ABSTRACT

This study presents qualitative data on the retirement experiences of retired professional ice hockey players and the relationship of these experiences to self-reported depressive symptoms and measures of athletic identity. Data were obtained from an online survey sent to retired professional hockey players within the Professional Hockey Players’ Association (PHPA) database. A total of 213 retired players completed the qualitative section of the survey and were included in the study. Former players expressed an array of responses to questions about the best and most difficult parts of their athletic retirement experiences, and what they believe would help future generations of retiring hockey players. Within these responses, there were two distinct patterns of identity-based challenges among depressed former players. One subset of depressed former players, captured by our proposed term athletic identity flight, scored lower in athletic identity, and emphasized positive aspects of retirement related to “building a new identity.” A second subset of depressed former players, who we described with the term athletic identity gripping, noted an identity crisis upon retiring and retained a strong athletic identity post-career. Non-depressed former players in our sample were more likely to emphasize the importance of career support to help future retiring hockey players, whereas depressed former players emphasized the importance of mental health support. Our findings may inform future preventative interventions to assist retiring hockey players in their end-of-athletic-career transition and suggest the value of tailoring interventions based on the strength of athletic identity and the presence of depressive symptoms.

Lay summary: Retired professional ice hockey players with self-reported depression symptoms experienced two distinct identity challenges when transitioning out of sport. Some appeared to actively distance themselves from their former athletic identity (athletic identity flight). Others experienced an identity crisis and appeared to maintain their athletic identity over time (athletic identity gripping).

Implications for practice: Based on both quantitative and qualitative data analysis, results suggest that athletic identity is a factor to consider when tailoring interventions for professional hockey players transitioning to athletic retirement. Interventions may vary based on relationship with athletic identity during the transition; some will experience an “identity crisis” and attempt to hold onto their athletic identity, which may be a risk factor for long-term depressive symptoms. Others may actively distance themselves from their athletic identity during the transition, possibly due to emotional pain associated with the athlete role.

Depending on the presence of depressive symptoms, retiring players may have different intervention needs to assist with athletic retirement. Non-depressed players may benefit from practical support, such as planning their next career. Depressed players may benefit more from mental health outreach. Aligned with duty of care principles, results indicate a need for screening retiring athletes to identify those at risk for depression.

Players who obtain a high score on the Athletic Identity Measurement Scale, particularly those who retire suddenly and involuntarily (e.g., due to injury), should be considered at higher risk for depression during transition to athletic retirement and may benefit from mental health outreach.

Approximately one in five elite athletes experience distress upon retiring from sport (Grove et al., Citation1998; Park et al., Citation2013). A recent survey of over 800 former professional athletes in the UK found that an even larger proportion of retiring athletes may face emotional difficulties during the transition, as approximately 50% of participants reported concerns about their emotional wellbeing (e.g., depressive symptoms, loss of identity; BBC Sport, Citation2018). Due to increasing knowledge that athletic retirement is a challenging event in the lifespan of an athlete, there is increasing awareness that supporting retiring professional athletes is a duty of care issue (Grey-Thompson, Citation2017). In a recent study (N = 409) of active and retired professional hockey players, retired players exhibited significantly higher self-reported depressive symptoms compared to the general population, and approximately twice the rate of moderate to very severe levels of depression compared to active players (Aston et al., Citation2020).

Athletic retirement presents an uncommon and often abrupt change in life circumstances (Stambulova et al., Citation2021). Athletes describe difficulty replicating aspects of their athletic lifestyle post-retirement, including camaraderie with teammates and outlets for their competitive drive (Grove et al., Citation1998; Lally, Citation2007). The demanding and intensive schedules that athletes are accustomed to during their careers are also challenging to recreate in retirement (Baillie, Citation1993). Additionally, retiring athletes often lose access to an important social support network achieved through teammates and other team personnel (Stephan et al., Citation2003a). Throughout their careers, professional athletes can also miss out on pursuits that would otherwise help with athletic retirement and career transition. Higher educational attainment may be delayed or arrested due to the demands of being a professional athlete; subsequently, low educational status can preclude higher-level vocational opportunities (Stronach & Adair, Citation2010).

Altogether, these considerations point to the importance of pre-retirement planning, which is associated with successful adjustment to athletic retirement (Grove et al., Citation1998; Martin et al., Citation2014). Athletes experience fewer difficulties and more positive experiences when provided with pre-retirement information and guidance from teammates, coaches, and organizations (Stephan et al., Citation2003b). Life Development Interventions (LDI), outlined by Danish et al. (Citation1993), allow athletes to build helpful coping strategies and identify skills developed through sport that can be transferred to other areas of their lives, which positively impacts their career transition experiences (Lavallee, Citation2005).

Athletic identity and adjustment to retirement

Athletic identity has been a central focus in research on retirement from sport for several decades (Brewer et al., Citation1993; Park et al., Citation2013). The term was first defined by Brewer et al. (Citation1993), who described athletic identity as the degree to which an individual identifies with their role as an athlete. Similar to identity development in general, athletic identity develops prominently during late childhood and adolescence. It remains intact in young adulthood, unless competitive sport participation comes to an end, in which case athletic identity tends to diminish (Houle et al., Citation2010).

