ABSTRACT

Research question

Our study investigates the relationship between elite sport performance and sportive nationalism in Great Britain.

Research methods

We utilise the Taking Part Survey (TPS), which gathers data from a representative sample of around 10,000 adults aged 16 and over residing in England each year. Between July 2011 and March 2016, the TPS included a question to identify the components of national pride in Great Britain. We examined ‘British sporting achievements’ as one of 12 domains that made people in England feel most proud of the country (Great Britain). The determinants of sportive nationalism were assessed using logistic regression analysis. Associations between monthly variations in sportive nationalism (57 data points) and specific events that might influence its level were explored.

Results and Findings

Sportive nationalism was shown by only a small minority of the sample and was typically of a lesser magnitude compared with other more stable factors such as the British countryside, its history and health service. Certain population segments were more inclined to be sportive nationalists such as those who participated in sport or followed it online. Changes in sportive nationalism were seen to coincide with the performances of British athletes and teams, albeit these were temporary in nature.

Implications

Our study provides limited evidence to justify government investment in elite sport on the grounds of success generating national pride. A wide range of events might influence sportive nationalism and reductions in this domain of national pride may be associated with both perceived failure and a general waning effect.

Introduction

There is growing discussion in the elite sport development literature about the wider social impacts of elite sport. In their ‘polemic’, Grix and Carmichael (Citation2012) challenge the anecdotal evidence that elite sport success is part of a ‘virtuous circle’ that delivers societal outcomes such as international prestige, a ‘feelgood factor’, and increased sports participation. The societal impacts from elite sport success are said to be ‘trickle-down’ effects (Frick & Wicker, Citation2016) or ‘demonstration’ effects (Weed et al., Citation2015) and imply a causal relationship (Coalter, Citation2013). Pioneering research to capture the range of societal benefits (and dangers) of elite sport, has been conducted by De Rycke and De Bosscher (Citation2019). They found some 391 studies across ten broad themes, both positive and negative, linked to elite sport success. The second of these themes, ‘collective identity and pride’ contained 51 papers. However, only a minority relate to national pride through sport and confirm that the subject requires further research.

Our study focuses on the relationship between elite sport performance and national pride and is based in the United Kingdom. The UK is widely referred to in sporting circles as ‘Great Britain’ in line with its International Olympic Country code ‘GBR’. Generally, the UK competes in international competition as GBR, although there are also examples of where the UK’s four home nations compete as separate entities notably in football.

Elite sport policy is coordinated centrally at UK level. Since 1982, elite sport policy in the UK has evolved from being laissez faire, whereby intervention was ‘neither tradition nor policy’ (GB Sports Council, Citation1982), to a belief that sporting success enhances national pride as stated in the strategy for sport, Sporting Future,(HM Government, Citation2015, p. 74) ‘major sporting success leads to great national pride’.

Following this introduction, we review relevant literature, explain our methods and data sources, present and discuss the results, before making conclusions and recommendations for future research.

Literature review

Terminology

National pride has been recognised in the literature for many years, notably in the contexts of globalisation (Tilley & Heath, Citation2007) and nationalism and patriotism (Houlihan, Citation1997; Smith & Kim, Citation2006). Kersting (Citation2007, p. 279) suggests that ‘nationalism, national pride and patriotism are often used as synonyms for national identity’. All forms of national identity are socially constructed, meaning that definitions are not fixed and are formed by the collective views and values of society. By implication, different attitudes and values may become predominant in different contexts (Kersting, Citation2007).

The concepts of national identity and national pride are inter-related. However, as the following definitions illustrate, they each have distinct meanings. Smith and Kim (Citation2006, p. 1) state

National identity is the cohesive force that both holds nation states together and shapes their relationships with the family of nations. National pride is the positive effect that the public feels towards their country as a result of their national identity.

National pride is related to feelings of patriotism and nationalism. Patriotism is love of one’s country or dedicated allegiance to the same, while nationalism is a strong national devotion that places one’s own country above all others. National pride co-exists with patriotism and is a prerequisite of nationalism but nationalism extends beyond national pride … (Smith & Kim, Citation2006, p. 1)

A third conceptualisation, which is essentially a constrained choice version of ‘national sporting pride’, is offered by Meier and Mutz (Citation2016), who presented their sample with a list of seven domains and asked them to select up to three of these to signify what made them proud of Germany. Those who selected ‘achievements of German athletes’, were described as ‘sportive nationalists’. In essence ‘sportive nationalists’ exhibit national sporting pride and amplify this pride by indicating that it is one of the top three characteristics that makes them proud of (in this case) Germany. Our data are derived in a similar way, except that our study consists of more domains (12 v 7). For consistency, hereafter we also use the term ‘sportive nationalists’ to describe those in our sample who chose sporting achievements as one of their top three domains for being proud of Great Britain.

