ABSTRACT

Research question: This study investigates the impact of a healthcare portal and employee attitude toward a healthcare program on sponsorship-based employee motivation to do physical exercises.

Research methods: Applying a case methodology, the sponsorship object was the Norwegian National Cross-Country Skiing Team, and the sponsor was Aker, a major international corporation involved in fishing, offshore construction and engineering. By means of mixed methods, qualitative data were collected from 10 employees and then, quantitative data from 544 employees were used to test the hypotheses.

Results and Findings: The findings show that the user-friendliness of the healthcare portal, and the attitude towards the health care program are significant predictors of employees’ sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises. These findings held when controlling for sex, education, income, portal usage, and physical activity level.

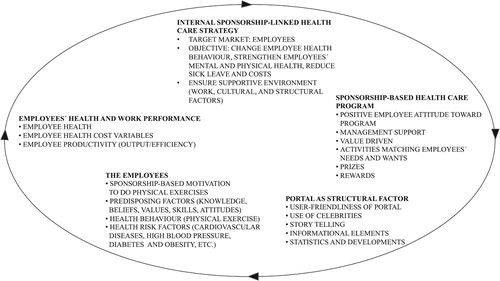

Implications: These findings have practical implications for sponsors and the use of sponsorships as a strategic tool to improve employee matters. ‘The Internal CSR and Sponsorship-linked Health Care Strategy Model’ is presented. This paper establishes connections between internal sponsorship activation, employee health care program, and their motivation to do physical exercise.

Introduction

Existing research on internal activation of sponsorships is related to several organizational outcomes like the promotion of a positive working environment (Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriou, Citation2004), employee pride (Pichot et al., Citation2008), enthusiasm in the workplace (Rosenberg & Woods, Citation1995), and the motivation and involvement of employees in the corporation’s actions (Hickman et al., Citation2005; Pichot et al., Citation2008). Besides, Pichot et al. (Citation2008) underlined that sports sponsorship can be considered as a vital factor in management strategy. Nevertheless, Dolphin (Citation2003) addressed the difficulties in measuring the effects of sponsorship programs targeted at employees. Consequently, the sponsorship domain was encouraged to be investigated further to increase knowledge about sponsorship activations (see e.g. Chavanat et al., Citation2009; Hanstad et al., Citation2013; Kim et al., Citation2015; Meenaghan, Citation2013). ‘The case for sponsorship suffers from the lack of a comprehensive, credible, and accessible body of evidence, which industry spokespersons can confidently and convincingly point to’ (Meenaghan, Citation2013, p. 390).

Recently, Cornwell and Kwon (Citation2019) completed a review of 409 sponsorship-linked marketing studies from the period between 1996 and 2017. A number of research questions related to sponsorship-linked marketing were proposed. One of the topics was about sponsor employees as an internal target audience for sponsorship. A chief reason to target employees (Cliffe & Motion, Citation2005) is that corporations use sponsorship as a strategy to gain competitive advantage in the market place (Amis et al., Citation1997; Amis et al., Citation1999; Fahy et al., Citation2004), which could be done through achieving internal effect objectives (Cunningham et al., Citation2009). An example of internal effect is that HR practices like socialization, and performance management may advance employee engagement, which in the end may lead to enforced competitive advantage (Albrecht et al., Citation2015). Thus, there are theoretical connections between sponsorship strategy, HR practices, and competitive advantage, which indicate that dimensions like employee health, physical activity, and HR-managed employee health care strategies are relevant to connect to internal sport sponsorship activation.

Concerning employee health standards, Kahn (Citation1990) argued that weakening of physical energy, as one of four employee disruptions, may impact employees’ psychological availability. Further, Brummelhuis and Bakker (Citation2012) documented that leisure actions (including physical activities) strengthen next morning employee energy through boosted psychological impartiality and relaxation. Caverley et al. (Citation2007) also found indications that efforts to reinforce workplace health may have a more instant effect on presenteeism than on absenteeism. More important, Proper et al. (Citation2006) documented that employees following suggestions of dynamic physical activity (by exercising at an energetic level at least three times a week) were absent from work due to sickness significantly fewer times than the others. Several studies have addressed the knowledge gap as to the effects of employee wellness programs and their potential to strengthen employee health and reduce costs (see e.g. Baicker et al., Citation2010; Berry et al., Citation2010; Goetzel et al., Citation2014).

To conclude, there is a lack of empirical research on internal activation programs in sport sponsorships and the impact on internal objectives, which are related to concrete employee matters (Dubois Gelb & Rangarajan, Citation2014; Maze & Alazani, Citation2017). Based on the theoretical reasoning above, in an internal sport sponsorship activation context, there are possible theoretical connections between employee health care programs and employee physical activity. Therefore, this study examines the influence a sport sponsorship-based health care program targeted at employees may have on employee motivation to do physical activity linked to the sponsorship. Here, we examine how Aker ASA, an international Norwegian corporation involved in fishing, engineering, and offshore construction, activated a sport sponsorship by implementing an employee health care program. Through the AkerActive program we gain insight into how sponsorship can be activated internally to increase employee motivation to do physical exercise.

Literature review

Employee health care program in a corporate social responsibility perspective

Sport sponsorship involves a strategic relationship between the sponsoring company and the sponsorship object for mutual benefit (Flöter et al., Citation2016; Hur et al., Citation2019). Corporate social responsibility on the other hand, is ‘a firm’s set of discretionary activities for the promotion of positive social changes beyond the immediate interests of the company or compliance with the law’ (Hur et al., Citation2019, p. 850). In the last decade, we have seen a growing interest in CSR as a part of sport sponsorship strategy (Plewa & Quester, Citation2011) enabling sponsors to demonstrate their values and build their brand image towards external stakeholders (Djaballah et al., Citation2017; Flöter et al., Citation2016; Hur et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, there is not much research on sport sponsorship in a CSR context (Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). Bason and Anagnostopoulos (Citation2015) examined how FTSE-100 firms used sport as a vehicle to produce CSR outcomes for various beneficiaries. They found that engagement in CSR activities provided indirect benefits in terms of lower staff turnover, absenteeism, improved talent recruitment and impression of own workplace. Still, there is little focus on internal CRS initiatives focusing on e.g. organizational practices in terms of employee health care, diversity and equal opportunities for all (Costas & Kärreman, Citation2013; El Akremi et al., 2015, Citation2018; Hur et al., Citation2019). The provision of workplace benefits as results of internal CSR activities beyond what is legally required, signals corporate commitment to the employee. Besides, such initiatives may be seen as part of a management control system, shaping employee behaviour, identity and meaning in organizations (Costas & Kärreman, Citation2013).

Further, both management and employees may benefit from internal CSR activities related to employee health care programs. Sickness absence represents a significant cost in many firms, which look for ways to reduce the extent and duration of absence related to health issues. Physical activity has been found to protect against multiple diseases and conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, high blood pressure, diabetes 2 and overweight (Pronk & Kottke, Citation2009). Further, moderate physical activity has been found to improve mental health and strengthen general well-being (Downward & Rasciute, Citation2011). Pronk and Kottke (Citation2009) summarized a great number of research articles and suggested how corporations should to get organized to support and to promote physical activity targeting employees. Therefore, when partners search to identify opportunities in a sport sponsorship strategy, one benefit may be that it helps the implementation of an employee health care program. The sport sponsorship objective can facilitate employee physical activity as an internal CSR strategy in exchange for financial support. To our knowledge, such a perspective in which the company takes responsibility for their employee’s well-being based on a sport sponsorship, is lacking in the literature.

