?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Social interaction is a crucial aspect of social sustainability, aiming to improve quality of life. However, the emergence of gated communities in Egypt has shifted priorities, prioritizing isolation over social interaction. This paper examines the impact of social interaction in gated communities in the West of the Greater Cairo Region from a social sustainability perspective. This study conducted a literature review on definitions and concepts of social sustainability and social interaction. We launched an online survey to measure social interaction in our case studies. We analyzed data retrieved from the survey to assess the correlation between social interaction and sustainability indicators. The results demonstrate that social interaction neutrally affects social sustainability indicators and users’ satisfaction. The survey findings indicate that users of gated communities rarely consider social interaction, which reflects their satisfaction with the isolation in the gated communities. As such, residents of gated communities should reconsider the shared spaces within these communities to improve social interaction and enhance social sustainability. This could lead to improved quality of life for people living in gated communities. Furthermore, improved social interaction within gated communities could also help to reduce social isolation and loneliness, which are associated with a range of physical and mental health issues.

Introduction

Sustainability has been debated extensively in environmental and economic dimensions but not in the social sphere [Citation1,Citation2]. Social sustainability has a crucial role in developing social life and liveable communities, providing people with high-quality life and well-planned neighborhoods to enhance the living experience and promote the well-being of the residents [Citation3–5]. For sustainable development to be successful, it is crucial for individuals and organizations to actively participate in and contribute to a community [Citation6]. Community participation enables people to collaborate, share knowledge and resources, and work toward common goals, leading to more effective and efficient sustainable development practices [Citation7,Citation8]. Furthermore, a sense of belonging and connection to a community can motivate individuals to act toward sustainability and inspire others to do the same [Citation9]. Therefore, fostering and strengthening communities is beneficial and essential for sustainable development [Citation10].

Research highlights the urge to study this concept to improve quality of life, especially social interaction and integration [Citation11]. Furthermore, there has been an evolving trend to satisfy people’s satisfaction by developing new residential typologies [Citation12–14]. In the past decade, the social interaction effects of the real estate market in response to the need for safety and security and enhanced quality of life. This situation forced the shift from conventional mixed housing to single detached units and gated communities [Citation15,Citation16].

Gated communities are becoming more common in Egypt, particularly upper-middle and high-income areas. At the same time, there are no codes or strategies for such development, and several researchers have studied gated communities at the international level [Citation17]. Few local studies have shown this field’s evolution, characteristics, types, features, or configurations. These studies were descriptive rather than analytical [Citation7,Citation15]. Therefore, designers and architects should develop appropriate methods and quantitative indicators to gain a complete overview of gated communities from an assessment perspective. Fostering the social interaction can help them avoid the isolation and alienation of users from their surrounding context, which is often criticized from a social point of view [Citation18].

This research aims to examine how social interaction affects residents’ satisfaction levels in gated communities. To achieve this aim, we define social sustainability and gated communities and then outline the necessary steps, such as adapting a framework, conducting spatial analysis, and collecting on-field user data. The purpose is to examine the social sustainability of gated communities and highlight their impact on residents’ social interactions. The article addresses the issue of limited social interaction among residents of gated communities and suggests possible solutions.

Urban spaces within gated communities should be reconsidered when designing modern housing. Investigating a case study in the Greater Cairo Region is expected to yield significant improvements in social interactions between residents by providing a well-designed physical setting and a socially diverse community. Moreover, a descriptive analysis interprets the collected data to provide helpful information and findings. The research findings represent the significance of social interaction inside gated communities and serve as a platform for implementing policies and strategies to enhance this aspect.

Background

Social sustainability

Since modernized urban development began in the late 19th century, many urban issues have appeared regarding the ongoing communities’ sustainability [Citation19]. Responding to the degradation of the balance between the environment and the economy, sustainable development emerged to fill this gap [Citation3]. The global community took several steps to overcome the shift in the balance between the sustainability triad. The General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the formulated plan to evolve the strategies for sustainable development. The report’s primary definition of sustainable development is meeting the present’s needs without compromising the future generation’s ability to meet them [Citation13].

