Abstract

Drawing on findings from an Economic and Social Research Council-funded research project which investigates how media companies have made the journey from being single sector to digital multi-platform suppliers of content, this article identifies some of the key managerial and economic challenges and opportunities involved in making that transition. It argues that the current migration towards multi-platform has altered not just media industry processes and output but, more fundamentally, it has re-configured the ways in which content is now being conceptualised by media managers. Multi-platform strategies have encouraged a vast expansion in the volumes of media content supplied and made available to media audiences at a time when, generally, the production budgets of media organisations have been tightly constrained. This article considers critically the question of how the transition to a multi-platform environment has facilitated such abundance in output and an apparently miraculous increase in levels of productivity across the media industry. It questions the implications for content and for policy of an ever-growing commitment to multi-platform strategies.

Introduction

In recent years, many media organisations have responded to digital convergence and to growth of the internet by migrating towards a multi-platform approach to production and distribution of content. A multi-platform approach means that new ideas for content are considered in the context of a wide range of distribution possibilities (e.g. online, mobile, interactive games and so on) and not just a single delivery platform such as print or linear television (Doyle, Citation2010; Parker, Citation2007). In the television industry for example, adoption of a multi-platform outlook has been characterised by the development of content-related websites, video on demand (VOD) services and other digital offerings capitalising on popular brands and, also, by the introduction of multi-platform commissioning processes whereby broadcasters will consider any ideas for new content not purely in terms of a channel but rather an array of potential digital outlets (Bennett & Strange, Citation2014; Sørensen, Citation2014). In newspaper and magazine industries, a similar transition has occurred with production increasingly taking place in newsrooms that are converged or “fully integrated” with staff creating products intended, from inception, for distribution on print, online and mobile platforms (Candy, Citation2014).

This article examines the development of multi-platform strategies by United Kingdom (UK) media companies and is broadly concerned with how such strategies are promoting organisational adjustment and renewal, how they are encouraging a new way of conceptualising the business of supplying media, and what the implications of these changes may be for content and content diversity. As more and more media companies migrate to a multi-platform approach, this has encouraged an expansion in the volumes of media content made available to consumers (Lund, Willig, & Blach-Ørsten, Citation2009). The fact that, for most media organisations, resources have been tightly constrained in recent years does not seem to have materially impeded a vast multiplication in the volume of content supplied to audiences across multiple platforms. So a key concern here is to examine how it is that the transition to a multi-platform environment has facilitated such abundance and an apparently miraculous increase in levels of productivity across the media industry?

Focusing on a range of prominent UK media organisations, this article addresses the following questions: How is the switch to a multi-platform approach affecting flows of jobs and investments across industry? In what ways is this approach perceived by companies as enabling them to exploit their resources and serve audience demands more effectively? And, how is content affected by adoption of a multi-platform approach? Findings presented draw on a projectFootnote1 funded by the UK Economic and Social Research Council which investigates and analyses the current migration of media businesses towards diversified digital distribution and multi-platform growth strategies and the impact this has had on economic efficiency and on the nature and diversity of content.

With regard to methods, a multiple case study approach has been adopted focusing on the following organisations (and related product brands): in newspapers, Telegraph Media Group (The Telegraph), News Corporation (The Times) and Pearson (Financial Times); in magazines, Hearst UK (Elle) and Future (Total Film); in television BBC (BBC Three), ITV (ITV1), STV (STV), UKTV (Dave) Viacom International (MTV UK). This particular sample group has facilitated exposure to leading players in the newspaper, television and magazine publishing sectors and enabled evidence gathering with a view towards reflection on how the experience of multi-platform expansion by media companies may vary according to sectoral affiliations.

Research has been conducted mainly through interviews, observation and document analysis. These methods have enabled us to ascertain which economic opportunities have encouraged a growing commitment to multi-platform and what the main perceived challenges related to adjustment may be. With regard to analysis of “factor reallocation” or changes in patterns of employment and investment flows, we have drawn on published data from financial accounts and on information gathered through interviews at each of our case study organisations.

As regards assessment of how the impetus towards multi-platform delivery has impacted on diversity of content, outputs from the selected organisations have been subjected to analysis across a three-year time period. Specified content bundles such as, in television, ITV1 or, in newspapers, The Telegraph or, in magazines, Elle or Total Film, have been analysed periodically in order to allow differences over time in the overall composition of and levels of diversity to be examined. This has involved drawing on techniques used in earlier studies of diversity (De Bens, Citation2007; Picard, Citation2000) based on coding and analysis of media output for a selected sample of prominent products and services.

An extensive literature has developed concerning how organisations in media and communications industries have struggled to adapt to advancing technology and, in particular, their responses to digitisation and the internet have provided a focus in many earlier studies (Chan-Olmsted & Chang, Citation2003; Dennis, Warley, & Sheridan, Citation2006; Gershon, Citation2009; Küng, Citation2008; Küng, Picard & Towse, Citation2008; Meikle & Young, Citation2008; Raviola & Gade, Citation2009). Some earlier studies have focused on multi-platform strategies although typically the context for such analyses is a single sector, for example some looking purely at the experience of newspaper publishers (Goyanes & Dürrenberg, Citation2014) and others at magazines (Champion, Citation2014). Several authors have provided insights into how multi-platform approaches are bringing change to production and consumption of television (Guerrero, Diego, & Pardo, Citation2013; Roscoe, Citation2004; Sørensen, Citation2014; Ytreberg, Citation2009). Some of this work has centred on how Public Service Broadcasting (PSB) organisations such as the BBC have adjusted to become suppliers of public service content across multiple platforms instead of merely broadcasters (Bardoel & Lowe, Citation2007; Bennett, Strange, Kerr, & Medrado, Citation2012; Enli, Citation2008).

