ABSTRACT

Spiritual Intelligence (SI) is an independent concept from spirituality, a unifying and integrative intelligence that can be trained and developed, allowing people to make use of spirituality to enhance daily interaction and problem solving in a sort of spirituality into action. To comprehensively map and analyze current knowledge on SI and understand its impact on mental health and human interactions, we conducted a scoping review following the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology, searching for ‘spiritual intelligence’ across PubMedCentral, Scopus, WebOfScience, and PsycInfo. Quantitative studies using validated SI instruments and reproducible methodologies, published up to 1 January 2022, were included. Selected references were independently assessed by two reviewers, with any disagreements resolved by a third reviewer. Data were extracted using a data extraction tool previously developed and piloted. From this search, a total of 69 manuscripts from 67 studies were included. Most studies (n = 48) were conducted in educational (n = 29) and healthcare (n = 19) settings, with the Spiritual Intelligence Self Report Inventory (SISRI-24) emerging as the predominant instrument for assessing SI (n = 39). Analysis revealed several notable correlations with SI: resilience (n = 7), general, mental, and spiritual health (n = 6), emotional intelligence (n = 5), and favorable social behaviors and communication strategies (n = 5). Conversely, negative correlations were observed with burnout and stress (n = 5), as well as depression and anxiety (n = 5). These findings prompt a discussion regarding the integration of the SI concept into a revised definition of health by the World Health Organization and underscore the significance of SI training as a preventative health measure.

Paper context

Main findings: This scoping review of Spiritual Intelligence found positive correlations with resilience, general, mental and spiritual health, emotional intelligence, and favourable social behaviours and communication strategies, and negative correlations with burnout, stress, depression, and anxiety.

Added knowledge: Spiritual Intelligence is an all-inclusive way to approach spirituality from a practical, daily problem-solving perspective that can be trained with several benefits for personal overall health, while also fostering substantial personal growth in social behaviors and skills.

Global health impact for policy and action: Spiritual Intelligence training is urgently needed and should be integrated into global educational programs from early childhood as a health promotion strategy aiming to foster a more resilient and compassionate society.

Responsible Editor Jennifer Stewart Williams

Background

Since the first steps of the multiple intelligences theory by Gardner [Citation1], the discussion on this matter has ever since been around the concept of independent, yet intertwined, mental skill sets that work in different dimensions of human existence. Initially, Gardner’s theory set eight main intelligence domains: visual-spatial; verbal-linguistic; musical-rhythmic; logical-mathematical; interpersonal; intrapersonal; naturalistic and bodily kinesthetic. This fruitful work later opened new horizons to the discussion of a new concept, entitled ‘Spiritual Intelligence’ (SI), in the late 90s, as the discussion on an intelligence domain concerning existential matters grew.

Acknowledging spirituality as the self-concept of one’s soul, a search for the sacred or transcendent and the personal vertical relationship one establishes with what one deems sacred, it is a separate concept from SI (though related). Defined as the personal skill to bring one’s own spirituality and the transcendental relationship with the sacred into daily problem solving, SI enhances one’s mental fortitude by expanding personal metaviews on daily interactions, broadening senses of purpose and meaning, and drawing spiritual capital from social participation, pushing the person forward towards their goals [Citation2]. Furthermore, SI is not to imply any religious belief or practice one chooses to integrate in their spiritual existence.

Closely linked to emotional intelligence (EI), SI facilitates the cognitive shift from the empathic ability to read and understand emotions to the compassionate ability to take action towards the ease of suffering without becoming overwhelmed by it [Citation3]. Almost as if EI reads, the emotions but SI further ‘reads the room’ or the ‘full picture’, thus the metaview.

The core SI dimensions [Citation2] are: (1) critical existential thinking, as the ability to answer deep existential questions in an open-minded and bias-free personal way, free from judgement and preconceptions allowing for self-evolution and self-actualization; (2) personal meaning production, as the ability to draw meaning from all good or bad, complex or simple, material or immaterial daily interactions and by making them meaningful integrating them in a positive and healthy way in one’s personal history and elevating one’s sense of well-being, meaning and purpose in life [Citation4,Citation5]; (3) transcendental awareness, as the ability to understand the world from a metaview perspective, aware both of the individual’s participation in the universe and the universe within the individual, making every decision and life event more than a self-directed event and putting it to a larger scale that makes one unique and relevant to the universe in one choices, thus responsible for them, but also a reflect of the universal interactions, thus not at fault for what overruns us; and (4) conscious state expansion, as the ability to enter, at one’s own will, into deeper states of spiritual attention and concentration (as in meditation) helping to capture from specific moments more than meets the eye and enabling a deeper connectedness to the sacred, nature or even other people, raising one’s fulfilment and sense of belonging.

