ABSTRACT

The professional tennis tour lifestyle has become increasingly difficult over time. Although the financial strain of tour life has been identified [International Tennis Federation. (2017, March 30). ITF pro circuit review. https://www.itftennis.com/procircuit/about-pro-circuit/player-pathway.aspx], there is a gap in our understanding of the additional lifestyle challenges that professional players face and the potential impact these have on their progression and mental health. Adopting an exploratory case study methodology [Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage.], with “Behind the Racquet”, a social media platform aimed at raising awareness of professional players’ challenges as its case, and theoretically underpinned by [Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.] hierarchy of needs, this study aimed to gain a contextual understanding of these challenges. Using “Behind the Racquet” as the data source provided a unique opportunity to gain authentic, self-reported experiences from a hard-to-reach population. The sample consisted of 65 professional players (33 males, 32 females; age range = 18–46 years; mean age = 27.34 years) from 28 different countries. Players achieved varying levels of success, including being Grand Slam and Olympic champions, ATP, and WTA Top 10 players, and within and outside of the world’s Top 100. Findings illustrated physical and mental fatigue, financial imbalance of the professional system, the social and psychological impact of living a nomadic existence, the weight of expectation, structural-caused instability, and mental illness as key challenges that players experience on the professional tour. These challenges, which inhibit players’ ability to meet basic needs on each level of [Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.] hierarchy of needs, pose concerns to both players’ progression on tour and their mental health.

Each year, thousands of tennis players from around the world compete against each other on the professional tennis circuit (International Tennis Federation (ITF), Citation2020). However, as the most recent ITF Pro Circuit Review has highlighted (ITF, Citation2017), their pursuit of success is not without obstacles. Most notably, there is a considerable financial imbalance on tour, with the top 1% of players having earned 60% and 51% of the prize money distributed on the men’s and women’s tours in 2013, respectively, and only 1.8% of male and 3.1% of female players earning a profit (ITF, Citation2017). This leaves most players competing on the professional tourFootnote1 in varying degrees of financial debt and in danger of prematurely ending their professional pursuit due to an inability to fund the extensive costs. Further, the time taken from earning one’s first professional ranking to reaching the world’s Top 100 has increased from 3.7–4.8 years (men) and 3.4–4.1 years (women) from 2000 to 2013 (ITF, Citation2017), and even further to 5 years (men) and 4.9 years (women) by 2017 (ITF Global Tennis Report, Citation2019), suggesting that additional challenges are at play making the professional tennis tour an increasingly difficult environment to thrive in. While research has identified lifestyle challenges of professional athletes in other sports (Battochio et al., Citation2009, Citation2016; Gordin, Citation2016; Moore, Citation2016; Noblet & Gifford, Citation2002; Ryba et al., Citation2016; Schinke et al., Citation2012), we do not yet sufficiently understand the specific challenges (in addition to the identified financial ones) faced by tennis players in their lifestyle on the professional tour (i.e., lifestyle challenges), nor how these potentially impact upon their mental health and wellbeing. Whilst there is existing literature into players’ transitions into professional tennis (Jensen, Citation2012; Pummell, Citation2008), the knowledge base around lifestyle challenges from these studies is minimal and would benefit from more diverse samples, involving players of both sexes and from a range of nationalities. With regards to mental health and wellbeing, there is limited research to date exploring this area in professional tennis (e.g., Carrasco et al., Citation2013). In addition to adding depth to the academic literature, investigating players’ lifestyle challenges and their impact on mental health and wellbeing can help to inform aspiring players’ preparations for a professional career from both a performance and mental health standpoint.

Understanding the challenges that professional tennis players face on tour is important not just for performance reasons, but for mental health and wellbeing reasons. The developmental period in which tennis players, and athletes in most disciplines, generally reach their peak performance overlaps with the peak onset of mental health disorders in the general population (Jones, Citation2013). It is estimated that 75% of mental health disorders are established by the age of 24 (Kessler et al., Citation2005). When this sensitive developmental period is combined with the unique stressors (i.e., competitive, organisational, and personal) that athletes experience in high-performance environments (Sarkar & Fletcher, Citation2014), elite athletes may be at an increased vulnerability to mental illness compared to the general population (Gucciardi et al., Citation2017). To date, research on mental illness within elite sport has reported prevalence rates between 17% and 47% (Foskett & Longstaff, Citation2018; Gouttebarge et al., Citation2017; Gulliver et al., Citation2015; Schaal et al., Citation2011), which are comparable, and in some cases, higher than the general population rates for young adults estimated to range between 19% and 26% (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2007; Education Policy Institute, Citation2018; Mental Health Foundation, Citation2016). While it has not been substantiated that elite athletes experience higher prevalence of mental illness than the general population, the environmental challenges and age-related risk factors they experience during their sporting careers makes mental illness within the elite sporting world a cause for concern.

The increased focus on mental health within elite sport in recent years is also reflected in position and consensus statements published by major sporting organisations including the International Society of Sport Psychology (Henriksen et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Schinke et al., Citation2018) and the International Olympic Committee (Reardon et al., Citation2019). With considerable research having been undertaken to attempt to quantify and classify the nature and prevalence of mental illness within sport (Gorczynski et al., Citation2017; Rice et al., Citation2016), Henriksen et al. (Citation2020a) recently argued for the importance of focusing on mental health in addition to mental illness and conceptualising mental health as more than simply the absence of mental illness. This argument aligns with Keyes (Citation2005) definition of mental health as being free of mental illness and flourishing with high levels of emotional, psychological, and social well-beingFootnote2, as well as Keyes’ (Citation2002; Citation2005) dual continuum model which views mental health and mental illness as two distinct but related dimensions existing on two separate continua. The model provides a holistic understanding of mental health (Iasiello & Agteren, Citation2020; Uphill et al., Citation2016) by conceptualising flourishing (i.e., high levels of mental health) as being made up of three distinct types of wellbeing (i.e., emotional, psychological, and social), as well as demonstrating how athletes can experience high or low levels of mental health, while simultaneously experiencing either high or low levels of mental illness.

