ABSTRACT

In 2023 approximately 339 million people needed humanitarian assistance and protection. This was a significant increase from the 274 million people in need in 2022, which was already the highest figure in decades (Global Humanitarian Overview 2023, Citation2023). Children are particularly vulnerable in these situations. Children living in and fleeing from areas affected by war and armed conflicts face a myriad of challenges that can have profound and lasting effects on their development and overall well-being. Multiple studies reveal the high prevalence of mental disorders and psychopathology among child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers. Research have revealed multiple risk and protective factors among children exposed to conflicts and war. These factors contribute to the adaptation processes, vulnerability, and resilience. This article discusses the risk and protective factors as well as the processes of vulnerability and resilience among children in conflict-affected regions, drawing from key research articles that shed light on the complexities of this issue.

In 2023, approximately 339 million people needed humanitarian assistance and protection. This was a significant increase from the 274 million people in need in 2022, which was already the highest figure in decades (Global Humanitarian Overview 2023, Citation2023). Children are particularly vulnerable in these situations. Children living in and fleeing from areas affected by war and armed conflicts face a myriad of challenges that can have profound and lasting effects on their development, mental health, and overall well-being. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) and the UN Security Council emphasize that violence against children in armed conflicts is a severe violation of children’s basic human rights. Such violence can result in persistent physical and psychological harm. In 2021 there were 23,982 grave violations against children, affecting 19,165 children (UN, Citation2022). This article discusses the vulnerability and resilience of children living in and fleeing from regions with armed conflicts, drawing from key research that shed light on the complexities of this issue.

Multiple studies reveal high prevalence of mental disorders and psychopathology among child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers as well as those living in the war zones. Most reviews combine prevalence from studies among children living in war zones or as internal or external refugees, and numbers vary greatly across different studies (Attanayake et al., Citation2009; Fazel et al., Citation2005; Mollica et al., Citation2004). The recent systematic review of Blackmore et al. (Citation2020), reported a 22.7% prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder, 13.8% prevalence of depression and 15.8% prevalence of anxiety disorders in these populations. For the unaccompanied minors (UMR), the prevalence is even higher (Daniel-Calveras et al., Citation2022). Reasons, mechanisms and processes behind these numbers are important. They tell us what should be taken in to account when designing the targeted help for children affected by war. The understanding about the risk and protective factors as well as the dynamic processes that lead to psychopathology or good adjustment increases the possibilities of rightly timed and tailored help for all individuals.

Exposure to traumatic events and subjective feelings of threat

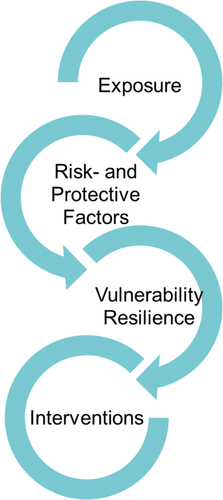

There are many individual horrific events in war, each of which alone would have the potential to traumatize a person, and, in the case of children and adolescence, threaten their development. These events include violence in its different forms: physical, sexual and emotional as well as insecurity and lack of basic needs (Annual Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict, Citation2005). Children respond differently into exposing events. Subjective perceptions, appraisals and interpretations of traumatic situations play a significant role in children’s stress reactions. That shows up as the differences in children’s reactions to objectively similar experiences. Exposure to multiple traumatic events during wartime can be seen as striking up the psychological processes that ultimately lead to different forms of adaptation, including the possibilities of both vulnerability and resilience (see ).

In the developmental perspective, the unsafe and threatening growth environment imposes significant demands on psychological resources, which may jeopardize the ability to manage age-typical developmental tasks. The adversities, such as coping with feelings of fear and threat as well as engaging in activities aimed at physical survival, can be thought as additional developmental tasks, that take up the resources that would otherwise be used in conquering age-typical developmental tasks. Ultimately, lack of safety and early life stress change the neurological- and immune systems (hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis and the autonomic nervous system), that enable the motivated psychological and behavioural responses to the environment. The altered activity of these systems is also associated with adverse mental and physical health outcomes following stress exposure (Berntson & Cacioppo, Citation2004; Danese & Lewis, Citation2017; Loman & Gunnar, Citation2010; McEwen, Citation2019).

