ABSTRACT

Values-based education seeks to cultivate personal responsibility, empathy, and integrity to encourage critical reflection on the (anticipated or actual) consequences of one’s choices and behaviours. To comply with the World Anti-Doping Agency's International Standard for Education, anti-doping education programmes must incorporate values-based components. To facilitate this development, we explored how elite athletes interpret and apply their values in various situations throughout their athletic careers. Adopting a qualitative description design, 13 focus groups were conducted with 60 elite athletes from 13 countries participating in 27 sports at national or international levels. Audio recordings were transcribed/translated and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Athletes noted that their values guide their actions but struggled to articulate how these values influence their behaviour. Three overarching themes were created to capture: (1) value consciousness and clarity, (2) intrapersonal value continuity, and (3) value conflict and management. Dynamic relationships between athletes’ values, priorities, and decision-making processes were evident. Specifically, the results illustrate shifts in value priorities as athletes matured and progressed in their careers, and across situations to meet situational demands whilst making behaviour personally permissible. To live up to the fundamental principles of values-based education, anti-doping programmes must incorporate activities that facilitate conceptually sound discussions and provide athletes with time and support to unpack the behavioural meaning of their values. Developing athletes’ decision-making abilities through conscious sense-making activities to anticipate the pain of a value transgression and the value of value fulfilment is key to this process.

Background

Mandated by the World Anti-Doping Code (WADC), anti-doping programmes are set to “maintain the integrity of sport in terms of respect for rules, other competitors, fair competition, a level playing field and the value of clean sport to the world” (WADA, Citation2021a, p. 13). This intrinsic value is interchangeably referred to as the “values of sport” or “the spirit of sport”. The spirit of sport, defined in the WADC as 11 sport-specific values (i.e., health, ethics and fair play, excellence, character, fun and joy, teamwork, dedication, respect for rules, respect for self and others, courage, and solidarity), are not a fixed set of attributes, but rather a dynamic collection of principles which serve as the foundation of the WADC and change in response to the changing demands of the sport environment (WADA, Citation2021a). The recent inclusion of athletes’ rights as the 12th “value” into the 2021 WADC exemplifies the practical and dynamic nature of the spirit of sport concept as underpinning principles for anti-doping. Since 2021, values-based education (VbE) is a mandatory element of anti-doping education (WADA, Citation2021b).

The World Anti-Doping Agency’s (WADA) values-based approach also emphasises the development of personal values and principles but with an emphasis on those that protect the spirit of sport and foster a clean sport environment (WADA, Citation2021b). The guidelines of the World Anti-Doping Agency's International Standard for Education (ISE) state that all participants should be exposed to a common set of positive values, regardless of their sport or background (WADA, Citation2020a). Notably, the ISE emphasises identifying and promoting values that are deemed important by the organisations responsible for anti-doping and delivering education. Congruently, it approaches values-based education by promoting societal values (of sport) assuming that when these are “translated”, internalised, and adopted by athletes, they lead to implementing desirable behavioural choices (e.g., rule compliance, whistleblowing) and avoiding undesirable ones (e.g., doping). Extensive research into values (see Hitlin & Piliavin, Citation2004 for a review) suggests that this is not that simple. Firstly, general societal and cultural values are learned through observational learning in upbringing (Bandura & Walters, Citation1977), whereas athletes encounter specific values, such as the values of sport, later in life. Learning and internalisation processes in adulthood are different than those in early formative years (Boer & Boehnke, Citation2016), thus requiring tailored exercises and activities such as roleplay, theatre for development or situated sense-making exercises (e.g., Hauw, Citation2013). Secondly, athletes’ idiosyncratic and dynamic value systems may or may not match the values agreed upon and set at an organisational level (Schwartz, Citation1996). Finally, athletes may face intra – and interpersonal value conflicts, and their solutions to these conflicts may not align with the desired outcome determined by the organisations delivering VbE for anti-doping. For instance, an athlete having knowledge of anti-doping rule violations among fellow athletes (e.g., TUE failure, complicity in doping) may prioritise conformity values and team harmony and decide not to report the suspected doping misconduct to the relevant authorities as expected but seek an alternative resolution instead by confronting the perpetrator directly (Erickson et al., Citation2019). These factors can lead to a misalignment between organisational missions and decision-making by athletes in daily situations, which has been flagged as potentially problematic for the implementation of the WADA standard (Blank & Petróczi, Citation2023; Petróczi & Boardley, Citation2022). These are especially problematic if what is delivered in practice materialises in short sessions of values-education (i.e., promoting a set of values), not values-based education in its true sense of providing an environment in which learners experience, explore, and reflect on the promoted positive values (values-based Education, Citationn.d.).

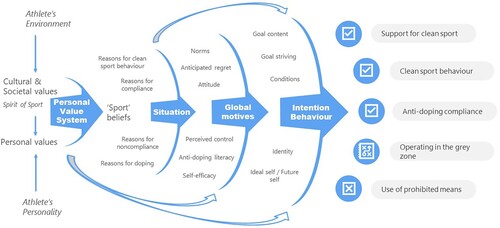

Values may be expressed, albeit in some cases imprecisely, as universal guiding principles, (static) mental structures, goals, social norms, or desired personality traits (Hitlin & Piliavin, Citation2004). To appreciate the complexity of how values operate in action, we need to consider the cornerstones of values-based anti-doping education, namely: what values are (and what they are not), what values-based education means outside anti-doping and how it is delivered, how personal values are operationalised in behavioural choices, and how athletes view the “spirit of sport”. Modified from Westaby’s (Citation2005) Behavioural Reasoning Theory, depicts this complexity and the tenuous influence of societal values (spirit of sport) on individual actions. Based on the pertinent literature (see Hitlin & Piliavin, Citation2004; Park, Citation2010), values may not exert a direct influence on behavioural choices or actions. Rather, values work through reasons, global motives (including attitudes), personal goals and goal striving, identities, and future selves. Behavioural choices are first and foremost guided by personal values and not societal or cultural values. The latter two exert influence on behaviour but do not replace nor overwrite personal values. Complicating the matter further, the relative importance of personal values, as well as their links to actions, are both situated and dynamic, thus can change from one context to the next, and over time; and are influenced by cultural and societal values in athletes’ environments.

The consequence of this complexity is not purely academic but also practical. Developers of values-based anti-doping education programmes must have a clear view of how and through which pathways they expect the desired impact from values to actions. A clear idea about the intended and measurable impact of VbE is also needed for evaluating the effectiveness of the implemented VbE activities (Blank & Petróczi, Citation2023).

The spirit of sport and the athletes

Dominated by medical, social, legal, and ethical discursions, the spirit of sport is a multivalent and often contested concept in the literature that lacks robust empirical data from stakeholders, especially athletes (Obasa & Borry, Citation2019). To date, relatively little is known about how much organisational values on anti-doping coincide with athletes’ personal values. Literature on the “values of sport” as the “spirit of sport” is limited to a small number of studies which predominantly focused on differences between athletes and the general public (Mazanov & Huybers, Citation2015) and cultural differences (Mazanov et al., Citation2019; Woolway et al., Citation2021). Both studies on the latter suggest that there are differences in how individuals prioritise the spirit of sport values across different cultures and countries. One plausible explanation for the observed cross-national differences in the relative importance of values is the dynamic changes in value priorities at the individual level (Mazanov et al., Citation2012). These findings further corroborate Mazanov et al.’s (Citation2019) conclusion that the moral component of anti-doping is less universal than is assumed by supporters of the anti-doping movement (Van Bottenburg et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, the relative unimportance of “excellence in performance” in previous studies likely resulted from the sample composition, which was characteristically the general population, students, and/or athletes with very few involved in high-performance sport.

