ABSTRACT

Throughout the sixteenth century, the Ottoman Empire presented the most formidable challenge to the House of Habsburg’s predominance in Europe. This imperial rivalry and the military conflict which it generated made it vital that the Holy Roman Emperor and his advisors were kept informed about their powerful adversary to receive advance warning of impending attacks. For this reason, intelligence formed an important aspect of the day-to-day activities of the Aulic War Council, created in 1556 to coordinate the military defence of the Habsburg–Ottoman border, as well as the Austrian-Habsburgs’ resident ambassadors in Istanbul. Sources surviving in the Viennese archives provide valuable insights into the collection and dissemination of relevant information, as well as the organisation built by the Habsburg diplomatic presence in the Ottoman capital. In particular, this article examines ambassadorial expenditure accounts which provide insights into the financial aspects of Austrian-Habsburg intelligence in the period 1580–1583 and demonstrates that the business of intelligence was pursued by the Habsburgs in a more professional and orderly manner than historians usually acknowledge. Indeed, it was woven into the very fabric of the Aulic War Council as well as the Austrian-Habsburg diplomatic presence in Istanbul.

Introduction

The confrontation between ‘Christendom’ and the ‘Turk’ in the early modern period is often regarded as one of the central inimical dichotomies to have shaped the emergence of Western modernity. Iconic victories by ‘Christian’ forces over the ‘Muslims’ such as those won during the naval battle of Lepanto in 1571 or the defeat of the ‘Turkish’ besiegers of Vienna in 1683 continue to occupy a central place in anti-Muslim discourses in the twenty-first century, sadly invoked to legitimise terrorist actions such as the shootings at two mosques in New Zealand’s capital Christchurch on 15 March 2019.Footnote1 The ‘clash-of-civilisations’ narrative remains powerful, even though historical research in recent decades has done much to debunk the myths on which it is built, highlighting mutual interest and fascination as well as long phases of relatively peaceful coexistence between the Ottoman Empire and its neighbours in Europe.Footnote2

Yet even though the rhetoric of irreconcilable ideological enmity was created and maintained to serve the interests of specific historical actors, there is no denying that the Ottoman Empire’s territorial expansion brought the sultans into direct conflict with other European rulers – most importantly the House of Habsburg which, by the early sixteenth century, had risen to become the most powerful family in Europe. With Charles V ruling over an empire which united Spain and its possessions in Italy as well as overseas (r. 1516–1556) with the Austrian hereditary lands and, crucially, the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation (r. 1519–1556), the Habsburgs and Ottomans faced each other at sea in the Mediterranean as well as on land in Southeastern and Central Europe. And although the abdication of Charles V in 1556 divided the dynasty into an Austrian branch (which ruled over much of Central Europe) and a Spanish branch (which retained control over Spain and its colonies as well as South Italy), dynastic and imperial rivalries with the House of Osman continued unabated. In light of Charles Tilly’s classical model of state-building, it is no surprise, therefore, that these conflicts significantly shaped the two dynasties’ states.Footnote3

While the relevance of war with the Ottoman Empire as a key to the creation and transformation of state institutions in the Habsburg lands in the sixteenth century is well known, historians have tended to focus on either the military aspects of such measures as the creation of the Aulic War Council as a body of military coordination or the sphere of diplomatic relations sustained by resident ambassadors in Istanbul as well as the regular sending of gifts in accordance with the peace treaties with the Porte first concluded in 1547.Footnote4 Investments in intelligence, in contrast, have received little scholarly attention so that in comparison to the amount of research undertaken on intelligence organisations and operations in Italy, especially Venice, and the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs, historians thus far know little about how the Holy Roman Emperors and their advisers obtained information about the ‘international’ developments (an anachronistic but useful phrase) of their day.Footnote5

This gap in scholarship is rather surprising since contemporaries themselves were well aware of the need for good intelligence. At the height of the so-called Long Turkish War (1593–1601), the commander of the Habsburg troops in Hungary, Archduke Matthias (later Emperor, r. 1612–1619), was instructed ‘to quickly make provisions for obtaining information and news from the enemy’s territories so that it is possible to be apprised of his affairs on a daily basis. To achieve this, it is necessary to spare neither efforts nor costs.’Footnote6 And while the state of open war certainly lent great urgency to this interest in information, relations between the two empires were such that the gathering of intelligence was no less important in times of nominal peace. In fact, the general tendency of colleagues working on later centuries to regard early modern intelligence as haphazard and essentially dependent on the individuals entrusted with it is – notable exceptions such as Venice aside – in no small way the result of a relative dearth of written sources on this subject, because they were never produced due to a reliance on oral communication (as was the case in the Ottoman Empire), subsequently lost or even deliberately destroyed, or are scattered across a large number of collections and different archives.Footnote7 Although for the Austrian-Habsburg lands there is no intelligence archive comparable to that of Venice, there is an extensive paper trail which affords valuable insights into how the Austrian Habsburgs based in Vienna sought to obtain information about the ‘Turks’ in the second half of the sixteenth century.

Following this paper trail, I argue that intelligence was integral to the missions and day-to-day workings of both the Aulic War Council and the Imperial embassy in Istanbul. Rather than focusing on operations, my primary aim here is to reconstruct the organisational and institutional framework, paying particular attention to the ambassadors’ intelligence activities in the Ottoman capital which is possible thanks to the fortuitous survival of ambassadorial expenditure accounts from the early 1580s. Far from being amateurish, Austrian-Habsburg intelligence efforts directed at the Ottoman ‘hereditary enemy’ (Erbfeind) exhibit a remarkable degree of regularity and professionalism.

The Aulic War Council as an intelligence organisation

As briefly noted above, the formalisation and regularisation of Austrian-Habsburg foreign intelligence owed much to the Ottoman Empire’s challenge to the Habsburg dominance of Europe. In fact, Ottoman expansion during the reign of Sultan Süleyman I (r. 1520–1566) coincided with the apogee of Habsburg power in the person of Charles V. The Ottomans’ defeat of the kingdom of Hungary in the battle of Mohács severely reduced the once extensive kingdom and its role as a buffer between the Ottomans and the Habsburg hereditary lands. Moreover, the succession of Ferdinand of Habsburg (the later Emperor Ferdinand I, r. 1556–1564) to the Hungarian and Bohemian thrones (r. 1526–1564) following the death in battle of his brother-in-law King Louis II (r. 1516–1526) meant that Ottoman forces became an even more direct threat to Habsburg-ruled Central Europe.Footnote8 Even in times of official peace, such as the twenty-five years from the conclusion of the Treaty of Edirne in 1568 to the outbreak of the Long Turkish War in 1593, the border regions in Hungary and the Balkans remained subject to constant skirmishes and raids by actors on both sides.Footnote9 The resulting need to organise an effective defence against Ottoman incursions provided the stimulus for the creation of the Aulic War Council (Hofkriegsrat) in 1556 as the central institution of military coordination.Footnote10

The War Councillors were specifically entrusted with undertaking intelligence work. Their instructions enjoined them ‘to be always mindful of sparing nothing to obtain good intelligence (Kundschaft) and apply themselves diligently and faithfully to this task, as it is right and proper.’Footnote11 Moreover, they were ‘to each keep good correspondence with the representatives of their respective regions [and] to communicate incoming news of danger as well as other [relevant] matters … but at the same time limit the circulation of this information and keep it restricted’.Footnote12 Similar instructions were given to the members of the subordinate Inner Austrian Aulic War Council set up in 1578 to further improve the coordination of the defences in Croatia and Slavonia.Footnote13

That these were more than empty ideals is clear from the protocols of the Aulic War Council. Registering all incoming as well as outgoing correspondence with short summaries of their contents, the protocols provide ample evidence of the dissemination of intelligence. On 10 October 1575 for example, the Council received a letter from Gabriel Serieni, the commander of a fortification near Lake Balaton, which provided advance warning that the Ottomans were planning to cross the river Rába to attack Körmend (German: Kerment), a town about 130 kilometres south of Vienna. The information was acknowledged and forwarded to the commander of Győr (German: Raab) who was ordered ‘to keep careful watch’.Footnote14 In another instance from July that same year, Simon Forgách (d. 1598), another Hungarian captain, was instructed to ‘keep good correspondence with [Hans] Rueber’, the commander-in-chief in Hungary, because of acute dangers posed by the activities of Ottoman soldiers across the border.Footnote15 Similar instances of information-sharing abound in these registers.

