Abstract

The rising influence of consumer culture on sport participation is arguably one of the most influential trends in sport participation in the last decades. However, little is known about how such an attitude can be understood and what its consequences for everyday life in sport organizations are. This article asks how a research scale for consumerism in sport organizations could be conceptualized and constructed. Using a mixed methods approach, a research scale consisting of five sub-dimensions was developed to measure consumerist attitudes in sport organizations. The scale was tested on 303 sport participants in various sport organizations. The resulting 25-item research scale for consumerism in sport organizations can be of use to sport scholars, sport policy makers and sport administrators and managers who want to gain a better understanding of the relationship between sport participants and sport organizations.

Introduction

‘The critical sport consumer of nowadays asks increasingly louder for flexibility in sport possibilities. He wants to exercise at the moment that the children are at school or directly after he finished his working day. One week one time, the other week perhaps three or four times’ (NOC*NSF, n.d.). Dutch umbrella sport organization NOC*NSF leaves no doubt in its observation of the contemporary sportsman. He is a critical consumer asking for flexibility and ‘customer-based, new and refreshing offers’ (NOC*NSF, n.d.). The emergence of a consumerist attitude among sport participants is not only observed by national sport organizations like NOC*NSF (cf. Van der Roest, Vermeulen, & Van Bottenburg, Citation2015), but it has attracted interest from researchers in sport studies as well (cf. Bodet, Citation2009; Horne, Citation2006; Ibsen & Seippel, Citation2010; Sassatelli, Citation2010; Smith Maguire, Citation2001). The consumerist attitude has been associated with a growing popularity of commercial sport organizations and the commercialization of nonprofit sport organizations (Enjolras, Citation2002; Ibsen & Seippel, Citation2010; Sassatelli, Citation2010).

Despite a growing attention for the emergence of a consumerist attitude among sport participants, little is known about how such an attitude can be understood and what its consequences for everyday life in sport organizations are. Indeed, researchers have expressed their worries about the increasing consumerist attitude, predominantly related to voluntary sport organizations, but the concept has yet been overlooked in empirical research. Policy makers in the voluntary sport sector have described the rise of the consumerist attitude, but they have done so in rather vague terms, leaving much room for interpretation. Moreover, they have not shown empirical evidence that such an attitude is present in sport. This has resulted in an ambiguous elaboration on the concept and its consequences for sport organizations (Van der Roest et al., Citation2015).

The aim of this article is to develop a reliable instrument for the measurement of the consumerist attitude among sport participants based on focus group interviews and a survey among sport participants. With such an instrument, it will be possible to quantitatively determine the consumerist attitude of members in sport organizations. This can help researchers to better understand the nature and degree of consumerism in a particular sport or a specific location. It can also assist policy makers and sport managers in the decisions they have to make concerning a specific sport organization.

Theoretical background

Consumerism in sport organizations

Much work on consumption in sport has been focused on the commodification of spectatorship and fandom (e.g. Giulianotti, Citation2005; Moor, Citation2007). However, since recent years the attention has been drawn to the influence of consumer culture on active sport participation as well. Roughly, three lines of research that deal with this influence can be distinguished. First, theories of consumer culture have concentrated on consumption of sport activities as a cultural practice. Second, sport management scholars have given attention to the effects of consumerism on expectations around service quality in sport organizations. Third, multiple authors have expressed their concerns about an increasing consumerist attitude among members of voluntary sport organizations. In the following sections, I will briefly review these three lines of research before turning to the definition and conceptualization of consumerism and the consumerist attitude.

Consumer culture and the meaning of sport as a cultural practice

Since the 1970s, fitness and health clubs have been typical examples of sport consumer marketplaces in which consumers can express their identity and lifestyle through commodified practices and relationships (Smith Maguire, Citation2001). According to Sassatelli (Citation2010), the mix of market relations, commercialized discipline and social relations are key to the way consumer culture has shaped attitudes and behaviours in fitness and health clubs. However, these behaviours and attitudes are not limited to the gym. Llopis-Goig (Citation2014) showed that post-materialist and individualistic tendencies are related to runners’ attitudes towards their sport and Harvey and St-Germain (Citation1998) noted that the commodification of sport transforms it to a standardized product. The standardization of sport is for example evident in the commercialization of lifestyle sports, which have become more accessible in order to serve as many consumers as possible (Beal & Smith, Citation2010; Celsi, Rose, & Leigh, Citation1993; Edwards & Corte, Citation2010; Salome, Citation2012).

Accessibility is needed, according to Bodet (Citation2009, 231), because ‘sport consumers have become increasingly impatient in their quest for sensations and pleasure’. This is in accordance with Pilgaard’s (Citation2012) analysis of flexible sport participation. She contends that ‘commercial fitness or self-organized exercise like running or biking are more accessible activities for adults leading to high participation rates in such activities today’ (Pilgaard, Citation2012, 157). However, the standardization and commercialization of these sports have also raised concerns about how genuine such sport experiences are and whether the lines between sport and consumer culture have become blurred to an extent where it became questionable whether sport activities still have the same meaning today as was originally intended (Salome, Citation2012).

For this stream of research, a measurement instrument would be valuable to evaluate the extent to which a consumerist attitude exists in sport and it could help to compare attitudes across different sport settings. This way, it becomes possible to determine to what extent consumer culture has become mixed up with different sports and to what extent sport participants have indeed developed a consumerist attitude.

Service quality and the consumerist attitude

A second stream of research in consumerism in sport has been concerned with the management of sport organizations and the question of how to improve consumers’ experiences with and in sport organizations. However, this research approach has merely problematized the influence of consumer culture on sport. Rather, it has sought to improve sport services’ quality and generate more profits in sport (Slack, Citation1998). An overview of such research is provided by Robinson’s (Citation2006) article on customer expectations of sport organizations. She shows that, along with a rise in consumer rights and education of consumers, the expectations towards quality in all sort of products and services in the Western world have increased and that sport organizations are no exception to that. She also notes that sport organizations are most likely not to meet these expectations, which leaves room for improvement (cf. Bodet, Citation2009). Within sport management research, attempts have been made to measure customer satisfaction and how this relates to attendance, customer–organization relationship and loyalty in gyms (Alexandris & Palialia, Citation1999; Bodet, Citation2012; Bolton, Citation1998; Ferrand, Robinson, & Valette-Florence, Citation2010; Hennig-Thurau & Klee, Citation1997; Pedragosa & Correia, Citation2009).

