ABSTRACT

High school sport presents opportunities for adolescents to build a solid foundation for positive mental health. Given recent calls to consider gender as a key variable when studying mental health, the purpose of the study was to investigate the influence of gender on the relationship between the satisfaction/frustration of the three basic psychological needs and mental health in high school student-athletes. A sample of 925 Canadian adolescents completed an online survey, reporting on sociodemographic variables and two scales: the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale and the Mental Health Continuum – Short Form. Analyses included a moderation analysis in which the satisfaction or frustration of each basic psychological need was the independent variable, gender was the moderator variable, and mental health was the dependent variable. The direct relationships between the satisfaction of each basic psychological need and participants’ positive mental health were positive and significant. Moreover, the frustration of the three basic psychological needs were significantly associated with lower levels of positive mental health. Gender was found to moderate two out of the six tested relationships (i.e., autonomy frustration and relatedness frustration), with the relationship between the dependent and independent variable being stronger for girls than boys. Results indicate the importance of creating sporting environments that satisfy student-athletes’ basic psychological needs. Gender differences suggest that removing from sport participation elements that frustrate basic psychological needs is especially meaningful for girls. Research is also needed to expand conceptualisations of gender beyond a binary construct.

Research indicates that high school sport has the potential to positively influence adolescents’ mental health (e.g., Eime et al., Citation2013). However, questions regarding gender influences remain, particularly when comparing the sport participation rates and mental health profiles of girls and boys. The present study attempts to shed light on this issue by deploying self-determination theory as a framework for understanding the satisfaction and frustration of adolescent girls’ and boys’ basic psychological needs in connection to their mental health.

Adolescence is a period of development occurring between the ages of 10–19 years denoting the transition from childhood to adulthood (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2021). This transition period is marked by an array of biological, physical, and psychological changes, which render adolescents subject to opportunities and vulnerabilities that can positively or negatively influence their mental health (Laporte et al., Citation2021). Adolescence has been linked with increased symptoms and diagnoses of mental health conditions such as anxiety and depression (Costello et al., Citation2003; Beauchamp et al., Citation2018). This increase is particularly notable in girls who have been shown to have poorer mental health profiles compared to boys (Campbell et al., Citation2021; Statistics Canada, Citation2017), with these differences persisting into adulthood (Halliday et al., Citation2019).

According to the WHO (Citation2018, Citation2021), mental health is defined as a “state of well-being in which every individual realizes [their] own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively, fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to [their] community”. According to Keyes (Citation2002), mental health can be represented on a two-continua model, whereby mental health (i.e., positive–negative) and mental conditions (i.e., presence–absence) are two distinct yet related constructs. This distinction is important as the absence of mental conditions does not necessarily equate positive mental health (i.e., emotional/ hedonic, social/eudaimonic, and psychological/eudaimonic wellbeing; Keyes, Citation2006). Likewise, the presence of mental conditions does not necessarily equate to negative mental health. Thus, it is important to investigate mental health in manners that account for different mental health profiles.

Adolescent sport participation has been linked to positive mental health, with high school sports in particular having been shown to have much potential for fostering wellbeing given that they are offered as an extension of the classroom and intended to promote young people’s healthy development (Sulz et al., Citation2021). In Canada, more than 750,000 adolescents ages 13–18 years voluntarily participate in a wide range of school sponsored individual and team sports (Camiré, Citation2014; Camiré & Kendellen, Citation2016). Research supports the protective effects of high school sport participation on the mental health of adolescents (e.g., Ashdown-Franks et al., Citation2017; Eime et al., Citation2013; Jewett et al., Citation2014). For instance, Jewett et al. (Citation2014) surveyed 853 Canadian high school students and found that high school sport participation was inversely associated with self-reported depression and stress and positively associated with self-reported mental health into young adulthood. Nonetheless, Sulz et al. (Citation2021) surveyed 120 Canadian school athletic directors and coaches who expressed a need for a culture shift to improve adolescents’ sport experiences by accentuating fun, mental health, and wellbeing. This need for a culture shift opens questions on how to optimise sport’s contribution to adolescent mental health.

Self-determination theory (SDT), and basic psychological needs theory (BPNT) as a sub-theory, are robust frameworks to understand how sport can be optimised to positively influence adolescent mental health. Indeed, positive mental health is said to transpire when humans act out of intrinsic motivation that is stimulated by the satisfaction of three basic psychological needs (i.e., autonomy, competence, and relatedness) that are posited as antecedents to the optimal expression of human potentials (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Specifically, the degree to which the three basic psychological needs are satisfied or frustrated influences the extent to which motivation, falling on a continuum, is controlled (i.e., amotivation) or self-determined (i.e., intrinsic motivation), which affects mental health and wellbeing (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Although sport is often deemed a context/activity in which adolescents are generally autonomously motivated to give their time and energy (Bedard et al., Citation2020), sport’s contribution to adolescent mental health is dependent on the degree to which needs satisfaction occurs in sporting environments, thereby affecting self-determination (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). That is, although participation in sport is often intrinsically motivated, when extrinsic rewards take precedent (e.g., overemphasis on winning) and are reinforced by coaches, parents, or peers (i.e., absence of needs satisfaction, frustration of needs), it can prompt a shift from an internal to an external sense of control, dampening self-determination and negatively influencing adolescents’ mental health (Deci & Ryan, Citation2000).

