ABSTRACT

Background

There is a growing body of evidence showing the benefits to coaches and players in adopting a game-based pedagogical approach. Whilst the evidence in support of a game-based pedagogy continues to rise it is acknowledged that the complex art form of coaching is a uniquely personal one, where the coach may draw on previous first-hand experiences and traditional coaching practices regarding training methods rather than the use of current evidence-based best practice techniques.

Purpose

The aim of this randomised control trial was to evaluate the impact of a coach development intervention (MASTER) on game-based coaching practices of football coaches.

Methods

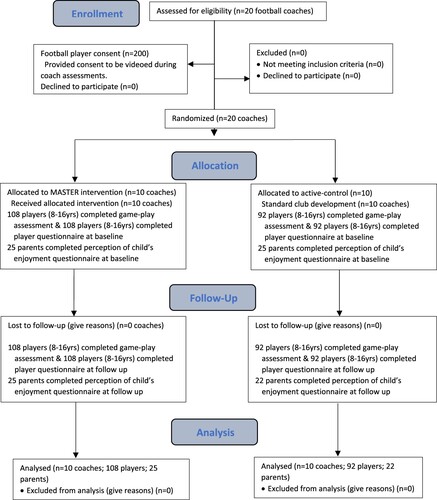

Four clubs were recruited, and 20 coaches were randomised to two groups, MASTER intervention (n = 10) and 10 usual practice (waitlist, n = 10); NSW Australia) which included 200 junior footballers (aged 8–16years). Intervention coaches participated in an 8-week multi-component intervention (which included a coach education workshop focused on positive game-based pedagogy, mentoring, peer evaluations and an online discussion forum) underpinned by positive coaching and game-based coaching practices. Pre- and post-intervention assessments occurred at baseline and 10 weeks. The primary aim was to investigate if the MASTER intervention could increase playing form (PF) and active learning time within training sessions. Three coaching sessions per coach were filmed at baseline and follow-up and assessed using the MASTER assessment tool. Secondary aims investigation included coach confidence and competence to coach (assessed by questionnaire), player game play and decision making (videoed during structured game play using a Game Performance Assessment Instrument), a range of player well-being measures including enjoyment, self-perception, and various motivations (questionnaire) and the parent’s perception of their child’s enjoyment was assessed by the completion of a questionnaire. Intervention effects were analysed using linear mixed models.

Findings

Significant effects were found for the primary outcome which was the percentage of training time devoted to playing-form activities (22.63%; 95% CI 9.07–36.19; P = 0.002, d = 1.78). No significant effect was observed for ALT. Significant interventions effects were also observed for the secondary outcomes of coach perceptions of confidence and confidence; player game skills including defence, support and decision making, wellbeing, physical self-perceptions, enjoyment, learning and performance orientations and motivation; and parent’s perception of child’s enjoyment (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

The MASTER programme was effective in improving game-based coaching practices of football coaches during training sessions, and in facilitating improvements in multiple coach and player outcomes.

Introduction

The holistic development of players and athletes, including levels of enjoyment, wellbeing, confidence and motivation are key outcomes for junior sports programmes (Vella, Oades, and Crowe Citation2011). The provision of positive sporting experiences can provide important physical, social and emotional benefits to junior players or athletes (Eime et al. Citation2013), with the coach recognised as one of the most critical factors impacting on the quality of the sporting experience for players. Given that approximately 70% of children and adolescents worldwide participate in some form of individual or team sport (Hulteen et al. Citation2017), the need for quality coaching practices is high. Potrac et al. (Citation2000) describe the role of the coach as ‘complex, requiring the technical knowledge of a sport, pedagogical skills of a teacher, counselling wisdom of a psychologist, training expertise of a physiologist and administrative leadership of a business executive’ (Potrac et al. Citation2000, p. 187).

Often in youth sport, especially at community or grassroots level, coaches are parent volunteers who may not understand the complex nature of coaching or the impact a coach may have. While most sporting codes, both nationally and internationally, have coach accreditation pathways, courses for community-level coaches are designed to help develop basic coaching knowledge and skills. These rarely assist coaches to design and implement training programmes to maximise learning and development and provide success for their players. Research indicates that the major sources of knowledge for community coaches are through trial and error and through interaction with other coaches and peers (Erickson et al. Citation2008). Furthermore, coaches often replicate the training practices they have been exposed to previously (Partington and Cushion Citation2013; Cushion, Armour, and Jones Citation2003), which may not support evidence-based best practice. The Australian Sports Commission suggested that coaching pathways for volunteer coaches need a mix of both formal (accreditation courses) and informal (mentoring and other face-to-face arrangements) components to develop essential coaching behaviours (Australian Sports Commission Citation2017).

In addressing the need for coach education and development, our research team has conducted two formative studies evaluating the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of a coach development programme (MASTER) in junior representative football, or soccer as it is sometimes known (Eather et al. Citation2019), and junior club-level netball (Eather et al. Citation2020). The MASTER programme (Outline in ) was specifically designed to help coaches understand and apply positive and game-based coaching pedagogies (Eather et al. Citation2019). Using the evidence-informed MASTER framework, coaches participating in the programme learned to use a strengths-based approach to developing sports competencies in junior players and provide high-quality learning opportunities within a supportive coaching setting (Eather et al. Citation2019). This study seeks to build upon these formative studies using a refined programme and a reduced dose of face-to-face delivery (informed by process evaluation results) to assess coaching behaviours and player outcomes more extensively.

Table 1. MASTER Programme, Framework and supporting evidence.