Internal sponsorship activation and attitude toward health care program

Sport sponsorship is a practical device for some sponsors when trying to motivate and involve employees in their activities (Hickman et al., Citation2005; Pichot et al., Citation2008) and to make employees emotionally attached to both the sport in question and the sponsorship object (Mitchell, Citation2002; Pichot et al., Citation2008). As a part of internal marketing and as an act of implementing business strategies, internal sponsorship activation is becoming a more regular practice in integrated sport sponsorships (Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriou, Citation2004; Hickman et al., Citation2005; Pichot et al., Citation2008). Khan and Stanton (Citation2010, p. 192) defined ‘employee’s attitude towards their firm’s sponsorship’ as a central independent variable in their suggested conceptual model of corporate sponsorship effects on employees. They proposed that future research should focus on relations between sponsorship’s effects on employees, internal communication about the sponsorship and the internal marketing program. Internal marketing may be imperative for the work environment (Apostolopoulou & Papadimitriou, Citation2004), and as a means to involve employees in communicating values the sport represents (Pichot et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, sports sponsorship may create enthusiasm among employees (Rosenberg & Woods, Citation1995), and internal activation can create openings for developing emotional employee-sport attachments (Mitchell, Citation2002; Pichot et al., Citation2008).

However, present research indicates that internal value creation as an after-effect of sponsorship activation requires employees’ positive attitude towards the specific internal activation program. Khan et al. (Citation2013) presented a model about sports sponsorship for internal marketing purposes, which showed the relationship between employees’ attitudes towards employers’ sport sponsorship activity and employee behaviours advancing the organization. Thus, if an internal sponsorship activation program is a sponsor employee health care program, as in the case of this research, The four-stage change model of Lechner and Devries (Citation1995) of which the last stage is participating in fitness programs, measures health behaviour and uses attitude towards the program as a determinant. Haskell and Blair (Citation1980, p. 113) state that ‘people’s health attitudes and beliefs can influence their decisions to participate in an exercise program and to adhere to the program over time’. To summarize, theories from the literature indicate that employee attitude toward health care programs, as internal sport sponsorship activation, is a potent factor.

Effects of employee health care programs, and the role of corporate health portals

It seems that the implementation of worksite fitness and health promotion programs have increased over several decades (Gebhardt & Crump, Citation1990). From the health care management area, literature suggests that a number of company tools can be used to increase awareness of the role of physical activity and to develop a supportive environment for physical activity among employees (Amlani & Munir, Citation2014; Pronk & Kottke, Citation2009, p. 317). Golaszewski et al. (Citation2008) provided a conceptual model related to work site health promotion programs and the importance of a supportive environment (work factors, cultural factors, and structural factors). Supportive structural factors, like web-site/portal, were argued to have an effect on employees, which again should impact employee health. Some studies have investigated wellness programs as an instrument to cost reduction (Baicker et al., Citation2010; Berry et al., Citation2010). Goetzel et al. (Citation2014) argue that well-designed and well-executed programs may provide positive health and financial returns, contrasting Osilla et al. (Citation2012) questioning such a link. Odeen et al. (Citation2013) found a modest indication that workplace learning programs and physical exercise did not reduce sick leave. Besides, Tveito et al. (Citation2002) concluded that organizations trying to achieve a reduction in sick leave as a consequence of workplace interventions should reduce expectations. They recommended that new long-term investment and methods to improve employees’ health should be undertaken.

Nevertheless, according to Berry et al. (Citation2010) there are six success criteria for a prosperous employee wellness programs: (1) engaged leadership at multiple levels; (2) strategic alignment with the company’s identity and aspirations; (3) a design that is broad in scope and high in relevance and quality; (4) broad accessibility; (5) internal and external partnerships; (6) and effective communications. Brynjolfsson et al. (Citation2002) underlined that projects need cautious management consideration and document that an employee portal improved strategy communication. In addition, Uden et al. (Citation2007) advised that e-learning should support learning platforms, which mirror wider business objectives. Atreja et al. (Citation2008) identified three main predictors of satisfaction with web-based training: (1) instructional design effectiveness; (2) website usability: and (3) course usefulness. Benbya et al. (Citation2004) argued that if there is a seam between social, technical and managerial elements in a corporate portal, it is optimized. For instance, two of four technical factors are usability and effective information, and one of four managerial factors is rewards system.

Anderson et al. (Citation2009) developed a conceptual model consisting of worksite intervention components like informational messages (physical activity and healthy eating) to influence employee health knowledge and attitudes (body image and self-care). The objective was to improve the weight status of employees through changing employee behaviour (physical activity, food choices, and dietary intake) and physical activity. Crespo et al. (Citation2011) investigated onsite physical activity promotion strategies among adults working outside home. They concluded that numerous strategies promoting onsite physical activity at work may improve employees’ recreational physical activity. One strategy, is the use of sporting celebrities to mediate messages, which may result in a more positive attitudes towards the portal (Boyd & Shank, Citation2004). The sponsorship should be made visible and relevant for the environment and for the target group (Amis et al., Citation1999; Chavanat et al., Citation2009; Cornwell et al., Citation2005; Crimmins & Horn, Citation1996; Meenaghan, Citation1991; Thjømøe et al., Citation2002). In summary, the literature suggests that there are relations between a user-friendly portal with effective informational elements, as a structural factor, attitude toward the sponsorship-based health care program, and sponsorship-based health behaviour.

Method

To expand our understanding about internal activation, we applied a case study approach (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Yin, Citation2013) using the sponsorship of Aker ASA (see Aker Achievement AS, Citation2011/Citation2012; Aker ASA, Citation2012, Citation2013/Citation2014), a major Norwegian industrial investment company working within oil, gas, maritime – and marine biotechnology. Aker sponsored the Norwegian National Cross-Country Team, and the ski celebrities were instructed to play important roles in the sponsorship-based activation program dealing with health care. The program focused on employee physical activity aiming at reducing sick days.

Setting – the Aker ASA case

Aker is one of the largest industrial groups in Norway, with eight companies listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange, a total turnover of approximately NOK 42/EURO 4.2 billion in 2017, and a workforce of 19, 444 employees, including 9423 in Norway (Annual report, 2017). In June 2010, Aker ASA signed a 4-year sponsorship agreement with the Norwegian National Cross-Country Team. This agreement made Aker the general sponsor of the Norwegian Ski Federation – cross country (NSF), which, at that time, represented the biggest sponsorship deal ever for the national team. The agreement extended over a four-year period ensuring a funding of around Euro 1.6 million per season and ended after the 2013/2014 Winter Olympic season. A new business unit, Aker Achievements AS, was set up to promote and manage the agreement. Aker provided financial resources and business knowledge.

