Abstract

The popularity of eSports has skyrocketed recently, prompting increasing academic attention. However, reflecting the male-dominated reality of the eSports industry, most research is focused on men. Decades of research on gender in the context of technology and computer gaming present a valid cause for concern regarding how women and other minority individuals in these settings have been and remain oppressed. This article presents a traditional narrative review of how the theoretical concept of hegemonic masculinity is used to understand gendered power inequalities in eSports in the research literature. The review reveals that research that focuses on gender and eSports revolves around three main themes: (1) issues of the construction of masculinity, (2) online harassment, and (3) negotiations of gendered expectations. Based on a discussion of gendered power inequalities within these themes, the review concludes that although eSports and traditional sports are clearly different, they discursively link masculinity, athleticism, and competition very similarly. This has significant implications for women and minority players, which in turn calls for more research on how masculinity is regaining dominance despite the increasing participation of girls and women within eSports.

Abbreviation list:

ESA - Entertainment Software Association

LAN - Local Area Network

Introduction

Since emerging in the 1990s, the popularity of eSports – organised competitive gaming – has grown enormously in recent years. Indeed, Newzoo, a global games market research publisher, predicted that the eSports industry’s income would surpass the billion-dollar mark by 2020, with 495 million spectators worldwide (Rietkerk, Citation2020). Unlike traditional sports, in which men are often considered to have a physical advantage over women, physical attributes are unrelated to high performance in eSports, allowing both men and women to compete in the same events (Shen et al., Citation2016; Paaßen et al., Citation2017). According to Hemphill (Citation1995), "Cyberspace holds out the possibility that new forms of sport participation and sociality can be created in terms of game-making, game-playing, and norm-making within games" (p. 58). However, in terms of gender issues related to sexism and exclusion, eSports is no exception (e.g. Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018; Ratan et al., Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2012). Indeed, the eSports industry is heavily male-dominated, with women representing a lower proportion of participants, fans, and leaders (Entertainment Software Association [ESA], Citation2018). Studies show that women comprise 35% of eSports players (Interpret, Citation2019), but only 5% of professional players (Hilbert, Citation2019), which means that women players rarely compete at the topmost level of eSports.

Reflecting on the lack of women in eSports, research has primarily focused on male participants. Therefore, it is important to map and examine factors that contribute to the lower proportion of women within eSports environments. Decades of research on gender in relation to technology and computer gaming present ample reason for concern regarding how women and other minorities have become and remain culturally, socially, and economically repressed (Jenson & de Castell, Citation2011; Citation2013; Citation2015). Factors like professionalisation, marketing, and entrepreneurialism in digital gameplay also contribute to marginalisation in this field (Jenson & de Castell, Citation2018). These factors are increasingly apparent in eSports activities, as they represent a major cultural shift from casual gamers who play just for fun to full-time professional "players" who compete for a living (Jenson & de Castell, Citation2018).

It is important to note that the discussion of gender and eSports is constructed within larger cultural and research discussions about gender, gameplay, and technology. In a review of international research on gender and technology spanning three decades, Jane Abbiss (Citation2008) suggests that accounts of pervasive gender disparities in computer access, use, and behaviours have contributed to the perception that computing is a masculine practice. Other scholars have claimed that one reason for many women deliberately opposing involvement in masculinised technologies like computers is that it challenges their feminine identities and that these technologies have been classified as practices suitable for men (see Cockburn, Citation1992; Wajcman, Citation1991; Schofield, Citation1995).

Massanari (Citation2017) characterised video games as part of a wider, toxic techno-culture that depends on "an othering of those perceived as outside the culture … and a valorization of masculinity masquerading as a particular form of 'rationality'" (p. 5). Furthermore, Taylor (Citation2008) described a web of stereotypical and sexualized practices, from promotion of video games to portrayal of male and female characters within the games (see also Behm-Morawitz Citation2014Citation;Ivory Citation2009; Lynch et al., Citation2016). Therefore, as Jenson and de Castell (Citation2018) argued hegemonic masculinity is supported and valorised through such techno-cultural communities to "ideologically legitimate the global subordination of women to men" (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005, p. 832). Similarly, Taylor (Citation2012) suggested that eSports players reflected the characteristics of traditional athletic masculinity, overlooking the focus on physical abilities.

Utilising a traditional narrative review approach to current academic research conducted on gender and eSports, this article explores the use of the concept of hegemonic masculinity in the eSports literature. More specifically, the review addresses the following research question: How is the theoretical concept of hegemonic masculinity used in the literature to understand gendered power inequalities in eSports?

First, a thematic analysis is used to identify the most common themes in research focused on gender and eSports. Following this process, the resulting themes are presented, and the main findings in this field of study are described. Finally, how the gendered inequalities and power relations found within these themes can be said to align with hegemonial forms of masculinity and power commonly found in traditional sports is discussed.

However, since the concept of hegemonic masculinity has been primarily used to study masculinity; femininity still remains under-conceptualised in gender research (Budgeon, Citation2014; Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005). Therefore, this review adopt an alternative interpretation of hegemonic masculinity provided by Mimi Schippers (Citation2007), presented in the following section.

Theoretical framework: hegemonic masculinity

Since proposed by Raewyn Connell (Citation1987;Citation1995), the concept of "hegemonic masculinity" has been a major component of the growing field of critical masculinity studies. Within a broad range of disciplines, it has proven to be essential to the understanding of masculinities and how unequal gender relations are legitimated worldwide (Messerschmidt, Citation2019). Connell (Citation1995) defined hegemonic masculinity as the "configuration of gender practice that embodies the currently accepted answer to the problem of the legitimacy of patriarchy, which guarantees (or is taken to guarantee) the dominant position of men and the subordination of women" (p. 77). Despite being formulated almost three decades ago, Messerschmidt (Citation2019) argues that Connell’s original focus on the legitimisation of unequal gender relations is still relevant in the field of critical masculinity research.

