ABSTRACT

Background: The popularised notion of models-based practice (MBP) is one that focuses on the delivery of a model, e.g. Cooperative Learning, Sport Education, Teaching Personal and Social Responsibility, Teaching Games for Understanding. Indeed, while an abundance of research studies have examined the delivery of a single model and some have explored hybrid models, few have sought to meaningfully and purposefully connect different models in a school's curriculum (see Kirk, D. 2013. ‘Educational Value and Models-based Practice in Physical Education.’ Educational Philosophy and Theory 45 (9): 973–986.; Lund, J., and D. Tannehill. 2015. Standards-based Physical Education Curriculum Development. 3rd ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.; Quay, J., and J. Peters. 2008. ‘Skills, Strategies, Sport, and Social Responsibility: Reconnecting Physical Education.’ Journal of Curriculum Studies 40 (5): 601–626.). Significantly none, to date, have empirically investigated broader notions of MBP that make use of a range of different pedagogical models in/through the PE curriculum (Kirk, D. 2013. ‘Educational Value and Models-based Practice in Physical Education.’ Educational Philosophy and Theory 45 (9): 973–986.).

Aim: To provide a first empirical insight into using a MBP approach involving several models to teach physical education. At its heart, this paper presents the reader with the realistic and nuanced challenges that arise in striving towards, engaging with, planning for, and enacting a broader, multimodel notion of MBP.

Method: While the study itself was broader, we focus primarily on three units (one using Cooperative Learning, one using a Tactical Games/Cooperative Learning hybrid and a third using Sport Education) taught to boys in two different age groups (i.e. 11–12 and 14–15). Two analytical questions inform and guide our enquiry: (1) What do we learn about MBP implementation through this project that would help other physical education practitioners implement a multimodel MBP approach? and (2) What are the key enablers and constraints of early MBP implementation? Data sources included (a) 21 semi-structured interviews with student groups, (b) teacher post-lesson and post-unit reflective analyses, (c) daily teacher reflective diaries, and (d) teacher unit diaries. Data were analysed comparatively considering the two analytical questions.

Results: The data analysis conveys strong themes around the areas of teacher and student prior learning, working toward facilitating a change in practice, sufficient time to consider changes in practice, and changing philosophies and practices. The results suggest that the consistent challenge that arose for the teacher towards the goal of adopting a MBP approach was the reduction of his overt involvement as a teacher. While the teacher bought into the philosophy of multimodel MBP he was continually frustrated at not progressing as quickly as he would like in changing his practice to match his philosophy.

Conclusions: Despite his best intentions, early attempts to use a multimodel MBP approach were limited by the teacher’s ability to re-conceptualise teaching. The teacher made ‘rookie mistakes’ and tried to transfer his normal classroom practice onto paper handouts while simultaneously inviting students to play a more central role in the classroom. In considering this journey, we can see an indication of the investment needed to implement a MBP approach. Pedagogical change in the form of MBP is a process that needs to be supported by a community of practice intent on improving learning across multiple domains in physical education.

Within the physical education literature, models-based practice (MBP) focuses on the theoretical foundations, teaching and learning features and implementation needs and modifications of particular instructional models (Metzler Citation2011). Research tends to focus on the delivery of a single model, e.g. Cooperative Learning (CL) (Dyson and Casey Citation2012) or Sport Education (SE) (Siedentop Citation1994), taught in isolation. The somewhat limited subject-wide use of MBP has been attributed to the challenges teachers face when using MBP (Casey Citation2014; Metzler Citation2011). At the core of these challenges is the admission by teachers that they lack experience, confidence and competence using MBP and therefore return to their traditional practices (Casey Citation2014; Gurvitch and Blankenship Citation2008) after an initial period of innovation has passed (Goodyear and Casey Citation2015, 186).

A partnership between physical education teacher education (PETE) programmes and schools has been shown to support teachers’ use of MBP (Casey Citation2014) and is an area which has been underserved by the research conducted to date (Fletcher and Casey Citation2014). Several research studies have begun to address this call by examining the delivery of a single model across a PETE programme before enactment in a school context (Deenihan and MacPhail Citation2013). While PETE programmes are providing pre-service teachers with opportunities to experience multiple models, they tend to be delivered as discrete models rather than as multimodel MBP (Deenihan et al. Citation2011).

Such is the prevalence of single model research and practice that the term MBP has become synonymous with single models. Indeed, the popularised notion of MBP is one that focuses on the delivery of a model. The purpose of this paper is to build on the substantial literature in the field on MBP and provide a first empirical insight into using a MBP approach to teach physical education that involves the use of several models. At its heart, this paper presents the reader with the realistic and nuanced challenges that arise in striving towards, engaging with, planning for, and enacting a broader, multimodel notion of MBP. Such a notion allowed students to experience physical education through models selected by the teacher to realise both the needs of the pupils and the requirements of the school's physical education curriculum (in this case Cooperative Learning (CL), Sport Education (SE) and Tactical Games (TG)).

The paper is organised into six sections. In the first section, we discuss MBP. In the second section, we explore two theoretical frameworks (i) legitimate peripheral participation (LPP) and (ii) learning trajectories. The use of these two complementary theoretical frameworks allows us to identify (i) the teacher's learning engagement with MBP as well as (ii) challenging experiences that arise as the teacher progresses towards the successful adoption of MBP. The third section details the methods and data analysis. Fourth, we discuss the results that emerged from the data analysis. Specifically, we discuss four themes (i) teacher and student prior learning, (ii) working toward facilitating a change in practice, (iii) sufficient time to consider changes in practice, and (iv) changing philosophies and practices. In the fifth section, we return to the two frameworks mentioned earlier to investigate and consider the pedagogical journey and associated changes that occurred in the teacher's move towards adopting a multimodel approach to teaching physical education. Finally, we conclude by suggesting that a balance needs to be struck between the aspirations of each pedagogical model, of a MBP approach and the realities of school-life. Single model MBP has not been positioned as a quick fix for physical education and multimodel MBP is likely to be even more complex. Any pedagogical change that takes the form of MBP needs to be supported by a community of practice intent on improving learning across multiple domains in physical education.

