ABSTRACT

Perfectionism is a transdiagnostic process contributing to the onset and maintenance of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and depression. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to examine the association between perfectionism, and symptoms of anxiety, OCD and depression among young people aged 6–24 years. A systematic literature search retrieved a total of 4,927 articles, with 121 studies included (Mpooled age = ~17.70 years). Perfectionistic concerns demonstrated significant moderate pooled correlations with symptoms of anxiety (r = .37–.41), OCD (r = .42), and depression (r = .40). Perfectionistic strivings demonstrated significant, small correlations with symptoms of anxiety (r = .05) and OCD (r = .19). The findings highlight the substantial link between perfectionistic concerns and psychopathology in young people, and to a smaller extent perfectionistic strivings, anxiety, and OCD. The results indicate the importance of further research on early intervention for perfectionism to improve youth mental health.

Perfectionism is a transdiagnostic process, contributing to the aetiology and maintenance of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and depression (Egan et al., Citation2011). Perfectionism has predominately been measured with the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scales (FMPS; Frost et al., Citation1990; HMPS; Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991). The FMPS (Frost et al., Citation1990) consists of subscales measuring personal standards, concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, parental expectations, and parental criticism. The HMPS (Hewitt & Flett, Citation1991) consists of three subscales: self-oriented perfectionism: setting high personal standards; socially prescribed perfectionism: belief that others expect high standards for the individual and other-oriented perfectionism: belief that others should be perfect. Factor analyses of the scales result in a consistent two-factor structure of perfectionistic strivings (personal standards, self-oriented and other-oriented perfectionism) and perfectionistic concerns (concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, parental expectations and criticism and socially prescribed perfectionism) (Stoeber & Otto, Citation2006).

Another definition of perfectionism is clinical perfectionism, where self-esteem is based on striving for high standards despite negative effects, including symptoms of anxiety, depression and OCD (Shafran et al., Citation2002). It is hypothesised in the cognitive-behavioural model that self-worth based on achievement leads to symptoms of a range of psychological disorders as the individual is continually striving for high standards and engaging in self-criticism regardless of whether personal standards are met (Shafran et al., Citation2002). There have been various cross-sectional and experimental studies that have provided support for the cognitive-behavioural model of clinical perfectionism (see Shafran et al., Citation2023 for a review). Cognitive-behaviour therapy for perfectionism (CBT-P) is based on the cognitive-behavioural model and has been described as the leading evidence-based treatment for perfectionism (Egan, Shafran, et al., Citation2022). CBT-P has demonstrated efficacy in the reduction of symptoms of anxiety and depression in over 15 randomised controlled trials in a recent meta-analysis of studies of CBT-P predominately in adults (Galloway et al., Citation2022). Some authors in defining perfectionism have emphasised the distinction between “healthy” or “adaptive” perfectionism, for example, based on studies finding an association between perfectionistic strivings and positive outcomes (e.g. Stoeber et al., Citation2020). Others have argued there is a need to separate the pursuit of excellence, termed “excellencism” from perfectionism, arguing that over and above excellencism, perfectionism is not associated with adaptive outcomes (Gaudreau et al., Citation2022).

There have been many studies that have examined the association between perfectionism and psychopathology. Limburg et al. (Citation2017) performed a meta-analysis of this literature in adult samples and found both perfectionistic strivings and perfectionistic concerns had significant associations with psychopathology Perfectionistic concerns had higher associations with symptoms of anxiety (r = .35), OCD (r = .30), and depression (r = .39) than perfectionistic strivings had with symptoms of anxiety (r = .14), OCD (r = .14), and depression (r = .11) (Limburg et al., Citation2017). However, Limburg et al. (Citation2017) excluded participants under the age of 18 years therefore generalisations cannot be made to younger people. There has been no meta-analysis to date that has examined the association between perfectionism and psychopathology specifically among young people.

Smith, Sherry, et al. (Citation2018) conducted a meta-analysis including 11 longitudinal studies on the association between perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety, in samples including children, adolescents and adults. There were significant associations between symptoms of anxiety and the different perfectionism subscales, which assess perfectionistic concerns, such as concern over mistakes (r = .11) and doubts about actions (r = .13), in line with Limburg et al. (Citation2017). However, Smith, Sherry, et al. (Citation2018) found inconsistent results with perfectionistic strivings, with non-significant associations between self-oriented perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety (r = .03), but significant, albeit small, associations between personal standards and symptoms of anxiety (r = .08).

There is a need for a meta-analysis to examine the relationships between perfectionistic strivings, concerns, and psychopathology in young people, given debate and disagreement in the literature whether strivings have a positive association with psychopathology (see Limburg et al., Citation2017) or not, and whether age has an influence on the relationship between strivings and concerns. Although Smith, Sherry, et al. (Citation2018) included young people in their meta-analysis, it was not disaggregated by age, which is problematic since pooling associations across children and adults does not clearly inform the relationship in youth. Conducting a meta-analysis on the relationship between perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety, depression and OCD in young people is important to assist in informing treatment, prevention and support strategies for young people with elevated perfectionism (Egan, Wade, et al., Citation2022).

Young people should be considered as a specific population as given the developmental differences across age ranges, it cannot be assumed that psychological theories and treatments that apply to adults directly apply to youth (Bastien et al., Citation2020). Studies examining the relationship between age and perfectionism have demonstrated mixed results, some have shown a positive relationship between total perfectionism and age (e.g. Butt, Citation2010), while others have found no significant relationship with age (e.g. Schweitzer & Hamilton, Citation2002). Sand et al. (Citation2021) argued that age is an important variable to examine in relation to perfectionism given adolescents and young people are at a sensitive point for increases in perfectionism due to awareness of striving to achieve standards and self-consciousness. Sand et al. (Citation2021) conducted a large sample with 10,217 adolescents aged 16–19 years from Norway and found no difference in levels of perfectionism over this age range. However, it would be useful to examine a wider age range of youth in a meta-analysis pooling the relationship between perfectionism dimensions and psychopathology across studies to inform understanding of if there are any age effects.

In this meta-analysis, we defined a young person as between 6 and 24 years. The lower age of 6 years was based on a preliminary search of the lowest age range of studies on the association between perfectionism and psychopathology. The upper age range of 24 years is in accordance with the World Health Organization’s (Citation2014) definition of a young person, as many consider adolescence as extending into the early twenties, including based on evidence that brain maturation does not occur until the mid-20s (Steinberg, Citation2014). Symptoms of anxiety, depression and OCD were examined given they are the most prevalent and commonly seen in clinical practice. Depression has a prevalence rate of 12.9% in adolescents and a high chance of continuing into adulthood, and anxiety is the psychological disorder with the highest prevalence among young people, largely continuing to adulthood (Polanczyk et al., Citation2015). OCD affects 1–2% of children, with 50% of adults diagnosed with OCD reporting the onset of symptoms before 18 years of age (Averna et al., Citation2018). Despite symptoms of eating disorders being a focus of a review in adults (Limburg et al., Citation2017), it was excluded in this meta-analysis due to being examined in a concurrent separate review in young people (Prospero CRD42022324655). The reason for separating out symptoms of eating disorders is that the treatment of eating disorders is distinct from anxiety, depression and OCD, for example, the treatment of choice for eating disorders in adolescents is family-based treatment (Lock & Le Grange, Citation2015) versus CBT for symptoms of anxiety, depression and OCD in youth (Pote, Citation2021).

