ABSTRACT

In this paper, I carry out an analysis of an event in Sweden called ‘the spring turnout’. It is a traditional event where cows are allowed out into the fields after the winter. I show how it has been colonized by Arla Foods, the diary company which controls part of the milk production in Sweden and in many other countries. Of interest in this analysis is how Arla infuses the event, and its own marketing, with discourses about nature that are specifically Swedish and can be traced to the nation building of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, used systematically as part of the social democratic project for equality and progress through a strong welfare system. The paper examines how Arla recontextualizes these discourses for commercial purposes. I show how such recontextualized discourses carry reassurances to Swedish people that this project is still intact despite huge social political changes in Swede over the past decades embracing neoliberalism, global capitalism and becoming one of the fastest deregulating countries in the world.

Introduction

Each year throughout Sweden there are annual events called ‘the spring turnout’ when cows are released out of the barns into the fields after the long winter indoors. The event has symbolic meaning in Sweden as it signals the beginning of the summer and is deeply interrelated with Swedish national mythologies about nature and summertime. Over recent years the event has been appropriated by the dairy industry, specifically by one of the corporations which dominates milk production in Sweden, Arla Foods, one of the world’s largest milk producers. The spring turnout is now presented as a festival for families and has become infused with promotional and entertainments activities. In this paper, I explore how the event draws on specifically Swedish national discourses of nature. What is of interest is that these discourses, formerly fostered in times of nation building and related to the values and ideas of social democracy, equality, transparency and the centrality of the welfare state (Ehn, Citation1993), have now been recontextualized and redeployed for commercial purposes. Over the past decade, Sweden has been one of the fastest and most far-reaching de-regulating countries in the world (The Local Europe AB, Citation2012) with transformations taking place with little close monitoring across education, health-care and social services. The gap between the wealthy and the poor has also been growing rapidly in comparison to other OECD countries since the 1990s (OECD, Citation2017). Yet families can still experience the discourse of the old Sweden, of equality, transparency, simplicity in these spring turnouts as they can in much other food marketing and advertising more broadly. In this paper I am interested in how these older discourses of nationalism are recontextualized by Arla at this event; how these discourses, once used to build equality and welfare, have been harnessed by consumerism in recent decades, and ultimately, how they naturalize and gloss over fundamental changes in Sweden.

Critical Discourse Studies has been highly interested in the ideological uses of nationalism, for example to impose, establish or justify norms, meanings and decisions of political elites (see for example Amaya, Citation2007; Pavković, Citation2017); to cause benefits for some groups and to downgrade or marginalize others (for example Beldarrain-Durandegui, Citation2012; Gunders, Citation2012) including migrants (Krzyzanowski & Wodak, Citation2009) or as a reason for going to participate in wars which based entirely around economic interests (Graham, Keenan, & Dowd, Citation2004). There has also been an interest in more subtle and everyday forms of banal nationalism (Billig, Citation1995). This can take the form of the coverage of sporting events (Bishop & Jaworski, Citation2003) or commemorations and national holidays (Abousnnouga & Machin, Citation2013). Such banal forms are crucial for everyday naturalization of the nation, providing a background sense of its presence.

Since the 1990s the promotion of food products as ‘national’ has increased (Aronczyk, Citation2008; Ichijo & Ranta, Citation2016) – also a form of banal nationalism. Nations and their symbols are used in the discourse of ‘corporate nationalism’ as a means to link a brand to a national identity, and thus re-imagining, representing and reproducing the nation (Kania-Lundholm, Citation2014; Prideaux, Citation2009). Research has also shown that food can be promoted using appeals to nationalist associations of landscape and national pride (see for example Ichijo & Ranta, Citation2016). Likewise, researchers have pointed to how nature is used as an important rhetorical device in food advertising (Hansen, Citation2002; Salvador, Citation2011). However, we have less knowledge about how ‘nature’, in relation to ‘the national’, is implemented in nation-specific cases – how commercial representations of nature draw on locally specific political and cultural discourses and ideologies.

In this article, using multimodal critical discourse analysis (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012), I carry out an analysis of the spring turnout event. I reveal the discourses communicated through the recontextualization of setting, the promotional material, and the activities taking place. I ask what kinds of identities, ideas and values are communicated. My aim is to draw out this specific kind of banal nationalism which, I argue, has its roots in the national-building policies of the Swedish welfare state and the social democratic movement. It is a form of nationalism that is now recontextualized and redeployed for the purpose of consumerism and the naturalization of the neoliberal project. In what follows I begin by giving an account of the emergence of Swedish nationalism in the nineteenth and twentieth century and its relation to the construction of the Swedish welfare state and social democracy. I will also discuss the role of nature in this discourse of nationalism. I then move on to the research on food marketing and nature in order to allow me to point to the need to consider such processed in the context of unique specific national environments. I then look at the politics of the dairy industry in Sweden, which in itself has been related to and drawn upon ideas connected to the emergence of the Swedish welfare state. Finally, I go on to show how these discourses can be found in the spring turnout.

Swedish nationalism and nature

In Sweden, the nationalist movement of the early nineteenth century was, compared to other European nations, cultural rather than political. It was driven mainly by Swedish intellectuals. Like other nationalist movements, it used a notion of ethnic heritage but also focused uniquely on the cultural similarities transcending social class and regional identity (Facos, Citation1998). Later, progressive movements were to draw on these ideas within their reformative work, created by the need to address demographic shifts caused by industrialization and urbanization. In 1842, compulsory education was introduced based on the, at the time rather naïve, idea of common history and language without regard to social class or regional identity (Ehn, Citation1993; Facos, Citation1998). By the end of the century, the Swedish nation was still fragmented, characterized by class conflict and poverty. However, these ideas of equality were already taking form in social policy thinking.

When the Social Democrats came into power in the 1930s, a new stage of Swedification of the nation was initiated, evolving from three central concepts: democracy, citizenship and modernity. The welfare state was to be built and inhabited by modern individuals taking responsibility for the common future (Ehn, Citation1993). The Swedish national Romantic Movement, unlike in other European nations at this time, aligned itself with these views, protecting ‘Swedish’ values such as change, cleanliness, simplicity, and equality, still striving to preserve native traditions and values, in order to sustain a cultural continuity. The movement functioned, according to Facos (Citation1998, p. 3) as ‘a cultural and spiritual complement to Social democracy’, the latter determining the political, social and economic scene in Sweden almost to the end of the twentieth century.