Models-based practice

The popularised notion of MBP is one that focuses on the delivery of a single model. Indeed, while an abundance of research studies have examined the delivery of a single model and some have explored hybrid models, few have sought to meaningfully and purposefully connect different models in a school's curriculum (see Kirk Citation2013; Lund and Tannehill Citation2015; Quay and Peters Citation2008). Significantly none, to date, have empirically investigated a broader notion of MBP that makes use of a range of pedagogical models in and across a school's curriculum (Kirk Citation2013). To this end, we believe that MBP, despite the ‘s’ has remained tethered to Metzler’s (Citation2000) notion of ‘model-based’ rather than the broader umbrella notion of ‘models-based’ practice. To this end, we argue that MBP needs to expand to fit a broader frame of reference that includes (but is not limited to) single, multiple and hybrid pedagogical models.

Gurvitch, Lund, and Metzler (Citation2008) argued that MBP encourages the use of a variety of instructional models across the duration of a physical education curriculum. Preferring to use the term ‘multimodel curriculum’ to denote a broader notion of MBP, Lund and Tannehill (Citation2015, 168, original emphasis) note:

A multimodel curriculum is made up of a set of well-selected main theme curricula that stand for something important and that focus on students achieving the goals identified as worth their time and energy (…) if all students are to successfully reach all the standards of a physically educated person when they exit high school, then a multimodel curriculum would provide the criteria to achieve this goal, doing so in innovative and challenging ways.

MBP is recognised as an approach through which significant physical education reform can be made (Kirk Citation2013; Quay and Peters Citation2008). MBP allows for a broader and deeper scope of learning to be achieved than that which one instructional model alone can offer (Lund and Tannehill Citation2015). Several studies have explored integrating/hybridising models, including CL and Tactical Games (TG) (Casey and Dyson Citation2009) and SE and Teaching Games for Understanding (Hastie and Curtner-Smith Citation2006). Other studies have considered connections between a few models (Dyson, Griffin, and Hastie Citation2004; Kirk Citation2013; Quay and Peters Citation2008) but none have empirically explored the use of multiple models across a curriculum (Casey Citation2016). No studies, to date, explore the type of MBP that Kirk (Citation2013, 979) described:

A models-based approach to physical education would make use of a range of pedagogical models, each with its unique and distinctive learning outcomes and its alignment of learning outcomes with teaching strategies and subject matter, and each with its non-negotiable features in terms of what teachers and learners must do in order to faithfully implement the model.

Despite Kirk’s (Citation2013), Quay and Peters (Citation2008) and Lund and Tannehill’s (Citation2015), advocacy of a multimodel curriculum, we must tread carefully. We need the opportunity to unpack, in the way individual models have been unpacked (see Hastie and Mesquite Citation2016), a MBP approach to teaching physical education that involves multiple models. We need to define the learning outcomes we aspire to for physical education (it has been argued elsewhere for physical, social, cognitive and affective (see marked for peer review), align these with different models across a curriculum and examine and reflect on the outcomes. At present, and as Casey (Citation2014) argued, we have repeatedly failed to fundamentally change physical education pedagogy and while MBP is a promising potential future of physical education we need to know a lot more before we commit to this future.

If, as Fullan (Citation2016, 41, original emphasis) argued, ‘effective change processes shape and reshape good ideas, as they build capacity and ownership amount participants’ then it is important that we explore the two components of effective change i.e. ideas (in this case MBP) and capacity/ownership (a teacher's use of a MBP curriculum). If we are to change school physical education pedagogy then the gatekeepers to such change are teachers. It is therefore important to understand not only the challenges and realities teachers face when they set out to implement new ideas in their practice but also the ways in which they gain ownership of such ideas.

Theoretical frameworks

The paper sets out to consider the extent to which the complementary nature of ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ (LLP) and ‘learning trajectories’ theories not only allows us to investigate one physical education teacher's sustained engagement with MBP but also allows us to consider a structure that would help all those involved in the (direct or indirect) delivery of school physical education to adopt a MBP approach.

If MBP is a possible future for physical education, then we need to better understand the ways in which legitimate peripherality and peripheral participants are seen as important. We accept that ‘LPP’ is not necessarily intended to define a single teacher's introduction to, and enactment of, MBP as linear. Indeed, we hold that continual shifts throughout the journey between learning being legitimate, peripheral and involving participation will occur. However, the additional use of ‘learning trajectories’ provides more linearity through the ‘development sequence’ denoting the levels that through as they strive towards adopting a MBP approach. Such linearity may instil in those involved in MBP a greater sense of the feasibility of adopting a MBP approach.

LPP

LPP is proposed as a way of understanding learning, characterising the shifts in learning engagement (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). If we are to move beyond the popularised notion of MBP then it is essential that we learn about the teacher's pedagogical journey and associated changes that occur in teaching physical education. Our collective understanding of how a MBP approach is actualised should be shared and LPP encourages us to do this.

Learning (in this case of MBP) would be considered ‘legitimate’ (authentic and meaningful) when there is an acceptance that the teacher's involvement as a physical education teacher matters to the physical education teaching community's successful performance of its work. Further, if that work is to prepare and support teachers who can deliver meaningful, relevant and worthwhile student learning then it gains some degree of legitimacy. For learning to be legitimate, the teacher must understand their roles and responsibilities – to both young people and the (teaching) community.

There is support for the belief that members must initially be engaged on the periphery of a community to effectively learn the practices of a community. Learning is ‘peripheral’ to the (evolving) community of physical education teachers early in the learning process, with the teacher being introduced (or not) to the support the community can provide. The learning trajectory intensifies with more entrusted activities, expecting to result in the teacher's eventual full participation in the community of physical education teachers.

Learning involves ‘participation’ in experiencing practices within the community. The extent of participation is determined by the type and intensity of exposure to the three dimensions of a community of practice (CoP), i.e. mutual engagement, the negotiation of a joint enterprise and a shared repertoire. Evolving forms of mutual engagement include the possibility for a group of physical education teachers to be involved in the practice of a community while appreciating that there will be different levels of mutual engagement across individual members. Joint enterprise is a collective process of negotiation that is enacted when differing identities and philosophies of physical education teachers lead to conflicting interpretations of what the enterprise is about. A shared repertoire includes routines, ways of doing things, actions or concepts adopted that become part of the practice of a community.

Two related dimensions of LPP are legitimate peripherality and peripheral participants. The notion of ‘legitimate peripherality’ is evidenced when teachers are afforded an opportunity to become more involved, resulting in peripherality as an empowering position. In instances where teachers are kept (legitimately) from participating more fully, peripherality is a disempowering position. Legitimate peripherality crucially involves participation as a way of learning the ‘culture of practice’. Teachers as ‘peripheral participants’ is about teachers being located in the social world, suggesting that there are ‘multiple, varied, more-or-less-engaged and inclusive ways of being located in the fields of participation defined by a community’ (Lave and Wenger Citation1991, 36).

