Abstract

While sport has traditionally been seen, and represented, as a male domain, some sports, such as rugby, have been particularly ‘gender-typed’ as masculine. However, in recent years, this narrative has been challenged by the rising profile, and popularity, of women’s rugby. In response to these shifts, this paper uses a survey to explore rugby fans’ attitudes towards women’s rugby and employs a framework adapted from the study of football to make sense of the data. The findings suggest that although some rugby fans’ attitudes align with the earlier football model, covert misogyny is a less salient category. Furthermore, female fans of rugby are as likely to hold overtly misogynistic and sexist attitudes towards the women’s game as male fans. Finally, it suggests that the middle-class culture of the sport is more likely to lead to careful impression management when discussing women’s rugby, which is reflected in our use of the category of ‘gender-bland’.

Introduction

While sport has traditionally been seen, and represented, as a domain dominated by men, some sports have been particularly ‘gender-typed’ as masculine (Allison, Citation2018; Pfister et al., Citation2013; Pope et al., Citation2022). This is especially true of rugby union, where an established body of research has demonstrated that the sport is associated with hypermasculine values (Chandler & Nauright, Citation1996; Dunning, Citation1994; Ezzell, Citation2009; Hardy, Citation2015), that are used to marginalise women through negative stereotyping, misogyny and structural inequalities (Joncheray & Tlili, Citation2013; Kanemasu, Citation2022; Nauright & Carle, Citation1999).

However, in recent years, this narrative has been challenged in a number of ways (Kitson, Citation2023). For instance, in England, the number of adult women playing rugby has grown from 25,000 to 40,000 since 2017 (Donnelly, Citation2022). Second, the game has attracted more media coverage and sponsorship, with the UK’s main public service broadcaster, the BBC, streaming one game a week in England’s top-flight domestic competition and the brewing company Guinness sponsoring the Women’s Six Nations international competition (BBC Sport, Citation2023; Mairs, Citation2023).

It is against this backdrop of the growing popularity and profile of the women’s game, that this paper explores the views of rugby union fans. Although there is an established literature on sports fandom, there is limited study of fans’ attitudes towards women in sport. A notable exception is Stacey Pope and her colleagues work (Cleland et al., Citation2020; Pope et al., Citation2022) on fan attitudes towards women’s football which offers a guiding framework for this work. As in their 2020 study we examine both male and female fans’ attitudes towards the women’s game via an online survey. However, our findings point to a number of differences between fans of the two sports. First, although rugby fans’ attitudes somewhat align with the three-part model developed by Pope et al. (Citation2022), covert misogyny is a much less salient category. Second, female fans of rugby are as likely to hold overtly misogynistic and sexist attitudes towards the women’s game as male fans. Thus, it is argued that women are complicit in the construction of gender hierarchies within the sport. Finally, it suggests that the middle-class culture of rugby is likely to lead to more careful impression management, an idea that can be usefully conceptualised in relation to Musto et al’s category of ‘gender bland’ attitudes (Musto et al., Citation2017). In the following sections, we first briefly outline the ways in which participation in, and representation of, sport, in general, has often been linked to gender hierarchies as well as the gendering of sports fandom. We then discuss the ‘traditional’ status of rugby union as a hypermasculine sport before engaging with the small body of research that has examined responses to the growing involvement of women, notably as players and fans, in the sport.

Sport as a gendered domain

Traditionally, sport has been an arena where gender hierarchies that emphasise male dominance and female subservience are performed and celebrated (Bryson, Citation1994; Creedon, Citation1994; Dunning, Citation1994). Indeed, the key concept of hegemonic masculinity (Connell, Citation1987, Citation2005), which is associated with characteristics such as authority, physical strength, and heterosexuality, has long been analysed in relation to sport. And physically demanding contact sports, such as rugby, are seen as particularly important arenas where men can ‘bolster’ their masculinity and ‘vilify and objectify’ women (Dunning, Citation1994: 170). However, the establishment and maintenance of such hierarchies may also involve women through acts of ‘emphasised femininity’, such as support for ‘traditional gendered’ dress, behaviour, language and social relations. This latter idea will be picked up in some of our subsequent discussions of female fans’ attitudes towards women’s rugby, where older women tend to be more critical of women’s rugby.