Although these articles provide valuable insights in attitudes and behaviour of sport consumers in gyms, they neither provide any information about whether a consumerist attitude can be found in different sport organizations, nor do they explicate how expectancies around service quality are linked to a consumerist attitude. A measurement instrument could inform researchers about this puzzle. It could help sport managers to understand the attitude of consumers in the fitness and health sector and it could, for example, support them in comparing different fitness clubs on different subdimensions to know what emphasis to put on in each club.

A threat to voluntary sport organizations

Finally, the consumerist attitude has often been described as a possible threat to voluntary sport organizations as it is believed to contrast the traditional values of reciprocity and solidarity that prevail in these organizations (Enjolras, Citation2002; Schlesinger, Egli, & Nagel, Citation2013). Yet, many researchers, policy makers and sport managers believe that this attitude is emerging in voluntary sport organizations as well (Enjolras, Citation2002; Ibsen & Seippel, Citation2010; Lorentzen & Hustinx, Citation2007; Meijs & Hoogstad, Citation2001; Van der Roest et al., Citation2015).

According to Bodet (Citation2009), there is an increasing gap between the expectations that members of voluntary sport organizations have and the offerings in these organizations. First, an increasing need for flexibility urges voluntary sport organizations to change their activities in order to stay attractive to members with a consumerist attitude. Bodet (Citation2009) argues that their activities need to be quickly consumable and Pilgaard (2012) contends that voluntary organizations are indeed in need of creating more flexible structures. Second, the increasing consumerist attitude also urges voluntary sport organizations to improve the quality of their services (Janssens, Citation2011). These changes in voluntary sport organizations are deemed to have fierce consequences (Enjolras, Citation2002) and they are believed to undermine the aforementioned values of solidarity and reciprocity (Schlesinger et al., Citation2013).

Yet, no author has investigated the impact of consumerism on voluntary sport organizations or has evaluated how this attitude actually manifests itself in these organizations. A measurement instrument could therefore assist this stream of research by providing insights in the nature and degree of the consumerist attitude in voluntary sport organizations. Such an instrument is momentarily lacking in the international literature.

Definition and conceptualization of consumerism and the consumerist attitude

The above-described lines of research have all dealt with consumerism in sport organizations, however, a clear definition and a sound conceptualization of consumerism and the consumerist attitude are still lacking.

Consumerism

The definition by Lorentzen and Hustinx (Citation2007) of the ‘member-consumer’ seems particularly useful to define how a sport consumer can be understood. They define this person as ‘an individual who assumes membership will give her access to a product, and that the balance between costs (membership fees) and outcomes will be in her favour. In cases like this, the will to submit to collective goals (what can I do for the association?) is gradually replaced by demands for “products” (what can the association do for me?)’ (Lorentzen & Hustinx, Citation2007, 107).

This definition is quite useful. Yet, Lorentzen and Hustinx (Citation2007) do not elaborate further on the concept of the member-consumer. This leaves much uncertainty about how the attitude of such a person in organizations can be understood. For the conceptualization we therefore have to turn to other streams of literature.

The contradiction between members and consumers very much resembles the contradiction that is central in works on citizen-consumers, as explained by Clarke, Newman, Smith, Vidler, and Westmarland (Citation2007). Here, tensions between collective goals and individual needs are also key components. Therefore, this stream of literature is quite useful to further research on consumerism. In works on citizen-consumer, or consumerism in the public sector, there is much more elaboration on how consumerism relates to (public) organizations. The citizen is seen as a figure that is rooted in ‘liberty, equality and solidarity’ (Clarke et al., Citation2007, 1–2), while the consumer is ‘engaged in economic transactions in the marketplace, exchanging money for commodified goods and services (Clarke et al., Citation2007, 2). The member-consumer can be conceptualized using similar terms.

Choice and voice are key concepts in the literature. Choice, the freedom to choose ways in which services are provided to an individual (cf. PASC, 2005) is translated by public service providers in ‘institutionalized arrangements that provide opportunities to make decisions expressing preferences between a defined menu of options’ (6, 2003, 241). In sport, improved choice could thus mean improved flexibility in sport participation and a greater say in the way sport is provided to the individual (cf. Pilgaard, Citation2012).

The greater say in sport provision is also reflected in the concept of voice, which refers to people becoming ‘less deferential, less trusting, more willing to challenge authority and to make demands’ (Clarke et al., Citation2007, 68). The concept is strongly connected to choice as illustrated by the British Government, ‘Increased choice (or the promise of it) has encouraged people to expect a greater say or even control over service provision. User voice is equally important, however, for public services where a choice of service provider is not feasible’ (PASC, 2008, 6). For sport participants, of course, choosing between service providers is much easier, which gives voice a different connotation. Here, voice is likely to look more like Hirschman’s (1970) classic definition of the concept, which says that ‘the discontented customers or members could become so harassing that their protests would at some point hinder rather than help whatever efforts at recovery are undertaken’ (31).

In sport organizations, the concept of voice is somewhat twofold. For voluntary sport clubs, collective voice opportunities are crucial. After all, democratic decision-making is one of the key features of these organizations (cf. Seippel, Citation2006). However, for commercial sport organizations, opportunities for voice are largely absent. Thus, in both voluntary sport clubs and commercial sport organizations, individual voice can be a challenge as possible tensions might arise due to increasing individual voice possibilities.

Therefore, it would be interesting to relate consumerism to organizational commitment. One could ask the question whether consumerist tendencies, such as an increased need for choice and voice, decrease the commitment of the organizational members. For voluntary sport clubs this would be highly relevant to know, as commitment is an important prerequisite for volunteering and thus an important resource for clubs. In earlier works on organizational commitment, it has already become clear that affective commitment and continuance commitment are important to activate people for a sport organization (Cuskelly, Boag, & McIntyre, Citation1999; Engelberg, Zakus, Skinner, & Campbell, Citation2012; Schlesinger et al., Citation2013).

