ABSTRACT

Background

While ear, nose, and throat (ENT) diseases are a substantial threat to global health, comprehensive reviews of ENT services in Southern Africa remain scarce.

Objective

This scoping review provides a decade-long overview of ENT services in Southern Africa and identifies gaps in healthcare provision. From the current literature, we hope to provide evidence-based recommendations to mitigate the challenges faced by the resource-limited ENT service.

Data Sources

PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCOhost, Cochrane Library, Cochrane Library, and Scopus.

Review Methods

On several databases, we conducted a comprehensive literature search on both quantitative and qualitative studies on ENT services in Southern Africa, published between 1 January 2014 and 27 February 2024. The extracted data from the analyzed studies was summarized into themes.

Results

Four themes in the fourteen studies included in the final analysis described the existing ENT services in Southern Africa: 1. Workforce scarcity and knowledge inadequacies, 2. Deficiencies in ENT infrastructure, equipment, and medication, 3. Inadequate ENT disease screening, management, and rehabilitation and 4. A lack of telehealth technology.

Conclusion

The Southern African ENT health service faces many disease screening, treatment, and rehabilitation challenges, including critical shortages of workforce, equipment, and medication. These challenges, impeding patient access to ENT healthcare, could be effectively addressed by implementing deliberate policies to train a larger workforce, increase ENT funding for equipment and medication, promote telehealth, and reduce the patient cost of care.

Paper Context

Main findings: Ear, nose and throat (ENT) healthcare in Southern Africa faces critical shortages of workforce, equipment, and medication for disease screening, treatment and rehabilitation.

Added knowledge: In this review, we identify challenges in the resource-limited Southern African ENT healthcare provision and provide evidence-based recommendations to mitigate these challenges.

Global health impact for policy and action: Improving ENT service delivery in the resource-limited world requires deliberate policies that improve health worker training, expand financing and resource availability, incorporate new technology, and lower patient costs of care.

Responsible Editor Maria Nilsson

Background

Diseases affecting the ear, nose, and throat (ENT) are a global phenomenon. With more than 1.5 billion people living with hearing loss, above 20 million afflicted with chronic otitis media, up to 40% suffering from allergic rhinitis, and 350,000 succumbing to head and neck cancer annually [Citation1–4], ENT diseases have become an important public health concern. In resource-limited settings, where the impact of ENT diseases is greatest, ENT health care is characterized by severe shortages of human resources (ENT specialists, audiologists, and speech therapists), medication, and equipment for treatment [Citation5–8]. In addition, funding for ENT healthcare, hearing and communication rehabilitation services are universally inadequate [Citation9–11].

The impact of ENT diseases is substantial, with patients suffering diminished quality of life stemming from the resulting communication disabilities, mental ill-health, and missed career opportunities [Citation12,Citation13]. Furthermore, ENT diseases inflict considerable individual and health system financial strain, particularly in resource-limited countries [Citation12,Citation14].

Given the recent global push for countries to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, which aims to ‘ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’ [Citation15], addressing factors hindering the universal delivery of ENT healthcare has never been greater. Over the last decade, there has been a growing interest in improving ENT healthcare in Southern Africa, a region where the prevalence of extreme poverty exceeds 51% [Citation16–18]. A 2017 survey of ENT services in sub-Saharan Africa reported a regional ratio of 1.2 million people per ENT surgeon, 0.8 million people per audiologist, and 1.3 million people per speech therapist, with scarce hearing testing and surgery [Citation6]. The shortage of ENT healthcare workers (HCWs) is exacerbated by a lack of training opportunities, as well as limited access to higher technology and expensive healthcare resources [Citation5,Citation6,Citation19]. Lukama et al. highlighted similar challenges in Zambia, documenting the four audiology booths, two flexible rhinolaryngoscopes, and four operating microscopes for the entire country, and critically scarce basic medication and surgical procedures for ENT [Citation8,Citation9]. In Mozambique, Malawi, Zimbabwe, and Zambia, several initiatives have been undertaken to address the poor access to ENT health care, including accelerating the training of ENT professionals and establishing more audiology units across the country [Citation6,Citation18,Citation20].