The elite skiers, their coaches and support staff, contributed with expertise in health areas like physical training, nutrition, motivation, performance culture, skiing technique and ski preparation. Three major activation tools were developed: (1) A digital web-based learning portal (akeraktiv.no); (2) a rolling PR-truck and related events; and (3) the Oslo Ski Show. Akeraktiv.no targeted employees only, while the two other strategic tools were about providing sports-related event experiences for regular people. However, the main goal of the internal activation program was to promote a healthier and more active lifestyle among employees and to trigger a behaviour change that ultimately could reduce the sick leave rate by .5%. In Norway (at that time), such a corporate strategy using a sport sponsorship and an internal sponsorship-based health care program to reduce sick leave was considered innovative.

Akeraktiv.noFootnote1 was an internal web-based portal where employees could access information (individual user-id and password required) about health-related areas such as physical training programs, nutrition, and skiing technique. The Aker employees could register as beginner, active or advanced, and they received targeted tutorials adjusted to their specific levels and needs. The users were encouraged to register all training minutes in the portal allowing for participation in competitions where prizes could be won. By having stored statistics about training sessions, the users could compare weekly performances with prior results both at an individual level and between business units. Akeraktiv.no was launched with the campaign ‘World Championship 2011’.Footnote2

Three main employee motivation strategies were implemented to increase the use of the portal and the physical activity level. First, the use of sports celebrities from the national team should encourage employees to use the portal. An example from the akeraktiv.no is a pitch by the sport celebrity Therese Johaug, addressing the Aker employees:

Together with the national cross-country skiing team I’m preparing for the World Championships in Oslo, and you can do it too! No matter if you are an advanced skier wanting to improve your training or if you just want to get started. Sign up for WC- track, this will be great fun for all of us.Footnote3

The internal sponsorship activation in terms of a health care program, aimed at increasing employee health standards and reducing the sick leave rate, was considered a success. Aker Achievements annual report Citation2011/Citation2012 (p. 4) stated: ‘In 2011, the sickness absence in Aker and Aker-owned companies fell from 5 to 4.5 percent. This gave the Aker companies in Norway an economic value creation of approximately NOK 50 million last year’.

Research design

The investigation was organized in a pre-study and a main study combining methods (Patton, Citation1990; Yauch & Steudel, Citation2003). Secondary data about the sponsorship program, descriptions about the internal activation activities, and claimed effects were extracted from the annual reports of Aker Achievements AS, Citation2011/Citation2012 and Aker ASA, Citation2012, Citation2013/Citation2014 and subject to analyses (Baxter & Jack, Citation2008). The applied document analysis is valuable as documents are stable, they cover a long period, and a wide range of events (Yin, Citation2013). We were also given access to the internal portal www.akeraktiv.no for a limited period of time. The analyses of the portal and the reports aided the researchers in gaining knowledge about the case and the respondents (Pitney & Parker, Citation2009). Furthermore, combining analyses of interviews with the initial document analysis strengthened the credibility and dependability dimensions (Golafshani, Citation2003; Morrow, Citation2005). First, we followed an exploratory sequential design (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). In the pre-study, we collected and analysed qualitative data, identified the variables and defined two hypotheses. In the main study, the hypotheses were tested using survey data. Details of the procedures, data collection, analyses, and findings are presented under the pre and main study.

Pre-study

The main objective of the pre-study interviews was to develop hypothesized relationships between the variables based on the literature review and the interviews. We started out by applying the logic of an inductive approach using the qualitative data to enrich the meanings of sentiments expressed by the respondents (Creswell et al., Citation2003; Thomas et al., Citation2015). The literature lacks scales related to the merger of theories on internal sponsorship activation, employee health care programs, and sponsorship-based motivations to do physical exercises. Searching for meanings of sentiments, an important aspect of the pre-study, was used to align topical interview questions with Aker’s internal sponsorship activation program, and the main objective at the corporate level. Aker wanted employees to think of physical activity and good physical health as being important for the sick leave rate.

Data collection and analysis

Based on the literature review, we developed a semi-structured interview guide. The guide was designed to capture individual sentiments of the sponsorship-based health care program (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017), and enable answering ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ – questions related to a concrete sponsorship activation case (Thomas et al., Citation2015). The guide contained questions related to the following focal topics: (1) employee physical activity; (2) attitude toward the sponsorship; (3) user-friendliness of the healthcare portal; and (4) sponsorship as motivator to do physical exercises. Before asking questions about the topics, we initiated the interviews by asking about job tasks, position, and time used at job desk.

Data were collected following Robinson (Citation2014), using a stratified selection, of which the criteria were to have a sample of mixed gender, age and two categories of Aker employees, non-users and users of the portal. A manager of the Aker HR department was our internal contact, and she helped us to recruit and organize interviews with employees from both categories. Over a three-week period, we interviewed 10 employees, 7 at their offices and three by phone. During the 9th and 10th interview, we identified repeat answers and decided that we had collected sufficient data material for the pre-study. Of the 10 respondents, 7 were users of the portal, and three were non – users. Each interview lasted between 40 and 60 min. The interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed to ensure reliability (Spiggle, Citation1994; Yin, Citation2013). To clarify possible uncertain issues, the in-depth interviews were followed-up by communication via e-mail in line with the approach used by Farrelly et al. (Citation2012). This two-stage process made it possible to disclose authentic and consistent impressions of statements and descriptions (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017; Shenton, Citation2004; Yin, Citation2013).

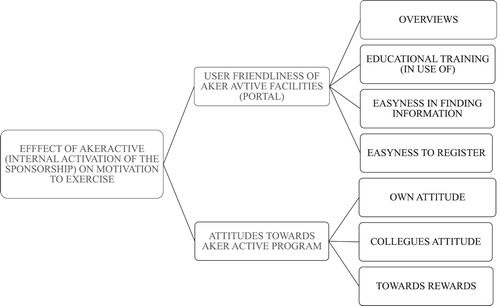

The coding of the data followed a thematic analysis, as described by Braun et al. (Citation2016). We began by reading the interviews and taking initial notes. The initial coding was based on the pre-conception of important themes identified in the theoretical framework. As the interpretation of the data emerged, we analysed patterns in the data, searching for sentiments, categories and themes to be further investigated (Charmaz, Citation2015; Creswell & Creswell, Citation2017). We searched for items possibly belonging to the theoretical coding family means-goal (end, purpose, goal, anticipated consequences) (Glazer & Strauss, Citation2017). In this study, such a sequence is primarily about sponsorship-based motivators for employee physical activity (Pinder, Citation2014), such as attitude toward the sponsorship activation program and the user-friendliness of the akeraktiv.no portal. The pre-study analysis resulted in codes consisting of main themes and sub-themes: the employee situation, motivation, attitude (stress, workplace, health, physical exercise/number of times and what, sponsorship, attitude toward sponsorship), and user-friendliness of the portal, contents, and the use. The findings are accompanied with descriptive narratives based on viewpoints from the 10 informants to support the analysis and findings (), which is in line with Barthes (Citation1997). Also, these narratives are incorporated to underscore that the findings are based on the collected data fulfilling the confirmation criterion (Shenton, Citation2004).