Some earlier research highlights how multi-platform delivery has altered modes of consumption of media content (Chyi & Chadha, Citation2012; Westlund, Citation2008) while others address related questions concerning the impact of multi-platform delivery on advertising (Taylor et al., Citation2013). Of particular relevance to our study is earlier work on how the transition to a multi-platform approach has changed processes of production (Bennett & Strange, Citation2014; Quinn, Citation2005; Schlesinger & Doyle, Citation2015). The research presented here is informed by an extensive body of earlier literature concerning the way that newsrooms and news production practices have changed on account of digital convergence (Achtenhagen & Raviola, Citation2009; Deuze, Citation2004; Domingo, Citation2008; García Avilés & Carvajal, Citation2008; Spyridou, Matsiola, Veglis, Kalliris, & Dimoulas, Citation2013) and, related to this, the challenges for newspapers of embedding a fully integrated approach to content production (Bressers, Citation2006; Erdal, Citation2011) and of facilitating innovation (Boczkowski & Ferris, Citation2005; Mico, Masip, & Domingo, Citation2013).

Findings presented here build upon earlier work which is concerned with empirically investigating the connection between patterns of investment and resource usage within media firms and their ability to adjust, perform successfully and derive new revenues in the digital environment (Oliver, Citation2014; Picard, Citation2011). However, this article seeks to extend earlier work about the migration of media suppliers towards a multi-platform approach in two important ways. First, it combines an examination of how multi-platform strategies are impacting on resources and managerial thinking in the media with empirical analysis of how content is affected. This straddles policy-related as well as media business questions and, bearing upon both the economic and social aspects of transformations as a result of digital convergence, the article contributes to a nascent but growing body of multi-disciplinary work in critical media industries studies (Havens, Lotz, & Tinic, Citation2009). Second, in adopting a comparative multiple platform approach, our analysis extends the scope of earlier studies of content diversity which, typically, confine themselves to a single sector (Farchy & Ranaivoson, Citation2011; Van Cuilenburg, Citation2000). Thus, in contrast with earlier work on multi-platform strategies which tends to adopt a single-sector focus, this article offers a comparative multi-sector perspective which seeks to improve understanding of the extent to which digital convergence is presenting opportunities and challenges that are shared right across the media industry.

Adjustment and organisational renewal

The term “multi-platform” is used and understood in differing ways and has potential to raise some thorny issues of definition. In the current context, “multi-platform” refers to a strategic approach where media companies are focused on making or putting together products and services with a view towards delivery and distribution of that content proposition on not just one but across multiple platforms. A significant aspect of a widespread migration towards a multi-platform approach is that, for many firms, it has fundamentally transformed their understanding of what the business of supplying media is about. Not only that, the move to a multi-platform approach has in many cases, altered the sense of organisational identity of media firms. According to the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of Hearst Magazines UK which publishes a large range of magazine titles including Elle, “the way we see the business is that we are not any more a publisher … . Our job is to create a business which is diversified and will enable a connection with our audience around our different brands …” (De Puyfontaine, Citation2012).

The shift to delivery across multiple platforms, including digital platforms which involve two-way connectivity, has entailed and necessitated a new sort of thinking on the part of media managers and strategists whereby, rather than focusing largely on production and distribution of content, a consideration which now occupies considerable importance is how to build and sustain relationships with audiences. In managing a more complex and more dialogical interface with digital end-users, the need for tools that are effective in sustaining engagement is increasing. Therefore branding capabilities have become increasingly important (Ots, Citation2008; Siegert, Gerth, & Rademacher, Citation2011). The importance of brands in securing a foothold with audiences across multiple digital platforms is explained by De Puyfontaine as follows:

As we move from “one-to-many” to “one-to-one” communication … our competitive advantage is based on being the owner of brands. One of their expressions is a weekly or monthly magazine. That’s fine but it is less and less compelling. [The business] we are currently building around these brands is much more comprehensive. (CEO Hearst, Interview, July 2013, London)

In the competitive ecology of digital delivery, ownership and control of content that translates and appeals across multiple platforms is obviously advantageous but so too is ownership of content that is capable of distinguishing itself and that audiences will seek out for themselves across platforms. Recognition of the increasing centrality of brands is by no means confined to magazine publishers. David Booth, former Head of Content and Programming at MTV UK acknowledges that powerful content brands are vital in strengthening the association between a television channel and the character of its content. Therefore the role of the television channel manager has changed and become more focused on identifying what sort of content ideas will work for a brand across multiple distribution platforms and how those platforms can be used to secure audience engagement over an extended time period:

We don’t see ourselves now as a traditional broadcaster – we see ourselves as a brand and our content is a part of a brand experience and our brand is on different platforms … portability of programming is key. (Vice President (VP) of Content and Programming at MTV UK, Interview, October 2011, Glasgow)

It is not only companies’ thinking that has changed but also the balance of their activities, their corporate structures and the flows of investments through which organisational adjustment and renewal is achieved over time. One aspect of our research has been to examine factor reallocation – the incidence and magnitude of investment in new resources (such as equipment and job functions) and the concomitant attrition and disappearance of others that have become obsolete – as a marker of how media companies are re-inventing themselves and how the business as a whole is being transformed as converging digital technology has transformed the nature and composition of factors required to be a successful media supplier (Doyle, Citation2010, Citation2013). Measures of factor reallocation and especially of changing job flows are a yardstick commonly used to assess the intensity with which processes of “creative destruction” may be operating to transform and renew a sector of industry (Caballero, Citation2006). By looking, for example, at the intensity of investment in new job activities versus diminution of roles in other areas that no longer serve a useful purpose, it is possible to gain insights into exactly how a steady ongoing re-orientation towards multi-platform distribution has impacted on the nature and the mix of resources needed by media business. This form of analysis is important since companies that can equip themselves more speedily and effectively than rivals with resources appropriate to the demands of the digital environment will enjoy strategic advantages, at least in the short run (Oliver, Citation2014).

