?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Research question

While increasing the number of spectators at women’s football matches is critical for the commercial growth of the sport, the academic literature offers limited evidence on the drivers of stadium attendance for women’s football. This study investigates the factors influencing fan interest in the English Football Association (FA) Women’s Super League (WSL).

Research methods

Analysing 476 WSL games played from 2013 to 2018/19, regression models are tested to determine the impacts of socioeconomic factors, product-specific variables, match outcome uncertainty, and the substitution effect.

Results and findings

Strong local economies increase attendance at FA WSL matches, with weekend games, favourable weather, and shorter travel distances also attracting more fans. Higher stadium capacity, outcome certainty, and home team winning odds are associated with increased fan interest. Fans of integrated clubs attend women’s matches less when these clash with games of the respective men’s team, except for double-headers.

Implications

Improving scheduling and matchday facilities is vital for women’s football. Harmonising the football calendar while considering men’s and women’s national and international competitions can enhance stadium attendance at FA WSL matches. Encouraging cross-fertilisation between men’s and women’s football supporters can create spillover effects and boost women’s game attendance.

Introduction

Reaching a consistent level of live attendance is critical for the sustainability and commercial growth of any sport, especially for new and emerging sports leagues that may not have access to lucrative media rights fees (Henderson & Zhang, Citation2019). Larger crowds can also enhance the value of TV rights due to improved stadium atmosphere, making the experience more enjoyable for viewers (i.e. telegenic benefits) (Scelles et al., Citation2020). However, analogous to new businesses, new sports leagues often struggle to build a consistent fan base in their early stages as the interest in sports contests is closely linked with the maturity of the sport product (Agha & Berri, Citation2023; Lock et al., Citation2011).

Following a historical period of chronic underfunding and undervaluation (Williams, Citation2011), in the last decade football institutions have recognised the need to increase the visibility and exposure of the women’s game to unlock its full commercial potential (FIFA, Citation2022; UEFA, Citation2022a). Reports indicate that the fan base of women’s football is growing globally (Nielsen Sports, Citation2019; Women’s Sports Trust, Citation2022). Nonetheless, women’s football finds itself in a transitional phase in terms of commercialisation and financial sustainability. Attendance and matchday revenue for domestic women’s club football remain ‘inconsistent and relatively low’ (UEFA, Citation2022a, p. 27). This poses a considerable challenge for managers working in the women’s game. Therefore, attracting higher numbers of spectators and increasing revenue from matchday events is crucial in driving the development of women’s football forward.

Stadium attendance at professional sports contests is a significant area of research for sports economists and sport management scholars (Downward et al., Citation2009; Feehan, Citation2006; García & Rodríguez, Citation2009). Nevertheless, a recent comprehensive review by Schreyer and Ansari (Citation2022) highlighted the paucity of contributions on the drivers of fan interest for women’s sports, creating a significant research gap. Football is not an exception as previous studies have extensively analysed the demand for the men’s game in various markets and leagues (e.g. Andreff & Scelles, Citation2015; Bond & Addesa, Citation2020; Cox, Citation2018; Forrest & Simmons, Citation2006; Peel & Thomas, Citation1992; Wallrafen et al., Citation2019), while only a handful have conducted econometric analyses on the attendance for women’s football matches. These are limited to Germany (Meier et al., Citation2016), the United States (Chahardovali et al., Citation2023; LeFeuvre et al., Citation2013; Stephenson, Citation2023), and pan-European contexts (Valenti et al., Citation2020). Interestingly, most research on attendance determinants has predominantly focused on English men’s football, largely neglecting its women’s counterpart (Schreyer & Ansari, Citation2022).

This study aims to address these research gaps by analysing a game-level dataset that includes stadium attendance information for the Football Association (FA) Women’s Super League (WSL), one of the most prestigious domestic leagues in elite women’s club football (FIFPro, Citation2017). The choice of the FA WSL is based on its global prominence and level of development in women’s club football. Moreover, the league’s composition, characterised by both independent clubs managing women’s teams autonomously and integrated clubs affiliated with larger entities primarily overseeing men’s football teams, makes the FA WSL a valuable case for empirical investigation into the determinants of women’s football attendance. Additionally, the availability of key attendance predictors, such as the (ex ante) uncertainty of match outcomes, enables empirical investigation of women’s football attendance across various practical settings. The Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) (Citation2022a) has suggested that women’s football stakeholders should focus on improving matchday facilities and scheduling to convert increased engagement into higher stadium attendance and revenue. Analysing the FA WSL allows us to empirically test the impact of (improved) matchday facilities and (in)effective scheduling on stadium attendance at women’s football matches.

Conceptual framework and related literature

Determinants of stadium attendance

Predicting attendance at sports events typically involves considering both socioeconomic and product-specific factors. Socioeconomic determinants encompass ticket prices, host city characteristics and its market size (e.g. population and income), opportunity costs, and the presence of substitutes (Downward et al., Citation2009). To date, no studies have explored the impact of ticket prices on women’s football attendance, likely due to the challenges in obtaining game-level price data and the tendency for women’s football clubs to either offer free entry or charge fans very modest fees (Valenti, Citation2019). Previous research suggests that local income and the size of the host city population do not significantly affect attendance in women’s football (Meier et al., Citation2016; Valenti et al., Citation2020). Conversely, weather conditions and proximity to the stadium can influence attendance, with better weather conditions positively affecting attendance, while greater distances between host cities deterring fans (LeFeuvre et al., Citation2013; Meier et al., Citation2016). A negative association between distance and stadium attendance can also signal the presence of traditional derbies and local rivalries between clubs (Martins & Cró, Citation2018; Wooten, Citation2018). In the current study, similar proxies will be employed to test the importance of socioeconomic variables and opportunity costs for fans of the FA WSL.