Table 1. Viewpoints from 10 interviewed employees.

Findings

All informants claimed that they work a substantial amount of time in front of their computers, and that daily sitting time was excessive. Several of them believed that it was important to be physically active. With the exception of one respondent, the interviewees were involved in physical activity two or more times a week. Out of the 10 interviewees, three did not use the portal. Typical explanations were ‘little time’ and ‘poor information’. One employee felt that akeraktiv.no was an ‘elite thing’.

Motivations for doing physical activities varied. A few of the interviewees expressed it by stating: ‘Weight control’. Another employee saw it differently: ‘Self-esteem’. Most of the interviewees agreed that physical activity gives a double-sided gain. Two of the informants stated: ‘You stay healthy, get more energy, and feel better’, and ‘the most important is to get extra energy and stay in good shape’.

The user frequency of the portal seemed to be about twice a week. The informants used it primarily to register type of activities and number of minutes. Otherwise, the portal was used to read news and blogs by the elite skiers, and some of the informants were also on the diet pages. The informants did not express any problems in reaching the minimum time requirement to be allowed to take part in the prize draw. The general impression was that employees were positive about the portal, its motivating role and user-friendliness. For some, the possibility of winning prizes related to the sponsorship program seemed to be an important motivational factor. Statements include

It’s a little fun to be able to win things, but it may be enough with an orange as a prize, and ‘people are not so interested in akeraktiv.no and the sponsorship if nothing comes out of it (prizes and other benefits).

Hypothesis development

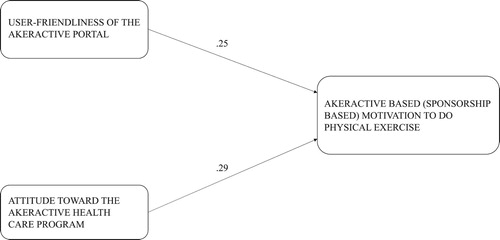

The reviewed literature and the key findings in terms of variables and sentiments from the qualitative data, which is summarized in , reveal that internal activation of sponsorship embodies a vehicle to involve and motivate employees (Hickman et al., Citation2005; Pichot et al., Citation2008). The findings suggest a considerable value is attached to the portal itself, with informational elements and user-friendliness supported by current research (Atreja et al., Citation2008; Benbya et al., Citation2004; Berry et al., Citation2010; Boyd & Shank, Citation2004; Uden et al., Citation2007), and the attitude toward the sponsorship-based health care program (see e.g. Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Haskell & Blair, Citation1980; Khan et al., Citation2013; Lechner & Devries, Citation1995). Therefore, we propose two hypotheses related to the sponsorship-based health portal and the health care program as influential variables on the dependent variable about sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises (see : The testable model):

H1: The user-friendliness of the sponsorship-based portal impacts sponsorship-based

motivation to do physical exercises.

H2: Attitude toward the sponsorship-based health care program impacts sponsorship-

based motivation to do physical exercises.

Main Study

Scale development

The findings from the pre-study were used as sources for developing scales applied in the main study to test the hypotheses. Thus, we applied a hybrid approach of an inductive and deductive process (Fereday & Muir-Cochrane, Citation2006). We argue below how we have developed the scales. Vallerand (Citation1997) prosed that motivation can be measured at e.g. domain level, like work, education, leisure, and reward and recognition systems may impact work motivation (Gagné & Forest, Citation2008). Likewise, we argue that rewards and support systems influence employee motivation to do physical activity. We consider the dependent variable in this study as a situational factor. Examples of situational factors measuring motivation at work are ‘because this job fits my personal values’ and, ‘I chose this job because it allows me to reach my life goals’, which may be explained by other factors (Gagné et al., Citation2010). Thus, in a similar fashion, it is legitimate to investigate how sponsorship-based employee motivation to do physical exercises, may be influenced by attitude toward the sponsorship-based health care program, and the AkerActive portal as independent variables. The respondents were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with statements on a seven-point Likert scale, where 1 indicated ‘strongly disagree’, 4 ‘neither agree nor disagree’ and 7 ‘strongly agree’. Additionally, respondents were asked about physical activity level, usage of the akeraktiv.no portal, and demographic variables like gender, age, civil status, education and household income. The questionnaire was pre-tested on six selected respondents encouraged to comment on any problematic issues. The wording of a few questions and items were corrected.

Data collection and respondent characteristics

According to the HR manager, about 5000 of total 13,000 employees working in Norway (24,000 worldwide) were registered users of the Aker Active portal. The invitation to participate in a web-based survey was distributed to these 5000 employees by the HR department via email. The survey was accessible for 10 days. After the deadline, the voluntarily response sample consisted of 544 employees, who provided usable questionnaires for the data analysis. The descriptive analysis of the data implies acceptable variation in the material (Hair et al., Citation2015). Of the 544 respondents who completed the questionnaire, 32.7% were women and 67.5% were men, 80.7% had a university degree, and 57.5% of the households earned more than euro 75,000 a year. Further, 70% of the employees regarded their job as deskbound and 38.2% used the portal two or more times a week. The sample of employees seemed to be physically active as 47.6% claimed to exercise 3–4 times a week, and 23% exercised 5 times or more. One explanation for the high numbers is the sampling method. First, only users of the Aker active portal were invited, and second, participation was voluntary. This sampling method is likely to have induced a skewness in respondents towards those more active, hence limiting the generalizability of the study and the representation of the population. The Aker Annual Report 2011 stated that 28% of the employees were women indicating similarity in terms of gender. Still, given this limitation, almost 43% of the respondents claimed that they had become more physically active after the introduction of akeraktiv.no. This means that more than four out of 10 already active employees responded positively to the sponsorship-based health care program. Fifty-four per cent of the respondents considered the portal neat and transparent, and about half of the respondents claimed to be motivated by the rewards and skiing team-related prizes.

Preliminary data analysis

To identify constructs and their item content, we performed an exploratory factor analysis, using Principal Component analysis extraction and Promax rotation (Osborne et al., Citation2008) to test the convergent validity of the multi-item scales. Items with factor loadings below .40 and items hampering unidimensional factor structures (double loadings) were removed to ensure convergent and discriminant validity, respectively (Hair et al., Citation2015; Osborne et al., Citation2008). The analysis obtained three factor structures, and the corresponding factor loadings are satisfactory. The reliability scores of the constructs were measured by Cronbach’s alpha. The Cronbach alpha score of 0.75 is above the .65 requirement and indicates reliability in the scales (Hair et al., Citation2015). Cronbach alpha, mean, and standard deviation scores for the constructs are reported in .

Table 2. Factor analysis and solution.

Furthermore, the inter-item correlations between factors should be between .3 and .8 with a Cronbach’s alpha below .9 according to Diamantopoulos et al. (Citation2012). The scores were .53 between factor 1 (user-friendly portal) and 2 (attitude toward program) as the independent variables, .50 between 1 and 3 (sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises as the dependent variable) and .48 between 2 and 3. The eigenvalues of the variables (factors 1, 2, and 3) and the factors’ explaining the variance in the data were 5.36/41.22%, 1.16/8.88%, and 1.53/11.43%, respectively.