Albeit that systematic data about job flows in the media industry is in short supply and that comparison is hampered by inconsistencies in data between companies and over time, the information set out in based on the The Telegraph, a leading UK newspaper, provides a useful picture of the way that the sector is responding to technological advances. According to the Digital Editor, the total number of staff in The Telegraph’s newsroom remained relatively stable from 2007 to 2012 but at the same time a substantial re-direction of staff effortFootnote2 has taken place in favour of delivery of the title across the internet and on other digital platforms. An estimated 25% of staff effort was devoted to digital distribution at the end of 2012 versus less than 10% five years earlier. And the process of change is still very much ongoing.

Table 1. Changes in staffing at The Telegraph.

Similar changes in patterns of job flows are evident in the magazine publishing sector. Future Publishing is one of the largest magazine publishers in the UK with around 180 titles including Total Film and T3. T3 provides a fairly typical illustration of how patterns of staff activity have shifted. The Managing Director of the Technology and Film and Games Division at Future Publishing estimates that the amount of resource and staff energy invested in delivery of the T3 across the internet and on mobile devices has increased significantly in recent years – see . Whereas an estimated 40% of staff effort was devoted to digital production and distribution in 2013, the equivalent figure four years earlier in 2009 was around 10%. The fact that audience attention has migrated from the glossy print product to online and mobile screen content has been a “driving force” for re-direction of resource and staff effort. However, many advertisers have been slow in transferring their investment to digital platforms and, as transition is ongoing, this has created a dilemma for businesses:

a lot of media companies are in a kind of catch 22 … . How much effort do they put into getting ready for [digital multi-platform delivery]? Because they are not making any money, you know, at all, as yet – but that will come. … the audience is there waiting before the money is. (MD Technology and Film & Games, Future Publishing, Interview, July 2013, London)

Table 2. Changes in staffing at T3.

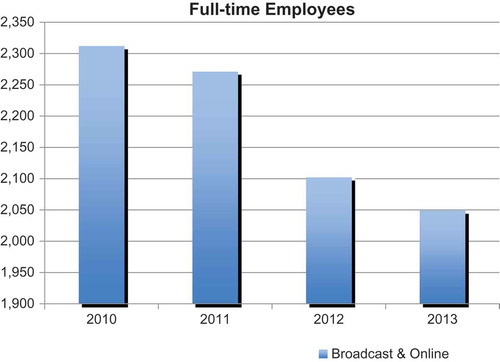

In the UK television broadcasting industry, similar trends are evident (Doyle, Citation2010). Changing patterns of staff activity indicate a substantial level of creative and financial investment in creation and assembly of material for online, mobile and other forms of digital delivery but the level of returns to investment earned from digital delivery has been mixed so far. According to ITV’s Strategy Manager, in 2014 the company needs to employ two “sizeable” teams of digital specialists to manage design, software development and infrastructure issues surrounding delivery of services on digital platforms – these are large teams of 50 to 100 people that did not exist as part of ITV’s workforce a decade ago (interview, April 2014, London). There is evidence of an impetus to invest progressively in development of multi-media and online delivery. But, at the same time, the general trend at ITV has been to cut back on the total number of employees – see . So, again, a re-direction of resources is taking place in favour of delivery on new digital platforms.

Although the exact extent and pace of change through factor reallocation varies from one sector to another and from one organisation to another, the general pattern emerging from our research is one of, across the board, a progressive strengthening of digital skills in areas such as, in television, interface design and software development; and in publishing, digital page editing, video production and interactive graphics. This change has been achieved partly through re-training but also through redundancies and new recruitment. In addition, legacy media companies in all sectors have made substantial investments in the systems and equipment needed to support digital multi-platform production and distribution. In print publishing, extensive investment has been made into content management systems (CMSs) that allow journalists to do more of the work on assembly, headlines, pictures, layout and so on that, in previous years, required separate specialist editorial staff (Doyle, Citation2013). New CMSs also make it easier to publish and distribute across multiple digital as well the traditional print formats. At Hearst UK for example, managing editor Lorraine Candy reports that “the entire Elle team, from sub-editors to heads of department, is [now] trained in CMS, analytics and [search engine optimisation]” (Candy, Citation2014).

Processes of factor reallocation in the UK media industry have involved some notable misjudgments. One example, acknowledged by a senior finance executive at BBC Television (interview, March 2014, London) is the Digital Media Initiatives – a system developed by the corporation for integrating production and archiving but which ultimately proved unsatisfactory and was written off at a cost of some £98 million. Even so, the renewal brought about by changing patterns of investment is also associated with substantial efficiency gains. For the BBC, outsourcing of back-office functions has facilitated more investment in the information technology (IT) and digital skills needed to develop innovative content delivery services on new platforms such as, in particular, the iPlayer. Across the newspaper and magazine publishing sectors, investment in new labour-saving CMSs has enabled a withdrawal of resources from some of the traditional areas of production and assembly of content thus enabling more focus on digital delivery platforms.

