ABSTRACT

Background

The world experienced challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic which resulted in school closures across the globe in early 2020. Schools pivoted to remote delivery of learning using a variety of online and offline resources. PE is vital in providing motor development opportunities for children and it is essential to ensure that the provision of quality PE experiences is continued, even in the context of a pandemic. It was in this context that the PE at Home lessons were developed.

Purpose

This study examined teachers' and parents’ experiences of using the PE at Home resource and contributes to documenting the PE home-learning experience and can inform how the education system might respond and incorporate remote teaching into the future.

Methods

A mixed-methods study utilising online surveys with 29 teachers and 173 parents/guardians and online interviews with five teachers, five parents and seven resource developers was undertaken. Quantitative data were descriptively analysed while qualitative data were analysed using a thematic approach (Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101).

Findings

The PE at Home lessons had excellent viewership with over 27,000 Facebook and 937 website views. Three themes (i) ensuring the ‘E’ remained in PE; (ii) home-schooling and physical education; (ii) and context and relatability were developed from the data. While some parents demonstrated that their knowledge of PE was that it consisted of physical activity, other parents along with teachers and developers reflected on the educative component of the lessons. The PE at Home lessons provided teachers with a resource to share with parents to support parents home-school during Covid-19 school closures. An Irish resource featuring Irish children and aligned with the Irish curriculum was seen as a strength by both parents and teachers.

Conclusion

The PE at Home lessons address the teaching and learning of PE in multiple contexts, particularly in an online environment, and they can be used in multiple ways to promote learning.

Introduction

The world has and is experiencing extraordinary, life-altering challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic resulted in school closures across the globe in early 2020, aimed at limiting the spread of the virus. Primary schools in Ireland closed their doors in March 2020 and stayed closed for the remainder of the 2019–2020 academic year under government directive, reopening in September 2020. Schools pivoted to remote delivery of learning using a variety of online and offline resources. Availability of resources for online teaching of primary PE was limited, and even fewer available to support parents home-school their children. The current study aimed to examine teachers’ and parents’ perceptions of a particular home-schooling resource for physical education (PE) ‘PE at Home’ during the COVID-19 pandemic, within the Irish context. While this study was undertaken in an Irish context, findings may be applicable across the world as, according to Griggs and Petrie (Citation2018, 329), the ‘tenets of tradition with the impacts of globalisation appear to have led to limited variation in [PE teaching] practice across countries … .and many of the challenges for primary school physical education are common’.

Although distance, or online teaching, in recent years has become more popular and generally results in similar academic outcomes as traditional teaching (Bernard et al. Citation2004; Cavanaugh et al. Citation2004), many questions remain surrounding online delivery of PE. Notably, the efficacy of online PE in delivering widely agreed PE learning outcomes is not known (Killian, Kinder, and Woods Citation2019). Despite the lack of comprehensive research evidence of its efficacy, challenges of online PE are easy to conceive. While online learning is possible to organise for subjects that do not require a lot of motion, PE by definition is based on movement. Quennerstedt (Citation2019) outlines worrying trends where in some countries the ‘E’ is being pushed out of physical education, as well as describing how the ‘P’ is also being eroded by greater priority being placed on other curricular areas. It is clear that challenges related to both the ‘P’ and the ‘E’ of physical education in an online and home-schooling context also exist. Daum and Woods (Citation2015) deemed the development of motor skill proficiency via online PE to be difficult, and believed that online PE should not be targeted at elementary aged children. In addition to the challenges relating to developing children’s motor skills, PE teachers have expressed concerns over student accountability, safety, assessment, and overall quality of online PE (Daum and Buschner Citation2012; Mohnsen Citation2012).

With school closures and large-scale changes to the delivery of education, online instruction has allowed for learning opportunities beyond the traditional classroom, albeit not without challenges. PE in Ireland is taught by generalist teachers, similar to other countries, alongside 11 other subjects further highlighting the challenges faced by these teachers in providing online support for parents tasked with home-schooling their children. In addition, the very fact that parents/guardians were intermediaries in the teaching process was additionally challenging for teachers, parents and students. PE is recognised within the primary school curriculum as being an ‘integral part of the educational process, without which the education of the child is incomplete’ (Department of Education and Science Citation1999, 2). The availability of curriculum-relevant PE resources for teaching PE in a primary school context is vital and may go some way to navigate the possibilities in providing more ‘P’ and more ‘E’ in primary physical education.

