Abstract

This article examines the impact of home-based business on spatial changes and architectural transformation in old apartment buildings, locally called Chung Cu, an under-studied housing typology in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC). This article elucidates how looking into local ideas and practices of domestic spaces with home-based businesses can broaden existing scholarship on home culture. The term ‘home-based business’ is used in this article to describe commercial and business activities run by local residents in their homes. This article analyzed and presented first-hand data in both textual and visual forms and suggests that given the historical and social changes, particularly since the 1960s, the resilience, and persistence of home-based business, as a constituent of local life in HCMC, have significantly contributed to the making and transformation of domestic spaces in the city.

INTRODUCTION

This article examines the impact of home-based business on spatial changes and architectural transformation in old apartment blocks, locally called Chung Cu an under-studied housing typology in Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC), the largest city in Vietnam. The city is commonly known as Saigon. This article elucidates how looking into local ideas and practices of domestic spaces with home-based businesses through an architectural lens can broaden existing scholarship on home culture. The term ‘home-based business’ is used in this article to describe commercial and business activities run by local residents in their homes. This article suggests that given the historical and social changes, particularly since the 1960s, the resilience, and persistence of home-based businesses, as a constituent of local life in HCMC, have significantly contributed to the making and transformation of the ‘modularised’ domestic spaces in apartment buildings in the city. Home-based businesses, their symbiotic relationship, and related architectural consequences essentially shape to the culture of home in Chung Cu. There is almost no study on changes to old apartment blocks in HCMC, while recent studies (Phuong Citation2019; Hong and Kim Citation2021) focused more on old apartment buildings in Hanoi and the impact of local factors, such as building location, spatial pattern and resistance of residents to government’s redevelopment plans, on changes to housing architecture. These studies also show that retail activities are observable only on the ground floor units of old apartment blocks in Hanoi and many of them are not home-based businesses as the shop-owners rent the spaces for their businesses and do not live in these units. Commercial activities in Chung Cu in HCMC, however, are mostly home-based and observable also on upper levels. The current article adds to the earlier studies as it focuses more on home-based businesses and their essential role in driving the changes to the home environment at a household level in modernist-style apartment buildings in HCMC.

This article looks at Nguyen Thien Thuat apartment blocks in central HCMC as a case study. This includes a snapshot of the history of this Chung Cu and some first-hand observations of architectural changes to the exterior and interior of the housing blocks, and how these changes have supported commercial activities, including home-based businesses and the daily life of local communities. This examination will be integrated into a review of the urban history of HCMC as well as existing literature on spatial practices related to the ideas of home, such as the notion of thresholds and the changing ideas of interior and exterior spaces. There is almost no published work on this Chung Cu. A case study with first-hand data from the specific context of this Chung Cu analysed and presented in textual and graphic forms is a contribution to architectural and historical knowledge of public housing in Vietnam.

Present-day experiences of domestic spaces in HCMC are often seen in tall and long ‘shop-houses’ with home-based businesses lining local neighborhoods and streets. They are called ‘shop-houses’ because their ground levels are for retail activities and upper levels are for living. Families run shops with goods displayed on the shop fronts as well as on the streets. This pushes living spaces to the back and on upper levels. This vernacular building typology can be observed in most areas of the city, and spaces accommodating family-based retail activities have been regarded as one of the traditional aspects of the everyday home environment in Vietnam (Phuong Citation2014; Janssen Citation2016). How have such traditional experiences of home-based retail shaped Vietnamese domestic spaces as shown in the local shop-houses? In what way has home-based retail contributed to the making and transforming of domestic spaces as presented in other building typologies, such as modernist-style apartment buildings?

HCMC’s urban structure is characterized by four to five-level apartment blocks or Chung Cu. In response to the housing shortage in the 1960s and 1970s Chung Cu were built around the city with support from the American government (Thai Citation2017). While shophouses are usually built to provide spaces for both living and home-based retail, Chung Cu were originally built for living only. Most Chung Cu have changed significantly as local residents set up home-based businesses at their flats. Architectural and structural changes to Chung Cu were performed to accommodate local everyday needs and retail activities. The general living standard has increased, especially, after Doi Moi (economic reform) policy in 1986 that encourages a market economy with private businesses and global integration. Chung Cu are public properties and all changes to building structures and spaces are supposed to get permits from the government. Most changes to Chung Cu are informal as local residents often made the changes by themselves to accommodate extra spaces for living and retail.

These building changes in Chung Cu have raised some questions about the traditional role of home-based businesses in reshaping the modern home, including flats in apartment blocks in Vietnam. Given the multidimensional and interdisciplinary nature of the idea of home, existing scholarships, including recent work by Petric and Bahun (Citation2020: 1–14), tend to focus more on ‘Western’ concepts of home from cultural and anthropological perspectives. While such works have unwrapped various forms of scholarship and methods for (re)thinking about domestic spaces (public and private, masculine and feminine, inside and outside), in various contexts (home and family life, home and migration, homelessness and homeownership), our examination of domestic spaces in HCMC through an architectural lens adds to current understanding of the home environment where physical spaces and structures of apartment units are altered in response to the local need of home-based businesses and their symbiotic relationships.

SPATIAL PRACTICES AS A PROCESS TO UNDERSTAND HOME/DOMESTIC SPACE

Domestic space is a pertinent subject of study since it was given a central place in the theoretical works by several twentieth-century spatial thinkers, whose ideas offer an important framework for understanding the everyday built environment. While these theoretical discussions are not directly about specific spaces, such as Chung Cu, they present key overarching points that influence the focus and the method of inquiry of the current paper. In phenomenology, Bachelard (Citation1964: 136) explains the meaning of the image of a house and its elements for the intimacy and imaginary of human life. He wrote, ‘every corner in a house, every angle in a room, every inch of secluded space in which we like to hide or withdraw into ourselves, is a symbol of solitude for the imagination; that is to say, it is the germ of a room or a house. In a similar school of thought, Heidegger (Citation1971: 148) discussed the concept of dwelling to raise a significant need to dwell to build and think within the cosmological space of earth, sky, divinities, and mortars. He wrote ‘only if we are capable of dwelling, we can build. We do not dwell because we have built, but we build and have built because we dwell, that is, because we are dwellers’. These theoretical ideas imply that looking in detail at elements and rooms in a residence and the way it is built and used by its dwellers could bring in a greater understanding of the senses of home as domestic spaces.

While these thinkers discussed many faces of phenomenology this article is interested in the material aspects, the physical elements of home, or as Bachelard (Citation1964: 136) explained ‘the direct surroundings of a human being: houses, huts, rooms, attics, cellars, corners, drawers, chests, locks, and wardrobes. This article is inspired by the phenomenological notion of threshold, the opposition of inside and outside, and, particularly, their physical manifestation in domestic spaces.