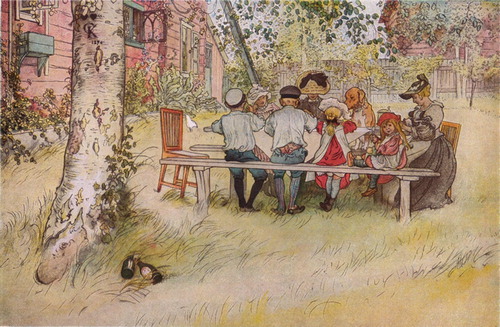

Since the end of the nineteenth century, the idea to associate democracy to Swedish nature and the Swedish landscape has been central to Swedish nation building. Nature was considered to constitute the basis of democratic nationalism (Werner & Björk, Citation2014) and Swedish nature and Swedish people as a nature-loving people became central discourses in the formation of a modern and democratic nation (Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994). Nature became represented through the idea of ‘openness’, ‘cleanliness’, ‘simplicity’, nature as being free of artifice and hence as something fundamentally equalizing (Ehn, Citation1993; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994; Werner & Björk, Citation2014). It was the Swedish landscape that had formed the Swedish character and temperament, and notions of Swedishness were produced within prose, poetry, architecture, design, portraits and landscape images (Facos, Citation1998; Werner & Björk, Citation2014). The Swedish landscape and scenes from the Swedish folk life represented typical themes: nature, the farmer and farmer culture, the season of summer, traditions, rituals and customs, and wooden panel buildings with the color of ‘falu-red’ or mansion yellow became key signifiers of Swedish national identity (Facos, Citation1998). Nature became appropriated by the white urban middle class for cultural reasons such as pleasure and leisure, singling out selected parts of Sweden in order to live authentic lives during the summer (Werner & Björk, Citation2014). Aquarelles such as Carl Larsson’s paintings of family life and rural socializing (see ) became virtually synonymous with the image of the nation (Carl och Karin Larssons släktförening, Citation2016).

Figure 1. ‘Breakfast under the great birch’ painted in 1896 by Carl Larsson (retrieved from Wikimedia common 2018-12-20).

The idea of nature as a salutary and benevolent space, of importance to Swedish urban citizens (Halldén, Citation2009; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994), has played a central role when framing nature as essentially Swedish. The importance of nature during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was not limited to Sweden and a Swedish context, but, compared to many other countries, the Swedish outdoor life became part of an everyday culture, characterized by a simplicity that crossed over class boundaries (Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994). If the nature in the nineteenth century was ‘idyllized’ and worshiped, the nature in the 1930s, 1940s and the 1950s was set forth as ordinary, practical and of use to Swedish, democratic citizens both as a source of raw material and as a recreational resource (Ehn, Citation1993; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994). Nature became synonymous with notions of public health and well-being (Halldén, Citation2009; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994) and depicted as central in a modern and active (urban) life. Outdoor activities such as biking, hiking, skiing and camping were considered as having restorative powers and vitalizing effects (Ehn, Citation1993; Werner & Björk, Citation2014).

An important element of images of nature is the connection between nature and children. This connection, central to representations in the Romantic era, the child as free in nature, became core to the Swedish national discourse (Halldén, Citation2009). Nature and outdoor life were central ideas in the educational discourses implemented as part of the modern Swedish (social democratic) welfare state (Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994). Generations of schoolchildren were, and are, tutored to have a specific interest in animals and nature through school trips, excursions and literature (Mårald & Nordlund, Citation2016; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994). From early years children are, in the context of the ‘open-air movement’, taken out into the forests as part of the weekly routine as part of engaging with nature (Halldén, Citation2009, Citation2011). Specifically Swedish representations of nature are also common in children’s literature throughout the twentieth century, often, as in the books of Astrid Lindgren, connected to an innocent and carefree childhood in the Swedish countryside represented through common tropes of openness, equality, simplicity (Andersson, Citation2008). Such representations echo across media for both children and adults in movies (Wright, Citation1998), photo books, post cards, tourist brochures and television (Mårald & Nordlund, Citation2016).

Nationalism and nationalist expressions have been contested in the twentieth and the twenty first centuries in a Swedish context. In the early 1900s, Sweden had an obsolete monarchy and a conservative nationalism that both faced strong opposition, especially from the working class who considered themselves to be internationalists and modernists. National symbols such as the Swedish flag, memorial stones and statues were questioned because they were associated with conservative traditions and the upper classes (Ehn, Citation1993). In recent years, we see that civic nationalism has been challenged by a strong emerging ethno-nationalism characterized by ideas of cultural conformity and social cohesion based on a new model of ‘Swedishness’. This is found in discussions in Swedish politics and in news media, that have dealt with nationalism and nationalist expressions in relation to multiculturalism, globalism, integration, segregation, and ‘good’ and ‘bad’ nationalism, for example when and how to use the Swedish flag (Hellström, Nilsson, & Stoltz, Citation2012). At the same time, the role that nature plays in Swedish national identity has remained largely unchanged, in turn giving the sense that the pureness, openness, and fairness remains a core value of this new ‘Swedishness’. While Sweden since the end of the twentieth century can no longer be described as being based on social democratic principles (Ryner, Citation1999), the discourses of nature related to Swedish identity and discourses of social democracy remain. The Swedish self-image is still based on Sweden as a modern and progressive nation (Andersson & Hilson, Citation2009), of which the sense of nature and beautiful landscape is an important part (Järlehed, Citation2015). In nation branding documents and political strategy documents, we find still find discourses characteristic of the twentieth century welfare state. Sweden is still described as an open, free and prosperous society but this sits alongside a new discourse found in the lexis of ‘innovation’, ‘sustainability’ and ‘co-creation’. Core values such as openness and authenticity, and equality and equity are still set forth as being fundamental characteristics of Sweden (Government Offices of Sweden, Citation2017); Swedish Institute & Ministry for foreign affairs, Citation2017). And, as I show in the case of Arla’s version of the spring turnout, these discourses can also reassure Swedish people that despite rapid neo-liberalization, deregulation and dismantling of the welfare state, Sweden is, at heart, how it has always been.

