ABSTRACT

Objective:

The study examined the effectiveness of applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training programmes for decreasing mood disturbance and burnout, improving confidence, and enhancing the spiritual realm of Chinese elite archery athletes.

Methods:

An ABA design was adopted. Sixteen elite archery athletes took part in an intervention, which consisted of (a) technique-oriented basic psychological skills training, (b) knowledge-oriented sport psychology knowledge education, and (c) vision-oriented cultural literacy formation. Profile of Mood States, Athletes Burnout Questionnaire, and State Sport-Confidence Inventory were employed to carry on monthly monitoring. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect qualitative data. The method of Nonoverlap of All Pairs (NAP), analyses of variance (ANOVAs), and a reflexive thematic analysis were used to calculate the effect sizes for the intervention.

Results:

For the majority of the participants, the findings of the current study demonstrated a medium to large effect of applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training on decreasing mood disturbance and burnout and improving confidence. Moreover, there seemed to be a stronger effect in the intervention than in the withdrawal phase. Qualitative data obtained revealed that psychological training not only helped athletes in the arena but also enhanced their spiritual realm.

Conclusion:

It can be viewed that applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training is very effective in improving elite Chinese archery athletes’ state of mind. In the future, it is suggested that more studies could be done to further contextualise, examine, and expound on the effectiveness of the spiritual realm in other sport-systems.

Archery is a representative type of relatively closed discipline. In particular, archery is known to be more psychologically affected than sports in other environments, hence qualifying it to be referred to as a mental sport (Kim et al., Citation2021). It has been documented that archery performance is linked with motivation, mental concentration, stress and anxiety management, self-confidence, and emotion control (Hung et al., Citation2008). Likewise, existing research indicated that psychological elements such as anger, anxiety, burnout, relief, happiness, and pride could be major factors in influencing athletes’ performance (Fronso et al., Citation2022; Lazarus, Citation2000). The current study demonstrated that confidence and achievement motivation are the most significant psychological skills required for the accomplishment of high archery scores and determined the discriminating psychological coping skills needed for archery performance (Taha et al., Citation2018). Given the importance and universality of the ability to properly be aware of and control one's mental state in archery performance, researchers are beginning to focus on training techniques or strategies that affect and improve the ability.

Psychological skills training (PST) refers to a technique or strategy for practicing and training psychological skills that help play games with a positive attitude, along to improve performance (Vidic, Citation2021). A recent meta-analysis on the effectiveness of psychological skills training interventions for archery athletes suggested significant improvements among participants in a total of 17 trials, which verified the effectiveness of psychological skills training for archery athletes (Kim et al., Citation2021). Western scholars (Vealey, Citation2007) and Eastern scholars (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2011) reached the consensus that PST has at least two goals: (a) to assist athletes in attaining their full potential and achieving excellent athletic performance; (b) to help athletes continue to concentrate on life development and to enable them to achieve long-term self-development.

There are huge differences between Eastern and Western cultures, which is manifested in the large gap in thinking patterns, personality traits, and behaviours between Chinese and Westerners. In addition, different competitive sports systems and athletes’ unique life experiences make some PST methods and psychological counselling models borrowed from the Western not fully applicable to Chinese athletes (Zhang & Li, Citation2019; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2011). Indeed, the pragmatical tendency of American psychological services makes athletes’ PST much more operable, measurable, and verifiable. For instance, image training, relaxation, goal setting, surrounding awareness, and routine setup all have a strong tendency to techniques(Hung et al., Citation2008), that is, the tendency of “skills (shu)” training, and this methodology is valued and welcomed by some coaches and athletes. But when some researchers tried to solve the psychological problems at critical moments of competitions, they discovered that there are always ultimate problems behind these emotional control, thought control, and attention control problems, including how to deal with success or failure, gains and losses, rewards and punishments, honour and disgrace; how to treat yourself and others, present and future, sports career and life afterward, etc. It can be summarised as the question of the “spiritual realm (Dao)” (Zhang et al., Citation2021).

“Shu” can take effect in a short period through psychological skills learning and training, while the improvement of “dao” can be achieved by relying on continuous enhancement of personal personality and continuous accumulation of cultural literacy, which is a long-term process of constant development of mental abilities (Zhang et al., Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2013; Zhang et al., Citation2021; Zhang & Li, Citation2019; Zhang & Li, Citation2019). Chinese traditional culture (especially Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism) emphasises that human beings are supposed to cultivate their morality in daily life and that the tiny and common things like clothes, food, shelter, transportation, sitting, sleeping, recreation, etc. could help mold ideal personality and nurture individuals’ spirit. Therefore, exploring the localisation of sport PST, absorbing psychological ideas from Chinese culture, and developing methods suitable for Chinese athletes’ PST will contribute to the development of sport psychology theory and practice.

Traditional Chinese philosophy believes that archery skills are easy to learn while archery spirit is difficult to attain; archery arts are easy to achieve but archery virtues are difficult to practice. Confucius said: “archery reflects on virtue.” Therefore, archery learning should focus on the cultivation of personality and virtue and the formation of ethics and value as the priority. Sometimes Western scholars emphasise the importance of operationalisation and skill aspects of psychological training (Brewer & Shillinglaw, Citation1992; Ridley, Citation1992). By contrast, Zhang and Zhang's (Citation2011) Psychological Development System places more emphasis on cultural orientation and the spiritual aspect of psychological training. Based on what we discussed above, Psychological Development System for Chinese Athletes (Zhang et al., Citation2021; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2011) was used as the theoretical basis, and “the combination of skill orientation and spirit orientation” was adopted as the guideline in this study to offer PST to Chinese national archery team. In the previous studies, questionnaires were used to evaluate the effectiveness of PST interventions, such as Profile of Mood States (Li & Zhang, Citation2020), Athletes Burnout Questionnaire (Gerber et al., Citation2018; Qui & Zhang, Citation2019), State Sport-Confidence Inventory (Li & Zhang, Citation2020; Martin & Gill, Citation1991). Some researchers have suggested that the evaluation of the effectiveness of psychological training should be diversified (Si, Citation2006). Therefore, to more comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness of PST, this research adopted a parallel mixed-method design, in which collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data were done.