Product-specific characteristics, such as expected match quality, match significance, venue quality, and outcome uncertainty, have been shown to impact stadium attendance (e.g. García & Rodríguez, Citation2002). In women’s football, the quality of competing teams has been found to have varying effects, with higher-quality teams increasing attendance in the United States (LeFeuvre et al., Citation2013) but decreasing it in German women’s football (Meier et al., Citation2016). Matches of greater importance, whether in a league or a tournament context, tend to attract more spectators in both German and pan-European women’s club football competitions (Meier et al., Citation2016; Valenti et al., Citation2020). The quality of the venue, however, has not consistently affected attendance in German women’s football (Meier et al., Citation2016). This study will build on these findings by examining the impact of these product-specific factors on attendance in the FA WSL.

Research on the substitution effect in sports has primarily focused on North American major leagues (e.g. Mills & Rosentraub, Citation2014; Mondello et al., Citation2017; Winfree & Fort, Citation2008), with studies analysing substitution for sports contests played in the same league, across different leagues of the same sport, and across different sports. In contrast, a limited number of studies have focused on European sports competitions (e.g. Buraimo et al., Citation2009; Nielsen et al., Citation2019; Wallrafen et al., Citation2019; Citation2022). These studies have mainly compared attendance levels across different competitions within the same sport. For example, it was observed that attendance at lower-division men’s football games is negatively impacted when European club competitions games are broadcasted simultaneously (Buraimo et al., Citation2009; Forrest & Simmons, Citation2006). Spatial proximity and temporal overlaps have also reduced demand for lower-division men’s games when scheduled alongside top-division games in German men’s football (Wallrafen et al., Citation2019). However, none of these studies have examined the substitution effect on women’s sports events. This study introduces a novel scenario in this stream of literature, exploring the impact of concurrent men’s games on women’s football attendance thus shedding light on the potential substitution effect across genders within the same sport.

Outcome uncertainty

The uncertainty of outcome hypothesis (UOH), which posits that sports consumers prefer more uncertain competitions, is considered a widely discussed concepts in sports economics (Manasis et al., Citation2022; Neale, Citation1964; Rottenberg, Citation1956). However, empirical findings regarding the association between outcome uncertainty and demand are inconsistent due to methodological and conceptual variations (for a discussion, see Pawlowski, Citation2013; Szymanski, Citation2003). In women’s football, only two studies have examined the effect of outcome uncertainty on stadium attendance, yielding contradictory results (Meier et al., Citation2016; Valenti et al., Citation2020). While Meier et al. (Citation2016) found no significant effect of match uncertainty in the German Frauen-Bundesliga, Valenti et al. (Citation2020) reported a positive association in the context of the UEFA Women’s Champions League (UWCL). These studies used different proxies for game-level outcome uncertainty, with Meier et al. (Citation2016) employing differences in competing clubs’ league positions and Valenti et al. (Citation2020) utilising unbiased betting odds.

The results of Valenti et al. (Citation2020), however, contrast with studies employing betting odds in men’s football, potentially indicating variations in fans’ preferences for outcome uncertainty in men’s and women’s sports.Footnote1 Also, findings on the women’s game differ from research on the men’s game which have generally found that maximum uncertainty does not positively impact attendance, instead highlighting the importance of the home team’s win probability (Feehan, Citation2006; Peel & Thomas, Citation1992). Coates et al. (Citation2014) indicated the possible presence of supporters’ reference-dependent preferences in sports contests, referring to prospect theory and decision-making under uncertainty (Kahneman & Tverski, Citation1979). In particular, they argued that the decision of fans to attend sports competitions is influenced by the opportunity to watch their team either playing a much inferior opponent (i.e. loss aversion) or assuming an outsider role (i.e. upset result). Valenti et al. (Citation2020) tested the existence of reference-dependent preferences and found that uncertainty of match outcome matters more than the home team’s win probability in the UWCL. However, it is noteworthy that the UWCL includes a knock-out stage, while most previous studies in men’s sports explored determinants of stadium attendance in tournaments with round-robin formats. Whether differences in the format of the competition significantly affect the relationship between outcome uncertainty and attendance remains an open question (Schreyer & Ansari, Citation2022). Therefore, the present study will also contribute to advance the understanding of the association between outcome uncertainty and attendance in a women’s football competition with round-robin format.

Background

The FA Women’s Super League

In England, as in many countries, women were banned from playing football for approximately five decades, from 1921 to 1971, which led to the marginalisation of women’s football in societal, cultural, and economic terms (Griggs & Biscomb, Citation2010; Williams, Citation2006; Williams & Woodhouse, Citation1991). The Women’s Football Association represented the sport from 1969 until 1993 when the FA regained control (Bell, Citation2012). It was only in 1991/92 that women’s football leagues, such as the Women’s Premier League National Division, were established in England, and it was in 2009 that the FA announced plans for the establishment of a semi-professional league, the WSL, for English women’s football clubs.

