ABSTRACT

In post-conflict societies marked by strong negative stereotypes or delicate and sometimes unstable political contexts, teaching both knowledge and understanding of conflicting historical narratives has become a matter of educational urgency. Conversely, a framework for effective teacher training that prepares teachers to activate and facilitate the exchange of multiple perspectives has yet to be identified. This qualitative and exploratory research aims to answer the questions, what boundaries do expert teacher trainers believe that teachers in post-conflict societies encounter when brokering multiple perspectives in the classroom? Which teaching or training methods can teacher trainers use to help teachers reduce the impact of these boundaries? To advance the use of multiperspectivity in post-conflict history education and enhance history-teacher training design. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with twelve experts in history-teacher training to answer these questions. The expert’s statements were openly and axially coded using Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems Theory as an analytical lens. Identifying ten personal or environmental boundaries to brokering multiperspectivity in the classroom, and two training approaches to help teachers establish continuity between their multiperspectivity training and day-to-day teaching practices. Further providing actionable recommendations for educators, non-governmental organizations, and educational scientists.

Following a series of highly publicized incidents of violence, which increased social polarization across Europe, public concern for social order has called for new history education objectives (Council of Europe [CoE] Citation2015, Citation2016). This is especially salient in societies recovering from conflicts characterized by strong negative stereotypes, victimization, powerful and polarized emotions, or delicate and sometimes unstable political contexts (CoE Citation2011; du Toit Citation2020; Kuppens and Langer Citation2016; Psaltis, Carretero, and Čehajić-Clancy Citation2017). Under these conditions, teaching both knowledge of and understanding for multiple histories has become a matter of educational urgency and a prerequisite for fostering inclusive and effective learning environments (CoE Citation2015; Corredor, Emma Wills-Obregon, and Asensio-Brouard Citation2018; Paulson Citation2015; Van der Leeuw-roord Citation2001; Zembylas and Loukaidis Citation2021). Consequently, both governmental and nongovernmental organizations are investing in education for democratic citizenship, emphasizing the development of democratic values, attitudes, skills, and knowledge to establish mutual understanding and overcome local challenges to learning and transfer (Brett et al. Citation2009; Council of Europe [CoE] Citation2011, Citation2015, Citation2016, Citation2019; Harris Citation2004).

As a result of these new educational aims, a multiperspective approach to history education has gained importance in recent teacher training, research, literature, and educational reform (Wansink et al. Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020; McCully Citation2012; Stradling Citation2003). Multiperspectivity is the process, strategy, or predisposition of looking at a situation from different points of view (Stradling Citation2003). It has proven to be an effective approach to learning and teaching when addressing post-conflict resolution and understanding (McCully Citation2012), controversial issues (Tsafrir and Savenije Citation2018; King Citation2009; Nygren et al. Citation2017), intercultural understanding (Goldberg and Ron Citation2014; Stradling Citation2003), and the development of democratic citizenship (Brett et al. Citation2009). However, as signaled by the authors in a previous study (Wansink et al. Citation2018), there is little research on the operationalization of multiperspectivity despite its increasing emphasis over the past 25 years. Moreover, there is a significant theory–practice gap between history-teacher training and that which is necessary to effectively prepare teachers to activate and facilitate the exchange of multiple perspectives, as exemplified by the findings of King (Citation2009) and Zembylas and Kambani (Citation2012), which have demonstrated that teachers are met with significant intellectual and emotional barriers while developing multi-perspective practices.

Therefore, the aim of this article is to contribute to the operationalization of multiperspectivity in post-conflict history education by identifying the challenges to activating multiperspectivity within post-conflict systems and the pedagogical methods that expert teacher trainers use to overcome these challenges. A novel approach is taken in this research by applying an ecological systems theory (EST) framework to describe and investigate teachers’ systems for development (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979) in order to illustrate the personal and environmental challenges to activating multiperspectivity in the classroom and to identify effective methods for establishing continuity between and across teachers’ multiperspectivity training and day-to-day teaching practices. This will further contribute to the literature on history teacher training in post-conflict societies and on practice in terms of design development for effective teacher training programs.

Multiperspectivity

Multiperspectivity in history education requires acknowledging that multiple coexisting perspectives can surround a ‘historical object’ (e.g. an event, phenomenon, figure), and it is rooted in the epistemological understanding that history is subjective and cannot be viewed objectively (Wansink et al. Citation2016; Wansink et al. Citation2018; Grever and Adriaansen Citation2019). Each perspective on the past is informed by the vantage point of the actor and colored by their locally and historically informed prejudices and biases (Stradling Citation2003). Multiperspectivity is embedded within historical methods as it is not uncommon for multiple sources to exist on the same historical object, which can lead to conflicting historical narratives that have to be evaluated and tested against evidence to determine their validity (Low-Beer Citation1997). Furthermore, this multiplicity of narratives can be considered across several different dimensions, such as a temporal dimension where historical objects are studied from the perspectives of that time, throughout the past, or in the present (Wansink et al. Citation2018). Alternatively, multiple narratives may exist because of moral or socio-cultural differences, where actors from the same time period hold varied or opposing perspectives (i.e. in- or out-group perspectives).

In this article, multiperspectivity refers to a critical and interpretational approach to history and is activated in post-conflict societies to address local historical controversies or tensions amongst in- and out-group perspectives. In-group perspectives are ‘societal beliefs that provide shared memories, emotions and understandings of the conflict’ (Çelebi et al. Citation2014, 65), while out-group perspectives are those beliefs that are not accepted or are discouraged by the majority. As a result of this duality, a schism is introduced in intergroup dynamics and may impede post-conflict peacebuilding or reconciliation. Previous research has recognized the important role of history education in bridging such contested pasts; however, this article examines the role of the educator in such a process, particularly how the preconditions for critically engaging with multiple perspectives can be met in spite of the cognitive, emotional, and environmental demands faced by the teacher when teaching and learning about contested histories from multiple perspectives (Maia and Levy Citation2019; Zembylas and Loukaidis Citation2021). The first precondition being a willingness to accept that there are ways of viewing the world other than one’s own that are equally valid, and the second is a willingness to put oneself in someone else’s shoes and try to see the world as they see it (Gehlbach Citation2004). Both of these preconditions have been shown to pose significant challenges for both educators and students (Goldberg and Ron Citation2014; King Citation2009), especially so in post-conflict societies where teachers or students may already strongly identify with the historical narrative of their own group or may want to censor narratives that pose a threat to that of their group (Conrad Citation2020; Goldberg Citation2017).