Heidegger (Citation1971: 201) presents an example of how thresholds are reflected in the physical world as follows:

the threshold […] bears the doorway as a whole. It sustains the middle in which the two, the outside and the inside, penetrate each other. The threshold bears the in-between. What goes out and goes in, in the in-between, is joined in the between’s dependability. The dependability of the middle must never yield either way

Bachelard does not directly discuss ‘threshold’, but his use of the term, ‘the borderline surface between the inside and the outside of the door’, is strongly related to this idea. In relation to the notion of inside and outside, Bachelard (Citation1964: 217–218) elaborates on the image of the door, a home element that physically marks a threshold, as:

Outside and inside are both intimate spaces; they are always ready to be reversed, to exchange their hostility. If there exists a borderline surface between such an inside and outside, this surface is painful on both sides.

Author Pauline Garvey (Citation2005) explored the idea of domestic borders through an ethnographic examination of domestic windows in the Norwegian town of Skien. The author argues that the window, a home’s physical element, marks the threshold of the Norwegian home as a dynamic space that suggests an interface for public and private interaction. Windows of Norwegian homes and associated decoration and the way they are used are particularly local to the town of Skien not only because they present the difference between homes of Norwegian owners and those owned by other ethnicities but also because they act as physical representations of this public-private dynamic. While apartment blocks in Skien and HCMC are contextually different, Garver’s findings from Skien’s windows reinforce the need to examine building elements, particularly those at the so-called borderlines, such as doors, corridors, balconies, walls, and roofs, not only as seemingly fixed and splitting or passing divides between spaces but also as penetrable and interchangeable thresholds where the boundaries between public vs private, and indoor vs outdoor, are blurred both physically and visually.

From a sociological point of view, Pierre Bourdieu’s intensive study of a Berber house highlights the importance of the spatial organizations in which each space with its rituals is seen as a division between two oppositions: private/public, inside/outside, and dark/light. For Bourdieu, these separations also reflect the oppositions of male and female spaces. He wrote, ‘the house is organized according to a set of homologous oppositions: fire: water: : cooked: raw: : high: low: : light: shadow: : day: night: : male: female: : nif: họrma: : fertilizing: able to be fertilized: : culture: nature. But in fact the same oppositions exist between the house as a whole and the rest of the universe. Considered in its relationship with the external world, which is a specifically masculine world of public life and agricultural work, the house, which is the universe of women and the world of intimacy and privacy, is haram, that is to say, at once sacred and illicit for every man who does not form part of it […]’ (Bourdieu Citation1990, Appendix X). Bourdieu’s ideas imply that to get a better understanding of a sense of home as domestic space it is important to look at the spatial organization of a residence and everyday practices that reflect the spatial division/opposition of, for example, domestic/public realms and interior/exterior spaces.

In the field of cultural history, Irene Cieraad (Citation1999: 1–13), suggested that the traditional perception of home space is often tied to the popular concept of confined physical spaces and their clear distinction between interior and exterior territories or between public and private spaces. This perception seems to be extendable when looking at domestic spaces in Vietnam where the uses of spaces hint at unclear boundaries between private and public realms. This is observable in the traditional home setting with shop-houses lining up local streets in major cities such as Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh as local shop owners usually use the street sidewalks outside of their shop-houses as extended shops, workshops, and dining rooms.

The phenomenological approach to spaces as outlined above suggests several points of focus to examine the everyday practices of domestic space in HCMC. To enrich our understanding of domestic spaces and home culture these points are projected in detail in this article through an architectural analysis of changes to apartment units and the underpinning social and historical influences in HCMC. The present article examines spatial practices with home-based businesses in HCMC. This includes but is not limited to the examination of (1) home interior and exterior elements, details, construction, and the way homeowners use and change spaces; and (2) spatial organization and changes and associated everyday life activities, including those at threshold spaces in relation to the notion of inside and outside.

DOMESTIC SPACES AND HOME-BASED BUSINESSES

The term home presents a broad and diverse meaning ranging from a physical place or a location for residences, such as a house, a hometown, a home village, a home city, and a home country. Home can denote feelings, emotions, and memories of persons to the place and location. The scholarship of the home is also multi-disciplinary as it is an area of study for various disciplines, and each often contributes differently to the definition and understanding of home. In this article, a home is a residential place. Therefore, the term home-based business means a business that is run in a residential place by homeowners. This idea of home-based business can be located within the broader idea of homeworking as loosely defined in existing scholarship as paid tasks or services that are performed primarily within domestic environments (Sullivan Citation2000, Citation2003; Heyes and Gray Citation2001, 2003). Homeworking can be seen in many occupations and domestic contexts. Homeworking is seen in professional occupations when office workers choose to work from home or designers and accountants run their consultations at home offices. Homeworking can be seen when daily service jobs are performed at homes by tailors and electrical repairers or barbers. Probably the closest idea of homeworking to home-based businesses is defined by Felstead and Jewson (Citation2000: 15) as “economic activity by members of households who produce within their place of residence commodities for exchange in the market.” Home-based businesses, particularly family-run retail and production have been popularly practiced as part of local culture in Vietnam for centuries. This probably is most obviously in the practices of home-based, village-based specialized retail and productions in both rural dwellings and urban shop-houses (Phuong Citation2010). While each Vietnamese village is often known for specialization, such as a craft or a daily product that is homemade, shophouses in Vietnamese streets are architectural presentations of urban home-based businesses for hundreds of years. Old shop-houses of one or two levels were built to provide accommodation (house) and spaces for the family business (shop) in major Vietnamese cities since the fifteenth Century (Phuong Citation2014). Modern shophouses, usually more than 3 levels, are still the most popular housing typology in urban areas in Vietnam.

The phenomenon of home-based business has attached scholarships from different disciplines. For the case of a home interior that is used to accommodate office work or business, the author Akiko Busch (Citation1999: 81–93) suggested that professional works occur within the domestic spaces blended in with the occupant’s daily living, confined within the interiority and distinctively divided from the public sphere. While the functions and uses of spaces and objects within the home can be mixed, the notions of interior and exterior are not. At an urban scale, Ha, Rogers, and Stevens (Citation2019), looked at the economic implication of home-based businesses, as one form of informal urbanism, for planning practices in Hanoi via an analysis of the proximity of these home-based business activities to the main streets. Other studies (Fitzgerald and Winter Citation2001; Lynn and Earles Citation2006; Chen and Sinha Citation2016) have raised the essential roles of home-based businesses in the well-being of the urban economy and family life. The current research, however, is interested in the spatial and design implications of such home-located economic activities on domestic environments. More particularly, this article wishes to extend the current scholarship by looking at how home-based businesses have influenced the way homeowners in Ho Chi Minh City create and change their places of residence. It examines different ways architectural spaces, such as those in apartment blocks originally built merely for residence, have been resilient to changes to accommodate home-based economic activities and vice-versa.