Following the Social Safety Theory, Slavich et al. (Citation2023) point out how different psychosocial stressors influence the brain and body to shape health, development, and behaviour across the life course. They suggest that the loss, separation, and violent events that children experience in armed conflicts, lead to a loss of safety at multiple levels, ranging from the loss of individual feeling of being safe to being away from friends, homes, cities, and even countries. Importantly, these experiences contribute to a loss of cognitive schemas of social safety, affecting the appraisal of self, the social world, and the protected future. Especially, the separation from one or both parents has negative effects on children’s social-emotional development, well-being and mental health (Jones-Mason et al., Citation2019; Spaas et al., Citation2022; Waddoups et al., Citation2019).

The child’s developmental age determines what he/she perceives in a frightening situation and, on the other hand, how he/she interprets the situation, such as her own and other people’s actions in it, as well as the cause-and-effect relationships of the events. During early childhood (ages 0–6), rapid and numerous physiological, cognitive and emotional changes greatly impact on child’s perception and experience of traumatic events. Due to cognitive and verbal immaturity, self-focused perception, misunderstanding of cause-effect relationships and developmental-specific cognitive and emotional processes such as magical thinking, fantasy play and lack of autonomy, a child’s understanding of potentially traumatic events is affected. This also leads to limited ability to communicate emotions and thoughts about these events (Slone & Mann, Citation2016). Regarding the children in middle childhood, the study of Peltonen et al. (Citation2017) showed that among 10- to 12-year old children in Gaza, peritraumatic dissociation in war-time events (in other words the feelings of derealization and disconnection during the traumatic events) predicted higher levels of post traumatic stress nine months post-war. The significant part of this relationship was mediated via the quality of trauma-related memories (sensory-based and poorly verbalized memories).

Scharpf et al. (Citation2022) conducted a comprehensive study across conflict-affected regions, emphasizing the importance of understanding stress reactions within the context of social-emotional and cognitive development. Their research involved networks of sub-samples of 412 children (6–12 years) and 473 adolescents (13–18 years) living in various conflict-affected regions, such as Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Iraq, Palestine, Tanzania and Uganda. The results suggested that different reactions may be particularly important in different developmental stages, with avoidance and dissociative symptoms dominating in childhood, and intrusions and hypervigilance dominating in adolescence. Additionally, stronger connections between different symptoms among adolescents compared to children may render that adolescents are more vulnerable to the persistence of symptoms.

Risk and protective factors

Research have revealed multiple risk and protective factors among children exposed to conflicts and war. Trickey et al. (Citation2012) conducted a meta-analysis on risk factors for PTSD in children in general, highlighting that pre-trauma factors and objective measures associated with the event itself have small to medium effect sizes, whereas factors associated with the subjective experience of the event and post-trauma variables have medium to large effect sizes. These factors included perceived life threat during the trauma, thought suppression, low social support and social withdrawal as well as poor family functioning. Surprisingly, only small effects of trauma severity (as the objective measure associated with the event) and pre-trauma psychological problems in the individual and parent (as pre-trauma factors) were observed.

Regarding the war trauma especially, a systematic review of Daniel-Calveras et al. (Citation2022), concerning the mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors emphasized that low level of social support and poor quality of child-rearing environment (both in foster families and institutions) in the host country were associated with psychopathology. A thematic content analysis to written materials and narratives among 200 children at primary schools in refugee camps in the Gaza Strip revealed that the most severe self-reported risks were related to constraints on movement and affect balance, followed by relationship with family, and health (Veronese et al., Citation2017).

On the contrary, connection to spirituality (Cortes & Buchanan, Citation2007; Fernando, Citation2006), a sense of agency, social intelligence, empathy and affect regulation (Cortes & Buchanan, Citation2007) has been detected a protective factors against mental health problems. The qualitative material of Veronese et al. (Citation2017) showed that play, personal resources, relationship with other significant adults and school were perceived as protective factors among Gazan children. The girls in the sample reported more sources of protection than risks, conversely, whereas boys perceived themselves to be more at risk than protected.