Post-conflict system for teacher training

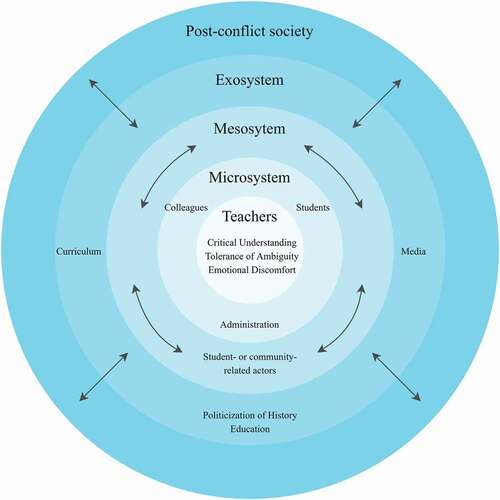

Recent literature on multiperspectivity and post-conflict-related education has highlighted that teachers in post-conflict societies actively experience personal and environmental challenges while developing or using their multiperspective teaching practices (Clarke-Habibi Citation2018; King Citation2009; McCully Citation2012; McCully and Reilly Citation2017). This is, in part, due to the characteristics of post-conflict societies, namely those that are inherently hostile towards recognizing and valuing multiple perspectives, such as in- and out-group thinking, strong and active negative stereotyping, powerful and polarized emotions, delicate and sometimes unstable political contexts, or experiences of violent conflict and social contention (Council of Europe [CoE] Citation2011; Zembylas Citation2017). To examine the relationship between a teacher’s post-conflict environment for development and their capacity to activate multiperspectivity in the classroom, this study applies Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) Ecological Systems Theory (EST) as a framework for analysis. Bronfenbrenner posits that a learner’s (teacher’s) development and socialization follow three assumptions. First, teachers are active players in their environment and exert an influence. Secondly, teachers’ environments can pressure them to adapt to their conditions and restrictions. Lastly, environments consist of different size entities that are reciprocal in nature and placed one inside another (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Härkönen Citation2007). These assumptions provide this study with a foundation for investigating the role of the teacher in brokering multiperspectivity by mapping how each entity within a teacher’s environment can promote or constrain a teacher’s willingness or capacity to use multiperspectivity.

The innermost level of a teacher’s system, or the teacher level, consists of the teachers themselves and characteristics like sex, ethnicity, age, and cognition. Secondly, surrounding the teacher level, the microsystem consists of the groups or institutions that directly impact the teachers’ pattern of activities, roles, or interpersonal relations (Härkönen Citation2007). Thirdly, the mesosystem is comprised of a system of microsystems or the links and connections between two or more settings. Fourthly, the exosystem involves the ties between two or more settings, where at least one of the settings does not ordinarily involve the teacher, but changes made to this setting influence the teacher (e.g. the relations between the school and the neighborhood group; Bronfenbrenner Citation1979). Finally, the macrosystem consists of the ‘developmentally-instigative belief systems, resources, hazards, lifestyles, opportunity structures, life course options, and patterns of social interchange that are embedded in each of these systems’ (Härkönen Citation2007, 12). By examining each of these distinct levels, this study can identify both personal (cognitive and emotional) and environmental limitations to activating multiperspectivity to better understand how to advance the operationalization of multiperspectivity in post-conflict history education and local classrooms.

Broker of multiperspectivity

Considering the known and yet-to-be-known teacher level and environmental boundaries to multiperspective history education, this article further examines how teacher training courses can be designed to mitigate such obstacles and support teachers’ use of multiperspectivity in the classroom. Henceforth, the personal, environmental, or systemic limitations to activating multiperspectivity in the post-conflict classroom will be referred to as boundaries. Boundaries are characterized by their ability to incite discontinuity in teachers’ actions, interactions, and learning (Akkerman and Bakker Citation2011), such as differences between teachers’ day-to-day teaching practices and those considered to be multiperspective. Differences may emerge from teachers’ current cognitive knowledge, understanding, and pedagogical approaches, or any socio-ecological or socio-cultural differences within the teachers’ larger environment (e.g. a nation’s attitude or approach to education). It is important to acknowledge that these boundaries may not be equally salient among all teachers within a group. Considering the boundaries’ impact on multiperspective learning and teaching, there is an urgent need for effective teacher trainings that identify and target these boundaries and provide teachers with tools and strategies to minimize their effect.

Such trainings are aimed at producing brokers of multiperspectivity, which are teachers competent in using opposing perspectives on contested histories to stimulate learning and critical thinking and to foster cooperation and mutual understanding. These brokers promote supportive spaces within which one can transition across and simultaneously connect with varying narratives, contexts, or cultures, further mediating collaboration and cohesion between different practices and perspectives (Bakker and Akkerman Citation2019). Within teacher trainings, trainers act as brokers and equip teachers with the pedagogical methods necessary to mediate cohesion between their day-to-day teaching practices and those considered to be multiperspective. For instance, the literature related to post-conflict history education has prioritized historical methods like discussion, debate, role-playing, questioning and answering, practical exercises, storytelling, and reflection to build the learners’ capacity to accommodate multiple coexisting perspectives and promote critical thinking (Ahonen Citation2014; Brett et al. Citation2009; Council of Europe [CoE] Citation2015; McCully Citation2012; Oulton et al. Citation2004; Parker Citation2016), which can be used by history teachers in post-conflict societies to confidently employ multiperspectivity and attempt to neutralize history education that is politically charged, thereby reduce the impact of polarizing boundaries on learning (Psaltis, Carretero, and Čehajić-Clancy Citation2017).

Research questions

At this point, multiperspectivity, ecological systems theory, and brokers of multiperspectivity have been defined and discussed. The preliminary levels of a teacher’s environment that influence their activation of multiperspectivity have been outlined, and it is expected that these levels are true for teachers of all types of conflict. However, there is little research concerning teachers’ development systems and effective training designs for multiperspectivity use. Bearing this consideration in mind, the research questions are

What boundaries do expert teacher trainers believe that teachers in post-conflict societies encounter when brokering multiple perspectives in the classroom?

Which teaching or training methods can teacher trainers use to help teachers reduce the impact of these boundaries?

Methodology

An exploratory qualitative research approach was taken to address this area of concern. Semi-structured interviews with open-ended questions were used to elicit experts’ detailed experiential information, as this approach is broad-ranging, purposive, and systematic and offers a design that maximizes the discovery of generalizations (Mason et al Citation2009).

Sampling

The intended participant population was 12–15 participants, which was selected in congruence with Guest, Bunce, and Johnson’s (Citation2006) evidence-based recommendations for nonprobabilistic sample sizes for interviews. Sixteen experts associated with the European Association of History Educators (EuroClio) were purposefully selected and invited to participate in the study. They were selected for their extensive experience in teaching history, teacher training, educational consulting, policy development, academic research, and institutional leadership as well as for their association with EuroClio, which has been a leader in international professional development for 25 years and acts as an intermediary between the history educator associations across Europe and several intergovernmental organizations (i.e. the Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, European Commission, and the United Nations; European Association of History Educators [EuroClio], Citation2020). The experts were contacted by means of an email, which included an information letter and consent form.

