Abstract

There are several studies that showed the high prevalence of high-risk sexual behaviors among youths, but little is known how significant the proportion of higher risk sex is when the male and female youths are compared. A meta-analysis was done using 26 countries’ Demographic and Health Survey data from and outside Africa to make comparisons of higher risk sex among the most vulnerable group of male and female youths. Random effects analytic model was applied and the pooled odds ratios were determined using Mantel–Haenszel statistical method. In this meta-analysis, 19,148 male and 65,094 female youths who reported to have sexual intercourse in a 12-month period were included. The overall OR demonstrated that higher risk sex was ten times more prevalent in male youths than in female youths. The practice of higher risk sex by male youths aged 15–19 years was more than 27-fold higher than that of their female counterparts. Similarly, male youths in urban areas, belonged to a family with middle to highest wealth index, and educated to secondary and above were more than ninefold, eightfold and sixfold at risk of practicing higher risk sex than their female counterparts, respectively. In conclusion, this meta-analysis demonstrated that the practice of risky sexual intercourse by male youths was incomparably higher than female youths. Future risky sex protective interventions should be tailored to secondary and above educated male youths in urban areas.

Résumé

Il existe plusieurs études qui montrent la forte prévalence de comportements sexuels à risque élevé chez les jeunes, mais peu est connu comment significativement la proportion des rapports sexuels à haut risque est lorsque les jeunes mâles et femelles sont comparés. Une méta-analyse a été effectuée à l'aide 26 pays Enquête démographique et de santé des données provenant de l'extérieur de l'Afrique et de faire des comparaisons des rapports sexuels à haut risque parmi les groupes les plus vulnérables de jeunes mâles et femelles. Effets aléatoires modèle analytique a été appliquée et le regroupement des rapports de cotes (RC) ont été déterminés à l'aide de Mantel-Haenszel méthode statistique. Dans cette méta-analyse, 19,148 hommes et 65,094 femmes jeunes qui ont déclaré avoir des rapports sexuels dans une période de douze mois ont été inclus. L'ensemble ou ont démontré que des rapports sexuels à risque était dix fois plus élevée chez les jeunes hommes que chez les femelles de jeunes. La pratique des rapports sexuels à haut risque par les jeunes hommes âgés de 15 à 19 ans était plus de vingt sept fois plus élevés que leurs homologues de sexe féminin. De même, les jeunes hommes dans les zones urbaines, appartenait à une famille avec milieu de plus haut indice de richesse, et éduqués au secondaire et au-dessus étaient plus de 9 fois, 8 fois et 6 fois en péril de pratiquer des rapports sexuels à risque que leurs homologues de sexe féminin, respectivement. En conclusion, la présente méta-analyse a démontré que la pratique de rapports sexuels risqués par les jeunes hommes était incomparablement plus élevés que ceux des femmes jeunes. Les futures interventions de protection des rapports sexuels à risque devraient être adaptées à l'enseignement secondaire et au-dessus de jeunes hommes instruits dans les zones urbaines.

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) (Citation1989) defines youth as those persons between 15 and 24 years of age and about 85% of them live in developing countries. In literature, risky sexual behavior has been defined as engaging in unprotected sex, having multiple sexual partners, engaging in sex with older partners, and sexual debut in an earlier age (Dancy, Kaponda, Kachingwe & Norr Citation2006; Monasch & Mahy Citation2006; Walcott, Meyers & Landau Citation2008). However, the interest of this meta-analysis was youths who were engaging in unprotected sex with non-regular partner in about a 12-month period.

There are several studies that showed the high prevalence of high-risk sexual behaviors among youths which make them highly vulnerable to sexually transmitted infections (STI) including HIV, substance use and delinquency, which are thought to be more common in low-income countries (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2011; Kingdom of Cambodia Citation2010; Pamela, Mary, Jennifer, Eileen, Kimberly & Mary Citation2002; Silverman Citation2013; Walcott et al. Citation2008). This is because young people often times are less aware of the life skills of how to protect themselves from sexual risk-taking behaviors in low-income countries (Pamela et al. Citation2002; Silverman Citation2013; Upreti, Regmi, Pant & Sinkhada Citation2009).

UNAIDS (Citation2010) report has shown about fourfold increment in engaging with multiple sexual partners among male youths. There are also other reports that showed the high proportion of having multiple sexual partners and low utilization of condoms by male youths (Hindin & Fatusi Citation2009; Pamela et al. Citation2002; Upreti et al. Citation2009). In all Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data, the proportion of higher risk was found inversely related to age in both men and women aged 15–49 years (MEASURE DHS Citation2013). A systematic review has shown that adolescents aged 15–19 years were at risk of acquiring STI including HIV and unplanned pregnancies because of multiple partnerships and insufficient condoms use (Doyle, Mavedzenge, Plummer & Ross Citation2012).