Zhang and Zhang (Citation2011) constructed a localised theory entitled Psychological Development System for Chinese Athletes, dividing the athletes’ PST into three levels: (a) technique-oriented basic psychological skill training, which could be achieved using relaxation, imagery training, goal-setting training, and training-simulation; (b) knowledge-oriented psychology education, which could be conducted by offering lecturing and counselling services; (c) vision-oriented culture literacy formation, which can be realised by organising site-visiting, workshop, etc. Based on lessons from Western training theories and techniques, the current study also incorporated the essence of Chinese traditional culture and philosophy, making the PST of the Chinese archery team with more local characteristics and far-reaching significance, especially under the Covid-19 pandemic.

Method

Participants

This was a field intervention in the natural environment of a national-level elite archery team. 16 top Chinese elite athletes (8 male and 8 female) out of 102 competing in qualifiers for the Tokyo Olympics were adopted by this study. The sixteen participants represented the highest level of Chinese archery, meeting the elite athletes’ inclusion criteria. They had an average training period of 10.13 years (3∼16 years, SD = 3.42), with an average age of 22.83 years old (17.60∼30.50 years old, SD = 3.70). Research ethics committee approval was gained from the lead institution, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study design

We adopted a parallel mixed-method design, in which collection and analysis of both qualitative and quantitative data sets are carried out separately and the findings are not compared or consolidated until the interpretation stage.

Procedure

The basic strategy of a single-case study was to first acquire a stable baseline of participant performance (A1) through repeated assessments (from December 2019 to January 2020). The first author was assigned to a training base in Sichuan Province to provide Chinese archery team athletes with psychological services. During the first two months with the team, the main job of the author was to accompany the team members in their daily life and training and to establish good relationships with them. The athletes were asked to fill in the monthly questionnaire to monitor their psychological state. Second, the intervention phase data were collected during the treatment (from February 2020 to June 2020) (B). After the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, in February 2020, the coaching group asked for psychological training once a week. After the 5-month intervention, the first author left the Chinese archery team. Third, The withdrawal phase (A) consisted of establishing the postintervention baseline with data collected to determine whether any gains from the psychological training were maintained, from July 2020 to August 2020.

Data collection

Quantitative data collection

Profile of Mood States, Athletes Burnout Questionnaire, and Sport State Confidence Questionnaire were employed to carry on monthly monitoring from February 2020 to August 2020. Each test was conducted after the archery technique training session in the last week of each month. These tests could distinctly reflect the psychological state of participants in the age of the pandemic and objectively justify the role played by our psychological training.

Profile of mood states (POMS)

The POMS was used to measure a person’s relatively stable and long-lasting emotional state. It consists of 40 items and 7 dimensions (e.g., tension, anger, fatigue, depression, vigour, confusion, and ego). Total mood disturbance (TMD) = negative emotion (tension + anger + fatigue + depression + panic)-positive emotion (energy + self-esteem) + 100 (Zhang et al., Citation2013). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true). The TMD score ranges from 74 to 234. The higher TMD score was considered to represent the negative mood states of each participant. POMS has an acceptable factor structure and internal consistency (α = 0.57∼0.85)for use in a sports setting (Li et al., Citation2022; Lin & Zhang, Citation2008; Zhu, Citation1995).

Athletes burnout questionnaire(ABQ)

Athlete burnout is a psychological syndrome characterised by feelings of physical and emotional exhaustion (PEE), a reduced sense of accomplishment (RSA) in sports, and sport devaluation (SD) (Zhang et al., Citation2013). ABQ contains 15 items, and a 5-point Likert scale is used to indicate the degree of difference between low athletes’ burnout (1 point) to high athletes’ burnout (5 points) (Zhang & Mao, Citation2007; Zhang & Bi, Citation2009). Athletes Burnout score = (PEE + RSA + SD)/3. The total score ranges from 5 to 25. The ABQ has an acceptable factor structure and internal consistency (α = 0.72∼0.75) (Gerber et al., Citation2018; Lin & Zhang, Citation2008; Qui & Zhang, Citation2019). The total score for each participant was considered to represent his or her level of sport-confidence.

State sport-confidence inventory(SSCI)

The Chinese vision of SSCI has been validated among the elite athletes in China and used to measure the belief and degree of confidence that one can succeed in competitive sports (Zhang et al., Citation2013). It contains a total of 13 items rated on a 9-point Likert scale to indicate various degrees of confidence from low self-confidence (1 point) to high self-confidence (9 points) (Zhang & Mao, Citation2007). The total score ranges from 13 to 117. The total score for each participant was considered to represent his or her level of sport-confidence. The SSCI has an acceptable internal consistency(α = 0.95) (Li & Zhang, Citation2020; Martin & Gill, Citation1991).

Subjective evaluation of intervention effects

The self-developed Subjective evaluation of intervention effects was used to measure the athletes’ satisfaction level with psychological training, such as general arrangement, specific content, and regular evaluation of the training effectiveness. The effectiveness of each psychological training is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never or very rarely true) to 5 (very often or always true).

Qualitative data collection

Athletes were required to complete a semi-structured interview used to measure what they had learned after each educational class. An interview guide was generated to facilitate the discussion: this guide included questions such as “Could you share with us what you have learned?”, “What do you think of the effectiveness of this class in improving your mood?”, “Could you talk about the role of this psychological training in improving your sporting performance?”, “How do you view the impact of this training programme on your long-term self-development?” In the following week’s intervention, the information on this interview was discussed with the athletes to make sure they really understood the contents. Furthermore, questions from the athletes were also discussed with the coach with the athletes’ permission, resulting in large and qualitatively rich data. Each interview was recorded and then transcribed verbatim by the first author. To assure the anonymity of participants, all information about the identity of the participants was excluded from the transcribed interview and each participant was assigned a pseudonym.

Intervention

Intervention fidelity

The intervention was conducted by the first author, an accredited sports psychology practitioner who has been working with Chinese national sports teams for five years. The first author is a Ph.D. student, majoring in sport psychology. Measures were adopted to guarantee the effectiveness of this programme. For example, the whole process of intervention was supervised and guided by three teachers from the School of Psychology of a sports university in China.

Intervention duration

In the intervention, all sixteen participating athletes attended weekly psychological training sessions for five months in a row, lasting between 60 and 90 min each (Kim et al., Citation2021). technique-oriented basic PST, knowledge-oriented sport psychology knowledge education and vision-oriented cultural literacy formation should all be included in the four-times-per-month psychological training programme. The whole arrangement of the schedule was decided by the researcher and the coach to fit with their training programmes.

Intervention content

The context for the intervention was drawn from Psychological Development System for Chinese Athletes (Zhang & Zhang, Citation2011). Each intervention course had its theme (See ). An assignment to report on the Subjective evaluation of intervention effects was done after every class.