Addressing the role of hegemonic masculinity in sports, Connell (Citation1987) asserted that "in Western countries…images of ideal masculinity are constructed and promoted most systematically through competitive sports" (pp. 84–85). Studies of traditional sports indicate that sporting spaces are typically characterised by male dominance and masculine hegemony, resulting in discrimination, sexism, and the marginalisation of women as participants, leaders, and fans (e.g. Bryson, Citation1987; Walker & Sartore-Baldwin, Citation2013).

Connell’s (Citation1987; Citation1995) original work was heavily concentrated around hegemonic forms of masculinity with just a few mentions of femininity, and then only based on its connection to masculinity. Since all forms of femininity are formed in relation to male domination, there is no place for hegemonic femininity, Connell (Citation1987) argues. Instead, Connell (Citation1987) presents the concept of "emphasized femininity," which is created in opposition to hegemonic masculinity and is centred upon internalised subordination and subjugation in connection with dominant forms of masculinity. After being subjected to a number of serious criticisms, misconceptions, and misapplications, Connell and Messerschmidt (Citation2005) reformulated the concept of hegemonic masculinity which also included a more complex model of gender hierarchy and highlighted the agency of women. Despite this, some authors claim that femininity remains under-conceptualised in the field of gender studies (Paechter, Citation2018; Budgeon, Citation2014; Schippers, Citation2007; Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005).

The heterosexuality-based co-construction framework proposed by Mimi Schippers (Citation2007) provides a valuable alternative to emphasised femininity. Building on Connell’s (Citation1987; Citation1995), publications, Schippers positions the relationality of masculinity and femininity at the forefront of thinking about the validity of gender hegemony. According to Schippers (Citation2007, p. 90), the "qualities members of each gender category should and are assumed to possess are contained within the interpretations of organised gendered relationships; therefore, it is in the idealized quality content of the categories ‘man’ and ‘woman’ that we find the hegemonic significance of masculinity and femininity." Thus, conceptualising the relationship between masculinity and femininity becomes central in order to understand the validity of gender hegemony, according to Schippers.

This alternative model of hegemonic masculinity allows the study of various constructions of masculinity and femininity and their influences for gender hegemony by focusing on relationality between masculinity and femininity (Schippers, Citation2007). As a result, Messerschmidt et al. (Citation2020) argue any emerging constructions of femininities become essential to comprehending historical variation in emphasised femininities as well as the reproduction of gender inequality. Recent feminist research suggests that the dominant construction of gender among young women in the global North today is associated with the "heterosexy athlete" – an identity connected with beauty and heterosexual attractiveness combined with gender traits like personal independence, ambition, competitiveness, and athleticism – rather than the embodied practices like submissiveness, docility, and passivity represented in Connell’s description of emphasised femininity (Paechter, Citation2018; Budgeon, Citation2014; McRobbie, Citation2009). However, Messerschmidt (Citation2020) argues that gender hegemony remains relevant as no constructions of hybrid femininity yet have resulted in a restructuring or breakdown of hierarchical gender relations.

Method: a traditional narrative review

Procedure and sample

A list of keywords was used to direct the identification of relevant research on eSports and gender: eSports, competitive gaming/video games, electronic/virtual/digital sports, gender, male/female/men/boys/girls, masculinity, and femininity. These were used to search Google Scholar, EBSCOhost, Scopus, and Web of Science. The search was restricted to peer-reviewed English and Scandinavian language papers, anthologies, and doctoral dissertations published from 2006 to 2020. The search was conducted between January 2020 and May 2020. The initial searches returned 3980 results for Google Scholar, 1462 results for EBSCOhost, 305 results for Scopus, and 220 results for Web of Science. However, most of the results did not focus on both eSports and gender as the main research theme.

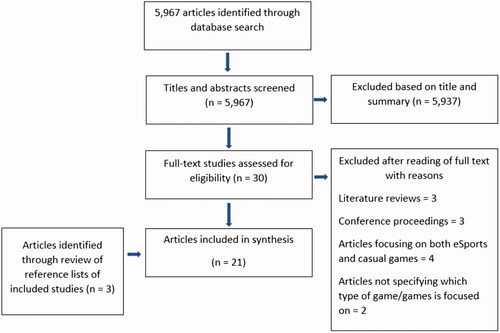

Therefore, further measures were utilised to identify relevant papers. Papers referring to reviews, citations, and conference proceedings were omitted in subsequent searches. Works that only mention eSports and gender but do not examine them as their research objectives were also excluded. Studies focusing on competitive video gaming and more casual games that are not considered eSports, and those that did not specify the type of games or game titles examined were similarly excluded. The citations of the remaining studies were used to extend the search (). As presented in , the final sample comprised 21 relevant papers.

Table 1. Final sample of reviewed studies.

Analysis

This study utilised a thematic analysis to identify common themes within the reviewed literature (Ryan & Bernard, Citation2003). Three primary themes were identified: masculinities in eSports, online harassment, and negotiating gendered expectations. The identified papers were categorised according to their major focus, which was identified by analysing their titles, abstracts, and keywords. Theoretical analyses of the concepts, characteristics, or consequences of masculinities in eSports environments, including the various types of masculinities and femininities in the competitive gaming environment, were categorised under ‘masculinities in eSports.’ Articles focusing on negative experiences related to gender stereotyping and gender-based harassment within competitive gaming spaces were categorised under ‘online harassment.’ Finally, papers concentrating on the complex and diverse range of gendered expectations, identities, performances, and variations in eSports were categorised under negotiating gendered expectations. The final distribution of the selected papers is presented in .

