ABSTRACT

Introduction

Reflection is established as important in coaching and coach development, however, no research has developed an illustrative device depicting an understanding of reflection in coaching. Instead, the concept remains poorly defined, understood, practiced and supported by coaches and coach developers. The purpose of this research was to therefore produce a device to support coaches’ thinking – their reflective practice.

Methods

Data were collected over a two-year period during a high-performance coach education programme delivered by a National Sports Organisation. Using an ethnographic framework, methods included participant observation of eight three-day coach education workshops, and interviews conducted at the start and end of the programme with high-performance coaches (n = 11) and coach developers (n = 12).

Findings and Analysis

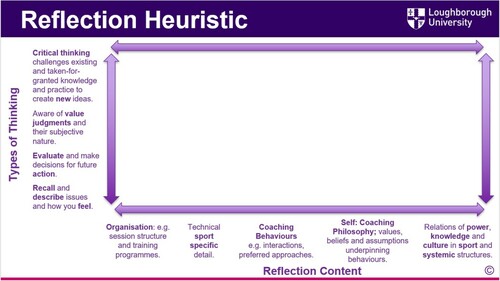

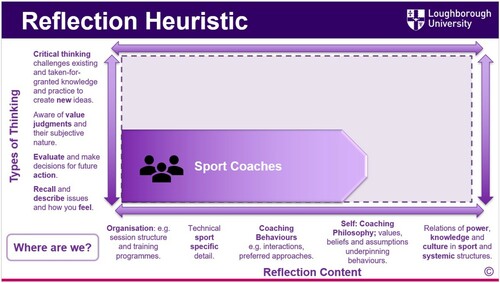

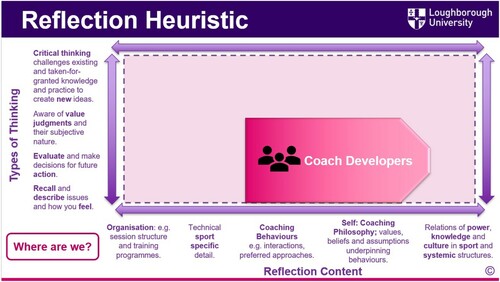

Based on the principles of grounded theory, analysis led to the production of a heuristic device that captures an understanding of reflection across two axes: types of thinking and reflection content.

Conclusion

On positioning the coaches’ reflective practice data within the heuristic, opportunities for assessment and intervention to develop reflection in high-performance coach education are presented and discussed.

Introduction

A considerable body of work (e.g. Cassidy, Jones, and Potrac Citation2009; Gallimore, Gilbert, and Nater Citation2014; Gilbert and Côté Citation2013; Gilbert and Trudel Citation2001, Citation2006; Irwin, Hanton, and Kerwin Citation2004; Knowles, Borrie, and Telfer Citation2005; inter alia) views and promotes reflection as an important mechanism that connects learning from experience to developing coaching practice. Indeed, Cushion (Citation2016) argues that those investigating reflection in coaching have been unanimous in agreeing that reflective practice is an essential part of coach learning, coaching effectiveness, and coach expertise (e.g. Gilbert and Côté Citation2013; Taylor et al. Citation2015). As a result, reflection has become positioned as an essential part of coaching and a staple in coach education programmes (cf. Downham and Cushion Citation2020).

In coach education and coaching practice discourse reflection is positioned as an individual, meta-cognitive strategy, progressing from simply considering ‘what coaches do’ to also include ‘what, and how coaches think’. As such, a dominant and taken-for-granted way of understanding reflection has evolved which portrays it as an individualistic and asocial process (Downham and Cushion Citation2020; Cushion Citation2016; Denison, Mills, and Konoval Citation2015). Like sport coaching more broadly, reflection has been assumed to be a known, linear, and neutral process that coaches progress through unproblematically as they follow a ‘sequence’ or ‘cycle’ (e.g. Taylor et al. Citation2015). While different theoretical lenses have been applied to understanding reflection, its processual nature has been commonly represented via the simplistic steps, spirals, levels, or cyclical models often produced (e.g. Gibbs Citation1988; Johns Citation1995; Moon Citation2004; Schön Citation1987; Van Manen Citation1977). Irrespective of the theory, unproblematically completing the ‘steps’ or progressing through the stages, results in the assumption that practitioners have developed their knowledge and even transformed their thinking and practice. These models, however, are often what Cushion, Armour, and Jones (Citation2006) and Lyle (Citation2002) describe as models for a process (i.e. idealistic representations) rather than models of a process (i.e. generated via empirical research). This is particularly the case in coaching and often compounded by the use of conceptual devices that have been co-opted as pedagogical tools. In other words, coaching has tended to (mis)apply models for reflection from other contexts (e.g. professional development, education, nursing, teaching) rather than generate an empirically based understanding of reflection from which to create its own models. Importantly, the application of models for reflection in coaching has been disappointing in terms of results with research consistently and repeatedly showing limited development of coaches’ reflective practice (e.g. Carson Citation2008; Cropley et al. Citation2011; Hughes, Lee, and Chesterfield Citation2009; Knowles et al. Citation2001; Knowles et al. Citation2006; Stoszkowski and Collins Citation2014). While there is a well-established and accepted discourse surrounding reflection in coaching (e.g. Knowles et al. Citation2001; Taylor et al. Citation2015; Trudel, Culver, and Werthner Citation2013), its outcome has been reflective practice with superficial engagement by coaches and limited impact on coaching practice (Stodter and Cushion Citation2014).

Problems with coaches’ engagement with reflection have been attributed to a lack of understanding about the concept and practice (Cropley, Miles, and Peel Citation2012) as details about what reflection is and how to do it have gone unstated and are often assumed (Cushion Citation2016). Without conceptual anchors, Cushion (Citation2016) argues that reflection has become ‘a slogan disguising a range of practices – with differing understandings’ (2). In other words, the way coaches understand, and practice reflection remains uninformed and varied (e.g. Cropley, Miles, and Peel Citation2012; Downham Citation2020; Knowles et al. Citation2006; Stodter, Cope, and Townsend Citation2021). If coaches are to realise the benefits of reflection, clearer understanding through conceptual development and application of this through guidance for practice is required. Indeed, as Cushion (Citation2007) argues limited or decontextualised, models, dressed in ‘theoretical tinsel’ (Everett Citation2002, 58) can gain a concreteness once framed. This means that, ‘while their succinctness and portability have a focussing effect, they can also ossify practice around their inertness, and thus hinder the very conceptual and practical development they are designed to promote’ (Cushion Citation2007, 398). For the practitioner, such representations of reflection and its practice are disconnected from the influence of the coaching context and become frozen into a narrative that does not capture the richness of coaching practice. Moreover, uncritically importing theory and reflective practice approaches from other disciplines into coaching runs the risk of compounding already limited thinking (Cushion Citation2011).

This disconnect from context in particular is problematic given coaching is an autonomous practice field, socially constructed, and subject to relations of power (Mills, Denison, and Gearity Citation2020). These influencing factors were absent from the considerable body of work discussing reflection in coaching until recently (e.g. Cushion Citation2016; Denison, Mills, and Konoval Citation2015; Downham and Cushion Citation2020). Such discussions have begun to confront the taken-for-granted of reflection (i.e. it’s meaning, practice, and outcomes) and showed that the practice can have several (sometimes unintended) consequences. For example, reflective practice has been found to discipline and shape coaches into accepted ways of thinking as well as foster transformative changes (Downham and Cushion Citation2020) – hence reflection outcomes can be multi-directional for coaches with positive and negative effects operating at the same time. Exposing these possibilities challenges the exclusively positive and unidirectional rhetoric of reflection and expands the boundaries for understanding the concept and practice.

