ABSTRACT

Esports represent an increasingly influential and innovative component of the global media business landscape. The ever-evolving ecosystem of dynamic new media is driven by a heterogeneous array of stakeholders that co-create value in online and offline spaces, often described as servicescapes, where innovations are increasingly influential in diverse areas including entrepreneurial business models, media, sports, entertainment, culture, and consumer engagement. In this research, a semi-systematic literature review was undertaken focused on the intersection of the esports ecosystem, servicescapes and innovations. Four clear directions for future research, with questions specific to esports, servicescapes and media were identified. Scholars can utilise these findings to enhance understanding of innovation from the servicescape perspective, with relevance for scholars engaged in business, marketing, and media.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Esports, a form of electronic sports where competitive video gaming is broadcast through various media channels (Hamari & Sjöblom, Citation2017), has received increased media and academic attention during the last decade (Pizzo, et al., Citation2022). Engagement with esports is similar to traditional sports, with professionals competing before audiences in large arenas (Scholz, Citation2020) and the viewing audience playing the various games themselves (in both online and offline spaces) (McCauley et al., Citation2020). Esports is a global industry of media businesses (Scholz, Citation2019) that potentially exceeds 25 billion US dollars in value (Ahn et al., Citation2020). Since 2014, it has experienced rapid expansion (Scholz, Citation2019), evidenced by an ever-increasing audience, sponsors and an increased value of the industry. Various factors have facilitated this growth including new gaming technology, improved connectivity and technological infrastructure developments and live streaming innovation (Ji & Hanna, Citation2020; Wulf et al., Citation2020). Collectively, these technology innovations have been leveraged to reflect a business orientation within the wider gaming industry and esports that has a disruptive impact on our understanding of media business models (Scholz & Stein, Citation2017). With the rise of new technology such as the “metaverse” (Kim, Citation2021; Sax & Ausloos, Citation2021) and the relevance of understanding digital disruption (Maijanen et al., Citation2019), media management can leverage the insights gained from esports to develop sustainable media business models in the digitised society.

As a disruptive and innovative phenomenon rooted in the digital world (Kordyaka et al., Citation2020), esports as media and business has continued to expand to develop their own media landscape and ecosystems (Scholz, Citation2020). Esports has established itself as a disruptive force within the media industry with its influence predicted to grow in the coming years (Hammerschmidt et al., Citation2024).

Due to the nascent nature of esports research, a wealth of multidisciplinary opportunities remain for studying people and systems within this complex digital ecosystem, including business and media studies (Reitman et al., Citation2020). Esports also offers unique opportunities for cross-disciplinary studies (Brock, Citation2023), providing for media management what Oliver (Citation2018) identifies as “an extraordinary opportunity to develop new intellectual insight by bridging previously discrete fields of knowledge” (p. 295). For media organisations, technology and digitisation have impacted the competitive environment and in so doing have blurred “the borders which have encircled media markets” (Kostovska et al., Citation2021, p. 6). As a result, the disruptive and innovative nature of the esports context is increasingly relevant within the context of media management (Roth et al., Citation2023).

Esports is a socio-cultural phenomenon that emerged in a digitised environment, blurring the barriers between areas such as sports, media, entertainment and culture (Scholz, Citation2020). It is both international and regional, consisting of numerous actors and stakeholders exchanging resources and co-creating value (McCauley et al., Citation2020). However, to more effectively understand esports, a broader theoretical perspective is required which examines how resources, such as knowledge, information and innovative technology are shared through various media and across a broad network of stakeholders and actors, including consumers (Marchand & Hennig-Thurau, Citation2013). With a better understanding, it becomes possible to view the vast esports network as a business ecosystem containing a multitude of interdependent actors (Nuseibah & Wolff, Citation2015) playing diverse roles in value co-creation (Carrillo Vera & Aguado Terrón, Citation2019), providing media services and products (Kostovska et al., Citation2021) that drive business model innovation and future profitability (Ji & Hanna, Citation2020). This relevance is accelerating due to the fact that esports acts as a key driver of modern media culture and engagement for younger generations of consumers (Kordyaka et al., Citation2023).

The interactions between actors and stakeholders in business ecosystems have been studied in a variety of contexts (Anggraeni et al., Citation2007; Hollebeek et al., Citation2022; Moore, Citation1993; Viglia et al., Citation2018), yet the space and place in which this interaction takes place to explain how and where value co-creation occurs have been less explored. One theoretical viewpoint to understand where these interactions occur is servicescapes. Servicescapes were originally theorised as the offline (physical) environment where services are delivered (Bitner, Citation1992) but have been expanded to include online services, where they offer “tangible and intangible resources for consumers to develop meaningful and memorable experiences” (Pizam & Tasci, Citation2019, p. 26). The esports servicescape is where esports services are presented (Seo, Citation2013) and includes both offline and online offerings, thus being viewed as a hybrid service experience. The offline offering includes examples such as live stadium events (Jenny et al., Citation2018) and Local Area Network (LAN) parties (Taylor & Witkowski, Citation2010) while playing the game on the internet and actions such as live streaming comprise the online experience, thus being considered part of the modern servicescape (Chen et al., Citation2020).

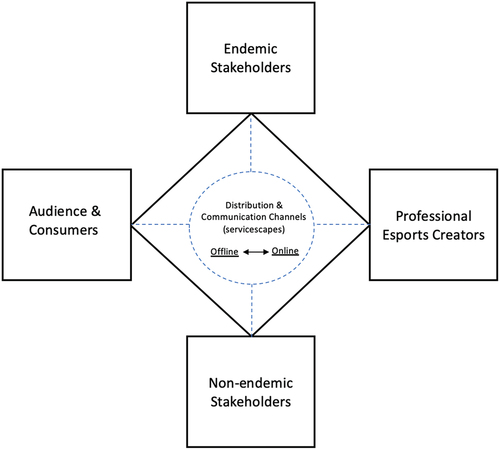

Esports as a context is inherently disruptive (Scholz, Citation2019), driven by digitisation (Stein & Scholz, Citation2016), occurring offline and online simultaneously (McCauley et al., Citation2020), thus servicescapes can serve as a relevant perspective to use when studying the esports ecosystem. For this study, the esports servicescape is defined as the communication and distribution channels existing in both offline arenas and online platforms where multifaceted media engagement with the context occurs. Conceptualising and exploring innovation in an ecosystem, mainly through looking at how the servicescape functions as a medium for innovation, contributes theoretical as well as practical insights. Considering the existing ambiguity in the relationships between media, servicescapes, innovation and esports, the purpose of this research is to (1) examine and create a model of the esports ecosystem with a focus on the servicescape (paying particular attention to media-related issues); (2) through a literature review examine the types of innovation occurring in the esports servicescape to identify suggested areas for future esports research.