It is agreed that the various debates about dimensions of sustainability should be adequately addressed in policymakers’ priorities [Citation6,Citation20]. Environmental and economic aspects have been the driving force behind the sustainable development debate since its inception in the late 1990s, while the social dimension of sustainability has been the least studied of the three pillars [Citation21]. Sustainability has gained importance since the beginning of the 21st century [Citation22–24]. Despite the growing attention toward social sustainability, significant divergences exist in the current literature on defining and measuring social sustainability in residential communities [Citation25]. Different definitions, conceptualizations, and measurement schemes of social sustainability make it challenging to compare the results of several studies and integrate past findings into a single body of knowledge [Citation26,Citation27]. Therefore, a fundamental prerequisite for progress in this field is the creation of theoretical concepts and a reliable and valid measurement scale [Citation7,Citation28,Citation29]. According to Dempsey et al. [Citation21], the definition of social sustainability is rooted in community relations and interaction with the environment where they live [Citation21]. Social sustainability means the ability of an entire city to function as a sustainable, long-term living environment for human interaction, communication, and cultural development [Citation12]. Research contributed effectively to fill the gap in the social sustainability literature and its significance on the built environment through different approaches [Citation613Citation713Citation1313Citation2913Citation55,,].

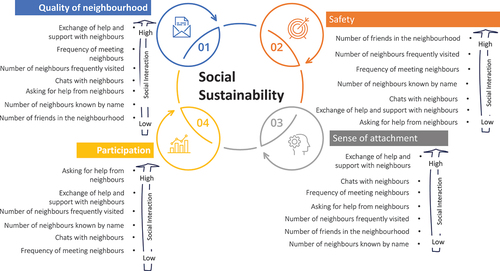

Literature gives us four essential insights to develop an integrated framework for measuring the social sustainability of city neighborhoods. First, it is multiscale, where social sustainability can be measured and operated on various scales, from the neighborhood to the regional and outer regions [Citation26,Citation30]. Research implies that the relevance of the proposed criteria concerning the geographical territory should be considered when evaluating social sustainability [Citation31]. Secondly, various qualitative and quantitative methodologies measure social sustainability indicators [Citation21,Citation32]. Thirdly, although we found a wide range of definitions and conceptualizations for social sustainability, it has tended to focus on certain fundamental concepts like equality, democracy and social involvement, social inclusion and social mix, community interaction, sense of place, security and the quality of environment and housing [Citation26]. Fourthly, social sustainability has been identified as encompassing tangible and intangible attributes of the environment concerning a wide range of social characteristics (). It indicates the need to measure tangible and intangible attributes in an integrated framework [Citation43,Citation56].

Table 1. Social sustainability aspects.

Building on current efforts to evaluate social sustainability, Shirazi and Keivani [Citation36] proposed a working definition of sustainable urban neighborhoods. Research developed an integrated framework combining quantitative and qualitative characteristics in the same structure to provide more detailed insight into sustainability dynamics [Citation7]. Accordingly, socially sustainable neighborhoods are defined for this research as areas in which significant social characteristics are exercised and practiced by the inhabitants in the neighborhood area at acceptable and satisfactory standards [Citation31].

In that respect, social characteristics are essential elements of a socially sustainable neighborhood in terms of their impact on social ties and interaction, cooperation between communities, community cohesion, safety, and security. This definition suggests a tripartite structure defined as a ‘triad of social sustainability’ that includes the space in which social sustainability is practiced and evaluated (neighborhood), the practice of social qualities by the population (neighboring) and the people who practice it (neighbors) [Citation37]. Each factor of the tripartite structure has its definition and aspects ().

Figure 1. Triad of social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods, pillars, and indicators. Source: the authors based on Opp [Citation38].

![Figure 1. Triad of social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods, pillars, and indicators. Source: the authors based on Opp [Citation38].](/cms/asset/ead1589e-0571-4807-aa91-198273218711/thbr_a_2287772_f0001_oc.jpg)

This paper focuses on the neighboring part and social interaction indicator. Two sets of qualities define neighboring: the resident’s relations and the attitude of the neighbors from the social perspective. Some fundamental principles have been developed to fulfill the mentioned set of qualities. These qualities include equity, democracy, participation, and civic society; social inclusion and mix; social networking and interaction; livelihood and sense of place; safety and security; human well-being and quality of life.

Social interaction and the gated communities

Urban social sustainability is crucial in creating inclusive and liveable cities that promote well-being and quality of life [Citation28]. Researchers focused on creating a clear framework to measure community social sustainability. This led to several proposals for different sets of indicators and parameters representing social sustainability dimensions, like the indicators proposed in (). Social interaction lies at the heart of this endeavor. It plays a vital role in shaping urban communities and fostering a sense of belonging and cohesion among their inhabitants [Citation14]. Social interaction is defined as the glue that holds society together and acts as a ‘social support system’ [Citation13]. It covers the interactions between two or more people and looks at various forms of interaction, including eye contact, face-to-face conversations, smiling, talking, speaking, winking, debating, and discussion. These elements are crucial for community development and the cultivation of social capital, which involves shared values and networks that enable cooperation and collective action [Citation39].