Learning trajectories

Strijker (Citation2010, no page number) defined learning trajectories as ‘a rationalized composition of learning objectives and subjects, leading to a specific learning goal’, usually aligned to a particular curricular or pedagogical context. This has potential to effectively complement our understanding of the teacher in this study who has set out, through identifying particular objectives for his teaching, to work towards a MBP approach aligned with physical education.

By gaining insight into a particular teacher's learning trajectory the intention is to identify challenging experiences/problems that arose through a developmental progression towards the achievement of specific goals (in this case the adoption of a MBP approach). This in turn allows us to consider how to most effectively alleviate such challenges and develop solutions to the problems for future teachers looking to achieve the same specific goals. Continuous learning trajectories provide an insight into what types of transitions are made and when, encouraging teachers interested in similar learning trajectories to develop a skillset aligned to the transitions. This in turn can provide a framework that teachers can use to construe learning trajectories that fit their own teaching contexts (Clements and Sarama Citation2004).

The three elements of learning trajectories (‘goal’, ‘developmental sequence’ and ‘matching activities’) complement the shift in learning engagement denoted by LPP and are used in the following ways in this study. The ‘goal’ is determined as the adoption of a MBP approach to teaching physical education. The ‘developmental sequence’ denotes the levels that teachers move through as they strive towards achieving the goal, with the probability that more complex levels arise as they move towards achieving the goal. ‘Matching activities’ are activities that enhance the teacher's movement from one level to another, informing the scaffolding structure that would allow others to work towards the adoption of a MBP approach.

The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to provide a first empirical insight into a MBP approach to physical education and provide the reader with a scaffolded insight into the realistic and nuanced challenges that arise in striving towards engaging with, planning for, and enacting MBP.

Methods

The study

The data presented in this paper were from a wider research project that explored teacher transformation through pedagogical and curricular change. While the methodology of the wider project was action research it is important to note that this paper only reports on methods and data relevant to the present discussions around using a MBP approach to teach physical education. From the outset, we were interested in better understanding what it takes to instigate a MBP approach in physical education. To this end we developed two analytical questions to inform and guide our analysis: (1) What do we learn about MBP implementation through this project that would help other physical education practitioners implement a multimodel MBP approach? and (2) What are the key enablers and constraints of early MBP implementation? In the sections that follow, we present the methods as they relate to this paper and not the original study.

Setting

Montgomery School (pseudonym), the study site, was a local education department funded selective grammar school in the United Kingdom. The students in the school were predominately white (95.1%), 97.9% had no special educational needs, only 1.2% were eligible for free school meals and only 0.85% did not have English as their first language. Physical education was a compulsory subject in the school and was taught to boys and girls by two separate departments with separate budgets and heads of department. This was a historical ‘hangover’ from the merger of two schools. Only boys were involved in this study.

Participants

Teacher

Author 1 (henceforth referred to as the teacher) was the teacher in this study. At the time of the study he was a qualified physical education teacher with eleven years’ secondary school teaching experience (nine at Montgomery).

Timetable

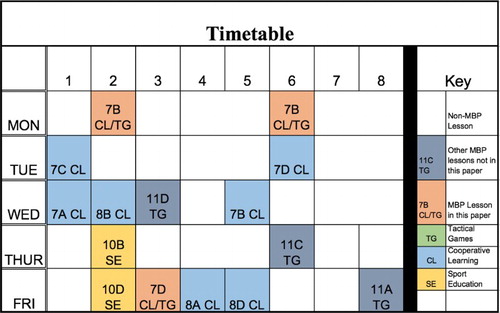

It is important to note that the three units analysed and discussed in this paper were part of the teacher's wider use of MBP (see ). The three units explored are representative of his teaching and focus specifically on three different models: CL, SE and TG. That said, the teacher taught multiple MBP lessons across the curriculum and any and all taught lessons may have been mentioned in the teacher's reflective diaries (see data gathering below) and thus, potential at least, could form part of this study.

Students

Forty-five boys, aged 11–12, from three year 7 classes participated in two units of work which employed a pedagogical models approach. In the first, an invasion games unit was taught through a CL/TG hybrid approach lasting 12 weeks, with one 40-minute lesson a week. Each class was divided into four ‘learning teams’ (Dyson and Grineski Citation2001), each containing three or four boys for the duration of the unit. In the second unit, which used CL and focused on track and field athletics, each class was again split into four learning teams of three or four boys in which the students worked for the duration of the unit. These groups were intentionally different from the groups used in the CL/TG unit. Individual classes are referred to by number and letter (i.e. 7A, 7B and 7D).

Twenty-nine boys, aged 14–15, from two year 10 classes participated in a 12 lesson SE unit (Siedentop Citation1994) focused on football (soccer), with one 40-minute lesson a week. Each class was split into three teams of four to five players. The use of SE for students this age matched the expectation at key stage 4 of the school's physical education curriculum that ‘teaching and learning is not confined to pupils’ personal development as performers’ (Penney et al. Citation2005, 16). This unit was taught over the same time period as the other units. Individual classes are referred to by number and letter (i.e. 10B and 10D).

Models-based practice fidelity

Hastie and Casey (Citation2014) argued that any paper reporting on MBP research should, as a minimum, report on three model fidelity elements: (a) a rich description of the curricular elements of the unit(s); (b) a detailed validation of model implementation; and (c) a detailed description of the programme context that includes the previous experiences of the teacher and students with MBP.

(a) A rich description of the curricular elements of the units

The teacher selected heterogeneous teams in each of the five CL classes. These teams were purposefully selected to ensure that each team contained students across the full ability range. Furthermore, they were selected to ensure they contained neither existing friendships nor rivalries. For Unit 1 (the CL/TG Approach hybrid), the teacher used a planned CL structure, i.e. ‘Learning Teams’, and worksheets copied verbatim from Mitchell, Oslin, and Griffin’s (Citation2013) book Teaching Sport Concepts and Skills: A Tactical Games Approach. For Unit 2, the teacher used a validated unit of CL (Casey, Dyson and Campbell Citation2009). Over the course of both units, teams worked through a carousel of practices/events using modified equipment or rules. The teacher used worksheets as the main source of information and acted in the role of facilitator (Goodyear and Dudley Citation2015).