It was in this context that the PE at Home lessons were developed, the primary aim being to provide a resource that was relevant to the curriculum and could be used in the home environment. In the case of the PE at Home lessons an individual watches a sequence of visual and auditory learning cues modelled in a video recording by a peer or an instructor and then tries to perform the entire skill in a similar or alternative setting without additional prompting (Bellini and Akullian Citation2007; Mechling Citation2005). There is also evidence that demonstrates students’ increased motivation to learn (e.g. Choi and Johnson Citation2005) and improvement in skills as a result of participating in online learning experiences (Berge and Clark Citation2005). Quality PE provides children with the opportunity to develop their physical literacy (Van Acker et al. Citation2011; Coulter and Woods Citation2011), a holistic term that encompasses not only physical competence but the confidence, motivation, and knowledge and understanding needed to be physically active throughout the lifespan (Keegan et al. Citation2019). Children who develop their physical literacy are more likely to engage in PA as adolescents (Britton et al. Citation2020).

The development of fundamental movement skills (FMS) is a key element of the primary school PE curriculum. FMS mastery in young children is associated with lifelong physical activity (PA) (Holfelder and Schott Citation2014), better health related fitness (Lubans et al. Citation2010), and improved physical, emotional, and cognitive development (Piek et al. Citation2008). Considering the importance of PE in providing development opportunities for children, it is essential to ensure that the provision of quality PE experiences is continued, even in the context of the current global pandemic. It was in this context that the PE at Home lessons were developed. While the pandemic was the global event that led to this resource, there will continue to be national disasters which may affect children’s education (such as earthquakes, bush fires and tsunamis). This resource and the findings from this study may inform parents, teachers and policy makers, how to support children’s PE learning remotely in such cases. The aim of this study was to generate practically meaningful knowledge through examining parents’ and teachers’ experiences and perceptions of engaging with the PE at Home resource.

Methodology

In line with pragmatic research philosophy, which considers that researcher biases and preferences can be used to support novel insights, this study was aided by our experience as educators in PE and sport (Giacobbi, Poczwardowski, and Hager Citation2005) whereby we were driven by practical questions and methods and considered ourselves as co-constructors of knowledge. As such, we considered a mixed methods approach as most appropriate to address the aims of the study. Through a mixed methods approach the research investigated aspects relating to accessibility and suitability, frequency of use, perceived quality, potential future use, and impact of the resources from the perspective of parents and teachers within the Irish context. While the purpose of this study centred on teachers and parents’ experiences of using the PE at Home resource, the data collected more broadly contributes to documenting the PE home-learning experience throughout a period of school closure, and can inform how education systems worldwide might respond and incorporate remote teaching into the future, and indeed approach the development of online resources to support PE.

PE at Home lesson development

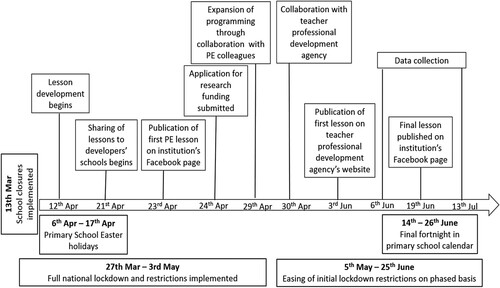

During the initial COVID-19 school closures anecdotal evidence suggested that teachers employed predominantly physical activity (PA) resources that were available online and easily shared. While many of these resources promoted PA, most lacked the educational element essential to PE, did not align with their PE curriculum, and therefore did not allow for continuity of learning during the school closures. The first PE at Home lessons were developed by the first and last authors, in response to a local need for PE resources during the closures. It subsequently expanded to service a broader range of strands and age groups with the inclusion of two further lesson developers. A timeline of the development and subsequent research of the PE at Home lessons is presented in . All members of this initial lesson development team were qualified PE teachers and academics involved in Physical Education Teacher Education at the same university, and had primary school-aged children in their households with whom to develop and record the lessons during lockdown. Initially, lessons were shared via email (Google Drive links) with teachers who were within the developers’ contact networks.