Theoretical underpinning

To explore challenges experienced by professional tennis players, the present study adapted an established theory – Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchy of needs – and used it as an innovative theoretical framework and approach within the sport psychology discipline. The theory continues to be relevant decades after its inception, informing research and applied practice in diverse fields such as education, medicine, and business (e.g., Benson & Dundis, Citation2003; Hale et al., Citation2019; Jerome, Citation2013; Milheim, Citation2012). As a classic theory of motivation, Maslow (Citation1943) posited that four basic sets of needs (i.e., physiological, safety, love and belonging and esteem) must be satisfied for individuals to be motivated to reach maximum human potential (i.e., self-actualisation). While most often visually represented as a pyramid with higher-order needs dependent on lower-order needs, the importance of each level of needs varies from person to person and is not a rigid hierarchy as originally conceptualised (Maslow, Citation1987). Instead, these need levels are more flexible and dynamic, based on contextual factors and individual differences. Thus, this theory is more recently understood as a group of coexisting needs to be satisfied instead of as a hierarchy, with people able to experience higher needs even if the more basic ones are not met.

Only limited sport research has adopted Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Citation1943) as a motivational framework (e.g., Andrew et al., Citation2016; Homan, Citation2021; Nikitina, Citation2021). But, we propose that it would enable a holistic view of the challenges faced on tour by professional players and be well-suited for exploring their mental health and wellbeing. In support, in their study analysing over 60,000 participants across 123 countries, Tay and Diener (Citation2011) found universal needs aligned with Maslow’s theory to increase subjective wellbeing regardless of cultural differences. Further, Crandall et al. (Citation2020) found Maslow’s theory to partially predict and explain baseline rates and changes in adolescent depressive symptoms. Despite this, Maslow’s theory has not yet specifically been applied to understanding athlete mental health. Adopting this theory would provide an insightful look at how the satisfaction or lack thereof of basic human needs can impact both players’ progression on tour and their mental health and wellbeing. The hierarchy of needs also offers a guiding framework for developing interventions to support the wellbeing of professional players through a holistic consideration of their needs and by acknowledging multiple concurrent threats to them (Hale et al., Citation2019).

Study aims

The present study aimed to provide a detailed, contextualised understanding of the lifestyle challenges that professional tennis players face on the professional tour and the potential impact these challenges have on their mental health. This was the first study to investigate the lifestyle challenges of the professional tennis tour within a diverse, international sample. Additionally, it makes a unique theoretical contribution by providing a novel application of Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchy of needs to the sport psychology discipline.

Methods

Design

This study was underpinned by an interpretivist approach consisting of a relativist ontology and a subjectivist epistemology (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). It adopted an exploratory case study methodology (Yin, Citation2017), an approach selected to gain rich insight (Cooper et al., Citation2019) into a previously understudied area. The case study consisted of a single holistic case: Behind the Racquet (BTR) (Citation2021), a social media platform aimed at raising awareness of the challenges that tennis players face on the professional tour. BTR as a case study offered unique opportunities for research into the voice of players, being an authentic, self-reported platform of players’ professional experiences (Paulhus & Vazire, Citation2007). The case study was bounded to understand the challenges that professional players face in their lifestyle on tour. The units of analysis were individual players who contributed to the BTR platform. Theoretically underpinned by Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchy of needs, the study looked to understand the extent to which players’ basic needs were met amidst the challenges they face on the professional tour. With the first researchers’ background in tennis, a reflexive approach to the data analysis process was used (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019).

Data collection

Self-reported narrative data was collected via blog posts from professional tennis players who contributed to BTR. Given the competitive nature of professional tennis, these types of vulnerable narratives are rarely shared, making them an invaluable data source, as well as the case study unique. The data provided an excellent opportunity to gain a self-reported understanding of professional tennis players’ lifestyles, and as such, best answered the study’s research questions of “What challenges do professional tennis players face in their lives on the professional tour?” and “What type of impact do these challenges have on players’ mental health?”.

Blogs provide access to hard-to-reach populations from which the researcher is either geographically or socially removed from (Mann & Stewart, Citation2000; Wilson et al., Citation2015), while offering an authentic, publicly available, low-cost and instantaneous way of collecting a considerable amount of data with the transparency of a built-in audit trail (Hookway, Citation2008; Moravcsik, Citation2014). The use of blogs in academic research is becoming increasingly common (Kurtz et al., Citation2017; Wilkinson & Thelwall, Citation2011) with growing support for its use for data collection purposes in qualitative research in health (Wilson et al., Citation2015) and sport (Brown & Billings, Citation2013; Kavanagh et al., Citation2016). Ethical considerations of blog use, such as informed consent and the public or private nature of information, are increasingly important as they become a more common data source for academic research (Kurtz et al., Citation2017; Wilkinson & Thelwall, Citation2011). In the present study, the Association of Internet Researchers’ (AoIR) recommendations (Ess et al., Citation2002; Markham et al., Citation2012) were followed, which considers blogs as public webpages that can be viewed by anyone (as compared to a private chatroom) and explained that “the greater the acknowledged publicity of the venue, the less obligation there may be to protect individual privacy, confidentiality, right to informed consent, etc.” (Ess et al., Citation2002, p. 5). As informed consent does not apply to published material (e.g., newspapers) and sending participation requests to players who had already consented to sharing their narratives to a popular platform like BTR seen as potentially intrusive (Snee, Citation2013), it was not deemed necessary to obtain additional consent to use these blogs for research purposes. Nonetheless, consent to use the platform (whilst publicly available) was still sought from the founder of BTR (N. Rubin, personal communication, 16 July 2019). Additionally, to ensure trustworthiness of the posts, the first researcher liaised with the platform’s creator to confirm validity checks were in place for the posts selected for inclusion.