If coaches and coach developers are to consider what their reflective practice (i.e. via meta-cognition) and reflective practice support is doing (i.e. its effects) to coaching beliefs, knowledge, and practice we need research to develop, expand, and integrate coaching-specific ways of understanding reflection. To achieve this deliberate focus, a sophisticated and multi-directional way of interpreting and assessing reflective practice is required. Therefore, the aim of the current research was to develop an empirically grounded understanding of reflection and reflective practice in high-performance coach education. The purpose was twofold. First, to contribute to the conceptual development of reflection providing conceptual anchors for practitioners. Second, from this conceptual clarity or explanatory detail, to create a multi-directional thinking tool, or heuristic, of reflection that enables reflective practice to be guided, interpreted and its ‘levelness’ to be assessed. The significance of the work lies in moving reflection beyond its ‘sloganistic’ nature and differing understandings toward fulfilling its transformative potential (Brookfield Citation2009) and away from coaches practicing reflection in radically different ways, if at all (e.g. Cropley, Miles, and Peel Citation2012; Downham Citation2020; Knowles et al. Citation2006). That is, to challenge existing beliefs and assumptions (Brookfield Citation2017), to develop knowledge (Cushion Citation2016) – in light of the broader social context (e.g. discourse and power-relations) in which the coach is positioned and constructed (Fook Citation2015; Thompson and Pascal Citation2012) – and to develop coaches and their practice.

Methodology

Research context

The setting was a high-performance coach education programme, delivered by a National Sports Organisation (NSO). The programme was spread over a three-year period and involved residential workshops every three to four months, in-situ visits, and one-to-one coach development support. The programme was believed to offer unique experiences and opportunities for coaches from a variety of sports and working at the highest performance level (i.e. national sport/team coaches). The programme design emphasised learning from the coaches’ own experiences and opportunities through reflection. A key objective of the programme was, therefore, to support and develop coaches’ reflective practice. NSO staff worked as on-programme coach developers responsible for organising and delivering workshops, visiting coaches in-situ, and providing feedback. One-to-one coach developers were contracted to the programme and assigned a coach who they met with face-to-face or online every four to six weeks. The coaches involved in the research had full-time coaching roles – at the forefront of high-performance coaching – working in national sport. The research reported here forms part of a larger 24-month ethnographic study that analysed the delivery and impact of the education programme on developing reflection and reflective practice.

Participants

On receiving ethical approval, participants were eleven high-performance coaches, eight one-to-one coach developers and four on-programme coach developers. Each coach is described individually in providing the space for each participant to ‘highlight critical episodes and events’ (Webster and Mertova Citation2007, 69) that give insight into their understanding of reflection. That is, the coaches’ understanding of their experience and approach to reflection and coaching. Together, the details show that practice and conceptions of reflection were broad and varied and thus coaches operated without a consistent underpinning. Pseudonyms have been used throughout.

Table 1. Participant details: coaches.

Procedure and methods

Data collection was organised into three phases, as shown in :

Table 2. Data collection phases and organisation.

Data collection phases and organisation

Each phase included observations of programme workshops (n = 8). These workshops typically ran for three days at a time, with lecture-style sessions, group work and practical activities observed. Fieldnotes were recorded throughout and included descriptive and logistical detail such as the location, attendees, interactions, and activities undertaken. Audio recording supported the write up of full fieldnotes that also included initial reflections on the observed events and the identification of analytical ideas (Bryman Citation2016). In addition, coaches participated in two one-to-one semi-structured interviews one at the start of the programme and another 17 months later (shown above in under phase one and phase two of the research). These interviews explored the coaches’ understanding of reflection and how this understanding changed over the course of (and in response to) the education programme. For example, the coaches were asked similar questions in both interviews such as ‘what do you do when you reflect on your practice?’ ‘How does your reflective practice link to learning?’ A total of twelve coach developers (on-programme n = 4, one-to-one n = 8) also took part in two one-to-one semi-structured interviews 17 months apart. Likewise, how reflection’s meaning was understood throughout the programme, and how the coaches were perceived to have developed their reflective practice was explored. Finally, one-to-one interviews conducted with five one-to-one coach developers (one coach developer was no longer working with their coach, and two coach developers were not available) served to substantiate the grounded theory (details about this phase are outlined in the analysis section). Significantly, sustaining a position in the field of inquiry during workshop observations and capturing moments of understanding through interviewing enabled a methodology that supported the progressive build-up of in-depth and longitudinal data (cf. Stodter and Cushion Citation2017).

Analysis

Based on the principles of grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2014), data from semi-structured interviews and observational work were organised and analysed through a flexible analytical strategy. While articulated here for clarity as a five-stage process, the analysis was iterative and interlinked.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the workshops presented as full fieldnotes. The full fieldnotes included complete dialogue during reflection tasks and group discussions to capture what happened in detail. Together, this formed a detailed description of the coach education programme and reflection practices, amounting to 445 pages of transcription.

Initial coding involved line-by-line analysis to categorise segments and summarise data. In doing so, we identified what the data were about as well as salient and significant pieces of information (cf. Groom, Cushion, and Nelson Citation2011). For example, data extracts related to ‘types’ of reflection were highlighted and labelled within the transcripts if they shared common characteristics (e.g. denoting multiple meanings and practices of reflection) and included key words (e.g. surface/depth/deeper, in-session/after-session, action/thought).

Focused coding sought to group initial codes, for example, linkages between initial codes such as ‘what went well?’, ‘how can I do better next time?’ and ‘what does this mean for the next session/interaction?’ were identified and positioned within the sub-category ‘evaluation and action’.

Subsuming initial codes through linkages was supported by memo writing and drawing upon existing literature. On analysing components of codes and capturing comparisons and connections between data, codes, and relevant reflection literature (e.g. Brookfield Citation1998; Citation2009; Citation2017; Cushion, Griffiths, and Armour Citation2018; Ghaye Citation2010; Gibbs Citation1988; Kuklick, Gearity, and Thompson Citation2015; Lyle and Cushion Citation2017; Mezirow Citation1998; Moon Citation2004; inter alia) we were able to further construct our analytic notes to explicate and form three categories (types of thinking, reflection content, emptiness/complexity). These categories were highlighted as significant in contributing an understanding of reflection.

Following Charmaz (Citation2014), theoretical sampling sought to gather more data to develop the grounded theory by elaborating and refining the categories. To do so five one-to-one coach developers participated in two one-to-one interviews three months apart (as detailed above in ). The first interview focused on sharing and explaining the grounded theory and gathering the coach developers’ initial thoughts. The second interview revisited the theory, gathered more detailed feedback on the theory, and considered the coach developers’ experiences of introducing the theory into their one-to-one coach development sessions. In line with considerations of research quality, these follow-up interviews generated additional insight and dialogue about the research findings (cf. Smith and McGannon Citation2018) and functioned as a resource to deepen and extend analytical interpretation (cf. Smith and Caddick Citation2012). In response, the theoretical constructs and how they were presented evolved and developed. For example, the illustrative representation (the reflection heuristic) was edited to communicate the intentions of the theory more clearly (e.g. additional arrows across the top and right-hand side, changed title ‘framework’ to ‘heuristic’). Crucially, none of the coach developers proposed a reflective conversation example that could not be either positioned on, or assessed and explained using, the theory.

