ABSTRACT

The critical and popular reception of Bigelow’s work has long pivoted on her gaze: what constitutes the ‘Bigelow look’?; how is it distinctive, unsettling, or otherwise surprising? This curiosity, frequently centred on her command of action and violence, is key also to her unusually heightened visibility as a woman filmmaker who can claim membership of what Deborah M. Sims terms the ‘celebrity directors’ club; that is, ‘an elite community of auteur filmmaking [coded] as masculine’ (2014). At the same time, interwoven in this status is the gaze on Bigelow, since her recognition factor has unquestionably been bolstered too by her photogenic looks, style, and deportment. Yet analysis of this regime of visibility remains limited in feminist film criticism, no doubt because it risks compounding the kind of gendered scrutiny and conservative discourses of judgmental comparison that feminist film criticism seeks to challenge. Analysing images of Bigelow that have circulated in the public domain as well as the critical reception of her work, this article interrogates the duality of the question, ‘How does she look?’, identifying how the entangled practices of looking surrounding Bigelow have fuelled the cultural prominence she holds as a woman director in contemporary US cinema.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

This article emerges, as with the others collected here, from the ‘Kathryn Bigelow: A Visionary Director’ conference held in Wolverhampton in summer 2019. It was an event at which I was prompted to reflect, in somewhat perplexed fashion, that it was now close to two decades since Sean Redmond and I had embarked on our co-edited collection on her work, The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor (Wallflower Press, 2003) (astonishingly, also still the only book-length academic study of Bigelow). Developing that project then, neither of us could have foreseen the career that still lay ahead for Bigelow. Rather, back in 2003 as we prepared for the book to come out, things were not looking promising for Bigelow. Sean and I ‘joked’, nervously, about whether our book had inadvertently acted as some kind of scholarly kiss of death, and we had perhaps cannily managed to publish it at exactly the moment Bigelow’s career dried up and she disappeared from the industry and public eye. But our joking also belied fears that another woman director was perhaps about to become ‘lost’. In a straight run, Strange Days (Bigelow 1995), The Weight of Water (Bigelow 2000), and K-19: The Widowmaker (Bigelow 2002) had all failed to deliver the critical appreciation of her earlier work, or the box-office hopes invested in them. Was Bigelow going to be finished just as Hollywood Transgressor hit the shelves? Who was going to take a punt now on a (woman) director with three flops in a row? At the same time, interviews with Bigelow have always underlined her assuredness, tenacity, and inventiveness. And in keeping with this, when she did eventually make her cinematic ‘comeback’, as it turned out, it was the last word in comebacks.Footnote1 Propelling her into the public domain and to the top of the cultural agenda for a period, Bigelow made cinematic history when she became the first woman to win the Best Director Oscar in 2010 for The Hurt Locker (Bigelow 2008).

Aside from that ground-breaking Oscar, today, such has become Bigelow’s incontestably recognised place in film culture since those ‘underperforming’ years, that she has gone on to be honoured too by an exhibition at MoMA (‘Crafting Genre: Kathryn Bigelow’ 2011); retrospectives there and at the TIFFFootnote2 Cinematheque (‘Bigelow: On the Edge’: see Anderson Citation2017); as well as being venerated in commercial enterprises such as the 2020 Oscars Rolex advertising campaign (Rolex Citation2019); and, on a rather more modest scale, the UK-based online clothing store, ‘Girls on Tops’. Founded in 2017 to form a ‘t-shirt celebration of female voices in film’ for the style-and-cinema-savvy feminist consumer, their eye-catching designs print the names of women directors – including Bigelow – on bold but simple tees. They thereby combine an activist impulse (also donating a portion of profits ‘towards funding female directed film projects’) with the recognition that ‘T-shirts have an incredible power to communicate a dialogue between their wearer and the rest of the world’ (girlsontopstees.com). For the purposes of this article, this artefact acts as a useful crystallising instance of Bigelow’s cultural standing and cachet. Not all ‘female voices’ get a t-shirt, and an inevitable selectivity is at work in the Girls on Tops wardrobe. At the time of writing, there is no Penny Marshall t-shirt or Nora Ephron t-shirt or Cheryl Dunye t-shirt, for example. This begs the question, what does one communicate about oneself when one is seen in a Bigelow t-shirt, then? And how does Bigelow command or merit this visibility, while others do not (yet)? Riffing on the name of that original 2019 symposium, ‘Kathryn Bigelow: A Visionary Director’, this article draws on a cultural breadth of print media coverage of Bigelow from the broadsheet press to women’s magazines, focusing largely but not only on the post-The Hurt Locker period, in order to anatomise the nature of Bigelow’s visibility in public discourse. In doing so, its purpose is to examine how questions of ‘vision’ have long been and continue to be central to understanding Bigelow’s meaning(s) and circulation in film culture and the wider public sphere. By looking not so much at her films, but rather how Bigelow has been constructed as a recognisable figure in their reception and the promotion and publicity surrounding them, I identify the ways in which how a woman filmmaker looks have here informed and directed the shape of the meaning/s she contains.

