ABSTRACT

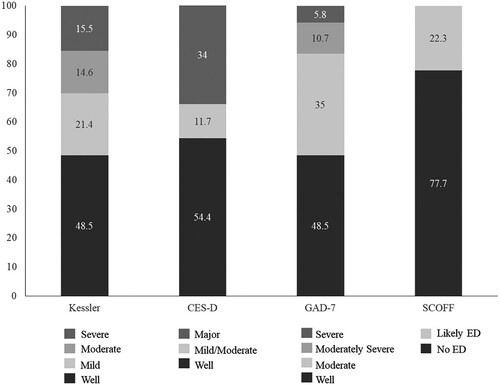

Despite the growth in women’s soccer globally, there remains sparse research in this population, especially outside of elite levels and in relation to mental health. Limited research has examined the lived experiences of mental health within sub-elite women’s sport. Within this mixed-methods study, we aimed to provide insight into both the prevalence of mental ill-health and the complexities of how mental health is perceived, interpreted, and experienced in a unique and under-researched population. Footballers competing in tier three of the UK women’s leagues completed a survey to assess mental ill-health symptoms. Follow-up semi-structured interviews were completed with six players. A total of 103 players completed the questionnaire: 49.5% (n = 51) displayed distress symptoms (Kessler-10); 44.7% (n = 46) displayed depression symptoms (CES-D); 20.4% (n = 21) displayed anxiety symptoms (GAD-7); and 22.3% (n = 23) displayed eating disorder symptoms (SCOFF). Using reflexive thematic analysis three themes were developed: “Navigating Tier 3 women’s football: a balancing act”, “Football: is it good for my mental health?” and “Speaking out about my mental health: the confusion and the cost”. Overall, prevalence of symptoms associated with mental ill-health ranged from 20.4% to 49.5% among semi-elite female footballers, which are shaped by individual experiences. The female footballers reported athlete-specific risk factors for mental ill-health at the individual level as well as the sporting environmental level. The findings and implications for sub-elite women’s soccer are discussed.

Research on mental health in elite sport has increased significantly in the past 10 years. It is now recognised that athletes are as susceptible to mental ill-health as the general population (Castaldelli-Maia et al., Citation2019; Gouttebarge et al., Citation2019; Vella et al., Citation2021; Walton et al., Citation2021). Rather, the additional pressures and demands associated with being an athlete increases the risk of mental ill-health within this population (Foskett & Longstaff, Citation2018; Küttel & Larsen, Citation2020; Rice et al., Citation2016).

Mental health in elite sport has been defined as:

a dynamic state of well-being in which athletes can realize their potential, see a purpose and meaning in sport and life, experience trusting personal relationships, cope with common life stressors and the specific stressors in elite sport, and are able to act autonomously according to their values. (Küttel & Larsen, Citation2020, p. 253)

Inconsistent definitions of “elite athletes” within mental health literature have led to samples that include athletes across various competition levels, limiting our contextualised understanding of individual experiences of mental health (Perry et al., Citation2021). Differences in the risk of a mental health disorder between competitive levels have been reported (Prather et al., Citation2016), but no further explanatory insights have been provided (Perry et al., Citation2021). “Semi-elite” (i.e., “those whose highest level of participation is below the top standard possible in their sport”; Swann et al., Citation2015, p. 11) athletes are often required to seek employment alongside their participation in sport and are subject to many of the stressors typical of elite athletes with limited resources to balance these demands (Gulliver, Citation2017; Henderson et al., Citation2023).

Researching semi-elite populations and mental health is in its infancy. Only one study has focused on semi-elite populations, with Henderson et al. (Citation2023) finding that 10.1% and 22.8% of semi-elite Australian Rules soccer players reported general anxiety and depressive symptoms. This is comparable to Australian elite athletes who reported 7.1% and 27.2% general anxiety and depressive symptoms (Gulliver et al., Citation2015). Other studies have compared competition levels in elite settings (Junge & Prinz, Citation2019; Perry et al., Citation2022). In a mixed sample of elite female footballers, “part-time” student-athletes have been reported to have higher disordered eating symptoms, attributed to balancing the demands of studying and competing (Perry et al., Citation2022). Junge and Prinz (Citation2019), in a mixed sample of female footballers, found significantly more second-league players reported symptoms of depression than first-league players. These quantitative findings prompt an exploration of the complex role of semi-elite sports environments and their influence of mental health.

Research in this context is timely and important, given the burgeoning professional status of women’s soccer around the world and the precarious nature of soccer as work for women (Culvin, Citation2021). Despite the growing involvement of women in sports (Henderson et al., Citation2023), the lack of adequate representation of women in sports medicine research presents an issue. This problem is further emphasised by the increasing professionalisation of women's sport, particularly the heightened professionalism observed in women's soccer in the United Kingdom (Culvin, Citation2021). Perry et al. (Citation2021) responded to a call for research to explore mental health and elite female athletes, highlighting that most studies on female athletes have explored American collegiate athletes’ experiences of mental health (e.g., eating disorders and body image) in individual sports such as gymnastics and athletics. As such, a detailed understanding of the mental health-related experiences of female athletes competing in team sports and other sociocultural contexts is missing from the literature. Exploring a population of “semi-elite” female athletes can further our understanding of how mental health is influenced by lifestyles that involve concurring and sometimes conflicting demands.

Due to the lack of established professional status in tier three of women’s soccer in the UK, this sub-population may be overlooked despite some players performing at the international level and being faced with the competitive values that have increased since the growth of the women’s game (Culvin, Citation2021). Although The English Football Association (FA), has introduced the Women’s National League Strategy 2022-25, and minimum standards tier three of women’s soccer in the UK is the highest league without professional licensing requirements, nor well-established criteria for the organisational running of clubs. The additional stressors associated with being a competitive but non-professional athlete (e.g., the need to earn a living wage, limited access to specialist facilities and support) might further contribute to the onset of mental ill-health as players attempt to balance multiple roles. To date, there is no holistic understanding of the mental health experiences of “semi-elite” female footballers within England. Therefore, the present study aimed to provide insight into both the prevalence of mental ill-health and the complexities of how mental health is perceived, interpreted, and experienced in a unique and under-researched population. This understanding is necessary for the development of culturally informed and effective support mechanisms. With the focus on mental ill-health symptomology, the authors do not intend to report diagnosed prevalence.