Table 2. Neighboring indicators.

Throughout history, subjective findings focus on the role of social actors such as residents of gated communities. The motivation of these social actors plays a significant role in ‘gating’ [Citation1,Citation5,Citation18]. The primary cause for that category is the desire of families to improve their standard of living, avoiding city problems such as people who ask for money and food, and a search by some social groups for societal homogeneity, status, or exclusiveness in an overall process of degradation of society [Citation40]. Literature summarized the factors affecting residents’ opinions about Egyptian gated communities in four key areas [Citation40]:

safety and security factors,

social control and grouping of certain interpersonal groups with each other,

privacy, protection of property values,

community well-being.

Urban studies added that gated communities have achieved each attraction factor using certain features: the gates and the design of walls [Citation5,Citation41]. Research describes the essential role of walls in the gated community, referring to people’s need to see them as a means of security and guards [Citation18]. The urban design and landscape architects, housing types and patterns, residents’ economic status who could afford it, scale, location, traffic, and finally, its value and the resale value.

Without social interaction, individuals in a community must be defined as people who live their individual lives and do not display any attachment to those communities [Citation18]. To be considered a socially sustainable society, people should live, work together, and engage with each other [Citation13]. The following measures are proposed for evaluation: the number of neighbors known by name, the frequency of meeting neighbors, the number of friends in the neighborhood, the number of neighbors frequently visited, the request for help from neighbors and the exchange of assistance and support with neighbors [Citation39]. As a result, social interaction plays a vital role in promoting social sustainability on various fronts. First, it develops a sense of community identity and belonging [Citation40]. Regular interactions between residents create opportunities for shared experiences, social support, and the establishment of informal networks [Citation13,Citation42].

These elements contribute to a stronger sense of community cohesion, and resilience is crucial for addressing local challenges and promoting sustainable development [Citation18]. Urban living can be isolating and stressful, leading to feelings of loneliness and mental health issues [Citation41]. Social interaction provides a buffer against these negative impacts by fostering social support systems and reducing feelings of isolation [Citation29,Citation41]. Social relations are linked to enhanced mental health, increased life satisfaction, and a higher overall quality of life [Citation39]. In addition, inclusive communities embrace diversity and actively seek to integrate individuals from diverse backgrounds and cultures [Citation10].

Social interaction facilitates cross-cultural understanding, diminishes prejudice, and promotes social inclusion. Engaging with people from diverse backgrounds makes urban dwellers more accepting and open-minded, creating a vibrant and inclusive social fabric [Citation43]. Social interaction is not limited to the social sphere but also influences the economic aspects of urban life [Citation12]. Strong social ties can increase economic opportunities by sharing information, knowledge, and resources within the community [Citation44]. Social networks can catalyze entrepreneurship and innovation, contributing to economic prosperity in urban areas [Citation45].

Although social interaction is crucial for urban social sustainability, several challenges can impede its development and prevalence. For instance, urban design can promote or hinder social interaction [Citation46]. The layout of neighborhoods, public spaces, transportation systems, and the presence of green areas can influence how people interact with each other. Poorly designed urban spaces, lack of green areas, and inadequate public transportation can isolate individuals and limit opportunities for social engagement [Citation42]. Digital communication and social media have revolutionized how people connect [Citation47].

Technology can facilitate long-range communication and reduce face-to-face interactions in local communities. Striking a balance between digital connectivity and physical social interaction is essential for urban social sustainability [Citation44]. To overcome these obstacles, communities should take bold initiatives to promote social interaction within their urban context. The local governments should prioritize community participation in urban planning and development initiatives to empower individuals and strengthen social bonds [Citation57]. Moreover, creating well-designed spaces that encourage social interaction is essential. Parks, plazas, community centers, and other gathering spaces can catalyze social engagement [Citation42]. Encouraging walkability and cycling in cities can increase face-to-face interactions among residents, as people are more likely to engage with their surroundings when they move actively through the city [Citation46].