Previous sporting pride and national sporting pride research

Quantitative research into sporting pride and national sporting pride has been undertaken since 1995. Nevertheless, peer-reviewed publications in the sport management literature are a relatively new phenomenon (2002 onwards). An overview of the relevant literature including the number of different nations covered in previous studies, the data sources and the number of data points compiled is shown in .

Table 1. Previous research on sporting pride and national sporting pride.

Nation-specific studies

Nation-specific research into sporting pride and national sporting pride has been conducted in Germany (Gassmann et al., Citation2020; Hallmann et al., Citation2013; Haut et al., Citation2016; Kersting, Citation2007; Meier & Mutz, Citation2016;); the USA (Denham, Citation2010); the Netherlands (Elling et al., Citation2014; Van Hilvoorde et al., Citation2010); South Africa (Kersting, Citation2007); Singapore (Leng et al., Citation2014) and Hungary (Dóczi, Citation2012). Related research on a different measure called ‘sporting patriotism’ has also been carried out in Germany (Mutz, Citation2018). Thus, apart from the ISSP data, there is no published data on the subject relating to Great Britain, which is therefore a gap in knowledge.

Generally, these nation-specific studies are highly consistent with the ISSP findings as they confirm high levels of pride in sporting achievements (USA: 74% in 1996, 76% in 2004; the Netherlands: 70% to 80% at various points between May 2008 and July 2010; and Hungary: 85% in 2007). Where some studies provide further insight is by linking the measurement of pride to specific sporting events. For example, Kersting (Citation2007) measured general national pride in Germany by three waves of interviews conducted before during and after the 2006 FIFA World Cup, hosted in Germany. This study found that feelings of being ‘very proud’ or ‘proud’ of Germany were 71% before the event, 78% during it and 72% after it, with the author concluding (p. 283):

This phenomenon [i.e. the increase to 78% during the event] can only be explained by the euphoria existing during the World Cup.

More recently, Gassmann et al. (Citation2020) observed the temporal impact of sporting success in a study on the effects of the 2014 and 2018 FIFA World Cup tournaments on German national pride. Using the German General Social Survey to measure national pride before, during and after the World Cup, they found that when the German national team won the tournament in 2014 there was a small but significant increase. Whereas in 2018, when Germany was eliminated in the group stages, there was a small but significant decrease in national pride. In both cases, the effects were found to be temporary, confirming the findings of Elling et al. (Citation2014) and Van Hilvoorde et al. (Citation2010).

Multi-nation analysis

In contrast to the findings of much existing research on international sporting success and national pride, Storm and Jakobsen (Citation2020) found that winning medals did not have a significant effect on national pride. They analysed data from six rounds of the World Values Survey (WVS) and four rounds of the European Values Study (EVS) covering 96 countries and 253 country-survey-years (data points). Storm and Jakobsen (Citation2020) suggested their findings may be explained by the macro-level scale of the data analysis, which provides strength in terms of identifying generalised trends, but may obscure the existence of a relationship between medal success and pride in more local settings. They recommended future research should have a national focus and further investigate specific groups that are affected by international sporting success. Our study responds to this call for nation-specific research. In addition, we contend that the breath and scale of data included in Storm and Jakobsen (Citation2020) may actually be a limiting factor in the analysis of national pride. Their data related to a minimum data point of one year for each country included and a theoretical maximum of 10 years. As previous research identifies that variations in sporting pride/national sporting pride are short term (typically less than one year), it is unlikely that analysis of annual data is sufficiently granular to demonstrate the effect. We therefore argue that further research is needed at both the level of the nation state, and over more frequent data points. Our study also responds to the call of Elling et al. (Citation2014, p. 148) who recommended:

For future research we suggest a higher frequency of assessments and larger sample groups to strengthen the validity and reliability of the data.

Variations in sporting pride and national sporting pride

Whilst much of the published research focuses on variations between nations (e.g. Evans & Kelley, Citation2002; Meier & Mutz, Citation2016), there is some research which looks at variations within national samples (e.g. Denham, Citation2010; Dóczi, 2011; Hallmann et al., Citation2013). There are significant differences in levels of sporting pride or national sporting pride with notably higher scores amongst men rather than women (Denham, Citation2010), although this finding was reversed in Germany during the FIFA Women’s World Cup (Hallmann et al., Citation2013); people with lower educational attainment (Haut et al., Citation2016), people with higher educational attainment (Dóczi, Citation2012); sport participants rather than non-participants (Elling et al., Citation2014); older rather than younger people (Denham, Citation2010; Dóczi, Citation2011); and, non-immigrants rather than immigrants (Elling et al., Citation2014). In their sportive nationalism study, Meier and Mutz (Citation2016) found significantly elevated scores amongst men, younger people, and those with lower levels of education. Against this backdrop of findings that are seemingly nation-specific, the case of Great Britain and ‘sportive nationalism’ is fertile territory for new insights into how sporting achievements impact upon a type of national sporting pride.

