ABSTRACT

Research question: This paper presents a new comprehensive framework that brings together a wide range of themes and issues pertaining to the management of Olympic volunteering lacking in the literature. It helps answer the following research question: how and for whom volunteer programmes work, in what circumstances, to what effect and over what duration. The purpose of this study is to demonstrate the theoretical and practical value of combining the Volunteer Process Model (VPM) (Omoto & Snyder, 2002), Human Resource Management (HRM) Model (Cuskelly et al., 2006) and Legacy Cube (Preuss, 2007). This theoretical synergy helps unpack ‘what’ we study, while the premises of critical realist evaluation (Pawson, 2013) ‘Context + Mechanism = Outcome’ (CMO) aid in answering ‘why’ and ‘how’ we study it.

Research methods: The London 2012 Olympic Games volunteer (Games Maker or GM) programme was the primary case for this research. Data was gathered before, during and 14 months after the Games in the UK via a mixed methods approach. Survey data from volunteers was complemented with semi-structured interviews with volunteers and managers, the author’s participant observations and documentary analysis.

Results and findings: The proposed framework helped identify and evaluate the systems, mechanisms, and processes of developing and managing the GM programme. It became evident that unless key event stakeholders acknowledge the complex nature of Olympic volunteering and put adequate structures, resources and practices in place, the volunteer programmes are ineffective in managing volunteers and attaining a sustainable volunteering legacy.

Implications: This paper offers valuable insights into the organisation and management of Olympic volunteering to achieve various programme results. It answers a call for a holistic approach to the phenomenon under study and features new directions for continued academic research in this critical area.

Introduction

The risks associated with public investments in the Olympic Games (Games) have grown exponentially alongside expectations of the long-term benefits these multi-billion-dollar events ought to deliver. This is especially pivotal in volunteering as Olympic volunteers play a key role in staging the Games (Chanavat & Ferrand, Citation2010; Kemp, Citation2002). The argument though is that volunteers should be given opportunities to personally gain from their involvement, such as acquire new skills, competencies, and networks, boost a sense of fulfilment and achievement (Doherty, Citation2009; Downward & Ralston, Citation2013; Nedvetskaya et al., Citation2015; Wilson, Citation2000, Citation2012). Positive experiences may inspire further volunteering in and outside the sport event context (Auld et al., Citation2009; Parent & Smith-Swan, Citation2013; Ralston et al., Citation2005), thereby contributing to a lasting legacy and a stronger civil society. This can ultimately lead to enhanced quality of life and legacy creation, which is considered a primary purpose for staging the Games (Preuss, Citation2019). Nonetheless, published evidence shows that volunteer programmes often lack effective planning and management to achieve a volunteering legacy beyond the event (Nedvetskaya & Girginov, Citation2017). Negative volunteering experiences result in poor performance, demotivation, volunteer attrition and unwillingness to volunteer in the future (Elstad, Citation1996).

Despite acknowledged contributions of volunteers, relatively few studies have been concerned with the complex nature of volunteer behaviour in sport event settings (Dickson et al., Citation2013; Dickson et al., Citation2014; Farrel et al., Citation1998; Love et al., Citation2011). Little is known about the processes of volunteering and volunteer management practices (Bang & Chelladurai, Citation2009; Khoo & Engelhorn, Citation2011), particularly in the Olympic context (Chanavat & Ferrand, Citation2010; Giannoulakis et al., Citation2007). The consequences of Olympic volunteering are neither fully examined nor understood. More research is needed on volunteers’ characteristics, lived experiences, the specifics of event projects they help deliver, and the extent to which Olympic volunteering can enable a sustainable volunteering legacy (Brown & Massey, Citation2001; Clark, Citation2008; Hall, Citation2001; Smith & Fox, Citation2007; Wilks, Citation2016). These deficiencies can be attributed to scarce methodological diversity (Byers, Citation2009; Downward, Citation2005; Horne & Manzenreiter, Citation2006; Weed, Citation2005) when predominantly quantitative studies limit their depth (Hoye & Cuskelly, Citation2009; Wicker & Hallmann, Citation2013) and what they can reveal over time (Green & Chalip, Citation2004). The search for new insights is encouraged via holistic interdisciplinary approaches (Doherty, Citation2013; Ferrand & Skirstad, Citation2017), echoing the urge for critical realists to engage in more in-depth investigations (Byers, Citation2013; Byers & Thurston, Citation2011).

Aimed to fill these gaps, the present study develops a new conceptual framework that helps identify and analyse multiple dimensions of volunteering in their interplay and within the context of the London 2012 Olympic Games (London 2012), where volunteering was manifested through a deliberately designed volunteer (GM) programme. This framework serves as a tool to help answer the research question: how and for whom did the GM programme work, in what circumstances, to what effect and over what duration? The paper starts with an overview of the existing frameworks and their constraints. The ‘hybrid map’ of volunteering by Hustinx et al. (Citation2010) is utilised to explore ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ volunteering is studied. Different elements of the proposed framework and the employed methodology are presented and justified next. The application section demonstrates how Pawson’s (Citation2013) premises of critical realist evaluation (CMOs) converge with three domains of reality in Bhaskar’s (Citation1975, Citation2008) critical realism and various aspects of the new framework. Reported findings highlight the value of the framework, and lessons learned for multiple stakeholders. The paper concludes with the study implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Literature review

‘What’ we study

Volunteering has various meanings in different contexts, embraces a diverse range of activities and spans multiple organisations and sectors of society (Hustinx et al., Citation2010; Lukka & Ellis, Citation2001; Wilson, Citation2000). According to Cnaan et al. (Citation1996), there are four key dimensions of volunteering: ‘free choice’, ‘remuneration’, ‘structure’, and ‘intended beneficiaries’. However, these components do not capture the whole spectrum of volunteering. The existing typology is missing the dimension of ‘time’ (regularity) and the ‘type’ of volunteering activities. Often volunteering at ‘sport events’ is treated no differently from ‘sport’ volunteering, suggesting it is the activity involved in the sport provision. Still, the context and episodic nature of events add new elements to this kind of volunteering, commitment, and accumulated benefits. Most sport event volunteers are ‘hired’ for a fixed term determined by the Games lifespan, which can be viewed as project-based leisure that is rather complex but short and infrequent in nature (Stebbins & Graham, Citation2004).

‘Why’ and ‘How’ we study

Hustinx et al. (Citation2010) distinguished between three major ‘theories’, each encompassing different approaches to study volunteering: ‘theory as explanation’ that sheds light on who volunteers are, and why they volunteer (personal motivations, benefits); ‘theory as a narrative’ that focusses on how people volunteer (styles and processes), the context of volunteering (volunteer management) and how social, institutional and bibliographical changes influence volunteering; and ‘theory as enlightenment’ that critically questions dominant assumptions of volunteering (negative consequences, unmet expectations). Although contemporary research probes diverse aspects of volunteering, the interactions between them are insufficiently explored (Hustinx et al., Citation2010; Wicker & Hallmann, Citation2013).

Hustinx & Lammertyn (Citation2003) developed a framework of Collective and Reflexive Styles of Volunteering (CRSV model), which allows for identification of distinct styles of volunteering along the continuum: collective (traditional, old) and reflexive (individualistic, new). Their research shows that volunteering is a highly specialised and self-organised activity by ‘clever volunteers’ who actively pursue personal interests. This individualistic style is common to sport event volunteers, yet it does not fully account for the dynamic nature of volunteering experiences inherent in the sport event sector. Haski-Leventhal & Bargal’s (Citation2008) Volunteer Stages and Transitions Model (VSTM model) seems to fill this gap via exploring five stages of organisational socialisation ranging from ‘nominee’ to ‘retiring’, the transitions between them and turnover. This model differentiates motivation, satisfaction, costs, and rewards according to the stages of volunteering to explore what causes the transition. Yet, it can be challenged by the assumption that socialisation does not always take place in the same order, and volunteers may occupy several stages simultaneously (Lois, Citation1999). Although relevant for non-profit and voluntary sectors, this model cannot be fully applied to Olympic Games Organising Committees (OCOGs) with a short business cycle and a project-based nature of volunteer assignments. Therefore, when or if the organisational socialisation of volunteers occurs in this context, it is very short-lived and unsustainable.

