ABSTRACT

Background

This paper reports on the gendered embodiment of physical education (PE) pre-service teachers, as they learnt to teach gymnastics using mobile website technology.

Methodology

Framed within an interpretivist paradigm and informed by a constructivist grounded theory, qualitative data from module observations, focus groups and semi-structured interviews were analysed as part of an iterative process. The participants included PSTs from two secondary physical education teacher education (PETE) cohorts and a teacher educator (TE, female) in a single higher education institution. Author one designed the mobile website and at times took on the role of TE within the study. Bourdieu’s central tenets of habitus, field and capital were employed as part of the conceptualisation of the following categories: (1) The gendered body in gymnastics (2) The dominance of masculine characteristics; and (3) Gender and competition.

Results

Analysis of data revealed that male and female PSTs’ pedagogical engagement with the mobile website in gymnastics reflects stereotypical notions of gender. The dominance of masculinity worked to privilege those bodies that possessed the necessary attributes and often emancipated males in what historically has been considered a female activity.

Conclusions

This study recognised the role of the gendered habitus in constructing normalised bodily movements for both male and female PSTs in a PETE gymnastics context. However, it is recommended that PETE teaching pedagogies be explicitly deconstructed to offer more nuanced gendered practices that challenge the gender order, offering equity for the more marginalised PE bodies.

Introduction

Physical education (PE) is a context in which gendered practices and heteronormativity are constituted (Brown Citation2005; Devis-Devis et al. Citation2018). It is also a significant space for stereotyping (Larsson, Quennerstedt, and Ohman Citation2013), due to rules and rituals which are almost always inherently gendered (Brown Citation2005; Tinning Citation2010). Several studies have focused specifically on the implications of gender differences regarding the dominance of masculinity and the physical outcomes in PE programmes (see Azzarito and Solomon Citation2005; Gorely, Holroyd, and Kirk Citation2003; Joy and Larsson Citation2019; Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2009; Oliver and Kirk Citation2016). Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius (Citation2009) identified that the dominance of masculinity in the gymnasium was normalised and did not restrict success in physical activity. Consequently, it was not challenged but instead was managed through teaching methods. In a later study, Oliver and Kirk (Citation2016) sought to improve the PE landscape for girls, by proposing an activist approach, which would offer girls an understanding of the dominance of masculinity. More recently, Joy and Larsson (Citation2019) explored the different bodily movements that constituted masculinities for boys in PE.

Despite the plethora of research that aims to understand and or challenge the dominance of masculinities in PE, gendered inequity for both boys and girls still exists (Scraton Citation2018; Garrett and Wrench Citation2019). For example, Scraton (Citation2018) in her historic review highlights the continued disengagement of girls in PE, and Garrett and Wrench (Citation2019) recently focused on redesigning the more traditional didactic pedagogies in dance to improve boys’ engagement. This was conducted using practitioner action research and as a process of action on reflection. PE (and sport) are therefore contexts for which gender can influence or damage young peoples’ experiences of physical activity (Wright and Laverty Citation2010). As a consequence, future research needs to focus on pedagogical practices that challenge gender norms by encouraging boys and girls to behave in a variety of ways (Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2009, Citation2014).

In this study, we did not aim to challenge gender norms, but we did analyse the different ways that pre-service teachers’ (PSTs) embodied gender, when engaging with gymnastics pedagogies. The justification for choosing gymnastics was grounded in the aims of a much larger research project, that sought to develop the pedagogical practices of physical education teacher education (PETE) students in gymnastics using a mobile website. In understanding how certain forms of gender are affected by and affect PSTs’ engagement with pedagogical practices (Garrett and Wrench Citation2019; Landi Citation2017; Joy and Larsson Citation2019), we can prepare a generation of teachers that are equipped to deliver PE (and more specifically gymnastics) in an ever-changing, diverse context and increasing fluidity in how gender is seen. The next section provides a potted historical construction of teaching pedagogies in gymnastics and the subsequent dominance of masculinity in PE, which in part frames the foundation of the current context and associated gender discourses.

Pedagogies for teaching gymnastics

Pedagogical practices in gymnastics can be traced back to the 1950s and the dichotomy between the movement approach and the skills-based approach. Female teachers had quickly adopted Rudolf Laban’s exploratory work in gymnastics, which was underpinned by movement patterns that focused upon weight, space, time and flow (Bailey Citation2010). This meant that girls were involved in the decision-making, with the focus on expression, beauty and innovation rather than the skill. As females were more prevalent in teaching than their male counterparts, this period of PE history was referred to as the ‘female discourse’ (Kirk Citation1992). Societal changes led to a rise in the school leaving age and subsequently secondary schooling began to focus on specific curricular subjects. Dominant discourses in PE were influenced by subject specialists and consequently, aesthetic activities characterised girls PE and physical prowess characterised PE for boys (Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2009). However, with universities valuing scientific knowledge and males increasingly dominating the PE space, a ‘skill-focused approach’ in PE was gradually advocated (Griggs and McGregor Citation2012, 226). This saw the demise of creativity for a more technical performance-based curriculum, with male discourses around physical strength, superseding the female aesthetic discourses (Haerens et al. Citation2011). This has continued with the social constructions of masculinity sharing many of the characteristics of the male discourse and continue to be reflected in existing PE practices associated with interpretations of policy regarding the current National Curriculum PE in England (NCPE Citation2013), which reproduce traditional methods of teaching (Philpot Citation2016). According to Kirk (Citation2010, 41) a ‘physical education-as-sport-techniques’ model, prioritises the execution of isolated skills, pupil performance, and which often reward the physical body (Connell Citation2005). In activities like gymnastics, this can mean that the objective body takes precedence over subjectivities associated with the expression of bodies. According to Griggs and McGregor (Citation2012) the product is more important than the process and consequently creativity in gymnastics is diminished. Within PE, pupils who meet these physical expectations are valued highly by teachers (lisahunter, Smith, and emerald Citation2015), as schools are assessed on measurable outcomes driven by performative practices (Evans Citation2014). It is no wonder therefore that masculinity continues to be reinforced and subsequently dominates how PE is experienced by those ‘in it’ (see Flintoff Citation1993; Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2009).

