ABSTRACT

After the COVID-19 pandemic, human thoughts have changed in all fields worldwide. People started discovering different activities and realizing the essential role of urban spaces. Human needs and behavior changed through interaction with urban spaces. This article examines the importance of urban spaces in pandemics and how minor interventions can significantly impact urban spaces. We analyzed the city’s different zones in New Cairo City, Egypt. This research determined the application of urban acupuncture theory to the residence of a non-expert and listed the key focus areas for a practical acupuncture response. This study analyses the daily human uses of urban spaces and the role of pandemics that changed the functions of these urban spaces, observing and designing a survey evaluating urban spaces’ efficiency before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdown. The research results came out with the actual role of urban spaces as unfunctional, that concludes a fast and quick intervention after the reclaiming urban acupuncture principles that influential in transforming urban areas into liveable places. The results present a spatial visual analysis highlighting the challenges and benefits of urban acupuncture. The findings of our study can assist desicion-makers in evaluating samll nterventions that can create liveable places for all.

Introduction

Urban spaces and human interaction, since the COVID-19 pandemic appeared, became an essential direction as a regular reflection of the regulations and strategies that international organizations and local governments have stated [Citation1]. Since 2020, the Globe has suffered from the COVID-19 crisis due to the lockdown’s implications, such as social isolation, new labor regulations, loneliness, and financial dowels [Citation2]. Human safety and people’s health and requirements were highlighted during the COVID-19 shutdown, emphasizing the significance of seeking immediate assistance and restoring public places to livable conditions [Citation3]. An unexpected shift in lifestyle, such as being obliged to remain at home during the lockdown and altering their daily plans [Citation1,Citation4].

Urban acupuncture is a theory that has recently gained popularity among socially involved architects and urban planners [Citation5,Citation6], Traditional Chinese medicine is used in urban acupuncture to think about and treat the current urban fabric as a living body with flows and blockages, wounds, and suffering. We regard this theory as a practice theory that emerged from the concept of small interventions in urban areas [Citation7]. Urban acupuncture can make cities more livable and engaging [Citation8]. Its efforts can potentially have a long-term positive impact on the city’s general well-being.

The World Health Organization [Citation9] estimates that the COVID-19 lockdown exacerbated the spread of symptoms of depression and anxiety by 25%. According to this group, the shifting daily schedule and the difficulty in accessing any mental health support are the causes of this surge [Citation10]. In addition, the lack of nearby activities and social connections has been a significant concern for them. Because it functions, going to the neighboring urban spaces does not exist. People began exploring new hobbies that met their demands and looking for recent, unplanned locations.

This research explores the significance of urban spaces in pandemics and how minor interventions can significantly transform a place. The aim here is to analyze and investigate all fields to figure out the best solution, as we need fast and small-scale intervention to direct the world to think about pinpricks that change space functions from urban acupuncture theory. To meet this aim, a solid sampling approach is required for high-quality data gathering in qualitative research [Citation11].

This research contributes to highlighting the new functions and activities of different urban space categories and how people interact with their urban spaces as a step toward suitable urban spaces to improve human health. Additionally, our research may assist urban designers and planners in designing public areas for the future.

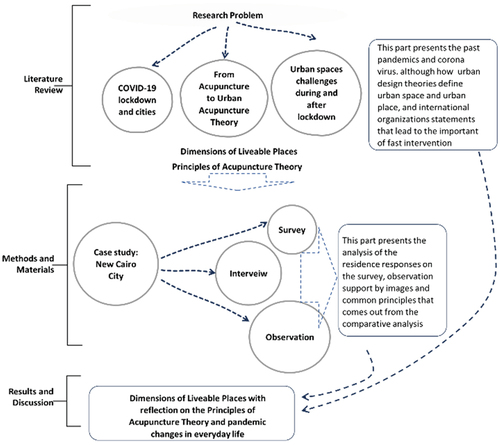

The structure of the research is divided into two parts (). Firstly, this part starts by reviewing the definitions of pandemic history, focusing on COVID-19, urban acupuncture and its principles, urban space, and placemaking. Then, transforming space into a place highlights the place-making characteristics. Furthermore, the question here comes to analyze how residents interact with urban space’s function, activities and uses to support their needs and the changes that appeared in surrounding metropolitan areas. Secondly, this part presents the results of observing new processes and activities of different urban space categories and people interacting with their urban spaces as a step toward suitable urban areas to improve human health. The case study part first introduces what a New Cairo City was and the sample size. After that, this research presented the different types of data collection. We discuss how the survey was designed and how the survey finds the residents. Also, the interview questions have been asked of the owners of small kiosks and coffee vehicles that have appeared since the lockdown. Then, the results of analyzing all questions show a clear image through the two survey sections. Finally, this part presents the limitations faced while observing and interviewing owners. The findings figured out the residents’ viewpoints to be taken into consideration.