The aim of this randomised controlled trial is to establish whether a coach education programme (MASTER) can influence the proportion of training session time coaches spend implementing playing-form activities and actively engaging players in football learning activities (ALT). Further, secondary aims include improving the feedback provided to players during training sessions; improved player game-play skills and wellbeing; and improved coach, player and parent self-perceptions. We hypothesise that intervention coaches will increase the amount of playing form and active learning time in training sessions. Additionally, we further hypothesise that coaches will provide more constructive, learning-based feedback and reduce negative hustle and punishment-based comments. Similarly, because of the improved learning environment, coaches’ and players’ perceptions of their competence and confidence will improve and the parental view of players’ enjoyment will also increase. Finally, because of increasing playing-form opportunities, players will increase their understanding of the game, with particular attention to support play, defence and decision-making skills.

Coaching is distinguished by both coaching behaviours and coaching practices (Erickson et al. Citation2011). The former include provison of feedback, demeanour, expressiveness and interpersonal skills (McMullen et al. Citation2020). There is evidence to show they can affect a range of important player outcomes, especially for children. Verbal feedback is considered an important coaching behaviour, consisting of instructions and suggestions or information, all of which are essential in assisting players to achieve their individual and team goals (Franks, Hodges, and More Citation2001). The manner in which the coach communicates with players can also have a significant (positive or negative) influence on players’ skill development, performance (Otte et al. Citation2020), perceived confidence and enjoyment (Gjesdal et al. Citation2019). An environment that allows players to solve problems and be creative in a supportive team environment may be important for players to have positive sporting experiences (Harvey and Jarrett Citation2014). This can be achieved when coaches highlight and reward players’ strengths, effort and improvement, encourage contributions and use positive feedback or encouragement (Balaguer et al. Citation2012). Coaches who provide constructrive performance-based feedback in a postive manner may increase players’ satisfaction and perceived competence (Erikstad, Haugen, and Høigaard Citation2018). Unfortunately, studies exploring the prevalence of specific coaching behaviours within positive sporting environments is limited. There is extensive research exploring coaching practices at various levels of sport (i.e. playing form v training form); however, research investigating why coaches adopt certain practices and coaching effectiveness is relatively new (Vickery and Nichol Citation2020).

The learning, success and enjoyment a player achieves through sport is also influenced by the specific activities coaches employ during their training sessions (known as coaching practices). These important outcomes, along with player retention, are important benchmarks for assessing the quality of junior sport programmes (Australian Sports Commission Citation2017; Noble, Vermillion, and Foster Citation2016). Quality learning through sport is emphasised through game-based pedagogies, where players are engaged in various complex and pertinent playing-form learning activities, such as small-sided games and game-based scenarios, to help facilitate the creation of tactical knowledge, to develop problem-solving and to increase understanding in players (Lee et al. Citation2014; Williams and Hodges Citation2005). Studies have demonstrated that these coaching practices may increase player learning and success (Miller et al. Citation2017; Práxedes et al. Citation2018).

However, the implementation and evaluation of game-based approaches in organised sport is lacking. Currently, team-sport coaches commonly implement skill-drill practice activities (known as training-form activity) using direct instruction in a traditional delivery model (Partington, Cushion, and Harvey Citation2014; O’Connor, Larkin, and Williams Citation2018). Training-form activities tend to include repetitive practice of isolated and pre-determined skills, with the intent of learning technique and developing skill mastery and execution (Ford, Yates, and Williams Citation2010, Miller et al. Citation2017). Training-form activities are often used at the start of a training session in traditional approaches to coaching sports and include individual skills practice (e.g. passing, dribbling) or group training activities without opposition (e.g. passing drills, moving or dribbling around cones, shooting into an open goal). In a traditional delivery model, coaches may gradually introduce game-like activities or small-sided games towards the end of training (Ford, Yates, and Williams Citation2010; Williams and Hodges Citation2005). Primarily engaging players in training-form learning activities have been criticised due to the inadequate consideration of the contextual nature of games and sports (Lee et al. Citation2014; Williams and Hodges Citation2005). Training-form activities replicate the skill being practiced but often fail to give the player the conceptual understanding of when to apply the skill in the game. Research has also shown that training-form activities are less likely to enhance long-term retention compared to random and variable playing-form training (Fuhre and SÆTher Citation2020).

Using game-based coaching practices enables coaches to maximise the volume and quality of playing-form activity that players are exposed to, while simultaneously developing the wide range of competencies (physical, mental and cognitive) essential for playing a particular sport or sport in general (Pill Citation2012; Miller et al. Citation2015). Importantly, review-level evidence supports the positive impact that game-based pedagogies have on enjoyment – which is directly linked to player motivation, engagement and retention in youth sport (Harvey and Jarrett Citation2014, Light, Curry, and Mooney Citation2014). It is important to understand the authors are not suggesting the use of direct instruction should not take place. As a coaching practice, it can be a powerful tool for a coach when trying to explain or introduce a new concept or skill to players. The use of direct instruction can be the most appropriate coaching practice to support learning for players (Cope and Cushion Citation2020), however, the understanding of when to use this method is key. Cope and Cushion (Citation2020) suggest reconceptualisation of direct instruction in sport coaching is required. Despite the continued debate around which coaching method is most effective, direct instruction holds value as a learning tool in various coaching contexts. An example of this could be the use of direct instruction after a player has experienced a learning moment in a game-based environment but fails to execute the skill.

Several studies have found a positive relationship between parental expectations and children’s success and enjoyment. Literature has shown children’s expectations of success positively correlate with their perceptions of significant adults’ (including parents) satisfaction (Scanlan and Lewthwaite Citation1985, Citation1986). It has also been shown there is a positive relationship between mothers’ reported performance expectations and children’s reported enjoyment (Woolger and Power Citation1993).

Materials and methods

Research design

A two-arm randomised controlled trial to evaluate the MASTER Coach development intervention was conducted between March and August 2019 in NSW, Australia. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee and registered as a clinic trial (ACTRN12619000528156). This study was designed to measure the immediate effects of the provision of MASTER professional development to the coaches involved. We accept that coach behaviour across an extended period is likely to vary, and more longitudinal evaluation of coaching practices is required; however, the purpose of this investigation is to establish the efficacy of the MASTER programme to produce changed in coaching behaviour.