METHOD OF INQUIRY

The case study method is adopted to empirically investigate the impact of everyday life activities including home-based businesses on architecture and spaces. Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat is selected for this research as it is one of the earliest and largest American-supported housing developments that are still fully occupied to date. This Chung Cu has experienced significant changes under different historical changes since its development in the 1960s. Detailed studies of this Chung Cu are representative and valuable because they provide insight into the architectural and spatial changes that illustrate how some aspects of local spatial practice, such as home-based businesses, are introduced in an imported building typology that was not originally designed for them.

In general case study method is highly applicable in architectural-related studies because of its advantages as discussed by Wang and Groat (Citation2013): (1) a focus on specific cases with their real-life contexts; (2) findings from case studies are explanatory and descriptive; (3) the importance of theory development in the research design phase; and (4) allow the research to generate theory. These advantages apply to Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat as it has a rich architectural and spatial narrative, which is under-studied. Looking at this Chung Cu, its spatial changes with home-based businesses and specific social context extend our understanding of domestic spaces and home culture in HCMC, where one of the fastest urban renewals is taking place.

Fieldwork observations were conducted at Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat in 2017 and 2018. Empirical research data was collected by taking photographs, doing sketches, measuring drawings, and taking notes. There were two sets of observations on the impact of home-based business and daily activities on the physical form and spaces of the Chung Cu. This includes looking at the public space around the apartment blocks and interior spaces of several flats. The first set of observations targeted the public spaces, particularly the threshold spaces in the Chung Cu: the shared corridors, shop fronts, the streets, staircase landings, and building façade details such as balconies, staircase railing, over-hanged structures, shop signs, and advertisement boards. The observations were conducted at different times of the day which enabled the authors to thoroughly examine the physical characteristics as well as the use of shared spaces at the site.

The second set of observations involved interviewing local residents who run home-based businesses at the site. Detailed observation and open-ended interviews were conducted with Mr. Nguyen’s and Mr. Bao’s families at flats 240 and 220 respectively. They were selected for this research as both families have lived locally for generations and Mr. Nguyen and Mr.Bao have lived in the flats for several decades. They have directly experienced changes including building changes to the Chung Cu. Particularly they were directly involved in the process of making changes to their flats. Detailed observations were made of the interiors and exteriors of the flats (interior layout, the use, and division of spaces, fittings, furniture and renovation work, and uses of public/shared spaces).

Research data in the form of archival materials, such as planning maps, architectural drawings, and historical photos of Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat, were collected at the Department of Urban Planning of District 3, local museums, and libraries. This secondary data together with interviews also provide some contextual background on Chung Cu.

HISTORY OF HOME-BASED BUSINESS AND RESIDENTIAL SPACES IN HCMC

As previously mentioned, running a family business at home is one of the most popular and traditional aspects of everyday life in HCMC. Before the French colonization in 1858, local residents ran shops selling general household items, such as hand-crafted buckets and oil lamps at their thatched houses (Lien Citation2013). These home-based retails were booming from the late 18th to early 19th centuries with the mushrooming of shop-houses, particularly in the Chinatown area in District 5 (Loi Citation2015; Hiep Citation2016a). Even though shop-houses present different physical appearances they share a similar pattern of usage with shops on the ground levels and spaces for living on the upper levels. Shop owners often used part of the sidewalk in front of their shops for retail. The sidewalks were also used by street vendors and local residents for other activities, such as children’s playgrounds, family sitting spaces, and watching people passing by. The use of a street sidewalk as an extension of shops was generally not accepted as it potentially brought disorder to local streets according to the French colonial authority. It was a challenge to control such activities. Strict regulations with fines were applied to keep the sidewalk clear. Local shop owners always found a way to get away with the fines as they could quickly move items from the sidewalk to their ground floor shops when local police came. The flexible use of spaces at the shopfronts on HCMC’s old streets is a historical example reflecting Heidegger’s general ideas of a threshold space where indoor and outdoor and private and public experiences seem to be reversible despite the strict control from the French colonial administration to keep public spaces clear of private and domestic activities.

At the departure of the French in 1954, Vietnam was divided into two parts. The South with Saigon as its capital was influenced by capitalism with American support (1954–1975). The North with Hanoi as its capital was influenced by socialist ideology with support from China and Russia. Saigon faced challenges in providing homes for the increasing population in the 1960s. The government introduced large-scale housing development with apartment blocks or Chung Cu as a new housing typology, which was rapidly built between the 1960s and 1970s with American support in the city (Thai Citation2017). It is estimated by the Department of Construction (Citation2016) that there were about 450 Chung Cu with approximately 26,362 flats to accommodate about 80,000 residents. The apartment blocks look similar and usually have four to six levels with basic amenities, such as supermarkets, a grocery store, a medical clinic, schools, parks, and a cinema (Thai Citation2017). Chung Cu residents came from various backgrounds including migrants from other provinces and local residents.

The original planning and building layout of the Chung Cu set clear boundaries and zoning between residential, commercial, and other amenities; between the apartment blocks and local streets; and between interior and exterior spaces of apartment units.

In 1975, the departure of Americans led to the reunification of Vietnam and South Vietnam, including Saigon under socialist ideology with the subsidized system (Bao et al. Citation2016: 17). Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi became the capital of unified Vietnam. This was followed by waves of people leaving their homes for America as refugees including those who had lived in the Chung Cu. Abandoned flats were taken over by the new socialist government of unified Vietnam. They were then allocated to those who were employed by the new government under a subsidized housing scheme, which had been practiced in North Vietnam since the 1960s. Like most other parts of HCMC, Chung Cu provided homes for both existing residents who were under housing schemes with American support and new residents who came under the socialist housing system. Home-based businesses also could be found in Chung Cu. During the subsidized period with the rigid socialist ideology (1975–1986), private businesses including family-based businesses were strictly controlled. Private sectors, which were rejected and received no official support, were replaced by the collective model of manufacturing and services locally known as hop tac xa, managed by the socialist government (MacLean Citation2008). However, many residents, including those living in Chung Cu still informally operated home-based businesses in their apartment units.

In 1986, the government introduced the Doi Moi policies with the opening up of Vietnam to foreign trade and investment. This marked the return of capitalism, characterized by an open-market economy, yet under socialist ideology, followed by the official return of private businesses and property ownership. Home-based businesses were brought back to local streets and buildings. Together with the mushrooming of new buildings, renovation and extension to existing buildings including Chung Cu are very popular to accommodate the increasing needs for home-based businesses (). Even though the physical changes to Chung Cu both in interior and exterior spaces are deemed to be illegal, uncivilized, and unsafe, they are popular practices. Because of the lack of maintenance and the increase in population and local business activities, most Chung Cu suffered from downgrading and a shortage of spaces for living and family businesses.

