ABSTRACT

What goes on within educational institutions can be pivotal for whether and how democracy and political tolerance are nurtured, and peaceful relations between groups encouraged. Several studies oriented to the content of curricula have shown that education in India must be reformed if it is to promote inter-ethnic peace, political tolerance and democracy. The focus of this study, however, is more on the praxis of education – how it is conducted, in what kind of institutional setting it takes place, and what the implications are for inter-ethnic peace. This unique case study of Jammu and Kashmir in India provides unexpected insights into how democratic norms can be promoted in disadvantageous contexts, where open violent conflict prevails and politically intolerant attitudes might normally be expected to result. The findings of this study have important implications for educational reform. First, the authoritarian approach to teaching currently employed in India’s system of primary education needs to be replaced by more modern methods, and corporal punishment must be abolished. Second, the praxis found in at least some of the country’s institutions of higher learning should be encouraged, due to the role it plays in bridging ethno-religious divides and breaking path-dependent trajectories towards political intolerance.

Can peaceful, conciliatory, respectful, tolerant, and democratic attitudes evolve among young adults who have experienced bullying and abusive teachers in primary education – and even if violent conflicts are raging outside the door when they finally reach university? This seems to be true for some students in northern India, even at a time when chauvinistic nationalism is gaining ground. Many public institutions in the state of Jammu and Kashmir in India have suffered badly during the last three decades, due to armed conflicts between insurgent forces, separatists, and armed forces from Pakistan on the one side, and the forces of the Indian government on the other. This is particularly true of the educational sector, at all levels. Nonetheless, in spite of severe challenges and high levels of violence in this region (the violence has fluctuated but always remained present), young individuals display attitudes and uphold norms which run counter to what we might expect, given the findings of earlier studies on political tolerance.

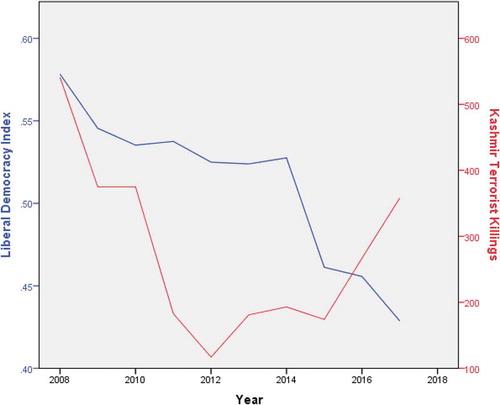

According to one of the world’s most comprehensive democracy indexes – provided by the Varieties of Democracy project – India’s democracy began to decline in 2008, and entered a phase of still more rapid deterioration after 2014. This particularly holds true, as shows, in regard to the ‘Liberal Democracy Index’ (Pemstein et al., Citation2018, Coppedge et al. Citation2018a, Coppedge et al., Citation2018b). This index, which runs from 0 to 1 (with higher values indicating better democratic performance), ‘emphasizes the importance of protecting individual and minority rights against the tyranny of the state and the tyranny of the majority’.Footnote2 Under the leadership of the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the recently re-elected prime minister, Narendra Modi, Hindu nationalism is currently at the zenith of its influence at all levels of governance in most parts of India – and democratic liberties are deteriorating (Basu Citation2015; Varieties of Democracy Citation2018). also shows (see the Y-axis on the right) the number of ‘terrorist killings’ during the same period in the state of Jammu and Kashmir (which is the only state with a Muslim majority), according to data collected and presented by the South Asia Terrorism Portal (South Asia TerrorismPortal Citation2018).Footnote3 Evidently, peace and democracy in India are under threat.

Is it reasonable to assume that education in such a context as this could have any mitigating effects on the conflict in Jammu and Kashmir? Studies of political tolerance and school curricula in South Asia have shown that democracy in India stands on fragile ground, as its educational system does not seem to promote democratic values (Widmalm Citation2016; Flåten Citation2016). On the contrary, educational policies reflect the viewpoint of the religious majority, and school books increasingly present exclusionary nationalist narratives. Such a volatile mix is likely to fan communal conflicts, especially along the Hindu-Muslim divide. What educational reforms will need to be introduced, then, if ethnic peace is to be promoted and the process of autocratization reversed?

Here the research on democracy, peace education, and in particular political tolerance is a natural place to go, in search of both scholarly insights and, possibly, reform strategies. Against this background, I set out in this article to investigate, based on the results of in-depth interviews, what may condition outcomes in a context marked by communal conflicts, weak state structures, and a lack of resources. The findings of this study point to an urgent need for reform in the system of primary education. What is more, the discoveries made here defy the common hypothesis that conflicts and religious divisions will be negatively correlated with democratic values and political tolerance. In the cases presented here, the prevailing praxis in higher education seems to have promoted a democratic outlook – in spite of contextual factors that tend mostly to discourage such attitudes. Jammu and Kashmir thus appears to provide us with an empirical example of a Black Swan – a case that can be imagined in theory but which is very difficult to find in reality, and from which we may have a great deal to learn in other contexts as well. We will follow the logic of inquiry championed by Karl Popper, who devised this metaphor to illustrate his contention that all theories must be falsifiable. Consequently, we need to design our studies and to seek out cases in such a way as to make it possible for current understandings to be disproven, and not just verified (Popper Citation2005 [1935])

Exploring a critical case of education in a conflict-ridden area of india

The above-mentioned challenges to India’s democracy form the point of departure for this study. How are India’s schools and institutions of higher education related to the democratic performance of the country? Earlier work in this field has involved large-scale surveys in which the focus has been on how Indian education in general seems unable to produce democratic norms and attitudes, and in which the presumption has been that this is caused by a curriculum which supports intolerant values rather than democratic ones (Widmalm Citation2016; Flåten Citation2016; Dev Citation1999; Mukherjee, Mukherjee, and Mukherjee Citation2008; Hamza Citation2003). In most previous studies of democratic norms – political tolerance in particular – a direct relationship has been demonstrated between educational level and political tolerance, although economic factors may play an important role as well, as illustrated in (Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus Citation1982).