A meta-analysis of risky sexual behavior in male youth has also shown that those aged 15–19 years were having about eightfold increased risk of practicing higher risk sex (Berhan & Berhan Citation2015). Furthermore, three previous vertical meta-analyses among men aged 15–49 years, women aged 15–49 years and youths aged 15–24 years have also shown that higher risk sex was associated with living in urban areas, being educated to secondary and above, and had middle to highest wealth index (Berhan & Berhan Citation2012a study 1; Citation2012b study 2; Berhan & Berhan Citation2015). However, in the previous systematic review (Doyle et al. Citation2012) and meta-analyses (Berhan & Berhan Citation2012a study 1; Citation2012b study 2; Berhan & Berhan Citation2015), the analysis was not done to show how significant the proportion of higher risk sex was when the most at-risk male youths is compared with the most at-risk female youths.

Therefore, the purpose of the current meta-analysis was to make comparisons of higher risk sex among the most vulnerable group of male and female youths (too young, living in urban areas, better educated and belong to middle to highest wealth index family).

Methods

Data source

This meta-analysis focuses on risky sexual behavior of youths using population data accumulated from 26 countries through the DHSs. The detailed description how each DHS data collected is available elsewhere (MEASURE DHS Citation2013). Briefly, MEASURE DHS has been collecting a nationally representative and large sample size household-based data for over 20 years in different parts of the less developed countries using a cross-sectional study design. The sample sizes (19,000 male youths and 65,000 female youths) were determined in the primary studies to make representative of the general population of the included countries. Almost all surveys use the same definitions of terms and similar questionnaires developed by MEASURE DHS. In the majority of the surveys, a two-stage cluster sampling design and strata of urban and rural households were used to select study respondents. The limitations of DHS data are described in detail elsewhere (Vinoda, Bignami-Vanb, Robertc, Mrtina, Rathavutha, Peter, et al. Citation2007).

Study selection

For this meta-analysis, it was possible to find 26 countries' DHS data on the MEASURE DHS website that reported higher risk sex of youths aged 15–19 years in the 12 months preceding the respective surveys in the years between 2003 and 2009. Twenty-one of the 26 included DHS data were from Sub-Saharan African countries (Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Cote Divore, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinee, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mali, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sierra Leon, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe). The remaining five DHS data were from different parts of the world outside Africa (Bolivia, Cambodia, Guyana, Haiti and Vietnam). All surveys used the same definitions of terms and similar questionnaires developed by MEASURE DHS, and they followed a standard procedure. This helps us for comparison of findings on risky sexual behaviors in 12 months' period.

Reporting practice of higher risk sex by study participants in 12 months preceding the respective surveys was a requirement for inclusion of DHS data. With these criteria, 51 DHS were accessed through electronic databases. Twenty-five DHS were excluded mainly due to the lack of higher risk sex data or because of inconsistency in data grouping. Furthermore, since higher risk sex among male and female youths in relation to wealth index was not reported in Cameroon 2004 and Chad 2004 DHS, the two countries' DHS data were not included in the wealth index-related analysis.

Operational definition

In all DHS, higher risk sex was defined as having sexual intercourse with somebody who was neither a spouse nor a cohabiting partner in the 12 months prior to the survey. In all DHS, the type of higher risk sex assessed was heterosexual type. In this meta-analysis, practicing higher risk sex during the last higher risk sexual encounter was taken as an indicator of risky sexual behavior.

In the majority of the DHS data, educational levels of male and female youths were found grouped as no education, primary, secondary and above. Since the meta-analysis software analyzes only dichotomous data set as dependent or independent variable, educational level of male and female youths was dichotomized as primary or no education, and secondary and above education. The majority of DHS also described the household wealth assets as wealth quintiles. It was noticed even before that wealth index and wealth quintiles were found being used interchangeably.

Wealth index/wealth quintile was used to show household assets (such as the source of water, type of toilet facility, materials used for housing construction, ownership of various durable goods, ownership of agricultural land, ownership of domestic animals and ownership and use of mosquito nets). In this meta-analysis, wealth index is used consistently in all sections of the manuscript. In all DHS, wealth index was found consistently grouped as lowest, second, middle, fourth and highest. To fit in this meta-analysis, wealth index was dichotomized as low or lowest and middle to highest. In this analysis, socio-economic circumstance defines an educational level, residence and wealth index.