Following Cushion, Griffiths, and Armour (Citation2018) the design of the study facilitated the linking of data from different sources and over time, allowing an identification of the layers of collaborative evidence that was used to increase understanding, but was no guarantee of ‘validity’ in traditional terms. From this process, robust categories and penetrating analysis were developed that contributed to an understanding of reflection that is ‘conceptually dense and grounded in the data’ (Charmaz Citation2014; Schwandt Citation2001, 111; Smith and McGannon Citation2018). In line with the experiences of researchers adopting grounded theory principles elsewhere, the ‘theory-building process was not linear and relied upon the … analysis of data (i.e. the iterative process described above)’ (Groom, Cushion, and Nelson Citation2011, 20; Holt et al. Citation2017; Stodter and Cushion Citation2017).

Findings

A reflection heuristic

The grounded theory in this case is operationalised as a reflection heuristic. A ‘heuristic’ relates to any ‘procedure which involves the use of an artificial construct to assist in the exploration of social phenomena’ (Scott Citation2014, 44). On presenting a reflection heuristic in coaching, we contribute to setting out, as clearly and explicitly as possible, reflection’s ‘salient features’ by providing ‘analytical clarity and explanatory value’ about the concept and practice (Scott Citation2014, 44). That is, the reflection heuristic illustrates an understanding of reflection in high-performance coach education. In what follows, presents the whole heuristic, then the heuristic (e.g. types of thinking and reflection) is explained in detail. The results of the analysis are presented alongside data examples integrated into the heuristic (e.g. ). Presenting data from the study explains, positions/maps coaches’ reflective practice, highlights points of development for coaches and coach education and supports in demonstrating the width and transparency of the research (cf. Smith and Caddick Citation2012).

The heuristic has two continuums () that detail along its horizontal axis reflection content and its vertical axis types of thinking. These axes are central elements in the understanding of a broad concept of reflection. The types of thinking presented, and the items of reflection were initially grounded in the depth of reflection literature (e.g. Brookfield Citation1998; Citation2009; Citation2017; Gibbs Citation1988; Kuklick, Gearity, and Thompson Citation2015; Lyle and Cushion Citation2017; Mezirow Citation1998; Moon Citation2004; inter alia) and then refined throughout the analysis as reflection and its processes were observed on the programme and discussed with the participants. The ‘empty space’ of the heuristic enables reflection to be positioned (detailed further in the subsequent sections) and shows where variation and differences may then be situated and operationalised. The empty space represents the potential to illustrate the non-linear and ‘messy’ nature of reflection in practice as coaches’ reflective practice and coach developers’ support could not be pigeon-holed but moved fluidly across the space (‘it’s like a dance’ – one-to-one coach developer) (cf. Handcock and Cassidy Citation2014; Schön Citation1987). For example, coaches on the programme identified issues related to coach behaviour; a reflective conversation then travelled across different types of thinking. Importantly, the nature of the conversation and the type of thinking applied led to different types of outcomes for similar issues. Indeed, findings showed that changes in content may occur in response to different types of thought and vice versa. For example, coaches reflected on their behaviours in ways that explored alternative perspectives (e.g. how might someone else have behaved in that situation) and this led to a focus on their coaching philosophy (e.g. their beliefs and assumptions). Indeed, critical thinking on some content may lead to descriptive or evaluative thinking on other content. For example, coaches reflecting on technical sport-specific detail in critical ways (e.g. how have I come to think in these ways about this attacking strategy?) were then found to offer a descriptive consideration of relations of power and knowledge in sport and systemic structures.

Therefore, although the two continuums are ‘separate’ positionality on each influence, respond to, and interact. While this interaction is crucial for illustrating the intricacies of reflection so too is the ‘separation’ of reflection content from types of thinking. To be specific, analysis identified that reflection content valued by coaches (e.g. reflecting on coach behaviour) often differed to that valued by coach developers (e.g. a focus on self, philosophy, assumptions and beliefs). This had wider political effects because it established reflection ‘norms’, that were focused on the ‘right’ content, as well as coach developers and course staff as judges of normality where reflection was judged as ‘good’ or ‘critical’ (cf. Downham and Cushion Citation2020). This reflects similar conceptions in previous literature shaped by psychological approaches where reflection is a neutral and benign process while also accrediting certain reflection content to notions of ‘deeper’ (read ‘better’) reflection (e.g. Gilbourne, Marshall, and Knowles Citation2014; Taylor et al. Citation2015). However, the findings in this case point to the complexity of reflection in coaching and shine a light on its (political) influences and mechanisms as a disciplinary device (cf. Cushion Citation2016; Downham and Cushion Citation2020). Therefore, ‘separating’ thought from content helps to show that a coach may reflect on all content in several ways and that all types of thought may be beneficial at different times to different coaches. Indeed, and in contrast to recent work, ‘simply thinking about’ coaching practice may well be a beneficial endeavour for some or a complete waste of time for others (Stodter, Cope, and Townsend Citation2021, 8). On broadening and accepting the possibilities that make up reflection in coaching the heuristic fosters a less disciplinary interpretation of reflective practice content, and greater breadth of possibilities. Significantly, this is the first research to consider and present reflection in this way and therefore broadens our understanding of the concept and practice.

Vertical axis: types of thinking

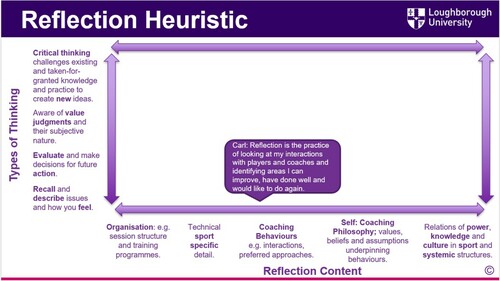

The vertical axis, ‘types of thinking’, refers to a continuum of four different ways that coaches were found to think about their practice (cf. Gibbs Citation1988; Kuklick, Gearity, and Thompson Citation2015; Moon Citation2004). The first was identified as ‘Recall and describe issues and how you feel’. For example, coaches started reflective conversations by recalling and providing an account of what had happened through a description of the coaching problem, as Carl does so below:

Phase Two Interview:

Lauren: Ok so what might be useful for me, could you talk to me about an example …

Coach – Carl: One player who has played for [Country] … a large amount of time and has then not performed on certain occasions when we need him to perform, and then has had big moments in games but under performed in games especially big games.

The second type of thought on the vertical continuum focuses on evaluative thinking (e.g. ‘what went well?’) with a view to making decisions and producing action. In a similar way to recent research (e.g. Stodter, Cope, and Townsend Citation2021), coaches in the current case framed reflective practice within a cyclical process. Analysis identified that this process was grounded in thinking about and evaluating practice and behaviour to inform future sessions. Such approaches were consistent with ‘versions’ of reflection promoted elsewhere (e.g. Gibbs Citation1988) as well as being typical in coach education curriculum. Perhaps as a result, evaluative thinking was the most common type of thinking throughout the programme and was often connected to the meaning of reflection as this example positioned on the heuristic is shown in .