While many ENT disease prevalence studies have been conducted in Southern Africa [Citation21–24], there is as yet no review of the ENT service provision [Citation25]. This scoping review aims to provide an overview of the otolaryngology services in Southern Africa over the past 10 years, categorize findings, and identify the gaps in healthcare provision. It further seeks to provide evidence-backed recommendations to mitigate the multifaceted challenges posed by ENT diseases in resource-limited settings.

Methods

For this review, we were guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s 2005 scoping review framework [Citation26] and followed the PRISMA 2020 updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews [Citation27]. No human subjects were used, and therefore this scoping review did not require an Ethics Board review.

Search strategy

We used the string ‘(ENT OR Otorhinolaryngology OR “ear, nose and throat” OR otolaryngology) AND (Southern Africa* OR Botswana* OR Lesotho* OR Eswatini* OR Swaziland* OR Namibia* OR South Africa* OR Angola* OR Malawi* OR Mozambique* OR Zambia* OR Zimbabwe* OR Comoros* OR Madagascar* OR Mauritius* OR “Democratic Republic of Congo*” or Seychelles* OR Tanzania*)’ to search the following databases for literature: PubMed, Web of Science, EBSCOhost, Cochrane Library, and Scopus. In our search, we considered all SADC countries, including Botswana, Eswatini (formerly Swaziland), Namibia, South Africa, Angola, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Comoros, Madagascar, Mauritius, Democratic Republic of Congo, Seychelles, and Tanzania [Citation28]. The dates initially searched were 1 January 2014, to 27 February 2024. On 16 May 2024, we updated our search to include literature published between 27 February 2024, and 16 May 2024. We retrieved all the literature, and a shared EndNote library (EndNote 21, Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA) was used for screening the data.

Study selection

As we sought to limit our review to primary quantitative and qualitative research documenting the existence of ENT services and published in English, we excluded case reports and series, commentaries and editorials, disease epidemiological studies, validation studies, and those that investigated non-healthcare worker perceptions and opinions. Further, we excluded pilot studies, those trying new or low-cost technology, those investigating scoring systems, and descriptions of surgeries. We considered all studies in ENT, audiology, and speech language therapy (SLT).

At each subsequent database search, duplicates were removed with the title and abstracts simultaneously screened by three researchers (LL, WK, and CK). The full texts were assessed by five researchers (LL, WK, CK, CM, and CA), and the final full texts for inclusion were agreed on by all. Disputes were resolved by the first author (LL) before LL and CK independently extracted the data. Of the five researchers, two (LL and WK) were specialists in ENT, one (CK) in public health and research methods, one (CM) in epidemiology and biostatistics, and the last one (CA) in genetics and clinical and professional practice.

Data extraction and analysis

The following data was captured onto a predesigned Microsoft Word sheet: author, year of publication, study design and methodology, setting, objectives, main findings, policy recommendations, and recommendations for future research. The data sheet was piloted on 5 (35.7%) of the included full texts, with modifications made to the sheet as necessary. All authors agreed on the data to be captured. The extracted data were verified by individuals who did not take part in the data extraction (WK, CA, and CM).

Results

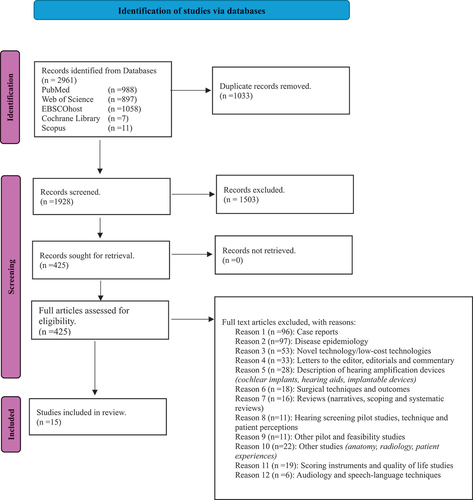

Our initial search retrieved 2961 articles. After removing duplicates, 1928 records underwent sequential title (559 included) and abstract screening, leaving 425 abstracts for full-text review. Applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we ultimately included 15 articles for thematic analysis, as shown in the PRISMA diagram in . Of these, eight were cross-sectional surveys, one was a retrospective cross-sectional review of ENT patients’ clinical records, three were observational studies, and three employed mixed methods to gather data. A summary of the included articles is presented in .

