ABSTRACT

In this article, we analyse Il Memoriale della Shoah, the memorial of the victims of the Shoah in Milan, which was inaugurated in 2013 and, in 2015, was turned into a night shelter for destitute migrants. To understand the rhetoric and politics of the Memorial, we bring together the notions of affective practices, découpages du temps (lit. slices of time) and multidirectional memory. This analytic approach allows us to examine the nonlinear shape of remembering, the dialectic relationships between the spatialisation of time and the temporalisation of space, the ways in which emotions are brought into being semiotically in context, and the ethical questions that these feelings raise. Through detailed multimodal and affective analysis of the affordances of the built environment and its soundscape, the curation of the Memorial, the contextualisation of three guided tours (two online and one in situ) and politicised commentary on the Memorial’s decision to shelter refugees, our paper illustrates the multi-layered character of the relationship between space and time – one in which the past, the present and the future partly overlap and mobilise political action.

Introduction

In her uncompleted book Responsibility for Justice, Young reminds us that ‘one has the responsibility always now in relation to current events and in relation to their future consequences’ (Young, Citation2011, p. 92). For Young, connecting historical dots is not an abstract exercise of academic navel-gazing but has important socio-political valences. As she puts it,

How individuals and groups in the society decide to tell the story of injustice and its connection to or break with the present says much about how members of the society relate to one another now and how they can fashion a more just future (Young, Citation2011, p. 182)

In what follows, we first begin with an overview of the theoretical underpinnings of the article. We then delve into the different discourses of the space of the Memorial, first by presenting the rationale of the memorial as outlined by its architects, followed by a multimodal and affective analysis of virtual and in situ guided tours; we conclude with an analysis of the media debate following the decision to open the memorial as a night shelter for migrants.

Lieux de memoire, découpages du temps and the affective dimensions of collective remembering

A wide variety of academic disciplines have utilised Pierre Nora’s (Citation1989) concept lieux de memoire (i.e. sites of memory) as a way to capture how memory ‘crystallizes and secretes itself’ (Nora, Citation1989, p. 1), thus taking a variety of forms. However, his examination of the ways ‘memory’ can be made (and fixed) into shapes – whether monuments, museums, fine arts, as well as novels, flags, speeches, etc. – has received considerable critique because it entails a rather static, linear, and ultimately reductive account of the spatiotemporal dimensions of remembering. While acknowledging the importance of lieux de memoire, we suggest that it can be brought into productive dialogue with Foucault’s (Citation1986) somewhat overlooked theorisation of découpages du temps (‘slices of time’), in order to describe more precisely the ‘social and spatial nature of memory’ (Hoelscher & Alderman, Citation2004) as a dynamic and multi-layered phenomenon.

Admittedly, Foucault (Citation1986) employed the expression découpages du temps only cursorily in his essay Des Espaces Autres (Of Other Spaces), where he pointed out that ‘heterotopias are most often linked to slices in time [découpages du temps] – which is to say that they open onto what might be termed, for the sake of symmetry, heterochronies’ (Foucault, Citation1986, p. 26). While heterotopia generated a large body of literature, the whole field of heterotopian studies, its temporal twin, heterochrony, has remained somewhat unexplored. Unfortunately, something is lost when the original French text is translated into English. ‘Slices in time’ does not fully convey the semantic richness of its French counterpart découpage du temps, which alludes to the art of decorating objects with paper cut-outs that overlap with one another (see also Johnson, Citation2013). Thus, découpage du temps suggestively evokes the spatialisation of time – time as paper cut-outs – and emphasises the overlaying pattern arising from the connections between space and time (see also Milani & Levon, Citation2019). When applied to the discursive and material shapes of lieux de memoire, découpages du temps is less about the time/space nexus per se than on the nonlinear shape of collective remembering, an array of overlapping folds formed by the ‘encounters between diverse pasts and a conflictual present … between different agents or catalysts of memory’ (Rothberg, Citation2010, p. 9).

Affect plays a key role in these spatiotemporal encounters. Interestingly, in Nora’s original theorisation, affect is presented as what nourishes the selective nature of memory, and thereby ‘only accommodates those facts that suit it’ (Nora, Citation1989, p. 8). In his view, the affective character of memory is opposed to the rationality that informs history as an ‘intellectual and secular production’, which, in turn, ‘calls for analysis and criticism’ (Nora, Citation1989, p. 8). This is a binary that sits uncomfortably with current theoretical discussions in the humanities and social sciences about ‘the irreducible entanglement of thinking and feeling, knowing that and knowing how, propositional and non-propositional knowledge’ (Zerilli, Citation2015, p. 266). In flagging up the role of affect in the rhetoric and politics of collective remembering, we do not view emotions as pre- or extra-discursive (see e. g. Massumi, Citation2015), but rather are interested in their discursive materialisations and socio-political dimensions.

