is encouraging to note that most soccer fans surveyed wished to reduce their hostile behaviours towards rival fans. Fused people (especially younger people / women) not only reported high levels of altruism towards their fellow fans, but also towards rival fans. Rather than fusion straightforwardly triggering outgroup hostility, these highly bonded individuals can engage in pro-social, as well as destructive, behaviour towards rivals.

The complexity of the relationship between fusion and parochial altruism was evident in the fact that fused individuals, women, and younger participants, reported altruistic behaviour toward other fans who in some contexts would be considered rivals. We refer to this as barrier-crossing altruism. SDO was negatively associated with barrier-crossing altruism – more powerfully than fusion was positively associated with barrier-crossing altruism – and identification was not significantly associated with it at all.

Limitations

This study was conducted with fans of British clubs so the results cannot necessarily be generalised beyond this context due to substantial variety across soccer subcultures. Replication in different cultural contexts are needed to determine how true these findings are, both in other footballing nations and also in non-sporting contexts, such as ethnic or socio-religious conflicts. There are two critical methodological weaknesses that future research should tackle. First, we conducted an online study which may have resulted in an under-representation of outgroup hostility for two reasons: the issue of self-selection leading to more introverted, less open personalities opting to complete online surveys (Valentino et al., Citation2020) and, in turn, these participants being less likely to have engaged in confrontation; and the problem of dis-honesty in self-reporting. We found good internal reliability for all scales, except for the outgroup hostility scale when applied to the Study 2 sample. This warrants further research and the potential exclusion of some items, most likely the more extremely hostile actions which were very rare across the sample and may have skewed the data. As such, the findings should be treated with caution.

Data were gathered at the start of the pandemic, during the first lockdowns in the UK. We encouraged participants to think about their past behaviour “in normal times”, but it is possible that participants were already primed and feeling particularly threatened by outgroups in association with cues of pathogen prevalence and disgust (Meleady et al., Citation2021). This may have accentuated our measures of anticipated outgroup hostility and our threat manipulation. Equally, at this point in the pandemic British sport suspended – with no live matches at a time that would usually have frequent fixtures. This may have made people wistful about soccer culture and promoted the superordinate category of “soccer fan” above “fan of [X] club”, leading to our finding that fusion was strongly associated with barrier-crossing altruism.

Implications and future research

Future research could introduce the Right Wing Authoritarianism scale (e.g., Zakrisson, Citation2005), in conjunction with SDO, to examine far-right extremism and its role in soccer disorder, which may be growing problem across Europe, including the UK (McGlashan, Citation2020). As ever, soccer only holds up a mirror to the attitudes and behaviours of wider society (Newson, Citation2019), but such analyses could be informative for interventions designed to improve intergroup relations and reduce disorder. It may be that where ideological groups are concerned, SDO has a more prominent role that might complement identity fusion more strongly.

Within soccer fandom there are superordinate identity categories: from the fans one regularly watches matches with; to fans of one’s whole team; to fans of one’s national team; to all soccer fans globally. Fans move between these categories, thus shifting their perception of the ingroup (Wenzel et al., Citation2008). Future identity fusion research could explore how fused identities may either compete with, or complement one another to incorporate wider groups, and how this may lead to barrier-crossing altruism (Buhrmester et al., Citationin press).

The moderating or mediating factors that allow for barrier-crossing altruism over outgroup hostility is likely to be a very informative avenue for policy-relevant research. Future research can build on this to develop programmes in which extremists of various kinds are encouraged to harness their pro-group sentiments for peaceful outcomes. For instance, this could take the form of self-policing within groups that have a culture of violence-condoning norms (Stott et al., Citation2019).

A particularly important finding for those working in the soccer industry, those policing soccer, and policy makers involved in managing soccer disorder is that young, fused people (particularly males) may be the most important target to focus on when trying to prevent future aggressive acts and/or violence. This is further supported by prejudice reduction research also showing that males should be targeted (Boccanfuso et al., Citation2021; White et al., Citation2019). Fusion research with fans suggesting that class and socioeconomic status plays little role, at least in comparison to the strength of fusion (Newson et al., Citation2018). In practice, this may translate to targeted advertising campaigns led by clubs to bring young, bonded men “back into the fold”, modelling societally positive group norms, for instance.

