Soon after the foundation of the Swedish Association of Behaviour Therapy (SABT) in 1971, the journal Beteendeterapi (Behaviour Therapy) was launched with the aim of disseminating research and concepts relevant for clinical practice in behavioral therapy. Its first editors were Björn Danielsson and Susanne Gaunitz, and 11 Editors-in-Chiefs have since then been in charge of its release: Karl-Olov Fagerström, Steven Linton, Per-Olov Sjödén, Lars-Göran Öst, Sten Rönnberg, Lars-Gunnar Lundh, Gerhard Andersson, Gordon Asmundson, Per Carlbring, and, presently, Mark Powers (American office) and Alexander Rozental (European office). Over the years, the journal has changed its name on two occasions; Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy (1975–2001), following an increased interest in behavioural therapy in the other Scandinavian countries, and, later, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (2002-), reflecting a transition that had begun years before that embraced both behavioural and cognitive traditions.

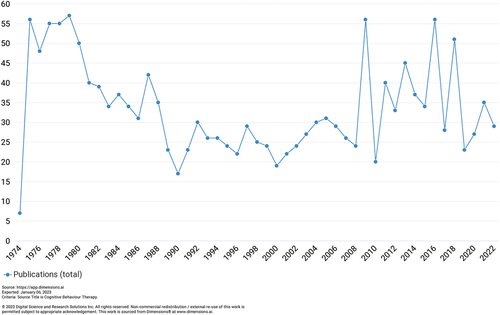

So far, 52 volumes have been released, with publications involving single case designs, naturalistic observations, cross-sectional surveys, psychometric investigations, experiments, randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, the use of both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, as well as book reviews and editorials on a wide range of topics related to the understanding of psychiatric disorders and the outcomes, implementation, teaching, and supervision in cognitive behavior therapy. shows the number of publications per year throughout the period 1974–2022 (which is as far back as publication data are possible to retrieve via www.dimensions.ai). During the last three decades, the average number of publications per year have increased from 25 in the 1990s, 28 in the 2000s, to 37 in the 2010s.

In terms of contributors, provides an overview of the 20 most published and cited authors throughout the years, retrieved from the publisher Taylor & Francis. It includes some of the most highly distinguished and respected researchers in the field. These comprise past editors, such as Gerhard Andersson, Per Carlbring, and Lars-Göran Öst, but also renowned figures like Richard H. Heimberg, Michael W. Otto, and Pim Cuijpers. Since its first issue, more than 500 unique authors have contributed to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.

Table 1. The most published authors in Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.

One important milestone during the last couple of years has been the release of the journal’s first impact factor in 2015. An impact factor is a measure of the average number of citations the publications in a journal received during a two-year time-period. Although there are valid objections to this measure and its significance for science (Garfield, Citation2006), it does nevertheless provide an estimate of how influential the journal is when it comes to the recognition of its publications. provides an overview of the impact factors since it was first received. Based on this, Cognitive Behaviour Therapy was ranked 12th place out of 130 journals in clinical psychology in 2020, according to Journal Citation Reports, which speaks to the relevance and status of the journal and its growing importance as an outlet for researchers in the field.

Table 2. Impact factors 2015–2021.

Beginning in 1971, it is safe to say that Cognitive Behaviour Therapy has played a vital part in the development and dissemination of cognitive behavioral therapies over the years. More than five decades have since passed and there is no doubt that the journal will continue to remain in the forefront of research and clinical practice. Albeit a bit postponed, the current Editors-in-Chiefs would like to take the opportunity to celebrate the journal’s fiftieth anniversary by providing a retrospect on some of the contributions made over the years, highlight a few interesting themes, and, lastly, discuss a number of changes to the journal and important trends believed to become increasingly important moving forward.