Evidence from the ISSP datasets

A common factor in national pride studies is the use of transnational datasets such as the WVS, Eurobarometer, and the ISSP. These data sources are readily available online and have facilitated numerous transnational research studies across a range of issues (e.g. Evans & Kelley, Citation2002; Gassmann et al., Citation2020; Kersting, Citation2007; Pawlowski et al., Citation2014; Storm & Jakobsen, Citation2020). In particular, the ISSP has been used in previous studies to investigate sporting pride and national sporting pride.

The ten domain-specific sources of pride from the ISSP's National Identity modules are shown in , which reveals that for the overall multi-nation sample the ‘achievements in sport’ domain, or sporting pride, was consistently ranked the highest for the combined positive scores of ‘very proud’ and ‘somewhat proud’. The overall picture is of relative stability with only minor fluctuations in virtually all domain scores over time.

Table 2. Domain-specific pride from the ISSP surveys (‘very proud’ / ‘somewhat proud’ responses).

However, the same pattern of relative stability is not necessarily seen for individual nations as demonstrated by Great Britain in , where the highest domain-specific scores are achieved for the nation’s history, its Armed Forces, and its scientific and technological achievements. Achievements in sport have a lowest rank of 7th in 2003 and a highest rank of 3rd in 2013. There is greater volatility in the Great Britain scores than the overall sample, with the dominant trend being increased domain-specific pride between 1995 and 2013. Great Britain’s sporting pride score increased by 20 percentage points between 2003 and 2013, which coincided with bidding for, winning, and delivering the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games, as well as improved performances in the Olympic Games of 2004 and 2008.

In examining the more stringent concept of ‘national sporting pride’ in the ISSP data, we find again that scores are positive, with ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ scores accounting for the majority of responses for both the sample as a whole and Great Britain. In we illustrate this point by showing the scores for the subset of 12 nations that took part in all three ISSP surveys overall as well as Great Britain in isolation.

Table 3. Agreement with the statement: ‘When my country does well in international sports, it makes me proud to be [country, nationality]’.

For all three data points, the Great Britain sample had lower combined positive scores than the sample averages. There was an improvement in Great Britain's score between 2013 and 2003 to a similar level as in 1995. These relatively modest movements in national sporting pride are consistent with Van Hilvoorde et al. (Citation2010, p. 87), who concluded

This supports the notion of national pride being a rather stable characteristic of countries; notwithstanding specific situations (such as sport success) that may lead to minor and temporary fluctuations.

Table 4. Domain-specific athletic pride scores (ranks) in East and West Germany 1992–2008.

Whilst in 1992 and 1996 athletic pride was selected by the majority of respondents in East Germany and was ranked second out of the seven options, in 2000 and 2008 it was only a minority of East Germans who selected athletic pride and its rank fell from 2nd to 4th over the same period. By contrast, in West Germany 20% to 27% of the sample selected athletic pride and it was consistently ranked 6th out of the seven options available. Meier and Mutz (Citation2016, p. 6) concluded

Pride in athletic achievements represents an important source of national pride, but other societal domains, such as economy, science and culture are more important.

Research questions

In this paper, we contribute to knowledge by analysing the relationship between elite sport performance and the measure of national pride known as sportive nationalism in Great Britain. We pose three research questions (RQs) that arise from the literature and that can be examined using our study sample, which consists of adults residing in England.

RQ1: To what extent are the achievements of British athletes and teams in elite sport a component of national pride among adults in England?

RQ2: What are the determinants of sportive nationalism?

RQ3: Can short-term fluctuations in sportive nationalism be mapped against specific sporting successes and failures?

Methods

Data sources

The data for this research is the Taking Part Survey (TPS), which is commissioned by the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), and three of the major organisations it funds (DCMS, Citation2012). TPS is a continuous face-to-face household survey of adults aged 16+. It has been conducted by national market research agencies since 2005 and interviews a representative sample of around 10,000 adults in England annually. TPS is a ‘National Statistic’, which means that it has been produced to the standards set out in the Code of Practice for Official Statistics (UK Statistics Authority, Citation2012).

Measuring sportive nationalism

Between July 2011 and March 2016, the TPS included a question designed to identify the components of national pride in Great Britain. ‘British sporting achievements’ was one of the 12 options for this question and respondents were allowed to select up to three options as shown in the box below.

Looking at this list, what, if anything makes you most proud of Britain? You can choose up to three.