Consumerist attitude

A closer elaboration on the consumerist attitude is more difficult to make, as there has been very little research on this topic. The translation of the concepts in the previous section to actual attitudes within organizations has merely been made. Within educational studies, there has been a small number of studies that payed attention to the consumerist attitude in organizations. Most notably, Delucchi & Korgen’s (2002) article on consumerism in higher education constructs the consumerist attitude as an attitude due to which students demand services and guaranteed outcomes in return for their tuition fees. In sport organizations, a similar attitude could be found. Bodet (Citation2009, 231) argues that sport consumers ‘want everything immediately, and expect rewarding results with their first attempts with a minimum of effort’.

Overall, the meaning of consumerism and the consumerist attitude has become much clearer when these concepts are considered in the context of public services. However, the concept still lacks clarity in the sport context. Therefore, an empirical conceptualization of consumerism and the consumerist attitude in sport organizations is needed before we turn to the development of the research instrument.

Methods

In order to develop a reliable measuring instrument, the eight steps for scale development described by DeVellis (Citation2003) were followed. These steps are: (1) determining clearly what it is you want to measure, (2) generating an item pool, (3) determining the format for measurement, (4) having the initial item pool reviewed by experts, (5) considering inclusion of validation items, (6) administering items to a development sample, (7) evaluating the items and (8) optimizing scale length.

As stated earlier, an extensive first step was needed to get to the development of the research instrument. Because consumerism in sport is a relatively new topic and the meaning of consumerism in sport organizations is not yet clear, it was necessary to further conceptualize sport consumerism in focus group interviews before developing the scale.

Therefore, data collection consisted of two sequential phases. First, the focus group interviews were used to research participants’ understanding of and meaning attributed to consumerism. Second, a quantitative study was conducted among a group of sport participants in the Netherlands in order to develop a reliable and valid scale for measuring consumerism in sport organizations.

Determination of what is to be measured

As consumerism in sport organizations is a relatively new research topic, it was crucial to decide on the indicators for developing the questionnaire (De Vaus, Citation2002). In order to do so, focus group interviews were conducted to understand the meanings behind consumerist attitudes. According to Morgan (Citation1997), focus groups are a good device for creating survey items, because they ‘provide preliminary research on specific issues in a larger project’ (Morgan, Citation1997, 17). Focus groups were thus used to fill in the first step that DeVellis (Citation2003) prescribes, namely the determination of what is to be measured.

In total, three focus group interviews were organized. Respondents were approached by e-mails sent out to voluntary sport clubs and commercial sport organizations in a large city and a mid-sized town in the middle of the Netherlands. In addition, the author promoted the group interviews on social media outlets such as Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn. In order to encourage people to join, participants had a chance to win a 50-euro gift voucher for a sport equipment store. To gain an understanding of sport consumerism as broad as possible, focus group interviews were organized for sport participants as well as sport administrators and instructors. Two of the three focus groups consisted of sport participants (seven and four respondents, respectively), while one focus group comprised administrators and instructors (seven respondents). The total of eighteen respondents included twelve male and six female respondents, with ages ranging from 21 to 63 (average age: 33.6 years). Their educational level varied from vocational education to higher education, with a majority of respondents being higher educated.

The respondents were asked to fill out a short questionnaire in which they were asked to write down the sport and the organizational setting in which they participated. Respondents were able to fill out up to three different sports and organizations. In total, a number of 20 different sports were mentioned, which can roughly be divided into four categories: ball sports (e.g. soccer, volleyball and basketball), endurance and recreational sports (e.g. running, cycling, skiing, equestrian sports) and exercise sports (e.g. fitness, dancing). These sports were practiced in different organizational settings: voluntary sport club (16 times), commercial sport organization (13 times), unorganized (12 times) and at the workplace (2 times).

The focus group interviews took place in a conference room and the respondents were seated around a table, with the moderator sitting at the head. An assistant moderator was present to record or film the interviews that were fully transcribed by the author. The focus group interviews were semi-structured, using four main questions () and other questions that arose from the discussion. In duration they ranged from 75 to 120 minutes. All respondents participated more or less equally in the group discussions.

Table 1. Questions used during focus group interviews (translated from Dutch).

The focus group interviews were transcribed verbatim. The data then was analyzed and coded in order to be able to identify indicators. This process was done in two phases. The first phase contained a coding process based partly on insights from the literature and partly on open coding. The second phase consisted out of an axial coding process (Boeije, Citation2010) in which a ladder of abstraction (De Vaus, Citation2002) was formed.

First, data that identified a definition of consumerism or consumerist attitudes and of motives for participating in sport were coded as such. Different themes were then coded because they either were recognized as accounts of consumerism as presented in consumerism literature (including that on public service), or because they frequently appeared following an open coding process.

Second, the themes that were derived in the first phase were coded in an axial coding process in order to restructure them. All the codes that were derived in the first phase of coding were reread and coded with a more detailed description in order to create subdimensions that could be used in the ladder of abstraction. This step was deemed necessary for developing questions in the questionnaire.

After having identified the main themes in the open coding process, the axial coding process made clear that the meanings attributed to consumerism in sport organizations by the focus group participants could be reduced to six subdimensions. These six subdimensions are discussed in the results section. In the following paragraphs, the steps that DeVellis (Citation2003) describes are further explained.

Development of the questionnaire

Generation of the item pool

After having completed the focus group analysis, items for a scale were generated on the basis of this analysis and the format of measurement was determined. The subdimensions that were generated in the qualitative part of this study were used to formulate the components of the item pool. For every subdimension, a number of items were formulated, using wording that closely resembled the wording used by respondents in the focus group. The initial item pool consisted of 41 items, divided over the six subdimensions that are presented in the focus group results.

Determination of format for measurement

The format of measurement for all items is a five-point Likert scale, ranging from [completely disagree] to [completely agree].

Review of the initial item pool by experts.

