ABSTRACT

Research question

This paper reviews the period of the last four decades and evaluates the significance of four major themes in the macro-environment of sport management and policy. These themes are (a) the shift in international relations from a bi-polar to a multi-polar model; (b) the challenging of teleological assumptions concerning the development of western models of modernization, and their replacement with accounts of multiple modernities; (c) the emergence of Populism and the changing nature of political Ideology and sport policy; and (d) contemporary notions of language, truth, discourse.

Research methods

The paper presents a review of relevant literature in the fields of philosophy, politics, policy and discourse analysis, identifying the impact and significance of such changes.

Research findings and implications

The findings highlight the need for policy and management to adapt to the new realities. (a) First, operating within a multipolar international relations system implies adaptation to the erosion of western hegemony in the international sports economy. (b) Second, challenge to the dominance of the western modernization thesis, by proponents of multiple modernities, implies a requirement to serve needs of heterogeneous markets within culturally diverse societies. (c) Third, the development of the politics of cultural populism, requires managers/policy-makers to understand and resist the use of sport in promoting negative, non-inclusionary ideological messages. (d) Finally, the undermining of notions of truth in public discourse, will require managers to defend evidence-based policy, and publicly acknowledged criteria of truth in decision-making.

Introduction

There is an explicit claim in the title of this special issue, that a ‘new era’ has emerged over the period since the publishing of the European Journal of Sport Management EASM (European Association for Sport Management) was inaugurated in 1993, and subsequently ESMQ was first published in its current form in 2001. This claim invites examination in terms of whether substantive changes in the sports policy and management environment have indeed taken place; whether such changes are sufficiently significant to warrant the ascription of the term ‘new era’; and what they might imply for policy and practice in sport management. The goal of this paper is to construct a response to these questions by focusing selectively on four key themes which frame the macro-environment in which sport policy and sport management practice, and the analysis of that practice, takes place. These are four themes which, while they do not exhaust the key features of change, nevertheless, are socially, politically and economically important in framing important aspects of change in the macro-environment.

Before proceeding with the argument, two preliminary details should be highlighted. The first is that in the literature there is a significant overlap in the use of the terms ‘policy’ and ‘management’ (Pal, Citation2013). In this context, we employ the term ‘sport policy’ to refer to the specification of ends to be achieved (by governments or the boards of commercial or third sector bodies), and the preferred means of achieving those ends through sport (e.g. sport as a vehicle to promote gender equity, or multiculturalism). ‘Sport management’ is used to refer to the exercise of means (human, financial, planning, decision-making, etc.) to reach organizational goals efficiently and effectively, thereby achieving policy ends in sporting contexts in an appropriate manner.

The second preliminary point is that the roles and strategic options available to the sport manager, the sport policy maker or analyst, are contingent on the macro, meso, and micro-environments within which they operate. The micro-environment relates to issues such as the size and significance of local, or sectoral, market features, and the tactical and operational opportunities or constraints that those involved in sport policy and management decision-making are presented with, at the organization or business level (in for example the development of marketing plans or strategic business planning). Meso-level features relate to the activities influencing the sectoral environment in two principal ways. The first would include, for example, direct efforts by regulatory sporting bodies and by governments to shape the activities of the sector by specifying, in direct terms, organizational governance requirements, (e.g. regulations requiring organizations to report financial performance or transactions in particular ways). The second way involves promoting activities indirectly (e.g. through grant aid rather than legislative powers) to foster the achievement of policy goals or desired externalities in what is identified in the literature as ‘political governance’ (Henry & Lee, Citation2004). Consideration of the macro-environment focuses analysis on the wider political, economic, social, and cultural contexts within which sport management and policy is conceived and operates, and it is at this third level that analysis will be addressed. Content analysis of ESMQ and of the European Journal of Sport Management indicates that vast majority of material published in these journals relates to micro and meso-levels of analysis (Pitts et al., Citation2014).

In the argument which follows, the claim will be made that important changes have indeed taken place over the period of the last three to four decades in the macro-environment of sport management. Examples of events which symbolize and/or elicit change would include, in the technological sphere, the launching of the world wide web and commercial email in 1989; in the political sphere the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989; in the ecological sphere the impact of climate change; and in the socio-medical sphere, the impact of the global Covid-19 pandemic which is highlighting new relationships between the state and civil society, balancing libertarian notions of personal freedoms with the health security requirements of the wider populations. So there are key moments or events, turning points which signpost change, but these are also invariably linked to, or indicative of, wider processes, and epochal change is almost never clear cut, starting on date ‘x’ and ending on date ‘y’.

In this commentary, we will be focusing on dimensions and processes of change in four selected domains, international relations, culture, political thought and practice, and public discourse and truth as exemplars of change at the macro-level. Each of these four domains, as will become evident, manifests forms of increasing fragmentation which shape the macro environment in which sport management and policy operate and thus have implications for the nature and complexity of knowledge and skill sets which are required in contemporary contexts.

The first of our themes involves the consequences of the transformation of international relations from a bi-polar to a multi-polar system, and its implications for understanding how sport managers will have to explain and deal with emerging cultural cleavages at the level of both intranational, and international, relations and policy. The second theme is a focus on the changing understanding of modernization processes and practices which has implications for sport and other service domains. In particular we will point to different forms of modernization developing within and across different societies, characterized by Eisenstadt and colleagues as the development of ‘multiple modernities’ (Eisenstadt, Citation2017; Fourie, Citation2012; Wittrock, Citation2002) and we will consider the implications of this for the place, and delivery of sporting opportunity in such societies. The third theme focuses on the changing nature of political and social ideologies, with the weakening of traditional ideologies, such as socialism, social democracy, or neoliberalism, and the emergence of political cleavages in emergent forms of populism (in particular cultural populism), and its implications for social policy in general, and sports and cultural policy in particular. The fourth theme relates to changes at the meta-theoretical level in terms of modes of analysis, specifically implications in ontological and epistemological approaches for generating truth statements, and explanations of the phenomenon of ‘fake news’ together with the purported place of sport in the generation of such ‘fake news’. In the final section, we will seek to explain how fragmentation in each of these elements of the macro-environment is interrelated, and in combination reinforces emerging priorities in sport policy and management.

Theme 1: the shift from a bi-polar to a multi-polar system of international relations 1990–2022, and the implications for sports management and policy

Perhaps the most important change to the geopolitical macro-environment was signalled by the reshaping of international relations, with the collapse of the Soviet Union and of its influence over the countries of the Eastern bloc. The tearing down of the Berlin Wall in 1989, signalled the end of the bi-polar model of international relations (East versus West) in which post-war geopolitics was embedded. Debates concerning the significance of the replacement of the defunct bi-polar model of international relations by a multipolar structure have to a large extent been shaped by the work of Samuel Huntington. Huntington, in particular his influential book the Clash of Civilisations, published in 1996, which characterized the emerging field of international relations as constituted by a range of competing civilizational groups, the nine most significant of which are Western, Latin American, African, Islamic, Sinic, Hindu, Christian Orthodox, Buddhist and Japanese, each with a set of ethno-religious cultural values and beliefs which are at base mutually incompatible, such that some commentators (though, interestingly, not Huntington) concluded that if the values of the West were to prevail against those of other groups (the most significant ‘other’ being Islam), force would have to be used to protect them. This rationale was used by neo-conservative apologists in their justification for the invasion of Iraq and military action conducted elsewhere in the Middle East and Asia (Pan, Citation2005).