Literature review

COVID-19 lockdown and cities

The COVID-19 pandemic isn’t the first time a crisis has hit the world. Oxford Language Dictionary describes a pandemic ‘as a noun: a widespread occurrence of an infectious disease over a whole country or the world at a particular time’ [Citation12] as an adjective, ‘(of a disease) prevalent over a whole country or the world’ [Citation12]. Initially, it came from the Greek word pandemic, the pan is all, and demos are people, so it became a pandemic in English. Over decades, the world has faced many pandemics that extirpated the human population. There was some pandemic before The Black Death, but it was the worst pandemic that hit the world presently.

The pandemic traveled from Asia to Europe (1334–1351), which caused the death of 200 million people. Smallpox in 1520 that leads to the end of 56 million people [Citation13,Citation14]. After that, the great plague continued from the 16th century to the 17th century, with the death of nearly four million. The Seven Cholera pandemic first appeared in India (1817–present). The Flu pandemic was in the modern industrial age, and new transport links made it easier for influenza viruses to spread [Citation15]. In just a few months, the third plague appeared in 1855, then the continuation of the flu series with the Russian flu, the disease spanned the Globe (1889–1890), and the Spanish Flu (1918–1919) [Citation9].

The spread and lethality were enhanced by the cramped conditions of soldiers and poor wartime nutrition that many people were experiencing during Asian Flu (1957–1958). The virus that caused the pandemic was a blend of Asian flu viruses. The H1N1 Swine Flu pandemic was caused by a new strain of H1N1 that originated in Mexico and spread to the rest of the world (2009–2010) [Citation16]. By the end of 2019 and the start of 2020, all the international news was talking about a virus that appeared in Wuhan, a city in China. Still, in March 2020, the World Health Organization announced a pandemic named COVID-19 spreading throughout the world until now [Citation9]

Behind every large-scale epidemic, urban construction and development are correspondingly promoted, and improving the public health system and enhancing public environmental awareness are encouraged [Citation10]. The United Nations and WHO discussed the intervention in all fields that can heal world cities [Citation17]. COVID-19 was added to an extensive list of transmissible viruses that have spread quickly in the twenty-first century, like Ebola in West Africa in 2014 and Tuberculosis in 2006, which provides a new challenge for cities to successfully plan for and transform into healthy cities [Citation18–20], As we discuss the term urban space, we should review the definition of urban design and its elements to understand the whole image.

From Acupuncture to Urban Acupuncture Theory

Acupuncture is a traditional Chinese medical practice that uses needles to stimulate specific points on the skin to treat various ailments. This method is considered simple and safe, as it targets nerve-rich areas on the skin to manipulate bodily processes, glands, tissues, and organs [Citation21,Citation22,Citation23]. In the 1970s, new terminologies such as ecology emerged, marking the start of urban intervention. This period saw a shift in public conversation toward addressing environmental issues, developmental studies, and sustainable solutions as responses to global crises such as oil shocks. Ecological challenges are more widely recognized and dominate research and discussions [Citation18].

Urban Acupuncture is a socio-environmental theory that combines contemporary, traditional Chinese acupuncture with urban design and interventions using a small scale to make a massive change in the larger urban context [Citation6]. Sites are selected by analyzing aggregate social, economic, and ecological factors. Lerner [Citation7] developed a dialogue between the community and designers. Urban acupuncture aims to relieve stress in the human body. Urban acupuncture reduces pressure in the built environment [Citation7]. The following three leading figures addressed the theory of urban acupuncture:

Manual De Sola-Morales [Citation24] was the one who flipped the coin, trying to solve urban problems through projects of strategic architecture. It is the urban matter that transmits to us, at its most sensitive points and neutral zones, the qualitative energy that accumulates collective character on urban spaces, charging them with complex significance and cultural references and making them semantic material, social constructions of intersubjective memory [Citation24].

Jaime Lerner [Citation7] encouraged practicians to step outside our doors and start looking for the dead spaces and less than lively places that could use a ‘needle’ of urban intervention. Lerner [Citation7] said, ‘Just as good medicine depends on the interaction between doctor and patient, successful urban planning involves triggering healthy responses within the city, probing here and there to stimulate improvements and positive chain reactions. Intervention is all about revitalisation, an indispensable way of making an organism function and change’ [Citation25].

