ABSTRACT

The aims of the present study were two-fold: (a) to examine the links between two sets of perceived coach behaviours (supportive and controlling) and psychological safety, as well as (b) to explore whether the quality of the coach-athlete relationship explains the link between the two sets of coach behaviours and psychological safety. A total of 295 Turkish athletes (42% female and 58% male) in team sports with a mean age of 21.69 (±4.71) completed a multi-section questionnaire that measured the three main variables of the study, namely, coach behaviours, coach-athlete relationship quality, and psychological safety. Structural equation modelling revealed that both perceived coach behaviours (supportive and thwarting/controlling) and coach-athlete relationship quality predicted athletes’ psychological safety in their team. Moreover, the quality of the coach-athlete relationship explained the association between athletes’ perceptions of coach behaviours and psychological safety within the team context. The findings of this study contribute to growing research that examines the processes by which psychological safety can be nurtured in sports. While evidence thus far suggests that a coach orchestrates the environment, the findings of this study would seem to suggest that athletes, through good-quality relationships with their coaches, can stimulate the creation of a psychologically safe environment. The findings are discussed with a particular emphasis on future research directions and practical applications.

Psychological safety is a critical factor in understanding phenomena such as peoples’ freedom of expression, the complex dynamics of teamwork, engagement and experience, as well as individual, team, and organisational learning (Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014). Within the work and organisational context, psychological safety has been found to promote communication and teamwork by allowing individuals to be comfortable expressing and being themselves and sharing concerns and mistakes without fear of shame, ridicule, or retribution (Torralba et al., Citation2020). Edmondson (Citation1999, Citation2004) described psychological safety as the belief that a person’s environment is safe for interpersonal risk-taking; as such, others within a team/group (or organisational environment) will not humiliate, embarrass, reject, or punish those who make mistakes, speak up and raise challenging issues. Psychological safety reflects a positive interpersonal environment whereby individuals feel free to express themselves without fear (“felt permission for candour”; see Gallo, Citation2023). Psychological safety has been characterised as the engine of performance because of the opportunities it affords to individuals. Especially in situations that demand effective communication, trust, and decision-making under pressure (Edmondson, Citation2004). A psychologically safe environment enables individuals to feel safe to engage in difficult conversations and consider changes to practice (Brown & McCormack, Citation2016). Within such psychologically safe environments, individuals can more fully and freely contribute to performance through enhanced team processes (Kim et al., Citation2020) and learning behaviours (Parker & du Plooy, Citation2021). Leadership and relationship networks are key factors that can impact psychological safety, generating either positive (e.g., positive attitudes, learning, performance, innovation) or negative (e.g., stress, conflict, negative attitudes) outcomes (Newman et al., Citation2017).

In sports contexts, more often than not, situations both in training and competition, including situations on and off the field of play (sport), call for open communication, interpersonal trust and effective decision-making, making psychological safety a crucial component for both performance success and personal satisfaction (Gosai et al., Citation2023). As a result, psychological safety has garnered significant attention within the sport literature in recent years (e.g., Jowett et al., Citation2023; Smittick et al., Citation2019). Nonetheless, it is essential to note that sports scholars have raised concerns about the applicability of psychological safety to sport (see Taylor et al., Citation2022) and introduced alternative conceptualisations of psychological safety in sport coaching (Vella et al., Citation2022) as well as developed measures that assess psychological safety in specific sport contexts such mental health (e.g., Rice et al., Citation2022). For the purpose of this study, Edmondson’s conceptualisation and its accompanying scale of psychological safety were utilised as there is sufficient evidence to demonstrate its sound psychometric properties and relevance to sport (e.g., Fransen et al., Citation2020; Gosai et al., Citation2023).

For example, Fransen et al. (Citation2020) conducted a study that explored the impact of psychological safety on the association between identity leadership, team performance, and athlete wellbeing. Their research findings indicated that the perceived quality of leadership among handball players facilitated the development of a social identity, consequently fostering a psychologically safe environment. This environment, in turn, contributed to optimal team functioning, encompassing teamwork, resilience, and satisfaction with both individual and team performance. Additionally, the study revealed that individual functioning, specifically good personal health, was also positively influenced by the presence of psychological safety within the team context. Jowett et al. (Citation2023) investigated the conditions for psychological safety and the influence of psychological safety on the quality of the coach-athlete relationship, revealing that psychological safety mediated the association between athletes’ voice, namely, the capacity to communicate openly and manage conflict, and perceived relationship quality with the coach. Moreover, Gosai et al. (Citation2023) revealed that perceived coach transformational leadership behaviours significantly impacted team psychological safety and the quality of the coach-athlete relationship. Subsequently, these two psychosocial factors were found to be influential in athletes’ perceptions of functioning both physically and emotionally.

