ABSTRACT

Research question

Violations of human rights have been reported in host countries of mega-sport events. Yet, the severity of violations differs between hosts. This study aims to find out whether differences in the severity of violations of human rights issues in potential and actual hosts of the Olympic Games lead to differential consumer evaluations of the Games, and whether Olympic Value perceptions influence evaluations depending on the severity of human rights violations.

Research methods

Two samples from the U.S. were surveyed. In Study 1, participants were informed about the potential hosting of the Olympic Games in countries outside the U.S. with reportedly high-severity vs. low-severity violations of human rights. Study 2 referred to the Los Angeles 2028 Olympic Games and framed the U.S. as a country with either high- or low-severity violations of human rights. It also assessed consumer knowledge about human rights issues and country image.

Results and findings

Attitude toward the Olympic Games was lower in the high (vs. low) severity conditions in both studies. Structural equation modeling results showed that two of the three Olympic value factors predicted consumer attitude in the high (but not in the low) severity conditions, and that attitude as well as some value factors related to intentions to follow the event in both studies.

Implications

Human rights issues in host countries of Olympic Games have negative effects on consumer evaluations. While consumers might still follow the event, value perceptions are important when violations are severe. This makes ethical concerns salient and affects the Olympic Movement.

Introduction

The Olympic Games are the biggest sporting event in the world, staged every two years (with exceptions), attracting people’s attention from all over the world. The governing body, the International Olympic Committee (IOC), has awarded the event to 23 different countries between 1896 and 2028. Violations of human rights have been reported in these host countries and the severity of violations differs between hosts. Human rights, as defined by the United Nations (Citation1948), are the rights that all humans have, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status. Some of the most important human rights are the right to live in freedom, equality, and security; the freedom of opinion and expression; the right to assemble; and the right to work in favorable conditions.

The IOC has been accused of not adequately adopting these rights and their broader meaning in the Olympic Charter. For example, the not-for-profit organization Global Athlete, representing athletes from around the world, along with athlete groups from Canada, Germany, New Zealand, and the U.S. sent a letter to the IOC president, Thomas Bach, on 16 October 2019, to ask for an eighth fundamental principle of Olympism with the following title: ‘The Olympic Movement is committed to respecting all international recognized rights and shall strive to promote the protection of these rights’ (AthletesCAN, Athletes Germany, United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee Athletes’ Advisory Council, New Zealand Athletes Federation, & Global Athlete, Citation2019, p. 1). The authors reason their arguments with ‘ongoing issues of maltreatment, discrimination, denial of freedom expression and barriers to effective representation rampant in today’s sport landscape’ (p. 1). This is just one example of the pressure that is put on the IOC to set agendas and policies to protect and strengthen human rights. Other examples include reports about bad working and living conditions of Olympic site construction workers in host countries, demonstrating host country residents who want to have the commonly agreed human rights installed in their home country and use the event to get attention from media and politics, as well as journalists who want to report about the country, the Olympic Movement, and human rights issues but are threatened if they do so. Within the context of the Olympic Games, there are various examples that provide suggestive evidence for the IOC’s lenient interpretation of whether, and how, potential and actual host countries of the Olympic Games should install measures to protect and promote human rights (e.g. Jefferson Lenskyj, Citation2004).

The present study is concerned with consumers as stakeholders, following the Olympic Games either in the media or as tourists on-site. The goal of the study is to find out whether differences in violations of human rights in potential and actual hosts of the Olympic Games lead to differential evaluations of the Games made by consumers of this event, and whether Olympic Values influence evaluations depending on the severity of human rights violations.

In the next section, I review previous research on human rights violations in host countries of the Olympic Games. Then, the study develops hypotheses about the influence of differences in violations of human rights issues between hosts on consumers’ event evaluations as well as the role of Olympic Values. I present the methods and results of two studies that tested the hypotheses. Finally, I discuss the theoretical and practical implications of the work as well as the limitations and the directions for future research.

Literature review

Human rights violations in the context of the hosting of the Olympic Games

Previous work into human rights issues in the context of hosting the Olympic Games is mostly nonempirical in nature. McGillivray et al. (Citation2019) have proposed a framework for how progressive human rights outcomes may be obtained in the sport event context through the implementation of good governance, democratic participation of stakeholders, formalization of human rights agendas, and deployment of sensitive urban development. It proposes pathways to a human rights-based agenda for bidding, planning, and hosting sport events. The pathways are postulated to lead to prosocial outcomes when host organizations engage with key stakeholders that aim to protect and promote human rights, including when they involve vulnerable populations; their inclusion must happen at the initial stage with the aim to strategically and operatively shape social outcomes. Such frameworks help contextualize previous work that has noted both best-practice examples and examples of exacerbating human rights violations in host countries (Horne, Citation2018).

The main issues that are central to, or have a direct effect on, human rights that have been reported in the context of hosting the Olympic Games include: (1) forced evictions of residents during event preparations and gentrification (Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions, Citation2007; Davis, Citation2010; Freeman, Citation2015; Gaffney, Citation2010, Citation2015; Kennelly & Watt, Citation2012; Olds, Citation1998; Shin & Li, Citation2013; Suzuki et al., Citation2018; Vannuchi & van Criekingen, Citation2015; Watt, Citation2013; Zheng & Khan, Citation2011); (2) abuse of migrant labor in the construction of event facilities (Play Fair, Citation2008; Shantz, Citation2011; Timms, Citation2012); (3) lack of freedom of media and press (Brownell, Citation2012; Burchell, Citation2015; Chadwick, Citation2018); (4) political repression (Mandell, Citation1971; Müller, Citation2017); (5) lack of democratic participation of vulnerable stakeholder groups in decision-making processes (Kennelly, Citation2015; Kennelly & Watt, Citation2012; Suzuki et al., Citation2018; Talbot & Carter, Citation2018; Watt, Citation2013); (6) lack of freedom of opinion and expression for both athletes and nonathletes (Burchell, Citation2015; Coaffee, Citation2015; Jefferson Lenskyj, Citation2004); and (7) sex trafficking (Bourgeois, Citation2009; Caudwell, Citation2018; Deering et al., Citation2012; Finkel & Matheson, Citation2015; Hayes, Citation2010; Ward, Citation2011). However, I note that, despite contributing to apparent human rights abuses, the Olympic Games also represent a political and media platform, where violations can be exposed, contestation can be made visible, and dialogue about progressive change can be facilitated (Liu, Citation2007; McGillivray et al., Citation2019).

