ABSTRACT

Research question

Online abuse is prevalent in sport and can be the by-product of trigger events – reactive social media posts that motivate online hate. Little is known about what triggers online abuse, types of content, and how this impacts certain groups. The current research examined how online behaviour emerges, and evolves during a trigger event, through a gendered lens.

Research methods

This research employed a two phase, mixed methods approach of a digital netnography with participation observation through social network analysis and thematic content analysis of 1332 (N = 1332) tweets in the United Kingdom. The trigger event examined abusive content toward Karen Carney following post-match football commentary on 29 December 2020.

Results and findings

Results identified 590 individuals who formed two distinct groups. Directed network visualisation indicated Carney was the focus of the trigger event. Thematic time series analysis revealed emotional maltreatment (i.e. ridiculing, humiliating, belittling) progressing to overt gendered discriminatory maltreatment.

Implications

Findings support the need for safeguarding policies for target groups, as trigger events escalate quickly, and group affiliations impact abusive content. From a theoretical standpoint, in-group and out-group affiliations resulted in rhetoric highlighting persistent, gendered socio-normative issues within sport, amplified in an online environment.

Introduction

On 29 December 2020, Karen Carney (hereafter KC) was working as a football analyst for Amazon Prime in the United Kingdom (UK) along with Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink covering an English Premier League (EPL) game between Leeds United FC and West Bromwich Albion. During the live broadcast KC said the following regarding Leeds United, ‘I actually think they got promoted because of Covid in terms of it gave them a bit of respite’, (Reuters, Citation2020) implying the break in play during the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in their promotion from the Championship (second tier in English Football) to the Premier League.

Following her comments, Leeds United FC’s official Twitter feed tweeted (Leeds United FC, Citation2020) ‘Promoted because of Covid. Won the League by 10 points. Hi @primevideosport’ and included a video clip of KC delivering the comments, subsequently amplifying the comments to their more than 600,000 followers. Immediately after, KC was subjected to targeted online abuse, resulting in her deleting her Twitter account after three days. Leeds United publicly condemned the online abuse directed at KC and deleted their tweet, but never apologised. KC described the abuse as ‘relentless’ and stated it greatly affecting her mental health, even leading to suicidal thoughts (The Guardian, Citation2021). Speaking regarding the pervasive impact of online abuse in the UEFA documentary Outraged – Online Abuse, KC stated, ‘And again, I can’t say to any player or any person, ignore it. It’s impossible to ignore it. People don’t realise it’s just a wave and you can’t escape it’ (Bisset, Citation2022).

Online abuse is becoming a frequent, global occurrence within sport. Professional football players in the UK, Marcus Rashford, Jadon Sancho, and Bukayo Saka, were subjected to racial abuse on social media following missed penalty kicks during a European Championship Football final (Busby, Citation2019). Olympic athletes Simone Biles (United States), An San (South Korea), and Farida Osman (Egypt) all received online abuse during the Tokyo 2020 Games (Dudani, Citation2021; Niesen, Citation2021; Talbot, Citation2021). A World Athletics Federation commissioned study examining athlete accounts on Twitter during Tokyo 2020, found that 23 of the 161 athletes received targeted abuse, with 16 of the 23 athletes being female (World Athletics, Citation2021). These instances of online athlete abuse are illustrative of what Kilvington (Citation2020) conceptualised as ‘trigger events’ (p. 263) – incidents that drive reactive social media posts based in emotion. Within a sports setting, trigger events have been found to incite immediate online abuse (Kilvington, Citation2020). Recent efforts to call attention to the levels of online abuse towards athletes as a by-product of trigger events have included coordinated efforts between EPL clubs and players, sporting federations such as FIFA and UEFA, and media organisations, such as a four day ‘black out’ boycott of social media from 30 April to 3 May 2021 to raise awareness (The Athletic, Citation2021).

There exists a body of research that has examined online abuse – also referred to as hate speech, cyber-hate, online harms, and trolling - as it relates to race, culture, religion and gender (e.g. Bliuc et al., Citation2018; Boyd, Citation2011; HM Government, Citation2019; Jane, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Keum & Miller, Citation2018; Lumsden & Morgan, Citation2017; Throuvala et al., Citation2021; Williams et al., Citation2020). Online harms have been acknowledged by key national policy stakeholders with the publication of the Online Harms White Paper by the United Kingdom (UK) Government in 2019, which set out a new regulatory framework for online safety (HM Government, Citation2019)

While the utilisation of social media is prevalent in sport and athletes experience online abuse, research on online abuse in sport is still underexplored (Kearns et al., Citation2022; Mountjoy et al., Citation2016). Kearns et al. (Citation2022) documented growth in the area, however, most articles focused on online abuse toward athletes, while other stakeholder groups such as pundits/journalists are underrepresented. Research on football journalists has exposed a misogynistic environment and online discrimination faced by females and calls for further research examining women’s punditry has been emphasised (Bowes et al., Citation2023; Thorpe, Citation2017). To address the gap, this case study explored online abuse resulting from a trigger event from a gendered perspective to understand how and in what forms online abuse is directed towards sports actors. Specifically, employing the theoretical framework of self-categorisation, and the methodological approaches of netnography with a rhetorical analysis of content, the current research examined how online abuse emerges, escalates, and progresses throughout a trigger event within a sporting context. As a nascent area of research, the current research will enrich understanding into the forms of virtual maltreatment and abuse faced by a sports stakeholder group overlooked – sport journalists Kearns et al. (Citation2022) – and how these forms of maltreatment evolve within a trigger event. This will advance knowledge around possible triggers and patterns of online abuse, informing future training and educational practices. Findings will also heighten awareness on how to safeguard sports stakeholders (e.g. journalists, athletes, referees, coaches).

Literature review

Self-categorisation theory

Literature pertaining to online abuse has focused on content with racial, gendered, or religious undertones within White Supremacist groups, anti-Muslim rhetoric, and gendered online hate (e.g. Awan, Citation2014; Awan & Zempi, Citation2016; Braithwaite, Citation2014; Brown, Citation2009; Nakayama, Citation2017; Williams et al., Citation2020). Within these settings in-group vs. outgroup sentiments drive negative and abusive dialogue. As this paper examines the online content produced within this trigger event from an in-group vs. out-group gendered perspective, a social identity approach was considered appropriate.

Social identity theory was conceptualised by Tajfel and Turner (Citation1979) to explain interpersonal and intergroup behaviours. Building on social identity theory, Turner et al. (Citation1987) established self-categorisation theory, outlining levels of self-categorisation that contribute to self-concept: self as a human being (i.e. human identity), self as a member of a social ingroup defined against other groups (i.e. social identity), and self-defined based on interpersonal comparisons (i.e. personal identity).

One key characteristic of self-categorisation theory is depersonalisation, as individuals typically represent their ingroups in terms of prototypes. When group categorisations become established, members see themselves less as individuals and more in terms of these archetypes. Group identity also governs approved attitudes, behaviours, and emotions in each context. Thus, depersonalisation is attributed to foundations of group cohesion, conformance, and influence, and lends itself to self-categorisation theory in application toward intergroup processes (Turner et al., Citation1987). Specific to understanding intergroup processes and dehumanisation, self-categorisation theory was selected as the theoretical framework to examine the in-group vs. out-group behaviours within this trigger event. Additionally, sport, with its divisions through fandom lends itself to examination through the lens of self-categorisation theory, as previous scholars have shown (Billings et al., Citation2015; Claringbould & Knoppers, Citation2007; Wicker et al., Citation2022).