What we know about values in clean sport vs. doping behaviour

Mortimer et al. (Citation2021) found that the likelihood of athletes practising clean sport in a hypothetical scenario was positively associated with the social dimensions of the spirit of sport, specifically “ethics, fair play, and honesty”, “respect for rules and laws”, “teamwork” and “community and solidarity” and the personal focused “dedication and commitment”. Linking universal values to the spirit of sport, this observation is further supported by Ring et al. (Citation2022) who – using hypothetical scenarios – observed that the likelihood of doping was positively and directly associated with self-enhancement values (e.g., power, achievement), but negatively and indirectly associated with self-transcendence (e.g., benevolence, universalism), and conservation values (e.g., conformity, security). This pro-doping functional (i.e., doping as an enabler or enhancer) and anti-doping moral values-based (i.e., doping as cheating) dichotomy has also developed from reasons for and against doping (Erickson et al., Citation2015; Kegelaers et al., Citation2018; Overbye et al., Citation2013). Given free will, which is not always the case in elite sport (see Altukhov & Nauright, Citation2018), competitive athletes stay away from doping because of their values against cheating (as opposed to values against using doping for performance enhancement). Any link between clean sport behaviour and the spirit of sport in this subpopulation, therefore, is likely to be caused by the close alignment of general values preventing cheating in sport with the moral values among the spirit of sport values. Empirical evidence supports the notion that an athlete’s intention to cheat and cheating in sport are influenced by the athlete’s personality, personal values, and social environment (Sipavičiūtė & Šukys, Citation2019). Specifically, cheating behaviour and doping have been linked to machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy (Nicholls et al., Citation2020) and perfectionism (Madigan et al., Citation2020), but this relationship is influenced by motivation (Mudrak et al., Citation2018) and goal orientation (Hardwick et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, motivational climate and personal environment, particularly coaches, appear to influence athletes’ attitudes towards cheating and doping use (e.g., Barkoukis et al., Citation2019). Having doping users in the athlete’s environment was also found to be one of the strongest predictors of doping use (Ntoumanis et al., Citation2014).

In addition to the scarcity of elite athletes among the participants, lack of personal focus or real-life setting, a major limitation of the studies conducted to date on the importance of the spirit of sport values, and their connection to doping or clean sport behaviour, is that they provide only a snapshot of athlete-endorsed values and self-reported behaviour or willingness in hypothetical scenarios. In doing so, they fail to capture the dynamics of multiple values and value priorities (Russo et al., Citation2022). Specifically, how values and value priorities may change over time with maturity and experiences, how value priorities are constantly (but not necessarily consciously) adjusted to the situational demands, and how value conflicts manifest and are managed by athletes. A further aspect to be considered is the possibility that priorities of the value-setters and educators for VbE and the learners (i.e., junior and elite athletes) diverge because of the socioeconomic and generation gap (Leijen et al., Citation2022) as well as differing goals (Arieli et al., Citation2020).

The potential misalignments between societal values of sport and athletes’ personal values presents a challenge to the effective implementation of the ISE because National Anti-Doping Organisations (NADOs) or other Code signatories involved in developing, implementing, and evaluating the outcomes of VbE may have different understanding and expectations about what values are important and relevant to athletes. Therefore, we question the utility of the guidance for the ISE suggesting building VbE around a locally agreed set of societal values. Instead, we argue that effective VbE should be grounded in nuanced understandings of how athletes manage and succeed in sport situations where personal values guide behaviour in different, and sometimes opposing, ways or when they are conflicted over behavioural choices to meet the situational demands whilst staying true to their personal values.

Aims

The fundamental premise of this study is that athletes may endorse values of sport in abstract and absolute form (i.e., making a statement about what values they generally hold as important), but – as it has been observed outside doping context (e.g., Connors et al., Citation2001; Howes & Gifford, Citation2009) – these values do not operate with the same intensity across different situations and contexts. For this study, we regard values as general guiding principles which are contextually defined and prioritised. With this view, we purposefully diverge from the aspect of value definitions that consider values as trans-situational goals (e.g., Schwartz, Citation2016). Instead, we draw upon the notion of value priorities (Schwartz, Citation1996) to allow for contextual interpretation of how values influence actions and behavioural choices. Congruently, value systems/structures are considered as contextually rated and prioritised value sets.

The purpose of this study, therefore, was to explore how elite athletes interpret, and make sense of, their values across different situations and times in their athletic career. Our aim was not to focus on values priorities per se (for this aspect, see Woolway et al., Citation2021), but instead explore how values are prioritised and structured to facilitate setting and achieving performance-related goals in competitive sport and remaining true to personally important values. This will inform the development of relevant values-based anti-doping education for both junior and adult athletes through an evidence-informed understanding of how personal values operate in a sport context. To achieve this aim, our study set out to answer the following research questions: (a) What are the origins of elite athletes’ values?; (b) What do values mean to elite athletes?; (c) How do values guide the lives of elite athletes?; and (d) How do elite athletes’ values change across contexts and/or time?

Methodology

The current study adopted a generic approach to qualitative inquiry due to the broad, exploratory, and differing nature of the research questions. Generic qualitative approaches are typically used when little is known about the topic being investigated and the research questions do not fit within the confines of established methodological designs (e.g., case study, phenomenology, narrative inquiry; Kahlke, Citation2014; Percy et al., Citation2015). For example, researching outward experiences but not inward experiencing per se (phenomenology’s interest; Percy et al., Citation2015). Specifically, the current study was informed by Qualitative Description (QD; Sandelowski, Citation2010). QD has been widely used within the field of sport and exercise psychology (e.g., Ori et al., Citation2022; O’Donnell et al., Citation2022) and aims to generate broad descriptive insights into a phenomenon (i.e., how participants interpret, and make sense of, their values across different situations and times of their career) with special relevance to practitioners and policymakers (Sandelowski, Citation2010). As a result, QD typically draws upon larger and more representative samples (e.g., elite athletes from different countries) compared to other qualitative approaches (Percy et al., Citation2015). However, although QD produces findings which remain closer to the data (i.e., data near) in comparison to other qualitative approaches, it remains a detailed and nuanced interpretive product (Kahlke, Citation2014; Sandelowski, Citation2010). In line with this, the current study was conducted from an interpretivist philosophical position, which is based on a relativist ontology (i.e., multiple individual realities) and a subjectivist epistemology (i.e., knowledge is constructed and subjective; Poucher et al., Citation2020).

Research context: the SMART project

The current study was conducted as part of the 3-year international “Sense-Making in Anti-doping Reasoning Training” (SMART) project, which was funded by the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The SMART project aimed to create an evidence-informed anti-doping training programme to help athletes make better ethical decisions in complex situations where universal values become fragmented in everyday applications. As such, the SMART project builds on our own underpinning research interests in promoting clean sport through prevention and education (see Petróczi et al., Citation2021) and aligns with the wider shift away from catching dopers and stopping athletes from doping to promoting clean sport values and building clean sport culture through values-based education to develop personal values and principles that aligns with clean sport values (WADA, Citation2020b). The project was a partnership between academics from Kingston University (UK), Sheffield Hallam University (UK), Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (Greece), Foro Italico University of Rome (Italy), Immanuel Kant Baltic Federal University (Russia), and Leipzig University (Germany).