The title of this work thus deliberately pivots on the duality of meaning comprised within it; I argue that the question of ‘how Bigelow looks’, in both its senses, lies at the core of the heightened visibility she lays claim to. It is central to understanding why, unlike many of her woman director peers (few though they are), Bigelow is visible. In the process, the critical intervention made here sheds light on some of the crucial ways in which women directors are able/not able to become seen – again, in both senses of the term, that is, in becoming both individuals that are recognised on sight, and filmmakers whose work gets made. (Bigelow’s ultimate staying power, despite her run of disappointments at the turn of the millennium, belies the trajectories of many other women directors whose careers have been demolished by a single stumble).

In her 2010 article, ‘Vision and Visibility: Women Filmmakers, Contemporary Authorship, and Feminist Film Studies’, Yvonne Tasker perceptively opens up the magnitude of the visibility of women practitioners. She notes the significance of ‘how often and in what kinds of places’ (Citation2010, 215) audiences get to see these professional women making films ‘in an era in which the visibility of the filmmaker, whether as personality or auteur, is regularly foregrounded’Footnote3 and, furthermore, given that ‘there are very different issues at stake for men and women in this business’ (Citation2010, 214). Tasker observes that at one level one might argue the significance of the visibility of women filmmakers is just as true of women working in any male-dominated field, such as law or politics. Still, she argues, the filmmaker is a ‘special case in this context to the extent that she is a public figure of a quite particular type, both creative and commercial’. She is one whose captured, material presence speaks to the manifestation of ‘women who visibly, publicly appropriate titles perceived as male’ (Tasker Citation2010, 214), a position Tasker corroborates through four case studies comprising directors Bigelow and Allison Anders, and cinematographers Ellen Kuras and Maryse Alberti. While there have been a multitude of initiatives and campaigns to recognise and redress the gender inequities of the film industry in the decade since Tasker was writing, the landscape she paints nevertheless remains all too familiar. Taking the baton from Tasker in the work she initiated in 2010, then, (when she was writing also before the media reception of The Hurt Locker and Bigelow’s Oscar win) what do we find when we ‘pull focus’, shifting from the larger industrial canvas Tasker examined to bring the visioning of Bigelow alone more sharply into the foreground? In particular, I suggest in what follows that the twin-pronged fascination with practices of looking surrounding Bigelow are entangled in such a way that they have fuelled a degree of cultural prominence and capital for her that women directors have long been overwhelmingly excluded from. I contend that we cannot begin to fully understand how Bigelow has courted or won her status without looking beyond her films and the matter of how she as a filmmaker looks within them, to really scrutinise how she as a filmmaker is looked at – and how these intersect.

A strange gaze for a woman? Bigelow’s ‘discourse on vision’

In a career now spanning four decades, the critical and popular reception of Bigelow’s work has repeatedly returned to the question of her gaze, and what constitutes the ‘Bigelow look’. Indeed, Laura Rascaroli opens her 1997 Screen article on Bigelow, ‘Steel in the gaze’, with the declaration that ‘Kathryn Bigelow’s cinema is essentially a discourse on vision’ (Citation1997, 232). Both reviewers and scholars have been driven throughout Bigelow’s career, then, to pin down the exact nature of this ‘discourse on vision’, to articulate what makes it so distinctive, so proficient and, moreover, unsettling and otherwise startling. One could conjecture that similar rhetoric surely informs the discourse surrounding any number of directors; the whole question of ‘directorial vision’ is perceived to lie at the heart of what the director does, after all. But Bigelow’s films are particularly widely agreed to evidently and skilfully play in intensified ways with subjectivity, sensory perception, camera movement and fluidity, often but not exclusively in extraordinarily adroit action-sequences that especially invite this mode of enquiry (see, for example, Burgoyne Citation2012, 13–14; Jermyn and Redmond Citation2003, 7–11; Smith Citation1995). What is more, commentators have found it particularly compelling to try to understand how Bigelow, as a woman, has come to acquire and hone such a gaze, since within her small pool of peers it sits so unexpectedly with enduring presumptions that women directors are more interested in and more ‘likely to excel’ in the realms of ‘character, story, and emotions rather than action’Footnote4 (Tasker Citation2010, 221).