Statistical analysis

Using Meta Analyst (Beta 3.13) software (Wallace, Schmid, Lau & Trikalinos Citation2009), five meta-analysis were conducted taking higher risk sex as the dependent variable. The first meta-analysis compared male and female youths’ higher risk sex. Further comparisons of higher risk sex were performed between male and female youths aged 15–19 years, educated to secondary and above, has been living in urban areas, and belonged to a family with middle to highest wealth index.

Pooled odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals across the countries were determined by applying Mantel–Haenszel (M–H) statistical method. Using I2 statistic, heterogeneity among surveys was assessed. Random effects analytic model was applied given that the heterogeneity among the survey's findings was found to be significant (I2 > 50%) with a fixed model. Despite the significant heterogeneity, meta-analysis was preferred to assess the strength of the pooled OR of the selected variables. Sub-group and sensitivity analyses were done, but were not included in the report because of little changes in the overall and sub-group ORs.

Results

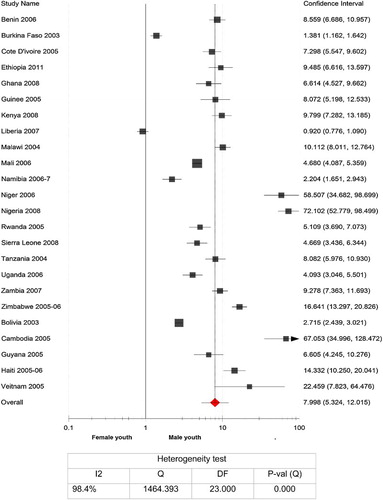

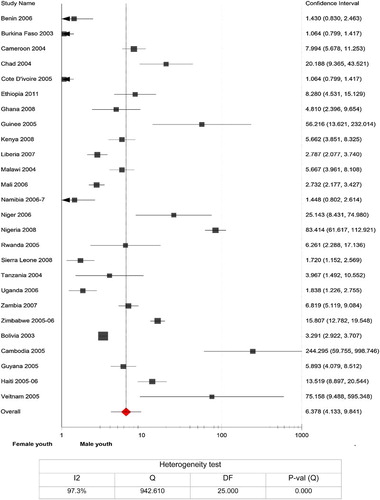

In this meta-analysis, 19,148 male youths and 65,094 female youths who reported to have sexual intercourse in a 12-month period preceding each survey were included. These sample sizes were determined in the primary studies to make representative of the general population. shows the meta-analysis of higher risk sex in male and female youths aged 15–24 years. The odds of higher risk sex among male youths was much higher than female youths. In other words, in all included countries, the practice of higher risk by male youths was much higher than their female counterparts. Specifically, in Cambodia, Chad, Guinea, Haiti, Mali and Vietnam, the practice of higher risk sex among male youths was more than 10-fold of their female counterparts. The overall OR demonstrated that higher risk sex was ten times more prevalent in male youths than in female youths (OR = 10.5; 95% CI: 8.45–12.96). The heterogeneity testing, however, showed a significant variation among the included surveys (I2 = 95.6%).

Fig. 1. Practice of higher risk sex in 12 months among male and female youths aged 15–24 years, 26 countries DHSs (2003–2009).

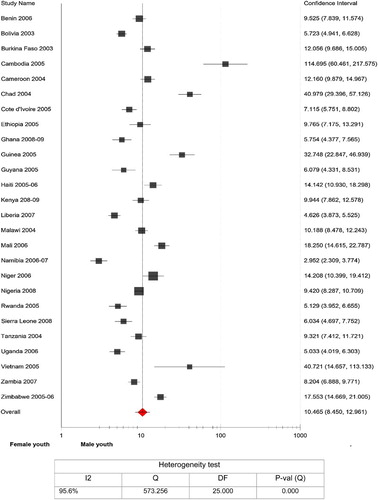

The meta-analysis in was done specifically for male and female youths aged 15–19 years. With the exception of Burkina Faso, the proportion of higher risk sex among male youths was extremely higher than the female youths of the same age category. Relatively low odds of higher risk was found for male youths from Ghana, Liberia, Mali, Namibia, Sierra Leone and Bolivia. As a result, the pooled analysis has shown that the practice of higher risk sex by male youths aged 15–19 years was more than 27-fold higher than that of their female counterparts (OR = 27.3; 95% CI: 14.22–52.55). In the heterogeneity testing, a significant variability among the included surveys was noticed (I2 = 97%).