From single to multi-platform delivery: perceived opportunities and challenges

Strategies of multi-platform expansion are spurred on by recognition or, in some cases, by hope amongst media managers that opportunities exist both to derive new revenues and to improve the management and cost-effective exploitation of media resources (Doyle, Citation2010, 2014). Findings collected from interviews with senior managers across our sample group confirm that two-way connectivity on digital platforms is a factor commonly regarded as pivotal to unleashing such opportunities. Connectivity on digital platforms is associated with numerous potential benefits including ready access to comprehensive and detailed audience data which may be used to sell behavioural advertising. Improved data about what sorts of content audiences like most or dislike can usefully guide production decisions. In addition, connectivity provides numerous sorts of opportunities for closer two-way engagement with audiences (Ytreberg, Citation2009). The rich rewards on offer to media companies through the availability of more detailed knowledge of target audience niches are summarised by the CEO of Hearst UK thus:

You have all that capacity through data mining to add value [and] efficiency in what you’re providing … [to construct] a special relationship … . This is the new bonanza – that knowledge about people is the new goldmine. (Interview, July 2013, London)

Interactivity, in various ways, enables media suppliers to sustain an appetite for ongoing engagement with specific content properties across platforms. The advantages of forging relationships with and garnering feedback from audiences are well recognised by broadcasters too. At MTV UK for example, links to audiences via social networks and online forums are used to test out new programme ideas. A full range of digital distribution platforms, including social media, are actively deployed and managed in order to construct audiences and to sustain engagement with particular shows and content brands across platforms over long periods of time, as MTV UK’s Head of Digital Strategy explains:

Any of our shows start online, on mobile, on social networking sites and we build an audience. They migrate to television and when they’re not watching on television they can continue to have a relationship with that media property on any platform … .(VP of Digital Strategy, Viacom, Interview, February 2009, London)

Two-way connectivity matters for non-market as well as commercial players. All media companies stand to gain advantage from using connectivity to foster closer engagement with audiences and from drawing on return path data to adjust, improve and, in some cases, to personalise content offerings. That PSB organisations are aware of the potential economic benefits of harvesting “big data” and of using this to more efficiently match a universe of content offerings to demand at the granular level of each individual audience member is confirmed by a senior BBC strategist:

the two-way element [is] the most important part of the value … . Instead of everybody getting the same content, I now know who you are, I can deliver something to you that you will enjoy most. So therefore purely from an economic point of view, I can increase the yield of each piece of content that I create … (Interview, December 2013, London)

However, as one Managing Editor of a UK national newspaper put it (interview, November 2012, London), recognising the potential for use of big data and actually using it to improve how you manage day-to-day processes of content production and advertising delivery are two entirely different things! Our research into the experiences of UK media companies indicates that the journey to multi-platform delivery has generated what is seen by some as a tidal wave of return path data – media companies are awash with it. An interesting finding is that, across the board, most media companies whether engaged in newspaper publishing, television broadcasting or magazine publishing are very challenged by the question of how best to interrogate and exploit that data.

In newspaper publishing, a vast amount of information is now flowing back into newsrooms about reader preferences and naturally this serves to influence content decisions (Schlesinger & Doyle, Citation2015; Turow, Citation2012). At leading newspaper titles such as The Telegraph, the results of real time analysis of consumption patterns amongst the newspaper’s digital users are conveyed to desktop and wall-mounted screens in a constant feedback loop thus enabling editors and journalists to make instantaneous adjustments in the positioning and prominence given to particular stories (Doyle, Citation2013). Magazine publishers are moving in the same direction. At the Elle newsroom or “content hub”, Bluetooth and AirPlay are used to stream audience feedback in the form of elleuk.com’s Google Analytics and Chartbeat data to large wall-mounted screens thus ensuring constant awareness of and responsiveness to reader likes and dislikes amongst editorial staff (Candy, Citation2014).

A potential problem for media businesses is that digital delivery presents ever more effective ways of potentially obviating or making redundant the core function through which media companies have traditionally added value, i.e. by performing an editorialising function and making judgements about what constitutes an attractive parcel of content. Channel controllers decide which programmes will make up a great television schedule. Newspaper editors decide which stories should be in today’s paper. Magazine editors have the specialist knowledge to judge what should be covered in this month’s magazine. To the extent that, as part of the process of adapting to digital delivery, a long-standing reliance on human judgement is eroded by ever-greater use of return path data to support intelligent responsive product design, media organisations may be in danger of undermining their core raison d’être and, in turn, their own long-term viability.

However managers across our sample group were generally emphatic about the need for calls about what is newsworthy to be made by editors and journalists. As the Managing Editor of the Financial Times put it, “editing by numbers” is something that needs to be avoided. Similarly, UK television executives are positive about having extra data about audience preferences but highly sceptical about the prospect of using this data to ever actually automate content decisions.

If understanding how best to use data collected via the digital return path is one area of challenge, yet another problem is that of ensuring that workflows respond to return path data. A key finding of our research is that, in newspaper and magazine publishing, production is still heavily dominated by print cycles with many journalists tending to post copy just as the print deadline approaches (Champion, Citation2014; Doyle, Citation2013). Despite converged newsrooms and despite popular adherence to the rhetoric of “digital first”, the routines and rhythms of the pre-digital era are still very powerfully embedded in cultures of production. Despite increased investment in digital delivery, for many newspaper and magazine titles, content on digital platforms is generally not being refreshed with the sort of frequency needed to ensure that audiences will be keen to take out digital subscriptions. Therefore adaptation of production processes remains still a challenge. Related to this, as reported in fuller detail elsewhere (Doyle, Citation2013), the experience of our sample group suggests that many leading newspapers, broadcasters and magazine publishers are still struggling to achieve the high level of integration between content production staff and digital specialists needed to promote innovation and, in turn, the development of effective new business models for the digital multi-platform era (Doyle, Citation2013).

Expansion of content outputs and diversity

One of the notable corollaries of the widespread transition to a multi-platform approach has been a vast expansion in the volume of content outputs that media companies are supplying and in the opportunities for consumption of media output being made available to media audiences. As print publishers become multi-platform publishers, this entails supplying not only just a paper-based product but also digital editions with additional costly features such as embedded video. For broadcasters, becoming a multi-platform supplier entails delivery of content in new guises and formats suited to the array of digital platforms via which audiences may now choose to access such content. So, as migration towards a multi-platform environment has progressed, the volume of outputs and content consumption opportunities being supplied has vastly increased, reflecting wider cross-platform access to content. However, multi-platform expansion by media companies over recent years has taken place at a time when, on account of economic recession and structural changes, many if not most have been subject to static or even diminishing budgets. How is this possible? How has the transition to a multi-platform environment facilitated such abundance in output and an apparently miraculous increase in levels of cost-efficiency across the industry?