Moreover, the Aulic War Councillors sent out requests for information on specific developments. In July 1575 Christoph Ungnad, the commander of Eger in Hungary (German: Erlau), was given instructions to ‘gather good intelligence on what the Turks are planning to do’.Footnote16 And in the aftermath of the dual election of Emperor Maximilian II and the voivode of Transylvania Stephen Báthory to the throne of Poland-Lithuania in December 1575, the War Council issued orders to Hans Rueber on 12 January 1576 ’that he make very diligent efforts to learn about the voivode of Transylvania’s [recent] embassy to the [Ottoman governor] of Buda’.Footnote17 Rueber complied on 18 January, sending a detailed report of the information given to him by ‘one of my men’ whom he had sent to Buda as an emissary and ‘who was with the pasha when the voivode’s envoy arrived there.’ Such missions were part and parcel of what Robyn Radway has called ‘vernacular diplomacy’ between officials and officers on both sides of the border and they also provided welcome opportunities to gather information about developments across the border.Footnote18 According to Rueber’s report, the Transylvanian voivode had requested military support from the governor of Buda to enable him to secure his claim to the Polish throne by military means. Because of a previous conflict between the two men, the governor of Buda remained non-committal, announcing privately to his advisers that he intended to conquer Transylvania while Báthory was away in Poland.Footnote19 While this was good news for the Habsburgs’ interests in Poland, the Ottoman conquest of Transylvania was undesirable to Maximilian II who, as king of Hungary, claimed suzerainty over the principality which had historically been part of the Hungarian kingdom.Footnote20

It is important to note that Rueber’s report has not been preserved in the files of the Aulic War Council at the Kriegsarchiv (War Archive), many of which were discarded or inserted into other collections mostly in the nineteenth century. Instead, it is now found among the records concerning Habsburg-ruled Hungary kept at the Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv (Archive of the House, Court, and State). This situation complicates attempts to reconstruct intelligence flows as well as operational details from archival collections whose documents were separated from the original contexts of their creation and consumption.Footnote21

That the Aulic War Council considered intelligence important in its day-to-day business not only in times of open war is evident from the fact that it reprimanded even high-ranking officers when they were deemed to be negligent in this respect. One such warning was issued to Herbard VIII von Auersperg (1526–1575), the captain of Carniola and himself a member of the Aulic War Council, in June 1575 for ‘not making sufficient efforts to obtain intelligence about the Turks’ activities’ and accusing him of ‘standing [idly] by as the Turks reconstruct the old fortresses’ in violation of the terms of the Treaty of Edirne. Auersperg, in fact, died in a skirmish with Ottoman border forces later that same year.Footnote22

All these examples highlight the importance of Habsburg military personnel for collecting information about the activities and preparations of the Ottomans and their vassals such as Báthory just across the borders in Hungary and Croatia. This fact, of course, reflects the military priorities arising from the need to organise the defence against frequent Ottoman incursions in a state of constant petty warfare. As a result, local officers were provided with an intelligence budget. Even if the relevant financial accounts have not survived in Vienna, the issue of money for these purposes – denoted by the German word Kundschaftergeld (literally money for scouts, informants, and spies) – surfaces frequently enough in the protocols to confirm the conclusion that intelligence-gathering, as an important element of the day-to-day activities of military officers and Aulic War Councillors alike, was a key activity of the organisation created to keep the Ottomans at bay.Footnote23

Obtaining information from Istanbul

The geographic reach of the intelligence networks organised by the border defence, however, was relatively limited. They had little insight into high-level decision-making at the sultan’s court, even if we should be careful not to overestimate the authority which the imperial centre exercised over its representatives in the border regions.Footnote24 In time-honoured tradition, such strategic information was sought out by the Holy Roman Emperor’s ambassadors in Istanbul.Footnote25

Between 1546 and the outbreak of the Long Turkish War in 1593, the Austrian Habsburgs maintained a nearly uninterrupted diplomatic presence in Istanbul.Footnote26 In terms of intelligence, much of the Austrian-Habsburg ambassadors’ activities unsurprisingly centred on trying to predict the likelihood of a renewal of warfare against the Habsburg lands, complementing the information-gathering undertaken along the Habsburg–Ottoman border. To this end, the diplomats needed to pay close attention to developments in other parts of the Empire, notably the war with Iran which lasted from 1578 until 1591.Footnote27 When it seemed likely in early 1581 that a truce would be concluded, Ambassadors Joachim von Sinzendorff (1544–1594, in Istanbul 1578–1581) and Friedrich Preiner (d. 1583, in Istanbul 1581–1583) warned of the likelihood that the Ottomans would renew the fighting in the west. They advised that ‘it is necessary to prepare the defences for this eventuality, especially since the men of war here are particularly desirous to wage war in Hungary.’Footnote28 According to the diplomats’ sources, the sultan had already delayed preparations for that year’s campaign in the east because of rumours that Emperor Rudolf II had died and resumed them only once this information had been confirmed to be false, presumably because he and his viziers had hoped to take advantage of a possible leadership crisis among the Habsburgs.Footnote29

It is difficult to escape the conclusion that this assessment was borne out a decade later, when peace between the Ottomans and Iran was finally concluded. In the same year, 1591, the Ottoman governor of Bosnia Hasan Pasha Predojević – officially on his own initiative but very likely with the backing of supporters at the Ottoman court – besieged the Habsburg fortress of Sisak and, in 1592, conquered Bihać (German: Wihitsch), both in Croatia. When Hasan Pasha was killed while undertaking another attempt to take Sisak in June 1593, the Ottoman Empire officially declared war and launched a full-scale military campaign into Hungary.Footnote30

As important as first-hand observations and attention to local gossip were – constituting the core of early modern open-source intelligence – the reports sent to Vienna in many cases were the result of active efforts to procure reliable information from the inner circles of decision-making which were normally closed to foreign diplomats. To this end, the Habsburg ambassadors headed an extensive network of spies (a term which I will here use for individuals rendering sustained services) and informants (who provided information more casually).

Contacts like these were crucial, for instance, in Friedrich von Kreckwitz’s assessment of Hasan Pasha’s military activities. Honours such as the sultan’s gift of a ceremonial robe and sword to the governor who liked to style himself as a gazi, a fighter engaged in extending the dominions under Muslim rule (dar al-islam), certainly nurtured the suspicion that the Sublime Porte’s official disavowal of Hasan’s attacks on Habsburg territory were insincere.Footnote31 Yet they were ambiguous evidence on their own until Kreckwitz was told by his sources that the siege of Bihać of 1592 had secretly received the blessing of the grand vizier Kanijeli Siyavuş Pasha (d. 1602) on the advice of İbrahim Bey (born Pál Márkházy, d. 1595), who was a key figure in Ottoman intelligence on Transylvania and the Austrian-Habsburg possessions in Central and South Eastern Europe. The action was designed as a locally contained operation to take advantage of momentary weaknesses in the Habsburg defences, while deliberately seeking to avoid escalation into ‘a complete breach of the peace’. In other words, the affair appears to have been a controlled provocation by the Ottoman government.Footnote32

Information about the identities of those who provided the ambassadors with such intelligence is scarce. Kreckwitz himself describes his source in the episode above merely as ‘one of my … new correspondents’ without any further clues to his identity other than the use of the male pronoun.Footnote33 Such circumspection was common and certainly meant to provide a measure of security to protect agents in case the ambassadors’ reports were intercepted and decrypted or Ottoman spies in Vienna and Prague somehow managed to gain access to the information contained in them. Spies and informants were not even assigned code names which would allow tracing certain types of information to a single source, further obfuscating the extent of the network and the value of individual participants for contemporaries and historians alike. As Matthias Pohlig points out in his contribution to this issue, such secrecy may also have served to bolster the reputation of the diplomat in question as an effective intelligence-gatherer even in cases when he might have depended on a very limited number of sources. It was all the more important, therefore, that Kreckwitz’s warning of the dispatch of an Ottoman spy to the Habsburg lands in 1592 – two weeks after the conquest of Bihać, in fact – emphasised that he had received this information by a ‘trustworthy report from secret places’.Footnote34 Such phrases indicating the diplomats’ evaluation of the reliability of the information in question as well as its source are common alongside the even more cryptic references to ‘secret persons’ and ‘secret servants’.Footnote35

We can glean more about the network of agents working for Kreckwitz’s predecessor David Ungnad (1538–1600, resident ambassador 1573–1578) from the diary of the chaplain Stephan Gerlach (1546–1612). His account provides invaluable insights into operational details. Of particular interest is his record of a particular misfortune in April 1576, when the Ottomans intercepted a bundle of Ungnad’s letters written in cipher.Footnote36 To the extent that this episode has been discussed by historians, the apparent inability of the Ottoman translators tasked with their decryption has usually been regarded as proof of a lack of cryptological expertise among Ottoman bureaucrats.Footnote37 In this particular case, however, this assessment misses the point that the key person entrusted with breaking the Habsburg ciphers was on the Habsburg payroll and therefore did everything in his power to protect the true content of these letters. This included not only withholding information and supplying bogus translations to the grand vizier, but also convincing others involved in trying to break the cipher to abandon the task.Footnote38