The year 10 SE unit was an attempt at what Curtner-Smith, Hastie, and Kinchin (Citation2008) referred to as a full version approach to SE (i.e. it was intended to be taught to the model described by Siedentop, Hastie, and van der Mars (Citation2004)). In practice, it was more of a ‘cafeteria’ approach in which the teacher selected key aspects of the model (i.e. a student-led warm up, followed by a student-led skills practice, and concluding with a student-officiated game) to use in the 40-minute lesson. Students adopted the roles of coach, manager, captain, equipment manager and were awarded fair play points for correct kit, being on time, fair play, and officiating.

(b) A detailed validation of model implementation

Metzler (Citation2011) stressed the importance of verifying that any model implemented in physical education led to the intended student lea outcomes. In using worksheets copied verbatim, we believe that the teacher addressed the ‘how of games teaching’ question raised by Mitchell, Oslin, and Griffin (Citation2013, 4) and therefore maintained relatively high fidelity (Hastie and Casey Citation2014) in his use of the Tactical Games Approach. In his use of CL, he ensured that the key features (Goodyear Citation2016) (i.e. positive interdependence, promoted face-to-face interaction, individual accountability, interpersonal and small group skills, group processing, small heterogeneous teams, group goals, and teacher-as-facilitator) were present across the units.

While the SE unit used key aspects of the model, it showed lower fidelity to the full model than the other units. This can be attributed to several reasons, not least to time constraints and the teacher's and the students’ inexperience and unfamiliarity with SE.

(c) A detailed description of the programme context that includes the previous experiences of the teacher and students with the model or with MBP

The CL/TG unit and the CL unit were similarly structured. Week 1 was deployed as a ‘Lesson Zero’ (Dyson and Casey Citation2016, 48) to explain the models and the units to the students. The SE unit was 12 lessons long and no lesson zero was used. Both the CL/TG unit and the SE unit were the students’ first experience of MBP. Prior to the start of the CL unit the students had also been taught using CL in a unit of swimming that lasted 16 weeks. The teacher was both an experienced researcher and an experienced proponent of MBP. At the time of the study he had experience of using CL, SE, and TG. He had taught more than 15 units of work using MBP (across multiple classes and age groups) and had undertaken several research studies over previous years.

Data gathering

The teacher gathered data from group interviews and four different types of field notes: reflective diaries, unit diaries, post teaching reflective analysis (PTRA) (Dyson Citation1994) and post cycle reflective analysis (PCRA) (Casey Citation2010). To maintain their integrity as viable data sources (Hopkins Citation2002), all diaries were written as soon after the lesson as the ‘busyness’ of school allowed.

Ethical approval for this study was sought and granted by the lead author's university's ethics committee. Throughout the study, the teacher was open with the students about his dual roles as a teacher and researcher and their assent and their parents' or guardians' consent was obtained prior to data gathering. No distinction was made between participants and non-participants in lessons but data, in the form of interviews, were only gathered from assenting students.

Interviews

Twenty-one semi-structured group interviews were conducted by the teacher. Students were interviewed at the end of each unit in the teams they worked in for the duration of the unit. The group interviews took place during the physical education lesson immediately after the unit had concluded. They were digitally recorded for verbatim transcription.

Reflective diaries

The reflective diaries served the purpose of a written narrative (Chase Citation2005). A total of 587 days of reflection were captured during the period of the study. These diaries were not specific to an individual unit and as such considered the whole MBP adoption process.

Unit diaries

In an effort to maintain and enhance the focus of these lesson-by-lesson diaries the teacher used Gibbs’s (Citation1988) reflective cycle. This cycle focused on six stages of reflection: (1) Description: what happened? (2) Feelings: what were you thinking about? (3) Evaluation: what was good or bad about the experience? (4) Analysis: what sense can you make of the situation? (5) Conclusion: what else could you have done? and (6) Action plan: if it arose again what would you do?

PTRA and PCRA

The PTRA was developed by Dyson (Citation1994) as a tool which teachers could use to reflect upon the cooperative nature of the individual lessons they taught. It was based around seven questions (or writing cues) that focused on either the teacher or the students: (1) What were your goals for the lesson? (2) What did you see in your lesson that met your goals? (3) What were the most positive aspects of the class? (4) What aspects did you feel did not go well? (5) What changes would you make to the lesson the next time you teach it? (6) Learning outcomes: Did you see learning occur? Specifically what? (7) What are your specific goals for the next lesson? And what strategies will help you achieve your goals? The PCRA contained the same question as the PTRA but was adapted by the teacher to enable him to reflect on the whole unit of work.

Analysis

We began by sorting the data whilst considering the two analytical questions shared earlier. In doing so we highlighted key passages, affixed codes, added reflections and identified phrases, patterns, themes and relationships between data sources. Following this we undertook to systematically read and organise data using inductive analysis and constant comparison (Denzin and Lincoln Citation2005; Lincoln and Guba Citation1985). Findings from this analysis were grounded in the tenets of the action research process – both because this helped us to see what the teacher was doing when implementing MBP in his classes and to identify the enablers and constraints of the implementation. To this end, when we noted things that the teacher had changed or altered we could explore these changes in the data. This interpretive approach was utilised in an attempt to accurately explore the teacher's actions, and the students’ and teacher's responses throughout the process. In this way, and during several independent readings, each text was reduced to a series of complete thoughts and perceptions (Bell, Barrett, and Allison Citation1985).

Next, complete thoughts (ideas emerging from the data that were conceptually consistent) and perceptions (ideas which were arbitrated between the two authors until an agreement to include or exclude was reached) were coded and placed in a series of emerging categories and subcategories. As this process continued, some data were moved from one category to another based on goodness of fit, and preliminary summaries were written to gain an overview of our findings. From these summaries, the categories were consolidated and themes and subthemes were developed. Results from the data analysis convey strong themes around the areas of teacher and student prior learning, working toward facilitating a change in practice, sufficient time to consider changes in practice, and changing philosophies and practices. These themes will now be explored in the results.

Results

Teacher and student prior learning

Unlike the majority of teachers in Curtner-Smith, Hastie, and Kinchin’s (Citation2008) study determining the extent to which newly qualified teachers employed Sport Education, the teacher did not seek to adopt a watered down or cafeteria style approach to MBP. In contrast, while the teacher's post-lesson reflections hint minimally at his prior experience in teaching CL, TG and SE, there is a strong impression that he is continually striving for high fidelity in his use of a MBP approach in his teaching.

The teacher's post-lesson reflections frequently noted that the previous working relationship between the teacher and students heightens students’ awareness of the way the teacher works and the teacher's (changing) expectations (referred by students at times as ‘Mr. X's ideas’). It is noticeable that this prior relationship results in the students possessing ‘pre-requisites’ necessary to engage more fully with the teacher's delivery of MBP, e.g. being attentive and respective of the teacher's ideas, ability to work collaboratively, some experience of problem-solving and discovery.