CHUNG CU NGUYEN THIEN THUAT AND HOME-BASED BUSINESSES

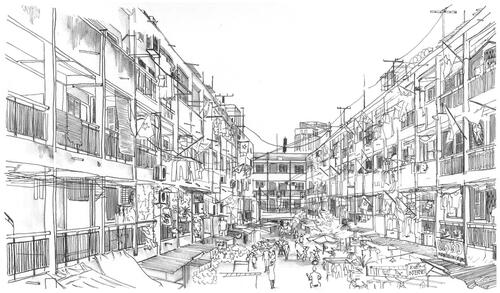

The site area of Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat is approximately 4 hectares located in District 3 bordering District 1 (Central Business District) to the east and District 5 (Chinatown of HCMC) to the south. The site comprises 11 four-level apartment blocks with precast concrete structures (). Blocks A and B, each building footprint of 3600 square metres, are the biggest. Blocks F1 and F2, are the smallest with a building footprint of 450 square metres each. The apartment blocks have a similar layout; each has a row of flats that share a 1.2-metre wide corridor running the length of the block. There are three staircases in each block, one at each end and one in the middle, with access to upper levels. Local roads between the blocks, each approximately 6-metre wide, were used for pedestrian pathways.

Figure 2. The area of Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat are highlighted in red (plan retrieved from the Planning Department of People’s Committee of Ward 1, District 3 - 2018. Reproduced by the authors, 2018).

Historically, the Nguyen Thien Thuat site was an informal settlement with thatched houses characterized by a maze-like network of laneways (Cu, Citation2016). In the 1960s, most houses in the area were burnt down or badly damaged by the Vietnam War. The construction of Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat was then initiated as part of the American-supported redevelopment plan for Saigon. The urban grid layout, which was developed by the French colonial government in the Central Business District, was extended to Nguyen Thien Thuat area. It is popularly known as khu ban co literally means "chessboard area" for its layout like a chessboard. Blocks of apartments were built on the site of the informal settlements following this grid layout.

Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat was first opened in 1968 to relocate families who lost their homes at the site and those who migrated to Saigon from nearby provinces. Eleven residential blocks consisting of 1396 flats were initially planned to provide homes for 4000 residents. Each block had a government-owned grocery store located at the corner of the building. Flats on the ground level were 42 square metres each with a 3.5-metre ceiling height. Upper-level flats were 35 square metres each with a 2.5-metre ceiling height. The ceiling height of ground-level flats allowed their owners to add mezzanines to get extra space. Like many other Chung Cu, owners of ground-level flats made some interior changes to open shops for family businesses because their locations are more accessible as compared to upper-level flats. Interior renovations to accommodate these businesses were done with technical help from the local government before 1975. However, the construction and material costs were paid by the flat owners (Thai Citation2017).

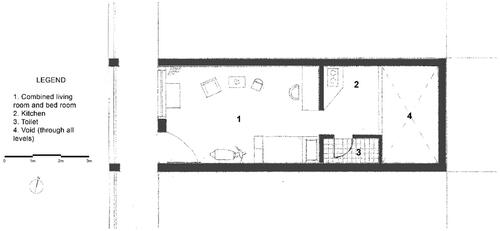

Flats have a similar overall interior layout. Each flat has a living space, and a bedroom, with a cooking area facing a toilet at the back. There was a void for ventilation running through all levels near the cooking areas at the back of the flats. According to present-day living standards, the flats were small and would not be sufficient for the typical needs of families of three or four members. They however were appreciated by people who had suffered from the impact of the war.

With the socialist subsidiary system after the end of the Vietnam War, the private sector was not allowed. Several state-owned general stores and stalls were set up in the Chung Cu and the common spaces between the blocks to provide everyday goods to local residents in the form of coupon exchanges. While private trading was restricted local residents still informally ran home-based businesses in their flats for extra income. Many ground-level flats in this Chung Cu opened restaurants, beverage shops, and grocery shopsFootnote1 ().

Significant changes happened to Chung Cu after Doi Moi in 1986. These changes were mostly due to the mushrooming of home-based businesses and the increasing number of new residents who moved to Chung Cu in the 1980s. According to the survey done by the Centre of Urban Research and Forecast (PADDI) in Citation2012, the number of residents in Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat had almost doubled compared to its initial population. It is estimated that there are now 7420 people living in Chung Cu. The report further showed that there are about 450 home-based businesses officially registered with the local government. Nevertheless, our field observation suggested that the actual number could be many more.

Most staircase landings and corridors on all levels in the Chung Cu are commonly used as commercial spaces selling daily groceries and extra spaces for domestic activities. Small items, such as snacks, soaps, and cleaning detergents are hung on the balcony, or displayed on built-in shelves on the walls. Some spaces are used as coffee shops. Shop owners bring their furniture, such as small plastic stools, tables, and sometimes, even sofas to serve their clients as well as themselves as family lounges. They arrange the landing spaces according to their business need, which seems to add more livelihoods to the Chung Cu. For example, several residents, mostly female set up their shops and lounges in the landings in Block A (). The informal occupation of threshold spaces in Chung Cu, such as balconies and shared spaces in front of flats, for domestic, private, and commercial uses reflect Bachelard’s notion of borderline spaces or thresholds in Heidegger’s term, where indoor and outdoor experiences are not a purely geographical division but rather interchangeable. And local need for home-based businesses appears to be a key driver that makes this spatial character more noticeable in the case of Chung Cu.

The ground-level noodle shop next to flat number A102 is often full of customers. They sat on stools and tables on the footpath in front of the flat while urging the shop owner and her assistants to bring their favorite sauces from the stall located in the shared courtyard. On the first floor, there is a rice vermicelli stall that usually opens for the morning shift. The 50-year-old lady who owns the stall stores her cooking tools in a nearby built-in wooden cabinet while chatting with neighbors. At the coffee shop on the second floor, there is often a group of senior male residents leisurely sipping Vietnamese-style coffees. They often dress very casually, some in pajamas or even topless with shorts on a hot day. They gather at this coffee shop for a drink and chat or just to look over the steel balustrade for a passer-by to converse. These everyday activities in Block A can be seen in most landings, corridors, and ground floors in other apartment blocks where shops are usually run by women while men hang around nearby coffee or tea shops. Such activities are diverse and often around home-based businesses located inside the flats and around threshold spaces at the apartment blocks, such as staircase landings, corridors, and footpaths in front of individual flats. This domestication of the threshold spaces seems to add character and livelihood to Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat.

In Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat residents physically make use of public areas in front of their flats as an extension of indoor spaces for daily domestic needs and businesses. The 6-metre wide streets between the blocks are now shrunk considerably due to the extension done by ground-level flat owners (). Since there are no private garages and drying spaces within the flats, locals tend to park their scooters on the street in front of their flats. Clothes racks are not only used for drying family garments but also for ‘marking’, informally, their home territories on the shared spaces, such as corridors and footpaths. These informally self-acclaimed territories allow flat owners to have extra spaces to set up their shops, furniture, shading, and parking spaces. Spaces in front of some flats are occupied by vendors who sell vegetables, fruits, or knick-knack items. These vendors sometimes park their bikes on the street and walk up the upper levels of the Chung Cu for delivery and to attract more local buyers.

Figure 5. (Left) A coffee shop next to a flat run private parking service for block A’s residents; (Right) Hawker and temporal vendors at block J (photographed by the authors, 2018).

The outdoor environment in Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat is socially and economically nourished by everyday life activities. The once monotonous building façade is now architecturally adapted to local lifestyles and everyday needs with the self-made structure made by local residents. Flat owners also add structures to the flat balconies and shared corridors to make extra spaces for everyday needs. Extended balconies with different looks are created by adding temporary structures, such as steel clotheslines; overhang shelving for storage, small gardens, spaces for pets, awning systems, and steel frames to exhibit business signs. The front walls of some flats are demolished and replaced with completely new structures, such as shop-style sliding doors to better suit home-based businesses ().

Figure 6. (Left) Front wall of this flat has been replaced with steel sliding panels and granite cladding, (Right) Recording of Chung Cu’s façade at present-day (Photographed and sketched by the authors, 2016).

In the interview with Mr. Nguyen, he suggested these changes have been occurring since his family moved in 1988.Footnote2 However, he said that these changes are criticized by the local officials as they were done without formal permits, and for them, the changes negatively affected the structure and look of Chung Cu. However, as the procedures to apply for a permit for building changes were complicated flat owners like Mr. Nguyen would do it without notifying the local authorities. These hurdles were also revealed by Mr. Nguyen’s neighbors, such as Mr. Bao who said that local flat owners are in critical need of extra spaces to run home-based businesses, which are usually the only sources of income. Most flat owners would rather quickly make changes to the flats to accommodate these needs without official approval because the permit application process is unclear to them.Footnote3 After decades of use, most apartment blocks ran down due to over-uses and the lack of maintenance support. It seems that flat owners had no other better choice but to make these informal changes as the most immediate and practical response to their everyday needs.

As observed by the authors in 2018, several flats on the fourth level of Block A added structures used as mezzanines on the roof of the block. They used bricks to build the walls and barricaded the building elevation and roofs with steel meshes and aluminum sheets to prevent thieves. Most of them are used for leisure spaces, such as private gardens and sitting spaces. Some of them are for rent. Mr. Bao believes that these structures were built around 2008 (). The permeability of thresholds in Chung Cu is facilitated through the modification of architectural elements, such as the front walls of the flats and the roofs on the top-level flats, which were originally built to clearly define indoor and outdoor spaces. These physical changes for indoor-outdoor permeability denote an architectural manifestation of the phenomenological notion of penetrable thresholds enabling public and private spatial relationships.

Figure 7. (Left) New structures at Block A created a ‘fifth’ level, (Right) Additional ‘room’ at Block C (Photographed by the authors, 2018).

In early 2010, the government cleaned up the balconies in Blocks A and B in Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat. The extended structures attached to balconies were removed and replaced with new steel railings. This was an attempt to deter further physical changes to the apartment blocks. The balconies were then registered as public spaces and any changes are subject to approval from the local government. Mr. Nguyen,Footnote4 who has lived in the Chung Cu since 1988, revealed that the newly cleaned-up balconies only remained intact for two months as the local residents modified them again by adding shop signs and other overhanging structures for domestic and business uses.

Mr. Nguyen and Mr. Bao, who live respectively at Flats 240 and 220 in Block B also made changes to their flats to accommodate home-based business between the 1990s and 2000s. Mr. Nguyen’s mother has been running private tutorials for local students at the primary level since the late 1990s. At the same time, Mr. Bao’s father owned a small coffee manufacturing workshop in his flat. The following section will examine these two flats in detail to have a better understanding of how domestic spaces in the apartment blocks have been changed and adapted to accommodate specific home-based businesses.

Changes to Mr. Nguyen’s Flat 240

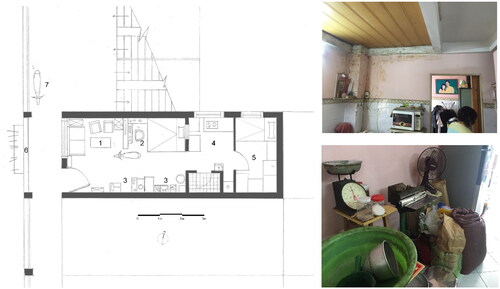

The flat was originally a studio unit located on level 2 of Block B. It is currently occupied by three people: Mr. Nguyen, who works as a financial advisor for a local company; his father who is a lecturer in Japanese; and his mother who is a teacher at a local primary school. Mr. Nguyen’s mother also runs private classes at home. They purchased the flat and have lived in it since 1988. The previous owner did not make any substantial changes to the flat before selling it to Mr. Nguyen’s family. The flat is 3.5-metre wide, 10-metre long, and 2.4 metre- high. It has a shared space for living, dining, and sleeping in the front, a kitchen in the middle, and opposite the bathroom. At the back, there was a void for ventilation that circulates all levels (). The original sizes of the flats were not sufficient for the growing needs of Mr. Nguyen’s family. Mr. Nguyen’s father decided to make some changes to the interior space of their flat.

Figure 8. Original floor plan of Mr. Nguyen’s flat before the changes: 1. Living/bedroom 2. Kitchen 3. Toilet/shower 4. Void (Produced by author s, 2018).

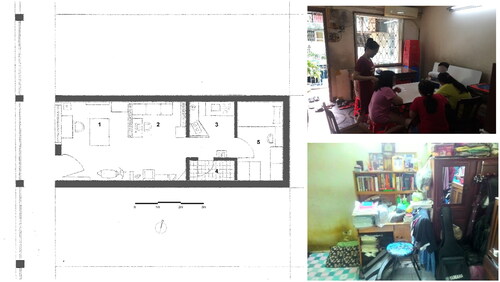

When the family first moved in, Mr. Nguyen’s father anticipated that the flat needed a dedicated bedroom. He asked a local builder to build a light concrete slab over the void at the back of the flat. Then they built a 100 mm thick brick wall to contain the kitchen. As most other flats also required extra living space their owners wanted to fill up the void spaces in their flats. Therefore, mutual agreements were made between Mr. Nguyen’s family and their neighbors, by which they could build up the void spaces that run through all levels. The open space for living and dining was divided into smaller spaces by a wooden bookshelf. The flat now has a living room near the entrance, a combined working and sleeping space for Mr. Nguyen in the middle, next to the kitchen area. The bedroom for his parents is in the back. As Mr. Nguyen’s mother is a teacher there are piles of books at almost every corner and built-in shelves in the flats. All changes were managed by Mr. Nguyen’s father. He suggested that the family did not hire any architectural or engineering consultants because these services were out of the family’s budget. His father asked a local builder to do the job. He also discussed with the owners of neighboring flats directly above and below his flat to make sure that they agreed on a plan. Both Mr. Nguyen’s father and his neighbors made these building changes without notifying the local officials due to the complicated process of getting approvals from the local government ().