As the project expanded and requests for access increased, the authors’ institutional Facebook page was used as a platform to make the PE at Home lessons more widely available. A partnership with the Professional Development Service for Teachers (PDST), the state body responsible for the continuing professional development of teachers in Ireland and a collaboration with the Irish Heart Foundation also saw the lessons being shared through their networks. Three members of the PDST who are generalist primary school teachers with additional qualifications in primary PE, joined the PE at Home lesson development team to expand the lessons to encompass all remaining class groupings and curriculum strands on the Irish PE curriculum. Lessons were developed using an agreed structure and format, formulated by the first and last authors in consultation with the lesson development team. Guiding principles for the lesson structure were outlined as follows:

Scaffold lessons within the curricular strands and appropriate class groupings to build on existing knowledge

Include health-related learning

Use minimal equipment and space

Short duration of 8–12 min

Lesson introduction to include lesson topic and learning outcomes

Lesson summary to include health-related activity message, and offer lesson development and activity extenders to try

Include child(ren) as learners, where possible

Include appropriate ‘fun’ challenges

Inclusion of open-ended questions and guided discovery technique

This partnership led to the PE at Home lesson suite being published on Scoilnet (www.scoilnet.ie), the Department of Education and Skills official education portal.

Study design, participants, and measures

Reflecting the pragmatic philosophy above, qualitative and quantitative methods were utilised. Two surveys were created using Qualtrics (Provo, UT), one for primary school teachers and one for parents/guardians of primary school children. The surveys contained questions on six primary topic areas; (i) barriers to use, (ii) lessons and strands used, (iii) resource quality, (iv) physical literacy outcomes, (v) future use, and (vi) other PE resources used. The surveys were administered online and were shared across multiple platforms including those on which the PE at Home lessons were available (e.g. Facebook, Scoilnet), as well as via email to teachers who had engaged with the lessons. The survey was completed by 29 teachers (TS) and 173 parents/guardians (PS).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with PE at Home lesson developers (Dev), primary school teachers (T), and parents/guardians (Par) of primary school children, to provide a deeper insight into their perceptions of the PE at Home lessons. The interview schedule for developers contained 15 questions focusing (i) consideration of Covid-19 restrictions when developing lesson content, (ii) purpose and structure of the lessons, (iii) requirements for developing home-school resources, and (iv) advantages/disadvantages of remote PE delivery. The teacher schedule (10 questions) covered areas such as; (i) available resources for remote PE teaching, (ii) comparison of the provision of PE compared to other school subjects during home-schooling, and (iii) suggestions for changes to the existing content of the resource for future use. The schedule for parents/guardians (13 questions) centred around how the PE at Home lessons were used during the Covid-19 school closures; (i) parental knowledge of PE, (ii) comparison between home-schooling for PE compared to other subjects, and (iii) delivery of the PE lessons.

Snowball sampling was used to recruit further participants for interviews (Kirchher and Charles Citation2018). Initial participants those the research team were aware had engaged with the resource. Subsequently, these participants invited other PE at Home lesson users to contact the research team to volunteer as interview participants. All interviews were conducted using Zoom and according to Kite and Phongsavan (Citation2017) the quality of data collected through online communication platforms like Zoom is similar to that which is collected in face-to-face discussions. Seven lesson developers, five parents, and five teachers were interviewed for the study. All interviews lasted between 15 and 20 min, and with the consent of all participants, were digitally recorded for analysis. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into NVivo 12 Pro for analysis. This enabled a purposeful approach to thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) in order to systematise and increase the traceability and verification of the analysis (Nowell et al. Citation2017)

Data analysis

Quantitative data were exported into SPSS version 24. Descriptive statistics and response frequencies for all questions were calculated. Qualitative data analysis was initially undertaken through reading and re-reading the transcripts to become familiar with the content. This content was then assigned to codes or labels. The analysis was undertaken deductively, informed by the quantitative findings and the interview questions. The next phase of coding involved reviewing and collating all the data into groups identified by particular codes. Once the focused coding phase was complete, similar codes where patterns existed were combined, resulting in three themes. A sample of the coding process can be seen in . Finally, the themes were compared against the data set and each one named. The themes related primarily to lesson outcomes and how lessons were received by the users; (1) Ensuring the ‘E’ remained in PE, (2) home-schooling and PE (3) context and relatability. The involvement of the first two authors in the analysis process, and the triangulation of multiple data sources, resulted in a detailed and thorough process of examining all data that supported trustworthiness.

Table 1. Sample of theme development.