The premises of Huntington’s argument have, however, been subject to critical debate, most particularly because he treats the multi-polar cultures he identifies as if they were separate, compartmentalized, silos as value systems (Tibi, Citation2001). However, there are often values shared between members of different cultures which are not shared within a given culture. For example, in relation to issues of gender equity, Muslim, Christian, Jewish and secular feminist groups would often manifest greater commonalities with one another across cultures, than they would with the conservative patriarchal values of the male establishment within their own cultures (Henry, Citation2007a, p. 203), or in relation to democracy as Rafiqi’s (Citation2019, p. 689) analysis of the value placed on democracy by Muslims and Christians demonstrates, ‘Muslims in general, as well as religious and practicing Muslims, endorse democracy to the same extent as do Christians.’ Thus, the basis for maintaining fundamental ‘civilisational’ differences, is for many commentators, at best exaggerated, and at worst simply mistaken.

Nevertheless, the clash of civilizations debate does signal the intensification over the last three decades of general concerns with cultural diversity at both transnational and intra-national levels and in a variety of policy areas, not least that of sport, but also, increasingly, with the specific issues related to accommodation of refugees and asylum seekers. Analysis of the role sport can play in addressing ethno-religious cleavages, fostering the bonding, bridging and linking dimensions of social capital, has been a significant policy concern for the European Commission (Amara et al., Citation2005; Henry, Citation2007b; Henry et al., Citation2004), the European Parliament (Henry, Citation2015a, Citation2015b), the Council of Europe (Gasparini & Cometti, Citation2010; Niessen, Citation2000), and the United Nations (United Nations Organisation for Sport for Development and Peace, Citation2010).

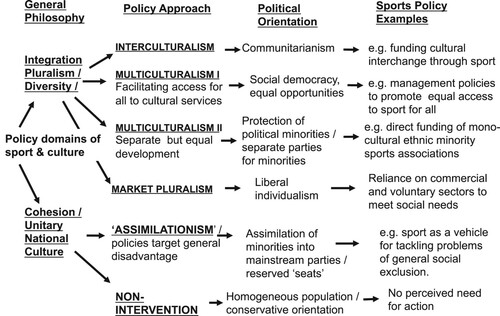

At the national level, it is also possible to identify a range of philosophies and policy approaches dealing with social integration of culturally diverse groups. The range of positions is illustrated in , and described more fully in Henry (Citation2015a).

Figure 1. Ideal typical representation of sport/cultural policy orientations.

Source: I Henry (Citation2015b).

Thus, different policy goals will imply different management orientations in terms of designing sports products and services, targeted at different population segments. (An obvious example would be policy concerning provision of services for Muslim women, which will vary according to whether policy goals are assimilation, integration, multiculturalism, or interculturalism). This clearly has implications for the education and training of sport managers to work in culturally diverse contexts.

The shift in geo-political international relations to a multi-polar model has been accompanied also by a shift in international sporting relations. Prior to the end of the Cold War, world sport was dominated by a core group of developed western sporting economies, with a semi-periphery of countries in the Eastern bloc which had gained in prominence in terms of sporting performance, but with restricted influence in terms of global sports governance, and a group of peripheral countries in Africa and Asia with virtually no significant influence on decision-making in global sporting bodies. The balance of power has however shifted with countries of the periphery and semi-periphery challenging the overrepresentation of Western interests at executive decision-making levels in the Olympic movement, in the sponsorship domain, in sports media roles, in hosting of major events, and in financial investment in sport business. Investment by the Gulf states, for example, in hosting, and bidding to host, major and mega sporting events such as the Qatar 2022 FIFA World Cup, and world tour events in sports such as golf, tennis, rugby, Formula 1 racing, and athletics (Amara, Citation2012), the rapid growth of India’s IPL in cricket (Agur, Citation2013; Khondker & Robertson, Citation2018; Siddiqui et al., Citation2019) represent strategies to generate financial and political/representational returns on investment.

Investment by Middle Eastern business interests in soccer clubs in the English Premier League, and in France, Spain, Japan and Australia has, some commentators argue, fuelled salary inflation and distorted the global football economy (Sleightholm, Citation2018). Even the most conservative of Gulf societies, Saudi Arabia, has entered the sports market recently, allegedly as a soft power tool ‘sportwashing’ its image in the wake of the Yemen war and human rights abuses such as the murder of the Saudi dissident, Jamal Khashoggi (Zidan, Citation2019).

Similar moves have been evident in recent investment by Chinese sources in western sport. In recent years it has advanced rapidly in the sports sector in relation to manufacturing, sponsorship, media rights, and club ownership, particularly in relation to football. Encouraged by President Xi Jinping’s declared ambitions in relation to sporting and economic performance domestically, and in terms of Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment (OFDI) in European football economies, Chinese investment has grown considerably in a whole range of sporting contexts (Berning & Maderer, Citation2017). As Smith and Skinner (Citation2018, p. 2) point out, ‘China has become the world’s largest supplier of sporting goods equipment, the majority of which are manufactured by small scale enterprises’ and by 2017 Chinese sports sponsorship was worth approximately $US18 billion.

Between 2015 and 2017, Chinese financiers invested $US2.5 billion, purchasing stakes and/or controlling interests in, Inter Milan and AC Milan in Italy, Manchester City, West Bromwich Albion, Aston Villa, Birmingham City, and Wolverhampton Wanderers in England, Espanyol, Granada CF, and Atletico Madrid in Spain, Sochaux in France, ADO Den Haag in the Netherlands, and Slavia Prague in the Czech league, together with smaller investments in the US and Australian soccer leagues.

These phenomena of increasing investment and control exerted by what had previously been peripheral sporting economies and polities, signal a seismic shift away from western hegemony, and a move towards a multipolar global sporting system with implications for sport managers in terms of understanding (and contributing to the achievement of) the business and political goals of these non-western investors. These investors, in some cases at least, have broader horizons than simply investment in sport. Reuters for example reports that the Suning Sports Group, which purchased a major interest in Inter Milan, hosts ambitions to, ‘create a global sporting “ecosystem” … which, through strategic expansion and acquisitions along the whole supply chain … would include club ownership, sports media rights, player agencies, training institutions, broadcast platforms, content production and sports-related e-commerce, the document shows’ (Jourdan, Citation2015).

Operating in this environment in which western sports industries compete with, and often compete for, investment from what were formerly relatively peripheral sources means that managers will require an understanding of business goals and cultures of such investors.