Self-categorisation theory – sport and gender

Self-categorisation theory classifies the social identity of a group, as individuals assign themselves into, ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Turner et al., Citation2012). Sport intensifies rivalries and encourages tribal mentalities, can heighten national identities, and influence fan group identification on social media (Billings et al., Citation2015). Self-categorisation theory can explain how groups divide based on other characteristics (i.e. age, race, gender). Those sharing similar characteristics belong to the same group (e.g. men) – making them the in-group. Thus, any other individuals (e.g. females, non-binary) who have different characteristics are seen as out-group members (Cunningham, Citation2004). Studies have identified these patterns related to gender (Claringbould & Knoppers, Citation2007; Wicker et al., Citation2022) and, through self-categorisation theory, research has shown that women who sit on sports boards can be excluded and disregarded from decision-making, were intentionally provided with less information, and marginalised by discussions around male orientated topics or through sexist jokes (Claringbould & Knoppers, Citation2007; Knoppers & Anthonissen, Citation2005). Marginalisation of women online through social media has also been seen, as the hegemonic masculinity of the sports industry (creating the in-group) has resulted in instances of sexualisation, misogyny and abuse directed towards women (Everbach, Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2019).

Identifying the in-group and out-group dynamics grounded in self-categorisation theory, research question one sought to understand how group boundaries are formed in an online environment:

RQ1: How did the online network form around key actors during a trigger event?

Online abuse and social media

Social media usage within sport became widespread in the 2000s, notably the 2004 Summer Olympic Games and this allowed global audiences and sport stakeholders to connect with, consume, and contribute to media coverage and online content (Geurin & Naraine, Citation2020; Liu, Citation2016). Social media (i.e. Twitter, Instagram, Tik Tok, Weibo) has many uses including community building, athlete branding, fandom, user engagement and content creation (Doyle et al., Citation2022; Fenton et al., Citation2021; Vale & Fernandes, Citation2018). Yet, the complex characteristics of social media (invisibility, dynamic/interactive nature, anonymity) exacerbate these opportunities and result in potential pitfalls (Fox et al., Citation2015; Kearns et al., Citation2022; Kilvington & Price, Citation2019). Most research to date surrounding social media abuse within sport has focused on athletes, resulting in limited research into other sport stakeholders (Kavanagh et al., Citation2019; Citation2022; Litchfield et al., Citation2018; McCarthy, Citation2022; Sanderson & Weathers, Citation2020).

While social media facilitates athlete adoration, it can equally result in abusive comments and virtual maltreatment (Kilvington, Citation2020; Suler, Citation2004). If athletes underperform, lose, or advocate for issues contradicting fans’ views, this can lead to direct emotional, physical, and sexist abuse as fans express their blame (Geurin, Citation2017; Kavanagh et al., Citation2019; Kavanagh et al., Citation2016). A BBC Sport (Citation2021) survey involving 537 Elite British athletes identified that 30% of respondents have been trolled on social media. Mountjoy et al. (Citation2016) noted there is limited research on the amount of online abuse in sport, but evidence exists that athletes frequently utilise social media for communication and branding purposes and are subjected to abuse. Although athletes are a pertinent group within sports, online abuse experienced by other sports actors, such as sports journalists, is under-researched.

Female journalists: realities and online abuse

Scholars (Jane, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Lumsden & Morgan, Citation2017) have drawn attention to gender discrimination and online abuse, with gendered and symbolic violence evident in online spaces. Online abuse and maltreatment directed towards women on social platforms can manifest as ‘contempt, profanity, insult, sexual desire, pruriency, physical threat, misogyny’ and is often directed towards women who are in the public eye and influential at societal level (Demir & Ayhan, Citation2022, p. 1).

Female journalists have been subjected to sexism and sexual violence, which has been documented within research (Adams, Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2020; Luqiu, Citation2022; Posetti et al., Citation2021). Misogyny and sexism are prevalent within journalism, which remains a heteronormative, masculinised space, and a scarcity of research has explored the online experiences of women sports journalists (Antunovic, Citation2019; Everbach, Citation2018; Hardin & Shain, Citation2005; Miller & Miller, Citation1995) and pundits in football (Bowes et al., Citation2023; Meân & Fielding-Lloyd, Citation2021; Mudrick & Lin, Citation2017).

Demir and Ayhan (Citation2022) investigated the online harassment experienced by Turkish, female sports journalists on Twitter and found comments frequently included content that was derogatory, sarcastic, and focused on physical attributes, alongside gendered exclusion, and emotional harassment. Everbach (Citation2018) examined the experiences of 12 women working within US sports media and uncovered the hegemonic masculinity within the sports industry. This resulted in women sports journalists being seen as outsiders (out-group) (Turner & Reynolds, Citation2010; Citation2012). Key strategies were suggested by participants to tackle both online and in-person abuse/harassment. They acknowledged social media has enhanced their work but also subjected them to new forms of abuse, bonding with other women sport journalists mitigates harassment, and interviewees called for enhanced regulation by social media companies and employers to stop such abuse (Everbach, Citation2018).

Silencing strategies are commonly proposed to deal with online abuse and aim to deter individuals from engaging in further discussion or promote removal from the online environment, thus placing responsibility to resolve abuse on its victims. This is achieved through advice given to victims framed around ignoring the abuse, such as ‘do not feed the trolls’ (Lumsden & Morgan, Citation2017).

Social media trigger events

Although research on online abuse is becoming more prevalent, limited studies have focused on specific sport instances (trigger events) or contexts (Cleland, Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2019; Kilvington & Price, Citation2019). Online communication around such trigger events is driven by emotion and results in reactive social media posts (Suler, Citation2004). Social media platforms by design are interactive, community-oriented and dynamic, and ‘platforms, such as Twitter, rely on instantaneous responses meaning that users are encouraged to post while angry’ (Kilvington & Price, Citation2021, p. 113). Furthermore, within the virtual environment users benefit from anonymity and invisibility. This offers both opportunities and risks and is known as ‘backstage mimicry’, where someone feels invisible whilst creating online content (Kilvington, Citation2020). Kilvington (Citation2020, p. 263) notes that trigger events can ‘lead to online posts which showcase automatic prejudice and instant stereotyping, while derogatory language is used without awareness and consideration’. This lowered level of social awareness can result in individuals posting abusive content without fully considering the impact on other fans, broader audiences, and the subject.

Online abuse and virtual maltreatment

Communication through social media is instantaneous and largely uncontrolled, resulting in the prevalence of virtual maltreatment towards individuals (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016). A scoping review by Kearns et al. (Citation2022) identified that the emotional characteristics embedded in sport are provoking ingredients for hate speech in social media. Research on social media within a sports context has focused predominately on issues such as racism, misogyny, and homophobia, or why and how athletes use social media (e.g. Geurin, Citation2017; Kearns et al., Citation2022; Kilvington & Price, Citation2019; Litchfield et al., Citation2018), resulting in calls for more empirical work focusing on the negative practices and abuse online (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016). Critically, there have been many ways in which online abuse can be defined. Kavanagh et al. (Citation2016) proposed a broader conceptualisation of virtual maltreatment ‘to examine the types of online abuse seen within the follower–athlete relationship’ (p. 787). More recently, for the purpose of the current research, focus was placed on a different sport stakeholder group - sports journalists. Given the prominence, popularity and exposure high-profile sports journalists experience, Kavanagh et al.’s (Citation2016) typology was applied as a guiding framework to examine the case study of KC. Kavanagh et al. (Citation2016) define virtual maltreatment as, ‘direct or non-direct online communication that is stated in an aggressive, exploitative, manipulating, threatening or lewd manner and is designed to elicit fear, emotional and psychological upset, distress, alarm, or feelings of inferiority’ (p. 788).