The FA WSL comprises two tiers: the FA Women’s Super League (formerly Division 1) and the FA Women’s Championship (formerly Division 2). This study focuses on the former. Starting in 2011 as a summer league (March to October), the FA WSL aimed to provide elite women footballer and clubs with space in a sporting calendar dominated by men’s leagues in the winter months (September to May). The league initially featured eight clubs and rapidly gained media attention, sponsorship income, and player payments, becoming one of the most followed women’s football leagues in Europe (Deloitte, Citation2022). Over the years, the league underwent various reconfigurations (see ), including expansion from eight to ten teams, adopting an open format with promotions and relegations, and a shift to winter calendar in 2017. In 2017, the FA WSL ran a Spring Series as an interim edition to bridge the gap to the start of the 2017/18 season when the league moved to a winter calendar, following the traditional schedule of the English men’s competitions. This was coupled with the announcement of further league expansion to 12 teams and the transition from semi-professional to professional status in the 2019/20 season. The league currently offers three sporting prizes to compete for: the league title, qualification to the UWCL, and avoiding relegation.

Table 1. FA WSL reconfiguration overview.

The emergence of integrated women’s football clubs

In European women’s football, clubs typically organise themselves in two ways: independent clubs that manage a women’s team autonomously, and integrated clubs affiliated with larger entities primarily running men’s football teams (Valenti, Citation2019). Integrated clubs with elite-level men’s teams have become increasingly common, offering benefits like access to technical and medical expertise, state-of-the-art facilities, and, most notably, comparably larger financial resources for player wages and transfer fees (Aoki et al., Citation2010; ECA, Citation2014; Valenti, Citation2019; Welford, Citation2018).

The proportion of women’s teams in the FA WSL associated with a men’s club grew from 62.5% in 2011 to 100% in 2022/23. The league’s sporting success has been notably influenced by women’s teams linked to men’s clubs, with all four FA WSL title-winning teams between 2011 and 2022 affiliated with first-division men’s clubs: Arsenal (2011, 2012, 2018/19), Chelsea (2015, 2017, 2017/18, 2019/20, 2020/21, 2021/22), Manchester City (2016), and Liverpool (2013, 2014). This association contributes to enhance stadium attendance and visibility, leveraging on the established brand of the men’s game and encouraging cross-fertilisation of supporters between men’s and women’s sections of the same club (Guest & Luijten, Citation2017; UEFA, Citation2022a; Valenti et al., Citation2020). In line with this, some WSL matches of integrated clubs have also been held in stadiums traditionally reserved for the men’s team, occasionally featuring double-header matches where both men’s and women’s teams play their respective fixtures in temporal succession.

However, while integration between men’s and women’s clubs is viewed as one of the strategies to boost the commercial potential of women’s football, it can sometimes perpetuate the perception that women’s football is subordinate to men’s, whereby women’s football is provided with resources by the men’s game to try and ‘catch up’ in what remains a largely male preserve (Hargreaves, Citation1990). This implies that women’s football often continues to be seen as the ‘big brother’s little sister’ (Woodhouse et al., Citation2019). In addition, the switch of the FA WSL to a winter calendar has created scheduling conflicts with the men’s competitions, potentially affecting supporters’ choice when both men’s and women’s teams of the same integrated club play simultaneously at different venues. This study empirically investigates the possible substitution effect by examining variations in stadium attendance at women’s football games of integrated clubs when the respective men’s team plays concurrently in domestic or international competitions.

Method

Dataset and variables

The study focuses on England, where football ranks among the world’s best in both the men’s and women’s games in terms of sporting quality and commercial revenue (Deloitte, Citation2022; UEFA, Citation2022b). The analysis encompasses all matches played in the FA WSL over seven seasons (2013 to 2018/19), chosen due to data availability and the impact of Covid-19 from the 2019/20 season onwards. The gross sample consists of 476 observations (season 2013, N = 56 games; 2014, N = 56; 2015, N = 56; 2016, N = 72; 2017, N = 36; 2017/18, N = 90; 2018/19, N = 110). The final sample reduces to 344 games due to missing attendance or betting odds data. presents an overview of the variables used in this study.

Table 2. Description of variables.

The natural logarithm of attendance serves as the dependent variable. Season-specific dummies control for time trends. Season dummies also help control for the potential impact of league expansions throughout the period under investigation. Home and away team-specific dummies control unobserved heterogeneity between teams. Also, home team-specific dummies capture the effect of urban area population of the home team site and, as such, control for a club’s potential market size. Income per capita data in the corresponding Nomenclature Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS3) region for both home and away teams were included to capture economic information on each club’s location. Distance between home and away teams’ host cities was measured to control for local rivalries between teams and for potential travel costs for the away supporters. Other control variables such as whether the match is played on a weekday/end and weather conditions (i.e. temperature and rain) were inputted in the equation.

