Abstract

This paper examines the representation of Sámi sport in Norwegian media by applying a Nordic-informed ‘critical ethnicity theory’, and a media framing perspective. The study extends previous analyses that have focused on media stereotyping of Indigenous athletes to explore how the media represent Sámi sport. Drawing from a combined quantitative and qualitative analysis of Norwegian print media from 1994-2017, Sámi sport is represented as both a unique organisational phenomenon and as part of the overarching Norwegian sport context. Three main findings are revealed. First, Sámi sport has shifted from being an exotic exhibit to being framed as a potential partner for mainstream (Norwegian) sport within specific contexts, such as during an Olympic bid process. Second, there is an emerging tension between the understanding and celebration of Sámi sport as something exclusive within Norwegian society and its potential to be inclusive via organisational mergers. Third, the findings illustrate the need to recognise that Sámi culture, including sport, also spans Sweden, Finland, and Russia thus any structural reorganisation creates consequences across multiple state borders. Overall, the results indicate several co-existing, and sometimes competing and contradictory representations, all of which must consider the postcolonial conditions of the Sámi as an Indigenous people.

Introduction

Sport is a strategic site for the media representation of a wide range of identities, including Indigenous identities. This is evident during the opening ceremonies of sport mega-events, such as the Olympics and other fixtures of national sporting significance (Hogan, Citation2003; Puijk, Citation2000). Numerous studies have highlighted the contested terrain of these high-profile moments where nations seise the opportunity to raise their profile on a global stage (Erueti et al., Citation2023; Wenner & Billing, Citation2017). These moments often involve the incorporation of a wide range of historical and contemporary cultural signifiers, but almost without fail there is an attempt to express and represent the national identity. Such expressions pose an immediate challenge as there is invariably a desire to represent the uniqueness of the nation ‘out of difference’ to others, while simultaneously demonstrating how inclusive it is with respect to a range of identities including: gender, race/ethnicity, (dis)ability, age and, increasingly within the context of postcolonialism, Indigenous identity (Angelini et al., Citation2012; Bairner, Citation2001; Jackson, Citation1998).

A cursory overview of the literature suggests that media representations of ‘the Indigenous’ can often display mixed and incongruous perspectives. Some representations for example, may appear as simple ‘descriptions’ with the assumption that journalistic reporting is objective. In other instances, media representations appear to play a role in marginalising and reproducing negative stereotypes. Yet at other times, Indigenous representations can operate as forms of resistance by challenging historical and contemporary transgressions and proactively portraying Indigenous people in positive and empowering ways (Allen & Bruce, Citation2017; Hokowhitu & Devadas, Citation2013; Walters & Jepson, Citation2019). In short, there can be ambiguous, oppressive and empowering, media representations of Indigenous people across a range of countries and across a range of sectors: politics, economics, health, education and sport. Ultimately media representations are important because they are sites of power (Hall, Citation1997), enable and constrain visibility and voice, and operate as a contested terrain.

Media representations of Indigenous peoples can play a strategic role in changing attitudes and structures (Mackley-Crump & Zemke, Citation2019). As Walters & Ruwhiu (Citation2021) note, it is important to recognise ‘the power of the media to choose the perspectives that are given voice’ (p. 136) as this constructs a particular social reality as ‘true’, despite evidence of a different reality (Denzin, Citation1996). Consider the 2017 World Indigenous Nations Games in Canada as an example. While media reports provided public attention for Indigenous peoples and their challenges as marginalised minorities, critics likewise questioned whether the event was exploited as a tool of legitimacy for the Canadian state (Chen et al., Citation2018). Another example of this variability in media-constructed attitudes and structures regards the negative stereotypes of Māori (Hokowhitu, Citation2013; Hokowhitu & Devadas, Citation2013; Nairn et al., Citation2011), that focus on undesirable attributes and a lack of stories about Māori, by Māori (Allen & Bruce, Citation2017; Hippolite & Bruce, Citation2010; MacDonald & Ormond, Citation2021; Stewart-Withers et al., Citation2024).

While similar patterns of Indigenous stereotyping within the media are evident elsewhere (e.g. Carlson, Citation2013; Carlson et al., Citation2017; Carlson & Frazer, Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Paraschak, Citation1997, Citation2013; Rowe & Boyle, Citation2021), there are contextual nuances (Phelan & Shearer, Citation2009) and signs of change in New Zealand. In 2020, a media consortium (Stuff.co.nz) made a public apology for its negative coverage of Māori historically and pledged to improve its content and reporting. Stuff media’s website now has a special section for Māori-related news and interest stories (Stuff, Citationn.d.). However, alongside this positive change fresh challenges are emerging that raise both enduring and new questions. How can media balance the need to represent the uniqueness of Indigenous culture without reproducing stereotypes? How can the media remain objective in reporting statistics on crime, poverty and other social indicators without falling into the trap of representing a deficit versus a strength-based model (Matheson, Citation2017) that often overlooks important factors such as poverty and other inequalities?

Overall, media representations of Indigenous peoples matter in relation to the construction of public perceptions that can, in turn, induce political (in)action (Jackson & Andrews, Citation1999). Leaning on an understanding of media as crucial in constructing identities and demarking policy agendas (McCombs & Shaw, Citation1972) and the media framing of Indigenous peoples (e.g. Sant et al., Citation2016), this paper examines the contested terrain of representations of Sámi sport in Norwegian media. Sámi are the Indigenous people of the North Calotte (northern parts of Norway, Sweden, Finland and the north-western part of Russia). Historically, mainstream media coverage of the Sámi has been ‘characteristically scant’ (Pietikäinen, Citation2001, p. 644) and focused on negative stereotypes (Lidström, Citation2019), which ‘seems to apply to all four countries having a Sami minority’ (p. 644). Peterson (Citation2003) revealed that the Norwegian population generally knows little about Sámi culture, likely because: ‘Sámi are underrepresented in national Norwegian media content and production’ (p. 294).

However, Skille (Citation2022) showed how Sámi athletes in Norway are increasingly viewed as contributing to the development of both the Sámi and the Norwegian identities and nations through their participation on both national teams. This may signal a shift whereby mainstream understandings and representations of Sámi are becoming more complex as against the previous dichotomies presenting Sámi in stereotypical terms and in opposition to a Norwegian identity. We aim to advance this nuanced plurality by employing a Nordic-informed ‘critical ethnicity theory’ (Dankertsen, Citation2019; Eide & Nikunen, Citation2011; Keskinen et al., Citation2019; Keskinen & Andreassen, Citation2017; Mulinari et al., Citation2009) and media framing perspectives. To date, much of the media research on sport and Indigenous populations has focused on the negative portrayals, including stereotypes, of Indigenous athletes and rather than undertaking analysis of how the media represents Indigenous sport organisations, policies and institutions. As such, this study fills a gap by exploring how the media represent Sámi sport, as both an organisation and cultural institution.