Coaches as leaders and their behaviours in relation to the athletes they coach have been the subject of research for decades. Coach behaviours have been studied employing various approaches, including leadership theories and/or relationship conceptual frameworks (e.g., Fransen et al., Citation2020; Jowett et al., Citation2023) as well as motivational theories (e.g., Bartholomew et al., Citation2009; Mageau & Vallerand, Citation2003). Research that involves psychological safety in sport has, up until now, focused primarily on examining coaches’ behaviours employing leadership models (Fransen et al., Citation2020; Gosai et al., Citation2023; Smittick et al., Citation2019). The present study examined coach behaviour guided by self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, Citation1987). Deci and Ryan have argued that (coach) behaviours can serve to support autonomy and thus promote one’s (athlete’s) choice, provide constructive feedback, express affection and acknowledge progress on the one hand, or on the other hand to control behaviour and thus to pressure one (athlete) toward specific deadlines and outcomes by providing critical feedback that undermines and humiliates (see Ahmadi et al., Citation2023). These two sets of behaviours were said to either support or hinder individuals’ basic psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness (see Ryan & Deci, Citation2000).

Briefly, autonomy refers to the freedom one has and is demonstrated by making independent choices and meaningful decisions; it involves individuals’ ability to make decisions for themselves and have those decisions respected by others as long as they do not harm others (Ryan, Citation1995). Competence encompasses a sense of mastery and proficiency in one’s actions; competence is viewed as a multifaceted construct that includes both ability and quality (Schneider, Citation2019). Relatedness reflects one’s sense of belonging and connection with others and indicates the degree to which an individual experiences caring relationship/s (Ryan & Deci, Citation2017). Accordingly, these needs must be fulfilled to foster self-motivation, determination, healthy psychological growth, and optimal wellbeing (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). There is ample evidence in the sport literature to show that coaches’ supportive behaviours can satisfy athletes’ needs of autonomy, competence, and relatedness, while coaches’ controlling behaviours can thwart these needs (see e.g., Amorose & Anderson-Butcher, Citation2007; Bhavsar et al., Citation2019; Felton & Jowett, Citation2013; Fransen et al., Citation2018; Hollembeak & Amorose, Citation2005; Jowett et al., Citation2017a; Rocchi et al., Citation2017; Sheldon & Filak, Citation2008; Skinner et al., Citation2008). However, no research to our knowledge has investigated perceptions of supportive and controlling coach behaviours as predictors of psychologically safe environments.

In competitive sports, performance teams experience challenges (e.g., learning new skills and techniques, performance slumps, lack of motivation and self-esteem, injury-related, burnout, and de/non-selection) that require athletes and coaches to navigate effectively. Research has shown that coaches, as leaders, through a range of behaviours, set the tone for an environment that is conducive to psychological safety (e.g., Fransen et al., Citation2020; Gosai et al., Citation2023; Smittick et al., Citation2019). In a psychologically safe environment, athletes are more likely to be in a position to learn and develop, take intelligent risks and perform freely while enjoying their sport thoroughly without fear of intimidation or humiliation. In these environments, athletes are also more likely to engage in learning behaviours, such as sharing ideas, asking questions, seeking feedback, taking ownership and being accountable for their own development. Lack of psychological safety limits athletes’ freedom to express themselves, stifles their motivation, extinguishes their dreams, and exhausts the mind and spirit (Maughan & Jowett, Citation2023). Thus, psychological safety within the context of sport can be a critical factor for creating a culture of growth, resilience, and continuous learning and development.

Coach leader behaviours and good quality coach-athlete relationships are associated with perceptions of psychological safety (e.g., Gosai et al., Citation2023; Jowett et al., Citation2023; Maughan & Jowett, Citation2023), supporting Kahn’s (Citation1990) and Edmondson and Lei’s (Citation2014) assertion that people are more likely to feel psychologically safe when they have good quality interpersonal relationships. It is thus possible that the quality of the coach-athlete relationship encompassing relational properties such as closeness (e.g., trust, respect, appreciation), commitment (e.g., long-term orientation toward a close-knit relationship) and complementarity (e.g., responsive, friendly, comfortable cooperative actions and interactions) (see, Jowett & Slade, Citation2021), feed into a psychologically safe environment.

Building on theory and previous research, this study aimed to (a) investigate the links between two sets of coach behaviours (supportive and controlling) and psychological safety and (b) explore whether the quality of the coach-athlete relationship explains the link between the coach behaviours and psychological safety. The emphasis was on understanding how coaches’ behaviours influence psychological safety through quality coach-athlete relationships. If the coach-athlete relationship quality is shown to be a mediator, then it would suggest that athletes’ perception of autonomy-supportive behaviours by their coaches predict psychological safety through their perceptions of good quality relationships with coaches on the one hand and potentially perceptions of good quality coach-athlete relationships alleviate the negative effects of their coaches’ controlling behaviours on psychological safety on the other hand.