Product-specific characteristics such as stadium size, expected match quality (measured by the average points per game for each team prior to the game),Footnote2 and its significance in the league-context (title contention, qualification for UWCL, relegation) are controlled in this study. More precisely, to measure match significance, six separate dummies (two for each sporting prize, one for the home team, one for the away team) were created, with these dummies taking the value 1 if a change in the standings is possible at the end of the game (‘in-contention’, if only one win is needed for the team, and one loss for their opponent, for a change in the standings to occur), 0 otherwise (‘not in-contention’, if at least two wins are needed for the team, and two losses for their opponent, for a change in the standings to occur). The natural logarithm of each stadium capacity accounted for the potential impact that playing a game in a bigger/smaller stadium has on attendance. For example, integrated clubs playing in larger stadiums typically designated for the men’s team could attract fans facing difficulties attending men’s games, such as high-ticket prices or limited ticket availability for men’s football, who are willing to experience and visit these facilities. Betting odds provide information on match uncertainty, and home team win probabilities are calculated based on these odds. The probabilities of the home team’s win, the away team’s win, and the draw served to operationalise ex ante match outcome uncertainty. Following Peel and Thomas (Citation1992) and Pawlowski and Anders (Citation2012), these three conditions were condensed via the Theil measure for uncertainty (Theil, Citation1967) as follows:

pi reports the vector of the home team’s win probability, the away team’s win probability, and the draw probability of individual matches based on unbiased betting odds retrieved via the website oddsportal.com. The home team’s win probability and its squared term were included in alternative regression models to test the existence of reference-dependent preferences.

For integrated clubs, variables assess men’s team popularity via average stadium attendance for the men’s team in season t. Potential substitution effect was controlled via four distinct scenarios when both men’s and women’s teams of the same integrated club play (1) their respective games on the same day; (2) their respective league games on the same day at home but in separate venues; (3) on the same day and the men’s game is a UEFA Champions League match (either home or away); (4) on the same day and the men’s game is a UEFA Europa League match (either home or away). Finally, a dummy variable was employed to test the effect of double-header games on stadium attendance for the women’s match.

presents summary statistics for the dependent and predictor variables.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

Estimation strategy

The attendance equation formulated in this study is as follows:

the dependent variable is the natural logarithm of attendance at FA WSL game for the home team i against the visiting team j in season t. The equation includes a vector of variables (Cijt) that control for game characteristics, the uncertainty of outcome, scheduling information, and opportunity costs. Considering the longitudinal nature of the dataset, a Hausman test was run to compare estimations from fixed effects and random effects models. The test returned a significant result (p < 0.05), favouring fixed effects estimations due to less biased estimates. To control for club-specific and season-specific unobservable heterogeneity, the equation includes fixed effects that identify the home team (αi), the away team (αj), and the season (αt). The Breusch–Pagan test for heteroscedasticity reported non-significant results (p > 0.05), allowing us to reject the null hypothesis of the presence of heteroscedasticity. The standard error terms (ϵijt) can be considered reliable to capture any unobservable factors that affect attendance. The software Stata/IC 17 was used for the analysis.

Results and discussion

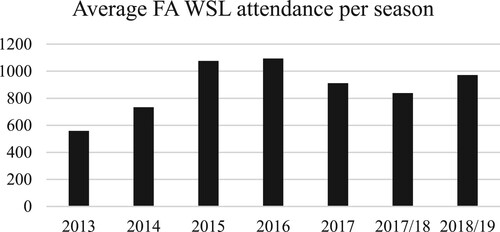

As presented graphically in , attendance in the FA WSL has shown a gradual increase since 2013, with peak interest observed in 2015 and 2016. These peaks could be partially explained by the proximity of the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2015, where the England national team achieved third place, potentially sparking heightened enthusiasm for women’s football in the country. In 2016, the FA WSL followed a summer calendar for the last time. Two consecutive drops in average stadium attendance were observed in the 2017 and 2017/18. These declines are likely attributed to overlaps with the men’s football calendar. However, the FA WSL regained interest in the 2018/19 season, attracting nearly 1000 spectators per game on average. Season-specific dummies did not reveal significant effect for league expansions during the 2013–2019 period. Overall, these findings align with UEFA’s (Citation2022a) perspective that the attendance figures for top-quality women’s club football at the domestic level are inconsistent and relatively low.

offers insights into the effect that both socioeconomic and product-specific variables have on stadium attendance of FA WSL matches. This includes the impact of substitutes (i.e. domestic and continental men’s club games played concurrently) on women’s football attendance. Regression results are split into four columns: the first two present estimates of the main specifications with the uncertainty of outcome measured via the Theil index (Models 1a and 2a); the third and fourth columns display estimates of alternative specifications with home probability win and its squared term to test the existence of reference-dependent preferences (Models 1b and 2b). All four models include fixed effects for the variables Season, Home team, and Away team. Overall, they predict a relatively high percentage of variance (69% < Adjusted R2 < 70%).

Table 4. Regression results for stadium attendance at WSL matches.

Starting with socioeconomic determinants, the home club’s local income has a positive and statistically significant effect on attendance, suggesting that higher local income is associated with increased attendance. This diverges from the results of previous studies (Meier et al., Citation2016; Valenti et al., Citation2020) that found no significant association between local or regional income and attendance at women’s football matches. However, this result should be interpreted cautiously due to the absence of ticket price information for FA WSL games. In relation to travel distance and weather, similar to the German Frauen-Bundesliga (Meier et al., Citation2016), FA WSL fans are less willing to travel long distances to attend matches. Additionally, a significant negative effect of distance might signal rivalries between clubs in the same region or city (e.g. derby matches), akin to the tradition in men’s football.Footnote3 They also prefer games played on weekends and during favourable weather conditions, such as higher temperatures and no rain.