Consumer perceptions of human rights violations

On the one hand, athletes who are both producers and consumers of the Olympic Games event have expressed their opinion about preventing and reducing human rights violations. They argue that the commitments to incorporate human rights principles in Host City Contracts, the binding agreement between the awarding body and the host city, are not enough. Here, the IOC included an explicit reference to the United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGP) on Business and Human Rights and enshrined these within the contracts. To protect and promote human rights further, athletes pressured the IOC to adopt an eighth fundamental principle of Olympism (AthletesCAN et al., Citation2019).

On the other hand, non-athletes who follow the Olympic Games in the media or on-site rarely articulate their opinions to the general public, or to the IOC and related stakeholders. There are some examples of boycotts of Olympic Games host residents (e.g. Vannuchi & van Criekingen, Citation2015), but the pressure from the general population worldwide to protect and promote human rights better in the Olympic Games context has been fairly low. This is why institutions such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the Centre for Sport and Human Rights publish position stands and market their ideas to politicians, the media, and the general population in the context of the event hosting. If people from the general population are made aware of violations of human rights in host countries, the IOC and related stakeholders, such as sponsors, sport federations, and the media, might be afraid that the event will be associated with negative attributes, and that this will harm their business. Important stakeholders might then be pressured to change the situation in the host country. Yet, to date, there is no empirical evidence for these mechanisms.

To conclude, I can state that there is a research gap regarding consumers’ perception of human rights issues, and what the actual downstream effects are in the context of Olympic Games hosting. In what follows, the study develops hypotheses about the effects of differences in the severity of violations of human rights issues on attitude toward, and intentions to follow, the Olympic Games, as well as how people’s value perceptions influence these variables.

Hypotheses development

Violations of human rights in host countries of Olympic Games as a predictor of attitude toward, and intentions to follow, the Olympic Games

The literature on transgressions highlights the role of norm violations and harm on individuals’ attitudes towards the entities that are responsible for the transgressions as well as the endorsed products and services. In sport, research has been conducted in the area of transgressions of individuals (e.g. athletes’ doping practices) and sport organizations (e.g. federations’ bribery to win a bid) and consistently revealed negative effects on outside stakeholders’ attitudes towards these entities in the case of transgressions (e.g. Mallon, Citation2000; Solberg et al., Citation2010). The arguments for negative effects are grounded in the empirical literature that shows negative emotions in response to transgressions, including anxiety, hurt, sadness, anger, and hostility (Leary et al., Citation1998; Ohbuchi et al., Citation1989; Rusbult et al., Citation2005) as well as cognitions, including confusion about the event and its implications, the tendency to review events obsessively, and the tendency toward blameful attributions (e.g. Rusbult et al., Citation2005). In the context of the present study, I assume that human rights violations are considered as transgressions that result in negative emotions and cognitions (i.e. components of attitudes). I therefore postulate that severe (vs. no severe) violations in Olympic Games host countries, as a form of transgression, will weaken attitude toward the Olympic Games.

H1: If the Olympic Games are hosted in a country with severe human rights violations, attitude toward the Olympic Games will be lower compared to a situation in which the Olympic Games are hosted in a country without severe human rights violations.

The uniqueness of the Olympic Games is that each Summer and Winter edition is hosted only every four years (with exceptions). They have special features that few or no other mega-sport events can offer (e.g. the inherent reference to the Olympic Movement founded by Pierre de Coubertin; the provision of a field-of-play clean of advertising; Payne, Citation2006). This might explain why spectatorship figures worldwide did not decrease in the case of transgressions (e.g. the bribery scandal in Salt Lake City, the doping scandal in Torino). The event is also unique because of the coverage of various sports at a time and at one location. It attracts world-class athletes from all over the world; for the spectators, there is no alternative to it, given these individuals are interested in world-class sports across disciplines. This leads me to hypothesize that only attitude toward, but not behavioral intentions to follow, the Olympic Games, will be negatively affected by differences in human rights violations in host countries. H2 is formulated as follows:

H2: Consumer intentions to follow the Olympic Games will be unaffected by whether they are hosted in a country with severe human rights violations or in a country without severe violations.

Value perceptions as predictor of attitude toward the Olympic Games

The IOC (Citation2012) refers to (1) excellence, (2) friendship, and (3) respect as Olympic Values (referring to the Olympic Movement in general). Consumer-perceived values in relation to the Olympic Games reflect individuals’ opinions of what the Olympic Games stand for. Koenigstorfer and Preuss (Citation2018) developed a scale that measures Olympic Games-related values from the perspective of individuals. It has three dimensions that are conceptually related to those proposed by the IOC (Citation2012): (1) achievement in competition, (2) friendly relations with others, and (3) appreciation of diversity. These value perceptions influence whether host country residents evaluate the Olympic Games positively or negatively, and whether or not these persons are willing to support the hosting of the event (Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2019).

I argue that the Olympic Games-related values are relevant predictors of attitude toward the Olympic Games when there are severe human rights violations in the host country, but of little relevance when there are no severe violations. Consumers likely base their evaluation of the event on the ethics- and value-related components when countries violate the commonly agreed protection and promotion of human rights. Justice theory postulates that transgressions (here: violations of human rights) pose a threat to shared values (which underlie broken norms when these violations occur) (Vidmar, Citation2000). Human rights link the notions of freedom and social justice. Therefore, human rights are a logical foundation on which to build a cooperative world and to aim for universal justice (Normand & Zaidi, Citation2008). To reaffirm consensus in the presence of violations, attitude toward the event is brought in line with the value perceptions. In the present case, this means that the more highly friendly relations with others and appreciation of diversity are rated – the other-centered dimensions that help a society develop and were found to generate positive outcomes (Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2019) – the higher will be the attitude toward the event. However, the higher achievement in competition is rated – the self-centered dimension that focuses on egoistic goals and thus helps individuals (not the society at large), leading to negative outcomes (Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2019) – the lower will be the attitude.