Table 1. Psychological training plan for the Chinese national archery team.

Technique-oriented basic psychological skill training

PST (For example, imagery training, relaxation training, self-confidence training and so on) were applied in this study. Due to the limited length of the article, the following is a brief introduction to how relaxation training was conducted. From February to June 2020, the author conducted relaxation training, a total of five times, for athletes using the Self-generate Physiological Coherence System, which scientifically quantifies one’s physiological and psychological state based on the human heart rate variability (HRV) and its frequency domain characteristics. The Self-generate Physiological Coherence System helped coaches monitor the athletes’ general state during ordinary training or pre-match training. Through playing archery games, comprehensive scores were given to measure this ability. The athletes with higher comprehensive scores were shown to be more capable of relaxing. This system has shown good reliability and validity among athletes (Bu et al., Citation2019; Moussavi Esterabadi Kermani & Birjandi, Citation2019; Yang & Zhang, Citation2014).

Knowledge-oriented sport psychology knowledge education

A total of 5 lectures were given to participants from the Chinese archery team focusing on common psychological adjustment issues in training and competition, including boosting motivation, maintaining self-confidence, controlling emotions, coping with adversity, focusing attention, dealing with accidents, enhancing team cohesion, etc.

From February 1st to May 1st, 2020, the author updated and shared with participants the column of “Psychological Adjustment of Athletes Preparing for the Olympic Games in Response to the Covid-19” on the WeChat public account of the School of Psychology of Beijing Sport University every day, with a total of 90 issues. The main content of the column covered aspects such as coping with pressure, training psychological adjustment, psychological preparations for competitions, etc., which aimed to help participants understand the methods and basic principles of psychological training.

Vision-oriented cultural literacy formation

Some studies have found that exemplar Priming can largely reduce athletes’ anxiety levels (Zamora, Citation2015). On February 25th, 2020, the authors of the study organised a speech contest with the topic of “Excellent Athlete in My Mind” around which 16 participants relived the happy moments of their idols when they achieved good sporting results and reviewed the struggling period after they fell into the trough of their career. During the speech contest, the participants spoke out about how their idols encouraged them to train and fight very hard from different perspectives, with vivid examples and full enthusiasm.

Under closed-loop management circumstances, athletes faced complicated interpersonal relationships, but multiple relationships may also be the starting point for overcoming difficulties. Because athletes need to obtain social support from significant others such as coaches, parents, and teammates (Knight et al., Citation2018; Scott et al., Citation2021). This support affects athletes’ cognitive, emotional and behavioural performance (Brown et al., Citation2018; Cranmer & Sollitto, Citation2015; Hagiwara et al., Citation2017). During the psychological training, the author called on participants to write a “Thanks-giving letter” to provide them with an opportunity to express gratitude, enhance communications and strengthen the social support system. The motivational function of gratitude helps people to form close social connections (McCullough et al., Citation2008). According to the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions, the positive emotion of gratitude could improve the behaviour and cognition of the individual, and enhance the interaction mode between the individual and the external environment. Thus this emotion is conducive to the establishment of a supportive social system and helps people feel stronger support from others (Fredrickson, Citation2001).

The Chinese archery team established a reading corner and launched a reading club at the suggestion of psychology practitioners, some heart-stirring verses from traditional Chinese poetry were recited and shared by some participants. A young participant F in his prime read aloud: “The child is determined to leave the hometown, and will not pay back if he fails to achieve something.” A young but promising participant B recited: “I will mount a long wind someday and break the heavy waves, and set my cloudy sail straight and bridge the deep, deep sea” to encourage ourselves to believe “a stone that is fit for a wall is not left on the highway”. A veteran athlete P who had already risen to fame but suffered from uncertainties on and off the archery field recited: “An old steed in the stable still aspires to gallop a thousand li (one li is about 0.5 km), and a noble-hearted man retains his high aspirations even in old age”, implying that veterans can still embrace lofty goals and compete on the same arena as the youngsters.

Data analysis

Nonoverlap of All Pairs (NAP) (Parker & Vannest, Citation2009) is interpreted as the percentage of all pairwise comparisons across Phases A and B, which show improvement across phases or, more simply, “the percentage of data which improves across phases.” NAP equals or outperforms the other overlap indices on most criteria (Parker & Vannest, Citation2009). Thus NAP was adopted in our study considering the type of data that we had. Conceptually, NAP is a “complete” nonoverlap index as it individually compares all nA × nB data points. It is calculated as the number of positive (Pos) pairs plus half of the ties (0.5 × Ties), divided by all pairs (Pairs): NAP = ([Pos + 0.5 × Ties] / Pairs), The NAP original value can be converted to a NAP standard value ranging from 0% to 100% by the formula: Result0–100% = (Result50%−100% / 0.5) – 1. The meaning represented by the NAP standard value is: 0.31 and below indicates weak or no effect; between 0.32 and 0.84 is a medium effect and between 0.85 and 1 is a strong effect (Parker et al., Citation2011).

The dependent variables score was submitted to repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with the within-subject factors phase (baseline phase, intervention phases, withdrawal phase), Scores are measured once a month. Score baseline phase = 1/2 * (ScoreDEC + ScoreJan), Score intervention phases = 1/5 * (ScoreFeb + ScoreMar + ScoreApr + ScoreMay + ScoreJun), Score baseline phase = 1/2 * (ScoreJul + ScoreAug).

For the qualitative phase of this study, six steps of a reflexive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019) were used. First, we familiarised ourselves with the data (e.g., re-reading, searching for meaning or patterns). Second, we produced initial codes from the data that appeared interesting to be analyzed (e.g., a basic segment that can be assessed in a meaningful way regarding activism orientation and our research aims). All codes were identified with a semantic approach (e.g., within explicit or surface meanings). Third, we refocused the initial code at the level of themes by sorting the different codes into potential themes, and then we collected candidate main themes and sub-themes. Fourth, we reviewed and refined our themes to form a coherent pattern, and moved, discarded, and created a theme within internal homogeneity and external heterogeneity. Fifth, we defined the themes that give the reader a sense of meaning and implication from themes. Finally, we wrote up our thematic analysis with, what we hoped was a coherent, logical, and interesting account of the story.