Moving on to product-specific variables, stadium size plays a positive and statistically significant role in predicting attendance in the FA WSL. In contrast to women’s football in Germany, where stadium characteristics have minimal influence on attendance (Meier et al., Citation2016), fans of the FA WSL show a preference for matches held in larger stadiums. The positive impact of larger venue settings is also evident in the context of the National Women’s Soccer League in the United States (Stephenson, Citation2023). This may be due to these larger venues potentially offering advantages such as better accessibility, parking, and comfort, thus attracting more spectators. Also, the utilisation of stadiums traditionally reserved for men’s football might attract fans and supporters facing challenges attending men’s games due to factors such as unaffordable ticket prices or the unavailability of tickets for men’s football events. However, it is worth noting that capacity utilisation rates in FA WSL matches are generally low (mean = 21%) and vary among clubs (SD = ±18%), indicating that stadiums are often too large for the matches hosted. Therefore, clubs should consider selecting venues more carefully to optimise attendance and increase sell-outs (see e.g. Chahardovali et al., Citation2023 for a discussion). Spectator interest is positively associated with the quality of the home team, but the statistical significance varies depending on the inclusion of variables such as the Theil index (Model 1a and 2a) and win probability (Model 1b and 2b).Footnote4 The quality of the away team also positively influences attendance, contrary to findings in German women’s football (Meier et al., Citation2016). This implies that FA WSL fans are willing to watch strong visiting teams.

Focusing on match outcome uncertainty, high ex ante match outcome uncertainty, as measured by the Theil index negatively affects attendance in the FA WSL. This finding contradicts the UOH standard prediction that maximum uncertainty increases attendance, and shows that fans of the FA WSL prefer greater certainty compared to those following the UWCL (Valenti et al., Citation2020). Difference in tournament formats may explain this (Schreyer & Ansari, Citation2022), with maximum uncertainty attracting fans in knock-out stages (e.g. UWCL), while match significance within the context of the competition being more important for fans following round-robin tournaments (e.g. the FA WSL). However, variables controlling for the in-contention effect yield non-significant results in this study, indicating that fan interest is not necessarily driven by a team being in contention for one of the FA WSL sporting prizes. As displayed in alternative model specifications (Models 1b and 2b), the relationship between home team’s win probability and attendance follows a U-shaped curve, with the coefficients of the squared term presenting a value that is twice the coefficients of the normal term. This indicates that attendance decreases until the probability of home team win reaches 50%, after which the impact of home team win probability (i.e. from 50% to 100%) becomes positive on stadium attendance. This aligns with the negative impact of the Theil index, as a home win probability moving from 0% to 50% would suggest a more balanced game (i.e. higher Theil index), and supports the idea that women’s football fans exhibit reference-dependent preferences under uncertainty (Coates et al., Citation2014).

Concerning the spillover and substitution effects, the findings of this study suggest no significant relationship between the popularity of men’s teams (in cases where women’s teams are part of an integrated club) and attendance. However, there is a significant substitution effect for concurrent men’s games. Both domestic league home games and UEFA Champions League games featuring the men’s team of the same integrated club significantly decrease attendance in the corresponding FA WSL match. Concurrent UEFA Europa League games have a non-significant effect on women’s football stadium attendance. Fan interest in women’s football is particularly affected by concurrent UEFA Champions League games, regardless of whether they are played at home or away (e.g. available as live broadcasts on TV). Findings are in line with previous studies on substitution effects across divisions of the men’s game (Buraimo et al., Citation2009; Forrest et al., Citation2004; Forrest & Simmons, Citation2006; Wallrafen et al., Citation2019), suggesting that women’s football games are treated similarly to lower division men’s football when it comes to deciding which match to follow (or not follow). Finally, double-header matches, where women’s and men’s football games are scheduled in temporal succession, have a significant and positive effect on stadium attendance. This indicates that fans are attracted to women’s football matches when they are scheduled alongside their respective men’s team fixtures. As such, these findings add fuel to a long-lasting debate around the issue of male and female integration in sports and whether the development of women’s football should be tied to the men’s game (Hargreaves, Citation1990; Welford, Citation2018; Woodhouse et al., Citation2019).

Conclusion

In conclusion, fans of the FA WSL are influenced by socioeconomic factors, opportunity costs, and product-specific characteristics. Clubs in more affluent areas can expect higher attendance, especially on weekends with favourable weather conditions. Stadium size is positively associated with attendance, but the choice of venue should be carefully considered. Fans of WSL teams prefer games that do not require them to travel long distances. Team quality, match outcome uncertainty, and home team win probability also play significant roles in predicting attendance for women’s football matches. Fans of women’s teams that are part of an integrated club show preferences for games that are scheduled as double-headers with the men’s side and/or hosted in the stadium of the men’s team. Also, they are more likely to attend FA WSL matches when these do not present scheduling conflicts with games of their respective men’s counterpart.