It was not only student pre-requisite knowledge that was significant but also the teacher's knowledge of his classes. In his unit diaries, PTRA and PCRA he regularly ‘talked’ about his expectations of certain classes and often articulated the ways in which he would pre-empt their actions and reactions. Early in the CL unit he noted,

I knew that 7A would need to be taught to a larger degree than 7B, as they weren't involved in the CL/TG unit. However, they had experience of CL from swimming [a unit not explored in this paper] so, as expected, they took to the idea/framework (at least after a classroom based discussion) quite easily

The influence of the teacher's knowledge of the class was even more obvious with year 10 students (who were in their fourth year at the school) than the year 7 students (who were in their first). The teacher started the SE unit ‘expecting the tomfoolery [naughtiness] (…) [and a feeling that one classes lesson was] always going to be a better lesson than yesterday due to [his] relationship with the group’ (SE Unit Diary, 6 January). He felt that there was ‘almost a hierarchy of who will fool around … like follow-my-leaders’. The students themselves admitted that ‘we tend to mess around and not take as much notice’ (March Interview).

By studying how a MBP approach restructured the classroom, students could articulate different learning outcomes beyond those related only to running, jumping and throwing:

I think all the things we’ve got out of the athletics and things is the fact that now I can get along a lot better with, in groups and because we’ve been doing it in groups and having to help each other out with the sports, so say if somebody doesn't get it right and you’ve got it right you can always help them and help them to get it right and it helps you become more independent as well because you’re having to do it by yourself and then because Mr Casey is helping tell you he doesn't come up to you and say ‘do this’ and then if - he just comes round and lets you get on with it yourself and then if you’ve got something wrong he will come and help you and put you back on the right track and then let you work out what it is again, so it makes you more independent. (July Interview).

Working towards facilitating a change in practice

While the teacher was continually frustrated at not progressing as quickly as he would like in changing his practice to match his philosophy, there was an admittance that he needed to stop being so overly critical of his perceived (lack of) progress. There is a continual acknowledgement of the overt teacher role he exercises and the related challenge of reducing teacher involvement and allowing the students ownership of the lesson and roles within the lesson. The teacher's post-lesson reflections consistently record his frustration for being unable, on numerous occasions, to break away from what he has prepared for each lesson rather than be guided by the ‘readiness’ of the students, ‘(…) the chaos of the classroom almost leaves it to my instincts and this is the part of me that is most difficult to change’ (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7A, 23 January) and

(…) and I took too central a role in the lesson, again (…) Do I not trust the system I have so painstakingly put into place? Or is it the kids I don't trust? Or can I simply not let go? (…) perhaps I need to have more faith in the boys and/or the work that I have done and the experiences that they already have (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7C, 16 January).

[In planning the lesson] I had put all these systems into place and then instead of allowing the pupils to find their own way through the lesson reading the signposts along the way, I have guided them relentlessly (…) I have almost put barriers up myself against their success, willing them to need my support and as such I have suffocated them a little. (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7A, 6 March)

Trust was reciprocal and the students came to value the faith that the teacher placed in them. As one student noted in his group interview:

I think it's also a question of trust, because if we were a class which you didn't think was able to do it, I think it's good that you should be able to make the decision that our class was able to do this, it's good. (March Interview)

An admittance of preparing too much content for lessons appears to add to an overt focus on the teacher, rather than allowing space for the lesson to flow in alignment with the students’ interests and abilities, ‘I will (…) continue to push the boys forward and myself backwards in an effort that my voice becomes more and more distant’ (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7A, 30 January). Making a conscious decision to allow more space in lessons for student involvement resulted in the teacher noting his role as a ‘passenger, an observer, someone who had facilitated this process but now had very little to do with it’ (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7A, 13 March).

There was a tendency for the teacher to favour what he had planned for each lesson as the main criterion against which to evaluate the success of a lesson. The teacher's perceived success of the class appeared to cause a tension between him delivering the class as he had envisaged necessary to be successful and allowing the students to experience what they were/were not capable of doing in working towards what the teacher perceived as success,

They [students] started ok and the roles were quickly defined (…) But when it came to the first coach-led practice everything seemed to go wrong. I didn't have the patience, time, bottle to let things slide for too long and I quickly stepped in (…) I was too quick to get involved, and then too direct in that involvement (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7C, 30 January).

In a bid to counteract this reliance on his perception of what would constitute a successful lesson, the teacher began to make a conscious effort to share the expectations of each lesson with the students, commenting,

(…) I need to explain to them a little clearer my expectations so that there can be no ambiguity as to what the lesson should entail (…) and see if I can't charge them with custody of the lesson and the learning objectives (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7C, 30 January).

Each group approached the lesson in different ways but none of them were incorrect and I had to remind myself of that as the lesson went on. The fact that they didn't comply with my ideal model was difficult for me to deal with at first but I had to tell myself that it wasn't my concern because the lesson is now theirs (…) I must try and get the idea out of my head that there is only one way of completing the lesson, i.e. my way, and allow the boys to do things the way they think is best (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7A, 10 March).

The act of trust was not limited to the teacher's trust in himself and developed, over time, to include ‘faith in both the instructional model and the class themselves. It doesn't matter if it goes wrong but I need to believe that it will go right’ (CL/TG Unit Diary 28 February). This entry is representative of a sense that the MBP approach became less about getting it right and more about believing it was right – both professional and ethically. He repeatedly stated his

intention to give them the control of the lesson – from the warm-up to the reflection – (and …) continue to act as a prompt, a questioner, a conscience, a facilitator, but the emphasis will be on them … there are certain risks attached to this but I must now start to turn more and more of the lesson over to the boys … I am confident (and a little apprehensive) that this will work – they are ready, but am I? (CL/TG Unit Diary, 6 February).

The teacher also noted, at various points in different diaries, the importance of educating students on the roles they were expected to undertake in pedagogical change and providing them with the language and physical skills they would need to enact their roles effectively as well as communicate with their peers and teacher. The teacher did admit that ‘the chosen MBP [i.e. CL and TG] did encourage, more than other MBP, student engagement as part of the learning process’ (Reflective diary, 18 July).