Virtual maltreatment occurs through online relationships and can be direct (using the @ symbol or through a hashtag #) or indirect (message posted about the individual). Kavanagh et al.’s (Citation2016) typology identified four types of abuse that can be experienced, and these are physical, sexual, emotional, and discriminatory, which is based upon gender, race, sexual orientation, religion and/or disability. These forms of virtual maltreatment occur between individuals, and the socio-normative values surrounding gender and sport may be contained within content. Frames, mental schemas that facilitate quick processing of information experienced in daily life, can be bound by cultural contexts, and thus illuminate persistent dominant norms and values (Goffman, Citation1974). Building upon the literature and frameworks, research questions two and three were developed:

RQ2: What forms of virtual maltreatment were present in the social media content?

RQ3: What frames were present within the online content and how did they evolve during the trigger event?

Cumulatively, the three research questions aimed to investigate the formation and type of gendered online abuse faced by sport journalist KC, in relation to a specific sport-related trigger event (post-match commentary related to Leeds United FC’s performance).

Methodology

This two-phase, mixed methods approach, employed a netnography and thematic content analysis of 1332 (N = 1332) tweets during the trigger event (29–30 December 2020). The case of KC was selected for numerous reasons. First, there is limited research on online abuse related to sport pundits/journalists (Kearns et al., Citation2022). Second, this case was initiated by specific trigger event and culminated in KC deleting her Twitter account, providing a bounded timeframe for in-depth analysis of online abuse. While previous research has included discourse analysis of online abuse that were the result of trigger events, the evolution of these events remains underexplored (e.g. Kilvington & Price, Citation2021). Third, documentation of the evolution of a trigger event will improve understanding of how trigger events progress to identify key moments where mitigation tactics could be implemented to reduce online harm.

The netnography included participant observation through a social network analysis to visualise the network of actors and identify influential accounts, relating to research question one. Thematic content analysis was employed to identify the content being shared, valence of the content, the overarching themes that emerged, and recognise the dominant frames during different stages of the trigger event. This analysis related to research questions two and three.

Netnography and sample selection

Phase one included a netnography with participant observation, which has been utilised in previous research examining online abuse (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016). The methodology was outlined by Kozinets (Citation2010) as a mechanism to examine online communication and behaviour in a natural setting with netnography an accepted form of analysis (Janta et al., Citation2014).

The population selected for analysis was related to the trigger event, however, it did satisfy Kozinets (Citation2010) criteria for study (i.e. relevance to research, active communication between actors, substantial sample, heterogenous participants, and rich data). To observe online behaviour, a social network analysis was conducted utilising NodeXL, an open-source software that interfaces with the Twitter API. To capture tweet content, a search was performed utilising the ‘@’ operator for tweets mentioning the accounts of KC (i.e. @karenjcarney) and Leeds United FC (i.e. @LUFC) as these represented the two primary communities within the trigger event. Previous research (Kilvington, Citation2020) has indicated the reactionary nature of this content, thus the timeframe of analysis began immediately following and up to 24 h post-event, employing the ‘since: year-month-day’ Twitter operator (i.e. since: 2020-12-29).

Employing these parameters NodeXL returned a total of 1332 tweets (N = 1332) for analysis. The current research study strived to create a dataset meaningful for netnographic observation and trigger event visualisation, thus, a smaller dataset was constructed.

Content analysis and coding protocol

Following the netnographic analysis, a thematic content analysis was conducted to examine the typologies of abuse and determine how themes and frames emerged and evolved during the trigger event. First, quantitative content analysis determined the typologies of abuse, and was guided by a coding protocol and codebook that employed virtual maltreatment variables defined by Kavanagh et al. (Citation2016). A variable for episodic and thematic framing (Iyengar, Citation1991) was included in the codebook as observational analysis indicated individual responsibility (i.e. episodic) of abuse directed toward KC (i.e. KC did a lack of research) as well as socio-normative gender attributions (i.e. thematic) associated with macro, societal level responsibility of abuse in this case (i.e. women don’t belong in football).

Coding was divided between three trained coders and intercoder reliability was performed on 10% of the dataset (n = 132) to test for chance agreement between coders. All three coders reviewed the same dataset and independently coded the variables, then Fleiss (Citation1971) kappa values for multi-rater agreement were calculated. All variables reached agreement (i.e. 0.81–1.00) as outlined by Landis and Koch (Citation1977), except for virtual maltreatment and sentiment, which reached substantial agreement (i.e. 0.61–0.80) of 0.72 and 0.67, respectively. contains all coding variables and definitions based on Kavanagh et al.’s (Citation2016) framework, as well as the individual kappa values.

Table 1. Codebook variables.

Following quantitative content analysis, descriptive qualitative coding was performed to summarise tweet content into a single word or phrase indicative of the topic of content (Saldaña, Citation2021). Building upon descriptive coding, two rounds of inductive thematic qualitative coding were employed allowing a narrative to emerge from the descriptive codes. Reoccurring descriptors were refined into salient thematic categories utilising focused coding (Saldaña, Citation2021). Axial coding further condensed the themes into broader conceptual categories of frames based on similar properties (Saldaña, Citation2021) to reveal culturally specific meaning (Goffman, Citation1974) and were tracked to examine the evolution of content during the 24-hour time period of analysis. Within the inductive coding process, each coder determined the themes and subsequent frames independently, then investigator triangulation was employed (Denzin, Citation1989).

Results

Social network analysis

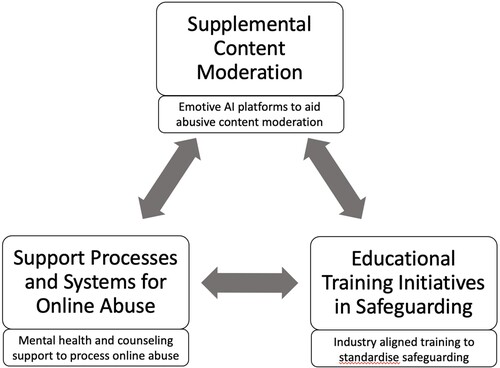

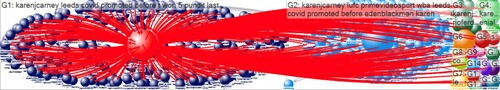

Research question one asked how the online network formed during a trigger event. Social network analysis within NodeXL provided a visualisation of the network to identify key actors and the spread of information (Hambrick, Citation2012). Listed in , the network identified two distinct groups – one group that formed around KC and another group connected to Leeds United FC. Additionally, NodeXL provided measurements that indicate key actors and roles within a network called in-degree, out-degree, and betweenness centrality.

Figure 1. Groups and influence within KC Trigger Event Network.

Note. Size of sphere indicating importance.