A call for a holistic approach

Various scholars advocated for a holistic approach to sport event volunteering, accounting for many themes and issues from a multi-stakeholder perspective (Baum & Lockstone, Citation2007; Ferrand & Skirstad, Citation2017; Hamm-Kerwin et al., Citation2009). Wicker & Hallmann (Citation2013) were the first to propose a framework that brings together individual and institutional levels of analysis to explain volunteers’ decision-making process impacted by organisational characteristics. Although beneficial for clarifying engagement in sport volunteering, this framework omits a wider context and a full cycle of volunteering and management and, therefore, is limited in its utility. Also, its focus on quantitative methods does not allow for the in-depth exploration of factors to be captured through qualitative investigations.

To maximise the explanatory potential and further recognise the complex nature of volunteering, this study approaches it through the lens of a volunteering legacy. Limited evidence in this area is highlighted in the literature (Cuskelly et al., Citation2004; MacAloon, Citation2000; Preuss, Citation2019). Due to the nebulous nature of the social aspects of volunteering, it proves difficult to identify, record, measure, and evaluate a volunteering legacy, yet pivotal in light of the IOC rhetoric to utilise legacy as ‘the best argument with which to illustrate the lasting benefits … derived from the Olympic Games’ (Preuss, Citation2019, p. 103). Although the concept of legacy has become very popular (Leopkey & Parent, Citation2012), it still forms ‘part of the ‘known unknowns’ of sports mega-events’ (Horne Citation2007, p. 86). Critical analysis of a volunteering legacy and how the Games can benefit local people is important to counterbalance the optimistic, even patriotic discourse that justifies public investments into the event hosting (Silvestre, Citation2009).

Theoretical background

Due to the limited conceptual understanding of the phenomenon under study, this research proposes a new ‘all-rounded’ interdisciplinary approach to Olympic volunteering, albeit drawing insights from traditional settings ‘as no one has all the answers’ (Doherty, Citation2013, p. 1).

Volunteer Process Model

At the core of the new framework is the VPM model by Omoto & Snyder (Citation2002). Volunteering in this model is approached as a dynamic process (‘life cycle’) that unfolds over time through three interactive stages (Antecedents, Experiences and Consequences) on multiple levels of analysis (Individual, Group, Organisational, and Societal). This conceptualisation helps elucidate numerous dimensions of volunteering, thereby providing an integrated approach for more in-depth analysis and evaluation. The VPM model reflects both the strategic and operational timeline of the Games and multiple stakeholders involved.

Closer reflection suggests that this model brings together the ‘what’, ‘why’ and ‘how’ of volunteering. The Individual level focusses on personal backgrounds, psychological factors, and activities of volunteers, helping to explore ‘who’ volunteers are and ‘why’ they volunteer (Antecedents stage), the nature, context and processes of their involvement (Experiences stage), and the outcomes of volunteering (Consequences stage). The Group level incorporates volunteering dynamics in the form of social interactions and group identification. Further levels account for the ingrained nature of Olympic volunteering within the institutional and cultural environments. The Organisational level is concerned with the internal culture, structures, regulations, and operations that differ for each stage (detailed in HRM model). The Societal level deals with the external context within which volunteering takes place and the benefits volunteering offers to society (detailed in Legacy Cube). As opposed to other studies that focus on one or two levels separately (Ferrand & Skirstad, Citation2017; Shipway et al, Citation2020), the proposed framework targets the relationships among all four levels in VPM model.

Human Resource Management model

The HRM model by Cuskelly et al. (Citation2006) is an indispensable part of the Organisational level of analysis in the VPM model. Given that volunteers play a significant role in the Games operations, it is essential to understand how and when they are ‘acquired’ and ‘maintained’, and under what circumstances (Context). This involves important managerial decisions throughout the Games lifespan (reflected in VPM stages) and the impact these decisions have on the Processes and Outcomes of the volunteer programme. Therefore, the HRM model represents a systematic approach to volunteer management through the practice of identifying and hiring the right people at the right time and place, ensuring they are well oriented, trained, and adequately rewarded for their performance. Strategic planning is developed at the Antecedents stage. Activation of various Mechanisms (e.g. recruitment, selection, training, placements and management) takes place at the Experiences stage. The Consequences stage is focussed largely on final recognition, evaluation of volunteer services cross-checked against the overall achievement of the organisational goals. This suggests an ongoing ‘loop’ of interdependent organisational practices that directly affect how the volunteer programme works and to what effect.

Legacy Cube model

According to the IOC sustainability approach, legacy ‘encompasses all the tangible and intangible long-term benefits for people, cities/territories and sport arising from the staging of an event’ (IOC, Citation2018, p. 65). The Legacy Cube by Preuss (Citation2007) is arguably the most developed scholarly attempt so far to conceptualise multiple Olympic legacies and their value to society (Nedvetskaya & Girginov, Citation2017). It helps place volunteer programmes within legacy rhetoric to identify and explore multiple programmes’ systems and structures that either assist or inhibit the legacy creation and delivery within the context of the host destination. As argued by Preuss (Citation2015, Citation2019), the Olympic Games always cause changes of (in)tangible event structures and, importantly, result in positive or negative, planned or unplanned consequences to be analysed from a multi-stakeholder perspective. These event structures include ‘infrastructure’, ‘policy’, ‘knowledge’, ‘networks’, and ‘emotions’. The volunteer programme, therefore, is regarded as a structural change triggered by the Games, where infrastructure and policy are set up in the form of a new event organisation (e.g. OCOG) with its laws and regulations to plan for and manage volunteers and a volunteering legacy. Volunteers and managers engaged in the programme are given opportunities to build the knowledge base through gaining new and/or applying existing skills and competencies, establishing new contacts and enhancing personal and professional networks. As a result, they are subject to various experiences and emotions that cumulatively prompt changing behaviour patterns that affect the outcomes. Following a ‘forward-thinking’ rationale (Girginov, Citation2012), the Legacy Cube allows for determining various legacy manifestations across different levels and stages in VPM and HRM models and throughout the entire Games lifespan.

Bringing three theories together

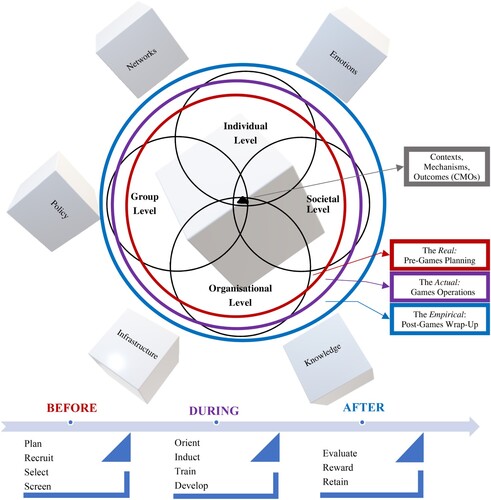

The theoretical synergy utilised in this study guided the analysis of Olympic volunteering through the dynamic relationships among individual volunteers (GMs), the organisation (the London 2012 Organising Committee – LOCOG), volunteer managers and the UK society at large. Overall, this holistic approach (see ) helps identify structures and mechanisms employed by multiple event stakeholders that either facilitated or constrained various processes and outcomes in the context of London 2012. The elements that constitute different levels and stages of the volunteer process (VPM model) were seen as unfolding via the volunteering ‘life cycle’. Volunteers’ characteristics, motivations, expectations, efficacy, commitment, and acquired benefits were analysed on a personal level throughout the Games timeline. These processes took place in the context of interactions among volunteers, managers and other stakeholders and were subject to various LOCOG policies and practices related to ‘acquisition’ and ‘maintenance’ of volunteers (HRM model). This resulted in positive and negative, planned and unplanned outcomes caused by tangible and intangible structural changes analysed at a specific time and geographical space (Legacy Cube).