Sample

Of the 115 posts uploaded between 19 January 2019 and 31 March 2020, 66 were selected for analysis according to the following inclusion criteria: (a) the post shared players’ experiences unique to their professional career; and (b) the post illustrated experiences which had a psychological impact on the player. The dataset included experiences of 65 professional players (one player had two separate posts), of which 33 were male, and 32 were female. Further details of the sample are provided in . A wide range of achievement levels existed across the dataset, ranging from Grand Slam and Olympic champions to players within the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) and Women’s Tennis Association (WTA) Top 10, and those within and outside of the ATP and WTA Top 100.

Table 1. Sample breakdown.

Data analysis

Data was analysed inductively using reflexive thematic analysis, a flexible process where researchers generate patterns of meaning within their dataset through reflexive and thoughtful consideration of their data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). This approach was adopted due to the exploratory nature of the case study, which aimed to gain a contextual understanding of the beliefs, thoughts, and experiences of professional players. In line with the phases of thematic analysis (Braun et al., Citation2016), the first author began the analysis process by reading and familiarising themselves with the data before embarking on the initial coding process. NVivo 12 was used to organise and code the data. The entire dataset was coded before the codes were subsequently grouped into initial themes. The initial themes were presented to a group of researchers in the university’s sport psychology department (including post graduate students and post-doctoral research fellows) independent from the project where useful discussion on the analysis led to further adaptations to the themes. After this meeting, discussion amongst the authors of this paper led to even further adaptations leading to six themes that more clearly represented how players’ challenges on tour impact their ability to meet their basic needs (Maslow, Citation1943). Involving outside researchers was a collaborative process to help “develop a richer more nuanced reading of the data, rather than seeking a consensus of meaning” (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, p. 594). The steps taken throughout this reflexive thematic analysis led to prolonged engagement with the data and continual reflection and questioning of assumptions that were made in interpreting the data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). For increased trustworthiness of the data, a range of rich quotes were used to exhibit confirmability and authenticity in the report of the findings (Cope, Citation2014).

The analysis was underpinned by the modern discussion on rigour in qualitative research (e.g., Morse, Citation2015; Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). With the first author’s extensive background as a tennis player, both at the collegiate and professional level, this offered the opportunity to harness reflexivity in the analysis in order to complement and enhance the process. Reflexivity was described by Berger (Citation2015) as turning the researcher lens to oneself to recognise and take responsibility for one’s position within the research and the effect this could have on the research process and outcome. Specifically, the first researcher involved “critical friends” who were post-doctoral researchers who had no background in tennis, but expertise in qualitative research, and thematic analysis specifically, to provide a sounding board for ideas and encourage potential alternative explanations of the data throughout the analysis process. This proved particularly vital at the stage where initial themes were developed and a discussion with the critical friends led to an alternative understanding of an important concept, which led to a restructure of a key theme.

Results

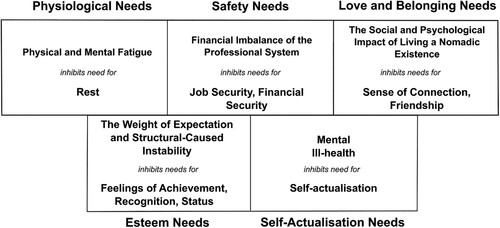

In line with the study’s aims, data analysis led to a deeper and contextualised understanding of the challenges that players face in their lifestyle as professional tennis players. Six themes were developed in the analysis (i.e., Physical and Mental Fatigue, Financial Imbalance of the Professional System, The Social and Psychological Impact of Living a Nomadic Existence, The Weight of Expectation, Structural-Caused Instability and Mental Illness), and these themes and their connection to the levels of Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchy are outlined below.

Physical and mental fatigue (physiological needs)

The weekly travel from one country to another, where players are confronted by different time zones, cultures, foods, languages, and playing conditions, is a major challenge, which leads to physical and mental fatigue and impedes players’ physiological need for rest (Maslow, Citation1943). As Player 1 (male, French), a veteran of the professional tour, explained:

On one side I feel lucky to be able to travel around the world and see different cultures, and on the other side it was just tiring. From New York to Tokyo and then Moscow, in one month, it’s three different worlds that you have to get used to.

The long year of tennis is exhausting. Other sports have two-three months off to use as a break. I understand that other sports may push their players harder during the short seasons but there is no way they are put in the same amount of stressful situations as tennis players are.

Financial imbalance of the professional system (safety needs)

A financial imbalance exists in the professional system and this represents a major barrier to its players. With players at the lower levels of the tour earning far less money than those at the top, yet still personally responsible for the substantial costs of a professional career, navigating a professional career becomes a monumental financial challenge. This impacts players’ safety needs (Maslow, Citation1943) by challenging both their financial and job security. Indeed, the financial stress professional players experience on tour hangs like a dark cloud over their professional existence, leading to doubt over the feasibility of their continued involvement on tour. With the endless expenses of travel, accommodation, equipment and other playing essentials, players must earn as much prize money as possible to offset these costs. As illustrated by Player 3 (male, South African), the precarious nature of this funding is a significant source of stress and leads players to questioning: (a) can they afford to continue; and (b) is it worthwhile for them to do so:

The question always came up, “What am I doing?” I was going week to week, making two or three hundred dollars. Then after taxes it was basically nothing. What am I doing with my life? I am twenty nine now. I don’t have a degree … Other people around my age, who I went to school with, have cars, house, etc … living the less stressful life. They see me and think that I am living this glamorous lifestyle, playing at Wimbledon, but in actuality I was barely surviving paycheck to paycheck.

My dad stopped working to travel with me full time. There was already pressure from not being too wealthy and now my father wasn’t making money … There was a lot of pressure on the whole family to also keep up with the expenses of travel … My mom switched jobs and started to work at home so she had time to look after my brother by herself.