Betweenness centrality measures how many times a node (person) connects individuals within the network (Iacobucci et al., Citation2017). During this trigger event, KC’s betweenness centrality was 306,359. Within Twitter, connections are made through a directed message with the ‘@’ symbol. To form a connection, a tweet would have employed KC’s username (i.e. @karenjcarney) and that of another account. Leeds United FC had the second highest betweenness centrality, with a value of 15,120. Prime Videosport had the third highest betweenness centrality with 11,661, while West Bromwich Albion had the fourth highest betweenness centrality with 10,178.

As referenced in , the visualisation highlighted the formation of two distinct groups around KC and Leeds United FC. While it may appear that both KC and Leeds United FC had a small influence within their groups, their role in the network during the trigger event was large. This is particularly applicable to KC, as with a betweenness score of 306,359, she connected the entire network of actors during the trigger event who would have otherwise existed independently. These connections enabled by directed messages (i.e. @karenjcarney) are thus representative of the volume of content produced during the trigger event referencing KC and other actors.

Centrality was defined by Freeman (Citation1978) as being ‘in the thick of things’ (p. 219) or the potential for visibility or activity regarding communication. In-degree centrality is the number of links on a node, or the amount of in-coming activity. Specific to this event, it was measured by incoming direct messages (i.e. tweets). Results indicated KC was the most connected person with an in-degree centrality of 552. Leeds United FC had the second highest in-degree centrality of 216, while the network carrier Primevideosport had the third highest in-degree centrality of 198. Lastly, West Bromwich Albion had the fourth highest in-degree with 193.

Out-degree centrality is the number of outgoing ties or outgoing communication within a network. The four major accounts associated with the trigger event – KC, Leeds United FC, West Bromwich Albion, and Amazon Prime – had zero outgoing centrality meaning they did not directly interact with other actors during the trigger event illustrating the majority of content was produced by fans.

The individual with the highest in-degree centrality is typically at the centre of the network. Considering KC has the highest in-degree and betweenness centrality, results indicated her Twitter account was at the centre of the network and served to connect actors, facilitating the flow of information throughout the network. As such, most content – abusive or supportive – would have been visible to KC due to the directed, and perhaps targeted, nature. highlights the overarching network centrality of KC as well as the in-degree centrality pertaining to directed content, indicated by the red coloured lines.

Research question two asked what forms of virtual maltreatment were present in content? Within the full sample of 1332 tweets, 33 tweets were excluded due to lack of content, reducing the sample to 1299 (N = 1299). Utilising this sample, it was found that 81% of tweets contained virtual maltreatment (n = 1050), while 19% of tweets did not (n = 249). Examination of the 1050 tweets (81%) that contained virtual maltreatment, 96% of maltreatment was direct (n = 1008), and 4% was indirect (n = 42). Descriptive analysis of the tweets containing maltreatment indicated the most prevalent category was emotional maltreatment (i.e. negative emotional or psychological reactions) in 87% (n = 914) of tweets. The second most frequent form of virtual maltreatment was discriminatory maltreatment, found in 12% (n = 126) of tweet content. Physical maltreatment (0.7%, n = 7), and sexual maltreatment (0.2%, n = 3), which relate to discussion of physical attributes or sexual threats of violence, were also uncovered in tweet content, however, at much lower levels. Within the discriminatory maltreatment category are the sub-types of gender, race, sexual orientation, religion, and disability. In the 126 tweets that were coded as discriminatory maltreatment, 99% (n = 125) were gender discriminatory and 1% (n = 1) was related to sexual orientation. Regarding sentiment, approximately 15% (n = 199) of tweet content was positive, 20% (n = 264) was neutral, and 65% (n = 869) were negative.

Research question three sought to examine the themes and frames present in content. From a descriptive perspective, episodic framing was employed in 90% of tweet content (n = 1198), while thematic framing was utilised in 10% of tweets (n = 133). Themes included game commentary, questioning, general excitement, criticism, disagreement, disrespect, challenges to gender equity, belittling, ridicule, football-related gender norms, physicality, praise and support, and silencing. Data reduction and constant comparison with axial coding of themes resulted in five frames emerging. These frames were general commentary, critical commentary, humiliation and shaming, gender tropes, and support and defence. outlines data reduction from themes to frames and the associated timeframe during the trigger event, illustrating how themes and frames emerged and evolved.

Table 2. Themes and frames by time.

General commentary

The first frame that emerged was general commentary, which consisted of three themes: game commentary, general excitement, and questioning. Tweets representative of this frame occurred in the very early stages of the trigger event. The match began at 19:00 GMT, with most of these tweets occurring between the start and end of the match at 21:00 GMT. The general commentary frame allowed individuals to express their fandom, overall excitement, and general opinions for the match, and were ancillary to the trigger event. The themes of game commentary and general excitement were broad in nature and related to in-game action. For example, the game commentary theme included statements such as ‘@karenjcarney @WBA @LUFC @primevideosport Quite happy with that 1st half More of the same in the 2nd please’. The questioning theme offered individuals the chance to interact with KC and question the validity of her overall game commentary, but did so with a neutral tone. To illustrate, a fan questioned commentary regarding the goalkeeper,

@karenjcarney & @jf9hasselbaink having a go at @MeslierIllan on Amazon. I think that’s very harsh tbh. In fact, I’d even say he’s been one of our stand out performers. He’s 20 and is a first choice @premierleague GK with 5 clean sheets.

A key feature within tweets representative of this frame was sentiment, which was either positive or neutral due to the timing within the trigger event, and thus, did not contain virtual maltreatment. The tweets within this frame are crucial to establish a baseline for sentiment prior to the trigger event and are attributed to the timing of KC’s comments, which were delivered in the post-match commentary and tweeted by Leeds United FC. Following the Leeds United FC tweet, the framing within content shifted to the second frame critical commentary.

Critical commentary

The second frame of critical commentary included the themes of disagreement, criticism, disrespect, and challenges to gender equity and illustrated a shift to negative sentiments within tweet content which contained forms of virtual maltreatment. Although Leeds United have since deleted the tweet, piecing together various media commentary on the incident enabled a time frame estimate for the tweet from the end of the match at 21:00 GMT to 21:20 GMT. As KC’s comments were proliferated on Twitter by Leeds United to their more than 600,000 followers, the two themes of disagreement and criticism emerged shortly after at approximately 21:25 GMT.

The disagreement theme was presented as more ‘facts’ based rebuttal, while the criticism theme was employed by fans to not only challenge KC’s statement but included personalised forms of criticism relating to a lack of knowledge or research by KC. It is within these two themes that negative sentiments began to emerge. One tweet that was representative of the disagreement theme included ‘@karenjcarney That is just lazy Karen, Leeds had won 5 in a row before the lockdown, it nearly cost us promotion not gained us it, really do not know where you are coming from’. One tweet symbolic of the criticism theme that demonstrated a tonal shift included ‘@karenjcarney you have absolutely no idea what you are talking about. If you are going to be a pundit at least study what you are talking about. We won the Championship by 10 pts’. As the trigger event progressed, these themes evolved quickly to the disrespect and challenges to gender equity themes, through reframing of content with increased emotional gendered sentiments at approximately 21:35 GMT.

Within the disrespect theme, fans shifted from criticism directed at KC and internalised her criticism of the team as a personalised attack on their fandom, resulting in more emotive content demonstrated through insults and demands for an apology. For example, ‘@karenjcarney think you need to look back at what you said last night! Us Leeds fans are waiting for an apology! #WBALEE #AmazonPrime #PremierLeague #LeedsUnited #COVID1D’. The challenges to gender equity theme incorporated the sense of personal affront and manifested it into questioning KC’s abilities and qualifications as a pundit, reducing her employment to diversity and equity agendas or quotas. The following Tweet demonstrated this theme.