Methods and materials

Case study

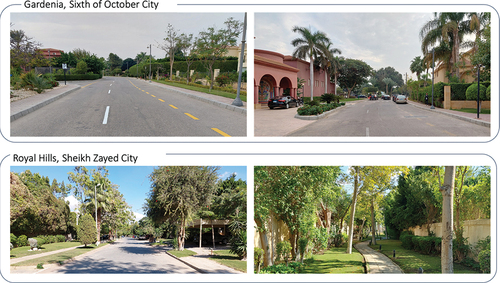

It is becoming increasingly popular to live in private, enclosed residential areas. In both developed and developing countries, gated communities are becoming a new trend in the real estate market and across other sectors such as housing, businesses, or retail [Citation15]. A gated community is a residential or housing estate with strictly controlled entrances. Gated communities are areas in which the perimeter walls, fences, guards, and other restrictions of access mechanisms transform ordinary publicly accessible spaces into private ones [Citation48,Citation49]. Two broad categories can be defined as theoretical explanations for the emergence or development of gated communities: structural and subjective. The theory that gated communities form a spatial manifestation of society’s social, political, and economic structures underpins the structural explanation [Citation50]. shows that Sheikh Zayed City and 6th October City’s gated communities have emerged as organized and well-designedly. Also, this region began the idea of gated communities before any other area in the Greater Cairo Region.

Figure 2. The gated communities in the Greater Cairo Region. Source: based on compiled New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA) data [Citation51].

![Figure 2. The gated communities in the Greater Cairo Region. Source: based on compiled New Urban Communities Authority (NUCA) data [Citation51].](/cms/asset/422fad3f-89b5-43e4-b8d8-154ebd2548dd/thbr_a_2287772_f0002_oc.jpg)

The rapid expansion of gated communities is linked to various social and economic factors that operate at different levels, such as globalization, neoliberal policies, and the privatization of services [Citation52]. These underlying reasons have led to adopting different urban lifestyles, with some Egyptians choosing gated communities for their perceived safety and security from crime [Citation53]. However, such communities may require more government support, including infrastructure maintenance and security services [Citation54]. Additionally, they may attract short-term investments in real estate, property development and activities from international investors. The research summarized the factors affecting residents’ opinions about Egyptian gated communities in four key areas: safety and security factors, social control and grouping of certain interpersonal groups with each other, privateness, protection of property values, and community well-being [Citation15,Citation57].

Studies added that gated communities have been able to achieve each of those attraction factors through the use of certain features: the gates, the design of walls that some want to be seen as walls and some need as a means of security, guards and security [Citation10]. Although gated communities hold various facilities, they accommodate repetitive forms and housing types [Citation44]. The urban patterns of residents’ economic status in gated communities could afford some groups rather than others [Citation41]. The gated communities have similar scale, building forms, and traffic, and finally, their value and the resale value might affect the singularity [Citation17]. shows the urban forms in two Western Greater Cairo Region gated communities.

Data collection

This study focuses on gated communities in the Western part of the Greater Cairo Region, specifically in Sheikh Zayed City and Sixth of October City. Both cities were pioneers in the emergence of the gated community phenomenon in Egypt. Our data collection method was an online questionnaire focused on the neighboring pillar, especially the social interaction indicator. This questionnaire consisted of three parts: A, B, and C. The first part (Part A) targeted some basic information related to the social mix. Part B aimed toward the satisfaction of the indicators mentioned in . The third part (Part C) focused on the satisfaction of the social interaction indicators and parameters.

We assembled a 15-minute questionnaire consisting of 5-scale Likert questions where one indicates strongly agree and five show strongly disagree to represent the users’ satisfaction about the related indicator and parameters (). The sample size was estimated using the following equation [Citation43]. Based on EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) , the sample size should be above 107 respondents.

Table 3. The questions of Part B and Part C.

Where:

SS = sample size

= z-score (1.96 = 95% confidence level)

= population proportion (assumed as 90% or 0.9)

N = population size (141,237 people)

= confidence level (95%)

= margin of error (8%)

The questionnaire was sent to ten community members for preliminary feedback and overcoming obstacles. However, setting a statistically random sample from the targeted individuals was logistically impossible due to limited resources and public data. The revised questionnaire was launched online in February 2023, targeting two hundred responses. One hundred eighteen responses were gathered for three months, giving the authors of the current study a sufficient sample for logical, statistical analysis. For data analysis, we used Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software for descriptive analysis to interpret the satisfaction values of each indicator and then a correlation analysis to study the relation between the indicators and the social interaction parameters for further inspection.