Results

Quantitative results

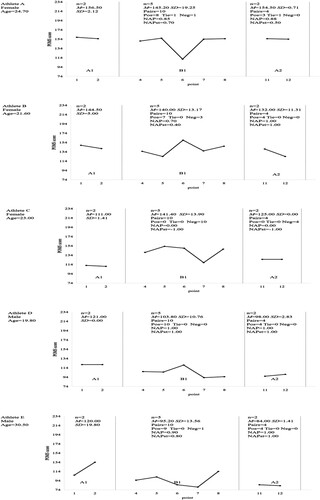

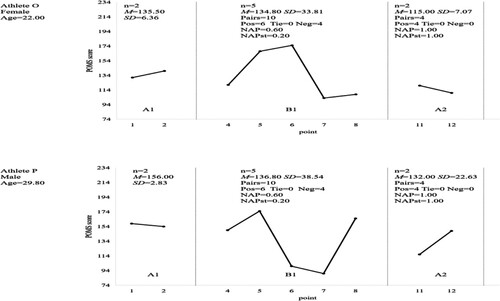

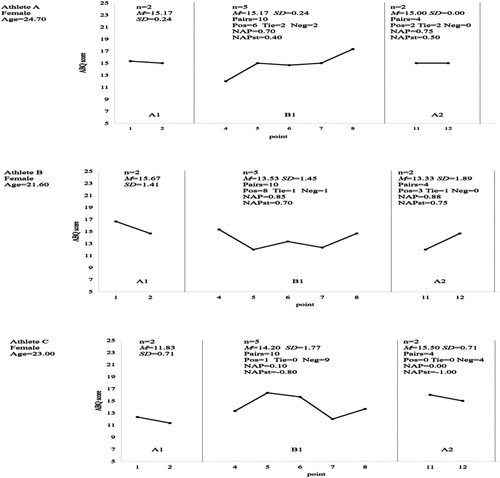

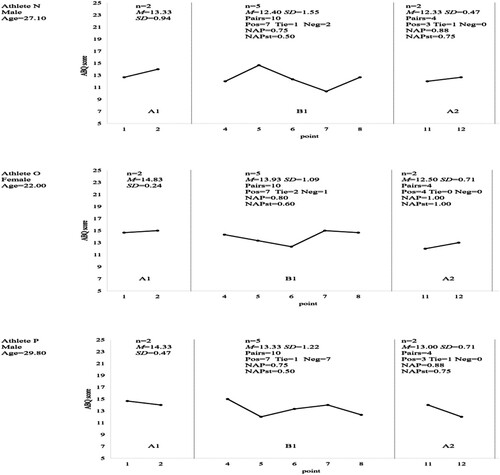

Profile of mood states

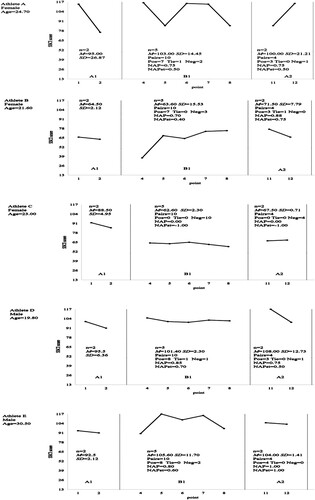

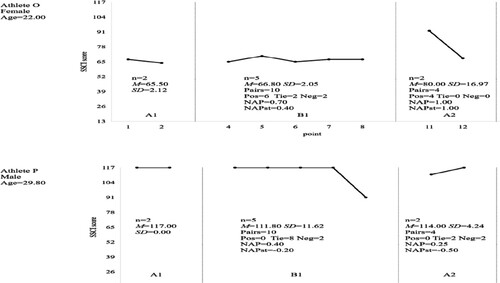

The data from the 16 participants were collected for analysis, see . For all 16 of the participants, the stand scores of the NAP for some participants in the intervention and withdrawal phases were lower than those of the baseline phase. These results indicated that both intervention and withdrawal phases were partly effective in decreasing total mood disturbance. Moreover, during the intervention phase, the NAPst of participants D and F was 1.00 implying that the intervention had a strong effect, the NAPst scores of ten participants were very high (0.80, 0.70, 0.70, 0.60, 0.50, 0.50, 0.40, 0.40, 0.40, 0.40), indicating a medium-strength effect. Then, during the withdrawal phase, the NAPst of participants D, E, F, H, J, L, O, and P was 1.00, implying that the intervention continuity had a strong effect, the NAPst2 scores of six participants were very high (0.80, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.40), indicating a medium-strength effect. These results diverged among the participants to some degree. Specifically, the training had strong effects on 14 of the participants, and the training's effect on participants C and N was of no effect. Moreover, there seemed to be a small and medium-strength effect in the intervention and a strong effect in the withdrawal phase for participants B, E, H, J, L, O, and P.

Figure 1. Changing trend of total mood disturbance for all athletes measured by Profile of Mood States (POMS).

The resultant of ANOVAs revealed a significant main effect of phase (F(1, 15) = 3.62, p = 0.039, η2 = 0.19). The simple contrasts revealed that the withdrawal phase (115.44 ± 23.22) decreased significantly more than the baseline phase (123.94 ± 21.74, p = 0.029, 95%CI [0.98, 16.02]) but the intervention phases (118.40 ± 21.74) did not.