@karenjcarney you only have an MBE and a pundit job because of what is between your legs. You are the equivalent of a white apartheid era S.African. I played against you when we were 13 and we rinsed you. Do you have no conscience?

Within the critical commentary frame, tweet content was indicative of emotional virtual maltreatment, which is designed to cause psychological stress through personalised attacks on KC. The two themes of disagreement and criticism (i.e. 21:25 GMT) intensified further during the trigger event and were reframed rapidly, resulting in the emergence of disrespect and challenges to gender equity (i.e. 21:35 GMT) themes. These themes included more instances of emotional and discriminatory gendered virtual maltreatment through referencing gender-hiring practices.

Humiliation and shaming

The third frame was humiliation and shaming and was employed by fans as a retribution tactic and to redirect the negative emotions with the fandom elicited by KC’s comment. This frame included the themes of belittling and ridicule, a further emotional extension of the disagreement, criticism, disrespect, and challenges to gender equity themes. Themes within this frame began to appear within the trigger event timeline around 21:50 GMT, approximately two hours after the original tweet, allowing emotion to build as the trigger event progressed. The belittling theme sought to devalue or dismiss KC’s ability as a pundit through comments such as ‘@karenjcarney I’d expect that statement to be retracted and excused, as it was stupid and borderline offensive. If you want to be taken serious in this business, you need to do better!’ Emotional virtual maltreatment was building during the trigger event at this time with more than 400 (n = 402) coded instances appearing. The second theme ridicule utilised humour as a mocking tactic to further diminish KC’s perceived ability. For example, ‘@karenjcarney you been smoking something tonight Karen LEEDS only won the league because of covid PMSL’.

As the trigger event progressed and emotions continued to build, discriminatory virtual maltreatment with a gendered component became more frequent within these two themes, as KC’s positioning as an out-group (i.e. women) intensified. This was illustrated in the following tweet of, ‘@karenjcarney You are a waste of space. Definitely lady punditry. You shouldn’t be on the TV at all. My dogs would give the audience a better insight’. The heightened emotional elements associated with humiliation and shame also potentially served the purpose to force KC to remove herself from the platform, or to discontinue her work as a pundit.

Gender tropes

The fourth frame gender tropes included the themes of football-related gender norms and physicality. In a time period from 22:00 GMT to 00:00 GMT, which was two to four hours after KC’s comments were tweeted, the number of discriminatory gendered tweets nearly doubled from 59 (n = 59) to 100 (n = 100). Football-related gender norms were employed by fans to further enforce in-group (i.e. fans/men) and out-group (i.e. KC/women) affiliations as justification for the abusive comments. Illustrative within comments such as ‘@karenjcarney promoted because of covid! Get back in the kitchen love’, was the socio-normative views that women do not belong in football, and KC’s ‘incorrect’ comments within punditry reinforced these views. Additionally, socially ‘approved’ gender roles were heavily referenced within tweet content to demonstrate women’s ‘true’ position in society – the home – rather than in football within content such as ‘@karenjcarney @WBA @LUFC @primevideosport There’s a good lass. Got a sink full of pots you can start on & pile of ironing chop chop’. Tweets became more aggressive and overt in their gendered discriminatory content as emotion heightened, with, ‘@karenjcarney stick to what women do best get back to the kitchen, cos u talk shit on tv’ demonstrative of the progression within the trigger event.

The theme of physicality was representative of fans’ utilisation of attacks on KC’s physical appearance and continued discriminatory gendered virtual maltreatment. By criticising KC’s physical attributes, fans further attempted to employ silencing tactics and remove her from the platform or as a pundit as a consequence of her ‘incorrect’ views and out-group affiliation. One example of this theme, ‘@karenjcarney Stupidly meets diversity good at football now expert on COVID pity that you are not expert on eye make up’ demonstrated this tactic. A small but highly abusive sample of content within this theme included overtly sexualised content ‘@karenjcarney looks likes she’s just taken a cum shot to the face #WBALEE’ demonstrated the vitriol associated with gendered abuse received. Due to the amount of online abuse and progressive increase emotional and discriminatory abuse within content, a final frame emerged within the trigger event that was intended to counter these sentiments and delineate fandom in-group and out-group affiliations.

Support and defense

The fifth and final frame was support and defense, which included the themes praise and support and silencing. These themes emerged approximately 03:30 GMT on 30 December continuing through to 19:00 GMT as the trigger event progressed into the next day. With the number of emotionally and gendered discriminatory tweets directed at KC increasing, a smaller number of Leeds fans began to call out the abuse and offer words of support to KC within the theme praise and support. Content within this theme praised KC’s ability as pundit to counter the criticism within the belittling or ridicule themes and offered support through the acknowledgment of abuse, calling it out as misogyny. One example of this theme included

@karenjcarney I am a Leeds Utd supporter, and a football supporter. I am so sorry that you’ve had to endure the misogyny that has been thrown at you. You offered an opinion, and you should not have to tolerate the abuse it generated.

The second theme, silencing encouraged KC to ignore the posts by ‘not feeding trolls’ and ‘staying strong’. While intending to be supportive this messaging encouraged larger socio-gendered norms of behavioural compliance that persist - specifically that when women make a comment that is deemed to be ‘incorrect’ it is better to stay silent and weather the storm. One example which illustrates this silencing tactic was, ‘@karenjcarney You were spot on with your comments regarding Leeds’ promotion. Ignore the abusers – you are a terrific pundit’.

Discussion and conclusion

The current research has examined the formation and type of gendered online abuse faced by a female sport journalist in relation to a trigger event and identified how a range of themes evolved in the 24 hours following the trigger event. Analysis identified five main themes employed by social media users within this trigger event; general commentary, critical commentary, humiliation and shaming, gender tropes, and support and defence. Critically, the frames change throughout the course of the trigger event and build to their peak of abusive content, which was emotional and discriminatory in nature. The netnography and thematic analysis undertaken exposes the types of the online abuse targeted towards sports journalist KC, through a sports-related trigger event, and how the abuse evolved through that trigger event. Both episodic and thematic frames were evident, and they became reciprocal as discussion of KC’s comments on Twitter continued throughout the night.

Theoretical implications

This paper theoretically contributes to the literature employing self-categorisation theory within sport research (e.g. Billings et al., Citation2015; Claringbould & Knoppers, Citation2007; Wicker et al., Citation2022) by applying it in a novel way to determine how it shaped and influenced online abuse within sport trigger events. Critical to understanding how trigger events form and evolve around key actors, the current research visualised the level of self-categorisation related to self as a member of a social ingroup pitted against other groups (Turner et al., Citation1987). Additionally, it demonstrated how depersonalisation within in-groups contributed to online abuse, reinforcing group prototypes, cohesion, and influence. Supporting previous findings, results revealed how the key actors within the trigger event were divided by gender (Cunningham, Citation2004), with the out-group (i.e. a female pundit and her supporters), forming due to socio-normative views held by the in-group and hegemonic masculinity associated with the male-oriented topic of football (Claringbould & Knoppers, Citation2007; Knoppers & Anthonissen, Citation2005). These group dynamics were the foundation for misogyny, sexism, and abuse directed toward KC, continuing the trend of this behaviour aimed at women within social media (Adams, Citation2018; Chen et al., Citation2020; Demir & Ayhan, Citation2022; Everbach, Citation2018; Kavanagh et al., Citation2019; Luqiu, Citation2022; Posetti et al., Citation2021; Everbach, Citation2018). Online abuse is a complicated, layered issue, which can be examined from the individual (psychological), group (sociological), and platform (technological) perspectives. What roles these perspectives play in the resulting abuse is difficult to untangle and isolate, making this a complex but vital area to explore. The current research strived to examine and understand the sociological perspective, demonstrating how individuals – the collective of humans behind the computers – participate in the online abuse of another due to group cohesion and dynamics. It also highlights how the platform acts as a mechanism to perhaps increase the social elements of self-categorisation that can facilitate abuse, specifically the community building function, which in this case was employed to amplify toxicity.