Figure 1. Blending Three Theories: The Legacy Cube and VPM & HRM models. (Adapted from Cuskelly et al. Citation2006; Omoto & Snyder, Citation2002; Preuss, Citation2007).

Research philosophy and strategy

While a newly developed conceptual framework is set to help clarify the complex nature (‘what’) of Olympic volunteering (ontology), the premises of critical realist evaluation by Pawson (Citation2013) help answer ‘why’ and ‘how’ we study this phenomenon (epistemology). It is based on the tradition of Bhaskar’s (Citation1975, Citation2008) critical realism where the world consists of three distinct domains of Reality: the Real, the Actual and the Empirical. The Real domain is where various human, material, institutional and cultural structures and their causal powers (Mechanisms) reside. The Actual domain is where causes and powers in the Real domain are activated by certain generative Mechanisms to make things happen or change. The Empirical domain is where the Outcomes of the interplay of the Actual and the Real and the associated changes can be observed. Based on these principles, Pawson (Citation2013) applied contextual thinking to programmes that are approached as sophisticated social interactions set amidst a complex social reality to generate Outcomes. In this view, the programme works because of the action of an underlying Mechanism (M) activated in a particular Context (C) to bring about change or Outcome (O). This implies the causal and conditional nature of the relationship between CMOs and helps address for whom and in what circumstances a programme works. In Pawson’s (Citation2013) thinking, only the right processes that operate in the right conditions enable the achievement of desired programme outcomes. The argument is that the programme may work better for certain types of subjects but not for others. Certain contexts are supportive of the programme theory and others are not, and certain institutional arrangements may be better at delivering specific outcomes. Mechanisms are various ideas and theories within the programme that explain the logic of interventions as they create different resources that trigger certain reactions among the participants. In the realist view, ‘it is not programmes that work but the resources they offer to enable their subjects to make them work’ (Pawson & Tilley, Citation2004, p. 6). Due to variations in contexts and mechanisms thereby activated, programmes have mixed (un)intended outcomes that take different forms and result in uneven patterns of failures and successes (detailed in the Legacy Cube).

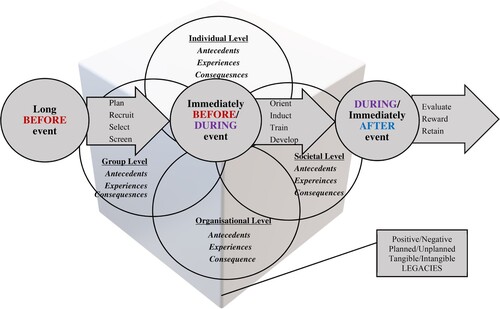

In theory, Pawson’s (Citation2013) critical realist evaluation represents a level of abstraction not tied to any specific setting. Therefore, it has been applied to the context of Olympic volunteering where the latter is understood as a result of inter-relationships among various structures, their causal powers (Mechanisms), contexts within which they operate, and outcomes achieved (see ). This study employed an embedded single-case design (Yin, Citation2014) where the case was the London 2012 GM programme, and its different aspects were the units of analysis. The GM programme’s elements became the mechanisms designed and activated in particular conditions to elicit certain changes. The London 2012 volunteering and associated management practices were approached as a complex interplay of personal, group and organisational attributes and social interactions that took place before, during and after the Games (the domains of Reality) and resulted in structural changes with short- and longer-term consequences.

Figure 2. Convergence of CMOs, Three Domains of Reality and Multiple Aspects of Volunteering. (Adapted from Bhaskar Citation1975, 2008; Pawson, Citation2013).

Methods and sampling

Data for this research was gathered before, during and after the Games via mixed methods, which allowed for engaging in open and multi-sourced research practices (Iosifides, Citation2011). The insights were cross-checked via the triangulation process to increase the validity and reliability of research findings. Quantitative evidence included a pre-Games online survey of 151 volunteers with 71 full responses. The aim was to research volunteers’ motivations, barriers to volunteering, previous volunteering experiences, opinions about training and volunteer management as well as to recruit volunteers for the follow-up interviews. Qualitative evidence incorporated 20 face-to-face semi-structured interviews in total, with 16 volunteers and four managers. Volunteers from different backgrounds, ages, genders, volunteering roles and functional areas were interviewed to understand various patterns of individual experiences and attitudes, thereby uncovering how the programme was received from the ‘bottom up’. Thus, having respondents with contrasting profiles and experiences allowed for comparing their motivations and derived benefits at various stages of the London 2012 event life cycle (see ). The same volunteers were interviewed three times to track any changes in their lives and attitudes: pre-Games in June 2012, immediately post-Games in September 2012 and a year later in September 2013.

Table 1. Interviewee’s profile (volunteers).

In-depth interviews with managers took place in August-September 2012. The purposive sampling technique allowed data gathering from key informants about their decisions involved in the GM programme planning and delivery. Among interviewees were: two LOCOG Deputy Venue Managers (VM), one LOCOG HR Manager, and the Chair of the London 2012 Volunteering Strategy Group (L2012 VSG). The research participants were recruited by the researcher before the Games by contacting them personally during the training sessions and pre-Games events. The initial list of topics was developed from the literature, theory and the research aim/questions. Then, appropriate questions and their sequence were devised to target the issues under investigation. For example, volunteers were asked: ‘What was your training experience?’ or ‘How have you used your London 2012 experience post-Games?’ Managers were asked questions about their involvement in planning and delivery of the GM programme: ‘What was your role in the GM Programme?’ or ‘Could you please describe the process of volunteer selection?’ ‘Funnelling’ technique (Smith & Osborne, Citation2008) was used to move the interview from general to more specific issues, encouraging the participants to express their views before asking them specific details. The first draft of the interview protocol was peer-reviewed and piloted via Skype to allow for appropriate modifications. Interviews equated with 43:25 h of taped conversations that were transcribed verbatim, producing 763 pages of rich data for analysis, which yielded enough corroborating evidence to suggest that saturation was reached within this number of participants. All interviews were analysed thematically through generating codes, reviewing and clustering themes, and translating them into a narrative account (Braun & Clarke, Citation2012). Both deductive and inductive approaches were in constant interplay to produce this study. The overarching themes and the analysis itself were theory-driven while coding happened mainly from the raw material and based on participants’ personal stories, reflecting their language (DeWalt & DeWalt, Citation2011). For example, ‘Motivations’ became a code with multiple sub-codes, such as ‘prestige and high profile of the event’ and ‘employment opportunities’ (theory), ‘helping others’ and ‘get a new skills’ (in participants’ own words). N-Vivo software programme was used to assist in organising and managing data.

Primary data was supplemented with field notes (a self-recorded diary) from participant observations carried out by the author as Selection Event Volunteer (SEV) and Games Maker (GM). Participant observation was difficult to conduct as the researcher had little control of the situation (DeWalt & DeWalt, Citation2011). The issue of revealing the researcher’s identity was particularly challenging. The decision was made to be explicit during informal conversations, but not while volunteering or observing others, as this would potentially restrict gaining authentic information and put a barrier between the researcher and the researched, thereby undermining data gathering in the natural setting. This balance allowed for not jeopardising the research while still accessing activities and informants, building rapport with them, and obtaining sufficient data. Importantly, having primary access to London 2012 through volunteering became the main reason to choose this case for the subsequent research and analysis. Indeed, ‘being there’ allowed the researcher to immerse in London 2012 subculture and the ‘world’ of those studied. This provided new insights into the context, behaviour, and meanings of events and experiences, thereby increasing the study validity and enhancing the quality of data obtained. This study strictly adhered to institutional ethical guidelines on conducting research and was granted full approval ahead of data collection.