1 The British countryside and scenery

2 The British people

3 British history

4 British sporting achievements

5 British arts and culture (music, film, literature, art etc.)

6 British architecture and historic buildings

7 British education and science

8 The British legal system

9 Britain’s democratic tradition

10 British health service

11 British multiculturalism

12 The British Monarchy

13 None of these things

14 Don’t know

15 Refused

There are approximately 830 respondents to TPS per month, which provides a robust sub-sample of responses with which to measure and analyse variations in sportive nationalism. The question is similar in style to that used by Meier and Mutz (Citation2016) in that it asks respondents to choose up to three options, but from a longer and somewhat different list.

Data analysis

We analysed the data relating to the national pride question in TPS in three ways. For RQ1, we examined the scores for each of the 12 domains on an annual basis and looked at ‘British sporting achievements’ relative to the other domains that made people feel most proud of their country. For RQ2, logistic regression analysis was conducted on the 2012/13 TPS data (n=9838) to establish if any demographic segments showed significantly different levels of sportive nationalism. 2012/13 was the year with the highest reported frequency for ‘British sporting achievements’ being a component of pride in Great Britain. Logistic regression analysis was chosen because the dependent variable was binary, where a value of ‘0’ represents that ‘British sporting achievements’ was not selected by survey respondents and a value of ‘1’ indicates that this option was chosen. A full list of variables included in the logistic regression model is presented in .

Table 5. Overview of variables included in the logistic regression model.

In addition to the socio-demographic profile of survey respondents such as sex, age, educational qualifications and social class, variables that provided an indication of their wider interest in sport and of their general sense of wellbeing (happiness) were included. The selection of these independent variables was informed by previous research from other countries on the beneficiaries of pride associated with elite sporting success (Hallmann et al., Citation2013), as well as the contribution of sporting success to the generation of national pride (Elling et al., Citation2014; Meier & Mutz, Citation2016). The final selection of variables for the regression analysis was determined ultimately by the range of data that could be extracted from the dataset.

For the dummy independent variables, values coded as ‘0’ were treated as the reference (base) categories. Multicollinearity was checked using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, which revealed that the variance inflation factors were less than two, which is within the suggested threshold of ten (Hair et al., Citation2006). Moreover, the correlations between the independent variables included in the model were all less than 0.4, which is below the suggested cut-off threshold of 0.9 (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2007). The results of the logistic regression were interpreted from the odds ratios (i.e. Exp(B)) of the independent variables, with an odds ratio greater than 1 signifying a positive association, and an odds ratio less than 1 signifying a negative association, with the dependent variable (‘Pride’).

For RQ3, building on the work of Elling et al. (Citation2014), who made 27 assessments of sporting pride over two years and two months, we plotted 57 consecutive monthly scores for sportive nationalism to examine the potential influence of the performances of British athletes and teams around the time of some major sports events.

Limitations

Whilst there are advantages of secondary data analysis, particularly in relation to national data sets, the principal limitation is that users can only work with the variables that are available. Although TPS is conducted to high standard and runs continuously, the sporting pride question was first asked in July 2011 and thus there are three months during 2011 when the question was not asked. The shortest time period for which data can be analysed is one month (c. 830 surveys). For these reasons, we have 57 data points (four years and nine months rather than a full five years). We are therefore restricted to analysing the data in the month during which elite sporting success or failure occurred, rather than more granular time periods such as specific days or weeks. Finally, TPS interviews people living in England only and does not interview in the other three home nations that make up the United Kingdom. Although the population of England is 84.4% of the entire UK population, the views of residents of England are not necessarily representative of people who reside in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Our analysis utilises a constrained choice question from the TPS. It has been suggested that the constrained choice format is a somewhat contested method that should be replaced by rating scales (Meier & Mutz, Citation2016). In our study these problems are mitigated by the greater choice of variables; options such as ‘none of the above’; and no requirement to makes three selections.

Results and discussion

The prevalence of sportive nationalism

The annual scores for sportive nationalism and the other domains of national pride from the five waves of the TPS under review are shown in . The British sporting achievements option had a mean annual score of around 16%, making it the eighth highest ranked domain out of the 12 options over this time frame. The average score for Great Britain in our study is lower than the corresponding scores found by Meier and Mutz (Citation2016) in East Germany (23% on average) and West Germany (48% on average). One potential explanation for this finding might be that the German population takes greater pride in its nation's sporting achievements than the English population attaches to the performances of athletes and teams representing Great Britain. Alternatively, as there were nearly twice as many options to choose from in our study (12) than Meier and Mutz's (Citation2016) study (7) it may be the case that the responses from our sample have been diluted over the greater range of choices. If this interpretation is correct, then it is reasonable to infer that the list of factors that cause people to be proud of their country is more than the ten domains in the ISSP data sets (ISSP Research Group, Citation1998, Citation2012, Citation2015) and more than the seven domains in the German data set used by Meier and Mutz (Citation2016).

Table 6. The components of what makes people most proud of Britain.