Results and discussion

This study utilized EquationEquation 1(1)

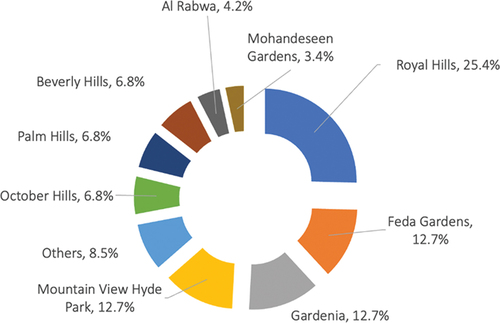

(1) to determine the required sample size. After launching our online survey on social media for the specified duration, we received 118 responses. The initial section gathered demographic and socioeconomic information, including the income levels of the participants, showing a great variety in income. shows participants from various gated communities with different typologies and levels.

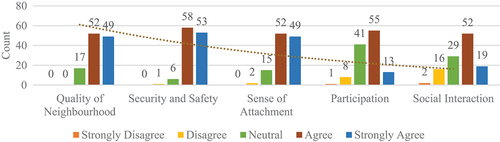

The second section (Part B) tackled the leading neighboring indicators, measuring the level of satisfaction toward each indicator and its application. The results in show that more than 75% of the answers strongly agree and agree, showing a relatively high general satisfaction when addressing social sustainability collectively. Based on our survey, the third section (Part C) concerned social interaction and its key parameters.

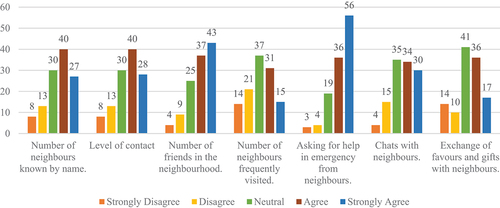

shows that the social aspects like public participation and social interaction break the highly satisfactory trend in the more physical indicators. This represents the users’ concern about the impact of these crucial indicators. Therefore, social aspects should be given more attention when designing the service. According to the findings presented in , the highest level of satisfaction was observed in the ‘asking for help in emergency’ parameter, followed by the ‘number of friends in the neighbourhood’ parameter. It appears that users mainly use social interaction for safety measures and shallow reasons without really developing a genuine connection. This is evident in the decline in visits, exchange of favors and gifts, and chats.

Table 4. The mean values of neighboring indicators’ satisfaction.

This behavior can be related to the insignificance of social interaction in the users’ mind-set and shifting the ordinary residents’ character toward isolation as a translation for security. The correlation analysis in sheds light on the strong correlation between all the social interaction parameters and participation indicators. It explains that communities with stronger bonds encourage the residents to collaborate and volunteer to enhance their physical and social context. Furthermore, the sense of attachment indicator is also directly correlated, proving that social interaction still holds the community together and provides the needed motive to deal with the whole gated community as a home, not only the owned residence.

Table 5. Correlation analysis matrix between social interaction and the other factors that affect social sustainability. Source: the authors.

This study focuses on social interaction, which is the foundation of any community and functions as a support system. However, the users’ perception of their community’s quality and the amenities and services provided does not correlate with social interaction. This research revealed that the significance of social interaction has diminished due to several factors, such as the emergence of online social media, the security crisis since 2011, and the shift toward isolation. The present findings also indicate that people in our case study are becoming more self-centered and less inclined to participate in group activities. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that people feel more insecure and untrusting, which has resulted in them wanting to protect themselves by avoiding social interaction.

The main finding of the current study is that the social interaction that directly affects social sustainability was affected differently by four factors: quality of life, safety, sense of attachment and participation in our case studies. This study shows social interaction is essential for social sustainability. Quality of life, safety and participation are the key factors influencing its outcomes. This study can inform policies that foster sustainable social interaction. The factors that affect social interaction can be ranked from high to low based on their effectiveness in social interaction. shows the rank of each factor. The study indicates that the highest priority should be given to factors related to quality of life, such as access to transportation, access to healthcare, and the availability of affordable housing. Safety and participation should also receive high priority, as these two factors are essential for meaningful social interaction. Finally, the study also suggests that policies should target lower priority factors such as adequate infrastructure.

Our results align with previous studies confirming that there is a general and global noticeable shift away from social interaction reflecting the nature of modern urban life, especially the neighborhood scale [Citation24,Citation30]. Furthermore, recent research stated that the social interaction indicator is one of the lowest neighboring indicators compared to other neighboring indicators [Citation7,Citation21,Citation33]. Previous research also suggests that people are more likely to interact with similar people regarding age, race, and socioeconomic status [Citation45]. This result is in line with a previous study and could be due to a lack of understanding of the importance of interacting with different people [Citation57]. Moreover, it could also result from a lack of resources or opportunities to interact with others [Citation38].