The generated item pool was administered to an expert panel, as DeVellis (Citation2003) suggests. The expert panel consisted of three faculty members and one doctoral candidate with experience in sport research. For all 41 items they were asked to answer three questions. First, the experts were asked to ‘rate how relevant they think each item is to what you intend to measure’. Second, the ‘items’ clarity and conciseness’ were reviewed, and third, the experts were asked to point out ‘ways of tapping the phenomenon that you have failed to include’ (DeVellis, Citation2003, 85–87, emphasis in original). Based on the comments provided by the experts, several items were reworded, two items were omitted from the pool of questions and one question was added yielding a total of 40 questions. After this step was taken, four persons tested the online questionnaire with respect to the clarity of the questions and the routing of the questionnaire. Some of the four persons who carried out this step had research experience, while others did not. Based on this step, some slight modifications in the routing were made and one question was reworded due to poor clarity.

Inclusion of validation items

DeVellis (Citation2003) also recommends that researchers who want to develop new measuring instruments include scales that have already been validated, as this can help the researcher in detecting problems or flaws. The inclusion of validation items can assist in determining the construct validity of a scale. For the consumerism questionnaire, a validation scale on organizational commitment was included.

As argued earlier in this article, organizational commitment is an important factor in the continued existence of sport organizations. For this questionnaire, a modified Dutch version (Jak & Evers, Citation2010) of Meyer, Allen, and Smith’s (Citation1993) scale for organizational commitment (Allen & Meyer, Citation1990) was used. The Dutch version has minor differences compared to the English version, as some negatively formulated items have been rephrased (Jak & Evers, Citation2010, 163–164). Subsequently, slight alterations in the Dutch version were made to make the scale relevant for sport organizations (e.g. the Dutch word for ‘quitting’ is different in an employee context than in a membership context – see for the items). All constructs in the Dutch version of the organizational commitment questionnaire were administered in order to assure comparability within the Dutch context, although previous studies in sport organizations have found little support for continuance commitment (Cuskelly et al., Citation1999; Engelberg et al., Citation2012).

Table 3. Factor loadings and internal consistency for organizational commitment.

Administration of items to a development sample

The scale was administered to a development sample through an online questionnaire (Couper, Citation2008). The questionnaire was administered in August 2013 and was open to respondents for a period of three weeks. In the survey, there was a different routing for sport participants with and without a sport organization, as some questions in the scale are specifically meant for participants in sport organizations. The validation items were only gathered for sport participants in sport organizations, as these questions measure organizational commitment. The questionnaire was sent out to different sport participants in the personal and professional network of the researcher, where snowballing techniques were applied to obtain as many as respondents as possible. In addition, national sport organizations promoted the questionnaire on their websites, in newsletters and on online social media. In the announcement sport participants were asked to fill out the questionnaire.

The web survey yielded a response of 303 fully completed questionnaires, which should be sufficient (DeVellis, Citation2003; Nunnally & Bernstein, Citation1994). The final steps that DeVellis suggests in his model (evaluation of the items and optimizing the scale length) will be discussed in the results section below.

Results

In this section, the outcomes of both the qualitative and the quantitative study are presented. First, the qualitative results are discussed using direct quotes from the focus group interviews. These quotes clearly illustrate how meanings of sport consumerism are constructed. Second, the quantitative results section will present the outcomes of the statistical analyses that were performed.

Qualitative results

Choice

One of the most important subdimensions of consumerism found in the literature was choice, meaning the ability to choose between different organizations or to choose how a service is delivered. In the focus group interviews, choice was also one of the main themes. First of all, the respondents paid considerable attention to the flexibility that can be found in a consumerist way of participating in sport. Meanings given to this subdimension included positive accounts of people underlining their autonomy in practicing their sport, but also more negative accounts of sport participants being independent in a very self-centered way. The following quote illustrates the independence that was found among some focus group participants.

I would like to be able to be exercising within, say, half an hour. And maybe now I am up to it, but tomorrow I might not be and the day after tomorrow also not, but the next day I will be up to it again. (Respondent11, tennis player, 24, male)

The autonomy of consumers making their own decisions is closely connected to the feeling that a consumer does not want to be attached to any obligations. This relates to the observation by Gabriel and Lang (Citation2006) that a typical consumer is not really embedded in a community and can be understood in the context of societal trends such as individualization and informalization. It emerges from the focus groups that a modern sport consumer, so it seems, likes to participate without having to depend too much on others.

Detachment

These noncommittal forms of sport participation are among the most typical forms of consumerism that comes to mind when respondents in the focus group describe a consumerist attitude among sport club members. Interestingly, meanings related to detachment emerge both with respondents who describe themselves as consumers and those who describe other people as consumers. One participant in a voluntary sport club stated:

For example, I coordinate the club’s cafeteria, and there are always too few volunteers. That means that sometimes we have to close the kitchen. And people can get very upset about that. (…) And I do invite them to take a role in the kitchen themselves…but that is something they don’t want to do. (Respondent7, football volunteer, 24, female)

From the perspective of the consumer, this view is confirmed, as volunteering is not something a typical sport consumer might do. Some respondents in the focus group interviews indicated that they normally check whether membership in a certain sport organization is free of obligations such as volunteering. For some people volunteering in a sport club is really out of the question. However, volunteering is not the only obligation that is undesirable from a consumerist perspective. One of the things that was stated very often during the focus group interviews was that sport consumers want to have sport activities without any strings attached. This includes the flexibility of choice when to practice sport without additional obligations, but respondents also stated that the genuine consumer would not like to be fixed to any contract.

Unsociability

Another aspect of the fact that consumers would not like too many obligations in their sport activities is the limited presence of social contact during sport activities. The discussion in the focus groups showed that being a consumer also means behaving quite individually, although there will always be some social contact. Exemplary of unsocial consumerist attitudes, according to one respondent, is the way people interact in health clubs.

I think that the gym is the ultimate place to go “shopping”, it is rather impersonal for most people. I do meet a lot of people, I do chat with them, but that is it. (Respondent7, runner, 65, male)

Health and fitness centres are seen as ‘impersonal’ and as an ultimate place for ‘shopping’. Many respondents in the focus groups stated that the less social an activity is, the more likely it is to be a consumerist activity. Schlesinger and Nagel (Citation2015) have acknowledged that the members of voluntary sport clubs that support sociability consistently show higher levels of commitment towards the club.