Results

The literature review comprised 21 peer-reviewed studies published in English. The following sections identify the main findings of the reviewed papers according to the three thematic categories extracted from the studies: masculinities in eSports, online harassment, and negotiating gendered expectations.

Masculinities in eSports

To understand gender in professional gaming, it is essential to understand how masculinity is constructed in this sporting space (Taylor, Citation2012). As noted, masculinities reflect cultural values, dominant ideologies, and embodied practices (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005). However, the reviewed literature indicates that the construction of masculinity within game culture is difficult to determine. Indeed, while some gaming communities are overtly misogynistic and homophobic, others are formed by women, queerness, and the playful reappropriation of conventional gender identities (Taylor, Citation2012). eSports communities also differ based on the game title, platform, competition format, player requirements, and culture.

Among the reviewed studies, Taylor (Citation2012) suggests that masculinity in professional gaming environments is influenced by two concepts: ‘geek masculinity’ and ‘athletic masculinity.’ According to Taylor (Citation2012), geek masculinity is a specific alternate identity created in technology and computer gaming. Contrary to the dominant hegemonic masculinity in sports, geek masculinity has traditionally reflected a marginalised form of masculinity (Connell, Citation1995). For many gamers, retaining a ‘geek’ identity is crucial for maintaining their sense of seriousness, focus, and intensity. These players are also less invested in reifying hegemonic masculinity. For others, the quest to valorise eSports links it to athletics. Taylor (Citation2012) argues that the status of masculinity in eSports is woven into a battle to normalise a new twist on hegemonic masculinity, that is, to demonstrate that "real men" can play computer games.

A review of the literature reveals that there is no single type of masculinity or femininity within eSports. Gender identities change as a wider audience participates in competitive computer gaming (Taylor et al., Citation2009; Witkowski, Citation2013; Voorhees, Citation2015). This development can be seen in the chronological progress of the research, with early research focusing on the scarce participation of women in gaming (Bryce & Rutter, Citation2002) as well as the limited kinds of positionalities made available for those participating, with mothers present describing themselves as "cheerleaders," women players at risk of being labelled as "halo hoes," and promotional models being known as "booth babes" (Taylor et al., Citation2009). Although the marginalisation of women still persists, more recent research has focused on a broader and more nuanced range of gendered identities and practices performed by both men and women players (see the section on negotiating gendered expectations). In this respect, players align with different forms of gendered identities. According to Witkowski (Citation2013), the idealised performance of masculinity within eSports is tied to the high-performing male player:

He is tough and competitive; he is heterosexual (and typically white); he is lean, he performs with bravado and shows zero tolerance for flaws. He is the image of the North American digital sporting hero marketed to young male gamers engaging with electronic sports. (p. 217)

However, as Witkowski (Citation2013) noted, not all players and eSports stages match such a perfect gender-manufacturing model, nor do they all involve themselves in this model. The nuanced performances of the players observed by Witkowski (Citation2013) and their retexturing of masculinities offer an alternate practice of high-performance competition that includes finesse alongside mastery, geekdom enhanced by competitive ‘good games’ and ‘co-ed’ game space, and little ‘trash-talking’ on the sidelines.

Meanwhile, Voorhees (Citation2015) argued against the description of masculinity in eSports as a site of struggle with conflicting efforts to align eSports with hegemonic and geek masculinity. According to Voorhees (Citation2015), the performance of sportive gameplay is not a clash of rival masculinities but a hybridisation representing the combination of skills and abilities needed to succeed in eSports. Voorhees (Citation2015) contended that the sportification of digital games and the professionalisation of gaming contribute to the production of a form of subjectivity characterised by technological mastery, economic rationality, and the celebration of violence, which he terms ‘neoliberal masculinity.’ Neoliberal masculinity is characterised by subjects who embrace whichever traits a cost-benefit analysis determines will best allow them to sell their labour (Voorhees, Citation2015).

Several of the selected studies argued that the construction of masculinity in eSports has real and powerful consequences for women’s access to professional and leisure gaming spaces (Taylor, Citation2012; Vermeulen et al., Citation2014; Jenson & de Castell, Citation2018; Xue et al., Citation2019). The collision of ideologies surrounding gender, technology, and sports places women gamers in an incredibly precarious position (Taylor, Citation2012; Zolides, Citation2015; Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018), particularly insofar as they need to manage and cope with both the practical problems of simply being a player and the added obstacles that women experience in eSports contexts. Indeed, players known to be women can find themselves mediating expectations of otherness or ‘female masculinity’ (Halberstam, Citation1998). Corrective cues meant to bolster feminine expressions of gender, such as images and avatars meant to indicate sexual prowess or mentions of interests, hobbies, and practices reflecting more traditional feminine values are not unusual (Witkowski, Citation2018). This does not mean that women on the eSports scene are presenting intentional or inauthentic self-representations . Indeed, traditional signs of femininity may overlap with woman gaming and geekdom (Taylor, Citation2012). It is also used deliberately as a strategy to deal with the chauvinism and prejudices undermining women gamers (Kennedy, Citation2006).

The number of women in eSports has increased in recent years, with women proving themselves to be highly capable competitors (Jenson & de Castell, Citation2018; Cullen, Citation2018). However, many underlying gender disparity issues are maintained or exacerbated because of spectatorship rivalry overtaking conventional gaming incentives (Jenson & de Castell, Citation2018). Jenson and de Castell (Citation2018) suggested that it is not enough to reduce the gender gap in eSports. Even as women are becoming increasingly visible participants in eSports, critical reviews of the relative cost and benefits of players’ involvement is necessary to gain a deeper understanding of how the dominance of masculinity is resurging.