This research may also relate to strategies used to curb soccer disorder. For instance, banning orders may be damaging for fans whose identities are deeply embedded in their club – instead, could we find ways to harness these group passions for social good, via community interventions led by clubs, rather than exclusionary tactics led by the police? One way to achieve this may be by creating dual identities that span both individual and superordinate identities, which has been shown to improve intergroup relations (White & Abu-Rayya, Citation2012). In soccer, dual identities could involve, for example cohesion to one’s club (individual identity) and to all soccer fans (superordinate identity). Soccer already uses ritual to tap into superordinate identities (e.g., when groups of rival domestic fans sing the national anthem prior to international matches) so future research could explore rituals that would facilitate such dual identities among risk groups.

Resolving the issue of when fusion leads to peaceful or violent behaviours is crucial not only for effectively managing problems of fan violence and disorder in soccer, but also for addressing a much wider range of contexts in which fusion motivates willingness to fight and die for the group: from interstate warfare to civil unrest, revolution, and suicide terrorism (Gómez et al., Citation2020; Whitehouse, Citation2018). The research reported here provides important insights into these issues in ways that are not only of scientific importance but may also inform more enlightened policy making, through harnessing identity fusion and directing its behavioural outcomes.

Overall, this research suggests that identity fusion motivates people to act in the best interests of their group, whether that takes the form of ingroup altruism, barrier-crossing altruism, or outgroup hostility. Although what constitutes the “best interests” of a group may be difficult to establish, it is in the interests of society at large to develop strategies that channel the existent fusion among sports fans into peaceful rather than violent forms of pro-group action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, C. (2019). The football lads alliance and democratic football lad’s alliance: An insight into the dynamism and diversification of Britain’s counter-jihad movement. Social Movement Studies, 18(5), 639–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2017.1333677

- Allen, M. S., Iliescu, D., & Greiff, S. (2022). Single item measures in psychological science. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(1), 1–5, https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000699

- Bar-Tal, D. (2011). Intergroup conflicts and their resolution: A social psychological perspective. Psychology Press.

- Besta, T., & Kossakowski, R. (2018). Football supporters: Group identity, perception ofin-group and out-group members and pro-group action tendencies. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 272(2), 15-22.

- Boccanfuso, E., White, F. A., & Maunder, R. D. (2021). Reducing transgender stigma via an E-contact intervention. Sex Roles, 84(5-6), 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01171-9

- Böhm, R., Rusch, H., & Baron, J. (2020). The psychology of intergroup conflict: A review of theories and measures. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 178, 947–962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.01.020

- Bortolini, T., Newson, M., Natividade, J., Vázquez, A., & Gómez, Á. (2018). Identity fusion predicts pro-group behaviours: Targeting nationality, religion or football in Brazilian samples. British Journal of Social Psychology, 57(2), 346–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12235

- Brewer, M. B. (2001). Ingroup identification and intergroup conflict. In R. D. Ashmore, L. Jusim, & D. Wilder (Eds.), Social identity, intergroup conflict, and conflict reduction (pp. 17–41). Oxford University Press.

- Brewer, M. B. (2007). The importance of being we: Human nature and intergroup relations. American Psychologist, 62(8), 728–738. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.8.728

- Buhrmester, M., Burnham, D., Johnson, D., Curry, O. S., Macdonald, D., & Whitehouse, H. (2018b). How moments become movements: Shared outrage, group cohesion, and the lion that went viral. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 6, 54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00054

- Buhrmester, M., Fraser, W. T., Lanman, J. A., Whitehouse, H., & Swann, W. B. (2015). When terror hits home: Identity fused Americans who saw Boston bombing victims as “family” provided aid. Self and Identity, 14(3), 253–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2014.992465

- Buhrmester, M., Newson, M., Vázquez, A., Hattori, W. T., & Whitehouse, H. (2018a). Win at any cost: Identity fusion, group essence, and maximizing ingroup advantage. Self and Identity, 17(5), 500–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1452788

- Buhrmester, M. B., Cowan, M., & Whitehouse, H. (In Press). What motivates barrier-crossing leaders? New England Journal of Public Policy.