Food promotion, banal nationalism and nature

Food, food writing, food production, food distribution, food consumption and food promotion are intrinsic parts of everyday lives (DeSoucey, Citation2010; Ferguson, Citation2010; Kania-Lundholm, Citation2014; Palmer, Citation1998). Research has long established how food products are branded to create differentiation and nature and nationalism have been an important part of this process (see for example Ichijo & Ranta, Citation2016). However, nationalist company advertising in general and the promotion of food specifically, have seldom been studied in this context (Ichijo & Ranta, Citation2016; Prideaux, Citation2009). Nevertheless, as Prideaux (Citation2009, p. 617) states, ‘ … commercial expressions of nationalism constitute a “daily reminder” of a person’s belonging to a particular nation’. Food branding and food marketing are therefore to be understood as practices by which ‘banal nationalism’ (Billig, Citation1995) is constructed and reproduced.

In advertising in general, nature is often represented as intrinsically good (healthy and fresh), a nice place to be and/or as a space for human recreation – especially for ‘the stressed city-dweller’ (Hansen, Citation2002, p. 507). In food promotion, nature is often put forward as practical or agricultural, making life easier to human kind and representing spaces as useful and available to humans (Salvador, Citation2011). Of course ‘nature’ and ‘the natural’ function here as ‘key rhetorical devices of ideology’ (Hansen, Citation2002, p. 136). They hide certain interests and, at the same time, make claims, relying on mutually constructed and shared ideas about nature (Hansen, Citation2002; Soper, Citation1995). For example, highly industrial processes, globalization, unethical manufacturing, can be entirely backgrounded.

Food marketing representations of nature can also, according to Hansen (Citation2002), connect a romantic view of nature with a rural and idyllic past with national identity. Soper (Citation1995, p. 193) terms this the ‘patriotic greenery’ – an idealization of nature and rurality used by multinational companies in marketing. Studies have shown that nation and nationality are used to identify when to sell healthy foods (Hiroko, Citation2008), native foods (Craw, Citation2008) or products which draw on some kind of romantic national/ ethnic associations, such as Irishness (Negra, Citation2010) or Turkishness (Ogan et al, Citation2007). Food, nation and nationality are used either to promote a particular food product by linking it to a certain nation or as a way to differentiate foods and food cultures from each other. Either way, the nationalist framework is deeply connected to the globalization of markets and the need to profit on differentiation (Ichijo & Ranta, Citation2016). However, so far, much less is known about representations of nature in ways that are nationally and culturally specific and how these are used to articulate and reinforce nationally and culturally specific identities, which is my interest in this article.

Dairy marketing in the twentieth century

Nationalism and nature have been central in the marketing of dairy products in Sweden. In most western societies during the 1920s and 1930s, dairy marketing projects were connected with the construction of the modern nation. Often, as in Sweden, this was intertwined with political ambitions to improve both the rural economy and public health (Martiin, Citation2010). In the 1920s milk propaganda in Sweden positioned milk within contemporary scientific and health and hygiene discourses. Dairy products were framed as ‘modern commodities for contemporary people’ (Martiin, Citation2010, p. 220) and built on ideas of naturalness and goodness mainly due to nutritional content (Jönsson, Citation2005).

In the discourse of health, hygiene and bodily perfection, the whiteness of milk was in itself foregrounded. Whiteness was considered a symbol of modernity, purity, hygiene, progress, order and social status (Jönsson, Citation2005; Torell, Citation2005) and as such associated with the white body. Milk branded as hygienic – white and clean in opposition to the often unsanitary conditions that characterized much of everyday life at the time (Martiin, Citation2010), became also a means to propagate the superiority of the white race. The north European white body was described as capable of digesting lactose unlike people from other countries and with other ethnicities; successful in science, trading, art and literature as well as having a low child mortality rate were all phenomena that became connected to milk consumption as part of milk propaganda (DuPuis, Citation2002; Jönsson, Citation2005).

In line with the welfare state’s idea of promoting health and removing socio-economic differences, free school meals were introduced in Sweden in 1946. The purpose was to give all children, regardless of socio-economic background, equal access to schooling. Milk became an important part of these free meals based on its nutritional content (Jönsson, Citation2005). Now, Sweden still has statutory requirements for free and nutritious school meals for students, regardless of income. The goal of promoting health and addressing socio-economic differences is still given as the reason underpinning free milk. Milk has thus long been linked to children, children’s health, modernity and equality in a Swedish context.

Today, the notion of ‘natural goodness’ based on nutritional values still plays an important part in milk marketing in Sweden. Health is communicated as the main value of milk and, at least by Arla, milk is still framed as part of a healthy lifestyle. However, in recent years, the dairy industry has to some extent abandoned the scientific health discourse in its marketing, as it can easily be challenged. The milk industry has also had to relate to a growing environmental movement as well as to the marketing of alternative and vegan products in the beverage market. Products such as Oatly have positioned themselves against milk where the environmental (and health) effects of replacing dairy products with oat-based foods are emphasized (Fuentes & Fuentes, Citation2017). Currently, Arla mainly capitalizes on romantic representations of the production process: the farm is represented as an idyll , the dairy environment as ‘peaceful and natural’ and the cows as ‘happy cows’ (Linné, Citation2016). And as I point out in this article, Arla seeks to signal that milk production and milk consumption, in addition to the milk product itself, can be seen as infused in a social democratic version of Swedish nationalism.

Data and methods

Arla used to be a national dairy cooperative, but since 2000 and several merges it has become a global dairy company with production facilities in 17 countries and sales offices in a further twenty. Today it is one of the world’s largest dairy companies (Arla Foods, Citation2016). The paper draws on data collected during two of the company’s two-hour long marketing events on 9th of May, 2015 and 5th of May, 2016 in Sweden. Since the beginning of 2000, Swedish Arla dairy farms invite the public to take part in the spring turnout: the moment when the farmer turns his or her cattle out into the pasture after the winter. It is a traditional event that has become a popular entertainment for the urban citizen. The spring turnout, framed by the company as a ‘festival’, attracts approximately 5000–10 000 visitors to the farms located closest to the big cities and more than 150 000 visitors to all of the attending farms (Arla Foods, Citation2015).