The basic assumption has long been: the more education, the more democratic and tolerant the political attitudes (Lipset Citation1959). The roots of this way of thinking actually go further back in time (Dewey Citation1916) than the modernization school, the adherents of which set out the claim so clearly. And this perception persists. Research by Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Barry (Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Barry Citation1996) suggest that education per se is the main factor strengthening democratic norms. Education, they argue, promotes democratic enlightenment – almost irrespective of variations in curriculum. This has long been one of the most important reasons for encouraging education as a way of promoting democracy. As long as education is encouraged, the assumption goes, the inevitable result will be rising levels of freedom, equality, democracy, and political tolerance – and the type and content of the education in question need not closely monitored. Early studies on political tolerance (Stouffer Citation1963), as well as later ones that used more refined techniques (Duch and Gibson Citation1992; Gibson Citation1989; Gibson and Gouws Citation2003; Gibson Citation2005; MacKuen et al. Citation2010; Marcus Citation1995; Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus Citation1982), have reinforced the perception.

However, previous studies have indicated that the model in does not find clear empirical support in the case of India, nor in that of Pakistan or Uganda (Widmalm Citation2016). Although economic performance is to some extent related to political tolerance, the connection between education and political tolerance cannot be detected in contexts where resources are very scarce and democratic structures weak. It may be the case there is no direct relationship between education and democracy in places where conditions are much more challenging than in the countries where many studies on the relationship between education and political tolerance have been carried out – namely, in the West. How, then, has India’s democracy managed to survive as well as it has? Perhaps it is largely because the educational system in India furthers economic development, which in turn promotes democratic stability. illustrates this idea. Modernization theory has also suggested such a casual sequence in development (Lipset Citation1959, Citation1981).

However, this line of reasoning may prematurely rule out the importance of the educational system and its capacity to support democracy directly. Deeper investigation is clearly needed here.

The way forward to studying the relationships of interest here is not obvious, as previous researchers have noted (Harris Citation2004). In the case considered here – that of northern India – no programmes to promote peace were implemented in schools as part of a government policy; no strategies were devised as part of a peace process to resolve conflicts and to reconcile clashing groups of the kind studied in other contexts (Harbe and Sakade Citation2009; Danesh Citation2007; Salomon Citation2004). For example, there were no educational programmes aimed specifically at bridging differences and reducing tensions between Hindus and Muslims. Still, certain broader features of the educational system may have served to promote respect for human rights and democratic values in the way observed in other cases (Harris Citation2004). This possibility will be discussed below, in relation to how conflicting groups in the region relate to each other in educational institutions. The design of this study does not enable us to pinpoint whether or not there is a direct causal connection between knowledge and attitudes (Green et al.). The aim is rather to capture something broader – something which the different educational environments have in common. It will be important here to try to identify democratic virtues and tolerant attitudes which, while insufficient for creating peace, are at any rate necessary for it. It is also important to understand in what kind of climate and context peaceful co-existence thrives, and in what kind severe conflicts arise.

Method and context

This study makes use of a comparative method. Considerable time was spent with interviewees, with an eye to identifying the conditions in their educational institutions closely, and ascertaining how these relate to democratic norms and attitudes. Previous surveys tell us that, at a general level, the educational system in India displays deficiencies which are likely to promote conflict or the suppression of minorities. However, large-scale surveys based on limited questionnaires may obscure what is working well – at least from the standpoint of democratic norms. For example, if teaching practices and the curriculum are so biased against democracy, why then do not find a clear negative correlation between educational levels and democratic norms? In all likelihood, there is internal variation here which is hard to detect, but which must be considered and understood.

This examination of democratic values and political tolerance is based, therefore, on strategic samples of two groups of university students. The social-science programmes in which these students were enrolled were very similar, but were situated in very different settings. We carried out the study keeping in mind existing knowledge about what conditions political tolerance and democratic attitudes, with the object of applying it to a crucial case in India – that of Jammu and Kashmir. This state, one of the most divided in India, has experienced interstate wars (in 1947–48, 1965, 1971, and 1999); and it has seen local uprisings of varying intensity since the late 1980s – some with support from Pakistan in particular (Wirsing Citation1994; Ganguly Citation1997; Bose Citation1997; Widmalm Citation2006). Economic development in the state has been seriously hampered by all the conflicts since independence, and this is reflected in its GDP per capita, which is far below the average for India. The main dividing lines for mobilization in the state are religious and geostrategic in nature. The state has a Muslim majority, with the concentration of Muslims being highest in the summer capital, Srinagar, which is located in the Kashmir Valley surrounded by the Himalayas. This is an area which has seen much violence since partition, particularly in the 1990s and early 2000s. Islamic extremists and separatists have had a strong foothold there for a long time. Jammu, where the winter capital is located, connects to the Great Plains of India and has a Hindu majority. The internal conflicts there have not been nearly as severe as those in Srinagar, although the conflicts in the state have divided Jammu’s residents from their counterparts in Srinagar. Wars and conflicts have divided the state in such a way that we might expect outcomes in the two areas to differ with regard to support for democracy and political tolerance. Therefore, for this research project, interviews of university students were conducted, on a small scale and in-depth, with an eye to comparing experiences that we know play a key role in promoting democratic and tolerant attitudes. By investigating the praxis of educational institutions, moreover, this study complements previous ones, which have focused on curriculum content.

This study is based on a total of thirty in-depth interviews in Srinagar and Jammu – fifteen in each. The interviews were carried out in early 2017 under challenging conditions, as illustrated in . The interviewed students were attending two different institutions of higher education, where they were enrolled in comparable social-science programmes at Master’s level. The study was carried out in similar way at the two institutions, with respondents being aged 20–22 at the time they were interviewed. In the university at Srinagar, every fifth student was selected from the roll number list of the class, while in Jammu every third student was chosen from the list. The interviews in both places were conducted in an informal setting. It was just the interviewer and interviewee on their own, in a normal stress-free atmosphere. The responses were written down by the interviewer as the interviewees spoke. Time, patience, energy, and careful planning were needed to carry out the interviews. Ensuring the anonymity of the interviewees was of paramount importance. Carrying out the interviews was complicated, due to the intermitted outbreak of political protests over incidents involving separatist forces and security forces. The interviewer needed considerable time, both to establish a relationship based on trust with the interviewees and to gain the ability to move around in the areas in question without provoking attention. The original idea behind the design of the study was that Jammu would provide a more peaceful setting, and Srinagar a less peaceful one. This would enable us to isolate the effect of feelings of threat and the impact of cultural differences between the two areas, with everything else being relatively equal. We expected the higher threat levels in Srinagar, and the presence of separatists in that area, to result in lower levels of support for democracy and political tolerance as compared with Jammu. However, while some of the differences we expected did appear, the most important results from the study were unexpected.