The analysis scrutinises the Norwegian print media 1994-2017, to examine how Sámi sport is represented as both a unique organisational phenomenon and as part of the overarching Norwegian sport context. The paper is divided into five sections including: Context, Theory, Method, a Results and Discussion section before Concluding Remarks.

Context

Following calls from Indigenous researchers and communities, it is imperative to be culturally aware, respectful and specific when researching Indigenous matters (Berryman et al., Citation2013; Fox & McDermott, Citation2019; Harvey, Citation2017; Newhouse, Citation2004; Palmer & Masters, Citation2010). According to Indigenous methodology (Smith, Citation1999), Fox (Citation2006) underscores that research must be contextualised, acknowledge Indigenous self-determination and thus requires ‘complex understanding’ (Newhouse, Citation2004, p. 143) of various perspectives and their interdependencies. Here, acknowledging complexity must be intimately related to the specific context from which knowledge has developed; context complements the post-colonial conditions that impact the media representations of Indigenous sport in Norway (Skille, Citation2021, Citation2022). In light of these points, we urge caution in trying to generalise and/or to extrapolate any findings from research about Sámi to other Indigenous groups for comparative purposes.

Sámi ethnicity is estimated to have originated approximately 2,000–3,000 years ago (Hansen & Olsen, Citation2004); consequently, Sámi people lived on the land long before ‘national’ borders were drawn. Today Sápmi – ‘Sámi land’ – continues to span state borders. In Norway, the Sámi population is scattered, with core areas in the northernmost county – Finnmark. Core areas refer to places with higher densities of Sámi populations, with more everyday use of Sámi language, and the location of formal institutions (the Sámi parliament, the Sámi university, the Sámi broadcaster, and a court facilitated for Sámi language). Within Norway, Sámi history is intertwined with the welfare state. Sámis and Norwegians are both citizens of Norway, sharing rights (social security, free health care, etc.) and duties (taxes, national service, etc.). Through much of its modern history (appr. 1850-1950) the Norwegian state’s universalistic approach aimed to assimilate Sámi through strict policies. Although Sámi were not colonised through violent physical coercion (Berg-Nordlie et al., Citation2015), they did experience a ‘cultural colonisation’ via prohibition of their language in schools (Åhrén, Citation2014). This ‘Norwegianization’ process followed the passing of the state constitution in 1814 and was further reinforced following independence from Sweden in 1905. Nevertheless, Sámi resisted cultural colonisation with Sámi cultural practices and political consciousness seeing a renewal after the Second World War (Andresen et al., Citation2021).

Both domestic issues and an international Indigenous movement increased the consciousness of Sámi identity especially during the 1960s and 1970s (Andresen et al., Citation2021). Specifically, the Norwegian authorities’ plans for a large-scale hydroelectric construction in core Sámi areas, became ‘a clear target for Sámi mobilization’ (Falch et al., Citation2015, p. 129). Protests ‘became a symbol of the Sami fight against cultural discrimination and for collective respect, for political autonomy and for material rights’ (Minde, Citation2002, p. 122). In the aftermath, a state-commissioned Sámi Rights Committee proposed ‘the creation of a directly elected representative body for the Sámi in Norway’ (Falch et al., Citation2015, p. 130). Consequently in 1987, the Norwegian Parliament passed the Sámi Act with Indigenous rights incorporated into The Constitution in 1988. The Sámi Parliament opened in 1989, and the United Nations convention on Indigenous and tribal peoples (ILO convention 169) was ratified by the Norwegian parliament in 1990.

Today, Sámi in Norway refers both to individuals and to an Indigenous people. Sámi individuals participate in Norwegian mainstream organisations (e.g. political parties and sport clubs) and within separate organisations, such as those for sport. The present situation is post-colonial; formal, state-sanctioned efforts towards assimilation are over, but the impacts endure. One legacy of the Norwegianization process lies in the disparate levels of language fluency and cultural practices among the Sámi because assimilation policies impacted differently across geographical areas (Andresen et al., Citation2021; Skille, Citation2022). This is key for our theoretical choices and for understanding the media representations presented below.

Theoretical framework

To analyse the media representations of Sámi sport, we first consider Indigeneity as a social construction of ethnicity (inspired by social construction of race; Maslin, Citation2002; Rex, Citation1970) and then combine this with a framing perspective for media analysis (Benford, Citation1993; Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Snow et al., Citation1986).

Ethnic categories are socially constructed and based on political and cultural criteria. As such, Indigeneity relies on information that creates and reinforces ideas about a particular group for the general public and which also includes hierarchies between and within groups (Gitlin, Citation1980; Li, Citation1994, Citation1998; Niezen, Citation2003, Citation2009). Consequently, the media can reinforce the interests of a dominant group (Allen & Bruce, Citation2017; Seippel et al., Citation2016). More specifically, we employ a ‘critical ethnicity theory’, which can be considered a ‘Nordic version’ of critical race theory, where ‘othering’ is a fruitful concept for analysing Indigeneity (Dankertsen, Citation2019; Dankertsen & Kristiansen, Citation2021). The mechanisms and narratives typically observed in international race research are somewhat softened within the Norwegian context; instead of the word race, Norwegians use labels such as ‘ethnic’, ‘immigrant’, ‘Muslim’, ‘Sámi’, etc. Nevertheless, opinions about sport are politicised when expressed in the media (Stenling & Sam, Citation2017, Citation2019), ‘by linking specific practical problems to more general ideological master narratives’ (Seippel et al., Citation2016, p. 442).

Regarding frames, Snow et al. (Citation1986) employ Goffman’s (1974, p. 21) idea of ‘‘schemata of interpretation’ that enable individuals ‘to locate, perceive, identify, and label’ occurrences within their life space and the world at large’ (Snow et al., Citation1986, p. 464; cf. Linström & Marais, Citation2012). Our study of Sámi sport involves the process of identifying how the media expresses opinions and analysing how such expressions connect with political strands in the Sámi-Norwegian context. Following Benford & Snow (Citation2000) we propose three tasks as central for framing. The first task is to provide a diagnosis of the status of Sámi sport in relation to Norwegian sport, the Norwegian state, and Indigenous issues more generally. This provides an important foundation from which to better understand the contested terrain of media representation of Indigenous culture in Norway. The second task is to identify within these frames, solutions on how to fix any identified issues or challenges; here, that means discussing how Sámi sport contributes to reconciliation (or – vice versa – how it reinforces colonial power). The latter leads to the third framing task, which is to identify or interpret the frame’s motivation(s), which connects to cultural appropriateness and can relate to power relations and hierarchies – surrounding Indigenous people and within the group itself. Taken together, these framing tasks will help explore how media representations reveal the construction of Indigenous sport, including its ‘political assumptions, ideology, social values, cultural and racial stereotypes and assumptions as well as [its] specific textual strategies’ (Parisi, Citation1998, p. 239).