Hypothesis tests

To test the hypotheses, we regressed ‘sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises’ against ‘user-friendliness of sponsorship-based health portal’, and ‘attitude toward sponsorship-based health care program’. shows that the means of the three variables are respectively 4.10, 4.53, and 5.11 on the 7-point scale. Further, the table summarizes the results of the regression model, which was controlled for possible influences of ‘number of times using the portal and doing physical exercises’, ‘education’, ‘income’, and ‘gender’. ‘Number of times using the portal and doing physical exercises’ were significant (p = .00, p = .04), but none of the demographic variables (p = .99, p = .97, p = .34). The results of the regression model (R2 = .38 and F = 41.31) showed that the two independent variables identified in this study have a positive and significant effect on ‘sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises’, with beta-values of .25 and .29 respectively, confirming the support for H1 and H2 (see ).

Table 3. Regression solution.

Discussion, theoretical and conceptual contributions

Kim et al. (Citation2015) note that existing literature on sponsorship effectiveness primarily covers sponsorship outcomes from a consumer perspective. Due to the lack of literature on internal activation of sport sponsorship (Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2019), we started this study by asking whether a sponsorship-based health care program can impact employees’ motivation for physical activity. The managerial assumption of Aker was that by motivating employees to do physical exercises, sickness absence and related costs would drop. We applied an internal CSR perspective focusing on a sponsor’s objective to improve employees’ physical activity through a health care program and a connected portal. The two hypotheses about the program and portal were supported. Our Aker case study shows that both the portal and attitude toward the program have a significant influence on sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises.

Our findings are in line with related studies such as the study of Conn et al. (Citation2009) about workplace physical activity, which concludes that certain workplace physical activity interventions can advance physical health. Parks and Steelman (Citation2008) found that participation in an organizational wellness program leads to lower levels of absenteeism and higher job satisfaction. Kuoppala et al. (Citation2008) indicate that activities like exercises and ergonomics are associated with employees’ well-being and reduced sickness absence. Rongen et al. (Citation2013) completed a review of literature published before June 2012, evaluating the effects of worksite health promotion programs looking at e.g. physical activity, healthy nutrition, and/or obesity on self-perceived health, and work absence due to sickness. They found that of 21 interventions, the overall effect of a health program was minor. However, the effects of the programs were larger in younger populations.

The main study reveals that an organizational structure factor like the healthcare portal, as well as an employee predisposing factor have significant impacts on health behaviour. This finding fits the theorizing of Golaszewski, Allen, et al. (Citation2008), who argue that the company health environment consists of work, structure, and cultural factors, which influence employee health behaviour. Structure factors comprise tangible features of the sponsorship activation program including services, policies, benefits, and associated internal communication and program promotion labelled as a part of a supportive environment. Specifically, our investigation documents that internal activation of a sponsorship has a positive and significant influence on motivation for physical exercise through the impact of portal (structural factor) and attitude towards the program (predisposing factor).

This study contributes to the sponsorship literature in three ways. First, several researchers have called for increased attention to the relationship between sponsorships and corporate strategy (Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2019). The sponsorship deal between Aker ASA and the Norwegian National Cross-Country Skiing Team demonstrates that a sponsor may link the internal activation to a corporate strategy. Our study uncovers the opportunities to link health care programs to internal sport sponsorship and internal CSR programs. In this case, the sponsorship was implemented as part of a strategy to reduce sickness absence and employee sick leave costs.

Second, there is a growing interest in CSR programs as a part of in-house caring (Hur et al., Citation2019). Aker management was willing to invest resources on developing and implementing a sponsorship-based health care program and technology supporting the akerakltiv.no portal. Employees perceived the health care program initiative positively and as a sign of thoughtfulness from the management, which is the essence of an internal CSR program. In an internal sponsorship activation and an internal CSR context, we realize that motivating employees to do physical exercise depends on their positive attitude towards the sponsorship-based health care program supported by celebrity athletes and a user-friendly portal. This may also mean that sponsors should avoid the trap of selecting the wrong sponsorship object and building technology that no one uses. The pre-study indicates that the sponsorship object should be inspiring and knowledgeable. The portal ought to promote training and nutrition programs, celebrity stories, statistics and developments, and the benefits and rewards for the employees participating in the program. Such detailed content of an internal sponsorship-based health care program and portal has not been suggested previously in sport sponsorship literature. Also, separate from the explanatory variables of interest, the results show that the controlling factors of number of times exercising per week and number of times using the portal, have a significant impact on the sponsorship-based motivation for physical exercise. The roles of these two variables indicate the importance of the portal content and user-friendliness.

Third, the positive attitude of the sponsorship-based health care program, and the user-friendliness of the health portal, including for example use of sport celebrities (Boyd & Shank, Citation2004), and the perceived ease of registration of exercises in minutes are likely to motivate employees to do physical exercise. Even though only a few of the interviewees from the pre-study claimed that they did more exercise now than before the portal launch, most of them stated that they actually used the portal. Considering also the results of the main study, which confirm the importance of the portal, the pre-study finding indicates that the prominence of the portal may also be about stimulating people to keep the activity level, as is. These findings are in line with theories across disciplines on attitude (Atreja et al., Citation2008; Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1980; Ajzen & Madden, Citation1986; Lechner & Devries, Citation1995), perceptions of portals in a learning context (Uden et al., Citation2007), and behavioural change (Berry et al., Citation2010; Haskell & Blair, Citation1980; Pichot et al., Citation2008). It seems that many of the 5000 users, registered exercised minutes on a regular basis. Thus, activities linked to physical exercise are integrated within day-to-day business to facilitate the sense of well-being as expressed by several informants. By implementing such an internal sponsorship-based CSR strategy, employees may learn that physical exercise will reduce sick leave and gradually contribute to the development of an organizational health culture (Golaszewski et al., Citation2008).

We merged theories from the sponsorship, occupational health and health science literature with findings in this study to suggest specific managerial steps as means to impact employee health through sponsorship activation. (see below), the Internal CSR and Sponsorship-linked Health Care Strategy Model, illustrates the merger and is a conceptual contribution. The three constructs identified in this study (positive employee attitude toward program, user-friendliness of portal, sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises) are combined with key elements from existing literature and the organizational health environment model conceptualized by Golaszewski et al. (Citation2008). The new idea is that sponsor employees are the target group of the sponsorship-linked health care strategy, who can participate in health care program activities facilitated by a portal to influence employees’ health and performance (Golaszewski et al., Citation2008).

Managerial implications

To advance the knowledge of a supportive environment, this study, based on the Aker case, is about the concrete supportive elements of a health care program in a sponsorship activation context. We may learn from the Aker case that managers should encourage and facilitate internal involvement by using tools like incentive systems, training programs, and targeted internal communication (Baumgarth & Schmidt, Citation2010). A health culture can be developed through an organizational health environment (Golaszewski et al., Citation2008). The objective of an internal CSR strategy could be communicated as a corporate objective, consisting of a variety of activities fitting employees’ needs and wants, and be supported by management (Berry et al. Citation2010). The organizational value ‘healthy’ may guide employee behaviour (De Chernatony et al., Citation2003; Mellor, Citation1999) and is also useful if it is associated with the same value as the sport of the sponsorship object (Pichot et al., Citation2008). Therefore, an internal sponsorship-linked health care program may be built around the ‘healthy’ value, which also may be a guiding principle towards developing an organizational health culture. These findings suggest that there is a latent potential in activating a sport sponsorship in terms of a health care program defined as an internal CSR strategy targeting employees. However, a supportive health environment facilitating the internal activation of a sport sponsorship similar to what is outlined in the Aker case needs to be described.