Secondary data in the form of scholarly literature, industry reports and LOCOG documents provided evidence to corroborate or refute primary data (Yanow, Citation2007). The examples include the London 2012 Volunteering Strategy (VSG, Citation2006), government reports published by the Department of Digital, Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS Citation2007; Citation2008; Citation2010; Citation2011; Citation2012) and by LOCOG (LOCOG, Citation2013). Documents focussed on the GM programme’s rules, procedures and protocols became available to the researcher exclusively through volunteering: ‘LOCOG Volunteer Policy Games Time’ (LOCOG, Citation2012a), ‘My Games Maker Pocket Guide’ (LOCOG, Citation2012b), ‘My Games Maker Workbook’ (LOCOG, Citation2012c), ‘My Games Maker Training CD’ (LOCOG, Citation2012d).

Framework development

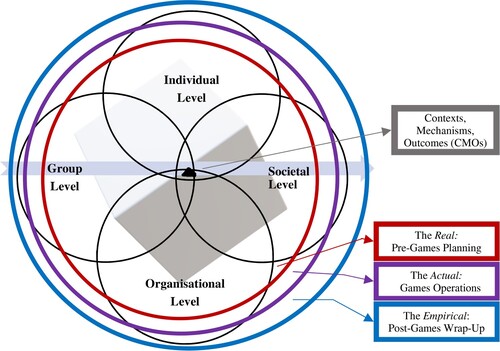

The following discussion illustrates how the premises of critical realist evaluation and three domains of reality correspond to various aspects of the VPM, HRM and Legacy Cube models, suggesting a sophisticated approach to analysis and evaluation of Olympic volunteering (see ). Critically, this framework allows for identifying the processes that affect five structures related to volunteering: infrastructure, policy, knowledge, networks, and emotions; how they change over time, and what role they play in the legacy creation.

Table 2. New multi-dimensional framework applied to the context of the London 2012 Olympic Games.

Real Domain

This domain relates to the pre-Games ‘strategic planning’ phase, which corresponds to the Antecedents stage in the VPM model and ‘acquiring’ resources (planning) in the HRM model (, the Real), which took place almost a decade before the Games. The analysis of various Games structures (stakeholders) on the Societal level is crucial in identifying who had the ‘powers’ (reasonings) to shape a volunteering legacy and how they affected the origins and nature of the Volunteering Strategy and the associated GM programme. LOCOG as a newly set up organisation (Organisational level) became responsible for building the volunteering infrastructure. Hence, the examination of LOCOG’s initial commitments is important to understanding the subsequent processes of volunteer management and outcomes. In turn, volunteers (Individual level) also had ‘causal powers’ that affected their engagement, experiences and benefits derived from volunteering. Therefore, the analysis on this level helped find out why volunteers wished to get involved in the GM programme.

Societal level

London 2012 took place in the context of renewed IOC rhetoric about the importance of strategic legacy planning to enable a positive sustainable development of the host destination, where the local priorities prevail (Coakley & Souza, Citation2013; Preuss, Citation2015; Vanwynsberghe, Citation2015). To justify £9.3 billion in public sector investments, the long-term value of London 2012 related changes became an ultimate priority (Nedvetskaya & Girginov, Citation2017). Therefore, the overarching vision for London 2012 was to host: ‘inspirational, safe, and inclusive Olympic Games … and leave a sustainable legacy for London and the UK’ (ESRC, Citation2010, p. 17) via maximising social and economic benefits. One of the legacy promises was to inspire a new generation of young people to take part in local volunteering. To deliver on this priority, over 100 stakeholders across different sectors of society formed the Volunteering Strategy Group (VSG, Citation2006) responsible for translating their reasonings (‘causal powers’) into developing the London 2012 Volunteering Strategy (‘policy’) that aimed at (a) having an excellent volunteer programme to run the successful Olympic Games (‘infrastructure’), (b) maximising the benefits of volunteering via skills development, training, and qualifications to address long-term unemployment and low skill levels in the UK (‘knowledge’ and ‘networks’), and (c) generating a sustainable volunteering legacy via transforming and strengthening the culture and spirit of volunteering across the UK (‘infrastructure’, ‘emotions’). Emphasis was placed on the principles of Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion via providing equal opportunities for volunteering to be achieved through the following mechanisms: a fully devolved to nations and regions franchise model of a ‘UK-Wide’ recruitment campaign; and a ‘homestay programme’ to enable out-of-London volunteers to have temporary Games-time accommodation (VSG, Citation2006).

Organisational level

LOCOG became legally responsible for the promises outlined in the Volunteering Strategy. The priority was to organise the best Games ever utilising the enthusiasm generated by the Games as a catalyst to inspire volunteers (VSG, Citation2006). The immediate plan was to recruit 70,000 volunteers able to commit at least 10 days during the Games to perform 3,500 roles and act as Olympic ambassadors. In exchange, LOCOG promised to provide volunteers with first-class training and support, various rewards, such as social events, certificates, and formal accreditation. These mechanisms were underpinned by a detailed plan of training requirements, job titles, rotas and rosters, meals and uniforms as well as a contingency plan of 20% applicants on reserve (VSG, Citation2006). These elements were considered essential to the success of the GM programme.

Individual level

Based on this study, volunteers had various pre-Games motivations and expectations. Young and inexperienced volunteers had few specific expectations, whereas mature volunteers were clear about the roles they wanted and the ‘right way’ they should be treated and supported. Contrasting ‘altruistic’ versus ‘egoistic’ motives were significant and varied by demographics and prior experiences. Older people wished to contribute to their community: ‘I’ve had a very good life; society has given me a lot. I want to give something back’ (retired L2012 volunteer). They also viewed volunteering as a meaningful alternative to work and an opportunity to put their existing skills and knowledge to good use. Young and unemployed volunteers, however, aimed to increase their employability via learning new or upgrading skills: ‘With volunteering, you’re exposed to the public … When you deal with a difficult case with good resolution … you can become a team leader’ (unemployed L2012 volunteer). Meeting new people, making friends and expanding networks (‘solidarity’ motives) were equally valuable for all volunteer groups.

Despite age and past experiences, all volunteers looked forward to being ‘behind the scenes’ and ‘part of a global event’. Among the emotional triggers were the ‘Olympic phenomenon’, ‘a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity’, ‘celebratory atmosphere’, ‘insider’ feelings, and ‘prestige’ of the event: ‘I was thrilled … it is a worldwide event … one of the greatest shows on Earth!’ (L2012 volunteer). For some participants, these ‘Olympic’ related motives became a dominant factor inspiring volunteering for the first time or revisiting volunteering experiences: ‘People are involved … because of the profile of the Olympic Games’ (first-time L2012 volunteer). This finding further strengthens the proposition that the motivational aspect of Olympic volunteers is somewhat different from other contexts (Dickson et al., Citation2013; Giannoulakis et al., Citation2007).

Actual domain

This domain relates to the ‘programme operations’ phase, which corresponds to the Experiences stage in the VPM model and ‘acquiring’ and ‘maintaining’ resources in the HRM model (, the Actual). These experiences are patterned in sequences of events that are understood through the activation of various mechanisms in the form of volunteer management practices on the Organisational level that triggered associated responses of volunteers on the Group and Individual levels. Particular attention is given to the dynamics of social interactions that affected the experiences, and the public perceptions of volunteers along with the overall Games-time atmosphere (Societal level).

Organisational level

Once the strategic planning was completed, LOCOG officially launched a volunteer recruitment campaign. Among the mechanisms at this stage were volunteer applications, selection, training and deployment (HRM model) manifested through the guidelines, culture and artefacts presenting the immediate context that shaped various management practices, volunteering experiences and programme outcomes.

Due to the scale and nature of the Games, LOCOG created standard procedures that often placed volunteer management in conflict with the initial legacy plans. Ultimately, LOCOG utilised a centrally controlled recruitment scheme to meet the organisational targets and avoid complexities involved in a fully devolved model. Temporary selection centres were established in nine UK regions to interview out-of-London volunteers (Nedvetskaya et al., Citation2015). As evidenced from conversations with volunteers, managers, and participant observations, short 20-minute interviews with 100,000 potential Games Makers were conducted by 2,000 SEVs, mainly students with limited previous interviewing skills or experience. Yet, LOCOG heavily relied on their judgement and ‘common sense’: ‘We didn’t have time to ask for 70,000 references … we could only know based on the answers that were given in the interview … and the opinion of the person interviewing’ (LOCOG HR Manager). Therefore, context and mechanisms in place influenced the quality and outcomes of the selection process. Volunteers did not have a say in their final deployment, despite the preferred functional areas they ‘ticked’ on the application form. Moreover, LOCOG reserved the right to change offers made of roles, functional areas, dates, and times of shifts (LOCOG, Citation2012a).