Understanding and practicing reflection with an evaluative emphasis meant that coaches cast value judgements on their practice. Following value judgements coaches considered what action to take to resolve an identified issue(s) and change practice. Thinking in this way, meant that coaches’ reflective practices remained inward looking (Stodter, Cope, and Townsend Citation2021), within what Brookfield (Citation1995) described as ‘the perceptual frameworks’ that determined how coaches viewed their experiences (28). This meant that ‘changes’ to practice were sourced from a catalogue of known practices and were not therefore innovative or new but instead served to confirm pre-existing ideas and assumptions about coaching as coaches remained tied to specific ways of thinking and doing (cf. Cushion Citation2016; Denison, Mills, and Konoval Citation2015).

Reflective practice that reached beyond a coaches’ catalogue of practices and searched for different views and perspectives (e.g. from athletes, colleagues, personal experiences, and/or theory and research) with an awareness of personal preferences (i.e. value judgements and belief systems) was less commonly reported or seen throughout the programme. Brookfield (Citation2017) argues that reflection that demonstrates an awareness of value judgements and their subjectivity begins to represent critical thinking. In the case of this research, this is the third type of thought on the vertical continuum (e.g. how might someone else view this issue differently?). For example, coaches detailed an appreciation of different perspectives and encouraged each other to consider how someone else in their team might view coaching issues differently, while one-to-one coach developers spoke about supporting an increased awareness of multiple perspectives as shown here with Stuart and Louise, and then with Janet:

Phase Two Interview:

Coach – Stuart: I found her [coach developer] positioning from CEO (Chief Executive Office) perspectives really helpful, because you don’t always put yourself in their shoes, bigger picture stuff, they have got to get their outcomes so ‘what do they need?’.

Fieldnotes

Residential Workshop:

The coaches sit in a semi-circle and listen to each coach presentation – delivered on the projector screen. On completing his presentation, Daniel stands next to the computer and faces questions from the cohort about his presentation:

Coach – Louise: You talk about your coaching and leadership hat, what would the coach advise you about the long-term strategy, as a leader?

Later in the conversation,

Coach – Louise: If you were in their position, what would you want from you?

Phase One Interview:

One-to-one Coach Developer – Janet: The intended outcome is to get them to challenge what they have been doing and reflect on … ‘okay have you thought about it from their point of view?’ … So, if someone is behaving towards you in a certain way; ‘well have you thought about why they may be doing that?’.

Finally, the fourth type of thinking on the heuristic focuses on critical thinking that challenges taken-for-granted knowledge and practice to create new ideas. This type of thinking was connected to the programme’s intentions, on-programme coach developers’ understanding of reflection and the role of one-to-one coach developers:

Phase One Interview:

On-programme Coach Developer – Will: I think it is the ‘ability to critically appraise activity or action with a view to learning from that critical thinking and thought process to apply that learning in the future context’ … I am interested in their reflections on what they have heard, liked, didn’t like, and why, the next steps.

Phase Two Interview:

One-to-one Coach Developer – Isla: It is incredibly difficult for some of the really skilled coaches to see the system and their part of the system and they will never see all of it and it is [coach developers] that helps them deeply reflect that helps them shine a light into the places they don’t even know to look.

To achieve critical thinking, coach developers referred to an inquiry-based approach. This approach aligns with reflection literature that has promoted ‘the “why-type” question: “why do I/we coach in this way?”’ (Ghaye Citation2010, 10) as a means to support coaches to reach and demonstrate critical reflection (Handcock and Cassidy Citation2014). In this way, reflection can support coaches to consider how knowledge is constructed and challenge the apparently ‘normal’, ‘unquestionable’ appearance of taken-for-granted coaching practices and preferences. This type of thinking is required to sustain development and remain open to new ideas (Brookfield Citation2017; Cushion, Ford, and Williams Citation2012). However, evidence of critical thinking and coach developer support fostering critical inquiry remained limited and uneven throughout the two years of the education programme. Indeed, time to encourage and practice such thinking was short – buckling to the on-course pressures of ‘more content’. Typically, coaches’ answers to ‘why? questions’ were more consistent with rationalisations of practice (as suggested earlier), as coaches justified their approaches rather than examining their assumptions and taken-for-granted thinking and practice. Put differently, findings indicate that asking particular questions did not guarantee a response representative of a particular ‘type’ of thinking:

Phase Two Interview:

Lauren: I am wondering where that emphasis on the player has come from … where has that belief come from?

C2 Coach – Carl: I think my focus was on the units and team and the individual comes along with the unit or the team but now I think there is a change and understanding the importance of the player the getting a result with the player and treating all of the players the same is not going to work.

Horizontal axis: reflection content

The horizontal axis details a continuum of ‘what’ coaches might ‘reflect on’. First, it identifies that coaches’ reflection could focus on ‘Organisation (e.g. session structure and training programmes)’. Coaches in this research were involved in designing and delivering sessions and training programmes, for example:

Phase One Interview:

Coach – George: I build the altitude programme … every athlete follows the programme I set … I … sit down and have a think ‘how should we do this now?’, and that impacts on the programme. The programme will change if I go ‘I don’t think that is working’.

The second salient feature of reflective practice on the education programme related to content focused on technical sport-specific knowledge. Lyle and Cushion (Citation2017) explained that a coach might have a ‘set of beliefs about the advantages and disadvantages of specific preparation methods, offensive or defensive strategies or desirable performer qualities’ (235). These aspects were evident in the coaches’ reflective practice conversations as shown here:

Phase Two Interview:

Coach – Stuart: We felt we hadn’t given clarity in ‘how we play’ so we had altered the playing system and some new players had come into the team, but had we been really clear on what the patterns of play were and what the solutions were? Some things that happened would have been decision making and technical ability, but somethings were definitely down to [us], we have got to get these messages clear as a group of coaches to give players a structure to play from.

Phase One Interview:

On-programme Coach Developer – Tim: The NSO focuses on self, performance leadership, relationships and then technical knowledge/sporting intelligence, so we only concentrate on three, it is unfair or impossible for us to give technical feedback, so the focus is on the other three … I think people are happier to talk about things like that [technical] because they know it and it’s more technical, it’s where they are comfortable.

While recognising that coach developers might not hold detailed technical knowledge across multiple sports, these beliefs about coach development (i.e. you have to know more than the coach) meant that opportunities for such content to act as the gateway to different types of thinking were missed and dismissed on the programme. Not having detailed technical knowledge does not mean that coach developers cannot recognise opportunities to challenge the veracity or evidence base of technical knowledge, for example asking ‘how did you come to know that?’ or ‘are these assumptions evidence informed?’ Highlight aspects of technical knowledge, for example, ‘I notice you have strong beliefs about “x”’; and signpost to others who might support reflective practice about technical knowledge, for example, ‘who in your sport might provoke and challenge your thinking about “x”?’ Indeed, reflection content focused on technical sport-specific knowledge was subjugated as the ‘basics’ of reflective practice as these data show:

Phase One Interviews:

On-programme Coach Developer – Alan: It is unfair or impossible for us to give technical feedback … The harder part for people is on relationships, knowledge of self and leadership, so not so much on the technical … looking to get an emphasis on that.