Sportive nationalism in Great Britain scored much lower than the three choices that appeared consistently in the top three, namely: the British countryside and scenery (a mean score of 59%); the British health service (41%); and British history (38%). Like the Meier and Mutz (Citation2016) research, when respondents were presented with a constrained choice rather than an unconstrained choice, our study confirms that sporting achievement tends to be ranked lower than some more dominant measures of national pride. Because of the constrained choice nature of the TPS question, if one domain of national pride increases, it follows that at least one other domain must decrease. In the 2012/13 TPS year, London hosted the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games at which Great Britain performed well, achieving third place in the medals’ table. During the same period, Queen Elizabeth II celebrated 60 years (Diamond Jubilee) as the ruling monarch. Between 2011/12 and 2012/13, sportive nationalism in Great Britain increased by nearly ten percentage points and national pride associated with the British monarchy increased by around three percentage points. Two other domains of national pride demonstrated minor gains (of less than one percentage point each) during this time frame: arts and culture; and, multiculturalism. To compensate for these increases, there were minor decreases in eight of the other domains of national pride (ranging from less than one percentage point for the health service to three percentage points for British history).

Based on these findings, it can be argued that the country's sporting achievements represents a relatively minor component of national pride in Great Britain amongst adults when using the TPS question. What our data also show is that the various domains of national pride have different levels of volatility. Domains like the legal system, and multiculturalism tend to be relatively static and therefore national pride linked to these domains is less susceptible to change in the short term, whereas sporting successes and failures are more dynamic phenomena that make sportive nationalism more susceptible to short term fluctuations. As illustrated by the data in , sportive nationalism exhibited the greatest level of volatility with a range of nearly ten percentage points between its lowest and highest annual scores and a standard deviation of 4.1%. In comparison with British sporting achievements, other domains of national pride in Great Britain remained relatively stable. This latter finding is consistent with the work of Elling et al. (Citation2014, p. 129) in the Netherlands

However the results indicate that national pride is a rather stable characteristic of national identification that cannot easily be increased by improving national sporting success and winning more Olympic medals.

The determinants of sportive nationalism

The profile of the sample upon which this analysis was based is presented first, followed by the results of the regression model.

Sample profile

Overall, 55.5% of the TPS 2012/2013 sample was female and 44.5% was male. The age of the sample varied between 16 and 99 years with a mean age of 52 years. Around 92.1% of the survey respondents described their ethnic origin as ‘white’ and 36.7% reported having a longstanding illness or disability. Some 51.4% had achieved at least A-level education or equivalent and 57.9% were classified as belonging to a higher socio-economic group (termed as NS-SEC 1–4 in the UK). Of the sport-related independent variables, 40.7% had participated in some form of sport or recreational physical activity in the four weeks prior to being surveyed, 34.7% had browsed sports websites in the previous year and 74.3% said they supported the UK's decision to host the 2012 Olympic Games. Finally, the mean self-reported happiness score for the sample was 7.8 out of ten.

Regression findings

The results of the logistic regression analysis are presented in , including the regression coefficient (B), the Wald statistic (to test the statistical significance) and the odds ratio [Exp (B)] for each variable category. The logistic regression model was statistically significant (χ2 = 494.631; −2LL = 8572.562; p < .001), with Nagelkerke’s R2 of 0.084, which means that the model explains around 8.4% of the variation in the dependent variable ‘Pride’. The model correctly classified 80.0% of cases and the Hosmer & Lemeshow test indicated that the model was a good fit to the data (p = 0.245).

Table 7. Results of the logistic regression analyses for sportive nationalism.

Most of the independent variables contributed significantly to the model. The variables ‘Age’, ‘Ethnicity’, ‘Education’, ‘NSSEC’, ‘Internet’, ‘Participant’ and ‘Support’ were all significant predictors of ‘Pride’ at the 1% level (p < 0.01). ‘Sex’ was not significant at the 5% level (p > 0.05) but was significant at the 10% level (p < 0.10). The ‘Disability’ and ‘Happiness’ variables were both insignificant at the 10% level (p > 0.10).

The probability of selecting ‘British sporting achievements’ as a component of national pride increased significantly among men, those from a white ethnic group, those accessing sport content online, those who were physically active and those who were supportive of the UK hosting London 2012. Those who supported the hosting London 2012 were over three times more likely to cite ‘British sporting achievements’ as something that made them feel most proud of Britain [Exp(B) = 3.18], than those who did not. The odds ratios associated with being older, having a better level of education, and belonging to a more affluent socio-economic group were all less than 1, indicating that they had a negative effect on ‘Pride’.