The social and psychological impact of living a nomadic existence (love and belonging needs)

The opportunities to play tournaments in all but one week of the calendar year and the fierce competition to earn ranking points and prize money to move up the ranking system and fund the costs of the professional tour are strong incentives for players to compete in different parts of the world throughout the year. The resulting nomadic existence challenges players’ love and belonging needs (Maslow, Citation1943) by inhibiting their need for sense of connection and friendship. Humans are a social species which require social contact and support to survive and thrive (Seppala et al., Citation2013) and this contributes to their social wellbeing (Keyes, Citation2005). Not meeting these needs in young adulthood while embarking on a professional career can be particularly disorienting for players and may therefore lower their mental health. As Player 6 (female, German) explains, the constant travelling and inability to settle in a geographical location for an extended period makes it difficult to maintain relationships and feel connected with others:

It’s hard to maintain relationships with a boy/girlfriend, with friends … it’s hard not to see your family for long periods because you are rarely home. You miss out on important things that happen in your friends’ lives. It’s your job to be on the road and play.

The weight of expectation (esteem needs)

The journey of becoming a professional tennis player is time-consuming, challenging and includes numerous sacrifices from the player and their families. It is unsurprising that when a player reaches the professional level, the weight of expectation to succeed can negatively impact upon their esteem needs of feelings of achievement, recognition, and status (Maslow, Citation1943). In turn, this may negatively impact on the players’ psychological wellbeing. To remain on the professional tour, players must consistently achieve results and earn the necessary ranking points to maintain or increase their world ranking. This results-focused environment puts thousands of highly motivated and capable players head-to-head and under immense pressure to achieve. This is seen through the experiences of Player 10 (female, American), who broke into the Top 100 at the age of 20, and Player 11 (male, Canadian), who began a professional career after being the number 1 ranked junior player in the world:

I broke into the top 100 for the first time and had some of my best results to date. Unfortunately, that season changed my expectations. I began to put a lot more pressure on myself … my focus was on all the wrong things. I was so worried about defending/recreating the previous year I had, that I barely had a single productive practice. (Player 10)

Nobody truly expected me to be a contender for junior slams, so everyone was pretty surprised that I made four finals, winning two of them in just a year. That obviously changed peoples’ perspectives. It was definitely a lot of pressure, having everyone expecting me to be top 100 right out of juniors. (Player 11)

To let down the people closest to me, my friends and family, is my most daunting fear. From an early age I was pretty aware about how many lives I affected. How many people had to sacrifice time, energy and money. The idea that it may not be worth it, or there might not be a way to repay them, haunts me at times.

If I wasn’t going to use my college degree to work towards financial independence, I needed to make this endeavor worth it. My family helped me financially and my coach agreed to be compensated with lunches after practice. There was constant fear on whether I would ever be good enough to make it all worthwhile.

Structural-caused instability (esteem needs)

The structure of the professional tour creates an environment of instability that also impacts on esteem needs. The lack of regular salaries or contracts on tour leaves players dependent on achieving results to earn money. Further, the 52-week rolling ranking system, where ranking points from more than 52 weeks prior are removed from players’ point total, places a time-sensitive pressure on players to continually earn results and maintain their spot within the professional system. The uncertainty caused by the tour’s structure is the catalyst for two major challenges that players face on tour and inhibits their esteem needs (Maslow, Citation1943) of status and recognition. It also leads them to making choices that are not always in the best interest of their health and wellbeing.

While injuries are an unfortunate reality of professional sport as a whole, the unique structure of tennis makes time away from the sport a serious threat to one’s ability to maintain a foothold within the system. Specifically, with no form of income, and the risk of ranking points disappearing, players feel pressure to avoid missing time from injury and an urgency to return to play as soon as possible. The experience of Player 15 exemplifies the difficult choices made to minimise the time away from the tour:

I broke into the top 10 for the first time at St Petersburg in 2016. Then soon came Miami where I got my first injury, which led to many others. A severe wrist problem came and I tried to avoid surgery while playing for nine months. April 2017, I finally decided to get it done. I was out for about six months and my ranking dropped to 350. Tennis is super difficult because you never stay where you are. (Player 15; female, Swiss)

The instability caused by the professional structure also leads to players feeling underappreciated. With a tournament system where only one player is victorious each week, the regularity of losing becomes commonplace and recent success gains prominence, with past successes losing significance. These feelings were experienced by Player 12 (male, American), a former Wimbledon junior singles champion, who stated “the sport has a way of making you feel irrelevant … with the likelihood of losing every week and the forever expanding field of players, chances are if you were once talk of the town, that will quickly diminish over time.” These feelings of irrelevance and change in status relate to Player 16’s (female, American) frustration regarding the status that is given to “winners”, and lack of appreciation of “losers”. Specifically, she explained: “Tennis puts this stigma on losing to the point that only winners receive the platform to speak. It’s truly sad that losers are barely acknowledged in a sport where defeat is an every week occurrence.”

Player 16’s views point to further inequalities that exist on the tour; a small number of players at the top of the sport’s structure are appreciated and given the ability to shape the narrative of professional tennis through on-court interviews and increased media opportunities, compared to the many lower-ranked players who are not given this opportunity. This leads to concern that a skewed image of the professional system is being portrayed to the public, one in which the experiences of the highest ranked players with their financial security and other benefits are shared, and the realities of most players are not represented.

Mental illness (self-actualisation)

Symptoms of mental illness associated with tour lifestyle challenges were a consistent finding across the data. While there were many subclinical symptoms of mental illness, there were additionally over 15% of players who explicitly reported experiencing mental illness on the professional tour (e.g., anxiety, panic attacks, depression and eating disorders). An example of this is seen in a quotation from Player 17 (female, Puerto Rican):

There is trauma after winning something that major that pushes you flat on your butt … As I became more upset I saw that depression was inevitable when it was tough to get out of bed. At one point you’re on top of the world and all of a sudden it ends and you just don’t know what just happened. It’s like whiplash. I couldn’t find ways to motivate myself to play. I just didn’t know what to do with myself. There are many times when all I wanted to do was cry every day, in bed, in a dark room.

It is now two weeks before my first French Open main draw. It felt as if I had no control of my mind. I had a panic attack on my flight from Dallas to Paris. It was nine hours of some of the most agony and pain I have ever felt. I thought that every breath I took could be my last. After getting to Paris, I could barely practice. I would walk off the court immediately and hop into a car to get back to my hotel. I just couldn’t function at all, not wanting to leave the hotel room.