Coach – George: A coach’s problems may just be the coaching programme or technique, whereas I am dealing more with people. That’s what I would be doing more reflection on … Coaches probably reflecting about whether they should do weights on Thursday or Saturday morning … lots of coaches don’t get that it’s a person you’re coaching, not necessarily the technical stuff. Someone who is aware of themselves, what they’re doing and able to reflect is a better coach in my opinion.

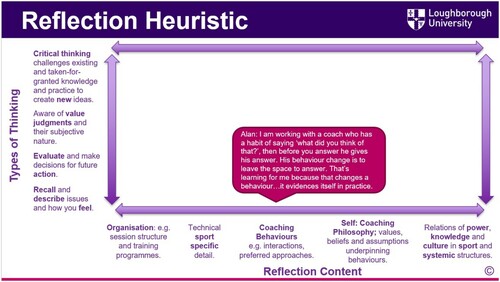

Reflection content focused on ‘coaching behaviours (e.g. interactions and preferred approaches)’ concentrates on what coaches do when they coach, their preferences, effectiveness, what underpins these and the consequences of their behaviours. Analysis identified that coach behaviour was a central consideration during reflective practice for both coaches and coach developers who connected reflection to learning through observations of changed behaviour as this example positioned on the heuristic show:

In addition, reflection focused on coach behaviour, such as shouting, were used to demonstrate reflective practices, as the example from residential four with Will, Carl and Louise below demonstrates:

Fieldnotes:

Residential Workshop Four:

Presenting interim findings to the coaches and the on-programme coach developers. The coaches and coach developers are sat in a large circle that fills the room, there is a small opening towards the projector that I have referred to throughout the session. I am also sat while sharing the interim findings. Specifically, I am sat on the third chair in from left of the projector, Carl is sat to my left, and Louise two from my left, next to Carl. Will is sat to my right, at the ‘back’ of the circle and therefore facing the projector screen directly. On detailing different types of reflection, that included critical thinking, Carl brings the conversation back to ‘coaching’, that he associates with behaviour, this content is then taken by Will as an example on which to demonstrate a reflective conversation that includes different types of thinking:

Coach – Carl: This is getting complicated, what we are talking about here is coaching isn’t it, we are trying to get something to happen you realise it needs to be done better or differently because you observe it, you then decide on how you’re going to do it better, then it might be that you question the guy it might be that you pose something non-direct, or it might be that you shout something, whatever it might be, you the step back out because you want see the result.

On-Programme Coach Developer – Will: So, what’s that based on? Let’s take that, what’s that based on, what’s that belief that that’s going to ‘work’ based on? Which is I guess what Lauren is asking.

Coach – Carl: That person, unit work or whatever it was, or that person responds in that sort of way.

On-Programme Coach Developer – Will: Your knowledge of them as a person, there must be a hypothesis of ‘that’s going to work’, so at some point the real deep reflection of ‘I believe that shouting at people will at the right time work’ – that’s a belief, so where did that come from. What we are saying is another person might go ‘shouting at somebody never works’ and that’s my belief and therefore I wouldn’t do it.

Coach – Louise: But your reflection and ability to reflect is knowing what state that person is in to know what the right time is to shout and when is the right time to support, and if you haven’t been in that reflective process …

On-Programme Coach Developer – Will: You’re saying that on the basis that shouting is right at any time because that’s your assumption whereas I might challenge, my own belief that actually I think shouting at the right time based on all of these factors that I have assessed is right. But actually, I am challenging myself at a critical level ‘do I genuinely still believe that shouting at somebody is right?’.

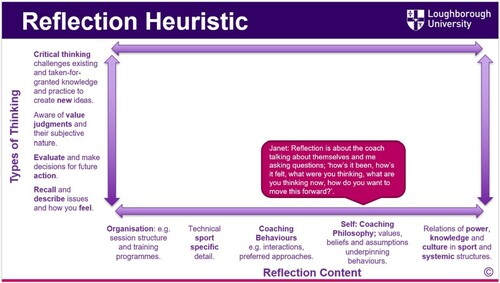

‘Self; coaching philosophy; values, beliefs and assumptions underpinning behaviours’ were common reflection content on the education programme. The first year of the programme was dedicated to raising self-awareness and ‘knowing-yourself’ as coach developers asked questions such as ‘what did you learn about yourself’ and framed their approach in ways such as that positioned on the heuristic below:

These findings show that a consideration of ‘self’ was an example of reflection content valued (by coach developers) on the programme. As suggested, this focus on ‘self’ aligns with literature that has promoted such content as representing a greater depth of reflection (e.g. Gilbourne, Marshall, and Knowles Citation2014). However, and importantly, the findings suggest that this content alone is not a guarantee of reflective depth and positioning the detail on the heuristic shows this topic can be considered in a descriptive way. Importantly, content alone does not ‘qualify’ reflection automatically to be classed as critical.

Until recently, research has also overlooked how social factors influence coaches’ reflective practice (Cushion Citation2016). However, as discussed elsewhere (see Downham and Cushion Citation2020), reflection and coach developers’ practice are a condition of, and conditional upon, these influences. Indeed, the culmination of evidence from a range of research has shown that these influences play a fundamental role in coaching – a social activity (cf. Denison Citation2010; Cushion and Jones Citation2014; Konoval, Denison, and Mills Citation2018). Therefore, reflection content includes the final piece of content on the continuum; ‘relations of power, knowledge and culture in sport and systemic structures’. Incorporating this content into the heuristic moves the meaning of reflection beyond, what Cushion (Citation2016) identified as, individualist understandings, reinforced through humanistic discourses, towards support that considers the social, beyond the interactional (Jones, Edwards, and Filho Citation2014). One-to-one coach developers spoke about reflection content that considers coaching in terms of its social context:

Phase Two Interview:

One-to-one Coach Developer – Isla: When we get to the culture piece [during reflective conversations] or the really deep roots that’s the unconscious, that’s the systemic stuff that’s the patriarchal society that people don’t know we are in.

Positioning coaches and coach developers

Mapping coach data to the heuristic helps show what was happening with the coaches’ reflective practice on the programme. and below present a broader picture of this mapping, and thus the areas that coaches’ reflective practice () and coach developer support () occupied consistently during the coach education programme. and reiterate that reflective practice conversations during the education programme were often descriptive and evaluative, with limited awareness of judgement subjectivity and critical thought. Reflection content focused on session organisation, technical detail, and coach behaviour, with some consideration of self. Meanwhile, coach developer support (see ) nudged thinking towards an appreciation of multiples perspectives on occasion, and focused on coaching behaviours and self, with some consideration of culture in systemic structures.

On positioning participant data in this way, we can begin to assess coaches’ reflective practice and identify means that may develop a greater breadth and depth to reflection (i.e. reflective practice that occupies more/all areas on the heuristic), long advocated in the literature (e.g. Handcock and Cassidy Citation2014; Knowles et al. Citation2001; Stoszkowski and Collins Citation2014, inter alia). Following such assessment, the heuristic helps to identify areas that both coaches’ reflective practice and coach developer support could be directed with a greater appreciation of multiple perspectives, critical thought, and consideration of relations of power, knowledge, and culture in sport structures. Put differently, both coaches’ reflective practice and coach developer support could be directed towards an exploration of the ‘blank’ areas on the heuristic (i.e. where reflective practice was not occurring). Brookfield (Citation1998) connected an awareness of value judgement to an appreciation of multiple perspectives through four complementary lenses – applying this to coaching, a coach may therefore reflect on their practice from their own perspective, that of their athletes/players/participants, fellow coaches/colleagues (e.g. head/assistant coach, performance director, strength and conditioning coach), and the lens of theoretical, philosophical and research literature. When thinking in these ways, coaches’ reflective practice may lead to the identification and exploration of the assumptions that frame their practice. Such inquiry is critical when coaches aspire to move beyond, and become aware of, their own interpretive filters (Gilbert and Trudel Citation2001; Stodter and Cushion Citation2017) or frames of reference (Mezirow Citation1991). That is, the habits of mind, points of view and immediate expectations, beliefs, feelings, attitudes, and judgements (Mezirow Citation2000) that shape interpretations and confirm assumptions in coaching situations.

