ABSTRACT

Background: How teachers enact policy has been of significant interest to educational scholars. In physical education research, scholars have identified several factors affecting the enactment of policy. These factors include but are not limited to: structural support available for teachers, provision of professional development opportunities, the nature of the policy, and the educational philosophies of the teachers. A recurring conclusion drawn in this scholarship is that official documentation and teachers’ work often diverge, sometimes in profound ways.

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to investigate how physical education teachers in Sweden describe their enactment of policy regarding the concept complex movement, which features in the latest Swedish curriculum.

Methods: Interview data were generated with six specialist physical education teachers. Three questions guided the interviews: What is complex movement? What is not complex movement? And, can you give examples from your teaching of complex movement? Data were analyzed using a discourse analytic framework. Meaning was understood as a production of dialectical relationships between individuals and social practices. Two key concepts were utilized: intertextuality, which refers to the condition whereby all communicative events, not merely utterances, draw on earlier communication events, and interdiscursivity, which refers to discursive practices in which discourse types are combined in new and complex ways.

Results: We identified three discourses regarding the teachers’ enactment of policy: (1) Complex movement as individual difficulty, (2) Complex movement as composite movements, and (3) Complex movement as situational adaptation. Several features were common to all three discourses: they were all related to issues of assessment; they suggested that complex movement is something students should be able to show or perform, and; they left open room for practically any activity done in physical education to be considered complex.

Discussion: Three issues are addressed in the Discussion. The first concerns the intertextual nature of the teachers’ statements and how the statements relate to policy and research. The second concerns the way that knowledge, and specifically movement knowledge, becomes problematic in the teachers’ statements about complex movement. The third concerns more broadly the language used to describe the relationship between policy and practice.

Conclusions: We propose that modest levels of overlap between teachers’ discursive resources, policy, and research is unsurprising. In line with earlier research, we suggest that the notion of ‘enactment’ is a more productive way to describe policy-oriented practice than notions such as ‘implementation’ or ‘translation’, which imply a uni-directional, linear execution of policy.

Introduction

The formulation and transformation of new educational policy has been described as a challenge for physical education practice (Brown and Penney Citation2013; Macdonald Citation2013; Penney et al. Citation2009; Thorburn and Collins Citation2006). Enright and O'Sullivan (Citation2012) for example, suggest that policy transformation is rarely straightforward. Examining how PE teachers translate ‘practical experiential’ principles into performance-led practice, Thorburn and Collins (Citation2003) suggest that there exist ‘profound disparities’ between official documentation and teachers’ work (1). Penney (Citation2013) too, suggests that a number of factors affect how practitioners eventually implement policy. Investigating the enactment of Health and Physical Education in the Australian Curriculum, Penney (Citation2013) suggests that policy actors, agencies, policy artefacts and indeed, the interaction between these factors, play a critical role in determining how curricula come to be expressed and experienced (see also Alfrey and Brown Citation2013; DinanThompson Citation2013; Lambert Citation2018). This multifaceted transformation process from policy to practice has lately been problematized in terms of policy enactment (Ball et al. Citation2012; for research in PE see e.g. Brown and Penney Citation2017; Lambert and Penney Citation2019).

Again, in an Australian context, Alfrey, O'Connor, and Jeanes (Citation2017) investigate how three teachers transform policy into practice. The authors claim that the structural support available for teachers and learners, along with the time available for training and development are crucial factors to consider when practitioners are implementing new policy, especially if the policy challenges teachers’ existing philosophies. Alfrey, O'Connor, and Jeanes (Citation2017) suggest that given the multiple alternatives for understanding and teaching health and physical education, it is unlikely that calls for faithful implementation from academia and policy-makers will amount to much unless there is an appreciation for teachers’ philosophies and school cultures. The authors conclude that while policy itself creates a particular context, it is the ideologies and histories that permeate teachers’ philosophies and school context that will ultimately determine how policy finds form in practice.

As well as contextual factors, curriculum coherence has received attention. In the case of Scottish physical education, Thorburn (Citation2007) suggests that an underpinning mind–body dualism in the curriculum prevents policy and practice from reflecting one another very closely. In this case, Thorburn proposes that official policy contains inconsistencies and needs reconsideration. In an Australian context, Leahy, O'Flynn, and Wright (Citation2013) examine how the concept of ‘critical inquiry’ is used in different ways and with differing intentions in the same document. To show how these differences result in diverse practices, the authors present examples of HPE preservice teachers’ employment of critical inquiry in their teaching during their final professional experience.

We agree with assertions of the importance of socio-political context, and find it somewhat surprising that much of the curricular research focusing on PE has come from only a handful of English-speaking countries. In line with Englund and Quennerstedt (Citation2008), we propose that curricular research from different contexts can contribute to existing scholarship and provide understandings beyond the particulars of each country. The purpose of this paper is thus to investigate how physical education teachers in Sweden describe their enactment of policy regarding the concept complex movement, which features in the latest Swedish curriculum. We intend to explore the logic that structures teachers’ transformations as well as render the essentially contested concept (Englund and Quennerstedt Citation2008) of complex movement open to further discussion.