This situation may be reminiscent, for some, of the biblical story of the “loaves and fishes” which tells the tale of when Jesus was surrounded by a crowd of some 5000 followers who were hungry but all that was available was two loaves of bread and five fishes (Mark 6: 30–44, New International Version). The disciples broke up and distributed the loaves and fishes and, miraculously, everyone was able to consume their fill and when the crowd had finished eating an abundance of bread and fish which was left over was gathered up. How had this remarkable and seemingly inexplicable expansion in output occurred?

As far as the expansion of content outputs which has accompanied the migration of media companies to a multi-platform approach is concerned, new equipment and changed work practices provide at least part of the explanation for how this has been achieved at a time of constrained budgets and resources. For example, CMSs, which have been a major focus for investment across the media industry in the UK as elsewhere in recent years, promote improved cost efficiency in at least two ways. First, by guiding how content is constructed and captured in the first place, CMSs facilitate the ready re-formatting and re-versioning of content so that it can be more expediently distributed across multiple delivery platforms. Second, CMSs provide journalists and other digital content producers with the tools needed to perform aspects of the production process (e.g. organising layout, or finding and assembling differing elements such as images and video) that in previous years would have required the input of separate relevant specialists. For the Managing Director (MD) of Commercial at News UK (publisher of The Times and The Sun newspapers) “in terms of editorial production, the content management system is everything” (interview, November 2012, London). So investment in new technology and re-training of staff has, genuinely, reduced the need for labour or encouraged modes of production whereby output is more readily adaptable to distribution across multiple platforms. This has helped restrain the marginal costs associated with expanding the supply of media output across multiple platforms and, in some senses, made media suppliers more cost-efficient.

However, the concept of “cost-efficiency” is not altogether straightforward when used in the context of media provision. As noted by early pioneers in the field of media economics such as Alan Peacock, given the cultural and socio-political significance of media, judgments about the efficiency of one set of arrangements for its provision as opposed to another cannot easily be separated from some sort of judgment about the welfare impacts that the differing patterns of provision would give rise to. Whereas in other sectors judgments about efficiency may legitimately be based on what volumes of output can be generated from any given set of resources, efficient use of media resources is not simply about maximising volumes of output but rather it is about supplying output that really meets the needs and wants of audiences and user-groups. Is the media industry’s transition to a multi-platform approach conducive to an improved experience for audiences?

One aspect of our research has been to investigate empirically what has happened to diversity of output as media companies expand across platforms. To do this, we have focused on selected content bundles as the unit of analysis – e.g. a newspaper such as the Telegraph or a magazine such as NME or a television channel such as BBC Three – an approach used in earlier research (Van Cuilenburg, Citation2000). In the case of each bundle, selected categories of content have been coded and analysed on specified dates in order to assess and compare levels of diversity of content within and across the chosen case studies. Diversity has been assessed using “top four” and “top eight” concentration indices – a limited but at the same time a reasonably simple and objective method of analysing and comparing levels of content diversity (Napoli, Citation2007) – to measure the proportion of output accounted for by the most populous or recurrent individual content items within the service such as, for a television channel, specific shows or, for print media products, particular stories. Albeit that full examination of results is well beyond the scope and ambition of this article, the main preliminary findings provide some useful insights.

Evidence from our analysis of content suggests that, for many media products and services, a relatively small number of content properties will tend to predominate not just on one but on all platforms. At BBC Three, for example, the top content properties – i.e. programmes such as the channel’s flagship comedy series Bad Education or the reality show Hair – account for a very sizeable proportion of total output. Across selected sampling dates in March 2014, the top four content properties accounted for in excess of 50% of the service’s linear channel content and a similarly high proportion of the content offered under the BBC Three banner on the BBC’s main online and mobile platforms – see . Although further testing across time is needed to validate these results, it appears that a relatively small number of individual shows or programme brands reappear regularly and comprise the essence of “BBC Three” across all the main delivery platforms on which the service is distributed.

Table 3. BBC Three content analysis.

Similar trends can be found in print publishing. Content analysis was carried out for a number of magazine and newspaper case studies including the Financial Times. Focusing on the UK company news of the Financial Times, coding and analysis of content was conducted across print and digital platforms in a series of five-day periods. Findings suggest that a relatively small number of stories predominate both in print and digital editions. In a recent sampling period in April 2014 (see ), US pharmaceutical group Pfizer’s takeover approach for Britain’s second-biggest drug manufacturer AstraZeneca was the single most populous content story. More broadly, the top four stories accounted for over 50% of total UK company news content in the print edition of the newspaper and the top four stories accounted for around 40% of digital editions on selected sampling dates in Spring 2014. Comparing these results with findings from a similar content analysis of the Financial Times conducted a year earlier, the proportion of output accounted for by the top handful of stories has increased. Again, further testing is needed to confirm whether this constitutes an exceptional event or a trend. However it appears that the tendency for print and online content to be predominated by just a handful of high profile and high impact content items and for the same handful of stories to predominate across platforms may be on the increase.

Table 4. Content analysis of the Financial Times.