Participants

In total, thirteen experts were interviewed between 18 February 2020 and 9 April 2020. Twelve experts’ transcripts were member checked and used for analysis. The participants’ characteristics are shown in . Six females and six males between the ages of 38–80 were interviewed, with an average age of 60.0. The experts were qualified for this study based on their distinct and extensive experiences with post-conflict education (), including, but not limited to, teacher training courses or teaching-related initiatives in the Balkans, Baltic states, Caucuses, Middle East, South Africa, and South Korea.

Table 1. Demographics of participants

Procedure and data collection

Most interviews were conducted via Skype or FaceTime and lasted 1–2 hours. The interviews were conducted online due to the COVID-19 pandemic and because the experts were located across Europe, North America, and the Middle East. One interview, the pilot interview, was conducted in person.

The experts were informed of the structure of the interview: demographic questions, questions related to defining multiperspectivity and its challenges in history education, and an open-ended session where experts were asked to design a hypothetical three-day teacher training in a post-conflict society. The third part of the interview was structured around a vignette, which was suggested to elicit more nuanced, valid, and reliable measures of participants’ opinions than abstract, open-ended opinion questions (Alexander and Jay Becker Citation1978; Jenkins et al. Citation2010).

Analysis

To answer the research questions, the recorded audio was transcribed and sent back to the participants for confirmation to increase validity and provide participants with a second opportunity to engage with or add to their interview data (Birt et al. Citation2016). Following this, the experts’ statements were coded and synthesized in the program NVivo 12. First, all relevant statements were segmented according to two predetermined concepts: post-conflict boundaries and pedagogical methods. Then, to answer the first research question, the experts’ statements regarding post-conflict boundaries were categorized by system level: teacher, microsystem, mesosystem, and exosystem, using Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) EST as an analytical lens. These statements were then axially coded to gain an understanding of the different boundaries (i.e. emotional discomfort).

To answer the second research question, a similar process was followed, using the statements related to pedagogical methods. The statements were first categorized according to Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) system levels, then openly coded according to sensitizing concepts derived from the pedagogical methods discussed most prominently in the literature on multiperspectivity and post-conflict history education: discussion, resource-based exercises, inquiry-based learning, project-based learning (Bowen Citation2006; Brett et al. Citation2009; Council of Europe [CoE] Citation2015; Oulton et al. Citation2004; Parker Citation2016; Stradling Citation2003). The authors kept a detailed description of this process and conducted an audit trail to increase confirmability and trustworthiness (Carcary Citation2009).

Results

According to the research questions, the results of this study will be divided into two sections: boundaries to activating multiperspectivity in post-conflict systems and pedagogical methods for activating multiperspectivity in post-conflict systems.

Boundaries to activating multiperspectivity in post-conflict systems

During the interviews, participants were asked, ‘are there challenges to getting teachers to engage in multiperspectivity in history education? If so, what are they?’ This provided the researchers with insight into a variety of boundaries to activating multiperspectivity: critical understanding, tolerance of ambiguity, emotional discomfort, students, school-related actors, student-related actors, community-related actors, mass media, national curricula, and the politicization of history education. These boundaries were organized in terms of Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) EST and are represented in below. For further discussion of these boundaries and their frequency counts, see the following sections below.

Teacher level

All twelve experts identified boundaries at the teacher level, naming at least one of the three concepts: emotional discomfort, critical understanding of knowledge construction, and tolerance of ambiguity (). These boundaries are similar with respect to their negative impact on a teacher’s ability, intention, or willingness to engage with multiple perspectives, which thereby hampers their capacity to become a broker of multiperspectivity in the classroom. All twelve experts discussed emotional discomfort, describing it as the degree to which teachers cope or identify with their in- or out-group transgenerational trauma or collective memory. As teachers’ emotional investment in the conflict or conflict-related suffering rises, it reduces their willingness to engage with or present multiple narratives. For example, Mary stated,

The challenge is having people in your training that aren’t really there yet, or who are really focused on their own points of view and not being able to step outside … [they are] very invested in their own trauma, very invested in that trauma of their own tribe or self-identified group. That’s really, really challenging.

Beyond teachers’ emotional comfort with multiple perspectives, eleven experts identified a cognition-related boundary, critical understanding. This boundary refers to the content knowledge and disciplinary skills necessary to critically evaluate how knowledge and historical narratives are constructed. Without critical understanding, a teacher may lack the tools to recognize or gain insight into other relevant perspectives or communicate and support the epistemological belief that history is interpretational and that multiple narratives can coexist, further emphasizing that one’s investment in a single cognitive or emotional truth can limit one’s capacity to broker multiple perspectives. For instance, Mary continued by saying

They’ve [teachers] got some very specific experiences which will predispose them to certain points of view; they’re not good or bad, they just are, right? It might make them more or less able to do multiperspectivity if they’re highly invested in a certain political point of view.

Lastly, eleven experts described teachers’ lack of tolerance of ambiguity, which refers to one’s attitude or disposition towards uncertainty (e.g. welcomed, treated as a threat), as a potential boundary. More specifically, this involves teachers’ mental and emotional reactions to being confronted with uncertainty surrounding a contested historical object. Tolerance of ambiguity has been described as critical to one’s ability to accept and support that a consensus may not be reached regarding a particular historical topic, suggesting that those who demonstrate tolerance of ambiguity are indicating a preliminary understanding of the provisional nature of history and knowledge construction. Thus, without such tolerance, teachers may be reluctant to develop their critical understanding because of a cognitive or emotional block to problematizing one’s own perspectives or engaging with diverse perspectives. Leonor highlighted this concept, saying that

[Teachers] need to understand and respect that the others have opinions that are different from yours [theirs]. Built on knowledge that is different from yours [theirs]. Let’s share this knowledge, let’s see if we can bridge anything, but we need to understand that it is okay to be different and accept this.

Microsystem

The experts identified two distinct boundaries at the microsystem level, school-related actors and students (). Five experts addressed the first, which involves active resistance to multiperspectivity from school-related actors (i.e. school administrators or fellow teachers), particularly when school-related actors view multiperspective teaching practices as a threat to the status quo and they use their influence within the school to reduce the teachers’ ability to broker multiperspectivity in the classroom. The experts described reasons such as wanting to avoid new requirements in an already overcrowded curriculum, reducing threats to teachers’ routinized teaching practices, or a fear of attracting negative attention from the community or media. Fatima noted this by saying, ‘The school principal, the school guidelines, [or] the curriculum does not really allow for that [multiperspectivity]. So, the teacher would be taking a step forward and this needs courage’.