Transaction

For the feeling of being a consumer in sport, many respondents think that some kind of transaction and a financial aspect should be involved. Many respondents use words like ‘buying’ and ‘paying’ to describe their view of the sport consumer, as the next quote illustrates.

I think that that is a typical example of a sport consumer, just somebody who sees it and thinks: “I will buy that” without having any commitment, someone who thinks: “I pay for it and that’s it”. (Respondent1, squash player, 27, male)

Consuming the sport activity and seeing it as a financial transaction rather than an activity that is jointly organized by the participants was a key difference that occured in the focus groups. Additionaly, it seems that these kind of transaction-like acts also focus on the outcomes of the activity. For example, health motives are more and more a reason to participate in both commercially and voluntarily organized sport (Seippel, Citation2006; Van‘t Verlaat, Citation2010). This focus on health also means that service quality becomes more important, as becoming or staying fit requires specific medical knowledge.

Service quality

According to the respondents in the focus group interviews, expectations of service mainly concern quality. If a consumer buys any type of service in exchange for money, a certain quality standard is required of that organization. First of all, according to the respondents, there are some basic demands that anyone in a sport organization has. Many respondents state that safety is an important responsibility of any sport organization, even if that organization is a traditional voluntary sport club. Alexandris and Palialia (Citation1999) also found high scores for the importance of clean and attractive environments in health clubs. However, the respondents also find that in a more consumerist mode of practicing sport, the demands of the sport participant go beyond these basics. Demands in quality are divided into three main categories. First, the respondents indicate that the staff of a sport organization should have sufficient knowledge to help them during their sport activities. A second point in which consumers expect quality from organizations are the facilities themselves. Both the sport-related and the non-sport facilities are seen as important prerequisites for a good consumer experience. Or, as one of the respondents put it: ‘What you want, basically, is good coffee’. The third aspect that emerged in the focus group was high quality of the sport offering. Although this seems obvious, respondents underline the fun aspect of practicing sport from a consumerist point of view.

The above demands stemming from the consumerist perspective may seem like demands that any sport participant would have. However, the respondents in the focus group interviews clearly made a distinction between a consumerist perspective and a traditional perspective. Some respondents think that from a traditional perspective, members of sport organizations can be less demanding, or can even cherish low levels of quality. One of the respondents explicitly illustrated this:

Everything that has to do with these terms: ‘professionalization, service delivery, customers, commercial, customer-friendliness…’ I just do not want those things! I just want it to be an amateur football club that is being led by people who like to do so and who are volunteering in the bar. If my club starts to talk about becoming more customer-friendly… I do not want that. (Respondent15, football player, 26, male)

Criticism

Respondents clearly link negative attitudes to the presence or absence of quality in the services offered to members of any sport organization. They indicate that there are two different reactions consumers can have when they are unhappy about the services that are provided. Many respondents describe typical responses by consumers as ‘nagging’ or ‘complaining’. The other response described is exit behaviour. According to some respondents, consumer behaviour in sport organizations is caused by the fact that people do not know how to resolve dissatisfaction, whereas in a traditional club this was much easier.

Quantitative results

In this section the results of the quantitative study are presented. For the development of the scale, a factor analysis and a reliability analysis on the Consumerism in Sport Organisations (CSO) instrument and organizational commitment were carried out.

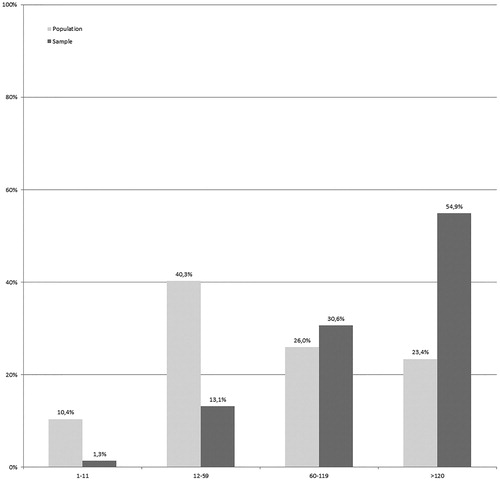

The sample of the study consisted of 45.80% women and 54.20% men, and the average age was 32.06. About 218 respondents are active in voluntary sport clubs, 41 in commercial sport centres, 28 are individual participants, and 16 participate in another organization (for example in school or the company they work for). 215 respondents reported that their participation in sport takes place in a team or in a fixed group. As can be seen in , active sport participants are overrepresented in the sample. Furthermore, as the survey is intended for sport organizations, the share of people active in voluntary sport clubs is also higher than the average in the Dutch sport participation population, while individual sport participants are underrepresented (cf. Hover, Romijn, and Breedveld, Citation2010).

Factor analysis and reliability analysis CSO scale

In order to evaluate the number of latent variables in consumerism in sport organizations, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was carried out. First, six items with a non-response rate above 5% were dropped from further analysis. A principal axis-factoring analysis of the remaining 34 items was performed in SPSS 21 (Chicago, IL) to evaluate the factor structure of the administered items. Direct oblimin rotation was used, because factors were expected to intercorrelate. Based upon the qualitative findings, the number of factors was set at six. KMO (.86) and Bartlett’s test (p < .05) yielded satisfactory results. Items with communalities lower than .35 were dropped, which resulted in deletion of four items. The remaining 30 items were analyzed in a new factor analysis (see ). The results suggest that a six-factor structure is indeed suitable for the measurement of consumerism in sport organizations, as there were six factors with an eigenvalue higher than one. For the factor loadings, a cut-off of .35 was used (Hair, Tatham, Anderson, & Black, Citation1998). Three items were deleted because they did not make the cut-off, or because they loaded on two factors. Closer inspection of these items revealed that they lacked clarity. provides a full overview of the remaining factor loadings on each of the six items, which account for 63.78% of the variance.

Table 2. Factor loadings and internal consistency for consumerism in sport organizations.