When it comes to reproducing gender hierarchies, the role of mainstream media has also been noted, both in general terms and in relation to sport (e.g. Creedon, Citation1994; Bryson, Citation1994). In the latter case, studies of the overall coverage of women’s sports have consistently shown that the vast majority of mainstream sports reporting is dedicated to the activities of men (Cooky et al., Citation2015; O’Neill & Mulready, Citation2015). Moreover, when women’s sporting activities have been covered by the media, they are often trivialised and/or sexualised. In the first place, women’s sport has often been unfavourably judged in comparisons to the activities and achievements of male athletes, rather than on its own terms (Bruce, Citation2017). The second feature of mainstream reporting of women’s sport is that it has, at times, promoted aesthetics over achievements by evaluating sportswomen as objects of sexual desire, not as competent athletes (Cooky et al., Citation2015).

However, there is growing evidence that both the quantity and quality of mainstream coverage of women’s sport has improved over the past decade, raising their profile and engaging new audiences (Petty & Pope, Citation2019). Elsewhere, other studies have shown that digital technologies have also allowed female athletes, and their advocates, to represent women’s sport in novel ways (Pocock & Skey, Citation2024). Having briefly examined the links between gender hierarchies and sport in relation to participation and representation, in the following section we turn to the issue of sports fandom, which is another area where men have tended to dominate at the expense of women.

The role of fans within sport

Women continue to be under-represented in sports fandom, with a recent study noting that twice as many men self-identified as sports fans (Dietz et al., Citation2021). As a result, female spectators of sport are often not treated seriously and, in many cases, have been subject to negative stereotyping (Hoeber & Kerwin, Citation2013). In the latter case, this would include accusations that women fake an interest in the sport just to get closer to men or are not knowledgeable, dedicated or committed enough to be defined, and accepted, as sport fans (Esmonde et al., Citation2015; Cleland et al., Citation2020).

As a result, in many sporting contexts, female fans of sport are forced to respond to openly sexist attitudes and activities. Their responses range from confronting sexist abuse directly (never easy in a hostile environment) or downplaying any sexism and arguing that it is part of the atmosphere at sporting events (Jones, Citation2008; Pope, Citation2013).

While, however, there is a growing body of literature on female sports fandom (Pope, Citation2013, Citation2015), research on fans’ perceptions of women’s sport is sparse and generally focuses onattitudes towards women’s football (Cleland et al., Citation2020; Leslie-Walker & Mulvenna, Citation2022; Williams et al., Citation2022).

And although there is evidence that increasing numbers are watching the game (YouGov, Citation2022), research continues to show that there is still deep hostility towards women’s football with some fans believing that the game lacks seriousness, physicality, competitiveness and quality (Cleland et al., Citation2020; Leslie-Walker & Mulvenna, Citation2022; Williams et al., Citation2022). In order to assess these attitudes in a more systematic way, Pope et al. (Citation2022) created a three-part theoretical model of men’s football fans performance of masculinity in relation to women’s football, identifying three categories on an overlapping continuum. They found that fans would exhibit either: 1) Progressive masculinities where more gender equitable attitudes are articulated, 2) Overtly misogynistic masculinities with more openly hostile and sexist attitudes or 3) Covertly misogynistic masculinities, in which respondents combine some support for gender equality agendas with views that classify women’s sport as inferior. Furthermore, Pope et al. (Citation2022) argue that while the number of ‘progressive’ fans seems to be growing, many fans still articulate negative attitudes towards women within football and in doing so, defend existing fan practises that serve to exclude women from the sport.

While the rise in work on attitudes towards women’s football is welcome, there still remains limited research on other women’s sport, including rugby. This is the issue we address in the following section.

Rugby: a hypermasculine (and middle-class) arena

As we noted earlier, rugby has been traditionally viewed as a sport associated with hegemonic forms of masculinity, that focus on ideas around physical power, heterosexuality and comradeship (Chandler & Nauright, Citation1996; Wright & Clarke, Citation1999). In the 19th and 20th century, this macho culture was performed both on the field and through its traditions of initiations, drinking culture and the mocking and degrading of women (Dunning, Citation1994). Therefore, women that entered this space were often viewed as ‘sporting space invaders,’ who disrupted traditional social hierarchies in the sport and, as a result, were often denigrated by men (Brown, Citation2015; Puwar, Citation2005). Indeed, women continue to face challenges in relation to the sport, whether that relates to media coverage or wider public attitudes, with only 11% of people saying they would watch a women’s game (Abraham, Citation2020) and 80% of female players facing resistance from family members about playing rugby (Joncheray & Tlili, Citation2013). Elsewhere, work examining the representation of women rugby player’s has focused on female players’ response to negative stereotypes around sexual orientation and gender ‘norms’. For example, Hardy (Citation2015) found that female rugby players rarely challenge stereotypical labels around lesbianism and (failed) masculinity in the sport, with players often accepting such negative stereotypes as normal. Elsewhere, Ezzell (Citation2009) suggests that players use defensive othering as a way to manage negative representations of women’s rugby, by deflecting the ‘butch lesbian’ stereotype onto others within the sport. However, these stereotypes have been somewhat challenged by the growing numbers of women taking up the sport For instance, from 2017-2022, the number of adult female players grew ‘from 25,000 to 40,000 in England [while] … the Rugby Football Union (RFU) has ambitious targets … to grow … [player] numbers to 100,000 by 2027’ (Donnelly, Citation2022).

