ABSTRACT

Background: mHealth interventions have huge potential to reach large numbers of people in resource poor settings but have been criticised for lacking theory-driven design and rigorous evaluation. This paper shares the process we developed when developing an awareness raising and behaviour change focused mHealth intervention, through applying behavioural theory to in-depth qualitative research. It addresses an important gap in research regarding the use of theory and formative research to develop an mHealth intervention.

Objectives: To develop a theory-driven contextually relevant mHealth intervention aimed at preventing and managing diabetes among the general population in rural Bangladesh.

Methods: In-depth formative qualitative research (interviews and focus group discussions) were conducted in rural Faridpur. The data were analysed thematically and enablers and barriers to behaviour change related to lifestyle and the prevention of and management of diabetes were identified. In addition to the COM-B (Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour) model of behaviour change we selected the Transtheoretical Domains Framework (TDF) to be applied to the formative research in order to guide the development of the intervention.

Results: A six step-process was developed to outline the content of voice messages drawing on in-depth qualitative research and COM-B and TDF models. A table to inform voice messages was developed and acted as a guide to scriptwriters in the production of the messages.

Conclusions: In order to respond to the local needs of a community in Bangladesh, a process of formative research, drawing on behavioural theory helped in the development of awareness-raising and behaviour change mHealth messages through helping us to conceptualise and understand behaviour (for example by categorising behaviour into specific domains) and subsequently identify specific behavioural strategies to target the behaviour.

Responsible Editor Peter Byass, Umeå University, Sweden

Background

mHealth in low- and middle-income countries

The low cost and accessibility of mobile technology means mHealth (the use of mobile technology in health) in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) has huge potential to reach and improve the health of large numbers of people [Citation1–Citation3]. Due to the nature of technology, mHealth can bypass some of the barriers to health access and knowledge of low-literacy, geographical remoteness and lack of finances [Citation1].

Despite its potential, the evidence base for the effectiveness of mHealth interventions is limited. A review of 76 mHealth studies conducted in LMICs found while there is evidence of effectiveness of some interventions the overall quality and quantity of evidence is limited as many of the studies lack scale and rigorous evaluation [Citation1]. It is possible that poor initial design is a contributing factor to the general lack of scale for mHealth interventions, it may also be that they have not been designed to reach scale. Another review of 16 intervention studies on mHealth covering a range of issues in Africa, Asia and multi-countries found a lack of consistent improvement in behaviour and weak evaluation methods [Citation4]. It did highlight the importance of tailoring messages to an audience, using local language and understanding context to the interventions’ success. While many mHealth behaviour change interventions do not have a clear theoretical framework, a study by Ramachandran and colleagues provides a notable exception [Citation5]. The study was a randomised control trial in India testing the effectiveness of mobile messaging on preventing type two diabetes mellitus (T2DM) among men aged 35–55 with impaired glucose tolerance [Citation5]. The messages were based on the trans-theoretical model of behaviour change and the results indicated a 36% reduction in the incidence of diabetes among this high-risk group over two years [Citation5]. A review of web-based interventions for diabetes management found that having a theoretical base increased the likelihood of success [Citation6]. While there were only nine studies reviewed, most of which were based in high-income countries, their findings support the argument for theory-based approaches to behavioural mHealth interventions. A theoretical base to interventions means the intervention is underpinned and guided by a behavioural model and/or theory of change. Theory-based approaches may be more effective as theories help to explain behaviour and provide a rationale and focus for strategies.

As in other LMICs, despite poor infrastructure and weak health systems, mobile phone use and ownership in Bangladesh is widespread. An estimated 87% of rural households in Bangladesh owned at least one mobile phone in 2013 [Citation7]. While the opportunity for mHealth to promote health has been recognised by NGOs and researchers, a recent scoping study of eHealth and mHealth initiatives in Bangladesh found that they are sporadic and disjointed with a lack of evidence of their effectiveness [Citation8]. UCL and BADAS (the Diabetic Association of Bangladesh) set out to develop an mHealth intervention targeting awareness-raising and behaviour change related to diabetes prevention and control in rural Bangladesh. From the outset we aimed to address some of the gaps in research by ensuring the intervention is contextually relevant, grounded in theory and rigorously evaluated.