Table 1. Summary of studies used in the review.

Of the 15 included studies, three were from Zambia, six from South Africa, one from Malawi, three regional (sub-Saharan Africa and Africa), and two global. Four themes emerged from the 15 articles: 1. Scarcity of the ENT workforce and rehabilitation services, and knowledge inadequacies; 2. deficiencies in infrastructure, equipment, and medication; 3. inadequate ENT disease screening and management; and 4. telehealth and innovation.

Scarcity of the ENT workforce and rehabilitation services, and knowledge inadequacies

In the included studies, workforce shortages, inadequate ENT knowledge among clinicians, and disparities in clinician density across income groups contributing to challenges in accessing ENT services were prominent findings [Citation5–7,Citation9,Citation11,Citation17,Citation29,Citation30]. The ENT clinician density in Southern Africa was significantly lower (0.18 clinicians per 100,000 population) than the global average of 2.19 clinicians per 100,000 population [Citation7], particularly in Zambia and Malawi, where ENT specialists, audiologists, and speech and language therapists were critically short [Citation9,Citation11,Citation31]. These few clinicians are largely confined to urban centers, leaving rural areas underserved [Citation9,Citation31]. The scarcity of the ENT workforce is compounded by severe deficiencies in healthcare workers’ knowledge of basic ENT disease management, further compromising disease outcomes [Citation29]. Despite the majority of speech and language therapists (SLTs) having attained a minimum of a bachelor’s degree in SLT [Citation30], most other health workers involved in ENT health in countries like Zambia and Malawi were mid-level cadres without undergraduate degrees [Citation9,Citation11]. These mid-level cadres, including Clinical Officers (Diploma holders in Clinical Medical Sciences or equivalent) and Medical Licentiates (holders of an Advanced Diploma in General Medicine, a Specialty of Medicine, or a Bachelor of Science in Clinical Science), often manage patients at primary care and secondary facilities [Citation9]. However, these health workers have limited knowledge of ENT disease management due to inadequate training [Citation29].

Deficiencies in infrastructure, equipment, and medication

Several studies in Southern Africa described inadequate infrastructure and widespread unavailability of equipment, medication, and surgical procedures sufficient for ENT health care [Citation8–11,Citation32,Citation33]. Hearing amplification devices like hearing aids were scarce [Citation32]. They emphasized the urgent need for policy changes to improve ENT healthcare, including increased budget allocations and making essential medication more available. In addition to the scarce human resources, equipment, and funding for ENT healthcare, both hearing and communication rehabilitation services were largely unavailable in Southern Africa, notably in Zambia, Malawi, and South Africa [Citation9–11]. Public health facilities were more affected than private facilities [Citation33].

Inadequate screening, management, and rehabilitation of disease

ENT disease screening, management and rehabilitation services were largely unavailable [Citation5,Citation5,Citation6,Citation8–10,Citation17,Citation30,Citation32–36]. Ear and hearing conditions were severely underrepresented in national health policy in Southern Africa [Citation35], with several studies documenting the disparities in the practice of audiology, scarce testing facilities, and inadequate resources for hearing screening across different regions and healthcare sectors [Citation10,Citation32,Citation33]. Universal newborn hearing screening services, adult rehabilitation services, and follow-up care for hearing were limited in Southern Africa [Citation5,Citation9,Citation32]. Owing to the shortage of audiologists in the region, newborn hearing screening in many places is done by pediatricians, underscoring the pivotal role pediatricians play in the early identification and referral of hearing impairment [Citation36]. However, even in places where most neonatal hearing screening is conducted by audiologists, there remains a lack of standardized screening procedures [Citation33].