These ethics- and value-related bases for evaluations become irrelevant when there are no severe human rights violations in the host country. Since there is no or little transgression related to human rights, no assimilation or contrasting between individual-perceived values and the evaluation of the entity (here: the Olympic Games) takes place. H3 is formulated as follows:

H3: Attitude toward the Olympic Games is dependent on value perceptions (i.e. how the Olympic Games are perceived in regard to [a] achievement in competition, with negative relations, as well as [b] friendly relations with others and [c] appreciation of diversity, with positive relations) if the Olympic Games are hosted in a country with severe human rights violations, but is unrelated to value perceptions if Olympic Games are hosted in a country without severe human rights violations.

Relation between attitude toward, and behavioral intentions to follow, the Olympic Games

Attitudes represent evaluations that are of a positive (negative) nature when an individual holds strong beliefs that the evaluated objects are favorable (unfavorable) to them or their goals (Ajzen, Citation1991). As postulated by prominent attitude theories – the Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, Citation1991) and the MODE model (Fazio, Citation1990), to mention but two examples – attitudes should predict behavioral intentions (see Cunningham & Kwon, Citation2003, for a sport spectatorship-specific attitude model). Thus, I postulate that attitude toward the event positively relates to behavioral intentions to follow the event.

H4: Attitude toward the Olympic Games relates positively to behavioral intentions to follow them.

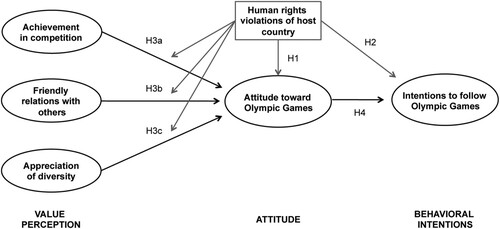

provides an overview of the conceptual model.

Study 1

The goal of Study 1 was to test H1−H4 in the context of a potential hosting of the Olympic Games in countries with reportedly either low- or high-severity violations of human rights. Consumers from outside these countries were surveyed to reveal insights into the proposed mechanisms of how violations as well as values influence attitude toward, and intentions to follow, the event.

Method

Participants

I conducted an online survey with a sample of U.S. residents in August 2019. A large part of the U.S. population frequently follows the Olympic Games on television, with high levels of spectator involvement (Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2018). In 2016, 21.2% of all international visitors came from the U.S., making visitors from the U.S. the most important target group (Brazilian Ministry of Tourism, Citation2016).

Participants were recruited via MTurk and the sample consisted of 711 individuals (MAge = 30.1 years, range between 20 and 77, SD = 7.9; 37.0% females). The gender distribution is close to the figures reported for international visitors of the past hosting of the summer edition (35.7% females; Brazilian Ministry of Tourism, Citation2016). The sample was younger than that reported for the 2016 Olympic Games international visitors (MAge = 37.6 years). Participants stated to have the following highest education levels: high school (2.5%); some college degree (9.6%); bachelor degree (71.0%); master’s degree (18.2%); professional degree (1.0%); and PhD (0.3%) – higher levels compared to the U.S. population (United States Census Bureau, Citation2019). About 16.5% of the sample lived in a single household, 21.0% in a two-person household, and 62.5% in a household with more than two persons.

Procedure and variables

In the survey, participants first rated the extent to which each of the 12 value perception items, plus six control items, could be used to accurately describe the values in relation to the Olympic Games. These values were measured on a seven-point scale from 1 (‘does not describe the values of the Olympic Games at all’) to 7 (‘describes the values of the Olympic Games very well’) (Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2018). Six control items were included to control for potential stylistic response behavior (Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2018; Schwartz, Citation2006). The average of the six control items was subtracted from the mean of each of the three dimensions of the Olympic Value Scale: achievement in competition (e.g. ‘achieving one’s personal best;’ Cronbach’s α = .85); friendly relations with others (e.g. ‘brotherhood;’ α = .83); and appreciation of diversity (e.g. ‘tolerance;’ α = .81).

Next, participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups (using the simple randomization procedure). One half of the participants were asked to imagine that the next bid for the Olympic Games only includes host cities from the following countries: New Zealand, Switzerland, and Taiwan. The other half of the participants were asked to imagine that the next bid for the Olympic Games only includes host cities from the following countries: Egypt, Myanmar (Burma), and Saudi Arabia. They were instructed to assume that the event would be hosted in one of these countries. The countries were chosen based on their ranking on four indices: Freedom in the World (Freedom House, Citation2019); Index of Economic Freedom (Heritage Foundation, Citation2019); Press Freedom Index (Reporters without Borders, Citation2019); and Democracy Index (The Economist Intelligence Unit, Citation2018). New Zealand and Switzerland received best ratings across the four indices; Taiwan received best ratings for two indices as well as second-best ratings for the other two indices. They can hence be classified as countries with reportedly few human rights issues (as covered by these indices). Egypt and Saudi Arabia received the worst ratings for three indices as well as a second-worst rating for one index. Myanmar (Burma) received the worst ratings for one index as well as second-worst ratings for three indices. They are countries with rather serious human rights issues.