Democratic attitudes in challenging contexts

Open violent conflict, obviously, impinges on the exercise of democratic rights. However, although Jammu and Kashmir has been the scene of interstate wars and widespread internal violence, it should be noted that political violence in the state declined significantly between 2002 and 2007. Since then, up until about 2015, Jammu and Kashmir saw the lowest levels of violence since the conflict escalated in 1989. In 2016, tragically, there was a break in the trend, followed by the death of Burhan Wani, the Hizbul Mujahedin separatist leader. After that the level of violence rose again, and the armed forces fighting the uprising started shooting demonstrators with pellet guns. However, while the conflict has been very serious since then, it is still far from the levels seen in the 1990s or early 2000s. On the other hand, the situation in the state cannot be described as peaceful or normal. Tension, fear, threats, and limits on democratic freedoms create a context which is obviously detrimental to democratic norms, and to political tolerance in particular. Political tolerance merits special attention in this context, since we know from previous research what factors may affect it, and we can test some conclusions from previous studies in Jammu and Kashmir. The context is a period which has been exceptionally challenging for the citizens of this state. Some variation between different areas of the state should be expected with regard to the prevalence of democratic attitudes. In areas where threat levels are higher, and especially where extremist forces are active, political tolerance should be weaker. But are all segments of the population affected the same way? Are there any situations where support for democracy and political tolerance has better chances of survival than in others?

What we do know from previous research on political tolerance is that it works as a pillar for democracy. Politically tolerant persons understand that, in a democracy, the partisan coloration of the government shifts. In some periods, therefore, one must accept that groups and individuals whom one dislikes or with whom one disagrees have the right to hold power, and exercise their democratic rights. Political tolerance is required for reconciliation and peace. Naturally, however, there are limits to political tolerance in a democracy. There is no reason, for example, to show tolerance towards those who are extremely intolerant and who seek to destroy democracy. This is known as ‘the paradox of tolerance’. Again we are aided by Karl Popper, who just after the Second World War described the promotion of tolerance as a basic challenge for democracy (Popper Citation1945a, Citation1945b).

However, it was the American sociologist Samuel Stouffer who first examined public attitudes about tolerance in a systematic way, with his large-scale studies in the US in the 1950s. During those years, American democracy was being tested by fear of communism and resistance to the civil-rights movement. Since Stouffer’s early studies, moreover, seminal work on this topic has been done (Sullivan, Piereson, and Marcus Citation1982), and more recently by Gibson, Gouws, Mondak, and others (Gibson and Gouws Citation2003; Mondak and Sanders Citation2003; Mondak Citation2010). In these studies, two factors have been shown to impact greatly and consistently on levels of political tolerance: levels of education and perceptions of threat. Two factors, in other words, that we can study in the state of Jammu and Kashmir. Here the question is: can educational institutions work to cushion or counteract the impact of harsh conditions?

The threat variable may concern several things – threats to the nation, to one’s group in society, to oneself as an individual. It is important here to make sure that the dependent variables – political tolerance and democratic norms – do not contain ingredients of the independent variables measuring threat. In a conflict situation in particular, it should not be underestimated how difficult it may be to keep them apart. The education variable needs to be treated perhaps even more carefully.

For a long time, scholars treated the relationship between education and political tolerance as rather uncomplicated. The more education, the more political tolerance. Already in the 1980s, however, Frederick Weil argued that the content of the teaching system matters greatly if we want to understand better how education may correlate with political tolerance (Weil Citation1985). If political tolerance is to establish itself, liberal and democratic values need to be taught. From this perspective, it is naturally worrying that the curriculum in India is becoming more biased against groups such as Muslims, and that it is conveying the Hindutva ideology promoted by the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and other still more extreme nationalist organizations (Menon and Rajalakshmi Citation1998; Menon Citation2002; Pathak Citation2015; Doniger Citation2014; Flåten Citation2016). It is far from obvious, however, how all this is to be interpreted. Research by (Nie, Junn, and Stehlik-Barry Citation1996) suggests that education per se is the main factor strengthening democratic norms. According to Finkel, on the other hand, case studies fail to support the contention that civic education is really associated with political tolerance (Finkel Citation2014). (Green et al. Citation2011) argue too that a specific knowledge of civil liberties does not lead automatically to support for them. The nature of the relationship between education, knowledge, and norms is far from settled, evidently. Nevertheless, Lipset’s observation from sixty years ago still seems to hold true as a general statement:

Education presumably broadens men’s outlooks, enables them to understand the need for norms of tolerance, restrains them from adhering to extremist and monistic doctrines, and increases their capacity to make rational electoral choices. (Lipset Citation1959, 79)

We may be able to use more refined and technically sophisticated methods to study causal factors more closely. Failing to keep a certain distance from the empirical material, however, may obscure what we see. Lipset’s observation is important because it captures the broad sense in which education can help make a society more humane and democratic. It prompts us to look at factors beyond the curriculum, for example. To be sure, a curriculum can influence normative values. If it proclaims the dominance of a majority religion and culture over others – i.e. if it promotes an ethnic state (which is the main criticism in several studies of the curriculum in Indian schools) – it will leave little room for tolerance. In neighbouring Pakistan, for example, the curriculum in some cases promotes the practice of jihad, leaving little space for that broadening of outlook held out by (Widmalm Citation2016). Still, the content of school books is not everything. Schools can be ‘schools in democracy’ in other ways as well. One such way is through their praxis – namely how they teach, and in what context. We should therefore look further into how teaching is done and in what context – and more from the perspective of the student.