Diabetes in Bangladesh

There were an estimated 422 million adults living with diabetes in 2014 [Citation9], with LMICs accounting for almost 80% of cases [Citation10]. In Bangladesh diabetes affects an estimated 20% to 30% of the adult population either as intermediate hyperglycaemia or fully expressed diabetes mellitus [Citation8]. Ninety percent of diabetes cases are type two diabetes, which is the result of an inadequate production or sensitivity to insulin [Citation10]. Despite the high levels of diabetes, there are low levels of awareness about prevention, control and management of the condition [Citation7] and the resource-poor health system is ill-equipped to meet the demands of the increasing diabetes burden [Citation11].

As part of a three-arm cluster randomised trial [Citation12], we set out to develop, implement and evaluate an mHealth intervention aimed at preventing and managing diabetes among the adult population in rural Bangladesh. Our intervention targeted adults aged over 30, and focused on modifiable risk factors relating to diabetes as recommended by the World Health Organisation [Citation9]: care seeking, diet, physical activity, smoking and stress. The intervention consisted of people signing up (through a community recruitment drive) to receive one-minute voice messages twice a week for 14 months. From the outset we planned for the messages to be informative and entertaining, with professional scriptwriters involved in their production. In order to embed the messages in theory we planned to use the COM-B model of behaviour change [Citation13] to inform the development of the voice messages. In-depth qualitative research in rural Bangladesh ensured the messages were relevant and tailored towards the needs of the message recipients. The content of the messages was therefore informed by both contextual research and the application of behavioural theory, as detailed in the current paper. The intervention developed, informed by this study, was tested as part of the randomised control trial.

Methods

Development and application of a process for creating content for voice messages was achieved through: 1. Formative research in intervention areas; and 2. Applying theory to formative research findings.

1. Formative research

Aim

The aim of the formative research was to describe the context of the interventions and inform the development of culturally sensitive, tailored mHealth messages. This included exploration of local understandings of diabetes mellitus and barriers and enablers to having a healthy lifestyle related to specific behaviours (care-seeking, diet, physical activity, smoking and stress).

Setting

Data were collected from three upazillas (sub-districts) of Faridpur district in central Bangladesh. Faridpur is 200 km2 with a population of 1.7 million. Farming (jute and rice) is the main livelihood source in the district. The population is mostly Bengali and 90% Muslim [Citation14]. Data from our trial baseline survey in the area reveal approximately 10% of the population have diabetes and 20% have intermediate hyperglycaemia [Citation15].

Sampling and data collection

In total 16 semi-structured interviews and nine focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted. Six diabetics (3 women, 3 men), 5 non-diabetics (3 women, 2 men) and 5 health care workers were interviewed. Focus group discussions were conducted with five groups of diabetics (3 women, 2 men) and 4 groups of non-diabetics (2 women, 2 men). Research respondents were purposively sampled. They were recruited through key informants, snowball sampling and the assistance of local staff from the Diabetic Association. The respondents were aged between 30 and 60. The researcher sought to achieve a sample in which approximately half were perceived to be overweight, and there was a balance of better off and poorer socio-economic groups as estimated by observing house construction materials. This provided a range of views that aimed to be reflective of the rural population. Additionally, five local health workers were recruited in order to triangulate findings.

The interviews and FGDs were conducted in Bengali by a qualitative, bilingual researcher from BADAS (KAk). The interviews followed a topic guide, which is a list of topics and open-ended questions that serve as a guide for the interviewer. The topic guides were developed on the basis of the aims of the research, literature reviews and COM-B theory of behaviour change. The topic guides were developed in English, translated into Bangla and piloted with two non-diabetic participants in a suburb of Dhaka and one health worker and one person with diabetes at BIRDEM (Bangladesh Institute of Research and Rehabilitation in Diabetes Endocrine and Metabolic disorders) hospital in Dhaka. In addition to the interview schedule, mapping of the village and pile sorting (pictures described and categorised by research participants) were used in the interviews and FGDs in order to promote discussion.