The basic psychological needs are deemed universally applicable to all humans. Just as humans require their physical needs (e.g., oxygen, food, water) to be satisfied to survive, so too must all three basic psychological needs be satisfied for positive mental health to actualise (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). However, unlike physical needs, humans may not be persistent in their attempts to satisfy their basic psychological needs when these needs are frustrated, resulting in compensatory, defensive, and/or apathetic behaviours leading to negative mental health and mental conditions (e.g., eating disorders; Deci & Ryan, Citation2000). Although the absence of basic psychological needs satisfaction was originally posited to predict mental conditions (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000), Bartholomew et al. (Citation2011) found that needs satisfaction and frustration were two distinct constructs, with needs frustration resulting in mental conditions and negative mental health (Bartholomew et al., Citation2011). Therefore, needs satisfaction and needs frustration were situated as two distinct constructs.

In a study examining needs satisfaction and needs frustration, Cronin et al. (Citation2019) surveyed 407 English and Irish students aged 12–17 years and found that their perceptions of their physical education teachers’ autonomy support were positively related to their reported needs satisfaction. Moreover, students’ perceptions of their teachers’ autonomy frustration were positively related to their reported needs frustration. These findings indicate that while high school sport has the potential to positively influence adolescents’ development, further research should examine more closely how sporting environments can promote needs satisfaction and forestall needs frustration, with particular attention paid to the influence of gender, given the divergent mental health profiles of girls and boys (Bailey et al., Citation2009).

Gender is a complex sociocultural construct that influences and characterises individuals’ perceptions, beliefs, experiences, behaviours, presentations, roles, and identities as girls, boys, and gender diverse (Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Citation2020; WHO, Citationn.d.). Importantly, gender identity is said to intensify during adolescence, which can have important influences on mental health (Priess & Lindberg, Citation2011; Steensma et al., Citation2013). As Metcalfe (Citation2018) stated, sport as a sociocultural context/activity represents a space where the traditional boy/girl binary is constantly reinforced. Specifically, Metcalfe (Citation2018) discussed how sport participants felt “trapped” (i.e., controlled) by the stereotypes associated with girl and boy identities that were most often conflated with sex. Furthermore, sport sustained ideals of “masculinity” that were incongruent with “femineity”, strongly impacting adolescents’ self-determination. Despite reported gender differences in adolescent mental health (Doré et al., Citation2019), little is known as to the ways that gender might impact adolescent student-athletes’ basic psychological needs as determinants of mental health.

Recent calls have been made for gender to be considered a key variable when studying the basic psychological needs of adolescent sport participants. For example, Bean et al. (Citation2021) investigated programme quality (i.e., basic psychological needs satisfaction and mental wellbeing) with 170 Canadian adolescent competitive sport athletes. While the researchers found that mental health scores did not differ on gender, they reported that the small sample size limited their ability to detect gender differences based on power. Consequently, they encouraged future research with larger samples to examine the role of gender more closely in relation to the basic psychological needs of adolescent athletes. For their part, Adie et al. (Citation2008) investigated the relationship between coach autonomy support, basic needs satisfaction, and well-being with 539 older adolescents and emerging adults in the UK. When testing if the model was equivalent between genders, they found that the model was not fully invariant, stating that “Drawing from the present findings, it appears that it is not necessary for coaches to consider an athlete’s gender when working to develop an autonomy supportive environment aimed at facilitating basic need satisfaction […]” (p. 197). More recently, Ghorbani et al. (Citation2020) examined Iranian adolescent boys’ and girls’ participation in physical activity and sport in relation to the basic psychological need of competence, with enjoyment as a mediator. The researchers found that perceived competence positively and significantly predicted in- and out-of-school physical activity and sport but that enjoyment only acted as a mediator of these relationships for boys. Moreover, boys had significantly higher levels of perceived competence than girls. Findings from Ghorbani et al. (Citation2020) corroborate Ryan and Deci’s (Citation2000) assertion that the basic psychological needs may differ in how they are experienced across cultures and based on variables such as gender.

Study purpose

Sport participation has been shown to lead to developmental benefits when practiced in appropriately structured, quality environments (Bean et al., Citation2021), such as high school sport (Jewett et al., Citation2014). However, it must be noted that positive mental health levels are generally lower in girls than boys, with a notable decline at adolescence, evincing a gender gap. As Halliday et al. (Citation2019) pointed out, despite a gender gap, little research has directly investigated the influence of gender on the mental health of adolescent sport participants. Given the relationship between the three basic psychological needs and mental health (Bean et al., Citation2021; Cronin et al., Citation2019), it is important to investigate gender differences in relation to basic psychological needs satisfaction and frustration. Thus, the purpose of the study was to investigate the influence of gender on the relationship between the satisfaction and frustration of the three basic psychological needs and mental health in high school student-athletes. The study contributes to the literature by directly assessing how gender affects the relationship between the three basic psychological needs and mental health in a large sample of Canadian adolescents. Based on girls’ lower sport participation rates and poorer mental health profiles compared to boys (Campbell et al., Citation2021; Statistics Canada, Citation2017), we hypothesised that girls would have lower levels of positive mental health and that the relationship between the three basic psychological needs and mental health would differ based on gender.