Also, at the microsystem level, eleven experts named students as a source of resistance to teachers’ use of multiperspectivity in the classroom. Drawing similarities to the teacher-level boundaries concerning how students perceive multiperspectivity because of their socialization and how past educational experiences may limit their cognitive and emotional capacity to cope with multiple perspectives, further curtailing both parties’ willingness to engage with multiple perspectives in the classroom. For instance, regarding students’ emotional capacity to cope with perspectives that diverge from their own or those of their communities, Nathanial stated,

… rationality would only take you so far; and that there is an emotional involvement in this … which in young people can be quite predominant. Particularly if in a post-conflict situation [where] they’re coming up against what their family, or what the media, or what their peers believe …. I’m exaggerating, but we can’t put young children in a position where they either have to believe the teacher or their parents.

Students may resist teachers’ efforts to activate multiperspectivity in the classroom to reduce threats to their sense of self and authority. Additionally, students may lack the disciplinary skills necessary to critically evaluate contested historical perspectives (e.g. critically evaluating opposing sources before formulating conclusions or determining reliability) due to past educational experiences that emphasized a single historical truth or limitations within the national curricula. Which are inherently incompatible with the goals of using multiperspectivity to address local historical controversies or tensions amongst in- and out-group perspectives:

So, you’ll have to differentiate information from opinion; and this is big for students, it’s not that easy. If you have the name of a historian, you think that whatever this historian is writing or stating is correct. It means that he makes all these statements based on some evidence, and you’ve [students] got to understand all these mechanisms. [Leonor]

Mesosystem

The experts identified student- and community-related actors as a source of resistance at the mesosystem level on account of their influence and power over actors within the microsystem (). For instance, seven experts drew attention to the impact of student-related actors (i.e. parents) on students’ or administrators’ perceptions of or attitudes towards multiperspectivity, who in turn can directly empower or limit a teacher’s ability to activate multiperspectivity in the classroom. William stated,

We have heard the examples of parents or grandparents coming to the school complaining that they [students] just learned another way of thinking about this truth that must be a truth; a teacher shouldn’t do that, and if they don’t stop that they would want them to be sacked.

Additionally, three experts named community-related actors as a driving force against multiperspectivity in the school context. For example, actors from socially valuable organizations (e.g. veteran’s associations or religious institutions) use their societal power to influence or intimidate school-related actors and control the nature, quality, and quantity of historical narratives taught in schools. As suggested by Leonor, these actors can sway the public’s perceptions of multiperspectivity or a particular narrative and completely halt the brokering of multiple perspectives in the classroom

For instance, in [post-conflict region], you have the veteran’s association of the war. You publish a nice history manual that offers different perspectives to recent past events—which are of course linked to the conflict—and then the association of veterans says, “no, no, no, this is not good”. They have a voice in newspapers, and then there’s a big scandal because this teacher or this group of teachers published this book.

Exosystem

Three society-wide mechanisms were identified by the experts as key systems for constricting multiperspectivity: state’s politicization of history education, media, and national curricula (), each distinct for its ability to suppress multiperspectivity and reinforce the boundaries at the lower levels of a teacher’s environment. In terms of the state’s politicization of history education, all twelve experts spoke of intentional state-organized political maneuvering of post-conflict history education for the purposes of reinforcing and advancing the in-group narrative or censoring political and historical memories. For instance, Marija commented,

I would say that the political elites are using different occasions to pass on the stories of one group. They use the textbooks, they use the commemorations, they use memorials, they use different kinds of associations that came out from [the conflict], who have their own agenda to transmit one story.

Seven experts identified mass media as a mechanism for rallying resistance to multiperspectivity in post-conflict history education, commenting on the media’s ability to prevent teachers from developing a willingness or intention to activate multiperspectivity by vilifying those that have made progress in brokering multiple perspectives. Anna stated,

I remember that we worked in absolute silence in [post-conflict region] because we knew if the press got hold of this … then we wouldn’t be able to work further. There would be so much pressure on the people who dare to come together with their colleagues, which were seen by the press as enemies and bad guys.

Lastly, ten experts discussed national curricula as a vehicle for significantly undermining a teacher’s ability to activate multiple perspectives in the classroom, for example, curricula with prescribed end goals that are topical and factual, being confined to single narrative textbooks or sources, or overloaded in terms of content and time. These are just some examples of how a curriculum can be incompatible with the interpretational and provisional nature of multiperspectivity or how it would require substantial time and resources for teachers to identify methods that accommodate both the national curriculum and multiperspective practices, further heightening teachers’ and administrators’ resistance to multiperspectivity. Daan commented on this, saying that ‘Teachers don’t have that much time and may feel uncertain about introducing something that undermines their own authority. Maybe you do multiperspectivity on Wednesday, but on Friday you want to explain exactly what happened [for the exam]’.

Pedagogical methods for activating multiperspectivity in post-conflict systems

To answer the second research question – which teaching or training methods can teacher trainers use to help teachers reduce the impact of these boundaries? – the following sections examine the five most frequently mentioned training and pedagogical methods to circumvent the above-mentioned boundaries: project-based learning (PjBL), inquiry-based learning (IBL), discussion, resource-based exercises, and reflection. The aforementioned group of methods is not mutually exclusive; in fact, the experts also discussed the advantages of techniques like debating, establishing a support network or follow-up activities, informal opportunities to socialize, lectures, role-playing, site visits or field trips, and employing local trainers, which are all supported by recent literature (Brett et al. Citation2009; Council of Europe [CoE] Citation2015; McCully Citation2012; Oulton et al. Citation2004; Parker Citation2016). These five methods were selected for their prominence in the data and will be discussed in terms of their versatility and use in overcoming boundaries at varying levels of the teachers’ environment.

Training approaches

The experts were asked to describe an ideal three-day teacher training on multiperspectivity. In response to this, the experts described two overarching training approaches: project-based learning (PjBL) or inquiry-based learning (IBL). Eight experts described a training based on PjBL, a multiday program during which teachers work individually and in groups to draw conclusions (e.g. teaching philosophy) or produce a tangible product (e.g. lesson plan, source collection) that aids them in overcoming real-world problems (e.g. the boundaries in their system). Six experts focused this approach at the teacher level, saying that they would ask teachers to exchange their lived experiences as a resource to identify and compensate for any blind spots in their own perspectives or as a source to be used in a lesson plan or learning activity. Coupling PjBL with trust and team-building exercises provides a safe space for teachers to address their own emotional discomfort, willingness to critically evaluate their own perspectives, and tolerance of ambiguity. The resulting co-produced conclusion or product that represents multiperspective collaboration empowers the teachers with a sense of ownership in multiperspective practices and serves as a reference for recreating such learning in their own classrooms. Fatima emphasized this process

They chose the topic, and their task would be to develop an activity to build students’ capacity to understand perspectives … So, when they plan this activity together, they get ownership of the work, and there is more chance for them to go back home to their schools and do it.