A more democratic praxis involves a way of teaching which, in terms of communication, is more than just a one-way street. It entails a freer and more intellectual form of interaction with students. It provides for critical reflection and seminar discussions. In such a context, argumentation is central. Arguments are scrutinized and valued according to how well they are supported and how logically they are constructed. There is a greater emphasis on rationality. Less stress is put on who is saying what (Björklund Citation1996). In a sense such an environment is democratic, since it gives equal rights to all to express themselves. An important aspect of a ‘school in democracy’ is orderly discussion, with participants taking turns in debate and waiting for others to finish their argument. In his research on civil-society organizations, Robert Putnam has looked further into this (Putnam and Feldstein Citation2003; Putnam Citation1992). A ‘school in democracy’, we might say, is one based on the idea of deliberation in Habermas’ sense (Habermas Citation1996). When we enter a discussion, we should be prepared to change our position if our opponents present better arguments. Now no school, naturally, can be expected to provide such an environment if basic security is not enjoyed by all taking part. Only if students feel fairly safe can such a school in democracy work. We have thus come full circle, to the factor with which we began: deliberation (which is the factor we found to be declining most sharply in India’s democracy). Can we locate spaces for deliberation in the educational system which may support India’s democratic future?

Comparing Jammu and Srinagar

It is time now to review how respondents described their experience of primary education, how they assessed conditions at the institution of higher learning they were currently attending, how they perceived threats, and finally whether they expressed support for democratic norms and political tolerance. All interview responses have been categorized so as to permit a quantified overview, which we present at the end of this section. First, however, we use excerpts from the interviews to summarize the main results regarding the variables mentioned. We begin with how students described their experience of education.

Students’ experience of primary and higher education

We asked respondents to describe how they experienced primary education, both within the class room and outside it. Students in Jammu told of a quite repressive primary education. Physical punishment seems to have been the order of the day. Most respondents said their teachers were very authoritarian, and that they beat students regularly. One interviewee explained that, ‘whenever we disobeyed them, they gave us punishment and beat with sticks’. Another said that ‘in [school] everything was decided by the teacher and we have to obey always’. It seems there ‘were no discussions’ in class. Several students said they did not feel safe either inside or outside the classroom. We asked specifically what would happen to students who bullied other students, and received answers such as: ‘Teachers generally beat both parties and then settle compromise.’ In several interviews, issues relating to caste identity come up. Bullying students could sometimes be ‘punished, but teachers sometimes themselves make fun of Scheduled Caste (SC) students’. ‘Scheduled caste’ members belong to caste groups that are economically disadvantaged and which have therefore received reservation status. However, their social status tends to remain low (Deshpande and Ramachandran Citation2019).

Some students expressed caste-based resentments: ‘Teachers were like dictators and they also discriminated on the basis of caste. Most of the teachers are of upper caste and they usually don’t treat SC students well. At times, they even beat a lower-caste student more than upper-caste students for the same mistake.’ Not all of the accounts, however, were of violence and punishment: ‘Some teachers were honest and kind also.’ One student said the ‘environment of the school was very friendly and decisions were taken collectively; students were also consulted’. On the other hand, ‘teachers were nice but they were not disciplined’. ‘[A] majority of the teachers arrived late to school and they usually kept talking to each other instead of taking classes.’

The situation in Srinagar was strikingly similar to that in Jammu. Here too several respondents told of how teachers would beat students with sticks. One interviewee claimed that ‘in between the classes, situation was more like submissive and schools more looked like “prisoners” watched by “jailers” in the guise of “teachers”’. And ‘we had punishments in the form of detentions, de-merits for ourselves and our houses, physical punishments included standing for long, frog jumps, running laps and sometimes public shaming was also used by announcing our names in the dining hall. Occasionally, we were supposed to assist our teacher or write lengthy original essays as punishment too.’ With regard to bullying, one student described teachers as being ‘generally of orthodox mentality, they seldom tolerate the disobedience. Those students were beaten up and shamed in front of whole class. But the students were too smart and would get away with it.’ However, there were also some accounts here of a less repressive environment, as when one student claimed that ‘the teachers were good. Good in every way.’ The Srinagar interviews also turned up interesting information about whether respect for other religious groups or political parties was taught. One student said that, ‘to be honest, I was not taught anything about these things’.

To a great extent, the results from our interviews concerning primary education in Jammu and Kashmir are similar to those found in a parallel study in this research project carried out in Pakistan. These results confirm the picture painted by studies on corporal punishment in schools in India – both independent studies (Morrow Citation2015) and those carried out by the government of India (NCPCR Citation2012).

If children are often subjected to physical punishment, this can only be expected to lower their capacities for empathy and political tolerance later in life. That is the effect of threat. Furthermore, needless to say, there were almost no traces in these accounts of any deliberative teaching strategies, such as would lead us to expect higher levels of tolerance later in life. However, previous studies have shown that students in India are subjected to such punishment less and less often as they age (Morrow Citation2015). And at the institutions of higher education they were now attending, our respondents reported, their situation has radically improved in this regard.

In Jammu, there were strong indications that almost all of the students we interviewed enjoyed a free, open, and relaxed situation. One respondent explained that the ‘situation in Government Degree College “X”Footnote4 wasn’t much different from our School but here in university the environment is more open and liberal and there is freedom’. Several accounts suggested that deliberation was practiced, and not only by the teachers: ‘In college, teachers come and deliver lectures and after that we leave for home. But in university we generally sit after classes and discuss various things with our classmates and other friends.’ Deliberation marked both teaching methods and more practical matters: ‘The situation in college as well as in university is very liberal, open, and friendly. There was our say in all types of decisions regarding exam timing etc.’ The open environment seems as well to have helped overcome boundaries based in religious and ethnic identity: ‘In college, teachers were liberal and cooperative and they didn’t discriminate on the basis of caste or religion.’ Divisions could be overcome, at least as long as basic democratic rules were respected: ‘There wasn’t any religious division in our Law School. We all were friends, and respected everyone’s religion. In Law School I even started sharing food with friends of other religion which I never did before. But my friends and I don’t like the fundamentalists.’

We expected to find such attitudes less frequently in Srinagar, due to the serious conflicts which have plagued that area. Yet almost no differences vis-à-vis Jammu could be detected. In Srinagar too, namely, our respondents had seen a dramatic improvement in their situation since their days in primary school: ‘The situation was different here. The teachers did not beat us at all.’ A more liberal climate was described: ‘A bit chaotic at times but still free!’ Notwithstanding the ongoing conflicts in the region, the academic environment was described as ‘smooth in nature; every student was friendly’. Some kind of selection effect might be suspected to be operating here, whereby democratically oriented students in particular seek out a place of higher education like the ones they were attending. However, several students stated clearly that democratic virtues were being taught: ‘We were taught to respect members of other religion from religious institutions. We learnt about respect for political parties through media and in our classes.’ And: ‘Yes, we were always taught to respect every religion, political party etc.’ Here too, moreover, the atmosphere in classes was apparently open: ‘It was congenial and favourable.’ Deliberation was practiced: ‘It was interactive.’ And: ‘The situation in the classroom was also good. The teachers would encourage us to ask questions.’