Her films’ early innovations around Steadicam technologies, for example, make her an unusual example of a woman director closely aligned with particular technical ingenuity (see Smith Citation2013, 73–90). In Gavin Smith’s fascinating and lengthy 1995 interview with her in Film Comment which followed the release of Strange Days, the interviewer’s curiosity, and Bigelow’s enthusiasm regarding the intricacies of how she constructs her gaze leap off the page. Although Bigelow insists she is a filmmaker who is drawn first to character (for example, Dawson Citation2009; Keough Citation2013), what dominates the discussion in Film Comment is precisely the visual – ‘how she looks’ – as Smith invites her to comment on ‘the interplay of visual control and visual abandon’ in her work (Smith Citation2013, 84) and the ‘sculpted dimensionality’ (2013, 86) (my emphases) of her compositions, and Bigelow is able to reflect at length on such matters as her use of long focal lengths, whip-pans, and unbroken point-of-view shots (POVs). Indeed, interviewing her in 2009 for Newsweek, Jennie Yabroff was led to comment that what most engages Bigelow is ‘talking about the look of her movies: how many cameras she used on The Hurt Locker (four); the way she storyboarded each scene, translating the space from three dimensions to two in her mind; the effort she took to make sure the bomb explosions appeared authentic’ (Yabroff Citation2009). It is her visual dexterity that has earned her a name as the most accomplished woman director in action cinema; a gendering of her labour, vision, and skillset that she has long been at great pains to distance herself from (Jermyn Citation2003; also Paszkiewicz Citation2015, 167; Yabroff Citation2009). Hence, the question of whether one can locate an essence of some kind in the director’s look undoubtedly takes on a particularly loaded nuance when asked of Bigelow; that is, a woman who since the start of her career, despite her objections, has been perpetually framed as a woman director working in what are still enduringly widely perceived to be ‘male’ genres and fields of enquiry, broadly concerned with action and violence. Indeed, for Martha P. Nochimson lamenting the success of The Hurt Locker, Bigelow’s visibility has come precisely because she has adopted a mode of ‘muscular filmmaking’, in which ‘she masquerades as a hyper-macho bad boy to win the respect of a male-dominated industry’ (Citation2010).

Bigelow in the frame

Since the leisurely choreography of violent scenes across her earlier work starting with The Set-Up (Bigelow 1978) through to her transition following The Hurt Locker into quasi-documentary stories drawn from contentious and troubling ‘real-life’ events, critical curiosity has returned to the perplexing nature of this woman’s gaze. Latterly, inquisitiveness and controversy surrounding Bigelow’s gaze have asked more specifically if it glorified and endorsed torture in Zero Dark Thirty (2012); and, most recently, moving away from the notion of a merely gendered gaze to recognise the operation of a racialised gaze also, numerous commentators have asked whether Bigelow’s is also a presumptuously misplaced white gaze, following criticisms that it was insensitive and inappropriate for a white filmmaker to have taken on the subject of Detroit (Bigelow 2017) (see, for example, Dyson Citation2017). Throughout the various incarnations of this scrutiny, however, the consistent thread has been that her gaze is somehow indecorous, unruly, provocative.

This recurrent concern and inquisitiveness around Bigelow’s gaze has been key to her unusually heightened visibility as a woman director. Unlike the majority of her female peers, Bigelow has made it into what Deborah M. Sims (Citation2014) has termed the ‘celebrity directors’ club – that is ‘an elite community of auteur filmmaking that is coded as masculine and upholds admission standards predicated on maleness’ (2014). Indeed, adopting very similar idiom to Sims, the 2017 TIFF retrospective dedicated to Bigelow framed her as ‘one of the few female directors to break into the boys’ clubhouse of Hollywood’ (Anderson Citation2017). In this respect, Rona Murray’s arresting assertion that Bigelow cultivates an extra-textual ‘representation of herself as strong in masculine terms’ is germane here (Citation2011, 5), even while it is at the same time imperative that scholars of all disciplines scrutinise and undo the essentialist premises at work in such binaries. Murray’s argument seems borne out, for example, in a 2002 Guardian article entitled ‘I like to be strong’, published following the release of K-19: The Widowmaker. Writer Stuart Jeffries here refers to Bigelow as ‘a fifty-year old woman who loves to tell stories of her own derring-do’, noting that ‘she dives’, ‘she rides a mountain bike’ and ‘she climbed Mount Kilimanjaro in subzero temperatures’ (Citation2002), ‘visioning’ her almost as one of Point Break’s (1991) hyper-masculine thrill-seeking ‘Ex-Presidents’. This discourse is still there by the time of The Hurt Locker, where the New York Post profile of her following her Oscar win described her as ‘less like a director and more like a hero from a 1930s pulp novel’ (Tucker Citation2010); while a 2009 Newsweek feature opened with an anecdote from The Hurt Locker’s screenwriter-producer Mark Boal about how Bigelow showed more stamina in the punishing heat of the Jordan desert than all the ‘macho guys on the set’ including ‘British SAS, not to mention all these young, studly actors, [all] those guys were falling by the wayside’ (in Yabroff Citation2009).