Fig. 2. Practice of higher risk sex in 12 months among male and female youths aged 15–19 years, 26 countries DHSs (2003–2009).

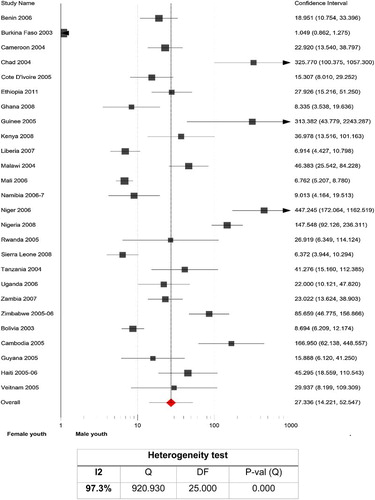

shows the meta-analysis of higher risk sex among male and female youths living in urban areas. The OR of each included country demonstrated that male youths living in urban areas were more at risk for having sexual intercourse with somebody who was neither a spouse nor a cohabiting partner in the twelve-month period than the female youths living in a similar setting. Extremely high proportion of higher risk sex practice by urban male youths was reported from countries like Chad, Cameroon, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Cambodia and Vietnam. The overall OR indicated that male youths in urban areas were more than ninefold at risk of practicing higher risk sex than their female counterparts (OR = 9.1; 95% CI: 6.58–12.47). The heterogeneity testing has shown significant variability (I2 = 96.7%).

Fig. 3. Practice of higher risk sex in 12 months among urban male and urban female youths aged 15–24 years, 26 countries DHSs (2003–2009).

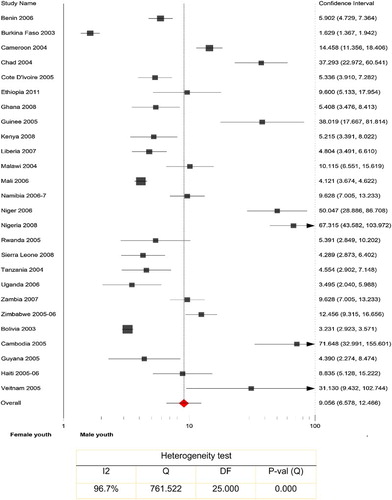

Practice of higher risk sex among male and female youths who were educated to secondary and above is presented in . The data from Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote D'iovoire and Namibia did not show statistically significant association of higher risk sex with either male or female youths whose educational attainment was secondary and above. In twenty-two countries, however, male youths educated to secondary and above were practicing risk sex more than female youths who were educated to the same level. In some countries (Chad, Guinea, Niger, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Cambodia and Vietnam), the association of higher risk sex with secondary and above educated male youths was very high. The pooled analysis has shown a sixfold increased practice of higher risk sex by secondary and above educated male youths (OR = 6.4; 95% CI: 4.13–9.84) with significant variability among the included studies (I2 = 97.3%).

Fig. 4. Practice of higher risk sex in 12 months among male and female youths educated to secondary and above and aged 15–24 years, 26 countries DHSs (2003–2009).

Practice of higher risk sex among male and female youths who belonged to middle to highest wealth index is shown in . With the exception of Liberia, higher risk sex was commonly practiced by male youths who were grouped as middle to highest wealth index. Relatively very high association of higher risk sex with male youths was observed in Malawi, Niger, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, Cambodia and Vietnam. In the pooled analysis, the odds of practicing higher risk sex by male youths who belonged to middle to highest wealth index was nearly 8 times higher than the female youths (OR = 7.99; 95% CI: 5.32–12.02).

Discussion

Although previous studies have shown the association of higher risk sex with men and women (aged 15–49 years) living in urban areas, educated to secondary and above, and owned middle to highest wealth index (Berhan & Berhan Citation2012a study 1; Citation2012b study 2), this meta-analysis specifically demonstrated that more male youths were practicing higher risk sex than female youths in all included countries. In other words, in the majority of the included countries, the susceptibility of male youths to higher risk sex was significantly higher than the female youths regardless of the assessed independent variables (sex, age, education, residence and wealth index), which was somehow consistent with several other studies not included in this meta-analysis (Abma, Martinez & Copen Citation2010; Dias, Matos & Goncalves Citation2005; Halpern, Hallfors, Bauer, Iritani, Waller & Cho Citation2004; Hindin & Fatusi Citation2009; Pamela et al. Citation2002; Puente, Zabaleta, Rodríguez-Blanco, Cabanas, Monteagudo, Pueyo, et al. Citation2011; Upreti et al. Citation2009). The consistent and strong association of higher risk sex with male youth is probably a strong evidence to surmise that being a male youth is a stronger predictor of practicing higher risk sex than the other assessed variables.