Analytically, this means focusing on ‘affective practices’ (Wetherell, Citation2012), that is, moments in which emotions are brought into being semiotically in interaction, and thus orient subjects towards other subjects or objects ‘with degrees of proximity and urgency, sympathy and concern, aversion or hostility’ (Martin, Citation2014, p. 120). And, as Martin goes on to explain, ‘these orientations are never fixed or complete but are open to contestation and negotiation, mediated often (though not exclusively) by rhetorical argument’ (Martin, Citation2014, p. 120) or other meaning-making means such as the affordances offered by visual, aural, and material resources of the built environment.

Overall, we believe that the notion of découpages du temps coupled with discourse analytical attention to ‘affective practices’ allows us to give a granular account of the discursive and affective processes through which history and memory overlap, and collective remembering folds in with individual memory with a view to forging responsibility for justice in a lieu de memoire like the Memorial in Milan, to which we will now turn.

The semiotics and politics of remembering at the Memorial

The Memorial was created by architecture firm Morpurgo, de Curtis and Associates in a 7000 m2 warehouse-like area in a street-level section of Milan Central Station. Inaugurated by Benito Mussolini at the height of Italian Fascism in 1931, Milan Central Station was built on two interconnected levels: a street-level railway network for the loading and unloading of freight cars, connected to an elevated track level for passenger traffic through a series of powerful engines and railcar lifts. The space in which the Memorial is located was originally used for mail sorting purposes. However, between 1943 and 1945, it became the site where thousands of Jews and political prisoners were thrown into livestock cars and sent to concentration camps in Italy and Germany. After World War II, this space was returned to its function of postal sorting area, was later repurposed as a technical and logistic zone for railway traffic, and ultimately fell into disuse in the 1990s. When a renovation and redevelopment plan intended to transform this section of Milan Central Station into a shopping centre, a network of Jewish organisations in collaboration with the lay Catholic Community of Sant’ Egidio urged for the preservation of the site and its turning into a Memorial. The work began in 2008 and was completed in 2013.

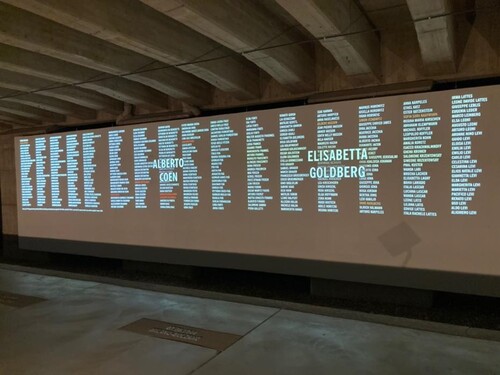

Spatially, the Memorial consists of a sequence of permanent installations (see ): the Wall of Indifference, the Observatory, the Deportation Platform with railcar elevator, the Testimonies Rooms, the Wall of Names and the Place of Reflection. As we will clarify in more detail below, our aim is not to analyse the space in the Memorial in its entirety. Rather we are going to focus on the Wall of Indifference and the Place of Reflection, which are diametrically opposite in terms of their spatial location, being the first and final stop of the Memorial, respectively. As we will see in more detail below, they are also content-wise in a contrapuntal relation to one another: the one highlights the dehumanising effects of indifference and the other ‘reaffirms the responsibility and the ethical dimension of Memory’ (Morpurgo & de Curtis, Citationn.d.). Analysing these two spaces allows us to appreciate the role played by different découpages of time in the Memorial’s enactment of responsibility for justice (Young, Citation2011), and, related to this, the function of specific semiotic choices to create the conditions of a multidirectional politics of solidarity.