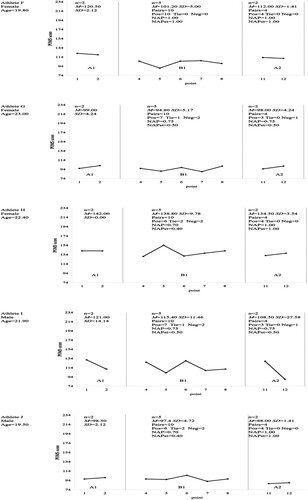

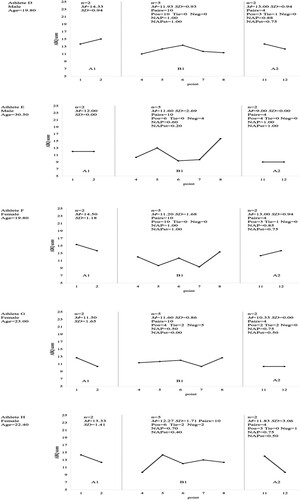

Athletes burnout

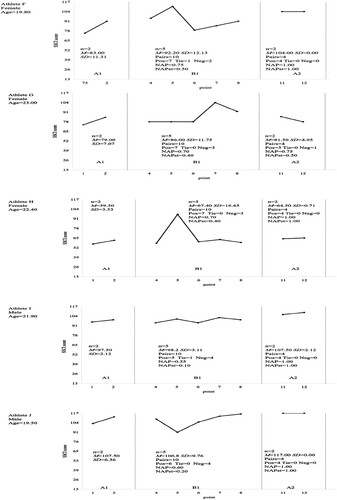

Through visual inspection, the participants’ changing levels of athletes’ burnout scores and experiential acceptance were observable in . For the intervention phase, the NAPst of participants D and F was 1.00 implying that the intervention had a strong effect, the NAPst scores of 9 participants were very high (0.70, 0.70, 0.60, 0.60, 0.60, 0.50, 0.50, 0.40, 0.40), indicating a medium-strength effect. Then, during the withdrawal phase, the NAPst2 of participants E, I, L, and O was 1.00 implying that the intervention continuity had a strong effect, the NAP scores of 10 participants were very high (0.75, 0.75, 0.75, 0.75, 0.75, 0.75,0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50), indicating a medium-strength effect. These results diverged among the participants to some degree. Specifically, the training had strong effects on 15 of the participants, and the programme's effect on participant C was no effect. Moreover, there seemed to be a small and medium-strength effect in the intervention and a strong effect in the withdrawal phase for participants E, I, L, and O. There seemed to be no effect in the intervention and a medium effect in the withdrawal phase for participant G.

Figure 2. Changing trend of athletes’ burnout score for all of the athlete's measured by Athletes Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ).

The resultant of ANOVAs revealed a significant main effect of phase (F (1, 15) = 6.80, p = 0.004, η2 = 0.31). The simple contrasts revealed that the intervention phases (12.22 ± 1.84) and withdrawal phase (12.02 ± 1.84) decreased significantly more than the baseline phase (13.13 ± 2.01, p = 0.009, 95%CI [0.26, 1.56]; p = 0.009, 95%CI [0.31, 1.20]) .

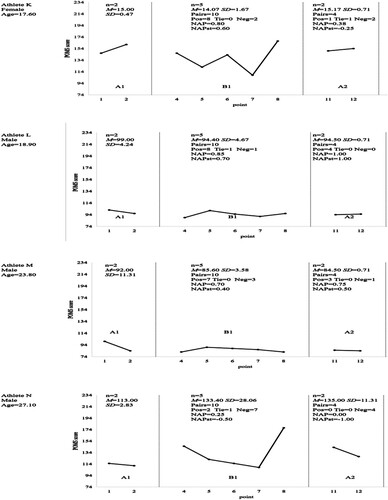

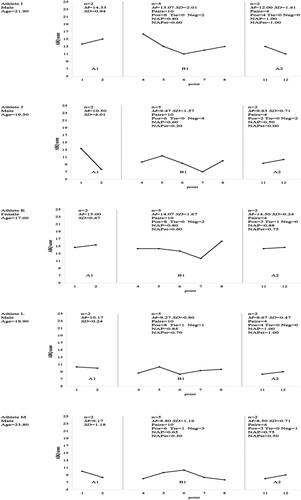

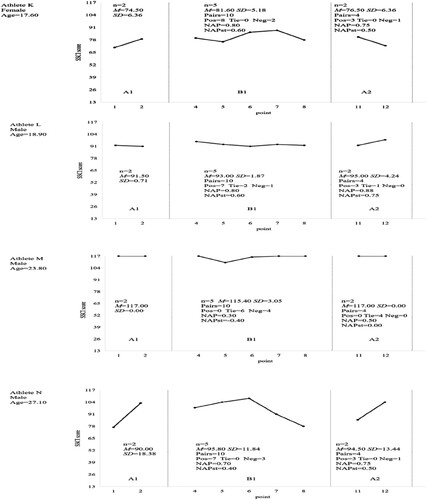

Figure 3. Changing trend of total confidence score for all of the athletes measured by Sports State Confidence Questionnaire(SSCI).

State sport-confidence

Visual analysis showed clear changes in sports state confidence. For participants, the mean SSCI scores were improved after both the intervention and withdrawal phases, compared to the scores from the baseline phase. For the intervention phase, the NAPst scores of 11 participants were very high (0.70, 0.60, 0.60, 0.60, 0.50, 0.50, 0.40, 0.40, 0.40, 0.40, 0.40), indicating a medium-strength effect. Then, during the withdrawal phase, the NAPst of participants E, F, H, I, J, and O was 1.00, implying that the intervention continuity had a strong effect. The NAPst2 scores of 7 participants were very high (0.75, 0.75, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50, 0.50), indicating a medium-strength effect. These results diverged among the participants to some degree. Specifically, there seemed to be a small effect in the intervention and a strong effect in the withdrawal phase for participants I and J.

The resultant of ANOVAs revealed a significant main effect of phase (F(1, 15) = 3.39, p = 0.047, η2 = 0.18). The simple contrasts revealed that the withdrawal phase (93.61 ± 17.91) improved significantly more than the baseline phase (88.6 3 ± 17.22, p = 0.037, 95%CI [0.37, 10.20]) but the intervention phases (90.70 ± 17.59) did not.

Participants’ personal evaluation & coaches’ evaluation

The 16 participants gave an average score of 3.81 ± 1.11 for the overall psychological training arrangement, such as general arrangement, specific content, and regular evaluation of the training effectiveness. The average score of the technique-oriented basic psychological skills training was 3.30 ± 1.11. The average score for knowledge-oriented sport psychology knowledge education was 3.19 ± 1.28. The average score for vision-oriented cultural literacy formation was 3.16 ± 1.28. The average score for the coaches’ acceptance of the overall psychological training arrangement, which included the general arrangement, specific regular, evaluation, etc., was 4.44 ± 0.54. The average score in terms of the technique-oriented basic psychological skills training was 3.76 ± 1.19; the average score for knowledge-oriented sports psychology knowledge education was 4.13 ± 1.21 and that for vision-oriented cultural literacy formation was 4.47 ± 1.53.

Qualitative results

All the participants interviewed (n = 16) told stories of what they’ve learned after the class (e.g., progress; development). Our thematic analysis revealed one key theme called “gains”, and that explains the effectiveness of applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training. This theme incorporates three sub-themes: “technique” “knowledge” and “vision”.