The aim of the study was to perform a meta-analysis on the associations between perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety, OCD and depression in young people aged 6–24 years. We hypothesised that there would be a medium pooled correlation between perfectionistic concerns and symptoms of anxiety, OCD and depression, and a small pooled correlation between perfectionistic strivings and symptoms of anxiety, OCD, and depression. To examine the potential role of moderators, age, clinical versus a non-clinical sample, and high income versus low-middle-income country (LMIC) of residence were examined. It was predicted relationships between perfectionism dimensions and symptoms would be stronger in clinical versus non-clinical samples based on a previous meta-analysis in adults (Limburg et al., Citation2017). No specific hypotheses were made for age and high versus LMIC country of residence, due to these moderating factors not previously being included in the meta-analysis in adults on the association between perfectionism and psychopathology (Limburg et al., Citation2017).

Method

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: (i) in English, (ii) include a validated measure of symptoms of anxiety, and/or OCD, and/or depression, (iii) include a validated self-report measure of perfectionism which can be classified into strivings and concerns, (iv) include participants aged between 6 and 24 years, if there is no age range provided a mean age between 6 and 24 years, (v) report a correlation between perfectionistic strivings and/or concerns, with symptoms of either anxiety, OCD, and/or depression, or provide results which allow for a correlation to be calculated, and (vi) peer-reviewed. Exclusion criteria were: (i) if a correlation cannot be computed from the results, (ii) qualitative design, (iii) a dissertation, (iv) measured performance and/or sports anxiety or perfectionism, (v) used a sample with clinical or subclinical eating disorder symptoms and/or an eating disorder diagnosis, (vi) measures of perfectionism, and symptoms of anxiety, OCD and/or depression with a Cronbach’s alpha <.70.

Databases and search strategy

PRISMA guidelines were followed (Page et al., Citation2021). The search strategy was registered on PROSPERO on 21 April 2022, prior to the search (CRD42022327290). Databases were searched on 22 May 2022, including Medline, Scopus, Proquest and PsycINFO. The search terms were (perfectionis*) AND (depress* OR anxiet* OR psychopatholog* OR “obsessive compulsive” OR “mental health” OR OCD) AND (child* OR adolescent* OR teen* OR youth OR “young adult” OR college OR undergraduate OR student). There were no restrictions placed on publication date.

Study identification and inter-rater reliability

The study selection process was carried out by JL. If studies were missing specific age information, authors were contacted. If age could not be retrieved, the study was excluded. A secondary reviewer (TC) independently screened 30% of articles at title/abstract and full-text level. Cohen’s kappa was used for inter-rater reliability; poor (k < 0.00), slight (k = 0.00–0.20), fair (k = 0.21–0.40), moderate (k = 0.41–0.60), substantial (k = 0.61–0.80) or almost perfect (k = 0.81–1.00) (Landis & Koch, Citation1977).

Data extraction and management

Division of perfectionism measures into perfectionistic strivings and concerns was based on Limburg et al. (Citation2017) (see table in supplementary materials). Age was coded based on mean age into (0) 6–12.99 years (1) 13–24 years. The rationale for this age split was to separate samples into children and adolescents/young adults, to inform future treatment research, given treatments differ between these two age ranges. For example, treatment is generally parent-led in children aged 6–12.99 years, while for young people aged 13–24 treatment is typically engaged in individually by the young person rather than led by their parents. Anxiety symptoms were categorised into a general category of “anxiety”, referring to anxiety symptoms including, for example, generalised anxiety and social anxiety, largely being based on anxiety symptoms of the anxiety disorders listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.; DSM) criteria (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Test anxiety symptoms were considered as a separate category, which fit under the definition of test anxiety, where extreme distress is experienced in test-taking environments (Abdollahi & Abu Talib, Citation2015), as this was a specific literature in relation to association with this form of anxiety symptoms and perfectionism in young people.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 and Cochran’s Q statistics. Cochran’s Q is calculated using the total squared deviations of the effect sizes from each study, with a significant p-value demonstrating heterogeneity. The I2 shows the percentage of variation which is caused by heterogeneity, with 25% being low, 50% being moderate and 75% being high heterogeneity. When I2 is 60% or greater potential moderators should be considered in a meta-regression to identify sources of heterogeneity (Baker et al., Citation2009).

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies was assessed by JL using the 14 item National Institute of Health (NIH) quality assessment tool for observational and cross-sectional studies (National Institute of Health, Citation2021). The items including quality of the study design, confounding variables, measurement bias and information bias, are rated on a “0 = no” or “1 = yes” scale (see quality rating table in supplementary materials). The quality score was derived by dividing the total number of “yes” responses by the number of items, with scores multiplied by 100 to produce a percentage, where less than 50% = poor, 51–74.99% = fair, and greater than 75% = good.

Publication bias

Publication bias was determined using Egger’s test for plot asymmetry. There was also visual inspections of the funnel plots for asymmetry (Egger et al., Citation1997).

Data analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to determine the associations between perfectionism and psychopathology symptoms. For between groups studies, effect size was calculated using the means and standard deviations between the treatment/clinical group and the control/non-clinical group. In longitudinal studies, only the correlations for the first-time point were imputed. If subscale scores were provided where multiple subscales fit in perfectionistic strivings or concerns, the individual correlations for the subscales were combined and averaged to determine the overall strivings or concerns correlation.

A meta-analysis was conducted to determine the associations between perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety, OCD and depression in JASP (JASP Team, Citation2018). A Hunter-Schmidt random effects model was used to determine the pooled random effects for the studies. Effect sizes were determined using Cohen’s (Citation1992) principles, where small (r = .10), medium (r = .30), and large (r = .50). The 95% confidence intervals were also calculated, mean of the distribution (Z) and standard error (SE). The moderators of age (categorised as 6–12.99 and 13–24) and country of residence (categorised as high income or LMIC) were explored in meta-regressions. We examined potential influential outlying cases using case diagnostics tools in JASP. Cases are identified as influential by Cooks’ distance with the general rule of thumb of any case with a Cook’s distance larger than 4/n (data points) being considered influential (Viechtbauer & Cheung, Citation2010). For associations that had influential cases, we ran pooled effects with and without these cases and comment on any substantial differences in pooled effects.

Results

Study identification and inter-rater reliability

There were 4,927 studies identified, with 2581 duplicates removed (see ). This left 2,346 articles screened at title/abstract by JL, with 30% independently screened by TC. JL and TC were trained by SE in screening and judgement of inclusion and exclusion criteria. There was substantial interrater reliability at title/abstract screening (k = .61). There were 1,478 articles excluded at title/abstract level, resulting in 868 articles screened at full-text level by JL. In articles where the age range and mean age were unclear, authors were contacted. A total of four authors were contacted for six articles, but only one responded. The articles where there was no response were excluded. Only one article was unable to be retrieved. TC screened 30% of articles at full text, with substantial interrater reliability (k = .70). There were 121 eligible articles. Any articles where there was a discrepancy were read at full text by the senior author (SE) until consensus was reached.