Theme 2: a single route to modernity or multiple modernities in contemporary societies

The debate around modernization processes is in certain respects the converse of the clash of civilizations perspective. The leading proponent of the modernization thesis, in the last three decades, has been Francis Fukuyama (Citation1992, 2020) whose influential text The End of History and the Last Man is focused not on the development of competing value systems, but rather on the inevitable convergence of societies around a modernization agenda in which the success of the (western) scientific world view in addressing technological solutions to societal problems, combined with the strength of neo-liberal economics in dealing with challenges to economic growth, and the political strength of liberal democracies, would lead to the adoption of a common route to ‘progress’ emulating the path of modernization adopted by the western nation states. Fukuyama’s use of the phrase ‘the end of history’ signals his view (at least at the time of publication of his book) that we had been reaching the end of debate about the desired direction and the trajectory of development of societies, and that ‘the rest’ including most notably those of the former communist bloc, would simply follow the path to ‘progress’ beaten by the West. The collapse of the Soviet Union and of the communist bloc in political and economic terms was thus seen as a precursor to the ‘inevitable’ establishing of neo-liberal democracies made in the West’s image.

Fukuyama’s argument is a sophisticated version of modernization theory, a species of social theory that had been the dominant paradigm in explanations and predictions of the trajectory of modern social development, but had been under attack from the 1960s. The revival of the modernization account was a product of the demise of communist models of development with the fall of the Wall in 1989, and of the influence of Fukuyama’s sustained account (Knöbl, Citation2003). The force of Fukuyama’s argument has however been subsequently undermined by events on the international stage. These include the Tiananmen Square protest (in which China demonstrated that although it was opening up, and thus to some extent ‘westernising’, its economy, it was certainly not adopting a Western style political model); the 9/11 bombings (in which Islamist forces forcibly rejected US political hegemony); the financial crisis of 2007–2008 (which underlined the limits of capitalism’s ability to sustain economic growth); the Arab Spring, and the failure of militarily enforced ‘democratisation’ of Iraq and Afghanistan (Milne, Citation2012).

However, the claim that the western road to modernity is going to be emulated by societies with histories as disparate as China (Makeham, Citation2020), India, and Russia (Maslovskaya & Maslovskiy, Citation2020), is too simplistic. Rather than convergence towards a unitary template of modernity, Eisenstadt (Citation2017) and his colleagues suggest that what in effect is developing are ‘multiple modernities’. As Fourie argues, assumptions about the convergence of modern societies

come under particular attack for assuming that structural differentiation and the growth of institutions such as liberal democracy, capitalism and the bureaucratic state are inevitable features of ‘modernizing’ societies throughout the world and will invariably be accompanied by individualism, a secular world-view and other cultural dimensions. (Fourie, Citation2012, p. 54)

In crude terms the modernization thesis suggests that the configuration of the elements of urbanization, industrialization, mass education, economic growth, and the development of wealth, will inevitably lead to the development of democratic policies and secular, globalized cultures (Wucherpfenning & Deutsch, Citation2009). However, the key elements of modernization are not these institutions, since institutional configurations will vary from one society to the next, even within the West.

For proponents of the multiple modernities argument, the defining feature of modernity is not these institutions or organizational forms, but rather is a way of thinking, a set of abstract ontological and cultural principles, a ‘rational and scientific’ world view, in which individuals can make choices in relation to the development of their societies.

The most important of these principles is a conception of human agency … a conception of humans as autonomous and able to exercise control over their environment through rational mastery and conscious activity. (Fourie, Citation2012, p. 56)

Al Wahaib’s study is based on detailed life history interviews focusing on changing sport and leisure behaviour with a sample of 61 interviewees who are female Kuwaiti citizens stratified by age and social class. She points to the key institutions of modernity, which exist in present day Kuwait, but goes on to highlight their culturally specific nature. For example, industrialization has taken place in Kuwait (but is based around a single sector, the petro-chemical industry). Rapid urbanization has taken place (but in the form of a single urban conglomeration, Kuwait City, which incorporates 96% of the national population, and has absorbed Bedouin groups from previously nomadic cultures). The country has wealth (in the form of private income on the part of the merchant class safeguarded by protectionist policies of the state, and which for middle (Hadhar) and lower (Badu) social classes takes the form of financial redistribution by the rentier state, provision of state services and a right to employment). The country is a Constitutional Emirate and has developed limited elements of political democracy (it has an elected National Assembly, and since 2005 women have been politically enfranchized). The point here is that, though the elements of modernity are evident, they take on a form which is specific to Kuwait. Modernity in Kuwait is somewhat different from modernity in the USA, or Western Europe, or even in other Gulf states, and perhaps the major point of departure from western paths to modernity is that while western perspectives on modernity are associated with the development of a secular state and society, in Kuwait Islam is the state religion, and religious organizations exercise considerable influence.

In her analysis of Kuwaiti society and of her sample, Al Wahaib identifies a heterogeneous range of attitudes, which she classifies under five forms of religiosity, three of which are evident in the subjects in her sample. The first of these three is that of Muslim Liberals, who take a predominantly secular view about leisure behaviour, arguing that this is a matter of personal choice of the individual, and who adopt a pro-modernity stance. This is a form of individualism. The second group is Islamic Reformists, who support women’s right to exercise and play sport in public spaces (as long as requirements of modesty, such as the wearing of the hijab and abbaya, are met). This represents an approach of seeking to accommodate modernity – a pluralist view. The third group identified in her sample is that of Religious Conservatives who adopt a monocultural perspective, adopting constitutional means to impose a set of limits on behaviour – typically, for example, in debates about the application of Sharia. This might be described as an anti-modernity position.Footnote1 It is thus clear that the types of sports provision made for the local community will have to accommodate the different world views of the local Muslim population. Providing the same service for Muslim liberals, Reformists, and Conservatives simply will not work and sport managers will thus be required to understand the preferred ways of life of such groups, and in turn this has implications for the education of sport managers.

The existence of this spectrum of views on lifestyle within this micro-state demonstrates that not only is there likely to be heterogeneity of modernization across nations, but that there is heterogeneity in respect of support for modernization and modern lifestyles within populations. Underpinning these different life patterns/lifestyles of female Kuwaiti citizens, are different versions of modernity, where modernity is defined not by institutions but by the critical use of reason by autonomous agents with critical rationality being employed in competing explanations of what constitutes an appropriate lifestyle to adopt. This diversity of concepts of modernity is something which Fukuyama’s argument cannot accommodate. As Kim and Hodges (Citation2005, p. 217) point out Fukuyama's ‘paradigm of monocentric diffusion recognizes no standard of civilization other than the Western one’.