Even though spirituality is an inherent part of the human being, the willingness to tap into it in a self-aware and self-constructive way is what makes SI. This ability to voluntarily explore the spiritual self and make it grow in individual interactions makes for a more fulfilling and resilient existence [Citation6].

Reinforcing the SI original concept, many quantitative studies throughout the past two decades have shown significant protective impact of SI concerning environmental, interpersonal and work-related stressors [Citation7–12].

At this time, and considering a preliminary search on PubMedCentral (PMC), no scoping reviews (published or ongoing) were found on this topic. Therefore, a Scoping Review (ScR) was conducted using the methodology proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for Scoping Reviews [Citation13]. The aim of this review was to map and analyze the current knowledge in this field by synthesizing existing quantitative studies, with the goal of establishing the known ramifications of SI and better understanding its impact on mental health and human interactions.

Review questions

This ScR aims to answer the general problematic:

What is known from the literature about the influence of Spiritual Intelligence on human behavior and mental health?

More specifically, our review questions are:

In what settings and populations is SI being studied?

Which instruments for SI measurement are being used?

What sociodemographic factors relate to SI?

What positive correlations to SI have been reported?

What negative correlations to SI have been reported?

Eligibility criteria

Participants

This ScR included any studies, with no age or sociodemographic background restrictions for the included samples or settings.

Concept

The included studies concern or directly address SI, as defined by King [Citation2]. Studies merely focusing on the general concept of spirituality were excluded.

Context

We considered studies on a vast spectrum of settings and people, undertaken in multiple areas of knowledge, including but not limited to healthcare and psychology.

Types of studies

This ScR considered for inclusion any quantitative studies that use properly validated SI evaluation instruments and reproducible methodology (aims, inclusion criteria, sampling and instrument validation and reliability).

Text, proceedings, conference or opinion papers, abstracts, reviews, mixed methods and qualitative studies were excluded. Studies published in predatory journals were considered for inclusion as long as they complied with the criteria and quality assessment.

Methods

This ScR was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology [Citation13] and reported according to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [Citation14].

Search strategy

Studies published in English, French, Spanish or Portuguese were included, since these are languages the authors are fluent in.

Studies published up until 1 January 2022, were included to document the evolutionary timeline of the SI concept. A search for ‘Spiritual Intelligence’ (search term) was conducted on PMC, Scopus, WebOfScience and PsycInfo databases and the search strategy was adapted for each included database.

Study/source of evidence selection

Following the search, all identified citations were uploaded to Mendeley® and duplicates removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (CTP, LG) for assessment against the inclusion criteria. The full text of selected citations was then assessed in detail by two reviewers (CTP, LG). Any disagreements between the reviewers at each stage of the selection process were discussed among the team or reviewed by a third reviewer (SP, RN). The results of the search and study inclusion process were reported according to the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram () [Citation14].

Figure 1. PRISMA-ScR flow diagram [Citation14].

![Figure 1. PRISMA-ScR flow diagram [Citation14].](/cms/asset/444df1f7-2ce7-4993-95c5-17bf63adff95/zgha_a_2362310_f0001_oc.jpg)

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the included papers by two independent reviewers (CTP, LG) using a data extraction tool developed by the reviewers. Prior to the study, the data extraction tool was pilot tested and trained by the reviewers with a total of 10 manuscripts with further cross-checking of the extracted data for consistency. The extracted data included various study details (authors, year, journal, country), as well as information on participants, study settings, aims, methodologies, SI instruments employed (including reliability and validation data), and key findings pertinent to the review objectives (including both positive and negative correlations to SI).

Results

Searches of electronic databases identified 470 hits, excluding duplicates (). After screening, 159 hits were excluded, which identified 202 eligible manuscripts. This resulted in 69 included manuscripts reporting on 67 studies.