Next, participants answered questions that indicated their attitude toward the Olympic Games hosted in one of the aforementioned countries and their behavioral intentions to follow the event. Attitude toward the event was measured using Becker-Olsen’s et al. (Citation2006) three semantic differentials (e.g. ‘negative’ vs. ‘positive;’ α = .91). Behavioral intentions were measured using six items reflecting intentions with respect to media consumption, information search, interactions in social media, merchandise purchase behavior, attendance, and support (e.g. ‘How likely is it that you will watch the Olympic Games on TV/the Internet?’ α = .84; Funk, Citation2002). They were assessed on a seven-point rating scale (anchored at 1 = lowest level of agreement and 7 = highest level of agreement). shows descriptive statistics and differences between experimental groups. The survey ended with descriptive variables and sociodemographics as well as with some variables that tested whether the manipulation worked or not. For the latter, commonly used classifications to measure the level of violations of important human rights were taken to assess participants’ perception of human rights violations. The countries were rated according to the level of ‘freedom to residents’ (rating scale anchored between 1 = ‘not free’, 2 = partly free’, and 3 = ‘free’) (Freedom House, Citation2019); ‘economic freedom’ (1 = ‘repressed’, 2 = ‘mostly unfree’, 3 = ‘moderately free’, and 4 = ‘mostly free’, and 5 = ‘free’) (Heritage Foundation, Citation2019); ‘freedom of press’ (1 = ‘very serious situation’, 2 = ‘difficult situation’, 3 = ‘problematic situation’, 4 = ‘satisfactory situation’, and 5 = ‘good situation’) (Reporters without Borders, Citation2019); and ‘democracy’ (1 = ‘authoritarian regime’, 2 = ‘hybrid system’, 3 = ‘flawed democracy’, and 4 = ‘full democracy’) (The Economist Intelligence Unit, Citation2018).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and differences between experimental groups.

Results

To test whether the manipulation worked, multiple t tests were performed (). The results revealed significant differences between experimental groups (i.e. countries with reportedly few human rights issues vs. countries with reportedly severe human rights issues): freedom of residents, economic freedom, freedom of press, and democracy were evaluated more negatively for countries with severe human rights issues. Thus, the manipulation was successful.

Table 2. Differences in perceptions of human rights issues between experimental groups.

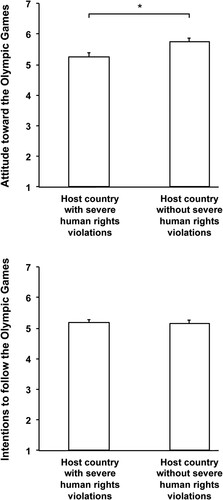

Next, t tests were performed to assess the differences in attitude toward, and intentions to follow, the Olympic Games between the experimental groups (H1 and H2). The results showed that there were significant group differences for attitude (MHigh severity = 5.25, SD = 1.55 vs. MLow severity = 5.67, SD = 1.06; t(709) = –5.15, p < .001, d = .32), in the expected direction, supporting H1, but – as anticipated – no differences for behavioral intentions (MHigh severity = 5.17, SD = 1.22 vs. MLow severity = 5.16, SD = 1.17; t(709) = 0.08, p = .93, d = .01), supporting H2 ().

Figure 2. Consumer attitude toward, and intentions to follow, the Olympic Games depending on whether they are hosted in a country with (vs. without) severe human rights violations (Study 1).

To test H3 and H4, two-group structural equation modeling was performed. Mplus was used to estimate the models (Muthén & Muthén, Citation2017). The exogenous variables were achievement in competition, friendly relations with others, and appreciation of diversity; the endogenous variables were attitude toward the Olympic Games and intentions to follow the event. The three value factors were also modeled to influence intentions.

The sample was divided into two groups depending on the experimental manipulation. All parameters were freely estimated in each group, but the directional structural relationships were constrained to be equal across the two groups, unless a coefficient in one group differed from those in the remaining groups at a significant level of .05 or less. The pattern of invariant and non-invariant paths allows users to identify group differences (Byrne, Citation2012).

The model fit was significantly different between the constrained and the unconstrained model (χ2(7) = 63.26, p < .001), indicating differences between experimental groups (Byrne, Citation2012). The model explained 17% of the variance in attitude and 62% of the variance in behavioral intentions for the group that read about countries with severe human rights violations. The model explained 1% of the variance in attitude and 31% of the variance in behavioral intentions for the group that read about countries without severe human rights violations. This indicates that there are other factors beside the ones that the present study investigated which influence individuals’ intentions to follow the Olympic Games, and how they are evaluated (particularly in the low-severity group).

The fit indices show a satisfactory model fit with CFI = .99, TLI = .96 (both > .90 as recommended by Bentler, Citation1990; Tucker & Lewis, Citation1973), SRMR = .030, and RMSEA = .069 (<.08 and somewhat above the recommended level of .06, respectively; Hu & Bentler, Citation1999) when structural relationships were constrained to be equal across the two groups, unless a coefficient in one group differed from those in the remaining groups at a significant level of .05 or less.

The results for testing H3 and H4 are shown in . For two of the three value perception variables, the relationship between value and attitude was significant when countries with severe human rights issues were described as event hosts (with achievement in competition relating negatively and friendly relations with others relating positively to attitude), while it was nonsignificant for countries without severe violations. Hypotheses 3a and 3b are supported; H3c is not supported (see chi-square difference tests; ). There was a positive relationship between attitude toward, and intentions to follow, the event (supporting H4). The relationship was not significantly different between experimental groups. Furthermore, some values related significantly with behavioral intentions. Achievement in competition related negatively and friendly relations related positively to intentions in both groups; friendly relations with others had a stronger effect on behavioral intentions to follow the event for countries with severe human rights issues, compared to countries without human rights issues.

Table 3. Parameter estimates of structural paths.

The purpose of Study 1 was to find out whether country differences in violations of human rights in potential hosts of Olympic Games lead to differential evaluations made by potential consumers of this event, depending on their perceptions of the Olympic Values. The results showed that attitude toward (but not intentions to follow) a fictitious hosting of the Olympic Games were lower when it was stated that countries with reportedly severe violations of human rights were to become a host country, and that two of the three Olympic value factors predicted attitude when countries with severe (but not without severe) violations of human rights were considered. The negative relation with achievement in competition and the positive relation with friendly relations with others are in agreement with the findings from Koenigstorfer and Preuss (Citation2019). Nevertheless, Study 1 has three important limitations. First, a fictitious event hosting was considered (see Streicher et al., Citation2017, for a similar approach), which lowers the external validity of the findings. Second, nonresidents were surveyed (i.e. persons who might care less about human rights issues in the country). Third, consumer knowledge about the presence (or absence) of human rights violations in the countries was not assessed, except for the variables that tested whether the manipulation worked or not. To address these limitations, I conducted Study 2.