Women are often marginalised in terms of their access to communities through which they might develop their skills (Taylor, Citation2008). In every sport, being able to compete with people slightly above your skill level is essential to improvement. If women players cannot access meaningful challenges that allow them to develop their skills, they will not be able to compete at the same level as male competitors who can develop their professional skills as a result of their access to more robust networks and the easier occupation of gamer identity (Taylor, Citation2012). The objectification of women and use of sexist language, including sexually harassing trash talk, have become part of masculinity that simultaneously inhabits traditional forms of male privilege while shedding the outsider status and marginalisation to which geek identity has long been subjected (Taylor, Citation2012). As many of the competitive settings for eSports players are based on online environments shielded by anonymity, gender-based discrimination and hostility are likely to ensue (Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018).

Online harassment

Several of the selected studies revealed that women gamers face different expectations, receptions, and feedback from competitors compared with male gamers (Kuznekoff & Rose, Citation2013; Ratan et al., Citation2015; Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). Women are generally considered a minority in eSports; research indicates that they frequently encountered general and sexual harassment from other players (Kuznekoff & Rose, Citation2013; Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). Previous studies indicate that the combination of anonymity, lack of direct repercussions, high frequency of banter, and a competitive gaming culture in which players’ thoughts and feelings are expressed loudly often causes players to become more hostile and violent (Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). For example, Ruvalcaba et al. (Citation2018) found that while women players were 1.82 times more likely to receive sexual remarks, women streamers were 10.55 times more likely to receive sexual remarks. Examining reactions to men’s and women’s voices in eSports, Kuznekoff and Rose (Citation2013) found that women’s voices received three times more negative comments than a male voice or no voice.

Stereotype threat research demonstrated that, like traditional sport, cuing derogatory perceptions around women and gaming impacted women’s achievements in online gaming (Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). One possible consequence of a social climate hostile towards women was that women players will had less confidence in their abilities compared with male players (Ratan et al., Citation2015; Arneberg & Hegna, Citation2018). Factors, such as online abuse and harassment may prevent women players from developing their self-confidence, resulting in their becoming trapped in a destructive cycle wherein they perceive themselves as outsiders to gaming culture and are discouraged from competitive play, consequently reinforcing these stereotypes (Ratan et al., Citation2015).

Women players have utilised various strategies in response to the hostile environment of competitive gaming. A common strategy was hiding their gender from other players, including choosing gender-neutral gamertags and not using microphone features or a voice changer for conversation (Taylor, Citation2012; Arneberg & Hegna, Citation2018). However, revealing one’s gender is unavoidable at a professional level. Some women players took a more aggressive approach via acculturation, adopting powerful usernames, participating in banter and ‘trash talk,’ and adopting more in-your-face behaviour and misogynistic taunting (Taylor, Citation2012). According to Kennedy (Citation2006), women who preferred this approach were not simply ‘aping masculinity’ but partaking in something more comparable to the mythical ‘monstrous feminine,’ an opposing feminine identification within the gaming community. Consequently, these women players conceived themselves as opposing hegemonic depictions of femininity and the patriarchal portrayal of the gaming community and players in general (Kennedy, Citation2006).

Negotiating gendered expectations

Despite the continued harassment of women players in online spaces, diverse and socially shaped gendered identities have emerged across eSports (Witkowski, Citation2018). Minorities, including women players, are forced to find ways to navigate and perform across the male and masculine dominated spaces and practices of eSports. Several of the selected studies explore the nuanced spectrum of gendered identities in eSports.

With the growing commercialisation of eSports, participants in competitions are becoming more professional and celebritised (Zolides, Citation2015). However, participating in competitions and tournaments is only a small part of a professional eSports player’s income, which rests on building their brand. The commodification of professional gamers involves a complicated system of sponsorship deals, team memberships, and online reputation management (Zolides, Citation2015). The most popular gaming competitions are primarily aimed at a male audience, particularly as competitive gaming culture is closely related to the overall masculinisation of video gaming (Zolides, Citation2015). Therefore, gender is a key element in the identity formation of professional gamers, with women facing additional barriers and challenges in developing and maintaining their brand and influence (Zolides, Citation2015). Many women gamers felt a need to maintain their womanhood while preserving their position as legitimate opponents for a predominantly male audience. This performativity in a largely male-dominated culture placed women in a difficult situation in terms of making a steady income and creating their identity as women players (Zolides, Citation2015).

To make a living as successful gamers both during and after their active careers, players need to develop a specific professional identity in the eSports industry. In professional gaming, creating a commodified self involves advanced interaction between the individual and institution, personal identity and platform, and reputation and community (Zolides, Citation2015). This can be achieved in several ways. For instance, women players can emit what Taylor (Citation2012) calls ‘compensatory signals’ – various signs and cues intended to reiterate the player’s gender in this heavily male-dominated environment. Such signals might involve mentioning hobbies or interests reflecting conformity with more traditional femininity or, conversely, a more aggressive and traditional masculine stance confirming their belonging. Some women enacted both ends of the spectrum, adopting both hyper-feminine and masculine traits (Taylor, Citation2012).

Recent studies have focused on how eSports players behave in relation to gender norms. For instance, Cullen (Citation2018) demonstrated how the South Korean player Kim ‘Geguri’ Se-yeon – the first woman to compete in the highest tier of the popular game, Overwatch – actively distanced herself from femininity after being hailed a feminist gaming icon following her success in Overwatch. Cullen (Citation2018) suggested that ‘Geguri’ expressed a post-feminist sensitivity that focuses on individual freedom and inspires women players to pay less attention to systemic inequality – a sensitivity well-aligned with the meritocracy of eSports. Many of the women adhering to post-feminism have experienced a need to refuse feminism to be successful in competitive gaming environments (Cullen, Citation2018).