Study characteristics

There were 121 articles which met the inclusion criteria (see for study characteristics). Studies included a total of 41,824 participants (M pooled age = ~17.70 years, SD = 4.19, range = 7–24 years). Based on mean age or the midpoint of an age range if mean age was not stated, there were 17 (14%) articles with a sample aged 6–12.99 years, and 91 (76%) articles with a sample aged 13–24 years. The studies were predominately from high-income (HI) countries (n = 93; 78%). Studies were largely from the USA/Canada/Australia/UK/Europe (n = 87; 72%), specifically, USA, n = 38 Canada, n = 311; Europe, n = 8 (Spain, n = 2; Belgium, n = 2; Romania, Portugal, Norway, Italy all n = 1), Australia, n = 6 and the UK, n = 4. There were a small number of studies from high-income nations in the Middle East and Asia (n = 6; 5%; Israel, n = 3; South Korea, Singapore, Japan all n = 1). There were (n = 27; 21%) studies from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) in Asia and South-East Asia (n = 14; 12%, China, n = 11,Footnote1 Malaysia, n = 2; India n = 1), the Middle East (n = 5; 4% - Iran, n = 4; Jordan, n = 1), South America (n = 3, 2%; Ecuador, n = 2; Argentina n = 1) and Europe (n = 5, 2% - Russia, n = 2; Turkey, n = 3). For two studies, the country of residence of participants was not specified. The majority of studies measured symptoms of depression (n = 95), and/or examined symptoms of anxiety (n = 59), and/or OCD (n = 6). Most studies were cross-sectional (n = 104), with a small number of intervention (n = 9) and longitudinal (n = 8) studies (note data was taken from these studies only at baseline). Most samples were non-clinical (n = 117), with only four clinical samples.

Table 1. Study characteristics.

Quality assessment

Study quality ranged from 33.33% to 92.86% (M = 61.84%, SD = 7.88%), indicating that average quality was fair (see supplementary materials for quality assessment ratings for each study). With most studies being cross-sectional in nature, quality was reduced in terms of timing of the exposure, order of measuring the exposure and outcome, number of times exposure was measured and the timeframe to see an association. Almost all studies failed to report a justification for their sample size. Most studies clearly identified their research question or objective and defined their study population and measures well.

Associations of perfectionism

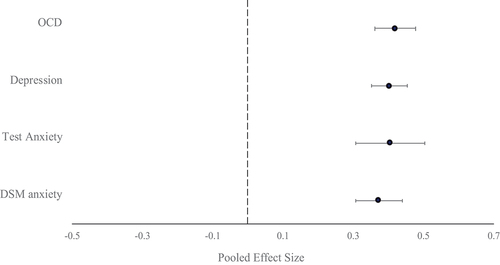

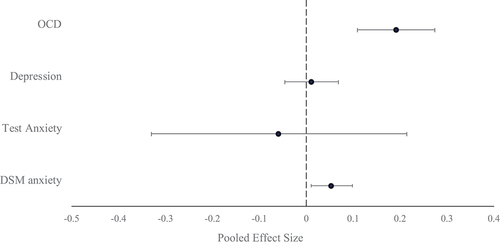

Pooled correlations between symptoms of anxiety, depression, OCD, and perfectionism can be seen in . There were some outliers where studies had smaller pooled correlations, removing these outliers made no difference in the results, so they were retained, see .

Table 2. Pooled correlations between perfectionism dimensions and symptoms.

Anxiety symptoms

There was a significant medium pooled correlation between perfectionistic concerns and symptoms of anxiety (r = .37, 95% CI [.31, .44], p < .001). Due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 97.74%; Q (52) = 2431.09, p < .001), a moderator analysis was conducted, and although age was a significant moderator (β = .18, 95% CI [.02, .35], p = .032), heterogeneity was still high; I2 = 97.47%, ). Specifically, the correlation was weaker for children (r = .22, 95% CI [.03, .42], p = .023) compared to adolescents and young adults (r = .41, 95% CI [.34, .47], p < .001). Further, country income status was not a significant moderator (β = −.07, 95% CI [−.20, .07], p = .310). There was significant publication bias (z = −2.715, p = .007).

Table 3. Moderator analysis results for age and low-middle income country.

There was a significant very small pooled correlation between perfectionistic strivings and anxiety symptoms (r = .05, 95% CI [.01, .10], p = .015), with no significant publication bias (z = −1.242, p = .214). There was high heterogeneity (I2 = 82.87%; Q (30) = 184.92, p < .001), however, in a meta-regression country income status was not a significant predictor (β = −.01, 95% CI [−.105, .089], p = .872; see , ).

Test anxiety symptoms

There was a significant medium pooled correlation between perfectionistic concerns and symptoms of test anxiety (r = .41, 95% CI [.31, .50], p < .001). Publication bias was not significant (z = 0.121, p = .903). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 91.96%; Q (7) = 107.16, p < .001), and country income status was found not to be a significant moderator (β = −.05, 95% CI [−.250, .155], p = .646).

There was no significant association between perfectionistic strivings and symptoms of test anxiety (r = −.06, 95% CI [−.33, .21], p = .674). Publication bias was not significant (z = 0.617, p = .538). A meta-regression was conducted due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 98.27%, 95%; Q (30) = 184.92, p < .001), and country income status was not a significant moderator (β = .075, 95% CI [−.466, .615], p = .786).

Depression symptoms

There was a significant medium pooled correlation between perfectionistic concerns and depressive symptoms (r = .40, 95% CI [.35, .45], p < .001). There was significant publication bias (z = −2.832, p = .005). Due to high heterogeneity (I2 = 97.36%; Q (94) = 3897.93, p < .001), a meta-regression was performed, and age was not a significant moderator (β = .09, 95% CI [−.07, .25], p = .28), nor was country income status (β = −.05, 95% CI [−.15, .06], p = .40)

There was no significant association between perfectionistic strivings and symptoms of depression (r = .01, 95% CI [−.05, .06], p = .830). Publication bias was not significant (z = 0.142, p = .887). Heterogeneity was high (I2 = 94.29%; Q (61) = 1097.84, p < .001); however, country income status was not a significant predictor (β = .00, 95% CI [−0.13, 0.13], p = .995) (see ).

OCD symptoms

There was a significant medium pooled correlation between perfectionistic concerns and OCD symptoms (r = .42, 95% CI [.36, .48], p < .001). Publication bias was not significant (z = 0.529, p = .596). There was low heterogeneity (I2 = 0.00%; Q (5) = 4.33, p = .502). There was a significant small correlation between perfectionistic strivings and OCD symptoms (r = .19, 95% CI [.11, .28], p < .001). There was low heterogeneity (I2 = 16.80%; Q (3) = 4.91, p = .179) and publication bias was not significant (z = 1.744, p = .081). Considering the low levels of heterogeneity and the small number of studies for the associations between perfectionism and OCD symptoms, we did not run any moderator analyses (Baker et al., Citation2009).

Discussion

This was the first meta-analysis to focus on the association between perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety, OCD, and depression specifically among young people. Perfectionistic concerns had medium, pooled correlations with symptoms of anxiety, OCD, test anxiety and depression among young people. Perfectionistic strivings had smaller, though significant associations with symptoms of anxiety and OCD in young people. There was a weaker relationship between perfectionistic concerns and anxiety in children compared to adolescents and young adults, however age was not a significant moderator of the other relationships investigated.