Each author's contribution is outlined in the CRediT statement below. However, those involved in “formal analysis” and/or the “methodology” either had extensive experience (i.e., 20 years) of conducting anti-doping research and working with WADA, International Federations and NADOs (i.e., first author), were experienced anti-doping qualitative researchers (i.e., second, third, and fifth authors), or were a member of the UKAD Athlete Commission and WADA Social Science Research Expert Advisory Group (i.e., fifth author). The diversity within our research team, spanning different backgrounds and expertise, was beneficial during the process of recruitment, data collection, and analysis (see below). Furthermore, the UK-based authors were also all part of the Clean Sport Alliance which recognises and works with the complexity of the doping problem and prioritises collaboration and co-ordination in moving anti-doping policy and practice forward.

Participants

To address the research questions, the inclusion criteria required participants to be “competitive-elite” level athletes who regularly compete at the highest level within their sport (i.e., top divisions or leagues) or above (i.e., “successful-elite” or “world class-elite”; see Swann et al., Citation2015) and fall under WADA doping testing rules. Criterion-based purposeful sampling (Patton, Citation2014) was used to recruit an internationally representative sample which met the inclusion criteria (Kahlke, Citation2014; Sandelowski, Citation2010). In addition, to participate in one of the seven international focus groups, athletes were required to speak English. The final sample consisted of 60 elite athletes (37 male, 23 female) between 17 and 48 years of age (Mage = 26.1; SD = 7.02) (see Supplementary Material 1). Participants were from 13 different countries: Greece (n = 13), UK (n = 13), Russia (n = 9), Italy (n = 8), Germany (n = 7), Ireland (n = 2), Turkey (n = 2), Denmark (n = 1), Argentina (n = 1), Austria (n = 1), Grenada, (n = 1), Serbia (n = 1), and Spain (n = 1). At the time of data collection, the participants were either active athletes (n = 48) or had recently retired (i.e., within 4 years of one Olympic cycle) from competitive sport (n = 12). In addition, athletes represented a total of 27 different sports with Athletics being the most frequent (n = 16), followed by Soccer (n = 4), Handball, Sailing, and Weightlifting (n = 3 each). All athletes had competed at either national or international level, of which five were Olympians or Paralympians (two with medals) and 29 participated at either the European or World championships (nine with medals). Despite competing at an elite level in their sport, 25 athletes had never been tested for doping, and 23 reported no formal anti-doping education.

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the Faculty Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Science, Engineering and Computing, Kingston University (reference number: 1436). Following institutional ethical approval, two phases of data collection were conducted to facilitate international representation (i.e., national and international focus groups). Phase one involved project partners recruiting participants from their country (i.e., UK, Greece, Italy, Russia, and Germany), via personal contacts at National Anti-Doping Agencies, who met the inclusion criteria. Focus groups were chosen to stimulate interaction between athletes, explore multiple and differing experiences, and generate broad insights (Kahlke, Citation2014; Sandelowski, Citation2010; Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014). A total of six national focus groups were conducted via an online video-conferencing platform in Germany (n = 5), Italy (n = 6), UK (n = 7), Greece (n = 2 × 5), and Russia (n = 7). Each focus group was conducted in the native languages by one of the named authors and lasted between 63 and 120 min (M = 94.33, SD = 19.04). Following this, phase two involved seven online (via a secure video-conferencing platform) international focus groups (n = 25). These focus groups were conducted in English by the third and fifth authors and lasted between 84 and 109 min (Mlength = 94.29, SD = 9.52). All audio recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim and translated into English (where applicable).

Data collection

Pre-focus group tasks

Pre-focus group tasks were used as an “elicitation tool” (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2014) to encourage participants to reflect on their values before participating in a focus group. To help guide their reflections, participants were asked to broadly consider values as universal guiding principles that influence behaviour and were given examples from Schwartz’s (Citation2016) value taxonomy. Following this, participants were asked to consider how their values may have changed over time and subsequently rank their most important values across each developmental stage (e.g., childhood, adolescence, emerging adulthood, and adulthood) in order of importance (1 = Most important, 5 = Least Important; See Supplementary Material 2).

Focus group guide

In line with the principles of QD (Kahlke, Citation2014; Sandelowski, Citation2010), a semi-structured focus group guide was developed by the researchers to explore how athletes interpret, and make sense of, their values across different situations and times. Specifically, the focus group guide was divided into three main sections. Section one explored participants’ values as a person and athlete as well as where these values come from (e.g., parents, teachers, coaches, religious beliefs, society, culture). Sections two and three examined how values may change over time and if values change in sporting situations respectively (e.g., in what sporting situations do you actively think about your values?).

Data analysis

Consistent with our interpretive philosophical position, data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) to identify patterns of meaning (i.e., how athletes interpret, and make sense of, their values across different situations and times) across the dataset (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Braun and Clarke (Citation2021) have highlighted that RTA with a descriptive purpose is still an interpretative activity undertaken by a researcher. In addition, the flexibility of RTA means it can be used to analyse large datasets (Clarke & Braun, Citation2017). The six phases of (reflexive) thematic analysis were used flexibly by the second author to guide the analysis and facilitate rigorous data integration. Whilst we present these steps sequentially below, analysis involved constant moving back and forward between different phases. First, transcripts were read, and then re-read to promote content familiarity and initial thoughts, ideas, interests, and interpretations in relation to the research questions were recorded via written notes. Second, to remain data near, data were inductively coded based on the research questions using NVivo 20. For example, scenario-specific experiences constructed by participants in the latter parts of the focus group were considered relative to early statements they had made about the values they hold, hence when analysing the data, the second author also interpreted how well a participant’s scenario-based behaviour adhered to these earlier cited and context-free values (see “value conflict and management”). This gave rise to interpretations regarding value change or value conflict. Third, coded data were organised and (initial) themes were generated. This process included clustering different codes together to create themes (e.g., “value consciousness and clarity”) and subthemes (e.g., “the (misunderstood) meaning of a value”; see Supplementary Material 3). Fourth, themes were reviewed based on whether they formed a coherent pattern across the whole dataset, and whether there was coherence between the theme and the coded extracts. At this point, members of the research team also acted as “critical friends” by providing a mixture of subject (first author), analytical (third author), and experiential knowledge (fifth author) to challenge and help further refine the second author’s interpretations (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). Fifth, the focus of each theme was refined and theme definitions were subsequently generated (see Supplementary Material 3). Lastly, appropriate extracts (i.e., quotes) were selected, combined with the analytic narrative and written up.

Quality criteria

The current study should be judged using a “relativist” approach (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2009), which involves formulating a list of characteristics for the unique purpose of the study (i.e., how elite athletes interpret, and make sense of, their values across different situations, contexts and times of their athletic career for the benefit of WADA’s mandatory VbE) and methodological approach used (i.e., QD; Sandelowski, Citation2010). The following criteria, therefore, can be used as a starting point to judge the current study: First, the worthiness of the topic was demonstrated within the introduction by highlighting how values-based education has become a mandatory element of anti-doping education. As such, there is a pressing need for research to understand how athletes interpret, and make sense of, their values across different situations and time. Second, rigour was achieved through the recruitment of a wide range of elite athletes, who engaged in in-depth national and international focus groups and produced rich qualitative data. The first, third, and fifth authors also provided feedback and reflections from differing perspectives on the data throughout the analytical process (i.e., “critical friend”; Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). Finally, methodological coherence is evidenced through the open reporting of our philosophical position (i.e., interpretivism), design (i.e., QD), data collection methods (i.e., focus groups), data analysis (i.e., RTA) and use of a “relativist” approach for judging quality.