Our findings on the determinants of sportive nationalism are highly consistent with Meier and Mutz (Citation2016), who concluded that this concept of pride in Germany was more common among younger generations, males, individuals with lower and medium educational levels, and lower income groups. Our findings related to gender and educational attainment are consistent with other nation-specific research by Denham (Citation2010) and Elling et al. (Citation2014). By contrast, for age, Denham (Citation2010), Dóczi (Citation2012) and Elling et al. (Citation2014) all reported that sporting pride or national sporting pride was more elevated among older people. The higher levels of sportive nationalism found in our sample among respondents who participated in sport and physical activity supports previous nation-specific research by Elling et al. (Citation2014) and Haut et al. (Citation2016). The finding that happiness was not significantly associated with sportive nationalism reinforces Pawlowski et al.’s (Citation2014) research, which did not find support for the hypothesis that pride from international sporting success can contribute directly to subjective wellbeing. Because sportive nationalism was seen to be more volatile than other domains of national pride in our dataset, it is therefore worthwhile to look for associations between variations in sportive nationalism on a month-by-month basis and specific events that might influence its level, as well as the longevity of any increases or decreases in the measure.

Links between changes in sportive nationalism and specific events

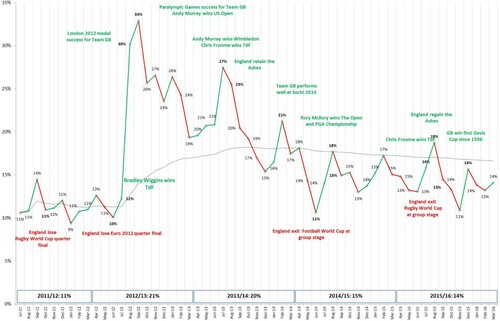

provides an analysis of the 57 monthly data points taken from five TPS waves and against these we have mapped significant sporting events and achievements of British athletes and teams to test whether variations in sportive nationalism might be linked to those specific sporting events or occurrences.

In , monthly increases in the sportive nationalism scores are highlighted by the green lines and decreases are denoted by the red lines. Also shown in is the moving average trend line (the black line), which is calculated by averaging the monthly scores. Selected British performances at some major sporting events are included as a narrative on the graph as plausible associations for the changes observed between the monthly scores. The most notable shift in occurred between July 2012 and August 2012, when the sportive nationalism score increased sharply from 12% to 30%. This increase coincided with Great Britain winning 65 medals (including 29 golds) and finishing third in the medals’ table at its home Olympic Games and corroborates previous research in the Netherlands which demonstrated an elevated level of sporting pride associated with the 2008 Olympic Games (Elling et al., Citation2014). The sportive nationalism score increased further to 33% in September 2012. Aside from any afterglow effect associated with Great Britain's Olympic success, it is plausible this additional three percentage points’ increase may be related to two other sporting achievements that occurred then. First, the country's performance at the 2012 Paralympic Games (34 gold medals, 120 total medals and third in the medals’ table), which were also held in London. Second, tennis player Andy Murray recorded his first Grand Slam victory at the 2012 US Open. Other notable monthly increases in the sportive nationalism score were seen to occur at the same time as British successes in other international sporting competitions including the Winter Olympic Games in 2014 (also aligned with Elling et al. (Citation2014)), the Tour de France in 2013 and 2015, Ashes cricket in 2015 (a series of Test matches contested between England and Australia), golf majors in 2014 and Davis Cup tennis in 2015. The events which tend to be associated with fluctuations in sportive nationalism are events that are of relatively long duration. Given that each data point relates to one month’s worth of surveying, it is perhaps the achievements at longer-lasting events that most stay in people’s consciousness.

In the same way that it is possible to associate ‘peaks’ in the trend line for sportive nationalism in with sporting successes, it is also possible to associate ‘dips’ with what might be perceived as sporting failures. For example, the noticeable dip in the sportive nationalism score in June 2014 coincided with England being eliminated from the FIFA World Cup at the group stage. Gassmann et al. (Citation2020) also reported a decline in national pride in Germany when the German football team failed to progress beyond the group stage of the FIFA World Cup in 2018. Similar dips in our study can also be seen in the case of England's exit from other major football (2012) and rugby (2011 and 2015) competitions. There are also dips for which there is no obvious explanation other than perhaps the reduced likelihood of selecting ‘British sporting achievements’ as a component of national pride in Great Britain once the afterglow of an earlier sporting achievement begins to wane. The finding that sportive nationalism appears to fall in response to perceived failure chimes with Dóczi (Citation2012, p. 165) who stated

The results show that for the majority of Hungarian society elite-sport success is important, however, identification decreases in cases of failures and scandals.

Conclusion

The key contribution to knowledge of this paper is the granularity provided by the 57 data points from TPS and their subsequent association with sporting performance in international competitions. By adopting this approach, we respond to the call of Storm and Jakobsen (Citation2020) for national studies, more data points and examination of smaller but culturally important events.