Scholars have also examined how male players perform gender in the eSports scene. While Voorhees and Orlando (Citation2018) found signs of technological superiority overlapping with a sportive, militaristic masculinity in a professional all-male CS: GO team, they also observed how team members took the role of an ‘outsider, everyman, team mother, boyish joker, and dandy’ (p. 211). Although masculinity configurations serve to reinforce the toxic, hegemonic model of masculinity commonly found in gaming culture, they also present opportunities to reject more pathological constructions of masculinity.

This line of research is beginning to provide insights into how eSports is influenced by cross-gender competition as players negotiate gendered expectations. This heavily stereotypical male environment and its promotion of heteronormative conduct also constrained the self-presentation of male players (Zolides, Citation2015), with several studies demonstrating how male players negotiated gendered expectations in the eSports scene (e.g. Voorhees & Orlando, Citation2018; Zhu, Citation2018). Nonetheless, male players experienced greater parallels between their gendered and gamer identities, promoting social identification and self-stereotyping among male players (Taylor, Citation2012; Zolides, Citation2015). This was unlikely for women players (Taylor, Citation2012); as their gendered identity contrasted with their gamer identity, women were less likely to associate themselves with the image of the stereotypical gamer. Women players also tended to take gender as an indication of gaming skill (Vermeulen et al., Citation2014). According to stereotype threat theory, this tendency results from the threat of affirming an unfavourable stereotype as self-characterisation (Steele & Aronson, Citation1995) and may prevent women players from identifying with the field of play (Steele, Citation1997).

Discussion: a meta-analysis of gendered power inequalities in eSports

The world of sports provides a fertile arena for addressing questions of hegemony in the form of male dominance and power and the maintenance of that power over women (Grindstaff & West, Citation2011). Like the sports industry, the eSports industry has largely been organised by and for men, resulting in a highly masculine institution (Witkowski, Citation2013; Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). The development and categories of eSports games also tend to align with what are traditionally considered masculine activities, such as first-person shooters and sport simulation games (Paaßen et al., Citation2017). The limited number of women players on the eSports scene has resulted in assumptions that women do not play as often, are less skilled, prefer less competitive formats and features, and ultimately cannot compete at the same level as male players due to inherent gender disparities (Shen et al., Citation2016). However, this perception has proven to be false (Taylor, Citation2012; Shen et al., Citation2016). Rather, the differences between men and women eSports players are caused by other aspects – experiences, cultural assumptions, and other conditions that discourage or prevent women’s involvement (Shen et al., Citation2016).

Taylor (Citation2012) argued that discussions of gender must not be conflated with discussions of women. While the construction of masculinity is central to understanding gender and professional computer gaming, the status of masculinity in eSports is complex and difficult to pigeonhole, with research findings somewhat conflicting. According to Taylor (Citation2012), the status of masculinity in professional gaming is a struggle between geek masculinity and hegemonic masculinity. Connell (Citation1995) linked sports to the reinforcement of hegemonic masculinity and a form of gender identity typically accompanied by separate and unequal spheres between men and women. In this respect, except for the emphasis on physical abilities, eSports players reflect the values of masculinity in other sports. However, some players embrace forms of geek masculinity while rejecting forms of hegemonic masculinity (Taylor, Citation2012). Meanwhile, rather than relying on essentialist notions of gender, Connell and Messerschmidt (Citation2005) suggested that "masculinities are configurations of practice that are accomplished in social action and, therefore, can differ according to the gender relations in a particular social setting" (p. 836).

Researchers have explored how eSports players are involved in, orientate themselves towards, and question the idea of hegemonic masculinity in competitive environments. The circumstances in which players are more responsive or reproductive in their role in constructing hegemonic masculinity can be explored by analysing the structures and experiences of eSports (Dworkin & Messner, Citation2002). It is also important to consider the experiences of players who find themselves ‘on the margins’ of what is considered hegemonic masculinity. In her study of negotiations of hegemonic sporting masculinities in local area network (LAN) gaming tournaments, Witkowski (Citation2013) followed Halberstam’s (Citation1998) suggestion to look beyond white middle-class men in creating an intelligible interpretation of masculinity focusing on players outside the frame of hegemonic masculinity. According to Witkowski (Citation2013), ‘players on the margins’ are directly connected to how dominant masculinities are perceived, created, and maintained in a situation through the way they conform to or rebel against these forms.

Despite not engaging in the hyper-masculine sports scene, male players are prone to having their personalities ‘measured against’ the masculinities represented by such a game or sport (Pringle & Hickey, Citation2010). Consequently, complicity with the evolving masculinity in eSports settings through socially recognisable signs of acceptable masculine display may serve to shield those who are less like the ideal image of male players in these environments. This versatility was established by Connell and Messerschmidt (Citation2005), who argue that men can adopt hegemonic masculinity when it is desirable but strategically distance themselves from hegemonic masculinity when necessary. Consequently, ‘“masculinity” represents not a certain type of man but, rather, a way that men position themselves through discursive practices’ (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005, p. 841). This makes it particularly difficult to map out players’ complicity in hegemonic sporting masculinity, as gender performances are calculated against both local and broader understandings and ‘expectations’ of heterosexuality, ‘manliness,’ and forms of geek and athlete identities.

Occurring alongside creations of hegemonic sporting masculinity, the diverse expressions of women participating in eSports are locally prominent, connected with conventional sports, and compatible with the dominance of male physical abilities, fierce competition, and heterosexual vigour (Witkowski, Citation2018; Taylor, Citation2012; Messner, Citation2007). Connell and Messerschmidt (Citation2005) framed gender as ‘always relational … [where] patterns of masculinity are socially defined in contradistinction from some model (whether real or imaginary) of femininity’ (p. 848). Based on this framing of gender, we can only begin to comprehend the transformative efforts of women engaged in competitive gaming as they do the real work of dismantling the long-established gender relational structures of these environments (Witkowski, Citation2018).