To compete at the highest levels, high-performance athletes are often required to organize their behavior along a single trajectory toward athletic improvement. As such, their identity as an athlete can easily become dominant and overshadow other viable alternative identities that might be useful when new demands and constraints in the social environment arise. This can result in identity foreclosure: absorption into the athlete role at the expense of exploration of different careers or philosophies (Brewer & Petitpas, Citation2017). Research by Finch (Citation2009) suggests further reinforcement of athletic identity through standards of compliance that promote group orientation above autonomous thought within teams. Due to these social factors in the life of an athlete, a strong athletic identity is common and often beneficial, as it promotes stability, consistency, social cohesion, and achievement of long-term goals related to athletic pursuits (Brewer et al., Citation1993; Brewer & Cornelius, Citation2001).

Despite the adaptive features of athletic identity-related to sport performance, a strong athletic identity can contribute to emotional challenges upon retirement from sport (Erpič et al., Citation2004; Grove et al., Citation1998; Martin et al., Citation2014). Strong athletic identity can increase the vulnerability of professional athletes to anxiety and depression upon retirement; especially when retirement is involuntary (Cosh et al., Citation2012; Martin et al., Citation2014). High athletic identity scores are also associated with the use of maladaptive coping strategies (Grove et al., Citation1997) and a prolonged adjustment period after retirement (Stambulova et al., Citation2007). Baillie and Danish (Citation1992) suggested that athletes often underestimate identity-related challenges associated with retirement, making them under-prepared to deal with the social and psychological impacts stemming from athletic retirement. Altogether, athletes with a strong athletic identity tend to experience more intense difficulties during their transition to retirement from sport (Erpič et al., Citation2004).

Purpose

This mixed-methods study examines the retirement experiences of former professional hockey players via their retrospective descriptions of their transition to retirement from sport and current measures of athletic identity. We analyzed how different responses correlate with depressive symptoms post-career. From a duty of care perspective, our goal was to understand experiences impacting the long-term wellbeing of professional hockey players to inform future research and interventions.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were former members of the PHPA, a union that represents personnel in the American Hockey League (AHL) and the East Coast Hockey League (ECHL). Approximately 4,000 retired players were sent a survey via email using contact information available in the PHPA contact information database, collected between 1993 and 2018. The only inclusion criteria for the study was that contact information through the PHPA database was available. Participants were provided informed consent in writing at the beginning of the survey. A total of 213 retired players completed the qualitative section of the survey and were included in the study, representing an estimated 56% of retired players who clicked on the survey link.

The mean age for study participants was 35.8 years of age (SD = 7.1), and the mean number of years since their transition to retirement from professional hockey was 7.0 years (SD = 4.1). The most frequently stated reason for retirement was personal choice (42.7%), followed by acute or recurring injury (32.7%), and declining skills or aging (10.4%). The sociodemographic characteristics of study participants are summarized in .

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of retired hockey players.

Measures

Retrospective post-Retirement survey

This survey was originally developed by the authors of this study to investigate the mental health of current and former professional hockey players. Other data from this survey have been published previously (see Aston et al., Citation2020). In the present study, we used survey data to examine the subjective experiences of retirement reported by former players. Participants provided free-response answers reflecting on their retirement experiences. The three qualitative survey questions were: (a) What was the best part of the transition to retirement from professional hockey? (b) What was the most difficult part of the transition to retirement from professional hockey? (c) What do you think would help with the issues professional hockey players face when retiring? Participant responses consisted of short phrases, sentences, and infrequently, short paragraphs.

DASS-21 (Current)

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale is a 21-item self-report measure composed of three subscales assessing depression, anxiety, and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995a). Participants completed the DASS-21 as a reflection of their current symptoms. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (does not apply to me at all) to 3 (applies to me very much or most of the time). In scoring the DASS-21, scores for each 7-item subscale are doubled to fit with the cutoff scores of the original full-scale version (DASS). Score ranges are 10–13 for “mild” depression, 14–20 for “moderate” depression, 21–27 for “severe” depression, and 28 + for “very severe” depression. For this study, we only used the 7-item depression subscale of the DASS-21 (e.g., “I felt I wasn’t worth much as a person”; “I couldn’t seem to experience anything positive at all”; α = .89, 95% CI [.87, .90]). The DASS has demonstrated adequate discriminant and convergent validity with the Beck Depression Inventory (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995b) and good internal reliability (α = .88; Henry & Crawford, Citation2005).