- Buhrmester, M. D., Gómez, Á, Brooks, M. L., Morales, J. F., Fernández, S., & Swann Jr, W. B. (2012). My group's fate is my fate: Identity-fused Americans and Spaniards link personal life quality to outcome of 2008 elections. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 34(6), 527–533. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.732825

- Campbell Jr, R. M., Aiken, D., & Kent, A. (2004). Beyond BIRGing and CORFing: Continuing the exploration of fan behavior. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13(3), 151–157.

- Danso, H. A., Sedlovskaya, A., & Suanda, S. H. (2007). Perceptions of immigrants: Modifying the attitudes of individuals higher in social dominance orientation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(8), 1113–1123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207301015

- Duckitt, J. (2006). Differential effects of right wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on outgroup attitudes and their mediation by threat from and competitiveness to outgroups. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(5), 684–696.

- Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, ideology, prejudice, and politics: A dual-process motivational model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861–1894. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00672.x

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Fredman, L., Bastian, B., & Swann Jr, W. (2017). God or country? Fusion with judaism predicts desire for retaliation following Palestinian stabbing intifada. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(8), 882–887. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617693059

- Giulianotti, R., & Armstrong, G. (1998). Ungentlemanly conduct: Football hooligans, the media and the construction of notoriety. Football Studies, 1(2), 4–33.

- Gómez, Á, Brooks, M. L., Buhrmester, M. D., Vázquez, A., Jetten, J., & Swann Jr, W. B. (2011). On the nature of identity fusion: Insights into the construct and a new measure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(5), 918–933. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022642

- Gómez, Á, Chinchilla, J., Vázquez, A., López-Rodríguez, L., Paredes, B., & Martínez, M. (2020). Recent advances, misconceptions, untested assumptions, and future research agenda for identity fusion theory. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 14(6), e12531. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12531

- Gómez, Á, López-Rodríguez, L., Sheikh, H., Ginges, J., Wilson, L., Waziri, H., Vázquez, A., Davis, R., & Atran, S. (2017). The devoted actor’s will to fight and the spiritual dimension of human conflict. Nature Human Behaviour, 1(9), 673–679. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0193-3

- Grabo, A., & van Vugt, M. (2016). Charismatic leadership and the evolution of cooperation. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(5), 399–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.03.005

- Guțu, D. (2018). World going one way, people another: Ultras football gangs’ survival networks and clientelism in post-socialist Romania. Soccer & Society, 19(3), 337–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2017.1333677

- Ho, A. K., et al. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO₇ scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1003. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000033

- Jerzak, C. T. (2013). Ultras in Egypt: State, revolution, and the power of public space. Interface: A Journal for and About Social Movements, 5(2), 240–262.

- Katz, D. (1965). Nationalism and strategies of international conflict resolution. In H.C. Kelman (Ed.), International Behavior: A Social-Psychological Analysis (pp. 356–390). New York: Holt, Rinehartand Winston.

- Kavanagh, C., Kapitány, R., Putra, I. E., & Whitehouse, H. (2020). Exploring the pathways between transformative group experiences and identity fusion. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1172. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01172

- Knijnik, J. (2018). Social agency and football fandom: The cultural pedagogies of the Western Sydney ultras. Sport in Society, 21(6), 946–959. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1300394

- Levin, S., Henry, P. J., Pratto, F., & Sidanius, J. (2003). Social dominance and social identity in Lebanon: Implications for support of violence against the west. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 6(4), 353–368. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302030064003

- Marchi, V., Dionesalvi, C., & Pedrini, R. (2014). Il derby del bambino morto: Violenza e ordine pubblico nel calcio. Alegre.

- Maunder, R. D., Day, S. C., & White, F. A. (2019). The benefit of contact for prejudice-prone individuals: The type of stigmatized outgroup matters. The Journal of Social Psychology, 160(1), 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2019.1601608

- McGlashan, M. (2020). Collective identity and discourse practice in the followership of the Football Lads Alliance on Twitter. Discourse & Society, 31(3), 307–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926519889128

- Meleady, R., Hodson, G., & Earle, M. (2021). Person and situation effects in predicting outgroup prejudice and avoidance during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 172, 110593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110593

- Möller-Leimkühler, A. M. (2018). Why is terrorism a man’s business? CNS Spectrums, 23(2), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1092852917000438

- Murrell, A. J., & Gaertner, S. L. (1992). Cohesion and sport team effectiveness: The benefit of a common group identity. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 16(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/019372359201600101

- Newson, M. (2019). Football, fan violence, and identity fusion. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 54(4), 431–444.