Methods

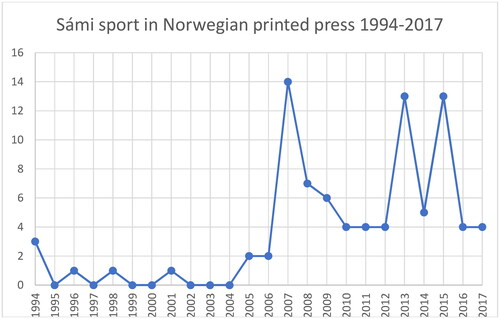

To empirically map the media representation of Sámi sport in Norway, we engaged in a defined search of Norwegian newspapers. We applied the database ‘Atekst’, which covers close to all printed Norwegian media sources since 1945 (3075 Nordic sources all together). Every national and local Norwegian newspaper is accessible in Atekst, the leading Norwegian media monitoring service offered by university libraries (Retriever, n.d.). The search phrase employed was ‘Sámi sport’ (as a united phrase, ‘samisk idrett’ in Norwegian language); a term applied in everyday speech as well as in formal documents. The search resulted in 90 unique newspaper articles, between 1994 (when Sámi sport was featured as part of an exhibition at the Lillehammer winter Olympic games), until 2017 (the last year before a significant increase of media representations of Sámi sport, which needs a separate study).We first conducted a quantitative and geographical contextualisation in order to assess where and when newspaper articles about Sámi sport were published. Norway is geographically elongated, and the Sámi population is scattered. Since the newspaper articles stem primarily from the north, where Sámi density is highest, we explicitly state when national (Norwegian) newspapers are utilised.Footnote1 Results of the timeframe are visualised in , showing three peaks, which, in turn, guided the main qualitative analysis. Regarding the latter, following Braun & Clarke (Citation2006) we conducted a five-step thematic analysis. The first phase was an open-ended reading of media articles, in order to become familiar with data. This was done by the first author, a native Norwegian growing up in Sápmi. The second and the third phases flowed seamlessly into each other with the first author conducting a closer reading of the articles and developing preliminary codes that formed three themes: (i) Tromsø Olympics, (ii) Finnmark sport, and (iii) reorganisation of Sámi sport.

In practical terms, he identified extracts from the media texts and included them in the early result draft. In phase four, the second and third authors joined the process and reviewed the main themes in order to advance the three tasks (Benford & Snow, Citation2000). Subsequent analysis with discussions in the author team continued to and followed a transition to phase five where the final themes were confirmed: (1) ‘Sámi sport as a justification for the Olympics’ (2007); (2) ‘Sámi sport and Norwegian sport in Finnmark’ (2010 and 2013); and (3) ‘Reorganisation of Sámi sport’ (2015). Further conversations among the authors created nuances within each theme (as per the presentations in the Results and Discussion section). We sought qualitative content that aligned with, and added meaning to, the quantitative peaks in ; and how that content constructed Sámi sport as both an Indigenous phenomenon and a sport phenomenon (see Garland & Rowe, Citation1999; Jackson, Citation1998; Outlaw, Citation1999).

We are aware of limitations beyond those typically associated with media framing analysis including the limitation of a specific time period and the effectiveness of the ‘Atekst’ data base; and, since only the first author is fluent in Norwegian it is possible that meaning could have been lost in translation (in the transition from phase 3 to phase 4). Nevertheless, the paper contributes to the field through a supplementation of previous research into media representations of Indigenous sport in Norway.

Results and discussion

In this section, we first consider the media representations on an overall level and in quantitative terms. Then we move into a qualitative interpretative analysis of each of the three peaks in . A search of the development of representations of Sámi sport in Norwegian media yielded 90 articles featuring Sámi sport spanning a 24-year period, between 1994-2017. That this amounts to less than four articles per year on average, suggests a marginalisation of Sámi sport, which aligns with research into media representations of the Sámi people more generally (Pietikäinen, Citation2001, Citation2003, Citation2008). The overall impression is reinforced by the fact that the first article featuring Sami sport appears in 1994, and in relation to the Olympic Winter Games in Lillehammer where two typical Sámi sport disciplines (reindeer racing and lassoing) were exhibited during the opening ceremony (Nordlys, 22 January 1994). Thus, an ambiguity is evident, between a national pride with respect to integration and the exploitation of the Indigenous people in the staging of Norwegian unity and pride. Indeed, according to Puijk (Citation2000), ‘the organizers’ version of national identity was based on a particular way of defining Norwegianness – connected to equality, closeness to nature, a sport-loving nation’ (p. 325). The Viking era or the oil production, were not mentioned. ‘Nor was the multiracial country emphasised, although the Sami population was presented as a well-integrated ethnic minority’ (Puijk, Citation2000, p. 325).

shows three peaks: 2007, 2013 and 2015. Each of them is associated with events that reflect broader issues of Indigenous representation. In 2007, Sámi sport again touched the Olympics, when it became the subject of debate concerning a bid to host the games in Tromsø in 2018. In contrast, the peak in 2013 surrounds a series of articles on sport politics written by a single author,Footnote2 which relate to a similar series of pieces by the same author published in 2010. The third peak in 2015 stemmed from a Sámi parliament’s plenary session held in the Norwegian parliament including a key agenda item concerning the re-organisation of Sámi sport.

2007: Sámi sport as an argument for the olympics

In 2007, half of the 14 articles were about Sámi sport and its relationship with the potential bid for the 2018 winter games. The debate about a Norwegian bid included three competing cities: Oslo, Trondheim, and Tromsø. The media articles must be understood, both in relation to whether Norway should bid for the games at all, and as part of an internal competition between Norwegian cities. Sámi sport, and Sámi as an Indigenous people, became a focus of the arguments for Tromsø, the most northern of the three candidate cities and the only one in Sápmi.

The media articles can be framed in three ways, surrounding themes of: 1) ‘Sámi as a sales tactic’, 2) Sámi as beneficiaries of integration, 3) Sámi as variously oppressed, exoticized and empowered. First, Tromsø ‘sold’ the Indigenous people in its competition among potential host cities because Sámi sport offered a competitive benefit against the other Norwegian cities. Consider quotes from two different Tromsø based newspapers: ‘The Winter Games in Tromsø will show Indigenous people’s presence by the involvement of Sámi interests and actors … Sámi sport is engaged, and the Sámi Parliament has given broad support’ (Bladet Tromsø, 19 February 2007); and, the (Norwegian) Sámi Parliament supported the Olympic bid, which referred to the fact ‘that only Tromsø has included the Sámi [people] in its application’ (Nordlys, 7 March 2007). In these excerpts, Tromsø celebrated the Indigenous people as an instrument to gain bid advantage.