These aspirations are not easy to achieve, however. Indeed, ‘we find it very difficult to stand outside our perceptual framework and see how some of our most deeply held values and beliefs lead us into distorted and constrained ways of being’ (Brookfield Citation1998, 197). The difficulty for coaches (and coach developers) to ‘see’ their own subjectivity and its effects is partly because their subjective experiences and knowledge have been shaped by historical and cultural circumstances (i.e. social factors) and their subjective perceptions are an effect of these factors (Cushion Citation2016; Fendler Citation1999). This means that coaches’ practices operate in ways that are not entirely conscious (Cushion and Partington Citation2016) but require support to ‘participate in discourse to validate beliefs, intentions, and values’ (Mezirow Citation1998, 197). That is, coaches find it difficult to offer justifications about their practice in light of social factors (i.e. relations of power-knowledge and culture in systemic structures; see ) and critically examined core assumptions about why they do what they do (Brookfield Citation1998).

The coach education programme in this case was ambitious and had as its stated aims to support such discourse to have transformative effects on coaches’ perspectives (i.e. categories for understanding) and schemes (i.e. beliefs, knowledge, judgement, and action). The programme hoped to shape how coaches might interpret and respond to their coaching practice experiences and problems. However, as suggested, perspective transformation involves becoming critically aware of ‘habits of perception, thought and action [and] the cultural assumptions governing the rules, roles, conventions and social expectations which dictate the way we see, think, feel and act’ (Mezirow Citation1981, 13). The programme did not overcome this challenge as findings identified discrepancies between the programme’s transformational intent and the realities of what happened at workshops. The coaches’ existing perspectives were not challenged and remained a filter through which the programme’s content had to pass. In particular, the coaches were typically asked; ‘how does this land for you?’, ‘could this idea be applied to your context?’, ‘what will you take from this workshop?’ Rather than questions that may have moved toward the type of thinking needed to engage with the material in different ways. For example, ‘what has led you to “take” “x” but not “y” from this workshop?’ Although the prompts delivered on the education programme supported reflective practice that solved problems within a given structure (i.e. within their existing perceptual framework) they did not support critical thought about the foundations and imperatives of the system itself to explore alternatives, nor a consideration of social factors (e.g. uncovering and challenging relations of power that frame coaching practice). Indeed, the effects of socialisation, power, history and culture on subjectivities and meanings (cf. Cushion Citation2016) did not feature on the programme. This meant that although the coaches were inquisitive during education workshops their scepticism about new ideas was related to instrumental means of whether they would ‘work’ if applied to the existing system alone rather than more transformative questions concerning the system itself (cf. Brookfield Citation2009). Indeed, coaches did not consider critically how culture and time determined their perceptions about what would ‘work’ in their context (Mezirow Citation1998), nor did they inquire about whose interests were being served through the codes of practice upheld by ‘external experts’, the NSO and fellow coaches. Without support to think in the ways required to transform their perspectives, coaches remained unaware of their assimilation to cultural norms (e.g. in high-performance coaching or their sport), and therefore missed the opportunity to explore how their self-understanding was derivative of understanding others (Giddens Citation1976) and enmeshed in an incessant negotiation with context.

Implications

As Cushion (Citation2013) argued, uncovering assumptions and beliefs about practice can emancipate practitioners from their dependence on habit and tradition providing them with the skills and resources to enable reflection, and to critically examine the inadequacies of different conceptions of practice. However, despite its best intentions learning in this way was rare, and often beyond the conception of coach development in this case. Rather than engaging reflection to be critically transformative (deconstructing taken-for-granted beliefs, assumptions, knowledge and habits, and rebuilding practice) the practice was instead additive (behavioural re-tooling and grafting new ‘skills’/knowledge onto an existing repertoire). This dearth of critical thinking during reflective practice (and reflective practice support) raises questions about the role and purpose of coach development and signals the need for coach (and developer) support that aligns with conceptions of coaching established almost – twenty years ago – as a complex social process (e.g. Jones, Armour, and Potrac Citation2003; Jones, Armour, and Potrac Citation2004). Put simply, coach development that aims to support reflective practice in coaching should be aware of social environmental factors that have been found to influence, construct and effect coaches’ thinking and practice (e.g. Cushion and Jones Citation2014; Downham and Cushion Citation2020). Findings from the current research have shown that such awareness requires an extension beyond evaluative thought centred on the individual and interactional factors (e.g. coach behaviours with athletes) and towards critical consideration of how power-knowledge relations, culture and systems surround and influence perspectives, beliefs, and practice. To problematise ideas about coaching, coaches (and developers) could for example, benefit from contextually relevant case history examples or stories from other coaches illustrating the experiences of those who have engaged with critical reflection to change practice. Currently, guidance about reflection is compelling rhetoric and too idealised, providing prescriptive lists, principles, and decontextualised examples (Cushion Citation2013), that do not engage with issues around critical reflection. In addition, social theory has been drawn upon to consider reflection and coaching critically in literature (e.g. Blackett, Evans, and Piggott Citation2019; Brookfield Citation2017; Denison, Jones, and Mills Citation2019; Denison, Mills, and Konoval Citation2015; Downham and Cushion Citation2020; inter alia) and may be a useful resource for coach development seeking to acknowledge and understand the impact of contextual factors. These examples may go some way towards supporting coach development, with what Brookfield (Citation2017) described as, ‘critical reflection’.

Conclusion

This study has presented a heuristic device to understand reflection in a high-performance coach education programme. The findings have articulated reflection’s salient features alongside explanations about the concept and practice. In addition, the research has extended and added an alternative conception of reflection in coaching, challenging the sometimes simplistic and unproblematic nature of existing research (e.g. Knowles et al. Citation2001; Knowles et al. Citation2006; Taylor et al. Citation2015; Trudel, Culver, and Werthner Citation2013) by acknowledging, incorporating and promoting the complexity of reflection in coaching. In doing so, this research has positioned knowledge in the context in which it is produced and thus recognised context as more than a variable to be controlled and managed. Subsequently, and via the analysis of empirical data, we have argued that the heuristic presented here offers representation of reflection in coaching. It is hoped that this coaching specific understanding goes some way towards supporting a more even experience of reflection and reflective practice in coach development. Specifically, as reflective practice continues to feature as a central tenet of effective coaching, coaches and coach developers should (and now can) consider the extent to which their reflective practice shifts thinking and stretches cognitive demands across a range of coaching specific reflection content. These implications extend towards encouraging coaches to use the heuristic to prompt a deconstruction of ‘who they think they are’ and the social conditions that govern their practice, development and existence. This implication responds to literature that has argued (e.g. Denison Citation2010; Cushion Citation2016; Lyle and Cushion Citation2017) and demonstrated (e.g. Konoval, Denison, and Mills Citation2018) that such reflection can expose and problematise taken-for-granted assumptions in coaching and encourage an exploration of alternative practices to produce novel ideas and improved athletic performance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Attard And, K., and K. Armour. 2006. “Reflecting on Reflection: A Case Study of One Teacher's Early-Career Professional Learning.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 11 (3): 209–229. doi:10.1080/17408980600986264.