AIMS (Current)

The Athletic Identity Measurement Scale (AIMS) is a 7-item self-report measure designed to assess how strongly and exclusively an individual identifies with the athlete role (Brewer & Cornelius, Citation2001). Participants completed the AIMS as a reflection of their current athletic identity. The questions are answered using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Scores range from 7–49, with a higher score indicating a stronger and more exclusive athletic identity. Brewer and Cornelius (Citation2001) demonstrated the AIMS is a multidimensional model that is internally consistent (α = .81), with three highly correlated first-order factors (social identity, exclusivity, and negative affectivity) subordinate to one higher-order factor (athletic identity). Items in the Negative Affect scale of the AIMS include reference to depression (e.g., “I would be very depressed if I were injured and could not compete in sport”). Because we examined the relationship between athletic identity and depression in our study, we excluded the Negative Affect scale to avoid spurious correlations. Additionally, items within the Social Identity scale (e.g., “Most of my friends are athletes”; α = .56, 95% CI [.46, .65]) possessed inadequate internal consistency. As such, we used the Exclusivity subscale of the AIMS as a proxy for athletic identity (“Sport is the most important part of my life; I spend more time thinking about sport than anything else”; α = .86, CI [.82, .89]).

Procedure

The research protocol was approved by the Administrative Panel on Human Subjects in Medical Research within Stanford University’s Institutional Review Board (Registration #4947). All retired professional hockey players for whom the PHPA had e-mail contact information in their database were sent the survey link. Participants were asked to provide their full legal name, email address and for permission to be contacted for future studies. Participant data was stored on a HIPAA-compliant encrypted server.

The first two study authors and primary coders (PA, MB) analyzed responses using a general inductive data analysis approach – a method involving an iterative process of coding and grouping coded data into categories and subcategories to develop a conceptual model representing the data (Mayring, Citation2014; Thomas, Citation2006). The goal of this phase was to identify distinct factors underlying thoughts about retirement experiences from professional hockey and to formulate a theoretical framework that could help direct interventions and further research. Initial categories were identified through coding the first 50% of the data via discussion between PA and MB of each participant's response. Next, we iteratively revised and reorganized data into major categories and subcategories while concurrently refining definitions of each category. We then coded the remaining 50% of responses using established categories and subcategories. After coding the dataset, authors (PA, MB) provided an additional study author (MA) the category definitions. Initially, MA was randomly assigned 50% of participant responses for each question. After coding the data, PA and MA discussed all discrepancies from primary raters, and category definitions were updated to account for those discrepancies to further reduce ambiguity. The remaining randomly assigned 50% of participant responses were then assigned to MA to determine intercoder reliability. The average intercoder reliability of all three research questions in the present study was 98.99% agreement, with a Cohen’s Kappa (κ) of .98. A Cohen's Kappa above .75 is considered excellent (Fleiss et al., Citation1981). Due to high intercoder agreement, primary raters PA and MB decided to use their coding for analyses instead of attempting to resolve any remaining discrepancies through discussion. The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (PA). The data are not publicly available to protect privacy of research participants.

Analyses

Demographics and group comparisons were primarily analyzed using SPSS 26 for Mac OS, and multiple regression models were analyzed using R statistical software, version 3.5.3. We employed a mixed-methods study design, which combines the strengths of quantitative and qualitative methods (McKim, Citation2017). Statistical significance was evaluated using an alpha level of .05 (two-tailed). Percentages and means were calculated to determine the sociodemographic characteristics of participants. Answers to qualitative questions were only coded if they were interpretable and directly relevant to the question. Frequencies of coded responses were calculated and converted to percentages. Means and standard deviations of depressive symptoms were calculated and stratified by major categories and subcategories. Pearson correlation coefficients were computed to examine the relationships between qualitative data and both depressive symptoms and athletic identity. We used pairwise deletion for instances of missing data. Independent-samples t-tests were used to follow-up on significant Pearson correlations, and Cohen’s d was used to estimate effect size. To account for potential Type I error and to control for possible confounds, we ran multiple linear regression equations with depression as the outcome variable and included all subcategory responses in the model for each study question while controlling for factors known in the research to be related to adjustment to retirement or depression in general, including age, years retired, the reason for retirement, educational attainment, annual income, and marital status. We did not control for race in regression equations due to the sample being predominantly White. For multiple regression models, frequencies of coded responses were formatted as multiple observations. Data was formatted and shaped in R using the reshape2 package (Wickham, Citation2007). Questions that were unanswered or did not endorse a response category were filtered out of the data set. This procedure was conducted to allow for the inclusion of multiple coded response subcategories per participant into the analysis, while enabling exclusion of coded response subcategories that were not endorsed by the participant so that unendorsed subcategories were not falsely associated with depression scores. This allowed us to analyze multiple observations of endorsed coded responses as categorical predictors in the multiple regression models.

Table 2. Representative verbatim participant responses.