In line with scholarship in geography and linguistic landscape (see Ben-Rafael & Shohamy, Citation2016), we believe that spatial analysis cannot be limited to understanding specific material and semiotic choices but should also attend to the breadth of sociocultural practices in which a variety of social actors (architects, guides, journalists, politicians and academics) attribute very different meanings to one and the same space, thus giving rise to moments of negotiations and/or contestations. Therefore, in order to understand the rhetoric and politics of the Memorial, we also analyse excerpts from (a) the architects’ statements about the building project, (b) two online guided tours – one available on the website of the memorial (GT1) and one on YouTube (GT2), (c) the app audio guide of the Memorial (d) photographs and fieldnotes taken by the first author of the paper during a visit in 2021, (e) public pronouncements in online news about the memorial.

Semiotic affordances and the creation of a lieu de memoire

The architects describe their work with the Memorial as an ‘archaeological dig’ intended ‘to give back to the visible structures the original identity that characterised the site’. In their view,

(1)

This project of Memory, the ascertainment of remembrance, is at the same time an archaeology meant as analysis of the beginnings, but also as a discipline of the stratified present, an expressive and telling language, a necessary anamnesis for understanding the present. But how is it possible to ‘re-open’ the past and transform a barbaric location into a place of culture through architecture? (Morpurgo & de Curtis, Citationn.d., English original)

(2)

in a place so quiet, as empty as it should be, the importance of architecture is that it is the only possible language and therefore architecture is entrusted with the task of talking to visitors and managing this deafening silence. Everything you see was thus restored to its natural condition and not wishing to alter in any way the original structure it was decided to create a sort of ideal path, an emotional journey through installations, that does not alter the structure but becomes precisely language. (GT1, our translation)

Crucially, the very shapes of the permanent structures are also meaningful. As the architects explain:

(3)

simple geometrical shapes - squares, rectangles, triangles, circles – form a sort of primary shape alphabet, a pre-linguistic sort of writing, which develops in a series of generative figures inside the span-spaces emphasising the centrality of themes such as transmission, reception, re-elaboration and polarisation of Memory, in a constant movement between the immeasurability of the events that took place in the site and the dimension of personal experience. (Morpurgo & de Curtis, Citationn.d.)

In sum, different affordances of the built environment are employed with a view to bringing into being an affectively laden lieu de memoire. The architects did not aim for a linear account of ‘real’ historical events that happened in the space of Milan Central Station. Such linear approaches, one could add, might run the risk of intellectualising a traumatic past, toning down its emotional proportions. Rather, as excerpt (3) suggests, the architects sought to generate a multi-layered cognitive and affective experience characterised by the overlaying of different spatiotemporal nexus points where the incommensurability of a traumatic past partly overlaps with the present experience of the Memorial on the part of the visitor; the old becomes imbricated with the new; the collective folds in with the personal, raising ethical questions about the duty to remember. It is such découpages du temps that we present in the following sections.

Historical folds of past and present

That space, time, history and the duty to remember are intended to be entwined in complex relationships is stated upfront by the architects when describing their first encounters with the area in which the Memorial would be created:

(4)

While going through the abandoned train manoeuvring spaces of Milano Centrale, we immediately realised that designing the Shoah Memorial meant dealing with the concept of “forgetting” …

The abandonment of the “invisible” postal sorting areas at the end of the 1990s, adjacent to the passenger building manifests the objectification of forgetting; it meant a refusal of responsibility. (Morpurgo & de Curtis, Citationn.d.)

The overlaying of spatiotemporal dimensions at different scalar levels – the here/now of a specific lieu de memoire and more long-standing processes of Italian history – also informs the narration of the guides at the Memorial. For example, the guide Pia Masnini Jarach reminds the visitors of the importance of

(5)

emphasising the humanity of the victims, why they were victims, the process that started with laws approved unanimously by a parliament. Even if it was the Fascist parliament there was no opposition, there was no voice that arose. The king was the first to sign the (racist) laws and it took five years of continuous implementation of the laws in a world where opposition was forbidden, it was punished even with death, where there was no freedom of opinion, in which we had already witnessed imperialist wars, a visceral racism, (all this constituted) a series of political and social strategies and changes that will allow (Fascists) to issue and implement laws and provisions against a part of Italians who could then be hunted like animals and loaded onto wagons with the intent of being completely suppressed. (GT1, our translation)