Social support as a protective factor seems to play an important role among war exposed children. Spaas et al. (Citation2022) showed that refugee adolescents who reported more social support from the family and friends had higher scores of overall well-being and less emotional distress. The importance of close and intimate relationship was also evident in Peltonen et al. (Citation2014) study among children living in Gaza strip. On the other hand, in their study Punamäki et al. (Citation2018) showed that Gazan children who experienced insecurity and problematic relationships in their family showed higher levels of internalizing, externalizing and depressive symptoms and dysfunctional post-traumatic cognitions than children who enjoyed secure and supportive family relations.

Contributing to fundamental lack of safety schemas that were mentioned earlier, it is noteworthy that parenting capacities are challenged in the situations where the whole family and even community is affected by adversities. Eltanamly et al. (Citation2021) conducted a meta-analysis and qualitative synthesis of war exposure and parenting. The analysis showed that adjustment in highly dangerous settings can lead to hostility, inconsistency and less warmth among parents towards their children. This further contributes to the poorer well-being of children living in conflict-affected regions. However, the meta-analysis also showed that in settings where the threat is less severe, parenting may even contain more warmth towards the children. In other words, the perceptions of threat are important in parenting capacities. Being in a very high level, the feelings of threat jeopardizes the resources in parenting. Indeed, supporting parents in the times of war seems to be important. In their study among Syrian mothers Sim et al. (Citation2018) found that mothers’ perceived social support was associated with both psychological and parenting resilience in a context of ongoing conflict and displacement.

Vulnerability and resilience

Vulnerability to mental health disorders or resistance to them, resilience, develops in the interaction of risk and protective factors (see ). As described earlier, multiple pre-traumatic, peri-traumatic and post-traumatic risk variables contribute to the overall vulnerability of an individual regarding the later development of PTSD and other mental health problems.

A new diagnostic category, complex post traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD, WHO, Punamäki et al., Citation2018) reflects the meaning of cumulative adversity in well-being. It reflects the vulnerability of mental health and behaviour in the situation of multiple and/or prolonged traumatic events, and may constitute an important new concept also among the children in war. It captures not only the traditional symptoms of intrusiveness of traumatic memories, avoidance and changes in arousal, but also the problems in social relations, self-regulation and feelings of vulnerability. This means that in circumstances of many, repeatedly traumatizing experiences, the mental health and behaviour are at risk in many different ways.

The concept of resilience is fundamental in order to understand all sides of traumatic experiences in children’s lives. Ungar and Theron (Citation2020) suggest that resilience is best understood as the process of multiple biological, psychological, social and ecological systems, not just sum of individual factors. These processes interact with each other and eventually help individuals to regain, sustain, or improve their mental well-being. For example, the good cognitive capacity, as an individual factor cannot produce resilience unless there are societal structures, such as functional educational system to offer opportunities to utilize this capacity. Indeed, as Ungar and Theron (Citation2020) point out, studies in different fields of science confirm that resilience depends just as much on the culturally relevant resources as it does on individual thoughts, feelings and behaviours. This refers to characteristics and circumstances of a community, such as spaces within each community that offer opportunities for the health and well-being of community members. It also refers to values and perceptions of social-ecological systems and their interactions, reflected by how young people see themselves in connection with place over time. Contextual variables, found especially important in countries affected by war, include community traditions, rituals and spirituality (Cortes & Buchanan, Citation2007; Eggerman & Panter-Brick, Citation2010). According to Ungar and Theron (Citation2020), besides the screening of trauma-related symptoms in vulnerable populations, we also need the screening of these resources that are available to trauma exposed individuals, especially children, in their social, built and natural environments.

Many war trauma survivors also report experiencing post-traumatic growth (PTG), which Calhoun et al. (Citation2010) define as relating to others, new possibilities, personal strength, spiritual change and appreciation of life after traumatic events. As resilience also includes the definition of increased mental recovery and well-being, in other words, even better functioning capacity after traumatic events, compared to the time before it, PTG comes very close to this concept. But are the post traumatic stress and post traumatic growth mutually exclusive concepts? Kangaslampi et al. (Citation2022) found out that many Syrian refugees reported elements of PTG, even as they suffer from significant post-traumatic stress (PTS). The two phenomena appear distinct but positively associated, supporting the idea that intense cognitive processing involving distress may be necessary for growth after trauma. Indeed, the meta-analysis of Ferris and O’Brien (Citation2022), addressing multiple types of traumatic experiences among children, including medical trauma, war- and terror-related trauma, and environmental trauma, suggested that factors that impact the development of PTG include the presence of post-traumatic stress symptoms, specifically intrusiveness. More research on PTG among children and adolescents is needed, but the existing evidence may inform efforts to support refugee trauma survivors in finding meaning and perhaps even experience psychological growth after highly challenging experiences.