Complex movement in the Swedish curriculum

The latest edition of the Swedish national curriculum in 2011 (Lgr11) was supposed to address criticisms leveled at its predecessor. Namely, it was supposed to provide clear, practical guidance for practitioners regarding knowledge requirements and it was supposed to facilitate equivalent national grading (Svennberg, Meckbach, and Redelius Citation2014). Research conducted since 2011 suggests that the curriculum has not met expectations. Redelius, Quennerstedt, and Öhman (Citation2015) suggest that some Swedish PE teachers find it difficult to articulate learning objectives and students have difficulties stating what they are supposed to learn in physical education. Similarly, Svennberg, Meckbach, and Redelius (Citation2014) claim that PE teachers do not always make curricular grading criteria explicit for students and sometimes use criteria more as a way to manage classroom situations than to facilitate learning.

At least part of the problem appears to stem from new terms and concepts that were introduced in the curriculum in 2011. Several of these terms carry particular significance for Swedish physical education because they directly regulate grading and, as a result, teaching content (Redelius, Quennerstedt, and Öhman Citation2015; Tolgfors Citation2018). These terms have been referred to as ‘value terms’ in curricular support material. In this paper, we want to focus on the value term complex movement since it occupies an important place in the knowledge requirements and grading section of the curriculum but is at the same time left largely undefined. We have noted in earlier work that complex movement has caused considerable frustration in professional circles (Janemalm, Quennerstedt, and Barker Citation2019). The results of our earlier research suggest that the Swedish curriculum supports constructions of complex movement as:

(i) simple and for everyone but also quite specific where particular ways of moving are privileged, (ii) … contextual-bound and mainly emerging in discussions of sport or assessment, and (iii) … about knowledge, however it is not clear if knowledge needs to be articulated in words in order to be authentic. (Janemalm, Quennerstedt, and Barker Citation2019, 11)

In the next section, we review scholarship on current understandings of complex movement within PE. We then outline our methodological approach, summarizing principles of discourse analytic thinking and describing interviewing as research method. Our results follow and we present and discuss the key ideas that structure how the participants enacted complex movement. We finish by exploring how their ideas relate to other movement education discourses.

Complex movement

Movement learning has received a great deal of attention from scholars in recent times (see e.g. Barker, Bergentoft, and Nyberg Citation2017; Rönnqvist et al. Citation2019). In this literature, the term ‘complex’ occurs relatively frequently as a descriptor of both how learning occurs and how moving occurs (e.g. Janemalm, Quennerstedt, and Barker Citation2019; Jess, Atencio, and Thorburn Citation2011; Nyberg and Larsson Citation2014; Ovens Citation2010). Brown (Citation2013) for example, uses Arnold’s conceptualization of movement to describe the complexity of learning in, through and about learning while other scholars investigating knowledge and movement have discussed how moving can be understood as complex (e.g. Nyberg and Carlgren Citation2015; Rönnqvist et al. Citation2019). In this paper, we focus on complex movement rather than the complexity of learning. In this section, we recognize three related ways of making sense of movement complexity in the literature and provide a brief description of each. First, complex is used to connote advanced. In this usage, complex is used to distinguish between ‘fundamental’ or ‘basic’ ways of moving that are learned in earlier years and more sophisticated ‘complex’ ways of moving done later in education (Delaš, Miletić, and Miletić Citation2008; Rukavina and Jeansonne Citation2009). Complex here is connected to notions of progression and development (see e.g. Stodden et al. Citation2008) and is used to mean more ‘mature’ (Miller, Vineand, and Larkin Citation2007, 63). Alone, this connotation is not enough to tell us what complex movements might look like in practice, but combined with the following aspects, a more detailed picture begins to emerge.

Some scholars use ‘complex’ to signify that the movement is taking place in specific contexts or situations that place certain demands on the mover (e.g. Chow et al. Citation2007). A general overhand throwing movement for example, might be done in a variety of different places and can thus be referred to as a fundamental movement (Drost and Todorovich Citation2013). A javelin-throw, in contrast, with its specific grip and run up and the fact that it belongs to an athletics context, is an example of a complex movement. Complexity appears in situations where particular responses, defined by others, are expected of the mover. A corollary is that complexity is possible only when a context allows for different movements but demands one. From this perspective, a teacher can remove a situation’s potential for complexity either by not allowing different movements and demanding only one (in a drill type activity, for example) or by not demanding any specific movement response at all (as in some forms of creative dance or play, for example).Footnote1

Finally, some scholars use the term complex movement to signal that some sort of reflection or problem solving is involved in the activity. Chow et al. (Citation2007) for example, propose that ‘learning would be optimized if students were engaged in complex and meaningful problem-based activities’ (252, our emphasis). These claims are part of a wider logic about student centeredness and the possibilities students have for influencing their learning and moving.