Background

The esports ecosystem

Ecosystems are comprised of interdependent actors having diverse roles (Adner & Kapoor, Citation2010), interacting in diverse ways (Nuseibah & Wolff, Citation2015), existing in diverse industries, and filling unique roles in the value-creation process. Understanding these aspects (actors, roles, activities and interactions) is the starting point for understanding any ecosystem (Nuseibah & Wolff, Citation2015). When viewed from a process perspective, there are numerous interrelated actors and affiliations within the esports ecosystem. In esports, traditional actors include game publishers, the players and the audience (Kostovska et al., Citation2021) with new actors such as the Olympic Movement increasingly becoming part of the ecosystem (Lefebvre et al., Citation2024). In the case of a sporting event occurring in a venue in front of fans, value is co-created through an interplay between the players and the audience (Hedlund, Citation2014). When the activities are streamed on the internet or televised live and recorded for future consumption, value is also co-created by the event, its actors and consuming fans both at the venue and online (Woratschek et al., Citation2014). As a result, the core of the esports ecosystem is the games played by the audience and competitions played in front of and/or broadcast to these consumers. Esports empowers consumers to innovate forms of value for themselves, gaming companies, and society at large (Seo et al., Citation2015) with firms focusing on value integration towards the audience (Scholz, Citation2019). Markets such as esports can be viewed as value-creating systems governed by various institutions and actively shaped by the actors (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2017). The audience co-creates value with the firms and with other audience members through a range of activities that range from playing and socialising (McCauley et al., Citation2020), to actively developing a competitive scene in the absence of publisher involvement (Koch et al., Citation2020). The audience co-creates value within games through the act of play (McCauley et al., Citation2023) while also co-creating value within the communities that comprise the wider service ecosystems (Roth et al., Citation2023).

Esports do not always require a physical location for competition to occur and consequently, broadcasting, communication and interaction between stakeholders can occur within the digital component of the servicescape (Anggraeni et al., Citation2007; Kostovska et al., Citation2021; Nuseibah & Wolff, Citation2015). Players, teams and streamers generate revenue through sponsorship, advertising and prize money (Ahn et al., Citation2020) with platforms such as Twitch allowing innovative revenue strategies to be “easily tested by platform holders and streamers alike, making it a space for rapid experimentation and monetization enquiry” (Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019a, p. 9). Esports and the rise of livestreaming on Twitch are inarguably linked and challenge existing assumptions about the business of media production (Sherrick et al., Citation2024). Further disruption to existing media practices can be seen through how games such as Fortnite deliver a free-to-play (freemium) model that seeks to maximise microtransactions from their player base while also acting as a content delivery platform for third parties to offer non-gaming services (Sax & Ausloos, Citation2021). For example, Fortnite acts as a gateway to the metaverse, a network of shared virtual environments and platforms providing a variety of content (Kim, Citation2021). The esports ecosystem represents a media space where a plethora of digital business models are constantly evolving to ensure sustainability (Nyström et al., Citation2022). To create a model of the esports ecosystem with servicescapes at the core, both the core and the nearest outer components are further examined.

The servicescape in the esports ecosystem

The core of the esports ecosystem is the servicescape or “the contextual landscape for service” (Ballantyne & Nilsson, Citation2017, p. 226) in this case, the communication and distribution channels where media engagement occurs in offline and online settings. Considering that ecosystems represent various linkages and relationships between different actors and stakeholders, their existence does not occur in a vacuum. These interactions must have a place or space where, for instance, media communication, co-creation, or activities materialise. While traditionally identified in physical settings, increased digitalisation of activities requires its expansion to include online settings (Helmefalk & Marcusson, Citation2020; Nilsson & Ballantyne, Citation2014). This is of particular importance to esports where the majority of gaming and competitive events occur online. Servicescapes are “consciously designed” to deliver commercial outcomes (Arnould et al., Citation1998, p. 90). Commercial outcomes can, for instance, range from tangible and intangible influences on consumers or employees in commercial contexts, such as time spent, money spent or other outcomes (Turley & Milliman, Citation2000). For video games and esports, content is provided on digital platforms (i.e. the servicescape) where the games are located and distributed. Games are likewise offered through physical distribution channels (e.g. video game consoles). The platforms and servicescape also facilitate communication between players, fans and the public (Marchand & Hennig-Thurau, Citation2013; Wulf et al., Citation2020). The ability to create relationships, value and promote communication between the firm (e.g. gaming companies or teams) and the consumer, or between consumers themselves, such as through a forum, voice chat or in-game messages requires a system that is engaging and facilitates interaction.

The esports servicescape represents a dynamic and ever-evolving context where both simple and radical innovations are driven by a multitude of stakeholders ranging from large media companies to consumers. Media and distribution channels as components of servicescapes can serve as a context for innovation activities (Aal et al., Citation2016). In esports, this innovation is reflected in business models, media strategies and customer engagement (Ji & Hanna, Citation2020) within an ecosystem that allows a plethora of opportunities for value co-creation (Roth et al., Citation2023). Esports can disrupt old media and distribution channels through innovation (Abrate & Menozzi, Citation2020) as the context is characterised as entrepreneurial innovation driven by change-oriented actors (Scholz, Citation2019). For instance, during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the innovation inherent in the digital aspects of esports was demonstrated as the sports industry, in a direct alliance with esports (Ke & Wagner, Citation2020), developed media and marketing content strategies to provide sport consumption opportunities to fans quarantined at home (Goldman & Hedlund, Citation2020). Within 4 days of the lockdown, NASCAR adapted the existing esports format as the eNASCAR iRacing Pro Invitational Series featuring current professional NASCAR drivers alongside the existing esport drivers. Broadcast on both TV and streamed online, the total viewership of both linear and streaming audiences resulted in them being “six of the seven most-watched esports programmes ever on U.S. TV” (Stern, Citation2020). This represents an example of how digital technologies can disrupt and enhance media practices (Maijanen et al., Citation2019), reflecting innovation specifically within the esports servicescape influencing traditional media spheres.

Live streaming, the act of playing games while engaging with an audience online, represents a key aspect of esports that takes place on platforms such as Twitch and YouTube (Hilvert-Bruce et al., Citation2018; Wulf et al., Citation2020). Streaming platforms serve not only as a communication channel between stakeholders or between players but also as a marketing and distribution channel for games and game content (Marchand & Hennig-Thurau, Citation2013). Twitch and its associated streamers drive the “platformization” of cultural production through innovative engagement practices that seek to maximise revenue (Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019a). In esports, the nexus of the interaction between the actors is found in and through servicescapes (Seo, Citation2013) with platforms such as Twitch or Fortnite forced to constantly adapt their practices to attract an audience that has an ever-increasing range of options within the esports servicescape.

The second level in the esports ecosystem

Scholz (Citation2019) emphasises the importance of understanding the actors and the stakeholders within the ecosystem as the esports experience is consumed through two distinct though overlapping or hybrid formats, namely offline (e.g. face-to-face events) and online (e.g. online competitions, streamed events, social media). Stakeholders can thus co-create value in both online and offline settings, often simultaneously.

Stakeholders such as endemic stakeholders, professional esports creators, and non-endemic stakeholders together with the audience and customers are the key stakeholders that impact the core. The role of stakeholders in offline environments is key to value co-creation and market-shaping through communities that host local tournaments and develop institutions to support and develop the next generation of esports (Koch et al., Citation2020; McCauley et al., Citation2020). The actors and stakeholders identified here exist and are embedded within the wider society and culture, interacting in multiple ways, characterised through embedded technology that is increasingly found in the tangible offline “real” world.