The anonymous nature of online spaces combined with a low level of gender diversity in eSports tends to generate hostile environments for those who do not fit the stereotype of a traditional eSports gamer (Darvin et al., Citation2020). This review demonstrates the considerable variations in how men and women players describe their experiences in eSports concerning discrimination and the experience or creation of hostility (e.g. Darvin et al., Citation2020; Kuznekoff & Rose, 2013; Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). This is particularly evident in online communication between players in games and on social media (Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). That many women feel the need to mask or mute their voices to avoid harassment and access ‘normal’ gameplay is connected to how gaming – in terms of capability and recognition – is ‘provided’ as an activity for men (Witkowski, Citation2018). Moreover, the causes of sexual harassment in competitive gaming spaces remain uncertain and might be a form of gatekeeping by men guarding their masculine domain. According to Maass et al. (Citation2003), male players who experience their gendered personality as vulnerable are more liable to harass women sexually. Thus, engaging in sexual harassment to strengthen a manly self-image can be understood as reinforcing the premise of hegemonic masculinity in competitive gaming environments.

Connell’s (Citation1995) model of masculinity, in which gender is understood as a dynamic process under constant revision, clarifies the double-sided nature of masculinity within game culture (Taylor, Citation2012). This model links to the work of feminist scholars who have proposed a more nuanced model of situated gender creation and performance (e.g. Butler, Citation1990; Citation1993). Researchers are beginning to elucidate this dynamic process of gender in eSports by examining the various ways in which players carefully negotiate gendered expectations in eSports (Zolides, Citation2015; Cullen, Citation2018; Voorhees & Orlando, Citation2018; Witkowski, Citation2018). Players’ understanding and performance of gender are modified according to new social situations and artefacts, relationships, institutions, and cultural practices (Taylor, Citation2012). Simultaneously, the culture surrounding the participants modifies its formulations of gender categories, with hegemonic masculinity continuing to support patriarchy (Taylor, Citation2012).

Brownmiller (Citation1984) described femininity as a ‘tradition of imposed limitations’ (p.14). However, feminine norms are noticeable and almost inevitable in eSports settings (Witkowski, Citation2018; Taylor, Citation2012; Ruvalcaba et al., Citation2018). While access discrimination is typically examined within traditional sports participation, the findings suggest that treatment discrimination is also a problem in eSports environments. Women players face limited access to communities through which they can develop themselves as players. Sometimes they simply lack networks of friends to play with; at the more extreme end, male players refuse to play against women because ‘boys don't like losing to girls’ (Taylor, Citation2012, p. 125). As such, eSports rests on the myth of meritocracy, which imagines eSports as a fundamentally individualistic and meritocratic venture. In reality, men and women players generally play on different teams and in separate tournaments because of the manner in which eSports expertise is built up and access to teams is structured (Taylor, Citation2012). The myth of meritocracy overlooks the way in which structures shape access and opportunity.

Sociological and structural limitations are likely to discourage many women from progressing as players, for example, how prior encounters with negative stereotyping result in people connected with that stereotype accommodating unfavourable assumptions (Steele & Aronson, Citation1995). Women players may assume that they are only capable of competing in women-only competitions or incapable of competing at all, and thus refrain from participating in open competitions (Ratan et al., Citation2015). This serves to perpetuate stereotypes that women cannot compete against men or that they do not belong in such competitions. The direct consequences of sexist feedback, hostility, and discrimination remain underexplored. eSports appear to possess a hyper-masculine culture like traditional sports, including the objectification and exclusion of women. Traditional sports research indicates the significant effects of this culture on women athletes – mental anguish, psychological health deterioration, and a reduction in wellness (Marks et al., Citation2012) – inferring the potential for similar outcomes in eSports environments. Even as women players become more visible participants in eSports spaces, future studies should continue examining the relative advantages and disadvantages of engagement to develop our understanding of how masculinity maintains a considerable position of power (Jenson & de Castell, Citation2018).

Conclusion

This article reviewed the current literature on gender and eSports, demonstrating how masculinity in eSports environments is complex and difficult to categorise. Despite clear differences between traditional sports and eSports, the reviewed literature suggests that many eSports environments are shaped by the hegemonic masculinity dominating other sporting contexts. Some studies reviewed in this article argued that this is because the eSports industry is organised by and for men, resulting in a highly masculine environment. The alleged physiological superiority of men over women upon which male domination and privilege are based is not as central to the virtual nature of eSports as it is in other sports. However, skills that are only "masculine" because they are virtual – that is, grounded in long-established traditions of male dominance over video game culture – have taken root in the eSports environment. Traditional sports and eSports thus discursively link masculinity, athleticism, and competition together in very similar ways. Both areas provide justifications for a profoundly imbalanced ‘playing field’ (Wachs, Citation2002), wherein assumptions of areas in which women fall short – skill, ambition, desire, and capability – are presented as physical or mental discrepancies between genders and reinforced by discursive, material, and behavioural validations of inferior and secondary roles for women.

Research findings and gender theory have systematically undermined such innate sex-based imbalances, proving them entirely misleading and often completely fabricated ‘phantasms’ (Butler, Citation1993) of an oppressive social hierarchy focused on limiting the role of women. However, such conclusions have yet to influence the current circumstances for women engaging in eSports. Moreover, unlike traditional athletes who have institutionalised paths to professionalisation, eSports players typically build their careers independently, negotiating tricky domestic circumstances and forming professional identities via player communities. For women, the way to the top is fraught with additional hurdles. According to Taylor (Citation2012), this ongoing struggle is linked to a larger conversation regarding the nature of both ‘gamers’ and ‘athletes’ within eSports. If the eSports scene is aligned with the damaging outcomes of hegemonic masculinity, the industry will benefit from analyses of how eSports affects participants to become more inclusive.