The agent in question was Adam Neuser (d. 1576), a former Protestant theologian from Heidelberg whose rejection of the Christian doctrine of the Trinity had led him to seek refuge in the Ottoman Empire in 1573 where he converted to Islam and took on work as an interpreter. Deeply torn by this move, his hope of obtaining a pardon from the Holy Roman Emperor which would allow him to return to his former home and family made him a key asset in Ungnad’s intelligence network in Istanbul.Footnote39 In the spring of 1575, for example, he furnished the ambassador with valuable information which helped thwart an alleged Ottoman spy mission directed at Spain, then ruled by Maximilian II’s cousin Philip II (r. 1556–1598). The spy in question, a Transylvanian convert to Islam known as Markus Penckner (fl. 1569–1583), himself later worked as a spy for Ungnad and his successors and became important for keeping taps on the Transylvanian embassy in Istanbul.Footnote40

The intelligence organisation in Istanbul reflected in expenditure accounts

Extremely valuable evidence about the intelligence organisation in Istanbul coordinated by the Austrian-Habsburg ambassadors comes from an almost unbroken series of ten expenditure accounts covering the period from 8 March 1580 until 19 August 1583, beginning with the final months of Joachim von Sinzendorff’s tenure as resident ambassador and ending with the death of his successor Friedrich Preiner.Footnote41 The importance of these accounts for both the study of Austrian-Habsburg intelligence and the financial history of the embassy cannot be overstated. They detail every expense incurred in Istanbul on official business, ranging from the salaries of locals employed by the embassy such as the janissary guards and interpreters to gifts given to Ottoman officials at various levels. Although the form of these documents indicates that financial reporting to Vienna was common practice, only a limited number of such records have survived from the sixteenth century.Footnote42

On the most basic level, these records provide an insight into the financial dimension of the ambassadors’ intelligence activities. They detail expenditure totalling 26,877.20 Taler in 418 separate entries. As shows, overall expenditure on intelligence and related activities amounts to 5,178.21 Taler, that is 19.3% of overall expenditure. While this figure is by no means an accurate measure for reasons which I will explain shortly, it is at least a reasonable indicator of the scale of the ambassadors’ intelligence spending in the Ottoman capital in the late sixteenth century.

Table 1. Overview of expenditure by the Austrian-Habsburg ambassadors in Istanbul, March 1580–August 1583.

My calculation of intelligence expenditure includes payments to irregular couriers whom the ambassadors employed for the extraordinary – and often clandestine – conveyance of messages to Vienna and key outposts along the Habsburg–Ottoman border. At 1,049 Taler (3.9% of overall expenditure), this means of disseminating information from Vienna was financially almost on a par with the regular courier service (1,197.50 Taler).Footnote43 Unlike these extraordinary messengers, however, the latter incurred additional expenses in the form of rewards and gifts given to Ottoman officials and soldiers who guided the couriers from the Ottoman–Habsburg border to the capital in addition to payments to the couriers themselves.Footnote44

While sending irregular couriers sometimes meant dispatching ‘one of my own men’, as Joachim von Sinzendorff did in June 1581, often enough the ambassadors entrusted their letters to lower-ranking Ottoman officials who were anyway travelling to the Ottoman Empire’s western borders on other business.Footnote45 Other messengers included ransomed captives on their way home, a French ‘renegade’, and a number of individuals who organised a postal route via Dubrovnik (Ragusa).Footnote46 Such irregular couriers not only complemented the official courier service to enable a greater frequency of messages, they played a vital role in diversifying channels for the exchange of sensitive messages, even if they did not always remain undetected by the Ottomans, as the interception of David Ungnad’s letters in April 1576 mentioned above indicates. In spite of this risk, similar means of dispatching letters from Istanbul were deemed sufficiently beneficial to continue the practice in the 1580s.

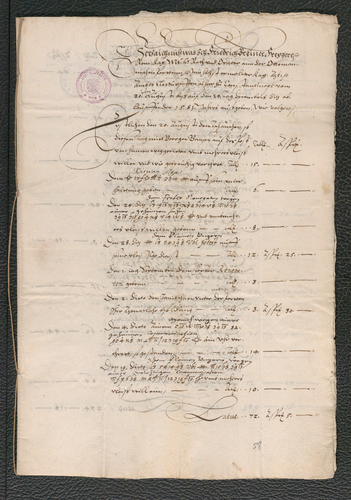

The largest share of intelligence expenditure (4,129.21 Taler, 15.4%) went to spies and informants.Footnote47 Frequently, the ambassadors handed out rewards for the delivery of information, as Preiner did on 4 September 1581 when he gave a clock worth 14 Taler to ‘a monk because of a secret communication’.Footnote48 Similarly, a man called ‘the tall Hungarian’ was given 20 Taler in return for ‘an important communication in Polish matters’ on 29 September.Footnote49 Tellingly, the identities of the recipients as well as the reasons for the expense, as vague as both of them are, were recorded into the accounts in cipher, whereas the date and the amount (and in the monk’s case the gifted object, too) all appear in plaintext (). Such practices of selective enciphering reflect not only an attempt to make effective use of the limited resources of secretarial staff trained in the ambassador’s cipher, but also tell us something about what information was deemed in need of special protection. The salaries paid to the janissary guards which are part of the ambassadors’ general expenses, in contrast, always appear in plaintext because they would have been regarded as standard practice by the Ottomans, had they intercepted these financial accounts.Footnote50

Figure 1. A page from Friedrich Preiner’s expenditure account for the period 20 August–24 December 1581. The seventh amount from the top represents the value of a clock given to a monk in return for providing information. Vienna, Austrian State Archive, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv, Staatenabteilungen, Türkei I, box 45, bundle for 1581 Dec. and n.d., fol. 58 r.

Not all payments to people who provided information were one-off gifts. In fact, a number of individuals received regular stipends, which points to a sustained relationship with the Imperial embassy. While some of the entries specify the reason for such payments – for instance the salary of the interpreter Ali Bey (Melchior von Tierberg, fl. 1570–1583) – many others do not.Footnote51 This may indicate either that the reason for their employment was well-known in Vienna and therefore did not require repetition in the accounts or it was omitted to obscure the nature of their services. While this in itself is not enough to conclude that all such unexplained stipends were connected to intelligence, a rare note by Kreckwitz concerning the recruitment of a new spy and the assignment of a yearly pension to him in 1592 at least strongly suggests that the remuneration of longer-term agents was recorded this way.Footnote52 My estimate of intelligence expenditure therefore includes the pensions paid to individuals who provided information at least once but whose functions are not otherwise identified such as the quarterly stipend given to the ‘small Hungarian’ (to distinguish him from the ‘tall Hungarian’) who received gifts on 19 September 1581 and other occasions as rewards for ‘important communication[s]’.Footnote53 In total, this man alone was paid 277.46 Taler in stipends and gifts (5.4% of intelligence expenditure) over the period covered by these registers, making him the fourth best-paid Habsburg agent identifiable in the accounts.Footnote54 When it is clear from either the entries in the registers or the ambassadors’ dispatches that salaries were paid for functions not directly connected to intelligence, these have not been included in the estimate here, even if individuals like Ali Bey occasionally received rewards ‘for several secret communications to me’.Footnote55

Although quantitative data almost magically assumes an aura of authority and exactness, it must be stressed that the figures presented here are neither complete nor beyond contestation, as the nature of the entries in Sinzendorff and Preiner’s expenditure registers often leaves room for interpretation and thus places limits on the calculation of exact figures. It is reasonable to suspect, for example, that the customary gifts ‘to the servants of the French ambassador and the Venetian bailo for the transmission of letters as well as many other familiar persons – Christians, renegades [i.e. converts to Islam], Jews – who are daily used and maintained in his Majesty’s service’ include individuals connected to the ambassadors’ intelligence operations. Yet because of the summary nature of these entries, it is impossible to ascertain this fact let alone determine which share should be included in the estimate, even though the use of ciphers in this context is strongly suggestive.Footnote56 In spite of these caveats, the estimate presented here is nevertheless at least a reasonable indicator of the scale of the ambassadors’ spending connected to the intelligence activities which they undertook in the Ottoman capital in the late sixteenth century.