- Newson, M., Bortolini, T., Buhrmester, M., da Silva, S., Acquino, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Brazil's football warriors: Social bonding and inter-group violence. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39(6), 675–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2018.06.010

- Newson, M., Buhrmester, M., & Whitehouse, H. (2016). Explaining lifelong loyalty: The role of identity fusion and self-shaping group events. PLoS ONE, 11(8), e0160427. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160427

- Newson, M., Buhrmester, M., & Whitehouse, H. (2021). United in defeat: Shared suffering and group bonding among football fans. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1866650

- Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature: The decline of violence in history and its causes. London: Penguin.

- Pitti, I. (2019). Being women in a male preserve: An ethnography of female football ultras. Journal of Gender Studies, 28(3), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2018.1443803

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12006

- Pratto, F., Saguy, T., Stewart, A., Morselli, D., Foels, R., Aiello, A., Aranda, M., Cidam, A., Chryssochoou, X., Durreheim, K., Eicher, V., Licata, L., Liu, J. H., Liu, L., Meyer, I., Muldoon, O., Papastamou, S., Petrovic, N., Prati, F.…Sweetman, J., et al. (2014). Attitudes toward Arab ascendance: Israeli and global perspectives. Psychological Science, 25(1), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613497021

- Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741–763 https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741

- Reddish, P., Tong, E. M., Jong, J., Lanman, J. A., & Whitehouse, H. (2016). Collective synchrony increases prosociality towards non-performers and outgroup members. British Journal of Social Psychology, 55(4), 722–738. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12165

- Reese, E., & Whitehouse, H. (2021). The development of identity fusion. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(6), 1398–1411. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620968761

- Shook, N. J., Hopkins, P. D., & Koech, J. M. (2016). The effect of intergroup contact on secondary group attitudes and social dominance orientation. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(3), 328–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215572266

- Simmons, W. O., & Emanuele, R. (2007). Male-female giving differentials: Are women more altruistic? Journal of Economic Studies, 34(6), 534–550.

- Snyder, C. R., Lassegard, M., & Ford, C. E. (1986). Distancing after group success and failure: Basking in reflected glory and cutting off reflected failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(2), 382–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.2.382

- Spaaij, R. (2007). Football hooliganism in the Netherlands: Patterns of continuity and change. Soccer & Society, 8(2-3), 316–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970701224566

- Sparrow, E. P., Swirsky, L. T., Kudus, F., & Spaniol, J. (2021). Aging and altruism: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 36(1), 49. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000447

- Stott, C., Pearson, G., & West, O. (2019). Enabling an evidence-based approach to policing football in the UK. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 14(4), 977–994. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay102

- Swann, W., & Buhrmester, M. (2015). Identity fusion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414551363

- Swann, W., Buhrmester, M., Gómez, A., Jetten, J., Bastian, B., Vázquez, A., … Cui, L. (2014a). What makes a group worth dying for? Identity fusion fosters perception of familial ties, promoting self-sacrifice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(6), 912. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036089

- Swann, W., Gómez, Á, Buhrmester, M., López-Rodríguez, L., Jiménez, J., & Vázquez, A. (2014b). Contemplating the ultimate sacrifice: Identity fusion channels pro-group affect, cognition, and moral decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(5), 713. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035809

- Swann, W., Gómez, Á, Dovidio, J., Hart, S., & Jetten, J. (2010b). Dying and killing for one’s group: Identity fusion moderates responses to intergroup versions of the trolley problem. Psychological Science, 21(8), 1176–1183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610376656

- Swann, W., Gómez, Á, Huici, C., Morales, F., & Hixon, G. (2010a). Identity fusion and self-sacrifice: Arousal as a catalyst of pro-group fighting, dying, and helping behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(5), 824–841. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020014

- Swann, W., Gómez, Á, Seyle, C., Morales, F., & Huici, C. (2009). Identity fusion: The interplay of personal and social identities in extreme group behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(5), 995–1011. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013668

- Swann, W., Jetten, J., Gómez, Á, Whitehouse, H., & Bastian, B. (2012). When group membership gets personal: A theory of identity fusion. Psychological Review, 119(3), 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028589

- Tajfel, H., Turner, J. C., Austin, W. G., & Worchel, S. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. Organizational Identity: A Reader, 56(65), 9780203505984-16.