These examples, as well as others from the dataset, highlight the powerful impact that mental illness has on professional players’ lives both inside and outside of tennis. Mental illness inhibits players’ ability to reach their full potential (i.e., self-actualisation; Maslow, Citation1943) on the professional tour.

Discussion

The present study aimed to gain a detailed, contextual understanding of the challenges that professional tennis players experience in their professional tour lifestyles and examine the impact these challenges have on their mental health. Analysis of a social media platform provided access to an extensive range of self-reported experiences of professional players and a deeper understanding of the professional tennis environment. The study’s findings are in line with Sarkar and Fletcher’s (Citation2014) assertion that elite sporting environments consist of a range of competitive, organisational, and personal stressors. Specifically, on the professional tennis tour, these include the weight of expectation (competitive), financial imbalance of the professional system, the social and psychological impact of living a nomadic existence, and structural-caused instability (organisational) and physical and mental fatigue (personal). Collectively, these challenges represent barriers to the satisfaction of key human needs (Maslow, Citation1943) and pose a risk to players’ mental health.

Challenges on the professional tour inhibit players’ ability to satisfy their needs on each level of Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchy. At the physiological level, physical and mental fatigue hindered players’ ability to meet their need for rest. At the safety needs level, the financial imbalance of the professional system led to employment uncertainty and financial stress impacting players’ job and financial security. Players’ love and belonging needs are impeded through their nomadic existence which threaten their need for sense of connection and friendship. At the esteem level, players’ needs are impacted by both the weight of expectation and structural-caused instability of the tour challenging their needs for feelings of achievement, recognition, and status. Finally, players’ self-actualisation is inhibited due to existing mental illness issues on tour. The impact of tour challenges on players’ needs is illustrated in .

Beyond impacting players’ ability to progress on tour, inhibited needs have implications for mental health. Not only did 15% of players within the sample explicitly refer to experiencing mental illness, but the very challenges which players face on the professional tour have known links to decreased mental health. For example, fear of failure that players exhibited due to the weight of their expectation on tour is associated with anxiety, depression, and eating disorders (Conroy, Citation2001; Lavallee et al., Citation2009; Sagar et al., Citation2007). Additionally, there are known links between financial stress and poorer mental health outcomes (O'Neill et al., Citation2005; Wadsworth et al., Citation2013), and research illustrating the impact of social support and connectedness on managing sporting and non-sporting challenges and enhancing wellbeing (Bernat & Resnick, Citation2009; DeFreese & Smith, Citation2014; Sheridan et al., Citation2014). Similarly, players felt pressure to stay on tour or take minimal time away due to injury to avoid losing their rankings and their foothold in the system. Although they did not specifically associate this structural caused instability with their mental health, it is well established that injury is a sport-specific risk factor for mental illness and may negatively impact mental health including the players’ psychological readiness to return to tennis (Haugen, Citation2022).

The present study’s findings illustrate a concerning picture. This is the first study to examine the mental health challenges on the professional tour, and further research is needed. A holistic approach to mental health like Keyes’ (Citation2002; Citation2005) dual continuum model can provide a more contextualised understanding of mental health and mental illness on tour by recognising the importance of acknowledging players’ levels of both mental health and illness. In an environment where the identified challenges of this study exist, simply focusing on preventing mental illness prevalence will not do enough to promote players’ emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing.

The study’s findings also pose questions around the structural issues in professional tennis. Most notably, the financial challenges players experience, which was partially understood prior to this research (ITF, Citation2017), became increasingly apparent. Players’ daily existence on tour were directly affected by the financial challenges in professional tennis. These findings beg the question: what steps can be taken by the ITF, ATP and WTA to improve the financial situation on tour? After uncovering financial issues within the sport in the ITF Pro Circuit Review (Citation2017), the ITF restructured entry level tournaments so that $10,000 and $15,000 events became $15,000 and $25,000 events, respectively. However, adding $5000 or $10,000 to be spread across an entire lower-level tournament may not be enough of a step in a sport where the top 1% of players on the men’s and women’s tours were earning 60% and 51% of all prize money in 2013, and where 1.8% and 3.1% of male and female players were earning a profit, respectively (ITF, Citation2017). With prize money increasing at the highest level of the sport (i.e., Grand Slam events) each year (Clarey, Citation2019), and the range of financial-related challenges identified throughout the professional structure, there are important questions to be asked about the distribution of prize money in the sport and the implications this has on the livelihood of players throughout the entire professional system.

While structural-related challenges are not directly within the control of professional players, other challenges are within players’ control and provide an opportunity to better manage on the professional tour. One of these challenges is managing the weight of expectation that players experience. In line with achievement goal theory (Nicholls, Citation1989), working on shifting players’ focus from a performance orientation emphasising outperforming others and results to a mastery orientation emphasising what is within players’ control like continual improvement, decision-making and effort can lead to decreased anxiety, increased intrinsic motivation, positive affect, and basic need satisfaction (Alvarez et al., Citation2012; Kipp & Weiss, Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2007). This could be complemented by developing the players’ ability to effectively self-regulate their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours through psychological skills training. Further, players can work to increase their ability to maintain relationships and connectedness amidst their nomadic existence, as well as increase their financial literacy and discover ways to generate alternative forms of income, develop budgets and find sponsorships or fundraising opportunities to increase their opportunity on tour. The ATP and WTA offer player development programs (i.e., ATP University, WTA Player Development Program) which cover a range of topics, like media training, finances, tour lifestyle and health and wellness to assist players adjust to the professional game. While these programs provide important opportunities for players to better prepare themselves for the challenges of the tour lifestyle, they are only offered to players who have ATP or WTA player membership and meet certain ranking requirements (i.e., ATP Top 200 singles or Top 100 doubles, WTA Top 750 singles or Top 200 doubles) (ATP, Citation2021; WTA, Citation2021). Courses like these could be extended to all full-time professional players across the ATP, WTA, and ITF, as adjusting to tour challenges is not something that only players ranked toward the top of the professional structure require. Regardless, whether players enrol in official training courses or not, educating oneself on the challenges of professional tennis and ways to manage these challenges is crucial to players’ development from performance and mental health standpoints.