Seven experts addressed PjBL at the microsystem and exosystem levels, describing it as an effective method for curbing the impact of a lack of multiperspective resources, restrictive curricula, or colleagues’ resistance to investing in more multiperspective practices. The co-produced conclusion or product can be used to completely overcome the boundary (e.g. a new source collection to replace a single narrative textbook) or build teachers’ capacity to confront future boundaries through practice with the project’s end product (e.g. change agent training, writing policy proposals, revising curricula, action planning). For example, Simon discussed leveraging his project’s product (i.e. ready-to-use unit lesson plans) as a method for confronting such boundaries: ‘You know that they will go home and talk to other teachers and offer other teachers the off-the-peg item, which can be edited, refined, or developed. So, the idea spreads as well’.

The second training approach, inquiry-based learning, was mentioned by eight experts and entails structuring the training around a central point of inquiry or a process of problematizing various boundaries, such as one’s perspectives or historical understanding, the disciplinary concepts truth or fact, a socially accepted myth or political claim, curriculum objective, etc. However, unlike PjBL where there is a leverageable end product that can be used to reduce the salience of the boundary, IBL was described as an open-ended program that focuses on teachers gaining a deeper understanding of how they interact with and react to various boundaries so that they can routinize a procedure for identifying boundaries and strategizing around or against them to advance their brokering of multiperspectivity in the classroom. Fatima emphasized the importance of inquiry-based approaches by explaining how regular inquiry can help learners cope with both the complexities of daily life in post-conflict societies and multiperspective teaching and learning:

We need to … breathe, think, and try to see what made that conflict? What are the different perspectives? Why did the conflict happen, and how can we deal with it? How can we now contain it? Move forward? Deal with it? How can we learn to do this in our daily life if we don’t do that kind of thinking, if we don’t learn this type of thinking when studying the past.

At the teacher level, eight experts employed this approach to raise awareness of critical understanding of knowledge construction. Through guided inquiry, the learners (teachers or students) examine disciplinary concepts like multiperspectivity or a fact through multiple lenses to normalize questioning one’s historical perspective or given evidence, thereby reducing the impact of the boundary and tolerance of ambiguity. Fatima and Oliver emphasized this in the following quotes

This approach is about helping kids to understand the provisional nature of historical knowledge and that it is legitimate to interpret history in different ways, providing you can justify that by the evidence available. [Oliver]

I would call it historical methods; to address a topic [with IBL] it makes it melt. It makes the conflict melt, and people start to see, “Oh, that’s … yeah. Part of it is because of this …. Yeah, part of it is because of that …. So, now it’s not my narrative or my perspective, it is more of a combination of them.” [Fatima]

The experts described IBL at the mesosystem and exosystem levels as a process of analyzing or problematizing what values, perspectives, or narratives are considered socially valuable, and examining how they are operationalized in the larger system (e.g. national curricula, media, etc.) to gain insight into realistic ways in which an individual can confidently introduce multiperspective teaching practices, whether it be in a validated or subversive manner. For instance, Daan suggested the following: ‘I think it’s important to focus on usability [and] impact. Maybe even, if the topic is something that is underserved in their various curriculum, they could put that down on paper. Why is it [underserved]?’

Learning activities

To support the above-mentioned training approaches, the experts discussed various learning activities to promote teachers’ understanding and use of multiperspectivity. In particular, the experts emphasized discussion, resource-based exercises, and reflection. First, discussion referred to any group dialogue or collaborative exchange of information. Depending on the environment level or boundary in question, the experts proposed open-ended and teacher-centered discussions. They typically started with topics like personal biographies or teaching philosophies and methods and later discussed, if the training group was able to build up a sense of mutual engagement and trust, their perceptions of contested histories or the political climate of their country. This exchange of diverse lived experiences serves as a source of multiperspectivity and facilitates the development of interpersonal connections, perhaps offsetting the impact of the teacher level boundaries. For instance, Leonor prioritized discussion in saying that,

A good training is a process where everybody is sharing, learning from everyone in the discussion, and everybody is really constructing their new knowledge, finding meaning from that knowledge as well as a new way of looking at things. That is how they learn about and get a critical understanding of other different and new perspectives.

At the microsystem level, discussion was used by the experts firstly to support students in overcoming similar mental and emotional boundaries to engaging with multiple perspectives. Secondly, it was used to create a dialogue between the past and present that establishes the relevance of multiperspectivity (e.g. to prevent future division or contention) and increases students’ interest in and willingness to engage with multiple perspectives.

Resource-based learning (RBL) and resource-based exercises were emphasized by all twelve experts and involve (re)using available assets (e.g. primary and secondary sources, artifacts, people, media, places) to support learners’ various learning needs and knowledge gaps. The resources most frequently mentioned by the experts were history textbooks, photographs, audio recordings, videos, source collections, national curricula, educational policies, and scholarly publications on the topic of multiperspectivity. For teacher- or student-related boundaries, RBL may include working with a source collection on one period or historical event to raise awareness about the epistemological validity of multiple perspectives or the provisional nature of history. However, the experts continually expressed caution about such exercises, as they may introduce the possibility of emotional discomfort or identity threats among the teachers. Should teacher trainers see that the teachers are experiencing such discomfort, they should select sources that are geographically distant or emotionally and politically cold (e.g. source collections on a similar controversy but from another country). Marija discussed using photographs to trigger a discussion on multiperspectivity rather than an actor’s account of an event as photographs are more open to interpretation and less likely to provoke an emotional or defensive response: ‘You are not going into any narratives, you are not describing how it was at large, you are not explaining this is how it is … It was a moment that was frozen, and now tell me what you see … Why? For whom?’

At the mesosystem and exosystem levels, the experts encouraged teacher trainers to base learning activities on resources that embody the boundary or bear some authority over the teachers’ practices (e.g. an obligatory textbook, educational policy briefs), for example, asking the teachers to evaluate the degree to which the source (e.g. curriculum) is multiperspective, how it impacts their current capacity to activate multiperspectivity in the classroom, or how it can be leveraged in a way that is adequately multiperspective. So, if these teachers experience backlash from school-, community-, or student-related actors, they can substantiate their actions based on a higher authority.

Lastly, (self-)reflection activities refer to time allocated within the training during which teachers reflect on the learning process, build their intention to activate their new knowledge, or outline an action plan. (Self-)reflection was used by the experts for different purposes, at different stages of the training (e.g. beginning, middle, end), and for boundaries at different environment levels. For instance, the experts used reflection at the start of a training as a tool to position teachers in the wake of a boundary. Mary described the importance of reflection as a starting point by saying, ‘Multiperspectivity in a post-conflict environment is requiring teachers to really think about their own points of view, so that they can either set them aside – if they can be – or work with them so that they recognize that they have implicit bias’.

Through (self-)reflection the teachers gain insight into their personal capacity to activate multiperspectivity and identify those areas in which they need to improve. While at the exosystem level, William suggested that teachers start by reflecting on their position in society (i.e. in- or out-group) or how different actors or systems can influence them or their ability to activate multiperspectivity in the classroom (e.g. government agencies, community leaders). Guided reflection at the middle point of a training was suggested for its use in identifying areas that need more attention, helping teachers renew their motivation and engagement, or supporting teachers in drawing connections between the different boundary levels. For example, Nathanial said: ‘Contrast between how we are today on the second day with how we were yesterday; and if it works out well … because they’ve got to know each other and got to trust each other, they are more prepared to reveal more of themselves’.