This small, but growing, number of female rugby players have also made attempts to reclaim and distort (masculine) rugby traditions in other ways, such as singing rugby songs that celebrate female sexuality (Wheatley, Citation1994).

Alongside, gender hierarchies within the sport of rugby union, it should also be noted that class distinctions have played a major role in shaping who participates, both playing and spectating. Indeed, as we will see in subsequent sections, middle-class mores tend to influence how rugby fans discuss ‘their’ sport. Moreover, this is not unusual in Britain, where as Hill (Citation1996: 5-6) notes, ‘sporting preferences …. since the second half of the nineteenth century have been very clear signifiers of class position’. To this end, rugby union was developed, codified and then nurtured in public and grammar schools, which were the preserve of the English middle and upper-classes (Collins, 2009). This legacy can still be seen in the fact that even in the late-2000s, over 58% of supporters at Premiership rugby matches came from the top AB socio-economic groups (ibid: 128).

Given these contrasting trends, the growing participation of women, alongside the maintenance of established class hierarchies, this study offers a useful opportunity to assess the attitudes of both male and female fans of contemporary rugby. In the next section, we outline how the data that forms the basis for our empirical research on the topic was generated and analysed.

Data collection and analysis

The study followed recent studies of football fandom by using an online survey to to research rugby fans’ attitudes towards women’s rugby.

As the study was primarily interested in the perceptions and attitudes of fans of rugby towards the women’s game, the online survey was targeted at self-identified fans of rugby, aged 18 and above. Demographic information on gender and age was collected in order to compare responses between different social groups and participants were asked to provide the rugby club they support as a means of reducing sampling error. This was especially important as there was no control over who answered the survey (Phellas et al., Citation2012).

In terms of distribution, the questionnaire was shared to a number of online rugby fan forums on Facebook. These included a group owned by a nationally recognised rugby brand, as well as five Premiership Rugby Clubs, which have an affiliated women’s team. Respondents were also asked to share the study to their networks.

Although this combination of convenience and snowball sampling doesn’t allow us to make any claims about the representativeness of our data, the size of the sample (1381) gives us some confidence that a range of relevant views were captured by our approach. Of the total number of survey participants, 814 identified as male, 558 as female, 1 as other and 8 preferred not to say. This is interesting for a sport that is typically characterised as male dominated (Chandler & Nauright, Citation1996), as over 40% of the respondents were female. The questionnaire itself was modelled on the one Pope et al. (Citation2022) used for their study of male football fans’ attitudes towards women’s sport. This allowed us to compare our results with their earlier version and identify key differences between fans of the respective sports.

In terms of data analysis, the first stage involved identifying patterns in, and the distribution of, attitudes towards women’s rugby among the survey responses through univariate and bivariate analysis using SPSS. The analytical categories developed by Pope and her colleagues in relation to football fans (progressive, overtly misogynistic and covertly misogynistic) were then applied to the data and assessed for their relevance. In the second stage, qualitative data from the survey was thematically analysed and used to assess the main quantitative results.

Progressive attitudes

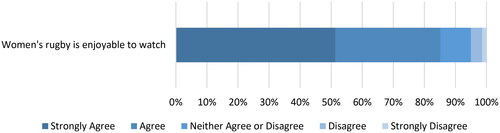

It is worth noting that the majority of those surveyed (See ) expressed progressive attitudes towards the women’s game. This compares with Pope et al. (Citation2022) study of football, which found that overt misogynistic attitudes dominated. In fact, less than 20% of the sample did not agree that women’s rugby was enjoyable to watch.

When asked about their experience of the women’s game, many participants stated that they have seen a positive change in attitudes towards women’s rugby during the past decade.

Moreover, when asked about their experience of watching the women’s game, 83% of respondents were positive. These attitudes were remarkably similar for both men and women, with figures of 84.1% and 81.4% respectively. Here, many of the respondents agreed that women’s rugby was enjoyable to watch due to ‘a different skill range within the women’s game’ (Female, 18-24) and by focusing ‘more on speed and agility, rather than the physicality that is a big part of the men’s game’ (Male, 25-44).