- Blackett, A., A. Evans, and D. Piggott. 2019. ““They Have to toe the Line”: A Foucauldian Analysis of the Socialisation of Former Elite Athletes Into Academy Coaching Roles.” Sports Coaching Review 8 (1): 83–102.

- Brookfield, S. 1995. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Brookfield, S. 1998. “Critically Reflective Practice.” Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Profession 18: 197–205.

- Brookfield, S. 2009. “The Concept of Critical Reflection: Promises and Contradictions.” European Journal of Social Work 12 (3): 293–304. doi:10.1080/13691450902945215.

- Brookfield, S. 2017. Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bryman, A. 2016. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carson, F. 2008. “Utilizing Video to Facilitate Reflective Practice: Developing Sports Coaches.” International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching 3 (3): 381–390. doi:10.1260/174795408786238515.

- Cassidy, T., R. Jones, and P. Potrac. 2009. Understanding Sports Coaching: The Social, Cultural and Pedagogical Foundations of Coaching Practice. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Cropley, B., A. Miles, and J. Peel. 2012. Reflective Practice: Value of, Issues, and Developments within Sports Coaching. Sports Coach UK Original Research Project. Leeds: Sports Coach UK.

- Cropley, B., R. Neil, K. Wilson, and A. Faull. 2011. “Reflective Practice; Does it Really Work?” The Sport and Exercise Scientist 29: 16–17.

- Cushion, C. 2007. “Modelling the Complexity of the Coaching Process.” International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching 2 (4): 395–401. doi:10.1260/17479540778335965.

- Cushion, C. 2011. “Coach and Athlete Learning: A Social Approach.” In The Sociology of Sports Coaching, edited by R. Jones, P. Potrac, C. Cushion, and L. T. Ronglan. 166–178. London: Routledge.

- Cushion, C. 2013. “Applying Game Centered Approaches in Coaching: A Critical Analysis of the ‘Dilemmas of Practice’ Impacting Change.” Sports Coaching Review 2 (1): 61–76. doi:10.1080/21640629.2013.861312.

- Cushion, C. 2016. “Reflection and Reflective Practice Discourses in Coaching: A Critical Analysis.” Sport, Education and Society 23 (1): 82–94. doi:10.1080/13573322.2016.1142961.

- Cushion, C., K. Armour, and R. Jones. 2006. “Locating the Coaching Process in Practice: Models ‘For’ and ‘Of’ Coaching.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 11 (1): 83–99. doi:10.1080/17408980500466995.

- Cushion, C., P. Ford, and A. Williams. 2012. “Coach Behaviours and Practice Structures in Youth Soccer: Implications for Talent Development.” Journal of Sports Sciences 30 (15): 1631–1641. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.721930.

- Cushion, C., M. Griffiths, and K. Armour. 2018. “Professional Coach Educators n-situ: A Social Analysis of Practice.” Sport, Education and Society 24 (5): 533–546. doi:10.1080/13573322.2017.1411795.

- Cushion, C., and R. Jones. 2014. “A Bourdieusian Analysis of Cultural Reproduction: Socialisation and the ‘Hidden Curriculum’ in Professional Football.” Sport, Education and Society 19 (3): 276–298. doi:10.1080/13573322.2012.666966.

- Cushion, C., and M. Partington. 2016. “A Critical Analysis of the Conceptualisation of “Coaching Philosophy.” Sport, Education and Society 21 (6): 851–867. doi:10.1080/13573322.2014.958817.

- Denison, J. 2010. “Planning, Practice and Performance: The Discursive Construction of Coaches’ Knowledge.” Sport, Education and Society 15 (4): 461–478. doi:10.1080/13573322.2010.514740.

- Denison, J., L. Jones, and J. Mills. 2019. “Becoming a Good Enough Coach.” Sports Coaching Review 8 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1080/21640629.2018.1435361.

- Denison, J., J. Mills, and T. Konoval. 2015. “Sports’ Disciplinary Legacy and the Challenge of “Coaching Differently.” Sport, Education and Society 22 (6): 772–783. doi:10.1123/iscj.2018-0093.

- Downham, L. 2020. “Understanding Reflection and Reflective Practice in High-Performance Coach Education.” PhD Thesis. Loughborough University, UK.

- Downham, L., and C. Cushion. 2020. “Reflection in a High-Performance Sport Coach Education Program: A Foucauldian Analysis of Coach Developers.” International Sport Coaching Journal 7 (3): 1–13.

- Everett, J. 2002. “Organizational Research and the Praxeology of Pierre Bourdieu.” Organizational Research Methods 5 (1): 56–80.

- Fendler, L. 1999. “Making Trouble: Prediction, Agency and Critical Intellectuals.” In Critical Theories in Education: Changing Terrains of Knowledge and Politics, edited by T. Popkewitz and L. Fendler, 169–188. New York: Routledge.

- Fook, J. 2015. “Reflective Practice and Critical Reflection.” In Handbook for Practice Learning in Social Work and Social Care; Knowledge and Theory. 3rd ed., edited by J. Lishman, 440–454. London: Kingsley.

- Gallimore, R., W. Gilbert, and S. Nater. 2014. “Reflective Practice and Ongoing Learning: A Coach’s 10-Year Journey.” Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 15 (2): 268–288. doi:10.1080/14623943.2013.868790.

- Ghaye, T. 2010. Teaching and Learning Through Reflective Practice: A Practical Guide for Positive Action. Abingdon, OX: David Fulton Publishers.

- Gibbs, G. 1988. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Oxford: FE Unit Oxford Polytechnic.

- Giddens, A. 1976. New Rules of Sociological Method. London: Hutchinson.

- Gilbert, W., and J. Côté. 2013. “Defining Coaching Effectiveness: A Focus on Coaches’ Knowledge.” In Routledge Handbook of Sports Coaching, edited by P. Potrac, W. Gilbert, and J. Denison, 147–159. London: Routledge.

- Gilbert, W., and P. Trudel. 2001. “Learning to Coach Through Experience: Reflection in Model Youth Sport Coaches.” Journal of Teaching in Physical Education 21 (1): 16–34.

- Gilbert, W., and P. Trudel. 2006. “The Coach as a Reflective Practitioner.” In The Sports Coach as Educator: Reconceptualising Sports Coaching, edited by R. Jones, 113–127. London: Routledge.

- Gilbourne, D., P. Marshall, and Z. Knowles. 2014. “Reflective Practice in Sports Coaching: Thoughts on Process, Pedagogy and Research.” In An Introduction to Sports Coaching; Connecting Theory to Practice. (2nd ed.), edited by R. Jones and K. Kingston, . 3–.14. London: Routledge.

- Groom, R., C. Cushion, and L. Nelson. 2011. “The Delivery of Video-Based Performance Analysis by England Youth Soccer Coaches: Towards a Grounded Theory.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 23 (1): 16–32. doi:10.1080/10413200.2010.511422.