Managerial implications

Some critical implications that are relevant for managers operating in the women’s game can be highlighted. First, the analysis conducted in this study provides support to UEFA’s suggestions that women’s football stakeholders should focus on improving scheduling and matchday facilities in their attempt to increase matchday revenue. In particular, stakeholders should work strategically to harmonise the football calendar while considering both men’s and women’s national and international competitions. For example, the decision of English clubs to schedule more women’s football games in stadiums that traditionally have been reserved for men’s teams (The FA, Citation2022) is therefore supported by the results of this study. Women’s football matches played in these larger venues provide an opportunity for fans to engage with the sport in a more accessible and inclusive manner. Second, as fans show preferences for more certain games, initiatives to favour competitive balance should not be treated as a main priority by the league’s organisers, as these may contribute to reducing fan interest, and, concomitantly, lower chances for English teams to succeed at European level. Yet, the league could still consider policies to restrain excessive spending to avoid clubs engage in a talent arms’ race that has become typical in many men’s football leagues and that would risk undermining financial sustainability. Third, the organisation of double-header games has proven beneficial in increasing attendance at women’s games, highlighting the potential benefits for cross-fertilisation between men’s and women’s football supporters. However, there are additional practical considerations that managers should take into account in terms of the type of product(s) they offer to fans of men’s and women’s football who potentially have different expectations, interests and backgrounds. Also, club managers should consider the likely higher costs associated with hosting two games on the same day (e.g. policing, safety and security) in contrast to a single event.

Limitations and future research

The conclusions drawn from the results of this study should be evaluated carefully against some of the limitations and potential shortcomings presented in this research. First, this research relies on a database that is not fully complete due to the unavailability of information such as ticket prices. It is therefore suggested that future studies include data on ticket prices at the game-level to determine more precisely how fans perceive women’s football in comparison to other available substitute products, and how this might affect their decision to attend (or not attend) when a substitute product is available. Second, the substitution effect is tested for clubs with an integrated structure due to the possibility for this type of clubs to generate a spillover effect and cross-fertilisation of fans, as discussed in previous literature (Guest & Luijten, Citation2017). However, both spatial proximity and temporal overlaps with other (football) events and clubs were not directly controlled for and warrant further investigation. Third, based on the available stadium attendance data, the number of spectators is aggregated for both home and away fans. Future research should attempt to separate the two groups to draw more precise conclusions on the behaviour of women’s football fans in respect of fundamental predictors such as opportunity costs.

Final remarks

Overall, this study presents an original contribution about the determinants of stadium attendance in women’s football, contributing to advancing the understanding of fan interest in women’s sports. Also, it adds valuable insights into this stream of literature, particularly regarding substitution effects and the role of match outcome uncertainty. Additionally, the study provides practical implications for stakeholders in women’s football and sets the background for further analysis of attendance in the women’s game. Enhancing revenue from gate receipts continues to be a substantial challenge that managers operating within women’s football face in their attempt to foster the commercial expansion of the sport. However, following the Covid-19 period with stadiums being shut, it has been reported that attendance at FA WSL games considerably increased with new records set in seasons 2021/22 and 2022/23 (The FA, Citation2022). Notably, the UEFA Women’s Euro 2022 having been held in England coupled with the successful international campaigns of the England women’s national team during both this tournament and the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup have contributed to increase visibility and awareness about women’s football. This creates avenues for future studies to explore the potential impact and legacy that hosting an international tournament (e.g. UEFA Women’s Euro 2022) and the positive results of the national team (i.e. winner of the UEFA Women’s Euro 2022 and runners-up of the FIFA Women’s World Cup 2023) have had on the interest for matches of the FA WSL.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See Qian et al. (Citation2023) for an insightful discussion on core and peripheral market demand for women’s spectator sports.

2 For the first game of the season, average points at the end of the previous season were used (0 for newly promoted teams); for the second game of the season, the highest value between the average point at the end of the previous season and the point(s) gained in the first game was used for each team.

3 Rivalry in sport arises out of an intense relationship between two clubs and/or their fans. While geographic proximity is often a factor, a number of other factors contribute, including frequency of competition, cultural differences and recent and historical competitive parity (see, for example, Tyler & Cobbs, Citation2015).

4 The effect of the variable Point H is inevitably in part captured by the presence of Win probability H.

References

- Agha, N., & Berri, D. (2023). Demand for basketball: A comparison of the WNBA and NBA. International Journal of Sport Finance, 18, 35–44. https://doi.org/10.32731/IJSF/181.022023.03

- Andreff, W., & Scelles, N. (2015). Walter C. Neale 50 years after: Beyond competitive balance, the league standing effect tested with French football data. Journal of Sports Economics, 16(8), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002514556621

- Aoki, K., Crumbach, S., Naicker, C., Schmitter, S., & Smith, N. (2010). Identifying best practice in women’s football: Case study in the European context [Unpublished master dissertation]. FIFA Master 10th edition.