In short, complex movements are generally understood as advanced ways of moving. Complexity is often further tied to context, with complexity increasing as potential for change or adaptation increases. Some scholars have also claimed that for movement to be complex, some sort of cognitive activity or reflection must be involved. These ways of understanding complexity could function as discursive resources on which physical educators draw upon in their transformation of policy to practice. In the next section, we outline our methodological approach through which we can address this proposition.

Methodology

In this section, we describe how we investigated Swedish physical education teachers’ transformation of policy into practice regarding an essentially contested concept – complex movement. We draw on principles of discourse analysis, an approach that has proven useful when exploring the significance of utterances and investigating collective meanings and practices in general (e.g. Taylor Citation2013) and in physical education (e.g. Barker and Rossi Citation2011). Below we provide descriptions of our theoretical framework, our participants, our data production procedures, and our analytical process.

Discourse theory as a base for discourse analysis

A central idea in discourse analysis is that meaning depends on, and changes with, context (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002; Taylor Citation2013). From this perspective, meaning is socially embedded (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002) and knowledge is regarded as situated, contingent and fluid. ‘Reality’ is influenced by different representations, an idea that challenges a traditional positivist ontological standpoint (Seale Citation1999). In an important sense, language constitutes ‘reality’ and discourses can be seen as different realities through which we live. Discourses are thus ‘ … patterns of meaning which organize the various symbolic systems human beings inhabit, and which are necessary for us to make sense to each other’ (Parker Citation1999, 3). In this paper, we assume that teachers’ interpretations of curricular concepts like complex movement have their roots in existing discourses of physical education, sports and health and that these discourses can potentially be identified and traced in terms of their historical roots.

One of the major goals of discourse analysis is to delineate the specific rules that structure the production of meanings in different contexts. In our case, we are attempting to analyze the term complexity as it relates to movement, trace the discourses the statements are part of, and also challenge or interrupt its taken-for-grantedness. By considering how PE teachers draw on different discourses to describe their enactment of policy, we hope to reveal something of the term’s socio-historical logic.

Related to historicity, two key concepts are important in our analysis: intertextuality and interdiscursivity (Fairclough Citation1992). Intertextuality describes the condition by which utterances, spoken or written, reference or draw on earlier communication. Fairclough (Citation1992) points out that one cannot avoid using words and phrases that others have used before. The analytic value of intertextuality is in its invitation to consider where discursive resources such as words, phrases and ideas have been borrowed from. Interdiscursivity on the other hand, refers to discursive practices in which discourse types are combined in new and complex ways. The analytic value of interdiscursivity is in its invitation to consider how different discourses and genres articulate with one another in a communicative event so that boundaries are changing and new discursive possibilities are being formed. Discursive reproduction and change can thus be examined by comparing the relations between different discourses (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002). In this investigation, for example, teachers’ statements were examined for how they related to other formal texts such as the Swedish curriculum and support material, as well as previously described research and how the teachers were combining resources in new or unexpected ways.

The participants

Data were produced with six physical education teachers. The teachers were selected because they had been appointed ‘first teachers’ (förstelärare). This position is comparable to ‘head of department’ in other countries. It comes with a responsibility for promoting professional and academic development and first teachers are often in charge of in-service training, subject meetings and so forth. In Sweden, ‘first teachers’ are appointed by the principal usually because they have shown a special interest or knowledge in an area. First teachers can for example, be subject-, overall IT- or special needs specialists. As they have this academic development duty, we suggest that ‘first teachers’ are likely to have reflected on the curriculum and other policy documents and will thus be able to describe concepts of the curriculum in detail.Footnote2

The process of choosing our interview participants can best be described as a combination of purposively selecting ‘first teachers’ in physical education as a target group for the reasons described above and ‘convenience sampling’ (Patton Citation2002) since we used an existing network of ‘first teachers’ presented to us. Contact information to find ‘first teachers’ was initially provided by municipality administrations. Then, as there is not a great number of ‘first teachers’ in physical education, the network of ‘first teachers’ in physical education was used to find participants. In the end, the sample consisted of six respondents from five schools (two of the teachers worked at the same school but one was responsible for the junior school and the other, the senior).

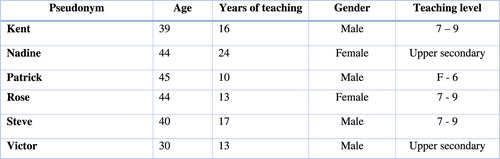

All participants were qualified teachers, which meant that according to Swedish law, they were eligible to provide final grades for the students. Four male and two female teachers were included in the sample. Three of the teachers were teaching physical education in years 7–9 (students aged 13–15 years). Two of the teachers were working in upper secondary school (years 10–12 – students aged 16–18 years) and one was teaching primary years (F-6 – students aged 6–12 years). All respondents gave their informed consent before data production began. Respondents’ names have been replaced with pseudonyms ().