However, managing multiple modernities means managing diversity. Working effectively in a modernizing Muslim society such as Kuwait will require an understanding of the process of modernization in different segments of the population/market. Even at a simple level in relation to dress, Muslim Liberals are likely to tend towards sporting provision which offers freedom of choice in dress, Islamic Reformists will be more likely to favour provision which allows opportunity to exercise in clothing that reflects traditional requirements of modesty, while Religious Conservatives will be reluctant to participate in the public domain. This element of segmentation will have implications for design of products and services, facility design, advertising, staffing, etc.

Thus, the principal implication for the sport management domain which we can highlight here is the need for management education to engage with more than simply the operational skills of management, but also for it to address the nature of intercultural contexts in global and local environments. It is critical that in particular those sport managers and policy analysts working at a strategic level have the tools to address the demands of working in an increasingly globalizing environment understanding how global forces are mediated in specific ‘glocalised’ contexts (Giulianotti & Robertson, Citation2012; Robertson, Citation1995) even in population segments within particular societies.

Theme 3: political change: the emergence of populism and the changing nature of political ideology and sport policy in Western States

Perhaps the major trend in political ideology in the West and indeed globally in recent years has been the emergence of populism as an approach to political engagement in the public sphere. Kyle and Gultchin (Citation2018) estimate that between 1990 and 2018 there were 46 populist leaders or political parties that had held executive office in 33 countries, peaking in 2018 when 20 populist leaders were holders of executive office, a five-fold increase on the figure for 1990.

Populism is not confined to a particular location on the right-left spectrum in politics, and is not therefore associated with achieving specific types of policy outcome as might be the case with traditional ideological positions such as socialism or economic liberalism. Populism has thus been defined as a ‘thin ideology’ (Mudde, Citation2004), a discursive frame (Aslanidis, Citation2016), or a performative style (Moffitt, Citation2016). A thin ideology in Mudde’s terms is distinguished from ‘thick’ ideologies, such as liberalism, socialism, conservatism and other ‘isms’ in that the latter, represent value positions with relatively coherent policy implications. As a thin-centred ideology, populism gains political currency when it is combined with a thick ideology. Thus, we can see recent examples in Europe on the political left, such as in the electoral successes of Syriza (the Coalition of the Radical Left) in Greece following the January 2015 elections (Stavrakaki & Katsambekis, Citation2014), or Podemos in Spain in the 2015 national elections, but more prominent examples have been evident on the authoritarian right, with for example, cultural populists being in power in Hungary, Macedonia, Poland, Serbia, Slovakia, Turkey, and Russia.

Forms of populism whether right or left wing in orientation share two principal claims namely that ‘A country’s “true people” are locked into conflict with “outsiders” including establishment elites’ and that ‘Nothing should constrain the will of the true people’ (Kyle & Gultchin, Citation2018, p. 3), and these two claims are commonly manifest in all three of the major types of populism, cultural, socio-economic, and anti-establishment. However, the ways in which ‘the people’ and ‘outsiders’ are discursively framed, and the key themes that they address, vary across these three types.

Socio-economic populism tends to define ‘the people’ in terms of a conscientious, honest, working class group, victims of big business, often foreign capital. The themes stressed in this form of populism relate to opposition to capitalist interests, local, regional, and global.

Anti-establishment populism defines its constituency as hard-working victims of the state, opposing political elites that represent special interests. The themes stressed are purging the state of corruption through strong leadership and governance.

Cultural populism is the most common form of populism in the European context. It adopts a ‘nativist’ approach defining native members of the nation state in overt or implied contrast to ethno-religious minorities, immigrants, ‘criminals’ and elites. The themes promoted by cultural populists relate to religious tradition, race and ethnicity, law and order, national sovereignty, national identity, and opposition to immigration.

While all three forms may be intertwined in populist strategies the dominant form of populism in Europe and the United States is cultural populism. The association of Trumpism with a particularly pernicious form of cultural populism has undermined the seemingly fragile pluralist consensus in American politics.

Trump appealed to ethnically, racially, and culturally exclusionary understandings of American identity widespread in US society, by representing Mexican immigrants as criminals, publicly battling the parents of a fallen American soldier of Muslim faith, questioning the impartiality of a Mexican-American judge, and, for years prior to the [2016 presidential] election, fanning the flames of Islamophobic and racist conspiracy theories concerning President Obama’s place of birth. (Bonikowski, Citation2019)

Similarly in the English national soccer team it took action from within the black player group (in particular by Rahim Sterling) to trigger a response from the football authorities against racist chants and actions in the context of international football (Mercer, Citation2020).

These cases illustrate the difficult position in which sport employees, managers, and entrepreneurs find themselves as populist tactics threaten freedom of speech. Such examples reinforce the argument that an understanding of political ideology and its implications for sport, is required if sport managers and policy makers are to successfully negotiate their ways through the contemporary, increasingly politically contentious context. This has clear implications for sport management education incorporating the development of tools for understanding the nature and significance of political context.

The demands of the Black Lives Matter movement constitute an example of what Laclau (Citation2018) regards as both a radical political demand, and a hegemonic political demand. As Glynos and Howarth point out ‘only demands and struggles that contest the fundamental rules of a practice and seek to institute new rules and institutions count as radical political demands’ (Glynos & Howarth, Citation2007, p. 115) and the Black Lives Matter movement’s struggle against policing and judicial practices illustrates just such a political demand. A hegemonic political demand

comes to represent a challenge to aspects of a regime of practices by successfully generalizing its relevance to other institutions and practices … [while a] … demand that is both radical and hegemonic may thus have the effect of reconfiguring an entire regime of practices in the name of a new order. (Glynos & Howarth, Citation2007, p. 116: emphasis in the original)

With the spreading of the theatre of operations from the domain of civil rights demonstrations to that of sporting spectacles, we see both the radicalization of a political demand, and its hegemonic growth into other spheres of social life, including a domain (the conducting of sporting events and spectacle) which relates directly to the sphere of influence of sport management.

The recognition of the need to protect athletes’ rights to express their views in relation to political issues is being currently debated within the context of the IOC’s Rule 50.2 (Dryden, Citation2020). Rule 50.2 of the Olympic Charter states that ‘No kind of demonstration or political, religious or racial propaganda is permitted in any Olympic sites, venues or other areas’, but it is increasingly recognized that this represents an infringement of the athlete’s right to free speech, which is articulated in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as well as other national and international conventions. The recognition of this claim means that action to decide on, and defend, the political rights of players, supporters, and the wider public to express their views will be required not only of politicians, but also of those working in sport management and the media.

Cultural populism has been a common feature of politics in European contexts, with cultural populist leaders holding executive office at some point during the twenty-first century in eight European states (of which five are post-Soviet, central, and eastern European states) (Kyle & Gultchin, Citation2018). Exploitation of sport and its relationship to national identity has been a feature of the nativist rhetoric of cultural populist parties, and of right wing extremism more generally (Brentin, Citation2016). Perhaps the most striking example of the co-optation of sport in rhetoric and policy action is that of Viktor Orban, the Hungarian prime minister and the leader of the governing FIDESZ party (the Alliance of Young Democrats) between 1998 and 2002, and from 2010 to the present day.