Set within these gender discourses, this paper uses Bourdieu to understand how male and female PE PSTs embodied gender through engagement with pedagogical practices in PETE gymnastics. Before beginning to understand this, we explore the usefulness of Bourdieu’s concepts of practice, habitus, capital and field.

Theoretical framing for analysis

For Bourdieu (Citation1980/1990) the concept of practice refers to the taken-for-granted daily activities that should be the foundation of all social analysis because it reveals the logic surrounding the actions of individuals (lisahunter, Smith, and emerald Citation2015). Practices are grounded in the complex interrelations between habitus, capital and field; therefore, it is through PSTs’ practices that we can uncover how they affirm their position in PETE gymnastics. Habitus is the basis of these practices and has been described as the embodied social history of an individual (Light and Kirk Citation2000). Through our lived experiences we internalise social structures, subsequently developing perceptions of the social world, for instance, what a desirable gymnastic body should look like and be able to do (lisahunter, Smith, and emerald Citation2015). Whilst life histories are unique, individuals who are exposed to similar social fields, such as girls’ PE, often develop similar habitus (Light and Kirk Citation2000). However, whilst one’s habitus is influential in shaping behaviours in different situations, such as the way we sit and walk, it may not be the defining factor. In fact, it is more the interrelationship between habitus and field. Field can be defined as the total occupiable social positions at any one time and place (e.g. university, religion, peer groups; see Grenfell Citation2014). Although field is fluid (Bourdieu Citation1993), it is bound by objective structures (e.g. the rules, positions, interests and values), which can be represented within the practices of the individuals or groups that make up the field (lisahunter, Smith, and emerald Citation2015). Capital is accumulated by individuals and functions in relation to what is valued in the field, particularly by those who sanction the rules of the field (e.g. PE teachers). Those individuals who accumulate the necessary capital (e.g. physicalness) subsequently tend to take up positions that dominate the field. This can lead to ‘gendered inequalities’ as people and groups in the field struggle for power (lisahunter, Smith, and emerald Citation2015). In the next section, we discuss constructions of gender, before justifying the use of Bourdieu’s conceptual tools in the analysis of the data in this paper.

Gendered constructions in PE

From a social perspective, constructions of gender are located historically, culturally and socially (McNay Citation2000). Gender is not solely reducible to socialisation nor to biological dispositions but instead is a complex social construction of masculine and feminine ideologies (Connell Citation1987). These gendered constructions inform daily practices and are influential in means of knowing, and in appropriate ways of behaving and moving (Gorely, Holroyd, and Kirk Citation2003; Schippers Citation2007).

Connell’s (Citation1987) ‘gender order’ provides us with expected behaviours for both males and females. For example, masculinity in PE seems to be regarded as doxa, something normal (e.g. physical strength, courage and a passion for ball games; see Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2014). Contrastingly, femininity represents a subordination to masculinity (e.g. a preference to dance). Gendered binaries have however, been criticised for failing to recognise alternatives of what it is to be male or female (Connell Citation2008). Subsequently, there has been an increase in focus on gender as a fluid process (Joy and Larsson Citation2019), with gendered bodies contingent to the time, place and the discourses of the field (Connell Citation2008; Schippers Citation2007). Yet, the dominance of masculine and feminine ideologies engrained in culture, has meant that gender is often reduced to stereotypical behaviours that replicate patriarchal structures of society, mirroring one’s biological sex (Metcalfe Citation2018). Connell (Citation2008) argues that whilst multiple patterns of masculinity exist, the problem is that not all versions are equally respected. For example, hegemonic masculinity is a dominant form of masculinity (Connell Citation1995; Whitson Citation1994), which is honoured and most often privileges men. Discourses like this become powerful when normalised into ways of thinking, (i.e. males feel pressured to behave in certain ways). Butler (Citation1993) referred to this as gender performativity. This is when the voluntary actions of a person, which have been structured by society, are necessary for the individual to be perceived as normal. The taken-for-granted assumptions, or doxa, often result in symbolic violence, a term used to express the effects of doxa (Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2014). Symbolic violence, which is invisible to individuals (Bourdieu Citation2001), is symbiotic rather than physical when exercised in ways that restrict their opportunities (Webb, Schirato, and Danaher Citation2002; McNay Citation2004). In this sense, dominant forms of masculinity become embodied and according to Bourdieu (Citation1984) are key to the reproduction of social inequalities. For most PSTs in this study, the gendered habitus reflects stereotypical notions of gender, with males constructing and reproducing hegemonic forms of masculinity. So, for the purpose of this paper, ‘gender’ will refer to the social construction of norms associated with masculinity and femininity.

Although most of Bourdieu’s work has focused on the embodied form of cultural capital (e.g. mind and body), he has been critiqued for focusing less attention to gender (Gorely, Holroyd, and Kirk Citation2003; lisahunter, Smith, and emerald Citation2015). However, given that habitus and the physical body are symbiotic, and gender is embedded in the habitus through bodily practices (Paradis Citation2015), Bourdieu’s work has the potential to provide a powerful means of using habitus to analyse the relationship between both the physical and social body (Brown Citation2005). This is of particular interest to those in the PE field, as the visible body is highlighted on a larger scale than in any other area of the curriculum (Velija and Kumar Citation2009). For this reason, other research projects have explored gender constructions in PE using the work of Pierre Bourdieu. Brown (Citation2005), for example, used Bourdieu to conceptualise gender relations in PE and found that through continual practices the gendered habitus was reinforced in ways that met the demands of the field. Light and Kirk (Citation2000) drew upon masculinities in high school rugby; Sparkes, Partington, and Brown (Citation2007) used the concepts to uncover jock body and culture, and Metcalfe (Citation2018) has used the concepts to focus on the role of PE in the construction of gendered identities. These examples illustrate the power of using Bourdieu in analysing constructions of masculinity in varied PE contexts. Like Metcalfe (Citation2018), this research examines both male and female constructions of gender concurrently, doing so through PSTs’ pedagogical engagement and reflection on PETE. The next section outlines the methodological location of the study and subsequent nature of the data analysis associated with it.