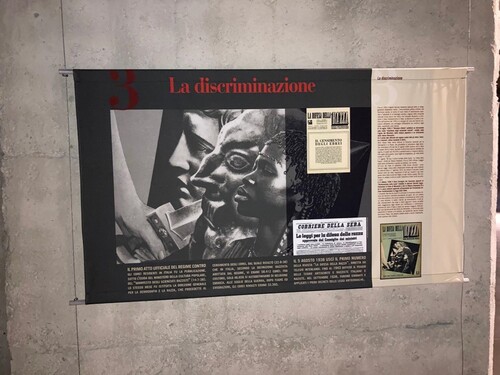

How antisemitism in Fascist Italy was inextricably entwined with racism and colonialism is explained with even more vivid precision by another guide, Ghitta, while pointing at a reproduction of the cover of the first issue of La Difesa della Razza (The Defence of Race), a bi-weekly publication of racist propaganda, which, according to its subtitle, was dedicated to ‘science, documentation, polemic’ ():

(6)

We see three images of people: the first a Greek god, who is he? He is the Aryan, he is the Aryan, handsome, strong, tall, mighty; the second is the Jew, ugly, hooked nose, hmmmm, really ugly hmmm and the third was the African. The Italians had gone to Ethiopia, they knew very well who the Africans were and they represented Africans as animals. What the Fascist and Nazi government did is in practice to give personal connotations to physical aspects … . Propaganda is what allowed the two hundred racist laws to go forward without anyone uttering a word. They were all indifferent. (GT2, our translation)

In our view, it is such a commitment to locating antisemitism and the Shoah within overlapping histories of othering that animates the Memorial as a lieu de memoire, a place where the dialectal relationship between history and memory, past and present, collective and individual calls for an enduring moral duty to remember at the same time as it opens up the possibility for ‘a multidirectional politics of differentiated, long-distance solidarity’ (Rothberg, Citation2019, p. 203) in the present and in the future.

The affective and moral implications of (in)difference

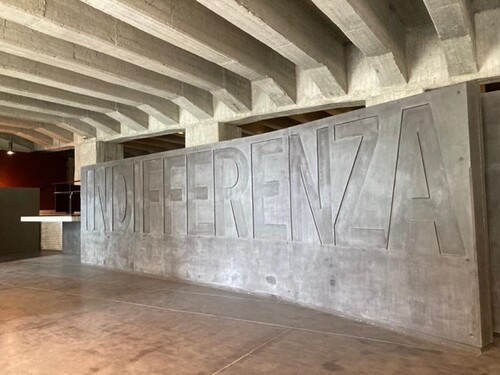

Entering the Memorial, a visitor is met by a long slightly curved wall in which the word Indifference is carved in cubital letters. This word choice was suggested by Liliana Segre, a Shoah survivor as well as one of the founders of the Memorial, who as a teenager had direct experience of this place being sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau together with her father. As the text of the app audio guide explains

(7)

It is the indifference with which Italy, Europe, and the entire free world accepted the laws against the Jews, with hardly a voice raised in protest, allowing a cloud of obscurity to settle over the victims, effectively laying the groundwork for the Holocaust. … Indifference becomes a wall when the victim is seen as being different from us, when we do not take a stand, when we consider ourselves to be more spectators unburdened of any moral responsibility.

For one of us, an Italian citizen who visited the Memorial, the multi-semiotic and multi-sensorial combination of the sight of the Wall of Indifference compounded by the loud thudding sound of the trains above in the empty foyer of the Memorial also engendered an eerie experience of overlapping temporalities with moral and affective implications. The rumbling sound of the passenger traffic above, which happens in the now worked like a synaesthesia bringing into being the images of those horrible carriages so starkly described by Liliana Segre in her testimony:

(8)

The SS and RSI police wasted no time: with feet, fists and truncheons they herded us into the livestock cars. As soon as the car was filled, the doors were bolted shut and the car was lifted in an elevator up to the departure platform. … A chorus of shouts, calls and pleas issued from the sealed cars: no one listened. The train started off again. The car was cold and fetid, the stench of urine, grey faces, stiffened limbs; we had no room to move. The crying subsided into total desperation.