Results

Our inquiry into the PE at Home lessons as experienced by the teachers and parents of children in primary school generated three themes: ensuring the ‘E’ remained in PE; home-schooling and physical education; and context and relatability. As the purpose is to examine the PE at Home lessons which included 31 lessons (across games, gymnastics, athletics, dance and outdoor and adventure activities) from a parent, teacher, and developer perspective it is important to contextualise the level of engagement through quantitative data elicited from social media engagement with the PE at Home lessons nationally. Dublin City University Facebook viewing figures show that views for most of the PE at Home lessons were above 1000. Overall there were 27,000 views of the 23 lessons between the beginning of April and the end of June 2020. The Scoilnet website had 937 page views with 636 views of all the lessons. This number is encouraging given that lessons were not uploaded to the website until mid-June and the resources on the Scoilnet website were not advertised at this time.

Ensuring the ‘E’ remained in PE

A common theme throughout the process of developing, sharing and experiencing the PE at Home lesson series was ensuring that the lessons were educative and focused on teaching and learning. While the developers of the PE at Home resource were experienced PE teachers they experienced difficulty in ensuring that the lessons were educative, interactive and included questioning. The developers wanted to ensure that, ‘learning would occur, that learning would be central to what we were doing – that’s it’s fun, it's enjoyable, but that learning occurs’ (Dev 2). As well as learning skills they wanted the children to learn the importance of physical activity and this was highlighted throughout the lessons, with Developer 3 stating that ‘we wanted to include the importance of heart-related, cardio activities that would boost children’s cardio health as well, and encourage them to be physically active for their 60 minutes a day’. One developer stated that ‘individual feedback that teachers get to give to individual kids, … . you just can’t do it through this mode of learning’ (Dev2). They modelled questioning for the parents/guardians so that they could in turn provide learning opportunities for their children when undertaking the lessons but explained that this proved difficult, ‘I can’t pose a question live to the kids through the screen, you’re posing it to the child that’s in front of you and hoping that that comes to life for the other kids that are watching’ (Dev2).

The developers felt that it was easier for parents, teachers and even the children watching the lessons to engage with the educational aspect of the lessons through the interactivity of the teacher and child in the lesson.

I think for us that’s why it was important to have an adult and a child there, was that you could see that interaction and you could see the questioning and you could see the, what we were picking up, the teaching points, what we were looking for when the child was doing whatever the activity was. (Dev5)

Another parent liked that their children were learning skills through PE;

I sort of feel with it that at least at a subconscious level even if I don’t stand at the front of the garden and teach him like a taught lesson, I think he would be a bit more aware of, like with athletics explaining the way they were running and moving around, you know stuff like that, even if it just makes him a bit more aware. (Par2)

The learning environment was perceived by the developers as a context where they hoped that practicing on their own with only their parents or another family member might motivate the child to practice and improve with their encouragement. As one developer pointed out, ‘you have people that don’t really like doing PE in front of other people or being active or doing different games like maybe people have less than inhibitions to do it on their own time in their own houses’ (Dev3), while another stated ‘you can be … as bad as you want and nobody’s gonna say anything to you, you just get on with it and just enjoy activity for activity sake’ (Dev5). Not only can parents provide encouragement and feedback to their child but as parents were engaging with their child’s learning in and through movement they were role-models for their children.

what we do know is that, at primary school age parents are the biggest influencer of kids … they are the biggest factor that will influence whether kids go on to be active or not … like in terms of the child’s potential to go on and keep playing, and to keep being physically active as they age. Parents play a massive role in that. (Dev2)

Teachers felt that for some parents ‘these lessons are probably more relevant for the people in [disadvantaged] areas because it just gives them more ideas. It's educating them as to what's available to them on their doorstep, in their back garden’ (T4). They also noted how, during the period of home-schooling, some parents preferred doing PE rather than teaching other subjects.

there were many parents that would love to face into that a lot more than sitting down and doing an Irish … it was great because it meant that they were spending time with their children, they were doing something that was relevant … (T4)

Twenty-nine percent (29%) of parents indicated that their child made a ‘good’ or ‘great’ improvement in their physical skills after using the PE at Home lessons. However, the developers noted that PE should target the physical, cognitive and affective domains of learning and while the physical and cognitive domains were highlighted in the lessons, the affective domain particularly social interaction was lacking, with one developer saying ‘where it [PE at Home] does fall down is that the social interaction part which is really big in PE’ (Dev5).