The findings support previous meta-analyses in adult populations, with similar medium pooled correlations between perfectionistic concerns and symptoms of anxiety (current r = .37 vs r = .35), OCD (current r = .42 vs r = .30; Limburg et al., Citation2017) and depression (current r = .40 vs r = .39). Hence, our findings confirm in youth the consistent association between perfectionistic concerns, and symptoms of anxiety, OCD, and depression. Although the data were cross-sectional, so cannot provide support for causality between perfectionism and psychopathology, the results are in line with the cognitive-behavioural model of perfectionism, where self-worth based on striving is associated with adverse consequences, including symptoms of anxiety and depression (Shafran et al., Citation2002). Shafran et al. (Citation2023) recently summarised evidence in support of the model, for example, experimental studies demonstrating the causal link between the induction of perfectionism leading to an increase in negative affect (e.g. Hummel et al., Citation2023; Yiend et al., Citation2011). Further research on the efficacy of CBT-P in youth is warranted to add to existing literature showing the treatment reduces symptoms and, prevents onset of, anxiety and depression in adolescents (e.g. Nehmy & Wade, Citation2015; Shu et al., Citation2020). This is pertinent considering while self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism are significantly reduced following standard CBT for anxiety in clinically anxious children, self-oriented perfectionism was a predictor of poorer treatment outcome at post-treatment and 6-month follow-up (Mitchell et al., Citation2013).

The pattern of results for perfectionistic strivings was interesting. While our results were similar to Limburg et al. (Citation2017) for strivings and OCD symptoms (current r = .19 vs r = .14), we found no relationship between strivings and depressive symptoms (current r = .01 vs r = .11). We also found a smaller, though significant, association between strivings and symptoms of anxiety (current r = .05 vs r = .14) compared to Limburg et al. (Citation2017), but similar to Smith, Sherry, et al. (Citation2018)’s significant, and also small, association (r = .08). A potential reason for the smaller association with symptoms and perfectionistic strivings in the current review is the sample populations. In our review 3% of the studies were clinical samples versus 35% in Limburg et al. (Citation2017). Potentially, in clinical samples perfectionistic strivings may be more problematic than in non-clinical samples. Our findings do not support the notion that perfectionistic strivings are positive (Stoeber & Otto, Citation2006). Our findings in young people echo those of reviews in adults (Limburg et al., Citation2017), perfectionistic strivings are associated with symptoms of psychopathology. Nevertheless, the association between strivings and psychopathology was smaller than for concerns, and we did not find a relationship between perfectionistic strivings and symptoms of test anxiety or depression.

The results from the moderation analyses indicated the relationship between perfectionistic concerns and symptoms of anxiety was weaker in children compared to adolescents and young adults. However, given age was not a significant moderator of any of the other relationships investigated, it is unclear whether age effects in children compared to adolescents and young adults are pertinent in the relationship between perfectionism and psychological symptoms. Further meta-analyses investigating age as a moderator between perfectionism dimensions and psychological symptoms are required to determine if this result is replicated and to further investigate any potential reasons for this difference.

There were several limitations. First, most samples were non-clinical, meaning the results cannot be generalised to clinical populations. We were unable to examine clinical versus non-clinical groups as a moderator due to insufficient studies, and this should be an aim in a future meta-analysis. Future research should address this gap by conducting further research in the area of perfectionism in young people in clinical populations. Second, there were only six studies examining the relationship between perfectionism and symptoms of OCD in young people, hence the conclusions should be interpreted tentatively. Third, in the perfectionism literature, there are a lack of longitudinal studies. Given this review was cross-sectional, we cannot infer causality in the association between perfectionism and symptoms of anxiety, depression, and OCD in young people. Future research should employ longitudinal designs, specifically following youth from adolescents into adulthood and examining impact of perfectionism in development of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and OCD. Finally, we were unable to examine gender due to insufficient data, future meta-analyses should aim to do this to inform any potential gender differences in the relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology in young people.

In conclusion, perfectionistic concerns had a positive association with psychopathology in youth, and perfectionistic strivings had a smaller, though significant relationship with some aspects of anxiety and OCD symptoms. Most treatment research has focused on adults, research should now focus on treatment of perfectionism in youth to provide effective intervention as early as possible to prevent and treat symptoms of anxiety, depression, and OCD.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (55.8 KB)Disclosure statement

Sarah Egan receives royalties for the books ‘Cognitive-Behavioural Treatment of Perfectionism’ and ‘Overcoming Perfectionism: A Self-Help Guide Using Scientically Supported Cognitive Behavioural Techniques’.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2023.2211736

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. One study recruited participants form both China and Canada therefore is included in the count of both high- and low-income studies but not included in the moderator analyses.

References

- Abdollahi, A. (2019). The association of rumination and perfectionism to social anxiety. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Processes, 82(4), 345–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.2019.1608783

- Abdollahi, A., & Abu Talib, M. (2015). Emotional intelligence moderates perfectionism and test anxiety among Iranian students. School Psychology International, 36(5), 498–512. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315603445

- Abdollahi, A., Hosseinian, S., & Asmundson, G. J. (2018). Coping styles mediate perfectionism associations with depression among undergraduate students. The Journal of General Psychology, 145(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2017.1421137

- Affrunti, N. W., & Woodruff-Borden, J. (2016). Negative affect and child internalizing symptoms: The mediating role of perfectionism. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 47(3), 358–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-015-0571-x

- Afshara, H., Roohafza, H., Sadeghi, M., Saadaty, A., Salehi, M., Motamedi, M., Matinpour, M., Isfahani, H. N., & Asadollahi, G. (2011). Positive and negative perfectionism and their relationship with anxiety and depression in Iranian school students. Journal of Research in Medical Sciences, 16(1), 79–86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3063422/

- Aldahadha, B., & Balsamo, M. (2018). The psychometric properties of perfectionism scale and its relation to depression and anxiety. Cogent Psychology, 5(1), 1524324. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1524324

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Arana, F. G., & Furlan, L. (2016). Groups of perfectionists, test anxiety, and pre-exam coping in Argentine students. Personality & Individual Differences, 90, 169–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.001

- Ashby, J. S., Dickinson, W. L., Gnilka, P. B., & Noble, C. L. (2011). Hope as a mediator and moderator of multidimensional perfectionism and depression in middle school students. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(2), 131–139. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00070.x

- Athulya, J., Sudhir, P. M., & Philip, M. (2016). Procrastination, perfectionism, coping and their relation to distress and self-esteem in college students. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology, 42(1), 82–91.