There is also an admittance from the teacher of the length of time necessary to encourage students to be effectively responsible for their own learning and that this, in turn, results in the teacher struggling with the most appropriate time to begin relinquishing their role,

I still think that I need to act as a guide. I would like to relinquish my position of authority but they [students] are not quite ready to go freefall. Time will tell but they are working towards more independence from me and greater dependence on one another (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7A, 6 February).

it [the model] was also successful in prising me out of the centre of the classroom and then allowing me to feel comfortable at the periphery in the role as ball boy and watch-holder rather than the only voice and decision-maker in the room (PCRA, CL/TG Unit).

Many of the lesson goals revolved around students becoming architects of their own learning. This included encouraging student ownership of the lesson, experience in different roles that would contribute to a responsibility for lessons, opportunities to become self-reliant learners and working together. While the teacher's post-lesson reflections did convey an appreciation that the goals of teaching should be focused on the level of meaningful student activity/engagement, it proved difficult for the teacher to favour this at the expense of his own contribution to each lesson. An advantage of encouraging students to be responsible for parts of each lesson was getting to know the students, ‘I have been able to get to know them [students] as individuals (…) what an unexpected but delightful by-product of the whole process’ (Reflective diary, 2 July).

Sufficient time to consider changes in practice

The teacher admitted that ‘(…) time constraints seem to make me a little jittery at first’ (Reflective diary, 17 January). Time is a constant reference point in the teacher's post-lesson reflections, reflective diaries, unit dairies, PTRA and PCRA with respect to being able to achieve more if the physical education lessons were longer than the current time allocation of 40 minutes. This is a somewhat naive perspective, given that more experienced teachers would maintain that it is not the quantity of time that necessarily matters but rather how the time is used. The teacher did begin to move towards considering effective time management towards the end of one unit,

The time scale [of the lesson] allowed for three five minute slots for the boys to work (…) This seems like a silly amount of time in which to achieve anything of real significance and is frustrating but maybe it is as much as these children can cope with at this juncture of their CL learning experiences. Besides that it was a great fifteen minutes (CL/TG Unit Diary, 7A, 13 March).

Interestingly, the teacher admitted that he has been working to 40-minute lessons for the past eight years and that, in recently revisiting and changing his teaching practice and philosophy, he had found himself back in a space where he was trying to achieve too much in the time he had. He points out in his reflective diaries that pedagogical change that is being carefully monitored by the teacher results in a considerable investment of time, in addition to the actual lesson, and that for this reason many teachers may be discouraged from embarking on making changes to their practice. That said, there is clearly a balance that needs to be struck between the aspirations of each model to meet its own set of specific characteristics or elements and the realities of school life, and especially with respect to the length of lessons. This forced the teacher into compromises and a choice between what Casey et al. (Citation2009) called academic and social learning:

The whole experience is - much like CL – improving or meeting their social learning needs, but I am not sure it is benefiting – in the short period of time – their development or performance in football … maybe SE, TG or CL aren't suited to short lessons – maybe there should be a warning with regards to minimum system requirements – I can see the table now … (SE Unit, 10B, 2 February)

Changing philosophies and practices

The teacher's reflective diaries afforded a space for the teacher to focus on his changing philosophy. He noted consistently throughout February's reflective diary entries that he appreciated physical education was an opportunity for students to learn more than skills and techniques,

(…) the ‘how’ and ‘why’ is so much more important than the ‘what’! The method of instruction, the de-centralisation of me and the development of students who can depend on themselves and their peers is far more important than whether or not they can pass in basketball, hockey or Frisbee. Lifelong learning in any physical activity is not necessarily about skill acquisition, it is about gaining skills that last a lifetime (Reflective diary, 23 February).

There was also evidence of a significant pedagogical change in his practices,

(…) one of the main things [to happen to me] has been the unblocking of my ears and the blocking of my mouth (…) we have two ears and one mouth and should use them proportionately (…) I don't [any more] spew out my knowledge at 400 words a minute without pausing for breath. I have gained an appreciation of what the kids have to say as well as their feelings and conceptions about the lesson that they are experiencing (Reflective diary, 16 February).

Discussion

We return to the two frameworks mentioned earlier in the paper to investigate and consider the pedagogical journey and associated changes that occurred in the teacher's move towards adopting a MBP approach to teaching physical education. We accept that ‘LPP’ is not necessarily intended to define such a journey as linear (with continual shifts throughout the journey between learning being legitimate, peripheral and involving participation). ‘Learning trajectories’ provides more linearity through the ‘development sequence’ denoting the levels that teachers move through as they strive towards (successfully) adopting a MBP approach. We explore the traction of both frameworks in turn in considering the results before concluding on the extent to which both complement our understanding of the pedagogical journey.

LPP

For learning to be legitimate, the teacher must understand his or her role and responsibilities (Lave and Wenger Citation1991). There were numerous instances of the teacher conveying this understanding of his role and responsibility in adopting a MBP approach that encouraged student ownership of the lesson and their roles within the lesson. However, accompanying such instances, and in keeping with previous research (Casey Citation2014), the teacher noted a high level of frustration in enacting appropriate roles and responsibilities due to his previous preferred practice of maintaining a high level of teacher involvement in classes rather than allowing students a level of ownership of the lesson.

The continual striving of the teacher to change his practice to match the philosophy of MBP resulted in continual shifts between learning as legitimate and learning as peripheral. The level of support the teacher was striving to provide was to be substantially reduced (in his mind) if he was to be successful in delivering MBP that was to be more reliant on student leadership and ownership than that of the teacher (Goodyear Citation2017). The teacher struggled at times to determine the appropriate level of support. Interestingly, the increase of entrusted activities expected for learning to be peripheral focused more on how the teacher could encourage student leadership and ownership than on his own exposure in lessons. That is, the teacher's learning trajectory intensified through enacting and upholding practices that encouraged students, more than the teacher, to be responsible for student-directed learning. This finding is reflective of Kirk and MacPhail’s (Citation2002) and Kirk’s (Citation2005) expectation that students’ motivation would be enhanced if their learning experiences were made more authentic and meaningful. Given that the peripherality of the teacher was an empowering position in encouraging student-directed learning, this is an example of legitimate peripherality.

Given that the teacher was attempting to adopt a MBP approach on his own with no formal support from fellow teaching colleagues (acknowledging that there was support of a different kind from a university PhD supervisory team), the opportunity for him to feel that he was in some way experiencing practices within the physical education community was limited. Consequently, related to the participation component of LPP, elements of the three dimensions of a community of practice (mutual engagement, the negotiation of a joint enterprise and a shared repertoire) were more reliant through his engagement with students than with teaching colleagues. The teacher continually shared the expected teacher and student roles and responsibilities with the students, clearly striving to develop practices he had previously instilled in the student (Harvey and Pill Citation2016). The teacher's belief that what students take away with them from a lesson, and not necessarily a focus on teaching practices, should be the criteria for successful learning, supports the notion of peripheral participation acknowledging that there are varied ways of being located in participating in the field of teaching (and the associated community).