Methodology

Informed by a constructivist grounded theory methodology (Corbin and Strauss Citation2008; Charmaz Citation2017), relevant data were collected and analysed as part of an iterative process of concurrent data collection and analysis (Tracy Citation2010). At the centre of this was constant comparison, as well as the researcher’s theoretical sensitivity which involved the careful observation of the research subjects, as well as a critical reflection on themselves. The progressive coding and categorisation of the data involved the systematic breaking down of the data to support the conceptual rendering of that data. The iterative process associated with grounded theory offered the opportunity to use Pierre Bourdieu’s work to inform the analysis. In accepting that Bourdieu’s concepts of practice and habitus are mutually constituted, these conceptual tools offer us a powerful means of understanding how important the engagement in contextual pedagogical practices, like PETE gymnastics, can be in constructing gender for PSTs.

Participants and setting

This research informing this paper was conducted between September 2013 and April 2015, using two one-year PETE cohorts in a single University in the North West of England. The currency of the data remains relevant to the National Curriculum in English schools, the technological evolution and development of mobile technology in PE and the ongoing critique of curricular development in PETE. The mobile website was unique at the time of data collection, the NCPE remains unchanged, and it illustrates a process of curriculum innovation with principles of continuing relevance.

The research was approved by the University Research Ethics Committee prior to any data being gathered. British Educational Research Association (BERA Citation2011) guidelines were used to support the conduct of ethical research. Confidentiality was maintained as PSTs and the TE were made aware that all information, conversations and transcripts would be kept in the strictest of confidence, and of their rights to withdraw from part or all of the study.

Forty-seven PE PSTs, ranging between 22 and 37 years old; predominantly White British, were purposefully sampled (Patton Citation2002) on the basis of their enrolment on the PETE course. Through a written participant information sheet and verbal briefing, participants considered their involvement in the study and were invited to ask questions and return consent forms in their own time. The teacher educator (TE), a female with extensive experience of teaching PE in primary and secondary schools, and liaising between both to support PE provision, was employed at the University to teach practical PE, including gymnastics and games on the secondary PETE programme. Author one (female; and mobile website designer), with substantial experience teaching PE in both secondary and higher education contexts, additionally adopted a TE role as part of this process (e.g. team-teaching, solo teaching and answering PST questions).

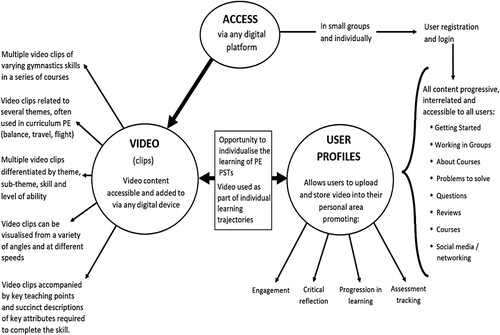

As part of their PETE training, the PSTs took part in a 10-week gymnastics core module, which happened to be the first module in advance of any of their teaching placements in schools. Each practical lesson each week was scheduled to last for two hours and the scheme of work, designed by the TE, consisted of both floor and apparatus work, covering themes such as balance, travel and flight; core elements that are often taught in schools as part of the gymnastics curriculum (Benn, Benn, and Maude Citation2007). The mobile website resource (teachgymnastics.co.uk), which was designed and created by author one as part of the larger research project on the gymnastics module consisted of a number of interrelated features as illustrated in .

To support the development of PSTs’ pedagogical content knowledge in gymnastics the mobile website was developed using a variety of pedagogical approaches that were teacher and student regulated. Author one encouraged PSTs to use the mobile website autonomously (i.e. independent access and use of content). However, the TE did not feel comfortable in offering the PSTs’ autonomy. Instead, she preferred a more didactic (i.e. instructive) approach to teaching, and so it was agreed that the use of the mobile website would reflect personal teaching pedagogies. This meant taking turns on who took the lead on activities. In doing this, all PETE students experienced the mobile website from different pedagogical perspectives.

Data collection

Data were collected by observing two cohorts of PETE students across 12 PETE gymnastics lessons using an unstructured approach (Byrman Citation2012). These visual methodologies proved to be a good way of capturing behaviour, as the movement of the body, the interactions and the body and the language interchanged during and between activities highlighted gender difference (Joy and Larsson Citation2019). Author one wrote a reflexive diary to capture this data, the purpose of which was later shared with PSTs. However, translating these notes proved challenging given the movement between participant and observer. With this, author one became reliant on mental notes, which were immediately documented and dated, post-lesson observation.