Results

Overview

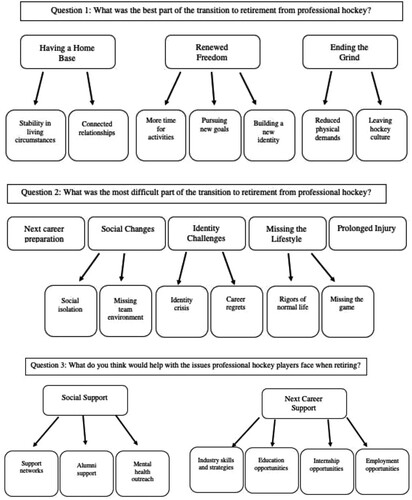

For all three qualitative questions, a conceptual visualization of categories and subcategories derived from coding procedures is presented in . Representative verbatim participant responses for each category or subcategory are presented in . Frequencies of coded responses and correlations of response categories with depressive symptoms are presented in .

Table 3. Frequencies of coded responses and correlations with self- reported depressive symptoms.

Question 1: what was the best part of the transition to retirement from professional hockey?

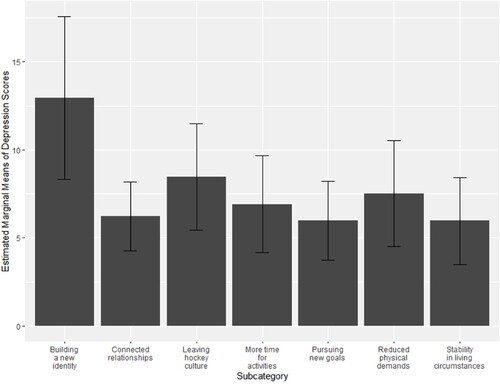

We ran a multiple linear regression model on data derived from answers to all three questions with depression scores as the dependent variable; covariates of age, the reason for retirement, years retired, education, income, and marital status; and question subcategories as predictor variables. The model was significant (F19,245 = 3.61, p < 0.001) and accounted for 22% (r2 = 0.22) of the variance in depression scores. Results showed a significant relationship between participants who endorsed Building a New Identity as being the best part of their athletic retirement experience and depression scores (b = 6.67, t = 2.56, p = 0.011). Those participants who stated their reason for retirement was due to either recurring injury/illness or sudden injury/illness had significantly higher depression scores (b = 5.1, t = 3.88, p < 0.001; b = 4.58, t = 3.01, p = 0.003). Education (b = −1.45, t = −3.8, p < 0.001) was also a significant predictor and negatively correlated with symptoms of depression.

Estimated marginal means were calculated, showing that participants who endorsed Building a New Identity averaged a depression score of 14.9 (95% CI [9.51, 20.3]), which falls in the moderate range of depression. The estimated marginal means for depression scores of all participants who endorsed other subcategories fell in the normal range for depressive symptoms. Estimated marginal means of depression scores for Question 1 subcategories are presented in .

Figure 2. Estimated marginal means for question 1 subcategories. Note. Estimated marginal means from multiple linear regression model examining relationship between question 1 subcategories and depression while controlling for age, years retired, reason for retirement, educational attainment, annual income, and marital status.

Question 2: what was the most difficult part of the transition to retirement from professional hockey?

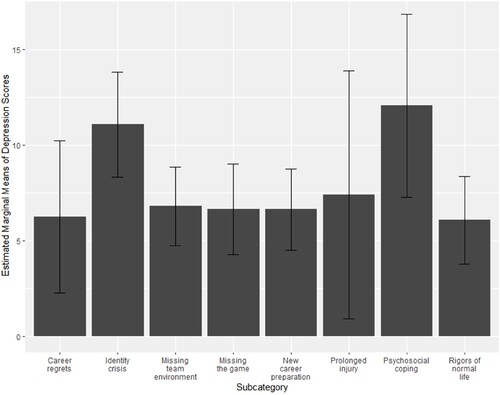

Multiple regression results show that the model was significant (F20,255 = 3.80, p < 0.001) and accounted for 23% (r2 = 0.23) of the variance in depression scores. Results showed a relationship between participants who endorsed Social Isolation as being the most difficult part of their retirement experience and depression scores (b = 6.24, t = 2.33, p = 0.02), as well as between participants who endorsed Identity Crisis and depression scores (b = 4.24, t = 2.39, p = 0.02). Participants who stated their reason for retirement was due to sudden injury or illness had significantly higher depression scores (b = 3.56, t = 2.82, p = 0.005). Education (b = −1.82, t = −4.94, p < 0.001), level of income (b = −1.00, t = −2.24, p = 0.025), and being married (b = −4.28, t = −3.04, p = 0.003) were also significant predictors and negatively correlated with depression.

Estimated marginal means were calculated, showing that participants who endorsed Social Isolation as being the most difficult part of their retirement experience averaged a depression score of 13.6 (95% CI [7.42, 19.7]; mild range of depression), and participants who endorsed Identity Crisis averaged a depression score of 11.1 (CI [6.83, 15.3]; mild range of depression). The estimated marginal means for depression scores of all participants who endorsed other subcategories fell in the normal range for depressive symptoms. Estimated marginal means of depression scores for subcategories in Question 2 are presented in .