Data collection using interviews

In line with other research aimed at understanding how physical education teachers have made sense of taken-for-granted concepts (e.g. Barker and Rossi Citation2011), we approached teachers directly and asked them through interviews about complex movement as it relates to their practices. An active interviewer’s role was used (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002) where prepared questions were followed with probing questions and requests for clarification, examples and elaboration. We regarded interviewing as a form of social interaction in which the interviewer and the respondent work together to produce the interaction. The interviews can most accurately be described as in-depth and semi-structured (Brinkmann Citation2014) although with three prepared questions, the interviews were loosely structured. All respondents were asked to discuss the following questions:

What is complex movement?

What is not complex movement?

Can you give examples from your teaching of complex movement?

The rationale for having relatively open interviews was to enable the interviewees to steer the interviews as much as possible. This was deemed especially important given that the investigation’s objective was to get close to the ways the teachers enacted complex movement in practice. The interviews were designed to give the respondents opportunities to express themselves freely and follow their own associations. The interviewer attempted to respond to and ask follow-up questions in response to the participants’ statements. The interviews were audio recorded and lasted between 44- and 53-minutes. All interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Analytical process

Initially, the transcripts were read as a whole by all authors to develop familiarity with the empirical material. As the reading progressed, the teachers’ statements were highlighted and grouped broadly in terms of whether they dealt with: (i) what students are supposed to do in order to demonstrate complexity, or (ii) the situations or practices in which certain movements occur for them to be considered complex. Once initial reading and broad categorization had taken place, preliminary discourses in the data were identified. The preliminary discourses were then discussed in the research team in relation to existing scholarship on movement complexity as well as the national curriculum using what has been labeled a ‘deliberative strategy’ (Goodyear, Kerner, and Quennerstedt Citation2019). If a preliminary discourse appeared in several of the teachers’ statements and in the research or curricula statements, it was demarcated as a discourse in terms of intertextuality. Preliminary discourses were also checked for whether they involved a combination of existing discourses in a way that we had not previously identified. In other words, they were checked to see if they could be considered interdiscursive (Fairclough Citation1992). Remaining statements were discarded. All identified discourses were then discussed within the research team to evaluate their discursive logic in terms of what students are expected to do and what actions and practices are included or excluded in each discourse.

As well as close reading of the individual transcripts, the ‘deliberative’ analysis involved comparing the interview transcripts with one another, based on the structuralist idea that statements gain their meaning by being different from something else (Saussure Citation1915). The process of describing how two things are different from one another helped us to develop more refined pictures of the various discourses. Substitution, or exchanging a word or a phrase with a different word or phrase (Jørgensen and Phillips Citation2002) was also used as an analytic strategy during discussions of the data. The term ‘complex’ for example, could in some places be exchanged with ‘complicated’ or ‘difficult’. Through this process, three discourses on complex movement in physical education were finally identified and agreed upon.

Results

In the analysis, we identified three discourses regarding the teachers’ descriptions of their policy enactment: (1) Complex movement as individual difficulty, (2) Complex movement as composite movements, and (3) Complex movement as situational adaption. Even if the discourses are analytically distinctive in that the teachers appeared to be using separate logics in their enactment of these discourses, there are some common features. We would suggest therefore, that all three discourses are embedded in a comprehensive discourse on complex movement. First, they are all related to issues of assessment. Indeed, complexity seems to be of interest mainly because it should be assessed and graded in relation to the national curriculum. Second, complexity is primarily about something students should be able to show or perform. In this sense, complexity is observable at most points of most PE lessons. Third, complexity can potentially be related to any activity done in physical education.

Below are descriptions of the identified discourses. They are presented in terms of how the discourse is built up, the actions that should be performed for movements to be complex, as well as the specific activities or practices that are complex. Illustrative quotes from the teacher interviews are used to demonstrate the construction of the discourse.

Complex movement as individual difficulty

As a discourse, ‘complex movement as individual difficulty’ concerns how certain movements or activities are experienced as difficult by individual students. When employing this discourse, teachers often drew on a range of ‘difficult activities’ to highlight complexity. Kent for example, stated that a very complex movement was ice skating: ‘That is almost the most difficult thing you can do … ’. Similarly, Rose noted that it is:

different movements that many think are somewhat difficult to put together … And in that moment, it is probably when I explain to the students, that today we are going to work with complex movement specifically.

What movements are non-complex?

I was just sitting and thinking about that as we were talking and I became like, I was thinking quietly. Everything we do is really complex movements. So, anything from relaxation to being able to walk to …

But it is a complex movement also to be able to lie still, know how to relax, know how to focus on oneself. (Kent)

Complex movement as composite movements

A number of the teachers’ statements also cohered around the idea of complex as an amalgamation of movements. Specifically, complex movements were ones that involve a combination of different aspects. Aspects may relate to smaller ‘sub-movements’, such as a run up, a jump, and a landing. Combination however, may also relate to the physiological and coordinative aspects of movement such as strength, balance, oxygen uptake, body control, timing, duration, power, direction, and rhythm. In the teachers’ descriptions, when a person must put several aspects together, the movement becomes complex.