In sum, we will not be jumping too far ahead if we conclude already now that the situation faced by our respondents had radically improved since their days in primary school. The cases of Jammu and Srinagar show further similarities as well, but also some differences.

From personal to sociotropic threat

Stevens and Vaughan-Williams suggest we place different kinds of threat on a scale, from the personal level up to the national (Stevens and Vaughan-Williams Citation2014). Variations in this matter are not dichotomous. Here, therefore, we summarize how our respondents perceived threat at three levels: personal, group, and national.

Where threat at the personal level was concerned, respondents in Jammu commented less extensively than they did on the educational situation. Most interviewees simply said they felt safe, and that they experienced no immediate threat. One showed concern about the decline in freedom of expression: ‘There is no freedom of expression and right-wing people are a threat to freedom’.Footnote5 Another expressed concern over intra-religious divisions: ‘Yes, some politicians are trying to divide people in our Kargil area on the basis of Shia and Sunni. This trend is really a big threat for our society.’ Another respondent worried about oppression based on caste identity: ‘Caste discrimination is a threat to us in the last few years. Upper-caste people want to take away our reservation which was given to us by Dr. Ambedkar.’ Aside from these cases, however, few students in Jammu spoke of personal threat as a major source of anxiety.

Students in Srinagar showed a greater concern for personal threat than their counterparts in Jammu, although some respondents said it was not a problem in their own case. Those who did say they felt threatened made direct reference to the ongoing conflicts in the area: ‘Yes. I face threat as I am living in a conflict zone. It is a big problem.’ Such a fear could, of course, be related to more general concerns about the security situation in India. Another respondent spoke along similar lines: ‘Yes, I feel there is threat in the society. You never know by whom you will be harmed. We can be the victim of any oppressed organization. It is a very big problem.’ Other interviewees were more explicit about threats relating to religious identity: ‘Being the follower of Islam I feel insecure and threatened.’ Another Muslim student made a similar point, but in more separatist terms: ‘When one is living in an occupied territory and having faith in a religion that is in minority in the country, it is obvious that one will feel threatened. It is a big problem.’

Let us now consider the responses to group-level threat. In Jammu, most interviewees simply stated that they did not feel threatened. Those who did mention threat attributed it to separatists (‘anti-national people are big threat’), to Hindu nationalists (‘the ideology of RSS’), or to caste-related conflicts (‘as we are Dalit, the only threat to us is Brahmanism’). One respondent made more detailed reference to the ongoing conflicts in the region: ‘Yes, first thing is religious division and other one is border conflict with Pakistan. As our area is near LoC and there is always danger of border conflict. Our people suffered a lot in the 1999 war.’

Our respondents in Srinagar put a heavier stress on group-level threat, and their responses on threat at the personal level appeared to display the same pattern. The local conflict is salient at a general level: ‘Kashmiris feel threatened justly. Yes it has been so always. Just the threats have amplified manifold for everyone who calls Kashmir home, irrespective of their religion, political affiliation or ethnic group. An insensitive government has been the worst threat currently.’ Another respondent elaborated on the nature of the threat: ‘Yes, always. We Kashmiris don’t feel safe within our own country; even when we go to any part of the country. Our children are not secure outside. They are usually insecure on the basis of their origin and when dealing with other religious/political/ethnic groups. There is always a threat and the fear of insecurity at the back of our minds. Our parents always live in fear. Even sometimes we hide our identity and religion in order to be safe. There are many events that have happened that made us to think this way.’ Other respondents in the area gave similar accounts.

Where threat at the national level was concerned, differences between Jammu and Srinagar became less discernible again. Students in both areas expressed concern about the matter. Most of the responses in Jammu touched on terrorism, as well as the country’s relationship with China and Pakistan. Caste conflicts, ethnic and religious divides, and consequent clashes between Islamist and Hindu extremists were other objects of worry. Respondents in Srinagar in particular pointed to a general loss of faith in pluralism as the main problem: ‘Yes, because losing faith in the pluralistic fabric of the nation.’ They also cited religious intolerance and communal rioting as major threats.

Clearly, we do find differences between Jammu and Srinagar when it comes to perceptions of personal and group threat. Had patterns such as those described above not appeared, then issues relating to the trustworthiness of the interviews might perhaps be raised. Naturally, perceptions of threat reflected the differing degree to which the two areas have had direct experience with the conflicts in the region. The question now is: how do these differences relate to support for democracy and political tolerance? Theories on political tolerance predict such support will be lower in areas where people feel threatened. Some earlier studies showed that sociotropic threat can do the worst damage to political tolerance. In this regard, however, both Jammu and Srinagar yield unexpected results. We must remember here that it is highly educated students we have interviewed. A larger survey would most likely come up with different results. Our special focus, however, is on students at institutions of higher learning.

Support for democracy and political tolerance

When asked whether members of other religious groups should have the same rights as oneself, a majority of respondents in Jammu simply stated that they should: ‘If they are citizen of our country they should be given all rights that are enjoyed by any other citizen of our country.’ Those who elaborated on this question delivered essentially the same message. In Srinagar this was the main reply. One respondent there explained: ‘Religion cannot be singly an underlying factor in determining citizenship, rights, participation in politics and democracy. No one should be barred from anything because of their religious beliefs.’ Another said similarly that ‘in a pluralistic country like India it is imperative that every religious group be given rights at par with others’. Even those expressing strong dislike for another group took this view: ‘Yes all the parties should be given the same rights. But I dislike the BJP more than the rest of the parties.’

Responses relating to democracy in more general terms were mostly the same in the two areas. We used the following question: ‘What is the best way to run a country? People voting on who should be in power every four or five years, or electing one strong and competent leader who can decide for everyone else until he or she decides to let people vote again for a new leader?’ In Jammu support for democracy was strong: ‘Parliamentary democracy is best form of government, but it needs certain reforms in our country. Our parliament is full of uneducated persons. We need to elect intellectual and educated leaders.’ Some students answered the question with some qualifications, but still expressed strong support for democracy: ‘Democracy is best but criminals should not be allowed to contest and also there should be 50% reservation for women.’