At the same time, even while Bigelow’s seemingly ‘masculine’ interests coalesce within and outside her films, very much interwoven in this ‘celebrity director’ status is an evaluative, appreciative, objectifying gaze on Bigelow. In promotional shoots and events, she exhibits a steady taste for mannish-tailored suits and tuxes, simple monochrome colour palettes, and understated styling, while leather jackets and flats are also favourites, all of these sitting as signifiers that work neatly alongside her interest in perceived ‘male’ genres. They seem drawn on to signal a certain authoritative stance, one might conjecture, though one suggesting a modish awareness rather than dreary comportment, while at the same time her tall willowy frame, hair, and classically elegant (Western approved) features are regularly commented on gushingly by journalists. Writing two decades ago in her book Feminist Hollywood, Christina Lane had already observed by that time that Bigelow’s looks had fuelled a celebrity-director status for her. As she noted in 2000, ‘Often depicted as a glamorous woman who could have succeeded just as easily in front of the camera, Bigelow is discussed in terms of her appearance in nearly every press account I have read […] Mentioning Bigelow’s height and her model-like beauty works to further the construction of her “star” status’ (Citation2000, 103). Very much in this vein, then, a Telegraph interview with Bigelow remarks, ‘We meet in a suite of a smart London hotel. In person, Bigelow, 61, is engaging and attentive while exuding an air of cool authority. Strikingly handsome, with light brown hair cascading below her shoulders, she is slender and almost six feet tall […] [dressed] impeccably’ (Gritten Citation2013). As the nod to her age here alerts the reader, however, this is not an extract from a turn-of-the-millennium profile, but rather a piece promoting Zero Dark Thirty, written some thirteen years on from Lane’s pronouncement, and demonstrating the resilience with which this gendered framing persists. Indeed, it is particularly striking to see the persistence of this address as Bigelow advances through her 60s, given the ease with which celebrity culture and indeed everyday discourse typically erase ageing women as they grow older to render them invisible (Jermyn and Holmes Citation2015).

For all the attention to her ‘masculine-style’ physical strength and interests, then, Bigelow’s high-recognition factor has unquestionably been bolstered too by her arrestingly attractive looks and ability to pull off a head-turning style and deportment that deliver certain benchmarks of femininity, while she simultaneously maintains ‘a maverick image [that] is never fully detached from an idea of gender rebellion’ (Tasker Citation2010, 219). At the core of her visibility and distinctiveness is an intriguing contradiction in which Bigelow has gained entry into what Sims observes is ‘still very much an old boys club’ (2014, 191), in part by making films able to slot comfortably into that old boys club’s regime of ‘muscular filmmaking’ as Nochimson (Citation2010) contends; but also in part for her ability to project a highly marketable feminine ‘stamp’ alongside a refusal of gender. There is thus a fascinating kind of paradox to be found in the fact that because the construction of fame is entrenched in deeply gendered parameters within which ‘female celebrities are primarily circulated as corporeal signifiers’ (Holmes and Jermyn Citation2015, 17), Bigelow’s distinct brand of edgy but desirable, and, it must be recognised, white femininity has been instrumental in her admission to what remains principally a ‘masculine’ club.

Picture this: portraits of Bigelow

In keeping with the familiar speculation noted by Lane (Citation2000) that Bigelow might just as readily have had a career in front of the camera,Footnote5 Bigelow did in fact spend time as a performer earlier in her career. She appeared briefly in Lizzie Borden’s Born In Flames (1983), as well as videos made by artists Richard Serra and Lawrence Weiner among others (see Smith Citation1995), and most prominently, prior to the recent Rolex 2020 Oscars advertising, as a model for the 1989 Gap ‘Individuals of Style’ campaign. This is despite her entreating in a pre-Oscars 2010 interview for Italian Vogue as they prepared her for her photoshoot, ‘No make-up, let’s get it over with … no lip gloss and no stylist; I’m happy with a jacket and jeans … I’ve got an instinctive aversion to awards ceremonies and the spotlight’ (Croci Citation2010, 170). Her particular model of (again, by Western standards) attractiveness and photogenic-ness, with her long-limbed athletic physique, flawless bone structure and long, often loosely worn hair, have ensured that beyond and outside of promotional shoots of her at work on-set she is an apt subject for the kinds of coverage central to celebrity-style attention, including feature-articles, red carpet appearances, festivals, and awards ceremonies.

Yet closer analysis of this regime of visibility remains limited in feminist film criticism, despite Tasker’s 2010 intervention. This is in part no doubt because it threatens to replicate exactly the same models of gendered scrutiny and conservative discourses of hypercritical comparisons between women that feminist film criticism would seek to overthrow. Hence, it may well be that many feminist scholars are nervous of undertaking this work lest they be tainted by it – perceived as validating or reproducing precisely that which they seek to undo, and indulging interest in what is enduringly framed by ‘highbrow’ (read ‘masculine’) thought in academic circles as the superficial and trivial terrain of appearances. But to deny that corporeal signifiers feed the discursive construction of women filmmakers differently to men is, not unlike Bigelow, to refuse engagement with gender. Hence, in previous work on director Nancy Meyers, I examined, albeit briefly, whether it is not only Meyers’s less newsworthy oeuvre of ‘chick-flicks’ but her safely low-key, quietly tasteful, neat personal styling that could be seen as pertinent to her comparatively non-celebrity status, despite her being the most commercially successful woman director in history (Jermyn Citation2018). As a rare instance of a successful longstanding woman director peer of Bigelow, Meyers’s career and the discursive construction of her as a public figure thus form a fascinating point of comparison with Bigelow (who is just two years younger than Meyers, having been born in 1951). Consider two promotional profiles of the directors, both interviewed as their new films are about to be released, both published in US newspapers in 2009, by writers both affiliated with The New York Times, as follows:

With her black-framed glasses and penchant for wearing clothes that seem like a softer variant of a man’s business suit – white blouse, yellow cardigan over slacks, low-heeled patent-leather pumps – the petite and attractive Meyers might pass for a lawyer or professor; there’s nothing about her that shouts V.I.P. (Merkin (Citation2009) on the release of Meyers’s It’s Complicated (2009)).