Results

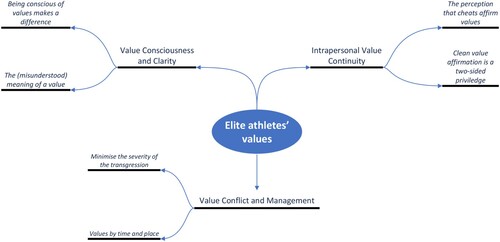

The themes generated from the data centred around athletes’ values in relation to their life, athletic career, performance and performance enhancement, and success. These are illustrated in three main themes: (1) value consciousness and clarity, (2) intrapersonal value continuity, and (3) value conflict and management (). Reflections on doping, other forms of cheating and just “clever play” interspersed all three themes.

Value consciousness and clarity

The way and degree to which athletes think about their values has implications for their behaviour in the context of sport. Whilst athletes offered multiple understandings of what their values were, having a high level of value consciousness and clarity was construed as protective against cheating.

Being conscious of values makes a difference

Having value consciousness was linked to having a greater understanding of what one’s values were and being able to act in accordance with such values. Value consciousness and clarity were construed as a disposition that came with age and maturity; as illustrated in the quote below:

I think the part that has changed the most is how much I think about it and how aware I am of what my values actually are. I think when I was younger, I would still be the same person but I wouldn’t think that I act because of my values, my values would just be more hidden … I had never put them into words when I was a kid … I have learnt to know my values as well … I have then started to be more strong in the knowledge of my own values … I think the thing that has changed the most is how big my focus on my values is. (Athlete 49)

Whereas family members, peers, and teachers were commonly cited as sources of values during their early childhood years, the coach was identified as a more prevalent and persistent source of values and of value consciousness and clarity. As such, interactions with the coach would not only signal values that the athletes should hold, but coaches could also directly or indirectly prompt athletes to be reflective and contemplate what their values were. Additional interpersonal events that prompted value consciousness included encountering individuals that did not match their values (e.g., training and competing in foreign countries), losing to an opponent who was perceived as cheating, and being confronted by opportunities to cheat (e.g., substance use). Participants also spoke of personal events or moments that prompted them to contemplate their values, and seldom were these “positive” happenings. Indeed, poor form, injury, and self-doubt, were identified as challenging moments that made them think about their values.

Low value consciousness (i.e., not thinking about their values) was evident, with some participants announcing that the focus group process was the first time they had reflected on what their values might be. Participants acknowledged that there were, or could be, times in an athlete’s life when they purposefully, or inadvertently did not think about their values. Not being conscious of one’s values was a meaning embedded into participants’ explanations as to why someone would act in ways that went against their values. Athletes were sometimes portrayed as having the ability to mentally switch-off from, set-aside or forget their values. For example, one participant said, “when you are in the ring you’re just like okay, and the lights are on and you just forget about the core values, (they) aren’t there because it’s the go time” (Athlete 42). These participants argued that not thinking about values was key to doping. This meant that dopers do not necessarily have a different set of values compared to clean athletes. Instead, dopers could be individuals who through conscious control or automatic self-deception do not bring their moral values to the forefront of their mind in the moments prior to a value transgression, or contextually have other value priorities such as self-enhancement, safety and security, or providing for self and family.

The (misunderstood) meaning of a value

Athletes differed in how they made sense of what a value was and how well they verbalised their values. As such, this theme incorporates evidence of both incorrect and correct understandings of a value, with the aim of illustrating the various comprehensions that athletes have regarding the concept of a value. Some participants interpreted the concept of a value by labelling or describing their personal characteristics (e.g., traits, psychological states, attitudes, goals, and life priorities). For most participants, it took time to think about their personality characteristics to identify their values. Several participants claimed that goals were responsible for the values that an athlete held, while others suggested that their goals were an extension of, and thus stemmed from their values. Not all participants made these links, and thus conveyed values and these other personal characteristics as interchangeable. However, other participants did give verbalisations of their values that aligned with an understanding of values as guiding principles that influence their behaviour. Indeed, values were understood and construed by many as behavioural guides, placing limits on or giving direction to how they should or should not respond to a current or future situation. Perceiving values in this way is illustrated in the following quotation in which a participant talks about the way a value (“respect”) guided their interaction with a suspected doper:

We know about the doping situation from the media, but for me, it was always about respect, this is a big value in this example, which is important to me. So the Russians were at this event, but they were not competing. There were a lot of nations that didn’t greet the Russian athletes and that’s the thing which I say, “okay, I don’t know anything so … why should I not be respectful to them, and say hello and how are you?” (Athlete 55)

The problem with sport is that you want to win … your values help you in deciding which weapons you can use against the other, honest weapons like your ability and your will and your power or something else [participant infers substance use] and that depends on your values (Athlete 36).

Intrapersonal value continuity

A second theme was the experience of intrapersonal value continuity, whereby participants considered what it looks like and what it takes for an athlete to act in a manner that was coherent and consistent with their values. An underlying premise of this theme was the experience of a single coherent self, with a single set of holistic (and somewhat abstract) values that were shared openly and said to consistently guide them over time and across contexts (i.e., inside and outside of sport). Both cheating- and clean sport situations affirmed athletes’ values, albeit in different ways as detailed in the following two subthemes.

The perception that cheats affirm values

A distinct way in which value continuity was represented in the data was in relation to discussions about athletes who cheat. This subtheme refers to the perception that some athletes who cheat do not experience mental anguish because they are in fact acting in harmony with their values. A key aspect of this theme was the perception that cheating affirms egoistic values, whereby cheats were typically conveyed as exclusively guided by the values of normative success, prestige, and wealth, hence participants suspected that cheating (and more specifically doping) was a pathway to value fulfilment for such athletes. This can be interpreted in the following hypothetical example offered by one participant:

If I am an athlete who dopes to improve my performance, to be more successful, then, for me, of course, the value that I am successful, that maybe I will have more prestige, that I will earn more money, these will, of course, then take a central role. (Athlete 3)

Other participants believed that some athletes cheat to make it fair, whereby an athlete develops the perception that cheating becomes a way to create a level playing field because they believe that their opponents are also engaging in practices and methods that are outside of the rules. Similarly, there was also a perception that, for some athletes, the pursuit and attainment of normative success led to prestige and wealth which in turn enabled them to take care of and provide for their family with these latter points being representative of values. Hence cheating could be construed as egoistic altruism whereby normative success, prestige and wealth were egoistic means to an altruistic end. This enabled the participants to consider the possibility that dopers could be athletes with prosocial values, and that the enactment of illegal performance enhancement could be construed as value fulfilment. As one participant concluded when theorising about athletes who cheat: “It’s simply about how I can position myself and maybe make things for myself and for my family a little better” (Athlete 4).