Every aspect of volunteers’ service was regulated by the rules outlined in various official booklets (LOCOG, Citation2012b, Citation2012c, Citation2012d) and further inculcated by mandatory training and daily supervision. All volunteers had to be integrated into ‘One Team’ and learn how to carry out their roles safely and confidently (Nedvetskaya et al., Citation2015; VSG, Citation2006). LOCOG rules and procedures had to be applied consistently across all functional areas and venues, but they varied by the management style, the number of volunteers in a team, and venue operations. As evidenced through GM participant observations, managers had to strike a balance between the demands of the Games and the needs of volunteers. A formal and task-driven approach had to be combined with a supportive style to sustain enthusiasm, productivity, and a healthy team atmosphere. This was reflected in the job design and flexible rotations that affected volunteers’ performance and satisfaction: ‘There are good jobs and bad jobs, you've got to mix it, so the volunteers aren't all doing the rotten jobs … [but] go around and swap’ (L2012 volunteer). Among other mechanisms applied were feedback, acknowledgements, and rewards. The frequency and quality of briefings and debriefings impacted the extent to which volunteers felt valued and encouraged, and managers were equipped with first-hand information to manage any inefficiencies. Keeping team spirit high was a critical management task: ‘I think we were good at trying to make everyone feel special and proud … some of the things volunteers were doing were really pretty boring … but if they know their work is being recognised … they just act as well as possible’ (LOCOG Deputy VM). Yet, interviews with volunteers suggest that volunteer management varied across different venues and teams.

Individual and group levels

Evidence shows that volunteers had mixed pre-Games and Games-time experiences. Some interviewees criticised a lack of proper mentoring and support mechanisms employed by LOCOG managers, which resulted in unbalanced rosters and workload, poor rotation, inadequate rest and food on shifts. Volunteers also noted a lack of specifics about volunteer jobs, which was at odds with the need to provide volunteers with resources to perform at their best: ‘The most important thing is making sure volunteers are equipped with the skills and knowledge … to help deliver the Games, and if they didn’t know what they were doing, they weren’t going to be happy’ (LOCOG deputy VM). The training focussed on generic communication, team building, and Games/sport awareness skills that are important but not always sufficient to perform Games-time roles. Therefore, most learning took place on shifts, making volunteers ‘experiential learners’ (Kemp, Citation2002) who had to apply or transform their existing knowledge to the realities of the Games.

The level of responsibility volunteers had seemed to impact what they learned and how they worked, which influenced their commitment and satisfaction. Volunteers with ‘menial’ and ‘back-of-house’ jobs reported limited opportunities for interactions, felt unhappy and under-utilised: ‘I was hoping to get something better [than being a steward] because that was … terrible … It’s difficult to make a role efficient if it’s letting people in and out of the door’ (L2012 volunteer). On the contrary, properly ‘matched’ volunteers were able to learn, build meaningful connections, and fully contribute to the Games, which kept them motivated despite the long shifts and stressful jobs. Mature volunteers readily mentored newcomers, which helped with building team spirit. The peer support proved to be uplifting: ‘[After] the briefing … one of the volunteers … gave me a box of Quality Street chocolates … from the team … ‘We think you’re doing a great job, keep going!’ I couldn’t speak. I welled up!’ (L2012 volunteer). Consistent with findings reported elsewhere (e.g. Galindo-Kuhn & Guzley, Citation2001), the ongoing support received from the managers further contributed to volunteers’ satisfaction: ‘If someone made a mistake, managers were there to transmit confidence, make them calm again … they remained very positive … thankful for what you were doing’ (L2012 volunteer).

Societal level

The ‘Olympic phenomenon’ seemed to not only attract volunteers at the outset but also became a strong incentive to persevere to the finish line: ‘If I don’t see it through now, I will regret it’ (L2012 volunteer). The celebratory Games-time atmosphere triggered the emotional highs and adrenaline rushes that offset negative feelings and inconveniences. Interviewed volunteers enjoyed being ‘inside the Games’, which continued to be a source of satisfaction. Positive public perceptions and acknowledgement of volunteers’ exceptional contributions during the Games further boosted volunteers’ pride, self-confidence, and reinforced their affiliation with ‘One Team’ contributing to the Games’ success. The traditional barriers to interaction among strangers seemed to be considerably lower during the Games: ‘I’ve met … people of other nationalities … [they] were open and friendly … people became sociable because [the Olympics] was the in-thing!’ (L2012 volunteer). The Games contributed to strengthening the social fabric and creating a sense of ‘global community’, although there is no evidence that this continued beyond the event.

Empirical domain

This domain relates to the post-Games ‘programme wrap-up’ phase that corresponds to the Consequences stage in the VPM model, where the outcomes of various mechanisms’ activation and their inter-dependence can be observed on different levels of analysis (, the Empirical). The GM programme (Organisational level) with its successes and failures is assessed against the initial targets set out in the Volunteering Strategy. The Individual level is focussed on who ultimately volunteered for London 2012 and what they gained or lost because of their participation. The Societal level is concerned with the extent to which a longer-term volunteering legacy was achieved and to what effect.

Organisational level

Published evidence confirms that the London 2012 Games were over-subscribed with experienced and new volunteers (House of Lords, Citation2013; Nedvetskaya et al., Citation2015; Nichols & Ralston, Citation2014). LOCOG was successful in the initial target to recruit 70,000 volunteers with nearly 250,000 applicants, and 40% first-time volunteers (DCMS, Citation2012). However, utilised mechanisms uncovered a mismatch between the initial plans and the outcomes achieved. Namely, volunteers were approached as a factor of service delivery and the costs to the organisation rather than investment in human capital development (Chelladurai & Madella, Citation2006) and a longer-term legacy.

For example, the decision to apply a centrally controlled recruitment scheme along with a lack of further support violated the promises to build on the existing volunteer ‘infrastructure’ in the regions, deepen engagement and widen access to volunteering. No policy in place to reimburse accommodation and out-of-city travel expenses was a breach of Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion principles. A ‘homestay programme’ did not materialise as a way in which ‘the costs could have been reduced significantly for people coming from other parts of the country’ (Chair of L2012 VSG). As mentioned by LOCOG Deputy VM, ‘We could do without … that sort of outreach exercise … which is a little bit expensive … and by virtue of how the Games went, we did have a great volunteer workforce’. This suggests that LOCOG exploited the ‘Olympic phenomenon’ that ultimately furnished oversubscription but did not allocate additional resources to fulfil legacy promises. Furthermore, they were not always effective in supporting volunteers in building required skills and knowledge, which would have enabled a better-equipped volunteering infrastructure (VSG, Citation2006).

Individual level

Evidence from this study further showed how individual and organisational factors combined affected the extent to which volunteers benefited from their GM experience. Volunteers’ status and personal attributes seemed to predetermine, albeit not always intentionally, who were assigned volunteering roles. The profile of surveyed volunteers revealed that the majority were women, over 45 years old, well-qualified with a degree, either employed or retired with savings, predominantly white British citizens, with one-third of a sample having an annual income of over £30,000. Similar findings were reported elsewhere (e.g. Dickson & Benson, Citation2013; Lukka & Ellis, Citation2001), which conforms to the ‘dominant status model’ (Smith, Citation1994) in which people with higher educational and socio-economic background are more likely to volunteer, further excluding people from other walks of life (Zhuang & Girginov, Citation2012). This outcome was subject to LOCOG’s policy of limited financial support provided to volunteers, which discriminated between ‘the haves’ and ‘the have-nots’ and undermined the principles laid out in the Volunteering Strategy (VSG, Citation2006): ‘The only people … who could come … were people who could afford to do so … it was going to be limiting; inevitably it enabled more middle-class people to [volunteer] than others’ (Chair of L2012 VSG).