Home-schooling and physical education

The developers saw how ‘challenging it was for the teachers to be able to come up with work that was doable for the parents … but also educational, and it was very clear that PE as a subject was the most challenging’ (Dev 2). The developers wanted children to ‘continue to learn and continue to develop their actual PE skills FMS but also the skills associated with the PE curricula’ (Dev 2). As there were very few PE resources available to teachers which could be recommended to parents or prescribed for PE, many teachers (84%) sourced physical activity online resources for their classes. The most frequently provided resource for PE was PE with Joe Wicks (50%), with Go Noodle (43%) and Cosmic Kids Yoga (33%) the next most frequently used resources. While physical activity is vital for children’s health the developers were aware that children’s learning was being neglected.

the teachers are being quite good at finding things but they’re not educational. It’s not PE and it’s not based on the curriculum like the maths, English, Irish … It’s more physical activity and general activity type things as what they’re providing. (Dev5)

I would just watch them and then I just try to more incorporate bits, rather than me being the PE teacher outside because they just don’t react to that, I just kind of like, if the balls were out, trying to do a few of the things we’ve seen. (Par2)

Some teachers and parents found that the prescribed lessons may have been too difficult for the children in an age group. This was particularly relevant for a teacher from a disadvantaged school who felt ‘there would be a huge deficit with gross and fine motor skills there. … So while you might have first or second class [Year 3 and 4], you could be teaching strands from juniors and seniors [year 1 and 2]’ (T4). Parent’s also saw the need for differentiated lessons or access to younger classes lessons;

like for my son, he’s nine but as I said, like he’s not really into GAA or, you know, not that sporty, so some of it was probably a little bit like, he’d get frustrated when he couldn’t do it … he might have needed a younger class level. (Par5)

Context and relatability

While creating the lessons during lockdown the developers were conscious that children might not have the gardens or space required in which to carry out the lessons.

I have a nice big garden with loads of room etc. And maybe that we deliver, or we design some of the lessons to be done in a room … or a hall or somewhere to reflect the realities where lots of the kids are actually living. (Dev4)

Parents commented on the fact that they were able to relate to the PE at Home lessons for many reasons. Being Irish resonated with many, ‘even hearing the Irish accent is nice to know that it’s … well you know it's a bit more real’ (Par3). This was someone their child could relate to and understand rather than an adult telling them what to do all the time.

What was better was, this was, in both sets of videos I saw, these were people who were the same age as my own son. And that made a huge amount of difference, because there was that identification with and connection to, it wasn’t somebody with a strange accent from a different country who’s the same age as their parents, it was somebody their own age who was doing something … And that was really important. (Par4)

All teachers who used the PE at Home lessons said that they would use the PE at Home lessons in the future. Sixty-three per cent (63%) of teachers stated that they would use the lessons if PE cannot be taught in schools due to Covid-19-related restrictions. Outside of Covid-19-related restrictions, 58% of respondents said they would use the PE at Home lessons for PE homework. In addition, two respondents stated that they would use the PE at Home lessons in the future to source ideas and prepare for their own teaching of PE, one of whom indicated the usefulness of the PE at Home suite as a preparatory tool as she found ‘the language/content to be useful to inform me as the class teacher before I teach a lesson’ (TS).

The most common addition proposed by teachers for the resource was the inclusion of a task card or ‘page’ to supplement the lesson; ‘I think would have been really useful to have a one pager with each of the lessons that goes, “here is activity one” to almost have like task cards (T2).’ Another teacher highlighted how this would be helpful to specific types of schools, ‘I do think they could probably reach out to DEIS [disadvantaged schools] in different, maybe in a PDF format’ (T4). The task card could also be used by teachers in schools. For parents/guardians, who said they would use the lessons in the future 53% said they would use them if their child/children cannot do PE in school due to Covid-19 restrictions, 41% said they would use them if their child was given the PE at Home lessons as homework, while 42% said they would use the PE at Home lessons as an activity independent of the school.

Discussion

The findings presented provide insights into the experiences of the developers, teachers and parents with the PE at Home lessons in the context of home-schooling during the initial Covid-19 pandemic school closures. The findings contribute to the knowledge of this particular phenomenon by making more explicit some of the conditions and experiences as promoting or inhibiting successful teaching and learning of PE while home-schooling. The first theme related to the purpose of the resource. Inhibitors suggest that parents and teachers placed a significant emphasis on the activity rather than the educational aspect of PE. This isn’t a novel finding – in fact, there is a growing, but we would suggest misguided, move towards physical activity as the dominant engagement for children. We would suggest misguided as there appears to be an over emphasis on solely being physically active rather than the learning and development of the child in terms of their ability and confidence to perform skills. This is not just reflected by parents but by teachers too as there can be an overemphasis on physical activity initiatives within the school context at the expense of PE. It is very common for schools to take part in these initiatives such as running a mile a day, active breaks for example and perhaps not in structured PE lessons.