Through examining the literature, four common stakeholders within the esports business ecosystem were identified; the audience, endemic stakeholders, non-endemic stakeholders and the professional esport creators (see McCauley et al., Citation2020). Firstly, the audience justifies the existence of other stakeholders and as a result, usually occupies a central stakeholder role (Scholz, Citation2019; Seo, Citation2013). The audience is the most important active stakeholder within esports as they have been the primary driving force for its development over the years (Scholz, Citation2019; Taylor, Citation2012). Esports emerged through the disruptive actions of gaming enthusiasts who created the culture, practices and structures around competitive gaming through LAN parties in the pre-high-speed internet era (Taylor, Citation2012). Modern day grassroots actors continue to work towards legitimising the context within wider society and developing the institutions that ensure a sustainable future (Cestino et al., Citation2023). Recent examples include how the audience, acting as user entrepreneurs, developed the modern competitive scene for Nintendo’s Smash Bros franchise in the absence of the publishers’ involvement (Koch et al., Citation2020). The role of the audience as a driver of innovation is driven by accessibility, connectivity, and ease of use of modern gaming and content creation technologies, positioning them as important stakeholders as both consumers and producers of informal media content. The large volumes of data generated through these digital consumers, which evolve faster than other audiences, also have value for understanding innovations in media management, business models and strategic management (Ji & Hanna, Citation2020).

Secondly, endemic stakeholders in esports include actors such as game publishers, pro teams, players and tournament organisers (Scholz, Citation2019). The game publishers, as the most prominent endemic stakeholders, serve as gatekeepers within esports due to the intellectual property rights of these companies in the form of games (Scholz, Citation2019). Esports events and tournaments are inherently valuable to the publishers as they allow them to demonstrate their offerings and thereby increase revenues (Parshakov et al., Citation2020). Endemic sponsors such as those that produce the technology (headsets, PCs, gaming mice) of esports played an essential role in the development of the early scene (Taylor, Citation2012) that continues to this day.

Thirdly, non-endemic stakeholders such as sponsors and a variety of organisations from outside the esports ecosystem continue to engage with, and shape, the context (Scholz, Citation2020). Esports continues to be pervasive in the offline world with the examples of esports bars similar to traditional sports bars continuing to emerge. Esports creates numerous opportunities for non-endemic sponsors across a broad range of product categories including drinks, cars and fashion to create positive outcomes such as positive attitudes and purchase intentions (Hayward, Citation2019; Huettermann et al., Citation2020). One example of this is franchises such as “Meltdown” or “Kappa” Bar which are attracting audiences who engage with esports but also those who want alternatives to the traditional bar or sports bar formats (McCauley et al., Citation2020). Traditional media and sports organisations, in particular, have made a commitment to engaging with esports (Scholz, Citation2020) as illustrated by the integration of esports within the modern Olympics (Lefebvre et al., Citation2024) and the growing influence within modern professional football (Hammerschmidt et al., Citation2024).

Lastly, professional esport creators represent a range of actors engaging in different practices that produce the media that is central to engagement within the servicescape. Professional gamers and streamers produce game-based content that the audience engages with for a variety of reasons such as learning, connecting or simple enjoyment. Successful livestreamers create parasocial relationships to engage their audiences and maximise financial success (Sherrick et al., Citation2024). This represents the “formal media content” that traditional media markets were built around. Further actors such as game community managers build content and co-create value in both online and offline spaces for the audience to connect around. Increasingly niche yet linked segments such as cosplayers (those who create and wear fantastical game-based costumes) can be seen as creating content that is part of the ecosystem. Esports has its own unique culture built on language, practices, norms, rituals, symbolism and history (Seo, Citation2016) which creates unique professional opportunities. Esports provides opportunities for the audience to stream, view and spend money (Wohn & Freeman, Citation2020), and they are the target for professional content creators. The accessibility of esports through low barriers of entry (Scholz, Citation2019) provides opportunities for the audience to turn their passion for esports into a career, which Seo (Citation2016) views as a form of professionalised consumption. These low barriers are themselves a form of “inclusive innovation” that creates employment opportunities that may otherwise not be feasible (Mortazavi et al., Citation2020). It may be that the audience is acting as prosumers (e.g. those who both produce and consume goods and services, often simultaneously) who become part of the formal media economy in a variety of roles based on their experiences. The ethos of esports is not solely about fun but also about performance and improvement which means esports participants often move beyond games as casual leisure (Seo, Citation2016). Those professionally engaged in esports that the content is created around are labelled as “professional esports creators”, given it is their roles that generate the core content of the context that attracts stakeholders such as sponsors and brands. This could include visible actors such as streamers, shoutcastors (presenters) or players but also the tournament organisers, brand managers, technicians, or coaches.

In line with Scholz (Citation2019), Seo (Citation2013) and McCauley et al. (Citation2020), this study proposes the esport ecosystem model that includes the stakeholders and actors; audience, endemic stakeholders, non-endemic stakeholders and the professional esport creators, with servicescapes at the heart of this ecosystem, highlighting the importance of media in the servicescape itself and its associated innovation activities (Marchand & Hennig-Thurau, Citation2013). represents a model of the esports ecosystem in terms of value creation where various actors and stakeholders co-create value in a complex array of interactions. It differs from the media ecosystem proposed by Kostovska et al. (Citation2021) as it is driven by users in a bottom-up approach that characterises esports while also reflecting the unique nature of esports. Further in this case it is not a media ecosystem that co-evolves around one or several focal firms (Kostovska et al., Citation2021) but instead one where a diverse range of online and offline communication and distribution channels act as the servicescape allowing multifaceted media engagement to facilitate the co-creation practices between a diverse range of actors that drive innovations.

Figure 1. The esports ecosystem with the servicescape as central.Source: adapted from Scholz (Citation2019); Seo (Citation2013); McCauley et al. (Citation2020).

Looking for innovation in the esports servicescape

The esports industry is characterised by a high degree of innovation (Marchand & Hennig-Thurau, Citation2013), applying resources that come from a range of stakeholders in the ecosystem (Moore, Citation1993). The servicescape as central to our model represents the key element in showcasing and distributing the results of esports’ “entrepreneurial innovativeness” (Scholz & Stein, Citation2017). In this increasingly interconnected ecosystem, for clarity of narrative, four stakeholders are focused on to showcase innovative aspects of the context from the servicescape perspective. With each element, this paper will showcase innovations that underline the value of understanding esports within media and management. The role of the games themselves within this model is pervasive, with the multiplicity of existing and emerging titles underpinning each subsequent discussion.

As the esports ecosystem comprises continuous innovation (both radical and simple) that occurs between the different stakeholders, it highlights the need for academics and practitioners to “recognize the disruptive role of esports” (Ke & Wagner, Citation2020, p. 2). Aspects of esports such as the extensions of sporting brands (Bertschy et al., Citation2020), sponsorship (Huettermann et al., Citation2020), and customer engagement (Abbasi et al., Citation2016) warrant examination in the area of media business. To better understand these important questions, an examination of existing research is undertaken to illuminate and organise key themes for future research.

Method

One of the biggest challenges researchers and scholars face, especially in areas that are undergoing rapid change and innovation, is identifying, and keeping up with the current state of research.

To explore innovation occurring in the esports servicescape, a semi-systematic literature review was conducted (Snyder, Citation2019) utilising the key themes of esports ecosystems, servicescapes and innovation to provide a focused future research agenda. This semi-systematic literature review was undertaken using a thematic analysis, similar to McColl-Kennedy et al. (Citation2017). A semi-systematic review differs from a systematic review in that it offers a meta-narrative in contrast to displaying effect sizes, but is also appropriate when reviewing different domains and traditions that may hinder a full systematic review process (Snyder, Citation2019). In line with the aim of this paper, the justification for using a semi-systematic review is that it provides researchers with “[…] the ability to map a field of research, synthesize the state of knowledge, and create an agenda for further research […]” (Snyder, Citation2019, p. 335).