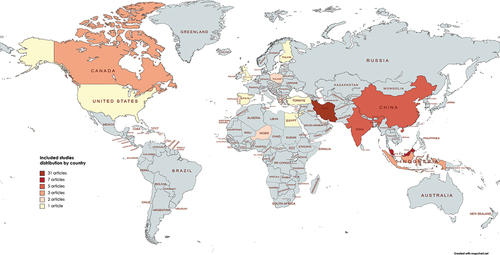

Among the 67 studies included for review, 32 were conducted in the Middle East (n = 34 manuscripts), 20 in Asia, nine in Europe, four in North America and two in Sub-Saharan Africa ().

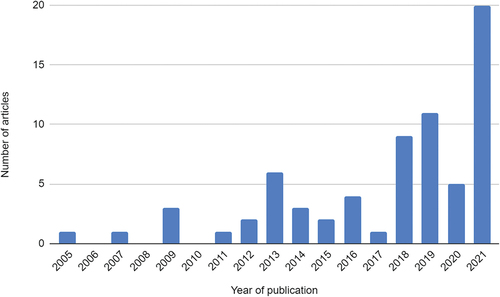

Until 2011, only five publications complied with our above-mentioned study quality assessment criteria; from 2011 until 2016, 14 studies; from 2016 to 2021, 30 studies and in 2021 alone a total of 20 relevant publications were found ().

Concerning the study design, most were correlational (n = 33) or descriptive (n = 18), with nine reporting on tool validations/psychometric assessment and only two quasi-experimental.

Settings and populations

Regarding the setting in which the studies took place, the educational system was the most frequent (n = 29), with the most frequently studied population being university students (n = 9456) and teachers (n = 1880). The second most frequent setting was the healthcare system (n = 19). Participants included 2948 nurses, 2100 patients and 1069 healthcare students. Among the patients, most were diagnosed with diabetes (n = 836), coronary diseases (n = 398) or were pregnant women (n = 379).

Studies involving the general population (n = 10) included 6577 individuals while those focusing on organizations (n = 5) included a total of 5150 various employees ().

Table 1. Summary of main findings in the included studies.

SI measuring instruments

The Spiritual Intelligence Self Report Inventory (SISRI-24) [Citation2] was the most used SI measuring instrument (n = 39), with validation data from 11,331 individuals representing a wide variety of socio-demographic backgrounds, and demonstrating high reliability (all 39 studies reported Cronbach’s α > 0,60; of which 76,9% with α > 0,80) (). The Integrated Spiritual Intelligence Scale (ISIS) [Citation15] was used in five studies representing a total validation population of 2142, with not so strong reliability data (reported Cronbach’s α ranging from 0,50 to 0,97).

Table 2. SISRI-24 worldwide validation data from selected studies.

Sociodemographics and SI

Reviewing the main findings from the included studies, the most frequently identified demographics related to SI were higher age (n = 7), religious affiliation (n = 6), and married status (n = 4). Other identified sociodemographic factors that favor SI included gender (with females reporting higher SI), higher education, childhood spirituality, a social system with fewer political constraints, ethnic attributes, geographic location (county living reported higher SI than country or towns) and community or shared living.

Positive correlations to SI

The most frequently identified attributes significantly positively correlated to SI were: resilience (n = 7); general, mental and spiritual health (n = 6); EI (n = 5); favorable social behaviors and positive communication strategies (n = 5).

Negative correlations to SI

The most frequently identified attributes significantly negatively correlated to SI were burnout and perceived stress (n = 5), as well as depression and anxiety (n = 5).

The full extent of attributes correlated to SI is reported in , along with the direction of said correlation (positive or negative).

Table 3. SI correlated attributes by major domains.

Globally addressing the main question of what is known about the influence of SI on human behavior and mental health, the gathered data suggests that SI is beneficial for mental health and for protecting against mental health risk factors, as well as being behaviorally well adaptive.

Discussion

Since the first mentions about SI, in 1997 by Zohar [Citation16], and throughout the concept’s journey into the Multiple Intelligences debate in the early 2000’s, the vast majority of the scholarly work on developing the concept and proving its criteria compliance with criteria as a separate type of intelligence has been conducted in North America [Citation2,Citation17–21].

After this initial theoretical approach and once the concept gained maturity to start being tested in its daily life impact, there was an interesting geographic shift of attention with most studies featuring quantitative research on SI being published from Asia and the Middle East.