That this scale is even more significant than the absolute monetary value becomes clear when we compare the proportions of the different categories of expenditure. As shows, the costs of embassy staff alone accounted for 32% of overall expenditure. More importantly, the ratio between expenditure directly connected to diplomatic representation and intelligence expenditure is roughly 2 to 1. Given the often substantial value of gifts in cash and kind given to key officials and valuable intermediaries, it is significant that intelligence nonetheless represents such a weighty share of expenditure.Footnote57

Of course, the amounts of money spent provide no insight into how much of their time and energy the Austrian-Habsburg ambassadors expended on cultivating relationships with actual and potential sources or on processing whatever information they received before bringing it to Vienna’s attention. The accounts, however, supplement the impression gained from dispatches that intelligence work was an important part of the ambassadors’ daily business. Although expenditure on intelligence represents only 19.1% of money spent, the corresponding entries account for a disproportionate 38.5% of entries across all ten registers, while at 23.2% the proportion of entries recording diplomatic expenditure is considerably lower than its financial share (). If we focus on the six registers which deal with day-to-day expenses to exclude those that detail annual payments to interpreters and gifts to the sultan as well as Ottoman officials, the share fluctuates between 34.2% in the period August 1582–March 1583 and a staggering 51.2% in August–December 1581.Footnote58 At 45.7%, the share of intelligence-related entries is similarly high in the accounts for November 1580–July 1581, indicating a particular high in intelligence expenditure at precisely the time when Sinzendorff and Preiner warned of the possibility of an imminent Ottoman campaign in Hungary in expectation of peace between Ottomans and Safavids, even if the entries in the accounts themselves do not make such a link explicit.Footnote59 On the whole, the space devoted to intelligence payments in the expenditure registers reinforces the conclusion that, for the Imperial ambassadors in Istanbul, intelligence work was much more than a job on the side. Instead, it was a core part of their duties.

Table 2. Proportions of expenditure categories by numbers of entries in the accounts of the Austrian-Habsburg ambassadors in Istanbul for March 1580–August 1583.

Networks of agents and intelligence targets

The expenditure accounts of Joachim von Sinzendorff and Friedrich Preiner are an extremely valuable source because they also contain information about the network of spies and informants who worked for the ambassadors as well as the areas they targeted. Whereas the dispatches focus on the information obtained and remain reticent about the identities of its sources, the registers provide actual names or otherwise sufficient detail about geographical locations and positions within Ottoman society to identify a total of 35 informants and spies, even if assigning individuals to either category is not always straightforward. The Imperial ambassadors clearly laboured to recruit agents in a cross-section of the upper echelons of the Ottoman imperial elite, as illustrated in which presents a selection of 27 intelligence sources by either their attachments to the households of Ottoman grandees or their membership in particular branches of Ottoman service, namely the interpreters and the çavuş corps (a mixture of bodyguards and official messengers). The latter two groups not only had privileged access to information and especially written documents such as official correspondence, they also acted as envoys to foreign courts and played a role in Ottoman intelligence. These men therefore were particularly valuable assets.Footnote60

Figure 2. Overview of 27 intelligence sources working for the Austrian-Habsburg embassy in Istanbul in the period March 1580–August 1583 whose affiliation to Ottoman dignitaries, membership in the çavuş corps, or work as interpreters is known. The style and colour of the edges symbolise membership in Ottoman grandee households, contacts among sources (where they are known), and the nature of payments received from the embassy according to the expenditure accounts of Joachim von Sinzendorff and Friedrich Preiner. Numbers in italics specify the total value of the gifts and payments received by the sources for intelligence-related services over the period covered by the accounts.

The dignitaries identified in were key players in Ottoman politics at the time. Lala Mustafa Pasha (d. 1580) had been the tutor of Sultan Selim II (r. 1566–1574) and served as grand vizier for a few months until his death in 1580.Footnote61 Kanijeli Siyavuş Pasha became grand vizier for the first time in 1582, serving until 1584, and assumed this office twice more from 1586–1589 and 1592–1593.Footnote62 Koca Sinan Pasha (d. 1596), finally, was grand vizier a total of five times (1580–1582, 1589–1591, 1593–1595, 1595, and 1595–1596) and, as military commander, played a key role in the Ottoman conquest of Tunis in 1574, the Ottoman–Iranian war of 1578–1591, and the Long Turkish War.Footnote63 The informants in his retinue, in fact, had been hired independently of each other to report to Sinzendorff from the campaign against Iran in 1580.Footnote64 Although Uluç Ali Pasha (born Giovanni Dionigi Galeni, d. 1587) never became grand vizier, he was admiral of the Ottoman fleet since 1571 and a member of the Ottoman imperial council.Footnote65 Ferhad Agha (later pasha, d. 1595) was the lowest-ranking official in this list of intelligence targets. Yet as the commander of the janissaries, the Ottoman Empire’s feared standing infantry, placing a source close to him was entirely consistent with the aim to receive early warning of military preparations. Moreover, Ferhad soon rose to higher dignities, becoming Koca Sinan Pasha’s chief rival for the grand vizierate in the 1590s.Footnote66 The recruitment of sources in his household is thus indicative of the Imperial ambassadors’ grasp of court politics.

Interestingly, the graph in includes only two of the top four agents on the Habsburg payroll: the interpreter Hürrem Bey (fl. 1575–1583; 352.78 Taler) and Ahmed Bey/Markus Penckner (586.50 Taler). The latter’s inclusion here among the interpreters is not based on the expenditure accounts, where no such function is mentioned, but on research in other sources.Footnote67 The remaining two spies – the ‘tall Hungarian’ and the ‘small Hungarian’ – are enigmas for the time being, although at least one of them might be identical to an agent recruited by David Ungnad with the help of Adam Neuser in 1576.Footnote68

The clustering of spies and informants in Uluç Ali Pasha’s household is particularly striking, as the number of agents here is by far the highest in any of the elite households. While the sum of 461 Taler (8.9% of intelligence expenditure) expended on these nine individuals is not particularly impressive (amounting to 51.22 Taler per person) when compared to the earnings of better paid agents such as Penckner (586.50 Taler) in the same period, the number of sources close to the admiral of the Ottoman fleet seems wildly disproportionate in light of the fact that the Austrian Habsburgs generally confronted the Ottomans on land.Footnote69 Nor can this attention be explained solely by Uluç Ali’s standing in the divan-i hümayun, the Ottoman imperial council.

Apart from an interest in ransoming captives, these expenses in all likelihood are evidence of ‘the Austrian contribution to the Spanish Habsburg secret service’ noted by Emrah Safa Gürkan. His research in the Spanish archives has turned up several instances of Austrian-Habsburg diplomats sending valuable information to Madrid.Footnote70 Such assistance was particularly useful because the Spanish Habsburgs did not have official diplomatic relations with the Ottomans and therefore lacked an embassy in Istanbul. While this did not prevent them from establishing intelligence organisations of their own in the Ottoman capital, as Gürkan’s work shows, the Austrian-Habsburg ambassador’s status and rank opened doors which remained closed to socially inferior and essentially secret agents.Footnote71

Although the expenditure registers contain at least two explicit references to Spanish concerns, both involving gifts of cash to Hürrem Bey, who had been instrumental in negotiating truces between Philip II and Sultan Murad III in 1575 as well as the early 1580s,Footnote72 more interesting, if less straightforward evidence of intelligence cooperation comes from the payments made to ‘one of Uluç Ali’s boys who has good knowledge of all of Uluç Ali’s secrets and provides me with good reports’. This individual made his first appearance in the registers on 4 December 1581.Footnote73 In May of the same year, Sinzendorff and Preiner reported that one of the admiral’s slaves ‘whom his master held in no small esteem’ had approached their embassy’s secretary Bartholomäus Pezzen (d. 1605) and offered ‘to provide written reports on all matters concerning the fleet’.Footnote74 The information which he divulged and which the diplomats reported to Vienna on 13 May 1581 was particularly detailed, concerning not only the movements of the fleet and its plans for the campaign season, but also Uluç Ali’s role in the Ottoman sultan’s policy towards the North African kingdom of Fez (in present-day Morocco). Sinzendorff and Preiner concluded that the man was particularly capable of living up to this promise ‘because he has such familiarity and confidentiality with a boy to whom Uluç Ali entrusts his greatest secrets and on whose services [the Spanish envoy Giovanni] Margliani relied while he was here’ in 1580. In fact, that ‘boy’ had been a key source for the latter. As the ambassadors explained, ‘by this means he had learned and known about everything that went on in Uluç Ali’s household’.Footnote75 This youth, therefore, was evidently ‘inherited’ from the Spanish networks to ensure continuity in intelligence flows, even if his direct recruitment occurred only later that year. And although the slave who had been taken on in May 1581 did not appear under that designation in the accounts, there is little doubt that he is the ‘secret person who keeps correspondence from Uluç Ali’s household’ given 30 Taler on 21 May.Footnote76

Finally, the report from May 1581 is remarkable because it openly acknowledges the key role played by the embassy’s secretary Pezzen – who was himself appointed ambassador in 1590 – in the above-mentioned slave’s recruitment as a source. John-Paul Ghobrial has demonstrated how much William Trumbull (1639–1716), the English ambassador in Istanbul from 1687–1691, relied on the written intelligence which he received from his secretary Thomas Coke (fl. 1667–1692) to the extent that his letters to London contain passages copied verbatim from the secretary’s briefings.Footnote77 It is reasonable to assume that secretaries had a similarly pivotal role in the Austrian-Habsburg embassy, perhaps even as the actual coordinators of the intelligence networks in Istanbul. This is particularly likely in Pezzen’s case because he had served the embassy since 1577 and remained in Istanbul with few interruptions until he was relieved as ambassador by Kreckwitz in 1591.Footnote78 In general, we require more scholarship on individuals in such middling positions in order to better understand how the intelligence organisations run by embassies were coordinated and maintained.Footnote79