In Srinagar too, support for democracy was very strong. One interviewee quoted Lord Acton: ‘People should vote every five years. Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’ Others responded much as their counterparts in Jammu: ‘The best way to run a country is democracy and elections should be held after every four years and the leaders should be made accountable before the law.’

As they did in the case of questions about the educational system, students from Jammu and Srinagar gave responses that were more similar than different. If we categorize their answers to the various questions, while bearing in mind their longer statements as well, we come up with an overview that looks like this ():

Table 1. Summary of interview results on education, political tolerance, threats, and democracy.

Differences between Jammu and Srinagar were most pronounced regarding perceptions of personal and group-level threat. There were almost no other differences to speak of, notwithstanding our expectation that respondents in the two areas would differ in terms of their support for democracy and political tolerance. Moreover, when asked about challenges facing the world in general, both sets of respondents expressed similar concerns about exploitation, widening economic divides, and unsustainable use of resources. We may thus draw some important conclusions, although we must remember that our sample – consisting of persons from one particular group in society – is a small one.

Conclusions

One of the more vexing dilemmas in tolerance studies is that it is hard to find cases which defy the odds and where support for democracy – and in particular for political tolerance – has managed to grow and even flourish in spite of harsh conditions that we otherwise expect to make democracy fail. The case examined here represents exactly this: it seems there are ‘black swans’ in the state of Jammu and Kashmir in India. Such cases have been observed before, but they are rare. This is also why the case of Jammu and Srinagar is important from a more general perspective. It teaches us something which is hard to find. It makes clear that theories about the relationship between certain variables and democratic attitudes – theories that appear to hold good on a general level – can at least can be challenged. This case says something about how path-dependence produced by socialization early in life can in fact be broken, and how. Many studies on trust, for example, suggest that it results from experiences early in life – but we ought not therefore to conclude that such attitudes are thereafter set in stone and cannot be changed. They can be changed and they sometimes are – even in a pro-democratic and tolerant direction. Finally, the findings of this study also have implications for what policies can be expected to yield the best results in the educational sector in India, and in other countries facing similar challenges. Forces which seek to control higher education for narrow political purposes should observe caution! The findings of this study – especially the unexpected ones – suggest it may better to focus on making conditions in primary education more humane than to meddle with the autonomy of colleges and universities. Let us now review these findings.

Results from Jammu and Kashmir: some expected, most unexpected

Our point of departure in this study was that examining areas with differing threat levels would make it possible to trace the impact of perceptions of threat on levels of support for democratic values in general and political tolerance in particular. As we saw at the outset, previous research in this area has focused mainly on the curriculum and pedagogical content of India’s system of education. In this study, by contrast, we put a stronger emphasis on praxis – namely on how teaching is done, and in what surroundings.

We expected the educational system in Jammu to be favourable to the spread of democratic values and political tolerance. It is true that Hindu nationalists have spread propaganda in the area; and Jammu too has been affected by the violence in the state as a whole. Nevertheless, conditions there have been better than in Srinagar; so stronger support for democracy might be expected. In Srinagar threat levels are higher, separatists are highly active, and there is considerable support even for secession achieved by violent means. We would thus expect support for democratic values and political tolerance to be weaker. Yet these expectations were not confirmed. The case of Jammu and Kashmir provides the kind of unusual circumstances that Popper suggested may be rare, but which in that case are even more important than cases that mainly provide verification.

Instead results in the two areas were quite similar, both as regards students’ recollection of their experiences in primary school and in relation to their assessment of conditions at the institutions they were currently attending. Conditions in primary school were appalling. Most students recalled physical abuse and an authoritarian way of teaching. They also reported differential treatment on the basis of caste and religion. The situation in higher education was the opposite. Students in both Jammu and Srinagar described it as free, relaxed, and conducive to intellectual pursuits. Religious and ethnic identity played but a small role in this teaching environment, and deliberation a great one – both in content and in praxis. Notwithstanding the ongoing conflicts in this part of India at the time, the institutions in question were able to offer a zone of safety where political tolerance could grow.

When we looked at the continuum from personal to sociotropic threat, we found some differences between the two areas. The salient differences – threat perceptions were more palpable in Srinagar than in Jammu – were inextricably tied to the ongoing conflicts in the region, which have hit Srinagar the hardest. Where threat at the national level was concerned, however, the differences mostly disappeared again.

Finally, support for democracy and political tolerance was similar in the two areas. Respondents in both Jammu and Srinagar expressed support for religious and party-political tolerance. They wanted their political opponents to enjoy equal rights, even when they took strong exception to their views. Support for democracy in general was also quite high.

Defying theory and path-dependence

It is interesting in itself, of course, that theories which purport to explain levels of political tolerance fail in certain respects to find support in this study. As we have seen, levels of support for democracy and tolerance were very similar in both Jammu and Srinagar. These results defy the differing conditions in the two areas, and they defy the theoretical importance ascribed to threat in the literature on political tolerance. It was not only in Jammu – where threat was less present than in Srinagar – that support for democracy and political tolerance was strong. It was strong in Srinagar too. Furthermore, while respondents from both areas had experienced dreadful conditions in primary school, this did not prevent them from supporting democracy and political tolerance. Yet specialists on socialization, political tolerance, and social capital commonly contend that such attitudes are formed early in life – at primary-school age, in fact – and that they do not change easily after that. In that way human beings are ‘path-dependent.’ And it is usually harder to go in the one direction – from undemocratic and intolerant to democratic and tolerant – than it is to go in the other. In that sense democratic virtues are fragile. However, the findings presented here show that support for democracy and political tolerance is possible even in very challenging settings.

In this study, we have only been able to find one factor that might explain how harsh life experiences – whether corporal punishment in primary school or perceived threat from the larger environment – can be defied, so that anti-democratic and intolerant views are not the result. As we have seen, the praxis in higher education in Jammu and Srinagar was characterized by openness, relaxed attitudes, and deliberation. It was this common factor that correlated with the similar outcome seen in the two areas. The similarities were far greater than we expected them to be. Of course, one could argue this was an effect of self-selection, whereby democratic and tolerant individuals chose the particular universities that they did because they were already democratic and tolerant. However, many of our respondents said they had learned the practices and values in question at the institutions they were attending.