The two chosen dairy farms are situated in the middle of Sweden. In order to generate data I have used an ethnographic approach: I attended the event, took field notes, photographs and used video to capture some of the movements of the participants.

The data consists of notes, photographs and visual recordings of the settings; participants and their actions; signs (text and images) and objects available at the locations. In this study, I have chosen to focus my analysis on the objects that Arla had placed on the site during the event, for example signs, plastic barrier tape, an inflated plastic cow, a photo wall, a face painting booth and a food stall, as well as the visitors’ performances and actions in relation to these objects. However, this also includes taking into account objects already present in the environment such as buildings and natural elements. I have also used data from the 2017 and 2018 versions of the Swedish Arla website – texts and images – to broaden my understanding of the corporation, its brand, core values and sales strategies.

The study is placed within the field of semiotic landscapes: the understanding of landscapes as a way of seeing, the interest in spatialization, the processes by which space comes to be organized, represented and experienced, and the emplacement of signs as an ideological act (Jaworski & Thurlow, Citation2010). Of importance to the study is the ‘in place’ aspect of meanings of discourses and the meanings of actions among those discourses, and concepts such as indexicality and double indexicality (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). All signs, i.e. material objects that refer to something other than themselves, take some of their meaning from how and where they are placed in the material world (indexicality), as well as from the interaction with other signs in that environment (double indexicality). The meaning of a sign must always be understood from where it is placed and in relation to other signs in that place. At the same time, each of these signs indexes an overall discourse (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). Similarly, we can understand actions as having meaning based on the context in which they take place (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003; Thurlow & Jaworski, Citation2014). They also foreground some meanings and background others, since an action positions the actor as a person who selects among meaning potentials (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003).

The interpretative framework, in turn, draws on principles of Multimodal Critical Discourse Analysis (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012). Using conceptual tools from social semiotics (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006; Van Leeuwen, Citation2005) and from its three-dimensional analysis of material artifacts (Abousnnouga & Machin, Citation2013; Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006), I have sought to identify what semiotic choices have been deployed at the Arla events and how these choices create meaning. This meaning is based on how different modes and the resources comprising these modes are used in current and previous uses (Van Leeuwen, Citation2005). In signs (images and texts) these choices include choices of elements as participants, settings, actions and objects, as well as the resources of writing, color and composition (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006). When it comes to material artefacts, these choices mean design, for example certain materials, elevation, angle of interaction, size, shape and color (Abousnnouga & Machin, Citation2013). In the embodied interaction, that is, the visitors’ interaction with objects in place representing the brand, the choices include the movement of bodies and body parts: walking, body posture, head movements and gestures (Thurlow & Jaworski, Citation2014).

Semiotic resources are not restricted to designing, writing or picture making, instead almost everything we do could be regarded as realizations of social and cultural meanings (Van Leeuwen, Citation2005). The choice of semiotic resources and their combination in relation to emplacement reveal interests, values, attitudes, ideas and/or perspectives of the people making these choices. Strategies that are used in the production of actions, texts, images, design and/or objects are known to be ideological and used to shape the representations of events, actions, persons and settings for particular ends (Machin & Mayr, Citation2012; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). The aim of the analysis is to understand how the semiotic activities of Arla at site represent and reproduce discourses that, in a Swedish context, are connected to a deeply rooted nationalist myth about Sweden as a (or the most) modern and progressive nation (Andersson & Hilson, Citation2009; Glover, Citation2009), and the Swedish nature as an democratic, open, free and equal space suitable for children and children’s play (Andersson, Citation2008), physical activity (Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994) and rural socializing (Werner & Björk, Citation2014).

Swedish nature as well-managed space

‘Nature’ plays a considerable part in building the brand of Arla milk. The concept ‘Closer to Nature’ (Arla Foods, Citation2018) has a central position in the marketing of its products and ‘nature’ is consequently highly present in the promotional material at the turnout event as well as in the choice of locations. The texts, images and objects used to structure the event, represent and organize space in a way that enables nature to be framed as essentially Swedish – modern, progressive, orderly and clean – and align the brand with this discourse.

Nature is, in the promotional material, its language and iconography and by choice of event and location, presented as a practical and controlled nature, domesticated and customized to its users (Salvador, Citation2011), the producers and the consumers of milk. We find clean and tidy cultivated fields, modern tractors and combine-harvesters, thoroughly well-kept barns and, as shown in , close-up images of farmers and cows. All this indicates a well-managed and modern agricultural nature, controlled by the milk producing farmers. Milk is promoted as a ‘Nature’s own sports drink’ [SW: Naturens egen sportdryck] and the utilization of nature is referred to, as in , as ‘world-class farming’ [SW: ett lantbruk i världsklass].

Figure 2. Sign: ‘We are Arla – and we have something important to tell you’/’Vi är arla – och vi har något viktigt att berätta’ (2016-05-05)

The impression of control, order and cleanliness is enhanced by the staging of the event. A carpark has been created on a nearby field and attendants dressed in yellow vests with a brand symbol printed on the back, guide the cars. The farmyards are clean, plastic bands separate frontstage from backstage, signs inform parents to look after their children and at the 2016 event, a sign reminds the visitors of the importance to disinfect and wash their hands after being in contact with the animals.

In addition to producing an image of a modern and well-managed organization, the use of regulatory discourse creates a space of control and order. The mode of control has been central in the Swedish marketing of dairy products since the emergence of the Swedish welfare state, often expressed, as with Arla, in terms of safety, cleanliness and good hygiene (Jönsson, Citation2005; Martiin, Citation2010). Milk is promoted as nature’s product, but also as a source of raw material. Swedish nature is strictly controlled and well maintained.