The historical attention Eastern cultures dedicate to holistic practices, mindfulness and intuition, as along with the common fusion of religious practices and beliefs within cultural and political settings, may explain the readiness to investigate the SI concept in action [Citation22].

Although the initial interest on SI applicability was scarce, as more evidence was gathered, interest rose exponentially, particularly after the recent pandemic generated deep existential concerns and heightened awareness of the importance of spiritual and mental health worldwide.

Despite the majority of the studies being from Eastern culture settings, the most frequently used instrument to evaluate SI was the originally Canadian SISRI-24 [Citation2]. Aside from being easy to apply, this tool segregates from any religious connections, allowing it to be trustworthy in any cultural and/or religious setting and also accurate in evaluating SI in big culturally diverse samples.

It is well established in Gardner’s Multiple Intelligence Theory that one of the eight criteria for any type of intelligence should be its developmental history along the human lifespan, thus it is expected to grow from previous experiences and life challenges. Three different studies by Yang et al. [Citation23–25], which included 953 nurses from Taiwan and China, helped explore SI demographics and yielded important conclusions. These studies not only confirmed its increase with age (as previously reported by King and DeCicco when validating the SISRI-24 scale [Citation2]), but also revealed relevant associations with other demographic factors, such as religious affiliation and marital status.

Having some sort of religious belief or affiliation, even if not actively participating in religious rites and ceremonies, is also related to higher SI. Knowing that SI integrates dimensions of critical existential thinking and transcendental awareness, it is easily understandable that any sort of religious engagement may act as a trigger for such personal awareness, even if not essential for its development [Citation19,Citation23].

Higher SI was also related to married status and shared living situations and this may either come from a place of cause as of consequence, or both. When we further analyze the personal and social attributes related to SI, it is clear the implications and benefits for a shared existence scenario. For instance, higher SI relates to resilience, happiness, compassion, satisfaction in life, forgiveness, empathy, communication skills, commitment, less emotional dysregulation and less aggression. All the previous attributes can either be facilitators of a couple’s relationship and/or developed and enhanced through the marital partnership, increasing SI for married people [Citation24,Citation26].

The overall documented implications of SI increase the evidence supporting the necessity for a long-overdue revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) definition of health to adequately reflect the impact of this domain. If recurring arguments on the ambiguity of ‘spiritual’ and its relatability to ‘religion’ may be valid points against its inclusion on a revised definition of health, perhaps a different perspective is needed [Citation27].

From a SI perspective, one can argue that everyone should be allowed and encouraged to freely and creatively explore existential matters, become aware of their spirituality and engage in it as they see fit. Furthermore, individuals should be encouraged to find meaning in both simple daily experiences and major life events, and to adopt a conscious metaview of life. These practices foster the self-awareness necessary for the development of SI, which has a significant impact on health and healthcare.

In fact, intervention studies aiming to improve SI in adolescents and university students have consistently reported both its success in increasing SI scores [Citation28,Citation29] and in reducing stress, anxiety and depression [Citation29,Citation30], proving the effectiveness and benefit of these interventions from early ages towards better mental health and healthier coping strategies.

On a personal level, SI has consistently been associated with resilience. The ability to find meaning in daily simplicity and to consider everyday events in the context of a bigger picture makes individuals more likely to accept adversity as a challenge and seek constructive and comforting problem-solving strategies. Different authors studied the relationship between SI and resilience with consistent significant positive correlations [Citation31–33] and report prediction models with SI explaining variances from 10% [Citation32] to 18% [Citation34] on resiliency scores.

This capacity to find meaning in life in a broad sense but also in the smallest tasks, brings the also described higher sense of happiness (described SI-related variances of 19,8% [Citation35] up to 67% [Citation36]), higher life satisfaction [Citation37] and fewer depression symptoms (SI accounting for 55% negative variance, according to Parattukudi et al. [Citation38]).

The deeper self-knowledge and self-awareness cultivated through full attention to body, mind and soul/spiritual-self, enhance an individual’s self-management, self-efficacy and emotional self-regulation skills. These attributes not only contribute to stronger mental and spiritual health (as evidenced by reduced depression, anxiety, and death anxiety), but also foster a greater respect for the sacredness of the physical body and better health behaviors. Such behaviors have been shown to lead to better overall health outcomes, as demonstrated in the management of cardiovascular disease and diabetes management [Citation39–41].