The practical significance of this study lies in extending our understanding of the processes by which psychological safety can be nurtured in sport teams. While evidence thus far suggests that the coach orchestrates the environment (see also Jones & Ronglan, Citation2018), the findings of this study would contribute to explaining whether the athletes, through their relationships with their coaches, can stimulate and contribute to creating a psychologically safe environment. The significance of positive coach behaviours, healthy coach-athlete relationships, and psychologically safe environments have been acknowledged by both research findings (e.g., Vella et al., Citation2022) and more recently policy making at the national (e.g., Whyte, Citation2022) and international stage (e.g., IOC, Citation2023).

Recently, the International Olympic Committee issued its Mental Health Action Plan (IOC, Citation2023) and highlighted that sound leadership and a safe environment are instrumental components for athletes’ physical and psychological wellbeing. These components “ offer the opportunity for achievement at the highest levels of both athletic performance and overall good health” (p. 5). When coaches and athletes prioritise building strong relationships, exhibiting positive interpersonal behaviours and promoting psychologically safe environments, they establish the groundwork for growth, performance, and overall success without compromising one’s mental health and wellbeing. These factors would seem to be essential for achieving mastery and excellence across sports. Thus, our aim is to contribute to a deeper understanding of the dynamic and complex associations involved between psychological safety, the coach-athlete relationship, and athletes’ experiences of autonomy and controlling coach behaviours within the context of sport teams.

Method

Participants

Two hundred and ninety-five Turkish team athletes (19 teams), including football (n = 43, 14.6%.), basketball (n = 53; 18%), volleyball (n = 48; 16.3%), handball (n = 35; 11.9%), hockey (n = 35; 11.9%), cricket (n = 50; 16.9%), and American football (n = 31; 10.5%) participated in the study. Participants included 124 female (42%) and 171 male athletes (58%), with an age mean of 21.69 ± 4.71. Athletes reported training in their respective sport for 8.67 ± 5.31 years. Athletes competed at regional (n = 179, 60.7%) and national levels (n = 116; 39.3%). Athletes reported that they have been working with their coaches for 2.98 ± 3.34 years and their current team for 3.02 ± 3.24 years. They also reported 2.21 ± 0.71 hours of training per day.

Procedure

Institutional approval was granted by the ethical committee of social sciences at a state university. We contacted prospective participants (team athletes) and coaches via email, social media, and in-person visits. We distributed the online survey to athletes directly or via their coaches. The team athletes who expressed an interest in the study were made aware of the voluntary, confidential, and anonymous nature of their participation and were kindly asked to sign electronically the consent form as well as to carefully read the purpose, requirements, and information of the study before filling out the short survey.

Measures

The coach-athlete relationship questionnaire

The Coach-Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART-Q; Jowett & Ntoumanis, Citation2004) was used to assess coach-athlete relationship quality. The 11 items assess closeness (4 items, e.g., I trust my coach), commitment (3 items, e.g., I am committed to my coach), and complementarity (4 items, e.g., When I am coached by my coach, I am responsive to his/her efforts). The mean score of the items reflected the overall relationship quality. The Turkish version of CART-Q was validated by Altintaş et al. (Citation2012) in Turkish and was employed for the purpose of this study. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with this sample reported good fit indices (χ²/df = 6,16, CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.05) for the items of the Turkish version of the CART-Q.

The interpersonal behaviours questionnaire in sport

The Interpersonal Behaviours Questionnaire in Sport (IBQ-Sport; Rocchi, Pelletier ve Rocchi et al., Citation2016) was employed to assess coaches’ supportive and thwarting or controlling behaviours. Specifically, the 24 items measured three subdimensions of coach supportive behaviours: autonomy (4 items, e.g., My coach gives me the freedom to make my own choices), competence (4 items, e.g., My coach tells me that I can accomplish things), and relatedness (4 items, e.g., My coach takes the time to get to know me). It also measured three subdimensions of coach controlling behaviours: autonomy (4 items, e.g., My coach pressures me to do things their way), competence (4 items, e.g., My coach points out that I will likely fail), and relatedness (4 items, e.g., My coach does not connect with me). The Turkish version of IBQ-S was validated by Yildiz and Şenel (Citation2018) in Turkish and was utilised in this study, and CFA with this sample reported good fit indices (χ²/df = 2.49, CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92, SRMR = 0.05).

The psychological safety scale

The Psychological Safety Scale (Edmondson, Citation1999) of 7 items was employed to assess athletes’ perception of psychological safety within their teams. The scale contained items such as “It is safe to take a risk on this team” and “If I make a mistake on this team, it is not held against me.” The psychological safety scale's psychometric properties (reliability and/or validity) were acceptable in previous studies (Fransen et al., Citation2020; Gosai et al., Citation2023). As there was no Turkish version of the scale adapted to sport (see Yener, Citation2015, for the Turkish version translated with non-athletes), we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to examine its factorial validity. One item had insignificant factor loadings and was removed from the model (“Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues”). CFA showed that the final 6-item psychological safety scale reported a good fit for this sample (χ²/df = 1.65; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.04; 95%C.I. = 0.00-0.09).