Despite good quality volunteer management being essential to positive and worthwhile volunteer experiences (VSG, Citation2006), it can be argued that volunteers were approached as a replaceable resource used to achieve organisational goals. Identified mismanagement and inefficiencies along with high costs and time commitments led to volunteer dissatisfaction and attrition: ‘I hope it’s a great success … but I’m not sorry that I turned it down because I’m not happy with the organisation’ (dropped out volunteer). The remaining volunteers not happy with their Games-time experiences reconsidered their future involvement, which was particularly true for experienced volunteers: ‘I wouldn’t want to do that again … the Olympics is the pinnacle … I should have followed my instinct and been more assertive about the roles I wanted and didn’t want … to feel like I’m doing something useful’ (L2012 volunteer). This negative outcome was not necessarily pre-planned or intended by the organisers. Yet, it greatly limited the ability of the GM programme to facilitate post-Games volunteering. On the other hand, positive experiences certainly encouraged volunteering post-event. New and young volunteers reported an increase in personal development and networks: ‘Olympic Games … exceeded my expectations! I learned how to work with people with different backgrounds and (dis)abilities … became braver and more independent … good experience encourages me to volunteer in the future’ (L2012 volunteer). Older and experienced volunteers echoed: ‘Now when it’s all over I have lovely memories of a unique event and look forward to doing more sport volunteering locally’ (L2012 volunteer). These findings add to the limited knowledge of positive and negative volunteering effects and the perspectives of newcomers versus experienced volunteers stressed by Ferrand & Skirstad (Citation2017).

Societal level

Whether the intentions to volunteer post-event are sustained and transform behaviour equally depend on good quality management and new opportunities. This relates to the element of ‘new initiatives’ (Preuss Citation2015, 2019) when skills, knowledge, expertise, and networks remain latent until and unless they are used to generate ‘value’. Volunteers either proactively search for these opportunities themselves or get support from the existing or created structures that endure post-event. This involves effective planning and coordination among the event stakeholders and their ability to cultivate successfully established networks to facilitate the process of legacy creation. Evidence from this study, however, showed that a lack of well-planned and effectively managed effort tied in with too many expectations on LOCOG to deliver on the legacy promises became the major weakness that contributed to a volunteering legacy not being realised. The Games delivery took the ultimate priority, which resulted in the momentum to capitalise on the enthusiasm of 70,000 GMs being lost. Although able to attract first-time volunteers, LOCOG neither prioritised nor had the capacity to make them regular volunteers as this temporary organisation ceased to exist after the Games.

The Join In charity, launched in May 2012 by the UK Government (House of Lords, Citation2013), became responsible for the Games volunteering legacy, which is a sensible approach taken by a local stakeholder having long-term stakes in the host destination development (Smith, Citation2012, Citation2014). However, its effectiveness is rather obscure due to ‘ … no agreements reached on what, if anything, could have happened before the Games … From the government’s point of view … legacy meant ‘what happens after the Games’’ (Chair of L2012 VSG). This was evident in the delay to pass over the Games volunteer database from the owner (LOCOG) to Sport England, which ‘should have been done … before the Games even started not to lose time between the Games finishing and getting back to people’ (Chair of L2012 VSG). It is critical to ‘fill a hole’ (Fairley et al., Citation2014) as soon as possible as volunteers with positive experiences feel the loss with the end of the Games and want to continue volunteering. Therefore, the work of Join In began too late to reach its maximum potential. Moreover, the organisation became focussed exclusively on sport, whereas the motivation to volunteer for the Olympic event ‘[does] not necessarily extend to wishing to become involved with a sports club on a regular basis’ (House of Lords, Citation2013, p. 84). This is also evidenced through current research: ‘Olympic Games are one-off special things, which are difficult to translate to other, more ordinary volunteering’ (L2012 volunteer). This supports the fact that Olympic volunteering is very different from ongoing sport and community volunteering, which may result in first-time volunteers becoming one-time volunteers.

This shows inconsistencies between the policy statements and the practices adopted, and the implications this has had for volunteer experiences, the Games operations and, ultimately, programme outcomes. It became evident that the key principle of the Volunteering Strategy to leave a sustainable volunteering legacy for local communities was violated. The explicit commitments developed by multiple stakeholders before the Games were essential but not sufficient to deliver on these promises. The right processes and mechanisms (e.g. political, financial, and managerial resources) should have been in place throughout the entire event lifecycle to ensure desired outcomes. Their absence, however, inevitably poses a question about the effectiveness of the IOC legacy rhetoric, an issue that should inform current and potential host cities.

Conclusions and implications

This research addressed the major methodological limitation in producing evidence for practice and policymaking, which lies in ‘the absence of an understanding of processes and mechanisms which either produce or are assumed to produce particular impacts or outcomes’ (Coalter, Citation2007, p. 2). The study was concerned with the Contexts, Mechanisms and Outcomes (Pawson Citation2013) of the London 2012 volunteer programme, which helped answer the research question about how it worked, for whom, in what circumstances, to what effect and over what duration, and what improvements could be made to achieve better programme results.

Olympic volunteering was conceptualised and operationalised via a carefully designed framework (see ) representing the blend of three theories never applied in such a combination and to the event context before. It was built on the premise that the nature of volunteering is multi-dimensional, multi-layered, and context-specific, which has implications for its planning and management. Olympic volunteering was approached as a ‘life cycle’ (VPM model), which addressed the lack of details on volunteering processes, experiences, and consequences as they occur and unfold on different levels of analysis (Ferrand & Skirstad, Citation2017). Volunteer management practices were unpacked in their influence on volunteering experiences and programme outcomes (HRM model), contributing to scarce knowledge on strategic and operational processes of volunteer programmes (Chanavat & Ferrand, Citation2010). Moreover, the study was placed within legacy rhetoric (Legacy Cube) to identify legacy outcomes and changes in five structures related to volunteering – infrastructure, policy, knowledge, networks, and emotions (Preuss, Citation2019).

Overall, the proposed framework helps explore volunteering holistically and from the interdisciplinary perspective lacking in the literature (Doherty, Citation2013; Ferrand & Skirstad, Citation2017). The key theoretical contribution of this study is in applying the critical realism approach and confirming its main postulate: it is not the programmes that produce results, but their resources, interpretations, and actions by various subjects. The practical implication for event organisers/evaluators, therefore, lies in their ability to recognise what choices the volunteer programme subjects make, within what resource constraints, and the consequences of their (in)actions. Importantly, adequate systems, mechanisms and processes must be in place to ensure effective volunteer management and a sustainable volunteering legacy.

Research limitations

A narrow focus on London 2012, the purposive sampling, and a small sample size potentially limited generalisability and transferability of the research findings (Bryman, Citation2012). However, this study was concerned with theoretical/analytical (not empirical) generalisability that goes ‘beyond the setting for the specific case or specific experiment that had been studied’ (Yin, Citation2014, p. 40). These generalisations can be in the form of the lessons learned from London 2012 detailed in this research. Knowledge obtained from the most informed sources relevant to the case (Chanavat & Ferrand, Citation2010) further enriched the study’s value. The longitudinal design helped track changing attitudes, behaviours, and outcomes through time, which is essential for legacy focused research. Yet, more time is needed to evaluate longer-term legacies that span several decades (Preuss, Citation2019), which might be organisationally and financially challenging to accomplish (Burns, Citation2000).