Materials and methods

Philosophical assumptions and research design

We adopted a pragmatic approach throughout the research process. Pragmatism places primacy on how different methods produce different understandings of phenomena as opposed to emphasising how methods probe ontological and epistemological questions (Biddle & Schafft, Citation2015). Through a pragmatic lens, we employed methods directed by the needs of the research question (Creswell, Citation2014) and characterised by epistemological pluralism (Ghiara, Citation2020). We utilised a sequential explanatory mixed-method design (see ; Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2009), allowing qualitative findings (i.e., experiences) to complement initial quantitative (i.e., rates) findings. Obtaining quantitative data enabled insight into the extent to which female footballers experienced mental health symptoms across tier-three women’s soccer in the UK and identified a sample for the qualitative phase, which enriched our findings to gain a deeper understanding of the mental health experiences of semi-elite female footballers.

Participants and procedure

Following institutional ethical approval, data were collected during the middle of the 2019–2020 season, prior to COVID-19. Female footballers from 24 “tier three” women’s soccer clubs in England were invited to participate (see Supplementary Material 3 for detailed participant characteristics). There was a total of 656 registered players across both leagues, and it was estimated 384 players were eligible for participation based on playing status and average squad number. Participation was voluntary and participants in both phases provided written informed consent. The survey sample consisted of 103 sub-elite female footballers playing for 13 teams in the English Football Association Women’s National Premier Division North and South. Participants completed either an online (Google Forms: 86%) or written survey (14%) during the period of 11/02/2020 and 11/03/2020.

On completion of the survey, participants were asked if they would be willing to provide contact details for involvement in the interviews. 60 agreed to be contacted (58.3%) and 51 left contact details (49.5%). We were interested in interviewing individuals displaying higher levels of mental ill-health symptoms across multiple domains of mental health (e.g., participants who displayed at least mild symptoms in more than two of the survey measures). All participants were aware of the sampling criteria, and we emphasised that all measurement tools were non-diagnostic. In total, 24 participants matching the sampling criteria were invited to participate; 9 responded to initial interview requests however only 6 maintained contact and participated in the interviews. highlights participant characteristics for those interviewed.

Table 1. Demographic profiles of participants interviewed.

Phase one: quantitative survey

The survey consisted of demographic information (e.g., age, club, years of experience, selection status, and playing position) and several validated questionnaires assessing self-reported symptom prevalence. With all the measures, higher scores indicated higher symptom levels. See Supplementary Material 1 for additional information, regarding scoring and reliability of measures.

Distress. We assessed distress symptomatology using the Kessler-10 (Kessler et al., Citation2003). The total distress score relates to four categories: Likely to be well (score of <20); Likely to have a mild mental disorder (score between 20 and 24); Likely to have moderate mental disorder (score between 25 and 29); and Likely to have severe mental disorder (score > 30).

Depression. Commonly used with elite athletes (Tahtinen et al., Citation2021), symptoms of depression were measured using the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Citation1977). The most commonly used cut-off score of ≥16 was used for the cut-off for depressive symptoms (Tahtinen et al., Citation2021).

Anxiety. The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer et al., Citation2006) assessed prevalence of anxiety symptoms. Given the variation of cut-off scores for GAD-7 used within athletic populations (Gulliver et al., Citation2015; Kilic et al., Citation2021; Perry et al., Citation2022), a cut-off score of ≥10 was used (Spitzer et al., Citation2006).

Eating disorder. The SCOFF (Morgan et al., Citation1999) measured the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. Consistent with research in an athletic population (Gulliver et al., Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2015), responding yes to more than two was used as a cut-off score for disordered eating symptoms.

Phase two: qualitative interviews

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions. This approach was sufficiently broad enough for participants to discuss their interpretations and experiences of mental ill-health, whilst following an interview guide-maintained focus of the research (Smith & Caddick, Citation2012). Supplementary Material 2 features the full interview guide. All interviews were conducted by the first author in-person or online. The interviews began with an overview of the aims of the study, a reminder of the survey procedure and purpose, ethical considerations, confidentiality and the right to withdraw. Further support and resources regarding mental health were outlined to the participants. It was also emphasised that the survey findings were not for diagnostic purposes. Interviews were recorded with consent, transcribed, deidentified, and stored electronically. The duration of interviews ranged from 37 to 55 minutes, which produced 69 pages of data.

Data analysis

All data were processed using Excel and IBM SPSS statistics (v. 26). Descriptive analyses using mean and standard deviation were performed for participant characteristics and average scores of each questionnaire. Prevalence of mental ill-health symptoms for each screening tool were established by calculating the number of people who had met the cut-off scores for each measure and dividing this by the total number of people in the sample. Reflexive thematic analysis (TA) was conducted on the interview data. Using an inductive approach and following the “flexible and iterative nature of TA” (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019, p. 953), although not a homogenous process, analysis involved going back and forth through the phases identified by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019). Phase 1 – Familiarisation: by conducting every aspect of data generation, from developing the interview questions conducting and transcribing the interviews, the first author was fully immersed in the data. Transcriptions along with survey results of the interviewees were read and re-read with familiarisation notes as well as whole data set summaries. Phase 2 – Initial code generation: the first author then conducted line-by-line coding by highlighting and annotating the transcripts. At first semantic coding was predominant, sticking closely to what participants said and after re-visiting the codes and data set, latent coding was used to uncover underlying meanings. Phase 3 – Generating themes: codes were then coloured coded and re-grouped and written up into a “directory” where initial grouping took place. Codes were grouped together based on shared meaning, these initial candidate themes were then compared against the full datasets and familiarisation notes to corroborate whether the codes and themes truly reflected the participants experiences underlying meanings. This process intended to have both descriptive and interpretive elements. Descriptive elements represented what the participants said, and the interpretive aspects stemmed from the first author’s subjectivity by considering underlying meanings, and responses that might be influenced by the sociocultural context such as experiences of dehumanisation (Wood et al., Citation2017). Phase 4 – Reviewing themes: thematic maps were created in order to develop themes and related meanings. The first author discussed themes with a critical friend for the purpose of reflexivity, providing an alternative standpoint and posing questions to challenge the interpretations of the first author. Initially, narratives were constructed as sub-themes under a central organising concept, however it came to light that this required revision to fully capture the complexities and context of mental health experiences of sub-elite female footballers. Phase 5 – Defining themes: the first author engaged in multiple discussions about the potential themes and meaning of codes with a critical friend to check that quotes, coding and themes told accurate stories as shared by the participants within the context of women’s soccer. Through reflexive discussions with the second and third authors and evaluative techniques, this was repeated until agreeance was achieved. Phase 6 – Producing the report: final extracts of the data were agreed upon and discussed in relation to the appropriate fully realised theme. Through writing, applicability of findings was assessed, and the data were compared to the purpose of the study. When writing the first author had the research question and aims in front of them, and continuously reflected on whether the report was providing a credible representation of the participant’s experience of mental ill-health in semi-elite soccer environments. For further detail on coding and theme development, see Supplementary Material 5.