1970’s—formation and outreach

After its formation in 1971 the journal was primarily engaged in disseminating research and practical advice to a small but growing number of behaviorally oriented therapists in Sweden. In one of the first issues, Öst (Citation1972), gave a historical overview of systematic desensitization, which was followed by such topics as behavioral therapy’s perspective on schizophrenia, applying operant principles on speech training, how to implement role-play in psychotherapy, and understanding depression from a social learning perspective. Meanwhile, book reviews and adverts about study groups and upcoming congresses in both Sweden and abroad helped members stay informed about relevant resources, training, and lectures. From a historical point of view, some of the most interesting contributions made during these foundational years are perhaps Öst’s (Citation1973) review of “another type of case studies”, i.e. “single-subject experimental design”, which has regained popularity during the last decades. Similarly, Wiemer (Citation1975) informed readers about a therapeutic technique that aims to “assist the client to identify his cognitions, and to restructure them”, i.e. “cognitive restructuring therapy”, which nowadays is an integral part of any type of cognitive behavior therapy. Meanwhile, Öhman (Citation1975) discussed recent research findings on specific phobias and some of the limitations of using an explanatory model based solely on Pavlovian conditioning, which later would become important aspects of his well-known research on predisposing factors in fear and the acquisition of anxiety disorders. Moreover, Linton (Citation1979) described how a behavioral approach could be useful in conceptualizing and treating lower back pain; now a central component in the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Some of the most recurrent themes in the journal during this decade revolved around autism, eating disorders, learned helplessness, marital counseling, smoking cessation, as well as behavioral modification approaches to various conditions and patient groups, demonstrating already a wide range of applications of behavioral therapy.

The 1970s was, however, also a period characterized by outreach and forming networks related to research and training. Societies in Denmark, Norway, and Finland became collaborators in terms of spreading knowledge about behavioral therapy, and their members were invited to lectures and workshops with internationally renowned speakers, such as Martin Seligman and Paul Liberman. In addition, the journal started to provide congress reports from forums like the American Association for the Advancement of Behavior Therapy (ABCT) and the European Conference of Behavior Therapy (EABCT). It also engaged with the surrounding society by publishing rebuttals on how behavior therapy was being portrayed in Swedish media, which at the time was mostly characterized by aversive conditioning.

At the end of the decade, it is clear that the efforts made by the journal’s founders had paid off and created a much appreciated and respected platform for both researchers and therapists alike, with contributions stemming not only from the Scandinavian countries but from all over the world. Furthermore, looking back on these first foundational years demonstrates that some of its earliest authors would eventually become highly recognized researchers in the field of cognitive behavior therapy.

1980’s—the rise of cognitive therapy and behavioral medicine

In the 1980s the journal had become an outlet for international high-quality research on not only behavioral therapy but also cognitive behavior therapy. The rise of cognitive therapy and its increased importance in treatment is unmistakable by reviewing the number of publications on its application to different conditions. The journal also devoted more space to training in cognitive therapy, for example adverts about the second Nordic meeting on behavioral therapy in 1985, which included four workshops on its usefulness in treating depression, phobias and anxiety disorders, behavioral medicine, and alcoholism. However, the decade was also characterized by the rise of behavioral medicine. The link between psychological mechanisms and somatic issues became a popular subject and both reviews and studies on how to apply cognitive behavior therapy to such issues as headache and migraine, gastrointestinal disorders, and chronic pain. Societies in other fields also started to advertise about upcoming congresses where the importance of multidisciplinary exchange and research was emphasized, for example the International Headache Congress (IHC) and the Society of Behavioral Medicine (SBM).