Six focus group interviews were conducted involving 16 PSTs, lasting between 60 and 80 min. The purpose of the focus group interviews was to allow for multiple viewpoints to be expressed, by encouraging dialogue on issues associated with PETE students’ pedagogical practices using the mobile website (Byrman Citation2012; Denzin and Lincoln Citation2011; Gibbs Citation2017). PSTs were randomly sampled from the PETE course list, ensuring that there was an equal representation of both sexes. This decision was pragmatic and replicated the mixed-sex teaching context. The timing of, and the topics to discuss in the focus groups continued to be constructed through the constant data collection and analysis (Gibbs Citation2017), for instance, when new ideas required development or when additional group voices needed to be heard. Four of the participants had a follow-up interview (lasting between 40 and 80 min, with 1 PST having three interviews in total). The sampling of PSTs for interview was based upon their delivery of gymnastics on school placement, giving us the opportunity to delve deeper into mobile website use in a genuine teaching context. The choice to interview the TE was informed through the constant analysis of data. The use of semi-structured interviews was deemed most appropriate in this study, as it allowed the strategically sampled PSTs and the TE to be invited to explore and discuss their experiences using questions framed by the ongoing data analysis. All interviews were transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Data were analysed in NVivo software using a process of open and axial coding (Corbin and Strauss Citation2008). Open coding, involved taking words, lines and phrases from the data and exploring all possibilities before assigning the data with a label or a broad concept, such as elegance (Charmaz Citation2006). More focussed coding meant that these concepts were scrutinised by comparing them to other concepts, prior literature and experiences, in order to establish relationships and make sense of things (Corbin and Strauss Citation2008). Finally, axial coding involved devising maps of concepts and through the concurrent analysis of data, the development of a hierarchy of sub-categories and categories were identified and not forced (Charmaz Citation2006). Subsequently, gender evolved into a category and encompassed three co-constructed sub-categories. (1) The gendered body in gymnastics; (2) The dominance of masculine characteristics; and (3) Gender and competition. Each subcategory was made up of several interrelated concepts (e.g. elegance, creativity, strength, risk taking).

Ethics

Whilst ethics must be considered in full prior to any research project, Dennis (Citation2009) encourages ongoing reflexivity as a means of reviewing the ethical deliberations of the field. The opportunity to take on several roles in the research gave author one an ‘in’; an insider position that exposed ethical dilemmas associated with power relations. It was impossible not to interact with the PSTs and the TE, as these interactions were embedded into the research design. Accordingly, these relationships needed to be considered to protect the participants but also to reflect upon the impact of those relationships on the research findings (Dennis Citation2009). The relationships with PSTs were additionally considered in relation to author one’s role. Author one had established some relationships with PSTs on the undergraduate degree and through previous employment as a PE teacher. The varying roles, e.g. designer of the mobile website and acting as TE, put her in a position of power. Author one was therefore conscious that these PSTs may try to please her with their comments during interviews, given that the mobile website was her design. Thus, prior to interviews, it was reinforced to the PSTs that the research was not to evaluate the mobile website as an isolated resource but to consider its pedagogical use amidst their PETE landscape.

In the next section, we describe and reflect on PSTs’ pedagogical engagement with the mobile website and key aspects associated with the gendered body, the dominance of masculine characteristics, and gender and competition.

Findings and discussion

The gendered body in gymnastics

From observation and interview data, most female PSTs felt that both competence and elegance (i.e. to be graceful/stylish) were expected of them when performing in gymnastics. Contrastingly, most males expressed feelings of unease when being asked to move in ways that they perceived to be feminine.

Autonomous use of the mobile website gave PSTs the opportunity to explore a theme (e.g. balance) in small groups and subsequently plan, discuss and practice their own learning activities associated with the chosen skills. Observations noted that such autonomy meant that elegance was not a priority for any of the male PSTs. Instead, the males embodied a masculine identity associated with physical characteristics (e.g. strength) and their own style of movement (e.g. a rigid body). The female PSTs also worked autonomously, however, most females arguably engendered capital in a different way (e.g. elegance rather than strength). For example, Sally said that when selecting skills from the mobile website, she would just: ‘ … try and just change it a little bit … like take an arm away or something; just to make it look a little better’ (Focus group 2). In contrast, the male PSTs tended to focus on the level of skill rather than the construction of movement or technique. Jack said: ‘We didn’t ever really think about how … ’ (Focus group 2).

On occasion, and perhaps because of her traditional understandings of gymnastics, the TE would restrict the PSTs’ autonomy, as she wanted them to focus on perfecting a specific skill. The TE would ask the PSTs to find the split leap on the website, practice it and go through each of the teaching points (Observation 7). When the PSTs practiced jumping and leaping skills, specified by the TE, the researcher on several occasions observed that male PSTs did so sarcastically by joking and mimicking each other. This is illustrated below in the following diary entry:

Students were asked to demonstrate leaping in and around the mats as part of their warm-up. It was apparent that the girls are more than happy to explore this concept. The males, although engaging in the activity, are doing so sarcastically. (Observation 7)

For some of the male PSTs, even the idea of sarcastically moving their bodies in the same ways as the females was unthinkable. For example, the researcher observed that when leaping, ‘the males exaggerated the pointing of toes and lifting of the head with a grin on their face’ (Observation 1). She also noted in her research diary the comments from one male PST, after he was asked to give constructive feedback on a female PST’s demonstration of a leap into a roll. Demonstrations were used to reinforce notions of body tension with no explicit strategy to privilege the use of males or females. Kev said: ‘No lad in the right mind would move his body like that’ (Observation 1). Such comments had implications for some female PSTs who could not perform with elegance. For example, Kelly said: ‘It’s difficult to try new things sometimes, as like all the males expect that you can do it elegantly and when you can’t you feel stupid’ (Kelly, interview 1).

Continuing with the didactic use of the mobile website, the TE set up vaults in rows, with PSTs forming queues that by their own accord came to be segregated by gender. All PSTs had access to the mobile website and on this occasion were directed to the handspring vault. Apart from Sarah (a former gymnast), this worked to disadvantage most female PSTs who were reluctant to get involved and, in some cases refused to participate altogether. Dillon said: ‘I think particularly when the trampettes came out and we were doing the vaulting, some of the girls couldn’t do it, so they would just go and sit there’ (Focus group 6). Lining up before the vault only drew attention to these apprehensions, as most female PSTs felt that they were being watched and critiqued by their male peers. Kelly said:

I’d say I’m quite low ability when it comes to gymnastics, the idea of lining up and having a big long line down one end, who are possibly going to see you vault, big long line that end. If you don’t feel confident and you have got lads doing somersaults, you don’t want to go and have a go. I think a lot of it comes down to confidence. (Kelly, focus group 6)

Contrastingly, most male PSTs seemed less uncomfortable about their failing body as they attempted complex vaults. For example, Dillon said:

I remember when Adam ran and jumped over the vault and went flat on his face, but the lads just laugh about it; he will get up and go, I’ll do it better next time. Whereas if one of the girls messes up slightly, it discourages all of them. Whereas with lads you are not laughing at them, well you are, but you are laughing with them. Maybe girls see it as ‘oh my god’ they are all laughing at me, it is embarrassing. (Focus group 6)

The ways in which male and female PSTs had constructed gymnastics bodies and the movement, competence and appearance of those bodies, were arguably indicative of their gendered habitus. Indeed, the researcher’s subjectivity around bodies in gymnastics had arguably been influenced by her own socialisation. For male PSTs, expression and elegance did not appear important. In fact, when the males engaged with an autonomous pedagogy using the mobile website, it offered them multiple interpretations of the content, yet they used these opportunities to move their bodies in ways that reflect masculinities (Velija and Kumar Citation2009). When the TE dictated content (e.g. leaping movements), most males used sarcasm to demonstrate a resistance to what they perceived as feminine movements. According to Garrett and Wrench (Citation2019), their bodies were vehicles that performed gender. In contrast, and to maintain their social status, the females used the autonomous pedagogy to make things look nice. They engendered capital in the form of elegance. Flintoff and Scraton (Citation2006) agree, stating that: ‘Girls in PE learn an acceptable form of femininity, control, precision, things looking nice, whereas boys are encouraged to develop a masculinity that is aggressive, dominant and physically strong and assertive’ (769). These conditioned and accepted behaviours were regarded as doxa, and although arguably non-conscious, were used by PSTs to judge themselves in gymnastics (Garrett Citation2004). In this sense, the gendered habitus, which associates femininity with elegance was reinforced. Consequently, failing to meet these expectations caused anxieties and humiliation (Flintoff and Scraton Citation2006) for those females who did not believe they ‘fit the bill’ of the ‘consummate’ female (i.e. what they perceived to be the perfect female). In PE, bodies are on show and arguably at their most vulnerable (Scraton Citation2018) and it is through this exposure, that females feel that their bodies are subjected to the comment, gaze and criticism of other males and females (Garrett Citation2004).

The majority of male and female PSTs conformed to gendered stereotyping as they sought to accrue capital through their bodily movements. However, it is important to recognise that some PSTs were aware of the gender norms, as they openly discussed them in interview. Thus, gendered behaviours may be conscious (PSTs aware of the norms), yet the norms are often reproduced in practice at a non-conscious level making any potential change to the gendered habitus problematic (lisahunter, Smith, and emerald Citation2015). We turn now to the physical characteristics that came to dominate the field of PETE gymnastics, before analysing the impact on both male and female PSTs.

The dominance of masculine characteristics

Most of the male PSTs embodied physical strengths, whereas most female PSTs were more concerned with elegance. However, the consensus was that PSTs valued the importance of masculine characteristics (Bourdieu Citation2001; Connell Citation2005), such as physical strength, power and courage when taking part in gymnastics. An example lesson involved the PSTs navigating through a variety of ‘partner balances’ on the mobile website, specifically ‘whole weight balances’ where one person had to take all their partner’s weight off the floor (Observation 2 and 6). The mobile website differentiated the balances regarding complexity, starting with basic supports to more complex lifting techniques. The focus of the task was body weight management, control and stability, leading to discussions around the biomechanics of movement. As the lesson progressed, all PSTs used the mobile website autonomously by accessing the videos at their own pace and level, whilst discussing their movement repertories with their peers. The data revealed that most males, having chosen to pair up with other male PSTs, began to use their own physical strengths to their advantage, thriving on the physicality of the task when lifting their own and their partner’s body weight.

From the researcher’s observations, most of the males would immediately access the advanced partner balances from the mobile website, with one PST, Jack, searching for a balance that explicitly showcased his bravery. In her research diary she wrote: ‘the bigger the move, the better’ (Observation 2). This was reinforced in the following quotation, when Luke described his movement choices as: ‘dangerous, I think. It looks like somebody could really hurt themselves’ (Focus group 2). The risk taken by males was reinforced through further observation: ‘the lads climbed on each other’s shoulders, trying to create the tallest pyramid’ (Observation 6). The TE also agreed when she said that: ‘Typically, the males went straight to the advanced skills’ (Interview 1). If the balances were too difficult, most of the males would begin to regress (e.g. begin with the most difficult skill, before moving down to the beginner level skills). This was reinforced by Jack who said: ‘Then we realised we couldn’t do that, so we tried intermediate and then we realised we couldn’t do that, so we went to beginners’ (Focus group 2).

Consequently, the TE became increasingly concerned for the male PSTs’ safety when using the mobile website. In an interview, she said: ‘ … … ’ I think once they start to bring on more advanced skills, the potential to fall, trip and injure themselves becomes greater’ (TE, interview 1). For the TE, this restricted the potential for males to work autonomously: ‘I think it’s got to have some direction and I think if it’s just out there, off you go, I think that’s when you could potentially get problems’ (Interview, 1). These concerns were shared by a female PST who was delivering gymnastics on school placement. She describes her use of the mobile website:

I had a lower set of year eight boys on vaulting, they had never done it before, so a lot of it was … command style because they have got a lot of potential to hurt themselves, and I know they have no fear. They were going to throw themselves around. (Ella, focus group 6)

We can’t hold each other like the lads can. (Shauna, observation 2)

She’s dead light but having to hold her for so many seconds for the balance and then moving to a different position, it’s a lot harder. (Sophie, focus group 2)

Additionally, the researcher observed these difficulties in the PETE gymnastics practical, with most female PSTs making minimal attempts to lift their partner’s body weight. She wrote that the female PSTs were:

attempting to lift their partner’s body weight with little success and collapsing in heaps of laughter. (Observation 6)

The TE reinforced this in her interview, as she described and compared both male and females in relation to these masculine attributes (e.g. risk, courage and fear). She said:

I think the males are more daring. More prepared to have a go. Whereas some of the ladies are kind of mmm, no, that’s not for me and I don’t want to try it. I fully appreciate that. Going upside down and a headstand and somebody taking your bodyweight. There are challenges there, aren’t there? Personal challenges. But I think the guys really got stuck in. Some of them. And were prepared to really stretch themselves, particularly on the vaulting. Just mad. (TE, interview 1)

As seen in the above examples, and as Bourdieu (Citation2001), Brown (Citation2005) and Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius (Citation2009) point out, it is typically masculinity that becomes the valued form of physical capital in PE; power is derived from the movements of the visible body, for instance, strength when climbing on shoulders (see Bourdieu Citation2001). These energetic movements, as expressed by most of the males, have been historically accepted ways of moving for males in PE and sport (Hickey Citation2008; Joy and Larsson Citation2019). Consequently, the dominance of masculine attributes, (which are almost always inherently related to the male body; Bourdieu Citation2001; Connell Citation2005) in this study, revealed an emancipatory position for most male PSTs and any females that possessed these masculine attributes. For example, author one did observe that Sarah (former gymnast) was able to perform the vault and in most cases executed it with more power than most of the male PSTs. Arguably, this was attributed to her gymnastics experience, which had worked to develop her strength, physical and mental toughness, which she consequently showcased through her confidence to practice and demonstrate in front of her peers. However, most of the female PSTs in this study, and as Brown (Citation2005) highlights, opted out of using their body to take risk when the skills required force. According to Whitson (Citation1994), when force requirements in PE outweigh skill (e.g. those with physical body strength excel), the hegemonic masculinity discourse is reinforced. Those PSTs, who appeared to resist dominant conceptions of masculinity, through a lack of risk taking, were observed to be left with feelings of anxiety, as the non-hegemonic masculinities of the body became marginalised (see Bourdieu Citation2001; Brown Citation2005 and Green Citation2008). These (often) non-conscious decisions, indictive of one’s habitus worked to reinforce the dominant ideologies and discourses about how males and females use and experience the body in PE (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation2001). Next, we explore how the domination of masculine characteristics were exuberated through competition. Male PSTs thrived on competition, whilst female PSTs rarely created competitive situations.

Gender and competition

Using the mobile website autonomously created a competitive ambiance for most male PSTs in this study. This was illustrated in the males’ views towards competition when using the mobile website:

We just wanted to be the best. (Sean, focus group 2)

… we were just trying to do the most elaborate. (Jack, focus group 2)

One male PST, when interviewed said:

For me in boys PE, I think there will always be, no matter what they are doing, there will be an element of competition … . Whereas with gymnastics, dance and aerobics, they will find a way of making it competitive. (Dillon, focus group 6)

Consequently, Dillon ensured that when teaching an all-male gymnastics class at his placement school, he used competition as a way of encouraging most of the males to move. The competition was always around the masculine characteristics such as physical strength. He said:

Who has got the best core strength? And they would try something out. Or who has got the best strength in shoulders, and they would try a handstand or something like that. That was the way I got away from the whole oh it is a girl’s sport, whereas the girls obviously I don’t think they would react as much to that. (Dillon, focus group 6)

Transferring this back to PETE, contrastingly, most of the females in this study did not engage in competition and although some female PSTs were arguably disadvantaged by competition (e.g. the researcher observed that at times the females sat back and observed the males in action; Observation 9), in interview the females never referred to feelings of subordination (i.e. inferior to the males; see Larsson, Quennerstedt, and Ohman Citation2013; Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2009). This was highlighted in Sophie’s reflections of competition, after using the mobile website in gymnastics. She said:

I don’t think I ever felt competitive. (Focus group 2)

One PST, Ella, put competition down to the difference in male and female attitude, when she said:

I think with the boys, if the boys can’t do something boys have a more aspiring attitude to go and make it better, whereas some of the girls are a bit like well I can’t do it. (Ella, focus group 6)

In line with research by Garrett (Citation2004) and Green (Citation2008) the data revealed that whilst females in most cases did not engage in competition, the lack of competition was not problematic if the female PSTs did not feel the need to be competitive in the field (Larsson, Quennerstedt, and Ohman Citation2013). Alternatively, the lack of competition from the female PSTs could have been down to a conscious choice not to take up that position in the field, for fear of failure. For example, in the vaulting lesson, Kelly expressed the embarrassment she would feel if she was to fall off the vault in front of her male peers, ‘For me, as an example, if I was self-conscious about the fact I couldn’t vault, and I had to vault and messed up on the vault, I would not feel too happy’ (Kelly, focus group 6).

Whilst the autonomous learning environment did not provide opportunities for structured competition, the data revealed that most male PSTs thrived on creating their own competitive situations against their peers. Thus, it could be argued that in an autonomous PE environment, where outcomes are more individualised, symbolic violence could have restricted the majority of female PSTs engagement with the more competitive elements of the field. The females, in most cases were not willing to put their ‘failing’ female body on display, similarly, making success a male characteristic. The ‘dominated’ tended to conform to established practices by opting out of competition and becoming defined by the structure. The ‘dominating’ use the structures to epitomise their power (Shilling Citation2004; e.g. the male PSTs use the autonomy to capitalise on their physical abilities through competitiveness). Here, the movements and behaviours of both male and females have engrained ‘unconscious investments in conventional images of masculinity and femininity that cannot be easily reshaped’ (McNay Citation1999, 103). This in turn continues to reinforce and reproduce the male-dominant discourses and structures.

Conclusions and implications for practice

The data revealed that whilst most males and females worked in the confines of perceived masculine and feminine constructs (Brown Citation2005), it was the possession of masculine attributes reflecting the biological body that tended to dominate the gymnastics lesson. Valuing the ‘hegemonic masculinity’ discourse meant that male PSTs were emancipated by using their masculine attributes in an activity that has been historically perceived as a female field (Wrench and Garrett Citation2015; Westberg Citation2018). Whilst male emancipation is encouraging, some of the practices restricted the more marginalised PE bodies. This was at times disempowering and caused anxieties for those PSTs who recognised their subordination to traditional notions of masculinity.