The key terms identified were ecosystem, innovation and servicescape (See ) were combined with several sub-areas and these were used to search for recent journal articles. To conceptually capture the nexus between the (1) esport ecosystem, (2) servicescapes and (3) innovation, several keywords and synonyms needed to be identified to ensure relevant articles were included review. For the (1) esport ecosystem was used as a starting point, using words such as professional esport actors, esport, video game developers, publisher, organisers, professional players, (non)endemic, audience, and consumers. For the (2) servicescape concepts, words, such as platform, online, offline, place, space, media and game, as well as the word servicescape were used. For the (3) innovation similar wordings, such as innovate* were utilised. Thus, the nexus was searched for by combining different keywords from 1, 2 and 3. To illustrate search queries encompassing all keywords; (esport organisers OR play* OR non-endemic OR publish* OR developers OR endemic OR non-endemic OR audience OR consumer*) AND (platform OR online OR offline OR place OR space OR media OR game* OR servicescape) AND (innovati*).

As esports can be viewed as disruptive and ever-changing, particularly during the last few years (Hayduk, Citation2021), the period was limited to articles published between 2018 and the time of writing to maximise the recency and relevance of the research agenda. This resulted in the identification of articles which were then categorised and evaluated based on the journal in which they were published. Thesis work and books were excluded from the results due to the possibility of a lack of peer review. Articles not in English were also excluded. Further, articles were evaluated based on the journal of publication which was required to appear in a leading index such as the Web of Science or ABS list. The document search identified 359 articles associated with each of these search terms and evaluation criteria.

The search and quality assessment followed Snyder’s (Citation2019) recommendations and was conducted by two of the researchers who verified the search terms as well as the result and the papers excluded. This process is illustrated in .

In total, the search generated 40 articles that were common to the search terms i.e. at the nexus of these three areas (see and Appendix 1). Each of these articles was read and analysed considering the purpose of the study to propose new areas for future research. Following the identification of the articles, a thematic analysis was undertaken (Snyder, Citation2019). This analysis is commonly used as a method for analysing and identifying themes or patterns in texts or data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

The process of analysis followed and was inspired by the procedures and phases of Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) is illustrated in Appendix 2. First, articles were read to familiarise the researchers with the content. Subsequently, various findings were systematically coded into words, concepts, or sentences. After summarising and coding the text, the codes and central meanings were reconfigured and (3–4) organised into aggregated (mapped) and latent codes, encapsulating the essence of the findings according to the previously mentioned theories of servicescapes, innovation and esports. (5) These aggregated codes and meanings were then clustered together to illuminate a designated theme. (6) Findings were then discussed according to the themes and potential future avenues they offer (in the next section). Although the content of the articles in Appendix 1, were overlapping to some extent, the themes then enabled the similar categorisation of the articles which reinforced their viability. From the discussion, a table (see ) was generated summarising potential research avenues.

Table 1. Summary of research avenues.

The findings are used to guide future research and from this analysis, the four main areas of future research were identified which are presented in the following section.

Findings, discussion and future research

Based on an examination of the articles, four clear directions for research for understanding innovation from the servicescape perspective, particularly in marketing and media, were found and are summarised in . Additionally, a series of focused research avenues with research questions specific to the esports context are presented with directions also related more generally to servicescapes and media business.

Firstly, the online digital characteristics of the esports context provide opportunities for research associated with online servicescapes and live streaming. Increasingly, streaming is a vital part for creators, not only for promoting new games, or streaming tournaments, but also acting as a natural platform for many actors and stakeholders in the service ecosystem (Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019b). Extensive research has been conducted on Twitch as a platform (see Gasparetto & Safronov, Citation2023; Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019b; Partin, Citation2020; Sjöblom et al., Citation2017, Citation2019; Wulf et al., Citation2020), highlighting its importance for a wide range of stakeholders. As gaming is built on the premise of competition and hence a social activity (Chen et al., Citation2020), limited previous research exists on this aspect, presenting additional research avenues specifically in terms of how live streaming permeates service ecosystems. Additional innovation opportunities and strategies among a diverse range of actors can serve as the focus of this research, such as watchers and players (Diwanji et al., Citation2020). The investigation of cultural perceptions and communities is indicated as this serves as a leading stimulant for innovation through interaction and co-mentorship. As suggested by Klaß (Citation2020), the scope still exists to investigate open innovation within the media industry but in terms of marketing within sports management, streaming and the associated practices represent new ways to engage, track and monetise audiences. Questions connected to online audience engagement further demonstrate that alternate media can potentially develop innovations based on esports practices. Cranmer et al. (Citation2021) emphasised that more research is needed to understand the motivations of audiences’ engagement with these channels and the formation of e-sport communities. While Huang et al. (Citation2024) have shown that informativeness and convenience when live streaming are important for viewer satisfaction and flow experience, Pu et al. (Citation2022) examined instead physical settings and showed that knowledge acquisition, game drama and socialisation were important for attendance, and that event organisers need to be more innovative in physical settings. The innovativeness of the emergent new esports media such as Twitch represents an example of how innovations can transform an industry (Ward & Harmon, Citation2019) with implications for both scholars and practitioners engaged in the study of media business.

A second stream of research identified is an innovation by breaking rules in servicescapes. With the involvement of players in innovative co-creational activities in esports, future research on how this occurs in online servicescapes is necessary as many actors and stakeholders are already well-positioned (DiPietro et al., Citation2018). For example, the rules of a game are determined by the game developer publisher, tournament organisers or the platforms in general, and these boundaries are set for what is possible within the framework of the servicescape. Many major esport titles and genres (e.g. Counter-Strike) are the result of audience-developed changes that give power to players through changing rules, and autonomy for players, thus providing the incentive to be more innovative and participatory. For instance, Abrate and Menozzi (Citation2020) show that there can be a mutual benefit between the producer and user in services where modding is allowed and users can innovate through the freedom to change the rules (e.g. mapmaking, modding etc.), thereby facilitating a demand for the original product.

Further, in understanding how innovation occurs, it would be of interest to explore how innovation activities within servicescapes can be upscaled (DiPietro et al., Citation2018), especially in competitive events. The case of the Super Smash Brothers esports scene being developed by the audience represents the pinnacle of user entrepreneurship in innovating a globally shared experience (Koch et al., Citation2020). The reluctance of Nintendo to engage with the game as an esports title meant that it was built by the audience from the ground up. As Nintendo begins officially engaging with the existing scene it represents a unique case to reflect the call by DiPietro et al. (Citation2018) to investigate scaling up innovative service ecosystems. Platformization (i.e. how technology can infiltrate and connect multiple areas of life via a single technology) of cultural production within services can be seen in how platforms limit the innovation of users and remain under-explored in research (Foxman, Citation2019). Given that everyday users can now be more participatory and creative in how they engage with technology (Freeman et al., Citation2020), scholars should examine if there is a platformization effect hindering engagement and explore how esports enables innovative freedom of cultural production. An interesting perspective that can provide further insight is the concept of sense-breaking (Pizzo, et al., Citation2022) in challenging existing associations in the industry. The example of how esports actors are innovative in shaping regional markets (McCauley et al., Citation2020) provides further evidence of the value of supporting alternate media audiences with opportunities to innovate outside of traditional boundaries.