Notably here, Meyers makes it as the cover story of the New York Times magazine, in what constitutes the largest press profile yet written about her. The accompanying image shows her standing among a cinema audience made up entirely of other women of ‘a certain age’, most of them, like her, white, all of them laughing merrily, many of them who look a little bit like the irreproachably turned-out Meyers, whose coiffed and expensively highlighted hairstyle and discreet make-up speak to a familiar raced and classed style widely favoured among well-heeled older US women of her milieu. She stands among them, softly lit with folded arms, smiling. She is dressed in a neat, cream ‘twin-set’ type ensemble with a scoop-neck top worn beneath a button-less ‘waterfall’ cardigan – a style widely noted as safely flattering to the middle-aged woman for draping in such a way that it is ‘feminine’ while not emphasising one’s actual physique – thus comfortably adhering to what Merkin encapsulates as an innocuously polished style.

Compare this with how Bigelow is envisioned by Carrie Rickey in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

Slim as lightning, Kathryn Bigelow makes movies charged with adrenaline … the six-footer with the radiant presence of a Redgrave and the steel nerves of a high-wire artist is drawn to stories about daredevils … in her untucked black shirt and skinny trousers [she] resembles a human exclamation point … The sinewy filmmaker is herself an athlete – “I hike, I bike, I ride horses” – who translates that physicality to the screen (Rickey (Citation2009) on the release of Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker).

Here, the accompanying image of Bigelow delivers the embodiment of this ‘human exclamation point’, featuring her in a slim-fit, sharply tailored black shirt, its undone buttons revealing a single silver crucifix worn at her throat, her hair worn loose. In a much edgier composition, shot in daylight, she stands adjacent to a window and looks away from the camera (although she is often photographed looking unsmilingly straight into the camera). The stark lighting and her thoughtful facial expression, seemingly captured mid-exchange, combine for an altogether moodier look befitting of her reputation and preferred subject matter. It is not difficult to understand how such an image is so much more beguiling to the media and to celebrity culture than that used by Merkin to describe Meyers above, nor, as noted, is it hard to find many similar instances of interviewers continuing to wax lyrical over Bigelow’s eye-catching style as she ages. In the promotional round for Detroit, then, for Clemence Goldszal in French Vogue, ‘Bigelow is beautiful, tall, and elegant: her hair is perfectly coiffed, though she apologizes for her light cotton blouse and jeans … On a very hot day in Beverly Hills, she remained cool with not a drop of moisture beading on her brow’ (Citation2017); while for Michael Eric Dyson in ELLE, ‘At Hollywood events, the tall, lanky Bigelow is a model of elegance, with a wholesome beauty that defies the arithmetic of her 65 years’ (Citation2017).

As part of his feature on her, esteemed African-American writer and academic Dyson tells how he visited his home city of Detroit with Bigelow. In the process, he was given to comment on how remarkably comfortably she was able to explore the city, observing of her, in admiring terms that start to read a little like a love note:

That day … Her face was sometimes partly obscured by gold-rimmed aviators, their dark tint hiding her hazel eyes; her light brunette hair was parted in the middle and lightly tousled, falling just below her shoulders. Whether in Hollywood or the hood, she never looked out of place, especially in Detroit, where her sleek but casual look mingled effortlessly with the working- and lower-middle-class practical wash-and-wear of no-nonsense strivers (Dyson Citation2017).

And it is this kind of consummate ability to deftly shape-shift according to the occasion and her surroundings, as Dyson alludes to here, which has worked so well for Bigelow in terms of her heightened visibility. Sometimes, as noted, profiles mention that she is not fond of the flashiness surrounding the industry, that she is reserved, perhaps even shy (Tucker Citation2010), and very private, setting advance parameters on the questions she will answer in interview (for example, stipulating she will only talk about her films or politics (Goldszal Citation2017)). In the photoshoots for profiles features, she deflects overt femininity and the continued call to speak about herself as a ‘woman filmmaker’ (which recurs despite her ongoing and clear resistance to this framing of her work) through cultivating an often striking androgyny. But nevertheless, and as the gendered demands of the celebrity machine particularly require women must, Bigelow can make an entrance; she can court a camera, she can hold a gaze, not least, as noted, for maintaining the kind of strong, athletic body that seems to warrant ongoing appreciative public commentary.