WHO and UNAIDS review has also shown that about 50% of backlog and new HIV infections were occurring among youths, for which higher risk sex was highly attributed and the risk was more pronounced among the male youths (Ross, Dick & Ferguson Citation2006; UNAIDS Citation2010). However, it was not clearly evident as this meta-analysis has shown how significantly male youths were more at risk than female youths in relation to being too young (15–19 years), living in urban areas, better level of education and belonging to family with middle to highest wealth index.

We posed a question why male youths were more at risk than female youths when the social circumstances are favorable to avoid risk-taking behavior (assuming that living in urban areas and being educated to secondary and above are thought to be an opportunity to be aware of the dangers of risky sexual practice). Until future researchers find a better answer, taking into consideration the previous studies' findings and observations, we attribute the most likely reasons as stated below.

Firstly, since female youths are likely to get married earlier than male youths in developing countries (Singh & Samara Citation1996), the chance of engaging in higher risk sex might be less common than male youths. Secondly, previous studies have also shown that male adolescents were more likely to have multiple sexual partners and less likely to use condoms than their female counterparts (Bruce & Walker Citation2001; CDC Citation2002; Puente et al. Citation2011; Santelli, Lowry, Brener & Robin Citation2000). Thirdly, as previous investigators reported, substance use (alcohol, smoking and drugs) is more common among male youths which is a known factor for initiating and practicing risky sex (Agius, Taft, Hemphill, Toumbourou & McMorris Citation2013; Magnani, Karim, Weiss, Bond, Lemba & Morgan Citation2002; Puente et al. Citation2011; Zabin & Kiragu Citation1998). Fourthly, male youths are also more likely to debut sexual practice in their early age, at which time they may not perceive the risk of having unprotected sexual intercourse with non-regular partners (Berhan, Hailu & Alano Citation2011, Citation2013; Ntaganira, Hass, Hosner, Brown & Mock Citation2012).

Taking all these into account, we hypothesize that it is male youths who are manifesting risky sexual behaviors and they are by far at the core of STI/HIV transmission. This hypothesis can be further extended: even during adulthood, those practicing higher risk sex while in young age is more likely to continue experiencing risky sex compared with their counterparts who prefer to abstain or have safe sex, which was also identified and theorized in several literature (Deardorff, Tschann, Flores & Ozer Citation2010; Futterman Citation2004; Murphy, Brecht, Herbeck & Huang Citation2009). Among female youths who were practicing risky sex, it is still arguable that they might be pushed by the male youths to use substances and lose their conscious decision on sexual orientation and anticipated risks.

In general, this and previous meta-analyses' findings (Berhan & Berhan Citation2012a study 1; Berhan & Berhan Citation2012b study 2; Berhan & Berhan Citation2015) suggest the need of higher risk sex avoidance programs tailored to young male and female youths living in urban areas, joined secondary school and belonged to a family with high wealth index. In other words, in a heterosexual situation where the male youths would be engaging in unprotected sex with young girls and young women, the higher risk sex avoidance programs should address both male and female youths. The higher risk sex avoidance programs should not necessarily be awareness creation alone; rather, the programs should target bringing a behavioral change. This is because the fact that male youths who were practicing higher risk sex were living in urban areas and attained secondary and above education makes the lack of awareness about the risk of HIV/STI transmission questionable. Secondly, several studies have shown that being educated about the consequences of risky sexual practice and cause of HIV/STI transmission does not necessarily result in behavior change (Aoife, David, Kaballa, Kathy, Clemens, Aura, et al. Citation2010; Moor & Davidson Citation2006; Upreti et al. Citation2009). Furthermore, if awareness alone could have brought about significant behavioral change, after about a quarter of a century of campaign on HIV infection across the world, the majority of male youths living in urban areas and better educated should not have been found practicing higher risk sex in the last decade.