Conclusion

In response to the military threat of the expanding Ottoman Empire especially after Ferdinand’s accession to the Hungarian throne in 1526, the Austrian Habsburgs gradually created new institutions and mechanisms to deal with an adversary too strong to be quickly defeated. This involved attempts to ward off hostilities by shoring up military capabilities as well as measures to find a mode of coexistence by maintaining diplomatic relations. The mid-sixteenth century was in many ways a crucial moment of Habsburg state-building in this respect with the establishment of a permanent embassy in Istanbul in 1546 and the creation of the Aulic War Council a decade later. Although the ostensible primary function of both was diplomatic and military, respectively, the documentation surviving in the archives in Vienna shows that the collection, analysis, and dissemination of intelligence formed an important part of the activities of Imperial ambassadors and their embassy staff as well as the Aulic War Councillors and the military officers subordinate to them. In fact, as demonstrated above, the instructions issued to the Aulic War Councillors upon their appointment expressly assigned them duties which we today recognise as intelligence work. That these were taken seriously is evident from the protocols of the Aulic War Council, even if many of the reports it received as well as the letters and instructions it sent no longer exist.

The documentary situation is somewhat better in the case of the intelligence activities of Austrian-Habsburg diplomats in Istanbul, even if the need to protect sources from detection by the Ottomans as well as individual ambassadors’ attempts to appear better informed than they perhaps were present obstacles to a fuller understanding of how exactly certain pieces of information were obtained. Nonetheless, we are fortunate that the existence of occasional expenditure accounts can be used to supplement opaque ambassadorial dispatches to reconstruct the networks of informants and spies organised by the ambassadors at least partially. The rare series of unbroken documentation of this kind for the period 1580–1583 examined here reveals efforts to strategically recruit sources in the households of major political actors as well as key areas of the Ottoman administration, notably the corps of messengers (çavuşlar, singular çavuş) and interpreters.

Moreover, the accounts provide a measure of the relative importance of intelligence vis-à-vis the ambassadors’ more narrowly diplomatic responsibilities. While the share of roughly a fifth of overall ambassadorial expenditure in this three and a half-year period and the fact that the costs directly associated with diplomatic representation were roughly twice as high seem to indicate that intelligence was an inferior element of the diplomats’ work, the proportion of entries in the accounts covering matters of intelligence reveal that ambassadors dealt with spies, informants, and irregular couriers more frequently than with Ottoman dignitaries or engaged in direct and indirect diplomatic negotiations. It is also important to emphasise that the estimates on which these calculations are based are in many ways conservative. The exclusion of ambiguous and imprecise declarations of expenses in the accounts means that actual spending has been underestimated rather than overestimated. Moreover, the estimates presented here leave aside the cost of maintaining the embassy, even though the latter provided the infrastructure which made intelligence operations possible in the first place. As the comparison with Emrah Safa Gürkan’s research into Spanish-Habsburg intelligence in Istanbul shows, the Austrian Habsburgs’ permanent diplomatic presence provided a structural advantage which is not easily quantifiable.Footnote80

In short, therefore, intelligence was structurally a key function of the work of the Austrian-Habsburg ambassadors. Far from mere narrations of details of diplomatic negotiations and transmission of ‘raw’ intelligence, they provided veritable intelligence briefings complete with assessments of the merits of the information reported and at times even concrete policy advice. On the whole, therefore, Austrian-Habsburg intelligence on the Ottoman Empire in the later sixteenth century was relatively regularised, fairly well organised, and professional, even if it admittedly falls short of the standards of professionalism and efficiency set even at the time by the Venetian intelligence organisation, let alone those which we have come to expect from modern bureaucratic intelligence services.Footnote81

How well Austrian-Habsburg intelligence performed in comparison to its direct competitors on the Ottoman side and how relevant its products were to political and military decision-making are questions for further research. Diplomats like David Ungnad and Joachim von Sinzendorff at least claimed awareness of Ottoman intelligence efforts and the consequent need to undertake counter-intelligence measures. Having just returned from Istanbul in September 1581, Joachim von Sinzendorff provided an alarming assessment of Ottoman intelligence capabilities:

They … have the most exact knowledge of the most secret of Your Imperial Majesty’s deliberations with Your most loyal counsellors … .Footnote82

Repeated lockdowns of the Imperial embassy by the Ottomans to reduce the ambassadors’ contacts with the outside world,Footnote83 the interception of Ungnad’s correspondence in 1576, a search of the embassy building by Ottoman officials following the defection of the ambassador’s majordomo in 1593, and the angry protestations of Grand Vezir Koca Sinan Pasha when that search revealed the extent of Friedrich von Kreckwitz’s reporting to Vienna indicate, in turn, that the Ottomans understood Austrian-Habsburg intelligence activities as a threat.Footnote84

This threat was not so much a threat to the security of the Ottoman Empire as such as primarily a threat to the success of its offensive designs in Central Europe. For, as the examples of operations discussed in this article make clear, Austrian-Habsburg intelligence on the Ottoman Empire was overwhelmingly defensive in the face of an enemy who, for most of the sixteenth century, was superior in terms of military organisation and the ability to mobilise resources for warfare. This fact also explains why intelligence remained crucial in times of official peace between the two empires since the Habsburgs stood to sustain painful losses, if and when the Ottomans resumed the offensive. If Charles Tilly’s dictum that war made the state applies to the Austrian-Habsburg lands insofar as war and the threat of war with the Ottomans led to the creation of new institutions to coordinate defences as well as the maintenance of a permanent diplomatic presence in the Ottoman capital, the reverse that the state made war does not. Instead, this particular state’s primary aim at the time was to avoid military conflict if possible and to limit it when it was not. The Holy Roman Emperors and their advisers realised only too well that intelligence – as both a force multiplier and a ‘mother of prevention’ – was the vital tool for survival in the face of the ‘Turkish menace’.Footnote85 They consequently wove intelligence into the very fabric of the diplomatic presence in Istanbul as well as the institutions charged with coordinating military operations against the Ottomans.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tobias P. Graf

Tobias P. Graf is an Assistant Professor of Early Modern European History at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin in Germany. He studied history at the University of Cambridge before receiving his doctorate from Heidelberg University, Germany, in 2014. He has held teaching and research positions at the universities of Heidelberg, Tübingen, and Oxford. Tobias's research focuses on geographical, social, and religious mobility especially between the Ottoman Empire and Europe, as well as the history of intelligence and information-gathering in the early modern period. He is the author of The Sultan's Renegades: Christian-European Converts and the Making of the Ottoman Elite, 1575–1610 (Oxford University Press, 2017).

Notes

1. Stefan Hanß, Lepanto als Ereignis: Dezentrierende Geschichte(n) der Seeschlacht von Lepanto (1571) (Göttingen: V&R unipress, 2017), 17–42; Almut Höfert, Den Feind beschreiben: ‘Türkengefahr’ und europäisches Wissen über das Osmanische Reich 1450–1600 (Frankfurt: Campus, 2003); Aslı Çırakman, From the ‘Terror of the World’ to the ‘Sick Man of Europe’: European Images of Ottoman Empire and Society from the Sixteenth Century to the Nineteenth (New York: Lang, 2002); Jon Gambrell, ‘Rifles Used in New Zealand Mosque Shooting Bore White Supremacist References’, USA Today, 15 March 2019, https://eu.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2019/03/15/new-zealand-shootings-guns-used-bore-white-supremacist-references/3172793002/ (accessed 21 February 2022); and Berthold Seewald, ‘Vom Amselfeld zum belagerten Wien nach Christchurch’, Die Welt, 16 March 2019, https://www.welt.de/print/die_welt/politik/article190389397/Vom-Amselfeld-zum-belagerten-Wien-nach-Christchurch.html (accessed 21 February 2022).

2. Molly Greene, A Shared World: Christians and Muslims in the Early Modern Mediterranean (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000) and Suraiya N. Faroqhi, The Ottoman Empire and the World around it (London: I. B. Tauris, 2006) are now classical expositions of this revisionist approach.

3. Charles Tilly, Coercion, Capital, and European States, AD 990–1992, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1992); Emrah Safa Gürkan, ‘Espionage in the 16th Century Mediterranean: Secret Diplomacy, Mediterranean Go-Betweens and the Ottoman Habsburg Rivalry’ (unpublished doctoral diss., Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., 2012); Emrah Safa Gürkan, Sultanın Casusları: 16. Yüzyılda İstihbarat, Sabotaj ve Rüşvet Ağları (Istanbul: Kronik, 2017).