Future research

More and more sport events will be pressured to deliver long-term value in the public interest. The priority will be increasingly on minimising failures/declarations and maximising evidence of positive outcomes that improve the quality of life, such as strengthening the social fabric and creating a sense of ‘global community’ post-event. Therefore, the need to engage in careful strategic planning and effective management of sustainable event legacies will be paramount. This depends, above all, on a proper design, monitoring, and evaluation of associated volunteer programmes. The proposed framework represents a useful tool to help achieve this end. Applying it to other sport event settings and cultural contexts, on a bigger scale, and over a longer duration will further strengthen the research, policy, and practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Auld, C., Cuskelly, G., & Harrington, M. (2009). People and work in events and conventions: A research perspective. In T. Baum, M. Deery, C. Hanlon, L. Lockstone, & K. Smith (Eds.), Managing volunteers to enhance legacy potential of major events. 1st ed. (pp. 181–192). CABI. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845934767.0181

- Bang, H., & Chelladurai, P. (2009). Development and validation of the volunteer motivations scale for international sporting events (VMS-ISE). International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 6(4), 332–350. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2009.030064

- Baum, T., & Lockstone, L. (2007). Volunteers and mega sporting events: Developing a research framework. International Journal of Event Management Research, 3(1), 29–41. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.516.2668&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Bhaskar, R. (1975). A realist theory of science. Harvester.

- Bhaskar, R. (2008). A realist theory of science (with a new introduction). Routledge.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), Apa handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Volume 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004

- Brown, A., & Massey, J. (2001). Literature review: The impact of major sporting events. The sports development impact of the Manchester 2002 Commonwealth Games: Initial baseline research. UK Sport. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Literature-Review%3A-The-Impact-of-Major-Sporting-MasseyBrown/bf510205490e62fbfe6f6c2b7a6fe6dfd4163896.

- Bryman, A. (2012). Social research methods (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Burns, R. B. (2000). Introduction to research methods (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Byers, T. (2009). Using critical realism: Understanding control in voluntary sport organizations. Critical Realism Action Group (CRAG), ESRC-funded workshop series. Leeds University.

- Byers, T. (2013). Using critical realism: A new perspective on control of volunteers in sport clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2012.744765

- Byers, T., & Thurston, A. (2011, September 7-10). Using critical realism in research on the management of sport: A new perspective of volunteers and voluntary sport organisations [paper presentation]. Commitment in Sport Management: The 19th conference of the European Association for Sport Management, Madrid, Spain. European Association for Sport management.

- Chanavat, N., & Ferrand, A. (2010). Volunteer programme in mega sport events: The case of the Olympic winter games, Torino 2006. International Journal of Sport Management and Marketing, 7(3/4), 241–266. http://www.inderscience.com/offer.php?id=32553 https://doi.org/10.1504/IJSMM.2010.032553.

- Chelladurai, P., & Madella, A. (2006). Human resource management in Olympic sport organisations. Human Kinetics.

- Clark, G. (2008). Local development benefits from staging global events. OECD Publishing.

- Cnaan, R. A., Handy, F., & Wadsworth, M. (1996). Defining who is a volunteer: Conceptual and empirical considerations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 25(3), 364–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764096253006

- Coakley, J., & Souza, D. L. (2013). Sport mega-events: Can legacies and development be equitable and sustainable? Motriz: Revista de Educação Física, 19(3), 580–589. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-65742013000300008

- Coalter, F. (2007). A wider social role for sport: Who's keeping the score? Routledge.

- Cuskelly, G., Auld, C., Harrington, M., & Coleman, D. (2004). Predicting the behavioral dependability of sport event volunteers. Event Management: An International Journal, 9(1-2), 73–89. https://doi.org/10.3727/1525995042781011

- Cuskelly, G., Hoye, R., & Auld, C. (2006). Working with volunteers in sport: Theory and practice. Routledge.

- DCMS. (2007, June). Our Promise for 2012 How the UK will Benefit from the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Department of Culture, Media and Sport. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/77719/Ourpromise2012.pdf.

- DCMS. (2008, June). Before, during and after: Making the most of the London 2012 games. Department of Culture, Media and Sport. http://data.parliament.uk/DepositedPapers/Files/DEP2008-1453/DEP2008-1453.pdf.

- DCMS. (2010, December). Plans for the Legacy for the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Department of Culture, Media and Sport. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/78105/201210_Legacy_Publication.pdf.

- DCMS. (2011, June). Scope, Research Questions and Data Strategy: Meta-Evaluation of the Impacts and Legacy of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Department of Culture, Media and Sport. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/report-1-scope-research-questions-and-strategy-meta-evaluation-of-the-impacts-and-legacy-of-the-london-2012-olympic-games-and-paralympic-games.

- DCMS. (2012, March). Beyond 2012: The London 2012 legacy story. Department of Culture, Media and Sport. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/beyond-2012-the-london-2012-legacy-story.

- DeWalt, K. M., & DeWalt, B. R. (2011). Participant observation: A guide for fieldworkers (2d ed.). AltaMira Press.

- Dickson, T., & Benson, M. (2013). London 2012 Games Makers: Towards redefining legacy. Department for Culture, Media and Sport.

- Dickson, T. J., Benson, A., & Terwiel, F. A. (2014). Mega-event volunteers, similar or different? Vancouver 2010 vs London 2012. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 5(2), 164–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEFM-07-2013-0019

- Dickson, T. J., Benson, A. M., Blackman, D. A., & Terwiel, A. F. (2013). It's all about the games! 2010 vancouver Olympic and paralympic winter Games volunteers. Event Management, 17(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599513X13623342048220

- Doherty, A. (2009). The volunteer legacy of a major sport event. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 1(3), 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407960903204356

- Doherty, A. (2013). “It takes a village:” interdisciplinary research for sport management. Journal of Sport Management, 27(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.1.1

- Downward, P. M. (2005). Critical (realist) reflection on policy and management research in sport, tourism and sports tourism. European Sport Management Quarterly, 5(3), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740500190702

- Downward, P. M., & Ralston, R. (2013). The sports development potential of sports event volunteering: Insights from the XVII Manchester Commonwealth games. In H. Preuss (Ed.), The impact and evaluation of major sporting events (pp. 27–46). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315878195

- Elstad, B. (1996). Volunteer perception of learning and satisfaction in a mega-event: The case of the XVII Olympic winter Games in lillehammer. Festival Management and Event Tourism, 4(3-4), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.3727/106527096792195290

- ESRC. (2010, October). Olympic Games impact study – London 2012 pre-games report. Final. Economic and Social Research Council. https://esrc.ukri.org/files/news-events-and-publications/news/2014/olympic-games-impact-study-london-2012-pre-games-report/.

- Fairley, S., Green, C., O’Brien, D., & Chalip, L. (2014). Pioneer volunteers: The role identity of continuous volunteers at sport events. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 19(3-4), 233–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775085.2015.1111774

- Farrell, J. M., Johnston, M. E., & Twynam, D. G. (1998). Volunteer motivation, satisfaction, and management at an elite sporting competition. Journal of Sport Management, 12(4), 288–300. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.12.4.288

- Ferrand, A., & Skirstad, B. (2017). The volunteers’ perspective. In M. M. Parent, & J.-L. Chappelet (Eds.), Routledge handbook of sports event management (pp. 65–88). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203798386

- Galindo-Kuhn, R., & Guzley, R. (2001). The volunteer satisfaction index. Journal of Social Service Research, 28(10), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.1300/J079v28n01_03

- Giannoulakis, C., Wang, C.-H., & Gray, D. (2007). Measuring volunteer motivation in mega-sporting events. Event Management, 11(4), 191–200. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599508785899884

- Girginov, V. (2012). Governance of the London 2012 Olympic Games legacy. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 47(5), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690211413966

- Green, C., & Chalip, L. (2004). Paths to volunteer commitment: Lessons from the Sydney Olympic games. In R. A. Stebbins, & M. Graham (Eds.), Volunteering as Leisure / Leisure as volunteering. An International assessment (pp. 49–70). CABI Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851997506.0000

- Hall, M. C. (2001). Imaging, tourism and sports event fever: The Sydney Olympics and the need for a social charter for mega-events. In C. Gratton, & I. P. Henry (Eds.), Sport in the city: The role of sport in economic and social regeneration (pp. 166–183). Routledge.