Learning trajectories

The results convey that the consistent challenge that arose for the teacher towards the goal of adopting a MBP approach was the reduction of his overt involvement as a teacher (Goodyear and Dudley Citation2015). While the teacher had bought into the philosophy of the MBP approach he wished to introduce, he continually struggled to reduce his overt teacher role to allow for student ownership of the lesson and associated roles within the lessons. While he could identify instances where he should have ‘stepped back’ from the activities of the class and subsequently noted how to address this for the next class, he was still unable, on numerous occasions, to enact the preferred practices if he was to encourage more student ownership of the lesson (Pill, Swabey, and Penney Citation2017).

It was not until he began to share the expectations of each lesson with the students, and allow some flexibility on the expectations aligned with what the students believed they were capable of doing, that we begin to see a transition to more space for student-directed learning. Aligned with this was the teacher’s developing acceptance that students may find different ways (from each other and the teacher) of achieving the goals of the lesson. There was eventually an acceptance for the teacher that he could not, and should not, ensure that there was a level of intense regularity for each lesson. This resulted in significant pedagogical change. Interestingly, for this teacher, the most complex level in the developmental sequence of working towards enacting the MBP approach was finding ways in which to reduce his direct interventions into student learning. Put different, he struggled most when trying to adopt the role of facilitator of learning (Goodyear and Dudley Citation2015).

The teacher's pedagogical journey provides us with some insights into activities that enhanced his movement towards supporting a MBP approach to teaching physical education. First he had previously worked with the same group of students which resulted in the students being cognizant of what the teacher expected from the students and what they could expect from him (Casey Citation2013). Second was the investment the teacher had made in not only researching the MBP approach he wished to pursue but also in wholeheartedly believing in the associated pedagogical philosophy that was necessary for its successful delivery. Third was the ability to identify instances where he did and did not practice pedagogies associated to the MBP approach, to reflect on these and consider appropriate changes to his practice. Fourth was what we have previously noted as the main ‘transition’ in the pedagogical journey, i.e. sharing the expectations of each lesson with the students with an acceptance that there may be multiple ways in which to achieve the stated goal(s) of the lesson. Finally, was the realisation that such changes to ingrained pedagogical practices take time not only for the teacher to address but also for the students to embrace (Fletcher and Casey Citation2014).

Conclusion

The implementation of a MBP approach to teaching and learning in physical education has implications for several audiences: (i) physical education teachers considering engaging with a MBP approach, (ii) physical education teacher educators who intend to work with physical education teachers and pre-service teachers interested in introducing a MBP approach in their schools, (iii) pre-service teachers exposed to a MBP approach, and (iv) physical education CPD providers. This paper is a first step to beginning to understand both MBP implementation per se and the key enablers and constraints of early MBP implementation.

Despite the best intentions of the teacher, early implementation was limited by his ability to re-conceptualise teaching. He made ‘rookie mistakes’ and tried to transfer his normal classroom practice to paper while simultaneously inviting students to play a more central role in his classrooms. There simply was not enough space (in any of his lesson or units) for both the teacher and the student to have a significant voice in the pedagogical process. While his aim may have been legitimate peripherality and peripheral participation, his voice was too central in the process to allow for either. It was not until he replaced the idea of real teaching with an aspiration for real learning that he quietened his own voice and came to value the student-centred approach at the heart of all the models he was using.

In considering this journey, we can see an indication of the investment needed to implement a MBP approach in the pedagogy of physical education. While research increasing calls for such an approach we need to be cognisant of what it entails. Author 1, as an experienced teacher-as-researcher, was well positioned to make the transition towards MBP and yet he struggled over a sustained period of time. A balance needs to be struck between the aspirations of each model of a MBP approach and the realities of school-life. Single model MBP has not been positioned as a quick fix for physical education and multimodel MBP is likely to be even more complex. Any pedagogical change that takes the form of MBP needs to be supported by a community of practice intent on improving learning across multiple domains in physical education. This paper is the first to provide a first empirical insight into using a MBP approach to teach physical education that involves the use of several models. There is much work to be done, but a focus on real learning and a desire to align ‘learning outcomes with teaching strategies and subject matter’ (Kirk Citation2013, 979) is certainly a starting point.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Ashley Casey http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8232-5727

References

- Bell, R., K. R. Barrett, and P. C. Allison. 1985. “What Preservice Physical Education Teachers See in an Unguided, Early Field Experience.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 4: 81–90. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.4.2.81

- Casey, A. 2010. “Practitioner Research in Physical Education: Teacher Transformation Through Pedagogical and Curricular Change.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Leeds Metropolitan University.

- Casey, A. 2013. “‘Seeing the Trees not Just the Wood’: Steps and not Just Journeys in Teacher Action Research.” Educational Action Research 21 (2): 147–163. doi: 10.1080/09650792.2013.789704

- Casey, A. 2014. “Models-based Practice: Great White Hope or White Elephant?” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (1): 18–34. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2012.726977

- Casey, A. 2016. “Models-based Practice.” In Routledge Handbook of Physical Education Pedagogies, edited by C. D. Ennis, 54–67. London: Routledge.

- Casey, A., and B. Dyson. 2009. “The Implementation of Models-based Practice in Physical Education Through Action Research.” European Physical Education Review 15 (2): 175–199. doi: 10.1177/1356336X09345222

- Casey, A., B. Dyson, and A. Campbell. 2009. “Action Research in Physical Education: Focusing Beyond Myself Through Cooperative Learning.” Educational Action Research 17 (3): 407–423. doi: 10.1080/09650790903093508

- Chase, S. E. 2005. “Narrative Inquiry: Multiple Lenses, Approaches, Voices.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 3rd ed., 651–679, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Clements, D. H., and J. Sarama. 2004. “Learning Trajectories in Mathematics Education.” Mathematical Thinking and Learning 6 (2): 81–89. doi: 10.1207/s15327833mtl0602_1

- Curtner-Smith, M. D., P. A. Hastie, and G. D. Kinchin. 2008. “Influence of Occupational Socialization on Beginning Teachers’ Interpretation and Delivery of Sport Education.” Sport, Education and Society 13 (1): 97–117. doi: 10.1080/13573320701780779

- Deenihan, J. T., and A. MacPhail. 2013. “A Pre-service Teacher’s Delivery of Sport Education: Influences, Difficulties and Continued Use.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 32 (2): 166–185. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.32.2.166

- Deenihan, J. T.,A. MacPhail, and A.-M. Young. 2011. “‘Living the Curriculum’: Integrating Sport Education into a Physical Education Teacher Education Programme.” European Physical Education Review 17 (1): 51–68. doi: 10.1177/1356336X11402262

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 2005. “Methods of Collecting and Analyzing Empirical Materials.” In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 3rd ed., 641–650. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dyson, B. 1994. “A Case Study of Two Alternative Elementary Physical Education Programs.” Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University.

