Brand management has become centrally embedded in the sport management literature across the past several decades. The acceleration of scholarship has coincided with increased globalisation, commercialisation, and consumer interest, turning sport into a multi-billion-dollar industry (Ströbel & Germelmann, Citation2020). As such, the value of the global sports industry surpassed $500 billion (USD) in 2023 and is predicted to exceed $620 billion (USD) by 2027 (The Business Research Company, Citation2023). Yet, with new opportunities come new challenges, such as navigating a complex and saturated marketplace. In response, sport brands must adopt strategic approaches to their creation, positioning, and on-going management (Manoli, Citation2022). Recent research has adopted this perspective shedding light on how sport brands can be successfully created and managed (Manoli, Citation2018; Ströbel & Germelmann, Citation2020), whilst also predicting how the sport industry may evolve in the future. Central to this discourse is the increased focus which is being placed on individuals involved in sport, and their influence on its production, distribution, and consumption (Baker et al., Citation2022; Kunkel & Biscaia, Citation2020).

This special issue is consequently dedicated to examining individual-level sport brands (ILSBs), the dynamic environment they operate within, and the numerous stakeholders and communication channels that impact their development. Drawing on extant work which has focused on understanding athletes as human brands (Carlson & Donavan, Citation2013), we conceptualise ILSBs to encompass an expanded array of individuals involved in the sport ecosystem. The articles contained in this special issue explore the brand management linked to some of these ILSBs and provide a basis to help understand how ILSBs are managed and evaluated by consumers.

The first article by Hu et al. (Citation2023) outlines findings from a phenomenological qualitative study focused on understanding the motives and strategies used to market elite disability sport athletes. The study explores this from the perspective of professional agents, who represent an important yet understudied stakeholder, and identifies key opportunities and challenges encountered by agents tasked with brand building for elite athletes with disabilities (EAwD). Findings demonstrate the agents’ tendency to promote EAwD based on their life story and using social media, with the authors outlining key implications for practitioners to expand this approach.

The second article by Fujak et al. (Citation2023) examines athlete perspectives on product innovations occurring in their sport. This work explores Twenty20 cricket (T20), which represents a shortened, entertainment-focused version of the sport. The article demonstrates athletes acknowledged the personal benefits they receive from format adjustments and adjusted their frontstage self-presentation to service consumers’ demand for entertainment. Yet the athletes also recognised these adjustments could jeopardise their athletic performance. Thus, this article contributes to our knowledge on ILSBs from the athletes’ perspective by providing insights on the behavioural changes athletes experience when the organisational brands with which they are associated innovate their core product offerings.

The third article by Bredikhina et al. (Citation2023) builds on the web of social relationships involving human brands to examine how an athlete’s personal life and romantic relationship influenced perceptions of their brand. The authors thematically analysed comments provided on Facebook posts by a media company related to a male celebrity athlete and his then-fiancée. Findings demonstrate complex and polarised discourses that sought to either reaffirm or question the relationship’s authenticity. Evaluations of the athlete were linked with issues of gender, status, and race, whereas his romantic partner was positioned as an asset to inform the athlete’s brand image. This study demonstrates how personal life stories and romantic relationships are important components that contribute to how consumers perceive athletes. This work offers a holistic view of brand dynamics and demonstrates how the social and industry influences on a human brand situated within a socioecological system must be explored in concert, rather than in isolation.

The fourth article by Mogaji and Nguyen (Citation2023) examines the impact of the intersection of race, gender, and nationality on the self-branding strategies employed by Black British sportswomen. Using interviews and thematic analysis, the authors find these women build their brands by being exceptional, seeking partnerships, retaining their personal values, communicating their distinctive experiences, and thinking beyond sport. The study applied intersectionality theory (Crenshaw, Citation1992), the human brand pyramid (Mogaji et al., Citation2022), and the model of athlete brand image (Arai et al., Citation2014) to explore how race and gender shape branding for these athletes. Shedding light on the lived experiences of Black British sportswomen, this research offers implications for athletes, agencies working with diverse talents, and sport governing bodies.