Marco Casagrande [Citation26] said that urban acupuncture is a notion of urban ecology that integrates acupuncture into traditional Chinese medicine and urban architecture. Small-scale interventions are used in this process to change the wider urban environment. Sites are chosen after considering a variety of social, economic, and ecological concerns, and they create interaction between designers and the local population. Urban acupuncture reduces environmental and physical stress [Citation26]. He also developed the methods of urban acupuncture to create ecologically sustainable urban development toward the so-called ‘Third Generation City’. Casagrande mentioned that urban acupuncture produces small-scale but environmentally and socially catalytic action in the built human environment [Citation27].

Urban acupuncture can enhance human interaction and users’ satisfaction with urban spaces by transforming nonfunctional areas into habitable ones [Citation28]. Various papers have outlined the principles of this theory with both similarities and differences among them. The findings demonstrate the potential of this approach to improve urban spaces [Citation29].

The Urban Acupuncture Theory involves revitalizing urban areas through small-scale interventions. However, it is essential to consider that this method can be complex, and numerous factors could lead to potential issues. It is crucial to follow the eight principles and understand both the advantages and difficulties of the theory to achieve the most impactful results [Citation30].

Although this paper has studied urban acupuncture as an alternate technique to cope with open areas on a smaller scale, along with addressing the pertinent methods and ideas, it also discussed the concept of evolutionary history. Our data mining explored how urban acupuncture differs from other urban renewable strategies. It also concludes that Urban acupuncture boosts a city’s potential rather than solely depending on the urban planners’ vision as a small-scale space approach and a progressive concentrated metropolitan regeneration method [Citation31]. Urban acupuncture is an urban design approach that can revive cities, improve urban health, and stimulate urban societies, all while requiring less time and money [Citation27].

After reviewing urban acupuncture as a urban space policy in Amsterdam, this approach is less practical than more comprehensive designs. The city is better suited to managing more extensive programs that address multiple small actions simultaneously, which can benefit most residents. However, urban acupuncture shows potential as a concept, and applying it to evaluate small-scale improvements can improve the urban fabric and its users [Citation32].

illustrates that the essential principles are social involvement and small-scale intervention. Social involvement can help to find the sensitive spot faster. According to the daily routine, people’s problems usually come on a small scale, not significant.

Table 1. The comparative analysis between urban acupuncture principles source: the authors.

Urban spaces challenges during and after lockdown

As a conclusion of the above parts that gives the urban spaces the priority to be liveable to fit and support the needs and activities of the users during COVID-19 lockdown. That came from studying the past pandemics and the factors that affect the urban recovery and the reports of international organizations that insist on fast intervention and healthy spaces, this space could be the reason of infection reduction and breathing points during pandemics. Urban spaces have historically altered considerably depending on their function and needs through structure and shape [Citation28]. The first appearance of the space in history was the Agora, the central open space throughout the Greek era, which was also a hub for political and social life. Agora is a phrase that refers to ‘the meeting place or gathering space’ [Citation34]. It displays democratic features; it serves as a focus for political engagement. Then, it appeared in the Roman era as the Forum, another urban space historically parallel to the Agora. Forums evolved to mirror a geometric shape, primarily a rectangle. It displays civic and religious components, particular business activity, as stores and markets flank it, and sometimes recreational activities, such as theaters [Citation34].

Reclaiming urban space is the most prominent and evident spatial response at the community level to the COVID-19 pandemic, as temporary hospitals, warehouses, and other facilities were quickly erected in public locations to support emergency services, helping to increase community response capacity [Citation35]. Several temporary care facilities, such as temporary hospitals, isolation sites, and community health clinics, were built, considerably increasing the health sector’s capacity. Such incidents confirmed the importance of urban spaces in the emergency adaptation of urban function and spatial architecture to disasters [Citation9].

During COVID-19, urban spaces purposed to reduce public and economic health trade-offs. During the lockdown and everyday spatial planning. Reviving the streets as a shared space is essential and a colossal opportunity [Citation3].

Urban spaces serve various functions and have different dimensions available for public use [Citation23]. These spaces provide opportunities for grassroots gatherings, political activities for free associations in a democratic society, traditional and cultural festivals, ceremonies that foster private and social identities, and public and individual access to personal space [Citation36,Citation43]. From a descriptive standpoint, urban spaces are multipurpose and accessible locations different from family and individual territory. The dimensions of urban urban spaces include also sociability, activity and usage, access and relation and finally, image and comfort. These four dimensions underlayer with some characteristics [Citation43].

The COVID-19 pandemic experience may lead to further collaborations across sectors, from health care to public housing authorities, community development finance and community-based groups, philanthropy, and research that can impact policy. Systemic change does not occur in the absence of an enabling approach. We need to construct a paradigm in which urban planning, community development, architecture, green building, and public health are all encouraged to collaborate on better policies to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and future pandemics [Citation3].