Method

Participants

The study received ethical approval from the University of Ottawa’s Research Ethics Board (approval number H-05-19-3982) and is part of a larger 5-year research project investigating the psychosocial development and mental health of Canadian student-athletes as they transition from adolescence to early adulthood. The data for the present study were collected through an online survey administered in year one (i.e., 2019–2020 school year) of the larger research project. A total of 2,332 student-athletes opened the online survey in year one. After removing student-athletes who did not consent, dropped out, or did not meet the inclusion criteria, the sample was comprised of 925 student-athletes, 421 who identified as boys (46%) and 504 who identified as girls (54%). The survey included student-athletes from all 10 Canadian provinces, with the most practiced sports being volleyball (n = 263, 26%), basketball (n = 136, 15%), and soccer (n = 113, 12%). Please see for additional participant demographics.

Table 1. Sample demographic information (n = 925).

Variables and instruments

The student-athletes completed an online survey inclusive of the variables of interest, namely the independent variables (IVs) of the three basic psychological needs, the dependent variable (DV) of mental health, and the moderator of gender.

Gender

To measure gender, one survey question was posed (i.e., “What gender do you identify with?”). Five student-athletes who answered Prefer Not to Answer or Please Specify were removed, resulting in two categorical levels assigned (i.e., 0 = boy; 1 = girl).

Basic psychological needs

To measure the basic psychological needs, the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS; Chen et al., Citation2015) was used. The scale consists of 24 items related to the satisfaction and frustration of autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Student-athletes reported the degree to which they experienced each item in their lives on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Not True at All) to 5 (Completely True). Example items include: “I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake” (autonomy satisfaction); “I feel that the people I care about also care about me” (relatedness satisfaction); “I feel confident that I can do things well” (competence satisfaction); “Most of the things I do feel like ‘I have to’” (autonomy frustration); “I feel excluded from the group I want to belong to” (relatedness frustration); and “I have serious doubts about whether I can do things well” (competence frustration). Participant scores were summed for each subscale: autonomy satisfaction (.72), competence satisfaction (.74), relatedness satisfaction (.82), autonomy frustration (.81), competence frustration (.84), and relatedness frustration (.83). Internal consistency reliability varied between acceptable and good.

Mental Health Continuum – Short Form

To measure mental health, the Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes, Citation2006; Keyes et al., Citation2008), was used. The scale consists of 14 items related to emotional, social, and psychological wellbeing. Student-athletes reported the frequency to which they experienced each item in the past month on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (Never) to 6 (Every Day). For example, “feel happy” (hedonic – emotional wellbeing), “feel that you had something important to contribute to society” (eudaimonic – social wellbeing), and "feel that you liked most parts of your personality” (eudaimonic – psychological wellbeing). Participant scores were summed, with a maximum score of 84 indicating the highest level of wellbeing (or positive mental health; Keyes et al., Citation2008). To be classified as flourishing, participants must report “Every Day” or “Almost Every Day”, for at least seven of the items under the hedonic cluster. To be classified as languishing, participants must report “Never” or “Once or Twice”, for at least seven of the total items, inclusive of one item under the hedonic cluster. Participants who are not classified as flourishing or languishing based on these criteria, are classified as “moderately mentally healthy” (Keyes et al., Citation2008, p. 187). Within our sample, internal consistency reliability was α = .93.

Preliminary analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted with SPSS® 27 software (IBM, Citation2020). Proportions and patterns of missing data for the scales were assessed. Data were considered to be missing completely at random, as denoted by non-significant results for Little’s missing completely at random test of equal variance for each scale. Item-level missingness varied between 0 and 0.4%; with most items having no missing information. Missing data were imputed using multiple imputations (Schlomer et al., Citation2010). Missing values for demographic variables were not imputed.

Regarding our main variables of interest, scores on the MHC-SF varied between 14 and 84, with a mean of 36.01 (SD = 13.73), suggesting that the student-athletes were moderately mentally healthy (Keyes, 2008). Mean scores ranged from 15.50 to 16.50 for satisfaction and between 8.43 and 10.65 for frustration. Data for the IVs and the DV were considered normally distributed as values for skewness and kurtosis were within ±2.0 (George & Mallery, Citation2018).

Assumptions for moderation analyses with a dichotomous moderator were tested. Specifically, we ensured that the DV was continuous, and that the moderator was binary and coded as 0 and 1. Using both statistical and visual analyses, we assessed the linearity between each of the six IVs and the DV for both groups of the moderator variable. When assessing the linearity between the IVs and the DV, the subscale scores on the MHC-SF served as the IV, mental health as the DV, and gender (0 = boy; 1 = girl) as the moderator. We also tested independence of residuals, normality of distribution of residuals, and homoscedasticity. The assumption of multicollinearity was not relevant since the model tested only included one continuous IV. All assumptions were considered satisfied.

Sociodemographic (i.e., excluding gender) and sport-related variables were tested using bilateral independent samples t-test analyses to identify any significant predictors of the IVs and the DV that should be included in the analyses as covariates. No significant predictors were identified. As such, we did not include any covariates in our main analyses. Sample descriptives of the IVs and the DV for the full sample and for both genders are presented in .