The fifth article by Noh et al. (Citation2023) examines consumers’ perceptions of two athlete brands in the context of their engagement in social and political advocacy. The authors carried out in-depth interviews employing the Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET) to garner insights into how consumer sentiments and perspectives develop. Key findings advance the utilisation of sport as a platform where social and political issues can be highlighted and the prominent ambassadorial role that athletes play in this process. By exploring these dynamics, the paper enriches our comprehension of how athlete brands are composed by both their athletic and non-athletic efforts. This paper contributes methodologically using ZMET and pinpoints unique brand associations which were linked to the two athletes studied. Noh et al. (Citation2023) posit that engagement with, and promotion of, social and political advocacy provides the potential to bolster brand equity, but also warn of possible backlash which may be encountered. This tension underscores the intricacy surrounding how consumers, and variations between subsets of consumers, evaluate athlete brands and their involvement in social and political issues.

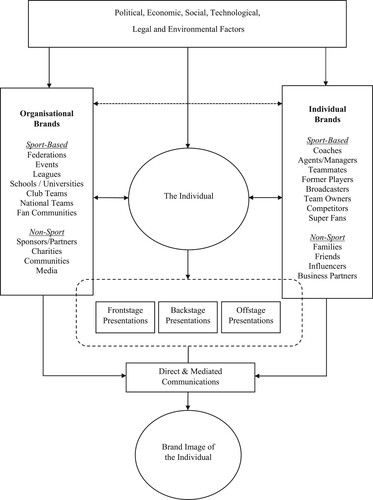

We use these special issue articles, alongside the extant literature to advance the Individual-Level Sport Brand Management Framework (ISBMF) to better understand how ILSBs are built, managed, and impacted by other brands and external factors surrounding them. The ISBMF is subsequently used to depict environmental determinants, related brands, brand image components, and communication methods that shape the consumer-based brand equity linked to ILSBs. We conclude by outlining research directions to further develop knowledge on how ILSBs can be developed and managed.

Sport brand management

Sport brands are tasked with simultaneously achieving success across their athletic domains and in their off-field capacities. Foundational research was developed via an emphasis on the former, understanding implications for consumer behaviour in the aftermath of sporting success or failure (Cialdini et al., Citation1976). Yet, the outcomes of sport contests are not controllable from a managerial perspective, which is part of the reason why they entice interest from billions worldwide (Mason, Citation1999). This realisation combined with the increased professionalisation of sport necessitated an increasingly strategic approach, and brand management became a focus for sport organisations in the late 1990s (Gladden et al., Citation2001). The transformational impact new technologies and new media have had on the sport industry have played a key role in driving both research and practice (Filo et al., Citation2015). Today, digital technologies and sport are inextricably linked, with sport stakeholders at all levels (e.g. governing bodies, federations, leagues, and teams) firmly embedding social media within their marketing strategies (Abeza & Sanderson, Citation2023).

While social media has had an undeniable impact across the breadth of the sport brand ecosystem, individual-level brands have been arguably those most impacted by new technologies (Kunkel & Biscaia, Citation2020). Social media has unlocked the potential for ILSBs to communicate directly and instantaneously with their audiences without other entities (e.g. leagues and teams) mediating the process or controlling the message. This opportunity does not replace communications coming from related leagues and teams, but provides another, more controllable and personal means of communication. As such, ILSBs can showcase insights into their professional pursuits as well as sharing insights into their lives beyond sport. These developments have enabled ILSBs to connect with global audiences and have increased their commercial appeal, whilst also establishing sport firmly in the centre of conversations surrounding community-based issues, societal trends, and causes benefitting the less fortunate (Kunkel et al., Citation2020).