A few interesting trends from this era are also possible to distinguish. First, the advent of computers and its potential relevance in treatment. Foree-Gävert and Gävert (Citation1980) described how computer-feedback was used to create personalized diets and determine treatment progress for patients undergoing a behavioral therapy program for weight loss; constituting a starting point on what would eventually become an important tool in the assessment and delivery of treatment, such as computerized screening and Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. Second, more and more studies focused on a type of fear that possibly reflected the increased availability and popularity of a new mean of transportation—fear of flying. Nordlund (Citation1983) conducted a survey among randomly selected Swedes about their fear of flying, demonstrating that 6% had never left the ground because of their fears, while 10% experienced an intense fear while flying. Meanwhile, Ekeberg et al. (Citation1988), did a similar investigation of passengers at random domestic flights in Norway, showing that 21% of the female and 8% of the male respondents were always afraid of flying. This might perhaps explain the increased number of studies in the journal at the time that described how to treat the fear of flying by applying techniques in cognitive behavior therapy, particularly exposure. Lastly, the 1980s was also plagued by the AIDS epidemic, which caught the attention of researchers interested in community-based approaches to prevention. For example, Kelly and Lawrence (Citation1987) summarized and discussed how behavioral therapy based on operant principles could be helpful in the prevention of AIDS by understanding and targeting risky sexual behaviors, creating, and promoting educational programs, and implementing interventions that target whole societies and not only individuals.

The 1980s was also characterized by additional topics and findings that would prove fundamental to how cognitive behavior therapy was performed and tested. The journal published several articles on a therapeutic technique known as applied relaxation, which of course would become an essential intervention for anxiety disorders and stress-related issues. Furthermore, it demonstrated how a single-session exposure treatment could be used to treat injection phobia (Öst, Citation1985), later becoming the gold-standard in treating specific phobias. From a research perspective, more studies also added a follow-up assessment to its more commonplace pre-to-post-treatment evaluation in order to determine the long-term outcomes, while the psychometrics of self-report measures gained increased attention and the concept of quality of life became more popular in psychotherapy. At the end of the decade, both the journal itself and the study of cognitive behavior therapy were more refined, setting the occasion for even more sophisticated research in the decade to come.

1990’s—the interest in specific psychiatric disorders and helping children and adolescents

At the dawn of the 1990s, cognitive behavior therapy had established itself as a treatment for a range of conditions. Contributions made to the journal started to reflect its application to specific psychiatric disorders, such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic disorder, and panic disorder, and an increasing number of publications from this decade focused on the dissemination of concepts and models intended to inform therapists in their clinical practice. Støylen (Citation1996) introduced habit reversal as a therapeutic technique for trichotillomania, explaining how recording the daily number of hairs pulled and the use of alternative behaviors to hair-pulling can be applied, and which is still being regarded as a highly effective method. Meanwhile, Wijma and Wijma (Citation1997) presented an overview on how to assess and treat vaginismus using the newly developed self-report measure, the Vaginismus Behaviour Scale, and providing exposure in relation to anxiety-provoking situations; another procedure yet in use and considered beneficial in its original form. Similarly, the idea of delivering shorter treatments with maintained effects was also explored and discussed, such as four sessions for panic disorder, which proved that comparable results were possible to achieve and maintain up to the six-month follow-up (Westling & Öst, Citation1999).

During the same period, special issues were released concerning the benefits of using cognitive behavior therapy in behavioral medicine, including one completely devoted to pain. This marked a continued interest in the topic introduced a decade earlier, and consisted of publications on, for instance, depression, and pain (de C Williams, Citation1998), childhood asthma (Dahl, Citation1998), and insomnia (Lundh, Citation1998). Overall, insomnia was a recurrent topic in the journal throughout the 1990s, with several noteworthy publications by Lars-Gunnar Lundh on the relationship between sleeping difficulties, performance, and perfectionism (Broman et al., Citation1992; Lundh et al., Citation1994). Moreover, another special issue was entirely dedicated to schizophrenia, which included an overview of the field and examples on how to involve families in treatment, the integration of interventions, and the importance of community management.

In the 1990s, increased attention was also paid to the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and use of cognitive behavior therapy with children and adolescents. Adaptations to treatment were discussed, and although the lack of evidence for many conditions was noted, publications in this area expressed great interest in finding better ways to assess and treat younger individuals. King and Tonge (Citation1991) reviewed the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents and the usefulness of exposure with response prevention. Meanwhile, Arnarson et al. (Citation1994) administered a self-report measure on depression to 436 school-children in Iceland, identifying 10% as depressed. Three decades later, mental health problems among younger individuals unfortunately still remain one of the most important issues facing health care, demonstrating the significance of continued research on screening and early interventions.