Methods and materials

The case study

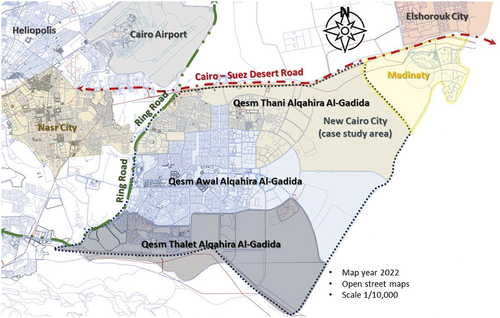

New Cairo City is one of the newly established eastern expansions to reduce the population density in the capital. It is one of the highest cities in Cairo in terms of sea level and the most significant area. What distinguishes New Cairo is its innovative urban division, which was implemented according to modern standards that achieve a balanced life considering the gradual increase in population density and traffic in the area. They issued planning permits and oversaw the communities by the Egyptian New Urban Communities Authority in 1979 [Citation37].

The Egyptian New Urban Communities Authority divided these new communities into four generations. The second generation included New Cairo City, Sheikh Zayed City, Badr, Obour, New Beni Suef City, New Minya, New Nubariya, and El-Shorouk from 1982 to 2000. It was established in 2000 by merging three ‘new’ settlements. The First, Third and Fifth settlements. The total original area was about 67,000 acres. After that, it has grown to 85,000 acres by 2016 [Citation38].

New Cairo City is located on the Eastern Desert to the East of the Cairo Ring Road and the modern extension of Nasr City. The ranges in elevation between 250 and 307 m on a plateau above sea level. The division of roads and streets in New Cairo City is an outlet that connects the different directions of the city. Through the ring road of Cairo on the east edge of New Cairo, it is possible to reach many vital areas quickly and easily in the capital, as well as the NA road that connects New Cairo City to Nasr City and its most significant streets. It is one of the fastest exits to the downtown area by passing through the Mokattam area [Citation39].

New Cairo City consists of three districts. The first district contains Ganoub el Academeya, East the Academy, 1st Settlement, El Yasmin, El Banafseg, North Investors, North Investors Extension, El Lotus and the service area (). The population is 135,834. The second district contains El Rehab 1 and 2, Madinaty, the total population is 90,668. The third district includes 5th Settlement, Elnarjes, South investors, Elgolf, and South Investors Extensions. The total population is 70,885 [Citation38].

Mobility in New Cairo City occurs through public transportation such as bus lines and buses. Trains or metro lines do not reach the city, but the cars of the city’s Board of Trustees link the different directions and areas within New Cairo to each other. At the same time, the Public Transport Authority in Egypt connects New Cairo City to parts of the New Adminstrative Capital City [Citation37,Citation44]. The beauty of New Cairo City has increased through the vast urban spaces throughout the city, making it a unique splendor that differs from the areas of the capital and other new cities. Urban spaces were among the most critical priorities of urban planning in New Cairo City, and the moderate weather of the region helped in that because of its relative height from the level of the capital [Citation37].

Data collection

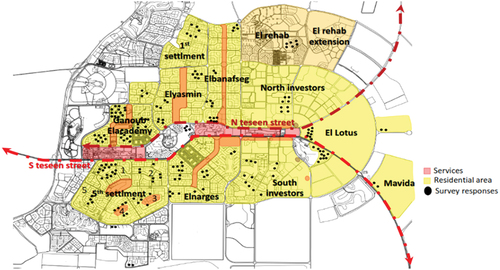

The data collection consisted of the survey, unstructured interview and site observation. First, quantitatively, New Cairo City contained three sections [Citation11,Citation45]. The first section collected the demographic and socioeconomic data that determined the residence locations and their pining into the map of the current case study of New Cairo City. The first question asked respondents to select the zone of their residence on the map.

A group of questions asked the respondents about urban spaces: destinations, activities, and lifestyles before and during the COVID-19 lockdown through the following questions:

What was the residence destination in New Cairo City before and during the COVID-19 lockdown?

What were the residents’ activities before and during the COVID-19 lockdown?

During the COVID-19 lockdown, did you visit any urban spaces in your vicinity?

Select one or more dimensions to be the reason for visiting urban spaces.

Select one or more sizes to be the reason for not visiting urban spaces.

Another group of questions asked respondents about their lifestyle and how residents cope with the places during the COVID-19 lockdown from their perspective, either positive or negative impacts.

Could the COVID-19 lockdown have been the reason behind the change in the city’s image?

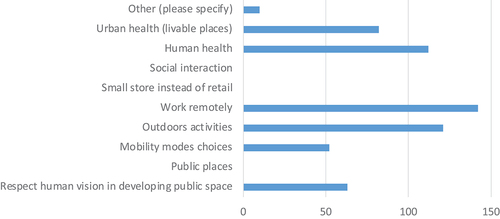

Select the factors in the city that can be changed post-COVID-19 lockdown.