Since the setting and culture vary from country to country, it may be unrealistic to recommend specific interventions on higher risk sex avoidance programs. However, there is a large body of data on some protective mechanisms like engaging in religious activity, keeping the family structure integrity, good parents’ control, attending school and avoiding substance use (Agardh, Tumwine & Östergren Citation2011; Berhan et al. Citation2013; Crosby & Miller Citation2002; Fisher & Feldman Citation1998; Magnani et al. Citation2002; McCree, Wingood, Diclemente, Davies & Hirrington Citation2003; Miller & Gur Citation2002; Perrino, Gonzalez-Soldevilla, Pantin & Szapocnik Citation2000; Santelli et al. Citation2000; Santander, Zubarew, Santelices, Argollo, Cerda & Bórquez Citation2008; Shirazi & Morowatisharifabad Citation2009). Among others, religious affinity has got a major impact on adolescents’ positive sexual behavior and some put it as a sole determinant of adolescents’ sexual behavior (Agardh et al. Citation2011; McCree et al. Citation2003; Miller & Gur Citation2002; Shirazi & Morowatisharifabad Citation2009). Furthermore, some authors reported that youths engage in risky sexual practice when their religious adherence is weak (thought to have a ‘gate keeping’ role); or when their parents are reluctant to discourage early sexual experimentation and substance use; or when their sexual decision is influenced by peers (Borawski, Levers-Landis, Lovegreen & Trapl Citation2003; Fehring & Haglund Citation2009; Le & Kato Citation2006). Nevertheless, to implement a strong evidence-based intervention, the significance of these recommendations needs to be further explored so as to identify what is driving better educated male youths to practice risky sex.

This meta-analysis was not without limitation. The limited number of DHS data included outside sub-Saharan Africa might limit us to generalize the findings for all developing countries. The dichotomization of the included independent variables to fit into the meta-analysis software could not allow us to make comparisons across multiple categories. Since other sexual behavior determinants (like ethnicity, religion, peer influence, school engagement and performance, parents’ behavior and relation) were not found in the DHS data, it was not possible to conduct further meta-analysis. In other words, the socio-economic and sociocultural contexts of 26 varied countries could not be controlled. This is because, in the case of HIV infection, the risk of infection is not necessarily mediated by education and wealth.

In conclusion, regardless of the geographic location of the included countries, being female youth was relatively protective for higher risk sex among youths of urban residents, better educated and relatively owned middle to highest wealth index. Therefore, future protective interventions should be tailored to secondary and above educated male youths in urban areas that can bring a behavioral change on avoiding risky sexual practice. To have a better understanding of the motivating factors for higher risk sex, a qualitative study method is highly recommended.

References

- Abma, J. C., Martinez, G. M. & Copen, C. E. (2010). Teenagers in the United States: Sexual Activity, Contraceptive Use, and Childbearing, National Survey of Family Growth 2006–2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics, 23(30). http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_23/sr23_030.pdf (Accessed 13 September 2013).

- Agardh, A., Tumwine, G. & Östergren, P. O. (2011). The Impact of Socio-demographic and Religious Factors upon Sexual Behavior among Ugandan University Students. PLoS One, 6(8), e23670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023670

- Agius, P., Taft, A., Hemphill, S., Toumbourou, J. & McMorris, B. (2013). Excessive Alcohol Use and Its Association with Risky Sexual Behaviour: A Cross-sectional Analysis of Data from Victorian Secondary School Students. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 37(1), 76–82. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12014

- Aoife, M., David, A., Kaballa, M., Kathy, B., Clemens, M., Aura, A., et al. (2010). Long-Term Biological and Behavioral Impact of an Adolescent Sexual Health Intervention in Tanzania: Follow-up Survey of the Community-Based MEMA kwa Vijana Trial. PLoS Med, 7(6), e1000287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000287

- Berhan, Y. & Berhan, A. (2012a). Meta-analysis on Risky Sexual Behaviour of Men: Consistent Findings from Different Parts of the World. AIDS Care, 25(2), 151–159 (Study 1). doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.689812

- Berhan, Y. & Berhan, A. (2012b). Meta-analysis on Higher-Risk Sexual Behavior of Women in 28 Third World Countries. World Journal of AIDS, 2(2), 78–88. www.SciRP.org/journal/wja/ (Study 2). doi: 10.4236/wja.2012.22011

- Berhan, Y. & Berhan, A. (2015). A Meta-analysis of Risky Sexual Behaviour among Male Youth. AIDS Research and Treatment. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/580961. www.hindawi.com/journals (Accessed 28 March 2015).

- Berhan, Y., Hailu, D. & Alano, A. (2011). Predictors of Risky Sexual Behaviour and Preventive Practices among University Students, Ethiopia. African Journal of AIDS Research, 10(3), 225–234. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2011.626290

- Berhan, Y., Hailu, D. & Alano, A. (2013). Polysubstance Use and Its Linkage with Risky Sexual Behaviour in University Students: Significance for Policy Makers and Parents. Ethiopian Medical Journal, 51(1), 13–23.