- Averna, R., Pontillo, M., Demaria, F., Armando, M., Santonastaso, O., Pucciarini, M. L., Tata, M. C., Mancini, F., & Vicari, S. (2018). Prevalence and clinical significance of symptoms at ultra high risk for psychosis in children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder: Is there an association with global, role, and social functioning? Brain Sciences, 8(10), 181. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8100181

- Baker, W. L., Michael White, C., Cappelleri, J. C., Kluger, J., & Coleman, C. I. (2009). Understanding heterogeneity in meta-analysis: The role of meta-regression. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 63(10), 1426–1434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02168.x

- Bardone-Cone, A. M., Lin, S. L., & Butler, R. M. (2017). Perfectionism and contingent self-worth in relation to disordered eating and anxiety. Behavior Therapy, 48(3), 380–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2016.05.006

- Bastien, R.J. -B., Jongsma, H. E., Kabadayi, M., & Billings, J. (2020). The effectiveness of psychological interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in children, adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 50(10), 1598–1612. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720002007

- Besharat, M. A., Issazadegan, A., Etemadinia, M., Golssanamlou, S., & Abdolmanafi, A. (2014). Risk factors associated with depressive symptoms among undergraduate students. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 10, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2014.02.002

- Brown, J. R., & Kocovski, N. L. (2014). Perfectionism as a predictor of post-event rumination in a socially anxious sample. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 32(2), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-013-0175-y

- Butt, F. M. (2010). The role of perfectionism in psychological health: A study of adolescents in Pakistan. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 6(4), 125–147. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v6i4.227

- Buzzai, C., Filippello, P., Puglisi, B., Mafodda, A. V., & Sorrenti, L. (2020). The relationship between mathematical achievement, mathematical anxiety, perfectionism and metacognitive abilities in Italian students. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 8(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.6092/2282-1619/mjcp-2595

- Chai, L., Yang, W., Zhang, J., Chen, S., Hennessy, D. A., & Liu, Y. (2020). Relationship between perfectionism and depression among Chinese college students with self-esteem as a mediator. Omega: Journal of Death and Dying, 80(3), 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222819849746

- Chang, E. C. (2013). Perfectionism and loneliness as predictors of depressive and anxious symptoms in Asian and European Americans: Do self-construal schemas also matter? Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(6), 1179–1188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9549-9

- Chang, E. C., Hirsch, J. K., Sanna, L. J., Jeglic, E. L., & Fabian, C. G. (2011). A preliminary study of perfectionism and loneliness as predictors of depressive and anxious symptoms in Latinas: A top-down test of a model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(3), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023255

- Cheng, S. K., Chong, G. H., & Wong, C. W. (1999). Chinese frost multidimensional perfectionism scale: A validation and prediction of self-esteem and psychological distress. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55(9), 1051–1061. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199909)55:9<1051::AID-JCLP3>3.0.CO;2-1

- Christopher, M. M., & Shewmaker, J. (2010). The relationship of perfectionism to affective variables in gifted and highly able children. Gifted Child Today, 33(3), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/107621751003300307

- Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

- Cooks, J. A., & Ciesla, J. A. (2019). The impact of perfectionism, performance feedback, and stress on affect and depressive symptoms. Personality & Individual Differences, 146(1), 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.03.048

- Damian, L. E., Negru-Subtirica, O., Stoeber, J., & Baban, A. (2017). Perfectionistic concerns predict increases in adolescents’ anxiety symptoms: A three-wave longitudinal study. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal, 30(5), 551–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2016.1271877

- Demirtas-Zorbaz, S. (2020). The influence of perfectionism on social competence: Mediating role of social anxiety and academic competence. Contemporary School Psychology, 24(1), 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00231-6

- Diamond, G. M., Greenbaum, M., Shelef, K., & Shahar, G. (2012). Perfectionism and goal setting behaviors: Optimizing opportunities for success and avoiding the potential for failure. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 5(4), 430–443. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2012.5.4.430

- Dittner, A. J., Rimes, K., & Thorpe, S. (2011). Negative perfectionism increases the risk of fatigue following a period of stress. Psychology & Health, 26(3), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903225892

- Egan, S. J., Shafran, R., & Wade, T. D. (2022). A clinician’s quick guide to evidence-based approaches: Perfectionism. The Clinical Psychologist, 26(3), 351–353. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284207.2022.2108315

- Egan, S. J., Wade, T. D., Fitzallen, G., O’Brien, A., & Shafran, R. (2022). A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies of the link between anxiety, depression and perfectionism: Implications for treatment. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 50(1), 89–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465821000357

- Egan, S. J., Wade, T. D., & Shafran, R. (2011). Perfectionism as a transdiagnostic process: A clinical review. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(2), 203–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.009

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. The British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

- Einstein, D. A., Lovibond, P. F., & Gaston, J. E. (2000). Relationship between perfectionism and emotional symptoms in an adolescent sample. Australian Journal of Psychology, 52(2), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530008255373

- Erozkan, A., Karakas, Y., Ata, S., & Ayberk, A. (2011). The relationship between perfectionism and depression in Turkish high school students. Social Behavior and Personality, 39(4), 451–464. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2011.39.4.451

- Etherson, M. E., Smith, M. M., Hill, A. P., Sherry, S. B., Curran, T., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2022). Perfectionism, mattering, depressive symptoms, and suicide ideation in students: A test of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Personality & Individual Differences, 191(1), 100–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111559

- Eum, K., & Rice, K. G. (2011). Test anxiety, perfectionism, goal orientation, and academic performance. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 24(2), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2010.488723

- Eum, K., & Rice, K. G. (2021). Does generic metacognition explain incremental variance in O–C symptoms beyond responsibility and perfectionism? Journal of Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders, 28(1), 100–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2020.100612

- Fedewa, B. A., Burns, L. R., & Gomez, A. A. (2005). Positive and negative perfectionism and the shame/guilt distinction: Adaptive and maladaptive characteristics. Personality & Individual Differences, 38(7), 1609–1619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.09.026

- Ferrari, M., Yap, K., Scott, N., Einstein, D. A., Ciarrochi, J., & van Amelsvoort, T. (2018). Self-compassion moderates the perfectionism and depression link in both adolescence and adulthood. PLos One, 13(2), e0192022. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192022

- Flett, G. L., Besser, A., Davis, R. A., & Hewitt, P. L. (2003). Dimensions of perfectionism, unconditional self-acceptance, and depression. Journal of Rational Emotive and Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 21(2), 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025051431957

- Flett, G. L., Besser, A., & Hewitt, P. L. (2005). Perfectionism, ego defense styles, and depression: A comparison of self-reports versus informant ratings. Journal of Personality, 73(5), 1355–1396. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00352.x

- Flett, G. L., Coulter, L. M., & Hewitt, P. L. (2012). The perfectionistic self-presentation scale—Junior form: Psychometric properties and association with social anxiety in early adolescents. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 27(2), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573511431406

- Flett, G. L., Coulter, L. M., Hewitt, P. L., & Nepon, T. (2011). Perfectionism, rumination, worry, and depressive symptoms in early adolescents. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 26(3), 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573511422039

- Flett, G. L., Druckman, T., Hewitt, P. L., & Wekerle, C. (2012). Perfectionism, coping, social support, and depression in maltreated adolescents. Journal of Rational Emotive and Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 30(2), 118–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-011-0132-6

- Flett, G. L., Galfi-Pechenkov, I., Molnar, D. S., Hewitt, P. L., & Goldstein, A. L. (2012). Perfectionism, mattering, and depression: A mediational analysis. Personality & Individual Differences, 52(7), 828–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.041

- Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Blankstein, K. R., & Mosher, S. W. (1991). Perfectionism, self-actualization, and personal adjustment. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6(5), 147–160. https://www.proquest.com/openview/b8a4f729864f177ba61f0189e44e48c5/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=1819046

- Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Demerjian, A., Sturman, E. D., Sherry, S. B., & Cheng, W. (2012). Perfectionistic automatic thoughts and psychological distress in adolescents: An analysis of the perfectionism cognitions inventory. Journal of Rational Emotive and Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 30(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-011-0131-7

- Flett, G. L., Nepon, T., Hewitt, P. L., & Fitzgerald, K. (2016). Perfectionism, components of stress reactivity, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 38(4), 645–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-016-9554-x

- Flett, G. L., Panico, T., & Hewitt, P. L. (2011). Perfectionism, type a behavior, and self-efficacy in depression and health symptoms among adolescents: Research and reviews. Current Psychology, 30(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-011-9103-4

- Fredrick, S. S., Demaray, M. K., & Jenkins, L. N. (2017). Multidimensional perfectionism and internalizing problems: Do teacher and classmate support matter? The Journal of Early Adolescence, 37(7), 975–1003. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431616636231

- Frost, R. O., Marten, P., Lahart, C., & Rosenblate, R. (1990). The dimensions of perfectionism. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 14, 449-468.