As SI grows from the singularity of one’s individual spirituality, it then projects widely in the ‘give and take’ of social interactions, becoming a practical aspect of one’s cognition. These social contexts are where the personal benefits of self-awareness and self-compassion transform into a metaview of life and relationships.

When SI is high, forgiveness and empathy run easily [Citation42,Citation43] A mind free from pre-conceptions and judgment, with sharp ethical thinking promoted by a multi-angled and multi-level vision of the problems, is easier to communicate with and has the plasticity to adjust to the interpersonal needs in different social settings [Citation44,Citation45]. These favorable social behaviors that come from the understanding and acceptance of a world full of personal truths and doubts, lessens the social anxiety (as shown by Mosavinezhad et al., SI determines 42,9% of social anxiety variation [Citation11]) and aggressive behaviors (according to Ballochi et al., SI negative impact over aggression accounts for 29,5% of its variation [Citation46]).

In the specific domain of the workplace, it is of utmost importance for the quality of work life that individuals can derive meaning from their labor and recognize the broader impact of their work. Singla et al. demonstrated a 49.5% variance in quality of work life related to SI among college teachers [Citation47]. The spiritual capital one is able to draw from work enhances performance, with SI documented to impact performance ranging from 31.5% to 76.7% [Citation9,Citation48,Citation49]. Additionally, organizational citizenship behaviors [Citation50] and organizational commitment have reported a direct impact from SI of 10.8% according to Handayani et al. [Citation48], and an indirect impact on employees through managers’ SI of 18% according to Dargahi and Veysi [Citation51]. A recent scoping review on models of SI intervention programs suggests that 7–8 group sessions of 90 minutes, focusing mainly on transcendental awareness, critical existential thinking and conscious state expansion, through guided open discussions on ethical, existential and spiritual big issues and meditation or mindfulness exercises can benefit self-awareness, self-management and self-consciousness and also increase meaning in life and sense of holiness, promoting better relationships [Citation52].

A particular subset of employees that would greatly benefit from such SI intervention programs being implemented in their pre-graduate curricula are the healthcare professionals. In a time of great advances in artificial intelligence, people crave for meaningful connections to each other, specially at times of vulnerability and disease as in grave illness or palliative care settings when existential matters are daily present for both patients and healthcare professionals. In fact, a recent systematic review on the benefits of SI training for nurses [Citation53], consolidates evidence of significant increases in communication skills, spiritual care competence and job satisfaction, allied with reduced stress.

Nurses with higher SI also demonstrate a stronger professional self-concept, with 13.3% of the variance attributed to SI according to Hojat and Badiyepeymaiejahromi [Citation54]. They also exhibit greater psychological ownership over their work (12,0% SI-related variance determined by Kaur et al. [Citation12]), as they perceive their role within the universal flow of things.

This positive attitude around the workplace as well as the personal and social skills already explored that relate to higher SI, are consistently reported to prevent burnout and reduce perceived professional stress [Citation12].

Besides personal advantages for healthcare workers, SI was also positively related to better caring behavior [Citation12], spiritual care competency [Citation26,Citation55], ethical decision-making [Citation44] and empathy [Citation43] from nurses.

The above-mentioned scoping review on models of SI interventions [Citation52] was also effective in compiling relevant data on the benefits of SI training for healthcare professionals. These interventions not only succeed in increasing SI levels but also result in post-intervention reductions in perceived stress, higher job satisfaction, improved spiritual care competence, and enhanced communication skills.

Healthcare professionals are very exposed to profound suffering, adversity, and challenges, encompassing not only physical and mental needs but also ethical and spiritual dilemmas. Thus, patients and their families need compassionate care, tailored to their individual and unique needs. Given the compelling arguments in favor of the positive implications of SI, it seems only fitting that this relevant topic finds its way into all fields of healthcare education curricula [Citation56], benefiting both healthcare workers and patients.

Strengths and limitations

The major strengths of this ScR come from its broad search strategy and systematic methodology, which allowed for a thorough mapping of the existing evidence on SI. The quality of the reported evidence was also guaranteed through double independent analysis and methodology check of all screened manuscripts by two independent reviewers. Last, but not least, we proceeded to a careful integration and interpretation of the results in the light of the current knowledge.