- Borawski, E. A., Levers-Landis, C. E., Lovegreen, L. D. & Trapl, E. S. (2003). Parental Monitoring, Negotiated Unsupervised Time and Parental Trust: The Role of Perceived Parenting Practices in Adolescent Health Risk Behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(2), 60–70. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00100-9

- Bruce, K. E. & Walker, L. J. (2001). College Students’ Attitudes about AIDS: 1986 to 2000. AIDS Education and Prevention, 13(5), 428–437. doi: 10.1521/aeap.13.5.428.24140

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2002). Trends in Sexual Behavior among High School Students–United States. National and State-Specific Pregnancy Rates for Adolescents–United States, 1995–1997. MMWR. 2002; 49:605–611. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00054814.htm (Accessed 2 August 2013).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2011). Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. www.cdc.gov/yrbs (Accessed 22 October 2013).

- Crosby, R. A. & Miller, K. S. (2002). Family Influences on Adolescent Females’ Sexual Health. In G. M. Wingood & R. J. DiClemente (Eds.), Handbook of Women's Sexual and Reproductive Health, pp. 113–127, New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum.

- Dancy, B. L., Kaponda, C. P., Kachingwe, S. I. & Norr, K. F. (2006). Risky Sexual Behaviors of Adolescents in Rural Malawi: Evidence from Focus Groups. Journal of National Black Nurses Association, 17(1), 22–28.

- Deardorff, J., Tschann, J. M., Flores, E. & Ozer, E. J. (2010). Sexual Values and Risky Sexual Behaviors among Latino Youths. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42(1), 23–32. doi: 10.1363/4202310

- Dias, S. F., Matos, M. G. & Goncalves, A. C. (2005). Preventing HIV Transmission in Adolescents: An Analysis of the Portuguese Data from the Health Behaviour School-Aged Children Study and Focus Groups. European Journal of Public Health, 15(3), 300–304. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki085

- Doyle, A. M., Mavedzenge, S. N., Plummer, M. L. & Ross, D. A. (2012). The Sexual Behaviour of Adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa: Patterns and Trends from National Surveys. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 17(7), 796–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03005.x

- Fehring, R. J. & Haglund, K. A. (2009). The Association of Religiosity, Sexual Education, and Parental Factors with Risky Sexual Behaviors among Adolescents and Young Adults. http://www.lifeissues.net/ (Accessed 13 September 2013).

- Fisher, L. & Feldman, S. S. (1998). Familial Antecedents of Young Adult Health Risk Behavior: A Longitudinal Study. Journal of Family Psychology, 12(1), 66–80. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.12.1.66

- Futterman, D. (2004). HIV and AIDS in Adolescents. Adolescent Medicine Clinics, 15 (2), 369–391. doi: 10.1016/j.admecli.2004.02.009

- Halpern, C. T., Hallfors, D., Bauer, D. J., Iritani, B., Waller, M. W. & Cho, H. (2004). Implications of Racial and Gender Differences in Patterns of Adolescent Risk Behavior for HIV and Other Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 36(6), 239–247. doi: 10.1363/3623904

- Hindin, M. J. & Fatusi, A. O. (2009). Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health in Developing Countries: An Overview of Trends and Interventions. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35(2), 58–62. www.guttmacher.org/pubs/journals/ (Accessed 20 August 2013). doi: 10.1363/3505809

- Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) (2010). Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic. www.unaids.org (Accessed 25 August 2013).

- Kingdom of Cambodia (2010). Most at Risk Young People Survey. Ministry of Education, Youths and Sports. www.aidsalliance.org/includes/Publication/MARYPS_Cambodia (Accessed 26 October 2013).

- Le, T. N. & Kato, T. (2006). The Role of Peer, Parent and Culture in Risky Sexual Behavior for Cambodian and Lao/Mien Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38(3), 288–296. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.12.005

- Magnani, R. J., Karim, A. M., Weiss, L. A., Bond, K. C., Lemba, M. & Morgan, G. T. (2002). Reproductive Health Risk and Protective Factors among Youth in Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30(1), 76–86. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(01)00328-7

- McCree, D. H., Wingood, G. M., Diclemente, R., Davies, S. & Hirrington, K. F. (2003). Religiosity and Risky Sexual Behavior in African-American Adolescent Females. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(1), 2–8. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00460-3

- MEASURE DHS (2013). Publication Search by Country (DHS). http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/DHSQM/DHS (Accessed 2 September 2013).

- Miller, L. & Gur, M. (2002). Religiousness and Sexual Responsibility in Adolescent Girls. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(5), 401–406. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00403-2

- Monasch, R. & Mahy, M. (2006). Young People: The Centre of the HIV Epidemic. World Health Organ Technical Report Series, 938, 15–41.