Therefore, the apparently miraculous way that media companies have managed, on relatively fixed resources, to multiply the range and volume of their content outputs is explained by the fact that what they are doing, at least some of the time, is recycling the same output across platforms. Findings gathered from interviews also indicate that the journey to a multi-platform approach has created pressure within media companies towards focusing on a relatively small number of high profile stories and brands because this is the most practical way to meet audience and advertiser demand for multi-platform output from within constrained budgets. According to the former Head of Content and Programming at MTV UK, success in the digital multi-platform era is dependent on having a selective approach towards investment in content:

it’s not about having tons and tons of hours of content. I think every broadcaster has had to really rethink their programme strategies and at the end of the day do bigger picture stuff – doing less but being more cost effective because you’re able to sweat that content across so many different platforms and you’re getting longevity out of it … . (Interview, October 2011, Glasgow)

In order to afford multi-platform delivery and to maximise returns on content investments, editors and television commissioners need to focus on potentially high impact or high return content properties. From the point of view of squeezing additional value from a portfolio of media content assets this approach makes a great deal of sense and deriving more value from content is in fact one of the chief economic motives favouring adoption of multi-platform strategies. However, from an audience perspective, the outcome will not seem entirely beneficial if multi-platform delivery is encouraging more standardisation and uniformity of content with greater emphasis on safe and popular themes and brands. Indeed, one could argue that a relentless re-cycling of content – especially news content – is in many ways harmful to quality and diversity. This raises the question for future research of whether, as the mass migration of media companies to a multi-platform approach follows its course, there may be a case for some form of regulatory intervention conducive to promoting a range of voices in the interests of a democratic order?

Conclusions

Drawing on extensive empirical research, this article examines processes of organisational adjustment which have accompanied the transition to a multi-platform environment and it highlights some of the key managerial and economic challenges and opportunities involved in making that transition. The experience of leading UK media companies indicates that, although the exact extent and pace of change varies from one sector to another and from one organisation to another, renewal has generally entailed significant investment in new equipment, skills and resources needed for digital multi-platform delivery and erstwhile attrition in equipment and functions unsuited to the demands of contemporary digital environment. Our findings highlight the importance attached by media companies to investment in CMSs and in new digital skills such as, in television, interface design and software development; and in publishing, digital page editing, video production and interactive graphics. Given that, as others have argued, the ability of media firms to equip themselves speedily and appropriately to the demands of the digital environment is a source competitive and strategic advantage (Küng, Citation2008; Oliver, Citation2014), empirical analysis of processes of factor reallocation provides insights which are of practical as well as theoretical value and more research in this area is needed.

The ways in which media organisations contend with the challenges of adapting to digitisation and the internet have been the pivotal issue in many earlier studies (Chan-Olmsted & Chang, Citation2003; Dennis et al., Citation2006; Küng, Picard, & Towse, Citation2008; Meikle & Young, Citation2008) but few have focused specifically on multi-platform strategies. Therefore this article extends a limited body of earlier work (Bennett & Strange, Citation2014; Sørensen, Citation2014) by presenting new findings in relation to how the transition to a multi-platform environment is impacting on organisational strategies. These findings highlight some of the key managerial and economic trials and opportunities involved as media companies make the journey from being single sector to digital multi-platform suppliers of content. While some contingencies are sector-specific – e.g. the quest to counteract loss of classified advertising to online rivals is a particularly acute problem for print publishers – many communalities of experience are evident across the media industry. Prominent among these are the challenges faced by most if not all newspapers, television companies and magazine publishers in managing adaptation of production processes and in securing levels of integration between content production and digital specialists conducive to promoting innovation. The experience of leading UK companies suggests that harnessing and exploiting two-way connectivity on digital delivery platforms are seen as pivotal to future growth but, at the same time, associated difficulties – e.g. judging how best to use a “tidal wave” of return path data now potentially available to inform management decision-making – remain considerable.

Fuelling the migration towards a multi-platform approach is the conviction that this will yield economic benefits. For many media suppliers, a major incentive for investment in adjustment to multi-platform is the perception that this now or will soon enable more fulsome and effective exploitation of content assets. Another benefit, as highlighted by interviewees, is the role of connectivity in potentially transforming relationships between media suppliers and audiences and, in turn, providing new creative and business opportunities. Broadly speaking, whether such benefits are sufficient to justify and make sense of adopting a multi-platform strategy depends, for each media company, on how any additional revenues and/or additional audience value generated by the strategy relates to marginal costs?

Earlier theories of convergence have focused on the erosion of traditional sectoral overlaps, and how digital technology has encouraged content flows across platforms and encouraged new modes of audience consumption (Jenkins, Citation2006); how audiences are increasingly involved in content production (Dwyer, Citation2010); and how digitisation has given rise to more shared and networked media experiences (Meikle & Young, Citation2011). Drawing on inter-related findings about economic re-organisation, organisational change and content strategies, this article seeks to go beyond these theories by showing how the current migration towards multi-platform has altered not just media industry processes and output but, more fundamentally, it has re-configured the ways in which content is now being conceptualised. Characteristic of this change is the way that content decisions increasingly are being shaped, right from the outset, by the potential to generate consumer value and returns through multiple forms of expression of that content and via a range of distributive outlets (e.g. online, mobile, interactive games, etc.) including but also moving beyond traditional modes of delivery.

Multi-platform strategies have involved a vast expansion in the volumes of media content supplied and made available to media audiences. The fact that, for most media organisations, resources have been tightly constrained in recent years does not seem to have materially impeded a vast multiplication in the volume of content outputs being supplied to audiences across multiple platforms. How has the transition to a multi-platform environment facilitated such abundance and an apparently miraculous increase in levels of productivity across the media industry? A central concern in this article has been to consider to what extent the widespread adoption of strategies of multi-platform expansion is facilitating opportunities to improve the management and cost-effective exploitation of media resources. Findings presented here indicate that investment in new equipment and re-training has indeed facilitated improvements in cost efficiency by restraining some of the marginal costs associated with expansion in the supply of media output across multiple platforms. However, evidence from our analyses of content, which reinforces the findings of an earlier prescient study of how diversity has been affected by expansion in volumes of news content in Denmark (Lund et al., Citation2009), suggest that practices of extensive recycling and re-use of content by media suppliers which, in many cases, are integral to strategies of multi-platform expansion are also a very major explanatory factor underlying the “miracle of loaves and fishes”.