Disclosure statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Abbiss, J. (2008). Rethinking the ‘problem’of gender and IT schooling: Discourses in literature. Gender and Education, 20(2), 153–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701805839

- Arneberg, E. J., & Hegna, K. (2018). Virtuelle grenseutfordringer (Virtual boundary challenges). Norsk Sosiologisk Tidsskrift, 2(03), 259–274. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2535-2512-2018-03-05

- Beavis, C., & Charles, C. (2007). Would the ‘real’ girl gamer please stand up? Gender, LAN cafés, and the reformulation of the ‘girl’ gamer. Gender and Education, 19(6), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701650615

- Behm-Morawitz, E. (2014). Examining the intersection of race and gender in video game advertising. Journal of Marketing Communications, 23(3), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2014.914562

- Brownmiller, S. (1984). Femininity. Linden Press.

- Bryce, J., & Rutter, J. (2002). Killing like a girl: Gendered gaming and girl gamers’ visibility. In F. Mäyrä (Ed.), Proceedings of computer games and digital cultures conference. Tampere University Press. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/05164.00312.pdf

- Bryson, L. (1987). Sport and the maintenance of masculine hegemony. Women’s Studies International Forum, 10(4), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-5395(87)90052-5

- Budgeon, S. (2014). The dynamics of gender hegemony: Femininities, masculinities and social change. Sociology, 48(2), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038513490358

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble, feminist theory, and psychoanalytic discourse. In L. Nicholson (Ed.), Feminism/postmodernism (pp. 324–340). Routledge.

- Butler, J. (1993). Bodies that matter: On the discursive limits of ‘sex. Routledge.

- Cockburn, C. (1992). The circuit of technology: Gender, identity and power. In R. Silverstone & E. Hirsch (Eds.), Consuming technologies: Media and information in domestic spaces (pp. 33–42). Routledge.

- Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person, and sexual politics. Stanford University Press.

- Connell, R. W. (1995). Masculinities. University of California Press.

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

- Cullen, A. L. (2018). “I play to win!”: Geguri as a (post) feminist icon in esports. Feminist Media Studies, 18(5), 948–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1498112

- Darvin, L., Vooris, R., & Mahoney, T. (2020). The playing experiences of esports participants: An analysis of treatment discrimination and hostility in esports environments. Journal of Athlete Development and Experience, 2(1), 36–50. https://doi.org/10.25035/jade.02.01.03

- Dworkin, S. L., Messner, M. A. (2002). Just do… what? Sport, bodies, gender. In S. Scraton, & A. Flintoff (Eds.), Gender and sport: A reader (pp. 17–29). Routledge.

- Entertainment Software Association (ESA) (2018). 2018 essential facts about the computer and video game industry. https://www.theesa.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/ESA_EssentialFacts_2018.pdf

- Grindstaff, L., & West, E. (2011). Hegemonic masculinity on the sidelines of sport. Sociology Compass, 5(10), 859–881. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2011.00409.x

- Halberstam, J. (1998). Female masculinity. Duke University Press.

- Hemphill, D. A. (1995). Revisioning sport spectatorism. Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, 22(1), 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00948705.1995.9714515

- Hilbert, J. (2019, 9 April). Gaming & gender: how inclusive are eSports? The Sports Integrity Initiative. https://www.sportsintegrityinitiative.com/gaming-gender-how-inclusive-are-esports/

- Interpret. (2019, 2 March). Female esports watchers gain 6% in gender viewership share in last two years. https://interpret.la/female-esports-watchers-gain-6-in-gender-viewership-share-in-last-two-years/

- Ivory, J. D. (2009). Still a man’s game: Gender representation in online reviews of video games. Mass Communication and Society, 9(1), 103–114. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327825mcs0901_6

- Jenson, J., & de Castell, S. (2011). Girls@Play: An ethnographic study of gender and digital gameplay. Feminist Media Studies, 11(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2010.521625

- Jenson, J., & de Castell, S. (2013). Tipping points: Marginality, misogyny, and videogames. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 29(2), 72–85. http://journal.jctonline.org/index.jhp/jcp/article/view/474

- Jenson, J., & de Castell, S. (2015). Online games, gender, and feminism. In R. Mansell, & Ang, P. H. (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of digital communication and society (pp. 1–5). John Wiley & Sons.

- Jenson, J., & de Castell, S. (2018). “The entrepreneurial gamer”: Regendering the order of play. Games and Culture, 13(7), 728–746. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412018755913

- Kennedy, H. W. (2006). Illegitimate, monstrous, and out there: female ‘Quake’ players and inappropriate pleasures. In J. Hollows, & R. Pearson (Eds.), Feminism in Popular Culture (pp. 183–201). Berg.

- Kuznekoff, J. H., & Rose, L. M. (2013). Communication in multiplayer gaming: Examining player responses to gender cues. New Media & Society, 15(4), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812458271

- Lynch, T., Tompkins, J. E., Van Driel, I. I., & Fritz, N. (2016). Sexy, strong, and secondary: A content analysis of female characters in video games across 31 years. Journal of Communication, 66(4), 564–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12237

- Maass, A., Cadinu, M., Guarnieri, G., & Grasselli, A. (2003). Sexual harassment under social identity threat: The computer harassment paradigm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(5), 853–870. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.853

- Marks, S., Mountjoy, M., & Marcus, M. (2012). Sexual harassment and abuse in sport: The role of the team doctor. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 46(13), 905–908. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090345

- Massanari, A. (2017). Gamergate and the Fappening: How Reddit’s algorithm, governance, and culture support toxic technocultures. New Media & Society, 19(3), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815608807

- McRobbie, A. (2009). The aftermath of feminism: Gender, culture and social change. Sage.