Scholars demonstrate the rising influence of ILSBs, observing how related organisational-level brands (e.g. leagues) benefit from the presence of star athletes (Shapiro et al., Citation2017). Furthermore, it is important to note that ILSBs exert influence beyond the sport industry, with the inverse also being true. For example, National Women’s Soccer League (NWSL) team Angel City FC created their brand around a star-studded ownership group comprised of popular sportspeople and entrepreneurs from the non-profit, technology, and entertainment sectors (Angel City FC, Citation2023). Elsewhere, within the collegiate sport system, Name, Image, Likeness (NIL) rule changes facilitate student-athletes’ opportunities to pursue commercial deals of interest enabling these athletes and the brands they represent (e.g. team, university, sponsors) to explore new routes of collaborative brand development (Salaga et al., Citation2023). Such changes necessitate new thinking on how ILSBs can be managed today and in the future, and the current special issue articles shed some light on how this can be done. We conceptualise the ISBMF to chart the underlying processes influencing and guiding the creation of ILSBs and their brand equity. The framework is presented in and we expand on the ISBMF in the remainder of this article.

External context

The sport brand ecosystem is impacted by several political, economic, social, technological, environmental, and legal factors. These macro-level forces vary across sports and countries, but nevertheless consistently present challenges and opportunities for ILSBs and govern the processes surrounding their management. For example, changes to NIL rules in the USA required political and legal support and were also driven by social pressures arguing that student-athletes had a right to profit from their personal brands (Cocco et al., Citation2023; Su et al., Citation2023). The subsequent changes now enable athletes to collaborate with corporate brands, with deals ranging from simple one-off promotions to lucrative multi-million-dollar long-term partnerships (On3Media, Citation2023).

Although sportswomen like gymnast Olivia Dunne and basketballer Angel Reese are prominent examples of athletes with high NIL values, societal biases persist to favour men’s sport (Delia et al., Citation2022). The longstanding tendency for women’s sport to be underfunded and inadequately covered in media reporting reflect key social and economic factors that have hampered the development of women’s sport in general (Delia, Citation2020) and exacerbate the challenges facing female ILSBs more specifically (Geurin-Eagleman & Burch, Citation2016). While recent societal pressures for equal pay have spurred interest and investments in women’s sport, increasing interest rates and escalating inflation may hinder future investments in sport and negatively impact lesser-known ILSB who rely on corporate investments through sponsors or venture capitalists to fund their sports.

As detailed in this special issue, technological innovations like smartphones and social media have created opportunities for individuals in the sport industry to develop their brands. Being in control of content curation and its respective dissemination, rather than relying solely on related brands and the media to tell their story enables individuals who have traditionally not been in the spotlight, such as Black sportswomen (Mogaji & Nguyen, Citation2023) and EAwD (Hu et al., Citation2023), a platform to showcase their brands. Elsewhere, scholars have discussed the close interdependent relationship between sport and the natural environment (McCullough et al., Citation2020). Sport ecologists note how changes in climate, the implementation of sustainable practices (or lack thereof), and other related environmental factors pose pressing and urgent existential challenges to how sport may continue to operate (Cury et al., Citation2023). For instance, global temperature rises are reducing the number of cities with the required climatic conditions needed to host events like the Winter Olympics. In the face of such challenges, proactive attempts have been made by sport organisations to limit their environmental impacts. For example, the UK’s Forest Green Rovers are acknowledged as the world’s most sustainable football club due to their implementation of initiatives designed to harness renewable solar energy and rainwater, eliminate the use of plastics, and reduce their carbon footprint (Gonzalez, Citation2023). Indicative of the role of individuals in driving this process, the club’s emphasis on sustainability was implemented when British environmentalist Dale Vince became the club’s chairman in 2010, and gained further attention when Spanish footballer Hector Bellerin joined the ownership group a decade later (Gonzalez, Citation2023).

Endemic and non-endemic brand relationships

Sport brands operate in a multi-layered environment where relationships between brands exist across multiple levels (Baker et al., Citation2022). As brand perceptions are formed through an evaluation of one’s direct experiences and from associative information (Ross et al., Citation2008), understanding ILSBs requires consideration of surrounding brands. For ILSBs these relationships exist with both organisational-level and individual-level brands. Furthermore, as depicted in , these brands encompass those that are involved in sport, alongside those that extend beyond sport.