The scarcity of ENT treatment services was a universal phenomenon [Citation6,Citation8,Citation9,Citation30,Citation34]. Hearing rehabilitative surgery like tympanoplasty, middle ear prosthesis, bone-anchored hearing aids, and cochlear implants are largely unavailable [Citation5]. To make these services more available, fellowships in Africa have been effective in increasing the provision of specialized surgical services and establishing multidisciplinary teams, addressing the shortage of specialists in the region [Citation17].

Telehealth

While telehealth has enormous potential to improve the efficiency of hearing healthcare in the public sector, it is largely unavailable due to a lack of resources, equipment, and infrastructure [Citation37]. Despite the overwhelming enthusiasm by audiologists to use telehealth technology, its uptake was very low [Citation37].

Discussion

In this review, we described the ENT service in Southern Africa, uncovering the gaps in the service to inform policy. The review underscores critical deficiencies in the ENT workforce, medication and surgery for ENT healthcare, and screening and rehabilitation services, particularly in Zambia and Malawi. These deficiencies perpetuate the high morbidity and mortality among patients with ENT diseases and poor quality of life, retarding progress toward achieving the third SDG and promoting universal well-being for all [Citation12,Citation13,Citation15]. With most of the studies in our scoping review documenting case reports and series (22.9%) and the epidemiology of disease (22.4%), the dearth of literature on the availability and quality of ENT services in many Southern African countries calls for renewed effort into research that focuses on patient access to health care [Citation32].

Workforce limitations

The Southern African ENT clinician density of 0.18 per 100,000 population found in this scoping review is much lower than those in other low-resource regions, including Central America (0.68 per 100,000) and Southeast Asia (1.12 per 100,000) [Citation38]. With 70% of lower-middle, and 100% of low-income countries having less than one ENT clinician per 100,000 population [Citation38], this shortage of ENT specialists, audiologists, and SLTs noted is concerning, leading to disparities in access to care and compromised disease outcomes. While targeted training programs for mid-level ENT cadres and specialists have been implemented in South Africa [Citation17,Citation39], Malawi [Citation18], and Zambia [Citation9] over the last decade, little progress has been made in improving the number of available ENT healthcare workers [Citation5,Citation6]. To strengthen workforce capacity, a deliberate policy to increase training facilities should be strengthened, as noted in the Cape Town Head and Neck Fellowship [Citation17]. This policy should include increased funding for ENT training in existing schools, mobilization of specialised ENT workforce for teaching, and offering retention incentives for teaching faculty. Further, public-private partnerships for ENT training must be prioritized to assure sustainability of these training programs [Citation17]. Besides training specialists, we encourage health systems to provide shorter training programs for mid-level cadres as an urgent measure to strengthen the primary health care system and pathways to care. The mid-level cadres perform diagnostic and treatment functions that are traditionally thought of as the responsibility of doctors, usually in primary and secondary healthcare settings. They include clinical officers, health officers, medical assistants, medical licentiates, clinical associates, and others who are trained to diagnose and manage common medical, maternal, and child health (MCH) and surgical conditions [Citation40]. These mid-level cadres are impactful in the provision of accurate screening and diagnostic ENT services, promoting task-shifting and sharing for a more accessible ENT service [Citation18,Citation41].

Improving ENT healthcare worker competence through carefully planned, targeted short courses as continuous medical education in resource-limited settings is essential to empowering healthcare workers to deliver quality care within their scope of practice [Citation42,Citation43]. Coupled with telehealth, patients can achieve faster access to specialist care than the standard healthcare pathway [Citation44,Citation45]. The underutilization of telehealth technology found in this review presents a missed opportunity to improve accessibility to ENT services, especially hearing health. As a strategy to increase the adoption of telehealth, investments in infrastructure, equipment, and training are crucial [Citation37,Citation45]. Healthcare systems should prioritize the integration of telehealth platforms into existing healthcare systems, providing technical support and capacity-building initiatives.