That the Memorial advocates and actively encourages a multidirectional politics becomes particularly palpable in the Place of Reflection, a non-denominational space in the shape of a truncated cone on the rails and reachable through a spiral ramp. As one of the guides explained towards the end of the tour

(9)

We venture inside the Memorial after passing the wall of Indifference and we have finally arrived at the end of this journey, which in reality is a beginning. We find ourselves in the Place of Reflection, a place where we invite all our travellers of the memory to finally get a little more comfortable, to reflect, to gather your emotions to pray, to think, also to cry. Why not? The idea is that of a place that generates energy where everyone is placed on the same level as we are. There is a bar on the ground illuminated by this beam of light that is directed towards Jerusalem. The idea was to find a symbol, a place that it is important in the same way for everyone. Because this is the function of memory: a place of the soul, a place of the spirit, a place of the conscience, that allows us to live our present in a different way, and this is the purpose of the Memorial not only to remember a story but to give us a trace, a tool to work on ourselves in search of difference, therefore the opposite of indifference. (GT1, our translation)

Overall, the texts and the spaces of the Wall of Indifference and the Place of Reflections encapsulate the multi-layered temporality of the Memorial where the atrocities of the past fold into the commemoration of the present and the possibility of a politics of solidarity across differences in the future. While the Wall of Indifference prompts unresolvable tensions that provoke a troubling sense of uneasiness, the Place of Reflection does not bring these tensions to a resolution but opens up nonetheless the possibility of a politics of solidarity across differences (Rothberg, Citation2019, p. 212). Against this commitment to difference, it is quite unsurprising that, at the height of increased arrivals of refugees in Italy, the Memorial acted as it preached, turning a section of its space into a night shelter for migrants. This was a decision, however, that was not unanimously applauded by some members of the public, as we will illustrate in the following section.

The contestation of space and the politics of multidirectional solidarity

In the summer of 2015, the Memorial took the opportunity of its summer closure to offer shelter to 30–35 destitute migrants every night, in collaboration with the lay Catholic Community of Sant’ Egidio, one of the co-founders of the Memorial, which took the responsibility for the operational management of the initiative. As the (then) vice-president of the Memorial, Roberto Jarach, stated:

Participating in a humanitarian emergency situation of this magnitude is certainly a gesture from which we cannot and do not want to escape, even in the essence of the symbolic value of this place, the emblem par excellence of the need to welcome diversity. (Bet Magazine Mosaico, 16 June Citation2015, our translation)

the moral duty to make feel at home those who have been compelled to flee from their homes. Also, because the walls of the Memorial tell a thousand stories of escape, of anguish, of indifference: that same indifference told and denounced by the writing that stands out in the foyer of the Memorial. (Vita, 18 July Citation2017, our translation)

Terrible decision by Milan’s Jewish community and the Holocaust Memorial to support the pro-migrant humanitarian campaign, with implicit parallels between the Holocaust and migrant vessels at sea. The press lives for such stories, with uplifting titles such as “Migrants at Platform 21”. For two years, from Emma Bonino to the Swedish ministers, they have suggested a comparison between Jews in the Holocaust and migrants on the Mediterranean, even up to Pope Francis who compares migration centres with concentration camps. Milan Platform 21 [i.e. the Memorial] could be used to protest on behalf of persecuted Christians, raped Yazidis, or the many minorities oppressed by the same enemies of the Jewish people, the true victims of the current conflict, and certainly not migrants who are cared for and protected. That would be “to honour the memory of the Holocaust”. Jews ought to defend it in this moment of extreme denial and obfuscation, which the Palestinians exploit daily, while avoiding these sentimental ideological traps. Israel does this, caring for whomever, honouring the memory of the Holocaust, but also while defending their borders and culture. (6 August 2017, our translation)

It transpires more clearly in the following sentences of the post that, for Meotti, the insult does not lie entirely in comparisons per se. Nor does he see so much of a problem in the Memorial being used for other purposes than the remembrance of the Shoah. Rather, the crux of the matter is something else, namely the religious identity of the night guests of the Memorial. While the word Muslim is never mentioned explicitly in the post, it can be inferred through the reference to ‘the same enemies of the Jewish people’. These are not only the overt agents in oppressing an unspecified group of ‘other minorities’ but are also the implied offenders lying behind the even more affectively laden processes in the participle phrases ‘persecuted Christians’ and ‘raped Yazidis’. Moreover, through a strategy of authenticity, these two religious groups are raised to the status of ‘true’ victims and are turned into a benchmark of contemporary suffering against whom migrants’ conditions are assessed as considerably more moderate. Paradoxically to Meotti’s aversion to comparisons, his argument rests on the assumption that the suffering of ‘persecuted Christians’ and ‘raped Yazidis’ approximates that of the victims of the Shoah, and hence could be included in the advocacy work of the Memorial. In this way, Meotti sets himself up in the twofold position of judge of who counts as a true victim and of normative arbiter of how the memory of the Shoah ‘ought to be’ defended and honoured. In this self-proclaimed role, he goes as far as portray Israel as the ultimate guardian of Shoah memory. While the direction of the illuminated brass line towards Jerusalem in the Place of Reflection we saw earlier was meant to symbolise a unifying, non-denominational commitment to the respect of difference across identities and faiths, he ties the here/now of the Memorial to the Israel/Palestine conflict in a divisive way, one in which Palestinians are described as ‘abusers’ while Israel is presented as the ultimate stronghold of borders and cultures, and a model to be followed by all Jews. This stance on Israel is not idiosyncratic to Meotti but echoes a more widespread rhetorical pattern about the Israeli/Palestinian conflict, one characterised by