Figure 3. Estimated marginal means for question 2 subcategories. Note. Estimated marginal means from multiple linear regression model examining relationship between question 2 subcategories and depression while controlling for age, years retired, reason for retirement, educational attainment, annual income, and marital status.

Question 3: what do you think would help with the issues professional hockey players face when retiring?

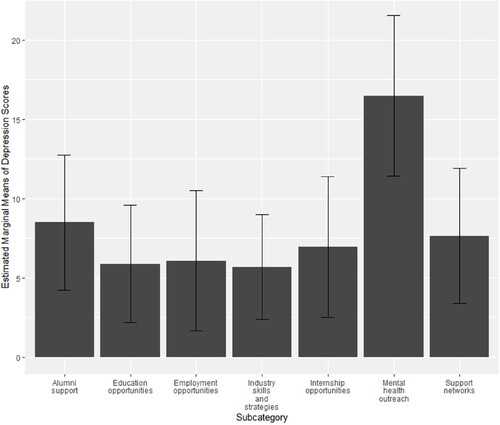

Multiple linear regression for Question 3 showed the model was significant (F19,210 = 3.69, p < 0.001) and accounted for 25% (r2 = 0.25) of the variance in depression scores. Results showed a relationship between participants who endorsed Mental Health Outreach as being the most important way to help players transition to athletic retirement and depression scores (b = 9.04, t = 3.5, p < 0.001). Furthermore, participants who stated their reason for retirement was due to sudden injury or illness had significantly higher levels of depression (b = 4.99, t = 3.47, p < 0.001). Education level (b = −1.7, t = −3.88, p < 0.001) was also a significant predictor and negatively correlated with depression.

Estimated marginal means were calculated, showing that participants who endorsed Mental Health Outreach averaged a depression score of 18.1 (95% CI [12.9, 23.4]; moderate range of depression). The estimated marginal means for depression scores of all participants who endorsed other subcategories fell in the normal range for depressive symptoms. Estimated marginal means of depression scores for subcategories in Question 3 are presented in .

Figure 4. Estimated marginal means for question 3 subcategories. Note. Estimated marginal means from multiple linear regression model examining relationship between question 3 subcategories and depression while controlling for age, years retired, reason for retirement, educational attainment, annual income, and marital status.

Two subsets of identity challenges

Our initial findings showed elevated depression scores for participants who expressed that “building a new identity” was the best part of their transition (n = 16), as well as participants who expressed that “identity crisis” was the most difficult part of their retirement experience (n = 37). As a result, we conducted a Pearson correlation to evaluate if the same participants endorsed identity-based responses to both questions. We did not observe a statistically significant correlation, r(196) = 0.13, p = 0.08, indicating nonsignificant crossover between participants with an identity-based response to Questions 1 and 2, respectively.

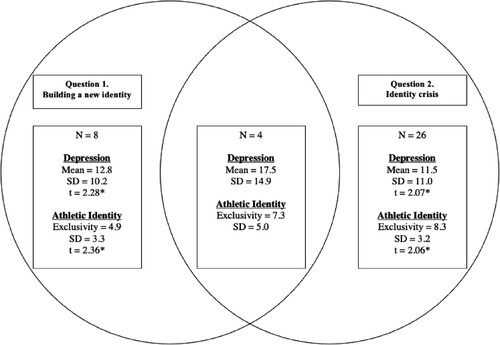

Next, we compared athletic identity scores of participants in these two groups (“building a new identity” and “identity crisis”). Participants who expressed that “building a new identity” was the best part of their transition (M = 5.1, SD = 3.5) scored significantly lower in their athletic identity exclusivity compared to the rest of the sample (M = 7.2, SD = 3.5; t(194) = 2.36, p = 0.019, d = 0.61, CI [0.36, 3.96]). In contrast, participants who expressed “identity crisis” as being the most difficult part of their retirement experience (M = 8.4, SD = 3.4) scored significantly higher in their athletic identity exclusivity compared to the rest of the sample (M = 7.0, SD = 3.6; t(201) = 2.06, p = 0.041, d = 0.40, CI [0.06, 2.70]). These differences suggest there may be two distinct identity-based challenges retiring professional hockey players face that may confer risk for depression. A summary of these two subsets of athletes, including depression and athletic identity scores, is presented in .

Figure 5. Two subsets of athletes with self-reported identity-based experiences during athletic retirement. Note. Depression and Athletic Identity Exclusivity of former hockey players with identity-based responses for questions 1 and 2, including t scores comparing athletic identity and depression to the rest of the sample. * p < .05.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest study reporting qualitative data by sample size to date examining the retirement experiences of professional athletes. Our findings highlight two discrete types of identity challenges among participants experiencing depression. A subset of these participants retrospectively emphasized the benefits of “building a new identity” upon retiring from professional hockey and scored significantly lower in athletic identity. In contrast, another subset of participants expressed that an “identity crisis” was the most difficult aspect of their athletic retirement experience and scored significantly higher in athletic identity. Our findings also highlight general differences in preferred forms of support among participants: those with lower depression scores generally articulated “next career support” as the most beneficial intervention for retiring hockey players, while those with higher depression scores were more likely to emphasize the crucial importance of mental health outreach.