Several respondents used dance as a typical example in their deployment of the complexity as composite movement discourse. The following extract from Patrick’s interview demonstrates the cumulative logic of the discourse:

That becomes a variable of its own?

Yes, that is one, the rhythm. And then we shouldn’t even talk about dancing with a girl for instance. Then to be able to perform the motor steps, perform them and put it all together, then it becomes very tough.

It becomes complex?

To say the least.’

Also using dance, Steve employs the idea of combination to develop the notion of complexity. He suggests that,

Again, you put together many movements that will generate something. To just go this way slowly back and forth, back and forth, is not very complex. But then you should get into the beat, the rhythm, a little feeling, choreography. That makes it more complex. It is, again, many more aspects that need to adapt to each other. You should deliver a dance that should look good, it should be in pace, it should be choreographed and more and I think that makes it more complex than that I go back a bit slowly, I swing a little back and forth to music.

But what does the game really mean? Well, you should go from A to B and then you should collect an item at B and take it back to A. Although you have added 100 variables in between there, so it will be very difficult.

Complex movement as situational adaptation

This final discourse suggests that certain movement situations are complex because the required response is not known to the learner in advance. In other words, learners need to adapt their responses as the activity proceeds. Several teachers drew on the idea of problem solving to develop this kind complexity. Often the notion of cooperative work appeared in examples of this discourse. Nadine for example, suggested that:

When they should solve a problem, a station for instance, when you are about to clear an obstacle without touching things and … you get to help each other. That can be complex. And it becomes more or less complex depending on your role in the group.

Ball games were frequently used as examples of situations in which required responses were unknown. The teachers referred to ball games as always changing, and suggested that the students needed to show their readiness to meet different scenarios on the playing field. As in the problem-solving description, the students adapt their movements to game situations and it is within this adaptation the complexity lies. Linda stated:

… And it's very complex from just being one against one, to pass the ball, to being five players on the court where I need to relate to the court’s surface. Where should I be positioning myself in order to get open, for example, becomes a very complex situation.

This discourse involves the idea that complexity is related to certain responses students should do in relation to specific predefined situations. It also provides a kind of spectrum of complexity in that movements can become increasingly complex when more variables are added. Jogging on a running track for instance could be described as less complex than running in a forest since it involves less situational adaptation.

Discussion

While there are a number of points that can be raised about these results, we would like to develop our discussion around three issues we see as particularly relevant to existing scholarship. They concern: (1) connections between the identified discourses, disciplinary perspectives on movement, and curriculum; (2) the ways in which understandings of knowledge and assessment are embedded in teachers’ transformation of policy to practice, and; (3) the support the results provide for understanding and researching the policy-practice relationship as a matter of policy enactment rather than a linear and hierarchical process of policy implementation.

We would like to begin by noting that the discourses drawn on by the teachers in their transformation of policy to practice have moderate levels of intertextuality with both existing scholarship on movement and movement complexity, and the Swedish curriculum. The idea that complex movement is context-dependent and involves reacting, responding and adapting to (changing) environments is prevalent across the different textual fields. The teachers’ references to situational adaptation were entirely congruent for example, with research that suggests that complexity is concerned with decision making in dynamic contexts (Chow et al. Citation2007; Drost and Todorovich Citation2013). The Swedish curriculum also states that pupils will be able to ‘vary and adapt their movements to some extent to activities and context’ in order to achieve an ‘E’ in year nine (Skolverket Citation2011).

This correspondence is not surprising. Despite research indicating the presence of wide gaps between policy and practice (e.g. Thorburn and Collins Citation2003; Thorburn Citation2007), we would expect to find areas of agreement. What deserves attention is why consensus gathers around this particular theme. Our discourse analytic reading is that because ‘dynamic contexts’ is often used synonymously with ‘sport and game contexts’ (Janemalm, Quennerstedt, and Barker Citation2019), the teachers’ deployment of this specific discourse represents a reproduction of a comprehensive ‘physical education as sport and games’ discourse. In Fairclough’s (Citation1995) terms, the teachers’ use of this discourse to explain complex movements is a mark of continuity and stability for the school subject. In this respect, the results provide insight into how physical education reproduces itself as (predominantly) team sports and games (see Kirk Citation2010). We can see for example, that when new terms such as ‘complex movement’ are introduced into curricula, there is potential for discursive development and change. That change is largely absent in our results suggests that complex movement has been successfully integrated within the existing logic of the school subject and shaped by the power relations at work in the policy context (Ball et al. Citation2012).

There are of course multiple discourses that contribute to the idea of physical education that is presented in official curricula – it is not only ‘sport and games’ (see Leahy, O'Flynn, and Wright Citation2013). We would propose that complex movement as ‘experienced by individuals as difficult’ and as ‘being made up of smaller sub-movements’ are intertextually related to other discourses within the field of physical education: the first fits with a student-centeredness discourse (Leahy, O'Flynn, and Wright Citation2013) while the second fits with a fundamental movement discourse the distinguishes between basic and advanced ways of moving (e.g. Rukavina and Jeansonne Citation2009).