Study 2

The goal of Study 2 was to retest H1–H4 in the context of an actual hosting of Olympic Games (to come), surveying residents from the host country. Differences in severity of violations of human rights (low vs. high) were not manipulated by reference to different host countries, but one country was framed to be a place with either low- or high-severity violations. The framing was expected to influence consumers’ perception of human rights issues in the country. Study 2 controls for knowledge about human rights issues and country image.

Method

Participants

I conducted another online survey with U.S. residents in February 2020. Participants were recruited via MTurk and the sample consisted of 724 individuals (MAge = 42.2 years, range between 19 and 87, SD = 12.9; 49.6% females). None of the participants had participated in Study 1. They had the following highest education levels: high school (10.6%); some college degree (30.1%); bachelor degree (44.0%); master’s degree (11.8%); professional degree (1.9%); and PhD (1.5%). About 30.6% of the sample lived in a single household, 30.3% in a two-person household, and 39.2% in a household with more than two persons.

Procedure and variables

Participants first rated the Olympic Games-related values, plus six control items (α = .85 for achievement in competition, α = .89 for friendly relations with others, and α = .61 for appreciation of diversity). Next, the experimental manipulation took place (simple random assignment). One half of the participants read the following text:

In 2028, the Olympic Games will be hosted in the United States (Los Angeles). The United States as a country is known to protect important human rights like few other countries do. Leading politicians and institutions as well as citizens are internationally congratulated for the United States’ human rights record. The United States receives high marks on human rights compared to relevant peer countries, because of its ratified constitution and constitutional amendments, supported by legislation and judicial precedent.

Participants read the text and then they were asked to mention the human rights (or concrete activities or issues that affect humans and their rights) that are well protected in the U.S., from their perspective (open-answer question). Reading the text and answering the question are assumed to prime participants toward the belief that the U.S. is a country that has few human rights issues.

The other half of the participants read the following text:

In 2028, the Olympic Games will be hosted in the United States (Los Angeles). The United States as a country is known to violate important human rights like few other countries do. Leading politicians and institutions as well as citizens are internationally criticized for the United States’ human rights record. The United States receives low marks on human rights compared to relevant peer countries, because of its violations that are not prevented or reduced by constitution and constitutional amendments, or by legislation and judicial precedent.

Participants read the text and then they were asked to mention the human rights (or concrete activities or issues that affect humans and their rights) that are violated in the U.S., from their perspective (open-answer question). Again, reading the text and responding to the question are assumed to prime participants toward the belief that the U.S. is a country that has many human rights issues.

Next, participants responded to questions that indicated their attitude toward (α = .99), and their behavioral intentions to follow, the event (α = .84; ). The survey ended with descriptive variables and sociodemographics as well as with some variables that tested whether the manipulation worked or not (see Study 1). Country image was measured via 14 items (Martin & Eroglu, Citation1993; α = .87). Consumer knowledge about human rights issues in the U.S. was assessed via 10 true–false questions based on the United Nations’ report on signed and ratified conventions (United Nations, Citation2020; correct responses were coded ‘1’ and incorrect responses or ‘I don’t know’ were coded ‘0’ to form a sum score, ranging from 0 = no knowledge to 10 = great knowledge).

Results

The experimental manipulation was successful (). The testing of H1 and H2 showed that there were significant group differences for attitude (MHigh severity = 5.17, SD = 1.68 vs. MLow severity = 5.86, SD = 1.48; t(722) = −5.90, p < .001, d = .44), supporting H1, and for behavioral intentions to follow the Olympic Games (MHigh severity = 3.75, SD = 1.41 vs. MLow severity = 4.02, SD = 1.42; t(722) = −2.56, p = .01, d = .19), rejecting H2 (). Furthermore, the manipulation influenced country image (an intuitive finding; MHigh severity = 5.50, SD = 0.82 vs. MLow severity = 5.65, SD = 0.85; t(722) = –2.52, p = .01, d = .18), but not knowledge about human rights issues (MHigh severity = 3.42, SD = 2.42 vs. MLow severity = 3.65, SD = 2.48; t(722) = −1.27, p = .20, d = .09).

To test H3–H4, two-group structural equation modeling was performed (see Study 1). The model was identical except for the fact that country image and knowledge about human rights were modeled as additional predictors of attitude and intentions.

The model fit was significantly different between the constrained and the unconstrained model (χ2(11) = 19.97, p = .05), indicating differences between the experimental groups. The model explained 25% (15%) of the variance in attitude and 44% (39%) of the variance in behavioral intentions to follow the Olympic Games for the group that read about the U.S. as a country with (without) severe human rights violations.

The fit indices show a satisfactory model fit, with CFI = .99, TLI = .99 (both > .90), SRMR = .020, and RMSEA = .025 (<.08 and <.06, respectively), when structural relationships were constrained to be equal across the two groups, unless a coefficient in one group differed from those in the remaining groups.

The results for the relationships between the constructs are shown in . Even though they indicate that, similarly to Study 1, achievement in competition relates negatively and friendly relation with others relates positively to attitude toward the event in the high severity (but not in the low severity) condition, chi-square difference tests revealed no statistical significance. H3 is therefore only partly supported. Group differences were found for the relation between country image and attitude (which was stronger in the high-severity condition) and for the relation between appreciation of diversity and behavioral intentions (which was stronger in the low-severity condition). There was a positive relationship between attitude toward, and intentions to follow, the Olympic Games, supporting H4. Furthermore, consumer knowledge (and all value dimensions except appreciation of diversity in the high-severity condition) were found to predict behavioral intentions.

Study 2 complements the findings from Study 1: while H1 and H4 receive support, H2 and H3 receive no, or only partial, support. Study 2 highlights the importance of country image and knowledge about human rights as additional predictors of behavioral intentions to follow the Olympic Games beside values and attitude.