Clean value affirmation is a two-sided privilege

Athletes spoke about the two-sided nature of their value-affirming activities, hence, there were two sets of thoughts that enabled athletes to stay true to and behave in ways that were entirely authentic to their values. However, these thoughts were essentially made possible by a privileged socioeconomic status whereby athletes had access to education and alternative careers outside sport, doing sports for love, not as a means to a better life. One prominent way to affirm one’s values (i.e., one side of clean value affirmation) was to connect with the pain of a value transgression, whereby the athlete was able to frame engaging in behaviours that went against their values as a highly unpleasant experience. Indeed, athletes were clear that they would experience great mental anguish (e.g., shame) if they were to engage in behaviours that could be categorised as cheating or even bending the rules. Participants also reflected on the pain of being on the receiving end of opponents’ behaviours that were not in the spirit of the game or that were categorised as outright cheating. Consequently, athletes vowed to themselves that they would not engage in such behaviour. For example, an open water swimmer recalled the harm done to them by another athlete’s behaviour during an Olympic final:

In the Olympics on the last stretch in the 100 m and I was in the lead and this guy pulled my leg and I lost [the] first place by him pulling my leg, I couldn’t do anything about that but I would never do it to anybody … I knew I was going to win it and somebody does something so unfair to you, for me that was a big lesson I would never do anything to anybody and how can he do that to me but you know everybody has not got the same values. (Athlete 41)

I am [a] goal keeper and when I touch the ball and it goes behind the goal post the ball is for our team, if a defender touches the ball and it goes behind the goal post it’s for the opponent team … I didn’t touch the ball but the referee said I touched the ball so the ball was for us, but I admit[ed to the referee] that I didn’t touch the ball and it was not for us … I think that in our mind we have that we have to be … the values it's important and by telling the referee that I didn’t touch the ball I feel good, I am with the values. (Athlete 37)

Value conflict and management

When faced with a particular situation or scenario, a conflict between values could occur whereby different values guide their behaviour in different and sometimes opposing ways. Similarly, the behaviour needed to meet the situational demands meant that some values were incompatible, hence athletes had to find ways of managing this dilemma to reduce feelings of dissonance.

Minimise the severity of the transgression

Athletes were able to construe things in a way that minimised the severity of what could otherwise be viewed as a value transgression. One way that athletes minimised the severity of the value transgression was by emphasising that they were in some shape or form still behaving by the rules, be that the sport’s national governing body or the WADA code (WADA, Citation2021a). Hence, athletes turned to the official rule books to help make their behaviour more permissible. This is illustrated by a participant when justifying an experience:

I’ve got a peanut allergy and I was on holiday in France and I went into anaphylactic shock … and when I got to hospital they put a steroid in my arm and some steroids in my mouth … I was running for GB the week after so I had to call UK Anti-Doping and go “look this is what happened, all this has went into my body but can I run next week or what?” and they said yeah just follow these steps and apply for an emergency TUE … so I just followed that code. (Athlete 9)

On other occasions, participants highlighted or inferred that their behaviour was in fact a routine and accepted aspect of competitive sport thereby implying that they were still within the rules or that they were keeping within the unwritten rules of the game. For instance, “time wasting”, “feigning injury”, and “fouling an opponent” were simply considered as ways of stretching (but not breaking) the rules. This approach to lessening the severity of the behaviour was bolstered by the recollection that an official (e.g., umpire) had not called them out for any wrongdoing and therefore their behaviour could be assumed as permissible. Similarly, several participants would circumvent accusations of value transgressions by referring to authoritative others who had instructed their behaviour, thereby diminishing the athlete’s sense of autonomy over the behaviour they had enacted. When participants tried to explain why athletes who share their values dope, diminished behavioural autonomy was a recurrent justification.

The severity of the value transgression could also be minimised by drawing attention to one’s infrequent or context-bound engagement in the behaviour, thus inferring an occurrence-threshold to qualify that a value transgression had taken place. Hence, the athlete was coherent with their values enough of the time that they did not feel threatened by those occasions when they transgressed their values. As one athlete said:

I have been respectful, and I have been doing my part contributing to sportsmanship and I have been staying true to myself again over these three months up to this moment of fifteen minutes it’s time to shine so that time, my core value, I put aside and this is my time to win. (Athlete 42)

[Dopers] are honest but they are honest about parts of their life, so you can be, you can have absolute integrity when it comes to your academic work, you know, being a good citizen, being out there, helping people who are less fortunate than you, and you just have this one area where you are not quite toeing the line so I would say there is a lot of that going on that people would say actually, I’m actually fundamentally a good person. (Athlete 52)

Several additional examples of athletes minimising the severity of the value transgression clustered around the more abstract idea of value-sacrifice for good reason. This meaning represents the tendency to construe the value transgression as justifiable because it was instrumental to another end; an end that was perceived as more important in that moment in comparison to value fulfilment. For many participants when trying to explain why athletes who share their values eventually cheat and dope, value-sacrifice for good reason was a prominent meaning, often enveloped in identity issues as well as a need for certainty over their future. Essentially, doping was an undesirable last resort to hold on to their athletic existence that brought with it several benefits.

As part of the various accounts where athletes had sacrificed their values for good reason, there was an equivalent inference that the athlete was prioritising something over one’s values. More specifically, there was often a particular ultimatum characterising such experiences; the athlete either had to behave in ways that fulfilled their values or that increased their chances of success. Importantly, this meant that normative success (i.e., winning) was not conceptualised as a value. Intuitively, the greater the importance of the performance-related goal (i.e., high-stakes performance), the greater the sense that one would be sacrificing their values for good reason. Finally, accounts that the athlete had sacrificed their values for good reason could also be characterised by explicitly devaluing value fulfilment, thereby alluding to the setbacks and decrements that would be incurred if one was to stay true to one’s values. For some, this took the form of clean values getting in the way of a good time and an exhilarating experience (e.g., following the rules made things boring) whereas, for others, the negative aspect of value fulfilment was experienced at a deeper level (e.g., missing out on athletic career progression).

Values by time and place

When making sense of their behavioural responses to specific past or future sport scenarios, the contextually bound nature of one’s values was a prominent meaning and resulted in claims that certain values become more or less important as a function of time and place. The time-bound nature of one’s values accounted for the way that one’s values were experienced to change over the course of one’s life. Here, participants argued that they had held different sets of values at different points in their life, with age and/or level of maturity and/or career status being drawn upon to create such temporal boundaries around values. The possibility of one’s values being bound by time meant that past cheating behaviour was untroubling because it simply represented a different younger self who, at the time, held a different set of values. As one participant stated:

I also have to say that in my early twenties, I had allergic asthma and I thought it would be cool to see how this asthma spray would work to boost my performance during summer training. Yeah, I did that. And it did help some. But, yeah, thinking back, I wouldn’t do it again and, in that moment, it was in line with my values [high performance]. Looking back, I would no longer choose that. (Athlete 2)

Some participants’ comments were also construed as inferences of simultaneous value systems, thus the possibility that they currently had multiple sets of values, with each set of values assigned to or even dictated by a particular context. Some athletes recognised differences in themselves when considering their values as a person outside of sport and another set of values as an athlete. While there could be overlap in the values that characterised their non-sport and sporting selves, there were enough differences to justify a feeling of activating one value system while simultaneously deactivating another value system depending on the context. The following example provides an illustration of this meaning:

They [values as a person / athlete] are not very different, but I am a different person when it comes to being in the ring … when I am in the ring I am completely focused. I am there to complete a task and I look at it like I have to win … so that is like my life is depending on it so I fight very hard, it’s quite different, you will see on volume levels, me being a person [compared] to an athlete it is a little different yes, it’s more aggressive. (Athlete 48)

[T]hat (value of winning) totally makes sense when I’m an athlete but that’s something that suddenly doesn’t make that much sense when the competition is over and I am talking to the very same person in another context. Suddenly I would like to understand the person. (Athlete 40)

Importantly, the experience of such multiple value systems enabled these participants to argue that they did not experience a value transgression because in that moment they were indeed behaving in accordance with their sporting self and the corresponding value system.