As space, nature is also explicitly located within the borders of the nation. It is identified as Swedish and categorized, as in , as ‘open landscape’ [SW: öppna landskap]. A national iconography is central in the representations found at the site. Visual elements used metonymically in signs and on milk packages at the event, are present in their material forms at the locations, bringing together a familiar iconography of the Swedish countryside and Swedish summer. The falu-red wooden panel wall, connoting the unchanging countryside for Swedish people, the green pasture with yellow dandelions or yellow buttercups, blue skies and white clouds, sunshine, cows, the blue and yellow Swedish flag, the farmer, a tractor, butterflies and trees, are at the actual farms manifested and situated in their presumed natural context – the agricultural, open and above all, Swedish landscape. The signifiers function as a common language, well-known to Swedish consumers, due to previous representations of nature in films, art and literature (Facos, Citation1998; Mårald & Nordlund, Citation2016; Wright, Citation1998).

The idea of nature as a salutary and benevolent space for urban citizens (Halldén, Citation2009; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994) also plays a central role when framing nature as essentially Swedish at the turnout. In press releases, the visit is presented as an opportunity for “Swedish families” to welcome spring together with the cows and the farmers (Arla Foods, Citation2013); a corporal response to the urban citizen’s longing for a closer relationship with nature and animals (Arla Foods, Citation2015). The farmyard is accordingly spatially organized in relation to that longing, enabling contact with nature and an interaction with ‘the natural’. Arla provides the opportunity to pet calves, to look into the barn, to have a picnic in a field and, as the invitation to the event says, to see the cows’ leaps of joy.

The staging of the event and its transformation of space also highlight the culturally shared value of nature in relation to recreation, rural socializing and children’s well-being (Halldén, Citation2009; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994). The farmyard is presented as a space appropriate for sharing a picnic, physical activity and children’s play. At arrival, Arla provides the visitors each with a carton of milk and a typically Swedish cinnamon bun. Further into the area, different materializations of company symbols transform the farmyard into a display of calves, a quiz walk and a children’s playground. The latter, shown in , contains a face painting booth, a photo wall and a huge inflated red and white plastic cow, a brand symbol meaning the product being 100% Swedish from Swedish Arla farms.

The appropriation of the event enables Arla to strengthen the values that are attributed to the product of milk as being ‘Swedish’, which is a product based in nature – clean, safe and hygienic, produced by a modern and well-organized dairy practice deeply rooted in the Swedish landscape. The emplacement of the promotional materials gives weight to the argumentation. The place and its signifiers connect the values represented by the promotional materials to the values imbued in the location in the particular moment, and by that giving authenticity to the brand and its promotional claims: the place representing the essence of something (Van Leeuwen, Citation2005), in this case, the qualities of the product, the brand and even the global corporation itself. But more important the appropriation of the event and the use of the actual farms and locations also enable the dairy company to act as a benefactor, connecting the Swedish urban consumer, especially the child, with nature. This aligns with the notion whereby the early-school children are taken out into the forests as part of the ‘open-air movement’ to be in nature, to experience nature as well as to learn about nature (Halldén, Citation2009, Citation2011). Arla is thereby able to capitalize on the national myth of a beneficial nature and the value of taking part in an outdoor life at the countryside and in its traditions. The event itself becomes ‘traditionalized’ (Storey, Citation2001, p. 79), and used in the marketing practices of Arla to make visible, and guarantee the national and the cultural values of the product and the global company.

Children in Swedish nature discourses

The child is of particular importance at the Arla events, and as such linked both to Swedish nature and the promoted milk product. This relates to the children present at the event as well as the children represented in the promotional material.

In the commercial appropriation of the spring turnout, Swedish nature is represented as central for a good childhood and a healthy upbringing, yet with a nationalist key signature. More widely discourses of childhood have been shown that the child as a sign represents values that have different meanings at different times and in different social situations (Gittins, Citation2008). Childhood spaces are never to be understood as neutral locations (Jenks, Citation2005). The interpretation is usually constituted by the child’s placement in space, where nature or the home environment are regarded as good and proper spaces (Jones, Citation1999; Gittens, Citation2008). In a Swedish context, nature is not just considered a proper or idyllic setting for children’s play and health (Jones, Citation1999); instead it is regarded a symbol for a good childhood (Halldén, Citation2009). The children physically present at the event, petting calves, getting their face painted and drinking Arla-milk, are all placed in nature. The same associations operate with the children represented in –, where we see a child placed in a rural setting during spring or summer time.

These representations bring associations, such as those by Astrid Lindgren, for parents of children’s stories where children are represented as free and innocent in the idyllic and open countryside (Andersson Citation2008). On one of the signs at the event, shown in , the children are also placed at a close distance to a calf. A girl and a boy hold on to a rope connected to a calf’s halter. The girl has her other hand placed on the calf and her gaze directed towards it. The innocence of the girl exhibits a physical as well as a symbolic connection with nature. Nature functions in these images, as well as at the event, both as a space of a good childhood and as a symbolic space, a synthesis of nature and childhood, that are set within the borders of the nation.

Gender is important in itself in this representation of children at the events. Childhood, and especially girlhood, has become associated with values such as purity, innocence and transitoriness, an understanding connected to the rise of the (white) middle class in the western societies (Duncan, Schein, & Johnson, Citation2004). Girlhood in relation to Swedish nature and nationalism are of special importance in Arla’s promotional material. In and , girls are shown to be associated with purity through their proximity to milk and placement in nature. The girl’s purity and innocence, but also health, and something natural and fresh, are the same attributes used to describe milk. It has been argued that certain types of people such as war heroes or sports athletes are used to symbolize or embody the nation (Storey, Citation2001). But here too the young girl is used in a similar way. She symbolizes the cultural and traditional values of the company and the milk production process.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Swedish milk girl, around the age of 11–12 years, distributed the milk to consumers (Arla Foods, Citation2017) . Today the milk girl still symbolizes such tradition and cultural continuity, but she also personifies and embodies the qualities of the product and its national origin. Milk, the natural goodness, is in and visually equated with the young girl, the embodied version of another kind of natural goodness (James et al, Citation1998). Besides creating associations between milk and children, the values of the product and its national origin are in these representations reflected through the fairness of the child, the emplacement in the Swedish countryside and the national signifiers surrounding her such as the wooden panel wall painted in Falu-red, the Swedish cinnamon bun and the yellow buttercups.