Data analysis

Preliminary analysis

To ensure the integrity of our study, we conducted a comprehensive examination of the data. This included analysing patterns of missing data and assessing the normality of our data by scrutinising skewness and kurtosis scores (Bai & Ng, Citation2005). It is important to note that no missing data were recorded. To mitigate the likelihood of Type I and Type II errors, suitable inclusion criteria and sample size were considered (Fritz & MacKinnon, Citation2007), and a 0.05 significance level for hypothesis testing was employed (Kline, Citation2005). We calculated the power by using Monte Carlo Power Analyses for Indirect Effect, where we entered the standardised coefficient and standard deviation of study variables (Schoemann et al., Citation2017). The equation yielded 0.83 actual power for n = 295. Means, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis values, and Pearson correlations were conducted via SPSS 26.0 ().

Table 1. Summary of bivariate correlations, means, standard deviations, reliability, skewness, and kurtosis scores.

Main analysis

Two mediation models were tested: Model 1 tested perceived coaches’ supportive behaviour as the predictor of psychological safety (outcome) and coach-athlete relationship as the mediator, and Model 2 tested perceived coach controlling behaviour as the predictor of psychological safety (outcome) and coach-athlete relationship as the mediator. These analyses were performed using IBM AMOS® whereby delta method standard errors, normal theory confidence intervals, and maximum likelihood estimator were employed while bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals were estimated for all effects. An effect was considered significant when the confidence interval did not contain zero.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlational analysis

presents the study variables’ intercorrelations, means, standard deviations, skewness and kurtosis values, and reliability estimates. The mean scores on the 1–7 response scale revealed that athletes’ scores varied from low to moderately high across the main variables of the study. The alpha coefficients showed acceptable levels of internal consistency ranging from (0.71-0.94). The range of kurtosis and skewness were also acceptable (Field, Citation2009).

Mediation analyses

The two models tested are presented next.

Model 1

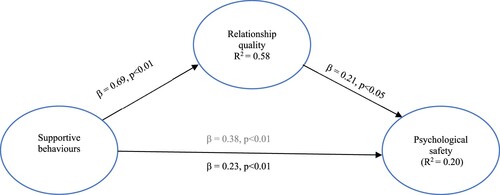

The analysis evaluated whether the effects of supportive coach behaviours perceived by athletes on psychological safety were mediated by coach-athlete relationship quality. The direct and indirect impact of supportive coach behaviours and relationship quality on psychological safety are summarised in and . In , supportive coach behaviours positively predicted psychological safety (β = 0.38, p < 0.01). It also shows the role of relationship quality between supportive coach behaviours and psychological safety.

Figure 1. The Indirect Effect of Supportive Behaviours on Psychological Safety Through Coach-athlete Relationship. Note. The grey text shows the linear regression coefficient between supportive behaviours and psychological safety. The unstandardised coefficients for each effect are reported.

Table 2. Direct and indirect effects of psychological safety on relationship quality.

The indirect effect of supportive coach behaviours on psychological safety was statistically significant (see for details). The positive indirect effect is 0.14. Supportive coach behaviours predicted psychological safety (0.38, see ). Relationship quality predicts psychological safety (0.21). Supportive coach behaviours had an indirect and positive statistical effect on psychological safety via relationship quality.

Table 3. Direct and indirect effects of controlling behaviours on psychological safety.

Model 2

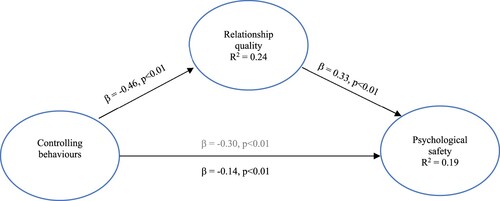

The analysis evaluated whether the effects of controlling coach behaviours perceived by athletes on psychological safety had an indirect effect, suggesting that psychological safety was mediated by coach-athlete relationship quality. represents the direct effect of controlling coach behaviours on relationship quality. It also displays that relationship quality is a mediator between controlling behaviours and psychological safety.

Figure 2. The Indirect Effect of Controlling Behaviours on Psychological Safety Through the Coach-athlete Relationship. Note. The grey text shows the linear regression coefficient between controlling behaviours and psychological safety. The unstandardised coefficients for each effect are reported.

The estimation of direct and indirect effects of controlling coach behaviours are summarised in . The indirect effect of controlling coach behaviours on psychological safety was statistically significant.

Relationship quality predicts psychological safety (0.33). Controlling coach behaviours predicted psychological safety (−0.30, see ). Moreover, controlling coach behaviours had an indirect and negative statistical effect, suggesting that relationship quality had a mediation role by reducing the effects from controlling behaviours to psychological safety. The negative indirect effect was – 0.15.