These initiatives usually have the sole aim of increasing physical activity and overlook the holistic development of the child which occurs in PE alongside the development of physical literacy. Research (e.g. Giblin et al. Citation2014) highlights how structured instruction and feedback are required to ensure physical literacy is developed appropriately during childhood in order for children to become healthy and active adults. Perhaps the increased focus on physical activity and only being able to exercise within the government’s prescribed limitations contributed to this focus during the pandemic. It is important when creating resources for online/remote PE and also for in-school PE that there are clear learning intentions for the activities chosen. These learning intentions should target the physical, affective and cognitive development of the child where possible. The resources should also include elements of assessment such as questioning, clear instruction which is aligned with the learning intentions and aspects to focus on when providing feedback to the child. Including these elements in the resource will assist the teacher in targeting the learning involved in the activity rather than just focusing on being active.

Previous research on PE-related parental involvement has revealed several challenges, including underdeveloped partnerships between home and school (Svendby and Dowling Citation2013). On the other hand, successful collaboration has been characterised as open, ongoing, frequent and reciprocal communication between home and school (Chaapel et al. Citation2013). Through lockdown, online communication between schools and teachers, and parents become the mode through which children were taught and learned. For PE specifically however, the inclusion of parents/guardians in the teaching process may also have provided an unforeseen benefit. Parents of school-aged children and their attitudes and perspectives can be a key determinant in facilitating children’s adoption of PE and physical activity (Coulter, McGrane, and Woods Citation2020). Children are more likely to engage in physical activity if they adopt positive attitudes towards PE and parents play a large role in their development. That being said, while many studies indicated that parents are important socialising agents in the field of sports (Birchwood, Roberts, and Pollock Citation2008), Sheehy (Citation2006, 244) found ‘that parents knew remarkably little about their child’s PE program, and what they did know was often inaccurate’. PE at Home provided an opportunity for PE to be showcased for parents.

The context and relatability of the PE at Home lessons highlighted some of the benefits of online instruction such as increased access to content for children, ease of instructional delivery for teachers, and the standardisation of content across different classes (Wentling et al. Citation2000). In an online environment, children are able to work at their own pace, to accelerate through content that is easy for them, and to go slower as needed when the content is more difficult (Ransdell et al. Citation2008). The child was supported by a parent in many cases and therefore received continuous feedback, how we might support the child to engage, if not independently, then perhaps with less scaffolding might be considered should further lockdowns continue. Murphy and Ní Chróinín (Citation2011, 141) maintain that ‘a broad experience in a supportive environment gives children the best chance of being successful movers and a good chance of finding activities they enjoy and want to repeat’. The PE at Home lessons provided teachers and principals with an opportunity to share this knowledge with parents across the PE curriculum. The lessons also capitalised on the attraction of watching recordings on YouTube or Facebook that most children possess (Charlop-Christy, Le, and Freeman Citation2000).

Conclusion

We have offered new insights into the varied experiences regarding a PE-related home-school collaboration between teachers and parents of primary school children during a period of national lockdown utilising the PE at Home lessons. We fostered new beginnings and brought something uniquely new to the educational situation in the context of a pandemic where PE holds the potential to be a space that promotes and celebrates ‘different ways of being in the world as some-body’ (Quennerstedt Citation2019, 615–616). We conclude this paper suggesting that online video resources based on learning aligned with a country’s PE curriculum and encouraging regular physical activity could be a useful, and pragmatic, way forward. We have seen in this study that learning had become more child-led with practical activities centred around their interests, their home and community, and conducted at the child’s own pace.