Moreover, support came from three former Sámi Parliament presidents who stated: ‘Choose North Norway and Sápmi (the land of the Sámi)’ because ‘Tromsø 2018 adopted Indigenous perspectives, due to equity and regional benefits of the games’ (VG, 29 March 2007). They pinpoint that the Sámi bid includes support from the Sámi parliamentary council (a cooperative organisation between the Sámi parliaments in Norway, Sweden Finland, and representatives of Sámi organisations in RussiaFootnote3), which highlights that Sámi issues are not solely a Norwegian phenomenon but should be considered on a Sápmi level (across state borders). Another Norwegian national newspaper noted that Tromsø was the host of the world’s first ski race in 1843 and that ‘Sámis were among the first skiers’. It was further argued that with Olympic Games in Tromsø, the ‘Arctic people’s sport disciplines’ would finally reach a broader audience (Dag og Tid, 23 March 2007).

As a second frame, Sámi sport is represented as a prime beneficiary from an Olympic legacy. One claim stated: ‘Large consequences for Sámi sport are included in the value budget. Sámi sport [organisation] participates as a full worthy member of the [mainstream sport system] organisation. Sámi sport receives sports-related and organisational competence’ (Nordlys, 19 February 2007). Specifically, one of the sport halls planned in Tromsø is, ‘in cooperation with the Sámi community, planned to move to Kautokeino or another Sámi municipality’ after the games (Nordlys, 19 February 2007). Ultimately, both Sámi and Norwegian sport organisations considered the Olympic games as a mechanism for more and faster state funding for sport facilities; a framing that can be interpreted as opportunistic by leveraging Sámi sport as a strategic way to strengthen the legacy of the Olympic games. However, this opportunism is tempered and transformed into a positive by framing the initiative as a win-win for both Norwegian sport and Sámi sport.

The third framing category of Sámi sport in relation to the Olympic bid includes criticism of exhibiting Indigenous sport as exotic, compared to the ‘real’ and competitive sports at the games. Asserting that ‘Indigenous peoples cannot only be decorations at opening ceremonies’, a Norwegian national newspaper proposed to send a delegation of Sámi athletes under the Sámi flag to the Tromsø Olympics. ‘The time should therefore be ready for Sámi and other Indigenous peoples to have their own delegations to 2018. The Olympic charter is open for that’; an idea that several Sámi parliament representatives were excited about (Aftenposten, 17 September 2007). Although there was no sign of the idea advancing further, a Sámi delegation could have conceivably become a part of major sport events, as there are a number of contemporary precedents. The IOC for example, allows a Refugee team (of people without citizenship; Burdsey et al., Citation2023) while the World Lacrosse Championships includes Canada, the USA and a ‘Six Nations’ Indigenous team (the Haudenosaunee Nation) with players that span borders (World Lacrosse, n.d.).

Beyond this hypothetical possibility, the separate Sámi delegation proposition and its social construction in the media raises important questions around the subject of ‘othering’ (Dankertsen, Citation2019; Dankertsen & Kristiansen, Citation2021)? On one hand the media’s suggestion of a separate delegation could be intended as an empowering form of ‘othering’ – that is, utilised as a genuine effort to recognise Sámi identity rather than a political strategy to demonstrate inclusiveness and enhance bid success. Indeed, given the Sámi sport organisation’s active role in the 2018 Olympic bid process, this framing could be interpreted as a step forward in the reconciliation process, giving the Indigenous people autonomy and their own space within the Norwegian state’s project. Importantly, the diagnosis of a problem (Sami as ‘decorations’) along with a hypothetical solution (to have Sami march under their own flag) support this wider frame of autonomy. However, it is unclear whether the motivation was indeed the empowerment of the Sami per se, or whether the framing was still tied to advancing an Olympic bid. Thus, the discussion relates to whose perspective is being reflected in any notion of progress of reconciliation. In other words, the framing process depends on who is doing the framing (Benford, Citation1993; Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Snow et al., Citation1986).

On the other hand, the media representation of Sámi sport can be critically interpreted as a continuation of the Norwegian authorities’ colonisation of the Indigenous people by essentializing and exploiting them as the exotic ‘Other’ (Pettersson & Viken, Citation2007) akin to the enduring legacy of Sámi culture exhibited at the 1994 Lillehammer Winter Games. It is also possible that both processes are occurring simultaneously. As Hogan (Citation2003) identifies, there may be at least three ‘winners’ within Olympic opening ceremonies: commercial interests, the dominant groups (reifying the existing social order), and the state (representing the national brand including the dimension of inclusion). Thus, it is possible for the ceremonies to ‘mirror relations of dominance’ and ‘legitimize … hierarchies of power’ but, as Hogan also adds: ‘In co-opting the Other (internal minorities or foreign others), Olympic opening ceremonies create the opportunity for counter-hegemonic readings of their narratives of nation’ (Hogan, Citation2003, p. 119).

Ultimately, the key issue is whether Sámi sport is being used by Norwegian sport interests versus how Sámi sport uses Norwegian sport for its own interests – or both simultaneously. We might consider the Sámi-state ‘relationship’ as a ‘negotiation’ and ‘accommodation’ given that, while each side has its own objectives, both recognise that to win public support and maintain legitimacy, require cooperation. Thus, we suggest that the politics of ‘othering’ is part of a wider process of Sámi identity recognition through the representation of uniqueness and distinctiveness relative to mainstream Norwegian society. However, it is difficult to disentangle this from either the bidding strategy or an overall goodwill. Below, we return to the question of stereotypes and Sámi sport as a representation of the savage (Lidström, Citation2019), versus real integration with the mainstream sport system.

2010 and 2013: Sámi sport and Norwegian sport in Finnmark

In 2010 and 2013, the topic of Sámi and Norwegian sport organisation in Finnmark appeared in seven media stories (three in 2010 and four in 2013, respectively). These articles were written by Nils Peder Eriksen, a spokesman for both Norwegian and Sámi sport organisations who came from a Sámi village in Finnmark. The context for these articles surrounds the co-existence of ‘mainstream’ sport (as a connected, nation-wide system of organisations) along with Sámi sport organisations (a similar but much smaller system connecting Sámi clubs and members). Importantly, both systems are coordinated by their own umbrella organisation: the Norwegian confederation of sports (Norwegian acronym in everyday use: NIF) in the case of the former, and the Sámi Valáštallan Lihttu (SVL) in the case of the latter. In that context, the author observed that, ‘Sámi sport is also Norwegian sport, at least in Finnmark’ (Altaposten, 14 May 2010; Finnmark Dagblad, 15 May 2010) and ‘Norwegian sport is also Sámi sport, at least in Finnmark’ (Altaposten, 2 June 2010). Eriksen held that the NIF was not suited to conduct its mission in multi-ethnic Finnmark, which he calls ‘the region of special arrangements’ and claimed that ‘Sport in Finnmark must have special arrangement conditions to make it’ (Altaposten, 14 May 2010; Finnmark Dagblad, 15 May 2010). Accordingly, Sámi and Norwegian sport organisations suffer similar challenges around the county’s particular Indigenous makeup; and they should therefore – according to Eriksen – share solutions.