Infrastructure, medication, and equipment deficiencies

The inadequate infrastructure and lack of essential equipment and medication for ENT care are significant barriers to service delivery [Citation8,Citation29]. Policy reforms aimed at increasing budget allocations for ENT healthcare, prioritizing the procurement of essential equipment and medication, and enhancing infrastructure development are critical to improving access to ENT healthcare. Additionally, leveraging public-private and international partnerships to improve resource mobilization and distribution could expedite the acquisition of critical resources, as has been done in Mozambique [Citation20], Zambia, Malawi, and Zimbabwe [Citation6,Citation9]. In addition to resource mobilization, partnerships should be used for the transfer of skills to local clinicians to achieve a sustainable service [Citation46,Citation47].

The scarcity of ENT disease screening, management, and rehabilitation services for ENT diseases calls for the prioritization of ENT initiatives in national health policy [Citation35]. Healthcare providers must advocate for the establishment of universal newborn hearing screening programs and expanding adult rehabilitation services to meet the United Nations’ third Sustainable Development Goal (good health and well-being for all ages) [Citation48].

Financial barriers to access to ENT services

Financial barriers significantly impede access to ENT services. With widespread poverty in Southern African countries, many people lack financial resources for healthcare, including diagnostic tests, medication, and procedures [Citation49]. The limited resources in healthcare facilities perpetuate the economic barriers to healthcare [Citation50], and despite healthcare ostensibly being free for low-cost services, patients still bear a substantial out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure on healthcare [Citation51]. While there is still a dearth of information about patient out-of-pocket expenses for ENT diseases in Southern Africa, a number of studies have looked into OOP costs for various medical and surgical conditions. The average patient out-of-pocket expenditure in rural Malawi is USD 2.72, while the median out-of-pocket expenditure on surgical disease in South Africa is over R100, which is reportedly high given the country’s current economic circumstances [Citation52,Citation53]. Therefore, reducing patient OOP expenditures must be an integral part of efforts to improve access to ENT health services. For example, the Zambian government introduced the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) in 2019 to serve as a pooled resource for affordable healthcare [Citation54], which significantly reduced patient OOP expenditure for those enrolled. Other African countries, including Rwanda, Botswana, Tanzania, and Nigeria, have utilized the concept of community health insurance to reduce patient OPP expenditure for better access to health care [Citation55]. However, the national coverage of these public health insurance schemes remains small [Citation55], and governments must scale up efforts to make these insurance schemes more available to citizens.

The results of this scoping review of Southern Africa are consistent with our personal experiences in Zambia and South Africa, with critical shortages of a trained workforce, medication, equipment, and rehabilitation services. Therefore, the proposed evidence-based strategies to address the constraints encountered by under-resourced ENT services are critical to improving ENT healthcare in Southern Africa.

Limitations of the study

We acknowledge our limitations in this scoping review, including our exclusion of literature published in languages other than English (1 study), the subjective nature of screening for inclusion of articles, and the strictness of our inclusion criteria, which may have excluded relevant literature for ENT healthcare. Further, our search terms may not have captured all the relevant literature, but we reduced this risk by performing trial literature searches in the considered databases to ensure relevant literature was captured. Our inclusion of five researchers in the screening process also reduced the impact of subjectivity in the literature review.

Despite our comprehensive search encompassing 15 countries – including three studies from Zambia, six from South Africa, one from Malawi, three regional (sub-Saharan Africa and Africa), and two global – only a few studies were retrieved for analysis. The paucity of studies on ENT services in the remaining Southern African countries may be due to the undocumented nature of these services, as suggested by the included studies. Consequently, our results may underestimate the extent of the challenges facing ENT services in these regions. A multi-national audit of ENT services using healthcare workers would overcome this limitation.

Conclusion

The scoping review highlights critical deficiencies in ENT services in Southern Africa, including the scarcity of a workforce, medication and equipment for healthcare, inadequate infrastructure, and gaps in screening and rehabilitation services. Deliberate policies to enhance health worker training, increase funding and resource availability, integrate telehealth technology into healthcare, and reduce the patient cost of care are imperative to improving ENT service delivery.