This research had some limitations. Data collection was limited to online surveys, and in-field interviews and surveys were logistically unavailable. Also, it adopted a more generalized approach rather than targeting a specific gated community typology. Furthermore, the adopted indicators were not enough to test social sustainability in gated communities. Parks, clubs, sidewalks, and service centers are some of the main advantages of this type of development. Based on their generic functions, these zones should accommodate most social interaction activities inside any gated community. However, the indicators did not consider the specific features of this type of development, such as the fact that gated communities are often isolated from their surroundings and lack access to public transportation. Furthermore, they did not consider the specific design of these zones, such as the presence of green spaces or whether the community was organized into different neighborhoods.

Conclusion

This study provides a brief timeline of the phenomenon of gated communities in Egypt, showing that it is expanding enormously all over Egypt and affecting the mind-set of the users that resided previously in conventional residents and neighborhoods, causing a shift in the priorities and decision-making when choosing their new homes. Due to this expansion, it was necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of the relatively new housing concept on the social sustainability of the community.

This study examined social sustainability in gated communities in the western part of the Greater Cairo Region by analyzing its concepts and indicators, especially social interaction, and personal relationships. The results showed that social sustainability reached a satisfying level in the indicators related to the physical features like safety and security and quality of neighborhood fulfilling the prioritized self-needs of the users. The results also showed a gap between the importance of social interaction in theory and application. While, in theory, social interaction offers a sense of community and attachment to the residents, residents did not prioritize social interaction as an essential factor in living inside a gated community or affecting their overall satisfaction.

This study could set up further social sustainability assessment in gated communities in the Greater Cairo Region. Hence, future research should consider various sizes and types of gated communities to broaden the spectrum of sample size. Future studies should consider an analysis of the social pattern to provide a clear vision of the challanges of gated communities. Our results could increase investors’ interest in establishing socially oriented gated communities and shift the users’ mind-set back to the social dimension to mitigate any risks. Knowing that gated communities represent a highly rewarded marketing opportunity for investors, minimizing any negative concerns can promote a healthier community and attract a broader spectrum of users; this can be implemented by regulations aiming for social legislation to promote the social dimension of the sustainable development and maintain an integrated social network within the physical limits of the gated community.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Eizenberg E, Jabareen Y. Social sustainability: a new conceptual framework. Sustainability. 2017;9(1):1–16. doi: 10.3390/su9010068

- Ouria M. Sustainable urban features and their relation with environmental satisfaction in commercial public space: an example of the great bazaar of Tabriz, Iran. Int J Urban Sustain Develop. 2019;11(1):100–121. doi: 10.1080/19463138.2019.1579726

- Dixon T. Measuring the social sustainability of new housing development: a critical review of assessment methods. Journal of Sustainable Real Estate. 2019;11(1):16–39. doi: 10.22300/1949-8276.11.1.16

- Palich N, Edmonds A. Social sustainability: creating places and participatory processes that perform well for people. Environ Design Guide. 2015 November;1–13.

- Urfalı F, Aras L. Measuring social sustainability with the developed MCSA model: Güzelyurt case. Sustainability. 2019;11(9):1–20. doi: 10.3390/su11092503

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. Developing a guiding framework based on sustainable development to alleviate poverty, hunger and disease. ARCH. 2023. doi:10.1108/ARCH-03-2023-0076

- Asaad M, Farouk GH, Elshater A, et al. Global South research priorities for neighbourhood sustainability assessment tools. Open House International. 2023;1–18. doi: 10.1108/OHI-10-2022-0278

- Dessouky N, Wheeler S, Salama AM. The five controversies of market-driven sustainable neighborhoods: an alternative approach to post-occupancy evaluation. Soc Sci. 2013;12(7):1–16. doi: 10.3390/socsci12070367

- Redhead G, Bika Z. ‘Adopting place’: how an entrepreneurial sense of belonging can help revitalise communities. Entrepreneurship Reg Dev. 2022;34(3–4):222–246. doi: 10.1080/08985626.2022.2049375

- Alkan-Gökler L. Gated communities in Ankara: are they a tool of social segregation? International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis. 2017;10(5):687–702. doi: 10.1108/IJHMA-03-2017-0032

- McMahon E, Isik L. Seeing social interactions. Trends In Cognitive Sciences, Ahead-Of-Print. 2023;1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2023.09.001

- Abusaada H, Elshater A. Improving visitor satisfaction in Egypt’s Heliopolis historical district. J Eng Appl Sci. 2021;68(1):11–22. doi: 10.1186/s44147-021-00022-y