Methodological quality and rigour

We expanded on a range of judgement criteria used by MMR in sport exercise psychology and selected the following criteria: worthy topic, rich rigour, credibility, and significant contribution. We have reported procedures associated with high levels of rigour (see Harrison et al. (Citation2020), for the coding scheme), for each of the research stages. Adherence and reflexivity throughout the six guidelines were used to ensure rigour during qualitative data analysis (Braun et al., Citation2016) along will additional measures. We used critical friends, pilot interviews and self-reflective journal accounts as tools to enhance methodological quality (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). Researcher reflexivity was imperative to the research quality given the first author’s experiences and background in sub-elite women’s soccer. She continuously considered how her position came with potential benefits (e.g., access, acceptance, and trust) and limitations (e.g., self-biases; see Dwyer & Buckle, Citation2009). This subjectivity was considered as a resource throughout the data collection and analysis. When interviewing, she could resonate with the interviewee’s experiences (e.g., pressure to perform, managing conflicting schedules, coach-athlete relationships, team dynamics, etc.) to create a sense of trust and mutual understanding, as well as understanding the contextual setting to ask appropriate probing questions with genuine curiosity, leading to a greater openness from participants to share (Dwyer & Buckle, Citation2009). During analysis, the first author’s personal experiences were an important factor for making sense of the participants’ experiences. Equally, the critical friend and reflective journalling served as important tools to prevent her experiences delimiting interpretation of data. The research team judges the credibility of this work on the contribution that it makes to current mental health in sport literature, applied sport psychology practice and professional training.

Results

Phase one: mental health prevalence

All questionnaires were fully completed and screened for distracted responders, therefore eligible for analysis, Supplementary Material 4 reports descriptive statistics and normality distribution. The prevalence of symptoms among semi-elite female footballers was 49.5% for distress; 44.7% for depression; 20.4% for generalised anxiety and 22.3% for an eating disorder ().

Phase two: experiences of mental ill-health

The following themes and interpretations illustrate stories told by the footballers regarding their experiences with mental health during and outside of their soccer career. The six footballers who were interviewed for this section had similar scores on the mental health questionnaires in that they reported high mental health symptomology in at least two measures. Drawing upon participants’ personal and individual stories, we present main themes below: “Navigating Tier 3 women’s football: a balancing act”; “Football: is it good for my mental health?”; “Speaking out about my mental health: the confusion and the cost”. To protect confidentiality and anonymity, all names are pseudonyms. Additional data extracts can be found in Supplementary Material 6.

Navigating Tier 3 women’s football: a balancing act

As women’s soccer in England experiences rapid changes to the structure, the leagues, and the professional set-up, the footballers themselves are tasked with navigating these changes often without appropriate resources supporting them. The footballers all recognised the increased pressures in tier three women’s soccer across the interviews. For example, Sara said:

before it [tier 3] was a really nice environment with no pressure, just having fun, just playing the game you love but it’s become more competitive, more we have to win, we have to do this, so it’s less enjoyable 100%.

I just want to play football all the time, and so … I’d miss lectures because I just wanted to play football. Then I started not doing well in exams at all, which was really stressful. To the point where I was like, ohh I don’t care. But I did care but I just cared about football more. That was stressful.

I think that even though it’s women’s football, there’s always … men’s football is right up here, and women’s football is lower standard but there is no pressure on women to do well or no pressure on women. However, that’s not the case, in every team regardless of the team you’re in there’s also the pressure whether it is men or women, that adds to the mental stress. (Molly)

Football: is it good for my mental health?

All the footballers discussed stories evidencing the positive and negative role soccer has on their mental health. Many of the footballers discussed a specific incidence where they felt their mental health was substantially challenged due to a combination of factors including personal stressors (e.g., work demands, relationship struggles) and soccer stressors (e.g., injury, deselection from the squad). In describing these experiences, they often discussed feeling stressed and overwhelmed. For example, Emma said, “I don’t know how to describe it, but it was like one thing was happening here and another, and another thing. I didn’t know how to put it all together, and that was just spiralling basically”.

Similarly, to events in everyday life (e.g., family illness, bereavement, and break-ups), soccer presented specific challenges and events, especially when participants did not have control over them. Injury was a specific event that was most widely acknowledged to impact mental health and the level of symptoms changed throughout different stages of injury:

[I felt] anxious because I thought I was going to lose my place, really upset about it. I felt useless. I felt really useless … but then at the same time, I went through phases. At the start I was really upset, and then I sort of got motivated, like “you know what I’m not going to sit here and mope about it, I've got to do something about it”- I was sorting all that. I think my hardest bit, the hardest, the whole getting injured, even worse than getting injured, about a few weeks before it when I could run, change direction, sprint, I could do everything, but I still wasn’t allowed to play and ermm that was tough. (Ava)

I think one thing that gets missed out is new signings because you get replaced without even, you know, you're a fixture in the team and the next minute someone comes in and no one has had a conversation with you and you just know you’re not playing anymore. They did not rate me or think I was good enough so I'm not worth it or not good enough. That self-worth and self-doubt creeps in. (Sara)