A small number of those with progressive attitudes said they found the women’s game ‘surprisingly good quality’ (Male, 55-64) and that they were ‘impressed with the standard’ (Male, 25-34), suggesting there are still assumptions that women’s sports are inferior to men’s (Allison, Citation2018; Bryson, Citation1994). Nonetheless, these fans’ positive enjoyment of the game highlights that these assumptions can be reversed, reflecting Pope et al’s (Citation2022) findings that male football fan’s attitudes are changeable over time, under certain conditions. This often occurs when there is greater accessibility to the game through media coverage, notably during major sporting events such as the world cup, the issue we turn to next.

The impact of the women’s rugby world cup (WRWC)

In fact, a key event when it came to changing attitudes towards women’s rugby was the WRWC, which was mentioned by 71% of respondents. This aligns with Allison and Pope’s (Citation2022) findings that sporting mega-events can generate interest in women’s sport. This event, which took place in late 2022 after being delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic, saw a record-breaking 34,235 at the final, which, at the time, was the highest attendance for a women’s game in history (World Rugby, Citation2022).

Only 10.8% of women and 12.7% of men in the sample did not engage with the WRWC at all. This is a stark change from the results of a 2020 YouGov poll of British adults, which found that 89% would not watch a women’s game (Abraham, Citation2020), thus suggesting that attitudes are more progressive now than four years ago. However, it is important to note that the present study targeted fans of rugby, who are potentially more likely to engage with the sport than the general population. In fact, the WRWC was often given as an example to positively compare women’s rugby to men’s:

I think the success and coverage of the England team in the women’s World Cup has generated interested. The players’ obvious enjoyment (particularly compared to the men) is infectious. (Female, 55-64)

Women’s world cup was excellent to watch. Good skill level, close, exciting matches. Played with a different (enjoyable) spirit to the men’s game (Male, 45-54)

The UK went crazy for the Lioness when they won the Euros earlier on in the year (and rightfully so) but why can’t we have the same effect and impact from women’s rugby. (Male, 25-34)

This reflects Pfister’s (Citation2015) idea that football is leading the way for gender equality within sport, with increased participation and careful media framing encouraging more fan engagement with the sport. Accordingly, some respondents did have hope that the Red Roses would follow in the Lionesses’ path:

I think the women’s football team had more success in changing public opinion about women in sports in general and in the future I hope the Red Roses can have the same impact on sport. (Female, 18-24)

Positive support for media coverage of women’s rugby

While some fans highlighted that the increased exposure to the women’s game on television ‘has allowed them to demonstrate level of skill and commitment they have’ (Male, 35-44), others highlighted the potential for it to ‘grow and improve’ (Male, 35-44) the game by making role models visible, encouraging grassroots participation and pushing further funding into the game:

Women’s rugby is finally being taken seriously. Television companies have realised that there is an audience for it (Female, 55-64)

Therefore, although there is increased television coverage of women’s game, with fans agreeing that women’s rugby ‘is a lot more recognised in mainstream media’ (Male, 45-54), there was an acknowledgement that ‘the media view is still strongly biased towards the men’s game’ (Male, 65+). Hence, while women’s rugby is not symbolically annihilated in the media (Allison, Citation2018; Tuchman et al., Citation1978), there is still a lack of coverage of the game (Women in Sport, Citation2018), with many fans reflecting that ‘there is more to do to raise its profile and get more coverage on TV’ (Female, 45-54).

In conclusion, then, rugby fans that have progressive attitudes towards women’s sport are more likely to favour moves towards equality between genders within rugby. Furthermore, these respondents gave evidence to suggest that attitudes are shifting over time, with key moments such as greater media exposure and mass sporting events driving this change (Pope et al., Citation2022). Nevertheless, it was highlighted that there remain inequalities within the sport, such as a lack of recognition of success and limited media coverage. Moreover, those that share progressive attitudes are more likely to agree that there is still a way to go until equality is reached.

Overtly misogynistic attitudes

Despite the dominance of progressive attitudes in the sample, it is also important to note that 4.8% of male survey respondents demonstrated overtly misogynistic attitudes towards the women’s game. Furthermore, 4% of women also expressed these attitudes. This latter statistic is perhaps surprising but also demonstrates how women can also be involved in supporting ‘traditional’ gender categories and hierarchies (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005).