Theme 4: language, truth and discourse: ontology, epistemology, and fake news

The fourth theme to be highlighted relates to the discursive construction of alternate realities. The importance of understanding the process of discursive construction is illustrated in the previous section where the negative construction of ‘the other’ degrades, and devalues the ‘outgroups’ in society in articulating cultural populism. In this section we note the increasing influence of the work of Foucault over the period on which we focus, not simply in the socio-historical analysis of ideas and ideology, or, in his terms, the archaeology of knowledge (Foucault, Citation1972, Citation1980, Citation[1969] 2002; Foucault et al., Citation1988) but also more specifically on the social processes of construction of reality.

The heading of this section (language, truth and discourse) is a reference to Ayer’s (Citation1936) seminal work Language, Truth and Logic in which Ayer argues that truth claims for empirical propositions can only legitimately be made where such propositions can be subject to empirical verification through sensory experience. The substitution of the term ‘logic’, by ‘discourse’ in the heading of this section reflects the post-structuralist shift from finding ‘objective’, or at least publicly acknowledged, criteria of truth, to their focus on the social construction of ontological claims.

The significance of debate concerning objectivity and truth is most clearly illustrated in the public debacle surrounding challenges to the 2020 election of Joe Biden to the American presidency on the basis of alleged electoral fraud. A considerable number of Republican voters, it would seem, believe that the Democratic candidate won the election because of illegal manipulation of the vote. Democratic Party supporters ask, if there was voter fraud where is the evidence that could have been presented in the 60 or so court cases brought by the Trump administration in legal challenges to the vote? The response here by some Trump supporters is that members of the ‘Deep State’ have colluded to bury or destroy evidence of malpractice, and that media portrayal of the Democrat election victory was an example of the generation of ‘fake news’. In such cases there is no way of deciding the issue of which is the ‘true’ claim, by reference to empirical observation, since any such observation can only be made public through language, and discussion through language is discursively framed. Thus, in the case of the 2020 election we have Democrats claiming that there is no evidence of fraud, and a significant proportion of Republicans arguing that ‘this is fake news’. Both parties simply ‘talk past each other’ rather than agreeing on a common criterion of truth, against which both sides can measure their claims.

The post-structuralists concerns have been focused not on deciding between the truth value of such types of explanation, but rather on the underlying processes of producing what is taken to be ‘meaning’ and ‘truth’ within such types of explanation. Thus Foucault’s work focuses predominantly on the exercise of the power of discourse, and of power over discourse. A Foucauldian focus in terms of ‘power of’ discourse would be on the language and rhetoric employed, its connotative as well as denotative values, how persuasive or convincing the discourse is, the communication channels engaged, and their cultural associations (e.g. defining ‘us’ and ‘them’ in Trumpian ethno-nationalist terms – Mexican ‘rapists’ and ‘drug smugglers’, ‘Muslim terrorists’, etc.). A focus on ‘power over’ discourse would be primarily concerned with issues such as the political economy of communication, who owns the communication channels, and who exerts control over them (e.g. access to the press, television and social media, reporting).

Foucauldian approaches to analysis have become prominent in a range of subject areas of interest to us in the field of management and policy analysis, both in generic areas such as policy analysis (Schram, Citation1993), management and organization theory (Hancock & Melissa, Citation2001; McKinlay & Starkey, Citation1998), accounting (Bowden & Stevenson-Clarke, Citation2020), and human resource management (Kamoche et al., Citation2011), but also more specifically in relation to sport and the body (Barker-Ruchti & Tinning, Citation2010; Rail & Harvey, Citation1995) sport and race, and sport for development (Darnell, Citation2007, Citation2010a, Citation2010b) sport management and policy discourse (Hu & Henry, Citation2016, Citation2017), sport coaching (Avner et al., Citation2020; Blackett et al., Citation2020; de Haan & Knoppers, Citation2020; Downham & Cushion, Citation2020; Kempe-Bergman et al., Citation2020; Kuklick & Gearity, Citation2019; Mills et al., Citation2020) and so on.

The major problem with post-structuralist accounts of truth is that, taken in isolation, since they are socially constructed (and may be constructed differently by different social groups), we cannot readily decide between the truth value of competing explanations. Indeed, we can see the havoc such a situation can produce when statements about the actions of a person or organization are dismissed as ‘fake news’ and there is no means to choose between the accusation of wrong-doing and its denial. This is problematic in the fields of natural or social science, or policy analysis. In these fields we want to make claims that some statements are true and others false, or that there is a probability that one explanation is correct, and another false, and indeed we are likely to want to base our actions, on such a claim. The need to rescue the notion of truth, and indeed to bring a greater degree of certainty into claims made in policy terms, explains the contemporary hegemony of forms of realism in contemporary social analysis, we are referring here, in particular, to critical realism, (Bhaskar, Citation1998), the evidence-based practice movement in policy analysis (Pawson, Citation2001a, Citation2001b, Citation2001c), and realist policy (Pawson, Citation2013; Pawson et al., Citation2005; Pawson & Tilley, Citation2004).

It is not that we are not interested in how discourse works in framing our view of reality – this is indeed an important set of processes to understand. For example, many of those involved in the sport and the media industries may wish to oppose the view that a focus on actions such as ‘taking the knee’ can be attributed to the influence of those harbouring ‘extremist’, Antifa sympathies. It is thus important to have an appreciation of the ways in which discourse not only paints a particular picture, but also that it is employed in the exercise of power. As Glynos and Howarth (Citation2007) point out, social and political analysis should involve (plural) ‘logics of critical explanation’.

Thus, in practical terms we also want to be able to make claims about the accuracy of description and claims of causality. In the natural sciences we have some broadly supported conventions for evaluating truth claims, classically, for example, we do this by employing randomized control trials (RCTs) in closed systems (such as laboratory experiments which are relatively closed) to test explanations of the impact of an intervention (and can subsequently go on to aggregate findings across data for a number of RCTs in meta-analysis). In management and policy contexts, however, one will almost invariably be dealing with open systems, and thus will be seeking to explain, not how X causes Y, but rather how certain outcomes can be brought about under particular circumstances by particular causal mechanisms. This is described as the goal of realist evaluation (Nielsen & Miraglia, Citation2017, p. 40).

Sport policy and management contexts are thus amenable, and increasingly subjected, to analysis employing, realist evaluation (Bell & Daniels, Citation2018; Chen & Henry, Citation2015, Citation2019) and aggregation of such qualitative evaluations in meta-synthesis (Henry, Citation2016; Li & Sum, Citation2017; Middleton et al., Citation2020). In addition, application of critical realist approaches to explanations of social phenomena as ‘socially constructed’, but nevertheless ‘real’, also reinforces grounded accounts of causal mechanisms as subject to evaluation in terms of truth (Byers et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Ryba et al., Citation2021). However, even though the nature of one of the ‘language games’ (Wittgenstein, Citation1967) in which sport policy makers and managers are obliged to engage, employs a realist logic in policy advocacy and explanation, as Glynos and Howarth’s (Citation2007) argument suggests, this is just one such language game. Post-structuralist analysis in terms of identifying ideology, interests served, and the nature of the exercise of power through discourse, illustrates the plurality of language games or ‘logics of critical explanation’ relevant to such a field.