Data analysis

The FGDs and interviews were recorded and transcribed from Bangla into English by professional translators. The translations were checked and parts back-translated to ensure accuracy. The data were analysed by two UCL researchers (JM and HMJ) and one from the BADAS (KAk). The software NVIVO 13 was used to assist, share and organise the analysis. Descriptive content analysis [Citation16] was used. Transcripts were analysed thematically. The process involved the researchers who analysed the data (JM, HMJ and KAk) familiarising themselves with the data, independently listing emerging themes (patterns in the data), comparing notes and reassessing the themes and data [Citation17]. The data and discussed themes were presented to the wider trial team (all the researchers involved in the randomised control trial) before finalising the coding structure and coding the transcripts in NVivo.

These data were subsequently organised and tabulated according to barriers (things that prevent) and enablers (things that assist) healthy behaviours that the intervention focuses on – general cross-cutting themes, care-seeking, diet, physical activity, smoking and stress. The result was a detailed list of barriers and enablers to a healthy lifestyle for each focus area, complete with quotes and context.

2. Applying theory to formative research to inform content

Selecting a theory

The COM-B model [Citation13] was referred to in the original project proposal as the framework we would use to develop and guide evaluation of the intervention. COM-B and its corresponding ‘behaviour change wheel’ (BCW) is an integrated framework based around a ‘behaviour system’ known as COM-B: Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour [Citation13], that explains behaviour and what needs to be addressed in order for behaviour to change. Capability is the psychological and physical capacity to engage behaviour. Motivation is defined as processes that energise and direct behaviour. Opportunity is factors outside the individual that make the behaviour possible. The model is broad as it was developed from 19 existing frameworks of behaviour change [Citation13]. The comprehensiveness of the model has been criticised, as by synthesising such a range of approaches it means that complex theories have been simplified and it is difficult to unpack exactly what is effective [Citation18,Citation19]. However, given the heterogeneity of the target of our intervention (variety of ages, gender, socio-economic status and health needs) it was difficult to assume a single process or model will be applicable for all as focused behaviour-change models tend to rely on specific processes working within limited domains [Citation19]. Furthermore, in practice intervention design frequently draws on several behaviour theories with overlapping theoretical constructs which makes it difficult to identify the exact process underlying behaviour change [Citation20]. So, while we did look at other more specific models, we decided the broadness of COM-B made it more suitable for our context.

Corresponding to COM-B, and further elaborating it, the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) was developed [Citation20] and thus also considered for application in our project. TDF is an integrative framework of behaviour change theory that simplifies and integrates existing theories to make them more accessible [Citation20]. TDF was developed through consensus by a range of experts, and later refined and validated by specialists [Citation20,Citation21]. TDF covers 14 domains of theoretical constructs that are a useful way of understanding and classifying behaviour. Examples of the domains include knowledge, skills, social influences, beliefs about capabilities, social influences, and environmental context and resources. Additionally, specific behaviour change techniques (BCTs) have been identified to correspond with individual domains [Citation20]. BCTs are the smallest constituents of behaviour change interventions; they are both replicable and observable [Citation22]. Examples of BCTs include shaping knowledge, modelling behaviour, information about health consequences and goal setting. A BCT taxonomy consisting of 93 BCTs has been created through a series of consensus exercises involving over 50 behaviour change experts [Citation20]. While the individual BCTs have been critiqued as being too simple and overly prescriptive [Citation18], the range allows choice and it would be difficult to apply overly complex BCTs to our mHealth intervention due to the constraints of short voice messages.