Policy implications

Previous studies have shown the need to improve the quality of the curriculum in primary education in India, if the emergence of an ethnic state with little space for democratic virtues is to be avoided. This study, like several others we have mentioned, demonstrates the urgency of reforming the country’s primary education system in accordance with more modern ideals. It is time to ban corporal punishment and to encourage dialogue between teachers and students.

The policy implications of our study for India’s system of higher education are less obvious. Surely these institutions may need to modernize as well. However, if the question at hand is whether such institutions promote democratic virtues and encourage inter-ethnic peace, then some of them may not need to be fixed since they may not be broken. Certain institutions of higher education, such as Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, have lately come under criticism for promoting protest and unrest. This has given rise to demands that they be brought under stricter political control. From a democratic perspective, however, student protests may often be a healthy reaction. Many protests have seen students acting together across caste barriers, for social justice on an equal basis. If students are taught or allowed to defend free speech, freedom of thought, and other democratic virtues, then protests by them over controversial issues will be inevitable. It may thus be particularly important in this context not to acquiesce in populist demands for political control of the country’s institutions of higher education. Recent developments at Nalanda University, involving the departure of Amartya Sen, are one example of how political intervention can undermine the autonomy of an institution for higher learning and thwart the prospects for democratic deliberation (Gupta Citation2017). Deliberation has a place in India, and it needs better protection. In some unexpected places it certainly does exist, and it sets a great example for reform.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sten Widmalm

Sten Widmalm, Professor in political science at the Department of Government, Uppsala University in Sweden. He has carried out extensive research on the Kashmir conflict, politics in South Asia, crisis management in the EU, political tolerance, democracy and conflicts in a global comparative perspective.

Notes

1. This article is based on research results yielded by the TOLEDO project at the University of Uppsala. The author is indebted to all interviewees who took part in the study; to the Swedish Research Council, which financed the study; and to the Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi, which helped in the preparations for this study and carried out the interviews. The interviews were conducted professionally and skilfully by the researcher Dinoo Anna Mathew from the Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi, and with indispensable support from Professor George Mathew. In the work of coding the interviews, August Danielsson provided help and support when it was most needed. Thanks also to Ashok Swain at the Department of Peace and Conflict Studies, Uppsala University, the editor of Journal of Peace Education Jeannie Lum, Peter Mayers in Uppsala, and the two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments which improved the quality of the manuscript greatly. As the author of this article, however, I alone am responsible for the analysis, arguments, and conclusions presented herein.

2. Its focus is on ‘constitutionally protected civil liberties, a strong rule of law, an independent judiciary, and effective checks and balances that, together, limit the exercise of executive power’ and ‘the level of electoral democracy’ (Coppedge, Gerring, Knutsen, Lindberg, Skaaning, Teorell, Altman, Bernhard, Cornell, et al. Citation2018; Coppedge et al. Citation2018a; Teorell et al. Citation2018).

3. It would appear that sources like the South Asia Terrorism Portal (SATP) tend to underestimate the number of casualties (Behlendorf, Belur, and Kumar Citation2016). However, they use similar methods for data collection year by year, so the trends shown here should be accurate in their depiction of variations over time. The point of presenting a dual y-axis is not that the line graphs cross each other near 2016. That is simply an artefact of how the scales are constructed. The point is mainly to illustrate two parallel trends: As democracy declines in India, violence in Kashmir increases. And from 2014 on, the situation gets worse than it was earlier – provided we look at trajectories and trends over the last decade.

4. The name has been removed to protect the anonymity of the interviewee.

5. This term – the ‘right-wing people’ – is generally used for supporters of the extreme Hindu nationalists.

References

- Basu, A. 2015. Violent Conjunctures in Democratic India. New York: Cambridge Cambridge University Press.

- Behlendorf, B., J. Belur, and S. Kumar. 2016. “Peering through the Kaleidoscope: Variation and Validity in Data Collection on Terrorist Attacks.” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 39 (7–8): 641–667. doi:10.1080/1057610X.2016.1141004.

- Björklund, S. 1996. “En Författning För Disputationen.” Ph.D., Statsvetenskapliga föreningen, Uppsala Universitet (124).

- Bose, S. 1997. The Challenge in Kashmir. Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C.H. Knutsen, S.I. Lindberg, S.-E. Skaaning, J. Teorell, D. Altman, et al. 2018a. “Varieties of Democracy Codebook.” Varieties of Democracy. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Insititute.

- Coppedge, M., J. Gerring, C.H. Knutsen, S.I. Lindberg, S.-E. Skaaning, J. Teorell, D. Altman, et al. 2018b. V-Dem [country-year/country-date] Dataset V8. edited by, Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Insititute.

- Danesh, H.B. 2007. “The Education for Peace Integrative Curriculum: Concepts, Contents and Efficacy.” Journal of Peace Education 5 (2): 157–173. doi:10.1080/17400200802264396.

- Deshpande, A., and R. Ramachandran. 2019. “Traditional Hierarchies and Affirmative Action in a Globalizing Economy: Evidence from India.” World Development 118: 63–78. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.02.006.

- Dev, A. 1999. “Education for Human Rights and Democracy in Indian Schools.” Human Rights Education in Asian Schools, Vol. 2. https://www.hurights.or.jp/archives/human_rights_education_in_asian_schools/section2/1999/03/education-for-human-rights-and-democracy-in-indian-schools.html

- Dewey, J. 1916. Democracy and Education. New York: Macmillan Company.

- Doniger, W. 2014. “India: Censorship by the Batra Brigade.” The New York Review of Books. Aug 08.

- Duch, R.M., and J.L. Gibson. 1992. ““putting up With” Fascists in Western Europe - A Comparative, Cross-Level Analysis of Political Tolerance.” The Western Political Quarterly 45 (1): 237–273. doi:10.2307/448773.

- Finkel, S.E. 2014. “The Impact of Civic Education Programmes in Developing Democracies.” Public Administration and Development 34 (3): 169–181. doi:10.1002/pad.1678.

- Flåten, L.T. 2016. Hindu Nationalism, History and Identity in India: Narrating a Hindu past under the BJP Routledge Studies in South Asian History. New York: Routledge.

- Ganguly, S. 1997. The Crisis in Kashmir. Cambridge: Woodrow Wilson Center Press and Cambridge University Press.