Alongside fans who find it ‘difficult to watch women’s rugby having been brought up on proper rugby’ (Female, 45-54) and others that believe it is an ‘appalling spectacle’ (Female, 55-64), fans that shared overt misogynistic attitudes often directly compared the men’s and women’s game, especially in terms of quality and enjoyability, thus reinforcing ideas of hegemonic masculinity (Connell, Citation2005):

The most elite level of rugby in this country is the men’s English premiership. I like to watch the most elite levels humans can do (Male, 45-54)

I personally don’t like women’s contact sports. It’s just not for me. The physicality isn’t there (when compared to the men’s game) (Male, 45-54)

Frankly, I enjoy the physical power and characteristics of the traditional men’s game which cannot be replicated by women. (Fan, Male, 65+)

Whilst I have no interest in watching women’s football and rugby, I do watch men’s and women’s tennis and men’s and women’s athletics. But football and rugby at women’s level does not interest me. So would watch a lower-level men’s rugby game every time over a women’s game. (Male, 65+)

I don’t want to see female rugby players just like I don’t want to see male ballet dancers (Male, 55-64)

Forgive me for saying, but rugby is not a game for women. Sorry (Male, 55-64)

Beyond appeals to biological essentialism and gendered traditions, overtly misogynistic attitudes were also underpinned by concerns ‘about the standard’ (Female, 45-54) or that the games are ‘not value for money’ (Male, 18-24). These viewpoints can be summarised by the following example, which puts forward a number of stereotypes both about women and the sport in general (Allison, Citation2018; Theberge, Citation1994):

Not so interested in the women’s game - less intensity, lower skill level, not so much atmosphere (Female, 35-44)

Without atmosphere and awareness and constant training as a professional the women’s game doesn’t seem so attractive. But I am uncomfortable with this! (Male, 18-24).

Given the support and press coverage the women’s game is not delivering. England had a massive advantage and yet failed to deliver at the World cup (Male, 55-64)

Who cares? A serious question. Every example of this totalitarian attitude to level up Women’s sports that are male sports is ridiculous. Sports fans want top level sport not clown-show performative nonsense … stop telling everyone a female winning streak is the same as a men’s winning streak. It is not … the final nail at the Women’s World Cup was the media telling me a female player was better than Jonah Lomu. (Male, 55-64)

In the next section, we introduce the final category of gender-bland attitudes, which contrasts with previous research on football fandom and points to the importance of class differences between the two sports.

Gender-bland attitudes

Although the majority of misogynistic attitudes in Pope et al’s (Citation2022) study of football fans were overt, they also found that a small but significant proportion of respondents’ attitudes towards women’s football were more complicated, involving both positive and negative elements. Alternatively, many fans in this study would present a carefully managed viewpoint, that neither supported nor denigrated women’s rugby. In other words, they discussed the sport in generally positive terms, whilst also indicating that they continue to see the women’s game as inferior. We label these attitudes as gender-bland, a term previously used to describe respectful but lacklustre television coverage of women’s sport that continues to define male sport as the ‘norm’ (Musto et al., Citation2017).

Moreover, our findings show that significantly more respondents put forward gender-bland than overtly negative attitudes. This again could be explained by the middle-class nature of rugby fandom, which makes it more likely that any controversial viewpoints are tactfully communicated so as to save face and avoid potential criticism (Goffman, Citation1967). What’s more, a higher proportion of women to men aligned with this attitude, with 13.3% compared to 11.2%. This novel finding ties in with Hoeber and Kerwin (Citation2013) research on female sports fandom. In it they argue that the ambiguous status of female fans, and their struggle to be accepted, can lead to the marginalisation and stereotyping of other women. In this way, the articulation of gender-bland attitudes by female fans can be viewed as a way to cement their place within a space that is often antagonistic towards women.

Another example of these gender-bland attitudes can be seen in the way that some fans either cautiously praised the women’s game or acknowledged the continuing disadvantages that women faced in the sport

The skill level shown in the women’s game needs work. But I love the passion and heart on show. (Male, 25-34)

I agree that women’s rugby is disadvantaged and should be professionalised but that still doesn’t mean that I would necessarily choose to watch it; I do think they should have the same rights as the men though (Female, 35-44)

The first quote can be viewed as another example of infantilising women within rugby, where they are seen as enthusiastic but not as talented as men. This has been identified as a common feature in much mainstream reporting of women’s sport as well, with many studies (cf Biscomb & Griggs, Citation2013; Bruce, Citation2017) noting that the attributes and achievements of female athletes are downplayed or trivialised rather than being discussed or celebrated on their own terms.