Technique

Basic psychological skill training is essential in maintaining a stable and positive mood. After the outbreak of Covid-19, PST was added to Chinese archery team training. In each psychological training session, the psychologist shared some practical skills (e.g., image training, relaxation, goal setting, and so on). The technique was almost unanimously mentioned as a motivator by the athletes interviewed. They believed that technique-oriented basic psychological skills training helps play games with a positive attitude. As the following quotes suggest:

For our sport, a relaxed and calm mentality is conducive to attaining a relatively higher level in the competition and eliminating fatigue. With Physiological Coherence System being applied to relaxation training, I can understand my physiological conditions through auditory and visual feedback information, monitor my reactions, and thus consciously regulate my physiological functions (Participant P).

Knowledge

Sports psychology knowledge is of great value for improving sporting performance and understanding the methodology and principles of psychological training, thus it helps athletes get out of their current dilemma. The majority of participants reported that they have followed many lectures and received a lot of WeChat messages related to psychology posted by the psychologist. Sometimes when encountering suffering, they said they could get a sense of control and know what to do next from this theoretical knowledge of sports psychology. As the athletes said:

The closed-circuit management in the pandemic age and the endless waiting for whether the Olympic Games will be postponed made me anxious. Fortunately, the psychology coach organized a lot of psychological lectures and posted some articles for us on the WeChat official account, which made my daily life much more colorful and allowed me to learn a lot of basic sport psychology knowledge and soothed my irritability (Participant G).

Before the Tokyo Olympics simulation, I felt too stressed and worried that it would hinder my performance during the games, especially at night I tossed and turned and couldn't fall asleep. At this moment, I suddenly recalled the Achievement Motivation theory I learned in the lecture. I thought about whether the feeling of stress was within my control. The pressure itself was not terrible. The important thing was how to recognize the pressure and how to cope with it. Thinking about it, I gradually felt calm and fell asleep unknowingly. The next day I won the women's championship in the Tokyo Olympics simulation competition (Participant F).

Vision

To expand vision is one of the main characteristics of applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training. Almost all participants mentioned that the content of this psychological training was very different from that of previous ones. The content of this psychological training was detached from the real competition situations, but knowledge athletes learned from class such as philosophy, history, literature, et al can be transferred to competitions. They believe that improving their spiritual realm and laying a good psychological foundation is not only good for optimising their sporting performance but also good for their long-term self-development. As the athletes mentioned:

The psychologist has set up a reading corner for us, we were given more time to read, and on many occasions the psychologist let us share our recent reading experience, I feel that I have read a lot of books in these short five months. I got to know many things outside of training and competition. The psychologist stayed on the team for a long time, eating, living, and training with us so understood us very well. Many comments were very inspiring to me. For example, before the game, the psychologist said to me: “One can be austere if he has no selfish desires. One can be successful if he has the courage.” (Participant F).

When judging from the life-long plan, the current problems seem to be nothing. Sportsman should integrate their personal plan into the big strategy of the motherland and the people, and transform patriotism and national aspirations into concrete actions of hard and scientific training, raising the national flag, and playing the national anthem at the Olympics (Participant L).

Discussion

The quantitative data revealed that applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training had strong effects in the intervention phases given the results of decreased total mood disturbance and burnout, and improved confidence. These sets of findings have a stronger effect size than the small effect size (ES = 0.469) observed in the psychological training meta-analytical reviews regarding archery (Kim et al., Citation2021). with both skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training, lots of assignments should be completed via cooperation, which may have improved the relations among athletes. Sports confidence is significantly related to social support and coach-athlete relationship (Gencer & Öztürk, Citation2018; Hwang et al., Citation2017). Negative emotions, stressful events, and perceived risks caused by the COVID-19 crisis may be the main unfavourable factors for mental health, while social rhythm and family cohesion may be important protective factors (Saltzman et al., Citation2020). Additional studies have found that social support and psychological training can help promote sport confidence (Hung et al., Citation2008; Magyar & Duda, Citation2000; Sordoni et al., Citation2000).

This is highly consistent with the qualitative data, applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training is helpful. Qualitative data explains the deeper reasons for the effectiveness of intervention training from the perspective of technique, knowledge, and vision. The intervention of the current study may be adaptive to the distinctive Chinese context. Under the Chinese Whole Nation System, athletes shall follow a strict and detailed training plan, with training for 6 days a week and rest every Sunday, Cultural education is just like fast food (Si et al., Citation2011). Chinese athletes may lack connections with the outside world and other fields of society. Applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training provided them with a new horizon. For example, athletes could read their favourite books in their spare time and share with others what they had read from books in a reading club. Every athlete has his/her philosophy of life, his/her philosophy of doing things, and his/her code of conduct. We need to guide athletes in the right direction so that their ego is constantly improved, developed, and sublimated. Athletes should not only listen to lectures “passively”, but also be given opportunities to actively express their views (Zhang et al., Citation2013).

Additionally, the withdrawal phase had stronger impacts than the intervention phase in terms of decreased overall mood disturbance, burnout, and better confidence. ANOVA analysis showed that, compared to the baseline phase, the withdrawal phase significantly reduced mood disturbance and increased confidence, whereas the intervention phases did not. It showed how psychological training that is skill-oriented and spirit-oriented has a continuous impact. The qualitative data revealed that cultural literacy provided athletes with a new horizon and made them consider archery competitions with another vision. According to the theoretical basis of Maslow's Humanistic Theory which emphasises human dignity, value, creativity, and self-realisation, Zhang and Zhang (Citation2011) who invented Psychological Development System for Chinese Athletes, believe that in the psychological training process, sports psychologists should not only pay attention to solving the current problems of athletes but also focus on the overall and life-long development of athletes and that athletes should be deemed as persons with a holistic development process, not as a tool for profit. Although the training period was only five months, about half of the participants showed a large effect of the intervention. According to Kim et al Citation2021, in general, the effect of psychological skills training can be expected from at least 12 weeks, but it is difficult to say that the person is skilled in psychological skills just because this period has elapsed. Thus, it can be seen that psychological skills are not acquired through short-term experience but through long-term training and practice. Therefore, it is highly recommended that future research designs could incorporate a longer period of test trial phase and long-term training.