A year later, the Norwegian government launched a white paper on sport, entitled ‘The Norwegian Sport Model’ (Ministry of Culture, 2011). In a play on words of the white paper’s title, Eriksen issued two articles entitled ‘the Sámi sport model’ (Altaposten, 5 March 2013) and ‘the Finnmark sport model’ (Altaposten, 22 March 2013). Combining information about Sámi sport and demographic developments – including increased multiculturalism and greater acceptance of the Sámi people – he proposed a merger of Sámi sport with Norwegian sport to focus upon social mass sport and Sámi cultural features. ‘The profile’ of Sámi sport, Eriksen holds:

…is of social character, as bearer and disseminator of Sámi culture, tradition, societal life and industry conduct. Sámi sport thus has an approach which is closer to the ‘sport’s societal responsibility’ (health, social, school, industry) than Norwegian sport has (Altaposten, 5 March 2013).

Eriksen thus proposes to increase Sámi sport’s status by merging it with Norwegian sport and positions both alongside other societal elements (e.g. health and education):

Sámi and Norwegian sport organizations need to work jointly for sport in Finnmark. Accordingly, a shared organizational and administrative alliance for all physical activity and recreation in Finnmark should be a goal. The small resources should be united (Altaposten, 22 March 2013).

Overall, the media articles are framed as solutions, insofar as they focus on ‘ethnic-neutral’ aspects of efficiency, resources and re-organisation. They challenge the current organisation of Sámi sport, particularly in Finnmark. In doing so, the articles are directed at wider political dynamics by focusing on Sámi culture – characterising the culture as a ‘weak’ Finnmark within Norway and a weak Sápmi across Nordic countries. Following Benford & Snow (Citation2000), the diagnosis and attributional cause for this weakness in sport is argued to be a duplication of organisations that operate as silos and that generate double workload. However, when it comes to the frame’s motivation, the analysis is less clear. The proposed merger can be considered an act of efficacy but can also be interpreted as respectful and inclusive because it advances a multi-ethnic community based on other criteria than ethnic borders (a Sámi versus a Norwegian sport organisation).

Considering the specific context of the region, this ‘call to arms’ introduces some questions of commensurability between the proposal and the lived experiences of Sámi. First, a merger of Sámi and Norwegian sport organisations could risk Sámi sport becoming an invisible minority within a Norwegian sport organisation. Second, equating the county of Finnmark with Sápmi (the land of the Sámi) could be viewed as reductionist and may exclude other areas of Sápmi from becoming legitimate and recognised members of the Indigenous region, community or culture. Finnmark is the region with highest Sámi density, but it is not the only region with Sámi inhabitants; thus, the focus on Finnmark may have some unintended consequences, most notably a kind of ‘othering’ of Sami residing in Southern parts of Norway. Nevertheless, the 2010 and 2013 articles represent a further step (from the 2007 articles) regarding potential cooperation between Norwegian and Sámi sport organisations; and thus, a potential reconciliation between the coloniser and the colonised.

2015: Reorganisation of Sámi sport (Sámi sport in the Norwegian Parliament)

In 2015, there were two interrelated topics in the media representation of Sámi sport. First, several newspapers highlighted the location of one of Sámi parliament’s plenum meetings; namely in the Norwegian Parliament in Oslo, the capital city of Norway located in the south (e.g. Finnmark Dagblad, 1 September 2015). Second, the content of the Sámi parliament’s meeting in Oslo comprised an agenda item concerning Sámi sport. Regarding the meeting’s location, multiple interpretations are possible, and they may be equally valid – depending on perspective. The meeting in the Norwegian Parliament can be seen as framing a good relationship between the authorities of the country and the Indigenous people; and it can be interpreted as the authorities’ framing of hegemonic power of being in a position of ownership towards the Sámi people. However, the media presented different opinions on this issue; several newspapers printed an article written by an ‘anti-Sámi’ reader who criticised the Norwegian state’s overwhelmingly positive Sámi policy and called the trip to Oslo a ‘charm offensive’ by Sámi politicians to win favour with Norwegian authorities.

Regarding the meeting’s content, representatives shared a media release stating that: ‘The Sámi parliament council is concerned with facilitating, especially for children and youth, common arenas and sporting meeting places’ (Finnmark Dagblad, 25 September 2015). It continued: ‘For the council it is important to have arenas where Sámi culture and language are included in a functional and natural way’ (Finnmark Dagblad, 25 September 2015). A major outcome of the Sámi parliament’s focus on Sámi sport at the Oslo meeting, was a specific sport policy publication (Sámi parliament, 2015) and a subsequent proposal for reorganisation. The particular organisational concerns stemmed from the existence of duplicate reindeer racing organisations; thus, the Sámi parliament proposed a complete reorganisation of all Sámi sport – across Norway, Sweden, and Finland (Sámi parliament, 2015).

Taken together, the media articles can be interpreted in various directions: from the perspective of the Norwegian coloniser or from the colonised Sámi, and with varying nuances. Owing to the specific context, our analysis appears to contrast from what others have found. Whereas in Canada for example, the media portrayal of Aboriginal Peoples focuses on ‘economic and social marginalisation’ (Maslin, Citation2002, p.20), our analysis matches the observation that Sami appear ‘so rarely in the news that public discussion about them hardly [exists]’ (Pietikäinen, Citation2003, p.603). This makes the Norwegian media’s acknowledgement of Sami sport all the more notable, as sport appears as a strength-based fulcrum to advance competing frames. Thus, Sámi sport’s mediated connections to Norwegian sport mirrors Sami-Norwegian representations more broadly.

As Pietikäinen (Citation2001, p. 652) observes: ‘The typical representation of the Sami has been “bipolar”’ (p. 652): sometimes as an Indigenous with specific rights and versus non-Indigenous without uniqueness – or as a target for assimilation. As such, a ‘“Contested Sami” identity representation’ (Pietikäinen, Citation2003, p. 604) is often opposed to the majority. Moreover, there are unquestioned internal hierarchies within some media frames such as those that elevate the interests of Sámi in Finnmark as more legitimate than Sámi residing elsewhere. Insofar as these hierarchies may be taken-for-granted; we can say that dominant groups subordinate ‘the other’, both directly and indirectly. Indeed, the focus on Finnmark in the representations of Sámi sport can be seen as a ruling group’s ‘domination of subordinate … groups’, which takes place ‘through the elaboration and penetration of ideology (ideas and assumptions) into their common sense and everyday practices’. In other words, where Finnmark is framed as equivalent to a Sápmi approach, the frame can be interpreted as part of a ‘systematic … engineering of … consent to establish order’ (Gitlin, Citation1980, p. 253).