Figure 9. Mr. Nguyen’s flat in 2018. (Left) floor-plan of Mr. Nguyen’s flat after the changes: 1. Living/teaching room 2. Mr. Nguyen’s private quarter 3. Kitchen 4. Toilet, laundry 5. The void area used as the parent’s bedroom; (Top right) A tutorial for local primary students; (Bottom right) Parent’s bedroom (Produced and photographed by the authors, 2018).

For almost 20 years, Mr. Nguyen’s mother has been running extra tutorials for local primary students outside of school time in the living room. The student’s parents knew her from school and sent their kids to her flat for extra tutorials. Throughout the years, Mr. Nguyen’s mother has attracted more and more students, who not only live within the Chung Cu, but also come from other areas. Some local officials, who managed the Chung Cu also send their kids to her tutorials, which are usually between 5 pm and 7 pm with an average of 12 students per session. Students sit around a large foldable table in the living room. However, the number of students can exceed the average with a peak of 20, especially during the examination period. These extra students will make use of the shared corridor as their temporal ‘classroom’. The entrance door of the flat is opened during these tutorials. While her class is on, other family members would use other spaces inside the flat as normal such as having dinner or a nap. They, however, would need to do it silently so the students can concentrate on the lessons. Given that the common corridor was used as a private classroom for almost 20 years, Mr. Nguyen’s family received almost no complaints from their neighbors who are rather accommodating. This may be partly because his neighbors who run different home-based businesses, such as stationery shops, bicycle parking services, and coffee and snack shops often have more customers who are the students and parents coming to Mr. Nguyen’s flat for classes.

The use of domestic spaces in Flat 240 highlights the role of home-based businesses in loosening thresholds between public and private or outside and inside at both functional and physical levels. Functionally, the private family lounge is turned into a classroom for local children. Physically, threshold spaces, such as doorways and shared corridors, are occupied for private purposes, which, in this case, include running classes as a home-based business.

Changes to Bao’s Flat 220

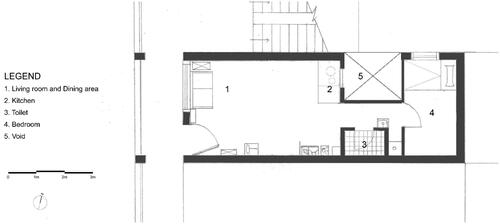

One of our interviewees, Mr. Bao lives in Flat 220. Even though this flat and Mr. Nguyen’s flat (number 240) have the same overall measurement their original interior layouts were different as Mr. Bao’s is a one-bedroom flat () while Mr. Nguyen’s is a studio flat. Mr. Bao’s family consists of four members: Mr. Bao, who works as a marketer for a local creative agency; Mr. Bao’s brother who used to live in the flat but moved to Japan in the early 2000s; and Mr. Bao’s parents who ran the coffee workshop at their home. The family is of Chinese background and used to live in the Chinatown area in District 5. Mr. Bao’s parents started their coffee business when they stayed in Chinatown. They decided to move to Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat due to its proximity to the city center, which is better for their business. They first purchased Flat 230 of Block B in 1990. In 2000 they bought another one in the same building, Flat 220, where they currently reside and run their coffee business. Flat 230 is now home to Mr. Bao’s aunt who is taking care of his 75-year-old grandmother. Mr. Bao’s father also wanted to buy the next-door flat (number 218) as his vision for future living with extended families. He knew that the owner of Flat 218 was moving out so he wanted to purchase it for his son, Mr. Bao. The plan was that they would combine the two flats and when Mr. Bao gets married they live close to each other. However, due to a limited budget, they could not afford to purchase Flat 218.

Figure 10. Original floor plan of Mr. Bao’s flat before the changes: 1. Living/Dining room 2. Kitchen 3. Toilet/shower 4. Bedroom 5. Void (Produced by the authors, 2018).

In Mr. Bao’s flat, the coffee workshop is in the living room with several tools: two coffee grinders, a thermal sealer, a weight scale, and buckets to store ground coffee. Small orders for ground coffee are done in this home-based workshop. Large orders are sent to a larger coffee workshop for production and product in bulk is brought to the flat once a week. These orders then are delivered by Mr. Bao’s parents to their clients. On busy days, workshop activities are extended to the common corridor in front of the entrance door, the family sitting space, and Mr. Bao’s sleeping space, which is only separated by a TV cabinet. The kitchen and toilet are in the middle of the flat followed by the bedroom for Mr. Bao’s parents at the back. There is no drying space in the flat, so the family used the balcony in front of the entrance door to dry their clothes. Mr. Bao’s father keyed a steel bar running across the length of the balcony and used it as a clothing rack. The landing area next to the flat is also privately used for motorbike parking.

The coffee business has been successful for almost 30 years in this Chung Cu. Mr. Bao’s father said that many of his long-term business partners are owners of beverage shops and coffee vendors around Chung Cu, including the coffee vendor at the landing area on the second level of Block A. His partnership also extended to other shops located in Districts 1, 3, and 5. He further explained that his coffee workshop is small so his coffee production is limited in terms of quantity. However, this allows him to focus more on improving the quality of his service and the beans. Mr. Bao suggested that this business has had a good reputation because of the good quality ground coffee making and services, which have been spread out mainly via word-of-mouth references between his clients rather than formal marketing strategies.

He also spiritually believes that the renovated kitchen has brought in good luck securing the success of his home-based business. The previous owners of flat 220 used the landing area to set up their private kitchen as the original kitchen in the flat was very small. Mr. Bao’s father believes that a home without a designated kitchen space would bring bad luck to its owner who runs a home-based business. He said that this belief is part of phong thuy – a Vietnamese version of Chinese feng-shui, which are a system of techniques and associated belief commonly practiced in Vietnam for home and business improvement (Phuong and Groves Citation2010). Mr. Bao’s father decided to fill up the ventilation void to make spaces for a kitchen (). The construction process was similar to that of Mr. Nguyen’s flat. Mr. Bao’s father informally negotiated with the flat owners directly below and above for their consent. He did not hire any professional consultation for the renovation but a local builder due to his limited budget. The changes were done without notifying the local officials. The void was filled up by a concrete slab for the new kitchen, which well serves the family’s everyday needs and business in both functional and spiritual terms.