Table 2. Sample descriptive of the independent and dependent variables for the full sample, girls, and boys.

Main analyses

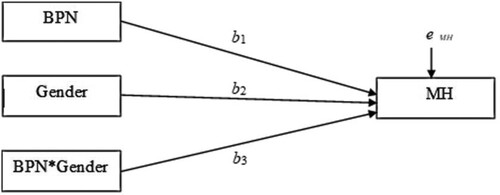

Main analyses included six moderation analyses: one for each of the three basic psychological needs as it relates to frustration and satisfaction. For each analysis, the score for each basic psychological need subscale of the BPNSFS (e.g., competence satisfaction, competence frustration) was used as the IV and the score on the MHC-SF was used as the DV. Gender (0 = boy; 1 = girl) served as the moderator. The scores for the IVs were mean centred (also referred to as centreing; Field, Citation2018). Centreing facilitates interpretation of the coefficients of lower-ordered terms (e.g., the conditional effect of the DV and the moderator variable; Field, Citation2018). We ran the main analyses in SPSS® 27 using the PROCESS version 3.5.3 macro, a tool for modelling ordinary least squares and regression path analyses (Hayes, Citation2019). PROCESS offers an output with the conditional effect of all terms in the statistical model tested as well as the constant. Specifically, b1 is the relationship between the IV and the DV when the moderator has a null value (i.e., which in our analyses represents boy student-athletes), b2 is the relationship between the moderator variable and the IV when the value of the DV is 0, b3 represents the interaction effect (i.e., the slope) between the moderator and the DV and ePMH is the residual variance of the IV (Hayes, Citation2018). Please see for the model of the moderation effect.

Figure 1. Statistical model of the moderation effect. Notes. BPN = Basic Psychological Needs subscale score; MH = Mental Health Continuum – Short Form score.

If a significant interaction effect is found, a probing procedure is implemented to assess if the conditional direct relationship between the IV and the DV is significant for both groups of the dichotomous moderator variable. When a binary moderator is of interest, PROCESS automatically implements the pick-a-point procedure to probe the interaction within the linear model (Hayes & Matthes, Citation2009; Hayes, Citation2018) for both values of the moderator (i.e., 0 [boy] and 1 [girl]). The macro also extracts the coefficients for each group, making it possible to compare the size of the respective effect between the IV and DV between groups. The interpretation of the tested moderation effect was also supported by a visual analysis of the simple slopes.

Results

Below, the results for each analysis are presented. Specifically, the three models for satisfaction are described, followed by the three models for frustration.

Basic psychological needs satisfaction

Autonomy

The overall model testing the moderation effect of gender on the relationship between autonomy satisfaction and student-athletes’ self-reported mental health was statistically significant, F(3, 921) = 90.14, p < .001, R² = .23. As depicted by the R2 value, the model accounted for 22.7% of the variance. The conditional direct effect of autonomy satisfaction on mental health when gender was constricted to 0 (i.e., boy) was significant and positive, β = 2.12, 95% CI [1.72; 2.51], t = 10.53, p < .001. Also, the conditional direct relationship of gender on mental health when BPN satisfaction (centred) was constricted to 0 was significant and negative, β = −2.59, 95% CI [−4.15; −1.02], t = −3.24, p = .001. The regression coefficient for the interaction term of autonomy satisfaction*gender was positive but non-significant, β = −.38, 95% CI [−0.19; 0.94], t = 1.31, p = .192, suggesting that the effect of BPN satisfaction on mental health was not moderated by gender. Thus, we did not implement the probing procedure.

Relatedness

The model testing the moderation effect of gender on the relationship between relatedness satisfaction and mental health was statistically significant, F(3, 921) = 138.29, p < .001, R² = .31, explaining 31.1% of the variance. The conditional direct effect of relatedness satisfaction on mental health when gender was constricted to 0 was significant and positive, β = 2.38, 95% CI [2.02; 2.73], t = 13.16, p < .001. Additionally, the conditional direct effect of gender on mental health when relatedness satisfaction (centred) was constricted to 0 was negative and significant, β = −3.32, 95% CI [−4.80; −1.84], t = −4.40, p < .001. The regression coefficient for the interaction term of relatedness satisfaction*gender was positive but non-significant, β = 0.36, 95% CI [−0.14; 0.87], t = 1.42, p = .155, suggesting that the effect of BPN satisfaction on mental health was not moderated by gender. Thus, we did not implement the probing procedure.

Competence

The model testing the moderation effect of gender on the relationship between competence satisfaction and mental health was statistically significant, F(3, 921) = 122.97, p < .001, R² = .29. As depicted by the value of R2, the model accounted for just over 28.6% of the variance. The conditional direct effect of competence satisfaction on mental health when constricting gender to 0 was significant and positive, β = 2.23, 95% CI [1.85; 2.60], t = 11.63, p < .001. Additionally, the conditional direct relationship between gender on mental health when competence satisfaction (centred) was constricted to 0 was non-significant, β = 1.14, 95% CI [−2.66; 0.38], t = −1.47, p = .141. The regression coefficient for the interaction term of competence satisfaction*gender was positive but non-significant, β = 0.42, 95% CI [−0.09; 0.93], t = −1.61, p = .108, suggesting that the effect of BPN satisfaction on mental health was not moderated by gender. Thus, we did not implement the probing procedure.