Conclusions: sport policy and management in a new era

In this article we have been tracing aspects of change in the macro environment of sport management. illustrates the nature of the changes on which we have focused and summarizes some implications for sport policy and management. The four dimensions relate to aspects of political, cultural, social, and meta-theoretical fragmentation.

Table 1. Dimensions of political, cultural, social fragmentation: changes in the macro-environment of sport policy and management: c.980–c.2022.

Fragmentation in the geo-political context is evidenced in the shift from a bipolar to a multipolar system of international relations. Fragmentation and heterogeneity in modernization processes are also evident in the growth of multiple modernities, which exhibit subtly different characteristics and institutional arrangements from those associated with classic western, liberal democratic models of modernity. Such diversity requires culturally sensitive policy and management responses in sport as in other areas.

In the field of political ideology there is fragmentation in the development of forms of populist policy discourse, such that sport policy makers need to be aware of (and be willing to qualify or counter) the co-optation of sport into the cultural populist effort to define and denigrate the outsider, on the basis of race, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation.

Finally, we have identified fragmentation in the meta-theoretical concerns relating to ontology and epistemology. Post structuralist ontological accounts have been influential in promoting understanding of how truth has been discursively defined, and its implications for understanding the sources and exercise of power. The focus of realist analysis, by contrast, has been on basing management and policy proposals on identification of the causal mechanisms, which produce desired policy or management outcomes in defined contexts. Both such perspectives are thus relevant to critique of, and advocacy for, (sport) policy, the former in identifying power in, and/or power over, discourse and its consequences; the latter in providing grounds for policy advocacy based on causal accounts of how to bring about specific, desired outcomes.

Although the four themes we have been discussing, to some considerable degree relate to factors of a global nature, nevertheless they do not suggest a homogenous product of globalization. International relations have fragmented into heterogeneous, multipolar relations. The globalizing spread of modernity is taking on multiple, heterogeneous and local, rather than uniform global forms. Populism is manifesting itself in different forms in different contexts depending on local political conditions. Different discourses are competing in different localities, partly as a product of local histories (as we see in the case of Victor Orban’s Hungary). Rather than being viewed as a vehicle or byproduct of globalization, these factors might be said to represent examples of glocalization (Robertson, Citation1995), with the impact of global phenomena being mediated by local conditions and local agency. In the sphere of sport, local managers and policy makers are not powerless actors but can mediate the impact of global influences. They can adapt to the needs and demands of cultural and societal pluralism, and they can contribute to the resistance to the recruiting of sport to serve the needs of ideologies such as cultural populism. Of course, to engage in the battle effectively it is important to have an overview of the field. This analysis of the macroenvironment is intended to make a modest contribution to the development of such an overview, and to suggest ways in which the consideration of traditional micro and meso-level concerns of sport management education, might be enhanced by a focus on macro-level change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Al Wahaib identifies from the literature two other broad ideological positions, namely Political Islam, and Jihadism which she did not encounter among her interviewees, and which she argues are difficult to find in contemporary Kuwait given the political opposition of the Emir.

References

- Agur, C. (2013). A foreign field no longer: India, the IPL, and the global business of cricket. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 48(5), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021909613478907

- Al Droushi, A. (2017). Discourses on the modernisation agenda in sport policy in Oman; between the global and local and modernity and authenticity [Doctoral dissertation]. Loughborough University. https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/thesis/Discourses_on_the_modernisation_agenda_in_sport_policy_in_Oman_between_the_global_and_local_and_modernity_and_authenticity/9630494

- Al Droushi, A. R., & Henry, I. (2020). Modernization of athletics in Oman: Between global pressures and local dynamics. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 37(sup1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2020.1734565

- Al Wahaib, A. (2020). From tradition to multiple-modernities: An analysis of the changing recreational and Leisure lifestyles of Kuwaiti female citizens from the 1950s to 2010s [Doctoral dissertation]. Loughborough University. https://repository.lboro.ac.uk/articles/thesis/From_tradition_to_multiplemodernities_an_analysis_of_the_changing_recreational_and_leisure_lifestyles_of_Kuwaiti_female_citizens_from_1950s_to_2010s/9630449

- Al Wahaib, A., & Henry, I. (2018, October 19–21). Recreation and leisure in multiple modernities: Women’s recreational lifestyles in Kuwait’ [Paper presentation]. 2018 International Conference on Sports History and Culture: Sport on the Silk Road: East Meets West, Xi’an, Shaanxi, China.

- Amara, M. (2012). Sport, politics and society in the Arab world. Palgrave.

- Amara, M., Aquilina, D., Henry, I., Argent, E., Betzer-Tayar, M., Coalter, F., & Taylor, J. (2005). The roles of sport and education in the social inclusion of asylum seekers and refugees: An evaluation of policy and practice in the UK European year of the education through sport, report to DG education and culture. European Commission. Retrieved from Loughborough University.

- Aslanidis, P. (2016). Is populism an ideology? A refutation and a new perspective. Political Studies, 64(1_suppl), 88–104. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9248.12224

- Avner, Z., Denison, J., Jones, L., Boocock, E., & Hall, E. T. (2020). Beat the game: A Foucauldian exploration of coaching differently in an elite rugby academy. Sport Education And Society, 26(6), 676–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1782881

- Ayer, A. J. (1936). Language, truth and logic. Victor Gollancz.

- Barker-Ruchti, N., & Tinning, R. (2010). Foucault in leotards: Corporeal discipline in women's artistic gymnastics. Sociology of Sport Journal, 27(3), 229–249. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.27.3.229

- Bell, B., & Daniels, J. (2018). Sport development in challenging times: Leverage of sport events for legacy in disadvantaged communities. Managing Sport and Leisure, 23(4–6), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2018.1563497

- Berning, S., & Maderer, D. (2017). Chinese investment in the European football industry. In B. K. G. Christiansen (Ed.), Transcontinental strategies for industrial development and economic growth (pp. 223–244). IGI Global.

- Bhaskar, R. (1998). Philosophy and scientific realism. In M. Archer, R. Bhaskar, A. Collier, T. Lawson, & A. Norrie (Eds.), Critical realism: Essential readings (pp. 16–47). Routledge.

- Blackett, A. D., Evans, A. B., & Piggott, D. (2020). Negotiating a coach identity: A theoretical critique of elite athletes’ transitions into post-athletic high-performance coaching roles. Sport Education And Society, 26(1), 663–675. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2020.1787371

- Bonikowski, B. (2019). Trump’s populism: The mobilization of nationalist cleavages and the future of U.S. Democracy. In K. Weyland, & R. Madrid (Eds.), When democracy trumps populism: Lessons from Europe & Latin America (pp. 110–131). Cambridge University Press.