Sport-based research has established that consumer perceptions of leagues and teams are influenced by the presence of star athletes (Daniels et al., Citation2019) and managers (Berndt, Citation2022), and such individuals can drive team-level sponsorships (Biscaia et al., Citation2013). Similarly, ILSBs must carefully consider how the respective events, federations, leagues, and teams with which they are associated impact their brands (Kunkel & Biscaia, Citation2020). For example, athlete social media followers can increase exponentially when they transfer leagues, and likewise the teams they choose to join reflect an important determinant of the magnitude of this impact (Su et al., Citation2020). Increased followers and affiliations with larger and stronger league and team brands also open opportunities for ILSBs to tap into more lucrative networks, further enhancing the appeal of the individual to sponsors and philanthropic organisations (Noh et al., Citation2023). Likewise, the professional networks and resources athletes have access to, like agents, can significantly impact how effectively their brands are managed (Hu et al., Citation2023).

The following case of Tom Brady illustrates these relationships. Brady is unavoidably linked to prominent teammates (e.g. Rob Gronkowski), rivals (e.g. Peyton Manning), coaches (e.g. Bill Belichick) and the success he enjoyed at his teams, the New England Patriots and Tampa Bay Buccaneers. His career narrative is also shaped by his college football journey at the University of Michigan (where he was selected 199th overall in the 2000 NFL Draft) and continues to be impacted by his retirement decisions, like becoming a part-owner of Birmingham City FC in 2023. These examples represent some of the individual and group-level brands that shape this athlete’s brand, and it is important to note that similarly, Tom Brady’s brand acts as an information source for these brands to be evaluated. Other examples included in the ISBMF relevant here include the representative league (NFL) and specific events (10 Super Bowl appearances), alongside agents, managers, superfans, and media pundits. Yet each of the above examples represent sport brands, yet numerous individuals and organisations which impact ILSBs also exist beyond sport (e.g. Bredikhina et al., Citation2023).

The popularity of sport has seen celebrity actors and musicians joining ownership groups (e.g. Wrexham FC and Angel City FC), and non-sport brand ambassadors (e.g. musician Drake), and superfans (e.g. Nav Bhatia) become intertwined with ILSBs. Bhatia, a Sikh-Canadian immigrant, and self-made businessperson, offers a physical manifestation of the Toronto Raptors’ desired brand association with a diverse and multicultural organisation and fanbase (Aladejebi et al., Citation2022). Even absent a personal background in elite sport, Bhatia is now enmeshed in the sport brand ecosystem around the Toronto Raptors organisation, and linked to the individual players and coaching staff who he interacts with, supports, and promotes via his social media channels.

While often operating primarily in the background, owners wield an outsized impact on their team when they do step into the spotlight. Prominent examples include Mark Cuban, owner of the NBA’s Dallas Mavericks, and Roman Abramovich, former owner of the EPL’s Chelsea FC. Cuban, a serial entrepreneur and investor with a focus on technology firms, is the face of the Mavericks organisation and public image, lending forward-looking associations to the team brand image. Conversely, in response to increased geopolitical tension with Russia, the United Kingdom imposed sanctions on Abramovich, freezing his assets in the country. A clear blow to Chelsea’s brand image, major sponsors suspended their partnerships, and ultimately Abramovich was forced to sell the club. These examples exemplify the interconnected nature of sport brands with those beyond, where associations spill over from individuals to teams (and other organisational brands) and back to individuals.

Finally, ILSBs have a range of interpersonal connections outside of sport which exert influence on their brands (Bredikhina et al., Citation2023). Such relationships include family networks, romantic and friendship circles, business partners, and associations with influencers. Consider the familial ties that exist between current USWNT player Trinity Rodman and NBA Hall of Famer father Dennis Rodman, or the expectations and hype surrounding LeBron James’ son Bronny. The brands of women’s football power couple Sam Kerr and Kristie Mewis are interlinked due to their relationship, which became public after Mewis’ USA eliminated Kerr’s Australia from the Tokyo Olympics. Elsewhere, ILSBs have become known for their business partnerships, side ventures, and associations with influencers. For example, French former professional football player Matthieu Flamini has become a billionaire via his involvement in the biotech industry; and Travis Kelce has been exposed to a whole new global audience since he began dating Taylor Swift. The cross-over between sport and popular culture is further exemplified by individuals like Logan Paul competing in high-profile boxing events and establishing a sports drink brand with his former rival KSI.