Basic psychological needs frustration

Autonomy

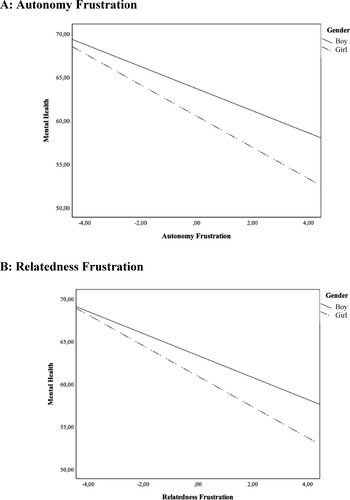

The overall model estimating the moderation effect of gender on the relationship between autonomy frustration and student-athletes’ self-reported mental health was statistically significant, F(3, 921) = 67.65, p < .001, R² = .18. The model explained 18.1% of the variance. The conditional direct effect of autonomy frustration on mental health when gender was constricted to 0 (i.e., boy) was significant and negative, β = −1.27, 95% CI [−1.60; −0.94], t = −7.57, p < .001. Additionally, the conditional direct relationship between gender on student-athletes’ self-reported mental health when autonomy frustration (centred) was constricted to 0 was significant and negative, β = −3.16, 95% CI [−4.77; −1.54], t = −3.84, p < .001. The regression coefficient for the interaction term of autonomy frustration*gender was negative and significant, β = −0.52, 95% CI [−0.97; −0.08], t = −2.28, p = .022, indicating that boys and girls differed in their relationship between autonomy frustration and mental health. Thus, we probed the interaction within the linear model, which indicated that the relationship for both boy and girl student-athletes was significant and negative; βboy = −1.27, 95% CI [−1.60; −0.94], t = −7.57, p < .001; βgirl = −1.80, 95% CI [−2.10; −1.49], t = −11.57, p < .001. These results reveal that higher levels of autonomy frustration (i.e., practices in sporting environments that frustrate student-athletes’ autonomy) predicted lower levels of positive mental health and that this relationship was stronger for girls than for boys. presents the simple slopes for the relationship between autonomy frustration and mental health for both groups.

Figure 2. Simple slope graphs for significant moderation effects. (A) Autonomy frustration. (B) Relatedness frustration. Notes. The above figures represent the simple slopes for gender based on the regression between Basic Psychological Needs autonomy and relatedness frustration subscales and scores on the Mental Health Continuum – Short Form scores. Higher scores on the Mental Health Continuum – Short Form represent a higher positive mental health. Higher scores on the frustration subscales represent higher levels of basic psychological needs frustration.

Relatedness

The overall model estimating the moderation effect of gender on the relationship between relatedness frustration and student-athletes’ mental health was significant, F(3, 921) = 70.52, p <.001, R² = .20. The model explained 20.4% of the variance. The conditional direct effect of relatedness frustration on mental health when gender was constricted to 0 was significant and negative, β = −1.29, 95% CI [−1.59; −0.99], t = −8.51, p < .001. Also, the conditional direct relationship between gender on student-athletes’ self-reported mental health when relatedness frustration (centred) was constricted to 0 was significant and negative, β = −2.44, 95% CI [−4.03; −0.85], t = −3.01, p = .003. The regression coefficient for the interaction term of relatedness frustration*gender was negative and significant, β = −0.51, 95% CI [−0.92; −0.09], t = −2.41, p = .016, indicating that boys and girls differed in their relationship between relatedness frustration and mental health. We thus probed the interaction within the linear model, which indicated that the relationship for both boy and girl student-athletes was significant and positive; βboy = −1.29, 95% CI [−1.59; −0.99], t = −8.51, p < .001; βgirl = −1.80, 95% CI [−2.09; −1.51], t = −12.28, p < .001. Results suggest that higher levels of relatedness frustration predicted worse levels of mental health and that this relationship was stronger for girls than for boys. As with autonomy frustration, practices in sporting environments that frustrated student-athletes’ relatedness resulted in poorer mental health outcomes in girls than in boys. presents the simple slopes for the relationship between relatedness frustration and mental health for both groups.

Competence

The model measuring the moderation effect of gender on the relationship between competence frustration and mental health was significant, F(3, 921) = 61.62, p < .001, R² = .29, explaining more than 28.6% of the variance. The conditional direct effect of competence frustration on mental health when gender was constricted to 0 was significant and negative, β = −1.49, 95% CI [−1.74; −1.23], t = −11.27, p < .001. Additionally, the conditional direct relationship between gender on participants’ self-reported mental health when BPN frustration (centred) was constricted to 0 was significant and negative, β = −1.63, 95% CI [−3.14; −0.12], t = −2.11, p < .001. The regression coefficient for the interaction term of competence frustration*gender was positive and but not significant, β = −0.34, 95% CI [−0.69; 0.01], t = −1.91, p = .056. Thus, we did not implement the probing procedure.