- Bell, B. (2012). Levelling the playing field? Post-euro 2005 development of women’s football in the north-west of England. Sport in Society, 15(3), 349–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2012.653205

- Bond, A. J., & Addesa, F. (2020). Competitive intensity, fans’ expectations, and match-day tickets sold in the Italian Football Serie A, 2012–2015. Journal of Sports Economics, 21(1), https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002519864617

- Buraimo, B., Forrest, D., & Simmons, R. (2009). Insights for clubs from modelling match attendance in football. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602549

- Chahardovali, T., Watanabe, N. M., & Dastrup, R. W. (2023). Does location matter? An econometric analysis of stadium and attendance at National Women’s Soccer League matches. Sociology of Sport Journal, 41(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2022-0217

- Coates, D., Humphreys, B. R., & Zhou, L. (2014). Reference-dependent preferences, loss aversion, and live game attendance. Economic Inquiry, 52(3), 959–973. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12061

- Cox, A. (2018). Spectator demand, uncertainty of results, and public interest: Evidence from the English Premier League. Journal of Sports Economics, 19(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002515619655

- Deloitte. (2022). Annual review of football finance 2022: A new Dawn. Deloitte, Sports Business Group. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/sports-business-group/deloitte-uk-annual-review-of-football-finance-2022.pdf.

- Downward, P., Dawson, A., & Dejonghe, T. (2009). The demand for professional team sports: Attendance and broadcasting. In P. Downward, A. Dawson, & T. Dejonghe (Eds.), Sports economics: Theory, evidence and policy (pp. 261–300). Butterworth-Heinemann. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080942087

- ECA. (2014). Women’s club football analysis. European Club Association – Women’s Football Committee. http://www.ecaeurope.com/PageFiles/7585/ECA_Womens%20Club%20Football%20Analysis_double%20pages.pdf.

- Feehan, P. (2006). Attendance at sports events. In W. Andreff, & S. Szymanski (Eds.), Handbook on the economics of sport (chapter 9) (pp. 90–99). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- FIFA. (2022). FIFA benchmarking report women’s football: Setting the pace. Fédération Internationale de Football Association. https://digitalhub.fifa.com/m/70a3f8fbc383b284/original/FIFA-Benchmarking-Report-Womens-Football-Setting-the-pace-2022_EN.pdf.

- FIFPro. (2017). FIFPro global employment report: Working conditions in professional women’s football. Fédération Internationale des Associations de Footballeurs Professionnels. https://www.fifpro.org/attachments/article/6986/2017%20FIFPro%20Women%20Football%20Global%20Employment%20Report-Final.pdf.

- Forrest, D., & Simmons, R. (2006). New issues in attendance demand. The case of the English Football League. Journal of Sports Economics, 7(3), 247–266. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.11771527002504273392.

- Forrest, D., Simmons, R., & Szymanski, S. (2004). Broadcasting, attendance and the inefficiency of cartels. Review of Industrial Organization, 24(3), 243–265. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:REIO.0000038274.05704.99

- García, J., & Rodríguez, P. (2002). The determinants of football match attendance revisited: Empirical evidence from the Spanish football league. Journal of Sports Economics, 3(1), 18–38.

- García, J., & Rodríguez, P. (2009). Sports attendance: A survey of the literature 1973–2007. Rivista di Diritto ed Economia Dello Sport, 5(2), 111–151.

- Griggs, G., & Biscomb, K. (2010). Theresa Bennett is 42 … but what’s new? Soccer & Society, 11(5), 668–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2010.497370

- Guest, A. M., & Luijten, A. (2017). Fan culture and motivation in the context of successful women’s professional team sports: A mixed-methods case study of Portland Thorns fandom. Sport in Society, 21(7), 1013–1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1346620

- Hargreaves, J. A. (1990). Gender on the sports agenda. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 25(4), 287–305. http://doi.org/10.1177/101269029002500403

- Henderson, C. J., & Zhang, J. J. (2019). Golden goals: Professional women’s football clubs and feminist themes in marketing. In J. J. Zhang, & B. G. Pitts (Eds.), Globalized sport management in diverse cultural contexts (pp. 217–238). Routledge.

- Kahneman, D., & Tverski, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292. https://doi.org/10.2307/1914185

- LeFeuvre, A. D., Stephenson, F. E., & Walcott, S. M. (2013). Football frenzy: The effect of the 2011 World Cup on Women’s Professional Soccer League attendance. Journal of Sports Economics, 14(4), 440–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002513496012

- Lock, D., Taylor, T., & Darcy, S. (2011). In the absence of achievement: The formation of new team identification. European Sport Management Quarterly, 11(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2011.559135

- Manasis, V., Ntzoufras, I., & Reade, J. J. (2022). Competitive balance measures and the uncertainty of outcome hypothesis in European football. IMA Journal of Management Mathematics, 33(1), 19–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/imaman/dpab027

- Martins, A. M., & Cró, S. (2018). The demand for football in Portugal: New insights on outcome uncertainty. Journal of Sports Economics, 19(4), 473–497. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002516661602

- Meier, H. E., Konjer, M., & Leinwather, M. (2016). The demand for women’s league soccer in Germany. European Sport Management Quarterly, 16(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2015.1109693

- Mills, B. M., & Rosentraub, M. S. (2014). The National Hockey League and cross-border fandom: Fan substitution and international boundaries. Journal of Sports Economics, 15(5), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002514535174

- Mondello, M., Mills, B. M., & Tainsky, S. (2017). Shared market competition and broadcast viewership in the National Football League. Journal of Sport Management, 31(6), 562–574. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2016-0222

- Neale, W. C. (1964). The peculiar economics of professional sports: A contribution to the theory of the firm in sporting competition and in market competition. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 78(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1880543

- Nielsen, C. G., Storm, R. K., & Jakobsen, T. G. (2019). The impact of English Premier League broadcasts on Danish spectator demand: A small league perspective. Journal of Business Economics, 89(6), 633–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-019-00932-7

- Nielsen Sports. (2019). The Nielsen women’s football report. Nielsen Sports. https://nielsensports.com/womens-football-2019/.