As our intervention covers a broad population we needed an understandable theory that comprehensively covers behaviour, thus we utilised both COM-B and TDF frameworks. COM-B had framed much of our formative research and was easier to communicate with the wider research team. COM-B was utilised in association with TDF in helping to identify TDF components that are likely to be important in changing behaviour [Citation20,Citation23]. The TDF model further elaborated COM-B and was a tool suited to the practical application of a range of behaviour change techniques in our study population, and thus was used as a tool to specifically guide the messages.

Applying TDF and COM-B to formative research to inform content

A paper by French and colleagues in 2012 outlined practical steps to developing an intervention by considering theory, evidence and practice [Citation24]. We drew on this approach when developing our intervention. summarises French et al’s model and identifies elements we drew on. This included the need to specify the behaviour change we are targeting, identifying barriers and enablers that need to be addressed and applying appropriate BCTs. However, we tailored our approach to specifically address TDF for an mHealth intervention, meaning we added, omitted and adapted steps. For example, step 2 of French et al’s model was broken down and adapted to align with TDF, we omitted step 4 from French et al’s model and we added our own steps 1 (context of the intervention) and 6 (a table of content bringing together the earlier steps).

Table 1. Steps for developing a theory informed implementation intervention: summary of French et al (2012) and mHealth intervention content development.

For our intervention development we considered the outcomes needed for the mHealth intervention to be a success and we were able to identify the barriers and enablers to this through the formative research. TDF theory enabled us to systematically classify the barriers and enablers and thereby identify BCTs to address them. We were able to break down this process into six-steps as detailed in the results.

Results

Through the analysis of the qualitative research and the TDF framework, a six-step process to developing a guide for the content of behaviour-orientated voice messages was produced. The end result was a comprehensive guide for the study team as well as scriptwriters and producers of the voice messages (who come from a non-medical, non-academic or behaviour change background). outlines the steps, with more detail provided under the corresponding sub-headings below.

Table 2. Steps to message content development.

Step 1: the context of the intervention

An overview and key findings from the formative research were shared with those involved in message development. A full description is beyond the scope of this paper, instead we provide a summary of some of the key findings on context that directly influenced mHealth message development, in , with specific emphasis on themes of religion, balance, family and societal pressure and gender roles. There were aspects on which the messages were able to build on, for example the responsibility to look after oneself as a religious duty. Importantly, understanding of context was crucial to defining the behaviour the intervention aimed to influence in step 2.

Table 3. Context from formative research.

Step 2: breakdown of outcomes

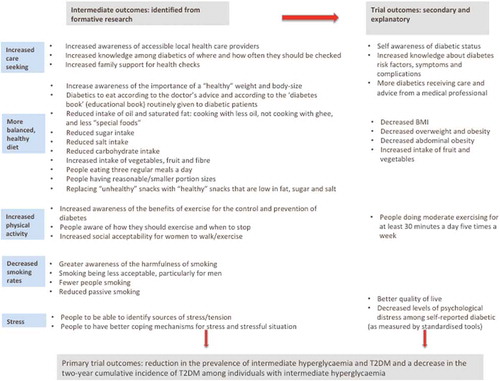

When planning an intervention it is important to identify changes the intervention should have (i.e. outcomes). The overall primary outcome of the trial was the reduction in the prevalence of intermediate hyperglycaemia and T2DM and a decrease in the two-year cumulative incidence of T2DM among individuals with intermediate hyperglycaemia [Citation12]. Secondary and explanatory trial outcomes include a range of outcomes related to risk factors, awareness and control of diabetes.

We developed a comprehensive list of intended intermediate outcomes for the intervention focused on behaviour and awareness, and related to each of our focus areas (). The intermediate outcomes are behaviours that need to change in order to achieve the trial outcomes, and are directly relevant to the context of the intervention and emerged from the formative research as well as the secondary trial outcomes (reported in full elsewhere [Citation12]). Having a clear understanding of the intended consequences of the intervention helped focus the messages of the intervention as well as identify the barriers and enablers to achieving them.