Recruitment and participants

A convenience sample of four football clubs (including the coaches of their junior teams and players) from New South Wales, Australia, was invited to participate in this study via an in-person meeting with the club president. The research team aimed to recruit five coaches from each club, with the first five eligible coaches included in the study. Signed informed consent from the club president, coaches, players and parents was required for participation in this study following a face-to-face information session at the football club. Twenty volunteer club-level coaches (17 males and three females) of varying coaching experience () who coach teams ranging from under-nines to 12-year-olds consented to be included in the study, while 200 players (173 males and 27 females) and 47 parents (10 males and 37 females) also consented to the study.

Table 2. MASTER intervention demographics.

Randomisation

Following baseline assessments, clubs were randomly assigned to either the treatment (MASTER) or to the usual practice (wait-list condition) by an independent third-party researcher using a random number-generating procedure. Both the control and intervention groups trained twice a week for the same length of time.

Intervention condition (Eight-week MASTER Coach Education programme)

The MASTER Coach Education programme was designed and developed by a research team from the University of Newcastle. The foundation of MASTER is ‘positive coaching’, which is promoted and fostered through game-based coaching practices and targets six core elements of sports coaching (Supplementary Table 1) (Eather et al. Citation2019). All details of the evidence supporting the pedagogical approach of MASTER has been published previously (Eather et al. Citation2020). In summary, MASTER was implemented using a coach learning process involving three consecutive phases lasting eight weeks, commencing in May 2019 (nine hours plus 16 normal training sessions), as outlined below.

Phase 1 (MASTER Coach development workshop)

Coaches participated in a four-hour theory and practical face-to-face coach education workshop held at various local venues and conducted by members of the research team (NE & BJ). The latest evidence regarding sport and youth coaching was presented, and the MASTER framework explained. A combination of lecture, discussion and group work activities provided coaches with the theoretical underpinnings and practical applications of the MASTER elements and provided coaches with opportunities to plan and assess sessions based on the MASTER framework and MASTER evaluation tool. Coaches were provided with all workshop materials (including examples of football training activities and planning tasks).

Phase 2 (Mentoring live and online / discussion)

This eight-week phase involved coaches implementing MASTER elements in their normal weekly training sessions. A member of the research team (mentor) attended at least two training sessions per coach, assisting with session planning, delivery and evaluation based on core elements of MASTER. An online discussion forum was created to investigate traditional training sessions and ways to implement the MASTER framework or change a training-form activity into a game-based activity and evaluate MASTER elements.

Phase 3 (Assessment and reflection sessions)

Mid-intervention, the mentor (BJ) prepared and implemented a one-hour training session for the coaches designed to highlight important aspects of the MASTER framework. Coaches were involved in evaluating the session using the MASTER observation checklist, and a group discussion was facilitated at the end of the session, which lasted approximately 30 minutes. This collaborative approach involved coaches in the feedback process to maximise learning and development (Eather et al. Citation2017; Eather et al. Citation2019). It also extends current practices in educational contexts, such as professional learning communities research (DuFour Citation2004), instructional rounds (Elmore Citation2007) and peer-dialogue in higher educational settings (Eather et al. Citation2019). Following the coach assessment and reflection session, coaches continued implementing MASTER strategies in their training sessions and were required to undertake a peer observation of a colleague (using the MASTER observation checklist). Feedback and professional dialogue between the coach and the peer observer followed these observation sessions, as this has been shown to be an effective and well-received learning strategy in the context of delivering sport and physical education sessions (Eather et al. Citation2017; Eather et al. Citation2019).

Wait-List control condition

The control groups were asked to continue with their normal coaching practices during the intervention period. They received the standard coach-development opportunities provided by their club and received the MASTER Workshop at the end of the study.

Measures

All assessments were conducted at baseline (May 2019) and after the eight-week implementation programme (August 2019) by the research team.

Primary outcomes

Following the published protocols of the two previous MASTER trials, a modified version of the Coach Analysis Intervention System (CAIS) (Cushion et al. Citation2012) was also used to measure coach behaviour. The CAIS is an event recording assessment (number of discrete coaching events are coded across a time period) has established validity and reliability, with previous use in youth coaching investigations (O’Connor, Larkin, and Williams Citation2017; Partington and Cushion Citation2013; Partington, Cushion, and Harvey Citation2014). The analysis of playing-form activity, along with all activity time within a training session, was evaluated over three training sessions (approximately three hours of scheduled training time at each time point) using a chest-mounted Go Pro Hero 3 and then coded using the MASTER Coach Observation Tool. The analysis of active learning time (ALT) or the number of active participants was also recorded. ALT was determined as the percentage of participants actively engaged within each activity as a function of the time allocated for the activity (e.g. 2/14 × 20 minutes = two players active out of 14 at any point of the 20-minute activity = 0.14 × 20 = 2.8 minutes ALT). The sum of ALT as a proportion of the total time spent in activities (minus the intervention stoppage time) was used as the measure of ALT for a training session (Eather et al. Citation2019). To assess reliability, the lead investigator and a trained research assistant co-coded 10% of the video footage and discussed any coding discrepancies until agreement was reached.

Secondary outcomes

Coach feedback

The amount and type of feedback (expressed as a percentage of total feedback) given by the coach during assessed training sessions was recorded and feedback was categorised into descriptive results, descriptive performance, prescriptive to improve, positive, negative, hustle and punishment.

Participant self-perceptions

Questionnaires were completed at baseline and follow-up by participants (coaches, players, and parents). The following outcomes were assessed:

Coaching confidence and coaching competence relating to football: purpose designed questionnaire used in MASTER (Eather et al. Citation2017).