Messaging strategies

Goffman’s (Citation1959) theory of self-presentation posits that individuals influence how they are viewed by others, at least in part, by how they present themselves. Goffman (Citation1959) outlined how frontstage and backstage content combine to construct the overall image associated with the individual. This theory has been widely employed across research spanning physical and digital settings (cf., Doyle et al., Citation2022). Within sport, frontstage content reflects depictions related to the individual’s professional pursuits, whereas backstage content showcases the individual engaging in their private or personal pursuits (Lebel & Danylchuk, Citation2014). For example, athletes’ frontstage content is illustrative of their athletic performance (e.g., depictions of their skills and achievements), whereas backstage content more closely relates to their attractive appearance (e.g., showcasing their physical fitness and body aesthetics), and marketable lifestyle ( e.g., insights into their family life or philanthropic activities). In the more than 60 years since Goffman’s (Citation1959) foundational theorising, significant efforts have been made to advance how self-presentation theory applies in today’s highly digitised society encapsulating contexts like social media (Geurin-Eagleman & Burch, Citation2016). Consequently, athlete-based research has developed a new content category – offstage content – to account for content that does not directly depict the individual (e.g. sharing motivational quotes or funny videos; Doyle et al., Citation2022).

While the existing body of work helps to provide a contemporary understanding of sport brand management, it has predominantly focused on athletes. Through the development of the ISBMF, we advance this work to conceptualise how an array of other ILSBs (e.g. coaches, agents, owners, managers) can leverage diverse content and communication channels to strategically build their brands. In doing so, we advance knowledge surrounding the sport brand ecosystem and environment and develop an increased understanding related to how ILSBs are intertwined with an array of other brands at both the individual and group levels (Baker et al., Citation2022). Moreover, as demonstrated by the articles in this collection, interconnections exist between the brand management practices employed by ILSBs and those of the related brands that surround them, spilling over to influence how these brands are perceived (Bredikhina et al., Citation2023; Fujak et al., Citation2023; Hu et al., Citation2023; Mogaji & Nguyen, Citation2023; Noh et al., Citation2023).

Communication content and distribution

The perceptions and associations attributed to ILSB are founded on two aspects. First, the content which is being communicated can have an impact on perceptions of ILSBs, as well as how consumers engage with them. For example, scholars have documented how sportswomen are disproportionately portrayed in sexually suggestive manners by the media (Geurin-Eagleman & Burch, Citation2016). Additionally, research demonstrates how different inclusions of back, front, and offstage content, alongside the orientation and accompanying content influence consumer engagement rates (Doyle et al., Citation2022). Second, the medium used to disseminate the content along with the signalling and source of this dissemination is important to consider. Research demonstrates how information about an ILSB is viewed more credibly and as less biased when it is posted by an indirect source (Na et al., Citation2020) and how timing plays a crucial role in determining consumer engagement volume and salience (Weimar et al., Citation2022). Thus, ILSBs need to be cognisant of their direct communications, considering the use of frontstage, backstage, and offstage content types, whilst also monitoring communications originating from other organisational-level or individual-level brands in their sphere of influence. As Hu et al. (Citation2023) demonstrate, many athletes outsource the creation of these communications, and the process of monitoring and responding to narratives in the broader media, to professionals.

Conclusion and future research

We hope this special issue sparks future research focused on furthering knowledge on ILSBs. Considering evolving changes in external factors and the rapid pace of development of technology are key areas to consider. Thus, we recommend investigating how ILSBs can successfully manage their brands considering the increased geopolitical role that sport plays in society (Chadwick, Citation2022) and in an environment where Artificial Intelligence (AI) can be used to automate content creation and customer engagement, blockchain technology can enable new revenue streams, and alternative environments enable the launch of new brand extensions (e.g. Non-Fungible Tokens). The growth of the metaverse and Virtual Reality (VR) platforms represent areas that will enable ILSBs to present content on emerging stages not currently available. Thus, understanding how to manage one’s brand symbiotically and strategically in the physical world as well as in virtual spaces will become paramount.