Steps 3: identifying and listing enablers and barriers to behaviour change

As explained in the methods section, the analysis of the formative research included a detailed breakdown of the barriers and enablers according to areas of focus. This list of barriers and enablers provided the basis of the message content, and enabled targeting of behaviour change specific to the context and grounded in theory. provides examples of barriers and enablers from each focus area.

Table 4. Examples of barriers and enablers to a healthy lifestyle (from formative research)a.

Steps 4 and 5: dividing the enablers and barriers according to TDF and COM-B and suggesting behaviour change techniques for the messages

For each enabler and barrier a COM-B characteristic and transtheoretical domain was identified. Identifying underlying domains enabled a better understanding of the behaviour and appropriate BCTs associated with the domains could be identified. Drawing on the BCT taxonomy compiled by the same group who developed TDF [Citation22], BCTs were selected for each enabler and barrier. BCTs that could be selected were limited due to the nature of voice messages. Identified BCTs included: modelling (demonstrating) behaviour, shaping knowledge, information about consequences, repetition and substitution, social support (encouraging), pros and cons and goal setting. provides examples of TDF and BCTs for a selection of barriers and enablers (the complete table of TDF and BCTs identified for each barrier and enabler are shown in ). The completed table enabled us to align messages with each barrier and enabler, and ensure that they were all addressed.

Table 5. Examples of barriers and enablers to a healthy lifestyle divided by COM-B and TDF domains, and associated Behaviour Change Techniques.

Table 6. Complete list of barriers and enablers to a healthy lifestyle divided by COM-B and TDF domains, and associated Behaviour Change Techniques.

Step 6: producing table of message content based on the intended outcomes, barriers and enablers and BCTs

In order to guide the scriptwriters as to the content of the voice messages we created a table with the guidelines for the content of individual messages. The details in the table include the TDF, BCT, barriers/enablers, the content, audience and suggested format. Each message was based around a specific enabler and/or barrier. The content addresses the barrier and/or enablers through one of the BCTs suggested.

An example of one of the messages is in . This message addresses the barrier that people are often expected to eat sweets and rich food during social occasions. The BCT is modelling behaviour: hence a drama with a scenario of someone going to a wedding and the techniques someone uses to eat smaller portions and less sweet food is described. The scenario was informed by the outcomes (smaller portions, less sugar, less oil etc.) and the context (the types of food and events extracted from the data). Doctors working with diabetic patients in Bangladesh checked all the messages to ensure they are in-line with current medical advice and standards. More examples from the table can be found in .

Table 7. Example of a message (relating to diet) from the table of content.

Table 8. Further examples of messages from the table of content for script writers.

Message production and delivery

The finalised table of contents was used to guide the intervention; specifically exact information needed to be shared as part of the intervention – and ensured all barriers and enablers emerging from the research were addressed. The table was shared with scriptwriters and a production company who were responsible for the format of the messages and making them both entertaining and understandable. Songs, dramas and straight information were all used with the language colloquial and tailored to the region. Project researchers and clinicians had final editorial control over the messages to ensure they were in-line with the context, and that they represented the content. A total of around 100 unique messages were produced and delivered to approximately 9000 individuals across 32 villages in Faridpur on a twice weekly basis between October 2016 and December 2017.

Discussion

In response to a lack of guidance in research regarding the development of a theory-driven mHealth intervention rooted in local context, we have developed and applied a six-step process to develop content for mHealth messages related to awareness raising and lifestyle changes for prevention and control of diabetes in rural Bangladesh. The process involved integrating in-depth qualitative contextual research with theory. The benefits of the steps outlined in the paper are that they are replicable and hence the model developed can be tested in other contexts. The exact methods used in the formative research do not need to be replicated, however contextual research identifying enablers and barriers to behaviour change is important. TDF and the corresponding BCTs can be applied to identify barriers and enablers to behaviour change. Hence the steps provide a guideline to intervention development, and due to the comprehensive nature of TDF and BCTs there is room for flexibility regarding the problems the interventions may address and the techniques that can be implemented to address them. The effectiveness of the messages is yet to be tested through the outcome of the trial and if applied in other contexts.