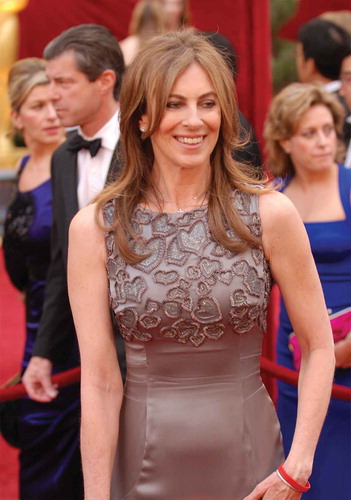

All this suggests that Bigelow’s ability to ‘work’ the industry’s gendered (which is to say pervasively misogynistic) publicity machine has heightened her profile in ways she has dexterously negotiated. The 2010 Oscars provided the definitive moment for her to manage the visioning of her brand, being the stage on which her distinctive image as a woman, and a woman director, in the public eye would be scrutinised and evaluated like no other.Footnote6 Her choice of dress, matched with subtle make-up and jewellery and loose hair again, might be read as an amalgam of all the impulses described above: a sleeveless titanium Yves Saint Laurent Edition Soir gown with an embroidered bodice, it was interestingly low-key, yet body-conscious (). The steel-grey was understated, even sombre, thus deflecting too much attention. But the unforgiving sleek satin material, and the fitted, shift-style cut could be ‘flattering’ to only the trimmest and most confident of bodies. This was a sentiment clearly shared by the coverage in the New York Post the next day. Beneath a picture of Bigelow with her Best Director and Best Picture Oscars held aloft in each hand, the caption reads, ‘Bigelow already had great toned arms – but now she’s got two golden dumbbells to incorporate into her gruelling workouts’ (Reed 2010), thereby turning her historic win into a victory for women’s conscientious later-life fitness (‘Yes, she’s 58!’ the writer remarks incredulously further into the story for added emphasis). Bigelow can move from elegant femininity to edgy androgyny in these and other high-profile moments with seeming consummate ease. This pleases and entertains a paparazzi gaze, and sits deliciously suggestively alongside a reputation for taking on macho stories and violence and, latterly, the ‘serious’ (which is to again say ‘masculine’) subject matter of real-world terror, such that ‘how Bigelow looks’ has become a complex amalgam of signifiers, mythos, and virtuosity.

Double take

To complete this analysis of the visioning of Bigelow, however, I want to look finally at a different realm of photographic record, one which constitutes a significant strand of the work managed by press and publicity executives in the industry, and which also forms an important tradition within film history. As alluded to above, alongside a body of visual material of Bigelow collected from public events of one kind or another, she is visioned too in ‘on-set’ or ‘on-location’ photography of her; that is, images belonging to an archive of photographic evidence of directors capturing them at work with crews and casts and technology, in the act of doing what they do. These can be shared by publicists for promotional purposes, or sometimes enter the public domain by less official means to form a kind of ‘candid’, insider chronicle or record of a given film, star, director, period, or location. Such photography forms a long, largely male-centred tradition within the industry’s bolstering of masculinist auteurist thinking. The commanding image of the director positioned authoritatively next to their camera is an iconic one in film histories, and though there has been some landmark feminist film analysis, particularly of Dorothy Arzner in this respect (Mayne Citation1994), it is an iconicity that has for much of cinema history been dominated by men.

However, one can very much trace a lineage of Bigelow through such imagery as she has regularly been documented in this way at work. Hence, in 2003, it was one such image of Bigelow from 1994 directing Near Dark that Sean Redmond and I elected to use on the cover of our book, seeing an opportunity to put an image of a ‘woman with a movie camera’ front and centre. Recently, promotional material for The Hurt Locker made widespread use of photos capturing the demands entailed in Bigelow’s labour directing on this project, as she worked on location in some extreme conditions in the Jordanian desert (images later visually echoed, in fact, by publicity for Zero Dark Thirty). Here, in huge dark glasses, cap, and layers protecting her from an unrelenting sun, shot against a bleak backdrop of sand and scorching sky, Bigelow kneels on the ground alongside a camera track, caught animatedly in mid-gesticulation; or standing, she points ahead, script in hand, directing her gript actors in blistering heat. One suspects this particular mode of visioning was deliberately fostered as a means to build her Oscar prospects, showing the tough reality of her labour on this film, picturing her in the thick of the heat and dust. It has served too to reenergise the reputation she has long fostered, as Jeffries put it, for ‘derring-do’ (Citation2002). But in the process, it also vividly underlined the importance of challenging and reconfiguring the dominant visual archive of directors in film history. This is a photographic record that has bolstered a culture in which directing and the seeming ability to command directorial authority became co-opted as ‘men’s work’, as women were largely shut out from it.

Indeed in 2018, this problematic erasure was precisely what prompted screenwriter and director Aline Brosh McKenna to launch the hashtag #FemaleFilmmakerFriday. Her goal was to encourage women practitioners to tweet photos of themselves at work, having been inspired by her friend Tamra Davis posting a picture of herself directing. Sharing a picture of herself on the set of Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, she thus noted that, ‘It’s hard to become what you do not see’ (@alinebmcekenna, January 26, 2018). Later explaining her motivation further in interview, she elucidated, ‘People carry around an image [sic] around in their head of what a director looks like. It’s a dude, and there’s kind of a baseball hat, and there’s maybe some cargo shorts … We just need different images … and just all different kinds of women’ (in Nguyen Citation2018) (my emphasis). Evidently, it could be argued that many images of Bigelow directing are not that ‘different’, and do not radically upend our expectations of what a dude/director looks like. In her aviators, and baseball caps, and puffer jackets and jeans and oversized t-shirts, Bigelow to some degree ‘looks the part’ on set even while her long loose hair again rattles the image. Has her ease with adopting this style, one which aligns her with another male cinematic history imbued with echoes of gravitas, again helped enable Bigelow’s entry into the ‘boys club’ of Hollywood celebrity-auteurs? Does it even matter, if she, or any other similarly attired woman director, is comfortable dressing like this to do her job – since for ‘female filmmakers’ to be ‘visioned’ at work at all in itself means not only ‘providing inspirational images’ but ‘[providing] exposure for women who are currently living the dream that so many can’t even envision …’ (Nguyen Citation2018).