At the end of the training, reflection was used by the experts to instill teachers with a sense ownership in multiperspectivity and a duty to broker multiple perspectives in the classroom, for example, goal setting at one or more environment levels to continue one’s growth beyond the training context. Daan exemplified this by saying, ‘[At the end] they [teachers in a training] would say, “Well, now I know that it’s actually much more challenging than I thought, but I feel more comfortable about X and I still have remaining doubts about Y”’.

Discussion

To contribute to the operationalization of multiperspectivity in post-conflict history education, this study aimed to provide educationalists with a deeper understanding of post-conflict-system-related boundaries to brokering multiperspectivity in the classroom and effective teacher training methods for supporting teachers’ development into brokers of multiperspectivity. Expert teacher trainers, qualified on the basis of their unique and extensive experiences with post-conflict education, were interviewed. The findings of this study can thus be used to improve the design of future teacher trainings and to advance multiperspective education in post-conflict societies.

The findings support previous research studies’ claims that there are active boundaries to teachers’ use of multiperspectivity in the classroom (Wansink, Akkerman, and Kennedy Citation2021a; Wansink, de Graaf, and Berghuis Citation2021b; Cohen Citation2020; Psaltis, Carretero, and Čehajić-Clancy Citation2017). Based on these findings, a preliminary model of teachers’ development environment and its related boundaries has been proposed (). It provides an overview of the ten different boundaries identified and their reciprocal influence on teachers, further highlighting the complex influence post-conflict societies have on their teachers and their use of multiperspectivity. More specifically, it highlights how the layers within a teacher’s environment can compound in such a way that compels and confines a teacher to take a single perspective. For example, school-related actors’ (microsystem) fear of negative attention from the community (exosystem) may result in school administrators punishing or vilifying teachers who try to introduce multiperspective practices (teacher), thus reinforcing the need for brokers of multiperspectivity and multilevel teacher trainings or interventions. These findings suggest that trainings solely targeted at the teacher level may be too narrow to advance multiperspective practices or sustain teachers’ transition from a single to multiple perspectives.

The second set of findings within this study, the pedagogical methods for producing competent brokers of multiperspectivity, were congruent with the recommendations within the recent literature on multiperspectivity and post-conflict education (Brett et al. Citation2009; Council of Europe [CoE] Citation2015; Kello Citation2016; McCully Citation2012). Five methods appear to be the most effective in supporting teachers’ transition to brokers of multiperspectivity, each requiring teachers to confront or leverage their boundaries in a constructive way to facilitate the use of multiperspectivity in the classroom. The most distinct contribution of this study is that there seems to be a structure for these methods. Two overarching training or intervention approaches were revealed: project-based and inquiry-based learning. Project-based learning focuses on forming conclusions or tangible tools that reconcile the differences between that which is acceptable in the teachers’ environment and the multiperspective teaching practices learned in the training (e.g. lesson plans), while an inquiry-based learning approach aims to grow teachers’ resilience to boundaries. By routinizing inquiry and problematization, teachers’ tolerance of ambiguity rises, and their emotional discomfort lowers, thereby making them more open to critically evaluating multiple perspectives, history education at large, or the underlying assumptions beneath each system level and their own practices. This ultimately equips teachers with the dispositions and disciplinary skills necessary to reduce or nullify the impact of the boundaries.

Finally, the learning activities – discussion, resource-based exercises, and (self-) reflection – should be embedded within the approaches discussed above. This combination of activities targets the emotional and cognitive boundaries at the personal level while mirroring historical methods (e.g. the exchange of lived experiences as evaluating historical evidence and empathy training), allowing learners to approach multiperspectivity and the high emotions and trauma of a historical conflict from either a distanced or personal lens. For example, the experts named teachers’ own epistemologies (i.e. critical understanding) on historical knowledge as a boundary to teaching history from multiple perspectives. So, resource-based exercises with ‘cold’ or distanced conflicting sources not only show different sides of the conflict but can also help teachers to understand that history involves construction (Wansink, Akkerman, and Wubbels Citation2016; Wansink et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, by gaining more epistemological confidence, it may help teachers deal with the emotions underlying tolerance of ambiguity, which is inherently part of multiperspectivity in history education and is especially salient and difficult to deal with in post-conflict societies. Similarly, discussion and critical reflection should be considered as empathy-developing teaching approaches, as they reinforce both teachers’ and students’ resilience to boundaries and bolster their willingness to approach history education through a multiperspective lens. This supports Zembylas and Loukadis’s (Citation2021) assertion that teachers’ affective practices should be recognized and that teachers should be prepared with the emotional knowledge and skills to confront difficult topics and emotions in the classroom.

Limitations and future research

Despite Bronfenbrenner’s (Citation1979) ecological systems theory being widely accepted by the scientific community, it has been criticized for its overrepresentation of context and its influence on the development process (Bronfenbrenner Citation1989; Tudge et al. Citation2009). An emphasis on context was advantageous for this study, as it meant that the teachers’ different system levels could be mapped and discussed in terms of their influence on teachers and the classroom. However, without acknowledging the role of teachers and their influence on their own development or the larger system, it leaves teachers in a vulnerable position, as trainings are typically targeted at the teacher level. Future research is needed at the mesosystem level, as our research shows that actors at this level (i.e. parents) can directly hinder teachers from teaching history from multiple perspectives. Additionally, the experts highlighted that teachers can be confronted with a moral dilemma when they want to deconstruct the ‘closed’ narratives that students learn at home, as it may threaten to break the bond between parent and child (Wansink, Akkerman, and Kennedy Citation2021a). We propose that future interventions and teacher trainings should address all dimensions of the teachers’ environment to be most effective.

Furthermore, this research was conducted with a small sample of teacher trainers and was based on a general conceptualization of post-conflict societies. Thus, the findings cannot be generalized to every post-conflict context and may include several blind spots. Each post-conflict society is distinctly different and therefore has distinct training needs (Haavelsrud and Stenberg Citation2012). Future research is needed to first see whether these findings are applicable to all types of conflict. Secondly, these findings reflect teacher trainers’ perceptions of the boundaries rather than teachers’ direct experiences with their environment. Future research should determine whether teacher trainers’ perceptions are congruent with teachers’ lived experiences. Thirdly, each teacher may experience the boundary or discontinuity between their day-to-day and training practices differently. Therefore not every boundary will be equally salient for each teacher or post-conflict system, as each teacher has particular personal and professional experiences that make them more or less competent and comfortable approaching such boundaries. Lastly, the boundaries discussed in this study are those related to past conflicts; future research should be conducted to gain a more comprehensive understanding of all of the boundaries within a teacher’s environment (e.g. access to technology, professional development courses).