Interestingly, we found that participants who expressed that “building a new identity” was the best part of athletic retirement had both lower athletic identity and higher depression scores compared to the rest of our sample. There are several possible explanations for this finding. If we assume that during their playing career these individuals had a stronger athletic identity compared to the time they completed the survey, this response suggests that these athletes may have been distancing themselves from their athletic identity since the end of their playing career. Athletic identity has been shown to decline as athletes near the end of their careers (Martin et al., Citation2014) and as athletes anticipate a disruption in their athletic identity, they actively decrease its prominence prior to retirement (Lally, Citation2007; Yao et al., Citation2020). Additionally, previous research demonstrates that endorsement of athletic identity predicts anxiety and depression post-retirement (Giannone et al., Citation2017). Our findings suggest that depression related to identity challenges during the retirement process may be prolonged for some athletes. Given the observed higher depression scores in this subset of athletes, it may be that this distancing from athletic identity is not an entirely positive process, even though there is an implied positive valence if we contextualize responses with the question itself (i.e., the “best” part of the transition to retirement). Rather, the distancing may be a response to painful associations with their previous role as a professional athlete, leading them to retrospectively consider the opportunity to construct a new identity as a positive aspect of ending their hockey career. We propose the term athletic identity flight as a way of describing this experience observed in our data.

A second explanation for this finding may be that these individuals have difficulties with identity in general, as is the case in identity diffusion. Identity diffusion is associated with depressive symptoms, and is characterized, in part, by uncertainty about one’s beliefs, preferences, and long-term goals (Renton et al., Citation2021; Taylor & Goritsas, Citation1994). Athletes experiencing identity diffusion may have difficulties identifying strongly with any role (including their role as an athlete) and may also be more vulnerable to depression in general. Finally, it may be that depressed former players are simply more likely to be self-referential in their thinking style – a known feature of depression (Mor & Winquist, Citation2002) – and are therefore more likely to frame their thinking toward positive changes during retirement in terms of identity, rather than by more externally oriented pursuits such as goals or activities.

Participants who expressed experiencing an “identity crisis” as being the most difficult aspect of their transition out of hockey were also more likely to be depressed compared to the rest of our sample. These individuals also obtained significantly higher scores on athletic identity – specifically in contrast to the subset of participants who regarded “building a new identity” as a positive aspect of athletic retirement – suggesting long-term maintenance of athletic identity. We propose the term athletic identity gripping to capture the experience of this subset of depressed former hockey players. These findings align with the research literature, as numerous studies show the potential for an identity crisis during athletic retirement, particularly if individuals have an exclusive athletic identity (Ronkainen et al., Citation2016). Additionally, exclusive athletic identity during retirement is associated with a longer adjustment period (Brewer et al., Citation1993; Grove et al., Citation1997) and the use of maladaptive coping strategies during the transition (Grove et al., Citation1997). It may be that exclusive athletic identity following athletic retirement was a maintenance factor for depressive symptoms over time, with maladaptive coping strategies playing a mediating role. Irrespective of causal explanations, our findings clearly suggest a subset of depressed former professional hockey players tend to sustain their athletic identity into their retirement years.

We also found differences in preferred forms of support among participants, depending on their depression scores. Participants with lower depression scores were more likely to emphasize the importance of “next career support,” whereas participants with higher depression scores instead focused on the importance of mental health outreach. This finding aligns with a taxonomy of career transition interventions for athletes, which exist on a continuum between preventative/educational and crisis/coping (Stambulova et al., Citation2021). Although retiring athletes may benefit from both approaches, our results suggest the prospective benefits of a given intervention may partially depend on an individual's mental health status.

Limitations

There are several important limitations to note when interpreting the results of the present study. Given the subjective nature of qualitative data analysis, alternative categorization of the data are conceivable, and we cannot ascertain whether all participants accurately interpreted the study questions. Although our regression models for each study question were statistically significant and accounted for several potential confounds, they accounted for a small amount of the variance of depression scores. There may be more powerful models based on other reasonable ways of categorizing the qualitative data. Importantly, as the reflections about retirement experiences from our participants were retrospective and measurements of depression and athletic identity were current, we cannot make any conclusions based on causality. It may be that depressive symptoms influenced participants’ responses through mood-dependent memory and biased their responses to qualitative questions about their retirement experiences. As participants self-selected to participate in the survey, there may be response biases impacting generalizability of the findings. Our data should also not be seen as statistically representative of the true frequencies of participant experiences, as participants tended to list only one response to each question. Assuming participants had diverse aspects of their retirement experience that were relevant to a given study question, this may have resulted in an underestimation of the true frequency of certain retirement experiences. As an example, a large proportion (∼38%) of our sample noted that they retired due to injury or illness, whereas only 3% of respondents emphasized injury as being a difficult part of their retirement experience. We should also not assume a lower frequency of a response category indicates a lower impact of that retirement experience across our sample. Indeed, our regression analyses demonstrate that participants who reported they retired due to injury averaged statistically higher depression scores than the rest of our sample. Finally, professional hockey may represent a unique culture, and our sample was highly homogenous with race and gender (White and male). Caution should therefore be used in generalizing study findings to other athlete populations.