Author contributions

LL and CA conceived the study. LL, CA and CK developed the search strategy. LL, WK, and CK performed the initial database search, removed duplicates, and screened the titles and abstracts. LL, WK, CK, CM, and CA assessed the full texts and agreed on the final full texts for inclusion. LL resolved the disputes where applicable. LL and CK independently extracted and analyzed the data, which was verified by WK, CA, and CM. LL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read the manuscript, provided comments, and approved its final version for publication.

Ethics and consent

As a scoping review of available literature, ethics approval was not required.

Data availability statement

The data used to write this review is included in the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nur Husna SM, Tan HT, Md Shukri N, et al. Allergic Rhinitis: A clinical and pathophysiological overview. Front Med. 2022;9:874114. Epub 20220407. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.874114 PubMed PMID: 35463011; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9021509.

- Haile LM, Kamenov K, Briant PS, et al. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990–2019: findings from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet. 2021;397:996–12. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00516-x PubMed PMID: 33714390; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7960691.

- Alkire BC, Bergmark RW, Chambers K, et al. Head and neck cancer in South Asia: Macroeconomic consequences and the role of the head and neck surgeon. Head Neck. 2016;38:1242–1247. Epub 20160330. doi: 10.1002/hed.24430 PubMed PMID: 27028850.

- Khairkar M, Deshmukh P, Maity H, et al. Chronic suppurative otitis media: a comprehensive review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, microbiology, and complications. Cureus. 2023;15:e43729. Epub 20230818. doi: 10.7759/cureus.43729 PubMed PMID: 37727177; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10505739.

- Peer S, Vial I, Numanoglu A, et al. What is the availability of services for paediatric ENT surgery and paediatric surgery in Africa? Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2018;135:S79–s83. Epub 20180822. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2018.07.005 PubMed PMID: 30143398.

- Mulwafu W, Ensink R, Kuper H, et al. Survey of ENT services in sub-Saharan Africa: little progress between 2009 and 2015. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1289736. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1289736 PubMed PMID: 28485648; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5496047.

- Petrucci B, Okerosi S, Patterson RH, et al. The global otolaryngology-head and neck surgery workforce. JAMA otolaryngology– head & neck surgery. 2023;149:904–911. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2023.2339 PubMed PMID: 37651133.

- Lukama L, Kalinda C, Kuhn W, et al. Availability of ENT surgical procedures and medication in low-income nation hospitals: cause for concern in Zambia. Biomed Res Int. 2020;1980123. Epub 20200320. doi: 10.1155/2020/1980123 PubMed PMID: 32280679; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7128045.

- Lukama L, Kalinda C, Aldous C, et al. Africa’s challenged ENT services: highlighting challenges in Zambia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:443. Epub 20190702. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4267-y PubMed PMID: 31266482; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6604437.

- Moodley S. Paediatric diagnostic audiology testing in South Africa. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.12.015 PubMed PMID: WOS:000370888000001.

- Mulwafu W, Nyirenda TE, Fagan JJ, et al. Initiating and developing clinical services, training and research in a low resource setting: the Malawi ENT experience. Trop Doct. 2014;44:135–139. Epub 20140225. doi: 10.1177/0049475514524393 PubMed PMID: 24569097.

- Talat R, Speth MM, Gengler I, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis patients with and without polyps experience different symptom perception and quality of life burdens. Am J Rhinol?allergy. 2020;34:742–750. doi: 10.1177/1945892420927244

- Powell W, Jacobs JA, Noble W, et al. Rural adult perspectives on impact of hearing loss and barriers to care. J Community Health. 2019;44:668–674. doi: 10.1007/s10900-019-00656-3

- Enicker B, Khuzwayo ZB. Otogenic intracranial complications: a 10-year retrospective review in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Laryngol Otol. 2020;134:3–7. Epub 2020/01/22. doi: 10.1017/S0022215120000018

- Seidman G. Does SDG 3 have an adequate theory of change for improving health systems performance? J Glob Health. 2017;7:010302. doi: 10.7189/jogh.07.010302 PubMed PMID: 28567275; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5441444.