Enjoyment of Sport

Wellbeing (Clarke et al. Citation2011)

Motivation (Lonsdale, Hodge, and Rose Citation2008; Viladrich et al. Citation2013)

Psychological health (Harter Citation1985)

Learning orientations (Papaioannou Citation1994)

Perception of children’s enjoyment of football (Motl et al. Citation2009)

Player game skills

Video analysis of decision-making and attacking and defensive abilities within game play was conducted using a previously validated game-performance assessment instrument (Miller et al. Citation2015). All students were recorded on an iPad playing a 10-minute 4 vs. 4 modified football game in a 20 m x 20 m grid (standard football rules applied). Individual players were coded as positive or negative for each game segment regarding on-ball decision-making and off-ball support and active defensive performance. Individual game skills were expressed as a percentage of positive outcomes achieved and an overall game play performance rating was calculated. One research assistant performed assessments of game performance videos. Assessor training included rating of game performance using video previously rated by two members of the research team (>95% agreement rate required). The complete assessment criteria can be accessed by emailing the corresponding author.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were conducted using PASW Statistics 24 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL) software and alpha levels were set at p < 0.05. Linear mixed models were fitted to compare intervention and control groups for continuous variables. Group, time and group-by-time interaction were assessed as fixed effects within the model, with the coach included as a random intercept to account for potential clustering at the level of the coach. Differences of means and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined using the linear mixed models. As the analyses of these secondary outcomes were intended to complement the primary outcome data and provide preliminary insights for future hypothesis testing, no multiplicity adjustments were conducted. The results are also presented with a focus on group-by-time effect sizes, represented by Cohen’s d (mean difference in change between groups divided by the pooled change score standard deviation), with effects interpreted as small (d = 0.2), medium (d = 0.5), and large (d = 0.8) (Cohen Citation1988).

Results

Twenty eligible coaches of junior football teams, 200 players and 47 parents consented to participate in the study (). All coaches, players and parents completed questionnaires at baseline and follow-up. Fidelity of the intervention was high given that the workshop, assessment and reflection session, peer-observations (two per coach), online discussion forum and all scheduled training sessions (16 per coach) were conducted as planned. There was no significant difference between groups for training session length at baseline and follow-up, and session length did not vary significantly across time (mean 73 minutes per session).

Primary outcomes

Coaching practices

There was a significant improvement in the intervention group, compared to the control group, for the proportion of training sessions dedicated to implementing playing-form activities (). This is reflected in the adjusted difference in change value, which represents the amount that the intervention group changed by in relation to the control group across the same period. A positive value indicates that the intervention group demonstrated greater amounts of change than the control. The intervention group increased the amount of playing-form activity by 22.63% above any increases seen among the control group across the measurement period. This saw the intervention group participating in 19.36% more playing-form activity at follow-up than the control group on average. There was no significant effect observed for the percentage of time spent engaged in active learning activities during training sessions [d = 0.91].

Table 3. MASTER Football Study intervention effects (by treatment group) – Coach, Player and Parent Outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

Coach feedback

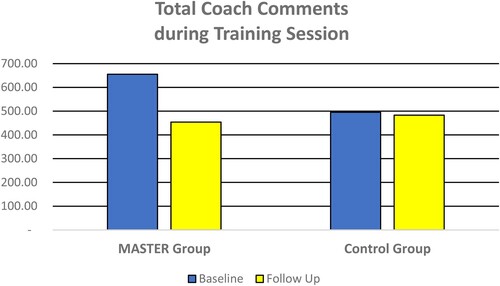

Significant changes were observed in the feedback behaviour of coaches (). Specifically, intervention coaches showed reduced use of hustle (mean change percentage compared to control group: −63.68% to −22.06%), negative comments (−60.33% compared to −14.60%) and punishment (−97.19% compared to 55.96%) and increased use of results feedback (420.61% compared to 150.39%), performance feedback (356.44% compared to 153.99%) and improvement feedback (154.57% compared to 10.76%). Additionally, total feedback comments made by intervention coaches were reduced by 30.73% as opposed to the control group, down by 2.46% ().

Table 4. MASTER intervention feedback comments per hour.

Participant self-perceptions

Coach perceptions: There was a significant improvement in the intervention group (compared to control) and large effect in confidence to coach football [d = 1.13] and competence to coach football in general [d = 1.07]. There was a moderate (but not significant) effect observed for the coaches’ perceived ability to achieve their player outcomes [d = 0.54].

Player perceptions: There was a positive effect between groups (in favour of the intervention group) for physical self-perceptions [d = 0.68], player enjoyment [d = 1.21]; learning and performance orientations [d = 0.90]; wellbeing [d = 1.51]; external motivation [d = 0.57] and autonomous motivation [d = 0.92].

Parent’s perception of enjoyment: There was a significant difference between groups (in favour of the intervention group) observed for parent’s perception of their child’s enjoyment of their sport [d = 0.55].

Player game play assessments

There was a significant improvement in the intervention group (compared to control) for total game play skills [d = 0.83]. Furthermore, each of the sub-components displayed equivalent positive outcomes including defence [d = 0.43], support skills [d = 0.58] and decision-making [d = 0.63].

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of the MASTER Coach Development intervention for improving the amount of playing form and active learning time within a football training session. Further to the primary aims, a range of secondary aims was hypothesised, including the modification of coaches’ feedback to a more positive constructive environment, improved coach and player wellbeing and improved overall game play and decision making by players, due to the exposure of coaches to the MASTER programme.

Coaches participating in the MASTER intervention displayed changes in coaching practice that exposed players to greater playing form and higher quality feedback. In turn, athletes displayed greater growth in their decision-making abilities in the game. Intervention coaches and players significantly increased their confidence, self-perception of competence and their enjoyment of the game.