If the young girl and the signifiers surrounding her represent values associated with the Swedish national Romantic Movement such as authenticity, purity, tradition and cultural continuity, the representation of the boy and his surroundings are used to symbolize more modern values of national relevance such as cleanliness, progress and equality. The boy, as a sign in the Arla imagery, is often placed at a further distance from nature than the girl. He is either depicted as a bystander observing the girl’s close relationship to nature as in or within the home environment or on the football field as in . In , read from left to right, the images form a narrative (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006): a boy holds a glass of milk; he drinks the milk and in the last image, a pair of legs and feet are shown, dribbling a football. The process of drinking is expressed with the onomatopoetic words GULP, GULP/ KLUNK, KLUNK and the process of scoring goals is replaced by the nominalization: GOAL, GOAL/MÅL, MÅL.

The narrative in visualizes benefits of the healthy and nutritious product other than being natural, namely the successful outcomes. Outcomes that are of importance to the modern welfare state and part of a long-standing nationalist narrative, namely the individual working hard and taking care of their body for the benefit of the nation (Ehn, Citation1993; Sandell & Sörlin, Citation1994). This middle-class, gendered version of childhood, the whiteness of the home setting, a guitar on the wall, the father sitting next to the boy at the kitchen table and the football shoes, white socks and white shorts, contextualizes the active boy within an urban life style. The product in these images is related to boyhood and values such as activity, success and achievement. The whiteness in the images connotes modernity, style and light, but symbolizes also older values of national relevance such as simplicity and cleanliness. The placement of the father next to the boy in a domestic kitchen creates an impression of gender equality, also a key discourse in Sweden. The brand slogan building strong legs/bones are illustrated through the narrative and the pair of legs; the body linked to a coveted form of efficiency within sports, namely scoring goals. Still, the values are contextualized within the borders of the nation. In the middle of the narrative, the inserted product brand – the red and white Arla cow – ensures the content of the product, as well as the narrative, to be 100% Swedish.

Doing being a good Swedish parent

The promotional communication at the event has also has a quasi-didactic form to educate the parent in how to nurture the child. Nature is represented as a moral space where the value of nature (and the natural) is associated with an appropriate childhood, good parenting and an ideal family life in which milk as a healthy food product plays a main role. The salutary effects of nature in relation to physical activity, play and rural socializing are central in this connection.

According to Arla (Citation2015), parents visiting the event express a wish to show their children where the food and milk comes from. In part, the event is framed as a way of satisfying this educational desire. The spring turnout is staged like a spectacle, appropriate for visual consumption, organized as a platform event (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). The visitors gather around the pasture in order to enjoy the cows jumping, butting and running around. In the 2016 event, a parent standing behind me clarified to his child the connection between the milk that had been handed out at the entrance of the farm and its origin. He said to his child pointing at the cows: ‘the milk that you just drank came from these cows!’ [SW: mjölken som du precis drack kom från de där korna!]. From a nationalist perspective, he is doing ‘being a good parent’ by taking part in the educational tradition of teaching the child about Swedish nature (Mårald & Nordlund, Citation2016), in this case in relation to nature as a food source. From a commercial perspective, the parent also creates a desirable association between the product, the behavior of the cows and the specific location and time to the consumer to-be.

The placement of the promotional materials at the farm – a quiz walk, a face painting booth, a photo wall and a huge inflated cow – also enables ‘good parenting’, reproducing the nationalist narrative of a playful and healthy childhood at the Swedish countryside (Andersson Citation2008; Halldén, Citation2009, Citation2011). The activities are designated for younger children and milk is placed once more in the center of the argumentation. The huge, inflated plastic red- and white brand symbol, shown in , carries the same kind of modality configuration found in toys for young children (Kress & Van Leeuwen, Citation2006). The eyes consist of two red and white dots, the mouth is a curved line and the cow is brightly colored. The shape of the cow is slightly rounded. It is big and salient but placed and designed in a way that encourages children to approach and touch. The actions of the children are oriented towards the plastic cow: they walk under it, jump into it, pet it, move around it and stand next to it. Shapes, colors and texture are child-oriented and fun, suggesting play. The placement and the design of the cow in relation to the actions of the children enable a connection between the product brand, 100% Swedish milk from Swedish Arla farms, the slogan building strong legs/bones and physically active children. The idea of health, play and nature, initially connected to nationalism, industrialization and modernization (Halldén, Citation2009; Mårald & Nordlund, Citation2016) are reproduced by the workings of dairy capitalism.

The outdoor meal, in this case the picnic, could also be understood in relation to an ideal Swedish family life. As a cultural and national phenomenon it has been visually represented previously, for example in Breakfast under the great birch painted in 1896 by Carl Larsson (see ). shows visitors at the 2015 turnout, either sitting on blankets in the grass or standing next to each other, socializing, drinking milk and eating their Swedish cinnamon buns. Nature in these representations is perceived and experienced as a space for human recreation (Hansen, Citation2002). Its beneficial and socially valuable character is made manifest by the visitors in family groups forming semiotic units, their attention directed towards each other (Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003), sitting down and enjoying each other’s company.

Parents, grandparents and children sharing an outdoor meal, drinking milk and eating cinnamon buns, thus representing the values associated with an ideal Swedish family life in relation to nature and everyday culture; the outdoor picnic communicating simplicity and social equality. The visitors are encouraged to perform and experience both good childhood and good parenthood; enjoying the restorative and vitalizing powers of nature (and milk) together. They are thus doing being Swedish (Pfister, Citation2008).