Although our search included different languages (English, French, Spanish, and Portuguese), the subsequent identification of significant contributions to the study of SI from Oriental and Arabic countries may have limitations, as it may have missed publications in these languages. Since no grey literature was included for analysis, there is a possibility that early evidence on SI or evidence from areas of knowledge that do not typically undergo peer review may have been overlooked.

Conclusion

Integrating basic SI stimulation interventions into global children’s educational programs, from early years to the higher education (specially in healthcare professions), may be the simplest, most efficient and cost-effective approach to ensure a stronger mental health foundation for our future generations. Additionally, it can promote healthy coping mechanisms, health-related behaviors, and foster the development of more compassionate and tolerant adults.

From the above-exposed evidence, it is clear that SI training is effective in increasing SI levels and brings along major benefits towards general health, mental and spiritual health.

Anticipated main challenges toward implementing SI stimulation interventions include the risk of them being overshadowed by religious perspectives. Hence, we propose that general recommendations for SI training programs, encompassing both content and application, be developed through culturally diverse expert consensus. These interventions should always be supervised by a selected group of counselors who can ensure that the training protocols are being adequately applied. Pre-test/post-test evaluations should also be undertaken to provide further evidence of the adequacy of the protocol and to facilitate additional research and exploration of the impact of SI interventions.

Author contributions

The study conception and design were performed by Cristina Teixeira Pinto, Sara Pinto and Rui Nunes. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Cristina Teixeira Pinto, Lúcia Guedes and Sara Pinto. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Cristina Teixeira Pinto and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics and consent

Due to the revision nature of the work, no formal ethics approval was required.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Gardner H. Frames of mind: the theory of multiple intelligences. (NY): Basic Books; 1983.

- King DB, Decicco TL. A viable model and self-report measure of spiritual intelligence. Int J Transpersonal Stud [Internet]. 2009;28:68–16. doi: 10.24972/ijts.2009.28.1.68

- King DB, Mara CA, De Cicco TL. Connecting the spiritual and emotional intelligences: Confirming an intelligence criterion and assessing the role of empathy. Int J Transpersonal Stud. 2012;31:11–20. doi: 10.24972/IJTS.2012.31.1.11

- Dezutter J, Casalin S, Wachholtz A, Luyckx K, Hekking J, Vandewiele W. Meaning in life: An important factor for the psychological well-being of chronically ill patients? Rehabil Psychol. 2013;58:334–341. doi: 10.1037/a0034393

- Giannone DA, Kaplin D. How does spiritual intelligence relate to mental health in a western sample? J Humanist Psychol. 2020;60:400–417. doi: 10.1177/0022167817741041

- O’Sullivan L, Lindsay N. The relationship between spiritual intelligence, resilience, and well-being in an Aotearoa New Zealand sample. J Spiritual Ment Health. 2022;25:277–297. doi: 10.1080/19349637.2022.2086840

- Pishghadam R, Yousofi N, Amini A, Tabatabayeeyan MS. Interacción de reactancia psicológica, agotamiento e inteligencia espiritual: Un caso de profesorado iraní de inglés como lengua extranjera. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English ed). 2021;27:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.psicoe.2021.06.002

- Alamanda DT, Ahmad I, Putra HD, Hashim NA. The role of spiritual intelligence in citizenship behaviours amongst Muslim staff in Malaysia. HTS Teologiese Studies/Theol Stud. 2021;77:1–5. doi: 10.4102/hts.v77i1.6586

- Rahmawaty A, Rokhman W, Bawono A, Irkhami N. Emotional intelligence, spiritual intelligence and employee performance: The mediating role of communication competence. Int J Business Soc. 2021;22:734–752. doi: 10.33736/ijbs.3754.2021

- Ajele WK, Oladejo TA, Akanni AA, Babalola OB. Spiritual intelligence, mindfulness, emotional dysregulation, depression relationship with mental well-being among persons with diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2021;20:1705–1714. doi: 10.1007/s40200-021-00927-8

- Mosavinezhad SM, Safara M, Kasir S, Khanbabaee M. Role of spiritual intelligence and personal beliefs in social anxiety among University Students. Health Spiritual Med Ethics. 2019;6:11–17. doi: 10.29252/jhsme.6.3.11

- Kaur D, Sambasivan M, Kumar N. Effect of spiritual intelligence, emotional intelligence, psychological ownership and burnout on caring behaviour of nurses: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2013;22:3192–3202. doi: 10.1111/jocn.12386

- Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, et al. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:2119–2126. doi: 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ BMJ Publish Group. 2021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

- Amram Y, Dryer DC, Dryer C. The integrated spiritual intelligence scale (ISIS): development and preliminary validation. In: 116th Annual Conference of the American Psychological Association; Boston; 2008.