Discussion

The purpose of the study was to investigate the influence of gender on the relationship between the satisfaction and frustration of the three basic psychological needs and mental health in high school student-athletes. The results suggest that the relationship between the satisfaction of all three basic psychological needs and student-athletes’ mental health was positive and significant. Thus, when student-athletes’ needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competency were satisfied, they reported higher levels of emotional, social, and psychological wellbeing. The relationship between the frustration of all three basic psychological needs and mental health was significant and negative. These results suggest that the frustration of autonomy, relatedness, and competence had a negative impact on student-athletes’ emotional, social, and psychological wellbeing.

Although girls had significantly lower positive mental health scores than boys (see ), gender was only found to moderate two out of the six tested relationships (i.e., autonomy frustration, relatedness frustration). When comparing the regression coefficients for boy and girl student-athletes within these models, we found that the relationship was always stronger for girls, but the direction of the relationships for both groups was the same. Such findings are consistent with previous research indicating that girls’ mental health outcomes are more strongly negatively impacted by environmental factors (e.g., peer-related interpersonal stress, lack of social support) than boys’ mental health outcomes (Rudolph, Citation2002; Van Droogenbroeck et al., Citation2018). This highlights the importance of having key stakeholders within sporting environments avoiding adopting practices that frustrate athletes’ autonomy and relatedness, especially when working with girls. A high-level assessment of our results suggest that quality sporting environments can maximise needs satisfaction but also inhibit needs frustration, which together contribute to positive mental health outcomes for student-athletes (Leversen et al., Citation2012; Vansteenkiste et al., Citation2020).

Research implications

This study contributes to advancing knowledge on the relationship between the basic psychological needs and mental health by addressing calls for examining the influence of gender on this relationship (Bean et al., Citation2021). Our results suggest, in alignment with Bartholomew et al. (Citation2011), that the satisfaction and frustration of each basic psychological need are not inversely proportionate. Specifically, the relationship between autonomy satisfaction and mental health in absolute value was stronger than the relationship between autonomy frustration and mental health, adding weight to the argument that needs satisfaction and needs frustration should be treated as separate constructs. As stated by Vansteenkiste and Ryan (Citation2013, pp. 264–265):

A distinction needs to be made between the lack of fulfillment of the needs and the experience of need frustration, the relation between both being asymmetrical. That is, low need satisfaction does not necessarily involve need frustration, yet, need frustration by definition involves low need satisfaction. The difference between both is a critical issue as unfulfilled needs may not relate as robustly to malfunctioning as frustrated needs may.

It is thus essential to identify attitudes and practices that satisfy student-athletes’ basic psychological needs, as well as avoid those that frustrate their needs.

Practical implications

Although the present study was cross-sectional in nature, making it impossible to verify directionality, the results support the creation of sporting environments that foster needs satisfaction and inhibit needs frustration, ultimately leading to the promotion of positive mental health. High school sport is a context that can strongly influence adolescents during a pivotal development period, thus affecting their mental health trajectories. Sporting environments should therefore be offered as safe spaces that foster student-athletes’ basic psychological needs known to be critical to their mental health (Chu & Zhang, Citation2019).

Study results also underscore how gender is an important element to consider when working to create need-supportive sporting environments intended to foster adolescents’ positive mental health. Our results, consistent with those of previous research (e.g., Zarrett et al., Citation2020), indicated that student-athletes who identify as girls and who experienced autonomy frustration and relatedness frustration were susceptible to experiencing lower mental health. As discussed by Metcalfe (Citation2018), adolescent participants have and continue to endure discriminatory gendered practices and values in sport. Our results highlight that when working with girls, special attention should be given to satisfying all three basic psychological needs while also being very careful not to frustrate their autonomy and relatedness (Zarrett et al., Citation2020). Such dual objectives of increasing needs satisfaction while reducing needs frustration should coincide with practices that intentionally challenge youth sport’s rigid gendered scripts in relation to notions of femineity and masculinity (Metcalfe, Citation2018; Schull & Kihl, Citation2019). Girls should be provided opportunities to practice sport and be themselves without pressures to think and behave in constrictive ways (i.e., autonomy; Deci & Ryan, Citation2012) while feeling supported and included when doing so (i.e., relatedness). Adult leaders within youth sport should have access to proper training on creating sporting environments satisfying their athletes’ basic psychological needs. Once trained, adult leaders should be provided with practical tools (e.g., the Life Skills Self-Assessment Tool; Kramers et al., Citation2022), allowing them to regularly and actively monitor how they are creating sporting environments that support student-athletes’ development and wellbeing.

Strengths and limitations

The study presents two main strengths and limitations. First, while a majority of research on mental health has focused on mental health conditions (Keyes, Citation2002; Citation2006), the present study took a different path and investigated mental health in connection to the basic psychological needs. Specifically, using the BPNSF scale, we examined both the satisfaction and frustration of each basic psychological need, rather than basic psychological needs as a composite, in connection to student-athletes’ mental health (Chen et al., Citation2015). It is important to note that we did not specifically measure student-athletes’ high school sport experiences but rather examined their general life experiences with the stem “at this point in your life”. This enabled us to account for adolescents participating in one or more high school sport, which comprised 60.2% of the student-athletes in our sample. Future research may consider sport-specific adaptations to the questionnaire, such as the circumplex model that investigates sport coaching practices in connection to need supporting and thwarting, surveying both coaches and athletes (i.e., Delrue et al., Citation2019), that may then be measured in association with mental health. Additionally, because basic psychological needs satisfaction and frustration were measured at a single time point, we could not detect possible highs and lows in satisfaction and frustration occurring over the course of a sport season, which previous research has found (e.g., Balaguer et al., Citation2012). Therefore, future research should consider integrating a repeated measure, longitudinal design that would yield a more global sense of each of these measures as they related to student-athletes’ mental health.