4. Winfried Schulze, Landesdefension und Staatsbildung: Studien zum Kriegswesen des innerösterreichischen Territorialstaates (1564–1619) (Vienna: Böhlau, 1973); Michael Hochedlinger, ‘Das stehende Heer’, in Hof und Dynastie, Kaiser und Reich, Zentralverwaltungen, Kriegswesen und landesfürstliches Finanzwesen, vol. 1 of Verwaltungsgeschichte der Habsburgermonarchie in der Frühen Neuzeit, ed. Michael Hochedlinger, Petr Maťa and Thomas Winkelbauer (Vienna: Böhlau, 2019), 655–763, esp. at p. 663. On the beginnings of diplomatic relations between the Austrian Habsburgs and the Ottomans, see Ralf C. Müller, ‘Der umworbene “Erbfeind”: Habsburgische Diplomatie an der Hohen Pforte vom Regierungsantritt Maximilians I. bis zum “Langen Türkenkrieg” – Ein Entwurf’, in Das Osmanische Reich und die Habsburgermonarchie: Akten des Internationalen Kongresses zum 150-jährigen Bestehen des Instituts für Österreichische Geschichtsforschung. Wien, 22.–25. September 2004, ed. Marlene Kurz, Martin Scheutz, Karl Vocelka and Thomas Winkelbauer (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2005), 251–79; Ernst Dieter Petritsch, ‘Tribut oder Ehrengeschenk? Ein Beitrag zu den habsburgisch-osmanischen Beziehungen in der zweiten Hälfte des 16. Jahrhunderts’, in Archiv und Forschung: Das Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv in seiner Bedeutung für die Geschichte Österreichs und Europas, ed. Elisabeth Springer and Leopold Kammerhofer (Vienna: Verlag für Geschichte und Politik; Munich: Oldenbourg, 1993), 49–58.

5. Ioanna Iordanou, Venice’s Secret Service: Organizing Intelligence in the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019); Ioanna Iordanou, ‘What News on the Rialto? The Trade of Information and Early Modern Venice’s Centralised Intelligence Organisation’, Intelligence and National Security 31 (2016): 305–26, as well as Iordanou’s contribution to this issue; Filippo de Vivo, Information and Communication in Venice: Rethinking Early Modern Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Paolo Preto, I servizi segreti di Venezia, 2nd ed. (Milan: il Saggiatore, 2004); Carlos Carnicer and Javier Marcos, Espías de Felipe II: Los servicios secretos del Imperio español (Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros, 2005); Emrah Safa Gürkan, ‘Espionage’. Key studies on Austrian-Habsburg intelligence unfortunately remain inaccessible to most general historians of Europe for reasons of language: Josip Žontar, Obveščevalne služba in diplomacija acstrijskih Habsburžanov v boju proti Turkom v 16. stoletju (Ljubljana: Slovenska akademija znanosti in umetnosti, 1973); Gábor Ágoston, ‘Információszerzés és kémkedés az Oszmán Birodalomban a 15–17. században’, in Információáramlás a Magyar és török végvári rendszerben, ed. Ivadar Petercsák and Mátyás Berecz (Eger: Dobó István Vármúzeum, 1999), 90–109.

6. Vienna, Austrian State Archive, Kriegsarchiv (hereafter KA), Innerösterreichischer Hofkriegsrat (hereafter IÖHKR), Croatica, Akten, box 8, file 1601/5/36, fol. 13 v. Compare KA, Alte Feldakten, box 37, file 1596/13, fol. 980 v.

7. For such rather bleak assessments of early modern intelligence, see, for example, David Kahn, ‘An Historical Theory of Intelligence’, in Intelligence Theory: Key Questions and Debates, ed. Peter Gill, Stephen Marrin and Mark Phythian (London: Routledge, 2009), 4–15; Phillip Knightley, The Second Oldest Profession: The Spy as Patriot, Bureaucrat, Fantasist and Whore (London: Pan Books, 1986), 3. Contrast, however, the recognition of the importance of early modern developments in Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (London: Penguin, 2018), 4 and the positive appraisal of military intelligence during the Thirty Years’ War by Derek Croxton, ‘“The Prosperity of Arms is Never Continual”: Military Intelligence, Surprise, and Diplomacy in 1640s Germany’, Journal of Military History 64 (2000): 981–1004.

8. Paula Sutter Fichtner, Terror and Toleration: The Habsburg Empire Confronts Islam, 1526–1850 (London. Reaktion, 2008), 28–33.

9. Gustav Bayerle (ed.), Ottoman Diplomacy in Hungary: Letters from the Pashas of Buda, 1590–1593 (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1972), 4–5; Peter F. Sugar, ‘The Ottoman “Professional Prisoner” on the Western Borders of the Empire in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries’, Études Balkanique 7 (1971): 82–91, at 82.

10. Hochedlinger, ‘Das stehende Heer’, 663–4; Oskar Regele, Der österreichische Hofkriegsrat 1556–1848 (Vienna: Verlag der österreichischen Staatsdruckerei, 1949), 13–16, 84.

11. KA, Hofkriegsrat (hereafter HKR), Sonderreihen, Kanzlei-Archiv, IX a, no. 3, fol. 15 v.

12. KA, HKR, Sonderreihen, Kanzlei-Archiv, IXa Nr. 3, fol. 15 r.

13. Schulze, Landesdefension, 106.

14. KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 160, fol. 174 v, no. 48; KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 161, fol. 181 r, no. 91, and fol. 164 v, no. 89.

15. KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 160, fol. 65 r, no. 117. On Forgách, see A Pallas nagy lexikona: Az oesszes ismeretek enciklopédiája, 18 vols. (Budapest: Pallas, 1893–1904), s.v. ‘Forgách’, no. 18 (‘F. Simon (III)’), online edition at http://mek.oszk.hu/00000/00060/html/037/pc003763.html (accessed 21 February 2022).

16. KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 161, fol. 49 v, no. 67 (6 July 1575).

17. KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 163, fol. 157 r, no. 93 (12 January 1576). On the general context of the Polish-Lithuanian elections, see Christoph Augustynowicz, Die Kandidaten und Interessen des Hauses Habsburg in Polen-Litauen während des Zweiten Interegnums 1574–1576 (Wien: WUV | Universitätsverlag, 2001).

18. Robyn Dora Radway, “‘Vernacular Diplomacy: The Culture of Sixteenth-Century Peace Keeping Strategies in the Ottoman–Habsburg Borderlands’, Archivum Ottomanicum 34 (2017): 193–204; Radway, ‘Vernacular Diplomacy in Central Europe: Statesmen and Soldiers between the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires, 1543–1593’ (doctoral diss., Princeton University, 2017), 117–218; Bayerle, Ottoman Diplomacy.

19. Vienna, Austrian State Archive, Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv (hereafter HHStA), Länderabteilungen, Ungarn, box 108, fols. 81 r–82 v (Hans Rueber to Emperor Maximilian II, Košice, 18 January 1576), quotation from fol. 81 r.

20. Teréz Oborni, ‘The Artful Diplomacy of István Báthory and the Survival of the Principality of Transylvania (1571)’, in Frieden und Konfliktmanagement in interkulturellen Räumen: Das Osmanische Reich und die Habsburgermonarchie in der Frühen Neuzeit, ed. Arno Strohmeyer and Norbert Spannenberg (Stuttgart: Steiner 2013), 85–93, at 86.

21. For the period under discussion, the records of the Aulic War Council generally need to be consulted together with the following collections at the Kriegsarchiv: Alte Feldakten and Innerösterreichischer Hofkriegsrat. And at the Haus-, Hof- und Staatsarchiv: Länderabteilungen (covering ‘domestic’ records, with separate subcollections for Austria and Hungary), Staatenabteilungen (with subcollections for individual countries, e.g. ‘Türkei’ for the Ottoman Empire), Kriegsakten, and Reichshofrat. For a brief archival history of the Aulic War Council files, see Michael Hochedlinger, ‘AT-OeStA/KA ZSt HKR Wiener Hofkriegsrat (HKR), 1557–1848 (Bestand)’, online catalogue of the Austrian State Archive, https://www.archivinformationssystem.at/detail.aspx?id=4727 (accessed 21 February 2022), under ‘Angaben zu Inhalt und Struktur,” row ‘Bewertung und Kassation’.

22. KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 161, fol. 4 r, no. 140 (18 June 1575). On Auersperg, see Gustav Adolf Mentnitz, ‘Auersperg. 5) Herbard VIII. Freiherr’, in Neue Deutsche Biographie, ed. Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 26 vols. (Berlin: Duncker und Humblot, 1953–2016), 1:437, http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/0001/bsb00016233/images/index.html?seite=455 (accessed 21 February 2022). On the terms of the Peace of Edirne, see Bayerle, Ottoman Diplomacy, 3–4.