- Zohar D. Rewiring the corporate brain: using the new science to rethink how we structure and lead organizations. Berrett-Koehler Publishers; 1997. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:150619081

- Emmons RA. Is spirituality an intelligence? motivation, cognition, and the psychology of ultimate concern. Int J Phytoremediation. 2000;10:3–26. doi: 10.1207/S15327582IJPR1001_2

- Mayer JD. Spiritual intelligence or spiritual consciousness? Int J Phytoremediation. 2000;10:47–56. doi: 10.1207/S15327582IJPR1001_5

- Wolman R. Thinking with your soul: spiritual intelligence and why it matters. Choice reviews online. (NY): Harmony Books; 2001.

- Noble KD. Riding the windhorse: spiritual intelligence and the growth of the self. Cresskill (NJ): US. Hampton Press; 2001.

- Vaughan F. What is spiritual intelligence? J Humanist Psychol. 2002;42:16–33. doi: 10.1177/0022167802422003

- Mark CW. Spiritual intelligence and the neuroplastic brain: a contextual interpretation of modern history. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse; 2010.

- Yang K-P. The spiritual intelligence of nurses in Taiwan. J Nursing Res. 2006;14:24–35. doi: 10.1097/01.JNR.0000387559.26694.0b

- Yang K, Mao X. A study of nurses’ spiritual intelligence: a cross-sectional questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.03.004

- Yang K, Wu X. Spiritual intelligence of nurses in two Chinese social systems: A cross-sectional comparison study. J Nursing Res. 2009;17:189–198. doi: 10.1097/JNR.0b013e3181b2556c

- Ahmadi M, Estebsari F, Poormansouri S, et al. Perceived professional competence in spiritual care and predictive role of spiritual intelligence in Iranian nursing students. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;57:103227. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103227

- Peng-Keller S, Winiger F, Rauch R. The spirit of global health: the world health organization and the “spiritual dimension” of health, 1946-2021. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2022.

- Maryam H, Habibah E, Krauss SE, et al. An intervention programme to improve spiritual intelligence among Iranian Adolescents in Malaysia. Pertanika J Soc Sci Human. 2012;20:103–116.

- Dami ZA, Setiawan I, Sudarmanto G, et al. Effectiveness of group counseling on depression, anxiety, stress and components of spiritual intelligence in student. Int J Sci Technol Res. 2019;8:236–243.

- Ebrahimi M, Jalilabadi Z, Ghareh KH, et al. Effectiveness of training of spiritual intelligence components on depression, anxiety, and stress of adolescents. J Med Life. 2015;8:87–92. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:12977835

- Hatami A, Badrani MR, Kamboo MS, et al. An investigation of the relationship of spiritual intelligence and resilience with attitude to fear of childbirth in pregnant women. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2019;8:24–28. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2019/6

- Khosravi M, Nikmanesh Z. Relationship of spiritual intelligence with resilience and perceived stress. Iran J Psychiatry Behav Sci [Internet]. 2014;8:52–56. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25798174%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4364477

- Ebrahimi Barmi B, Hosseini M, Abdi K, et al. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and resiliency of rehabilitation staff. J Pastoral Care Counsel. 2019;73:205–210. doi: 10.1177/1542305019877158

- Ebrahimi A, Keykhosrovani M, Dehghani M, et al. Investigating the relationship between resiliency, spiritual intelligence and mental health of a group of undergraduate students. Life Sci J. 2012;9:67–70. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:4839441

- Amirian M-E, Fazilat-Pour M. Simple and multivariate relationships between spiritual intelligence with general health and happiness. J Relig Health. 2016;55:1275–1288. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0004-y

- Laleh B, Askari P, Honarmand MM, et al. Spiritual intelligence and happiness for adolescents in high school. Life Sci J. 2012;9:2296–2299. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:195295851

- Jafari A, Hesampour F. Predicting life satisfaction based on spiritual intelligence and psychological capital in older people. Iran J Ageing. 2017;12:90–103. doi: 10.21859/sija-120190