I was released by [club] over the phone in a two-minute conversation … I was devastated … There’s no understanding you’ve just crushed me in a second … I honestly just sat and cried. (Sara)

I don’t know if this is off topic, but being gay and all that, being in a football environment where it’s stereotypically more lesbians. In my sexuality, it made me feel comfortable because you’ve got that sort of similarities and you talk about your past and it’s similar … I just think football made me feel more comfortable in my sexuality and I could talk about. (Maya)

Speaking out about my mental health: the confusion and the cost

Despite a changing culture in both sport and wider society in speaking about mental health in recent years, barriers to help-seeking and limited understanding of mental health were evident. Participants’ responses did not reflect environments that fostered a culture of well-being, encouraged open dialogues, and provided appropriate support in relation to poor mental health. Mental health difficulties were perceived as incompatible with soccer, with players feeling judged when showing signs of emotional struggle:

I had to come off. I had to come off the pitch. I think people looked at me and thought I was probably weird, why is she captain, probably judged me a lot about that. That was hard because I was in so much pain, instead of people helping me in that situation and asking if I was alright, I think they were sort of, like, looked down on me for that. They saw me as a disappointment, rather than someone going through a really rough time. (Maya)

It’s hard because … you’d expect with women’s mental health, like with men you’d expect it quite high because they don’t talk about it, but women tend to be more emotional, they talk more, they talk to other women with stuff like that but in football you just don’t. I think it’s, it’s sort of like, it’s that masculine, like, I don’t know how to describe it. Masculine traits, you know, football is a male predominant sport and that’s what it’s known for. (Mia)

I had a game where I was dropped like quite out of the blue which when asked it was a response to my mental health which promoted a conversation. But I think it acted as an example, it was almost a reminder of not to bring my mental health in football which is probably how it should not have been.

So I was depressed, typically didn’t want to leave the house. We had a new manager; I text her and never had met her but text her to tell her I was really struggling with what I thought was depression, I haven't left the house. It’s not that I don’t want to be there it’s that I can’t be there. But I never even got a reply. So, I never went back, so I didn’t play for a year and a half. No one wanted me to come back, no cared so I might as well just not play. (Sara)

I think there would be some kind of like judgement passed somewhere that would affect football, I don't think there is the option for an independent person. Which I do sometimes think is needed because I do think you need to tell coaching staff how you’re feeling because it had such a big impact on performance but you need to do it with the confidence it’s not going to affect any decision made about your football so I think that’s a big challenge in women’s football. (Emma)

Limited understanding and awareness of mental health issues within the soccer environment contributed to a lack of knowledge about appropriate help-seeking behaviours and prevented early identification of mental ill-health. Players discussed moments when they became aware of their mental ill-health, which involved delayed help-seeking and struggling to recognise their own symptoms. Physical symptoms appeared to be a sign that became a part of a diagnosis as well as help-seeking for Sara: “I was depressed but I didn’t really realize that I was until it got to the point when someone said please don’t lose any more weight … I didn’t think there was anything wrong with me”.

Discussion

The present study provides insight into both the prevalence of mental ill-health symptoms and the complexities of how mental health is perceived, interpreted, and experienced in a unique and under-researched population. We have addressed a need for methodologically diverse research examining specific competitive levels for female athletes (Perry et al., Citation2021). The findings revealed high prevalence rates for mental ill-health symptoms in semi-elite female footballers and revealed players’ complex and nuanced experiences.

This study supports previous literature reporting high prevalence rates for high-level athletes compared to the general population (Junge & Prinz, Citation2019; Nixdorf et al., Citation2013; Perry et al., Citation2022). The prevalence of mental ill-health symptoms was higher than the general population for UK females (Stansfeld et al., Citation2016) and British elite athletes (Gouttebarge et al., Citation2019). Mental ill-health symptoms were higher than previously reported literature assessing female footballers (Junge & Feddermann-Demont, Citation2016; Junge & Prinz, Citation2019; Kilic et al., Citation2021; Perry et al., Citation2022). Prinz et al. (Citation2016) reported higher levels of depression in German female footballers than in the present sample, however this related to lifetime prevalence rather than point prevalence, as participants were asked to recall the worst time in their life.

The prevalence of the likelihood of having an eating disorder was lower than previous literature (Gulliver et al., Citation2015); however, this was reported when sampling a range of elite athletes, including in sports seen as aesthetic sports where females are suggested to be at greater risk of eating disorders (Coyle et al., Citation2017). Studies reporting on elite female footballers also reported higher prevalence rates for symptoms associated with disordered eating (Kilic et al., Citation2021; Perry et al., Citation2022). Perry et al. (Citation2022) also found high levels of disordered eating symptoms to be associated with “part-time” student-athletes which resonates with the employment status of the participants in the present study. The differences may be due to instrument choices (BEDA-Q compared to SCOFF), signalling the importance of using consistent measurement tools when assessing the prevalence of mental health symptoms (Perry et al., Citation2022).

The range of mental health risk factors identified by participants broadly align with the existing literature, including injury (Biggin et al., Citation2017; Coyle et al., Citation2017; Gouttebarge et al., Citation2015b; Schaal et al., Citation2011) deselection, and performance-driven cultures (Poucher et al., Citation2023; Wood et al., Citation2017). Our findings also highlight the importance of acknowledging the wider ecological factors and context of how the sports system influences mental health (Maher, Citation2022; Poucher et al., Citation2023; Purcell et al., Citation2019, Citation2022). The female footballers reported athlete-specific risk factors for mental ill-health at the individual level, team level, and an organisational level. Similarly, to Poucher et al. (Citation2023), there were several features of the soccer environment that could be protective and risk factors.

Participant responses were centred around the key theme on navigating the professionalisation of women’s soccer and how the notion of gender differences between women's and men's soccer contributed to their mental health experiences. This highlights that the difficulties women in sporting environments face, such as legitimacy and credibility (Bowes & Culvin, Citation2021), contribute to mental health challenges. Females in semi-professional environments, do not receive equivalent financial remuneration for their investment in their sport, which means players are required to balance study or work alongside their sporting demands (Culvin & Bowes, Citation2023). The findings of this research demonstrate some of the implications of this balancing act on mental health.