The current research also extends the literature related to the experiences of female journalists within online spaces, specifically the underexplored area of female sports journalists/pundits within football (Antunovic, Citation2019; Bowes et al., Citation2023; Everbach, Citation2018; Hardin & Shain, Citation2005; Meân & Fielding-Lloyd, Citation2021; Miller & Miller, Citation1995; Mudrick & Lin, Citation2017). The exploration of the timed component within the trigger event adds nuance to how the specific types of virtual maltreatment KC experienced evolved, building in vitriol the longer trigger events progressed. As the emotional element within content is heightened, an abusive echo chamber and ‘waves’ of online abuse emerge. Through timeline analysis, it was illustrated how selected members of the in-group began the progression of abusive content, and then through depersonalisation and group norms, other members contributed to the abuse. The result is sustained, highly emotionally abusive and discriminatory rhetoric designed to inflict psychological distress on an individual until the member of the out-group apologises or removes themselves from the platform. Further, the employment of Iyengar’s (Citation1991) framework for episodic and thematic framing revealed how in-group and out-group dynamics were justified throughout the trigger event via messaging that contained emotional or discriminatory virtual maltreatment.

Episodic framing was focused on KC’s comments on Leeds United and her abilities as a journalist, namely that she had not fulfilled the requirements to be a successful journalist (i.e. doing the ‘work’ or ‘research’) by making a comment that didn’t align with apparently relevant statistics. Therefore, she needed to be ‘corrected’ by the ingroup – Leeds fans - which was commonly done via the presentation of ‘facts’, including Leeds United’s accrued league points and their match record just prior to the first COVID-19 lockdown in the UK. The attribution of responsibility toward KC by social media users that night framed their critical comments towards her as warranted, as she was positioned as undeserving of ingroup membership, and not entitled to be treated as a credible journalist within the context of men’s football.

Initially, the presentation of facts may appear to construct critical comments as neutral and ‘fair’, rather than harmful. However, we must examine the function that neutral language serves in positioning the tweet authors, whilst KC is firmly positioned as an undeserving out-group member. The presentation of objective, and seemingly relevant, ‘facts’ in this data positions the abusive tweet authors as knowledgeable, entitled in-group members as they employ what Potter (Citation1996) terms the empiricist repertoire. By giving some basis to their claims ‘the support is built up by constructing the facts, the record, the evidence, as having its own agency’ (p. 158) which is independent of the tweet authors themselves and any wider perceptions they may have about women working in the traditionally male-dominated space of professional English football. The value of the detail presented in those tweets enabled their authors to be positioned as credible contributors and fans and served to protect them from being accused of being subjectively motivated as Leeds fans.

The framings described above provided the foundation for more thematic framings which evolved as the night progressed. The thematic frames that presented broader social attitudes towards women in football really came to the fore in the themes of disrespect, challenges to gender equity, humiliation and shaming, and gender tropes. Within these themes, KC’s credibility continued to be questioned as her ‘incorrect’ comments were commonly attributed to her personal character and perceived issues of diversity hiring. The attacks became more vitriolic and constituted emotional virtual maltreatment (Kavanagh et al., Citation2016) in their intention to be psychologically distressing.

Whilst messages of support for KC were evident, these only came through towards the end of the data collection period as a reaction to the scale of abuse directed towards her that positioned KC as ‘doubly deviant’. Similarly, to other studies of gendered online abuse (Lumsden & Morgan, Citation2017), KC is presented as deviant in terms of both her gender (a woman who was not conforming to conventional heterosexual femininity) and her occupation (as a woman entering a male-dominated workplace). It is important to note that Leeds United triggered the subsequent abuse that KC faced by presenting the allegedly relevant ‘fact’ that the team had won their league by 10 points and indicating KC’s perceived incompetence in her occupation. Our timeline evidences that Leeds United’s tweet had a directly amplifying impact on the scale, and tone, of abuse that KC received, establishing her as an out-group and placing her as the central point within the network. Within the trigger event, their tweet fuelled social media users’ anger which, as Kilvington (Citation2020) has shown, results in lowered social awareness, exacerbates automatic prejudice (in this case based on gender) and leads to a proliferation of hate speech.

Managerial implications

From a practical perspective, the current research has uncovered the nature and formation of trigger events on social media within a gendered context. The combined methodology of netography, quantitative and qualitative analysis has provided understanding of how (key actors, pace, and networks), and what (nature and type), abuse was targeted towards a female sports journalist. It has demonstrated evidence of the ways in which social media abuse evolved via shifting framings (episodic and thematic) and themes (from critical, to abusive, to supportive). This is critical from a managerial perspective as understanding how these events progress can lead to organisational education to identify potential flashpoints in sporting competitions that could result in trigger events, and mitigate abusive content before the trigger event builds.

The real-life consequences of such abusive social media content (both practical and cultural) should not be underestimated. There are potential mental health implications for its victims, as well as practical consequences should they decide to withdraw from social media (as KC has) and the potential promotional and branding benefits that it offers for sport journalists’ careers (Everbach, Citation2018). There needs to be increased awareness, via safeguarding practices and educational initiatives, of the antecedents and implications of trigger events in sports. The increased understanding of trigger events and their characteristics can inform future social media and safeguarding strategies from a managerial perspective for a range of stakeholders, including professional sports clubs. Specifically, organisations could develop strategic plans and policies to identify abusive content early within a trigger event, such as when emotional content became prevalent early within this trigger event, and then communicate to individuals that abusive content will not be tolerated, demonstrating support, and mitigating further abuse.

The current research also demonstrates how pervasive online abuse remains, even with content moderation policies in place. The platform (i.e. Twitter) bears the responsibility for content moderation, however, the volume of data produced on Twitter makes it difficult to completely prevent these situations from occurring. Twitter needs to do far more to improve its content moderation with stricter guidelines and new moderation models employing generative, emotion-based AI to better filter abusive content. This, however, is still a reactive, macro-level solution in the safeguarding and protection of sport stakeholders. If an online presence is a necessary component of a sport stakeholder’s professional responsibilities, then proactive, meso- and micro-organisational policies and financial support should also be provided to protect sport stakeholders. Thus, a proposed triangular approach to aid in protection against online abuse is presented in . This approach consists of organisational employment of supplemental content moderation for stakeholder accounts which employ new, generative AI-based models that proactively filter content so abuse is not seen, educational training initiatives and safeguarding practices for key sport stakeholders (i.e. athletes, sports journalists/pundits, coaches, agents), and the establishment of support processes and policies by media organisations, players unions, sport federations, and sports committees for stakeholders and athletes when subjected to online abuse. While the first two approaches are proactive, it is recognised the latter is reactive, however, this component is critical to ensure athletes and all stakeholders feel supported and organisations have a clear structure to utilise and share best practices to heighten safeguarding.