Implications and future research

The findings of the present study have implications for players aspiring to play professional tennis. Prospective professional players and their coaches, families and other support networks can gain insightful information about the professional tour which can assist the familiarisation and preparation processes for their professional careers. These findings also strengthen the tennis literature by providing a contextualised understanding of the professional tennis lifestyle and challenges within the sport, which can be used to inform future tennis research.

Future research can build on this study’s findings by investigating how players manage the professional tour lifestyle challenges identified in this study. This can be done through examining players’ transitioning experiences into the sport. Ideally, this research would be longitudinal as a way to investigate players’ experiences as they are occurring. Future studies should also look to better understand mental health in professional tennis, taking a holistic approach (e.g., Keyes, Citation2002; Citation2005) to better comprehend the complexity of the issue. Finally, while the data collection for this study took place before the COVID-19 pandemic, the implications of the pandemic are likely to add to the challenges that players experience on the professional tour. As a result, future research can look to investigate challenges professional players experienced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Limitations

While the present study offers important contributions to the literature, it is not without limitations. First, the data was collected at a single time point rather than at various points throughout the players’ careers. A longitudinal design would allow for an understanding of whether identified challenges endured throughout players’ careers or changed over time. Second, a strength of the study was having a sample that was diverse across gender, achievement levels (e.g., participants included Grand Slam and Olympic champions, ATP and WTA Top 10, and players within and outside of the ATP and WTA Top 100), and evenly distributed amongst North America (n = 26) and Europe (n = 26). However, a disproportionate amount of the sample (i.e., 30.8%) was from the United States. Finally, while the data was collected from a rich data source, it is worth noting that these are simply the lifestyle challenges represented from this dataset and other professional players may experience different lifestyle challenges. Along similar lines, due to the voluntary nature of the players’ participation on the platform, it may be that the experiences described are not representative of those who choose not to share their stories. Moreover, the nature of the dataset (i.e., blog posts) meant that it was not possible for the researchers to follow up with probing questions that may have helped to reveal connections between themes. For example, players discussed pressures experienced when injured as “structural-caused instability”, which may also have implications for their physical and mental health. Future research could compliment the findings of the present study via alternative qualitative methods, such as using narrative research to provide rich insights into the lived experiences of professional tennis players on tour. Whilst blog posts also put players in the role as storyteller, narrative research can also explore the interactions between how the players’ personal experiences unfold over time and within a particular sociocultural context (Douglas & Carless, Citation2014).

Conclusion

This study provided evidence of the range of challenges that professional players face in their lifestyles on the professional tour, while highlighting the concern these challenges pose to players’ mental health. Access to a hard-to-reach population for data collection was gained through the use of a social media platform and data was analysed through a novel application of Maslow’s (Citation1943) hierarchy of needs to the sport discipline. The findings demonstrated the model’s relevance for understanding athletes’ performance challenges and their implications on athletes’ mental health. In doing so, the study adds empirical, theoretical, and methodological significance to the literature, in addition to its applied potential of informing aspiring professional players and their support networks with vital information to assist in their professional endeavours.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Noah Rubin for sharing with us his inspiration behind, and steps in, creating Behind the Racquet. His platform was invaluable for the completion of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://behindtheracquet.com/, as well as on Instagram under the handle @behindtheracquet.

Notes

1 In the present study, a professional tennis player was defined as someone competing on the ITF professional tennis circuit, ATP Challenger Tour, or ATP/WTA World Tour.

2 Keyes (Citation2002) defines emotional well-being as feelings of happiness and satisfaction with life, psychological well-being as positive individual functioning in terms of self-realisation, and social well-being as positive societal functioning in terms of being of social value.

References

- Alvarez, M. S., Balaguer, I., Castillo, I., & Duda, J. L. (2012). The coach-created motivational climate, young athletes’ well-being, and intentions to continue participation. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 6(2), 166–179. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.6.2.166

- Andrew, D. P., Martinez, J. M., & Flavell, S. (2016). Examining college choice among NCAA student-athletes: An exploration of gender differences. Journal of Contemporary Athletics, 10(3), 201–214.

- ATP. (2021). The 2021 ATP official rulebook. https://www.atptour.com/en/corporate/rulebook

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2007). National survey of mental health and wellbeing: Summary of results. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/Lookup/4326.0Main+Features32007?OpenDocument

- Battochio, R. C., Schinke, R. J., Eys, M. A., Battochio, D. L., Halliwell, W., & Tenenbaum, G. (2009). An examination of the challenges experienced by Canadian ice-hockey players in the National Hockey League. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 3(3), 267–285. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.3.3.267

- Battochio, R. C., Stambulova, N., & Schinke, R. J. (2016). Stages and demands in the careers of Canadian National Hockey League players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34(3), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2015.1048523

- Behind the Racquet. (2021, May 13). Behind the Racquet. https://behindtheracquet.com/

- Benson, S. G., & Dundis, S. P. (2003). Understanding and motivating health care employees: Integrating Maslow's hierarchy of needs, training and technology. Journal of Nursing Management, 11(5), 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2834.2003.00409.x

- Berger, R. (2015). Now I see it, now I don’t: Researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

- Bernat, D. H., & Resnick, M. D. (2009). Connectedness in the lives of adolescents. In R. J. DiClemente, J. S. Santelli, & R. A. Crosby (Eds.), Adolescent health: Understanding and preventing risk behaviors (pp. 375–389). Jossey-Bass.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A.C. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 213–227). Routledge.