- Frost, R. O., Steketee, G., Cohn, L., & Griess, K. (1994). Personality traits in subclinical and non-obsessive-compulsive volunteers and their parents. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 32(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)90083-3

- Galloway, R., Watson, H. J., Greene, D., Shafran, R., & Egan, S. J. (2022). The efficacy of randomised controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 51(2), 170–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2021.1952302

- Gaudreau, P., Schellenberg, B. J. I., Gareau, A., Klajic, K., & Manoni-Miller, S. (2022). Because excellencism is more than good enough: On the need to distinguish the pursuit of excellence from the pursuit of perfection. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 122(6), 1117–1145. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000411

- Graham, A. R., Sherry, S. B., Stewart, S. H., Sherry, D. L., McGrath, D. S., Fossum, K. M., & Allen, S. L. (2010). The existential model of perfectionism and depressive symptoms: A short-term, four-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 57(4), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020667

- Grenon, E., Bouffard, T., & Vezeau, C. (2020). Familial and personal characteristics profiles predict bias in academic competence and impostorism self-evaluations. Self and Identity, 19(7), 784–803. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2019.1676302

- Harris, P. W., Pepper, C. M., & Maack, D. J. (2008). The relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms: The mediating role of rumination. Personality & Individual Differences, 44(1), 150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.07.011

- Hewitt, P. L., Caelian, C. F., Chen, C., & Flett, G. L. (2014). Perfectionism, stress, daily hassles, hopelessness, and suicide potential in depressed psychiatric adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 36(4), 663–674. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-014-9427-0

- Hewitt, P. L., Caelian, C. F., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., Collins, L., & Flynn, C. A. (2002). Perfectionism in children: Associations with depression, anxiety, and anger. Personality & Individual Differences, 32(6), 1049–1061. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00109-X

- Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 60(3), 456–470. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

- Hewitt, P. L., Smith, M. M., Flett, G. L., Ko, A., Kerns, C., Birch, S., & Peracha, H. (2022). Other-oriented perfectionism in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the other-oriented perfectionism subscale-junior form (OOPjr). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 40(3), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211062009

- Hibbard, D. R., & Davies, K. L. (2011). Perfectionism and psychological adjustment among college students: Does educational context matter? North American Journal of Psychology, 13(2), 187–200. https://www.proquest.com/docview/867838124/fulltextPDF/537EDEEE45EA47D0PQ/1?accountid=10382

- Hinterman, C., Burns, L., Hopwood, D., & Rogers, W. (2012). Mindfulness: Seeking a more perfect approach to coping with life’s challenges. Mindfulness, 3(4), 275–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0091-8

- Hummel, J., Cludius, B., Woud, M. L., Holdenrieder, J., Mende, N., Huber, V., Limburg, K., & Takano, K. (2023). The causal relationship between perfectionism and negative affect: Two experimental studies. Personality & Individual Differences, 200, 191895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111895

- JASP Team. (2018). JASP (version 0.14.1) [Computer software]. https://jasp-stats.org/

- Karababa, A. (2020). The moderating role of hope in the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and anxiety among early adolescents. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 181(2–3), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2020.1745745

- Kenney Benson, G. A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2005). The role of mothers’ use of control in children’s perfectionism: Implications for the development of children’s depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality, 73(1), 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2004.00303.x

- Klibert, J., Lamis, D. A., Collins, W., Smalley, K. B., Warren, J. C., Yancey, C. T., & Winterowd, C. (2014). Resilience mediates the relations between perfectionism and college student distress. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00132.x

- Klibert, J. J., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., & Saito, M. (2005). Adaptive and maladaptive aspects of self-oriented versus socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of College Student Development, 46(2), 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0017

- La Rocque, C. L., Lee, L., & Harkness, K. L. (2016). The role of current depression symptoms in perfectionistic stress enhancement and stress generation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 35(1), 64–86. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2016.35.1.64

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). An application of hierarchical kappa-type statistics in the assessment of majority agreement among multiple observers. Biometrics, 33, 363–374. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529786

- Lee, Y., Ha, J. H., & Jue, J. (2020). Structural equation modeling and the effect of perceived academic inferiority, socially prescribed perfectionism, and parents’ forced social comparison on adolescents’ depression and aggression. Children & Youth Services Review, 108(1), 104–649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104649

- Leenaars, L., & Lester, D. (2007). Construct validity of the helplessness/hopelessness/haplessness scale: Correlations with perfectionism and depression. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 104(1), 152. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.104.1.152-152

- Levine, S. L., Green Demers, I., Werner, K. M., & Milyavskaya, M. (2019). Perfectionism in adolescents: Self-critical perfectionism as a predictor of depressive symptoms across the school year. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 38(1), 70–86. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2019.38.1.70

- Limburg, K., Watson, H. J., Hagger, M. S., & Egan, S. J. (2017). The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(10), 1301–1326. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22435

- Liu, X., Zhang, S., Zheng, R., Yang, L., Cheng, C., & You, J. (2022). Maladaptive perfectionism, daily hassles, and depressive symptoms among first-year college students in China. Journal of American College Health, 70(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2068014

- Lock, J., & Le Grange, D. (2015). Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: A family-based approach. Guilford.

- Luyckx, K., Soenens, B., Goossens, L., Beckx, K., & Wouters, S. (2008). Identity exploration and commitment in late adolescence: Correlates of perfectionism and mediating mechanisms on the pathway to well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(4), 336–361. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.4.336

- Macedo, A., Marques, C., Quaresma, V., Soares, M. J., Amaral, A. P., Araujo, A. I., & Pereira, A. T. (2017). Are perfectionism cognitions and cognitive emotion regulation strategies mediators between perfectionism and psychological distress? Personality & Individual Differences, 119, 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.032

- Mackinnon, S. P., Battista, S. R., Sherry, S. B., & Stewart, S. H. (2014). Perfectionistic self-presentation predicts social anxiety using daily diary methods. Personality & Individual Differences, 56(1), 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.08.038

- Mackinnon, S. P., Sherry, S. B., Antony, M. M., Stewart, S. H., Sherry, D. L., & Hartling, N. (2012). Caught in a bad romance: Perfectionism, conflict, and depression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(2), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027402

- Magson, N. R., Oar, E. L., Fardouly, J., Johnco, C. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2019). The preteen perfectionist: An evaluation of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 50(6), 960–974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00897-2