Participants stressed how concurrent demands, along with limited mental health support at soccer produced high psychological strain. This supports Sallen et al. (Citation2018) who found high indicators of stress in elite student-athletes pursuing university careers as well as elite sporting success. This finding provides a foundation to suggest that engaging in a dual-career may challenge athlete mental health, addressing gaps in the literature regarding dual-career athletes and mental health (Stambulova & Wylleman, Citation2019). It has also been suggested that dual careers can be protective by enabling players to develop a sense of self-authenticity, and alternative non-sporting careers (Coyle et al., Citation2017; Wylleman & Lavallee, Citation2004). Kerr and Dacyshyn (Citation2000) discovered that former gymnasts who achieved the correct balance between sporting and non-sporting lifestyles throughout their athletic careers reported increased life satisfaction after retirement. Our findings and dual-career research (e.g., Douglas & Carless, Citation2006; Pink et al., Citation2018; Price et al., Citation2010) suggest that the positive benefits of sporting and non-sporting demands are achieved when a balance is maintained. Athletes who lack balance have been reported to experience increased levels of fatigue, stress, and burnout (Vallerand & Verner-Fillion, Citation2020). In the present study, the footballers perceived a lack of control and an imbalance between multiple demands, therefore leading to mental health difficulties, particularly when sport-specific factors that influence mental health (i.e., injury, deselection, poor coach-athlete relationships, pressure to perform) were present making balancing life stressors difficult (Burns & Machin, Citation2013).

Coaches were discussed as a key element of the experiences of mental health. Emphasis was placed on how the coach impacts the athletes as well as their role to support athletes holistically, aligning with the athlete mental health position statement by Van Slingerland et al. (Citation2019). Despite coaches perceiving their role to be diverse and inclusive of promoting mental health (Ferguson et al., Citation2019), our findings indicate that players perceive that coaches, at times, fail to appropriately support athlete mental health and/or fail to foster environments that do, exacerbating performance-related pressure. Coaches have expressed a lack of clear understanding of mental health due to superficial, insufficient, and non-sport-specific resources and mental health training (Warden et al., Citation2023). Coaches’ involvement in athlete mental health is complex and influences the openness of players to talk to coaches about mental health. Where coaches do not directly negatively impact the emotional state of players, a perception that coaches lack understanding of mental health and role conflict between performance and well-being, produces uncertainty in players. Trust and confidentiality in coaches (Gulliver et al., Citation2012; Lundqvist & Sandin, Citation2014; Poucher et al., Citation2023) and encouragement towards help-seeking (Gulliver et al., Citation2012) have been reported as beneficial to help-seeking. Therefore, coaches should foster high-quality relationships with their athletes based on trust (Lundqvist & Raglin, Citation2015; Simons & Bird, Citation2022). Coaches are key to striving to improve the narrative toward mental health in sports settings (Purcell et al., Citation2022), by helping to establish team cultures that normalise, de-stigmatise, and support mental health (Bissett et al., Citation2020).

It is important to recognise that coaches are only one part of the soccer system, and it is just as important to enhance their mental and emotional development (Maher, Citation2022). Integrating psychological health professionals, who possess a unique skill set, especially for early detection of mental ill-health (Lebrun et al., Citation2020), into coaching teams can be a crucial step in offering social support to athletes and coaches in competitive settings. However, not all clubs are developing in the same manner and some are unlikely to have the resources to hire specialists or develop context-specific programs. Therefore, there is a need to develop and implement a referral network for coaches to use for advice and signposting (Lebrun et al., Citation2020).

Strengths, limitations, and future research

This research addresses issues cited by Perry et al. (Citation2021) surrounding the breadth of sports previously explored in studies. Focusing on women’s “semi-elite” soccer provides context-specific insights into mental health experiences and the elements that are conducive to mental ill-health (Castaldelli-Maia et al., Citation2019). The exploratory nature of the study provides foundations for future research to further explore various concepts and findings. Furthermore, we extend recent studies within women’s soccer (Perry et al., Citation2022) by qualitatively exploring players’ lived experience of mental ill-health in this context. This research also sheds light on the individual complexities women face when establishing a career in a predominantly male-dominated field (Bowes & Culvin, Citation2021). Through the female participants articulating their experiences, concerning their mental health, this research responds to the need for the depiction of gender-specific experience within women’s soccer (Culvin & Bowes, Citation2023).

There are however some limitations. Firstly, using self-report measures in both phases could raise concerns about underestimated prevalence rates (Kilic et al., Citation2017) and truthfulness (Hill et al., Citation2015), although the online format and anonymity option for the questionnaires may have reduced social desirability. Self-identified mental ill-health also limits the construct validity of conclusions made (Wood et al., Citation2017), although all the participants interviewed mentioned clinical diagnosis and treatment for mental health disorders. Equally, the aim was to assess mental health symptoms and context-specific experiences, therefore the self-report questionnaires were not for diagnostic purpose. Therefore, the prevalence rates reflect athletes with varying (ranging from mild to severe) levels of symptoms associated with mental health disorders, identifying individuals who may be at risk of developing a mental health disorder, and/or whose state of dynamic wellbeing is negatively affected.

Secondly, as the interview sample only consisted of those who reported high levels of mental ill-health, their responses may bias towards negative experiences. Psychological disposition may influence mental health and responses to stressors and sport-specific factors (e.g., feedback from coaches, deselection, injury, poor performance, and pressure to perform) may be internalised (Nixdorf et al., Citation2013) or appraised (Fletcher et al., Citation2012) differently by players. Interviewing those who reported positive mental health would be useful to understand the broader picture and different experiences of mental health within semi-elite women’s soccer. Furthermore, the sampling criteria for the interviews meant that some participants with high levels of symptoms associated with only one mental health disorder, who did not report mild symptoms for other conditions were not included. This can make it challenging to accurately identify and differentiate between symptoms and experiences. At an individual level, different disorders may need different interventions; however, we believe that the players’ responses reflect team and organisational features that influence all domains of mental health.