- Olaoye O, Ibukun CO, Razzak M, et al. Poverty prevalence and negative spillovers in Sub-Saharan Africa: a focus on extreme and multidimensional poverty in the region. IJOEM. 2023;18:2993–3021. doi: 10.1108/IJOEM-01-2021-0028

- Fagan JJ, Otiti J, Aswani J, et al. African head and neck fellowships: A model for a sustainable impact on head and neck cancer care in developing countries. Head Neck. 2019;41:1824–1829. Epub 20190116. doi: 10.1002/hed.25615 PubMed PMID: 30652381.

- Vandjelovic ND, Sugihara EM, Mulwafu W, et al. The creation of a sustainable otolaryngology department in Malawi. Ear Nose Throat J. 2020;99:501–502. Epub 20190606. doi: 10.1177/0145561319855366 PubMed PMID: 31170820.

- Swanepoel DW. Advancing Equitable Hearing Care: Innovations in Technology and Service Delivery. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 2023;75:201–207. doi: 10.1159/000530671 PubMed PMID: 37062271.

- Chulam TC, Bambo AWP, Machava PR, et al. A training and implementation model for head and neck oncology service delivery in Mozambique. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;30:201–206. doi: 10.1097/moo.0000000000000802 PubMed PMID: 35635116.

- Sibeko SR, Seedat RY. Adult-onset Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis at a South African Referral Hospital. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74:5188–5193. Epub 20220706. doi: 10.1007/s12070-022-03110-4 PubMed PMID: 36742562; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9895704.

- Abraham ZS, Dismas DS. Prevalence of cerumen impaction and associated factors among primary school pupils at an Urban District in Northern Tanzania. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;76:1724–1732. doi: 10.1007/s12070-023-04391-z PubMed PMID: WOS:001108200200008.

- Dapaah G, Hille J, Faquin WC, et al. The prevalence of human papillomavirus-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma at one of the largest tertiary care centers in sub-saharan Africa. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2022;146:1018–1023. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2021-0021-OA PubMed PMID: 34871360.

- Pedersen CK, Zimani P, Frendø M, et al. Chronic suppurative otitis media in Zimbabwean school children: a cross-sectional study. J Laryngol Otol. 2020:1–5. Epub 20201005. doi: 10.1017/s0022215120001814 PubMed PMID: 33016257.

- Belcher RH, Molter DW, Goudy SL, et al. An evidence-based practical approach to Pediatric Otolaryngology in the developing world. Otolaryngol Clin N Am. 2018;51:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2018.01.007

- Arksey H, O’malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ. 2021. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

- Southern African Development Community [Internet]. SADC. 2022. Available from: https://www.sadc.int/member-states

- Lukama L, Aldous C, Michelo C, et al. Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) disease diagnostic error in low-resource health care: Observations from a hospital-based cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE. 2023;18:e0281686. Epub 20230209. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281686 PubMed PMID: 36758061; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9910637.

- Wylie K, McAllister L, Davidson B, et al. Communication rehabilitation in sub-Saharan Africa: A workforce profile of speech and language therapists. Afr J Disabil. 2016;5:227. Epub 20160909. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v5i1.227 PubMed PMID: 28730052; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5433457.

- Pillay M, Tiwari R, Kathard H, et al. Sustainable workforce: South African Audiologists and Speech Therapists. Hum Resour Health. 2020;18:47. Epub 20200701. doi: 10.1186/s12960-020-00488-6 PubMed PMID: 32611357; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7329495.

- Bhamjee A, le Roux T, Schlemmer K, et al. Audiologists’ perceptions of hearing healthcare resources and services in South Africa’s public healthcare system. Health Serv Insights. 2022;15:11786329221135424. Epub 20221110. doi: 10.1177/11786329221135424 PubMed PMID: 36386271; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC9661562.

- Khoza-Shangase K, Kanji A, Ismail F. What are the current practices employed by audiologists in early hearing detection and intervention in the South African healthcare context? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;141:6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110587 PubMed PMID: WOS:000627379200028.

- Bright T, Mulwafu W, Thindwa R, et al. Reasons for low uptake of referrals to ear and hearing services for children in Malawi. PLOS ONE. 2017;12:e0188703. Epub 20171219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188703 PubMed PMID: 29261683; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5736203.