After Hollywood Transgressor was published, in an essentially very favourable article, one review nevertheless expressed misgivings about our choice of three photos of Bigelow, noting that ‘one shows Bigelow with a (phallic) director’s viewfinder/telephoto lens, another shows Bigelow inactive behind a camera, and another shows [James] Cameron on the set of Strange Days with Bigelow’ (Baron Citation2007, 460). Their reception underlines how images of women directors at work are highly loaded; be they visioned alongside male collaborators, perceived as not looking the part (‘inactive’), or using ‘phallic’ tech, they risk being said to endorse and perpetuate, rather than reimagine or raze, this patriarchal visual history of directing. This is a premise that the impetus for the #FemaleFilmmakerFriday campaign unreservedly refutes, refusing to accept the machinery of directing as inherently ‘male’. As with my analysis, Brosh McKenna’s movement underlines the extent to which images of women practitioners do matter, and always have, as Judith Mayne’s work on Arzner (Citation1994) has previously so articulately shown. Through scrutinising the consequence of ‘how Bigelow looks’ here, this enquiry has exposed the extent to which her career trajectory has been shaped, in more ways than one, by a ‘discourse of vision’ (Rascaroli Citation1997). Nguyen’s Indiewire account of the #FemaleFilmmakerFriday campaign ends optimistically, suggesting, ‘The upshot of course is that with visibility, even more women will find work’ (Citation2018). In actuality, this outcome ‘remains to be seen’. But what is certain, is that film studies abets in expunging a discomforting but crucial arena in the gendered inequities of the industry when it sweeps the ‘superficial’ matter of how images of women directors are constructed and circulated under the (red) carpet.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Deborah Jermyn

Deborah Jermyn is Reader in Film & Television at the University of Roehampton, with particular research and teaching interests in questions of women’s authorship, Hollywood and genre, and ageing femininities in popular culture. She is author and co/editor of 11 books, among them Hollywood Transgressor: The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow (2003) (with Sean Redmond) and Nancy Meyers (2017).

Notes

1. For this reason and more besides, it is disconcerting that there has been no further book-length study of Bigelow since 2003, an absence from the academy that this special issue does significant work to address.

2. TIFF is the acronym for the Toronto International Film Festival.

3. See also Corrigan (Citation1991).

4. I have previously argued elsewhere in respect of Bigelow’s work that the premise that ‘action’ cinema is somehow in conflict with an interest in character and emotion is itself hugely reductive, particularly given the prominence of a melodramatic imagination through her oeuvre (Jermyn 2003). Furthermore, adherence to gendered distinctions about perceived ‘men’s’ vs ‘women’s’ cinematic styles and genres also again risks endorsing and perpetuating a range of troublingly essentialist presumptions that pivot on simplistic binary thinking (on this see also Paszkiewicz Citation2015, 171).

5. In the Harpers Bazaar online picture gallery of 2010 Oscars dresses, for example, the caption next to Bigelow reads simply, ‘Best-director winner Katherine Bigelow would look just as good on the other side of the camera’ (Anon Citation2010).

6. Images of Bigelow and her Oscars night dress are, unsurprisingly, available readily in numerous articles covering the 2010 ceremony, including the Harpers Bazaar photo gallery cited earlier (Anon Citation2010).

References

- Anderson, J. 2017. “Kathryn Bigelow’s Histories of Violence.” Toronto International Film Festival online, July 12. https://www.tiff.net/the-review/kathryn-bigelow-histories-of-violence

- Anon. 2010. “Red-carpet Dresses from the 2010 Oscars.” harpersbazaar.com, March 7. https://www.harpersbazaar.com/celebrity/party-pictures/g1394/oscars-2010-red-carpet-0310-2/?slide=27

- Baron, C. 2007. “Review of Hollywood Transgressor: The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow.” Quarterly Review of Film & Video 23 (5): 456–460. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10509200690902278.

- Burgoyne, R. 2012. “Embodiment in the War Film: Paradise Now and The Hurt Locker.” Journal of War & Culture Studies 5 (1): 7–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/jwcs.5.1.7_1.

- Corrigan, T. 1991. A Cinema Without Walls: Movies and Culture after Vietnam. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

- Croci, R. 2010. “Kathryn Bigelow.” Vogue Italia, March, n409: 170.