Discussion

Implications

The purpose of the study was to find out whether differences in the severity of violations of human rights issues in hosts of the Olympic Games lead to differential consumer evaluations of the Games, and whether Olympic Values influence evaluations depending on the severity of human rights violations. The study makes five important contributions to the literature on the Olympic Movement: (1) severe human rights violations in host countries of Olympic Games weaken consumer attitudes toward the Olympic Games; (2) when there are severe violations, consumers who perceive that the Olympic Games represent the self-centered value ‘achievement in competition’ evaluate the event more negatively with an increasing perception of this value dimension (while this is not the case when there are no severe violations); (3) when there are severe violations, consumers who perceive that the Olympic Games represent the other-centered value ‘friendly relations with others’ evaluate the event more positively with an increasing perception of this value dimension (while this is not the case when there are no severe violations); (4) behavioral intentions to follow the event are not lower for fictitious Olympic Games when there are severe violations of human rights, surveying nonresidents (Study 1), but they are lower for actual forthcoming Olympic Games, surveying country residents (Study 2). In both contexts, behavioral intentions are influenced by attitude and values. (5) As found in Study 2, knowledge about human rights issues and country image (for the low-severity condition) had additional effects on the outcome variables.

First, this study provides empirical evidence for the negative effect of severe human rights violations in host countries of the Olympic Games on attitude toward the event. The group of stakeholders considered in the present study consists of consumers from the U.S. The findings extend previous research that accused host countries of human rights violations, but lacked in terms of providing evidence for negative effects (e.g. Jefferson Lenskyj, Citation2004). The negative effects found in the present study are mostly in line with the assumptions based on research into transgressions (e.g. Rusbult et al., Citation2005; Solberg et al., Citation2010). The study also provides evidence for the uniqueness of the Olympic Games in the sense that nonresidents’ behavioral intentions to follow them are unaffected by country differences in the severity of violations of human rights (Study 1). The results also provide evidence for the importance of attitudes to predict intentions and might thus inform attitude theories both inside (e.g. Cunningham & Kwon, Citation2003) and outside sports (e.g. Fazio, Citation1990). The effects of consumer-perceived values on behavioral intentions via consumer attitude toward the event must not be neglected. If countries with severe violations of human rights host the event, the resulting negative attitudes might reduce the willingness of potential consumers to follow the event. Thus, the human rights record of Olympic Games host countries matters to consumers.

Second, consumers who agree with statements that the value ‘achievement in competition’ represents what the Olympic Games stand for evaluate the event more negatively with an increasing perception of this value dimension when the event is hosted in a country with severe human rights issues. The negative effects of this value dimension have been shown before (Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2019). Due to the ego orientation of this value dimension, achievement in competition has negative effects; attitude formation is likely a process to reaffirm a lack of consensus (Vidmar, Citation2000). The results are important to the IOC and the Olympic Movement, because they show that – in times of transgressions (here: violations of human rights) – it is particularly relevant to decrease the ego-centric value perception in people. Furthermore, efforts to reduce violations of human rights may help increase consumer evaluations and lower people’s negative perception of the event.

Third, consumers who agree with statements that the value ‘friendly relations with others’ represents what the Olympic Games stand for evaluate the event more positively with an increasing perception of this value dimension when the event is hosted in a country with severe human rights issues. This finding again indicates that value perceptions of the Olympic Games provide an anchor to consumers in situations of violations of human rights issues. In this case, consumers must find a consensus between the positive values that they perceive (here: friendly relations with others; Koenigstorfer & Preuss, Citation2019) and how an entity (here: the host country) acts and the positive value perception provides an important guidance to consumers. The results are again important to the IOC and the Olympic Movement, because they reveal the relevance of value perceptions with positive consequences in times of transgressions (which seem to be common in the context of mega-sporting events; Müller, Citation2017). Thus, marketing the idea that the Olympic Games promote friendship should be beneficial (given the campaigns are credible).

Fourth, the finding that behavioral intentions are not reduced for fictitious Olympic Games, surveying nonresidents (Study 1), but for actual forthcoming Olympic Games surveying residents (Study 2) deserves attention. When there is a transgression (compared to when there is none), the demotivational power of human rights issues likely reduced host-country residents’ interest in following the Olympic Games in their home country, while this was not the case when the event was described to be held abroad. It will be interesting to see how the ongoing discussions in the U.S. about human rights topics such as race discrimination will influence actual interest when the Olympic Games are staged in 2028.

Lastly, Study 2 revealed that both consumer knowledge about human rights issues and country image (the latter was only relevant in the low-severity condition) help predict behavioral intentions to follow the Olympic Games beside values and attitude. The study thus complements research in the event management domain (e.g. Kaplanidou, Citation2006). Educating host residents and increasing their satisfaction with the country they live in might thus increase their intentions to visit, and support, the event – impacts that are desirable from the perspective of event organizers.

Limitations and outlook

The present research has some limitations. First, specific contexts were chosen for the studies. Study 1 presented three countries in each experimental manipulation that might differ on aspects other than violations of human rights (e.g. preference to visit the country and knowledge about these countries). Study 2 considered the U.S. One factor that could not be controlled for in either studies is the different inherent beliefs that participants held about the country’s human rights record that might have influenced their thinking more than the written scenarios. Future research could aim to measure, and control for, differences in beliefs beside values and attitude (such as is done for social movements by Value-Belief-Norm Theory; Stern et al., Citation1999).

Second, MTurk participants have higher education levels compared to the U.S. population (Goodman et al., Citation2013; United States Census Bureau, Citation2019) and, thus, the chances of a participant being aware of the countries included, and the human rights issues within these countries, might have been higher, compared to the general population. Future research may therefore use a representative sample, considering the whole range of education levels, to reveal whether the mentioning of the respective host countries makes people form correct assumptions about the levels of human rights violations.

Third, future research may establish why appreciation of diversity did not have differential effects on attitude toward the event, depending on the severity of human rights violations. One reason might be that participants might have felt that human rights issues have to be interpreted against culturally bound definitions of what human rights are and how they are implemented in the countries when they rated this value dimension.