Coaching practices

The time allocated to implementing playing-form activities increased by 22% more in the intervention group than in the control group. This increase in playing-form activity is consistent with previous MASTER evaluation undertaken in netball (Eather et al. Citation2020), whereby an increase of 25% in playing-form activity (and large effect) was demonstrated by coaches receiving the MASTER programme. The previous studies focused on increasing playing-form activities in sport and school settings to develop players’ decision-making skills (Gray and Sproule Citation2011; Harvey et al. Citation2010) – although neither study formally assessed nor reported changes in playing-form activities. Increasing exposure to playing-form activities within training sessions has been shown to increase the contextual understanding of players as well as assisting players in preparing themselves for the physiological demands of competition (Miller et al. Citation2017). In the current study, however, the overall percentage of time coaches allocated to playing form was considerably higher, with intervention football coaches allocating 72% of their session time to playing form, compared to 35% in the previous MASTER netball study. This difference may be attributed to the football training methods promoted and enforced through the standardised curriculum provided to all football coaches in Australia (netball coaches are not provided with a regulated curriculum). A large positive effect on the amount of time coaches engaged players in learning activities at training time (active learning time) also resulted. Increasing the time players are exposed to learning opportunities and skill practice in context is important for maximising player development within the training session time available to coaches. The significant increase in playing-form activity and active learning time demonstrated in this study is encouraging and demonstrates that coaches have the capacity to improve their practices with targeted assistance.

Coach feedback

Relative to control coaches, intervention coaches had significant changes to the type of feedback they provided their players. Intervention coaches significantly reduced their hustle (−64%) and negative (−32%) comments coaches as opposed to the control group (−22% hustle and −15% negative). Significant increases were observed in performance-related feedback (results 421%, performance 356% and improvement 155%) given by intervention coaches as opposed to the control group (results 150%, performance 154% and improvement 11%). This helps create a more positive learning environment for players. It should be noted whilst positive comments decreased (−32% in intervention group), they still contributed to approximately 50% of all coaches’ comments. Possibly, the reduction in positive comments is indicative of a shift towards an increase in specific performance-related feedback. For example, a comment such as ‘good work’, may evolve into ‘good work, you took the touch towards your next action’ following the MASTER intervention. Previous studies have demonstrated that positive performance-related feedback is essential for sustaining motivation in players (Eather et al. Citation2019; Noble, Vermillion, and Foster Citation2016). Additionally, a previous study in football found that coaches who used hustle significantly led to a decrease in game performance amongst players (Brandes and Elvers Citation2017). Whist the intervention group achieved significant improvements in feedback, the improvements of the control group in several categories of feedback is worthy of discussion. Given that the study commenced at the start of the football season and lasted 8 weeks, improvements could be potentially explained by improved relationships between coaches and players as the football season progressed. For example, over time the coach gains an understanding of their players’ needs and wants, and vice versa, and consequently the coach innately adjusts feedback to suit the developing players. Whilst the data shows the quality of feedback greatly improves over the course of a season organically, by gaining a deep understanding of the types of feedback in the MASTER workshop, the intervention group significantly improved feedback quality over the organic growth observed in the control group.

Despite previous research calling for coach professional development on feedback practices (Tristán et al. Citation2020), to the authors’ knowledge, this is the first intervention that provides coaches with specific feedback training.

Coach perceptions

Intervention coaches exhibited significant improvements in coach perceptions regarding their confidence and competence to coach football, and a non-significant improvement in perception to achieve player outcomes compared to the control group. These improvements amongst the coaches could be attributed to the unique practical coach development programme. In addition to the workshop, coaches were provided with mentoring, online support, practical demonstrations, peer observation assessments and an easy-to-use training session planner. Similar findings to this study were observed in the MASTER netball trial (Eather et al. Citation2020). It has been reported previously that programmes that provide coaches with practical learning, peer discussions and reflective practices have merit for coach education (Sousa, Smith, and Cruz Citation2008). Currently, in Australia, coach education programmes and accreditation courses provide written, video and online examples of training activities and model training sessions; however, limited research has trialled an experiential in-situ approach. Previous research has highlighted that coaches embrace and value problem-based coach development programmes that provide them with the practical application of new learning opportunities, as well as group discussion and reflection sessions (Clarke et al. Citation2011)

Player outcomes

Game-related skills (in relation to defence, support and decision-making skills in football) significantly improved among intervention players. The results may be related to the focus on game-based coaching in the MASTER programme and subsequent increased game-based experiences over the intervention period. Previous studies, including the MASTER netball trial, achieved equivalent results (Eather et al. Citation2020; Miller et al. Citation2017). Improved confidence, enjoyment, social aspects and motivation of players have consistently been evidenced through game-centred approaches to sports coaching, such as teaching games for understanding (TGfU) versus a traditional skill-based repetition model across various sports (Allison and Thorpe Citation1997; Haneishi Citation2014). The significant improvement in game skills in this study is particularly encouraging, as it shows the benefits of delivering coaching practices in football under this method. Increasing the ability of players to identify moments within the game to action support and defence and to make informed decisions may facilitate a greater sense of accomplishment and a greater perception of competence and confidence in their chosen sport – which may have important repercussions for retention in the sport (Bailey, Cope, and Pearce Citation2013).

In this current study, significant improvements were observed for players’ physical self-perceptions, enjoyment, learning and performance orientations, wellbeing and several motivation factors. The current literature notes that players’ self-perceptions are intricately linked to the improvement in muscle development and physical abilities (Christiansen et al. Citation2018) and that children’s perception of their physical abilities relates to participation and engagement in sport (Crane and Temple Citation2015). A previous MASTER trial with netball players had similar significant improvements in self-perceptions in the physical domain, which suggests the MASTER coaching workshop and framework provides coaches with the skills to provide learning opportunities at training that clearly support player development. The improvements in player enjoyment and wellbeing displayed in this study are incredibly positive and may have important implications for player retention. They also contradict the null findings in these outcomes evident in the netball study. This could be attributed to the evolution of the MASTER coaching workshop based on feedback from previous workshops, where a larger emphasis was placed on showing coaches, through peer discussion and feedback, how to incorporate a fun element into their training games. Fun is included in the MASTER framework (supplementary table) in the engagement section. Coaches are encouraged to use features such as their behaviour (energy and humour) and varied activities using a hook to engage players. This approach in the workshops attempted to challenge a previously identified perception from coaches that skill development and fun are in apparent conflict (Bengoechea, Strean, and Williams Citation2004). Aligning the two and exploring the notion that a training game can indeed be fun while also developing skills was a key improvement in the workshop and may be a reason for the improved results. This alignment was further evidenced by a significant increase in parents’ perception of their child’s enjoyment of training.