The survey questions were sent through social media, printed copies to relatives, and e-mails, according to the electronic gate of New Cairo City that provides a graph that states the population of men and women in new cities in Egypt the total population of New Cairo City equal to 297,387 people, by putting the whole population to the sample size calculator [Citation11,Citation45]. It was calculated to have 384 responses; the number of responses was 296, but we neglected 50 reactions because they were outside the studied area.

The accompanying materials contained a list of these survey questions. This survey was administered to a random sample of area residents of various genders and ages. This questionnaire evaluates how people were affected during the COVID-19 lockdown and their interaction in urban spaces. Also, the causes are that they let humans look for other spots and turn them into gathering places with some activities in New Cairo City.

The unstructured interview was planned to investigate responses from small kiosk and coffee truck owners. Its purpose was to explore the connections within the community and context. The discussion includes queries for both business owners and employees. These questions included:

How were you holding up? How were you adjusting to life post-COVID-19?

You told me this was a spot for friends’ gatherings and a business location, so why did you choose this area?

How did COVID-19 affect your career?

How did you adapt to work during COVID-19 lockdown?

What have you learned during the lockdown period?

How did you cope with stress during the lockdown period?

What did you think about the changes during the lockdown period that continued till now?

Between 2020 and 2023, we conducted an on-site observation. This study showed remote observations from April 2020, working from 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. for two months. Later, the researchers of the present work involved in the study decided to observe people on the streets at 6:00 p.m. This research used photographic documentation to support the sample responses, tracked users’ behavior, and self-counted. However, in March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus a pandemic, leading to complete lockdowns in all countries. As a result, companies, malls, sports clubs, cafes, restaurants, universities, and schools were indefinitely closed, and people were not allowed to leave their homes for safety reasons.

Results and discussion

The literature review came with the essential points that helped design our survey, highlighting the importance of urban spaces, the great need for fast and low-cost intervention, and the reason for choosing urban acupuncture theory. This research presented the result of the designed survey from New Cairo City to highlight the sensitive spots and observe how residents’ self-acupuncture satisfies their needs. The results indicated that urban spaces should always be considered in urban planning. The results also confirmed that the concept of a ‘liveable place’ needed to be widened to encompass new variables.

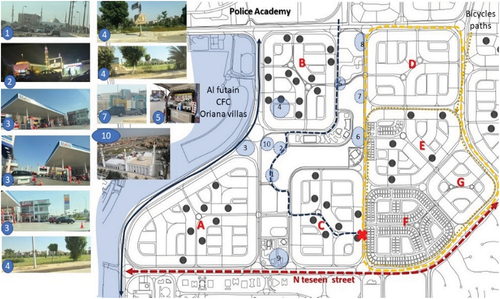

The initial section of the survey gathered demographic and socioeconomic information, including the names of residential areas and their location on a map. This section consisted of two questions and received 296 responses. illustrates the locations of the respondents’ residences, was included. The second question asked participants to identify their site on a map of New Cairo City, with 183 individuals providing responses and 113 skipping the question.

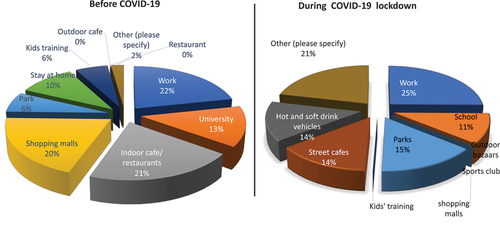

The second section measured the responses regarding how the lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic affected the society’s spirit. The results also show that 50% of the answers went for agree and agreed, and the other 50 were disagree, disagree, and moderate. The total agreement came from 224 provided a repose of ‘yes’ and 52 for ‘no’ to the answer of ‘Did COVID-19 change the lifestyle?’. Before COVID-19, people’s goals were going to work, university, indoor cafes, and shopping malls, but a small percentage went to parks and restaurants and stayed home. The third section shows some changes in the destinations during the coronavirus lockdown. People still went to work with precautions, shopping malls, and the idea of open services like drinks vehicles, street café, outdoor bazaars, and parks started to appear but were not planned ().

Figure 4. The destinations before COVID-19 lockdown (left), the destinations during the COVID-19 lockdown (right).