Thus, the media assists as a source for such mechanisms because it allows the elite to manipulate elements of information (van Dijk, Citation1997). Therefore, the scarcity of Sámi sport in the media facilitates a silent reproduction of power relations, with respect to both Norwegian versus Sámi, and between Sámi groups. Following Andresen et al. (Citation2021), it is crucial to overcome the ‘Finnmark fetishism’ that has dominated Sámi research. Thus, two interrelated points from the 2015 articles move the overarching discussion about Sámi sport beyond the organisational arrangements of sport. One regards the hegemony of Sámi sport disciplines; and the other considers the relationship between various countries of Sápmi (Skille et al., Citation2023)

Concluding remarks

This study aimed to answer the following research question – How is Sámi sport represented in Norwegian media? The short version of the answer is: generally positive, at least on a superficial level, yet ambivalent because there is room for multiple, apparently mutually exclusive, interpretations. Although it is difficult to judge each newspaper article regarding the perspective of authors, target group and intended impact, we have taken as given that to enter the publicly mediated space, a narrative must pass through a ‘filter’ in order to meet the publisher’s agenda. In that respect, we see small signs of change from a less colonial attitude aiming at national unity (considering the Sámi as a minority that needs to be integrated in the Norwegian nation), to an acceptance of the Sámi people as a separate nation. Thus, this paper reveals differences in media representation of Indigenous people compared to those reported in previous studies, which tend to focus on sensationalistic news items based on stereotypical dimensions of an ethnic group (Allen & Bruce, Citation2017; Lidström, Citation2019; Walters & Jepson, Citation2019).

Being cautious about generalisations, we find both similarities and differences when undertaking a cursory comparison of our findings with former research. However, the empirical phenomena identified can be considered double-edged swords (Walters & Ruwhiu, Citation2021). For example, Sámi sport in Tromsø’s Olympic bid process (the 2007 articles) and the initiative to reorganise Sámi sport (the 2015 articles) can be considered empowering the Indigenous (Mackley-Crump & Zemke, Citation2019). Conversely, both Sámi sport’s involvement in the Olympic bid as a potential ‘sales trick’ (the 2007 articles) and the proposal of merging Sámi and Norwegian sport organisations (the 2010 and 2013 articles) can be conceived of as having potential negative consequences for Indigenous sport and people. Indeed, it could be seen as exploitation of an Indigenous people to promote state interests, as in the case of the Indigenous games in Canada in 2017 (Chen et al., Citation2018). One of the consequences of this is often evident where others speak more about Sámi than with them, which used to be the situation for the Māori in New Zealand (Allen & Bruce, Citation2017). Nevertheless, the inclusion of Sámi sport in various societal ad state matters could also be interpreted as positive change, as in the case of Stuff media’s focus on Māori (Stuff, Citationn.d.).

Ultimately, despite some signs of social change, Sámi sport is principally ‘diagnosed’ (Benford & Snow, Citation2000) as existing only in relation to mainstream sport and Norwegian politics. Rarely is it framed as ‘sport for its own sake’ and its legitimacy tends to be assembled from broader narratives of Indigeneity including essentialising or exotic ‘othering’. Likewise, as a ‘solution’, Sámi sport is a remedy to much larger issues, relating to reconciliation, national unity (as per the Lillehammer Olympics) and parliamentary diplomacy (as per the 2015 articles). Regarding the element of motivation, it is tenable to follow previous research and critically interpret much of these media representations as a form of subordination: between the dominant Norwegian majority and the minority Sámi, and between a dominant Sámi group (based in core Sámi areas) and subordinate Sámi groups. Although formal policies have evolved, unequal treatment continues along lines well summarised by Banton (Citation1967) decades ago: the ideas of race, including ethnicity and Indigeneity, ‘still have a considerable social significance, and when a category is labelled in the popular mind by racial terminology … certain predictable consequences ensue’ (p. 4; see Miles, Citation1993). Thus, one consequence is fragmentation, while another is a need to ‘essentialize’.

This study provides an important contribution to the sociology of sport and for understanding Sámi sport and Indigenous sport more generally, because the media is ‘a vital part of the rejuvenation of Sámi culture’. The concept of rejuvenation is chosen because ‘art forms and media are building a living Sámi culture rather than trying to revive the traditional Sámi way of life tied to reindeer husbandry’ (Peterson, Citation2003, p. 300). There are signs of improving conditions for Sámi sport and the Sámi people compared to their peers in other countries (Berg-Nordlie et al., Citation2015; Pietikäinen, Citation2001, Citation2003, Citation2008; Skille, Citation2022). This is not to suggest that issues and problems have been resolved as tensions clearly remain particularly in relation to social hierarchies. To this extent, the media representation of Sámi remains a contested terrain of power and politics. Thus, researchers may undertake specific comparisons of the media presentation of Sámi sport and mainstream sport (i.e. Norwegian sport in Norway, Finnish sport in Finland etc.).

While the quantity of media representation of Sámi sport has increased over the last five years, it would be useful to explore whether this is evidence of mainstream media recognition and normalisation or whether this is due to the emergence of a new generation, including Sámi journalists who are more aware of the need for equity. With respect to future research, one important area of exploration could track how state sport policy actors treat Sámi sport in Finland, Sweden and Norway in order to determine whether we are witnessing genuine social change or continued patterns of indifference (Skille et al., Citation2023). In addition, there is considerable scope for a line of comparative research that examines how such media representations influence different Indigenous peoples around the world; that is, investigations could explore the perspectives of different groups of indigenous peoples in order to gain insights and give voice to their experiences. However, as cautioned earlier, any such research should consider the importance of acknowledging contextual specificity including the distinct histories, cultures, processes of colonisation and even decolonisation to avoid the risk of overgeneralisation.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Notes

1 In 2007, seven out of 14 articles considered the Olympics; six of them were authored by journalists and one was a chronicle. Among the 2010 and 2013 articles, eight of 17 treated Sámi and Finnmark sport; five were chronicles by one author, and three by journalists. Of the 13 articles from 2015, four announced the Sámi parliament meeting, while three treated the sport content of that meeting (cf. Results and Discussion section).

2 The author was a leader in both Norwegian and Sámi sport. He died in 2013 (one of the articles is an obituary).

3 There is no Sámi Parliament in Russia.

References

- Åhrén, M. (2014). The proposed nordic saami convention: National and international dimensions of indigenous property rights. Nordic Journal of Human Rights, 32(3), 283–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/18918131.2014.937223

- Allen, J. M., & Bruce, T. (2017). Constructing the other: News media representations of a predominantly ‘brown’ community in New Zealand. Pacific Journalism Review, 23(1), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.24135/pjr.v23i1.33

- Andresen, A., Evjen, B., & Rymiin, T. (Eds). (2021). Samenes historie fra 1751 til 2010. In The history of the Sámi 1751-2010. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Angelini, J. R., Billings, A. C., & MacArthur, P. J. (2012). The nationalistic revolution will be televised: The 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games on NBC. International Journal of Sport Communication, 5(2), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.5.2.193

- Bairner, A. (2001). Sport, nationalism and globalization: European and North American perspectives. State University of New York Press.