As the end of the millennium came closer, new perspectives to understand and treat psychiatric disorders were also introduced for the first time in the journal. Kåver (Citation1997) presented Dialectical Behavior Therapy as an “innovative method of treatment that has been developed specifically for this difficult group of patients”, referring to the many challenges facing therapists working with patients with borderline personality disorders and how this new approach provided hope. In addition, Lundh (Citation1999) presented readers with an enthusiastic book review of the ground-breaking title Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, calling it nothing less than “one of the most exciting new directions within the field of cognitive-behaviour therapy”. To sum up the 1990s, the coming decade seemed to hold many promises with regard to the future of cognitive behavior therapy.

2000’s—the breakthrough of the Internet and the transdiagnostic perspective

The first issue of the 2000s set the occasion for the decade to come. In an editorial by Andersson (Citation2000), the so-called dodo bird-verdict and its implications for research and clinical practice was discussed. Apart from reviewing the benefits and limitations of using meta-analysis to inform clinical decision-making, the difficulties in establishing superiority among treatments were noted, an issue that remains just as true today. The editorial was, however, optimistic of what the future might bring, pointing out that research from both a cognitive behavioral and psychodynamic perspective would be fruitful in terms of finding out what works for whom. In addition, the early 2000s also marked an important shift in the history of the journal, as it transformed from Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, and invited Gordon Asmundson to become its first editor for its American office. The journal had thereby fully entered the international stage and become part of a growing research community that connects researchers from across the globe.

It would be hard to review the many landmarks of this decade without mentioning the breakthrough of Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. During these years, the Internet quickly became an important format to deliver treatments, and perhaps one of the most popular topics in the journal. Already in 2003, a special issue on cognitive behavior therapy and the Internet was released, including a review on all of the studies for panic disorder published so far (Richards et al., Citation2003), and one highly cited randomized controlled trial for stress management (Zetterqvist et al., Citation2003). Furthermore, the rise of computers also affected the assessment of psychiatric disorders, as more procedures such as structured clinical interviews and self-report measures could be administered via new means. The 2000s also featured two additional special issues on the topic, this time devoted to the efficacy of computerized treatments for depression and anxiety disorders. At the end of the decade, Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy was no longer just a new and stimulating domain for researchers, but had become an integral part of healthcare.

The 2000s also featured publications on telephone-delivered treatments, the effects of group treatments, and a growing interest in motivational interviewing. Westra (Citation2004) introduced the concept in an overview of its characteristics and applications in relation to cognitive behavior therapy, and researchers started coding sessions in order to determine and improve skills in motivational interviewing (Forsberg et al., Citation2007); nowadays a widely used approach in therapists” training. Several other special issues were also published, for example, on the treatment of both obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder, but, most notably, the aftermath and psychological effects of the horrific terrorist attack on 11 September 2001 (Stewart, Citation2004), including studies on remote exposure to trauma and the distress experienced by both clinical and non-clinical samples.

During the 2000s, researchers also started investigating concepts that cut across psychiatric disorders, often referred to as transdiagnostic. This included risk factors for developing eating disorders, such as low self-esteem (Ghaderi, Citation2001), and the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and different conditions. However, perhaps most influential is the hierarchical model of mental distress, which regard underlying vulnerabilities such as neuroticism as essential in order to understand the development and maintenance of any psychiatric disorder (c.f., Norton & Mehta, Citation2007; Sexton et al., Citation2003). Such ideas would play a key part in the rise of transdiagnostic treatments like Unified Protocol, which would become one of the most interesting topics in research and clinical practice moving forward.