- Messerschmidt, J. W. (2019). The salience of “hegemonic masculinity”. Men and Masculinities, 22(1), 85–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X18805555

- Messerschmidt, J. W. (2020). And now, the rest of the story…: A critical reflection on Paechter (2018) and Hamilton et al. (2019). Women’s Studies International Forum, 82, 102401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102401

- Messner, M. (2007). Out of play: Critical essays on gender and sport. State University of New York.

- Paaßen, B., Morgenroth, T., & Stratemeyer, M. (2017). What is a true gamer? The male gamer stereotype and the marginalization of women in video game culture. Sex Roles, 76(7–8), 421–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0678-y

- Paechter, C. (2018). Rethinking the possibilities for hegemonic femininity: Exploring a Gramscian framework. Women's Studies International Forum, 68, 121–128. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2018.03.005

- Pringle, R. G., & Hickey, C. (2010). Negotiating masculinities via the moral problematization of sport. Sociology of Sport Journal, 27(2), 115–138. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.27.2.115

- Ratan, R. A., Taylor, N., Hogan, J., Kennedy, T., & Williams, D. (2015). Stand by your man: An examination of gender disparity in League of Legends. Games and Culture, 10(5), 438–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412014567228

- Rietkerk, R. (2020, February 25). Newzoo: The global esports audience will be just shy of 500 million this year. https://newzoo.com/insights/articles/newzoo-esports-sponsorship-alone-will-generate-revenues-of-more-than-600-million-this-year/

- Ruvalcaba, O., Shulze, J., Kim, A., Berzenski, S. R., & Otten, M. P. (2018). Women’s experiences in eSports: Gendered differences in peer and spectator feedback during competitive video gameplay. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 42(4), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723518773287

- Ryan, G. W., & Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X02239569

- Schelfhout, S., Bowers, M. T., & Hao, Y. A. (2021). Balancing Gender Identity and Gamer Identity: Gender Issues Faced by Wang ‘BaiZe’ Xinyu at the 2017 Hearthstone Summer Championship. Games and Culture, 16(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019866348

- Schippers, M. (2007). Recovering the feminine other: Masculinity, femininity, and gender hegemony. Theory and Society, 36(1), 85–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-007-9022-4

- Schofield, J. W. (1995). Computers and classroom culture (pp. XII, 271). Cambridge University Press.

- Shen, C., Ratan, R., Cai, Y. D., & Leavitt, A. (2016). Do men advance faster than women? Debunking the gender performance gap in two massively multiplayer online games. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 21(4), 312–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12159

- Siutila, M., & Havaste, E. (2019). A pure meritocracy blind to identity: Exploring the online responses to all-female esports teams in Reddit. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 4(3), 43–74. https://doi.org/10.26503/todigra.v4i3.97

- Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.6.613

- Steele, C. M., & Aronson, J. (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 797–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797

- Taylor, N., Jenson, J., & De Castell, S. (2009). Cheerleaders/booth babes/Halo hoes: Pro-gaming, gender, and jobs for the boys. Digital Creativity, 20(4), 239–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/14626260903290323

- Taylor, T. L. (2008). Becoming a player: Networks, structures, and imagined futures. In Y. B. Kafai (Ed.), Beyond Barbie and Mortal Kombat: New perspectives on gender and gaming (pp. 51–66). MIT Press.

- Taylor, T. L. (2012). Raising the stakes: E-sports and the professionalization of computer gaming. The MIT Press.

- Vermeulen, L., Núñez Castellar, E., & Van Looy, J. (2014). Challenging the other: Exploring the role of opponent gender in digital game competition for female players. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 17(5), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2013.0331

- Voorhees, G. (2015). Neoliberal masculinity: The government of play and masculinity in e-sports. In R. A. Brookey, & T. P. Oates (Eds.), Playing to win: Sports, video games, and the culture of play (pp. 63–91). Indiana University Press.

- Voorhees, G., & Orlando, A. (2018). Performing neoliberal masculinity: Reconfiguring hegemonic masculinity in professional gaming. In N. Taylor, & G. Voorhees (Eds.), Masculinities in play (pp. 211–227). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wachs, F. L. (2002). Leveling the playing field: Negotiating gendered rules in co-ed softball. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 26(3), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723502263006

- Wajcman, J. (1991). Feminism confronts technology. Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Walker, N. A., & Sartore-Baldwin, M. L. (2013). Hegemonic masculinity and the institutionalized bias toward women in men’s collegiate basketball: What do men think? Journal of Sport Management, 27(4), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.4.303

- Witkowski, E. (2013). Eventful masculinities: Negotiations of hegemonic sporting masculinities at LANs. In M. Consalvo, J. Mitgutsch, & A. Stein (Eds.), Sports videogames (pp. 225–243). Routledge.

- Witkowski, E. (2018). Doing/undoing gender with the girl gamer in high-performance play. In K. L. Gray & G. Voorhees (Eds.), Feminism in play (pp. 185–203). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Xue, H., Newman, J. I., & Du, J. (2019). Narratives, identity, and community in esports. Leisure Studies, 38(6), 845–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1640778

- Zhu, L. (2018). Masculinity’s new battle arena in international e-sports: The games begin. In N. Taylor, & G. Voorhees (Eds.), Masculinities in play (pp. 229–247). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zolides, A. (2015). Lipstick bullets: Labour and gender in professional gamer self- branding. Persona Studies, 1(2), 42–53. https://doi.org/10.21153/ps2015vol1no2art467