23. See, for example, KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 160, fol. 138 r, no. 17; KA, HKR, Bücher (Protokolle), vol. 163, fol. 164 r, no. 234. Compare Andrej Hozjan, ‘Die ersten steirischen Kundschafter und Postbeförderer: Spionage, Kontraspionage und Feldpost der Grazer Behörden zwischen 1538 und 1606’, Mitteilungen des Steiermärkischen Landesarchivs 48 (1998): 237–79, whose research has focused on the Styrian archives in Graz where more material of this kind appears to have been kept.

24. Hozjan, ‘Kundschafter’, 257. On the limits of sultanic power, see H. Erdem Çıpa, The Making of Selim: Succession, Legitimacy, and Memory in the Early Modern Ottoman World (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2017); Baki Tezcan, The Second Ottoman Empire: Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Emrah Safa Gürkan, ‘The Centre and the Frontier: Ottoman Cooperation with the North African Corsairs in the Sixteenth Century’, Turkish Historical Review 1 (2010): 125–63.

25. Garrett Mattingly, Renaissance Diplomacy (London: Cape, 1955), 113–14, 244–5, 258–62; Michael Talbot, British–Ottoman Relations, 1661–1807: Commerce and Diplomatic Practice in Eighteenth-Century Istanbul (London: Boydell, 2017), 44–8; Isabella Lazzarini, Communication and Conflict: Italian Diplomacy in the Early Renaissance, 1350–1520 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 76–7; Lucien Bély, Espions et ambassadeurs au temps de Louis XIV (Paris: Fayard, 1990).

26. Bertold Spuler, ‘Die europäische Diplomatie in Konstantinopel bis zum Frieden von Belgrad (1739): 3. Teil: Listen der in Konstantinopel anwesenden Gesandten bis in die Mitte des 18. Jhdts.’, Jahrbücher für Kultur und Geschichte der Slaven 11 (1935), 313–66, at 322.

27. For a brief account of this conflict, see Finkel, Osman’s Dream, 169–73.

28. HHStA, Staatenabteilungen, Türkei I (hereafter StAbt, Türkei I), box 44, bundle for 1581 April, fol. 6 v.

29. HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 44, bundle for 1581 April, fol. 6 r–6 v.

30. Noel Malcolm, Agents of Empire: Knights, Corsairs, Jesuits and Spies in the Sixteenth-Century Mediterranean World (London: Lane, 2015), 393–8; Finkel, Osman’s Dream, 173; Tobias P. Graf, The Sultan’s Renegades: Christian-European Converts to Islam and the Making of the Ottoman Elite (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 137, 147–8.

31. HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 79, bundle for 1592 Nov.–Dec. and s.d., fols. 27 r–28 v.

32. HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 80, bundle for 1593 Mar.–Apr., fols. 110 r–111 r, quotation from fol. 111 r; Sándor Papp, ‘From a Transylvanian Principality to an Ottoman Sanjak: The Life of Pál Márkházi, a Hungarian Renegade’, Chronica 4 (2004), 57–67, at 67; Graf, Sultan’s Renegades, 147–8.

33. HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 80, bundle for 1593 Mar.–Apr., fol. 110 r.

34. KA, IÖHKR, Croatica, Akten, box 4, file 1592/10/119, fols. 74 v–75 r.

35. For example, HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 45, bundle for 1581 Sept., fol. 204 v; HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 58, bundle for 1586 Nov., fol. 130 v.

36. Stephan Gerlach, Stephan Gerlachs dess aeltern Tage-Buch (Frankfurt, 1674), 174–7.

37. Emrah Safa Gürkan, ‘Espionage’, 86–8; Gábor Ágoston, ‘Information, Ideology, and Limits of Imperial Policy: Ottoman Grand Strategy in the Context of Ottoman–Habsburg Rivalry’, in The Early Modern Ottomans: Remapping the Empire, ed. Virginia Aksan and Daniel Goffman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 75–103, at 84–5, esp. n. 17. Both authors as well as Andrew, Secret World, 128–9 cite other anecdotes of Ottoman shortcomings in cryptanalysis although these, too, perhaps warrant more scepticism in light of the sources from which they are drawn.

38. Gerlach, Tage-Buch, 175–7.

39. Martin Mulsow, ‘Fluchträume und Konversionsräume zwischen Heidelberg und Istanbul: Der Fall Adam Neuser’, in Kriminelle – Freidenker – Alchemisten, ed. Mulsow (Cologne: Böhlau, 2014), 33–60; Mulsow, ‘Adam Neusers Brief an Sultan Selim II. und seine geplante Rechtfertigungsschrift: Eine Rekonstruktion anhand neuer Manuskriptfunde’, in Religiöser Nonkonformismus und frühneuzeitliche Gelehrtenkultur, ed. Friedrich Vollhardt (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 2014), 294–318; Raoul Motika, ‘Adam Neuser: Ein Heidelberger Theologe im Osmanischen Reich’, in Frauen, Bilder und Gelehrte: Studien zu Gesellschaft und Künsten im Osmanischen Reich; Festschrift Hans Georg Majer, 2 vols., ed. Sabine Prätor and Christoph K. Neumann (Istanbul: Simurg, 2002), 2: 523–38; Ralf C. Müller, Franken im Osten: Art, Umfang, Struktur und Dynamik der Migration aus dem lateinischen Westen in das Osmanische Reich des 15./16. Jahrhunderts auf der Grundlage von Reiseberichten (Leipzig: Eudora, 2005), 218–29; Graf, Sultan’s Renegades, 149–51, 197–9.

40. Tobias P. Graf, ‘Stopping an Ottoman Spy in Late Sixteenth-Century Istanbul: David Ungnad, Markus Penckner, and Austrian-Habsburg Intelligence in the Ottoman Capital’, in Rethinking Europe: War and Peace in the German Lands, ed. Gerhild Scholz-Williams, Sigrun Haude, and Christian Schneider (Leiden: Brill, 2019), 173–93.

41. Tobias P. Graf (ed.), Der Preis der Diplomatie: Die Abrechnungen der kaiserlichen Gesandten an der Hohen Pforte, 1580–1583 (Heidelberg: Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg, 2016), https://doi.org/10.11588/heibooks.70.60. The individual account registers and their entries have been numbered in this edition and will therefore be cited in the form <document number>:<entry number>. The missing register concerns payments to Ottoman officials in 1582. Although the total amount is mentioned in Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 8:17 and on the basis of doc. 2 it is reasonable to expect that some of this money was used to pay informants and spies, the amount has been omitted from this calculation. An Excel workbook detailing the calculations underlying this article is available from https://doi.org/10.18452/23796.

42. In addition to the exceptions noted in Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, xiii, I have since been made aware of the survival of the following accounts: Ogier Ghiselin de Busbecq (HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 12, bundle 1, fols. 187–191); Paul von Eytzing from January 1587 (HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 59, bundle for 1587 January, fols. 149–154); Bartholomäus Pezzen (HHStA, StAbt, box 66, bundle for 1588 June, fols. 138–151). Unfortunately, at the time of writing I did not know about the existence of similar accounts in Vienna, Austrian State Archive, Finanz- und Hofkammerarchiv, Sammlungen und Selekte, Reichsakten, boxes 276–282, and in particular the expenditure account by Friedrich von Kreckwitz in box 276, fols. 402–406. I am grateful to James Tracy and the anonymous reviewer for drawing my attention to these documents.

43. Expenditure on regular couriers is detailed in Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 1:34, 1:41, 1:42, 1:80, 1:82, 1:86, 1:103, 1:104, 5:28, 5:46, 6:1, 6:26, 6:27, 6:40, 6:41, 7:15, 7:16, 7:32, 7:33, 7:66, 7:67, 9:56, 9:57, 9:76, 9:77, 10:15, 10:16, 10:21, 10:22. Spending on irregular couriers: 1:1, 1:2, 1:7, 1:13, 1:14, 1:18, 1:20, 1:21, 1:22, 1:24, 1:25, 1:31, 1:35, 1:46, 1:50, 1:57, 1:58, 1:66, 1:68, 1:75, 1:100, 5:6, 5:7, 5:13, 5:20, 5:24, 5:25, 5:42, 5:44, 6:2, 6:14, 6:18, 6:23, 6:34, 6:37, 6:38, 7:12, 7:17, 7:22, 7:26, 7:29, 7:36, 7:38, 7:42, 7:51, 7:53, 7:60, 9:8, 9:9, 9:11, 9:21, 9:22, 9:24, 9:51, 9:55, 9:60, 10:9, 10:17.

44. See for example ibid., 6:26–27.

45. For example, ibid., 1:31, 7:53; Gerlach, Tage-Buch, 174.

46. On captives as couriers, see Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 7:17; HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 31, bundle for 1575 March, fol. 3 v. The French ‘renegade’ is mentioned in Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 6:34 and the postal route via Dubrovnik in 1:46 and 9:60.