2010’s—routine care, new technology, and the potential negative effects of treatment

The years running up to this journal’s 50th anniversary is in some ways an extension of the topics that were introduced one decade before. The focus on transdiagnostic issues continued, with factors such as intolerance of uncertainty becoming popular to explore in relation to different conditions. In addition, more clinical trials were published on the outcomes of transdiagnostic treatments. Reinholt et al. (Citation2017), investigated the effects of group-delivered Unified Protocol among psychiatric outpatients with different types of anxiety disorders, demonstrating that those suffering from high levels of comorbidity benefitted to the same extent as those with less comorbidity. Similarly, Johnston et al. (Citation2013) trialed a transdiagnostic treatment via computers for anxiety disorders, with comparable results, suggesting that it might be useful in other formats as well. Furthermore, the Internet was no longer the only new means of delivering treatment, with the 2010s sparking an interest in the application of virtual reality in treating conditions like specific phobia (Lindner et al., Citation2017). The popularity of hand-held devices also stressed the importance of adapting new technological trends in treatment, which laid the foundation for using applications, such as helping patients carry out exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder via their smartphone (Boisseau et al., Citation2017).

The 2010s was also characterized by not only determining the efficacy of treatments but also its effectiveness in routine care. For instance, Hedman et al. (Citation2010) examined the outcomes of group-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for patients with hypochondriasis in regular health care, showing both promising results and the potential for cost-effectiveness. Kivi et al. (Citation2014) were also able to demonstrate that Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression could be successfully implemented in primary care, with comparable effects to treatment as usual, indicating the potential for increased outreach. Meanwhile, another highly influential contribution made to the journal during these years was the adaptation and evaluation of a four-day treatment for obsessive compulsive disorder (i.e. the Bergen-model), which holds many promises for how treatment can be delivered and optimized in routine care (Hansen et al., Citation2019). Moreover, Levy and Radomsky (Citation2014, Citation2016) challenged the popular idea that all safety behaviors are created equal, arguing that some may enhance acceptability to exposure and response prevention without affecting outcomes negatively; a debate that is still ongoing and has led to more experimental research on previously held beliefs about how cognitive behavior therapy should be administered.

The decade also featured studies on the possible unwanted and adverse events that occur during treatment, i.e. negative effects. Although the topic is not a new one (Barlow, Citation2010), empirical studies were lacking. Bystedt et al. (Citation2014) investigated the awareness of the topic among therapists in Sweden, indicating that many had encountered negative effects among their patients, but that most were still unaware of how to accurately identify and prevent them. Similarly, Rozental et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated that 9.3% in a sample of 558 patients undergoing Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for different conditions reported adverse and unwanted events, which were subsequently categorized as being either patient-related or treatment-related. The jury is still out with regard to how negative effects should be defined, measured, and reported, but researchers at least seem more aware of this issue today and have begun exploring its occurrence and characteristics more systematically.

Several special issues were released during the 2010s which also highlight some of the recent trends in the field. These included the use of physical exercise in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, either as an effective stand-alone intervention or an adjunct to cognitive behavior therapy (Powers et al., Citation2015), and concepts concerning information-processing and affectivity in different conditions, such as positivity impairments in social anxiety disorder (Weeks & Heimberg, Citation2012). In 2013, a special issue was also dedicated to Lars-Göran Öst, one of the journal’s founders, in honor of his retirement and appreciation of his many years researching and disseminating cognitive behavior therapy (Andersson et al., Citation2013), and whom has continued to stay active as a researcher and lecturer.

The 2010s can be summarized as reflecting great diversity and curiosity with regard to research on psychiatric disorders in general, and cognitive behavior therapy in particular. Since then, contributions made to the journal continue to advance the field and further our understanding on how to improve mental health and well-being. Lately, several important systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published, and studies on the predictors of a successful outcome and the dose-response curves among patients promises more tailored and effective treatments to come.