Lastly, future research might assess whether, and why, residence in the host country might act as a moderator between the relationship of the presence (vs. absence) of human rights violations and consumers’ intentions to follow the event. Consumers’ involvement in country politics as well as in-group membership characteristics might explain differences in the effects, because consumers can be assumed to care more about, and identify with, the country they live in, compared to other countries.

Conclusions

The question of who hosts a mega-sport event such as the Olympic Games, and what the human rights situation in this country is, is subject to debate from the perspective of a variety of stakeholders, including politicians and human rights activists, as well as sport organizations and sponsors. The present study reveals differences in perceptions of U.S. residents (as potential consumers) when there are severe (vs. no severe) violations of human rights. Ideally, countries may strengthen human rights to justify the hosting of mega-sport events and set a good example to the world during the time when the event is planned for, held, and leveraged, as well as in the post-event stage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- AthletesCAN, Athletes Germany, United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee Athletes’ Advisory Council, New Zealand Athletes Federation, & Global Athlete. (2019, October 16). Letter to Dr. Thomas Bach. https://issuu.com/media-globalathlete/docs/2019.10.16_8th_fundamental_principle_of_olympism_-

- Becker-Olsen, K. L., Cudmore, B. A., & Hill, R. P. (2006). The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. Journal of Business Research, 59(1), 46–53. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2005.01.001

- Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107(2), 238–246. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238

- Bourgeois, R. (2009). Deceptive inclusion: The 2010 Vancouver Olympics and violence against first nations people. Canadian Women Studies, 27(2/3), 39–44.

- Brazilian Ministry of Tourism. (2016). Olympic and Paralympic Games: Rio 2016. An overview of tourism planning.

- Brownell, S. (2012). Human rights and the Beijing Olympics: Imagined global community and the transnational public sphere. British Journal of Sociology, 63(2), 306–327. doi:10.1111/j.1468-4446.2012.01411.x

- Burchell, K. (2015). Infiltrating the space, hijacking the platform: Pussy riot. Sochi protests and media events. Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, 12(1), 659–676.

- Byrne, B. M. (2012). Structural equation modeling with Mplus: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Taylor & Francis.

- Caudwell, J. (2018). Sporting events, the trafficking of women for sexual exploitation and human rights. In L. Mansfield, J. Caudwell, B. Wheaton, & B. Watson (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of feminism and sport, leisure and physical education (pp. 537–556). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions. (2007). Fair play for housing rights: Mega-events, Olympic Games and housing rights. COHRE.

- Chadwick, S. (2018, August 24). Sports-washing, soft power and scrubbing the stains. Can international sporting events really clean up a country’s tarnished image? Policy Forum. https://www.policyforum.net/sport-washing-soft-power-and-scrubbing-the-stains/

- Coaffee, J. (2015). The uneven geographies of the Olympic carceral. The Geographical Journal, 181(3), 199–211. doi:10.1111/geoj.12081

- Cunningham, G. B., & Kwon, H. (2003). The theory of planned behaviour and intentions to attend a sport event. Sport Management Review, 6(2), 127–145. doi:10.1016/S1441-3523(03)70056-4

- Davis, L. K. (2010). International events and mass evictions: A longer view. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(3), 582–599. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00970.x

- Deering, K. N., Chettiar, J., Chan, K., Taylor, M., Montaner, J. S., & Shannon, K. (2012). Sex work and the public health impacts of the 2010 Olympic Games. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 88(4), 301–303. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2011-050235

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2018). Democracy index 2018: Me too? Political participation, protest and democracy. The Economist.

- Fazio, R. H. (1990). Multiple processes by which attitudes guide behavior: The MODE model as an integrative framework. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 23, pp. 75–109). Academic Press.

- Finkel, R., & Matheson, C. M. (2015). Landscape of commercial sex before the 2010 Vancouver Winter Games. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(3), 251–265. doi:10.1080/19407963.2014.997437

- Freedom House. (2019). Freedom in the world. https://freedomhouse.org/report/countries-world-freedom-2019

- Freeman, J. (2015). Raising the flag over Rio de Janeiro’s favelas: Citizenship and social control in the Olympic city. Journal of Latin American Geography, 13(1), 7–38. doi:10.1353/lag.2014.0016

- Funk, D. (2002). Consumer-based marketing: The use of micro-segmentation strategies for under-standing sport consumption. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 4(3), 39–64. doi:10.1108/IJSMS-04-03-2002-B004

- Gaffney, C. (2010). Mega-events and socio-spatial dynamics in Rio de Janeiro, 1919–2016. Journal of Latin American Geography, 9(1), 7–29. doi:10.1353/lag.0.0068

- Gaffney, C. (2015). Gentrifications in pre-Olympic Rio de Janeiro. Urban Geography, 37(8), 1132–1153. doi:10.1080/02723638.2015.1096115

- Goodman, J. K., Cryder, C. E., & Cheema, A. (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(3), 213–224. doi:10.1002/bdm.1753

- Hayes, V. (2010). Human trafficking for sexual exploitation at world sporting events. Chicago-Kent Law Review, 85(3), 1105–1146.

- Heritage Foundation. (2019). Index of economic freedom. https://www.heritage.org/index/ranking

- Horne, J. (2018). Understanding the denial of abuses of human rights connected to sports mega-events. Leisure Studies, 37(1), 11–21. doi:10.1080/02614367.2017.1324512

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- IOC. (2012). Olympism and the Olympic Movement. IOC Olympic museum.