- Martin, T. R., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Krames, L., & Szanto, G. (1996). Personality correlates of depression and health symptoms: A test of a self-regulation model. Journal of Research in Personality, 30(2), 264–277. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1996.0017

- McGrath, D. S., Sherry, S. B., Stewart, S. H., Mushquash, A. R., Allen, S. L., Nealis, L. J., & Sherry, D. L. (2012). Reciprocal relations between self-critical perfectionism and depressive symptoms: Evidence from a short-term, four-wave longitudinal study. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 44(3), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027764

- McWhinnie, C. M., Abela, J. R., Knauper, B., & Zhang, C. (2009). Development and validation of the revised children’s dysfunctional attitudes scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 48(3), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466508X398952

- Menatti, A. R., Weeks, J. W., Levinson, C. A., & McGowan, M. M. (2013). Exploring the relationship between social anxiety and bulimic symptoms: Mediational effects of perfectionism among females. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(5), 914–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-013-9521-8

- Mitchell, J. H., Newall, C., Broeren, S., & Hudson, J. L. (2013). The role of perfectionism in cognitive behaviour therapy outcomes for clinically anxious children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(9), 547–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.05.015

- Mohammadian, Y., Mahaki, B., Dehghani, M., Mohammadkazem, V., & Lavasani, F. (2018). Investigating the role of interpersonal sensitivity, anger, and perfectionism in social anxiety. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 9(1), 2–8. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_364_16

- Moser, J. S., Slane, J. D., Alexandra Burt, S., & Klump, K. L. (2012). Etiologic relationships between anxiety and dimensions of maladaptive perfectionism in young adult female twins. Depression and Anxiety, 29(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20890

- Nakano, K. (2009). Perfectionism, self-efficacy, and depression: Preliminary analysis of the Japanese version of the almost perfect scale-revised. Psychological Reports, 104(3), 896–908. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.104.3.896-908

- National Institute of Health. (2021). Study Quality Assessment Tools. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- Nealis, L. J., Sherry, S. B., Perrot, T., & Rao, S. (2020). Self-critical perfectionism, depressive symptoms, and HPA-axis dysregulation: Testing emotional and physiological stress reactivity. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 42(3), 570–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-020-09793-9

- Nehmy, T. J., & Wade, T. D. (2015). Reducing the onset of negative affect in adolescents: Evaluation of a perfectionism program in a universal prevention setting. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 67, 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.02.007

- Nepon, T., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Molnar, D. S. (2011). Perfectionism, negative social feedback, and interpersonal rumination in depression and social anxiety. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 43(4), 297–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025032

- Núñez-Peña, M., & Bono, R. (2021). Math anxiety and perfectionistic concerns in multiple-choice assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 46(6), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1836120

- O’Connor, R. C., Rasmussen, S., & Hawton, K. (2010). Predicting depression, anxiety and self-harm in adolescents: The role of perfectionism and acute life stress. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 48(1), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2009.09.008

- Ortega, N. E., Wang, K. T., Slaney, R. B., Hayes, J. A., & Morales, A. (2014). Personal and familial aspects of perfectionism in Latino/a students. The Counseling Psychologist, 42(3), 406–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012473166

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ, (71), n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Patock-Peckham, J., & Corbin, W. (2019). Perfectionism and self-medication as mediators of the links between parenting styles and drinking outcomes. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 10, 100218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2019.100218

- Plominski, A. P., & Burns, L. R. (2018). An investigation of student psychological wellbeing: Honors versus nonhonors undergraduate education. Journal of Advanced Academics, 29(1), 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1932202X17735358

- Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381

- Pote, I. (2021). What science has shown can help young people with anxiety and depression. Wellcome Trust. https://wellcome.org/reports/what-science-has-shown-can-help-young-people-anxiety-and-depression

- Reyes, M. E. S., Layno, K. J. T., Castaneda, J. R. E., Collantes, A. A., Sigua, M. A. D., & McCutcheon, L. E. (2015). Perfectionism and its relationship to the depressive feelings of gifted Filipino adolescents. North American Journal of Psychology, 17(2), 317–322. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/perfectionism-relationship-depressive-feelings/docview/1686089986/se-2

- Rice, K. G., Ashby, J. S., & Slaney, R. B. (2007). Perfectionism and the five-factor model of personality. Assessment, 14(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107303217

- Rice, K. G., Leever, B. A., Christoher, J., & Porter, J. D. (2006). Perfectionism, stress, and social (dis)connection: A short-term study of hopelessness, depression, and academic adjustment among honors students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(4), 524–534. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.524

- Rice, K. G., Leever, B. A., Noggle, C. A., & Lapsley, D. K. (2007). Perfectionism and depressive symptoms in early adolescence. Psychology in the Schools, 44(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20212

- Rice, K. G., & Pence, S. L. (2006). Perfectionism and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology & Behavioral Assessment, 28(2), 103–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-006-7488-4

- Rice, K. G., Tucker, C. M., & Desmond, F. F. (2008). Perfectionism and depression among low-income chronically ill African American and white adolescents and their maternal parent. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 15(3), 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-008-9119-6

- Rousseau, S., Scharf, M., & Smith, Y. (2018). Achievement-oriented and dependency-oriented parental psychological control: An examination of specificity to middle childhood achievement and dependency-related problems. The European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 378–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1265501

- Rudolph, S. G., Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2007). Perfectionism and deficits in cognitive emotion regulation. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive Behavior Therapy, 25(4), 343–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0056-3

- Sand, L., Boe, T., Shafran, R., Stormark, K. M., & Hysing, M. (2021). Perfectionism in adolescence: Associations with gender, age, and socioeconomic status in a Norwegian sample. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 688811. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.688811

- Schweitzer, R. D., & Hamilton, T. K. (2002). Perfectionism and mental health in Australian university students: Is there a relationship? Journal of College Student Development, 43(5), 684–695.

- Shafran, R., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. G. (2002). Clinical perfectionism: A cognitive behavioural analysis. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(7), 773–791. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00059-6

- Shafran, R., Egan, S. J., & Wade, T. D. (2023). Coming of age: A reflection of the first 21 years of cognitive behaviour therapy for perfectionism. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 161, 104258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2023.104258

- Sherry, S. B., Mackinnon, S. P., Macneil, M. A., & Fitzpatrick, S. (2013). Discrepancies confer vulnerability to depressive symptoms: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(1), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030439

- Sherry, S. B., Richards, J. E., Sherry, D. L., & Stewart, S. H. (2014). Self-critical perfectionism is a vulnerability factor for depression but not anxiety: A 12-month, 3-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 52, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2014.05.004

- Sherry, D. L., Sherry, S. B., Hewitt, P. L., Mushquash, A., & Flett, G. L. (2015). The existential model of perfectionism and depressive symptoms: Tests of incremental validity, gender differences, and moderated mediation. Personality & Individual Differences, 76, 104–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.002

- Shu, C. Y., O’Brien, A., Watson, H. J., Anderson, R. A., Wade, T. D., Kane, R. T., Lampard, A., & Egan, S. J. (2020). Structure and validity of the clinical perfectionism questionnaire in female adolescents. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 48(3), 268–279. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465819000729

- Shumaker, E. A., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2009). Perfectionism and social anxiety: Rethinking the role of high standards. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 40(3), 423–433. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2009.04.002