Future research may further explore the role of the coach supporting athlete mental health specifically within this population. It would be worthy to understand how limited resources influence the coach’s role to support athlete mental health from a player and coach perspective. This study may offer a valuable starting point for investigations on the mental health of dual-career athletes and student-athletes, inclusive of elite athletes who are exposed to concomitant sport and other domain loads (Condello et al., Citation2019).

Practical applications

This research highlights the need for a system-wide approach to support mental health in women’s semi-elite soccer. A system approach views interrelationships at an individual, team, and organisational level (Maher, Citation2022). Our research shows that the prevalence of mental ill-health symptoms differs based on the context of the sport (Rice et al., Citation2016; Schaal et al., Citation2011). Even when comparing female athletes within the same sport and country (e.g., Perry et al., Citation2022) there are differences in prevalence rates of mental ill-health between competition levels (tiers one and two vs tier three). Therefore, context-specific mental health interventions are required within women’s semi-elite soccer. These interventions should consider the broader ecology of sporting environments (Purcell et al., Citation2019) and tailor solutions to each level within the tier three women’s soccer environment (Oftadeh-Moghadam et al., Citation2023). Educational mental health interventions that have been designed to be sport and gender specific have been successful in enhancing mental health literacy of athletes and reducing stigmatising attitudes towards help-seeking (Oftadeh-Moghadam et al., Citation2023).

The current lack of support and provision for mental health has implications for wider organisational support and delivery of interventions from the FA (Wood et al., Citation2017). Funding agencies may extend criteria to include wellbeing and mental health development targets (Poucher et al., Citation2021). Historical evidence highlights the tendency for the FA to cut women’s funding during financially challenging time (Clarkson et al., Citation2021), however, the present study highlights the need to work harder and apply collective pressure for support in women’s sport. Furthermore, educating female footballers about mental health may prevent the development of mental ill-health at an individual level. Tools and techniques to manage multiple demands that female footballers balance in their lives may provide foundations to positive mental health and coping. This aligns with the strategy proposed by Hill et al. (Citation2015), who highlight the need for appropriate support and identification of potential mental health difficulties. This research also sheds light on the individual complexities women face when establishing a career in the predominantly male-dominated field of sports (Bowes & Culvin, Citation2021)

Conclusion

Semi-elite female footballers in this study reported high prevalence of mental ill-health symptoms and experienced a complex interplay of balancing demands and inherent characteristics within the soccer ecosystem. Footballers were exposed to sport-specific risk factors, similar to those elite athlete’s face, as well as stressors relating to balancing concurrent demands. We have enhanced understanding of the key features of the sport environment and system within tier three women’s soccer in the UK that influences mental health. This provides direction towards the areas to develop and improve to develop mentally healthy soccer organisations and athletes.

Ethics approval

Obtained from School of Science and Technology, Non-Invasive Humans Ethics Committee, Nottingham Trent University, Nottinghamshire, England. 1920–60.

Supplemental Tables and Figures

Download MS Word (647.1 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants a part of this research, and those who supported access to participants. We would like to acknowledge and thank Carly Perry for their expertise and assistance throughout aspects of this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Deidentified quantitative data will be accessible upon request. To maintain the confidentiality of the participants the interview data is not available.

References

- Åkesdotter, ., Kenttä, G., & Sparkes, A. C. (2023). Elite athletes seeking psychiatric treatment: Stigma, impression management strategies, and the dangers of the performance narrative. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 36(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2023.2185697

- Åkesdotter, C., Kenttä, G., Eloranta, S., Håkansson, A., & Franck, J. (2022). Prevalence and comorbidity of psychiatric disorders among treatment-seeking elite athletes and high-performance coaches. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 8(1), Article e001264. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001264

- Biddle, C., & Schafft, K. A. (2015). Axiology and anomaly in the practice of mixed methods work: Pragmatism, valuation, and the transformative paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(4), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689814533157

- Biggin, I. J., Burns, J. H., & Uphill, M. (2017). An investigation of athletes’ and coaches’ perceptions of mental ill-health in elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 11(2), 126–147. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.2016-0017

- Bissett, J. E., Kroshus, E., & Hebard, S. (2020). Determining the role of sport coaches in promoting athlete mental health: A narrative review and Delphi approach. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 6(1), Article e000676. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000676

- Bowes, A., & Culvin, A. (Eds.)( (2021). The professionalisation of women’s sport: Issues and debates. Emerald.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith, & A. Sparkes (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 191–295). Routledge.

- Burns, R. A., & Machin, M. A. (2013). Psychological wellbeing and the diathesis-stress hypothesis model: The role of psychological functioning and quality of relations in promoting subjective well-being in a life events study. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.09.017

- Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Gallinaro, J. G. D. M. e., Falcão, R. S., Gouttebarge, V., Hitchcock, M. E., Hainline, B., & Stull, T. (2019). Mental health symptoms and disorders in elite athletes: A systematic review on cultural influencers and barriers to athletes seeking treatment. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100710

- Clarkson, B. G., Bowes, A., Lomax, L., & Piasecki, J. (2021). The gendered effects of COVID-19 on elite women’s sport. In A. Bowes, & A. Culvin (Eds.), The professionalisation of women’s sport: Issues and debates (pp. 229–244). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Condello, G., Capranica, L., Doupona, M., Varga, K., & Burk, V. (2019). Dual-career through the elite university student-athletes’ lenses: The international FISU-EAS survey. PLoS One, 14(10), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223278

- Coyle, M., Gorczynski, P., & Gibson, K. (2017). “You have to be mental to jump off a board any way”: Elite divers’ conceptualizations and perceptions of mental health. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 29, 10–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2016.11.005

- Creswell, J. W. (2014). A concise introduction to mixed methods research. SAGE Publications.

- Culvin, A. (2021). Football as work: The lived realities of professional women footballers in England. Managing Sport and Leisure, 28(6), 684–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2021.1959384

- Culvin, A., & Bowes, A. (2023). Women’s football in a global, professional era. Emerald.