Strengths and limitations

This study builds the evidence for the effectiveness of the MASTER Coach Development programme for improving the quality of sports coaching (now implemented with football and netball coaches) in junior sport. Furthermore, the study investigated the impact of coaching behaviours on a range of player outcomes (enjoyment, motivation, wellbeing and game skills), which is an important and under-researched area (O’Connor, Larkin, and Williams Citation2017; Vella, Oades, and Crowe Citation2011). MASTER also provides a simple and easy-to-follow framework to help coaches create positive and enjoyable training programmes for young players and promotes game-based coaching pedagogy and high-quality learning environments (Ladwig and King Citation2003). Based on coaches’ feedback from previous studies, we reduced the duration of the workshop and increased the practical workshop examples within. This allowed coaches the opportunity to further engage with the elements, as it enabled them to relate to their own coaching environments.

Limitations of this study includes the sample size and the fact it was undertaken in one region. We recommend the implementation of a large-scale, multi-region trial to build evidence for the effectiveness of MASTER. While the intervention was effective, it involved considerable time and support from researchers, and further study of a scalable programme is likely required. The research team also acknowledges that positive changes in coaching practices and behaviours may have been influenced by the fact that the research team where responsible for conducting the MASTER programme and assessments. However, as an efficacy trial, this preliminary evidence is important for informing further large-scale MASTER studies. Due to budget and resource constraints, the research team could not undertake interviews with coaches to understand why they did what they did and why they believe the changes occurred. We would suggest this might be an interesting insight and recommend its incorporation into further research. Finally, the study is not adequately powered to detect change in a specific outcome but was designed to investigate whether a coach education programme could influence training activities and behaviours.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that a targeted and theory-driven coach education programme (MASTER) can facilitate significant improvements in coaching practices, coach self-perceptions among junior club-level football coaches and facilitate improvements in a range of important player outcomes. Using the MASTER framework allowed coaches to provide players with more game-based learning moments through increased use of playing-form activities, improved player game-awareness through analysis of their game-based decision-making, including defence and support play, resulting in players becoming more confident about their football and increasing their enjoyment of the sport. Coaches also gained competence and confidence in their ability, ultimately creating a more positive training environment for all.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the football players and coaches who volunteered to participate in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allison, S., and R. Thorpe. 1997. “A Comparison of the Effectiveness of two Approaches to Teaching Games Within Physical Education. A Skills Approach Versus a Games for Understanding Approach.” British Journal of Physical Education 28 (3): 9–13.

- Australian Sports Commission. 2017. Teaching Sport to Children: Discussion Paper. Canberra: Australian Sports Commission.

- Bailey, R., E. J. Cope, and G. Pearce. 2013. “Why do Children Take Part in, and Remain Involved in Sport? A Literature Review and Discussion of Implications for Sports Coaches.” International Journal of Coaching Science 7 (1): 56–75.

- Balaguer, I., L. González, P. Fabra, I. Castillo, J. Mercé, and J. L. Duda. 2012. “Coaches’ Interpersonal Style, Basic Psychological Needs and the Well- and ill-Being of Young Soccer Players: A Longitudinal Analysis.” Journal of Sports Sciences 30 (15): 1619–1629. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.731517.

- Bengoechea, E. G., W. B. Strean, and D. J. Williams. 2004. “Understanding and Promoting fun in Youth Sport: Coaches’ Perspectives.” Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy 9 (2): 197–214.

- Brandes, M., and S. Elvers. 2017. “Elite Youth Soccer Players’ Physiological Responses, Time-Motion Characteristics, and Game Performance in 4 vs. 4 Small-Sided Games: The Influence of Coach Feedback.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 31 (10): 2652–2658. doi:10.1519/JSC.0000000000001717.

- Christiansen, L. B., P. Lund-Cramer, R. Brondeel, S. Smedegaard, A. D. Holt, and T. Skovgaard. 2018. “Improving Children's Physical Self-Perception Through a School-Based Physical Activity Intervention: The Move for Well-Being in School Study.” Mental Health and Physical Activity 14: 31–38.

- Clarke, A., T. Friede, R. Putz, J. Ashdown, S. Martin, A. Blake, Y. Adi, et al. 2011. “Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): Validated for Teenage School Students in England and Scotland. A Mixed Methods Assessment.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 487. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-487.

- Cohen, J. 1988. “Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences–Second Edition. 12 Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.” Hillsdale, New Jersey 13: 567.

- Cope, Ed, and Chris Cushion. 2020. “A Move Towards Reconceptualising Direct Instruction in Sport Coaching Pedagogy.” Profession 18: 19.

- Crane, J., and V. Temple. 2015. “A Systematic Review of Dropout from Organized Sport among Children and Youth.” European Physical Education Review 21 (1): 114–131.

- Cushion, C. J., K. M. Armour, and R. L. Jones. 2003. “Coach Education and Continuing Professional Development: Experience and Learning to Coach.” Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich ) 55 (3): 215–230. doi:10.1080/00336297.2003.10491800.

- Cushion, C. J., S. Harvey, B. Muir, and L. Nelson. 2012. “Developing the Coach Analysis and Intervention System (CAIS): Establishing validity and reliability of a computerised systematic observation instrument.” Journal of Sports Sciences 30 (2): 201–216.

- DuFour, R. 2004. “What is a “Professional Learning Community?”.” Educational Leadership 61 (8): 6–11.