- Sironic, A., & Reeve, R. A. (2012). More evidence for four perfectionism subgroups. Personality & Individual Differences, 53(4), 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.003

- Sironic, A., & Reeve, R. A. (2015). A combined analysis of the frost multidimensional perfectionism scale (FMPS), child and adolescent perfectionism scale (CAPS), and almost perfect scale-revised (APS-R): Different perfectionist profiles in adolescent high school students. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1471–1483. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000137

- Smith, M. M., Saklofske, D. H., Yan, G., & Sherry, S. B. (2017). Does perfectionism predict depression, anxiety, stress, and life satisfaction after controlling for neuroticism?: A study of Canadian and Chinese undergraduates. Journal of Individual Differences, 38(2), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000223

- Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., McLarnon, M. E., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Saklofske, D. H., & Etherson, M. E. (2018). Why does socially prescribed perfectionism place people at risk for depression? A five-month, two-wave longitudinal study of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Personality & Individual Differences, 134, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.05.040

- Smith, M. M., Vidovic, V., Sherry, S. B., Stewart, S. H., & Saklofske, D. H. (2018). Are perfectionism dimensions risk factors for anxiety symptoms? A meta-analysis of 11 longitudinal studies. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2017.1384466

- Soenens, B., Luyckx, K., Vansteenkiste, M., Luyten, P., Duriez, B., & Goossens, L. (2008). Maladaptive perfectionism as an intervening variable between psychological control and adolescent depressive symptoms: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Family Psychology, 22(3), 465. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.22.3.465

- Soreni, N., Streiner, D., McCabe, R., Bullard, C., Swinson, R., Greco, A., Pires, P., & Szatmari, P. (2014). Dimensions of perfectionism in children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 23(2), 136–143. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4032082/

- Steffen, P. R. (2014). Perfectionism and life aspirations in intrinsically and extrinsically religious individuals. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(4), 945–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9692-3

- Steinberg, L. (2014). Age of opportunity: Lessons from the new science of adolescence. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Stoeber, J., Hoyle, A., & Last, F. (2013). The consequences of perfectionism scale: Factorial structure and relationships with perfectionism, performance perfectionism, affect, and depressive symptoms. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 46(3), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/0748175613481981

- Stoeber, J., Madigan, D. J., & Gonidis, L. (2020). Perfectionism is adaptive and maladaptive, but what is the combined effect? Personality & Individual Differences, 161(1), 109846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109846

- Stoeber, J., & Otto, K. (2006). Positive conceptions of perfectionism: Approaches, evidence, challenges. Personality & Social Psychology Review, 10(4), 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1004_2

- Stornaes, A. V., Rosenvinge, J. H., Sundgot-Borgen, J., Pettersen, G., & Friborg, O. (2019). Profiles of perfectionism among adolescents attending specialized elite- and ordinary lower secondary schools: A Norwegian cross-sectional comparative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(10), 2039. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02039

- Sturman, E. D., Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Rudolph, S. G. (2009). Dimensions of perfectionism and self-worth contingencies in depression. Journal of Rational - Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 27(4), 213–231. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-007-0079-9

- Tan, L. S., & Chun, K. Y. N. (2014). Perfectionism and academic emotions of gifted adolescent girls. The Asia - Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0114-9

- Tong, Y., & Lam, S. (2011). The cost of being mother’s ideal child: The role of internalization in the development of perfectionism and depression. Social Development, 20(3), 504–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00599.x

- Vicent, M., Gonzálvez, C., Sanmartín, R., Fernández-Sogorb, A., Cargua-García, N. I., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2019). Perfectionism and school anxiety: More evidence about the 2 × 2 model of perfectionism in an Ecuadorian population. School Psychology International, 40(5), 474–492. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034319859047

- Vicent, M., Inglés, C. J., Gonzálvez, C., Sanmartín, R., Ortega-Sandoval, V. N., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2020). Testing the 2 × 2 model of perfectionism in Ecuadorian adolescent population. Journal of Health Psychology, 25(6), 791–797. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317733536

- Vicent, M., Inglés, C. J., Sanmartín, R., Gonzálvez, C., Delgado, B., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2019). Spanish validation of the child and adolescent perfectionism scale: Factorial invariance and latent means differences across sex and age. Brain Sciences, 9(11), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci9110310

- Viechtbauer, W., & Cheung, M. W. L. (2010). Outlier and influence diagnostics for meta‐analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 1(2), 112–125. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.11

- Walker, M., Thornton, L., De Choudhury, M., Teevan, J., Bulik, C. M., Levinson, C. A., & Zerwas, S. (2015). Facebook use and disordered eating in college-aged women. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(2), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.026

- Wang, K. T., Permyakova, T. M., & Sheveleva, M. S. (2016). Assessing perfectionism in Russia: Classifying perfectionists with the short almost perfect scale. Personality & Individual Differences, 92, 174–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.12.044

- Wang, K. T., Sheveleva, M. S., & Permyakova, T. M. (2019). Imposter syndrome among Russian students: The link between perfectionism and psychological distress. Personality & Individual Differences, 143, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.02.005

- Wang, K. T., Yuen, M., & Slaney, R. B. (2009). Perfectionism, depression, loneliness, and life satisfaction: A study of high school students in Hong Kong. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(2), 249–274. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000008315975

- Wang, Y., & Zhang, B. (2017). The dual model of perfectionism and depression among Chinese university students. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 23(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v23i0.1025

- Weiner, B. A., & Carton, J. S. (2012). Avoidant coping: A mediator of maladaptive perfectionism and test anxiety. Personality & Individual Differences, 52(5), 632–636. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.009

- Wiebe, R. E., & McCabe, S. B. (2002). Relationship perfectionism, dysphoria, and hostile interpersonal behaviors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 21(1), 67–91. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.21.1.67.22406

- Wimberley, T. E., & Stasio, M. J. (2013). Perfectionistic thoughts, personal standards, and evaluative concerns: Further investigating relationships to psychological distress. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37(2), 277–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9462-7

- World Health Organization. (2014). Recognizing adolescence. https://apps.who.int/adolescent/second-decade/section2/page1/recognizing-adolescence.html

- Ye, H. J., Rice, K. G., & Storch, E. A. (2008). Perfectionism and peer relations among children with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 39(4), 415–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-008-0098-5

- Yiend, J., Savulich, G., Coughtrey, A., & Shafran, R. (2011). Biased interpretation in perfectionism and its modification. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(12), 892–900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.10.004

- Yoon, J., & Lau, A. S. (2008). Maladaptive perfectionism and depressive symptoms among Asian American college students: Contributions of interdependence and parental relations. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.92

- You, S., & Yoo, J. (2021). Relations among socially prescribed perfectionism, career stress, mental health, and mindfulness in Korean college students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212248

- Zhang, B., & Cai, T. (2012a). Coping styles and self-esteem as mediators of the perfectionism-depression relationship among Chinese undergraduates. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 40(1), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2012.40.1.157

- Zhang, B., & Cai, T. (2012b). Moderating effects of self-efficacy in the relations of perfectionism and depression. Studia psychologica, 54(1), 15–21.

- Zhang, B., & Cai, T. (2012c). Using SEM to examine the dimensions of perfectionism and investigate the mediating role of self-esteem between perfectionism and depression in China. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22(1), 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.3