The six factors differed slightly from the results in the focus group interviews, because the choice subdimension appeared to deal with independence and the questions in the transaction subdimension were not recognized as a factor. An explanation for this might be a low tendency among sport participants to compare products and organizations, as three items in this subdimension had high non-response rates. The service quality subdimension was separated into a service quality and a coping subdimension, in which coping related to the reaction when a certain level of quality was not delivered by the sport organization. Finally, the criticism factor mainly dealt with exit behaviour, while the positive accounts of criticism were part of the detachment factor as reversed item. The factors that are part of CSO are: independence, detachment, unsociability, service quality, coping and exit behaviour. These factors were all analyzed using a reliability analysis. therefore also reports Cronbach’s α (DeVellis, Citation2003). Almost all factors were found to be internally consistent with Cronbach’s α, ranging between .67 and .86. The coping subdimension was found to be too inconsistent for further use. As this factor was already a subdimension of the service quality factor, it was decided not to include this factor in further analyses.

Construct validity

To evaluate the validity of the CSO scale, the previously mentioned validation items were also analyzed using EFA and reliability analysis techniques. Principal axis factoring (eigenvalue set at 1) with direct oblimin rotation was used for organizational commitment. KMO (.88) and Bartlett’s test (p < .05) indicated that factor analysis was suitable for the data. Five items were dropped because they produced non-response rates of over 5% or communalities under .35. The new run of the factor analysis resulted in a 2-factor structure for organizational commitment. Two items were dropped because of low factor loadings, resulting in a confirmation for affective and normative commitment in sport organizations, accounting for 84.20% of the variance. As was expected, continuance commitment did not emerge as a latent variable (cf. Cuskelly et al., Citation1999; Engelberg et al., Citation2012). reports factor loadings and Cronbach’s α for organizational commitment.

Finally, to evaluate whether the CSO scale is valid for measuring consumerist attitudes in sport organizations, the relationship between the CSO factors and the two organizational commitment factors was analyzed. First, in the descriptive statistics for the separate factors are given. It shows that most factors have scores around the mathematical mean of the scale, although service quality has a score that is considerably higher than the other factors.

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics for factors in CSO and OC.

presents a correlation matrix of scores on all CSO factors and organizational commitment. Here it is found that almost all CSO factors significantly intercorrelated, while at the same time almost all CSO factors had a significant negative correlation to organizational commitment. None of the intercorrelations were problematically high, indicating good discriminant validity. Detachment and exit behaviour were negatively correlated with affective commitment, which relates well to earlier studies about commitment in sport organizations (cf. Cuskelly, Harrington, & Stebbins, Citation2002). The service quality subdimension seems to be problematic in the sense that it does not correlate well with other CSO factors, indicating low convergent validity. It has no significant correlation with independence and has relatively low correlation coefficients with all the other factors in CSO. The factor is also uncorrelated with normative commitment. The implications of the findings on this factor will be considered in the discussion section.

Table 5. Correlations among factors of CSO and OC.

Usability of the CSO scale

In order to demonstrate the usability of the CSO scale, it would be interesting to see what differences can be found when the respondents’ characteristics are compared. In doing so, a first demonstration of what can be researched using the CSO scale is given. An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the level of consumerism and commitment between men and women. No significant differences in the scores for all dimensions in both the CSO scale and the OC scale were found. However, for the service quality subdimension in the CSO scale there was a significant difference; women tend to rate service quality higher than men (see ). Furthermore, ANOVA-analyses for each subdimension revealed that there are significant differences between age groups (<25, 25–35, >35) in the Independence [F (2, 245) = 10.38, p = .00], Unsociability [F (2, 213) = 3.81, p = .02], Exit [F (2, 223) = 3.83, p = .02] and Normative Commitment [F (2, 224) = 5.40, p = .01] subdimensions. Post hoc tests using the Bonferroni correction indicated that the mean for Independence for the under 25 years group (M = 2.60; SD =0.74) significantly differs from the 25–35 years group (M = 2.90; SD =0.74) and the over 35 years group (M = 3.16; SD =0.80), the mean for unsociability for the under 25 years group (M = 2.06; SD =0.73) significantly differs from the over 35 years group (M = 2.39; SD =0.65), the mean for Exit for the under 25 years group (M = 2.77; SD =0.90) significantly differs from the over 35 years group (M = 3.17; SD =0.76), and the mean for Normative Commitment for the 25–35 years group (M = 2.17; SD =1.06) significantly differs from the under 25 years group (M = 2.65; SD =0.99) and the over 35 years group (M = 2.62; SD =1.06). Finally, an independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the level of consumerism and commitment between participants in voluntary sports clubs and participants in commercial sports organizations. For all subdimensions of CSO and OC, there was a significant difference; sport participants in a commercial sport organization tend to score higher on consumerism and lower on commitment than sport participants in a voluntary sport club (see ).

Table 6. Independent samples t-tests for gender and type of organization.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this article was to conceptualize the consumerist attitude in sport organizations and to develop a reliable instrument for the measurement of this concept. Three focus group interviews and quantitative tests of the concept have resulted in the CSO scale. This scale is made up of five subdimensions that represent the consumerist attitude in sport organizations: (1) independence, (2) detachment, (3) unsociability, (4) service quality and (5) exit. Construct validity tests and comparisons with a validated scale (organizational commitment) show that the CSO scale is a reliable and valid scale that can be used by researchers, policy makers and sport managers. The final questionnaire can be found in the Appendix at the end of this article.

Considering the attention that was present in literature and practice, this instrument adds to the understanding of how the consumerist attitude relates to sport organizations and it contributes to a more nuanced view of the implications of such an attitude in sport. From a theoretical perspective, the calculative and impatient attitude that is described by scholars like Lorentzen and Hustinx (Citation2007) and Bodet (Citation2009) needs to be qualified. Indeed, aspects of these attitudes are apparent in the five subdimensions of the CSO scale, but the results also show that the consumerist attitude entails more than that. In the literature, the social aspects of consumerism are merely discussed.

However, participation in sport organizations is most often a social activity (cf. Seippel, Citation2006). Regardless whether one participates in voluntary sport clubs or commercial sport organizations, participation in sport means meeting others or competing with them. The consumerist attitude, however, is deemed to contrast the social nature of participating in these organizations.