- Hamm-Kerwin, S., Misener, K., & Doherty, A. (2009). Getting in the game: An investigation of voluteering in sport among older adults. Leisure/Loisir, 33(2), 659–685. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2009.9651457

- Haski-Leventhal, D., & Bargal, D. (2008). The volunteer stages and transitions model: Organizational socialization of volunteers. Human Relations, 61(1), 67–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726707085946

- Horne, J. (2007). The four ‘knowns’ of sports mega-events. Leisure Studies, 26(1), 81–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360500504628

- Horne, J., & Manzenreiter, W. (2006). An introduction to the sociology of sports mega-events. The Sociological Review, 54(s2), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2006.00650.x

- House of Lords. (2013, November). Keeping the flame alive: The Olympic and Paralympic legacy. Report of session 2013-14. The Stationery Office. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201314/ldselect/ldolympic/78/78.pdf.

- Hoye, R., & Cuskelly, G. (2009). The psychology of sport event volunteerism: A review of volunteer motives, involvement and behaviour. In T. Baum, M. Deery, C. Hanlon, L. Lockstone, & K. A. Smith (Eds.), People and work in events and conventions: A research perspective (pp. 171–180). CABI.

- Hustinx, L., Cnaan, R. A., & Handy, F. (2010). Navigating theories of volunteering: A hybrid map for a complex phenomenon. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40(4), 410–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2010.00439.x

- Hustinx, L., & Lammertyn, F. (2003). Collective and reflexive styles of volunteering: A sociological modernization perspective. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 14(2), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023948027200

- IOC. (2018). Sustainability Essentials. A Series of Practical Guides for the Olympic Movement. International Olympic Committee. https://stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/IOC/What-We-Do/celebrate-olympic-games/Sustainability/sustainability-essentials/IOC-Sustain-Essentials_v7.pdf.

- Iosifides, T. (2011). A generic conceptual model for conducting realist qualitative research: Examples from migration studies (Working Paper No 43). International Migration Institute: University of Oxford.

- Kemp, S. (2002). The hidden workforce: Volunteers’ learning in the olympics. Journal of European Industrial Training, 26(2-4), 109–116. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090590210421987

- Khoo, S., & Engelhorn, R. (2011). Volunteer motivations at a national special Olympics event. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 28(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.28.1.27

- Leopkey, B., & Parent, M. M. (2012). Olympic Games legacy: From general benefits to sustainable long-term legacy. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(6), 924–943. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2011.623006

- LOCOG. (2012a). Locog volunteer policy games time. The London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games.

- LOCOG. (2012b). My Games Maker pocket guide. The London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games.

- LOCOG. (2012c). My Games Maker workbook: London 2012. The London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games.

- LOCOG. (2012d). My Games Maker Training CD: London 2012. London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

- LOCOG. (2013). London 2012 report and accounts. Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games Ltd. http://www.olympic.org/Documents/Games_London_2012/London_Reports/LOCOG_1month_Report_Sept2012.pdf.

- Lois, J. (1999). Socialization to heroism: Individualism and collectivism in a voluntary search and rescue group. Social Psychology Quarterly, 62(2), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695853

- Love, A., Hardin, R., Koo, G. Y., & Morse, A. (2011). Effects of motives on satisfaction and behavioral intentions of volunteers at a PGA tour event. International Journal of Sport Management, 12(1), 86–101.

- Lukka, P., & Ellis, P. A. (2001). An exclusive construct? Exploring different cultural concepts of volunteering. Voluntary Action, 3(3), 87–109.

- MacAloon, J. (2000). Volunteers, global society and the Olympic movement. In M. Moragas, A. Moreno &, & N. Puig (Eds.), Symposium on volunteers, global society and the Olympic movement. November 24–26th, 1999 (pp. 17–28). International Olympic Committee.

- Nedvetskaya, O., & Girginov, V. (2017). Volunteering legacy of the London 2012 olympics. In I. Brittain, J. Bocarro, K. Swart, & T. Byers (Eds.), Legacies and mega-events: Fact or fairy tales? (pp. 61–78). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315558981

- Nedvetskaya, O., Purcell, R., & Hastings, A. (2015). Looking back at London 2012: Recruitment, selection and training of Games makers. In G. Poynter, V. Viehoff & Y. Li (Eds.), The London Olympics and urban development: The mega-event city (regions and cities) (pp. 293–306). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315758862

- Nichols, G., & Ralston, R. (2013). Volunteering for the games. In V. Girginov (Ed.), Handbook of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games: Volume two: Celebrating the games (pp. 53–70). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203126486

- Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (2002). Considerations of community. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(5), 846–867. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764202045005007

- Parent, M. M., & Smith-Swan, S. (2013). Managing major sports events: Theory and practice. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203132371

- Pawson, R. (2013). The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. SAGE Publications.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (2004). Realist evaluation. British Cabinet Office. http://www.communitymatters.com.au/RE_chapter.pdf.

- Preuss, H. (2007). The conceptualisation and measurement of mega sport event legacies. Journal of Sport & Tourism, 12(3-4), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/14775080701736957

- Preuss, H. (2015). A framework for identifying the legacies of a mega sport event. Leisure Studies, 34(6), 643–664. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.994552

- Preuss, H. (2019). Event legacy framework and measurement. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 11(1), 103–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2018.1490336

- Ralston, R., Lumsdon, L., & Downward, P. M. (2005). The third force in events tourism: Volunteers at the XVII Commonwealth games. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 13(5), 504–519. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580508668576

- Shipway, R., Lockstone-Binney, L., Holmes, K., & Smith, K. (2020). Perspectives on the volunteering legacy of the London 2012 Olympic Games: The development of an event legacy stakeholder engagement matrix. Event Management, 24 (5), 645–659. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599519X15506259856327

- Silvestre, G. (2009). The social impacts of mega events: Towards a framework. Esporte e Sociedade, 4(10), 1–26.

- Smith, A. (2012). Events and urban regeneration. Routledge.

- Smith, A. (2014). Leveraging sport mega-events: New model or convenient justification? Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 6(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2013.823976

- Smith, A., & Fox, T. (2007). From 'Event-led' to 'Event-themed' regeneration: The 2002 Commonwealth Games legacy programme. Urban Studies, 44(5-6), 1125–1143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980701256039

- Smith, D. H. (1994). Determinants of voluntary association participation and volunteering: A literature review. Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 23(3), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/089976409402300305

- Smith, J. A., & Osborne, M. (2008). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A Practical Guide to research methods (2nd ed., pp. 53–80). Sage Publications.

- Stebbins, R. A., & Graham, M. (eds.). (2004). Volunteering as leisure/leisure as volunteering: An international assessment. CABI Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1079/9780851997506.0000

- Vanwynsberghe, R. (2015). The Olympic Games impact (OGI) study for the 2010 winter Olympic Games: Strategies for evaluating sport mega-events’ contribution to sustainability. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 7(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2013.852124

- VSG. (2006). The London 2012 Olympic Games and Paralympic Games volunteering strategy. Volunteering Strategy Group, London 2012.

- Weed, M. (2005). Sports tourism theory and method—concepts, issues and epistemologies. European Sport Management Quarterly, 5(3), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184740500190587

- Wicker, P., & Hallmann, K. (2013). A multi-level framework for investigating the engagement of sport volunteers. European Sport Management Quarterly, 13(1), 110–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2012.744768

- Wilks, L. (2016). The lived experience of London 2012 Olympic and paralympic Games volunteers: A serious leisure perspective. Leisure Studies, 35(5), 652–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.993334

- Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215

- Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteerism research: A review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(2), 176–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011434558

- Yanow, D. (2007). Qualitative-interpretive methods in policy research. In F. Fischer, G. J. Miller, & M. S. Sidney (Eds.), Handbook of public policy analysis: Theory, politics, and methods (pp. 405–416). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315093192

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Zhuang, J., & Girginov, V. (2012). Volunteer selection and social, human and political capital: A case study of the Beijing 2008 Olympic games. Managing Leisure, 17(2-3), 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2012.674397