Considerations for the future include: how the focus of parents and teachers can be shifted from the ‘P’ to the ‘E’ in schools and at home; and how parents can support their child’s teacher and their child’s learning in PE. For resource developers, it is important for future practice that the learning element of PE is highlighted clearly in resources such as PE at Home lessons to assist teachers/parents in ensuring that this learning occurs and children are not solely being physically active. The ‘take home message’ is that PE at Home addresses the teaching and learning of PE in multiple contexts (e.g. home and school), and can be used in multiple ways (e.g. improve learner–learner interaction or personalised learning) not only in Ireland but internationally. To date, the impact on children’s educational development due to the disruption caused by Covid-19-related school closures is unknown though the general consensus is that greater instructional time results in better learning outcomes (Rivkin and Schiman Citation2015).

This research adds to the current body of literature exploring the impact of the COVID-19 school closures internationally (Devitt et al. Citation2020). At the time of writing this paper, schools in Ireland were reopening for the first time in nearly six months. According to Cassidy and MacPhail (Citation2020, n.p.), ‘the realities of social distancing mean there is an inclination to move towards individualized learning activities in safe spaces’. The move to individualised activities affords teachers a greater opportunity to achieve consistent levels of individualised feedback, create more tasks that are appropriately enjoyable and challenging, and carry out an Immediate assessment of, and for, learning. The PE at Home lessons provide teachers with a resource to assist them with this undertaking.

Acknowledgements

We thank the parents, teachers and developers for their participation in this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bellini, S., and J. Akullian. 2007. “A Meta-Analysis of Video Modeling and Video Self-Modeling Interventions for Children and Adolescents with Autism Spectrum Disorders.” Exceptional Children 73: 264–287.

- Berge, Z. L., and T. C. Clark, eds. 2005. Virtual Schools: Planning for Success. New York, NY: Teachers’ College Press.

- Bernard, R. M., P. C. Abrami, Y. Lou, E. Borokhovski, A. Wade, L. Wozney, and B. Huang. 2004. “How Does Distance Education Compare with Classroom Instruction? A Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Literature.” Review of Educational Research 74 (3): 379–439.

- Birchwood, D., K. Roberts, and G. Pollock. 2008. “Explaining Differences in Sport Participation Rates among Young Adults: Evidence from the South Caucasus.” European Physical Education Review 14 (3): 283–298.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101.

- Britton, U., J. Issartel, J. Symonds, and S. Belton. 2020. “What Keeps Them Physically Active? Predicting Physical Activity, Motor Competence, Health-Related Fitness, and Perceived Competence in Irish Adolescents After the Transition from Primary to Second-Level School.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 3 (2): 2874.

- Cassidy, D., and A. MacPhail. 2020. Changing the ‘Message’ of School Physical Education in Response to COVID-19: Avoiding the ‘New Normal’. International Forum for Teacher Educator Development retrieved from https://info-ted.eu/author/ann_dean/.

- Cavanaugh, C., K. J. Gillan, J. Kromrey, M. Hess, and R. Blomeyer. 2004. The Effects of Distance Education on K-12 Student Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis. Learning Point Associates/North Central Regional Educational Laboratory (NCREL).

- Chaapel, H., L. Columna, R. Lytle, and J. Bailey. 2013. “Parental Expectations About Adapted Physical Education Services.” The Journal of Special Education 47 (3): 186–196.

- Charlop-Christy, M. H., L. Le, and K. A. Freeman. 2000. “A Comparison of Video Modeling with in Vivo Modeling for Teaching Children with Autism.” Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 30: 537–552.

- Choi, H. J., and S. D. Johnson. 2005. “The Effect of Context-Based Video Instruction on Learning and Motivation in Online Courses.” American Journal of Distance Education 19 (4): 215–227.

- Coulter, M., B. McGrane, and C. B. Woods. 2020. “PE Should be an Integral Part of Each School day: Parents’ and Their Children’s Attitudes Towards Primary Physical Education.” Education 3-13 48 (4): 429–445.

- Coulter, M., and C. B. Woods. 2011. “An Exploration of Children’s Perceptions and Enjoyment of School-Based Physical Activity and Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Activity and Health 8 (5): 645–654.

- Daum, D. N., and C. Buschner. 2012. “The Status of Secondary Online Physical Education in the United States.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 31: 86–100.

- Daum, D. N., and A. M. Woods. 2015. “Physical Education Teacher Educator’s Perceptions Toward and Understanding of K-12 Online Physical Education.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 34 (4): 716–724.

- Department of Education and Science. 1999. Primary School Curriculum: Physical Education. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Devitt, A., A. Bray, J. Banks, and E. Ní Chorcora. 2020. Teaching and Learning During School Closures: Lessons Learned. Irish Second-Level Teacher Perspective. Dublin: Trinity College Dublin.