Conclusion, limitations and future direction

This investigation discloses the potential of implementing internal sponsorship-based strategies. Given the defined need for new knowledge about how sponsorships can be activated targeting employees (see e.g. Cornwell & Kwon, Citation2019; Khan & Stanton, Citation2010; Zinger & O'Reilly, Citation2010), this study contributes to improved understanding about sponsorship leveraging strategies as internal CSR strategies targeting employee health. The corporate goal of the internal sport sponsorship activation strategy of Aker ASA was to increase employee physical activity, employees’ health standards, and thereby reduce sick leave and related costs. The goal was to reduce the sick leave rate from 5 to 4.5 per cent from September 2010 to September 2011. The target was reached according to an annual report, providing Aker with an annual cost reduction of approximately NOK 50 million (about euro 5 million) (Aker Achievement AS, Citation2011/Citation2012, p. 12).

We argue that internal sport sponsorship activation strategies have a great potential to be leveraged as employee health care programs. First, such programs need sponsorship objects (here: sport celebrities) with a status and appeal triggering employees’ positive attitude. Second, the Aker case shows that a structural factor like a health portal is of great importance. The functioning of the portal is to promote important information and assist employees in registering exercised minutes, which enables them to win prizes and get other incentives. Thus, the sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises is likely to increase. The development of measurement scales and the sponsorship-related items of the main study are based on findings from the qualitative pre-study, which was based on 10 interviews. The setting was in a sport sponsorship activation context where attitude toward the sponsorship-based health care program, the health portal as a structural factor, and sponsorship-based motivation to do physical exercises were important issues. We aimed at capturing statements (items) related to known concepts from the reviewed literature and linked them to the Aker sponsorship-based health care program. Thus, we captured the contextual nuances of the constructs with suitable items (situational factors). We collected data from 544 employees of which 70.6% was physically active 3–4 times or more a week and 32% used the portal two times or more a week.

There are a few limitations to this study. First, there is a potential limitation that the sample does not represent the working population of Aker, and that the findings apply only to employees who opted for physical exercise. Additionally, as with all case studies, one must exercise caution in generalizing the findings to other populations and contexts (Yin, Citation2013).

Second, the annual report of Aker reports that sick leave dropped from 5 to 4.5%. This information is supportive of the sponsorship activation health care program. But we would understand the real effect more precisely if we collected two sets of data before and after the introduction and implementation of the AkerActive sponsorship-based health care program. In such a case we would have considered the program as a type of a natural intervention. Third, if we had the sick leave days for users and non-users of the AkerActive portal over a certain time period, and their physical activity level before the introduction of AkerActive health care program, we could have discovered the impact of the program on less physically active employees. Fourth, one could argue that a corporate health portal and an employee health care program, not linked to any sport sponsorship would have a similar impact on employee motivation to do physical exercises. A case design with at least two similar cases (one linked to a sport sponsorship object and one without) to compare across firms would be valuable. However, based on both the qualitative and the quantitative findings in this study, we have strong indications that sponsorship-based motivation linked to sport celebrities and pride is of importance to employees.

Future research could address the issues raised above and design studies on sport sponsorship to further improve our understanding of internal activation. Also, upcoming research could follow a similar approach to search for findings and possibly verifications in other cultures. Also, researchers could apply general, validated attitude and motivation scales related to a sponsorship-based health care program and test them against intention to do physical exercises (Citation1993; Lippke et al., Citation2004), which was not done in this study. Furthermore, Baxter et al. (Citation2015) presented a web-based calculator (Workplace Health Savings Calculator) to be used for employers to quote possible savings from reduced sick leave and staff turnover as a result of investments in and the administration of a workplace health promotion program. Future research could also aim at developing a Sponsorship-based Health Care Program Calculator. Such studies may also include examining workplace culture for supporting health, which could apply a validated measurement scale, as developed by Kwon et al. (Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 http://www.akeraktiv.no (www.akeractive.com, only accessible for employees).

2 FIS Nordic World Ski Championships Citation2011, Oslo.

3 posted at www.akeractive.no in 2010.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1980). Understanding attitudes and predicting social behaviour. Prentice-Hall.

- Ajzen, I., & Madden, T. J. (1986). Prediction of goal-directed behavior: Attitudes, intentions, and perceived behavioral control. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 22(5), 453–474.

- Aker Achievement AS. (2011/2012). Annual report. https://eng.akerasa.com/content/download/10149/127264/file/Annual_report_2011.pdf

- Aker ASA. (2012). Annual report. https://eng.akerasa.com/content/download/14167/160805/ … /Aker-2012-en-reduced.pdf

- Aker ASA. (2013/2014). Annual report. https://eng.akerasa.com/content/ … /Aker%20ASA%20Annual%20report%202013.pdf

- Albrecht, S. L., Bakker, A. B., Gruman, J. A., Macey, W. H., & Saks, A. M. (2015). Employee engagement, human resource management practices and competitive advantage. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 2, 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-08-2014-0042

- Amis, J., Pant, N., & Slack, T. (1997). Achieving a sustainable competitive advantage: A resource-based view of sport sponsorship. Journal of Sport Management, 11(1), 80–96. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.11.1.80

- Amis, J., Slack, T., & Berrett, T. (1999). Sport sponsorship as distinctive competence. European Journal of Marketing, 33(3/4), 250–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569910253044

- Amlani, N. M., & Munir, F. (2014). Does physical activity have an impact on sickness absence? A review. Sports Medicine, 44(7), 887–907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-014-0171-0

- Anderson, L. M., Quinn, T. A., Glanz, K., Ramirez, G., Kahwati, L. C., Johnson, D. B., Buchanan, L. R., Archer, W. R., Chattopadhyay, S., Kalra, G. P., & Katz, D. L. (2009). The effectiveness of worksite nutrition and physical activity interventions for controlling employee overweight and obesity: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(4), 340–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.003

- Apostolopoulou, A., & Papadimitriou, D. (2004). ‘Welcome home’: Motivations and objectives of the 2004 Grand National Olympic sponsors. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13(4), 180–192.

- Atreja, A., Mehta, N. B., Jain, A. K., Harris, C. M., Ishwaran, H., Avital, M., & Fishleder, A. J. (2008). Satisfaction with web-based training in an integrated healthcare delivery network: Do age, education, computer skills and attitudes matter? BMC Medical Education, 8(1), 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-8-48

- Baicker, K., Cutler, D., & Song, Z. (2010). Workplace wellness programs can generate savings. Health Affairs, 29(2), 304–311. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0626

- Barthes, R. (1997). Introduction to the structural analysis of narratives. In R. Barthes (Ed.), Image-music-text (Stephen Heath, Trans.) (pp. 79–124). Glasgow: Collins.