- Dyson, B., and A. Casey. 2012. Cooperative Learning in Physical Education: A Research Based Approach. London: Routledge.

- Dyson, B., and A. Casey. 2016. Cooperative Learning in Physical Education and Physical Activity: A Practical Introduction. London: Routledge.

- Dyson, B., L. L. Griffin, and P. Hastie. 2004. Sport Education, Tactical Games, and Cooperative Learning: Theoretical and Pedagogical Considerations.” Quest (grand Rapids, Mich) 56 (2): 226–240.

- Dyson, B., and S. Grineski. 2001. “Using Cooperative Learning Structures to Achieve Quality Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation, and Dance 72: 28–31. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2001.10605831

- Fletcher, T., and A. Casey. 2014. “The Challenges of Models-based Practice in Physical Education Teacher Education: A Collaborative Self-study.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 33 (3): 403–421. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2013-0109

- Fullan, M. 2016. The New Meaning of Educational Change. 5th ed.London: Routledge.

- Gibbs, G. 1988. “Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods.” Accessed May 30 2009. http://www2.glos.ac.uk/GDN/gibbs/ch4_3.htm.

- Goodyear, V. A. 2016. “Sustained Professional Development on Cooperative Learning: Impact on Six Teachers’ Practices and Students’ Learning.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2016.1263381.

- Goodyear, V. A. 2017. “Sustained Professional Development on Cooperative Learning: Impact on Six Teachers' Practices and Students' Learning.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 88 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1080/02701367.2016.1263381.

- Goodyear, V. A., and A. Casey. 2015. “Innovation with Change: Developing a Community of Practice to Help Teachers Move Beyond the ‘Honeymoon’ of Pedagogical Renovation.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 20 (2): 186–203. doi:10.1080/17408989.2013.817012.

- Goodyear, V. A., and D. A. Dudley. 2015. ““I’m a Facilitator of Learning!” Understanding What Teachers and Students do Within Student-Centered Physical Education Models.” Quest (grand Rapids, Mich) 67 (1): 274–289.

- Gurvitch, R., and B. T. Blankenship. 2008. “Implementation of Model Based Instruction - The Induction Years.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 27 (4): 529–548. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.27.4.529

- Gurvitch, R., J. L. Lund, and M. W. Metzler. 2008. “Researching the Adoption of Model-based Instruction - Context and Chapter Summaries.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 27 (4): 449–456. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.27.4.449

- Harvey, S., and S. Pill. 2016. “Comparisons of Academic Researchers’ and Physical Education Teachers’ Perspectives on the Utilization of the Tactical Games Model.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 35 (4): 313–323. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2016-0085

- Hastie, P. A., and A. Casey. 2014. “Fidelity in Models-based Practice Research in Sport Pedagogy: A Guide for Future Investigations.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 33 (3): 422–431. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.2013-0141

- Hastie, P. A., and M. D. Curtner-Smit. 2006. “Influence of a Hybrid Sport Education—Teaching Games for Understanding Unit on One Teacher and his Students.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 11 (1): 1–27. doi: 10.1080/17408980500466813

- Hastie, P. A., and I. Mesquite. 2016. “Sport-based Physical Education.” In Routledge Handbook of Physical Education Pedagogies, edited by C. D. Ennis, 68–84. London: Routledge.

- Hopkins, D. 2002. A Teacher’s Guide to Classroom Research. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Kirk, D. 2005. “Future Prospects for Teaching Games for Understanding.” In Teaching Games for Understanding: Theory, Research, and Practice, edited by L. L. Griffin and J. I. Butler, 213–227. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Kirk, D. 2013. “Educational Value and Models-based Practice in Physical Education.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 45 (9): 973–986. doi: 10.1080/00131857.2013.785352

- Kirk, D., and A. MacPhail. 2002. “Teaching Games for Understanding and Situated Learning: Rethinking the Bunker-Thorpe Model.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 21 (2): 177–192. doi: 10.1123/jtpe.21.2.177

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S., and E. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Lund, J., and D. Tannehill. 2015. Standards-based Physical Education Curriculum Development. 3rd ed.Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett.

- Metzler, M. W. 2000. Instructional Models for Physical Education. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway.

- Metzler, M. W. 2011. Instructional Models for Physical Education. 3rd ed. Scottsdale, AZ: Holcomb Hathaway.

- Mitchell, S. A., J. L. Oslin, and L. L. Griffin. 2013. Teaching Sport Concepts and Skills: A Tactical Games Approach for Ages 7 to 18. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Penney, D., G. D. Kinchin, G. Clarke, and M. Quill. 2005. “What is Sport Education and Why is it Timely to Explore it?”.” In Sport Education in Physical Education, edited by D. Penney, G. Clarke, M. Quill, and G. D. Kinchin, 3–22. London: Routledge.

- Pill, S., K. Swabey, and D. Penney. 2017. “Investigating Physical Education Teacher Use of Models Based Practice in Australian Secondary PE.” Revue phènEPS / PHEnex Journal 9 (1): 1–17.

- Quay, J., and J. Peters. 2008. “Skills, Strategies, Sport, and Social Responsibility: Reconnecting Physical Education.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 40 (5): 601–626. doi: 10.1080/00220270801886071

- Siedentop, D. 1994. Sport Education. Quality PE Through Positive Sport Experiences. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Siedentop, D., P. A. Hastie, and H. van der Mars. 2004. Complete Guide to Sport Education. Leeds: Human Kinetics.

- Strijker, A. 2010. “Leerlijnen en vocabulaires in de praktijk (Learning Trajectories and Vocabularies in Practice) (in Dutch).” Accessed February 16 2017. http://redactie.kennisnet.nl/attachments/2214570/Leerlijnen-en-vocabulaires-in-de-praktijk.pdf.