Despite this, some fans were open to how the increased success and exposure of the women’s game has not changed their own attitudes, but recognised how it has impacted those around them:

Not personally but it has created more recognition/appreciation for the women’s game. (Male, 45-55)

A further feature linked to gender-bland attitudes concerned the lack of awareness of women’s rugby, primarily linked to the pre-eminence of the men’s game in the media. For example, one female respondent (55-64) understood that her attitudes towards the game were ‘conditioned to think that the men’s game is better because that is all we’ve known.’ Here, she drew on stereotypes around it being a physical game, and not therefore not suitable for women, drawing on established gender hierarchies whilst at the same time querying their salience (Chandler & Nauright, Citation1996).

Conclusion

This paper was designed to fill in a gap in the literature on sport, gender and communication by examining attitudes towards women’s rugby, a topic that has received little attention. To do this, we drew on Pope et al. (Citation2022) framework for studying attitudes towards women’s football. The findings demonstrate that the rugby fans had an overwhelmingly progressive view (83.6%) towards the women’s game. However, 4.4% of fans demonstrated that misogynistic views towards the game remain, with women’s rugby denigrated in relation to ideas around biological essentialism, hegemonic masculinity, and anti-feminism (Connell, Citation2005; Faludi, Citation1992; Nauright & Carle, Citation1999).

However, three important refinements were made to the model in response to our empirical data. First, although the survey results demonstrate that rugby fans align with men football fans in terms of expressing either progressive or overtly misogynistic attitudes, the third category (of covert misogynistic attitudes) put forward by Pope et al. (Citation2022) was found to be problematic when applied to rugby. Instead of displaying covertly misogynistic attitudes towards the women’s game (as in the case of football), rugby fans expressed a passivity towards the sport. This combined a more positive outlook to the game in general while continuing to position it as inferior to the male equivalent. Thus, fans that fell within this category were seen to have gender-bland attitudes, reflecting a form of sexism theorised by Musto et al. (Citation2017). These views are underpinned by language that normalises a hierarchy between men’s and women’s sport while avoiding overt sexism.

Secondly, this study included responses from female fans of rugby in the survey. Interestingly, they were as likely as male fans to demonstrate overtly misogynistic and gender-bland attitudes, thereby normalising male dominance within the sport. This echoes Messerschmitt’s (2012) argument concerning the key role that women can play in the development, and normalisation, of hegemonic masculinity. Therefore, it is argued that when researching attitudes towards women’s sport, the agency of women in sustaining gender hierarchies must also be considered.

Third, the distribution of attitudes towards women’s rugby differed to those towards women’s football, with significantly more respondents in this study aligning with progressive attitudes than any other. This directly contrasts with Pope et al’s (Citation2022) study, where overtly misogynistic attitudes dominated. Here, it is suggested that a sport’s culture can have an influence on the distribution of fans’ attitudes between the three themes. In the case of rugby, it seems likely that the sport’s middle-class fanbase (Wright & Clarke, Citation1999) will have, or at least want to be associated with, more progressive or ‘reasonable’ attitudes. This idea also points to a notable limitation of this study, which is that it did not include class as a demographic variable. Future research would be advised to explore this important issue in much more detail.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abraham, T. (2020, March 8). Seven in ten support equal coverage for women’s sport, but not at the cost of men’s coverage. YouGov. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/sport/articles-reports/2020/03/08/seven-ten-support-equal-coverage-womens-sport-not-

- Allianz Premier15. (2023). Live. Allianz Premier15s. https://www.premier15s.com/live-streams

- Allison, R. (2018). Kicking Centre: Gender and the selling of women’s professional soccer. Rutgers University Press.

- Allison, R., & Pope, S. (2022). Becoming fans: Socialization and motivations of fans of the England and U.S. Women’s National Football Teams. Sociology of Sport Journal, 39(3), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2021-0036

- Anderson, E. (2009). Inclusive masculinities: The changing nature of masculinities. Routledge.

- BBC Sport. (2022, December 9). WSL average attendances up by 200% after women’s Euro 2022 victory. BBC Sport. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/63913485

- BBC Sport. (2023, January 13). The premier 15s: BBC live fixtures. BBC Sport. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/rugby-union/63839755#:∼:text=The%20Premier%2015s%202022%2D23,up%20on%20the%20BBC%20iPlayer

- Biscomb, K., & Griggs, G. (2013). ‘A splendid effort!’Print media reporting of England’s women’s performance in the 2009 Cricket World Cup. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 48(1), 99–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690211432061

- Brown, L. E. C. (2015). Sporting space invaders: Elite bodies in track and field, a South African context. South African Review of Sociology, 46(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2014.989666

- Bruce, T. (2017). Sportswomen in the media: An analysis of international trends in Olympic and everyday coverage. Sports and Gender Studies, 15, 24–39.