- Bason, T., & Anagnostopoulos, C. (2015). Corporate social responsibility through sport: A longitudinal study of the FTSE100 companies. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 5(3), 218–241. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-10-2014-0044

- Baumgarth, C., & Schmidt, M. (2010). How strong is the business-to-business brand in the workforce? An empirically-tested model of ‘internal brand equity’ in a business-to-business setting. Industrial Marketing Management, 39(8), 1250–1260.

- Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544–559. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR13-4/baxter.pdf

- Baxter, S., Campbell, S., Sanderson, K., Cazaly, C., Venn, A., Owen, C., & Palmer, A. J. (2015). Development of the workplace health savings calculator: A practical tool to measure economic impact from reduced absenteeism and staff turnover in workplace health promotion. BMC Research Notes, 8(1), 457. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1402-7

- Benbya, H., Passiante, G., & Belbaly, N. A. (2004). Corporate portal: A tool for knowledge management synchronization. International Journal of Information Management, 24(3), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2003.12.012

- Berry, L. L., Mirabito, A. M., & Baun, W. B. (2010). What’s the hard return on employee wellness programs? Harvard Business Review, 89(12), 104–112. http://ssrn.com/abstract=2064874

- Boyd, T. C., & Shank, M. D. (2004). Athletes as product endorsers: The effect of gender and product relatedness. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 13(2), 82–93.

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research methods in sport and exercise (pp. 191–205). Routledge.

- Brynjolfsson, E., Hitt, L. M., & Yang, S. (2002). Intangible assets: Computers and organizational capital. Center for eBusiness of MIT.

- Caverley, N., Cunningham, J. B., & MacGregor, J. N. (2007). Sickness presenteeism, sickness absenteeism, and health following restructuring in a public service organization. Journal of Management Studies, 44(2), 304–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2007.00690.x

- Charmaz, K. (2015). Teaching theory construction with initial grounded theory tools: A reflection on lessons and learning. Qualitative Health Research, 25(12), 1610–1622.

- Chavanat, N., Martinent, G., & Ferrand, A. (2009). Sponsor and sponsees interactions: Effects on consumers’ perceptions of brand image, brand attachment, and purchasing intention. Journal of Sport Management, 23(5), 644–670. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.5.644

- Cliffe, S. J., & Motion, J. (2005). Building contemporary brands: A sponsorship-based strategy. Journal of Business Research, 58(8), 1068–1077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2004.03.004

- Conn, V. S., Hafdahl, A. R., Cooper, P. S., Brown, L. M., & Lusk, S. L. (2009). Meta-analysis of workplace physical activity interventions. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 37(4), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.008

- Cornwell, T. B., & Kwon, Y. (2019). Sponsorship-linked marketing: Research surpluses and shortages. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-019-00654-w

- Cornwell, T. B., Weeks, C. S., & Roy, D. P. (2005). Sponsorship-linked marketing: Opening the black box. Journal of Advertising, 34(2), 21–42.

- Costas, J., & Kärreman, D. (2013). Conscience as control–managing employees through CSR. Organization, 20(3), 394–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413478584

- Couraeya, K. S., & Mcauley, E. (1993). Predicting physical activity from intention: Conceptual and methodological issues. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.15.1.50

- Crespo, N. C., Sallis, J. F., Conway, T. L., Saelens, B. E., & Frank, L. D. (2011). Worksite physical activity policies and environments in relation to employee physical activity. American Journal of Health Promotion, 25(4), 264–271. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.081112-QUAN-280

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2017). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., Clark, V. P., & Garrett, A. L. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioural research (pp. 209–240). Sage.

- Crimmins, J., & Horn, M. (1996). Sponsorship: From management ego trip to marketing success. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(4), 11–22.

- Cunningham, S., Cornwell, T. B., & Coote, L. V. (2009). Expressing identity and shaping image: The relationship between corporate mission and corporate sponsorship. Journal of Sport Management, 23(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.23.1.65

- De Chernatony, L., Drury, S., & Segal-Horn, S. (2003). Building a services brand: Stages, people and orientations. The Service Industries Journal, 23(3), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/714005116

- Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

- Djaballah, M., Hautbois, C., & Desbordes, M. (2017). Sponsors’ CSR strategies in sport: A sensemaking approach of corporations established in France. Sport Management Review, 20(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2016.07.002

- Dolphin, R. R. (2003). Sponsorship: Perspectives on its strategic role. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 8(3), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280310487630

- Downward, P., & Rasciute, S. (2011). Does sport make you happy? An analysis of the well-being derived from sports participation. International Review of Applied Economics, 25(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/02692171.2010.511168

- Dubois Gelb, B., & Rangarajan, D. (2014). Employee contributions to brand equity. California Management Review, 56(2), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2014.56.2.95

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550.

- El Akremi, A., Gond, J., Swaen, V., De Roeck, K., & Igalens, J. (2018). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a Multidimensional Corporate Stakeholder Responsibility Scale. Journal of Management, 44(2), 619–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315569311

- Fahy, J., Farrelly, F., & Quester, P. (2004). Competitive advantage through sponsorship: A conceptual model and research propositions. European Journal of Marketing, 38(8), 1013–1030. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560410539140

- Farrelly, F., Greyser, S., & Rogan, M. (2012). Sponsorship linked internal marketing (slim): A strategic platform for employee engagement and business performance. Journal of Sport Management, 26(6), 506–520. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.26.6.506

- Fereday, J., & Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 5(1), 80–92.

- Flöter, T., Benkenstein, M., & Uhrich, S. (2016). Communicating CSR-linked sponsorship: Examining the influence of three different types of message sources. Sport Management Review, 19(2), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.05.005

- Gagné, M., & Forest, J. (2008). The study of compensation systems through the lens of self- determination theory: Reconciling 35 years of debate. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012757

- Gagné, M., Forest, J., Gilbert, M. H., Aubé, C., Morin, E., & Malorni, A. (2010). The motivation at work scale: Validation evidence in two languages. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 70(4), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164409355698

- Gebhardt, D. L., & Crump, C. E. (1990). Employee fitness and wellness programs in the workplace. American Psychologist, 45(2), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.262

- Glazer, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Goetzel, R. Z., Henke, R. M., Tabrizi, M., Pelletier, K. R., Loeppke, R., Ballard, D. W., Grossmeier, J., Anderson, D. R., Yach, D., Kelly, R. K., McCalister, T., Serxner, S., Selecky, C., Shallenberger, L. G., Fries, J. F., Baase, C., Isaac, F., Crighton, K. A., Wald, P., … Metz, R. D. (2014). Do workplace health promotion (wellness) programs work? Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(9), 927–934. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000276

- Golafshani, N. (2003). Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 8(4), 597–606. http://www.nova.edu/ssss/QR/QR8-4/golafshani.pdf

- Golaszewski, T., Allen, J., & Edington, D. (2008). The art of health promotion. American Journal of Health Promotion, 22(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.4278/ajhp.22.4.tahp

- Golaszewski, T., Hoebbel, C., Crossley, J., Foley, G., & Dorn, J. (2008). The reliability and validity of an organizational health culture audit. American Journal of Health Studies, 23(3), 116–123.