The slightly different nature of participation in sport organizations as opposed to most public organizations that have been discussed in the theoretical framework also means that the implications of ‘choice’ and ‘voice’ are different in sport organizations. Sport participants already have a wide range of opportunities to choose their most favourable provider and the democratic nature of voluntary sport organizations also makes it possible to influence the organization. Still, choice and voice are resembled in the CSO scale. The independence and exit subdimensions exhibit aspects of choice, while the detachment and the exit subdimension show attitudes of voice.

As might have been expected, consumerism and commitment to an organization negatively correlate. What is interesting however is that not all dimensions of consumerism have a (strong) negative relationship with commitment. For example, service quality is hardly related to the commitment one has to the organization suggesting that consumerism is not in all cases a negative attitude in relation to sport organizations (cf. Schlesinger et al., Citation2013; Seippel, Citation2006).

Further, one of the major findings of this study is the big difference that is found in the attitudes that members in voluntary and in commercial sport clubs have towards their organization. Unlike the expectation that these two worlds are rapidly converging and that all sorts of hybrid organizations arise in which members do not know the difference between voluntary and commercial sport organizations (cf. Bodet, Citation2009), this study suggests that they are still two separate worlds.

Finally, the quantitative results of this study indicate that women tend to rate service quality higher than men. The intersection of consumerism and gender therefore possibly deserves more attention. Especially when consumerism is viewed as a cultural practice, it is worthwhile to further investigate the concepts of consumerism, accessibility and gender aspects (cf. Bodet, Citation2009; Pilgaard, Citation2012). This particular finding also has implications for sport organizations that serve a high number of women. For sport organizations that exclusively focus on women (for example the worldwide Curves franchise), it seems appropriate to give considerable interest to this aspect in their sport activities. Through applying the CSO scale, sport managers can improve the performance of their organization.

This study can also contribute to other practical applications that have been discussed in the review of the literature. For example, the CSO scale can be applied in sport organizations to improve service features, or it can be employed in large-scale surveys to determine the level of consumerism in a particular group of sport participants. Finally, individual organizations can use the scale to know on which dimensions of consumerism they should focus.

Of course, this study also has limitations. The study should be seen as a first endeavour at conceptualizing consumerism in sport organizations and it is the first measurement instrument for this concept. As such, the dimensions might profit from becoming leaner and some items might prove themselves to be redundant in the future. An improved instrument should thus be retested with a focus on downsizing the survey. Another limitation was the fact that mostly very active sport participants filled out the questionnaire. These people might either be more involved in sport organizations because of their high activity levels, or they might only focus on their sport participation and thus show high consumerist levels. The large middle group of people who have a regular participation in sport are underrepresented in this sample. Future research should focus on an improved generalizability of the sample.

Future research

Apart from the generalizability, there are a number of alternative options for future research using the CSO scale. One important possibility is to extent this questionnaire to a group of people from whom a lot is expected in the voluntary sport setting. Youth members take up a large majority of sport participants in Dutch voluntary sport clubs, as they do in other countries. The parents of these members are responsible for a lot of voluntary activities in these organizations. It is worthwhile to further investigate the attitudes these parents have towards these sport organizations. After all, the clubs largely rely on them.

In addition, it is interesting to conduct further research on the development of sport organizations, both non-profit and profit. Do they indeed change as an outcome of consumerist attitudes in their organizations, as is suggested by Ibsen and Seippel (Citation2010)? And how does the interplay of consumerist attitudes and organizational arrangements exactly work? Do sport organizations adapt to consumerist attitudes, or do people develop consumerist attitudes because of the way their clubs are organized? The truth is probably in the middle and the CSO scale can assist researchers in determining these attitudes in sport organizations.

To conclude, the CSO scale is a useful instrument to measure consumerist attitudes in sport organizations. Further improvement of the scale can be obtained by testing it in a large-scale survey of sport participants. A confirmatory factor analysis can then further validate the scale for future use in sport organizations.

Notes on contributor

Jan-Willem van der Roest is a researcher at the Mulier Institute, Utrecht, the Netherlands. His PhD thesis, which he defended at Utrecht University in December 2015, deals with the way Dutch voluntary sport clubs react to a proposed consumerist attitude among their members.

Disclosure statement

The author reports no conflicts of interest. The author alone is responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Alexandris, K., & Palialia, E. (1999). Measuring customer satisfaction in fitness centres in Greece: an exploratory study. Managing Leisure, 4, 218–228. doi: 10.1080/136067199375760.

- Allen, N.J., & Meyer, J.P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63, 1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x.

- Beal, B., & Smith, M.M. (2010). Maverick' s: Big wave surfing and the dynamic of 'nothing' and 'something'. Sport in Society, 13, 1102–1116. doi: 10.1080/17430431003780047.

- Bodet, G. (2009). Sport participation and consumption and post-modern society: From Apollo to Dionysus? Loisir Et Société. Society and Leisure, 32, 223–241.

- Bodet, G. (2012). Loyalty in sport participation services: An examination of the mediating role of psychological commitment. Journal of Sport Management, 26, 30–42. doi: 10.1123/jsm.26.1.30.

- Boeije, H. (2010). Analysis in qualitative research. London: Sage.

- Bolton, B. (1998). A dynamic model of the duration of the customer?s relationship with a continuous service provider: The role of satisfaction. Marketing Science, 17, 45–66.

- Celsi, R.L., Rose, R.L., & Leigh, T.W. (1993). An exploration of high-risk leisure consumption through skydiving. Journal of Consumer Research, 20, 1–23. doi: 10.1086/209330.

- Clarke, J., Newman, J., Smith, N., Vidler, E., & Westmarland, L. (2007). Creating citizens consumers. Changing publics and changing public services. London: Sage.

- Couper, M.P. (2008). Designing effective web surveys. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Cuskelly, G., Boag, A., & McIntyre, N. (1999). Differences in organizational commitment between paid and volunteer administrators in sport. European Journal of Sport Management, 6, 39–61.

- Cuskelly, G., Harrington, M., & Stebbins, R.A. (2002). Changing levels of organizational commitment amongst sport volunteers: A serious leisure approach. Leisure/Loisir, 27, 191–212. doi: 10.1080/14927713.2002.9651303.

- De Vaus, D. (2002). Surveys in social research (5th ed.). London: Routledge.