- Parattukudi A, Maxwell H, Dubois S. Women’s spiritual intelligence is associated with fewer depression symptoms: exploratory results from a Canadian sample. J Relig Health [Internet]. 2021;61:433–442. doi: 10.1007/s10943-021-01412-5

- Rahmanian M, Hojat M, Jahromi M, et al. The relationship between spiritual intelligence with self-efficacy in adolescents suffering type 1 diabetes. J Educ Health Promot. 2018;7:100. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_21_18

- Rahmanian M, Hojat M, Fatemi NS, et al. The predictive role of spiritual intelligence in selfmanagement in adolescents with type 1 diabetes. J Educ Health Promot. 2018;7:100–105. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_182_17

- Khayyam Nekouei Z, Yousefy A, Neshat Doost HT, et al. Structural model of psychological risk and protective factors affecting on quality of life in patients with coronary heart disease: A psychocardiology model. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:90–98. Available from: http://jrms.mui.ac.ir/index.php/jrms/article/view/9846/4094

- Mróz J, Kaleta K, Skrzypińska K. The role of spiritual intelligence and dispositional forgiveness in predicting episodic forgiveness. J Beliefs Value [Internet]. 2021;42:415–435. doi: 10.1080/13617672.2020.1851555

- Aliabadi PK, Zazoly AZ, Sohrab M, et al. The role of spiritual intelligence in predicting the empathy levels of nurses with COVID-19 patients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;35:658–663. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2021.10.007

- Arsang-Jang S, Khoramirad A, Pourmarzi D, et al. Relationship between spiritual intelligence and ethical decision making in Iranian nurses. J Humanist Psychol. 2020;60:330–341. doi: 10.1177/0022167817704319

- Geram K. The prediction of social adjustment based on emotional and spiritual intelligence. Int J Adv Biotechnol Res. 2016;7:19–25.

- Baloochi A, Abazari F, Mirzaee M. The relationship between spiritual intelligence and aggression in medical science students in the southeast of Iran. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2018;32. doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2017-0174

- Singla H, Mehta MD, Mehta P. Modeling spiritual intelligence on quality of work life of college teachers: a mediating role of psychological capital. Int J Quality Service Sci. 2021;13:341–358. doi: 10.1108/IJQSS-07-2020-0108

- Udin SH, Ahyar Yuniawan ER. Antecedents and consequences of affective commitment among Indonesian engineers working in automobile sector: An investigation of affecting variables for improvement in engineers role. Int J Civil Eng Technol. 2017;8:70–79.

- Rani AA, Abidin I, Rashid AH, et al. The impact of spiritual intelligence on work performance: case studies in government hospitals of east coast of Malaysia. Macrotheme Rev. 2013;2:46–59. http://macrotheme.com/yahoo_site_admin/assets/docs/7RaniMR23.40131338.pdf

- Anwar MA, Osman-Gani AM. The effects of spiritual intelligence and its dimensions on organizational citizenship behaviour. J Ind Eng Manage. 2015;8:1162–1178. doi: 10.3926/jiem.1451

- Dargahi H, Veysi F. The relationship between managers’ ideal intelligence as a hybrid model and employees’ organizational commitment: a case study in Tehran University of Medical Sciences. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2021;14. doi: 10.18502/jmehm.v14i8.6752

- Pinto CT, Veiga F, Guedes L, et al. Models of spiritual intelligence interventions: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;73:103829. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2023.103829

- Sharifnia AM, Fernandez R, Green H, et al. The effectiveness of spiritual intelligence educational interventions for nurses and nursing students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Educ Pract Elsevier Ltd. 2022;63:103380. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103380

- Hojat M, Badiyepeymaiejahromi Z. Relationship between spiritual intelligence and professional self-concept among Iranian nurses. Invest Educ Enferm. 2021;39. doi: 10.17533/udea.iee.v39n3e12

- Riahi S, Goudarzi F, Hasanvand S, et al. Assessing the effect of spiritual intelligence training on spiritual care competency in critical care nurses. J Med Life. 2018;11:346–354. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0056

- Pinto CT, Pinto S. From spiritual intelligence to spiritual care: a transformative approach to holistic practice. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020; 47:102823. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102823 Elsevier Ltd; 2020.