- Tasuji, T., Reese, E., van Mulukom, V., & Whitehouse, H. (2020). Band of mothers: Childbirth as a female bonding experience. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0240175. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0240175

- Toder-Alon, A., Icekson, T., & Shuv-Ami, A. (2019). Team identification and sports fandom as predictors of fan aggression: The moderating role of ageing. Sport Management Review, 22(2), 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.02.002

- Valentino, N. A., Zhirkov, K., Hillygus, D. S., & Guay, B. (2020). The consequences of personality biases in online panels for measuring public opinion. Public Opinion Quarterly, 84(2), 446–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfaa026

- Van Dick, R., Fink, L., Steffens, N. K., Peters, K., & Haslam, S. A. (2019). Attributions of leaders’ charisma increase after their death: The mediating role of identity leadership and identity fusion. Leadership, 15(5), 576–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/1742715018807042

- Vázquez, A., López-Rodríguez, L., Martínez, M., Atran, S., & Gómez, Á. (2020). Threat enhances aggressive inclinations among devoted actors via increase in their relative physical formidability. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 46(10), 1461–1475. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167220907466

- Wann, D. L., & Branscombe, N. R. (1990). Die-hard and fair-weather fans: Effects of identification on BIRGing and CORFing tendencies. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 14(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/019372359001400203

- Wenzel, M., Mummendey, A., & Waldzus, S. (2008). Superordinate identities and intergroup conflict: The ingroup projection model. European Review of Social Psychology, 18(1), 331–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280701728302

- White, F. A., & Abu-Rayya, H. M. (2012). A dual identity-electronic contact (DIEC) experiment promoting short- and long-term intergroup harmony. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(3), 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.01.007

- White, F. A., Newson, M., Verrelli, S., & Whitehouse, H. (2021). Pathways to prejudice and outgroup hostility: Group alignment and intergroup conflict among football fans. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(7), 660–666. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12773

- White, F. A., Verrelli, S., Maunder, R. D., & Kervinen, A. (2019). Using electronic contact to reduce homonegative attitudes, emotions, and behavioral intentions among heterosexual women and men: A contemporary extension of the contact hypothesis. The Journal of Sex Research, 56(9), 1179–1191. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1491943

- Whitehouse, H. (2018). Dying for the group: Towards a general theory of extreme self-sacrifice. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 41, 281–383. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X18000249

- Whitehouse, H., Jong, J., Buhrmester, M., Gomez, A., Bastian, B., Kavanagh, C., … Gavrilets, S. (2017). The evolution of extreme cooperation via shared dysphoric experiences. Nature: Scientfic Reports, 7(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44292

- Whitehouse, H., McQuinn, B., Buhrmester, M., & Swann, W. B. (2014). Brothers in arms: Libyan revolutionaries bond like family. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(50), 17783–17785. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1416284111

- Whitehouse, H., Swann, W., Ingram, G., Prochownik, K., Lanman, J., Waring, T. M., … Johnson, D. (2013). Three wishes for the world (with comment). Cliodynamics: The Journal of Theoretical and Mathematical History, 4(2), 281–323.

- Whitt, S., Wilson, R. K., & Mironova, V. (2021). Inter-group contact and out-group altruism after violence. Journal of Economic Psychology, 86, 102420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2021.102420

- Whitt & Wilson. (2007). The dictator game, fairness and ethnicity in postwar bosnia. American Journal of Political Science, 51(3), 655–668. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00273.x

- Wilson, D. S., & Whitehouse, H. (2016). Developing the field site concept for the study of cultural evolution. Cliodynamics, 7(2), 228–287https://doi.org/10.21237/C7clio7233542.

- Yuki, M., & Yokota, K. (2009). The primal warrior: Outgroup threat priming enhances intergroup discrimination in men but not women. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(1), 271–274. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2008.08.018

- Zakrisson, I. (2005). Construction of a short version of the Right-Wing Authoritarianism (RWA) scale. Personality and individual differences, 39(5), 863–872.