The discourse deployed in the Swedish curriculum (see Janemalm, Quennerstedt, and Barker Citation2019) but least developed in the teachers’ accounts however, relates to knowledge. The curriculum suggests that it is the combination of knowledge and understanding that makes movement complex (Skolverket Citation2011), a logic rehearsed by scholars who propose that reflection and problem solving are vital aspects of moving in complex ways (Avery and Rettig Citation2015; Chow et al. Citation2007). For us, the Swedish curriculum’s introduction of complex movement can be seen as an interdiscursive event (Fairclough Citation1992) and an invitation for practitioners to form new discursive possibilities: namely new ways to think about and practice knowledge in movement. That the teachers had difficulties implicating knowledge in their explanations suggests a tension or lack of textual fit between knowing on the one hand and moving in physical education on the other. This difficulty is in line with Redelius et al’s claims that some Swedish PE teachers find it challenging to articulate learning objectives in general and that ‘throughout history, physical education has been regarded as a “practical” subject, with a focus on doing’ (Citation2015, 641, emphasis in the original). Indeed, given the subject’s history, it is unsurprising that complex movement has become a pedagogical sticking point. It is easy to imagine teachers’ frustration with complex movement when issues of movement and knowledge become entwined with demands for assessment and grading and where there is an expectation from school authorities, parents and students of national equivalence (Svennberg, Meckbach, and Redelius Citation2014).

One interpretation of the results is that knowing – and therefore the assessment of knowledge – is still often framed as an aspect related to the mind rather than the body (or mind and body – see Nyberg [Citation2014] for a discussion of movement as a form of practical knowledge). This explanation closely resembles Thorburn’s (Citation2007) observations made more than a decade ago. Our sense is that discrepancies between dualistic and holistic approaches to physical education are at the root of a number of debates within the field, debates which continue to transcend national boundaries. In terms of a way out of recurrent discussions, what appears necessary is the combination of discourses in new ways. Here we can be quite explicit: the field of physical education needs to develop ways to combine discourses of knowing and moving in ways such that it is possible to ‘think’ of movement as being knowledgeable (see also Nyberg Citation2015). Such ways of thinking and acting could open up opportunities for evaluating and assessing the knowledgeability of moving.

Finally, the data provide support for policy-practice relationships to be understood by researchers and practitioners, as a matter of policy enactment rather than a linear and hierarchical process of implementation (Penney Citation2013). The consistencies and inconsistencies between teachers and curriculum identified in this investigation suggest that terms like ‘transfer’, ‘translate’, ‘implement’ and even ‘transform’ (at least when used in a linear and one directional way) fail to adequately describe how teachers work with policy in physical education (see also Ball et al. Citation2012). Our sense is that teachers’ frustration around complex movement (Janemalm, Quennerstedt, and Barker Citation2019) – at least in part – arises precisely from the common sense belief that policy should be transferred, translated or be ‘faithfully implemented’ uni-directionally to practice (see Alfrey, O'Connor, and Jeanes Citation2017). This belief discourages teachers from developing their own pedagogical practices but simultaneously ties them to policy statements that are flexible and contestable. Policy enactment suggests a different relationship in which teachers interpret and accomplish curricula in the enactment process. It would seem however, that such an approach would need to be communicated to teachers as well as educational policy organizations. Indeed, the convergence and divergence of teachers’ deployment of discourses with curriculum and movement scholarship and the confusion that has arisen around this issue suggests that open discussions of policy and practice, whether they concern complex movement or any other aspect of physical education, need to take place. Such discussions need to be structured and well supported with time and resources, and would in our view, alleviate concerns and allow teachers to get on with the business of teaching as a matter of policy enactment.

Conclusion

The purpose of this paper was to investigate how physical education teachers in Sweden describe their enactment of policy regarding the concept ‘complex movement’, which features in the latest curriculum. Through a discourse analytic approach, we have demonstrated how experienced PE teachers describe complex movement as: (i) movement that individual students find difficult to perform, (ii) composite movements that are made up of smaller sub-movements, and as, (iii) movements that require context-specific adaptation. Against a background of curriculum theoretical scholarship, we have suggested that: (i) situational adaptation is a key way of making sense of complex movement, and one that is closely linked to traditional views of physical education as sport and games; (ii) references to knowledge that are present in curriculum formulations are largely missing from teachers’ descriptions of complex movement; and (iii) teachers’ dissatisfaction with complex movement as a curricular term is closely related to the notion that curricular concepts should be implemented, transferred or translated. This dissatisfaction becomes particularly acute in assessment and grading contexts. We proposed that the notion of curriculum enactment, which has been discussed for some time now in education and physical education scholarship could be a way to move beyond some of the concerns that arise with the introduction of new policy.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

ORCID

L. Janemalm http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1226-6813

D. Barker http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4162-9844

M. Quennerstedt http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8748-8843

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In many cases, complex tends to suggest that the context is dynamic and changing. This understanding of complexity leads to the term being associated with games and sports (see e.g. Drost and Todorovich Citation2013; Overdorf and Coker Citation2013). References to decision-making and tactical understanding are also made when this approach to complexity is adopted (Avery and Rettig Citation2015; Chow et al. Citation2007).