the denial of nuance, the refusal to recognize complicity in creating problems, and the rejection of mutual responsibility for solutions. Since those who act out on these behaviors cannot tolerate difference, they produce unilateral stories based in a profound fear of ever being wrong. (Schulman, Citation2016, p. 208)

Meotti’s post was immediately met with conflicting reactions. While the supporters of his argument also consistently referred to the Israel/Palestine conflict and the role of Israel as a bulwark of civilisation, some of the detractors went as far as accuse him of fascism. Among the more considerate responses are those by Andrea Jarach, the president of the Italian section of Keren Hayesod, the official fundraising organisation for Israel. After thanking Meotti for opening up a debate about the role of remembering, Jarach reiterated how the Memorial is ‘a place that, in the opinion of those who worked on the project under the stimulus of surviving witnesses, must be a living laboratory of human solidarity (as opposed to indifference)’ (Bet Magazine Mosaico, Citation2017, 10 August). Unlike Meotti’s particularising rhetoric that relies on the discursive construction of ethnic/religious boundaries and oppositions, Jarach’s statement echoes the Memorial’s more universalising tactic which emphasises solidarity across identity affiliations in the pursuit of a fight against indifference. It is such a commitment to a multidirectional politics of solidarity across identities that also imbues Liliana Segre’s rhetorical question about the ethics of hospitality: ‘How can a place that has the word ‘Indifference’ printed in big letters at the entrance, say no, say I don't host anyone?’ (Bet Magazine Mosaico, Citation2017, 10 August).

A somewhat less diplomatic and more emotionally laden response was posted on Facebook by Ariel Toaff, the son of the late Chief Rabbi of Rome and professor of medieval history at Bar Ilan University:

For heaven’s sake, whoever wants to support Meotti’s thinking (he of the pamphlet “Jews against Israel”) is free to do so, but cannot prevent being criticised. I have respect for the Catholics and Protestants who are pro-Israel (like Giulio Meotti and Niram Ferretti) but they cannot pretend that all Jews align themselves with their right-wing impulses.

What the hell. In Israel there aren’t only Netanyahu’s right-wingers and Bennett’s settlers. Our friends the Catholics should digest this incontrovertible fact before offering ridiculous lectures to those who don’t think as they do, illegitimately distributing certificates of true Jewishness to those who support their ideas. I don’t occupy myself making lists of true Christians on the basis of their proximity to or distance from my religious and political opinions. Posting photos of soldiers praying or in action with a machine gun surrounded by fluttering Israeli flags, perhaps against the backdrop of armoured divisions, is not enough. It’s just pathetic. It would never enter my mind to publish images of altar boys in procession. It would be in terrible taste. (6 August 2017)

In the final paragraph of the excerpt, Toaff provides – and rejects – another part-for-whole synecdoche for Israel, which he implies is frequently posted by the likes of Meotti: the Israeli soldier. Including images of Israeli soldiers (praying, on manoeuvres, posing with the Israeli flag, etc) in the context of commemorating the Shoah evokes quite specific ideas relating to power and the role of a Jewish Army in ensuring Jewish survival. As Netanyahu wrote in his 1993 book, ‘If there had been an Israel earlier in this century, there surely would have been no Holocaust. […] The Jews are no longer helpless, no longer lacking the capacities to assert their case and to fight for it’ (quoted in Marrus, Citation2016, p. 101). For some people (predominantly though not exclusively from the political right), the principal ‘lesson’ of the Shoah is that Jews were murdered because they couldn’t/didn’t defend themselves; Israelis need to be able to defend themselves, militarily if necessary, since Jews still face a never-ending existential threat; accordingly, the Shoah is understood in the context of Israel’s current conflicts. Such a perspective goes further than providing an historical frame for understanding the present; rather, it represents another découpage in which the Shoah is not over yet, and so Israeli soldiers are necessary to protect the Jews of Israel from annihilation. It is this particular découpage du temps, and the way that it encourages militarism and subjugation, that Toaff critiques.