- Bowden, B., & Stevenson-Clarke, P. (2020). Accounting, Foucault and debates about management and organizations. Journal of Management History, https://doi.org/10.1108/Jmh-07-2020-0042

- Brentin, D. (2016). Ready for the homeland? Ritual, remembrance, and political extremism in Croatian football. Nationalities Papers-the Journal of Nationalism and Ethnicity, 44(6), 860–876. https://doi.org/10.1080/00905992.2015.1136996

- Byers, T., Gormley, K. L., Winand, M., Anagnostopoulos, C., Richard, R., & Digennaro, S. (2021). COVID-19 impacts on sport governance and management: A global, critical realist perspective. Managing Sport and Leisure, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1867002

- Byers, T., Hayday, E., & Pappous, A. (2020). A new conceptualization of mega sports event legacy delivery: Wicked problems and critical realist solution. Sport Management Review, 23(2), 171–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.04.001

- Chen, S., & Henry, I. (2015). Evaluating the London 2012 Games’ impact on sport participation in a non-hosting region: A practical application of realist evaluation. Leisure Studies, 35(5), 685–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2015.1040827

- Chen, S., & Henry, I. (2019). Assessing Olympic legacy claims: Evaluating explanations of causal mechanisms and policy outcomes. Evaluation, 26(3), 275–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389019836675

- Darnell, S. C. (2007). Playing with race: Right to play and the production of whiteness in ‘development through sport’. Sport in Society, 10(4), 560. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430430701388756

- Darnell, S. C. (2010a). Power, politics and “Sport for Development and Peace”: Investigating the utility of sport for international development. Sociology of Sport Journal, 27(1), 54–75. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.27.1.54

- Darnell, S. C. (2010b). Sport, race, and bio-politics: Encounters with difference in “Sport for Development and Peace” internships. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 34(4), 396–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723510383141

- de Haan, D., & Knoppers, A. (2020). Gendered discourses in coaching high-performance sport. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 55(6), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690219829692

- Downham, L., & Cushion, C. (2020). Reflection in a high-performance sport coach education program: A Foucauldian analysis of coach developers. International Sport Coaching Journal, 7(3), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2018-0093

- Dryden, N. (2020). Athletes should not be gagged in exchange for Olympic dream. https://www.playthegame.org/news/comments/2020/1008_athletes-should-not-be-gagged-in-exchange-for-olympic-dream/

- Eisenstadt, S. (2017). Multiple modernities. Routledge.

- Fairclough, N. (2005). Discourse analysis in organization studies: The case for critical realism. Organization Studies, 26(6), 25–45.

- Foucault, M. (1972). The archaeology of knowledge. Tavistock.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and power. In C. Gordon (Ed.), Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977 (pp. 109–133). Harvester Press.

- Foucault, M. ([1969] 2002). Archaeology of knowledge (A. Sheridan Smith, Trans.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28753-7.

- Foucault, M., Martin, L. G., & & Hutton, H. (1988). Technologies of the self: A seminar with Michel Foucault. Tavistock.

- Fourie, E. (2012). A future for the theory of multiple modernities: Insights from the new modernization theory. Social Science Information, 51(1), 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018411425850

- Fukuyama, F. (1992, 2020). The end of history and the last man. Penguin Random House UK.

- Gasparini, W., & Cometti, A. (2010). Sport facing the test of cultural diversity integration and intercultural dialogue in Europe: Analysis and practical examples. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Giulianotti, R., & Robertson, R. (2012). Glocalization and sport in Asia: Diverse perspectives and Future possibilities. Sociology of Sport Journal, 29(4), 433–454. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.29.4.433

- Glynos, J., & Howarth, D. (2007). Logics of critical explanation in social and political theory. Routledge.

- Haislop, T. (2020). Colin Kaepernick kneeling timeline: How protests during the national anthem started a movement in the NFL. Sporting News. Retrieved January 20, 2021, from https://www.sportingnews.com/us/nfl/news/colin-kaepernick-kneeling-protest-timeline/xktu6ka4diva1s5jxaylrcsse

- Hancock, P., & Melissa, T. (2001). Work, postmodernism and organization: A critical introduction. Sage.

- Henry, I. (2007a). Bridging research traditions and world views: Universalisation versus generalisation in the case for gender equity. In I. Henry (Ed.), Transnational and comparative research in sport: Globalisation, governance and sport policy (pp. 197–211). Routledge.

- Henry, I. (2007b, October 25–26). Sport and social integration strategies [Paper presentation]. Actividad Física, Deporte e Inmigración, El reto de la Interculturalidad, Madrid.

- Henry, I. (2015a). The role of sport in fostering open and inclusive societies. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2015/563395/IPOL_STU(2015)563395_EN.pdf

- Henry, I. (2015b, December 8). Sport and the social integration of refugees and asylum seekers in Europe [Paper presentation]. European Parliament Sport Intergroup, Brussels.

- Henry, I. (2016). Evaluating legacy of mega-sporting events: Lessons from the London 2012 meta-evaluation. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2016.1177356

- Henry, I., Amara, M., Aquilina, D., & PMP Consultants, (2004). Sport and multiculturalism. http://europa.eu.int/comm/sport/documents/lot3.pdf

- Henry, I., & Lee, P. C. (2004). Governance and ethics in sport. In J. Beech, & S. Chadwick (Eds.), The business of sport management (pp. 25–41). Pearson Education.

- Hensley-Clancy, M. (2021). How Kelly Loeffler’s WNBA Team Became Her Most Passionate Opponent. Buzz Feed News. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/mollyhensleyclancy/georgia-senate-race-loeffler-wnba-warnock

- Hu, X., & Henry, I. (2016). The development of the Olympic narrative in Chinese elite sport discourse from its first successful Olympic Bid to the post-Beijing games Era. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 33(12), 1427–1448. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1284818

- Hu, X., & Henry, I. (2017). Reform and maintenance of Juguo Tizhi: Governmental management discourse of Chinese elite sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 17(4), 531–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1304433

- Jourdan, A. (2015). As Inter deal nears, Chinese retail giant Suning eyes Soccer Empire. https://cn.reuters.com/article/soccer-inter-milan-suning-idUSL4N18V2YA

- Kamoche, K., Pang, M., & Wong, A. L. Y. (2011). Career development and knowledge appropriation: A genealogical critique. Organization Studies, 32(12), 1665–1679. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840611421249

- Kempe-Bergman, M., Larsson, H., & Redelius, K. (2020). The sceptic, the cynic, the women's rights advocate and the constructionist: Male leaders and coaches on gender equity in sport. International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics, 12(3), 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/19406940.2020.1767678

- Khondker, H. H., & Robertson, R. (2018). Glocalization, consumption, and cricket: The Indian Premier league. Journal of Consumer Culture, 18(2), 279–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517747094

- Kim, M., & Hodges, H. J. (2005). On Huntington's civilizational paradigm: A reappraisal. Issues & Studies, 41(2), 217–248.