While the media industry’s migration to a multi-platform approach is unquestionably extending opportunities for consumption of content, our research suggests it is also propelling strategies of brand extension, content re-cycling and the relentless market presence of a limited number of high profile content properties. This adds to earlier research which has found that digital expansion strategies are not necessarily conducive to greater diversity of content nor pluralism (Fenton, Citation2010; Lund et al., Citation2009). Prevalent trends in the media towards expansion and concentration when combined with greater ease, thanks to digitisation, of recycling content across platforms clearly suggests particular challenges for regulators in ensuring choice, access and diversity (Golding, Citation2000, p. 23). Thus, at a time when questions about how media and communications policies ought to change for a converged environment are high on the agenda at national and European level (Valcke, Sükösd, & Picard, Citation2015), the findings of this research are intended to contribute to an improved understanding of implications, including for policy, of an ever-growing commitment to multi-platform.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Acknowledgements

With grateful thanks to all interviewees who participated in this research. This article draws on a three-year research project entitled “Multi-platform Media and the Digital Challenge: Strategy, Distribution and Policy” funded by the Economic and Social Research Council (ES/J011606/1).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gillian Doyle

Gillian Doyle is Professor of Media Economics and Director of the Centre for Cultural Policy Research (CCPR) at the University of Glasgow where she directs Glasgow’s MSc in Media Management. She is lead investigator on a number of projects examining the impact of changing technology on organisational strategies in the media and related questions for public policy. Gillian is former President of the Association for Cultural Economics International (ACEI).

Notes

1. This is a UK Economic and Social Research Council-funded project (ES/J011606/1) entitled “Multi-platform Media and the Digital Challenge: Strategy, Distribution and Policy”. Principal Investigator: Professor Gillian Doyle; Co-Investigator: Professor Philip Schlesinger; Research Associate: Dr Katherine Champion.

2. While complexities and inconsistencies in how differing organisations record staff activities make analysis based purely on reported raw data about employees impossible, use of “staff effort” – a term that denotes an amalgam of the functional resource which is “employees” – has provided a useful basis for comparative analysis.

References

- Achtenhagen, L., & Raviola, E. (2009). Balancing tensions during covergence: Duality management in a newspaper company. International Journal on Media Management, 11(1), 32–41.

- Bardoel, J., & Lowe, G. (2007). From public service broadcasting to public service media, the core challenge. In G. Lowe & J. Bardoel (Eds.), From public service broadcasting to public service media (pp. 9–28). Göteborg: Nordicom.

- Bennett, J., & Strange, N. (2014). Linear legacies: Managing the multiplatform production process. In D. Kompare, J. Derek, & S. Avi (Eds.), Making media work: Cultures of management in the entertainment industries (pp. 63–89). New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Bennett, J., Strange, N., Kerr, P., & Medrado, A. (2012). Multiplatform public service broadcasting: The economic and cultural role of UK digital and TV independents. London: Royal Holloway, University of London.

- Boczkowski, P., & Ferris, J. (2005). Multiple media, convergent processes and divergent products: Organizational innovation in digital media production at a European firm. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 597, 32–47. doi:10.1177/0002716204270067

- Bressers, B. (2006). Promise and reality: The integration of Print and Online versions of major metropolitan newspapers. International Journal on Media Management, 8(3), 134–145. doi:10.1207/s14241250ijmm0803_4

- Caballero, R. (2006). The macroeconomics of specificity and restructuring (Yrjo Jahnsson Lectures). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Candy, L. (2014). Elle 360 in action. Hearst Communications Press Release, London: Hearst Communications. Retrieved from http://www.hearst.com/newsroom/elle-360-in-action

- Champion, K. (2014). Content diversity in a multi-platform context. Paper presented at the MeCCSA Annual Conference, University of Bournemouth, Bournemouth, 8–10 January 2014.

- Chan-Olmsted, S., & Chang, B.-H. (2003). Diversification strategy of global media conglomerates: Examining its patterns and determinants. The Journal of Media Economics, 16(4), 213–233. doi:10.1207/S15327736ME1604_1

- Chyi, H.-I., & Chadha, M. (2012). News on news devices. Journalism Practice, 6(4), 441–439.

- De Bens, E. (Ed.). (2007). Media between culture and commerce. Chicago: Intellect.

- De Puyfontaine, A. (2012), Hearst Magazines, who are they, who are their customers, advertising and online. Speaking at Hearst Magazines 2012 & Beyond. Retrieved from https://soundcloud.com/icrossing-uk/arnaud-de-puyfontaine-hearst

- Dennis, E., Warley, S., & Sheridan, J. (2006). Doing digital: An assessment of the top 25 US media companies and their digital strategies. The Journal of Media Business Studies, 3(1), 33–63.

- Deuze, M. (2004). What is multimedia journalism? Journalism Studies, 5(2), 139–152. doi:10.1080/1461670042000211131

- Domingo, D. (2008). Interactivity in the daily routines of online newsrooms: Dealing with an uncomfortable myth. Journal of Computer Mediated Communication, 13(3), 680–704. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00415.x

- Doyle, G. (2010). From television to multi-platform: More for less or less from more? Convergence, 16(4), 1–19.

- Doyle, G. (2013). Re-invention and survival: Newspapers in the era of digital multiplatform delivery. Journal of Media Business Studies, 10(4), 1–20.

- Dwyer, T. (2010). Media convergence. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Enli, G. (2008). Redefining public service broadcasting: Multi-platform participation. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14(1), 105–120.

- Erdal, I. (2011). Coming to terms with convergence journalism: Cross-media as a theoretical and analytical concept. Convergence, 17(2), 213–223.

- Farchy, J., & Ranaivoson, H. (2011). An international comparison of the ability of television channels to provide diverse programme: Testing the Stirling model in France, Turkey and the United Kingdom. Unesco Institute for Statistics Technical Paper, 6, 77–138.