- Canick J, Petrucci B, Patterson R, et al. An analysis of the inclusion of ear and hearing care in national health policies, strategies and plans. Health Policy Plan. 2023;38:719–725. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czad026 PubMed PMID: 37130061; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10274565.

- Kanji A, Jamal A. Roles and reported practices of paediatricians in the early identification and monitoring of hearing impairment in high-risk newborns and infants. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2023;165:7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2023.111448 PubMed PMID: WOS:000925588200001.

- Bhamjee A, le Roux T, Swanepoel D, et al. Perceptions of telehealth services for hearing loss in South Africa’s public healthcare system. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph19137780 PubMed PMID: WOS:000824211700001.

- Petrucci B, Okerosi S, Patterson RH, et al. The global otolaryngology–head and neck surgery workforce. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2023;149:904–911. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2023.2339

- Peer S. Spotlight on Africa: paediatric ENT focus.

- Couper I, Ray S, Blaauw D, et al. Curriculum and training needs of mid-level health workers in Africa: a situational review from Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:553. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3362-9

- Bright T, Mulwafu W, Phiri M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of non-specialist versus specialist health workers in diagnosing hearing loss and ear disease in Malawi. Trop Med Int Health. 2019;24:817–828. Epub 20190509. doi: 10.1111/tmi.13238 PubMed PMID: 31001894.

- Tsiga-Ahmed FI, Ahmed A. Effectiveness of an ear and hearing care training program for frontline health workers: a before and after study. Ann Afr Med. 2020;19:20–25. doi: 10.4103/aam.aam_9_19

- James OD, Charles OD, Isla K, et al. Ongoing training of community health workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic scoping review of the literature. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e021467. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021467

- Alenezi EM, Veselinović T, Tao KF, et al. Ear Portal: An urban-based ear, nose, and throat, and audiology referral telehealth portal to improve access to specialist ear-health services for children. J Telemed Telecare. 2023:1357633x231158839. Epub 20230314. doi: 10.1177/1357633x231158839 PubMed PMID: 36916156.

- Moentmann MR, Miller RJ, Chung MT, et al. Using telemedicine to facilitate social distancing in otolaryngology: A systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2021;29:331–348. doi: 10.1177/1357633X20985391

- Nawagi F, Raman A. The importance of in-Country African instructors in international experiential training programs; a qualitative case study from the university of Minnesota. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04129-z

- Mulwafu W, Fagan JJ, Mukara KB, et al. ENT Outreach in Africa: rules of engagement. OTO Open. 2018;2:2473974x18777220. Epub 20180522. doi: 10.1177/2473974x18777220 PubMed PMID: 30480217; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6239148.

- Sustainable Development Goals [Internet]. UN. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/goals

- Alrasheed SH. A systemic review of barriers to accessing paediatric eye care services in African Countries. Afr Health Sci. 2021;21:1887–1897. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v21i4.47

- Quene TM, Smith L, Odland ML, et al. Prioritising and mapping barriers to achieve equitable surgical care in South Africa: A multi-disciplinary stakeholder workshop. Glob Health Action. 2022. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2022.2067395

- Okoroh JS, Riviello R. Challenges in healthcare financing for surgery in sub-Saharan Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2021;38. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2021.38.198.27115

- Wang Q, Fu AZ, Brenner S, et al. Out-of-pocket expenditure on chronic non-communicable diseases in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Rural Malawi. PLOS ONE. 2015;10:e0116897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116897

- Nakovics MI, Brenner S, Bongololo G, et al. Determinants of healthcare seeking and out-of-pocket expenditures in a “free” healthcare system: evidence from rural Malawi. Health Econ Rev. 2020;10:14. doi: 10.1186/s13561-020-00271-2

- Authority NHIM. National Health Insurance Scheme. Lusaka: National Health Insurance Management Authority; 2024.

- Chemouni B. The political path to universal health coverage: Power, ideas and community-based health insurance in Rwanda. World Dev. 2018;106:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.01.023