Figure 11. (Left) floor plan of Mr. Bao’s flat after the changes: 1. Living room 2. Mr. Bao’s private quarter 3. Coffee workshop 4. The void area is used as kitchen space 5. Parent’s room 6. Laundry space 7. Private parking; (Top right) Flat’s owner above filled the void with laminated flooring; (Bottom right) Tools for the coffee workshop (Produced by the authors, 2018).

The physical changes in Flat 220 are another architectural example showing the loosely defined boundary in Vietnamese domestic spaces, which is in line with the ethnographic notion of the threshold of dynamic space (Garvey Citation2005) in the case of Norwegian windows where public and private and indoor and outdoor interactions are noticeable. While Garvey’s analysis of the threshold of dynamic spaces focused more on visual interaction, those at Flat 220 are more physical and functional as home-based retails and other domestic activities, such as coffee making, washing, and drying clothes spill over the public spaces, more specifically, the threshold areas of the flat’s doorstep, the shared corridors, and balconies.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This article has adopted both a historical study and a phenomenological approach to describe and analyze the transformation of domestic spaces with local practices of home-based business in Nguyen Thien Thuat apartment blocks. This empirical analysis further elucidates the theoretical position of phenomenologists, such as (Bachelard Citation1964: 136) and Heidegger (Citation1971: 148) whose studies generally implied that looking closely at building details, room elements, and threshold spaces in a residence and the way it is built, used and altered by its occupants could bring in a deeper knowledge of home as domestic spaces. The case study of changes to interior spaces and building details of Chung Cu as presented in this article has brought in a deeper understanding of the home environment in developing Asian cities like HCMC.

Given the social, economic, and political changes to HCMC, the local practice of home-based business appears to be very resilient and acts as a key contributor to the formation and transformation of domestic spaces in the city. While home-based businesses are integral parts of residential spaces in traditional home settings, such as local shop-houses, they were originally not included in the making of modern home settings, such as the apartment blocks built in HCMC in the 1960s, where thresholds presented clear divisions between public and private spaces. However, as part of the local everyday needs, home-based businesses have been brought into this modern home setting by local residents who have customized the homogenous layout of their flats in response to both the socio-economic changes of the city and specific family business needs. The re-emergence of home-based businesses, even though was up and down due to different levels of government control, is significant as it reinstates the sense of home as a place for both living and family-based businesses in the apartment blocks, which are commonly perceived as a place of residence only.

In this article, our analysis of home-based business through the lens of architecture and spatial practices has added to the existing scholarship on homeworking broadly defined as, for example, economic activity by homeowners at their homes (Felstead and Jewson Citation2000: 15). What is worth noting in the case of apartment blocks in HCMC is that the spatial outcomes of such home economic activities are multifaceted. While spatial organization in Nguyen Thien Thuat apartment blocks generally illustrates Bourdieu’s (Citation1990, Appendix X) spatial thinking that a physical space can be seen as a division between two oppositions, such as private/public, inside/outside and female/male spaces, spatial practices and outcomes of home-based businesses in these apartment blocks seem to present a blurred separation between these spatial oppositions. There seems to be a sense of distinction between female spaces and male spaces in the apartment blocks as the men usually hang around coffee shops located in common spaces, such as the staircase landing, while women often look after home-based businesses. However, the use of threshold spaces, such as shared corridors and walkways as extensions of home-based shops and private tutorial rooms like those in flats 220 and 240 represents undefined boundaries between indoor and outdoor, and public and private spaces.

The conventional perception of home space, as noted by the anthropologist Irene Cieraad (Citation1999: 1–13) is often bound to the popular concept of confined physical spaces and their vivid spatial hierarchy between interior and exterior territories or between public and private realms. However, the distinction between inside and outside or interior and exterior is different when looking at them from a broader cultural context of, for example, non-Western culture, such as the case of Chung Cu in HCMC where the uses of domestic spaces indicate blurred boundaries between private and public realms. This is observable in Chung Cu as local business owners use the shared spaces, such as corridors, landings, and sidewalks outside of their flats as extended shops, private tutorials, private garages, and kitchens. As analyzed earlier these everyday life practices are part of the local culture that, also brings ambiguity to domestic spaces in the more modern home environment of apartment blocks and modulated spaces where the division of public and private, inside and outside, and interiority and exteriority are challenged.

Different natures of home-based businesses imply different spatial experiences and outcomes. As noted earlier, home-based professional works often occur within the interiority and are physically separated from the public sphere (Busch Citation1999). However, home-based businesses as observed in Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat are not bound to the interiority both physically and economically. At the local neighborhood level, home-based businesses are vital to local economies in Chung Cu. They are essential elements of a self-sufficient and inclusive organization of local trading and services ranging from mini convenience stores, coffee shops, barbershops, and restaurants to schooling and clinics. Commonly, local residents get supplies and services for their neighbors. This may be different from the practice of home-based business in apartment living in other places including those from the Western context, where homeworking is more individual as local residents do not expect to get such everyday supplies and services from their neighbors.

Changes to domestic spaces in the apartment blocks in HCMC, as analysed in this article are most observable at the threshold spaces, which both Heidegger and Bachelard, generally defined as spaces where inside and outside or private and public experiences are exchangeable and overlapped. Such spatial condition in the case of Chung Cu is possible via a symbiotic relationship. Even though a symbiotic relationship can be seen in many building changes elsewhere, it is worth noting that such a relationship in Chung Cu is essentially sustained by the local need for home-based businesses. This symbiotic relationship is observable between flat owners whereby one negotiates with another to come out with a workable plan for home renovation to accommodate family-run shops. The symbiotic relationship is also between home-based businesses whereby one service can support and complement others through the local acceptance of private uses over public spaces. The symbiotic relationships between home business owners and associated spatial changes represent a grassroots social practice that is not always noticeable but influential as a key element of home culture in HCMC. It would make sense if the spatial experiences and implications of home-based businesses as discussed in this article can be further elaborated by design and planning professionals in their attempt to propose an appropriate strategy for maintaining and making residential places in Ho Chi Minh City and other cities with similar contexts.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Huynh Tran Buu Loc

HUYNH TRAN BUU LOC RECENTLY FINISHES HIS PH.D. AND CURRENTLY WORKS AS AN ACADEMIC TUTOR AT THE SCHOOL OF DESIGN AND ARCHITECTURE, SWINBURNE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AUSTRALIA. LOC’S RESEARCH FOCUSES ON THE TRANSFORMATION OF LANEWAYS IN HO CHI MINH CITY, VIETNAM. LOC ALSO WORKED PART-TIME AS AN INTERIOR DESIGNER WHILE DOING HIS PH.D. IN MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA.