- Bryson, L. (1994). Sport and the maintenance of masculine hegemony. In S. Birrell & C. L. Cole (Eds.), Women, sport and culture (pp. 47–64). Human Kinetics.

- Chandler, T. J. L., & Nauright, J. (1996). Introduction: Rugby, manhood and identity. In. J. Nauright, & T. J. L. Chandler (Eds.), Making men: Rugby and masculine identity (pp. 1–12). Frank Cass.

- Cleland, J., Pope, S., & Williams, J. (2020). “I do worry that football will become over-feminized”: Ambiguities in fan reflections on the gender order in men’s professional Football in the United Kingdom. Sociology of Sport Journal, 37(4), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2019-0060

- Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power. Polity Press.

- Connell, R. W. (2005). Masculinities (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society, 19(6), 829–859. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27640853 https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

- Cooky, C., Messner, M. A., & Musto, M. (2015). “It’s Dude Time!”: A quarter century of excluding women’s sports in televised news and highlight shows. Communication & Sport, 3(3), 261–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479515588761

- Creedon, P. J. (1994). Women, media and sport: Creating and reflecting gender values. In P. J. Creedon (Ed.), Women, media and sport: challenging gender values (pp. 3–27). Sage Publications.

- Dietz, B., Bean, J., & Omaits, M. (2021). Gender differences in sport fans: A replication and extension. Journal of Sport Behaviour, 44(2), 183–198.

- Donnelly, A. (2022, November 9). World Cup run goes hand in hand with growth of women’s game. Sport England. https://www.sportengland.org/blogs/world-cup-run-goes-hand-hand-growth-womens-game

- Dunning, E. (1994). Sport as a male preserve. In S. Birrell & C., L. Cole (Eds.), Women, sport and culture (pp. 163–179). Human Kinetics.

- Esmonde, K., Cooky, C., & Andrews, D. L. (2015). “It’s supposed to be about the love of the game, not the love of Aaron Rodgers’ eyes”: Challenging the exclusions of women’s sports fans. Sociology of Sport Journal, 32(1), 22–48. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2014-0072

- Ezzell, M. B. (2009). “Barbie Dolls” on the pitch: Identity work, defensive othering, and inequality in women’s rugby. Social Problems, 56(1), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2009.56.1.111

- Faludi, S. (1992). Backlash: The undeclared war against women. Chatto & Windus.

- Garry, T. (2022, December 26). Women’s sport is booming – And that is borne out by the statistics. The Telegraph. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/womens-sport/2022/12/26/womens-sport-booming-borne-statistics/

- Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual. Pantheon Books.

- Hardy, E. (2015). The female ‘apologetic’ behaviour within Canadian women’s rugby: athlete perceptions and media influences. Sport in Society, 18(2), 155–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.854515

- Hill, J. (1996). British sports history: A post modern future? Journal of Sport History, 23(1), 1–19.

- Hoeber, L., & Kerwin, S. (2013). Exploring the experiences of female sport fans: A collaborative self-ethnography. Sport Management Review, 16(3), 326–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.12.002

- Joncheray, H., & Tlili, H. (2013). Are there still social barriers to women’s rugby? Sport in Society, 16(6), 772–788. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2012.753528

- Jones, K. W. (2008). Female fandom: Identity, sexism and men’s professional football in England. Sociology of Sport Journal, 25(4), 516–537. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.25.4.516

- Kane, M. J., & Greendorfer, S. L. (1994). The media’s role in accommodating and resisting stereotyped images of women in sport. In P. J. Creedon (Ed.), Women, media and sport: Challenging gender values (pp. 28–44). Sage Publications.

- Kanemasu, Y. (2022). Fissures in gendered nationalism: the rise of women’s rugby in Fiji. National Identities, 25(4), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/14608944.2022.2132477

- Kitson, R. (2023, March 3). Women’s rugby revolution gathers pace but the sums don’t yet add up. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2023/mar/03/womens-rugby-revolution-gathers-pace-but-the-sums-still-dont-add-up

- Leslie-Walker, A., & Mulvenna, C. (2022). The Football Association’s Women’s Super League and female soccer fans: Fan engagement and the importance of supporter clubs. Soccer & Society, 23(3), 314–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2022.2037218

- Mairs, G. (2023). Six Nations ends TikTok sponsorship with £15m-per-year Guinness deal. Telegraph Online. Retrieved March, 2024, from https://www.telegraph.co.uk/rugby-union/2023/12/12/six-nations-ends-tiktok-sponsorship-with-15m-guinness-deal/

- Messner, M. A. (2007). Out of play: Critical essays on gender and sport. State University of New York Press.