We anticipate that the trend of ILSBs becoming known for more than their sporting pursuits will continue and this interest will be held by brands and consumers alike. As sport becomes more ingrained within societal structures and conversations, ILSBs will be provided with further opportunities to engage new consumers and increase the depth of connection they have with their existing markets. The ISBMF provides a roadmap to capitalise on such opportunities by better understanding the role that related brands play in impacting the awareness and perceptions attached to ILSBs. Specifically, the ISBMF can be employed to enhance connections with existing fans, and to utilise new means to reach and connect with the diverse subset of individuals who consider themselves non-fans of sport (McDonald et al., Citation2023). Understanding impacts of ILSBs' engagement in philanthropic and community initiatives is a key area to consider as sport stakeholders should not only reap benefits from society (Kunkel et al., Citation2022), but also actively contribute to it (Noh et al., Citation2023). We recommend further investigations into understanding how ILSBs can leverage related brands to develop and monetise their own brands (and vice-versa), as well as the lifecycle of ILSBs. Avenues for work of this type include understanding how ILSBs can successfully pivot when experiencing career interruptions (e.g. Bredikhina et al., Citation2022) or transitions (e.g. retirement, injury, parenthood), or where an athlete builds their personal brand on their performance and then benefits from it as their career trajectory changes (e.g. a student-athlete transitioning into business, or a professional athlete retiring and becoming an investor, coach, or media figure). The ISBMF provides a basis to do this and is a steppingstone to canvass the complex and multi-faceted brand relationships that exist in sport.

Given the focus of the special issue articles, the ISBMF was created with an emphasis on traditional sport contexts. Whilst we believe there is value in applying this to the esports domain on a conceptual level, there are also contextual nuances between traditional and esports which should be further investigated. Namely, ILSBs in the esports context have additional organisational-level brand relationships such as those with specific platforms, publishers, and game developers which exist exclusively in the online context. Additionally, unlike traditional sports, some of the most prominent esports-based ILSBs are not athletes but streamers (e.g. Ninja, AuronPlay, xQc, pokimane). Thus, we extend the call of Cunningham et al. (Citation2018) for further esports-based research and encourage attention focusing on how ILSBs in this context can be developed and managed successfully. Further empirical work testing the ISBMF across both traditional sports and esports is also needed to build theory and provide added utility to practitioners tasked with ILSB management across diverse settings.

Finally, as guest editors of this special issue, we would like to conclude by thanking the contributing authors and all those who have submitted their work for consideration, as well as the anonymous reviewers who provided feedback and guidance on all manuscripts. We would also like to express our gratitude to Professor Paul Downward and Dr Caron Walpole for the opportunity to guest edit this issue and for their contributions to the topic and assistance behind the scenes which spanned from idea to publication. We extend a sincere thank you to everyone who contributed to this special issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abeza, G., & Sanderson, J. (2023). Assessing the social media landscape in sport: Evaluating the present and identifying future opportunities. International Journal of Sport Communication, 16(3), 249–250. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2023-0183

- Aladejebi, F., Allain, K. A., George, R. C., & Nzindukiyimana, O. (2022). “We The north”? race, nation, and the multicultural politics of Toronto’s first NBA championship. Journal of Canadian Studies, 56(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs-2020-0055

- Angel City FC. (2023). Ownership. https://www.angelcity.com/club/ownership

- Arai, A., Ko, Y. J., & Ross, S. (2014). Branding athletes: Exploration and conceptualization of athlete brand image. Sport Management Review, 17(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2013.04.003

- Baker, B. J., Kunkel, T., Doyle, J. P., Su, Y., Bredikhina, N., & Biscaia, R. (2022). Remapping the sport brandscape: A structured review and future direction for sport brand research. Journal of Sport Management, 36(3), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2021-0231