Clinical implications

Several clinical implications emerged from our data that may be relevant for future interventions to support professional hockey players in their transition to athletic retirement. First and foremost, individual differences should be considered when devising interventions for a particular athlete. Our results indicate that factors to consider may include athletic identity and depressive symptoms. Athletes seeking to distance themselves from their athletic identity may benefit from interventions encouraging exploratory behavior in service of cultivating a new identity, including garnering new experiences, and developing interests and skills outside of their sport. Other athletes more firmly attached to their athletic identity may similarly benefit from exploratory behavior as a prophylactic activity to stave off an identity crisis; though they may find additional benefit from opportunities to stay connected to the game via employment or through alumni connections. Our results further suggest that retiring players may have different intervention needs depending on the presence of depressive symptoms – non-depressed players may benefit more from practical support in planning their next career, and depressed players may benefit more from mental health outreach. Taking a duty of care perspective on transition support for retiring athletes, our study highlights the crucial importance of regular mental health screening of retiring athletes. Outreach should be provided for athletes who screen positive for depression. Players retiring due to injury or players who score high on athletic identity should also be considered at higher risk for depression following athletic retirement.

Future directions

In addition to better understanding the retirement experiences of professional hockey players, this study was intended to generate hypotheses for future research. Follow-up quantitative research may be helpful to more accurately estimate the true frequencies of the various issues related to athletic retirement identified in our study. Further research should also be conducted to clarify and explore the two subsets of identity-based challenges found in depressed retired players. Of particular interest may be longitudinal studies to capture the nuances of how former professional players in ice hockey and other sports navigate their athletic identity as they transition to athletic retirement and to investigate causality in the relationship between retirement experiences and depression symptoms later in life. Such research may serve to clarify the identity-based challenges associated with depression in the present study, inform existing models (e.g., Stambulova, Citation2017; Wylleman, Citation2019), and extend the taxonomy of career transition intervention (Stambulova et al., Citation2021) through developments in hockey and other sports. Utilizing the findings from this study, research-informed interventions designed to assist professional hockey players facing identity-based challenges as they transition to athletic retirement should be developed and tested. Key intervention strategies to test may include individualized interventions based on depressive symptoms and athletic identity, alumni-led mentorship programs for retiring players, and – perhaps most fundamentally – thorough mental health screening to identify players needing additional support. Finally, knowing the importance of a proactive approach to retirement planning for athletes, we should also test the effectiveness of services already in place, while differentiating between the needs of athletes tending toward identity gripping vs identity flight. For instance, since 1997, the PHPA has offered services and partnerships through their Career Enhancement Program to assist its members in their transition to athletic retirement. Future research should investigate the impact of engagement with such services on mental health outcomes following athletic retirement.

Conclusion

The mixed-methods design and large sample size of the current study provided a unique look at different facets of the retirement experiences of professional ice hockey players. The research indicates there may be two distinct identity-based challenges players face during athletic retirement which confer risk for depression following athletic retirement. It may be that tailoring interventions for retiring athletes based on their depressive symptoms and athletic identity will contribute to successful adjustment to athletic retirement and improve post-career mental health outcomes in athlete populations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aston, P., Filippou-Frye, M., Blasey, C., Johannes van Roessel, P., & Rodriguez, C. I. (2020). Self-reported depressive symptoms in active and retired professional hockey players. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue Canadienne des Sciences du Comportement, 52(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/cbs0000169

- Baillie, P. (1993). Understanding retirement from sports. The Counseling Psychologist, 21(3), 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000093213004

- Baillie, P., & Danish, S. (1992). Understanding the career transition of athletes. The Sport Psychologist, 6(1), 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.6.1.77

- BBC Sport. (2018, February 5). Half of retired sports people have concerns over mental and emotional wellbeing. Retrieved December 6, 2019, from https://www.bbc.com/sport/42871491.

- Brewer, B. W., & Cornelius, A. E. (2001). Norms and factorial invariance of the athletic identity measurement scale. Academic Athletic Journal, 15(2), 103–113.

- Brewer, B. W., & Petitpas, A. J. (2017). Athletic identity foreclosure. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.05.004

- Brewer, B. W., Van Raalte, J. L., & Linder, D. E. (1993). Athletic identity: Hercules’ muscles or Achilles heel? International Journal of Sport Psychology, 24(2), 237–254.