Interventions

Understanding stress reactions within the context of children’s and adolescent’s social-emotional and cognitive development gives us more tools to tackle the harmful effects of trauma. For example, Slavich et al. (Citation2023) highlight that especially in vulnerable and disadvantaged populations, the deeper understanding of stress biology can be used to reveal the biopsychosocial roots of lifelong health disparities, and consequently the treatment targets for reducing disease risk and achieving health equity.

Hiller et al. (Citation2016) meta-analysis showed that without any intervention there were moderate declines in children’s PTSD prevalence and symptom severity over the first 3–6 months post trauma. However, there was little evidence of further change in prevalence or symptom severity after 6 months. In other words, it is unlikely a child would lose a PTSD diagnosis without intervention beyond this point. Interventions for children affected by war should be multifaceted, resilience-focused and tailored to the needs of different subgroups and individuals, as emphasized by Nosè et al. (Citation2017) and Peltonen and Punamäki (Citation2010). A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis by Purgato et al. (Citation2018) found that focused psychosocial interventions among children are indeed effective in reducing PTSD and functional impairment, increasing hope, coping and social support also in low-resource humanitarian settings. The reviews are consistent in emphasizing interventions based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) in supporting the mental health of children exposed to war. The important notion is that these interventions are effective and safe also among children and adolescent with comorbid disorders (Nosè et al., Citation2017).

However, more research is needed to find out the multiple clinical aspects that take place in sometimes complex and long-lasting harmful situations experienced by war-affected children and adolescents. Interventions that are especially effective in treating C-PTSD among children exposed to war should be explored. More research is also needed to find out the benefits of interventions for different subgroups, especially for children and adolescents with different opportunities for family support during the intervention. Some children and adolescents do not have this fundamental protective factor with them, and we need to find out how to treat the traumas of those children too.

Finally, a participatory approach should find its way into trauma intervention research. The understanding of the mechanisms of traumatization and, on the other hand, the frameworks that enable the acceptance of the treatment from the perspective of children and adolescents is of outmost importance, and currently only happens during the feedback stage of treatment, not in its planning phase.

New solutions are also needed for the problems of equal access to mental health interventions in dangerous and damaged areas. Danese et al. (Citation2024) performed a scoping review to map existing digital mental health interventions relevant for children and adolescents affected by war. They found only one study evaluating digital mental health interventions for children and adolescents affected by war (and five for those affected by disasters). There were 35 interventions of possible relevance, but because most of them were not culturally or linguistically adapted to relevant contexts, their implementation potential remained unclear.

Conclusion

As we strive for a more peaceful world, addressing the needs of conflict-affected children remains a paramount concern. Children affected by armed conflicts endure significant challenges and vulnerabilities. However, their resilience and the potential for post-traumatic growth offer hope for their recovery and development.

Effective interventions to support child mental health and development, as well as a deep understanding of the factors that affect their effectiveness, are crucial in mitigating the long-lasting effects of conflict on these young lives. At the same time, the basic research of traumatic events in child’s cognitive and socio-emotional development must be broadened up.

We should be able to support organizations providing the mental health interventions in terms of flexibility in time needed for the treatment sessions, training and supervision. Both humanitarian and public health agencies support the integration of specialized treatments for conflict-affected populations into a multi-layered and multi-sectoral system of care, enabling the treatment of trauma-related but also other well-being problems simultaneously (Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), Citation2007; Wessels, Citation2017).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Annual Report of the Secretary-General on Children and Armed Conflict. (2005). (A/59/695 - S/2005/72). https://undocs.org/S/2005/72

- Attanayake, V., McKay, R., Joffres, M., Singh, S., Burkle, F., & Mills, E. (2009). Prevalence of mental disorders among children exposed to war: A systematic review of 7,920 children. Medicine, Conflict, and Survival, 25(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/13623690802568913

- Berntson, G. G., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). Heart rate variability: Stress and psychiatric conditions. In M. Malik (Ed.), Dynamic Electrocardiography (pp. 57–64). Blackwell Publishing.