Another common formulation of values by time and place was to speak of value priorities. Not all values were held with equal regard, thus values could be described, compared, and contrasted not only according to the content of the value but also the ranking of a value. Discussions about the way their values had changed over time produced arguments from participants that it was not their values per se that had changed, but the position of that value relative to other values they held, thereby implying the possibility of a dynamic value hierarchy. Indeed, participants distinguish values according to those that were deemed “core”, “basic”, “essential”, “fundamental”, “central”, and “main”. Moreover, when tasked with making sense of their actual or possible behavioural responses to specific sport scenarios relative to the values they held, participants spoke of prioritising some values over others to enable them to meet the demands of the situation. Cheats and dopers were construed as individuals whose value priorities were routinely dictated by demands of the situation rather than the costs of the value transgression or the value of value fulfilment. Repeatedly prioritising or deprioritising values in this manner (i.e., ordering one’s values based on the extent to which the value helped them meet the demands of the situation) ultimately resulted in a change to the overall content of one’s value system. As explained by one participant:

If you had all of your priorities [values] laid out in front of you on a set of dials and you turn your honesty dial down to 1%, can you really claim that honesty is one of your values? … if you turn them down all the way, if you imagine them like dimmer switches, if you turn them down all the way, are they still there? And I personally, don’t think they do, I think values are either embodied to a higher degree or they might as well not be there. (Athlete 56)

Discussion

The current study examined how elite athletes interpret, and make sense of, their values across different situations, contexts and times of their athletic career to inform WADA’s mandatory VbE. Whilst the themes that we generated convey the views and experiences shared among the athletes from different cultural, socioeconomic, and sport contexts, the analysis also interpreted intriguing contradictions and highly polarised views not explored in previous research on the spirit of sport values (Mortimer et al., Citation2021; Kavussanu et al., Citation2022).

Placing the results from this study, being the first of its kind, into a directly relevant literature context has very limited scope. Investigations to date into athlete’s values and decision-making typically took a snapshot of athletes’ value preferences and decisions at the moment of time using survey methodology in general (e.g., Lee et al., Citation2008) or in connection with anti-doping (Mazanov et al., Citation2019; Mortimer et al., Citation2021; Kavussanu et al., Citation2022; Woolway et al., Citation2021). Interviews with competitive athletes touch upon values as protective factors (e.g., Clancy et al., Citation2022; Erickson et al., Citation2015; Hoppen & Šukys, Citation2023; Petróczi et al., Citation2021) but these also fall short on capturing the dynamics of personal values in a decision-making context. From our study, it has become apparent that the ways values operate in athletes’ decisions are not only complex but also flexible and dynamic, which creates a state of vulnerability that is both personal and capricious, and likely to be influenced by personality traits to a large degree (Parks-Leduc et al., Citation2015).

What is a “value”?

For many athletes, values were synonymous (or implied via the labelling) with personality traits, psychological states, attitudes, motives, goals, and life priorities. The lack of clarity some athletes demonstrated about their understanding of values mirrors the observation in the literature that values are frequently conflated with attitudes, traits, norms, and needs (see Hitlin & Piliavin, Citation2004). Meaningful VbE must therefore acknowledge and work with this ambiguity via sense-making (Park, Citation2010). Conceptual literacy (i.e., accurately differentiating between values and desired personality traits, psychological states, attitudes, motives, goals, or life priorities) is, first and foremost, required from those researching, planning, delivering and evaluating values-linked educational programmes. This is not to decide what is the right meaning of a value, but to be clear on what view they adopt and, more importantly, to be consistent to this conceptualisation throughout all values-linked activities (i.e., in learning objectives, exercises, as well as in the evaluation of the effectiveness of the planned and delivered education). At the minimum, practitioners responsible for VbE in anti-doping should be cognisant of the differences and interactions between personal and societal value priorities in sport, performance, and performance enhancements.

Our results suggest the best way to understand values at an individual level is through the goals or motivation that the value represents (Kegelaers et al., Citation2018; Overbye et al., Citation2013), which is in line with Schwartz’s (Citation2016) theory of basic values. Values are a key motivational basis for decision-making and behavioural choices applied to a sport context where both inter- and intrapersonal value conflicts are frequent (Bardi & Schwartz, Citation2013). It has also become apparent that although intrapersonal value conflicts can happen in many sport contexts, the solutions to these conflicts are situation dependent, where in-the-moment understandings of the consequences of following or not following one’s ideal value priorities is an important factor. This finding resonates with the work by Parks and Guay (Citation2009) that links values and personality to goal accomplishments in a nuanced way. Distinguishing between goal content (what) and goal striving (how) allows for discerning the role of values in decision-making.

Sources and malleability of athletes’ values

The degree to which athletes think about their values has implications for their behaviour in sport. Value consciousness, and therefore clarity, was construed as a disposition that came with age and maturity. Athletes in this study referred to family members, peers, teachers, and coaches as value sources in athletes’ formative years, and beyond. This is in line with parental and early childhood influence on values and aspirations (e.g., Gavriel-Fried & Shilo, Citation2016; Hitlin, Citation2006). It is further supported by previous studies exploring the meaning of “clean sport” for athletes (Petróczi et al., Citation2021; Shelley et al., Citation2021). However, the current study shows that athletes are not passive recipients of the values held by their environment but actively make these their own by favouring certain values over others, and actively managing their value priorities according to their situational demands and decisional needs. Similar value-priority management has been observed outside sport context, for example for food choices (Connors et al., Citation2001), environmental issues (Howes & Gifford, Citation2009), social work (Valutis et al., Citation2014), and work-family balance (Cohen, Citation2009).

Athletes’ values also appeared to be stable cognitive representations, but their value priorities were temporary and contextual. Most research on values assumes that values are relatively stable after being shaped in early childhood through late adolescence (Hitlin & Piliavin, Citation2004). Athletes in this study certainly referred to their values being shaped by their upbringing, early socialisation in school and sport, and their culture. However, whilst values transcend situations, value priorities were considered situation-specific. Thus, value priorities change over time with maturity, learning and life experiences, as well as from one situation to the next (e.g., Connors et al., Citation2001; Howes & Gifford, Citation2009).

The observation we made about athletes having multiple sets of values is in line with Howes and Gifford’s (Citation2009) results, which showed that value judgments can change across situations depending on the context and pre-existing value endorsement level. The study also found that people may hold “sacred” or “protected” values, which cannot be traded off for other values. This is similar to the athletes’ claim that they have different values in different contexts and prioritise some values over others to meet the demands of the situation. Further research is needed to understand the nature and extent of value conflicts in various scenarios, which can help in developing effective anti-doping policies through VbE.