- Banton, M. (1967). Race relations. Tavistock Publications.

- Benford, R. D. (1993). “You could be the hundredth monkey”: Collective action frames and vocabularies of motive within the nuclear disarmament movement. The Sociological Quarterly, 34(2), 195–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1993.tb00387.x

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing process and social movements. An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Berg-Nordlie, M., Saglie, J., & Sullivan, A. (Eds). (2015). Indigenous politics. Institutions, representation, mobilization. ECPR Press.

- Berryman, M., SooHoo, S., & Nevin, A. (2013). Culturally responsive methodologies. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burdsey, D., Michelini, E., & Agergaard, S. (2023). Beyond Crisis? Institutionalized mediatization of the refugee olympic team at the 2020 olympic games. Communication & Sport, 11(6), 1121–1138. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795221110232

- Carlson, B. (2013). The “new frontier”: Emergent indigenous identities and social media. In M. Harris, M. Nakata, & B. Carlson (Eds.), The politics of identity: Emerging indigeneity (pp. 147–168). University of Technology Sydney E-Press.

- Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2020a). The politics of (dis)trust in Indigenous help-seeking. In S. Maddison, & S. Nakata (Eds.), Questioning Indigenous-settler relations: Interdisciplinary perspectives (pp. 87–106). Springer.

- Carlson, B., Jones, L., Harris, M., Quezada, N., & Frazer, R. (2017). Trauma, shared recognition and Indigenous resistance on social media. Australasian Journal of Information Systems, 21, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v21i0.1570

- Carlson, B., & Frazer, R. (2020b). “They Got Filters”: Indigenous social media, the settler gaze, and a politics of hope. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 1–11.

- Chen, C., Mason, D. S., & Misener, L. (2018). Exploring media coverage of the 2017 world indigenous nations games and North American indigenous games: A critical discourse analysis. Event Management, 22(6), 1009–1025. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599518X15346132863300

- Dankertsen, A. (2019). I felt so white: Sámi racialization, indigeneity, and shades of whiteness. Native American and Indigenous Studies, 6(2), 110–137. https://doi.org/10.5749/natiindistudj.6.2.0110

- Dankertsen, A., & Kristiansen, T. G. S. (2021). “Whiteness isn’t about skin color.” Challenges to analyzing racial practices in a Norwegian context. Societies, 11(2), 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc11020046

- Denzin, N. K. (1996). More rare air: Michael Jordan on Michael Jordan. Sociology of Sport Journal, 13(4), 319–324. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.13.4.319

- Eide, E., & Nikunen, K. (2011). Media in motion: Cultural complexity and migration in the nordic region. Routledge.

- Erueti, B., Grainger, A., & Haldane, H. J. (2023). The marketing and branding of Indigeneity in the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023: Marketing Māori. In A. Beissel, V. Postlethwaite, A. Grainger, & J. E. Brice, (Eds.), The 2023 FIFA women’s world cup: Politics, representation, and management (pp. 158–171). Taylor & Francis.

- Falch, T., Selle, P., & Strømsnes, K. (2015). The Sami: 25 years of Indigenous authority in Norway. Ethnopolitics, 15(1), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2015.1101846

- Fox, K. (2006). Leisure and indigenous peoples. Leisure Studies, 25(4), 403–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360600896502

- Fox, K., & McDermott, L. (2019). A’ohe pau ke ‘ike ka hālau ho’okahi [All knowledge is not taught in the same school] Welcoming Kānaka Hawai’i Waves of Knowing and Revisiting Leisure. Leisure Sciences, 41(4), 330–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1442755

- Garland, J., & Rowe, M. (1999). Selling the game short: An examination of the role of antiracism in British football. Sociology of Sport Journal, 16(1), 35–53. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.16.1.35

- Gitlin, T. (1980). The whole world is watching: Mass media in the making and unmaking of the new left. University of California Press.

- Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices.

- Hansen, L. I., & Olsen, B. (2004). Samenes historie fram til 1750. In Sámi history until 1750. Cappelen Akademisk.

- Harvey, G. (2017). A step into the light: Developing a culturally appropriate research process to study Māori rangatahi perspectives of leisure in one setting. Waikato Journal of Education, 8(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v8i1.445

- Hippolite, H., & Bruce, T. (2010). Speaking the unspoken: Racism, sport & Māori. Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 2(2), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.5130/ccs.v2i2.1524

- Hogan, J. (2003). Staging the nation: Gendered and ethnicized discourses of national identity in Olympic opening ceremonies. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 27(2), 100–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193732502250710

- Hokowhitu, B. (2013). Theorizing indigenous media. In B. Hokowhitu & V. Devadas (Eds.), The fourth eye: Mori Media in Aotearoa New Zealand. Minnesota Scholarship Online. Retrieved July 23, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816681037.003.0006

- Hokowhitu, B., & Devadas, V. (Eds.) (2013). The fourth eye: Māori media in Aotearoa New Zealand. In Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press.

- Jackson, S. J. (1998). The 49th paradox: The 1988 Calgary Winter Olympic Games and Canadian identity as contested terrain. In M. Duncan, G. Chick & A. Aycock (Eds.), Diversions and divergences in the fields of play (pp. 191–208). Ablex Publishing.

- Jackson, S. J., & Andrews, D. L. (1999). Between and beyond the global and the local: American popular sporting culture in New Zealand. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 34(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269099034001003

- Keskinen, S., & Andreassen, R. (2017). Developing theoretical perspectives on racialisation and migration. Nordic Journal of Migration Research, 7(2), 64–69. https://doi.org/10.1515/njmr-2017-0018

- Keskinen, S., Skaptadóttir, U., & Toivanen, M. (2019). Undoing homogeneity in the nordic region: Migration, difference and the politics of solidarity. Routledge.

- Li, P. S. (1994). Unneighbourly houses or unwelcome Chinese: The social construction of race in the battle over ‘Monster Homes’ in Vancouver, Canada. International Journal of Comparative Race and Ethnic Studies, 1(1), 14–33.

- Li, P. S. (1998). The market value and the social value of race. In V. Satzewich (Ed.), Racism and social inequality in Canada: concepts, controversies, and strategies of resistance (pp. 113–130). Thompson Educational Pub.

- Lidström, I. (2019). The development of Sámi sport, 1970–1990: A concern for Sweden or for Sápmi? The International Journal of the History of Sport, 36(11), 1013–1034. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2019.1687451

- Linström, M., & Marais, W. (2012). Qualitative news frame analysis: A methodology. Communitas, 17, 21–38.