- Elshater A, Abusaada H, Alfiky A, et al. Workers’ satisfaction vis-à-vis environmental and socio-morphological aspects for sustainability and decent work. Sustainability. 2022;14(3):1–25. doi: 10.3390/su14031699

- Murat D, Gür M, Sezer FŞ. Interaction between life satisfaction and housing and neighborhood satisfaction: “privileged” housing areas in the city of Bursa, Turkey. Journal of Housing and The Built Environment. 2023;38(3):1735–1760. doi: 10.1007/s10901-023-10014-4

- Almatarneh RT. Choices and changes in the housing market and community preferences: reasons for the emergence of gated communities in Egypt: a case study of the Greater Cairo Region, Egypt☆. Ain Shams Engineering Journal. 2013;4:563–583. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2012.11.003

- Tanulku B. Gated communities: from “self-sufficient towns” to “active urban agents”. Geoforum. 2012;43(3):518–528. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.11.006

- Elshater A, Abusaada H, Afifi S. What makes livable cities of today alike? Revisiting the criterion of singularity through two case studies. Cities. 2019;92:273–291. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2019.04.008

- Bandauko E, Arku G, Nyantakyi-Frimpong H. A systematic review of gated communities and the challenge of urban transformation in African cities. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment. 2022;37(1):339–368. doi: 10.1007/s10901-021-09840-1

- Blewitt J. Understanding sustainable development. London: Earthscan; 2017.

- Colantonio A. Urban social sustainability themes and assessment methods. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers - Urban Design and Planning. 2015;163(2):79–88. doi: 10.1680/udap.2010.163.2.79

- Dempsey N, Bramley G, Power S, et al. The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sustain Dev. 2011;19(5):289–300. doi: 10.1002/sd.417

- Doğu FU, Aras L. Measuring social sustainability with the developed MCSA model: güzelyurt case. Sustainability. 2018;11(9):1–20. doi: 10.3390/su11092503

- Staniškienė E, Stankevičiūtė Ž. Social sustainability measurement framework: the case of employee perspective in a CSR-committed organisation. J Clean Prod. 2018;188:708–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.269

- Vallance S, Perkins HC, Dixon JE. What is social sustainability? A clarification of concepts. Geoforum. 2022;42(3):342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2011.01.002

- Ghahramanpouri A, Lamit H, Sedaghatnia S. Urban social sustainability trends in research literature. Asian Social Sci. 2013;9(4):1–9. doi: 10.5539/ASS.V9N4P185

- Shirazi MR, Keivani R. Urban social sustainability: theory, policy and practice. London: Routledge; 2020.

- Yoo C, Lee S. Neighborhood built environments affecting social capital and social sustainability in Seoul, Korea. Sustainability. 2016;8(12):1–22. doi: 10.3390/su8121346

- Colantonio A. The challenge of social sustainability: revisiting the unfinished job of defining and measuring social sustainability in an urban context. In: Haas T Olsson K editors. Emergent urbanism. London: Routledge, pp. 1–10:2014.

- Larimian T, Freeman C, Palaiologou F, et al. Urban social sustainability at the neighbourhood scale: measurement and the impact of physical and personal factors. The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability. 2020;25(10):747–764. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2020.1829575

- Shirazi MR, Keivani R. Critical reflections on the theory and practice of social sustainability in the built environment – a meta-analysis. Local Environ. 2017;22(12):1526–1545. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2017.1379476

- Salama AM, Patil MP, MacLean L. Urban resilience and sustainability through and beyond crisis – evidence-based analysis and lessons learned from selected European cities. Smart Sustain Built Environ. 2023:ahead-of-print. doi: 10.1108/SASBE-08-2023-0208

- Lang W, Chen T, Chan EH, et al. Understanding livable dense urban form for shaping the landscape of community facilities in Hong Kong using fine-scale measurements. Cities. 2018;84:34–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.07.003

- Debrunner G, Jonkman A, Gerber J-D. Planning for social sustainability: mechanisms of social exclusion in densification through large-scale redevelopment projects in Swiss cities. Housing Studies. 2022;1–21. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2022.2033174

- Kuletskaya D. Concepts of use-value and exchange-value in housing research. Housing, Theory and Society. 2023;40(5):589–606. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2023.2238740

- Din HS, Shalaby A, Farouh HE, et al. Principles of urban quality of life for a neighborhood. HBRC Journa. 2023;9(1):86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.hbrcj.2013.02.007