Implications for practice

These findings have several implications for practice. First, the model in may be used by teacher trainers, NGOs, or history teacher associations as an analytical lens to evaluate a post-conflict system or country. From this, an effective teacher training design or intervention can be derived to target all levels of the teachers’ system (e.g. needs analysis, setting intended learning outcomes) and to identify and connect actors from each level to establish a community of change. Secondly, based on the findings of the second research question, several preliminary recommendations for teacher training design can be proposed, such as long-term projects with a focus on project-based or inquiry-based learning within which both informal and formal sessions of discussion and reflection are embedded. In addition, equipping teacher trainers with ample resources that can be used to overcome the boundaries at each level of the teachers’ environment (e.g. textbooks, lesson plans, or literature on multiperspectivity, addressing controversial issues, transgenerational trauma, etc.).

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are given to Steven Stegers for providing thorough feedback on this manuscript and for helping us recruit participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Devon Abbey

Devon Abbey, MSc, is an Education Development Officer at the Department of Educational Quality, University of Groningen. Her main areas of interest are multiperspectivity, teacher education, boundary crossing, internationalization, and technology enhanced learning.

Bjorn G. J. Wansink

Bjorn G. J. Wansink is associate professor and teacher educator at the Department of Education, Utrecht University. His main areas of interest are multiperspectivity, cultural diversity, history, citizenship, epistemology, teacher education, critical thinking, boundary crossing, and dealing with controversial issues.

References

- Ahonen, Sirkka. 2014. “History Education in Post-Conflict Societies.” Historical Encounters 1 (1): 75–87.

- Akkerman, Sanne F., and Arthur Bakker. 2011. “Boundary Crossing and Boundary Objects.” Review of Educational Research 81 (2): 132–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311404435.

- Alexander, Cheryl S., and Henry Jay Becker. 1978. “The Use of Vignettes in Survey Research.” Public Opinion Quarterly 42 (1): 93–104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/268432.

- Bakker, Arthur, and Sanne Akkerman. 2019. “The Learning Potential of Boundary Crossing in the Vocational Curriculum.” In The Wiley Handbook of Vocational Education and Training, edited by David Guile and Lorna Unwin, 349–372. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, . doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119098713.ch18.

- Birt, Linda, Suzanne Scott, Debbie Cavers, Christine Campbell, and Fiona Walter. 2016. “Member Checking: A Tool to Enhance Trustworthiness or Merely A Nod to Validation?” Qualitative Health Research 26 (13): 1802–1811. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316654870.

- Bowen, Glenn A. 2006. “Grounded Theory and Sensitizing Concepts.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 5 (3): 12–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690600500304.

- Brett, Peter, Pascale Mompoint-Gaillard, Maria Helena Salema, and Sarah Keating-Chetwynd. 2009. How All Teachers Can Support Citizenship and Human Rights Education: A Framework for the Development of Competences. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, Urie. 1989. “Ecological Systems Theory.” In Annals of Child Development, edited by Ross Vasta, 187–249. Stamford: JAI Press.

- Carcary, Marian. 2009. “The Research Audit Trial—Enhancing Trustworthiness in Qualitative Inquiry.” Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 7 (1): 11–24.

- Çelebi, Elif, Maykel Verkuyten, Talha Köse, and Mieke Maliepaard. 2014. “Out-Group Trust and Conflict Understandings: The Perspective of Turks and Kurds in Turkey.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 40: 64–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.02.002.

- Clarke-Habibi, Sara. 2018. “Teachers’ Perspectives on Educating for Peace in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Journal of Peace Education 15 (2): 144–168. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2018.1463209.

- Cohen, Aviv. 2020. “Teaching to Discuss Controversial Public Issues in Fragile Times: Approaches of Israeli Civics Teacher Educators.” Teaching and Teacher Education 89: 103013. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.103013.

- Conrad, Jenni. 2020. “Navigating Identity as a Controversial Issue: One Teacher’s Disclosure for Critical Empathic Reasoning.” Theory and Research in Social Education 48 (2): 211–243. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2019.1679687.

- Corredor, Javier, Maria Emma Wills-Obregon, and Mikel Asensio-Brouard. 2018. “Historical Memory Education for Peace and Justice: Definition of a Field.” Journal of Peace Education 15 (2): 169–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2018.1463208.

- Council of Europe [CoE]. 2011. The Committee of Ministers to Member States on Intercultural Dialogue and the Image of the Other in History Teaching. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe [CoE]. 2015. Living with Controversy Training Pack for Teachers: Teaching Controversial Issues through Education for Democratic Citizenship and Human Rights (EDC/HRE). Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe [CoE]. 2016. Competencies for Democratic Culture: Living Together as Equals in Culturally Diverse Democratic Societies. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Council of Europe [CoE]. 2019. Learning to Live Together: Council of Europe Report on the State of Citizenship and Human Rights Education in Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- du Toit, Dominique. 2020. The Palgrave Handbook of Conflict and History Education in the Post-Cold War Era. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- European Association of History Educators [EuroClio]. 2020. “Who We Are.” Accessed 12 November 2020. https://www.euroclio.eu

- Gehlbach, Hunter. 2004. “Social Perspective Taking: A Facilitating Aptitude for Conflict Resolution, Historical Empathy, and Social Studies Achievement.” Theory & Research in Social Education 32 (1): 39–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2004.10473242.

- Goldberg, Tsafrir. 2017. “The Official, the Empathetic and the Critical: Three Approaches to History Teaching and Reconciliation in Israel.” In History Education and Conflict Transformation, edited by Charis Psaltis, Mario Carretero, and Sabina Čehajić-Clancy, 277–299. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54681-0.

- Goldberg, Tsafrir, and Yiftach Ron. 2014. “‘Look, Each Side Says Something Different’: The Impact of Competing History Teaching Approaches on Jewish and Arab Adolescents’ Discussions of the Jewish–Arab Conflict.” Journal of Peace Education 11 (1): 1–29. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2013.777897.

- Grever, Maria, and Robbert-Jan Adriaansen. 2019. “Historical Consciousness: The Enigma of Different Paradigms.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 51 (6): 814–830. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2019.1652937.

- Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. 2006. “How Many Interviews are Enough? an Experiment with Data Saturation and Variability.” Field Methods 18 (1): 59–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822x05279903.

- Haavelsrud, Magnus, and Oddbjørn Stenberg. 2012. “Analyzing Peace Pedagogies.” Journal of Peace Education 9 (1): 65–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2012.657617.

- Härkönen, Ulla 2007. “The Bronfenbrenner Ecological Systems Theory of Human Development.” Paper presented at the fifth annual conference PERSON. COLOR. NATURE. MUSIC., Daugavpils, October 17–21.