47. This figure is based on ibid., 1:3, 1:4, 1:6, 1:9, 1:11, 1:29, 1:30, 1:36, 1:37, 1:38, 1:39, 1:44, 1:47, 1:48, 1:51, 1:52, 1:56, 1:59, 1:60, 1:73, 1:74, 1:83, 1:84, 1:90, 1:98, 3:6, 4:2, 4:4, 4:8, 4:9, 4:11, 5:3, 5:4, 5:5, 5:15, 5:17, 5:21, 5:23, 5:27, 5:32, 5:34, 5:35, 5:36, 5:37, 6:3, 6:4, 6:5, 6:7, 6:8, 6:9, 6:10, 6:12, 6:19, 6:22, 6:25, 6:33, 6:35, 6:36, 7:3, 7:4, 7:6, 7:13, 7:23, 7:24, 7:28, 7:39, 7:41, 7:50, 7:55, 7:61, 8:2, 8:4, 8:9, 8:10, 8:12, 9:3, 9:7, 9:12, 9:13, 9:14, 9:20, 9:26, 9:27, 9:32, 9:42, 9:46, 9:48, 9:52, 9:67, 9:70, 9:71, 9:74, 10:1, 10:5, 10:6, 10:8, 10:10, 10:11, 10:13, 10:19, 10:26, 10:27.

48. Ibid., 6:7.

49. Ibid., 6:12. Other mentions of this man in 1:3, 1:51, 1:83, 7:13, 9:46, 10:11.

50. For instance, ibid., 1:69, 6:6, 9:59.

51. On Ali Bey’s employment as an interpreter, see ibid., 4:1, 6:21, 8:1, 9:6, 9:16, and 9:49. A payment to this man specifically for information is registered in 9:74. See also Nedim Zahirović, ‘Two Habsburg Sources of Information at the Sublime Porte on the Second Half of the Sixteenth Century’, in Power and Influence in South-Eastern Europe, 16th–19th Century, ed. Maria Baramova, Plamen Mitev, Ivan Parvev and Vania Racheva (Münster: Lit, 2013), 417–23; Müller, Franken im Osten, 263–4.

52. Graf, Sultan’s Renegades, 195–6.

53. Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 6:8. For similar payments, see 1:56 and 7:24.

54. Ibid., 1:39, 1:56, 1:74, 1:98, 5:27, 6:4, 6:8, 6:25, 7:4, 7:23, 7:24, 7:39, 7:50, 9:3, 9:20, 9:48, 9:67, 10:13, 10:19. Only half the amount specified in 5:27 has been included here since the entry specifies that the gift was shared with another individual.

55. Ibid., 9:74.

56. Quotation from Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 2:7. See also 9:44 and contrast the use of plaintext in 1:86 and 1:87.

57. For example, when Kanijeli Siyavuş Pasha was appointed grand vizir in December 1582, Preiner made him a cash gift of 1,500 Taler in addition to a gold clock and astrolabe. See ibid., 9:28–9.

58. The six registers are ibid., docs. 1, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10. Among these, the lowest number of intelligence-related entries is found in doc. 9, the highest in doc. 6.

59. Ibid., doc. 5.

60. Ágoston, ‘Information’, 85–7, 90–1; Josef Matuz ‘Die Pfortendolmetscher zur Herrschaftszeit Süleymāns des Prächtigen’, Südost-Forschungen, 34 (1975), 26–60, at 28–32; Gustav Bayerle, Pashas, Begs, and Effendis: A Historical Dictionary of Titles and Terms in the Ottoman Empire (Istanbul: Isis, 1997), 29–30, s.v. ‘çavuş’.

61. İsmail Hâmı Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı (Istanbul: Türkiye Yayinevi, 1971), 20–1; J.H. Kramers, ‘Muṣṭafā Pasha, Lala’, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed., 12 vols., ed. P. J. Bearman et al. (Leiden: Brill, 1960–2004) (hereafter EI2), 7: 720–1.

62. Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, 22–4; Jan Schmidt, ‘Siyāwush Pasha. 1. Kanizheli’, in EI2, 9: 697.

63. Christine Woodhead, ‘Sinān Pasha, Khodja: 2. The vizier and statesman (d. 1004/1596)’, in EI2, 9: 631–2; Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, 21–5.

64. Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 1:9.

65. İdris Bostan, ‘Kılıç Ali Paşa’, in Encyclopaedia of Islam, 3rd ed., ed. Kate Fleet et al. (Leiden: Brill, 2007–), http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_24856 (published 2014, accessed 21 February 2022); Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, 20–5; Sali Özbaran, ‘Ḳapudan Pasha’, in EI2, 4: 571–2; Lewis, ‘Dīwān- i Humāyūn’, in EI2, 2: 337–9, at 338.

66. Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 6:33; V.J. Parry, ‘Ferhād Pasha’, in EI2, 2: 880–1; Danişmend, Osmanlı Devlet Erkânı, 23–4.

67. Graf, Sultan’s Renegades, 135, 150; Graf, ‘Stopping an Ottoman Spy’, 175, 186–8.

68. See note 38 above.

69. Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 1:90, 4:8, 4:9, 5:34, 6:35, 6:36, 8:9, 8:10, 9:14, 9:26, 9:71, 10:5. For the payments to Penckner, see 1:6, 1:47, 1:59, 1:73, 5:27, 5:32, 5:35, 5:36, 6:10, 7:61, 8:4, 9:12, 9:13, 9:52, 10:1, 10:6, 10:10; for those to the ‘small Hungarian’, above n. 54. Only half of the amount in 5:27 is counted towards payments made to Penckner since he shared it with the ‘small Hungarian’.

70. Emrah Safa Gürkan, ‘Espionage’, 234–5; Graf, ‘Stopping an Ottoman Spy’, esp. 181–5. For an example of Ungnad’s ransoming activities, Gerlach, Tage-Buch, 70.

71. Emrah Safa Gürkan, ‘Espionage’, 264–344.

72. Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 10:8, 10:26.

73. Ibid., 6:35, also 6:36.

74. HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 44, bundle for 1581 May–June, fols. 15 r–15 v.

75. HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 44, bundle for 1581 May–June, fols. 15 r–16 v, quotations from fol. 15 v.

76. Graf, Preis der Diplomatie, 5:34.

77. Ghobrial, Whisper of Cities, 129–44.

78. Alfred Loebl, ‘Pezzen von Ulrichskirchen, Barthlmä Freiherr’, in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, ed. Historische Kommission bei der Königl. Akademie der Wissenschaften, 56 vols. (Leipzig: Duncker and Humblot, 1875–192), 53: 41–7, online edition at https://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd13916779X.html (accessed 21 February 2022); Spuler, ‘Europäische Diplomatie’, 328.

79. Florian Kühnel, ‘Zur Professionalisierung diplomatischer Verwaltung: Sekretäre und administrative Praktiken in der französischen Botschaft in Istanbul (17. und 18. Jahrhundert)’, Francia 46 (2019), 167–89; Florian Kühnel and Christine Vogel (eds.), Zwischen Domestik und Staatsdiener: Botschaftssekretäre in den frühneuzeitlichen Außenbeziehungen (Cologne: Böhlau, 2021).

80. See note 71 above.

81. Iordanou, Venice’s Secret Service; Iordanou, ‘What News on the Rialto?’ See also Iordanou’s contribution to this issue.

82. HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 45, bundle for 1581 Sept., fol. 31 r. See also Ágoston, ‘Information’, 91.

83. For example, HHStA, StAbt, Türkei I, box 45, bundle for 1581 Sept., fol. 199 r; box 58, bundle for 1586 Nov., fol. 124 r; Graf, ‘Ladislaus Mörth: Ein ungewönlicher Renegat im Osmanischen Reich des späten 16. Jahrhunderts?’, in: Das osmanische Europa: Methoden und Perspektiven der Frühneuzeitforschung zu Südosteuropa, ed. Andreas Helmedach, Markus Koller, Konrad Petrovszky and Stefan Rohdewald (Leipzig: Eudora, 2014), 309–40, at 316. Austrian-Habsburg diplomats were not the only ones subject to such lockdowns and house arrests. See Benjamin Arbel, Trading Nations: Jews and Venetians in the Early Modern Eastern Mediterranean (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 77, esp. n. 4; Emrah Safa Gürkan, ‘The Efficacy of Ottoman Counter-Intelligence in the 16th Century’, Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hugaricae 65 (2012), 1–38, at 19.

84. Graf, Sultan’s Renegades, 139–41, 145.

85. See Matthias Pohlig, Marlboroughs Geheimnis: Strukturen und Funktionen der Informationsgewinnung im Spanischen Erbfolgekrieg (Cologne: Böhlau, 2016), 340.