Discussion

In an attempt to expand the limited knowledge around psychological safety in sport, the aims of the present study were two-fold: (a) to investigate the links between psychological safety and two specific sets of perceived coach behaviours, namely, supportive and controlling or thwarting behaviours, and (b) to explore whether the quality of the coach-athlete relationship transfers the effects of the perceived coach behaviours of support and control on psychological safety.

Firstly, it was found that athletes who perceive that their coaches engage in behaviours that support their autonomy, competence and relatedness are more likely to experience the team environment as psychologically safe. Moreover, it was found that athletes who perceive that their coaches do not engage or engage less with behaviours that thwart their autonomy, competence and relatedness are more likely to experience psychological safety within their respective teams. These results are consistent with similar research that has started to emerge in sport, indicating that coaches, through their leadership behaviours, can set the tone for psychological safety (e.g., Fransen et al., Citation2020; Gosai et al., Citation2023). These results provide some evidence of the potential motivational properties psychological safety may have in that athletes whose coaches support their autonomy, as well as their competence and relatedness, are more likely to feel motivated to learn by freely expressing themselves (e.g., experimenting, try new things, take risks) in the knowledge that they won’t be reprimanded or humiliated by coaches or team members. Future research could examine the ways athletes’ perceptions of psychological safety within their sport environment promote the different types of motivation (intrinsic versus extrinsic; Ryan & Deci, Citation2010) and, in turn, their wellness (see Walton et al., Citation2023).

Moreover, this study is consistent with the ever-growing empirical evidence that shows the positive links between coach leadership behaviours and coach-athlete relationship quality (e.g., Felton & Jowett, Citation2013; Jowett et al., Citation2017a; López de Subijana et al., Citation2021; Zhao & Jowett, Citation2023). Employing social exchange processes as a framework (e.g., interdependent theory, self-determination theory, social learning theory), the findings of this study may indicate that when athletes’ autonomy, competence and relatedness are supported (or not thwarted) by the coach, they will reciprocate with a strengthened connection to their coach (see Jowett et al., Citation2017b). In line with conceptual and empirical work in sport (e.g., Jowett et al., Citation2023) and organisation (Edmondson & Lei, Citation2014; Kahn, Citation1990; Newman et al., Citation2017), the quality of interpersonal relationships has been linked with and predicted by psychological safety. Based on social learning processes, it may be that athletes who feel connected with their coaches are more likely to pay attention to them, learn from them, and identify with them, and in turn, this key dyadic coach-athlete connection may spill over to other interpersonal bonds (e.g., teammates, other coaching staff, medical and sport science support staff) making the network of relationships an important determinant of psychological safety. Future research could, for example, examine whether athletes’ perceptions of collective efficacy, team cohesion, and teammate dyadic relationships affect and are affected by the degree to which the environment is psychologically safe.

Secondly, results indicated that the coach-athlete relationship has the capacity to transfer the effects of coach behaviours onto athletes’ feelings of psychological safety in the team. The quality of the coach-athlete relationship as a mediator allows us to understand the key processes involved in engendering a psychologically safe environment for athletes who operate in team sports. Specifically, the findings from the mediation analyses highlighted that athletes’ good quality relationships with coaches are likely to enhance the positive effects of coaches’ supportive behaviours on psychological safety, while athletes’ good quality relationships with coaches are likely to lower the negative effects of coaches thwarting or controlling behaviours on psychological safety. This set of findings is consistent with conceptual work that argued that leader behaviours and interpersonal relationships are determinants of psychological safety in sport (e.g., Vella et al., Citation2022) and other contexts (e.g., Newman et al., Citation2017). A significant observation from the results of this study was that not only coaches as leaders through their behaviours but also athletes through their relationships have the capacity to contribute to setting the tone for psychological safety. Athletes who can develop and maintain good relationships with their coaches are more likely to contribute toward a positive interpersonal climate. An interpersonal climate within which everyone can take interpersonal risks, such as speaking up, voicing concerns, and expressing alternative ideas without fear of humiliation or punishment. This is in line with Edmondson (Citation2019), who stated, “A leader can be the force and catalyst for others to speak up; but ultimately the practice must be co-created – and continuously nurtured – by multiple stakeholders” (p. 140).