Many behaviour change interventions are targeted at individuals, and in those cases a clear target and pathway of change may be needed. For example, according to the transtheoretical change model, change is assumed to follow certain stages through which they are targeted [Citation5,Citation13]. While other models may account for wider societal and higher level influences (social ecological model for example) [Citation25], pathways, influences and beliefs vary widely not just according to individuals, but also groups. Behaviour and behaviour change is complex, having multiple targets is more complex: based on our experiences we believe it would be difficult for a classic, single theory to address these challenges. While the broadness of TDF, COM-B and BCTs have been criticised for not being specific enough, we found this to be a strength when applied to a population level intervention as it means a range of strategies and processes could be applied – increasing the likelihood of appealing to different segments of the population. For example we could classify problems specific to both genders and find appropriate BCTs to address them. Furthermore, within the range of the domains and BCTs, specific needs and approaches could be addressed according to specific barriers and enablers. We found TDF and the process we developed useful in enabling us to break down the specific needs of a population, identify what needs to change and what can be built upon and identify techniques in which this could be achieved.

An important aspect of the intervention was the packaging of the messages – with a production company being responsible for this. It was therefore important to convey the primary research effectively so that it could be applied appropriately. We did have a discussion about the scriptwriters conducting the qualitative research, in order for them to have a detailed understanding of the context. However, this would have meant them needing to be trained in qualitative research methods and be willing and able to spend time in the field. In practice members of the research team were more involved than planned in the editing and production of the messages – in order to ensure context was appropriately conveyed. Lessons learned from this collaboration were: collaborations and communication need to be carefully thought through and given plenty of time, as well as considering very early on in the process what collaborators of different background need and expect from each other and consider creative ways of achieving this (for example scriptwriters spending time in the field, and researchers learning how to write scripts).

Limitations

There were limitations to the study and the intervention. The broadness of the TDF and COM-B frameworks makes it difficult to unpick and assess exactly what aspects of the theory were effective. However, for the purpose of message development at a population level having a broad theoretical framework was useful (as explained in the discussion) and therefore for this study the benefits of the broadness of the models outweighed their potential weakness. Furthermore, as part of the trial we did conduct a process evaluation, which may illuminate what aspects of the intervention worked well and what did not. We were also limited by the nature of the mHealth intervention, as we were very limited in the behaviour change techniques that could be applied, and the intervention lacked two-way interaction.

Conclusion

A replicable process for developing the content of voice messages (and perhaps other interventions) for behavioural change, grounded in both theory and in-depth research, has been developed. Through identifying specific barriers and enablers to behaviour change from contextual research and categorising them according to the transtheoretical domain framework, BCTs can be applied to the barriers and enablers to promote behaviour change. While the process requires thorough research, clear outcomes and an application of TDF, the packaging of the intervention is also important. The six-step process developed is also significant as it is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to apply TDF and the COM-B model in a low-income setting. Thus it is particularly important that the local context is considered, and the behaviour change approaches contextualised appropriately. Ultimately the results of the trial and on-going evaluation will indicate the effectiveness of the intervention and its development, but the deep understanding of the intervention and the design decisions underpinning it will contribute enormously to the interpretation of the trial findings.

Author contributions

HMJ wrote the first draft of the manuscript, contributed to the design and analysis of the formative research data and led the development of the mHealth intervention. JM was involved in design and analysis of the formative research and contributed to the development of the mHealth intervention. KAk collected the research data, and contributed to the design and analysis of the formative research. AK, NA and SKS contributed to the development of the intervention. AKAK and KAz provided oversight and advice on the intervention development. TN and HBB were part of the trial team and read and commented on the manuscript. EF provided expertise, contributed to the intervention development and contributed significantly to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics and consent

The formative research was collected as part of a large cluster randomised control trial. Ethical approval was received for the research from the University College London Research Ethics Committee (4766/002) and the Ethical Review Committee of the Diabetic Association of Bangladesh (BADAS-ERC/EC/t5100246). All research respondents gave either informed written consent or consent by thumbprint to participate in the study.