- Brown, N. A., & Billings, A. C. (2013). Sport fans as crisis communicators on social media websites. Public Relations Review, 39(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2012.09.012

- Carrasco, A. E. R., Campbell, R. Z., López, A. L., Poblete, I. L., & García-Mas, A. (2013). Autonomy, coping strategies and psychological well-being in young professional tennis players. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 16(75), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.70

- Clarey, C. (2019). In tennis, men and women are united in looming prize-money fight. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/11/sports/tennis/grand-slam-prize-money.html

- Conroy, D. E. (2001). Progress in the development of a multidimensional measure of fear of failure: The performance failure appraisal inventory (PFAI). Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 14(4), 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800108248365

- Cooper, K. B., Wilson, M., & Jones, M. I. (2019). An exploratory case study of mental toughness variability and potential influencers over 30 days. Sports, 7(7), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.3390/sports7070156

- Cope, D. G. (2014, January). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. In Oncology Nursing Forum, 41(1), 89–91. ). https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.89-91

- Crandall, A., Powell, E. A., Bradford, G. C., Magnusson, B. M., Hanson, C. L., Barnes, M. D., Novilla, M. L. B., & Bean, R. A. (2020). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a framework for understanding adolescent depressive symptoms over time. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(2), 273–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01577-4

- DeFreese, J. D., & Smith, A. L. (2014). Athlete social support, negative social interactions, and psychological health across a competitive sport season. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 36(6), 619–630. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2014-0040

- Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2014). Life story research in sport: Understanding the experiences of elite and professional athletes through narrative. Routledge.

- Education Policy Institute. (2018). Prevalence of mental health issues within the student-aged population. https://epi.org.uk/publications-and-research/prevalence-of-mental-health-issues-within-the-student-aged-population/

- Ess, C. and the AoIR ethics working committee. (2002). Ethical decision-making and Internet Research: Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee. Retrieved from http://aoir.org/reports/ethics.pdf

- Foskett, R. L., & Longstaff, F. (2018). The mental health of elite athletes in the United Kingdom. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(8), 765–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.11.016

- Gorczynski, P. F., Coyle, M., & Gibson, K. (2017). Depressive symptoms in high-performance athletes and non-athletes: A comparative meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 51(18), 1348–1354. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096455

- Gordin, R. (2016). My consulting life on the PGA tour: A 25-year experience. In R.J. Schinke & D. Hackfort (Eds.), Psychology in professional sports and the performing arts (pp. 107–115). Routledge.

- Gouttebarge, V., Jonkers, R., Moen, M., Verhagen, E., Wylleman, P., & Kerkhoffs, G. (2017). The prevalence and risk indicators of symptoms of common mental disorders among current and former Dutch elite athletes. Journal of Sports Sciences, 35(21), 2148–2156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2016.1258485

- Gucciardi, D. F., Hanton, S., & Fleming, S. (2017). Are mental toughness and mental health contradictory concepts in elite sport? A narrative review of theory and evidence. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 20(3), 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.08.006

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., Mackinnon, A., Batterham, P. J., & Stanimirovic, R. (2015). The mental health of Australian elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.04.006

- Hale, A. J., Ricotta, D. N., Freed, J., Smith, C. C., & Huang, G. C. (2019). Adapting Maslow's hierarchy of needs as a framework for resident wellness. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 31(1), 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2018.1456928

- Haugen, E. (2022). Athlete mental health & psychological impact of sport injury. Operative Techniques in Sports Medicine, 30(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsm.2022.150898

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R., McCann, S., Durand-Bush, N., Moesch, K., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., Cogan, K., Donaldson, A., Poczwardowski, A., Noce, F., & Hunziker, J. (2020a). Athlete mental health in the Olympic/paralympic quadrennium: A multi-societal consensus statement. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1746379

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R., Moesch, K., McCann, S., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., & Terry, P. (2020b). Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(5), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473

- Homan, A. G. (2021). The needs of Virginia Tech student athletes during the transfer process [Master’s dissertation]. Virginia Tech University.

- Hookway, N. (2008). Entering the blogosphere': Some strategies for using blogs in social research. Qualitative Research, 8(1), 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794107085298

- Iasiello, M., & Van Agteren, J. (2020). Mental health and/or mental illness: A scoping review of the evidence and implications of the dual-continua model of mental health. Evidence Base: A Journal of Evidence Reviews in Key Policy Areas, 1(1), 1–45. https://doi.org/10.21307/eb-2020-001

- International Tennis Federation. (2017, March 30). ITF pro circuit review. https://www.itftennis.com/procircuit/about-pro-circuit/player-pathway.aspx

- International Tennis Federation. (2020, January 17). ITF world tennis tour by the numbers. https://www.itftennis.com/en/news-and-media/articles/itf-world-tennis-tour-by-the-numbers/

- ITF Global Tennis Report. (2019). ITF global tennis report 2019: A report on tennis participation and performance worldwide. ITF. http://itf.uberflip.com/i/1169625-itf- global-tennis-report-2019-overview/0

- Jensen, J. C. (2012). When are you going to get a real job?: An experiential sport ethnography of players’ experiences on the men's pro tennis futures tour [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Tennessee, Knoxville.

- Jerome, N. (2013). Application of the Maslow’s hierarchy of need theory; impacts and implications on organizational culture, human resource and employee’s performance. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 2(3), 39–45.

- Jones, P. B. (2013). Adult mental health disorders and their age at onset. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(54), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119164

- Kavanagh, E., Jones, I., & Sheppard-Marks, L. (2016). Towards typologies of virtual maltreatment: Sport, digital cultures & dark leisure. Leisure Studies, 35(6), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2016.1216581

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 593–602. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

- Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

- Keyes, C. L. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 539–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539

- Kipp, L. E., & Weiss, M. R. (2013). Social influences, psychological need satisfaction, and well-being among female adolescent gymnasts. Sport, Exercise, and Performance Psychology, 2(1), 62–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030236

- Kurtz, L. C., Trainer, S., Beresford, M., Wutich, A., & Brewis, A. (2017). Blogs as elusive ethnographic texts: Methodological and ethical challenges in qualitative online research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917705796

- Lavallee, D., Sagar, S. S., & Spray, C. M. (2009). Coping with the effects of fear of failure: A preliminary investigation of young elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 3(1), 73–98. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.3.1.73

- Mann, C., & Stewart, F. (2000). Internet communication and qualitative research: A handbook for researching online. Sage.