2 See https://www.skolverket.se/kompetens-och-fortbildning/larare/karriartjanster-for-larare for more details on ‘first teachers’.

References

- Alfrey, L., and T. D. Brown. 2013. “Health Literacy and the Australian Curriculum for Health and Physical Education: A Marriage of Convenience or a Process of Empowerment?” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 4 (2): 159–173. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.805480

- Alfrey, L., J. O'Connor, and R. Jeanes. 2017. “Teachers as Policy Actors: Co-creating and Enacting Critical Inquiry in Secondary Health and Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 22 (2): 107–120. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2015.1123237

- Avery, M., and B. Rettig. 2015. “Teaching the Middle School Grade-Level Outcomes with Standards-Based Instruction.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 86 (7): 17–22. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2015.1064697

- Ball, S. J., M. Maguire, A. Braun, K. Hoskins, and J. Perryman. 2012. How Schools do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary Schools. London: Routledge.

- Barker, D., H. Bergentoft, and G. Nyberg. 2017. “What Would Physical Educators Know About Movement Education? A Review of Literature, 2006-2016.” Quest 69 (4): 419–435. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2016.1268180

- Barker, D., and A. Rossi. 2011. “Understanding Teachers: The Potential and Possibility of Discourse Analysis.” Sport, Education and Society 16 (2): 139–158. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2011.540421

- Brinkmann, S. 2014. “Unstructured and Semi-Structured Interviewing.” In The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by P. Leavy, 277–299. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brown, T. D. 2013. “A Vision Lost? (Re) Articulating an Arnoldian Conception of Education ‘in’ Movement in Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 18 (1): 21–37. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2012.716758

- Brown, T., and D. Penney. 2013. “Learning ‘in’, ‘Through’ and ‘About’ movement in Senior Physical Education? The New Victorian Certificate of Education Physical Education.” European Physical Education Review 19 (1): 39–61. doi: 10.1177/1356336X12465508

- Brown, T. D., and D. Penney. 2017. “Interpretation and Enactment of Senior Secondary Physical Education: Pedagogic Realities and the Expression of Arnoldian Dimensions of Movement.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 22 (2): 121–136. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2015.1123239

- Chow, J. Y., K. W. Davids, C. Button, R. Shuttleworth, I. Renshaw, and D. Araújo. 2007. “The Role of Nonlinear Pedagogy in Physical Education.” Review of Educational Research 77 (3): 251–278. doi: 10.3102/003465430305615

- Delaš, S., A. Miletić, and D. Miletić. 2008. “The Influence of Motor Factors on Performing Fundamental Movement Skills – The Differences Between Boys and Girls.” Facta Universitatis: Series PE and Sport 6 (1): 31–39.

- DinanThompson, M. 2013. “Claiming ‘Educative Outcomes’ in HPE: The Potential for ‘Pedagogic Action’.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 4 (2): 127–142. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.801106

- Drost, D. K., and J. R. Todorovich. 2013. “Enhancing Cognitive Understanding to Improve Fundamental Movement Skills.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 84 (4): 54–59. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2013.773838

- Englund, T., and A. Quennerstedt. 2008. “Linking Curriculum Theory and Linguistics: The Performative Use of ‘Equivalence’ as an Educational Policy Concept.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 40 (6): 713–724. doi: 10.1080/00220270802123938

- Enright, E., and M. O'Sullivan. 2012. “Physical Education ‘in All Sorts of Corners’.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 83 (2): 255–267.

- Fairclough, N. 1992. Discourse and Social Change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Fairclough, N. 1995. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. Essex: Longman.

- Goodyear, V. A., C. Kerner, and M. Quennerstedt. 2019. “Young People’s Uses of Wearable Healthy Lifestyle Technologies; Surveillance, Self-Surveillance and Resistance.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (3): 212–225. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2017.1375907

- Janemalm, L., M. Quennerstedt, and D. Barker. 2019. “What is Complex in Complex Movement? A Discourse Analysis of Conceptualizations of Movement in the Swedish Physical Education Curriculum.” European Physical Education Review 25 (4): 1146–1160. doi:10.1177/1356336X18803977.

- Jess, M., M. Atencio, and M. Thorburn. 2011. “Complexity Theory: Supporting Curriculum and Pedagogy Developments in Scottish Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 16 (2): 179–199. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2011.540424

- Jørgensen, M., and L. J. Phillips. 2002. Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method. London: Sage.

- Kirk, D. 2010. Physical Education Futures. London: Routledge.