The analysis thirdly identifies the need for further research into the broad area of innovation related to endemic and non-endemic actors within esports. Sponsorship has become a large revenue stream comprising both endemic and non-endemic sponsors (Cuesta-Valiño et al., Citation2022). While non-endemic sponsors may also gain positive benefits from sponsoring esports (Huettermann et al., Citation2020), the differences between these categories of sponsors are unclear. Research is required to define and clarify the ex- or inclusive criteria for contrasts between these two categories of sponsors. Further, the nature of branding suggests that congruence in the fit between events and sponsors is necessary, but clarity on the nature of congruence in this context is unclear, and as more games and genres develop, this is potentially more complex (Huettermann et al., Citation2020). Flegr and Schmidt (Citation2022) identify similar future research avenues when it comes to esports and marketing, such as endorsement and game-sponsor congruence. Digital events may attract different sponsors from physical events as they have different target markets, with esports attracting younger consumers than traditional sports (Kordyaka et al., Citation2020; Lopez et al., Citation2021). The ever-increasing gambling sponsorships occurring in the industry poses risks to these consumers who are attracted to engage in gambling and experience harm (Biggar et al., Citation2023). To avoid alienating consumers, sponsors need to be strategically selected (Lopez et al., Citation2021) due to their signalling effect on the event such as creating positive brand and event associations (Chien et al., Citation2011). Interestingly, the introduction of an esports activity by a brand is neither reinforcing nor destabilising the identity, if the audience is not involved or interested in the sport (Mühlbacher et al., Citation2021).

In understanding endemic and non-endemic actors, the nature of spillover effects between various actors as well as game genres also requires examination, including how communication and innovation disperse among the different servicescapes. While knowledge sharing among actors has to influence innovation capabilities (Yue et al., Citation2022), the amount of generated data during these events may also provide new insights. Esports events provide data and an appropriate context to potentially examine the hard-to-measure effects of sponsorship (Parshakov et al., Citation2020). Further, the global and online characteristics of esports audiences could provide opportunities to extend research on cross-cultural knowledge on technologically driven co-creation practices between digitally savvy audiences (Roy et al., Citation2019). Esports consumers represent the prosuming early adopters of technology that will represent the future sports fan (Andrews & Ritzer, Citation2018) and media and sports management scholars should explore what aspects of this inherently innovative audience can be applied to traditional sports business realms and other media consumption experiences. However, while the use of existing knowledge and structures of sports management may be beneficial when expanding into the arena of esports, not all existing business and marketing practices may be directly transferred into this context (Pizzo, et al., Citation2022).

Finally, the hybrid nature of esports and technology presents additional research opportunities. The rapid development of new technologies (Jenny et al., Citation2018) provides new business opportunities that by themselves give rise to new business and monetisation models (e.g. Hayduk, Citation2021; Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019a; Partin, Citation2020), smart consumers and smart servicescapes which can lead to new services (Roy et al., Citation2019). The hybridity of intertwining physical and digital (e)sporting activities can be perceived in different levels, for instance, at micro, meso and macro levels in service ecosystems (Kunz et al., Citation2021), or by types of sport-hybridity, such as digitally-supported, augmented, replicated and translated sports (Goebeler et al., Citation2021), all occurring in servicescapes. Future platforms will also present new opportunities, not only for sponsors but also for the professional (e)sports actors, such as teams, to monetise their streams and build their brands, for instance through crowdsourcing (Hayduk, Citation2021). In addition, there are opportunities for media companies to leverage innovative technology (e.g. media digitalisation) within the servicescape, while simultaneously identifying new revenue sources and enhancing profitability (Scholz, Citation2020). In addition, the rapid development of many platforms offers innovation among the actors to build or complement their careers, through these channels. Ji and Hanna (Citation2020) emphasise, for instance, that in-game platforms may be viable to study to investigate the leverage as well as the extent to which esport partners are needed. Virtual reality as an innovative technology has been discussed for competitive gaming for esport (Turkay et al., Citation2021), but also as a way of socially including individuals with a disability to compete (Byers et al., Citation2021). LAN events, such as DreamHack offer a novel context for innovation in hybrid servicescapes. In contrast to other sporting events (arenas), LAN includes (online) participation in many services (Abdolmaleki et al., Citation2023). During these events, other competitive elements exist that can foster innovation and co-creation of value, such as 24-hour competition and developing small games or tournaments that consumers participate in. Ningning et al. (Citation2023) show that willingness to physical activity may be evoked by esports, more research is recommended into how traditional sporting and non-sporting live events can incorporate co-creation of value through participation, besides spectating (e.g. arena games). Thus, this study suggests more research similar to Ruiz and Gandia (Citation2023) on esports events such as tournaments and LANs to understand the ecosystem, the hybridity of such servicescapes and their applicability and value to modern media management scholars. Esports represents one of the first examples of a phenomenon moving from an online medium to integrate with the analogue real world (McCauley et al., Citation2020). As such it provides a unique opportunity for researchers to disentangle the process and gain insights into how innovation drives hybridity.

Implications, limitations, and conclusions

By anchoring a relevant conceptual model, this study has discussed, contrasted, exemplified and proposed future research on innovation within servicescapes that could contribute to overcoming the nascency of esports research and media innovation research (Ratten, Citation2016; Reitman et al., Citation2020). The servicescape perspective provides direction for recent calls to investigate developing questions on the implications of esports for modern media businesses such as prosumers (Andrews & Ritzer, Citation2018), consumer journeys (Houston, Citation2020), user entrepreneurship (Koch et al., Citation2020) the metaverse (Kim, Citation2021) and the augmentation of the sports experience as driven by esports (Cranmer et al., Citation2021). Through shifting the focal point from the audience in ecosystems as identified in previous research to media acting as servicescapes of consumer engagement, additional insights have surfaced. The multiplicity of potential servicescapes identified here indicates a plethora of specific cases and contexts of value to interested researchers engaged in understanding the business of media.

Firstly, this paper has highlighted the importance of various actors and stakeholders and how they have adapted their servicescapes, marketing activities and services to adapt to concurrent shifts of digitalisation and demands of consumers as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic. Secondly, the availability of offline and only servicescapes offers broadens access to the audience through live streaming while simultaneously offering offline avenues for engagement (Wulf et al., Citation2020). Thirdly, innovation provides new monetisation techniques and solutions such as live streaming donations or free-to-play solutions which may broaden the potential user base and co-creation of value (Johnson & Woodcock, Citation2019a). Fourth, communities reflect the bottom-up resource allocation which can be fostered (Scholz & Stein, Citation2017), supported by the hybrid nature of esports and the development of many successful gaming titles. The research avenues identified through the review reflect the complex interplay of these factors to provide focused research directions for interested scholars.

Limitations of this paper include the perspective taken of servicescapes and its application to esports. While examples have been provided of innovations, and the authors have not commented on their success (or lack thereof). The conceptual model may be deliberately simplistic, yet its discussion illustrates the complexity and variety of actors and stakeholders sharing knowledge and resources, as well as determining whether they are endemic (or not). The scope and global nature of the context combined with the nascent stage of associated research mean it is not possible to encompass all aspects of the questions posed here in one study.