From a practical viewpoint, the results of this study highlight that what coaches do and what behaviours they manifest during training and/or competition can play an important role in shaping an environment that is more (or less) psychologically safe. Coach supportive behaviours that incorporate choice, progression, and connection shape an interpersonal climate within which everyone feels they can be honest, open and truthful. Subsequently, coach education would need to ensure that coaches are exposed to material that enhances their awareness, knowledge, and skills to emit positive, supportive behaviours while recognising the deleterious effects of negative controlling or thwarting behaviours on the interpersonal environment. Correspondingly, the results of this study highlight that athletes’ perceptions of good quality relationships with their coaches can impact the interpersonal climate so much so that the negative effects of coaches’ controlling or thwarting behaviours can be reduced if, in athletes’ eyes, the relationships with their coaches are respectful, committed and cooperative. Especially in competitive sports where volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and vulnerability are common characteristics (e.g., Maughan & Jowett, Citation2024), athletes’ skills to develop good quality relationships with their coaches may lessen the negative effects of coaches’ controlling or thwarting behaviours on the interpersonal environment. It is quite plausible that when coaches manifest control (e.g., curtailed choice, negative feedback) due to a specific situation or circumstance, athletes who have functional and healthy relationships with their coaches can respond in a way that does not negatively impact themselves or their environment. Subsequently, athlete education would need to enhance athletes’ knowledge of the role and significance of good quality coach-athlete relationships as well as enhance athletes’ relationship and communication skills.

It is important to acknowledge the cross-sectional results of this study as a limitation. While one-off cross-sectional surveys are one of the most commonly used methods in the social sciences to collect data, they pose a threat of common method variance that can influence the reliability and validity of the empirical results (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). In this study, we attempted to minimise possible common method variance through the following ways: reversing the wording of some items, varying types of response scale options and anchor labels, as well as ensuring anonymity of respondents and highlighting that there are no right or wrong answers. Moreover, acknowledging the dynamic interplay between coach leader behaviours, interpersonal relationships and psychological safety, we recommend future research studies to employ more sophisticated methodological approaches such as longitudinal and experimental research designs. For example, it would be advantageous to design studies considering the temporal patterning that a mediation analysis implies. For example, a study that captures coaches’ behaviours (Time 1), athletes’ relationships with their coaches (Time 2), and perceptions of safety within their teams (Time 2/3). Intervention and experimental studies can address cause-and-effect associations. The expectation is such a study could deliberately increase or decrease the level of the coach-athlete relationship quality (as defined by closeness, commitment, and complementarity) and then examine whether a change in relationship quality causes a change in perceived or actual coach behaviours and levels of psychological safety.

As no research to our knowledge directly captures coaches’ viewpoints relevant to psychological safety, it would also be important to engage coaches in research in an effort to unravel the impact of their coach (leadership) behaviours and relationships with athletes, as well as coach-created motivational climates on the level of psychological safety experienced either by employing qualitative (e.g., interviews, observations) or quantitative (e.g., surveys, experiments) research methods. Last but not least, it would benefit to consider employing multilevel or hierarchical linear modelling, especially if the aim is to examine team-level effects for the coaches and athletes nested within dyads, teams, clubs and/or organisations. Research that considers measuring psychosocial variables such as relationships, behaviours and climates employing multilevel structures (e.g., athletes and coaches nested within groups) would further advance knowledge at both conceptual and practical levels. For future research, it would be valuable to expand the scope of this study to consider the dynamics between athletes and the entire coaching staff or organisation. Investigating the relationships between athletes and all levels of coaches, as well as the general interactions with all staff members from the athletes’ perspective, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of these relationships on athletic performance and wellbeing.

The proliferation of incidents whereby coaches are alleged to maltreat, abuse, bully, and exploit athletes (e.g., Whyte, Citation2022) call for sound leadership and safe environments within which everyone involved in sport can excel, master, thrive and flourish (see, International Olympic Committee issued its Mental Health Action Plan, IOC, Citation2023). Our research showed that promoting a psychologically safe environment depends on building strong coach-athlete relationships and exhibiting supportive coach behaviours. The practical applications of the findings of this research revolve around the importance of perceived coach behaviours that are supportive on athletes’ experience of psychological safety as well as on the direct and indirect effects of athletes’ relationship quality with the coach on experiencing psychological safety within the context of their team. Collectively, the findings suggest that coaches can create psychological safety and can also be (co-)created by the athletes (see also Jowett et al., Citation2023). It is thus important to raise athletes’ awareness of the important role quality relationships play in their development and satisfaction. Raising awareness implies that athletes have the knowledge and skills to develop coach-athlete relationships that work.