- Blackmore, R., Gray, K. M., Boyle, J. A., Fazel, M., Ranasinha, S., Fitzgerald, G., Misso, M., & Gibson-Helm, M. (2020). Systematic review and meta-analysis: The prevalence of mental illness in child and adolescent refugees and asylum seekers. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(6), 705–714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.11.011

- Calhoun, L. G., Cann, A., & Tedeschi, R. G. (2010). The posttraumatic growth model: Sociocultural considerations. In T. Weiss & R. Berger (Eds.), Posttraumatic growth and culturally competent practice: Lessons learned from around the globe (pp. 1–14). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Cortes, L., & Buchanan, M. J. (2007). The experience of Colombian child soldiers from a resilience perspective. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 29(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10447-006-9027-0

- Danese, A., & Lewis, S. J. (2017). Psychoneuroimmunology of early-life stress: The hidden wounds of childhood trauma? Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews, 42(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2016.198

- Danese, A., Martsenkovskyi, D., Remberk, B., Khalil, M. Y., Diggins, E., Keiller, E., Masood, S., Awah, I., Barbui, C., Beer, R., Calam, R., Gagliato, M., Jensen, T. K., Kostova, Z., Leckman, J. F., Lewis, S. J., Lorberg, B., Myshakivska, O., … Weisz, J. R., & Affected Youth (GROW) Network. (2024). Scoping review: Digital mental health interventions for children and adolescents affected by war. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2024.02.017

- Daniel-Calveras, A., Baldaquí, N., & Baeza, I. (2022). Mental health of unaccompanied refugee minors in Europe: A systematic review. Child Abuse and Neglect, 133, 105865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105865

- Eggerman, M., & Panter-Brick, C. (2010). Suffering, hope, and entrapment: Resilience and cultural values in Afghanistan. Social Science & Medicine, 71, 71–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.023

- Eltanamly, H., Leijten, P., Jak, S., & Overbeek, G. (2021). Parenting in times of war: A meta-analysis and qualitative synthesis of war exposure, parenting, and child adjustment. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 22(1), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019833001

- Fazel, M., Wheeler, J., & Danesh, J. (2005). Prevalence of serious mental disorder in 7,000 refugees resettled in Western countries: A systematic review. Lancet, 365(9467), 1309–1314. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)61027-6

- Fernando, C. (2006). Children of war in Sri Lanka: Promoting resilience through faith development [ Doctoral dissertation]. University of Toronto.

- Ferris, C., & O’Brien, K. (2022). The ins and outs of posttraumatic growth in children and adolescents: A systematic review of factors that matter. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 35(5), 1305–1317. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22845

- Global Humanitarian Overview 2023. (2023). https://reliefweb.int/report/world/global-humanitarian-overview-2023-enarfres

- Hiller, R. M., Meiser-Stedman, R., Fearon, P., Lobo, S., McKinnon, A., Fraser, A., & Halligan, S. L. (2016). Research review: Changes in the prevalence and symptom severity of child post-traumatic stress disorder in the year following trauma: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 57(8), 884–898. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12566

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC). (2007). IASC guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support in emergency settings. IASC.

- Jones-Mason, K., Behrens, K. Y., & Gribneau Bahm, N. I. (2019). The psychobiological consequences of child separation at the border: Lessons from research on attachment and emotion regulation. Attachment & Human Development. 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2019.1692879

- Kangaslampi, S., Peltonen, K., & Hall, J. (2022). Posttraumatic growth and posttraumatic stress: A network analysis among Syrian and Iraqi refugees. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(2), 2117902. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2022.2117902

- Loman, M. M., & Gunnar, M. R. (2010). Early experience and the development of stress reactivity and regulation in children. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 34(6), 867–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.05.007

- McEwen, B. S. (2019). What is the confusion with cortisol? Chronic Stress, 3, 247054701983364. https://doi.org/10.1177/2470547019833647

- Mollica, R. F., Cardozo, B. L., Osofsky, H. J., Raphael, B., Ager, A., & Salama, P. (2004). Mental health in complex emergencies. Lancet, 364(9450), 2058–2067. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17519-3

- Nosè, M., Ballette, F., Bighelli, I., Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Tol, W., Priebe, S., Barbui, C., & Schmahl, C. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees and asylum seekers resettled in high-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 12(2), e0171030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171030