- Handcock, P., and T. Cassidy. 2014. “Reflective Practice for Rugby Union Strength and Conditioning Coaches.” Strength and Conditioning Journal 36 (1): 41–45.

- Holt, N., K. Neely, L. Slater, M. Camiré, J. Côté, J. Fraser-Thomas, D. MacDonald, L. Strachan, and K. Tamminen. 2017. “A Grounded Theory of Positive Youth Development Through Sport Based on Results from a Qualitative Meta-Study.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 10 (1): 1–49.

- Hughes, C., S. Lee, and G. Chesterfield. 2009. “Innovation in Sports Coaching: The Implementations of Reflective Cards.” Reflective Practice 10 (3): 367–384. doi:10.1080/14623940903034895.

- Irwin, G., S. Hanton, and D. Kerwin. 2004. “Reflective Practice and the Origins of Elite Coaching Knowledge.” Reflective Practice 5 (3): 425–442. doi:10.1080/1462394042000270718.

- Johns, C. 1995. “Framing Learning Through Reflection Within Carpers’ Fundamental Ways of Knowing.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 22: 226–234.

- Jones, R., K. Armour, and P. Potrac. 2003. “Constructing Expert Knowledge: A Case Study of a Top-Level Professional Soccer Coach.” Sport, Education and Society 8 (2): 213–229. doi:10.1080/13573320309254.

- Jones, R., K. Armour, and P. Potrac. 2004. Sports Coaching Cultures: From Practice to Theory. Oxon: Routledge.

- Jones, R., C. Edwards, and I. Filho. 2014. “Activity Theory, Complexity and Sports Coaching: An Epistemology for a Discipline.” Sport, Education and Society 21 (2): 200–216. doi:10.1080/13573322.2014.895713.

- Knowles, Z., A. Borrie, and H. Telfer. 2005. “Toward the Reflective Sports Coach: Issues of Context, Education and Application.” Ergonomics 48 (11–14): 1711–1720. doi:10.1080/00140130500101288.

- Knowles, Z., D. Gilbourne, A. Borrie, and A. Nevill. 2001. “Developing the Reflective Sports Coach: A Study Exploring the Processes of Reflective Practice within a Higher Education Coaching Programme.” Reflective Practice 2 (2): 185–207. doi:10.1080/14623940120071370.

- Knowles, Z., G. Tyler, D. Gilbourne, and M. Eubank. 2006. “Reflecting on Reflection: Exploring the Practice of Sports Coaching Graduates.” Reflective Practice 7 (2): 163–179. doi:10.1080/14623940600688423.

- Konoval, T., J. Denison, and J. Mills. 2018. “The Cyclical Relationship between Physiology and Discipline: One Endurance Running Coach’s Experiences Problematizing Disciplinary Practices.” Sports Coaching Review 8 (2): 124–148. doi:10.1080/21640629.2018.1487632.

- Kuklick, C., B. Gearity, and M. Thompson. 2015. “Reflective Practice in a University-Based Coach Education Program.” International Sport Coaching Journal 3 (2): 248–260. doi:10.1123/iscj.2014-0122.

- Lyle, J. 2002. Sports Coaching Concepts: A Framework for Coaches’ Behaviour. London: Routledge.

- Lyle, J. 2010. “Planning for Team Sports.” In Sports Coaching: Professionalisation and Practice, edited by J. Lyle and C. Cushion, 85–98. London: Elsevier.

- Lyle, J., and C. Cushion. 2017. Sport Coaching Concepts: A Framework for Coaching Practice. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Mezirow, J. 1981. “A Critical Theory of Adult Learning and Education.” Adult Education 32 (1): 3–24. doi:10.1177/074171368103200101.

- Mezirow, J. 1991. Transformative Dimensions of Adult Learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mezirow, J. 1998. “On Critical Reflection.” Adult Learning Quarterly 48 (3): 185–198. doi:10.1177/074171369804800305.

- Mezirow, J., and Associates. 2000. Learning as Transformation: Critical Perspectives on a Theory in Progress. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Mills, J., J. Denison, and B. Gearity. 2020. “Breaking Coaching’s Rules: Transforming the Body, Sport, and Performance.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 44 (3): 244–260. doi:10.1177/0193723520903228.

- Moon, J. 2004. A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning – Theory and Practice. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Partington, M., and C. Cushion. 2013. “An Investigation of the Practice Activities and Coaching Behaviours of Professional Top-Level Youth Soccer Coaches.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports 23 (3): 374–382. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01383.x.

- Schön, D. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Schwandt, T. 2001. Dictionary of Qualitative Inquiry. 2nd ed. London: SAGE.

- Scott, J. 2014. A Dictionary of Sociology. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, B., and N. Caddick. 2012. “Qualitative Methods in Sport: A Concise Overview for Guiding Social Scientific Sport Research.” Asia Pacific Journal of Sport and Social Science 1 (1): 60–73. doi:10.1080/21640599.2012.701373.

- Smith, B., and K. Mcgannon. 2018. “Developing Rigor in Qualitative Research: Problems and Opportunities within Sport and Exercise Psychology.” International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11 (1): 101–121. doi:10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357.

- Stodter, A., E. Cope, and R. Townsend. 2021. “Reflective Conversations as a Basis For Sport Coaches’ Learning: A Theory-Informed Pedagogic Design for Educating Reflective Practitioners.” Professional Development in Education. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1902836.

- Stodter, A., and C. Cushion. 2014. “Coaches’ Learning and Education: A Case Study of Culture in Conflict.” Sports Coaching Review 2 (1): 63–79. doi:10.1080/21640629.2014.958306.

- Stodter, A., and C. Cushion. 2017. “What Works in Coach Learning, How, and For Whom? A Grounded Process of Soccer Coaches’ Professional Learning.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 9 (3): 321–338. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2017.1283358.

- Stoszkowski, J., and D. Collins. 2014. “Blogs: A Tool to Facilitate Reflection and Community of Practice in Sports Coaching?” International Sport Coaching Journal 1 (3): 139–151. doi:10.1123/iscj.2013-0030.

- Taylor, B., and D. Garratt. 2010. “The Professionalization of Sports Coaching: Relations of Power, Resistance and Compliance.” Sport, Education and Society 15 (1): 121–139. doi:10.1080/13573320903461103.

- Taylor, S., P. Werthner, D. Culver, and B. Callary. 2015. “The Importance of Reflection for Coaches in Parasport.” Reflective Practice 16 (2): 269–284. doi:10.1080/14623943.2015.1023274.

- Thompson, N., and J. Pascal. 2012. “Developing Critically Reflective Practice.” Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 13 (2): 311–325. doi:10.1080/14623943.2012.657795.

- Trudel, P., D. Culver, and P. Werthner. 2013. “Looking at Coach Development from the Coach-Learner’s Perspective: Consideration for Coach Development Administrators.” In Routledge Handbook of Sports Coaching, edited by P. Potrac, W. Gilbert, and J. Denison, 375–387. London: Routledge.

- Van Manen, M. 1977. “Linking Ways of Knowing with Ways of Being Practical.” Curriculum Inquiry 6 (3): 205–228. doi:10.1080/03626784.1977.11075533.

- Webster, L., and P. Mertova. 2007. Using Narrative Inquiry as a Research Method: An Introduction to Using Critical Event Narrative Analysis in Research on Learning and Teaching. London: Routledge.