Conclusion

In the twentieth century, the social democratic movement harnessed and fostered particular discourses of nature as part of a nation building project based around equality, transparency and a strong welfare state which would be part of working against poverty. The result of this project is what many people around the world politically and socially still associate with Sweden, along with the speeches of Olof Palme against global injustices. Since then, Sweden has undergone massive changes, taken on the neoliberal ideologies now dominating much of the world. Yet to some extent in Sweden such dramatic shifts, happening before our eyes in education, in welfare, immigration and taxation policies, go less noticed. Signifiers of the old Sweden, taking the form of nationalist discourses of nature, tend to gloss over these shifts. By approaching the spring turnout and its meaning production from a social semiotic and ‘in place’ perspective and thereby unraveling the discourses in place, recontextualized and reproduced through the commercial design of signs, objects and space, the visitors’ performances as well as the location and its natural elements, it becomes clear how Arla’s communicative work during the event contributes to both maintaining and fueling the image of the ‘old Sweden’. Banal settings like these are infused with familiar reminders of the Swedish values of openness, equality and the simplicity of the message of modernity and structurally organizing to make things better. Commercial activities are now able to recontextualize and therefore colonize discourses of justice and social democracy to sell products. The question is how do Swedish citizens now relate to, and act, in respect to such discourses. Certainly all this acts in the favor of those who wish for Sweden to continue on its present trajectory. While visiting the spring turnout, or taking milk in our coffee, we can be reassured that the welfare state is still in good health.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Professor David Machin at Örebro University, Sweden for his valuable comments and recommendations on this paper. I would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributors

Helen Andersson is a Senior Lecturer in Media and Communication Studies at Örebro University, Sweden. Her research interests include food communication, nature, multimodality and critical discourse analysis.

ORCID

Helen Andersson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5051-7804

References

- Abousnnouga, G., & Machin, D. (2013). The language of war monuments. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Amaya, H. (2007). Latino immigrants in the American discourses of citizenship and nationalism during the Iraqi war. Critical Discourse Studies, 4(3), 237–256. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ufh&AN=27342564&site=ehost-live. doi: 10.1080/17405900701656841

- Andersson, M. (2008). Borta bra, men hemma bäst? Elsa Beskows och Astrid Lindgrens idyller. In M. Andersson & E. Druker (Eds.), Barnlitteraturanalyser. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Andersson, J., & Hilson, M. (2009). Images of Sweden and the Nordic countries. Scandinavian Journal of History, 34(3), 219–228. doi: 10.1080/03468750903134681

- Arla Foods. (2013). Välkommen till vårens lyckorus på Arlagårdarna [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.arla.se/om-arla/nyheter-press/2013/pressrelease/vaelkommen-till-vaarens-lyckorus-paa-arlagaardarna-854882/2018-09-19.

- Arla Foods. (2015). Fler kosläpp än någonsin när Arla firar 100 år som kooperativ [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.arla.se/om-arla/nyheter-press/2015/pressrelease/fler-koslaepp-aen-naagonsin-naer-arla-firar-100-aar-som-kooperativ-1146843/2017-12-21.

- Arla Foods. (2016). Vårt ansvar. Corporate Responsibility Rapport. Retrieved from https://www.arla.com/company/responsibility/csr-reports/2017-12-21.

- Arla Foods. (2017). Mjölkflickan tjänade 7.50 i veckan. Retrieved from https://www.arla.se/om-arla/bondeagda/arlas-historia/manniskorna/mjolkflickan/2018-01-03.

- Arla Foods. (2018). Kvalitetsprogrammet Arlagården®. In (5.4 ed., pp. 1–69). Retrieved from https://www.arla.se/globalassets/om-arla/vart-ansvar/kvalitet-pa-garden/20180101-kvalitetsprogrammet-arlagarden-v.-5.4-januari-2018-se.pdf2018-01-04.

- Aronczyk, M. (2008). ‘Living the Brand': Nationality, Globality, and the Identity Strategies of Nation Branding Consultants. 2008, 2. Retrieved from http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/218

- Beldarrain-Durandegui, A. (2012). We and them rhetoric in a left-wing secessionist newspaper: A comparative analysis of Basque and Spanish language editorials. Critical Discourse Studies, 9(1), 59–75. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2011.632141

- Billig, M. (1995). Banal nationalism. London: Sage.

- Bishop, H., & Jaworski, A. (2003). ‘We Beat ‘em’: Nationalism and the hegemony of homogeneity in the British press reportage of Germany versus England during Euro 2000. Discourse & Society, 14(3), 243–271.

- Carl och Karin Larssons släktförening. (2016). Carl Larsson. Retrieved from http://www.carllarsson.se/carl/2018-05-23.

- Craw, C. (2008). The Flavours of the Indigenous: Branding Native Food Products in Contemporary Australia. Sites: A journal of social anthropology and cultural studies, 5(1), 41–62.

- DeSoucey, M. (2010). Gastronationalism. American Sociological Review, 75(3), 432–455.

- Duncan, J. S., Schein, R. H., & Johnson, N. C. (Eds.). (2004). A companion to cultural geography. Oxford: Blackwell.

- DuPuis, E. M. (2002). Nature’s perfect food: How milk became America’s drink. New York: New York University Press.

- Ehn, B. (1993). Försvenskningen av Sverige: det nationellas förvandlingar. Stockholm: Natur och kultur.

- Facos, M. (1998). Nationalism and the Nordic imagination: Swedish art of the 1890s. Berkeley, CA: Univ. of California Press.

- Ferguson, P, Parkhurst. (2010). Culinary Nationalism. Gastronomica, 10(1), 102–109.

- Fuentes, C., & Fuentes, M. (2017). Making a market for alternatives: Marketing devices and the qualification of a vegan milk substitute. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(7-8), 529–555. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2017.1328456

- Gittins, D. (2008). The historical construction of childhood. In M. J. Kehily (Ed.), An introduction to childhood studies (Second edition). Maidenhead: MC Graw Hill: Open University Press.

- Glover, N. (2009). Imaging community: Sweden in ‘cultural propaganda’ then and now. Scandinavian Journal of History, 34(3), 246–263. doi: 10.1080/03468750903134707

- Government Offices of Sweden. (2017). Retrieved from http://www.government.se/information-material/2017/06/the-swedish-model/2018-02-21.

- Graham, P., Keenan, T., & Dowd, A.-M. (2004). A call to arms at the end of history: A discourse-historical analysis of George W. Bush's declaration of war on terror. Discourse & Society: An International Journal for the Study of Discourse and Communication in Their Social, Political and Cultural Contexts, 15(2-3), 199–221.