- Shirazi MR, Keivani R. Social sustainability of compact neighbourhoods evidence from London and Berlin. Sustainability. 2021;13(4):1–20. doi: 10.3390/su13042340

- Shirazi MR, Keivani R. The triad of social sustainability: defining and measuring social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods. Urban Res Pract. 2019;12(4):448–471. doi: 10.1080/17535069.2018.1469039

- Opp SM. The forgotten pillar: a definition for the measurement of social sustainability in American cities. Local Environ. 2017;22(3):286–305. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2016.1195800

- Enssle F, Kabisch N. Urban green spaces for the social interaction, health and well-being of older people— an integrated view of urban ecosystem services and socio-environmental justice. Environ Sci Policy. 2020;109:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.04.008

- Ehwi RJ, Morrison N, Tyler P. Gated communities and land administration challenges in Ghana: reappraising the reasons why people move into gated communities. Housing Studies. 2021;36(3):307–335. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2019.1702927

- Ehwi RJ. Walls within walls: examining the variegated purposes for walling in Ghanaian gated communities. Housing Studies. 2022;38(4):527–551. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2021.1900795

- El-Metwally Y, Khalifa M, Elshater A. Quantitative study for applying prospect-refuge theory on perceived safety in Al-Azhar Park, Egypt. Ain Shams Eng J. 2021;4(4):4247–4260. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2021.04.016

- Elshater A, Abusaada H, Tarek M, et al. Designing the socio-spatial context urban infill, liveability, and conviviality. Built Environment. 2022;48(3):341–363. doi: 10.2148/benv.48.3.341

- Abed AR, Mabdeh SN, Nassar A. Social sustainability in gated communities versus conventional communities: the case of Amman. International Journal of Sustainable Development and Planning. 2022;17(7):2141–2151. doi: 10.18280/ijsdp.170714

- Dederichs K. Join to connect? Voluntary involvement, social capital, and socioeconomic inequalities. Social Networks. 2024;76:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2023.07.004

- Wael S, Elshater A, Afifi S. Mapping user experiences around transit stops using computer vision technology: action priorities from Cairo. Sustainability. 2022;14(17):1–20. doi: 10.3390/su141711008

- Elshater A, Abusaada H. Exploring the types of blogs cited in urban planning research. Plan Pract Res. 2023;38(1):62–80. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2022.2085352

- Soyeh KW, Asabere PK, Owusu-Ansah A. Price and rental differentials in gated versus non-gated communities: the case of Accra, Ghana. Housing Studies. 2020;36(10):1644–1661. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2020.1789566

- Vesselinov E, Cazessus M, Falk W. Gated communities and spatial inequality. J Urban Affairs. 2016;29(2):109–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00330.x

- Shirazi MR, Keivani R, Brownill S, et al. Promoting social sustainability of urban neighbourhoods: the case of Bethnal green, London. Int J Urban Reg Res. 2020;46(3):441–465. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12946

- New Urban Communities Authority. 2023. New Urban Communities Authority. Retrieved October 2023, from New Urban Communities Authority: https://nuca-services.gov.eg/#/home

- Hassan DK, Hewidy M, Fayoumi MA. Productive urban landscape: exploring urban agriculture multi-functionality practices to approach genuine quality of life in gated communities in Greater Cairo Region. Ain Shams Eng J. 2022;13(3):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.asej.2021.10.003

- Shamseldin AK. Proposal of adapting the assessment weights of GPRS for different gated communities’ positions. HBRC J. 2018;14(2):224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.hbrcj.2016.02.001

- Qureshi H. Physical, social and economic characteristics of gated communities for a living choice in Karachi-Pakistan: comparative analysis of Kaneez Fatima (CHS) and Naya Nazimabad. J Asian Afr Stud. 2023:ahead-of-print. doi: 10.1177/00219096231200587

- Asaad M, Hassan GF, Elshater A, et al. Analytical hierarchy process for ranking green neighbourhood efforts in the Middle East and North Africa region. ARCH. 2023. doi: 10.1108/ARCH-08-2023-0205.

- Abusaada H and Elshater A. Urban design assessment tools: a model for exploring atmospheres and situations. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Urban Des. Plan. 2020;173(6):238–255. doi: 10.1680/jurdp.20.00025.

- Ahmed N, Elshater A, Afifi S. The community participation in the design process of livable streets. Vol. 296. Innovations and Interdisciplinary Solutions for Underserved Areas. InterSol 2019. Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering. Springer; 2019. p. 144–157. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-34863-2_13