Esports has assumed a lot of the traditional formats of existing sports and digital media as it continually negotiates and develops structures and institutions around rapid global growth. These events only add to the value inherent in media business examining the context of esports as these events moved up the timeline of the associated impact and innovations. What is presented here is limited by necessity as esports is truly interdisciplinary as a research topic (Brock, Citation2023) with almost unlimited potential to be examined within media and business. Innovative digital phenomena such as the metaverse increasingly require academic inquiry and conceptualisation in terms of how consumers engage (Kim, Citation2021) with the esports as servicescape perspective representing a valid lens. Characterised by a young digitally savvy audience that engage in both physical and digital spaces, esports represents a future laboratory for understanding the disruption of media business through digital innovations.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Brian McCauley

Brian McCauley, Ph.D., is an assistant professor at Jönköping International Business School in Jönköping, Sweden, the ‘City of DreamHack’. He is the founding Vice Chair of the Esports Research Network and hosts the Esports Research Report podcast. Dr. McCauley’s esports research primarily focusses on marketing, entrepreneurship, and sustainability.

Adele Berndt

Adele Berndt is an Associate Professor at Jönköping International Business School (JIBS), Sweden in Business Administration, focusing on Marketing. She is also an affiliated researcher at the Gordon Institute of Business Science (GIBS) at the University of Pretoria. Adele teaches courses in Consumer Behaviour, Marketing Research and Services’ Marketing at all educational levels. Her research focuses on the interaction of consumers and branding and has authored articles in various marketing journals.

Miralem Helmefalk

Miralem Helmefalk, Ph.D., is interested in consumer psychology, sensory marketing, gamification, and service research. He is currently employed as an assistant professor at the School of Business and Economics at Linnaeus University in Kalmar, Sweden.

David Hedlund

David Hedlund, Ph.D., is a Full Professor at St. John’s University, USA. He is the lead author and editor of the book Esports Business Management and founding Chief Editor of the Journal of Electronic Gaming and Esports. Beyond esports, he publishes research in sport marketing, consumer behavior, sponsorship, analytics, and coaching.

References

- Aal, K., DiPietro, L., Edvardsson, B., Renzi, M. F., & Mugion, R. G. (2016). Innovation in service ecosystems. Journal of Service Management, 27(4), 619–651. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2015-0044

- Abbasi, A., Ting, D. H., & Hlavacs, H. (2016). A revisit of the measurements on engagement in videogames: A new scale development. 15th International Conference on Entertainment Computing (ICEC), Wien, Austria.

- Abdolmaleki, H., Pizzo, A. D., Baker, B. J., Mahmoudi, A., & Ghahfarokhi, E. A. (2023). Esports in emerging markets: A balanced scorecard approach to LAN gaming centers in Iran. Journal of Global Sport Management, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2023.2261444

- Abrate, G., & Menozzi, A. (2020). User innovation and network effects: The case of video games. Industrial and Corporate Change, 29(6), 1399–1414. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtaa030

- Adner, R., & Kapoor, R. (2010). Value creation in innovation ecosystems: How the structure of technological interdependence affects firm performance in new technology generations. Strategic Management Journal, 31(3), 306–333. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.821

- Ahn, J., Collis, W., & Jenny, S. (2020). The one billion dollar myth: Methods for sizing the massively undervalued esports revenue landscape. International Journal of Esports, 1(1), 1–19.

- Andrews, D. L., & Ritzer, G. (2018). Sport and prosumption. Journal of Consumer Culture, 18(2), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517747093

- Anggraeni, E., Den Hartigh, E., & Zegveld, M. (2007, October). Business ecosystem as a perspective for studying the relations between firms and their business networks. ECCON 2007 Annual meeting (pp. 19–21). Veldhoven.

- Arnould, E. J., Price, L. L., & Tierney, P. (1998). Communicative staging of the wilderness servicescape. The Service Industries Journal, 18(3), 90–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069800000034

- Ballantyne, D., & Nilsson, E. (2017). All that is solid melts into air: The servicescape in digital service space. The Journal of Services Marketing, 31(3), 226–235. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-03-2016-0115

- Bertschy, M., Mühlbacher, H., & Desbordes, M. (2020). Esports extension of a football brand: Stakeholder co-creation in action? European Sport Management Quarterly, 20(1), 47–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2019.1689281

- Biggar, B., Zendle, D., & Wardle, H. (2023). Targeting the next generation of gamblers? Gambling sponsorship of esports teams. Journal of Public Health, 45(3), 636–644. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdac167

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: The impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299205600205

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brock, T. (2023). Ontology and interdisciplinary research in esports. Sport, Ethics & Philosophy, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17511321.2023.2260567

- Byers, T., Hayday, E. J., Mason, F., Lunga, P., & Headley, D. (2021). Innovation for positive sustainable legacy from mega sports events: Virtual reality as a tool for social inclusion legacy for Paris 2024 paralympic games. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 3, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2021.625677

- Carrillo Vera, J. A., & Aguado Terrón, J. M. (2019). The eSports ecosystem: Stakeholders and trends in a new show business. Catalan Journal of Communication & Cultural Studies, 11(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1386/cjcs.11.1.3_1

- Cestino, J., Macey, J., & McCauley, B. (2023). Legitimizing the game: How gamers’ personal experiences shape the emergence of grassroots collective action in esports. Internet Research, 33(7), 111–132. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-05-2022-0347

- Chen, Y.-H., Chen, M.-C., & Keng, C.-J. (2020). Measuring online live streaming of perceived servicescape. Internet Research, 30(3), 737–762. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-11-2018-0487

- Chien, P. M., Cornwell, T. B., & Pappu, R. (2011). Sponsorship portfolio as a brand-image creation strategy. Journal of Business Research, 64(2), 142–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2010.02.010

- Cranmer, E. E., Han, D.-I. D., van Gisbergen, M., & Jungt, T. (2021). Esports matrix: Structuring the esports research agenda. Computers in Human Behavior, 117, 106671. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106671

- Cuesta-Valiño, P., Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P., & Loranca-Valle, C. (2022). Sponsorship image and value creation in E-sports. Journal of Business Research, 145, 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.02.084

- DiPietro, L., Edvardsson, B., Reynoso, J., Renzi, M. F., Toni, M., & Mugion, R. G. (2018). A scaling up framework for innovative service ecosystems: Lessons from Eataly and KidZania. Journal of Service Management, 29(1), 146–175. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2017-0054

- Diwanji, V., Reed, A., Ferchaud, A., Seibert, J., Weinbrecht, V., & Sellers, N. (2020). Don’t just watch, join in: Exploring information behavior and copresence on twitch. Computers in Human Behavior, 105, 106221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.106221

- Faas, T., Dombrowski, L., Young, A., & Miller, A. D. (2018). Watch me code: Programming mentorship communities on twitch tv. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction (Vol. 2. No. CSCW. pp. 1–18). https://doi.org/10.1145/3274319

- Flegr, S., & Schmidt, S. L. (2022). Strategic management in eSports–a systematic review of the literature. Sport Management Review, 25(4), 631–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/14413523.2021.1974222

- Foxman, M. (2019). United we stand: Platforms, tools and innovation with the unity game engine. Social Media+ Society, 5(4), 2056305119880177. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119880177

- Freeman, G., McNeese, N., Bardzell, J., & Bardzell, S. (2020). “Pro-amateur”-driven technological innovation: Participation and challenges in indie game development. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 4(GROUP), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1145/3375184

- Gasparetto, T., & Safronov, A. (2023). Streaming demand for eSports: Analysis of counter-strike: Global offensive. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 29(5), 1369–1388. https://doi.org/10.1177/13548565231187359

- Goebeler, L., Standaert, W., & Xiao, X. (2021, January 4–8). Hybrid sport configurations: The intertwining of the physical and the digital. Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii.