- Gibson, J., and A. Gouws. 2003. Overcoming Intolerance in South Africa: Experiments in Democratic Persuasion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Gibson, J.L. 1989. “The Policy Consequences of Political Intolerance: Political Repression during the Vietnam War Era.” Journal of Politics 51 (1): 24. doi:10.2307/2131607.

- Gibson, J.L. 2005. “On the Nature of Tolerance: Dichotomous or Continuous?” Political Behavior 27 (4): 313–323. doi:10.1007/s11109-005-3764-3.

- Green, D.P., P.M. Aronow, D.E. Bergan, P. Greene, C. Paris, and B.I. Weinberger. 2011. “Does Knowledge of Constitutional Principles Increase Support for Civil Liberties? Results from a Randomized Field Experiment.” Journal of Politics 73 (2): 463–476. doi:10.1017/s0022381611000107.

- Gupta, M. 2017. “Nalanda University a Textbook Case of How Not to Build World-Class Universities.” The Wire, November 6. https://thewire.in/194688/nalanda-university-textbook-case-not-build-world-class-universities/

- Habermas, J. 1996. Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Hamza, K. 2003. “Saffronizing History Textbooks.” The Milli Gazette, January 29.

- Harbe, C., and N. Sakade. 2009. “Schooling for Violence and Peace: How Does Peace Education Differ from ‘normal’ Schooling?” Journal of Peace Education 6 (2): 171–187. doi:10.1080/17400200903086599.

- Harris, I.M. 2004. “Peace Education Theory.” Peace Education Theory 1 (1): 5–20. doi:10.1080/1740020032000178276.

- Lipset, S.M. 1959. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy - Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” The American Political Science Review 53 (1): 69–105. doi:10.2307/1951731.

- Lipset, S.M. 1981. Political Man. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- MacKuen, M., J. Wolak, L. Keele, and G.E. Marcus. 2010. “Civic Engagements: Resolute Partisanship or Reflective Deliberation.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (2): 440–458. doi:10.1111/ajps.2010.54.issue-2.

- Marcus, G.E. 1995. With Malice toward Some: How People Make Civil Liberties Judgments (cambridge Studies in Political Psychology and Public Opinion, 288. Vol. xiii. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Menon, P. 2002. “Mis-oriented Textbooks.” Frontline 19: 17. Chennai: The Hindu Group, August 17-30. https://frontline.thehindu.com/static/html/fl1917/19170430.htm

- Menon, P., and T.K. Rajalakshmi. 1998. “Doctoring Textbooks.” Frontline, November 7-20.

- Mondak, J.J. 2010. Personality and The Foundation of Political Behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mondak, J.J., and S.S. Mitchell. 2003. “Tolerance and Intolerance, 1976–1998.” American Journal of Political Science 47 (3): 492–502.

- Morrow, V. 2015. “Beatings for Asking for Help: Corporal Punishment in India’s Schools.” The Guardian, May 22. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development-professionals-network/2015/may/22/tough-boys-and-docile-girls-corporal-punishment-in-indias-schools

- Mukherjee, A., M. Mukherjee, and S. Mukherjee. 2008. RSS, School Texts and the Murder of Mhatma Gandhi. Los Angeles: Sage.

- NCPCR. 2012. Guidelines for Eliminating Corporal Punishment in Schools. India: National Commission for Protection of Child Rights (NCPCR).

- Nie, N.H., J. Junn, and K. Stehlik-Barry. 1996. Education and Democratic Citizenship in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pathak, V. 2015. “Hindutva Activist’s National Education Policy Readied for Govt.” Hindustan Times, Aug 16. Accessed 2015-05-21. http://www.hindustantimes.com/higherstudies/hindutva-activist-s-national-education-policy-readied-for-govt/article1-1347991.aspx

- Pemstein, D., K.L. Marquardt, T. Eitan, W. Yi-ting, K. Joshua and M. Farhad. 2018. “The V-Dem Measurement Model: Latent Variable Analysis for Cross-National and Cross-Temporal Expert-Coded Data.” V-Dem Working Paper 2018, 21. SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3167764 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3167764

- Popper, K.R. 1945a. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Vol. 1. London: Routledge.

- Popper, K.R. 1945b. The Open Society and Its Enemies. Vol. 2. London: Routledge.

- Popper, K.R. 2005 [1935]. The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Routledge: London and New York.

- Putnam, R.D. 1992. Making Democracy Work - Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, R.D., and L.M. Feldstein. 2003. Better Together. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Salomon, G. 2004. “Comment: What Is Peace Education?” Journal of Peace Education 1 (1): 123–127. doi:10.1080/1740020032000178348.

- South Asia Terrorism Portal. 2018. “Fatalities in Terrorist Violence 1988-2018.” In South Asia Terrorism Portal. edited by South Asia Terrorism Portal. New Delhi: The Institute for Conflict Management. https://www.satp.org/datasheet-terrorist-attack/fatalities/india-jammukashmir

- Stevens, D., and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2014. “Citizens and Security Threats: Issues, Perceptions and Consequences beyond the National Frame.” British Journal of Political Science 46 (1): 149–175. doi:10.1017/S0007123414000143.

- Stouffer, S.A. 1963. Communism, Conformity, and Civil Liberties - A Cross-section of the Nation Speaks Its Mind. Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith.

- Sullivan, J.L., J. Piereson, and G.E. Marcus. 1982. Political Tolerance and American Democracy. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

- Teorell, J., M. Coppedge, S. Lindberg, and S.-E. Skaaning. 2018. “Measuring Polyarchy across the Globe, 1900–2017.” Studies in Comparative International Development 1–25. doi:10.1007/s12116-018-9268-z.

- Varities of Democracy. 2018. Democracy for All? - V-Dem Annual Democracy Report 2018. Gothenburg: Gothenburg University, Varities of Democracy Institute.

- Weil, F.D. 1985. “The Variable Effects of Education on Liberal Attitudes: A Comparative- Historical Analysis of Anti-Semitism Using Public Opinion Survey Data.” American Sociological Review 50 (4): 458–474. doi:10.2307/2095433.

- Widmalm, S. 2006. Kashmir in Comparative Perspective - Democracy and Violent Separatism in India. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Widmalm, S. 2016. Political Tolerance in the Global South - Images from India, Pakistan and Uganda. London: Routledge.

- Wirsing, R.G. 1994. India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute. Allahabad: Rupa & Co.