Second, the study was conducted using a large Canadian sample of adolescent high-school student-athletes. Studies on the satisfaction and frustration of the basic psychological needs in sport have traditionally collected data from coaches and less with adolescents, who are critical “tellers” of their perceptions of basic psychological need fulfilment and mental health.

Moreover, the sample was sufficiently large to allow us not only to look at direct relationships between variables, but also to take into account the interaction effect of two categories of gender identity. However, it must be noted that adolescents practicing high school sports in other countries may demonstrate different mental health trajectories. Future research should be conducted in countries extending beyond Canada to derive a more comprehensive international picture of the interplay of basic psychological needs, gender identity, and mental health. Furthermore, it is crucial to acknowledge that participants who did not specify a gender or identified with a gender other than boy or girl were excluded from our analyses due to the small sample size (n = 5). As a result, our sample was not representative in terms of gender diversity. Consistent with the definition of mental health inclusive of eudaimonia and hedonia, the ability to openly be and express one’s authentic self is fundamental. However, traditionally, the sport and research domains have perpetuated constricting gender binaries. Moving forward, it is imperative that purposeful recruitment efforts and research designs are deployed to include adolescents of various gender identities, allowing for a better understanding of mental health.

Conclusion

The study examined the relationship between basic psychological needs frustration and satisfaction and high school student-athletes’ mental health when considering the influence of gender. Consonant with theory and past research, results indicate how the satisfaction of the three basic psychological needs contributes to positive mental health. These results support the importance of creating needs-supportive environments for adolescents taking part in sport. Given how our results showed gender differences for autonomy frustration and relatedness frustration, gender should continue to be considered as an important variable within research designs, but move beyond its limiting binary delineation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, ST, upon reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adie, J. W., Duda, J. L., & Ntoumanis, N. (2008). Autonomy support, basic need satisfaction and the optimal functioning of adult male and female sport participants: A test of basic needs theory. Motivation and Emotion, 32(3), 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9095-z

- Ashdown-Franks, G., Sabiston, C. M., Solomon-Krakus, S., & O’Loughlin, J. L. (2017). Sport participation in high school and anxiety symptoms in young adulthood. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 12, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2016.12.001

- Bailey, R., Armour, K., Kirk, D., Jess, M., Pickup, I., & Sandford, R. (2009). The educational benefits claimed for physical education and school sport: An academic review. Research Papers in Education, 24(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520701809817

- Balaguer, I., González, L., Fabra, P., Castillo, I., Mercé, J., & Duda, J. L. (2012). Coaches’ interpersonal style, basic psychological needs and the well- and ill-being of young soccer players: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences, 30(15), 1619–1629. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2012.731517

- Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, N., Ryan, R. M., Bosch, J. A., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2011). Self-determination theory and diminished functioning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(11), 1459–1473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211413125

- Bean, C., McFadden, T., Fortier, M., & Forneris, T. (2021). Understanding the relationships between programme quality, psychological needs satisfaction, and mental well-being in competitive youth sport. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 19(2), 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1655774

- Beauchamp, M. R., Puterman, E., & Lubans, D. R. (2018). Physical inactivity and mental health in late adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry, 75(6), 543–544. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.0385

- Bedard, C., Hanna, S., & Cairney, J. (2020). A longitudinal study of sport participation and perceived social competence in youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 66(3), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.09.017

- Camiré, M. (2014). Youth development in north American high school sport: Review and recommendations. Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich), 66(4), 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2014.952448

- Camiré, M., & Kendellen, K. (2016). Coaching for positive youth development high school sport. In N. Holt (Ed.), Positive youth development through sport (2nd ed, pp. 126–136). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315709499-11

- Campbell, O., Bann, D., & Patalay, P. (2021). The gender gap in adolescent mental health: A cross-national investigation of 566,829 adolescents across 73 countries. SSM – Population Health, 13, 100742. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100742

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. (2020, April 28). What is gender? What is sex? Retrieved March 1, 2022, from https://cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48642.html

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1

- Chu, T. L., & Zhang, T. (2019). The roles of coaches, peers, and parents in athletes’ basic psychological needs: A mixed-studies review. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14(4), 569–588. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954119858458

- Costello, E. J., Mustillo, S., Erkanli, A., Keeler, G., & Angold, A. (2003). Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(8), 837–844. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837

- Cronin, L., Marchant, D., Allen, J., Mulvenna, C., Cullen, D., Williams, G., & Ellison, P. (2019). Students’ perceptions of autonomy-supportive versus controlling teaching and basic need satisfaction versus frustration in relation to life skills development in PE. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 44, 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.05.003

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, personality, and development within embedded social contexts: An overview of self-determination theory. In R. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 85–107). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0006.