Psychological training is a process of psychological formation based on local culture and the gradual development of athletes’ mental abilities. Based on the training in psychological skills, participants studied psychological knowledge, with the ultimate goal to widen their vision and enhance their spiritual realm. Therefore, it is both skill-oriented and spirit-oriented. This kind of understanding is the consensus reached by many Chinese sports psychologists in the process of providing long-term psychological services (Zhang et al., Citation2021; Zhang & Li, Citation2019; Zhang & Zhang, Citation2011). Many Western sport psychology services refer to “whole-person cultivation”, which is similar to what we called applying skill-oriented and vision-oriented education. Gordin and Henschen (Citation1989) mentioned that the real standard of success in sports psychological services is the development and maturity of athletes, and athletes’ ability to apply psychological skills beyond sport. The basic starting point for psychological training in Denmark is “whole-person development”, Norway starts from the concept of “sport for all”, and the United Kingdom provides psychological services based on the concept of “persons first, athletes second” (Li & Zhang, Citation2020). The application of multicultural perspectives in psychology practice is becoming increasingly extensive (Blodgett et al., Citation2017; Fisher & Anders, Citation2020). Cultural competence has become one of the necessary skills for sports psychologists (Quartiroli et al., Citation2020). Under a socio-cultural context, applying a skill-oriented and spirit-oriented Psychological Development System for Chinese Athletes was effective, providing aspects that might be applicable in other sports systems.

These results diverged among the participants to some degree. For example, applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training didn't take effect for participant C, instead, it went another way around (POMS: NAPst1 = −1.00, NAPst2 = −1.00; ABQ: NAPst1 = −0.80, NAPst2 = −1.00; SSCI: NAPst1 = −1.00, NAPst2 = −1.00). Therefore, the current study is not omnipotent and has limitations. Firstly, the findings of the current study may not generalise to other athletes among various events. Furthermore, as single-case studies do not employ a control group, the changes in the results were probably due to other reasons, such as the therapeutic relationship (Schwanhausser, Citation2009). In addition, following the lack of suitable questionnaires to measure the spiritual realm in elite athletes, it is reasonable for researchers to develop a more accurate instrument for this population. In the future, more robust methods (qualitative study, training scores, competition scores) could be applied to evaluate the effectiveness of applying skill-oriented and spirit-oriented psychological training.

Conclusion

The five-month PST for the Chinese Archery Team was guided by the Psychological Development System for Chinese Athletes, highlighting the psychological training idea of “the combination of skill orientation and spirit orientation”. The psychological training adopted basic psychological skills training as the foundation, and psychological knowledge learning as advancement, with the ultimate goal to widen participants’ vision and enhance their spiritual realm. This methodology yielded good results in the practice of psychological services. Sport psychology practitioners ought to consider cultural background when offering psychological training. This study can provide sports psychologists with new psychological interventions and practical ideas for helping athletes cope with the short-term and long-term impact of the pandemic and improve themselves. Future studies should consider expanding the scale of implementation, nationwide, at an increasing number of sport training centres to test its feasibility and effectiveness in different contexts.

Data deposition

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Blodgett, A. T., Ge, Y., Schinke, R. J., & McGannon, K. R. (2017). Intersecting identities of elite female boxers: Stories of cultural difference and marginalization in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 32, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.06.006

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brewer, B. W., & Shillinglaw, R. (1992). Evaluation of a psychological skills training workshop for male intercollegiate lacrosse players. The Sport Psychologist, 6(2), 139–147. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.6.2.139

- Brown, C. J., Webb, T. L., Robinson, M. A., & Cotgreave, R. (2018). Athletes’ experiences of social support during their transition out of elite sport: An interpretive phenomenological analysis. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 36, 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.01.003

- Bu, D., Liuc, J. D., Zhanga, C. Q., Sid, G., & Chunga, P. K. (2019). Mindfulness training improves relaxation and attention in elite shooting athletes. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 50(1), 4–25. https://doi.org/10.7352/IJSP2019.50.004

- Cranmer, G. A., & Sollitto, M. (2015). Sport support: Received social support as a predictor of athlete satisfaction. Communication Research Reports, 32(3), 253–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2015.1052900

- Fisher, L. A., & Anders, A. D. (2020). Engaging with cultural sport psychology to explore systemic sexual exploitation in USA gymnastics: A call to commitments. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 32(2), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1564944

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

- Fronso, S. D., Costa, S., Montesano, C., Di Gruttola, F., Ciofi, E. G., Morgilli, L., … Bertollo, M. (2022). The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on perceived stress and psychobiosocial states in Italian athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2020.1802612

- Gencer, E., & Öztürk, A. (2018). The relationship between the sport-confidence and the coach-athlete relationship in student-athletes. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 6(10), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v6i10.3388

- Gerber, M., Gustafsson, H., Seelig, H., Kellmann, M., Ludyga, S., Colledge, F., … Bianchi, R. (2018). Usefulness of the athlete burnout questionnaire (ABQ) as a screening tool for the detection of clinically relevant burnout symptoms among young elite athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 39, 104–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.08.005

- Gordin, R. D., & Henschen, K. P. (1989). Preparing the USA women’s artistic gymnastics team for the 1988 olympics: A multimodel approach. The Sport Psychologist, 3(4), 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.3.4.366

- Hagiwara, G., Iwatsuki, T., Isogai, H., Van Raalte, J. L., & Brewer, B. W. (2017). Relationships among sports helplessness, depression, and social support in American college student-athletes. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 17(2), 753–757. https://doi.org/10.7752/jpes.2017.02114

- Hung, T. M., Lin, T. C., Lee, C. L., & Chen, L. C. (2008). Provision of sport psychology services to Taiwan archery team for the 2004 Athens Olympic games. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 6(3), 308–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671875

- Hwang, S., Machida, M., & Choi, Y. (2017). The effect of peer interaction on sport confidence and achievement goal orientation in youth sport. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 45(6), 1007–1018. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.6149

- Kim, E. J., Kang, H. W., & Park, S. M. (2021). The Effects of Psychological Skills Training for Archery Players in Korea: Research Synthesis Using Meta-Analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052272

- Kim, E. J., Kang, H. W., & Park, S. M. (2021). The effects of psychological skills training for archery players in Korea: Research synthesis using meta-analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2272. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052272

- Knight, C. J., Harwood, C. G., & Sellars, P. A. (2018). Supporting adolescent athletes’ dual careers: The role of an athlete's social support network. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 38, 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.06.007

- Lazarus, R. S. (2000). How emotions influence performance in competitive sports. The Sport Psychologist, 14(3), 229–252. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.14.3.229

- Li, D. Y., & Zhang, L. W. (2020). From serious injury to returning to winter olympics: The psychological rehabilitation process of a high-risk sport athlete. China Sport Science, 4(3), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.16469/j.css.202003003