- Gunders, L. (2012). Immoral and un-Australian: The discursive exclusion of welfare recipients. Critical Discourse Studies, 9(1), 1–13. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2011.632136

- Halldén, G. (2009). Naturen som symbol för den goda barndomen. Stockholm: Carlsson.

- Halldén, G. (2011). Barndomens skogar: om barn i natur och barns natur. Stockholm: Carlsson.

- Hansen, A. (2002). Discourses of nature in advertising. Communications, 27(4), 499–511. doi: 10.1515/comm.2002.005

- Hellström, A., Nilsson, T., & Stoltz, P. (2012). Nationalism vs. Nationalism: The challenge of the Sweden democrats in the Swedish public debate. Government and Opposition, 47(2), 186–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-7053.2011.01357.x

- Hiroko, T. (2008). Delicious food in a beautiful country: Nationhood and nationalism in discourses on food in contemporary Japan. Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism, 8(1), 5–30.

- Ichijo, A., & Ranta, R. (2016). Food, national identity and nationalism: From everyday to global politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- James, A., Jenks, C, & Prout, A. (1998). Theorizing childhood. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Järlehed, J. (2015). Norden i Europa - Rörelser, resor, föreställningar 1945–2014 (J. a. V. Järlehed, Katharina Ed. Vol. 28). Göteborg: Centrum för Europaforskning vid Göteborgs universitet.

- Jaworski, A., & Thurlow, C. (2010). Introducing Semiotic Landscapes. In Semiotic landscapes. Language, image, space. London: Continuum.

- Jenks, C. (2005). Childhood. London: Routledge.

- Jones, O. (1999). Tomboy Tales: The rural, nature and the gender of childhood. Gender, Place & Culture, 6(2), 117–136.

- Jönsson, H. (2005). Mjölk: en kulturanalys av mejeridiskens nya ekonomi. Eslöv: B. Östlings bokförlag Symposion.

- Kania-Lundholm, M. (2014). Nation in market times: Connecting the national and the commercial. A research overview. Sociology Compass, 8(6), 603–613. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12186

- Kress, G. R., & Van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Krzyzanowski, M., & Wodak, R. (2009). The politics of exclusion: Debating migration in Austria. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

- Linné, T. (2016). Cows on Facebook and Instagram. Television & New Media, 17(8), 719–733.

- The Local Europe AB. (2012, 2012-03-24 kl. 09:47). Liberalisation fastest in Sweden: Report. Retrieved from https://www.thelocal.se/20120324/39864

- Machin, D., & Mayr, A. (2012). How to do critical discourse analysis: A multimodal introduction. London: Sage.

- Mårald, E., & Nordlund, C. (2016). Natur och miljö i nordisk kultur: några idéhistoriska nedslag. Rig, 99(1), 1–13.

- Martiin, C. (2010). Swedish milk, a Swedish duty: Dairy marketing in the 1920s and 1930s. Rural History, 21(2), 213–232.

- Negra, D. (2010). Consuming IRELAND: Lucky charms cereal, Irish Spring soap and 1-800-Shamrock. Cultural Studies, 15(1), 76–97.

- OECD. (2017). OECD Economic Surveys: Sweden 2017.

- Ogan, C., Çiçek, F., & Kaptan, Y. (2007). Reverse glocalization? Marketing a Turkish cola in the shadow of a giant. Journal of Arab & Muslim Media Research, 1(1), 47–62.

- Palmer, C. (1998). From theory to practice. Journal of Material Culture, 3(2), 175–199.

- Pavković, A. (2017). Sacralisation of contested territory in nationalist discourse: A study of Milošević's and Putin’s public speeches. Critical Discourse Studies, 14(5), 497–513. doi: 10.1080/17405904.2017.1360191

- Pfister, M. (2008). Introduction: Performing national identity. In M. Pfister & R. Hertel (Eds.), Performing national identity. Performing National Identity : Anglo-Italian Cultural Transactions.. Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi.

- Prideaux, J. (2009). Consuming icons: Nationalism and advertising in Australia*. Nations and Nationalism, 15(4), 616–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8129.2009.00411.x

- Ryner, M. (1999). Neoliberal globalization and the crisis of Swedish social democracy. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 20(1), 39–79. doi: 10.1177/0143831X99201003

- Salvador, P. (2011). The myth of the natural in advertising. Catalan Journal of Communication and Cultural Studies, 3(1), 79–94. doi: 10.1386/cjcs.3.1.79UL1

- Sandell, K., & Sörlin, S. (1994). Naturen som fostrare: friluftsliv och ideologi i svenskt 1900-tal. In (Vol. 1994 (114), s. [4]-43): Historisk tidskrift (Stockholm) Stockholm: Svenska historiska föreningen, 1881.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. B. K. (2003). Discourses in place: Language in the material world. London: Routledge.

- Soper, K. (1995). What is nature?: Culture, politics and the non-human. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Storey, D. (2001). Territory: The claiming of space. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Swedish Institute, & Ministry for foregin affairs. (2017). Strategi för Sverigebilden 2.0. Retrieved from http://sharingsweden.se/materials/strategi-sverigebilden/2018-02-21.

- Thurlow, C., & Jaworski, A. (2014). ‘Two hundred ninety-four’: Remediation and multimodal performance in tourist placemaking. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 18(4), 459–494. doi:10.1111/josl.12090

- Torell, U. (2005). Vitt, vackert och vetenskapligt. Om värden i svensk tandkrämsannonsering 1890-2000. In R. Qvarsell & U. Torell (Eds.), Reklam och hälsa: levnadsideal, skönhet och hälsa i den svenska reklamens historia. Stockholm: Carlsson bokförlag.

- Van Leeuwen, T. (2005). Introducing social semiotics. London: Routledge.

- Werner, J., & Björk, T. (Eds.). (2014). Blond och blåögd: vithet, svenskhet och visuell kultur=blond and blue-eyed: Whiteness, Swedishness, and visual culture. Göteborg: Göteborgs konstmuseum.

- Wright, R. (1998). Nature imagery and national romanticism in the films of Alf Sjöberg. Scandinavian Studies, 70(4), 461.