- Jefferson Lenskyj, H. (2004). The Olympic industry and civil liberties: The threat to free speech and freedom of assembly. Sport in Society, 7(3), 370–384. doi:10.1080/1743043042000291695

- Kaplanidou, K. (2006). Affective event and destination image: Their influence on Olympic travelers’ behavioral intentions. Event Management, 10(2), 159–173. doi:10.3727/152599507780676706

- Kennelly, J. (2015). ‘You’re making our city look bad’: Olympic security, neoliberal urbanization, and homeless youth. Ethnography, 16(1), 3–24. doi:10.1177/1466138113513526

- Kennelly, J., & Watt, P. (2012). Seeing Olympic effects through the eyes of marginally housed youth: Changing places and the gentrification of East London. Visual Studies, 27(2), 151–160. doi:10.1080/1472586X.2012.677496

- Koenigstorfer, J., & Preuss, H. (2018). Perceived values in relation to the Olympic Games: Development and use of the Olympic value scale. European Sport Management Quarterly, 18(5), 607–632. doi:10.1080/16184742.2018.1446995

- Koenigstorfer, J., & Preuss, H. (2019). Olympic Games-related values and host country residents’ pre-event evaluations in the run-up to the 2016 Olympic Games. Journal of Global Sport Management, forthcoming. doi:10.1080/24704067.2019.1669065

- Leary, M. R., Springer, C., Negel, L., Ansell, E., & Evans, K. (1998). The causes, phenomenology, and consequences of hurt feelings. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(5), 1225–1237. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1225

- Liu, J. H. (2007). Lighting the torch of human rights: The Olympic Games as a vehicle for human rights reform. Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights, 5(2), 213–235.

- Mallon, B. (2000). The Olympic bribery scandal. Journal of Olympic History, 8, 11–27.

- Mandell, R. D. (1971). The Nazi Olympics. Macmillan.

- Martin, I. M., & Eroglu, S. (1993). Measuring a multi-dimensional construct: Country image. Journal of Business Research, 28(3), 191–210. doi:10.1016/0148-2963(93)90047-S

- McGillivray, D., Edwards, M. B., Brittain, I., Bocarro, J., & Koenigstorfer, J. (2019). A conceptual model and research agenda for bidding, planning and delivering major sport events that lever human rights. Leisure Studies, 38(2), 175–190. doi:10.1080/02614367.2018.1556724

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Müller, M. (2017). How mega-events capture their hosts: Event seizure and the World Cup 2018 in Russia. Urban Geography, 38(8), 1113–1132. doi:10.1080/02723638.2015.1109951

- Normand, R., & Zaidi, S. (2008). Human rights at the UN: The political history of universal justice. Indiana University Press.

- Ohbuchi, K.-i., Kameda, M., & Agarie, N. (1989). Apology as aggression control: Its role in mediating appraisal of and response to harm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 219–227. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.219

- Olds, K. (1998). Urban mega-events, evictions and housing rights: The Canadian case. Current Issues in Tourism, 1(1), 2–46. doi:10.1080/13683509808667831

- Payne, M. (2006). Olympic turnaround: How the Olympic Games stepped back from the brink of extinction to become the world’s best known brand. Praeger Publishers.

- Play Fair. (2008). Playfair 2008: No medal for the Olympics on labour rights. International Trade Union Confederation, International Textile, Garment and Leather Workers’ Federation, Clean Clothes Campaign.

- Reporters without Borders. (2019). Press freedom index. https://rsf.org/en/ranking

- Rusbult, C. E., Hannon, P. A., Stocker, S. L., & Finkel, E. J. (2005). Forgiveness and relational repair. In E. L. Worthington Jr (Ed.), Handbook of forgiveness (pp. 185–205). Routledge.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2006). Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations. In R. Jowell, C. Roberts, R. Fitzgerald, & G. Eva (Eds.), Measuring attitudes cross-nationally – lessons from the European social survey (pp. 169–203). Sage.

- Shantz, J. (2011). Discrimination against Latin American workers during pre-Olympic Games construction in Vancouver. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 23(1), 75–80. doi:10.1007/s10672-010-9166-7

- Shin, H. B., & Li, B. (2013). Whose Games? The costs of being “Olympic citizens” in Beijing. Environment and Urbanization, 25(2), 559–576. doi:10.1177/0956247813501139

- Solberg, H., Hanstad, D., & Thøring, T. (2010). Doping in elite sport – do the fans care? Public opinion on the consequences of doping. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 11(3), 2–16. doi:10.1108/IJSMS-11-03-2010-B002

- Stern, P., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human Ecology Review, 6(2), 81–97. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24707060

- Streicher, T., Schmidt, S. L., Schreyer, D., & Torgler, B. (2017). Is it the economy, stupid? The role of social versus economic factors in people’s support for hosting the Olympic Games: Evidence from 12 democratic countries. Applied Economics Letters, 24(3), 170–174. doi:10.1080/13504851.2016.1173175

- Suzuki, N., Nagawa, T., & Inaba, N. (2018). The right to adequate housing: Evictions of the homeless and the elderly caused by the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo. Leisure Studies, 37(1), 89–96. doi:10.1080/02614367.2017.1355408

- Talbot, A., & Carter, T. (2018). Human rights abuses at the Rio 2016 Olympics: Activism and the media. Leisure Studies, 37(1), 77–88. doi:10.1080/02614367.2017.1318162

- Timms, J. (2012). The Olympics as a platform for protest: A case study of the London 2012 ‘ethical’ Games and the Play Fair campaign for workers’ rights. Leisure Studies, 31(3), 355–372. doi:10.1080/02614367.2012.667821

- Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1–10. doi:10.1007/BF02291170

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. In General assembly resolution 217 A (III). December 10, 1948. Paris: United Nations General Assembly.

- United Nations. (2020). Ratification status for United States of America. https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=113&Lang=EN

- United States Census Bureau. (2019). Educational attainment in the United States: 2018. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/education-attainment/cps-detailed-tables.html

- Vannuchi, L., & van Criekingen, M. (2015). Transforming Rio de Janeiro for the Olympics: Another path to accumulation by dispossession? Articulo – Journal of Urban Research, 7.

- Vidmar, N. (2000). Retribution and revenge. In J. Sanders & V. L. Hamilton (Eds.), Handbook of justice research in law (pp. 31–63). Kluwer/Plenum.

- Watt, P. (2013). It’s not for us. City, 17(1), 99–118. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.754190

- Zheng, S., & Khan, M. E. (2011). Does government investment in local public goods spur gentrification? Evidence from Beijing. Working Paper 17002. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Ward, H. (2011). The safety of migrant and local sex workers: Preparing for London 2012. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 87(5), 368–369.