- Douglas, K., & Carless, D. (2006). The performance environment: A study of the personal, lifestyle and environmental factors that affect sporting performance. UK Sport. http://www.bristol.ac.uk/enhs/perexecutive-report.pdf

- Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105

- Ferguson, H. L., Swann, C., Liddle, S. K., & Vella, S. A. (2019). Investigating youth sports coaches’ perceptions of their role in adolescent mental health. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 31(2), 235–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200.2018.1466839

- Fletcher, D., Hanton, S., Mellalieu, S. D., & Neil, R. (2012). A conceptual framework of organizational stressors in sport performers. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 22(4), 545–557. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01242.x

- Foskett, R. L., & Longstaff, F. (2018). The mental health of elite athletes in the United Kingdom. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 21(8), 765–770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2017.11.016

- Ghiara, V. (2020). Disambiguating the role of paradigms in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689818819928

- Gouttebarge, V., Aoki, H., & Kerkhoffs, G. (2015a). Symptoms of common mental disorders and adverse health behaviours in male professional soccer players. Journal of Human Kinetics, 49(1), 277–286. https://doi.org/10.1515/hukin-2015-0130

- Gouttebarge, V., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., Gorczynski, P., Hainline, B., Hitchcock, M. E., Kerkhoffs, G. M., Rice, S. M., & Reardon, C. L. (2019). Occurrence of mental health symptoms and disorders in current and former elite athletes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(11), 700–706. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100671

- Gouttebarge, V., Frings-Dresen, M., & Sluiter, J. (2015b). Mental and psychosocial health among current and former professional footballers. Occupational Medicine, 65(3), 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu202

- Gulliver, A. (2017). Commentary: Mental health in Sport (MHS): Improving the early intervention knowledge and confidence of elite sport staff. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1209–1209. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01209

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2012). Barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking for young elite athletes: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 12(1), Article 157. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-157

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., Mackinnon, A., Batterham, P. J., & Stanimirovic, R. (2015). The mental health of Australian elite athletes. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(3), 255–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2014.04.006

- Harrison, R. L., Reilly, T. M., & Creswell, J. W. (2020). Methodological rigor in mixed methods: An application in management studies. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 14(4), 473–495. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689819900585

- Henderson, A., Harris, S. A., Kirkham, T., Charlesworth, J., & Murphy, M. C. (2023). What is the prevalence of general anxiety disorder and depression symptoms in semi-elite Australian football players: A cross-sectional study. Sports Medicine - Open, 9(1), 42–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-023-00587-3

- Henriksen, K., Schinke, R., Moesch, K., McCann, S., Parham, W. D., Larsen, C. H., & Terry, P. (2020). Consensus statement on improving the mental health of high performance athletes. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(5), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2019.1570473

- Hill, A., MacNamara, Á, Collins, D., & Rodgers, S. (2015). Examining the role of mental health and clinical issues within talent development. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, Article 2042. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02042

- Junge, A., & Feddermann-Demont, N. (2016). Prevalence of depression and anxiety in top-level male and female football players. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 2(1), Article e000087. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2015-000087

- Junge, A., & Prinz, B. (2019). Depression and anxiety symptoms in 17 teams of female football players including 10 German first league teams. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 53(8), 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2017-098033

- Kerr, G., & Dacyshyn, A. (2000). The retirement experiences of elite, female gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 12(2), 115–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200008404218

- Kessler, R. C., Barker, P. R., Colpe, L. J., Epstein, J. F., Gfroerer, J. C., Hiripi, E., & Walters, E. E. (2003). Screening for serious mental illness in the general population. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60(2), 184–189. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.184

- Kilic, Ö, Aoki, H., Haagensen, R., Jensen, C., Johnson, U., Kerkhoffs, G. M. M. J., & Gouttebarge, V. (2017). Symptoms of common mental disorders and related stressors in Danish professional football and handball. European Journal of Sport Science, 17(10), 1328–1334. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2017.1381768

- Kilic, Ö, Carmody, S., Upmeijer, J., Kerkhoffs, G. M. M. J., Purcell, R., Rice, S., & Gouttebarge, V. (2021). Prevalence of mental health symptoms among male and female Australian professional footballers. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 7(3), Article e001043. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001043

- Küttel, A., & Larsen, C. H. (2020). Risk and protective factors for mental health in elite athletes: A scoping review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(1), 231–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2019.1689574

- Küttel, A., Pedersen, A. K., & Larsen, C. H. (2021). To flourish or languish, that is the question: Exploring the mental health profiles of Danish elite athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 52, Article 101837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101837

- Lebrun, F., MacNamara, À, Collins, D., & Rodgers, S. (2020). Supporting young elite athletes with mental health issues: Coaches’ experience and their perceived role. The Sport Psychologist, 34(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2019-0081

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2009). A typology of mixed methods research designs. Quality & Quantity, 43(2), 265–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9105-3

- Lundqvist, C., & Raglin, J. S. (2015). The relationship of basic need satisfaction, motivational climate and personality to well-being and stress patterns among elite athletes: An explorative study. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 237–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-014-9444-z

- Lundqvist, C., & Sandin, F. (2014). Well-being in elite sport: Dimensions of hedonic and eudaimonic well-being among elite orienteers. The Sport Psychologist, 28(3), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2013-0024

- Maher, C. A. (2023). Fostering the mental health of athletes, coaches, and staff: A systems approach to developing a mentally healthy sport organization. Routledge.