- Knöbl, W. (2003). Theories that won't Pass away: The never-ending story. In G. Delanty, & E. F. Isin (Eds.), Handbook of historical sociology (pp. 96–107). SAGE.

- Kuklick, C. R., & Gearity, B. T. (2019). New movement practices: A Foucauldian learning Community to disrupt technologies of discipline. Sociology of Sport Journal, 36(4), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2018-0158

- Kyle, J., & Gultchin, L. (2018). Populists in power around the world. http://institute.global/insight/renewing-centre/populists-power-around-world

- Laclau, E. (2018). On populist reason. Verso.

- Li, M., & Sum, R. K. W. (2017). A meta-synthesis of elite athletes’ experiences in dual career development. Asia Pacific Journal of Sport and Social Science, 6(2), 99–117.

- Makeham, J. (2020). Chinese philosophy and universal values in contemporary China. Asian Studies-Azijske Studije, 8(2), 311–334. https://doi.org/10.4312/as.2020.8.2.311-334

- Maslovskaya, E. V., & Maslovskiy, M. V. (2020). The soviet version of modernity and its historical legacy: New theoretical approaches. Rudn Journal of Sociology-Vestnik Rossiiskogo Universiteta Druzhby Narodov Seriya Sotsiologiya, 20(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.22363/2313-2272-2020-20-1-7-17

- McKinlay, A., & Starkey, K. (1998). Foucault, management and organization theory: From panoptic on to technologies of self. Sage.

- Mercer, D. (2020). Millwall fans boo as players take the knee in support of Black Lives Matter movement. Sky News. https://news.sky.com/story/millwall-fans-boo-as-players-take-the-knee-in-support-of-black-lives-matter-movement-12152275

- Middleton, T. R. F., Petersen, B., Schinke, R. J., Kao, S. F., & Giffin, C. (2020). Community sport and physical activity programs as sites of integration: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research conducted with forced migrants. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 51, 101769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101769

- Mills, J., Denison, J., & Gearity, B. (2020). Breaking coaching's rules: Transforming the body, sport, and performance. Journal of Sport & Social Issues, 44(3), 244–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520903228

- Milne, S. (2012). The revenge of history. Verso.

- Moffitt, B. (2016). The global rise of populism: Performance, political style, and representation. Stanford. Stanford University Press.

- Mudde, C. (2004). The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2004.00135.x

- Nielsen, K., & Miraglia, M. (2017). What works for whom in which circumstances? On the need to move beyond the ‘what works?’ question in organizational intervention research. Human Relations, 70(1), 40–62.

- Niessen, J. (2000). Diversity and cohesion: new challenges for the integration of immigrants and minorities (ISBN 92-871-4345-5). https://www.coe.int/t/dg3/migration/archives/documentation/Series_Community_Relations/Diversity_Cohesion_en.pdf

- Pal, L. A. (2013). Beyond policy analysis – public issue management in turbulent times (5th ed.). Nelson Education.

- Pan, E. (2005). IRAQ: Justifying the war. Foreign Affairs. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/iraq-justifying-war

- Pawson, R. (2001a). Evidence based policy: 1. In search of a method: ESRC UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice.

- Pawson, R. (2001b). Evidence based policy: II. The promise of ‘realist synthesis': ESRC UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice.

- Pawson, R. (2001c). Evidence policy and naming and shaming: ESRC UK Centre for Evidence Based Policy and Practice.

- Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective. Sage.

- Pawson, R. (2013). The science of evaluation: A realist manifesto. University of Leeds.

- Pawson, R., Greenhalgh, T., Harvey, G., & Walshe, K. (2005). Realist review – a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 10(1), 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1258/1355819054308530

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (2004). Realist evaluation. Cabinet Office.

- Pitts, B. G., Danylchuk, K., & Quarterman, J. (2014). A content analysis of the European sport management quarterly and its predecessor the European Journal for Sport Management: 1984–2012. Choregia: Sport Management International Journal, 10(2), 45–72.

- Rafiqi, A. (2019). A clash of civilizations? Muslims, Christians, and preferences for democracy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 58(3), 689–706. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12614

- Rail, G., & Harvey, J. (1995). Body at work – Foucault, Michel and the Sociology of Sport. Sociology of Sport Journal, 12(2), 164–179. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.12.2.164

- Robertson, R. (1995). Glocalization: Time-space and homogeneity-heterogeneity. Sage.

- Ryba, T. V., Wiltshire, G., North, J., & Ronkainen, N. J. (2021). Developing mixed methods research in sport and exercise psychology: Potential contributions of a critical realist perspective. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197x.2020.1827002

- Schram, S. F. (1993). Postmodern policy analysis – discourse and identity in welfare policy. Policy Sciences, 26(3), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00999719

- Siddiqui, J., Yasmin, S., & Humphrey, C. (2019). Stumped! The limits of global governance in a commercialized world of cricket. Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(7), 1898–1925. https://doi.org/10.1108/aaaj-07-2018-3571

- Sleightholm, M. (2018). Middle East Ownership in European Football Sports Industry Series. Sport Industry Insider: Middle East Sport Business News. http://www.sportindustryseries.com/sports-industry-insider/middle-east-ownerhsip-in-european-football/

- Smith, A., & Skinner, J. (2018). Why do the Chinese Invest in European Football? Global Sports. https://intelligence.globalsportsjobs.com/why-the-chinese-invest-in-european-football-

- Stavrakaki, Y., & Katsambekis, G. (2014). Left-wing populism in the European periphery: The case of SYRIZA. Journal of Political Ideologies, 19(2), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13569317.2014.909266

- Tibi, B. (2001). Islam between culture and politics. Palgrave.

- United Nations Organisation for Sport for Development and Peace. (2010). Sport for Development and Peace: the UN System in Action: why sport? http://www.un.org/wcm/content/site/sport/home/sport

- Wittgenstein, L. (1967). Philosophical investigations (3rd ed.). Basil Blackwell.

- Wittrock, B. (2002). Modernity: One, none, or many? European origins and modernity as a global condition. In S. Eisenstadt (Ed.), Multiple modernities (pp. 31–60). Transaction Publishers.

- Wucherpfenning, J., & Deutsch, F. (2009). Modernization and democracy: Theories and evidence revisited. Living Reviews in Democracy, 1(1), 1–9. https://ethz.ch/content/dam/ethz/special-interest/gess/cis/cis-dam/CIS_DAM_2015/WorkingPapers/Living_Reviews_Democracy/Wucherpfennig%20Deutsch.pdf

- Zidan, K. (2019). Sportswashing: how Saudi Arabia lobbies the US's largest sports bodies. The Guardian, (2 Sept. 2019). https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2019/sep/02/sportswashing-saudi-arabia-sports-mohammed-bin-salman