- DeVellis, R.F. (2003). Scale development. Theory and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Edwards, B., & Corte, U. (2010). Commercialization and lifestyle sport: Lessons from 20 years of freestyle BMX in Pro-Town, USA. Sport in Society, 13, 1135–1151. doi: 10.1080/17430431003780070.

- Engelberg, T., Zakus, D.H., Skinner, J.L., & Campell, A. (2012). Defining and measuring dimensionality and targets of the commitment of sport volunteers. Journal of Sport Management, 26, 192–205. doi: 10.1123/jsm.26.2.192.

- Enjolras, B. (2002). The commercialization of voluntary sport organizations in Norway. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 31, 352–376. doi: 10.1177/0899764002313003.

- Ferrand, A., Robinson, L., & Valette-Florence, P. (2010). The intention-to-repurchase paradox: a case of the health and fitness industry. Journal of Sport Management, 24, 83–105. doi: 10.1123/jsm.24.1.83.

- Gabriel, Y.,. & Lang, T. (2006). The unmanageable consumer: Contemporary consumption and its fragmentations (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

- Giulianotti, R. (2005). Sport spectators and the social consequences of commodification: critical perspectives from Scottish football. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 29, 386–410. doi: 10.1177/0193723505280530.

- GfK (2013). Sportersmonitor 2012. Arnhem: NOC*NSF.

- Hair, J.F., Tatham, R.L., Anderson, R.E., & Black, W. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.) London: Prentice-Hall.

- Harvey, J., & St-Germain, M. (1998). Commodification, globalization and the Canadian sports industry. Avante, 4, 90–112.

- Hennig-Thurau, T., & Klee, A. (1997). The impact of customer satisfaction and relationship quality on customer retention: a critical reassessment and model development. Psychology and Marketing, 14, 737–764. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6793(199712)14:8<737::AID-MAR2>3.0.CO;2-F.

- Horne, J. (2006). Sport in consumer culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hover, P., Romijn, D., & Breedveld, K. (2010). Sportdeelname in cross national perspectief: benchmark sportdeelname op basis van de Eurobarometer 2010 en het International Social Survey Programme 2007 [Sport participation in cross-national persepective: benchmark sport participation based on the Eurobarometer 2010 and the International Social Survey Programme 2007]. Hertogenbosch: W.J.H. Mulier Institute.

- Ibsen, B., & Seippel, Ø. (2010). Voluntary organized sport in Denmark and Norway. Sport in Society, 13, 593–608.

- Jak, S., & Evers, A.V.A.M. (2010). Een vernieuwd meetinstrument voor organizational commitment [A renewed measuring instrument for organizational commitment]. Gedrag En Organisatie, 23, 158–171.

- Janssens, J.W. (2011). De prijs van vrijwilligerswerk. Professionalisering, innovatie en veranderingsresistentie in de sport [The price of volunteering. Professionalization, innovation and resistance to change in sport]. Amsterdam: HvA Publications.

- Llopis-Goig, R. (2014). Sports participation and cultural trends. Running as a reflection of individualisation and post-materialism processes in Spanish society. European Journal for Sport and Society, 11, 151–170. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2014.11687938.

- Lorentzen, H., & Hustinx, L. (2007). Civic involvement and modernization. Journal of Civil Society, 3, 101–118. doi: 10.1080/17448680701554282.

- Meijs, L.C.P.M., & Hoogstad, E. (2001). New ways of managing volunteers: Combining membership management and programme management. Voluntary Action, 3, 41–61.

- Meyer, J.P., Allen, J.A., & Smith, C.A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 538–551. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.78.4.538.

- Moor, L. (2007). Sport and commodification. A reflection on key concepts. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 31, 128–142. doi: 10.1177/0193723507300480.

- Morgan, D.L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research (2nd ed.). London: Sage Publications.

- NOC*NSF (n.d.). Proeftuinen Nieuwe Sportmogelijkheden. Het programma [Experimental garden New Sport Opportunities]. Retrieved from: http://www.nocnsf.nl/cms/showpage.aspx?id =5684.

- Nunnally, J.C.,. & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Pedragosa, V., & Correia, A. (2009). Expectations, satisfaction and loyalty in health and fitness clubs. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 5, 450–464. doi: 10.1504/IJSMM.2009.023371.

- Pilgaard, M. (2012). Flexible sports participation in late-modern everyday life. Odense: Ph.D. Thesis University of Southern Denmark.

- Robinson, L. (2006). Customer Expectations of Sport Organisations. European Sport Management Quarterly, 6, 67–84. doi: 10.1080/16184740600799204.

- Salome, L.R. (2012). Indoorising the outdoors: Lifestyle sports revisited. ‘s-Hertogenbosch: BOXPress.

- Sassatelli, R. (2010). Fitness culture: Gyms and the commercialisation of discipline and fun. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schlesinger, T., Egli, B., & Nagel, S. (2013). ‘Continue or terminate?’ Determinants of long-term volunteering in sports clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13, 32–53. doi: 10.1080/16184742.2012.744766.

- Schlesinger, T., & Nagel, S. (2015). Does context matter? Analysing structural and individual factors of member commitment in sport clubs. European Journal for Sport and Society, 12, 53–77. doi: 10.1080/16138171.2015.11687956.

- Seippel, Ø. (2006). The meanings of sport: Fun, health, beauty or community? Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics, 9, 51–70.

- Slack, T. (1998). Studying the commercialization of sport: The need for critical analysis. Retrieved on January, 23, 2015 from: http://physed.otago.ac.nz/sosol/v1i1/v1i1a6.htm.

- Smith Maguire, J. (2001). Fit and flexible: The fitness industry, personal trainers and emotional service labour. Sociology of Sport Journal, 18, 379–402. doi: 10.1123/ssj.18.4.379.

- Van der Roest, J., Vermeulen, J., & Van Bottenburg, M. (2015). Creating sport consumers in Dutch sport policy. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7, 105–121.

- Van’t Verlaat, M.N. (2010). Marktgerichte sportbonden: een paradox? [Market-oriented sport confederations: a paradox?] Oisterwijk, Netherlands: BOXPress.