Limitations and future directions

The current research is not without limitations. First, a smaller sample size was utilised for the netnography and thematic analysis of content, which could impact the understanding of the scale of online abuse. Future research could employ a ‘big data’ approach with data scraping and sentiment analysis. This could also include the VADER model, a lexicon-based sentiment analysis library designed for social media text to identify emotion within online content. Second, a limited timeframe of 24 h post-tweet was employed to bind the trigger event. While necessary to understand the volatility of content within this context, it does not allow for longitudinal analysis of online abuse. Thus, future research could include analysis of multiple trigger events, combining data scraping with content analysis to document online abuse over a series of years and highlight the necessity of action. Third, the current research was unable to ascertain the impact of online abuse, which remains largely unexplored. Further research could complement the current research by examining the experiences of key sporting stakeholders towards abuse through interviews or focus groups, as it is important to ensure that multiple perspectives are understood (Hayes et al., Citation2020). This would enrich understanding of the potentially negative impacts of online spaces on how those with marginalised identities in sport (based on gender, ethnicity, and so on) are discursively positioned and put at risk.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, C. (2018). ‘They go for gender first’. The nature and effect of sexist abuse of female technology journalists. Journalism Practice, 12(7), 850–869. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2017.1350115

- Antunovic, D. (2019). ‘We wouldn’t say it to their faces’: Online harassment, women sports journalists, and feminism. Feminist Media Studies, 19(3), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2018.1446454

- Awan, I. (2014). Islamophobia on Twitter: A typology of online hate against Muslims on social media. Policy & Internet, 6(2), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/1944-2866.POI364

- Awan, I., & Zempi, I. (2016). The affinity between online and offline anti-Muslim hate crime: Dynamics and impacts. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 27, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2016.02.001

- BBC Sport. (2021). Social media abuse has changed me. Karen Carney BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/56959962

- Billings, A. C., Burch, L. M., & Zimmerman, M. H. (2015). Fragments of us, fragments of them: Social media, nationality and US perceptions of the 2014 FIFA World Cup. Soccer & Society, 16(5-6), 726–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2014.963307

- Bisset, S. (2022). Outraged – online abuse [film]. UEFA.

- Bliuc, A.-M., Faulkner, N., Jakubowicz, A., & McGarty, C. (2018). Online networks of racial hate - A systematic review of 10 years of research on cyber-racism. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.05.026

- Bowes, A., Matthews, M., & Long, J. (2023). Critical feminism and football pundits: Calm down … it’s just a woman talking football. In W. Roberts, S. Whigham, A. Culvin, & D. Parnell (Eds.), Critical issues in football (pp. 124–136). Routledge.

- Boyd, D. (2011). White flight in networked publics? How race and class shaped American teen engagement with MySpace and Facebook. In L. Nakamura & P. Chow-White (Eds.), Race after the internet (pp. 203–222). Routledge.

- Braithwaite, A. (2014). ‘Seriously, get out’: Feminists on the forums and the war(craft) on women. New Media & Society, 16(5), 703–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813489503

- Brown, C. (2009). WWW.HATE.COM-White Supremacist Discourse on the internet and the construction of Whiteness Ideology. Howard Journal of Communications, 20(2), 189–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/10646170902869544

- Busby, M. (2019). Manchester United’s Marcus Rashford target of racist abuse on Twitter. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/football/2019/aug/24/manchester-uniteds-marcus-rashford-target-of-racist-abuse-on-twitter

- Chen, G. M., Pain, P., Chen, V. Y., Mekelburg, M., Springer, N., & Troger, F. (2020). ‘You really have to have a thick skin’: A cross-cultural perspective on how online harassment influences female journalists. Journalism, 21(7), 877–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884918768500

- Claringbould, I., & Knoppers, A. (2007). Finding a ‘normal’ woman: Selection processes for board membership. Sex Roles, 56(7–8), 495–507. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9188-2

- Cleland, J. (2018). Sexuality, masculinity and homophobia in association football: An empirical overview of a changing cultural context. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 53(4), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690216663189

- Cunningham, G. B. (2004). Strategies for transforming the possible negative effects of group diversity. Quest (Grand Rapids, MI ), 56(4), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2004.10491835

- Demir, Y., & Ayhan, B. (2022). Being a female sports journalist on Twitter: Online harassment, sexualization, and hegemony. International Journal of Sport Communication, 1(aop), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2022-0044

- Denzin, N. (1989). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Doyle, J. P., Su, Y., & Kunkel, T. (2022). Athlete branding via social media: Examining the factors influencing consumer engagement on Instagram. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(4), 506–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1806897

- Dudani, A. (2021). Egyptian Olympic swimmer Farida Osman stands up for herself and other athletes amid backlash. Vogue. https://en.vogue.me/culture/egyptian-olympian-swimmer-farida-osman-online-abuse/

- Everbach, T. (2018). I realized it was about them … not me’: Women sports journalists and harassment. In R. J. Vickery & T. Tracy Everbach (Eds.), Mediating misogyny-: Gender, technology, and harassment (pp. 131–149). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fenton, A., Gillooly, L., & Vasilica, C. M. (2021). Female fans and social media: Micro-communities and the formation of social capital. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1868546

- Fleiss, J. L. (1971). Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychological Bulletin, 76(5), 378–382. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0031619

- Fox, J., Cruz, C., & Lee, J. Y. (2015). Perpetuating online sexism offline: Anonymity, interactivity, and the effects of sexist hashtags on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 52, 436–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.024

- Freeman, L. C. (1978). Centrality in networks: Conceptual clarification. Social Networks, 1(3), 215–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/0378-8733(78)90021-7

- Geurin, A. N. (2017). Elite female athletes’ perceptions of new media use relating to their careers: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Sport Management, 31(4), 345–359. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0157

- Geurin, A. N., & Naraine, M. L. (2020). 20 years of Olympic media research: Trends and future directions. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 2, 129. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2020.57249

- Goffman, E. (1974). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience. Harvard University Press.

- Hambrick, M. E. (2012). Six degrees of information: Using social network analysis to explore the spread of information within sport social networks. International Journal of Sport Communication, 5(1), 16–34. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.5.1.16

- Hardin, M., & Shain, S. (2005). Female sports journalists: Are we there yet? ‘No’. Newspaper Research Journal, 26(4), 22–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/073953290502600403

- Hayes, M., Filo, K., Geurin, A., & Riot, C. (2020). An exploration of the distractions inherent to social media use among athletes. Sport Management Review, 23(5), 852–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.12.006

- HM Government. (2019). Online Harms White Paper. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/793360/Online_Harms_White_Paper.pdf

- Iacobucci, D., McBride, R., Popovich, D., & Rouziou, M. (2017). In social network analysis, which centrality index should I use? Theoretical differences and empirical similarities among top centralities. Journal of Methods and Measurement in the Social Sciences, 8(2), 72–99. http://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3425975

- Iyengar, S. (1991). Is anyone responsible? How television frames political issues. University of Chicago Press.