- Peltonen, K., Kangaslampi, S., Saranpää, J., Qouta, S., & Punamäki, R. L. (2017). Peritraumatic dissociation predicts posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms via dysfunctional trauma-related memory among war-affected children. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup3), 1375828. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1375828

- Peltonen, K., & Punamäki, R. L. (2010). Preventive interventions among children exposed to trauma of armed conflict: A literature review. Aggressive Behavior, 36(2), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20334

- Peltonen, K., Qouta, S. R., Diab, M., & Punamäki, R. L. (2014). Resilience among children in war: The role of multilevel social factors. Traumatology, 20(4), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099830

- Punamäki, R. L., Qouta, S. R., & Peltonen, K. (2018). Family systems approach to attachment relations, war trauma, and mental health among Palestinian children and parents. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(Suppl 7), 1439649. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1439649

- Purgato, M., Gross, A. L., Betancourt, T., Bolton, P., Bonetto, C., Gastaldon, C., Gordon, J., O’Callaghan, P., Papola, D., Peltonen, K., Punamäki, R. L., Richards, J., Staples, J. K., Unterhitzenberger, J., van Ommeren, M., de Jong, J., Jordans, M. J. D., Tol, W. A., & Barbui, C. (2018). Focused psychosocial interventions for children in low-resource humanitarian settings: A systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 6(4), e390–e400. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30046-9

- Scharpf, F., Saupe, L., Crombach, A., Haer, R., Ibrahim, H., Neuner, F., Peltonen, K., Qouta, S., Saile, R., & Hecker, T. (2022). The network structure of posttraumatic stress symptoms in war-affected children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry Advances, 3(1), e12124. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcv2.12124

- Sim, A., Bowes, L., & Gardner, F. (2018). Modeling the effects of war exposure and daily stressors on maternal mental health, parenting, and child psychosocial adjustment: A cross-sectional study with Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Global Mental Health, 5, e40. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2018.33

- Slavich, G. M., Roos, L. G., Mengelkoch, S., Webb, C. A., Shattuck, E. C., Moriarity, D. P., & Alley, J. C. (2023). Social safety theory: Conceptual foundation, underlying mechanisms, and future directions. Health Psychology Review, 17(1), 5–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2023.2171900

- Slone, M., & Mann, S. (2016). Effects of war, terrorism and armed conflict on young children: A systematic review. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 47(6), 950–965. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-016-0626-7

- Spaas, C., Verelst, A., Devlieger, I., Aalto, S., Andersen, A. J., Durbeej, N., Hilden, P. K., Kankaanpää, R., Primdahl, N. L., Opaas, M., Osman, F., Peltonen, K., Sarkadi, A., Skovdal, M., Jervelund, S. S., Soye, E., Watters, C., Derluyn, I., Colpin, H., & De Haene, L. (2022). Mental health of refugee and non-refugee migrant young people in European secondary education: The role of family separation, daily material stress, and perceived discrimination in resettlement. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 51(5), 848–870. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01515-y

- Trickey, D., Siddaway, A. P., Meiser-Stedman, R., Serpell, L., & Field, A. P. (2012). A meta-analysis of risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(2), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.12.001

- UN. (2022). United nations general assembly security council. Children and armed conflict. Report of the secretary-general. Retrieved June 26, 2024, from. https://childrenandarmedconflict.un.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Secretary-General-Annual-Report-on-children-and-armed-conflict.pdf

- Ungar, M., & Theron, L. (2020). Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30434-1

- Veronese, G., Pepe, A., Jaradah, A., Murannak, F., & Hamdouna, H. (2017). “We must cooperate with one another against the enemy”: Agency and activism in school-aged children as protective factors against ongoing war trauma and political violence in the gaza strip. Child Abuse and Neglect, 70, 364–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.06.027

- Waddoups, A. B., Yoshikawa, H., & Strouf, K. (2019). Developmental effects of parent–child separation. Annual Review of Developmental Psychology, 1, 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-devpsych-121318-085142

- Wessells, M. G. (2017). Children and armed conflict: Interventions for supporting war-affected children. Peace and conflict. Journal of Peace Psychology, 23(1), 4–13. https://doi.org/10.1037/pac0000227