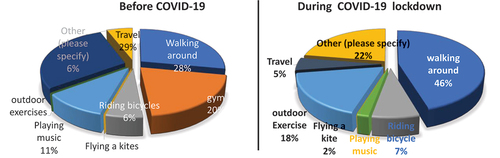

Their activities before the lockdown were traveling, going to the gym and walking around. New movements like walking around, riding bicycles, flying kites and outdoor exercises came, but these actions needed planning. The difference between these two charts was that during the lockdown period, zero per cent went to music places, the percentage of traveling decreased, and the rate of flying kites and outdoor exercise increased ().

Figure 5. Responses regarding the types of activities (left), before the COVID-19 lockdown, during the COVID-19 lockdown (right).

The results also showed that the percentage of people who did not visit urban spaces was low, and there was a lot of concurrence. These results came with 130 responses, which was equal to 25%. The urban spaces were not safe. Thirty responded with 6% mentioned that urban spaces were unfunctional, and the same percentage disliked the human contacts and participation in social activities. Urban spaces that were far away from hygienic facilities showed 28%. There were no social distancing with 22%. Additionally, there was no maintenance with 13%. Residents also replied on the dimensions of the reason for visiting urban spaces because of promoting human contact and social activities (19%). The safety, welcoming, and accommodating for all users figured out that 26%, supported the idea of social distance. The results also showed that 33% hygienic facilities with 17% and promoting community involvement with 5%.

After interviews with small kiosk and coffee truck owners, several findings were drawn. The initial questions revealed that some businesses experienced a decline in income due to the crisis and remote working. One coffee truck owner mentioned that some companies reduced their employees to cut costs. Another respondent noted that people were increasingly worried about losing their jobs amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. shows the factors that can be changed in our case study after the COVID-19 lockdown.

A kiosk owner shared that they had a strategy for selecting their vehicle and kiosk location but had to adapt during the COVID-19 lockdown. He monitored gathering points and found that customers often frequented the kiosk. To support the community and generate income, they shifted their services to meet the residents’ needs. Another kiosk owner expressed that adapting to the pandemic was challenging due to their responsibilities, commitments, and family. They had to adjust their daily routine and accept the changes. They acknowledged that they could do more but needed to consider various perspectives and remain positive.

A young man acknowledged the importance of helping those in need amidst the pressure of caring for oneself and others, which led him to start his own small business. Another coffee truck owner shared that it’s crucial for people to find a place of solace during these challenging times, where they can take a break, socialize, and maintain social distance due to the closure of recreational areas. A young lady working in a nearby cafe expressed her belief that any crisis also brings good opportunities if we stop being scared and think positively.

Interview results confirmed that lifestyle changes have updated the image of drinking coffee outdoors. This is achieved through food vehicles and coffee cars that cater to human needs, reducing the risk of disease transmission. The concept of walking around and finding food and drinks without needing transportation helped people to become more independent and reduces the need for interaction with others. This result presented an opportunity for people to increase their income post-crisis.

The observation comes with the following remarks. Some people did activities like walking, riding bicycles, and working in the unfunctional urban area nearby. Also, more people gathered while walking, having snakes, water, and chairs. They were sitting on the street, for example, in the Ganoub el Alacadmeya zone beside El Shorta Mosque, coffee vehicle beside Canadian International College (CIC), and the ice cream truck that found through several New Cairo City streets ().

Figure 7. The analysis of the Ganoub Alacadmeya zone with services and activities during the coronavirus lockdown, source: the authors.

This study focuses on urban spaces, which are easily accessible on foot and highly recommended for daily walking activities. According to the current results, urban areas provided opportunities for the local community to bond and interact socially while promoting safety and preventing disease transfer [Citation3,Citation31]. Our results align with previous studies confirming that urban spaces offer a sense of ownership, privacy, intimacy, and belonging [Citation1,Citation18,Citation23]. Additionally, recent research reported that changes in users’ experiences are accessible in the surrounding environment with no reference to people’s preferences [Citation30,Citation40,Citation41]. Urban spaces and users’ involvement in development projects can enhance the quality of the neighborhood and positively impact mental health [Citation9,Citation42].

There were some limitations in this study. Firstly, data collection was restricted to the time frame in which people were available, with observations only being made during working hours and on the street after 5:30 p.m. Secondly, while we received many responses to our online survey, 30% were incomplete. Despite our efforts to recruit participants using an online survey, reaching our desired sample size was challenging, and conducting face-to-face interviews was time-consuming and required computerized cleaning. We also encountered difficulties when interviewing kiosk and coffee car owners, as they were hesitant to respond due to their concerns about the data to share. These limitations made our study challenging to retrieved the results, and some responses had to be excluded as they were outside the scope of the study. The critical limiation was to undertake quantitative research and ethnographic investigations, which required a large sample size to achieve the desired results.