To conclude, despite the sceptics who have questioned the applicability of psychological safety in sport (Taylor et al., Citation2022), research thus far would seem to suggest that psychological safety in sport is an important contributor to athletes’ wellbeing and functioning (Fransen et al., Citation2020) as well as thriving and flourishing (Gosai et al., Citation2023). The present research added to this evidence by highlighting that supportive leader behaviours and healthy bonds build psychological safety within sport teams. This finding seems consistent with original conceptions of psychological safety in business contexts (e.g., Edmondson, Citation1999; Kahn, Citation1990). While research in sport remains limited, there is accumulated evidence to suggest that psychological safety is important for individuals, teams, and organisations. Thus, future research should continue to examine the correlates of psychological safety in an effort to advance understanding and build an edifice of knowledge within sport settings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ahmadi, A., Noetel, M., Parker, P., Ryan, R. M., Ntoumanis, N., Reeve, J., Beauchamp, M., Dicke, T., Yeung, A., Ahmadi, M., Bartholomew, K., Chiu, T. K. F., Curran, T., Erturan, G., Flunger, B., Frederick, C., Froiland, J. M., González-Cutre, D., Haerens, L., … Lonsdale, C. (2023). A classification system for teachers’ motivational behaviors recommended in self-determination theory interventions.. Journal of Educational Psychology. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000783

- Altintaş, A., Çetinkalp, Z. K., & Aşçi, F. H. (2012). Evaluating the coach-athlete relationship: Validity and reliability study. Hacettepe Journal of Sport Sciences, 23(3), 119-128.

- Amorose, A.J., & Anderson-Butcher, D. (2007). Autonomy-supportive coaching and self-determined motivation in high school and college athletes: A test of self-determination theory. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(5), 654-670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.11.003

- Bai, J., & Ng, S. (2005). Tests for skewness, kurtosis, and normality for time series data. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, 23(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1198/073500104000000271

- Bartholomew, K. J., Ntoumanis, M., & Thøgersen-Ntoumani, C. (2009). A review of controlling motivational strategies from a self-determination theory perspective: Implications for sports coaches. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 2(2), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/17509840903235330

- Bhavsar, N., Ntoumanis, N., Quested, E., Gucciardi, D. F., Thøgersen-Ntoumanis, C., Ryan, R. M., Reeve, J., Sarrazin, P., & Bartholomew, K. J. (2019). Conceptualizing and testing a new tripartite measure of coach interpersonal behaviors. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 44, 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.05.006

- Brown, D., & McCormack, B. (2016). Exploring psychological safety as a component of facilitation within the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services framework. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(19-20), 2921-2932. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13348

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1024–1037. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological Safety and Learning Behavior in Work Teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

- Edmondson, A. C. (2004). Learning from failure in health care: Frequent opportunities, pervasive barriers. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 13(suppl_2), ii3-ii9. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2003.009597

- Edmondson, A. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons..

- Edmondson, A., Kramer, R. M., & Cook, K. S. (2004). Trust and learning in organisations: A group-level lens. In R. Kramer and K. Cook (Eds), Trust and distrust in organisations: Dilemmas and Approaches (pp. 239-272). Russell Sage Foundation.

- Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1(1), 23-43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091305

- Felton, L., & Jowett, S. (2013). ““What do coaches do” and “how do they relate”: Their effects on athletes' psychological needs and functioning. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 23, 130-139. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12029

- Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS. SAGE.

- Fransen, K., McEwan, D., & Sarkar, M. (2020). The impact of identity leadership on team functioning and well-being in team sport: Is psychological safety the missing link? Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 51, 101763. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101763

- Fransen, K., Vansteenkiste, M., Vande Broek, G., & Boen, F. (2018). The competence-supportive and competence-thwarting role of athlete leaders: An experimental test in a soccer context. PLoS One, 13(7), e0200480. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0200480

- Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18(3), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x

- Gallo, A., (2023). What is psychological safety? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/02/what-is-psychological-safety

- Gosai, J., Jowett, S., & Nascimento-Júnior, J. R. A. D. (2023). When leadership, relationships and psychological safety promote flourishing in sport and life. Sports Coaching Review, 12(2), 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/21640629.2021.1936960

- Hollembeak, J., & Amorose, A.J. (2005). Perceived Coaching Behaviors and College Athletes' Intrinsic Motivation: A Test of Self-Determination Theory. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 17(1), 20 - 36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413200590907540

- IOC. (2023). Mental health action plan. International Olympic Committee. https://stillmed.olympics.com/media/Documents/News/2023/07/Mental-Health-Action-Plan-2023.pdf?_ga=2.244501505.542975951.1688997040-1883207055.1688997040

- Jones, R.L., & Ronglan, L.T. (2018) What do coaches orchestrate? Unravelling the ‘quiddity’ of practice. Sport, Education and Society, 23(9), 905-915, https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2017.1282451

- Jowett, S., Bartholomew, K., Adie, J., Yang, X. S., Gustafsson, H., & Jimenez, A. (2017). Motivational processes in the coach-athlete relationship: A multi-cultural self-determination approach. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 32, 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2017.06.004

- Jowett, S., Do Nascimento-Júnior, J. R. A., Zhao, C., & Gosai, J. (2023). Creating the conditions for psychological safety and its impact on quality coach-athlete relationships. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 65, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2022.102363

- Jowett, S., Michel, N., & Yang, S. (2017b). Unravelling the links between coach behaviours and coach-athlete relationships. European Journal of Sports and Exercise Science, 5(3), 10-19.