2020’s—the way ahead

As a new decade began Cognitive Behaviour Therapy turned 50 years old and remains as vibrant as ever. With the advent of the 2020s, a number of changes have, however, been made. First, Per Carlbring resigned as Editor-in-Chief for the European office in 2022, signing off after almost two decades (Carlbring, Citation2022). His efforts cannot be understated and he is thanked for his long and dutiful service. As his successor, Alexander Rozental aims to continue his work together with Mark Powers, making sure that the journal remains one of the most influential in its field. Second, in 2023 the publication process turned completely digital, which means that the journal is no longer available in print. Although a paper version is sometimes preferred by readers, this will speed up production and make sure that publications are made available much quicker than before. Third, both the editors of the journal and the editorial board have undergone an oversight in terms of its composition. This is to make sure that the members of the journal are more diverse when it comes to such aspects as gender, ethnicity, nationality, and research profiles. This work has just begun and much more needs to be done, but a few steps have already been made to make sure the journal is inclusive and accurately reflect the whole of the scientific community. Finally, even though it is notoriously difficult to predict the future (Tetlock et al., Citation2014), the current Editors-in-Chiefs would nevertheless like to point out a couple of trends warranting further research and perhaps upcoming submissions to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy.

Teaching and supervision: although the importance of training is often stressed in relation to delivering treatment, studies on teaching and supervision in cognitive behavior therapy are lacking. This concerns such aspects as the effects of supervision on treatment outcome and how regular feedback could improve continued learning and growth even after a degree in clinical psychology. A few researchers are presently investigating this issue (Alfonsson et al., Citation2020), but more needs to be done.

Problems of daily life: the focus of much research has naturally been on treating psychiatric disorders, as defined by diagnostic manuals. However, a lot of the difficulties facing people in their daily lives are not possible to diagnose, e.g. perfectionism, procrastination, loneliness, and self-esteem. Looking more closely at these problems is an important domain which hopefully will attract more researcher in the future, similar to the work done by Grieve et al. (Citation2022) and Berg et al. (Citation2022).

Negative effects: cognitive behavior therapy can alleviate symptoms and increase well-being for many patients, but a small number also seem to experience adverse and unwanted events during treatment. Why this is the case and what impact it might have on dropout and outcome is, however, unexplored. Future research should investigate these relationships by, for instance, administering self-report measures on negative effects at several occasions during treatment, examine the subjective experience of deterioration using qualitative interviews, and explore the expectations patients might be going into treatment (Rozental et al., Citation2018).

Dissemination/Implementation: there are a large number of evidence-based treatments for psychological disorders but few people actually receive these in practice. Studies on dissemination and implementation science are encouraged, including modifications (e.g. brief versions, apps, and web-based) to get the treatments to those who need them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alfonsson, S., Lundgren, T., & Andersson, G. (2020). Clinical supervision in cognitive behavior therapy improves therapists’ competence: A single-case experimental pilot study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 49(5), 425–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2020.1737571

- Andersson, G. (2000). On Alice in Wonderland, statistics, and whether CBT should take the prize. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 29(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/028457100439818

- Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., & Holmes, E. A. (2013). Special issue in honour of Lars-Göran Öst. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 42(4), 259–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2013.843297

- Arnarson, E. Ö., Smári, J., Einarsdóttir, H., & Jónasdóttir, E. (1994). The prevalence of depressive symptoms in pre-adolescent school children in Iceland. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 23(3–4), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506079409455969

- Barlow, D. H. (2010). Negative effects from psychological treatments: A perspective. The American Psychologist, 65(1), 13–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015643

- Berg, M., Lindegaard, T., Flygare, A., Sjöbrink, J., Hagvall, L., Palmebäck, S., Klemetz, H., Ludvigsson, M., & Andersson, G. (2022). Internet-based CBT for adolescents with low self-esteem: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 51(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2022.2060856

- Boisseau, C. L., Schwartzman, C. M., Lawton, J., & Mancebo, M. C. (2017). App-guided exposure and response prevention for obsessive compulsive disorder: An open pilot trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(6), 447–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1321683

- Broman, J. -E., Lundh, L. -G., Aleman, K., & Hetta, J. (1992). Subjective and objective performance in patients with persistent insomnia. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 21(3), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506079209455903