- Dawson, N. 2009. “Time's Up: Kathryn Bigelow's The Hurt Locker.” Filmmaker, Spring. https://filmmakermagazine.com/4686-times-up-kathryn-bigelows-the-hurt-locker-by-nick-dawson/#.YOcxCuhKjIV

- Dyson, M. E. 2017. ELLE, July 20. https://www.elle.com/culture/movies-tv/a46328/detroit-kathryn-bigelow/

- Girls on Tops. n.d. “A T-shirt Celebration of Female Voices in Film.” https://www.girlsontopstees.com/

- Goldszal, C. 2017. “How Kathryn Bigelow Rose to the Top of Hollywood.” French Vogue, October. https://www.vogue.fr/fashion-culture/fashion-exhibitions/story/kathryn-bigelow-detroit-movie-director-career/168

- Gritten, D. 2013. “Kathryn Bigelow Interview for Zero Dark Thirty: The Director on the Trail of Terrorism.” The Telegraph, January 18. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/9809355/Kathryn-Bigelow-interview-for-Zero-Dark-Thirty-The-director-on-the-trail-of-terrorism.html

- Jeffries, S. 2002. “I like to Be Strong.” The Guardian, October 21. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2002/oct/21/artsfeatures.features

- Jermyn, D. 2003. “Cherchez la femme. The Weight of Water and the Search for Bigelow in a Bigelow film.” In The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow: Hollywood Transgressor, edited by D. Jermyn and S. Redmond, 125–143. London: Wallflower Press.

- Jermyn, D., and S. Holmes. 2015. “Here, There and Nowhere: Ageing, Gender and Celebrity Studies.” In Women, Celebrity & Cultures of Ageing: Freeze Frame, edited by D. Jermyn and S. Holmes, 11–24. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jermyn, D. 2018. “Grey Is the New Green’?: Gauging Age(ing) in Hollywood’s Upper Quadrant Female Audience, The Intern (2015), and the Discursive Construction of ‘Nancy Meyers’.” Celebrity Studies 9 (2): 166–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2018.1465296.

- Jermyn, D., and S. Redmond, eds. 2003. Hollywood Transgressor: The Cinema of Kathryn Bigelow. London: Wallflower Press.

- Keough, P. 2013. “An Interview with Kathryn Bigelow.” In Kathryn Bigelow: Interviews, edited by P. Keough, 172–179. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

- Lane, C. 2000. Feminist Hollywood: From Born in Flames to Point Break. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Mayne, J. 1994. Directed by Dorothy Arzner. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Merkin, D. 2009. “Can Anybody Make a Movie for Women?” New York Times Magazine, December 15. https://www.nytimes.com/2009/12/20/magazine/20Meyers-t.html

- Murray, R. 2011. “Tough Guy in Drag? How the External, Critical Discourses Surrounding Kathryn Bigelow Demonstrate the Wider Problems of the Gender Question.” Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network 4 (1): 1–21.

- Nguyen, H. 2018. “The Story behind #femalefilmmakerfriday, Started by “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend’s” Co-Creator.” Indiewire.com, February 2.

- Nochimson, M. P. 2010. “Kathryn Bigelow: Feminist Pioneer or Tough Guy in Drag?” Salon.com, February 25. https://www.salon.com/2010/02/24/bigelow_3/

- Paszkiewicz, K. 2015. “Hollywood Transgressor or Hollywood Transvestite? The Reception of Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker.” In Doing Women’s Film History: Reframing Cinemas, Past and Future, edited by C. Gledhill and J. Knight, 166–178. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

- Rascaroli, L. 1997. “Steel in the Gaze: On POV and the Discourse of Vision in Kathryn Bigelow’s Cinema.” Screen 38 (3): 232–246. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/38.3.232.

- Rickey, C. 2009. “A Director Explores Men Who Dare Death.” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 9. https://www.inquirer.com/philly/entertainment/20090707_A_director_explores_men_who_dare_death.html

- Rolex. 2019. “Kathryn Bigelow: Rolex and Cinema.” https://www.rolex.org/arts/cinema/kathryn-bigelow

- Sims, D. M. 2014. “Genre, Fame and Gender: The Middle-Aged Ex-Wife Heroine of Nancy Meyers’s Something’s Gotta Give.” In Star Power: The Impact of Branded Celebrity(Vol I), edited by A. Barlow, 191–205. Westport: Praeger.

- Smith, G. 1995. “Momentum and Design.” Film Comment 31 (5): 46–60.

- Smith, G. 2013. “Momentum and Design” (reprinted from Film Comment, 1995, 31 (5)) in Kathryn Bigelow: Interviews, ed P. Keough, 73–90. Jackson: University of Mississippi Press.

- Tasker, Y. 2010. “Vision and Visibility: Women Filmmakers, Contemporary Authorship, and Feminist Film Studies.” In Reclaiming the Archive: Feminism and Film History, edited by V. Callaghan, 213–230. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Tucker, R. 2010. “I’m Queen of the World!” New York Post, March 9. https://nypost.com/2010/03/09/im-queen-of-the-world/

- Yabroff, J. 2009. “Kathryn Bigelow Talks about ‘The Hurt Locker’.” Newsweek, June 18. https://www.newsweek.com/kathryn-bigelow-talks-about-hurt-locker-80511