Building on the efforts of previous researchers who have attempted to examine the concept of pride associated with elite sport, we devised and tested three RQs. In response to RQ1, our study found limited support for policymakers’ belief in the existence of sportive nationalism in the UK, which was shown by only a small minority of the adult population and was typically lower than several other more stable factors such as the British countryside. For RQ2, we established that certain population segments were significantly more inclined to be sportive nationalists than others. The main finding with reference to RQ3 was that sportive nationalism in the UK can be sensitive to sporting performances as they occur. However, variations in sportive nationalism have a relatively short life span and are both positive and negative. It is also possible that changes in sportive nationalism could be unrelated to sport. For example, whilst the UK monarchy is generally thought of favourably, any change in the public’s perceptions, could reduce scores for this domain and thereby cause increases in other domains.

The 12 pride domains in the TPS employed in this research provide the largest selection of sources of national pride in the published data, exceeding the ten domains covered by the ISSP Research Group (Citation1998, Citation2012, Citation2015) and the seven used in the work of Meier and Mutz (Citation2016). That the TPS variables differ from the other surveys suggests that national pride is a multi-faceted construct that previous research, including the TPS, has not articulated fully. Furthermore, as some constructs of pride that were included in our study such as the British health service and the monarchy are not common to all nations, it is likely that different constructs of pride will be required in different countries to capture fully their cultural specificities.

If sporting achievement is but one of a range of factors that makes people proud of their country, it is difficult to see how an increase in sportive nationalism might impact positively overall subjective wellbeing measures such as happiness. Thus, in our sample, although sportive nationalism is the most volatile of the domains measured, its overall significance is relatively low. A temporary fluctuation in a national pride domain which is of relatively low overall importance can only have a modest impact on summary wellbeing measures, if indeed any. This conclusion challenges the UK Government’s position that the ‘clearest rationale for public investment in high performance sport is as a lever for national pride’ (Cabinet Office, Citation2002, p. 117). Such an unsubstantiated view is not confined to the UK Government, as Elling et al. (Citation2014) explain that the authorities in the Netherlands justify their investment in elite sport on the grounds that ‘elite sports events and national achievements should foster national pride, social cohesion and international prestige’ (p. 129).

Our study is based on cross-sectional data with each data point collected over one month. Most other studies that use more than one data point to create a time series (e.g. Elling et al., Citation2014; Meier & Mutz, Citation2016; Van Hilvoorde et al., Citation2010) also rely on cross-sectional data. Thus, variations in scores over time and attempts to match them to specific incidents are based on associations and not causes. The exception is the work of Leng et al. (Citation2014), who undertook a longitudinal study using matched pairs on a convenience sample of students. It is something of a limitation of our analysis to try an attach meaning to a data point that relates to a month's worth of activity to an event which will almost certainly be of less than one month in duration. Furthermore, with a variety of international sporting events taking place simultaneously, it is also difficult to associate, for example, success in one and failure in another with a change in sportive nationalism. To a certain extent, these constraints are less of an issue for mega events that take place over an extended period such as the FIFA World Cup and the Olympic Games. However, it should be noted that the level of granularity for time (one month) is relatively crude. This limitation points to two potential methodological improvements for research instruments designed to test the relationship between success in elite sport and national pride: first, even greater granularity in the time period under review, for example on the basis of weeks; and second, greater specificity in the questioning, for example: ‘To what extent does the performance of British athletes and/or teams at [a specified event] make you feel proud of Britain?’ Whilst previous research has focused on events such as the Olympic Games and major football tournaments, the data used in our study suggest that a wider range of events might influence sportive nationalism and that reductions in this specific domain of national pride may be associated with both perceived failure and a general waning effect. These are the original insights that represent the contribution of our study to the extant literature.

In conclusion, for Governments that attempt to justify investment in elite sport on the grounds of success generating national pride, the evidence from both the data in this study and from research conducted elsewhere is heavily nuanced. Any attempt to demonstrate the relationship between sporting performance and measures of sporting pride, will require far more refined approaches than have been used to date.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Cabinet Office. (2002). Game plan: A strategy for delivering Government’s sport and physical activity objectives.

- Coalter, F. (2013). There is loads of relationships here”: developing a programme theory for sport-for-change programmes. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 48(5), 594–612. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212446143

- DCMS. (2012). Taking Part 2011/12 Adult and Child Report. London: Department of Culture, Media and Sport.