- MacDonald, L., & Ormond, A. (2021). Racism and silencing in the media in Aotearoa New Zealand. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 17(2), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801211015436

- Mackley-Crump, J., & Zemke, K. (2019). The FAFSWAG ball: Event spaces, counter-marginal narratives, and walking queer bodies into the centre. In T. Walters, & A. S. Jepson (Eds.), Marginalisation and events (pp. 95–109). Routledge.

- Maslin, C. (2002). The social construction of aboriginal peoples in the saskatchewan Print Media. Monograph, University of Saskatchewan.

- Matheson, K. (2017). Rebuilding identities and renewing relationships: The necessary consolidation of deficit and strength-based discourses. MediaTropes eJournal, 7(1), 75–96.

- McCombs, M. E., & Shaw, D. L. (1972). The agenda-setting function of mass media. Public Opinion Quarterly, 36(2), 176–187. https://doi.org/10.1086/267990

- Miles, R. (1993). Racism after ‘Race Relations’. Routledge.

- Minde, H. (2002). Assimilation of the sami – Implementation and consequences. Acta Borealia, 20(2), 121–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/08003830310002877

- Mulinari, D., Keskinen, S., Irni, S., & Tuori, S. (2009). Introduction: postcolonialism and the Nordic models of Welfare and gender. In S. Irni & D. Mulinari (Eds.), Complying with colonialism (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- Nairn, R., Barnes, A. M., Rankine, J., Borell, B., Abel, S., & McCreanor, T. (2011). Mass media in aotearoa: An obstacle to cultural competence. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 168–175.

- Newhouse, D. (2004). Indigenous knowledge in a multicultural world. Native Studies Review, 15(2), 139–154.

- Niezen, R. (2003). The origins of indigenism: Human rights and the politics of identity. University of California Press.

- Niezen, R. (2009). The rediscovered self: Indigenous identity and cultural justice. McGill-Queens Press.

- Outlaw, L. T. (1999). On race and philosophy. In S. Babbitt & S. Campbell (Eds.), Racism and philosophy (pp. 50–75). Cornell University Press.

- Palmer, F. R., & Masters, T. M. (2010). Māori feminism and sport leadership: Exploring Māori Women’s experiences. Sport Management Review, 13(4), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2010.06.001

- Paraschak, V. (1997). Variations in race relations: Sporting events for Native peoples in Canada. Sociology of Sport Journal, 14(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.14.1.1

- Paraschak, V. (2013). Aboriginal peoples and the construction of Canadian sport policy. In J. Forsyth & A. Giles (Eds.), Aboriginal peoples & sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 95–123). UBC Press.

- Parisi, P. (1998). The New York Times looks at one block in Harlem: Narratives of race in journalism. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 15(3), 236–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295039809367047

- Peterson, C. (2003). Sámi culture and media. Scandinavian Studies, 75(2), 293–300.

- Pettersson, R., & Viken, A. (2007). Sami perspectives on Indigenous tourism in northern Europe: commerce or cultural development? In R. Butler & T. Hinch (Eds.), Tourism and indigenous peoples (pp. 176–187). Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Phelan, S., & Shearer, F. (2009). The “radical”, the “activist” and the hegemonic newspaper articulation of the Aotearoa New Zealand foreshore and seabed conflict. Journalism Studies, 10(2), 220–‐237. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616700802374183

- Pietikäinen, S. (2001). On the fringe: News representations of the sami. Social Identities, 7(4), 637–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504630120107746

- Pietikäinen, S. (2003). Indigenous identity in print: Representations of the sami in news discourse. Discourse & Society, 14(5), 581–609. https://doi.org/10.1177/09579265030145003

- Pietikäinen, S. (2008). Sami in the media: Questions of language vitality and cultural hybridisation. Journal of Multicultural Discourses, 3(1), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447140802153519

- Puijk, R. (2000). A global media event? Coverage of the 1994 lillehammer olympic games. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 35(3), 309–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/101269000035003005

- Rex, J. (1970). Race relations in sociological theory. Cox & Wyman.

- Rowe, D., & Boyle, R. (2021). Sport, journalism, social reproduction and change. In Wenner L. (Ed.), Oxford handbook of sport and society. Oxford University Press.

- Sant, S. L., Carey, K. M., & Mason, D. S. (2016). Media framing and the representation of marginalised groups: case studies from two major sporting events. In R. Schinke, K. McGannon & B. Smith (Eds.): Community based research in sport, exercise and health science (pp. 112–132). Routledge.

- Seippel, Ø., Broch, T. B., Kristiansen, E., Skille, E., Wilhelmsen, T., Strandbu, Å., & Thorjussen, I. M. (2016). Political framing of sports: The mediated politicisation of Oslo’s interest in bidding for the 2022 Winter Olympics. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 8(3), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2016.1182047

- Skille, E. Å. (2021). Doing research into Indigenous issues being non-Indigenous. Qualitative Research, 22(6), 831–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941211005947

- Skille, E. Å. (2022). Indigenous sport and nation-building. Interrogating sámi sport and beyond. Routledge.

- Skille, E. Å., Lehtonen, K., & Fahlén, J. (2023). The Politics of organizing Indigenous sport – cross-border and cross-sectoral complexity. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(2), 526–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2021.1892161

- Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. St. Martin’s Press.

- Snow, D. A., Rochford, E. B., Jr., Worden, S. K., & Benford, R. D. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. American Sociological Review, 51(4), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095581

- Stenling, C., & Sam, M. (2017). Tensions and contradictions in sport’s quest for legitimacy as a political actor: The politics of Swedish public sport policy hearings. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 9(4), 691–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2017.1348382

- Stenling, C., & Sam, M. (2019). From ‘passive custodian’to ‘active advocate’: Tracing the emergence and sport-internal transformative effects of sport policy advocacy. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 11(3), 447–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2019.1581648

- Stewart-Withers, R., Hapeta, J., Rynne, S., & Giles, A. (2024). Tino Rangatiratanga-Indigenous (MĀORI) Sovereignty and the messy realities of reconciliation efforts at the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup. Event Management. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599524X17135753220174

- Stuff. (n.d). Stuff.co.nz.

- van Dijk, T. A. (1997). Discourse studies: A multidisciplinary introduction.

- Walters, T., & Jepson, A. S. (2019). Understanding the nexus of marginalisation and events. In T. Walters & A. S. Jepson (Eds.), Marginalisation and events (pp. 1–16). Routledge.

- Walters, T., & Ruwhiu, D. (2021). Navigating by the stars: a critical analysis of Indigenous events as constellations of decolonization. Annals of Leisure Research, 24(1), 132–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2019.1643749

- Wenner, L. A., & Billings, A. C. (Eds.). (2017). Sport, media and mega-events. Routledge.

- World Lacrosse. (n.d.). Haudenosaunee nation. https://worldlacrosse.sport/world-lacrosse-members/haudenosaunee-nation/