Paper context

The evidence for the effectiveness of mHealth interventions in low-income countries is somewhat limited, and many lack a theoretical basis and context is not always considered. This paper addresses some of the gaps in research – it reports the process of applying qualitative research to behavioural theory to guide the development of an mHealth intervention in Bangladesh. It is hoped that the principles and process developed will be applied and tested in other contexts.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank m-World Bangladesh, and particularly Faisal Mahmud, for providing us technical expertise and their assistance in the final delivery of the mHealth messages.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hall CS, Fottrell E, Wilkinson S, et al. Assessing the impact of mHealth interventions in low- and middle-income countries – what has been shown to work? Glob Health Action. 2014;7:25606.

- Bergström A, Fottrell E, Hopkins H, et al. mHealth: can mobile technology improve health in low- and middle- income countries? UCL public policy briefing. 2015. [cited 2018 Nov 6] Available from: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/public-policy/sites/public-policy/files/migrated-files/mhealth_briefing.pdf

- Fottrell E. Commentary: the emperor’s new phone. BMJ. 2015;350:h2051.

- Gurman TA, Rubin ER, Ross AA. Effectiveness of mHealth behaviour change communication in developing countries: a systematic review of literature. J Health Commun. 2012;17:82–22.

- Ramachandran A, Snehalatha C, Ram J, et al. Effectiveness of mobile phone messaging in prevention of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle modification in men in India: a prospective, parallel-group, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2013;1:191–198.

- Cotterez AP, Durant N, Agne AA, et al. Internet interventions to support lifestyle modification for diabetes management: a systematic review of the evidence. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28:243–251.

- Nationl Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT). Bangladesh demographic and health survey 2014: key indicators. 2015 [cited 2018 Nov 6]. Available from: https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/bdhs_2014.pdf

- Ahmed T, Lucas H, Khan AS, et al. eHealth and mHealth initiatives in Bangladesh: a scoping study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:260–268.

- World Health Organisation. Global report on diabetes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organisation; 2016.

- International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes atlas. 8th ed. Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation; 2017.

- Bleich SN, Koehlmoos TLP, Rashid M, et al. Noncommunicable chronic disease in Bangladesh: overview of existing programs and priorities going forward. Health Policy. 2011;100:282–289.

- Fottrell E, Jennings H, Kuddus A, et al. The effect of community groups and mobile phone messages on the prevention and control of diabetes in rural Bangladesh: study protocol for a three-arm cluster randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2016;17:600.

- Michie S, van Stralen M, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Bangladesh population and housing census 2011. Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics; 2013.

- Fottrell E, Ahmed N, Shaha SK, et al. Age, sex, and wealth distribution of diabetes, hypertension and non-communicable disease risk factors among adults in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional epidemiological survey. BMJ Global Health. 2018. in press.

- Green JT, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. London: SAGE; 2005.

- Bernard HR. Research methods in anthropology: qualitative and quantitative approaches. Oxford: AltaMira Press; 2006.

- Ogden J. Celebrating variability and a call to limit systematisation: the example of the behaviour change technique taxonomy and the behaviour change wheel. Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10:245–250.

- Ogden J. Theories, timing and choice of audience: some key tensions in health psychology and a response to commentaries on Ogden (2016). Health Psychol Rev. 2016;10:274–276.

- Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37–53.

- Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, et al. on behalf of the ‘Psychological Theory’ Group. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14:26–33.

- Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an International consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46:81–95.

- Atkins S, Michie S. Conference on ‘Changing dietary behaviour: physiology through to practice’ Symposium 4: changing diet and behaviour – putting theory into practice. Designing interventions to change eating behaviours. Proc Nutr Soc. 2015;74:164–170.

- French SD, Green SE, O’Connor DA, et al. Developing theory-informed behaviour change interventions to implement evidence into practice: a systematic approach using the theoretical domains framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:38.

- Fishbain M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun Theory. 2003;13:164–183.