- Berndt, A. (2022). The brand persona of a football manager–the case of arsene wenger. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 23(1), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSMS-01-2021-0018

- Biscaia, R., Correia, A., Ross, S., Rosado, A., & Marôco, J. (2013). Sport sponsorship: The relationship between team loyalty, sponsorship awareness, attitude towards the sponsor and purchase intentions. Journal of Sport Management, 27(3), 288–302. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.4.288

- Bredikhina, N., Sveinson, K., & Kunkel, T. (2022). Innovation under pressure: How athletes transform their business models in times of crisis. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 31(3), 212–227. https://doi.org/10.32731/SMQ.313.0922.04

- Bredikhina, N., Sveinson, K., Taylor, E., & Heffernan, C. (2023). The personal is professional: Exploring romantic relationships within the socioecology of an athlete brand. European Sport Management Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2023.2257706

- Carlson, B. D., & Donavan, D. T. (2013). Human brands in sport: Athlete brand personality and identification. Journal of Sport Management, 27(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.27.3.193

- Chadwick, S. (2022). From utilitarianism and neoclassical sport management to a new geopolitical economy of sport. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(5), 685–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2032251

- Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34(3), 366–375. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.34.3.366

- Cocco, A. R., Kunkel, T., & Baker, B. J. (2023). The influence of personal branding and institutional factors on the name, image, and likeness value of collegiate athletes’ social media posts. Journal of Sport Management, 37(5), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2022-0155

- Crenshaw, K. (1992). Race, gender, and sexual harassment. Southern California Law Review, 63(3), 1467–1476.

- Cunningham, G. B., Fairley, S., Ferkins, L., Kerwin, S., Lock, D., Shaw, S., & Wicker, P. (2018). Esport: Construct specifications and implications for sport management. Sport Management Review, 21(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2017.11.002

- Cury, R., Kennelly, M., & Howes, M. (2023). Environmental sustainability in sport: A systematic literature review. European Sport Management Quarterly, 23(1), 13–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2022.2126511

- Daniels, J., Kunkel, T., & Karg, A. (2019). New brands: Contextual differences and development of brand associations over time. Journal of Sport Management, 33(2), 133–147. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0218

- Delia, E. B. (2020). The psychological meaning of team among fans of women’s sport. Journal of Sport Management, 34(6), 579–590. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0404

- Delia, E. B., Melton, E. N., Sveinson, K., Cunningham, G. B., & Lock, D. (2022). Understanding the lack of diversity in sport consumer behavior research. Journal of Sport Management, 36(3), 265–276. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2021-0227

- Doyle, J. P., Su, Y., & Kunkel, T. (2022). Athlete branding via social media: Examining the factors influencing consumer engagement on Instagram. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(4), 506–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1806897

- Filo, K., Lock, D., & Karg, A. (2015). Sport and social media research: A review. Sport Management Review, 18(2), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2014.11.001

- Fujak, H., Ewing, M. T., Newton, J., & Altschwager, T. (2023). Professional athlete responses to new product development: A dialectic. European Sport Management Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2023.2221674

- Geurin-Eagleman, A. N., & Burch, L. M. (2016). Communicating via photographs: A gendered analysis of Olympic athletes’ visual self-presentation on Instagram. Sport Management Review, 19(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2015.03.002

- Gladden, J. M., Irwin, R. L., & Sutton, W. A. (2001). Managing North American major professional sport teams in the new millennium: A focus on building brand equity. Journal of Sport Management, 15(4), 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.15.4.297

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. DoubleDay.

- Gonzalez, J. (2023). This Soccer Team Is Trying to Save the Planet. Sports Illustrated. https://www.si.com/soccer/2023/04/21/forest-green-rovers-climatechange-daily-cover.