Concluding remarks

In popular culture – films, TV and literature – on the Shoah, there is a constant pull towards stories with a redemptive message: on resilience, the saved, the indomitable human spirit. We can detect aspects of this in memorials and commemoration too, especially in the desire to draw lessons from the Shoah. Similarly, attempts to channel and redirect empathy for the victims of the Jewish catastrophe into contemporary struggles and campaigns to aid those in currently need also draw on this deep need to clutch onto ‘practically anything that might provide a silver lining to meaningless misery and unmitigated barbarism’ (Marrus, Citation2016, p. 95). Nevertheless, the moral implications of remembering and forgetting are never clear-cut and are always imbricated with the complex politics of implication (Rothberg, Citation2019), a politics that is affectively laden. And it is precisely this moral and emotional complexity that we have examined in this article, focusing on Il Memoriale della Shoah, the memorial of the victims of the Shoah in Milan. Our approach, drawing upon découpages du temps (Foucault, Citation1986) and multidirectional memory (Rothberg, Citation2009, Citation2010), assumed both the nonlinear shape of remembering and the dialectic relationships between the spatialisation of time and the temporalisation of space. Focusing in particular on the affective dimensions (Wetherell, Citation2012) of the Memorial allowed us to examine the ways in which emotions are brought into being semiotically in context, and the ethical questions that these feelings raise.

We argued that the affordances of the built environment were fundamental to the Memorial’s affective practice. These material and aural features are disorientating and disturbing, evoking a range of discomforting, confusing and difficult affective states – responses which are then shepherded into choate sense by the tour materials. We identified the soundscape of the Memorial – a ‘deafening silence’ punctuated by the sound of trains above, arriving and departing – as a nexus point allowing a shuttling between the present and the past functions of the site: trains departing, different destinations, different passengers, different purposes. It is, we argue, the way the Memorial elicits feelings about different people/times/conditions that is the centre of both its political sense making and the questions that it asks of us now.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tommaso M. Milani

Tommaso M. Milani is a critical discourse analyst who is interested in the ways in which power imbalances are (re)produced and/or contested through semiotic means. His main research foci are: language ideologies, language policy and planning, linguistic landscape, as well as language, gender and sexuality. He has published extensively on these topics in international journals and edited volumes. Among his publications are the edited collection Language and Masculinities: Performances, Intersections and Dislocations (Routledge, 2016) and the special issue of the journal Linguistic Landscape on Gender, Sexuality and Linguistic Landscapes (2018). He is co-editor of the journal Language in Society. Address: Department of Swedish, Multilingualism, Language Technology, University of Gothenburg, Renströmsgatan 6, 421 55 Gothenburg, Sweden.

John E. Richardson

John E. Richardson works at the University of Liverpool. His research interests include critical discourse studies, rhetoric and argumentation, British fascism and commemorative discourse. The author of over eighty publications, his most recent books include British Fascism: A Discourse-Historic Analysis (2017) and the Routledge Handbook of Critical Discourse Studies (2018,co-edited with Flowerdew). He is Editor of the international journal Critical Discourse Studies and co-editor of the book series Advances in Critical Discourse Studies (Bloomsbury Academic). Department of Communication and Media, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK, L69 7ZG. Email: [email protected]

References

- Arendt, H. (2003). Collective responsibility. In J. Kohn (Ed.), Responsibility and judgment (pp. 147–158). Shocken.

- Baynham, M. (2003). Narratives in space and time: Beyond ‘backdrop’ accounts of narrative orientations. Narrative Inquiry, 13(2), 347–366. https://doi.org/10.1075/ni.13.2.07bay

- Ben-Rafael, E., & Shohamy, E. (2016). Memory and memorialization. Linguistic Landscape, 2(3).

- Bet Magazine Mosaico. (2015). Il Memoriale della Shoah disponibile ad accogliere i profughi. https://www.mosaico-cem.it/comunita/news/il-memoriale-della-shoah-apre-alcuni-spazi-ai-profughi/

- Bet Magazine Mosaico. (2017). Memoriale: l’accoglienza ai migranti, contro l’indifferenza. https://www.mosaico-cem.it/attualita-e-news/italia/memoriale-laccoglienza-ai-migranti-contro-lindifferenza/

- Capristo, A., & Ialongo, E. (2019). On the 80th anniversary of the racial laws: Articles reflecting the current scholarship on Italian fascist anti-semitism in honour of Michele Sarfatti. Journal of Modern Italian Studies, 24(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354571X.2019.1550695

- Cesarani, D., & Levine, P. A. (Eds.). (2002). ‘Bystanders’ to the Holocaust: A re-evaluation. Frank Cass Publishers.