- Delrue, J., Reynders, B., Broek, G. V., Aelterman, N., De Backer, M., Decroos, S., De Muynck, G.-J., Fontaine, J., Fransen, K., van Puyenbroeck, S., Haerens, L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2019). Adopting a helicopter-perspective towards motivating and demotivating coaching: A circumplex approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 40, 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.008

- Doré, I., Sabiston, C. M., Sylvestre, M.-P., Brunet, J., O’Loughlin, J., Nader, P. A., Gallant, F., & Bélanger, M. (2019). Years participating in sports during childhood predicts mental health in adolescence: A 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 64(6), 790–796. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018.11.024

- Eime, R. M., Young, J. A., Harvey, J. T., Charity, M. J., & Payne, W. R. (2013). A systematic review of the psychological and social benefits of participation in sport for children and adolescents: Informing development of a conceptual model of health through sport. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 10(1), 98. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-10-98

- Field, A. (2018). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS Statistics (5th ed.). Sage.

- George, D., & Mallery, P. (2018). Reliability analysis. In D. George & P. Mailery (Eds.), IBM SPSS Statistics 25 step by step (15th ed., pp. 249–260). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351033909

- Ghorbani, S., Nouhpisheh, S., & Shakki, M. (2020). Gender differences in the relationship between perceived competence and physical activity in middle school students: Mediating role of enjoyment. International Journal of School Health, 7(2), 14–20. https://doi.org/10.30476/intjsh.2020.85668.1056

- Halliday, A. J., Kern, M. L., & Turnbull, D. A. (2019). Can physical activity help explain the gender gap in adolescent mental health? A cross-sectional exploration. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 16, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2019.02.003

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford.

- Hayes, A. F. (2019). The PROCESS macro for SPSS, SAS, and R. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from http://processmacro.org/download.html

- Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

- IBM. (2020). IBM SPSS Statistics 27. Retrieved February 10, 2022, from https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/downloading-ibm-spss-statistics-27

- Jewett, R., Sabiston, C. M., Brunet, J., O’Loughlin, E. K., Scarapicchia, T., & O'Loughlin, J. (2014). School sport participation during adolescence and mental health in early adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(5), 640–644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.04.018

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

- Keyes, C. L. M. (2006). Mental health in adolescence: Is America’s youth flourishing? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(3), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.395

- Keyes, C. L. M., Wissing, M., Potgieter, J. P., Temane, M., Kruger, A., & van Rooy, S. (2008). Evaluation of the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) in Setswana-speaking South Africans. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.572

- Kramers, S., Camiré, M., Ciampolini, V., & Milistetd, M. (2022). Development of a life skills self-assessment tool for coaches. Journal of Sport Psychology in Action, 13(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2021.1888832

- Laporte, N., Soenens, B., Brenning, K., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2021). Adolescents as active managers of their own psychological needs: The role of psychological need crafting in adolescents’ mental health. Journal of Adolescence, 88(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.02.004

- Leversen, I., Danielsen, A. G., Birkeland, M. S., & Samdal, O. (2012). Basic psychological need satisfaction in leisure activities and adolescents’ life satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(12), 1588–1599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9776-5

- Metcalfe, S. (2018). Adolescent constructions of gendered identities: The role of sport and (physical) education. Sport, Education and Society, 23(7), 681–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2018.1493574

- Priess, H. A., & Lindberg, S. M. (2011). Gender intensification. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 1135–1142). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1695-2_391

- Rudolph, K. D. (2002). Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(4), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00383-4

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Schlomer, G. L., Bauman, S., & Card, N. A. (2010). Best practices for missing data management in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018082

- Schull, V. D., & Kihl, L. A. (2019). Gendered leadership expectations in sport: Constructing differences in coaches. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 27(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2018-0011

- Statistics Canada. (2017). Depression and suicidal ideation among Canadians aged 15 to 24. Retrieved January 12, 2022, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2017001/article/14697-eng.htm

- Steensma, T. D., Kreukels, B. P., de Vries, A. L., & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. (2013). Gender identity development in adolescence. Hormones and Behavior, 64(2), 288–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2013.02.020

- Sulz, L. D., Gleddie, D. L., Urbanski, W., & Humbert, M. L. (2021). Improving school sport: Teacher-coach and athletic director perspectives and experiences. Sport in Society, 24(9), 1554–1573. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2020.1755263

- Van Droogenbroeck, F., Spruyt, B., & Keppens, G. (2018). Gender differences in mental health problems among adolescents and the role of social support: Results from the Belgian health interview surveys 2008 and 2013. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1591-4

- Vansteenkiste, M., & Ryan, R. M. (2013). On psychological growth and vulnerability: Basic psychological need satisfaction and need frustration as a unifying principle. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 23(3), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032359

- Vansteenkiste, M., Ryan, R. M., & Soenens, B. (2020). Basic psychological need theory: Advancements, critical themes, and future directions. Motivation and Emotion, 44(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09818-1

- World Health Organization. (2018). Mental health: Strengthening our response. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response

- World Health Organization. (2021). Adolescent health. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1

- World Health Organization. (n.d.). Gender and health: Overview. Retrieved March 17, 2022, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/gender#tab=tab_2

- Zarrett, N., Veliz, P., & Sabo, D. (2020). Keeping girls in the game: Factors that influence sport participation. Women’s Sports Foundation. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED603915.pdf