- Giacobbi, P. R., A. Poczwardowski, and P. Hager. 2005. “A Pragmatic Research Philosophy for Sport and Exercise Psychology.” The Sport Psychologist 19 (1): 18–31.

- Giblin, S., D. Collins, A. MacNamara, and J. Kiely. 2014. “The Third way: Deliberate Preparation as an Evidence-Based Focus for Primary Physical Education.” Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich) 66: 385–395.

- Griggs, G., and K. Petrie. 2018. “Where to Go from Here.” In Routledge Handbook of Primary Physical Education, 1st ed., edited by G. Griggs and K. Petrie, 329–332. London: Routledge.

- Holfelder, B., and N. Schott. 2014. “Relationship of Fundamental Movement Skills and Physical Activity in Children and Adolescents: a Systematic Review.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 15: 382–391.

- Keegan, R. J., L. M. Barnett, D. A. Dudley, R. D. Telford, D. R. Lubans, A. S. Bryant, W. M. Roberts, et al. 2019. “Defining Physical Literacy for Application in Australia: A Modified Delphi Method.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 38 (2): 105–118.

- Killian, C. M., C. J. Kinder, and A. M. Woods. 2019. “Online and Blended Instruction in K–12 Physical Education: A Scoping Review.” Kinesiology Review 8: 110–129.

- Kirchher, J., and K. Charles. 2018. “Enhancing the Sample Diversity of Snowball Samples: Recommendations from a Research Project on Anti-dam Movements in Southeast Asia.” PLoS One 13: 8.

- Kite, J., and P. Phongsavan. 2017. “Insights for Conducting Real-Time Focus Groups Online Using a Web Conferencing Service.” F1000 Research 6: 122.

- Lubans, D. R., P. J. Morgan, D. P. Cliff, L. M. Barnett, and A. D. Okely. 2010. “Fundamental Movement Skills in Children and Adolescents: Review of Associated Health Benefits.” Sports Medicine 40: 1019–1035.

- Mechling, L. C. 2005. “The Effect of Instructor-Created Video Programs to Teach Students with Disabilities: A Literature Review.” Journal of Special Education Technology 20: 25–36.

- Mohnsen, B. 2012. “Implementing Online Physical Education.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 83 (2): 42–47.

- Murphy, F., and D. Ní Chróinín. 2011. “Playtime: The Needs of Very Young Learners in Physical Education and Sport.” In Sport Pedagogy: An Introduction for Teaching and Coaching, edited by K. Armour, 140–152. England: Pearson Education.

- Nowell, L. S., J. M. Norris, D. E. White, and N. J. Moules. 2017. “Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16 (1): 1609406917733847.

- Piek, J. P., L. Dawson, L. M. Smith, and N. Gasson. 2008. “The Role of Early Fine and Gross Motor Development on Later Motor and Cognitive Ability.” Human Movement Science 27: 668–681.

- Quennerstedt, M. 2019. “Physical Education and the Art of Teaching: Transformative Learning and Teaching in Physical Education and Sports Pedagogy.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (6): 611–623.

- Ransdell, L. B., K. Rice, C. Snelson, and J. Decola. 2008. “Online Health-Related Fitness Courses: A Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing or a Solution to Some Common Problems?” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 79 (1): 45–52.

- Rivkin, S. G., and J. C. Schiman. 2015. “Instruction Time, Classroom Quality, and Academic Achievement.” The Economic Journal 125 (588): F425–F448.

- Sheehy, D. 2006. “Parents’ Perceptions of Their Child’s 5th Grade Physical Education Program.” Physical Educator 63: 30–37.

- Svendby, E. B., and F. Dowling. 2013. “Negotiating the Discursive Spaces of Inclusive Education: Narratives of Experience from Contemporary Physical Education.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 15 (4): 361–378.

- Van Acker, R. Van, I. De Bourdeaudhuij, L. Haerens, K. De Cocker, G. Cardon, K. De Martelaer, J. Seghers, and D. Kirk. 2011. “A Framework for Physical Activity Programs Within School–Community Partnerships.” Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich) 63 (3): 300–320.

- Wentling, T., C. Waight, J. Gallaher, J. La Fleur, C. Wang, and A. Kanfer. 2000. E-learning: A Review of Literature. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois National Center for Supercomputing Applications.