- Goldman, M. M., & Hedlund, D. P. (2020). Rebooting content: Broadcasting sport and esports to homes during COVID-19. International Journal of Sport Communication, 13(3), 370–380. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsc.2020-0227

- Hamari, J., & Sjöblom, M. (2017). What is eSports and why do people watch it? Internet Research, 27(2), 211–232. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-04-2016-0085

- Hammerschmidt, J., Haski, S., Kraus, S., & Heinzen, M. (2024). New media, new possibilities? How esports strategies guide an ambidextrous understanding of tradition and innovation in the German Bundesliga. Journal of Media Business Studies, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2024.2340310

- Hayduk, T. M. (2021). Kickstart my market: Exploring an alternative method of raising capital in a new media sector. Journal of Media Business Studies, 18(3), 155–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2020.1800310

- Hayward, A. (2019). Drinks, tech, cars, and fashion: Non-endemic sponsor recap for Q3 2019. The Esports Observer. Retrieved April 5, 2019, from https://esportsobserver.com/non-endemic-sponsor-q319/

- Hedlund, D. P. (2014). Creating value through membership and participation in sport fan consumption communities. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(1), 50–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.865775

- Helmefalk, M., & Marcusson, L. (2020). Utilizing gamification in servicescapes for improved consumer engagement. IGI Global.

- Hilvert-Bruce, Z., Neill, J. T., Sjöblom, M., & Hamari, J. (2018). Social motivations of live-streaming viewer engagement on twitch. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.013

- Hollebeek, L. D., Urbonavicius, S., Sigurdsson, V., Clark, M. K., Parts, O., & Rather, R. A. (2022). Stakeholder engagement and business model innovation value. The Service Industries Journal, 42(1–2), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642069.2022.2026334

- Houston, A. (2020). ESL extends partnership with DHL for 2020. ESL. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://www.eslgaming.com/article/esl-extends-partnership-dhl-2020-4341

- Huang, T.-L., Liao, G.-Y., Cheng, T. C. E., Chen, W.-X., & Teng, C.-I. (2024). Tomorrow will be better: Gamers’ expectation and game usage. Computers in Human Behavior, 151, 108021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2023.108021

- Huettermann, M., Trail, G. T., Pizzo, A. D., & Stallone, V. (2020). Esports sponsorship: An empirical examination of esports consumers’ perceptions of non-endemic sponsors. Journal of Global Sport Management, 8(2), 524–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/24704067.2020.1846906

- Jenny, S. E., Keiper, M. C., Taylor, B. J., Williams, D. P., Gawrysiak, J., Manning, R. D., & Tutka, P. M. (2018). eSports venues: A new sport business opportunity. Journal of Applied Sport Management, 10(1), 34–49. https://doi.org/10.18666/JASM-2018-V10-I1-8469

- Ji, Z., & Hanna, R. C. (2020). Gamers first–how consumer preferences impact eSports media offerings. The International Journal on Media Management, 22(1), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2020.1731514

- Johnson, M. R., & Woodcock, J. (2019a). “And today’s top donator is”: How live streamers on twitch. tv monetize and gamify their broadcasts. Social Media+ Society, 5(4), 2056305119881694. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119881694

- Johnson, M. R., & Woodcock, J. (2019b). The impacts of live streaming and twitch. tv on the video game industry. Media Culture & Society, 41(5), 670–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443718818363

- Ke, X., & Wagner, C. (2020). Global pandemic compels sport to move to esports: Understanding from brand extension perspective. Managing Sport and Leisure, 27(1–2), 152–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/23750472.2020.1792801

- Kim, J. (2021). Advertising in the metaverse: Research agenda. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 21(3), 141–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/15252019.2021.2001273

- Klaß, N. (2020). Open innovation in media innovation research–a systematic literature review. Journal of Media Business Studies, 17(2), 190–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2020.1724498

- Koch, N., Pongratz, S., McCauley, B., & Achtenhagen, L. (2020). ‘Smashing it’: How user entrepreneurs drive innovation in esports communities. International Journal of Esports, 1(1), 1–15.

- Kordyaka, B., Jahn, K., & Niehaves, B. (2020). To diversify or not? Uncovering the effects of identification and media engagement on franchise loyalty in eSports. The International Journal on Media Management, 22(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2020.1732982

- Kordyaka, B., Kruse, B., & Niehaves, B. (2023). Brands in eSports–generational cohorts, value congruence and media engagement as antecedents of brand sustainability. Journal of Media Business Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2023.2225298

- Kostovska, I., Raats, T., Donders, K., & Ballon, P. (2021). Going beyond the hype: Conceptualising “media ecosystem” for media management research. Journal of Media Business Studies, 18(1), 6–26. :https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2020.1765668

- Kunz, R. E., Roth, A., & Santomier, J. P. (2021). A perspective on value co-creation processes in eSports service ecosystems. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 12(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-03-2021-0039

- Kunz, R. E., Roth, A., & Santomier, J. P. (2022). A perspective on value co-creation processes in eSports service ecosystems. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 12(1), 29–53.

- Lefebvre, F., Besombes, N., & Chanavat, N. (2024). Analysis of the interactions among core stakeholders of the Olympic media ecosystem: Conditions for a value creation proposition of the Olympic virtual series. Journal of Media Business Studies, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2024.2335710

- Lopez, C., Pizzo, A. D., Gupta, K., Kennedy, H., & Funk, D. C. (2021). Corporate growth strategies in an era of digitalization: A network analysis of the national basketball association’s 2K league sponsors. Journal of Business Research, 133, 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.068

- Maijanen, P., von Rimscha, B., & Głowacki, M. (2019). Beyond the surface of media disruption: Digital technology boosting new business logics, professional practices and entrepreneurial identities. Journal of Media Business Media Studies, 16(3), 163–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2019.1700095

- Marchand, A., & Hennig-Thurau, T. (2013). Value creation in the video game industry: Industry economics, consumer benefits, and research opportunities. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 27(3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intmar.2013.05.001

- McCauley, B., Scholz, T., & Tierney, K. (2023, January 3–6). That birdie feeling: Understanding the role of LAN organizers in maintaining a gaming community. 56th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii.

- McCauley, B., Tierney, K., & Tokbaeva, D. (2020). Building a regional offline eSports market: Understanding how jönköping the ‘city of DreamHack’ takes URL to IRL. International Journal of Media Management, 22(1), 30–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2020.1731513

- McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Snyder, H., Elg, M., Witell, L., Helkkula, A., Hogan, S. J., & Anderson, L. (2017). The changing role of the health care customer: Review, synthesis and research agenda. Journal of Service Management, 28(1), 2–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-01-2016-0018

- Moore, J. F. (1993). Predators and prey: A new ecology of competition. Harvard Business Review, 71(3), 75–86.

- Mortazavi, S., Eslami, M. H., Hajikhani, A., & Väätänen, J. (2020). Mapping inclusive innovation: A bibliometric study and literature review. Journal of Business Research, 122, 736–750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.030

- Mühlbacher, H., Bertschy, M., & Desbordes, M. (2021). Brand identity dynamics–reinforcement or destabilisation of a sport brand identity through the introduction of esports? Journal of Strategic Marketing, 30(4), 421–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2021.1959628

- Mühlbacher, H., Bertschy, M., & Desbordes, M. (2022). Brand identity dynamics–reinforcement or destabilisation of a sport brand identity through the introduction of esports?. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 30(4), 421–442.