Conclusion

This article emphasizes the essential role of urban spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic and shows how small interventions can significantly impact residential areas. A survey conducted in New Cairo City examined sensitive spots and explored how residents’ self-treatments met their needs. Interviews and observations supported this information. Our results introduces a new concept of a ‘healthy urban environment’ inspired by the pandemic. The main findings present the term ‘urban acupuncture’ to describe the significance of any urban space as a vital source of life for people, depending on its livability.

For today’s city to be more liveable, the survey concluded that residences require an efficient location with shading elements to encourage increased use of public transportation. Additionally, there should be more walkable gardens and pedestrian bridges. The city should also provide digital, clean, intelligent, autonomous, intermodal mobility options and more walking and cycling paths alongside sidewalks and urban areas. Urban spaces should have all the necessary facilities, such as easy and free access and decreased security guidelines.

This article suggests that designing urban spaces considering human vision is crucial for creating a welcoming environment. Additionally, concerns about the risk of infection when using public transportation can influence people’s mobility mode. Urban areas must offer various activities and services, and the ability to work from home provides opportunities to explore nearby urban spaces. The demand for urban spaces and outdoor areas has the potential to alter the layout and structure of urban locations, which can have a significant impact on public health, social cohesion, and profitability.

This research provides evidence for the anticipated modifications to the urban acupuncture theory’s framework. The definition of public health has been expanded to encompass the connection between humans and nature, which can be implemented through social involvement and intervention in environmental, economic, and cultural domains.

Future research can expand our survey to a larger size in order to gain more insights into the various usages of urban spaces. A larger survey will provide more data points and better coverage across the various usages of urban spaces. This could allow for a more comprehensive analysis of the data, which can help inform the design of future urban spaces. Additionally, studying the usage of urban spaces after returning to normal could provide valuable insight into how people use urban spaces and how they should be designed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. COVID-19 and “the trinity of boredom” in public spaces: urban form, social distancing and digital transformation. Archnet-IJAR. 2022;16(1):172–183. doi: 10.1108/ARCH-05-2021-0133

- Maturana B, Salama AM, McInneny A. Architecture, urbanism and health in a post-pandemic virtual world. Archnet-IJAR. 2021;15(1):1–9. doi: 10.1108/ARCH-02-2021-0024

- United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). Cities and pandemics: Towards a more just, green and healthy future. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat); 2021.

- Elshater A, Abusaada H. Exploring the types of blogs cited in urban planning research. Plan Pract Res. 2023;38(1):62–80. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2022.2085352

- Al-Hinkawi WS, Al-Saadi SM (2020). Urban acupuncture, a strategy for development: case study of al-rusafa, Baghdad. IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (pp. 1–16). Institute of Physics Publishing. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/881/1/012002

- Hemingway JM, De Castro Mazarro A. 2022. Pinning down Urban Acupuncture: From a Planning Practice to a Sustainable Urban Transformation Model?. Planning Theory & Practice 23 (2):305–309. doi:10.1080/14649357.2022.2037383.

- Lerner J Urban Acupuncture. 2021, February 18. Washington, D.C: Island Press. The CASTAC Blog. Available from: https://blog.castac.org/2021/02/urban-acupuncture-design-theory-researching-new-development-practices-in-south-africa/

- He P, Xue J, Shen GQ, et al. The impact of neighborhood layout heterogeneity on carbon emissions in high-density urban areas: a case study of new development areas in Hong Kong. Energy Build. 2023;287:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.enbuild.2023.113002

- WHO. Strengthening preparedness for COVID-19 in cities and urban settings. New York: World Health Organizations; 2020.

- WHO. World Health Organization News. 2022, March 3. World health organization. [cited 2023 March]; Availablr from: https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide

- Survey System. Sample Size Calculator. 2023, June 12. creative research systems. Available from: https://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm#one

- Oxford University Press. Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. 3. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 1997.

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. Revealing distinguishing factors between space and place in urban design literature. J Urban Des. 2021b;26(3):319–340. doi: 10.1080/13574809.2020.1832887

- Attwa Y, Refaat M, Kandil Y. A study of the relationship between contemporary memorial landscape and user perception. Ain Shams Eng J. 2022;13(1):101527. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2021.06.013

- Sampath S, Khedr A, Qamar S, et al. Pandemics throughout the history. Cureus. 2021;12(9). doi: 10.7759/cureus.18136

- LePan N Visualizing The History Of Pandemics. 2020, March 14. Visual capitalist. Available from: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/history-of-pandemics-deadliest/

- UN-Habitat. UN-Habitat guidance on COVID-19 and public space. Nairobi: United Nations Human Settlements Programme; 2020b.