- Pawlowski, T. (2013). Testing the uncertainty of outcome hypothesis in European professional football: A stated preference approach. Journal of Sports Economics, 14(4), 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002513496011

- Pawlowski, T., & Anders, C. (2012). Stadium attendance in German professional football: The (un)importance of uncertainty of outcome reconsidered. Applied Economics Letters, 19(16), 1553–1556. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2011.639725

- Peel, D. A., & Thomas, D. A. (1992). The demand for football: Some evidence on outcome uncertainty. Empirical Economics, 17(2), 323–331.

- Qian, T. Y., Matz, R., Luo, L., & Zvosec, C. C. (2023). Toward a better understanding of core and peripheral market demand for women’s spectator sports: An importance-performance map analysis approach based on gender. Sport Management Review, 26(1), 114–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2022.2038922

- Rottenberg, S. (1956). The baseball players’ labor market. Journal of Political Economy, 64(3), 242–258.

- Scelles, N., Dermit-Richard, N., & Haynes, R. (2020). What drives sports TV rights? A comparative analysis of their evolution in English and French men’s football first divisions, 1980–2020. Soccer & Society, 12(5), 491–509. https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2019.1681406

- Schreyer, D., & Ansari, P. (2022). Stadium attendance demand research: A scoping review. Journal of Sports Economics, 23(6), 749–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/15270025211000404

- Stephenson, E. F. (2023). International competitions, star players, and NWSL attendance. Journal of Sports Economics, 25(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/15270025231217973

- Szymanski, S. (2003). The economic design of sporting contests. Journal of Economic Literature, 41(4), 1137–1187.

- The FA. (2022, December 9). Kelly Simmons reflects on first half of 2022-23 BWSL and BWC season: ‘We’re making great strides in the right direction’. https://womenscompetitions.thefa.com/en/Article/kelly-simmons-BWSL-season-so-far-20220912.

- Theil, H. (1967). Economics and information theory. North Holland.

- Tyler, B. D., & Cobbs, J. B. (2015). Rival conceptions of rivalry: Why some competitions mean more than others. European Sport Management Quarterly, 15(2), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2015.1010558

- UEFA. (2022a). The business case for women’s football: Defining the value of women’s club football in Europe. Union of European Football Associations. https://editorial.uefa.com/resources/0278-15e121074702-c9be7dcd0a29-1000/business_case_for_women_s_football-_external_report_1_.pdf.

- UEFA. (2022b). Women’s association club coefficients. Union of European Football Associations. https://www.uefa.com/nationalassociations/uefarankings/womenscountry/.

- Valenti, M. (2019). Exploring club organisation structures in European women’s football. UEFA Academy. https://uefaacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/07/2019_UEFA-RGP_Final-report_Valenti-Maurizio.pdf.

- Valenti, M., Scelles, N., & Morrow, S. (2020). The determinants of stadium attendance in elite women’s football: Evidence from the UEFA Women’s Champions League. Sport Management Review, 23(3), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2019.04.005

- Wallrafen, T., Deutscher, C., & Pawlowski, T. (2022). The impact of live broadcasting on stadium attendance reconsidered: Some evidence from 3rd division football in Germany. European Sport Management Quarterly, 22(6), 788–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2020.1828967

- Wallrafen, T., Pawlowski, T., & Deutscher, C. (2019). Substitution in sports: The case of lower division football attendance. Journal of Sports Economics, 20(3), 319–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002518762506

- Welford, J. (2018). Outsiders on the inside: integrating women’s and men’s football clubs in England. In G. Pfister, & S. Pope (Eds.), Female football players and fans: Intruding into a man’s world (pp. 103–124). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Williams, J. (2006). An equality too far? Historical and contemporary perspectives of gender inequality in British and international football. Historical Social Research, 151–169. https://doi.org/10.12759/hsr.31.2006.1.151-169

- Williams, J. (2011). Women's Football, Europe and Professionalization 1971-2011. UEFA Academy. https://uefaacademy.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2019/05/20110622_Williams-Jean_Final-Report.pdf

- Williams, J., & Woodhouse, J. (1991). Can play, will play? Women and football in Britain. In J. Williams, & S. Wagg (Eds.), British football and social change: Getting into Europe (pp. 85–111). Leicester University Press.

- Winfree, J., & Fort, R. (2008). Fan substitution and the 2004-05 NHL lockout. Journal of Sports Economics, 9(4), 425–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002508316266

- Women’s Sports Trust. (2022, September 6). Broadcast audiences grow significantly year-on-year for women’s sport following Women’s Euros success. https://www.womenssporttrust.com/broadcast-audiences-grow-significantly-year-on-year-for-womens-sport-following-womens-euros-success/.

- Woodhouse, D., Fielding-Lloyd, B., & Sequerra, R. (2019). Big brother’s little sister: The ideological construction of women’s super league. Sport in Society, 22(12), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1548612

- Wooten, J. J. (2018). A case for complements? Location and attendance in Major League Soccer. Applied Economics Letters, 25(7), 442–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2017.1332737