- Eather, N., B. Jones, A. Miller, and P. J. Morgan. 2019. “Evaluating the Impact of a Coach Development Intervention for Improving Coaching Practices in Junior Football (Soccer): The “MASTER” Pilot Study.” Journal of Sports Sciences, 1–13. doi:10.1080/02640414.2019.1621002.

- Eather, N., A. Miller, B. Jones, and P. J. Morgan. 2020. “Evaluating the Impact of a Coach Development Intervention for Improving Coaching Practices and Player Outcomes in Netball: The MASTER Coaching Randomized Control Trial.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching:1747954120976966, doi:10.1177/1747954120976966.

- Eather, N., N. Riley, D. Miller, and S. Imig. 2019. “Evaluating the Impact of two Dialogical Feedback Methods for Improving pre-Service Teacher's Perceived Confidence and Competence to Teach Physical Education Within Authentic Learning Environments.” Journal of Education and Training Studies 7 (8): 15. doi:10.11114/jets.v7i8.4053.

- Eather, N., N. Riley, D. Miller, and B. Jones. 2017. “Evaluating the Effectiveness of Using Peer-Dialogue Assessment (PDA) for Improving Pre-Service Teachers' Perceived Confidence and Competence to Teach Physical Education.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 42 (1): 69–83. doi:10.14221/ajte.2017v42n1.5.

- Eime, R. M., J. A. Young, J. T. Harvey, M. J. Charity, and W. R. Payne. 2013. “A Systematic Review of the Psychological and Social Benefits of Participation in Sport for Adults: Informing Development of a Conceptual Model of Health Through Sport.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 10 (1): 135. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-10-135.

- Elmore, R. F. 2007. “Professional Networks and School Improvement.” School Administrator 64 (4): 20–25.

- Erickson, K. I., M. W. Bruner, D. J. MacDonald, and J. Côté. 2008. “Gaining Insight Into Actual and Preferred Sources of Coaching Knowledge.” International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching 3 (4): 527–538.

- Erickson, K., J. Côté, T. Hollenstein, and J. Deakin. 2011. “Examining Coach–Athlete Interactions Using State Space Grids: An Observational Analysis in Competitive Youth Sport.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 12 (6): 645–654. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2011.06.006.

- Erikstad, M. K., T. Haugen, and R. Høigaard. 2018. “Positive Environments in Youth Football.” German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research 48 (2): 263–270. doi:10.1007/s12662-018-0516-1.

- Ford, P. R., I. Yates, and A. M. Williams. 2010. “An Analysis of Practice Activities and Instructional Behaviours Used by Youth Soccer Coaches During Practice: Exploring the Link Between Science and Application.” Journal of Sports Sciences 28 (5): 483–495. doi:10.1080/02640410903582750.

- Franks, M. I., N. Hodges, and K. More. 2001. “Analysis of Coaching Behaviour.” International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport 1 (1): 27–36. doi:10.1080/24748668.2001.11868246.

- Fuhre, J. A. N., and S. A. SÆTher. 2020. “Skill Acquisition in a Professional and non-Professional U16 Football Team: The use of Playing Form Versus Training Form.” Journal of Physical Education & Sport 20: 2030–2035.

- Gjesdal, S., A. Stenling, B. Solstad, and Y. Ommundsen. 2019. “A Study of Coach-Team Perceptual Distance Concerning the Coach-Created Motivational Climate in Youth Sport.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 29 (1): 132–143. doi:10.1111/sms.13306.

- Gray, S., and J. Sproule. 2011. “Developing Pupils’ Performance in Team Invasion Games.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 16 (1): 15–32. doi:10.1080/17408980903535792.

- Haneishi, K. 2014. “Impacts of the Game-Centered Approach on Cognitive Learning of Game Play and Game Performance during 5-week of Spring Season with Intercollegiate Female Soccer Players.”

- Harter, S. 1985. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Children: Revision of the Perceived Competence Scale for Children. Denver, CO: University of Denver Press.

- Harvey, S., C. J. Cushion, H. M. Wegis, and A. N. Massa-Gonzalez. 2010. “Teaching Games for Understanding in American High-School Soccer: A Quantitative Data Analysis Using the Game Performance Assessment Instrument.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 15 (1): 29–54. doi:10.1080/17408980902729354.

- Harvey, S., and K. Jarrett. 2014. “Review of the Game-Centred Approaches to Teaching and Coaching Literature Since 2006.” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 19 (3): 278–300. doi:10.1080/17408989.2012.754005.

- Hulteen, R. M., J. J. Smith, P. J. Morgan, L. M. Barnett, P. C. Hallal, K. Colyvas, and D. R. Lubans. 2017. “Global Participation in Sport and Leisure-Time Physical Activities: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Preventive Medicine 95: 14–25. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.11.027.

- Ladwig, J., and M. B. King. 2003. Quality Teaching in NSW Public Schools. Edited by Department of Education. Sydney: Department of Education and Training.

- Lee, M. C. Y., J. Yi Chow, J. Komar, C. W. K. Tan, and C. Button. 2014. “Nonlinear Pedagogy: An Effective Approach to Cater for Individual Differences in Learning a Sports Skill.” PLOS ONE 9 (8): e104744. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104744.

- Light, R., C. Curry, and A. Mooney. 2014. “Game Sense as a Model for Delivering Quality Teaching in Physical Education.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education 5 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1080/18377122.2014.868291.

- Lonsdale, C., K. Hodge, and E. A. Rose. 2008. “The Behavioral Regulation in Sport Questionnaire (BRSQ): Instrument Development and Initial Validity Evidence.” Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology 30 (3): 323–355.

- McMullen, B., H. L. Henderson, D. H. Ziegenfuss, and M. Newton. 2020. “Coaching Behaviors as Sources of Relation-Inferred Self-Efficacy (RISE) in American Male High School Athletes.” International Sport Coaching Journal 7 (1): 52–60.