- Lambert, K. 2018. “Practitioner Initial Thoughts on the Role of the Five Propositions in the New Australian Curriculum Health and Physical Education.” Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education 9 (2): 123–140. doi: 10.1080/25742981.2018.1436975

- Lambert, K., and D. Penney. 2019. “Curriculum Interpretation and Policy Enactment in Health and Physical Education: Researching Teacher Educators as Policy Actors.” Sport, Education and Society. doi:10.1080/13573322.2019.1613636.

- Leahy, L., G. O'Flynn, and J. Wright. 2013. “A Critical ‘Critical Inquiry’ Proposition in Health and Physical Education.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 4 (2): 175–118. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.805479

- Macdonald, D. 2013. “The new Australian Health and Physical Education Curriculum: A Case of/for Gradualism in Curriculum Reform?” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 4 (2): 95–108. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.801104

- Miller, J., K. Vineand, and D. Larkin. 2007. “The Relationship of Process and Product Performance of the Two-Handed Sidearm Strike.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 12 (1): 61–76. doi: 10.1080/17408980601060291

- Nyberg, G. 2014. “Exploring ‘Knowings’ in Human Movement: The Practical Knowledge of Pole-Vaulters.” European Physical Education Review 20 (1): 72–89. doi: 10.1177/1356336X13496002

- Nyberg, G. 2015. “Developing a ‘Somatic Velocimeter’ – The Practical Knowledge of Freeskiers.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 7 (1): 109–124. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2013.857709

- Nyberg, G. B., and I. M. Carlgren. 2015. “Exploring Capability to Move – Somatic Grasping of House-Hopping.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 20 (6): 612–628. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2014.882893

- Nyberg, G., and H. Larsson. 2014. “Exploring ‘What’ to Learn in Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (2): 123–135. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2012.726982

- Ovens, A. 2010. “The New Zealand Curriculum: Emergent Insights and Complex Renderings.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 1 (1): 27–32. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2010.9730323

- Overdorf, V. G., and C. A. Coker. 2013. “Efficacy of Movement Analysis and Intervention Skills.” The Physical Educator 70 (2): 195–205.

- Parker, I. 1999. Critical Textwork: An Introduction to Varieties of Discourse and Analysis. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Patton, M. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Penney, D. 2013. “From Policy to Pedagogy: Prudence and Precariousness; Actors and Artefacts.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 4 (2): 189–197. doi: 10.1080/18377122.2013.808154

- Penney, D., R. Brooker, P. Hay, and L. Gillespie. 2009. “Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment: Three Message Systems of Schooling and Dimensions of Quality Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 14 (4): 421–442. doi: 10.1080/13573320903217125

- Redelius, K., M. Quennerstedt, and M. Öhman. 2015. “Communicating Aims and Learning Goals in Physical Education: Part of a Subject for Learning?” Sport, Education and Society 20 (5): 641–655. doi: 10.1080/13573322.2014.987745

- Rönnqvist, M., H. Larsson, G. Nyberg, and D. Barker. 2019. “Approaching Movement Learning: Understanding Learners’ Sense-Making in Movement Learning.” Curriculum Studies in Physical Education and Health. doi:10.1080/25742981.2019.1601499.

- Rukavina, P. B., and J. J. Jeansonne. 2009. “Integrating Motor-Learning Concepts into Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation and Dance 80 (9): 23–65. doi: 10.1080/07303084.2009.10598391

- Saussure, F. 1915. Course in General Linguistics. New York: Colombia UP.

- Seale, C. 1999. The Quality of Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Skolverket. 2011. Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and the Leisure- Time Centre 2011 (Lgr 11). www.skolverket.se/publikationer.

- Stodden, D. F., J. D. Goodway, S. J. Langendorfer, M. A. Roberton, M. E. Rudisill, C. Garcia, and L. Garcia. 2008. “A Developmental Perspective on the Role of Motor Skill Competence in Physical Activity: An Emergent Relationship.” Quest 60 (2): 290–306. doi: 10.1080/00336297.2008.10483582

- Svennberg, L., J. Meckbach, and K. Redelius. 2014. “Exploring PE Teachers’ ‘Gut Feelings’: An Attempt to Verbalise and Discuss Teachers’ Internalised Grading Criteria.” European Physical Education Review 20 (2): 199–214. doi: 10.1177/1356336X13517437

- Taylor, S. 2013. What is Discourse Analysis? London: Bloomsbury.

- Thorburn, M. 2007. “Achieving Conceptual and Curriculum Coherence in High-Stakes School Examinations in Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 12 (2): 163–184. doi: 10.1080/17408980701282076

- Thorburn, M., and D. Collins. 2003. “Integrated Curriculum Models and Their Effects on Teachers’ Pedagogy Practices.” European Physical Education Review 9 (2): 185–209. doi: 10.1177/1356336X03009002004

- Thorburn, M., and D. Collins. 2006. “The Effects of an Integrated Curriculum Model on Student Learning and Attainment.” European Physical Education Review 12 (1): 31–50. doi: 10.1177/1356336X06060210

- Tolgfors, B. 2018. “Different Versions of Assessment for Learning in the Subject of Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (3): 311–327. doi: 10.1080/17408989.2018.1429589