- Musto, M., Cooky, C., & Messner, M. A. (2017). “From Fizzle to Sizzle!” Televised Sports News and the Production of Gender-Bland Sexism. Gender & Society, 31(5), 573–596. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243217726056

- Nauright, J. (1996). Sustaining masculine hegemony. In J. Nauright and T., J., L., Chandler (Eds.), Making men: Rugby and masculine identity (pp. 227–244). Frank Cass.

- Nauright, J., & Carle, A. (1999). Crossing the line: Women playing rugby union. In J. Nauright and T. J. L. Chandler (Eds.), Making the rugby world (pp. 128–148). Frank Cass.

- O’Neill, D., & Mulready, M. (2015). The invisible woman? Journalism Practice, 9(5), 651–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2014.965925

- Petty, K., & Pope, S. (2019). A new age for media coverage of women’s sport? An analysis of English media coverage of the 2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Sociology, 53(3), 486–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518797505

- Pfister, G. (2015). Assessing the sociology of sport: On women and football. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(4–5), 563–569. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214566646

- Pfister, G., Lenneis, V., & Mintert, S. (2013). Female fans of men’s football – A case study in Denmark. Soccer & Society, 14(6), 850–871. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2013.843923

- Phellas, C. N., Bloch, A., & Seale, C. (2012). Structured methods: Interviews, questionnaires and observation. In C. Seale (Ed.), Researching society and culture (3rd., pp. 181–205).

- Pocock, M., & Skey, M. (2024). ‘You feel a need to inspire and be active on these sites otherwise… people won’t remember your name’: Elite female athletes and the need to maintain ‘appropriate distance’in navigating online gendered space. New Media & Society, 26(2), 961–977.

- Pope, S. (2013). “The Love of My Life”: The meaning and importance of sport for female fans. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 37(2), 176–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723512455919

- Pope, S. (2015). ‘It’s Just Such a Class Thing’: Rivalry and class distinction between female fans of men’s football and rugby union. Sociological Research Online, 20(2), 145–158. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3589

- Pope, S., & Williams, J. (2011). Beyond irrationality and the ultras: some notes on female English rugby union fans and the ‘feminised’ sports crowd. Leisure Studies, 30(3), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2011.566626

- Pope, S., Williams, J., & Cleland, J. (2022). Men’s football fandom and the performance of progressive and misogynistic masculinities in a ‘New Age’ of UK women’s sport. Sociology, 56(4), 730–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/00380385211063359

- Premiership Rugby. (2022, June 23). Premiership rugby breaks TV audience records at the end of an unforgettable season. https://www.premiershiprugby.com/news/premiership-rugby-breaks-tv-audience-records-at-the-end-of-an-unforgettable-season

- Puwar, N. (2005). Space invaders: Race, gender and bodies out of place. Berg.

- Theberge, N. (1994). Toward a feminist alternative to sport as a male preserve. In S. Birrell & C., L. Cole, Women, sport and culture (pp. 181–192). Human Kinetics.

- Tuchman, G., Daniels, A. K., & Benet, J. (1978). The symbolic annihilation of women by the mass media. In Hearth and home: Images of women in the mass media (pp. 3–38). Oxford University Press.

- Wheatley, E. E. (1994). Subcultural subversions: Comparing discourses on sexuality in men’s and women’s rugby songs. In S. Birrell & C., L. Cole, Women, sport and culture (pp. 193–211). Human Kinetics.

- Williams, J., Pope, S., & Cleland, J. (2022). ‘Genuinely in love with the game’ football fan experiences and perceptions of women’s football in England. Sport in Society, 26(2), 285–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2021.2021509

- Women in Sport. (2018). Where are all the women. Women in Sport. https://womeninsport.org/research-and-advice/our-publications/where-are-all-the-women/

- World Rugby. (2022, December 14). 2022: A record-breaking year for women’s rugby. https://www.world.rugby/news/778303/2022-a-record-breaking-year-for-womens-rugby

- Wrack, S. (2021, March 22). ‘A huge step forward’: WSL announces record-breaking deal with BBC and Sky. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/football/2021/mar/22/a-huge-step-forward-wsl-announces-record-breaking-deal-with-bbc-and-sky

- Wright, J., & Clarke, G. (1999). Sport, the media and the construction of compulsory heterosexuality: A Case Study of Women’s Rugby Union. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 34(3), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269099034003001

- YouGov. (2022, August 1). Half of Britons likely to watch women’s football following Lionesses triumph. https://yougov.co.uk/topics/sport/articles-reports/2022/08/01/half-britons-likely-watch-womens-football-followin