Understanding why hegemonic masculinity came to dominate through context-specific pedagogical practices (such as those described in this paper), supports literature by Landi (Citation2017); Joy and Larsson (Citation2019) and Garrett and Wrench (Citation2019). For example, when the TE dictated content from the mobile website, PSTs were restricted in terms of what their bodies could and could not do. Most females would avoid the vault, as it required risk and force, and males felt uncomfortable performing what they perceived to be feminine movements such as leaping. For those PSTs, resisting ‘normal ways’ of performing gender would potentially disrupt the ‘heterosexual matrix’ (Joy and Larsson Citation2019, 502), in other words, what is to be male or female. On the contrary, offering PSTs more autonomy when using the mobile website, allowed them to take up different social spaces and did in fact lead to diversity in behaviours. However, despite this diversity, some bodies continued to be privileged over other bodies, as PSTs embodied gender norms, assessing themselves through a masculine habitus (see Bourdieu Citation2001; Brown Citation2005; Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2009).

In PE, there is currently too much focus on scientific measurements of the physical body (Landi Citation2017), which only works to reproduce gendered stereotypes. This is problematic when it results in some bodies being privileged over others. Gymnastics is an activity that has failed to shake the gendered connotations. (Westberg Citation2018), yet has the potential to offer diverse interpretations of how the body moves and is expressed. However, simply offering different pedagogical practices (didactic or autonomous) with or without mobile website technology, is not enough to challenge gender binaries.

If we are to offer male and female PSTs the confidence and knowledge to teach activities such as gymnastics, both TEs and PSTs need to understand the discursive gendered positions that they adopt. Whilst doxa are difficult to change due to the respected natural order of the world (Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2014), developing teaching strategies that encompass critical reflection can assist with PSTs understanding of their own and their peers’ bodily movements in gymnastics (McNay Citation2004). Furthermore, teacher educators (TEs) and PSTs should be equal, or ‘co-constitutive partners’ (Landi Citation2017, 11) in the construction of pedagogical practices that persistently disturb traditional notions of masculinity and that allow them to act differently in the field (Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2014). Regular experiences of alternative pedagogical practices can challenge the norms associated with masculinity and femininity and rather than reproducing them, we can begin to alter them at a non-conscious level. It is therefore recommended that when altering future practices, TEs’ are required to work with PSTs to explicitly and critically examine gender binaries and dominant discourses in PE, be supportive of change and in some cases transformation of pedagogy (Larsson, Fagrell, and Redelius Citation2014) and to co-construct transparency around assessments in gymnastics to include the appreciation of all bodies and with a greater emphasis on what is ‘uncomfortable’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Azzarito, L., and M. Solomon. 2005. “A Reconceptualization of Physical Education: The Intersection of Gender Race/Social Class.” Sport, Education and Society 10 (1): 25–47.

- Bailey, R. 2010. Physical Education for Learning: A Guide for Secondary Schools. London: Continuum.

- Benn, B., T. Benn, and P. Maude. 2007. A Practical Guide to Teaching Gymnastics. Leeds: Coachwise Ltd.

- Bourdieu, P. 1980. /1990. The Logic of Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 1993. Sociology in Question. London: Sage.

- Bourdieu, P. 2001. Masculine Domination. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- British Educational Research Association. 2011. “Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research. (viewed 6/04/2014).” https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/bera-ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2011.

- Brown, D. 2005. “An Economy of Gendered Practices? Learning to Teach Physical Education from the Perspective of Pierre Bourdieu’s Embodied Sociology.” Sport, Education and Society 10 (1): 3–23.

- Butler, J. 1993. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’. New York: Routledge.

- Byrman, A. 2012. Social Research Methods. 4th ed. Oxford: University Press.

- Charmaz, K. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. London: Sage.

- Charmaz, K. 2017. “The Power of Constructivist Grounded Theory for Critical Inquiry.” Qualitative Inquiry 23 (1): 34–45.

- Connell, R. 1987. Gender and Power. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Connell, R. 1995. Masculinities. St Leonards: Allen and Unwin.

- Connell, R. 2005. Masculinities. 2nd ed. Sydney: Allen & Unwin Australia.

- Connell, R. 2008. “Masculinity Construction and Sports in Boys’ Education: A Framework for Thinking About the Issue.” Sport, Education and Society 13: 131–145.

- Corbin, J., and A. Strauss. 2008. Basics of Qualitative Research. 3rd ed. London: Sage.

- Dennis, B. 2009. “What Does it Mean When an Ethnographer Intervenes?” Ethnography and Education 4 (2): 131–146.

- Denzin, N. K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 2011. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed. London: Sage.

- Department for Education. 2013. “National Curriculum for England: Physical Education Programmes of Study.” [online] (viewed 15/02/2015). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-physical-education-programmes-of-study.

- Devís-Devís, J., S. Pereira-García, E. López-Cañada, V. Pérez Samaniego, and J. Fuentes-Miguel. 2018. “Looking Back Into Trans Persons’ Experiences in Heteronormative Secondary Physical Education Contexts.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (1): 103–116.

- Evans, J. 2014. “Neoliberalism and the Future for a Socio-Educative Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (5): 545–558.

- Flintoff, A. 1993. “One of the Boys? Gender Identities in Physical Education Initial Teacher Training.” In Race, Gender and the Education of Teachers, edited by I. Siraj Blatchford, 74–93. Milton Keynes: Open University.

- Flintoff, A., and S. Scraton. 2006. “Girls and Physical Education.” In Handbook of Research in Physical Education, edited by D. Kirk, M. O’Sullivan, and D. Macdonald, 767–783. London: Sage.

- Garrett, R. 2004. “Negotiating a Physical Identity: Girls, Bodies and Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 9: 223–237.

- Garrett, R., and A. Wrench. 2019. “Redesigning Pedagogy for Boys and Dance in Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 24 (1): 97–113.