Dinh Quoc Phuong

DINH QUOC PHUONG (PH.D.) IS THE COURSE DIRECTOR FOR THE INTERIOR ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM AT THE SCHOOL OF DESIGN AND ARCHITECTURE, SWINBURNE UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY, AUSTRALIA. PHUONG’S RESEARCH INTERESTS INCLUDE ARCHITECTURAL CHANGES AND SENSE OF PLACE IN VIETNAM, HOUSING, VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE, THE INFLUENCES OF LOCAL CULTURE ON ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN, AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN VISUAL ART, ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM. HIS RESEARCH HAS BEEN PUBLISHED AS BOOKS, BOOK CHAPTERS, JOURNAL ARTICLES AND CONFERENCE PAPERS INCLUDING THOSE THAT APPEAR IN THE JOURNAL OF INTERIOR DESIGN (SAGE), JOURNAL OF AESTHETICS AND ART CRITICISMS (WILEY), AND IN THE EDITED BOOKS THE AESTHETICS OF ARCHITECTURE: PHILOSOPHICAL INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE ART OF BUILDING (BLACKWELL) AND CRAFT SHAPING SOCIETY (SPRINGER) [email protected]

Notes

1 Interview with Mr. Hien Vu who was a local resident and frequently visited Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat in the 1980s; Interview with Mr. Nguyen and Mr. Bao, long-term local residents in Chung Cu Nguyen Thien Thuat in 2018.

2 Interview with Mr. Nguyen, a local resident living in Chung Cu, 2018.

3 Interview with Mr. Bao, 2018.

4 Interview with Mr. Nguyen in 2018.

REFERENCES

- Bachelard, G. 1964. The Poetics of Space. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Bao, N., et al. 2016. “Saigon – Ho Chi Minh City.” Cities 50: 16–27.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Busch, A. 1999. Geography of Home: Writings on Where We Live. New York, NY: Princeton Architectural Press.

- Centre of Forecast and Urban Studies (PADDI) 2012. Data and Methodology of City’s Analysis. 5–89. (In Vietnamese and French).

- Chen, M., and S. Sinha. 2016. “Home-Based Workers and Cities.” Environment and Urbanization 28 (2): 343–358.

- Cieraad, I. 1999. At Home: An Anthropology of Domestic Space. New York, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Cu, M. C. 2016. How ‘Bright’ the Pearl of Far East was during French colonization? Tuoitre Online. Available from https://tuoitre.vn/vien-ngoc-sai-gon-thoi-thuoc-phap-sang-co-nao-1093378.htm. [In Vietnamese, published on 10/5/2016, Accessed on 26/10/2018].

- Department of Construction of Ho Chi Minh City (So Xay Dung Thanh Pho Ho Chi Minh) 2016. List of Apartment Blocks Built Before 1975. Ho Chi Minh City: Department of Construction Library. (In Vietnamese).

- Felstead, A., and N. Jewson. 2000. In Work, at Home: Towards an Understanding of Homeworking. London: Routledge.

- Fitzgerald, M.A., and M. Winter. 2001. “The Intrusiveness of Home-Based Work on Family Life.”Journal of Family and Economic Issues 22(1): 75–92.

- Garvey, P. 2005. “Domestic boundaries - Privacy, Visibility, and the Norwegian Window.” Journal of Material Culture 10(2): 157–176.

- Ha, M. H. T., J. Rogers, and Q. Stevens. 2019. “The Influence of Organic Urban Morphologies on Opportunities for Home-Based Businesses within Inner-City Districts in Hanoi, Vietnam.” Journal of Urban Design 24(6): 926–946.

- Heidegger, M. 1971. Building Dwelling Thinking. In Poetry, Language, Thought, Edited by M. Heidegger, 145–161. New York: Harper & Row.

- Heyes, J., and A. Gray. 2001. “Homeworkers and the National Minimum Wage: Evidence from the Textiles and Clothing Industry.” Work, Employment & Society 15(4): 863–873.

- Hiep, D. N. 2016a. Saigon Cho Lon: Memories of the City and People. Ho Chi Minh City: Van Hoa-Van Nghe Publishing House. (In Vietnamese).

- Hong, N., and S. Kim. 2021. “Persistence of the Socialist Collective Housing Areas (KTTs): the Evolution and Contemporary Transformation of Mass Housing in Hanoi, Vietnam.”Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 36(2): 601–625.

- Janssen, J. 2016. Living with the Mekong Climate Change and Urban Development in Ho Chi Minh City and the Mekong. Delta, Wageningen: Blauwdruk.

- Lien, H. V. 2013. The Making of Saigon – from the Nguyen Lords to 1954, 1–34. London: British Academy.

- Loi, T.N. 2015. Saigon – Land and People. Ho Chi Minh City: Ho Chi Minh City General Publishing House. (In Vietnamese).

- Lynn, R., and W. Earles. 2006. “Futures’ of Home-Based Business: A Literature Review.” Australasian Journal of Business & Social Inquiry 4(3): 13–28.

- MacLean, K. 2008. “The Rehabilitation of an Uncomfortable past: everyday Life in Vietnam during the Subsidy Period (1975–1986).” History and Anthropology 19 (3): 281–303.

- Petric, B., and S. Bahun. 2020. Homing in on Home. In Thinking Home Interdisciplinary Dialogues. Edited by B. Petric, and S. Bahun. London: Routledge.

- Phuong, D. Q. 2019. “(Re)Developing Old Apartment Blocks in Hanoi: Government Vision, Local Resistance and Spatial Routines.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 18(4): 311–323.

- Phuong, D.Q. 2014. Architecture in Hanoi. In Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Edited by H. Selin. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Phuong, D. Q. 2010. Village Architecture in Hanoi: Patterns and Changes. Hanoi: Science and Technics Publishing House. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3934-5_10241-1

- Phuong, D. Q., and D. Groves. 2010. “Sense of Place in Hanoi’s Shop–House: The Influences of Local Belief on Interior Architecture.” Journal of Interior Design 36(1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1668.2010.01045.x

- Sullivan, C. 2000. “The Intersection of Work and Family in Homeworking.” Households, Community, Work and the Family 3(2): 185–204.

- Sullivan, C. 2003. “What Family Definitions and Conceptualisations of Teleworking and Homeworking.” New Technology, Work and Employment 18(3): 158–165.

- Thai, H. N. 2017. Saigon – from the Pearl of Far East to Ho Chi Minh City. Ho Chi Minh City: Van Hoa-Van Nghe Publishing House. (In Vietnamese).

- Wang, D., and L. Groat. 2013. Architectural Research Methods. New Jersey: Wiley.