- Bystedt, S., Rozental, A., Andersson, G., Boettcher, J., & Carlbring, P. (2014). Clinicians’ perspectives on negative effects of psychological treatments. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 43(4), 319–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.939593

- Carlbring, P. (2022). Signing off after two decades. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 51(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2022.2026062

- Dahl, J. (1998). A behavioural medicine approach to the analysis and treatment of childhood asthma. Behaviour Therapy, 27(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02845719808408492

- de C Williams, A. C. (1998). Depression in chronic pain: Mistaken models, missed opportunities. Behaviour Therapy, 27(2), 61–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02845719808408497

- Ekeberg, Ø., Seeberg, I., & Bratsberg Ellertsen, B. (1988). The prevalence of flight anxiety in Norwegian airline passengers. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 17(3–4), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506078809455829

- Foree-Gävert, S., & Gävert, L. (1980). Obesity: Behavior therapy with computer-feedback versus traditional starvation treatment. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 9(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506078009456176

- Forsberg, L., Källmén, H., Hermansson, U., Berman, A. H., & Helgason, Á. R. (2007). Coding counsellor behaviour in motivational interviewing sessions: Inter‐rater reliability for the Swedish Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity code (MITI). Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(3), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701339887

- Garfield, E. (2006). The history and meaning of the journal impact factor. JAMA, 295(1), 90–93. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.1.90

- Ghaderi, A. (2001). Review of risk factors for eating disorders: Implications for primary prevention and cognitive behavioural therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 30(2), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/02845710117890

- Grieve, P., Egan, S. J., Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., Shafran, R., & Wade, T. D. (2022). The impact of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism on different measures of perfectionism: A randomised controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 51(2), 130–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2021.1928276

- Hansen, B., Kvale, G., Hagen, K., Havnen, A., & Öst, L. G. (2019). The Bergen 4-day treatment for OCD: Four years follow-up of concentrated ERP in a clinical mental health setting. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 48(2), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1478447

- Hedman, E., Ljótsson, B., Andersson, E., Rück, C., Andersson, G., & Lindefors, N. (2010). Effectiveness and cost offset analysis of group CBT for hypochondriasis delivered in a psychiatric setting: An open trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 39(4), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2010.496460

- Johnston, L., Titov, N., Andrews, G., Dear, B. F., & Spence, J. (2013). Comorbidity and internet-delivered transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural therapy for anxiety disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 42(3), 180–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2012.753108

- Kåver, A. (1997). Dialektisk beteendeterapi för suicidala borderline-kvinnor: En presentation. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 26(3), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506079708412479

- Kelly, J. A., & Lawrence, J. (1987). The prevention of AIDS: Roles for behavioral intervention. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 16(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506078709455778

- King, N. J., & Tonge, B. J. (1991). Obsessive-compulsive disorder in children and adolescents: Clinical syndrome and treatment. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 20(3–4), 91–99.

- Kivi, M., Eriksson, M. C., Hange, D., Petersson, E. L., Vernmark, K., Johansson, B., & Björkelund, C. (2014). Internet-based therapy for mild to moderate depression in Swedish primary care: Short term results from the PRIM-NET randomized controlled trial. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 43(4), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.921834

- Levy, H. C., & Radomsky, A. S. (2014). Safety behaviour enhances the acceptability of exposure. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 43(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2013.819376

- Levy, H. C., & Radomsky, A. S. (2016). Are all safety behaviours created equal? A comparison of novel and routinely used safety behaviours in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(5), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1184712

- Lindner, P., Miloff, A., Hamilton, W., Reuterskiöld, L., Andersson, G., Powers, M. B., & Carlbring, P. (2017). Creating state of the art, next-generation Virtual Reality exposure therapies for anxiety disorders using consumer hardware platforms: Design considerations and future directions. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(5), 404–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2017.1280843

- Linton, S. J. (1979). Behavioral approaches to low back pain. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 8(3), 121–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506077909456149