- Doumanis, N. (1999). The Italian empire and brava gente: Oral history and the Dodecanese Islands. In R. J. B. Bosworth, & P. Dogliani (Eds.), Italian fascism: History, memory, representation (pp. 161–177). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Forti, S. (2015). New Demons: Rethinking power and evil today. Stanford University Press.

- Foucault, M. (1986). Of other spaces: Utopias and heterotopias. Diacritics, 16(1), 22–27. https://doi.org/10.2307/464648

- Hoelscher, S., & Alderman, D. H. (2004). Memory and place: Geographies of a critical relationship. Social & Cultural Geography, 5(3), 347–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/1464936042000252769

- Johnson, P. (2013). The geographies of heterotopia. Geography Compass, 7(11), 790–803. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12079

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. Routledge.

- Labanca, N. (2018). Exceptional Italy? The many ends of the Italian colonial empire. In M. Thomas, & A. S. Thompson (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the ends of empire (pp. 123–143). Oxford University Press.

- Lawson, T. (2010). Debates on the Holocaust. Manchester University Press.

- Marrus, M. R. (2016). Lessons of the Holocaust. Toronto University Press.

- Martin, J. (2014). Politics and rhetoric: A critical introduction. Routledge.

- Massumi, B. (2015). Politics of affect. Polity Press.

- Milani, T. M., & Levon, E. (2019). Israel as homotopia: Language, space and vicious belonging. Language in Society, 48(4), 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404519000356

- Morpurgo, G., & de Curtis, A. (n.d.). Shoah Memorial in Milan - description. http://www.morpurgodecurtisarchitetti.it/mem_description.html

- Nora, P. (1989). Between memory and history: Les lieux de mémoire. Representations, 26, 7–24. https://doi.org/10.2307/2928520

- Pasta, S. (2017). L’accoglienza dei profughi al Memoriale della Shoah di Milano. La funzione educative della memoria. Rivista di storia dell’educazione, 1/2017, 51–72. https://doi.org/10.4454/rse.v4i1.21

- Petropoulos, J., & Roth, J. K. (Eds.). (2005). Gray zones: Ambiguity and compromise in the Holocaust and its aftermath. Berghahn Books.

- Prekerowa, T. (1990). The ‘just’ and the ‘passive’. In A. Polonsky (Ed.), My brother’s keeper: Recent Polish debates on the Holocaust (pp. 72–80). Routledge.

- Rothberg, M. (2009). Multidirectional memory: Remembering the Holocaust in the age of decolonization. Stanford University Press.

- Rothberg, M. (2010). Between memory and memory: From lieux de mémoire to noeuds de mémoire. Yale French Studies, 118/119, 3–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41337077

- Rothberg, M. (2019). The implicated subject: Beyond victims and perpetrators. Stanford University Press.

- Sarfatti, M. (2007). Gli ebrei nell’Italia fascista: Vicende, identità, persecuzione. Einaudi.

- Schulman, S. (2016). Conflict is not abuse. Arsenal Pulp Press.

- Vita. (2017). Il Memoriale della Shoa apre ogni notte per 35 profughi. http://www.vita.it/it/article/2017/07/18/il-memoriale-della-shoa-apre-ogni-notte-per-35-profughi/144071/

- Wetherell, M. (2012). Affect and emotion: A new social science. Sage.

- Wetherell, M. (2015). Trends in the turn to affect: A social psychological critique. Body & Society, 21(2), 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X14539020

- Wodak, R. (2001). The discourse historical approach. In R. Wodak, & M. Meyer (Eds.), Methods of critical discourse analysis (pp. 63–95). Sage.

- Young, I. M. (2011). Responsibility for justice. Oxford University Press.

- Young, J. E. (1994). The texture of memory: Holocaust memorials and meaning. Yale University Press.

- Zerilli, L. M. G. (2015). The turn to affect and the problem of judgment. New Literary History, 46(2), 261–286. https://doi.org/10.1353/nlh.2015.0019