- De Rycke, J., & De Bosscher, V. (2019). Mapping the potential societal impacts triggered by elite sport: A conceptual framework. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 11(3), 485–502. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2019.1581649

- Denham, B. E. (2010). Correlates of pride in the performance success of United States athletes competing on an international stage. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 45(4), 457–473. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210373540

- Dóczi, T. (2012). Gold fever(?): sport and national identity - the Hungarian case. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 47(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690210393828

- Elling, A., Van Hilvoorde, I., & Van Den Dool, R. (2014). Creating or awakening national pride through sporting success: A longitudinal study on macro effects in the Netherlands. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 49(2), 129–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212455961

- Evans, M., & Kelley, J. (2002). National pride in the developed world: Survey data from 24 nations. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 14(3), 303–338. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/14.3.303

- Frick, B., & Wicker, P. (2016). The trickle-down effect: How elite sporting success affects amateur participation in German football. Applied Economics Letters, 23(4), 259–263. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2015.1068916

- Gassmann, F., Haut, J., & Emrich, E. (2020). The effect of the 2014 and 2018 FIFA World Cup tournaments on German national pride. A natural experiment. Applied Economics Letters, 27(19), 1541–1545. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2019.1696448

- GB Sports Council. (1982). Sport in the community: The next ten years. Great Britain Sports Council.

- Grix, J., & Carmichael, F. (2012). Why do governments invest in elite sport? A Polemic. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 4(1), 73–90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2011.627358

- Hair, J., Black, W., & Babin, B. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hallmann, K., Breuer, C., & Kühnreich, B. (2013). Happiness, pride and elite sporting success: What population segments gain most from national athletic achievements? Sport Management Review, 16(2), 226–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2012.07.001

- Haut, J., Prohl, R., & Emrich, E. (2016). Nothing but medals? Attitudes towards the importance of Olympic success. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 51(3), 332–348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690214526400

- HM Government. (2015). Sporting future: A New strategy for an active nation.

- Houlihan, B. (1997). Sport, national identity, and public policy. Nations and Nationalism, 3(1), 113–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1354-5078.1997.00113.x

- ISSP Research Group. (1998). International Social Survey Programme: National Identity I - ISSP 1995. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA2880 Data file Version 1.0.0, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4232/1.2880

- ISSP Research Group. (2012). International Social Survey Programme: National Identity II - ISSP 2003. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA3910 Data file Version 2.1.0, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4232/1.11449

- ISSP Research Group. (2015). International Social Survey Programme: National Identity III - ISSP 2013. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5950 Data file Version 2.0.0, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4232/1.12312

- Kavetsos, G., & Szymanski, S. (2010). National well-being and international sports events. Journal of Economic Psychology, 31(2), 158–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2009.11.005

- Kersting, N. (2007). Sport and national identity: A comparison of the 2006 and 2010 FIFA World CupsTM. Politikon, 34(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02589340801962551

- Leng, H. K., Kuo, T.-Y., Baysa-Pee, G., & Tay, J. (2014). Make me proud! Singapore 2010 youth Olympic Games and its effect on national pride of young Singaporeans. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 49(6), 745–760. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690212469189

- Meier, H. E., & Mutz, M. (2016). Sport-related national pride in East and West Germany, 1992–2008: Persistent differences to trends toward convergence? SAGE Open, 6(3), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016665893

- Meier, H. E., & Mutz, M. (2018). Political regimes and sport-related national pride: A cross-national analysis. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 10(3), 525–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2018.1447498

- Mutz, M. (2018). Football-related patriotism in Germany and the 2016 UEFA EURO. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 48(2), 287–292. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-018-0490-7

- Pawlowski, T., Downward, P., & Rasciute, S. (2014). Does national pride from international sporting success contribute to well-being? An International Investigation. Sport Management Review, 17(1), 121–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.06.007

- Smith, T. W, & Seokho, K (2006). National pride in comparative perspective: 1995/96 and 2003/04. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 18(1), 127–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edk007

- Storm, R. K., & Jakobsen, T. G. (2020). National pride, sporting success and event hosting: An analysis of intangible effects related to major athletic tournaments. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(1), 163–178. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2019.1646303

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics. Allyn & Bacon.

- Tilley, J., & Heath, A. (2007). The decline of British pride. The British Journal of Sociology, 58(4), 661–678. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00170.x

- UK Statistics Authority. (2012). Assessment of compliance with the Code of Practice for Official Statistics: Statistics on Participation in Culture, Leisure and Sport. Assessment Report 190. London: UKSA.

- Van Hilvoorde, I., Elling, A., & Stokvis, R. (2010). How to influence national pride? The Olympic medal index as a unifying narrative. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 45(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690209356989

- Weed, M., Coren, E., Fiore, J., Wellard, I., Chatziefstathiou, D., Mansfield, L., & Dowse, S. (2015). The Olympic Games and raising sport participation: A systematic review of evidence and an interrogation of policy for a demonstration effect. European Sport Management Quarterly, 15(2), 195–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2014.998695

- Wicker, P., Prinz, J., & Von Hanau, T. (2012). Estimating the value of national sporting success. Sport Management Review, 15(2), 200–210. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2011.08.007