- Hair, J. F., Celsi, M., Money, A. H., Samouel, P., & Page, M. (2015). The essentials of business research methods (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Hanstad, D. V., Parent, M. M., & Kristiansen, E. (2013). The Youth Olympic Games: The best of the Olympics or a poor copy? European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(3), 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.782559

- Haskell, W. L., & Blair, S. N. (1980). The physical activity component of health promotion in occupational settings. Public Health Reports, 95(2), 109–118.

- Hickman, T. M., Lawrence, K. E., & Ward, J. C. (2005). A social identities perspective on the effects of corporate sport sponsorship on employees. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 14(3), 148–157.

- Hur, W. M., Moon, T. W., & Choi, W. H. (2019). When are internal and external corporate social responsibility initiatives amplified? Employee engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives on prosocial and proactive behaviors. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(4), 849–858. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1725

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724. https://doi.org/10.5465/256287

- Khan, A. M., & Stanton, J. (2010). A model of sponsorship effects on the sponsor’s employees. Journal of Promotion Management, 16(1-2), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10496490903574831

- Khan, A., Stanton, J., & Rahman, S. (2013). Employees’ attitudes towards the sponsorship activity of their employer and links to their organisational citizenship behaviours. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 14(4), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-14-04-2013-B003

- Kim, Y., Lee, H. W., Magnusen, M. J., & Kim, M. (2015). Factors influencing sponsorship effectiveness: A meta-analytic review and research synthesis. Journal of Sport Management, 29(4), 408–425. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2014-0056

- Kuoppala, J., Lamminpää, A., & Husman, P. (2008). Work health promotion, job well-being, and sickness absences – A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 50(11), 1216–1227. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0b013e31818dbf92

- Kwon, Y., Marzec, M. L., & Edington, D. W. (2015). Development and validity of a scale to measure workplace culture of health. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 57(5), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000000409

- Lechner, L., & Devries, H. (1995). Starting participation in an employee fitness program: Attitudes, social influence, and self-efficacy. Preventive Medicine, 24(6), 627–633. https://doi.org/10.1006/pmed.1995.1098

- Lippke, S., Ziegelmann, J. P., & Schwarzer, R. (2004). Initiation and maintenance of physical exercise: Stage-specific effects of a planning intervention. Research in Sports Medicine, 12(3), 221–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/15438620490497567

- Maze, A., & Alazani, S. (2017). Internal branding and employee brand consistent behaviours: The role of enablement-oriented communication. Mercati & Competitività, 1, 121–139. https://doi.org/10.3280/MC2017-001007

- Meenaghan, T. (1991). The role of sponsorship in the marketing communications mix. International Journal of Advertising, 10(1), 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.1991.11104432

- Meenaghan, T. (2013). Measuring sponsorship performance: Challenge and direction. Psychology & Marketing, 30(5), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20613

- Mellor, V. (1999). Delivering brand values through people. Strategic Communication Management, 3(2), 26–29.

- Mitchell, C. (2002). Selling the brand inside. Harvard Business Review, 80(1), 99–105.

- Morrow, S. L. (2005). Quality and trustworthiness in qualitative research in counseling psychology. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52(2), 250–260. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.2.250

- Odeen, M., Magnussen, L. H., Mæland, S., Larun, L., Eriksen, H. R., & Tveito, T. H. (2013). A systematic review of active workplace interventions to reduce sickness absence. Occupational Medicine, 63(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqs198

- Osborne, J. W., Costello, A. B., & Kellow, J. T. (2008). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. In J. W. Osborne (Ed.), Best practices in quantitative methods (pp. 86–99). Sage Publications Inc.

- Osilla, K. C., Van, K. B., Schnyer, C., Larkin, J. W., Eibner, C., & Mattke, S. (2012). Systematic review of the impact of worksite wellness programs. The American Journal of Managed Care, 18(2), 68–81.

- Parks, K. M., & Steelman, L. A. (2008). Organizational wellness programs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13(1), 58–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.13.1.58

- Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage Publications Inc.

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0213-6

- Pichot, L., Tribou, G., & O’Reilly, N. (2008). Sport sponsorship, internal communications, and human resource management: An exploratory assessment of potential future research. International Journal of Sport Communication, 1(4), 413–423. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.1.4.413

- Pinder, C. C. (2014). Work motivation in organizational behaviour. Psychology Press.

- Pitney, W. A., & Parker, J. (2009). Qualitative research in physical activity and the health professions. Human Kinetics.

- Plewa, C., & Quester, P. G. (2011). Sponsorship and CSR: Is there a link? A conceptual framework. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 12(4), 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-12-04-2011-B003

- Pronk, N. P., & Kottke, T. E. (2009). Physical activity promotion as a strategic corporate priority to improve worker health and business performance. Preventive Medicine, 49(4), 316–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.06.025

- Proper, K. I., Heuvel, V. d., De Vroome, S. G., Hildebrandt, E. M., H, V., & Van der Beek, A. J. (2006). Dose–response relation between physical activity and sick leave. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 40(2), 173–178. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.022327

- Robinson, O. C. (2014). Sampling in interview-based qualitative research: A theoretical and practical guide. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 11(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2013.801543

- Rongen, A., Robroek, S. J., Van Lenthe, F. J., & Burdorf, A. (2013). Workplace health promotion: A meta-analysis of effectiveness. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 44(4), 406–415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2012.12.007

- Rosenberg, M. R., & Woods, K. P. J. B. M. (1995). Event sponsorship can bring kudos and recognition. Brand Marketing, 27(5), 13–18.

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-2004-22201

- Spiggle, S. (1994). Analysis and interpretation of qualitative data in consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(3), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1086/209413

- ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). Staying engaged during the week: The effect of off-job activities on next day work engagement. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 17(4), 445–455. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029213

- Thjømøe, H. M., Olson, E. L., & Brønn, P. S. (2002). Decision-making processes surrounding sponsorship activities. Journal of Advertising Research, 42(6), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.2501/JAR.42.6.6

- Thomas, J. R., Silverman, S., & Nelson, J. (2015). Research methods in physical activity. Human Kinetics.

- Tveito, T. H., Halvorsen, A., Lauvålien, J. V., & Eriksen, H. R. (2002). Room for everyone in working life? 10% of the employees – 82% of the sickness leave. Norsk Epidemiologi, 12(1), 63–68.

- Uden, L., Wangsa, I. T., & Damiani, E. (2007). The future of e-learning: E-learning ecosystem. In Proceedings of the 2007 inaugural IEEE-IES digital ecosystems and technologies conference, 21–23 February (pp. 113–117). Cairns.

- Vallerand, R. J. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 29, pp. 271–360). Academic Press.

- Yauch, C. A., & Steudel, H. J. (2003). Complementary use of qualitative and quantitative cultural assessment methods. Organizational Research Methods, 6(4), 465–481. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428103257362

- Yin, R. K. (2013). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications Inc.

- Zinger, J. T., & O'Reilly, N. J. (2010). An examination of sports sponsorship from a small business perspective. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 11(4), 14–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-11-04-2010-B003