- Hu, T., Siegfried, N., Cho, M., & Cottingham, M. (2023). Elite athletes with disabilities marketability and branding strategies: Professional agents’ perspectives. European Sport Management Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2023.2210598

- Kunkel, T., & Biscaia, R. (2020). Sport brands: Brand relationships and consumer behavior. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 29(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.32731/SMQ.291.032020.01

- Kunkel, T., Biscaia, R., Arai, A., & Agyemang, K. (2020). The role of self-brand connection on the relationship between athlete brand image and fan outcomes. Journal of Sport Management, 34(3), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0222

- Kunkel, T., Doyle, J. P., & Na, S. (2022). Becoming more than an athlete: Developing an athlete’s personal brand using strategic philanthropy. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(3), 358–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1791208

- Lebel, K., & Danylchuk, K. (2014). Facing off on twitter: A generation Y interpretation of professional athlete profile pictures. International Journal of Sport Communication, 7(3), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1123/IJSC.2014-0004

- Manoli, A. E. (2018). Sport marketing’s past, present and future; an introduction to the special issue on contemporary issues in sports marketing. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 26(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2018.1389492

- Manoli, A. E. (2022). Strategic brand management in and through sport. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2022.2059774

- Mason, D. S. (1999). What is the sports product and who buys it? The marketing of professional sports leagues. European Journal of Marketing, 33(3/4), 402–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569910253251

- McCullough, B. P., Orr, M., & Kellison, T. (2020). Sport ecology: Conceptualizing an emerging subdiscipline within sport management. Journal of Sport Management, 34(6), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0294

- McDonald, H., Pallant, J., Funk, D. C., & Kunkel, T. (2023). Who doesn’t like sport? A taxonomy of non-fans. Sport Management Review, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2023.2233342

- Mogaji, E., Badejo, F. A., Charles, S., & Millistis, J. (2022). To build my career or build my brand? Exploring the prospects, challenges and opportunities for sportswomen as a human brand. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(3), 379–397.

- Mogaji, E., & Nguyen, N. P. (2023). Beautiful Black British brand: Exploring intersectionality of race, gender, and self-branding of Black British sportswomen. European Sport Management Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2023.2257229

- Na, S., Kunkel, T., & Doyle, J. (2020). Exploring athlete brand image development on social media: The role of signalling through source credibility. European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(1), 88–108.

- Noh, Y., Ahn, N., & Anderson, A. (2023). Do consumers care about human brands? A case study of using Zaltman Metaphor Elicitation Technique (ZMET) to map two athletes’ engagements in social and political advocacy. European Sport Management Quarterly.

- On3Media. (2023). NIL rankings. https://www.on3.com/nil/rankings

- Ross, S. D., Russell, K. C., & Bang, H. (2008). An empirical assessment of spectator-based brand equity. Journal of Sport Management, 22(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.22.3.322

- Salaga, S., Brison, N., Cooper, J., Rascher, D., & Schwarz, A. (2023). Special issue introduction: Name, image, and likeness and the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Journal of Sport Management, 37(5), 305–306. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2023-0168

- Shapiro, S. L., DeSchriver, T. D., & Rascher, D. A. (2017). The Beckham effect: Examining the longitudinal impact of a star performer on league marketing, novelty, and scarcity. European Sport Management Quarterly, 17(5), 610–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2017.1329331

- Ströbel, T., & Germelmann, C. C. (2020). Exploring new routes within brand research in sport management: Directions and methodological approaches. European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2019.1706603

- Su, Y., Baker, B. J., Doyle, J. P., & Kunkel, T. (2020). The rise of an athlete brand: Factors influencing the social media following of athletes. Sport Marketing Quarterly, 29(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.32731/SMQ.291.302020.03

- Su, Y., Guo, X., Wegner, C., & Baker, T. (2023). The new wave of influencers: Examining college athlete identities and the role of homophily and parasocial relationships in leveraging name, image, and likeness. Journal of Sport Management, 37(5), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2022-0192

- The Business Research Company. (2023). Sports Global Market Report. https://www.thebusinessresearchcompany.com/report/sports-global-market-report

- Weimar, D., Holthoff, L., & Biscaia, R. (2022). When sponsorship causes anger: Understanding negative fan reactions to postings on sports clubs’ online social media channels. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(3), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1786593