- Jowett, S., & Ntoumanis, N. (2004). The Coach–Athlete Relationship Questionnaire (CART-Q): development and initial validation. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 14(4), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2003.00338.x

- Jowett, S., & Slade, K. (2021). Coach-athlete relationships; The role of ability, intentions and integrity. In C. Heaney, N. Kentzer, & B. Oakley (Eds.), Athletic development: A psychological perspective (pp. 89–106.

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.2307/256287

- Kim, S., Lee, H., & Connerton, T. P. (2020). How psychological safety affects team performance: mediating role of efficacy and learning behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1581. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01581

- Kline, T. J. (2005). Psychological testing: A practical approach to design and evaluation. Sage.

- López de Subijana, C., Martin, L. J., Ramos, J., & Côté, J. (2021). How coach leadership is related to the coach-athlete relationship in elite sport. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 16(6), 1239–1246. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541211021523

- Mageau, G. A., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). The coach-athlete relationship: A motivational model. Journal of Sports Sciences, 21(11), 883–904. https://doi.org/10.1080/0264041031000140374

- Maughan, A. B., & Jowett, S. (2024). Psychological safety in elite swimming: Fearful versus fearless coaching environments. International Sport Coaching Journal, 1, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2023-0048

- Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001

- Parker, H., & du Plooy, E. (2021). Team-based games: Catalysts for developing psychological safety, learning and performance. Journal of Business Research, 125, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.010

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63(1), 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452

- Rice, S., Walton, C. C., Pilkington, V., Gwyther, K., Olive, L. S., Lloyd, M., Kountouris, A., Butterworth, M., Clements, M., & Purcell, R (2022). Psychological safety in elite sport settings: A psychometric study of the Sport Psychological Safety Inventory. BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine, 8, e001251. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2021-001251

- Rocchi, M., Pelletier, L., Cheung, S., Baxter, D., & Beaudry, S. (2017). Assessing need-supportive and need-thwarting interpersonal behaviours: The Interpersonal Behaviours Questionnaire (IBQ). Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.08.034

- Rocchi, M., Pelletier, L., & Desmarais, P. (2016). The Validity of the Interpersonal Behaviors Questionnaire (IBQ) in Sport. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 21(1), 15-25. https://doi.org/10.1080/1091367X.2016.1242488

- Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63(3), 397–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and wellbeing. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2010). A self-determination theory perspective on social, institutional, cultural, and economic supports for autonomy and their importance for well-being. In Valery I. Chirkov, Richard M. Ryan, & Kennon M. Sheldon (Eds.), Human autonomy in cross-cultural context: Perspectives on the psychology of agency, freedom, and well-being. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

- Ryan, R.M., & Deci, E.L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. Guilford Press.

- Schneider, K. (2019). What does competence mean? Psychology (savannah, Ga ), 10(14), 1938-1958. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2019.1014125

- Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

- Sheldon, K. M., & Filak, V. (2008). Manipulating autonomy, competence, and relatedness support in a game-learning context: New evidence that all three needs matter. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466607X238797

- Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and disaffection in the classroom: Part of a larger motivational dynamic? Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 765-781. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012840

- Smittick, A. L., Miner, K. N., & Cunningham, G. B. (2019). The “I” in team: Coach incivility, coach gender, and team performance in women’s basketball teams. Sport Management Review, 22(3), 419–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.06.002

- Taylor, J., Collins, D., & Ashford, M. (2022a). Psychological safety in high-performance sport: Contextually applicable? Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2022.823488

- Torralba, K. D., Jose, D., & Byrne, J. (2020). Psychological safety, the hidden curriculum, and ambiguity in medicine. Clinical Rheumatology, 39(3), 667–671. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-019-04889-4

- Vella, S. A., Mayland, E., Schweickle, M. J., Sutcliffe, J. T., McEwan, D., & Swann, C. (2024). Psychological safety in sport: A systematic review and concept analysis. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2022.2028306

- Walton, Q. L., Coats, J. V., Skrine Jeffers, K., Blakey, J. M., Hood, A. N., & Washington, T. (2023). Mind, body, and spirit: A constructivist grounded theory study of wellness among middle-class Black women. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2023.2278288

- Whyte, A. (2022). The whyte review. https://www.uksport.gov.uk/resources/the-whyte-review/whyte-review-report

- Yener, S. (2015). The validity and reliability study of the Turkish version of the psychological safety. Ordu Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi, 5(13), 280-305.

- Yildiz, M., & Şenel, E. (2018). Interpersonal behaviours questionnaire in sport: Validity and reliability of turkish form. Gazi Beden Eğitimi ve Spor Bilimleri Dergisi, 23(4), 219-231.

- Zhao, C., & Jowett, S. (2023). Before supporting athletes, evaluate your coach-athlete relationship: exploring the link between coach leadership and coach-athlete relationship. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 18 (3), 631-644. https://doi.org/10.1177/174795412211481