- Jane, E. A. (2014a). Your an ugly, whorish, slut. Understanding E-bile. Feminist Media Studies, 14(4), 531–546. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2012.741073

- Jane, E. A. (2014b). ‘Back to the kitchen, cunt’: Speaking the unspeakable about online misogyny. Continuum, 28(4), 558–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2014.924479

- Janta, H., Lugosi, P., & Brown, L. (2014). Coping with loneliness: A netnographic study of doctoral students. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 38(4), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2012.726972

- Kavanagh, E., Jones, I., & Sheppard-Marks, L. (2016). Towards typologies of virtual maltreatment: Sport, digital cultures & dark leisure. Leisure Studies, 35(6), 783–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2016.1216581

- Kavanagh, E., Litchfield, C., & Osborne, J. (2019). Sporting women and social media: Sexualization, misogyny, and gender-based violence in online spaces. International Journal of Sport Communication, 12(4), 552–572. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2019-0079

- Kavanagh, E., Litchfield, C., & Osborne, J. (2022). Social media, digital technology and athlete abuse. In J. Sanderson (Ed.), Sport, social media, and digital technology (pp. 185–204). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Kearns, C., Sinclair, G., Black, J., Doidge, M., Fletcher, T., Kilvington, D., Liston, K., Lynn, T., & Rosati, P. (2022). A scoping review of research online hate and sport. Communication & Sport, 0(0), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/21674795221132728

- Keum, B. T., & Miller, M. J. (2018). Racism on the internet: Conceptualization and recommendations for research. Psychology of Violence, 8(6), 782. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000201

- Kilvington, D. (2020). The virtual stages of hate: Using Goffman’s work to conceptualise the motivations for online hate. Media, Culture & Society, 43(2), 256–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720972318

- Kilvington, D., & Price, J. (2019). Tackling social media abuse? Critically assessing English football’s response to online racism. Communication & Sport, 7(1), 64–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167479517745300

- Kilvington, D., & Price, J. (2021). The ‘beautiful game’ in a world of hate: Sports journalism, football and social media abuse. In R. Domeneghetti (Ed.), Insights on reporting sports in the digital age (pp. 104–119). Routledge.

- Knoppers, A., & Anthonissen, A. (2005). Male athletic and managerial masculinities: Congruencies in discursive practices? Journal of Gender Studies, 14(2), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589230500133569

- Kozinets, R. (2010). Netnography, doing ethnographic research online. Sage.

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics, 33(2), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529786

- Leeds United FC. [@LUFC]. (2020). Promoted because of Covid. Won the League by 10 points. Hi @primevideosport [Tweet]. Twitter.

- Litchfield, C., Kavanagh, E., Osborne, J., & Jones, I. (2018). Social media and the politics of gender, race and identity: The case of Serena Williams. European Journal for Sport and Society, 15(2), 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/16138171.2018.1452870

- Liu, Y. (2016). The development of social media and its impact on the intercultural exchange of the Olympic Movement, 2004-2012. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 33(12), 1395–1410. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2017.1285285

- Lumsden, K., & Morgan, H. (2017). Media framing of trolling and online abuse: Silencing strategies, symbolic violence, and victim blaming. Feminist Media Studies, 17(6), 926–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2017.1316755

- Luqiu, L. R. (2022). Female journalists covering the Hong Kong protests confront ambivalent sexism on the street and in the newsroom. Feminist Media Studies, 22(3), 679–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2020.1842481

- McCarthy, B. (2022). ‘Who unlocked the kitchen?’: Online misogyny, YouTube comments and women’s professional street skateboarding. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 57(3), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1177/10126902211021509

- Meân, L. J., & Fielding-Lloyd, B. (2021). 17 football, gender, and sexism: The ugly side of the world’s beautiful game. In M. Butterworth (Ed.), Communication and sport (pp. 313–332). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Miller, P., & Miller, R. (1995). The invisible woman: Female sports journalists in the workplace. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 72(4), 883–889. https://doi.org/10.1177/107769909507200411

- Mountjoy, M., Brackenridge, C., Arrington, M., Blauwet, C., Carska-Sheppard, A., Fasting, K., … Budgett, R. (2016). International Olympic Committee consensus statement: Harassment and abuse (non-accidental violence) in sport. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 50(17), 1019–1029. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096121

- Mudrick, M., & Lin, C. A. (2017). Looking on from the sideline: Perceived role congruity of women sports journalists. Journal of Sports Media, 12(2), 79–101. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsm.2017.0011

- Nakayama, T. K. (2017). What’s next for whiteness and the Internet. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 34(1), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295036.2016.1266684

- Niesen, J. (2021). In a divided US, it’s no surprise some see Simone Biles as a villain. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2021/jul/28/simone-biles-withdrawal-olympics-gymnastics-tokyo-media-reaction

- Posetti, J., Shabbir, N., Maynard, D., Bontcheva, K., & Aboulez, N. (2021). The chilling: Global trends in online violence against women journalists. United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF).

- Potter, J. (1996). Representing reality: Discourse, rhetoric and social construction. Sage.

- Reuters. (2020). Soccer-‘Promoted because of COVID’? Leeds hit back at pundit. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/instant-article/idUKL1N2JA0AW

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Sanderson, J., & Weathers, M. R. (2020). Snapchat and child sexual abuse in sport: Protecting child athletes in the social media age. Sport Management Review, 23(1), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.04.006

- Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of inter-group relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Talbot, A. (2021). Tokyo 2020 gold medal-winning archer An San is ridiculed as a ‘feminist’ at home in South Korea for having short hair – so thousands of women share pictures of their own short locks in a mass show of online support. The Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sport/olympics/article-9839817/Support-South-Korean-Olympian-San-received-online-abuse-hairstyle.html

- The Athletic. (2021). UEFA joins English football’s social media boycott. https://theathletic.com/news/football-uefa-social-media-blackout/k7VfuGDvNis6/

- The Guardian. (2021). Karen Carney reveals abuse on social media led her to suicidal thoughts. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/football/2021/may/01/KC-KC-reveals-abuse-on-social-media-led-her-to-suicidal-thoughts

- Thorpe, H. (2017). Media representations of women in action sports: More than ‘sexy bad girls’ on boards. In H. Thorpe (Ed.), The routledge companion to media, sex and sexuality (pp. 279–289). Routledge.

- Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M., & Kuss, D. J. (2021). Perceived challenges and online harms from social media use on a severity continuum: A qualitative psychological stakeholder perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3227. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063227

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Blackwell.

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (2012). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Blackwell.

- Turner, J. C., & Reynolds, K. J. (2010). The story of social identity. In T. Postmes & N. R. Branscombe (Eds.), Rediscovering social identity (pp. 13–32). Psychology Press.

- Vale, L., & Fernandes, T. (2018). Social media and sports: Driving fan engagement with football clubs on Facebook. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 26(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2017.1359655

- Wicker, P., Feiler, S., & Breuer, C. (2022). Board gender diversity, critical masses, and organizational problems of non-profit sport clubs. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(2), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1777453

- Williams, M. L., Burnap, P., Javed, A., Liu, H., & Ozlap, S. (2020). Hate in the machine- anti-Black and anti-Muslim social media posts as predictors of offline racially and religiously aggravated crime. The British Journal of Criminology, 60(1), 242–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz064

- World Athletics. (2021). World Athletics publishes online abuse study covering Tokyo Olympic Games. World Athletics. https://worldathletics.org/news/press-releases/online-abuse-study-athletes-tokyo-olympic-game