- Lundh, L. G. (1998). Cognitive-behavioural analysis and treatment of insomnia. Behaviour Therapy, 27(1), 10–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/02845719808408491

- Lundh, L. G. (1999). Book review: Acceptance and commitment therapy. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 28(4), 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/028457199439937

- Lundh, L. G., Broman, J. E., Hetta, J., & Saboonchi, F. (1994). Perfectionism and insomnia. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 23(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506079409455949

- Nordlund, C. L. (1983). Flygrädsla i Sverige. En enkätundersökning av svenskars rädsla för trafikflyg som transportmedel. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 12(3), 150–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506078309455668

- Norton, P. J., & Mehta, P. D. (2007). Hierarchical model of vulnerabilities for emotional disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(4), 240–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070701628065

- Öhman, A. (1975). Fobisk betingning: En laboratorieanalog för experimentell behandlingsforskning. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 4(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506077509456044

- Öst, L. G. (1972). Historisk utveckling av systematisk desensibilisering 1: Åren 1920-1959. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 1(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.1972.9626610

- Öst, L.-G. (1973). Experimentella designer vid N=1: En litteraturöversikt. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 2(3), 77–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.1973.9626639

- Öst, L.-G. (1985). Single-session Exposure Treatment of Injection Phobia: A case study with continuous heart rate measurement. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 14(3), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506078509456232

- Powers, M. B., Asmundson, G. J., & Smits, J. A. (2015). Exercise for mood and anxiety disorders: The state-of-the science. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(4), 237–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1047286

- Reinholt, N., Aharoni, R., Winding, C., Rosenberg, N., Rosenbaum, B., & Arnfred, S. (2017). Transdiagnostic group CBT for anxiety disorders: The unified protocol in mental health services. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1227360

- Richards, J., Klein, B., & Carlbring, P. (2003). Internet-based treatment for panic disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 32(3), 125–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070302318

- Rozental, A., Boettcher, J., Andersson, G., Schmidt, B., & Carlbring, P. (2015). Negative effects of internet interventions: A qualitative content analysis of patients’ experiences with treatments delivered online. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(3), 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2015.1008033

- Rozental, A., Castonguay, L., Dimidjian, S., Lambert, M., Shafran, R., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2018). Negative effects in psychotherapy: Commentary and recommendations for future research and clinical practice. BJPsych Open, 4(4), 307–312. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2018.42

- Sexton, K. A., Norton, P. J., Walker, J. R., & Norton, G. R. (2003). Hierarchical model of generalized and specific vulnerabilities in anxiety. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 32(2), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070302321

- Stewart, S. H. (2004). Psychological impact of the events and aftermath of the September 11th, 2001, terrorist attacks. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 33(2), 49–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070410033419

- Støylen, I. J. (1996). Treatment of trichotillomania by habit reversal. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 25(3–4), 149–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506079609456020

- Tetlock, P. E., Mellers, B. A., Rohrbaugh, N., & Chen, E. (2014). Forecasting tournaments: Tools for increasing transparency and improving the quality of debate. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(4), 290–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414534257

- Weeks, J. W., & Heimberg, R. G. (2012). Special Issue Positivity Impairments: Pervasive and Impairing (Yet Nonprominent?) Features of Social Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 41(2), 79–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2012.680782

- Westling, B. E., & Öst, L. G. (1999). Brief cognitive behaviour therapy of panic disorder. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 28(2), 49–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/028457199440007

- Westra, H. (2004). Managing resistance in cognitive behavioural therapy: The application of motivational interviewing in mixed anxiety and depression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 33(4), 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070410026426

- Wiemer, M. J. (1975). Cognitive Restructuring Therapy. Scandinavian Journal of Behaviour Therapy, 4(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506077509456024

- Wijma, B., & Wijma, K. (1997). A cognitive behavioural treatment model of vaginismus. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 26(4), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506079708412484

- Zetterqvist, K., Maanmies, J., Ström, L., & Andersson, G. (2003). Randomized controlled trial of internet-based stress management. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 32(3), 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070302316