- Li, Q. L., Zhang, L., B, L. I., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Research on sleep quality and affecting factors of elite bobsleigh athletes during winter training and preparation period. Sport Science Research, 43((02|2)), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.12064/ssr.20220205

- Lin, L., & Zhang, L. W. (2008). Related indexes of sports psychological fatigue. China Journal of Sports Medicine, 27((02|2)), 231–234. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16038/j.1000-6710.2008.02.012

- Magyar, T. M., & Duda, J. L. (2000). Confidence restoration following athletic injury. The Sport Psychologist, 14(4), 372–390. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.14.4.372

- Martin, J. J., & Gill, D. L. (1991). The relationships among competitive orientation, sport-confidence, self-efficacy, anxiety, and performance. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(2), 149–159. http://hk.humankinetics.com/JSEP/journalAbout.cfm https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.13.2.149

- McCullough, M. E., Kimeldorf, M. B., & Cohen, A. D. (2008). An adaptation for altruism: The social causes, social effects, and social evolution of gratitude. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(4), 281–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00590.x

- Moussavi Esterabadi Kermani, F., & Birjandi, P. (2019). Heart-Brain coherence; heart-rate variability (HRV); Reading anxiety; TestEdge program. Research in Applied Linguistics, 10(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-9880.1000583

- Parker, R. I., & Vannest, K. J. (2009). An improved effect size for single case research: NonOverlap of All pairs (NAP). Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 357–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.10.006

- Parker, R. I., Vannest, K. J., & Davis, J. L. (2011). Effect size in single-case research: A review of nine nonoverlap techniques. Behavior Modification, 35(4), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145445511399147

- Quartiroli, A., Vosloo, J., Fisher, L., & Schinke, R. (2020). Culturally competent sport psychology: A survey of sport psychology professionals’ perception of cultural competence. The Sport Psychologist, 34(3), 242–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/21520704.2020.1833124

- Qui, F., & Zhang, X. Q. (2019). Influences of friendship quality of young athletes on internet addiction: Chain mediating of lonliness and sports psychological fatigue. Journal of Wuhan Institute of Physical Education, 53(7), 94–100. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.15930/j.cnki.wtxb.2019.07.014

- Ridley, S. E. (1992). Effects of an imagery-focused psychological skills training program upon selected aspects of students’ volleyball performance and reported imagery skills (Doctoral dissertation, Temple University).

- Saltzman, L. Y., Hansel, T. C., & Bordnick, P. S. (2020). Loneliness, isolation, and social support factors in post-COVID-19 mental health. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S55–S57. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000703

- Schwanhausser, L. (2009). Application of the mindfulness-acceptance-commitment (MAC) protocol with an adolescent springboard diver. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 3(4), 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.3.4.377

- Scott, C. L., Haycraft, E., & Plateau, C. R. (2021). The influence of social networks within sports teams on athletes’ eating and exercise psychopathology: A longitudinal study. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 52, 101786. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020

- Si. (2006). Pursuing “ideal”or emphasizing “coping”: The New definition of “peak-performance” and transformation of mental training pattern. China Sport Science, 10, 43–48+53. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.16469/j.css.2006.10.006

- Si, G., Duan, Y., Li, H. Y., & Jiang, H. (2011). An exploration into socio-cultural meridians of Chinese athletes’ psychological training. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 5(4), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.5.4.325

- Sordoni, C., Hall, C., & Forwell, L. (2000). The use of imagery by athletes during injury rehabilitation. Journal of Sport Rehabilitation, 9(4), 329–338. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsr.9.4.329

- Taha, Z., Musa, R. M., Abdullah, M. R., Maliki, A. B. H. M., Kosni, N. A., Mat-Rasid, S. M., … Juahir, H. (2018). Supervised pattern recognition of archers’ relative psychological coping skills as a component for a better archery performance. Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences, 10(1S), 467–484. https://doi.org/10.4314/jfas.v10i1s.33

- Vealey, R. S. (2007). Mental skills training in sport. In G. Tenenbaum, & R. C. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (pp. 287–309). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Vidic, Z. (2021). Sharpening the mental edge in Ice-hockey: Impact of a season-long psychological skills training and mindfulness intervention on athletic coping skills, resilience, stress and mindfulness. Journal of Sport Behavior, 44(4), 468. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2021.1891120

- Yang, S., & Zhang, Z. Q. (2014). Effect of mindfulness-based cognitive intervention on the stress-related psychological parameters of elite athletes. Chinese Journal of Sport Medicine, 214–223. (In Chinese).

- Zamora, L. (2015). The Effects of Exemplar Priming on Athletic Performance Success (Doctoral dissertation, California State University, Northridge). https://scholarworks.csun.edu/bitstream/handle/10211.3/145099/Zamora-Luis-thesis-2015.pdf?sequence = 1

- Zhang, K. (2013). Athlete’s mental training: Contribution of practice the methods of Chinese culture. China Sport Science, 3, 524–531. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.2013.03.005

- Zhang, K., & Zhang, L. W. (2011). Doctrine and method: What Chinese culture can contribute to athletes’ psychological training and consultation. Journal of Tianjin University of Sport, 26(3), 196–199. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.15930/j.cnki.wtxb.2012.08.018

- Zhang, L., Ge, Y., & Li, D. (2021). The features and mission of sport psychology in China. Asian Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajsep.2021.03.008

- Zhang, L. W., & Bi, X. T. (2009). Mental training of China rhythmic gymnastics team for Beijing Olympic games. Journal of Tianjin University of Sport, 24(1), 6–9. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.2009.01.004

- Zhang, L. W., & Li, M. L. (2019). In pursuit of excellence: Skill oriented and spirit oriented mental training of an Olympic athlete. Journal of Capital Institute of Physical Education, 31(2), 110–114. (in Chinese). https://doi.org/10.14036/j.cnki.cn11-4513.2019.02.004

- Zhang, L. W., & Mao, Z. X. (2007). Sport psychology. Higher Education Press. 269–270, 285–286. (in Chinese).

- Zhang, L. W., Wang, J., & Zhang, K. (2013). Mental training for the freestyle skiing aerials team in preparing for the Vancouver winter Olympic games. Sport Science Research, 1, 58–66. (in Chinese). CNKI:SUN:TYKA.0.2013-01-018

- Zhu, B. L. (1995). Brief introduction of POMS scale and its model for China. Journal of Tianjin University of Sport, 10(1), 35–37. https://doi.org/10.13297/j.cnki.issn1005-0000.1995.01.007