One theoretical framework that may be applicable to value prioritisation is the combined “social identity approach” (Hornsey, Citation2008), which encompasses the Social Identity Theory (SIT, Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) and the Self-Categorisation Theory (SCT, Turner et al., Citation1987). Whilst the former (i.e., SIT) is important to understand how individuals, and young individuals, derive a sense of identity and self-esteem from the groups they belong to, and that their behaviour is influenced by their desire to maintain a positive image of the group (Horn, Citation2003), the latter (i.e., SCT) sees identity operating at different levels – human, social, and personal – with different levels of inclusiveness. These theories can be applied to pertinent aspects of the results in two ways: Firstly, SCT assumes a “trade-off” between the identity levels and posits that with one level turning more salient, the other levels become less salient. Secondly, the observation that self-categorising is the function of accessibility at the given moment. Some identity categories are constantly or at least frequently accessible (i.e., athlete identity) whereas others are temporal, or they are only awakened in a specific situation (i.e., rule-breaker, or fair player, identity). In the context of sports, athletes may prioritise values that are important to their team or sport culture to maintain their status as a valued member of the group. Additionally, athletes may prioritise values that are important to their identity as an athlete, such as competitiveness or achievement to maintain their self-esteem and sense of identity. This prioritisation may vary depending on the situation and the salience of different group or personal identities, and career stages (Ronkainen et al., Citation2015). Although in this study we did not specifically explore the link between athletes’ social or personal identity (Clancy et al., Citation2022), there are indications in the data suggesting that self-categorisation as athletes (i.e., athletic identity) and as private individuals is an ongoing process and the contextually assumed identity is used to explain shifting value priorities in the recalled examples. Although we did not explore the origins of values linked to social identity as an athlete, research that takes a social identity approach to understanding coach leadership indicates that coaches are key sources/mediators of social identity (see Stevens et al., Citation2021). Indeed, participants in our study frequently cited and recalled the coach as a distinct source of values. Hence, it may be that the coach is central to communicating the value parameters of the athlete’s sport-based social identity. Future research is warranted to explore values within SIT further with bespoke research questions because it could be instrumental for ecologically valid values-based anti-doping education initiatives.

Furthermore, values that motivate excellence in sport, and in some instances may lead to cheating, could be related to certain personality dimensions such as the so-called “dark triad”, especially narcissistic personality traits (e.g., Nicholls et al., Citation2020) and self- and socially-oriented perfectionism (e.g., Madigan et al., Citation2020). These aspects should be further explored to better identify athletes at risk of doping and other forms of cheating in sport and for athlete-centred anti-doping interventions.

Value conflicts, value consciousness, and management

Multiple values exist; therefore, accountability and compromise are necessary to resolve potential conflicts between one’s values (Schwartz, Citation2016). Among our participants, athletes faced conflicts between meeting situational demands and fulfilling their values. Athletes manage internal value conflicts by compartmentalising, temporarily shifting value priorities, and/or suppressing value consciousness. Although Connors et al. (Citation2001) focused on eating situations, their findings on categorising and prioritising conflicting values are like the dominant internal value conflict management strategies found in our study with athletes.

Additionally, the current study highlights the importance of interpersonal coherence in allowing individuals to affirm their values, while also acknowledging the need for tolerance towards conflicting values in their environment, or even within themselves. Previously, survey-based studies have shown that doping as a behavioural choice is influenced by the moral values of sport (Mortimer et al., Citation2021) but its likelihood is positively correlated with a set of universal values linked to self-enhancement (Kavussanu et al., Citation2022). Athletes in the current study offered examples of situations where they experienced conflicting values within sport, or between their value priorities as an athlete and in their private lives and spoke of ways they managed these conflicts. They made necessary comparisons of different frames to select the one that “made the most sense” through the five key sense-making processes of framing, emotional regulation, forecasting, self-reflection, and information integration (Park, Citation2010). Engaging with ambiguous or rule-breaking performance-enhancing behaviours was sometimes construed as a moment of inadvertent or purposeful thoughtlessness about one’s values. Yet, these behaviours could be enacted in the presence of conscious sense-making activities that reframe the behaviour as value coherent or that reduce the severity of a value transgression. These findings collectively underscore Hauw’s (Citation2013) position that doping (and doping avoidance) can only be understood as a situated activity, thus sense-making/situational awareness processes are critically important to the future of VbE.

Practical recommendations

The Guidelines for the ISE (WADA, Citation2020a) recommend that VbE should be included at every level along the athlete pathway, and education activities for each stage are to build on one another to reinforce the (same and desirable set of) values throughout an athlete’s career. The latter assumes that there is a collectively agreed set of values that could be demonstrated in VbE at all levels. The results of the present study suggest that this is an impossible goal. Participants demonstrated a great deal of individuality and flexibility in their value priorities. In the absence of ready-made, ideal value sets that can be internalised and adopted, VbE activities should enable athletes to think critically about their own values and value priorities. Through a sense-making process, athletes can identify their values and value priorities, understand where these values and priorities came from, and reflect on how they have changed over time and across situations. This is in line with Sipavičiūtė et al.’s (Citation2020) recent review suggesting that anti-doping education programmes targeting belief systems and fostering critical thinking are more effective. The ISE Guidelines (WADA, Citation2020a), recommending activities to have participants think critically about and reflect on the values deemed important by the organisation delivering VbE has limited utility if these critical thinking exercises are not placed in situational contexts athletes have and will likely experience. Applying this greater level of understanding and self-awareness to specific hypothetical situations, which deliberately challenges personal value sets and priorities would allow athletes to anticipate the pain of a value transgression and experience the value of value fulfilment in a safe and consequence-free environment.

Values-education, with a discussion about the importance of values and values of sport (e.g., Barkoukis & Elbe, Citation2021), is not sufficient. Developing athletes’ abilities to make sense of their values, motivations, motives, and goals, and to be capable of anticipating the pain of a value transgression and the value of value fulfilment are the key ingredients of VbE, not an agreed set of values all athletes are expected to subscribe to. To facilitate this, anti-doping education must incorporate expertly led activities that create space and time for discussion, challenge athletes’ values priorities, decisions, and justifications in carefully crafted scenarios, and lead to developing sense-making skills in the process. Organisations responsible for anti-doping education, and VbE within, should be aware of the potential negative consequences for and vulnerabilities of athletes if – due to personal circumstances, socioeconomic, and socioecological factors – they face discrepancies between what they do, can do, strive to do, and are expected to do. How these factors can be mitigated against is beyond the scope of our study, and indeed beyond what values can add to protecting athletes from these risks, but there are multiple avenues for values-based anti-doping education to contribute to addressing athlete vulnerability. One is through upskilling athletes for meaningful meaning-making process for better management of the inevitable internal and external value conflicts (Park, Citation2010). Another way is to encourage athletes through targeted exercises, case studies and guided discussions to consider the future consequences of current decisions in the context of their value priorities (e.g., anticipated regret, guilt and shame, e.g., Kavussanu et al., Citation2022). The common characteristic of these approaches is placing the individual athlete in the centre and working with athletes’ existing values and value priorities for a desired educational outcome (e.g., adopting, internalising or strengthening the spirit of sport values to foster anti-doping compliance, clean sport behaviour and to prevent intentional doping).

Limitations and future directions

The current findings should be considered in light of several limitations. Firstly, recruiting athletes who were not only keen to take part but were also comfortable with doing the focus group discussion in English was a challenging task. Future investigations should take this study further and expand the sample geographically and culturally, which would also allow for cross-cultural explorations. Secondly, at the time of the focus group interviews, participating athletes were anti-doping rule compliant but not without experience with doping in their environment. Although anti-doping education assumes that all athletes are vulnerable and thus targets all athletes (with the majority being rule-abiding clean athlete), exploring the values and value priorities of those who wilfully committed anti-doping rule violations will make a vital contribution to the understanding of how values are operationalised in doping-related decisions. Finally, examining the link between the ideal self, personality traits (e.g., dark triad, self-, and socially-oriented perfectionism) and values, as well as the relationships between athletes’ values, goals, and behaviour presents an interesting and worthwhile avenue for further research. With such insights, VbE can better speak to and help athletes navigate and manage the conflicts and sacrifices made to remain clean.