- Fenton, N. (Ed.). (2010). New media, old news: Journalism and democracy in the digital age. London: Sage.

- García Avilés, A., & Carvajal, M. (2008). Integrated and cross-media newsroom convergence. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 14(2), 221–239.

- Gershon, R. (2009). Telecommunications and business strategy. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Golding, P. (2000). Assessing media content: Why, how and what we learned in a British media content study. In R. Picard (Ed.), Measuring media content, quality and diversity: Approaches and issues in content research (pp. 9–24). Turku: Turku School of Economics and Business Administration.

- Goyanes, M., & Dürrenberg, C. (2014). A taxonomy of newspapers based on multi-platform and paid content strategies: Evidences from Spain. International Journal on Media Management, 16(1), 27–45. doi:10.1080/14241277.2014.900498

- Guerrero, E., Diego, P., & Pardo, A. (2013). Distributing audiovisual contents in the new digital scenario: Multiplatform strategies of the main Spanish TV networks. In M. Friedrichsen & W. Mühl-Benninghaus (Eds.), Handbook of social media management (pp. 349–373). Berlin Heidelberg: Springer.

- Havens, T., Lotz, A., & Tinic, S. (2009). Critical media industry studies: A research approach. Communication, Culture and Critique, 2, 234–253. doi:10.1111/j.1753-9137.2009.01037.x

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Convergence culture: Where old and new media collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Küng, L. (2008). Strategic management in the media. London: Sage.

- Küng, L., Picard, R., & Towse, R. (2008). The internet and the mass media. London: SAGE.

- Lund, A. B., Willig, I., & Blach-Ørsten, M. (Eds.). (2009) Hvor kommer nyhederne fra? Den journalistiske fødekæde i Danmark før og nu [Where does the news come from? The journalistic food chain in Denmark before and now]. Århus: Ajour.

- Meikle, G., & Young, G. (2008). Beyond broadcasting? TV for the twenty-first century. Media International Australia, 126, 67–70.

- Meikle, G., & Young, S. (2011). Media convergence: Networked digital media in everyday life. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mico, J., Masip, P., & Domingo, D. (2013). To wish impossible things: Convergence as a process of diffusion of innovations in an actor-network. International Communication Gazette, 75(1), 118–137. doi:10.1177/1748048512461765

- Napoli, P. (Ed.). (2007). Media diversity and localism: Meaning and metrics. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Oliver, J. (2014). Dynamic capabilities and superior firm performance in the UK media industry. Journal of Media Business Studies, 11(2), 55–77.

- Ots, M. (Ed.). (2008). Media brands and branding, JIBS Research Report Series No. 2008-1, MMTC. Jönkoping: Jönkoping International Business School.

- Parker, R. (2007, September 13). Focus: 360-degree commissioning. Broadcast, p. 11.

- Picard, R. (Ed.). (2000). Measuring media content, quality and diversity: Approaches and issues in content research. Turku, Finland: Turku School of Economics and Business Administration.

- Picard, R. (2011). Mapping digital media: Digitization and media business models. London: Open Society Foundation.

- Quinn, S. (2005). For Australia’s Fairfax Digital, multi-platform delivery is “mandatory”. International Magazine of Newspaper Strategy, Business and Technology, 2005, 1–5.

- Raviola, E., & Gade, P. (2009). Integration of the news and the news of integration: A structural perspective on media changes. Journal of Media Business Studies, 6(1), 1–5.

- Roscoe, J. (2004). Multi-platform event television: Reconceptualizing our relationship with television. The Communication Review, 7, 363–369. doi:10.1080/10714420490886961

- Schlesinger, P., & Doyle, G. (2015). From organizational crisis to multi-platform salvation? Creative destruction and the recomposition of news media. Journalism: Theory, Practice and Criticism, 16(3), 305–323. doi:10.1177/1464884914530223

- Siegert, G., Gerth, M., & Rademacher, P. (2011). Brand identity-driven decision making by journalists and media managers – The MBAC model as a theoretical framework. The International Journal on Media Management, 13(1), 53–70. doi:10.1080/14241277.2010.545363

- Sørensen, I. E. (2014). Channels as content curators: Multiplatform strategies for documentary film and factual content in British public service broadcasting. European Journal of Communication, 29(1), 34–49. doi:10.1177/0267323113504856

- Spyridou, L.-P., Matsiola, M., Veglis, A., Kalliris, G., & Dimoulas, C. (2013). Journalism in a state of flux: Journalists as agents of technology innovation and emerging news practices. International Communication Gazette, 75(1), 76–98. doi:10.1177/1748048512461763

- Taylor, J., Kennedy, R., McDonald, C., Larguinat, L., El Ouarzazi, Y., & Haddad, N. (2013). Is the multi-platform whole more powerful than its separate parts? Measuring the sales effects of cross-media advertising. Journal of Advertising Research, 53(2), 200–211. doi:10.2501/JAR-53-2-200-211

- Turow, J. (2012). The daily you: How the new advertising industry is defining your identity and your worth. Newhaven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Valcke, P., Sükösd, M., & Picard, R. (Eds.). (2015). Media pluralism: Concepts, risks and global trends. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Van Cuilenburg, J. (2000). On measuring media competition and media diversity: Concepts, theories and methods. In R. Picard (Ed.), Measuring media content, quality and diversity: Approaches and issues in content research (pp. 51–84). Turku, Finland: Turku School of Economics and Business Administration.

- Westlund, O. (2008). From mobile phone to mobile device: News consumption on the go. Canadian Journal of Communication, 33(3), 443–463.

- Ytreberg, E. (2009). Extended liveness and eventfulness in multi-platform reality formats. New Media & Society, 11, 467–485. doi:10.1177/1461444809102955