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. COVID-19’s challenges to urbanism: social distancing and the phenomenon of boredom in urban spaces. J Urbanism. 2020;15(2):258–260. doi: 10.1080/17549175.2020.1842484

- Duhl L, Sanchez A. Healthy cities. City planning process. Europe and North America: WHO REGIONAL OFFICE FOR EUROPE; 1999.

- Abusaada H, Elshater A 2020. Effects of urban atmospheres on changing attitudes of crowded public places: An action plan. Int. Journal of Com. WB 3 (2):109–159. doi:10.1007/s42413-019-00042-w.

- Sullivan D. Is Acupuncture the Miracle Remedy for Everything? Precision Pain Care & Rehabilitation. 2018 September 18. Healthline. Available from: https://www.healthline.com/health/acupuncture-how-does-it-work-scientifically

- Tangent Sustainable Lumber. Principles for Designing Great Public Spaces. 2021, April 18. Tangent Sustainable Lumber. Tangent Sustainable Lumber https://tangentmaterials.com/principles-for-designing-public-spaces/

- Carmona M 2019. Principles for public space design, planning to do better. Urban Des Int 24 (1):47–59. doi:10.1057/s41289-018-0070-3.

- Solà-Morales MD, Frampton K, Geuze A. A matter of things. Netherlands: NAI Publisher; 2008.

- Lerner J. Urban acupuncture. London: Island Press; 2014.

- Casagrande M. Paracity: Urban Acupuncture. In: Public Spaces Bratislava. Slovakia: Casagranda Laboratory; 2014. p. 32.

- Salman KA, Hussein SH (2021). Urban acupuncture as an approach for reviving. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Baghdad, Iraq (p. 10). IOP Publishing Ltd.

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. Improving visitor satisfaction in Egypt’s Heliopolis historical district. J Eng Appl Sci. 2021c;86(1):1–22. doi: 10.1186/s44147-021-00022-y

- Zelenková B Urban Acupuncture. 2016, March 18. The Ethnologist. Available from: https://ethnologist.info/section/urban-acupuncture/

- Hoogduyn R. Urban acupuncture revitalizing urban areas by small scale interventions. Stockholm: Digitala Vetenskapliga Arkivet; 2014.

- El-Bardisy N, Elshater A, Afifi S, Alfiky A. Predicting traffic sound levels in Cairo before, during, and after the COVID-19 lockdown using Predictor-LimA software. Ain Shams Engineering Journal. 2023;14(9):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2022.102088

- Tromp M. Urban acupuncture as a strategy for the. The Netherlands: Groningen; 2021.

- Nassar UA. Urban acupuncture in large cities: Filtering framework to select sensitive urban spots in Riyadh for effective urban renewal. J Contemp Urban Aff. 2021;5(1):1–18. 10.25034/ijcua.202

- Bugarič B. Transformation of public space, from modernism to consumerism. DOAJ. 2006;17(1–2):173–176. doi: 10.5379/urbani-izziv-en-2006-17-01-02-001

- UN-Habitat. UN-Habitat COVID-19 response plan. Nairobi: UN-Habitat Organization; 2020.

- Sanei M, Khodadad M, Ghadim FP. Effective instructions in design process of urban public spaces to promote sustainable development. World J Eng Technol. 2017;5(2):21. doi: 10.4236/wjet.2017.52019

- New Urban Communities Authority. About the authority. 2023a, May 12. New urban communities authority. Available from: http://www.newcities.gov.eg/about/default.aspx

- New Urban Communities Authority. New Cairo. 2023b, May 14. New urban communities authority. Available from: http://www.newcities.gov.eg/know_cities/New_Cairo/default.aspx

- Archive. Way back machine. 2014, December 31. Available from: https://web.archive.org/web/20161218175439/http://www.newcities.gov.eg/english/New_Communities/Cairo/default.aspxw

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. Cairenes’ storytelling: pedestrian scenarios as a normative factor when enforcing street changes in residential areas. Soc Sci. 2023;12(5):278. doi: 10.3390/socsci12050278

- Elshater A, Abusaada H. People’s absence from public places: Academic research in the post-covid-19 era. Urban Geogr. 2022;43(8):1268–1275. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2022.2072079

- Regional Public Health. Healthy open spaces. Wellington: Regional Public Health; 2010.

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. Effect of people on placemaking and affective atmospheres in city streets. Ain Shams Eng J. 2021a;12(3):3389–3403. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2021.04.019

- Abusaada H, Elshater A, Rashed R. Exploring the singularity of smart cities in the New Administrative Capital City, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng J. 2023;14 (9):102087. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2022.102087.

- Megahed G, Elshater A, MZ AS. Competencies urban planning students need to succeed in professional practices. ARCH. 2019-2020;14(2), 267–287. doi: 10.1108/ARCH-02-2019-0027