- Gibbs, A. 2017. “Focus Groups and Group Interviews.” In Research Methods and Methodologies in Education, 2nd ed., edited by J. Arthur, M. Waring, R. Coe, and L. V. Hedges, 190–196. London: Sage.

- Gorely, T., R. Holroyd, and D. Kirk. 2003. “Muscularity, the Habitus and the Social Construction of Gender: Towards a Gender-Relevant Physical Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 24 (4): 429–448.

- Green, K. 2008. Understanding Physical Education. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Grenfell, M. J. 2014. Pierre Bourdieu: Key Concepts. London: Routledge.

- Griggs, G., and D. McGregor. 2012. “Scaffolding and Mediating for Creativity: Suggestions from Reflecting on Practice in Order to Develop the Teaching and Learning of Gymnastics.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 36 (2): 225–241.

- Haerens, L., D. Kirk, D. Cardon, and I. De Bourdeauduij. 2011. “Towards the Development of a Pedagogical Model for Health Based Physical Education.” Quest (Grand Rapids, MI) 63 (3): 321–338.

- Hickey, C. 2008. “Physical Education, Sport and Hyper Masculinity in Schools.” Sport Education and Society 13 (2): 147–163.

- Joy, P., and H. Larsson. 2019. “Unspoken: Exploring the Constitution of Masculinities in Swedish Physical Education Classes Through Bodily Movements.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 24 (5): 491–505.

- Kirk, D. 1992. Defining Physical Education: The Social Construction of a School Subject in Postwar Britain. London: Falmer.

- Kirk, D. 2010. Physical Education Futures. London: Routledge.

- Landi, D. 2017. “Toward a Queer and Inclusive Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 23 (1): 1–15.

- Larsson, H., B. Fagrell, and K. Redelius. 2009. “Queering Physical Education: Between Benevolence Towards Girls and a Tribute to Masculinity.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 14 (10): 1–17.

- Larsson, H., B. Fagrell, and K. Redelius. 2014. “Symbolic Capital and the Hetero Norm as Doxa in Physical Education.” In Pierre Bourdieu and Physical Culture, edited by lisahunter, W. Smith, and e. emerald, 126–134. New York: Routledge.

- Larsson, H., M. Quennerstedt, and M. Ohman. 2013. “Heterotopias in Physical Education: Towards a Queer Pedagogy?” Gender and Education 26 (2): 135–150.

- Light, R., and D. Kirk. 2000. “High School Rugby, the Body and the Reproduction of Hegemonic Masculinity.” Sport, Education and Society 5 (2): 163–176.

- lisahunter, W. Smith, and e. emerald. 2015. “Pierre Bourdieu and his Conceptual Tools.” In Pierre Bourdieu and Physical Culture, edited by lisahunter, W. Smith, and e. emerald, 3–25. New York: Routledge.

- McNay, L. 1999. “Gender, Habitus and the Field: Pierre Bourdieu and the Limits of Reflexivity.” Theory, Culture & Society 16 (1): 95–117.

- McNay, L. 2000. “Gender and Agency: Reconfiguring the Subject in Feminist and Social Theory”. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- McNay, L. 2004. “Agency and Experience: Gender as a Lived Relation.” In Feminism After Bourdieu, edited by L. Adkins and B. Skeggs, 175–191. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Metcalfe, S. 2018. “Adolescent Constructions of Gendered Identities: the Role of Sport and (Physical) Education.” Sport Education and Society 23 (7): 681–693.

- Oliver, K. L., and D. Kirk. 2016. “Towards and Activist Approach to Research and Advocacy for Girls and Physical Education.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 21 (3): 313–327.

- Paradis, E. 2015. “Skirting the Issue.” In Pierre Bourdieu and Physical Culture, edited by lisahunter, W. Smith, and e. emerald, 84–91. New York: Routledge.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Philpot, R. 2016. “Physical Education Initial Teacher Educators’ Expressions of Critical Pedagogy(ies): Coherency, Complexity or Confusion?” European Physical Education Review 22 (2): 260–275.

- Schippers, M. 2007. “Recovering the Feminine Other: Masculinity, Femininity, and Gender Hegemony.” Theory and Society 36: 85–102.

- Scraton, S. 2018. “Feminism(s) and PE: 25 Years of Shaping Up to Womanhood.” Sport Education and Society 23 (7): 638–651.

- Shilling, C. 2004. “Physical Capital and Situated Action: A New Direction for Corporeal Sociology.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 25: 473–487.

- Sparkes, A. C., E. Partington, and D. Brown. 2007. “Bodies as Bearers of Value: The Transmission of Jock Culture via the ‘Twelve Commandments’.” Sport, Education and Society 12 (3): 295–316.

- Tinning, R. 2010. Pedagogy of Human Movement. New York: Routledge.

- Tracy, S. J. 2010. “Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 16 (10): 837–851.

- Velija, P., and G. Kumar. 2009. “GCSE Physical Education and the Embodiment of Gender.” Sport, Education and Society 14 (4): 383–399.

- Webb, R., T. Schirato, and G. Danaher. 2002. Understanding Bourdieu. London: Sage.

- Westberg, J. 2018. “Adjusting Swedish Gymnastics to the Female Nature: Discrepancies in the Gendering of Girls’ Physical Education in the mid-Nineteenth Century.” Espacio, Tiempo y Educación 5 (1): 261–279.

- Whitson, D. 1994. “The Embodiment of Gender: Discipline, Domination and Empowerment.” In Women, Sport and Culture, edited by S. Birrell and S. Cole, 353–371. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

- Wrench, A., and R. Garrett. 2015. “Gender Encounters: Becoming Teachers of Physical Education.” Sport, Education and Society 22 (3): 321–337.

- Wright, J., and J. Laverty. 2010. “Young People, Physical Activity and Transitions.” In Young People, Physical Activity and the Everyday, edited by J. Wright and D. Macdonald, 136–149. London and New York: Routledge.