Conclusion

Meaningful and successful values-based anti-doping education requires carefully devised and age-appropriate activities that facilitate the internalisation of the spirit of sport values. Examining the way athletes think about their values and what place sport has in athletes’ lives is key to understanding athletes’ behaviour in the context of sport and performance enhancement. The way athletes intuitively and consciously manage their value conflicts also manifests in different strategies but with a unified aim: reduce or eliminate tensions between situational demands and fulfilling personal values. Talking about the importance of values, and values of sport is not sufficient. Taking values as guiding principles in life and in sport, anti-doping education must incorporate activities that facilitate conceptually sound conversations and provide athletes with time and opportunities to unpack the behavioural meaning of their values.

CRediT Statement

Andrea Petróczi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft, review & editing. Laura Martinelli: Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Writing - original draft, review & editing. Annalena Veltmaat: Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing; Sam Thrower: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing - original draft, review & editing. Andrew Heyes: Investigation, Validation, Writing - review & editing; Vassilis Barkoukis: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Dmitry Bondarev: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Anne-Marie Elbe: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Luca Mallia: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Arnaldo Zelli: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (598 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altukhov, S., & Nauright, J. (2018). The new sporting cold war: Implications of the Russian doping allegations for international relations and sport. Sport in Society, 21(8), 1120–1136. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1442194

- Arieli, S., Sagiv, L., & Roccas, S. (2020). Values at work: The impact of personal values in organisations. Applied Psychology, 69(2), 230–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12181

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1). Prentice Hall.

- Bardi, A., & Schwartz, S. H. (2013). How does the value structure underlie value conflict? To win fairly or to win at all costs? A conceptual framework for value-change interventions in sport. In J. Whitehead, H. Telfer, & J. Lambert (Eds.), Values in youth sport and physical education (pp. 137–151). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Barkoukis, V., Brooke, L., Ntoumanis, N., Smith, B., & Gucciardi, D. F. (2019). The role of the athletes’ entourage on attitudes to doping. Journal of Sports Sciences, 37(21), 2483–2491. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2019.1643648

- Barkoukis, V., & Elbe, A. M. (2021). Moral behavior and doping. In E. Filho & I. Basevitch (Eds.), Sport, exercise, and performance psychology. Research directions to advance the field (pp. 308–322). Oxford University Press.

- Blank, C., & Petróczi, A. (2023). From learning to leading: Making and evaluating the impact of anti-doping education with a competency approach. Societal Impacts, 1–2(1–2), 100010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socimp.2023.100010

- Boer, D., & Boehnke, K. (2016). What are values? Where do they come from? A developmental perspective. In T. Brosch & D. Sander (Eds.), Handbook of value: Perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology, and sociology (pp. 129–151). Oxford University Press.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Clancy, S., Owusu-Sekyere, F., Shelley, J., Veltmaat, A., De Maria, A., & Petróczi, A. (2022). The role of personal commitment to integrity in clean sport and anti-doping. Performance Enhancement & Health, 10(4), 100232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peh.2022.100232

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1262613

- Cohen, A. (2009). Individual values and the work/family interface: An examination of high-tech employees in Israel. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 24(8), 814–832. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940910996815

- Connors, M., Bisogni, C. A., Sobal, J., & Devine, C. M. (2001). Managing values in personal food systems. Appetite, 36(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1006/appe.2001.0400

- Erickson, K., McKenna, J., & Backhouse, S. H. (2015). A qualitative analysis of the factors that protect athletes against doping in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 16, 149–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.03.007

- Erickson, K., Patterson, L. B., & Backhouse, S. H. (2019). “The process isn’t a case of report it and stop”: athletes’ lived experience of whistleblowing on doping in sport. Sport Management Review, 22(5), 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.12.001

- Gavriel-Fried, B., & Shilo, G. (2016). Defining the family: The role of personal values and personal acquaintance. Journal of Family Studies, 22(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2015.1020991

- Hardwick, B., Madigan, D. J., Hill, A. P., Kumar, S., & Chan, D. K. (2022). Perfectionism and attitudes towards doping in athletes: The mediating role of achievement goal orientations. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 20(3), 743–756. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2021.1891124

- Hauw, D. (2013). Toward a situated and dynamic understanding of doping behaviors. In J. Tolleneer, S. Sterckx, & P. Bonte (Eds.), Athletic enhancement, human nature and ethics. International library of ethics, law, and the new medicine, 52 (pp. 291–235). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-5101-9_12.

- Hitlin, S. (2006). Parental influences on children's values and aspirations: Bridging two theories of social class and socialization. Sociological Perspectives, 49(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1525/sop.2006.49.1.25

- Hitlin, S., & Piliavin, J. A. (2004). Values: Reviving a dormant concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 30(1), 359–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110640

- Hoppen, B., & Šukys, S. (2023). A qualitative investigation of athletes’ views on clean sport. Baltic Journal of Sport and Health Sciences, 3(130), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.33607/bjshs.v3i130.1402

- Horn, S. S. (2003). Adolescents’ reasoning about exclusion from social groups. Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.71

- Hornsey, M. J. (2008). Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: A historical review. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00066.x

- Howes, Y., & Gifford, R. (2009). Stable or dynamic value importance?: The interaction between value endorsement level and situational differences on decision-making in environmental issues. Environment and Behavior, 41(4), 549–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916508318146

- Kahlke, R. M. (2014). Generic qualitative approaches: Pitfalls and benefits of methodological mixology. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 13(1), 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691401300

- Kavussanu, M., Barkoukis, V., Hurst, P., Yukhymenko-Lescroart, M., Skoufa, L., Chirico, A., Lucidi, F., & Ring, C. (2022). A psychological intervention reduces doping likelihood in British and Greek athletes: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 61, 102099. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.102099

- Kegelaers, J., Wylleman, P., De Brandt, K., Van Rossem, N., & Rosier, N. (2018). Incentives and deterrents for drug-taking behaviour in elite sports: A holistic and developmental approach. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(1), 112–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1384505

- Lee, M. J., Whitehead, J., Ntoumanis, N., & Hatzigeorgiadis, A. (2008). Relationships among values, achievement orientations, and attitudes in youth sport. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 30(5), 588–610. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.30.5.588

- Leijen, I., van Herk, H., & Bardi, A. (2022). Individual and generational value change in an adult population, a 12-year longitudinal panel study. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-22862-1

- Madigan, D. J., Mallinson-Howard, S. H., Grugan, M. C., & Hill, A. P. (2020). Perfectionism and attitudes towards doping in athletes: A continuously cumulating meta-analysis and test of the 2× 2 model. European Journal of Sport Science, 20(9), 1245–1254. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2019.1698660

- Mazanov, J., & Huybers, T. (2015). Societal and athletes’ perspectives on doping use in sport. In V. Barkoukis, L. Lazuras, & H. Tsorbatzoudis (Eds.), The psychology of doping in sport (pp. 140–151). Routledge/Taylor & Francis.

- Mazanov, J., Huybers, T., & Barkoukis, V. (2019). Universalism and the spirit of sport: Evidence from Greece and Australia. Sport in Society, 22(7), 1240–1257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1512589

- Mazanov, J., Huybers, T., & Connor, J. (2012). Prioritising health in anti-doping: What Australians think. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 15(5), 381–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2012.02.007