- Cosh, S., Crabb, S., LeCouteur, A., & Kettler, L. (2012). Accountability, monitoring and surveillance: Body regulation in elite sport. Journal of Health Psychology, 17(4), 610–622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311417914

- Danish, S. J., Petitpas, A. J., & Hale, B. D. (1993). Life development intervention for athletes. The Counseling Psychologist, 21(3), 352–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000093213002

- Erpič, S. C., Wylleman, P., & Zupančič, M. (2004). The effect of athletic and non-athletic factors on the sports career termination process. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 5(1), 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1469-0292(02)00046-8

- Finch, L. M. (2009). Understanding and assisting the student-athlete-to-be and the new student-athlete. Counseling and Psychological Services for College Student-Athletes, 1–50.

- Fleiss, J. L., Levin, B., & Paik, M. C. (1981). The measurement of interrater agreement. In J. Wiley (Ed.), Statistical methods for rates and proportions (pp. 598–626). John Wiley & Sons.

- Giannone, Z. A., Haney, C. J., Kealy, D., & Ogrodniczuk, J. S. (2017). Athletic identity and psychiatric symptoms following retirement from varsity sports. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 63(7), 598–601. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764017724184

- Grey-Thompson, B. (2017). Duty of care in sport review: Independent report to government. Department for Digital, Culture, Media, & Sport. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/610130/Duty_of_Care_Review_-_April_2017__2.pdf.

- Grove, J. R., Lavallee, D., & Gordon, S. (1997). Coping with retirement from sport: The influence of athletic identity. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 9(2), 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209708406481

- Grove, J. R., Lavallee, D., Gordon, S., & Harvey, J. H. (1998). Account-making: A model for understanding and resolving distressful reactions to retirement from sport. The Sport Psychologist, 12(1), 52–67. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.12.1.52

- Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44(2), 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

- Houle, J. L., Brewer, B. W., & Kluck, A. S. (2010). Developmental trends in athletic identity: A two-part retrospective study. Journal of Sport Behavior, 33(2), 146. http://jvlone.com/sportsdocs/AthleticIdentityI2010.pdf.

- Lally, P. (2007). Identity and athletic retirement: A prospective study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.03.003

- Lavallee, D. (2005). The effect of a life development intervention on sports career transition adjustment. The Sport Psychologist, 19(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.19.2.193

- Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995a). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995b). Manual for the depression, anxiety, and stress scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Foundation of Australia.

- Martin, L. A., Fogarty, G. J., & Albion, M. J. (2014). Changes in athletic identity and life satisfaction of elite athletes as a function of retirement status. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 26(1), 96–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2013.798371

- Mayring, P. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: Theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. Klagenfurt. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-395173.

- McKim, C. A. (2017). The value of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(2), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815607096

- Mor, N., & Winquist, J. (2002). Self-focused attention and negative affect: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 128(4), 638–662. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.4.638

- Park, S., Lavallee, D., & Tod, D. (2013). Athletes’ career transition out of sport: A systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(1), 22–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2012.687053

- Renton, T., Petersen, B., & Kennedy, S. (2021). Investigating correlates of athletic identity and sport-related injury outcomes: a scoping review. BMJ Open, 11(4), e044199. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044199

- Ronkainen, N. J., Kavoura, A., & Ryba, T. V. (2016). A meta-study of athletic identity research in sport psychology: Current status and future directions. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 9(1), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2015.1096414

- Stambulova, N., Stephan, Y., & Jäphag, U. (2007). Athletic retirement: A cross-national comparison of elite French and Swedish athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(1), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.05.002

- Stambulova, N. B. (2017). Crisis-transitions in athletes: Current emphases on cognitive and contextual factors. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.013

- Stambulova, N. B., Ryba, T. V., & Henriksen, K. (2021). Career development and transitions of athletes: The international society of sport psychology position stand revisited. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(4), 524–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1737836

- Stephan, Y., Bilard, J., Gregory, N., & Delignières, D. (2003a). Repercussions of transition out of elite sport on subjective well-being: A one-year study. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15(4), 354–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/714044202

- Stephan, Y., Bilard, J., Ninot, G., & Delignières, D. (2003b). Bodily transition out of elite sport: A one-year study of physical self and global self-esteem among transitional athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(2), 192–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2003.9671712

- Stronach, M. M., & Adair, D. (2010). Lords of the square ring: Future capital and career transition issues for elite indigenous Australian boxers. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2(2), 46–70. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v2i2.1512

- Taylor, S., & Goritsas, E. (1994). Dimensions of identity diffusion. Journal of Personality Disorders, 8(3), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1521/pedi.1994.8.3.229

- Thomas, D. R. (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214005283748

- Wickham, H. (2007). Reshaping data with the reshape package. Journal of Statistical Software, 21(12), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v021.i12

- Wylleman, P. (2019). A developmental and holistic perspective on transitioning out of elite sport. In M. H. Anshel (Ed.), APA handbook of sport and exercise psychology: Vol. 1. Sport psychology (pp. 201–216). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000123-011.

- Yao, P. L., Laurencelle, L., & Trudeau, F. (2020). Former athletes’ lifestyle and self-definition changes after retirement from sports. Journal of Sport and Health Science, 9(4), 376–383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jshs.2018.08.006