- Markham, A. N., & Buchanan, E. A., and the AoIR ethics working committee (2012). Ethical decision-making and Internet Research (version 2.0): Recommendations from the AoIR Ethics Working Committee. Retrieved from http://aoir.org/reports/ethics2.pdf

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

- Maslow, A. H. (1987). Motivation and personality (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Mental Health Foundation. (2016). Fundamental facts about mental health 2016. https://www.mentalhealth.org/uk/sites/deafult/files/fundamental-facts-about-mental-health-2016.pdf

- Milheim, K. L. (2012). Towards a better experience: Examining student needs in the online classroom through Maslow's hierarchy of needs model. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 8(2), 159–171.

- Moore, Z. E. (2016). Working with transnational professional athletes. In R. J. Schinke & D. Hackfort (Eds.), Psychology in professional sports and the performing arts (pp. 65–76). Routledge.

- Moravcsik, A. (2014). Transparency: The revolution in qualitative research. Political Science & Politics, 47(1), 48–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096513001789

- Morse, J. M. (2015). Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qualitative Health Research, 25(9), 1212–1222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315588501

- Nicholls, J. G. (1989). The competitive ethos and democratic education. Harvard University Press.

- Nikitina, T. K. (2021). Determinate factors affecting the selection process of National Junior College Athletic Association (NJCAA) Institutions by student-athletes [Doctoral dissertation]. Cleveland State University.

- Noblet, A. J., & Gifford, S. M. (2002). The sources of stress experienced by professional Australian footballers. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 14(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200209339007

- O'Neill, B., Sorhaindo, B., Xiao, J. J., & Garman, E. T. (2005). Financially distressed consumers: Their financial practices, financial well-being, and health. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 16(1), 73–87.

- Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2007). The self-report method. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224–239). Guilford.

- Pummell, E. K. L. (2008). Junior to senior transition: Understanding and facilitating the process [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Loughborough University.

- Reardon, C. L., Hainline, B., Aron, C. M., Baron, D., Baum, A. L., Bindra, A., Budgett, R., Campriani, N., Castadelli-Maia, J. M., Currie, A., Derevensky, J. L., Glick, I., Gorczynski, P., Gouttebarge, V., Grandner, M. A., Han, D. H., McDuff, D., Mountjoy, M., Polat, A., Purcell R., Putukian M., Rice S., Sills A., Stull T., Swartz L., Zhu L. J., Engebretsen, L. (2019). Mental health in elite athletes: International Olympic Committee consensus statement (2019). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 677–699. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100715

- Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., De Silva, S., Mawren, D., McGorry, P. D., & Parker, A. G. (2016). The mental health of elite athletes: A narrative systematic review. Sports Medicine, 46(9), 1333–1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2

- Ryba, T. V., Stambulova, N. B., & Ronkainen, N. J. (2016). The work of cultural transition: An emerging model. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(427), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00427

- Sagar, S. S., Lavallee, D., & Spray, C. M. (2007). Why young elite athletes fear failure: Consequences of failure. Journal of Sports Sciences, 25(11), 1171–1184. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640410601040093

- Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2014). Psychological resilience in sport performers: A review of stressors and protective factors. Journal of Sports Sciences, 32(15), 1419–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.901551

- Schaal, K., Tafflet, M., Nassif, H., Thibault, V., Pichard, C., Alcotte, M., Guillet, T., El Helou, N., Berthelot, G., Simon, S., & Toussaint, J. F. (2011). Psychological balance in high level athletes: Gender-based differences and sport-specific patterns. PLoS ONE, 6(5), e19007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019007

- Schinke, R. J., Bonhomme, J., McGannon, K. R., & Cummings, J. (2012). The internal adaptation processes of professional boxers during the showtime super six boxing classic: A qualitative thematic analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13(6), 830–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2012.06.006

- Schinke, R. J., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Moore, Z. (2018). International society of sport psychology position stand: Athletes’ mental health, performance, and development. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(6), 622–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2017.1295557

- Seppala, E., Rossomando, T., & Doty, J. R. (2013). Social connection and compassion: Important predictors of health and well-being. Social Research: An International Quarterly, 80(2), 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1353/sor.2013.0027

- Sheridan, D., Coffee, P., & Lavallee, D. (2014). A systematic review of social support in youth sport. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 198–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2014.931999

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Smith, R. E., Smoll, F. L., & Cumming, S. P. (2007). Effects of a motivational climate intervention for coaches on young athletes’ sport performance anxiety. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.29.1.39

- Snee, H. (2013). Making ethical decisions in an online context: Reflections on using blogs to explore narratives of experience. Methodological Innovations Online, 8(2), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.4256/mio.2013.013

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health: From process to product. Routledge.

- Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the world. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(2), 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023779

- Uphill, M., Sly, D., & Swain, J. (2016). From mental health to mental wealth in athletes: Looking back and moving forward. Frontiers in Psychology, 7(935), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00935

- Wadsworth, M. E., Rindlaub, L., Hurwich-Reiss, E., Rienks, S., Bianco, H., & Markman, H. J. (2013). A longitudinal examination of the adaptation to poverty-related stress model: Predicting child and adolescent adjustment over time. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 42(5), 713–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.755926

- Wilkinson, D., & Thelwall, M. (2011). Researching personal information on the public web: Methods and ethics. Social Science Computer Review, 29(4), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439310378979

- Wilson, E., Kenny, A., & Dickson-Swift, V. (2015). Using blogs as a qualitative health research tool: A scoping review. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 14(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406915618049

- WTA. (2021). WTA 2021 official rulebook. https://photoresources.wtatennis.com/wta/document/2021/03/08/d6d2c650-e3b4-42e7-ab2b-e539d4586033/2021Rulebook.pdf

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research and applications: Design and methods. Sage.