- Moor, N. & Davidson, K. (2006). College Women and Personal Goals: Cognitive Dimensions That Differentiate Risk-Reduction Sexual Decisions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(4), 577–589.

- Murphy, D. A., Brecht, M.-L., Herbeck, D. M. & Huang, D. (2009). Trajectories of HIV Risk Behavior from Age 15 to 25 in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth Sample. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38(9), 1226–1239. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9323-6

- Ntaganira, J., Hass, L. J., Hosner, S., Brown, L. & Mock, N. B. (2012). Sexual Risk Behaviors among Youth Heads of Household in Gikongoro, South Province of Rwanda. BMC Public Health, 12, 225. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/225 (Accessed 28 September 2013). doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-225

- Pamela, J. B., Mary, K. M., Jennifer, K. L., Eileen, J. S., Kimberly, S. J. K. R. & Mary, K. S. (2002). Predictors of Risky Sexual Behavior in African American Adolescent Girls: Implications for Prevention Interventions. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 27(6), 519–530. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.6.519

- Perrino, T., Gonzalez-Soldevilla, A., Pantin, G. & Szapocnik, J. (2000). The Role of Families in Adolescent HIV Prevention: A Review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 3(2), 81–96. doi: 10.1023/A:1009571518900

- Puente, D., Zabaleta, E., Rodríguez-Blanco, T., Cabanas, M., Monteagudo, M., Pueyo, M. J., et al. (2011). Gender Differences in Sexual Risk Behaviour among Adolescents in Catalonia, Spain. Gaceta Sanitaria, 25(1), 13–19. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2010.07.012

- Ross, D. A., Dick, D. & Ferguson, J. (2006). Preventing HIV/AIDS in Young People: A Systematic Review of the Evidence from Developing Countries. UNAIDS Inter-agency Task Team on Young People. WHO Technical Report Series; No. 938. Geneva. WHO. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/trs/WHO_TRS_938_eng (Accessed 29 December 2012).

- Santander, R. S., Zubarew, G. T., Santelices, C. L., Argollo, M. P., Cerda, L. J. & Bórquez, P. M. (2008). Family Influence as a Protective Factor Against Risk Behaviors in Chilean Adolescents. Revista médica de Chile, 136(3), 317–324.

- Santelli, J. S., Lowry, R., Brener, N. D. & Robin, L. (2000). The Association of Sexual Behaviors with Socioeconomic Status, Family Structure, and Race/Ethnicity among US Adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 90(10), 1582–1588. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.10.1582

- Shirazi, K. K. & Morowatisharifabad, M. A. (2009). Religiosity and Determinants of Safe Sex in Iranian Non-medical Male Students. Journal of Religion and Health, 48(1), 29–36. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9174-1

- Silverman, E. A. (2013). Adolescent Sexual Risk-Taking in a Psychosocial Context: Implications for HIV Prevention. HIV Clinician, Spring, 25(2), 1–5.

- Singh, S. & Samara, R. (1996). Early Marriage among Women in Developing Countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 22(1), 148–157. doi: 10.2307/2950812

- Upreti, D., Regmi, P., Pant, P. & Sinkhada, P. (2009). Young People's Knowledge, Attitude, and Behavior on STI/HIV/AIDS in the Context of Nepal: A Systematic Review. Kathmandu University Medical Journal, 7(4), 383–391.

- Vinoda, M., Bignami-Vanb, A. S., Robertc, G., Mrtina, V., Rathavutha, H., Peter, D.cG., et al. (2007). HIV Infection Does Not Disproportionately Affect the Poorer in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS, 21(Suppl): S17–S28.

- Walcott, C. M., Meyers, A. B. & Landau, S. (2008). Adolescent Sexual Risk Behaviors and School-Based Sexually Transmitted Infection/HIV Prevention. Psychology in the Schools, 45(1), 39–51. doi: 10.1002/pits.20277

- Wallace, B. C., Schmid, C. H., Lau, J. & Trikalinos, T. A. (2009). Meta-analyst: Software for Meta-analysis of Binary, Continuous and Diagnostic Data. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 9(1), 80. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/9/80 (Accessed 26 July 2013). doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-80

- World Health Organization (WHO) (1989). The Health of Youth. Document A42/Technical Discussions/2. Geneva: WHO. hqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1994/WHO_ADH_94.1 (Accessed 7 September 2013).

- Zabin, L. S. & Kiragu, K. (1998). The Health Consequences of Adolescent Sexual and Fertility Behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 29(2), 210–232. doi: 10.2307/172160