- Nilsson, E., & Ballantyne, D. (2014). Reexamining the place of servicescape in marketing: A service-dominant logic perspective. The Journal of Services Marketing, 28(5), 374–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSM-01-2013-0004

- Ningning, W., Wenguang, C., & Vega-Muñoz, A. (2023). The effect of playing e-sports games on young people’s desire to engage in physical activity: Mediating effects of social presence perception and virtual sports experience. PLOS ONE, 18(7), e0288608. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288608

- Nuseibah, A., & Wolff, C. (2015, September 24–26). Business ecosystem analysis framework. 2015 IEEE 8th International Conference on Intelligent Data Acquisition and Advanced Computing Systems: Technology and Applications (IDAACS), Warsaw, Poland.

- Nyström, A.-G., McCauley, B., Macey, J., Scholz, T. M., Besombes, N., Cestino, J., Hiltscher, J., Orme, S., Rumble, R., & Törhönen, M. (2022). Current issues of sustainability in esports. International Journal of Esports, 3(3), 1–19.

- Oliver, J. J. (2018). Strategic transformations in the media. Journal of Media Business Studies, 15(4), 278–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2018.1546088

- Parshakov, P., Naidenova, I., & Barajas, A. (2020). Spillover effect in promotion: Evidence from video game publishers and eSports tournaments. Journal of Business Research, 118, 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.036

- Partin, W. C. (2020). Bit by (twitch) bit: “platform capture” and the evolution of digital platforms. Social Media+ Society, 6(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120933981

- Pizam, A., & Tasci, A. D. (2019). Experienscape: Expanding the concept of servicescape with a multi-stakeholder and multi-disciplinary approach (invited paper for ‘luminaries. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.010

- Pizzo, A. D., Kunkel, T., Jones, G. J., Baker, B. J., & Funk, D. C. (2022). The strategic advantage of mature-stage firms: Digitalization and the diversification of professional sport into esports. Journal of Business Research, 139, 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.09.057

- Pizzo, A. D., Su, Y., Scholz, T., Baker, B. J., Hamari, J., & Ndanga, L. (2022). Esports scholarship review: Synthesis, contributions, and future research. Journal of Sport Management, 36(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2021-0228

- Pu, H., Xiao, S., & Kota, R. W. (2022). Virtual games meet physical playground: Exploring and measuring motivations for live esports event attendance. Sport in Society, 25(10), 1886–1908. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2021.1890037

- Ratten, V. (2016). Sport innovation management: Towards a research agenda. The Innovation, 18(3), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2016.1244471

- Reitman, J. G., Anderson-Coto, M. J., Wu, M., Lee, J. S., & Steinkuehler, C. (2020). Esports research: A literature review. Games and Culture, 15(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019840892

- Roth, A., Kunz, R. E., & Kolo, C. (2023). The players’ perspective of value co-creation in esports service ecosystems. Journal of Media Business Studies, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2023.2225299

- Roy, S. K., Singh, G., Hope, M., Nguyen, B., & Harrigan, P. (2019). The rise of smart consumers: Role of smart servicescape and smart consumer experience co-creation. Journal of Marketing Management, 35(15–16), 1480–1513. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2019.1680569

- Ruiz, É., & Gandia, R. (2023). The key role of the event in combining business and community-based logics for managing an ecosystem: Empirical evidence from Lyon e-sport. European Management Journal, 41(4), 560–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2022.07.005

- Sax, M., & Ausloos, J. (2021). Getting under your skin (s): A legal-ethical exploration of Fortnite’s transformation into a content delivery platform and its manipulative potential. Interactive Entertainment Law Review, 4(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.4337/ielr.2021.0001

- Scholz, T. M. (2019). eSports is business. Springer.

- Scholz, T. M. (2020). Deciphering the world of eSports. International Journals on Media Management, 22(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2020.1757808

- Scholz, T. M., & Stein, V. (2017). Going beyond ambidexterity in the media industry: eSports as pioneer of ultradexterity. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS), 9(2), 47–62. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJGCMS.2017040104

- Seo, Y. (2013). Electronic sports: A new marketing landscape of the experience economy. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(13–14), 1542–1560. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2013.822906

- Seo, Y. (2016). Professionalized consumption and identity transformations in the field of eSports. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.07.039

- Seo, Y., Buchanan‐Oliver, M., & Fam, K. S. (2015). Advancing research on computer game consumption: A future research agenda. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 14(6), 353–356. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1557

- Sherrick, B., Smith, C., & Hou, J. (2024). Predicting the financial and viewership success of livestreamers. Journal of Media Business Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2024.2324226

- Sjöblom, M., Törhönen, M., Hamari, J., & Macey, J. (2017). Content structure is king: An empirical study on gratifications, game genres and content type on twitch. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.036

- Sjöblom, M., Törhönen, M., Hamari, J., & Macey, J. (2019). The ingredients of twitch streaming: Affordances of game streams. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.10.012

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Stein, V., & Scholz, T. M. (2016, May 5th - 6th). Sky is the limit- esports as entrepreneurial innovator for media management. International Congress on Interdisciplinarity in Social and Human Sciences, Faro, Portugal.

- Stern, A.[ @A_S12]. (2020, 12 May). @foxsports finished the Pro invitational series with 688,000 viewers for Saturday’s iRacing event from virtual North Wilkesboro. Retrieved 15 August. 2020 from https://twitter.com/a_s12/status/1260225797383749632

- Taylor, T. L. (2012). Raising the stakes: E-sports and the professionalization of computer gaming. MIT Press.

- Taylor, T. L., & Witkowski, E. (2010). This is how we play it: What a mega-LAN can teach us about games. Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, Monterey California. https://doi.org/10.1145/1822348

- Turkay, S., Formosa, J., Cuthbert, R., Adinolf, S., & Brown, R. A. (2021, May). Virtual reality esports-understanding competitive players’ perceptions of location based VR esports. Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Online Virtual Conference (pp. 8–13). Yokahama, Japan.

- Turley, L. W., & Milliman, R. E. (2000). Atmospheric effects on shopping behavior: A review of the experimental evidence. Journal of Business Research, 49(2), 193–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00010-7

- Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2017). Service-dominant logic 2025. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 34(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2016.11.001

- Viglia, G., Pera, R., & Bigné, E. (2018). The determinants of stakeholder engagement in digital platforms. Journal of Business Research, 89, 404–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.029

- Ward, M. R., & Harmon, A. D. (2019). ESport superstars. Journal of Sports Economics, 20(8), 987–1013. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002519859417

- Wohn, D. Y., & Freeman, G. (2020). Live streaming, playing, and money spending behaviors in eSports. Games and Culture, 15(1), 73–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412019859184

- Woratschek, H., Horbel, C., & Popp, B. (2014). The sport value framework–a new fundamental logic for analyses in sport management. European Sport Management Quarterly, 14(1), 6–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/16184742.2013.865776

- Wulf, T., Schneider, F. M., & Beckert, S. (2020). Watching players: An exploration of media enjoyment on twitch. Games and Culture, 15(3), 328–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412018788161

- Yue, L., Zheng, Y., & Ye, M. (2022). The impact of esports industry knowledge alliances on innovation performance: A mediation model based on knowledge sharing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 902473. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.902473

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

The process of analysis