- Miller, A., E. Christensen, N. Eather, S. Gray, J. Sproule, J. Keay, and D. R. Lubans. 2015. “Can Physical Education and Physical Activity Outcomes be Developed Simultaneously Using a Game-Centered Approach?” European Physical Education Review 22 (1): 113–133. doi:10.1177/1356336(15594548.

- Miller, A., E. M. Christensen, N. Eather, J. Sproule, L. Annis-Brown, and D. R. Lubans. 2015. “The PLUNGE Randomized Controlled Trial: Evaluation of a Games-Based Physical Activity Professional Learning Program in Primary School Physical Education.” Preventive Medicine 74 (0): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.02.002.

- Miller, A., S. Harvey, D. Morley, R. Nemes, M. Janes, and N. Eather. 2017. “Exposing Athletes to Playing Form Activity: Outcomes of a Randomised Control Trial among Community Netball Teams Using a Game-Centred approach.” Journal of Sports Sciences 35 (18): 1846–1857. doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1240371.

- Motl, R. W., R. K. Dishman, R. Saunders, M. Dowda, G. Felton, and R. R. Pate. 2009. “Measuring Enjoyment of Physical Activity in Children: Validation of the Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 21 (S1): S116–S129. doi:10.1080/10413200802593612.

- Noble, J., M. Vermillion, and K. Foster. 2016. “Coaching Environments and Student-Athletes: Perceptions of Support, Climate and Autonomy.” The Sport Journal 19: 1–9.

- O’Connor, D., P. Larkin, and A. M. Williams. 2017. “What Learning Environments Help Improve Decision-Making?” Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy 22 (6): 647–660. doi:10.1080/17408989.2017.1294678.

- O’Connor, D., P. Larkin, and A. M. Williams. 2018. “Observations of Youth Football Training: How do Coaches Structure Training Sessions for Player Development?” Journal of Sports Sciences 36 (1): 39–47. doi:10.1080/02640414.2016.1277034.

- Otte, F. W., K. Davids, S.-K. Millar, and S. Klatt. 2020. “When and How to Provide Feedback and Instructions to Athletes?—How Sport Psychology and Pedagogy Insights Can Improve Coaching Interventions to Enhance Self-Regulation in Training.” Frontiers in Psychology 11 (1444), doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01444.

- Papaioannou, A. 1994. “Development of a Questionnaire to Measure Achievement Orientations in Physical Education.” Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 65 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1080/02701367.1994.10762203.

- Partington, M., and C. Cushion. 2013. “An Investigation of the Practice Activities and Coaching Behaviors of Professional top-Level Youth Soccer coaches.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 23 (3): 374–382. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0838.2011.01383.x.

- Partington, M., C. Cushion, and S. Harvey. 2014. “An Investigation of the Effect of Athletes’ age on the Coaching Behaviours of Professional top-Level Youth Soccer Coaches.” Journal of Sports Sciences 32 (5): 403–414. doi:10.1080/02640414.2013.835063.

- Pill, S. 2012. “Teaching Game Sense in Soccer.” Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance 83 (3): 42–46.

- Potrac, P., C. Brewer, R. Jones, K. Armour, and J. Hoff. 2000. “Toward an Holistic Understanding of the Coaching Process.” Quest (Grand Rapids, Mich ) 52 (2): 186–199. doi:10.1080/00336297.2000.10491709.

- Práxedes, A., A. Moreno, A. Gil-Arias, F. Claver, and F. Del Villar. 2018. “The Effect of Small-Sided Games with Different Levels of Opposition on the Tactical Behaviour of Young Footballers with Different Levels of Sport Expertise.” PLOS ONE 13 (1): e0190157. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0190157.

- Scanlan, Tara K., and Rebecca Lewthwaite. 1985. “Social Psychological Aspects of Competition for Male Youth Sport Participants: Iii. Determinants of Personal Performance Expectancies.” Journal of Sport Psychology 7 (4): 389–399. doi:10.1123/jsp.7.4.389.

- Scanlan, Tara K., and Rebecca Lewthwaite. 1986. “Social Psychological Aspects of Competition for Male Youth Sport Participants: Iv. Predictors of Enjoyment.” Journal of Sport Psychology 8 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1123/jsp.8.1.25.

- Sousa, C., R. Smith, and J. Cruz. 2008. “An Individualized Behavioral Goal-Setting Program for Coaches.” Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology 2: 258–277. doi:10.1123/jcsp.2.3.258.

- Tristán, J., R. M. Ríos-Escobedo, J. M. López-Walle, J. Zamarripa, M. A. Narváez, and O. Alvarez. 2020. “Coaches’ Corrective Feedback, Psychological Needs, and Subjective Vitality in Mexican Soccer Players.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 631586–631586. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.631586.

- Vella, S., L. Oades, and T. Crowe. 2011. “The Role of the Coach in Facilitating Positive Youth Development: Moving from Theory to Practice.” Journal of Applied Sport Psychology 23 (1): 33–48. doi:10.1080/10413200.2010.511423.

- Vickery, Will, and Adam Nichol. 2020. “What Actually Happens During a Practice Session? A Coach’s Perspective on Developing and Delivering Practice.” Journal of Sports Sciences 38 (24): 2765–2773. doi:10.1080/02640414.2020.1799735.

- Viladrich, C., P. R. Appleton, E. Quested, J. L. Duda, S. Alcaraz, J. Heuzé, P. Fabra, et al. 2013. “Measurement Invariance of the Behavioural Regulation in Sport Questionnaire When Completed by Young Athletes Across Five European Countries.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 11 (4): 384–394. doi:10.1080/1612197X.2013.830434.

- Williams, A. M., and N. J. Hodges. 2005. “Practice, Instruction and Skill Acquisition in Soccer: Challenging Tradition.” Journal of Sports Sciences 23 (6): 637–650. doi:10.1080/02640410400021328.

- Woolger, Christi, and Thomas G. Power. 1993. “Parent and Sport Socialization: Views from the Achievement Literature.” Journal of Sport Behavior 16 (3): 171.