- Harris, Ian M. 2004. “Peace Education Theory.” Journal of Peace Education 1 (1): 5–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1740020032000178276.

- Jenkins, Nicholas, Michael Bloor, Jan Fischer, Lee Berney, and Joanne Neale. 2010. “Putting It in Context: The Use of Vignettes in Qualitative Interviewing.” Qualitative Research 10 (2): 175–198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109356737.

- Kello, Katrin. 2016. “Sensitive and Controversial Issues in the Classroom: Teaching History in a Divided Society.” Teachers and Teaching 22 (1): 35–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1023027.

- King, John T. 2009. “Teaching and Learning about Controversial Issues: Lessons from Northern Ireland.” Theory and Research in Social Education 37 (2): 215–246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2009.10473395.

- Kuppens, Line, and Arnim Langer. 2016. “To Address or Not to Address the Violent past in the Classroom? that Is the Question in Côte d’Ivoire.” Journal of Peace Education 13 (2): 153–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17400201.2016.1205002.

- Low-Beer, Ann. 1997. The Council of Europe and School History. Strasbourg: Council of Europe, Directorate of Education, Culture and Sport.

- Maia, Sheppard, and Sara A. Levy. 2019. “Emotions and Teacher Decision-Making: An Analysis of Social Studies Teachers’ Perspectives.” Teaching and Teacher Education 77 (1): 193–203. doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.09.010.

- Mason, Peter, Marcjanna Augustyn, and Arthur Seakhoa‐King. 2009. “Exploratory Study in Tourism: Designing an Initial, Qualitative Phase of Sequenced, Mixed Methods Research.” International Journal of Tourism Research 12 (5): 432–448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.763.

- McCully, Alan. 2012. “History Teaching, Conflict and the Legacy of the Past.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 7 (2): 145–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197912440854.

- McCully, Alan, and Jacqueline Reilly. 2017. “History Teaching to Promote Positive Community Relations in Northern Ireland: Tensions between Pedagogy, Social Psychological Theory and Professional Practice in Two Recent Projects.” In History Education and Conflict Transformation, edited by Charis Psaltis, Mario Carretero, and Sabina Čehajić-Clancy, 301–320. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54681-0_12.

- Nygren, Thomas, Monika Vinterek, Robert Thorp, and Margaret Taylor. 2017. “Promoting a Historiographic Gaze through Multiperspectivity in History Teaching.” In International Perspectives on Teaching Rival Histories, edited by Henrik Åström Elmersjö, Anna Clark, and Monika Vinterek, 207–228. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-55432-1_10.

- Oulton, Christopher, Vanessa Day, Justin Dillon, and Marcus Grace. 2004. “Controversial Issues—Teachers’ Attitudes and Practices in the Context of Citizenship Education.” Oxford Review of Education 30 (4): 489–507. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498042000303973.

- Parker, Christina. 2016. “Pedagogical Tools for Peacebuilding Education: Engaging and Empathizing with Diverse Perspectives in Multicultural Elementary Classrooms.” Theory and Research in Social Education 44 (1): 104–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2015.1100150.

- Paulson, Julia. 2015. ““Whether and How?” History Education about Recent and Ongoing Conflict: A Review of Research.” Journal on Education in Emergencies 1 (1): 14–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.17609/N84H20.

- Psaltis, Charis, Mario Carretero, and Sabina Čehajić-Clancy. 2017. History Education and Conflict Transformation: Social Psychological Theories, History Teaching and Reconciliation. Cham: Springer Nature. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-54681-0.

- Stradling, Robert. 2003. Multiperspectivity in History Teaching: A Guide for Teachers. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Tsafrir, Goldberg, and Geerte M. Savenije. 2018. “Teaching Controversial Historical Issues.” In The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, edited by Scott Metzger and Lauren McArthur Harris, 503–526. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, . doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119100812.ch19.

- Tudge, Jonathan R. H., Irina Mokrova, Bridget E. Hatfield, and Rachana B. Karnik. 2009. “Uses and Misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory of Human Development.” Journal of Family Theory & Review 1 (4): 198–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2009.00026.x.

- Van der Leeuw-roord, Joke. 2001. “EUROCLIO, A Cause for or Consequence of European Historical Consciousness.” In History for Today and Tomorrow: What Does Europe Mean for School History?, edited by Joke van der Leeuw-roord, 249–268. Hamburg: Korber-Stiftung.

- Wansink, Bjorn G. J., Sanne Akkerman, and Brianna L. Kennedy. 2021a. “How Conflicting Perspectives Lead A History Teacher to Epistemic, Epistemological, Moral and Temporal Switching: A Case Study of Teaching about the Holocaust in the Netherlands.” Intercultural Education 32 (4): 430–445. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2021.1889986.

- Wansink, Bjorn G. J., Sanne Akkerman, and Theo Wubbels. 2016. “Topic Variability and Criteria in Interpretational History Teaching.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 49 (5): 640–662. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1238107.

- Wansink, Bjorn G. J., Sanne Akkerman, Itzél Zuiker, and Theo Wubbels. 2018. “Where Does Teaching Multiperspectivity in History Education Begin and End? an Analysis of the Uses of Temporality.” Theory & Research in Social Education 46 (4): 495–527. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2018.1480439.

- Wansink, Bjorn G.J., Beatrice de Graaf, and Elke Berghuis. 2021b. “Teaching under Attack: The Dilemmas, Goals, and Practices of Upper-elementary School Teachers When Dealing with Terrorism in Class.” Theory & Research in Social Education 1–21. https://doi-org.proxy.library.uu.nl/10.1080/00933104.2021.1920523.

- Wansink B, Logtenberg A, Savenije G, Storck E and Pelgrom A. (2020). Come fare lezione su gli aspetti ancora vivi e sensibili della storia passata? La rete delle prospettive. Novecento.org, 14 https://doi.org/10.12977/nov342

- Wansink, Bjorn G. J., Jaap Patist, Itzél Zuiker, Geerte Savenije, and Paul Janssenswillen. 2019. “Confronting Conflicts: History Teachers’ Reactions to Spontaneous Controversial Remarks.” Teaching History 175: 68–75.

- Zembylas, Michalinos. 2017. “Teacher Resistance to Engage with ‘Alternative’ Perspectives of Difficult Histories: The Limits and Prospects of Affective Disruption.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 38 (5): 659–675. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2015.1132680.

- Zembylas, Michalinos, and Froso Kambani. 2012. “The Teaching of Controversial Issues during Elementary-Level History Instruction: Greek-Cypriot Teachers’ Perceptions and Emotions.” Theory and Research in Social Education 40 (2): 107–133. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2012.670591.

- Zembylas, Michalinos, and Loizos Loukaidis. 2021. “Affective Practices, Difficult Histories and Peace Education: An Analysis of Teachers’ Affective Dilemmas in Ethnically Divided Cyprus.” Teaching and Teacher Education 97: 2. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103225.