- Morgan, J. F., Reid, F., & Lacey, J. H. (1999). The SCOFF questionnaire: Assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. British Medical Journal, 319(7223), 1467–1468. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.319.7223.1467

- Nixdorf, I., Frank, R., Hautzinger, M., & Beckmann, J. (2013). Prevalence of depressive symptoms and correlating variables among German elite athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 7(4), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1123/jcsp.7.4.313

- Oftadeh-Moghadam, S., Weston, N., & Gorczynski, P. (2023). Mental health literacy intervention to reduce stigma toward mental health symptoms and disorders in women rugby players: A feasibility study. The Sport Psychologist, 37(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2022-0142

- Perry, C., Champ, F. M., Macbeth, J., & Spandler, H. (2021). Mental health and elite female athletes: A scoping review. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 56, Article 101961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101961

- Perry, C., Chauntry, A. J., & Champ, F. M. (2022). Elite female footballers in England: An exploration of mental ill-health and help-seeking intentions. Science and Medicine in Football, 6(5), 650–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/24733938.2022.2084149

- Pink, M. A., Lonie, B. E., & Saunders, J. E. (2018). The challenges of the semi-professional footballer: A case study of the management of dual career development at a Victorian Football League (VFL) club. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 35, 160–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.12.005

- Poucher, Z. A., Tamminen, K. A., & Kerr, G. (2023). Olympic and paralympic athletes’ perceptions of the Canadian sport environment and mental health. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 15(5), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2023.2187443

- Poucher, Z. A., Tamminen, K. A., & Wagstaff, C. R. D. (2021). Organizational systems in British sport and their impact on athlete development and mental health. The Sport Psychologist, 35(4), 270–280. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.2020-0146

- Prather, H., Hunt, D., McKeon, K., Simpson, S., Meyer, E. B., Yemm, T., & Brophy, R. (2016). Are elite female soccer athletes at risk for disordered eating attitudes, menstrual dysfunction, and stress fractures? PM&R, 8(3), 208–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.07.003

- Price, N., Morrison, N., & Arnold, S. (2010). Life out of the limelight: Understanding the Non-sporting pursuits of elite athletes. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 1(3), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.18848/2152-7857/CGP/v01i03/54034

- Prinz, B., Dvořák, J., & Junge, A. (2016). Symptoms and risk factors of depression during and after the football career of elite female players. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 2(1), Article e000124. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2016-000124

- Purcell, R., Gwyther, K., & Rice, S. M. (2019). Mental health In elite athletes: Increased awareness requires An early intervention framework to respond to athlete needs. Sports Medicine - Open, 5(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-019-0220-1

- Purcell, R., Pilkington, V., Carberry, S., Reid, D., Gwyther, K., Hall, K., Deacon, A., Manon, R., Walton, C. C., & Rice, S. (2022). An evidence-informed framework to promote mental wellbeing in elite sport. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 780359. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.780359

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306

- Rice, S. M., Purcell, R., De Silva, S., Mawren, D., McGorry, P. D., & Parker, A. G. (2016). The mental health of elite athletes: A narrative systematic review. Sports Medicine, 46(9), 1333–1353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0492-2

- Sallen, J., Hemming, K., & Richartz, A. (2018). Facilitating dual careers by improving resistance to chronic stress: Effects of an intervention programme for elite student athletes. European Journal of Sport Science, 18(1), 112–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2017.1407363

- Schaal, K., Tafflet, M., Nassif, H., Thibault, V., Pichard, C., Alcotte, M., Guillet, T., El Helou, N., Berthelot, G., Simon, S., & Toussaint, J.-F. (2011). Psychological balance in high level athletes: Gender-based differences and sport-specific patterns. PLoS One, 6(5), Article e19007. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0019007

- Simons, E. E., & Bird, M. D. (2022). Coach-athlete relationship, social support, and sport-related psychological well-being in national collegiate athletic association division I student-athletes. Journal for the Study of Sports and Athletes in Education, 17(3), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19357397.2022.2060703

- Smith, B., & Caddick, N. (2012). Qualitative methods in sport: A concise overview for guiding social scientific sport research. Asia Pacific Journal of Sport and Social Science, 1(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640599.2012.701373

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092

- Stambulova, N. B., & Wylleman, P. (2019). Psychology of athletes’ dual careers: A state-of-the-art critical review of the European discourse. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 42, 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.013

- Stansfeld, S., Clark, C., Bebbington, P., King, M., Jenkins, R., & Hinchliffe, S. (2016). Chapter 2: Common mental disorders. In S. McManus, P. Bebbington, R. Jenkins, & T. Brugha (Eds.), Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult psychiatric morbidity survey 2014 (pp. 37–68). NHS Digital. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/t/6/adult_psychiatric_study_ch2_web.pdf.

- Swann, C., Moran, A., & Piggott, D. (2015). Defining elite athletes: Issues in the study of expert performance in sport psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.004

- Tahtinen, R. E., Shelley, J., & Morris, R. (2021). Gaining perspectives: A scoping review of research assessing depressive symptoms in athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 54, Article 101905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101905

- Vallerand, R. J., & Verner-Filion, J. (2020). Theory and research in passion for sport and exercise. In G. Tenenbaum, & R. Eklund (Eds.), Handbook of sport psychology (pp. 206–229). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119568124.ch11

- Van Slingerland, K. J., Durand-Bush, N., Bradley, L., Goldfield, G., Archambault, R., Smith, D., Edwards, C., Delenardo, S., Taylor, S., Werthner, P., & Kenttä, G. (2019). Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport (CCMHS) position statement: Principles of mental health in competitive and high-performance sport. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 29(3), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0000000000000665

- Vella, S. A., Schweickle, M. J., Sutcliffe, J. T., & Swann, C. (2021). A systematic review and meta-synthesis of mental health position statements in sport: Scope, quality and future directions. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, Article 101946. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101946

- Walton, C. C., Carberry, S., Wilson, M., Purcell, R., Olive, L., Vella, S., & Rice, S. (2022). Supporting mental health in youth sport: Introducing a toolkit for coaches, clubs, and organisations. International Sport Coaching Journal, 9(2), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2021-0042

- Warden, S., Doncaster, G., Greenough, K., & Smith, A. (2023). Examining sports coaches’ mental health literacy: Evidence from UK athletics. Sport, Education and Society, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2023.2214160

- Westerhof, G. J., & Keyes, C. L. (2010). Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development, 17(2), 110–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9082-y

- Wood, S., Harrison, L. K., & Kucharska, J. (2017). Male professional footballers’ experiences of mental health difficulties and help-seeking. The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 45(2), 120–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.2017.1283209

- Wylleman, P., & Lavallee, D. (2004). A developmental perspective on transitions faced by athletes. In M. R. Weiss (Ed.), Developmental sport and exercise psychology: A lifespan perspective (pp. 507–527). Fitness Information Technology.